Abstract

Objective

To perform a molecular screening to detect infections by the mayaro virus and possible coinfections with Chikungunya during an outbreak in the state of Tocantins/Brazil in 2017.

Results

Of a total 102 samples analyzed in this study, 6 cases were identified with simultaneous infection between mayaro and chikungunya viruses (5.88%). In these 6 samples, the mean Cycle threshold (Ct) for CHIKV was 26.87 (SD ± 10.54) and for MAYV was 29.58 (SD ± 6.34). The mayaro sequences generated showed 95–100% identity to other Brazilian sequences of this virus and with other MAYV isolates obtained from human and arthropods in different regions of the world. The remaining samples were detected with CHIKV monoinfection (41 cases), DENV monoinfection (50 cases) and coinfection between CHIKV/DENV (5 cases). We did not detect MAYV monoinfections.

Keywords: Arbovirus, Molecular screening, Coinfection, Mayaro, Chikungunya, Brazil

Introduction

The arbovirus (arthropod–borne viruses) emergence and re-emergence has become increasingly frequent in countries of the tropical and subtropical regions of the world [1, 2]. Cases of coinfections involving different arboviruses during outbreaks are becoming common in areas where these viruses are co-circulating [3–5]. The arboviruses are the main causative agents of infectious diseases of public health importance [6]. The environmental conditions, vector density and migration and immigration processes contribute to the spread and maintenance of these viruses in nature [7].

The chikungunya (CHIKV) and mayaro (MAYV) viruses are endemic arboviruses in Brazil, belongs to the family Togaviridae (genus Alphavirus). These viruses cause an acute febrile illness nonspecific that can lead to severe and debilitating clinical conditions [8]. Currently, three genotypes different for each of these arbovirus have been reported, being them: West Africa, East-Central South Africa (ECSA) and Asian to CHIKV [9] and the genotypes D (widely dispersed), L (limited) and N (new) to MAYV [10].

The CHIKV was identified for the first time in Brazil in 2014 [11]. The Asian and ECSA genotypes entered in country through the northern (Amapá state) and northeast (Bahia state) regions, respectively [12]. MAYV was reported initially in the Amazon region and later its circulation was notified in other areas of Brazil, including the states of Goiás, Mato Grosso, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro [13–16]. Currently, both viruses circulate in country causing outbreaks or sporadic cases of infections in humans [17, 18].

Some studies have shown cases of coinfection between MAYV and other arboviruses. One recent paper by Aguilar-Luis [19] sought to show the emergence of the MAYV and cases of coinfection with Dengue virus (DENV) in Peru. The authors demonstrated that of a total of 496 samples analyzed, the prevalence of people coinfected with DENV/MAYV was 6.4%. In a systematic review showing the frequency and clinical presentation of coinfections involving the Zika virus, a study reported a single case of coinfection between this virus and MAYV [20]. However, there are scarce studies reporting coinfection between MAYV and CHIKV.

In Brazil, the co-circulation of these arboviruses has been demonstrated, but coinfections between MAYV/CHIKV are still little documented. This reinforces the need for differential diagnosis for MAYV during CHIKV outbreaks. Thus, our study had the objective of to perform a molecular screening to detect infections by the mayaro virus and possible coinfections with chikungunya during an outbreak occurred in the state of Tocantins/Brazil in 2017.

Main text

Methods

Study design

In this cross-sectional observational study, we analyzed 102 serum samples obtained from patients who consulted different health units in the state of Tocantins with symptoms of arboviral infection. Initially, we performed a screening for the detection of zika, dengue and chikungunya viruses [21]. Here, we report a screening performed for the detection of MAYV. Clinical and demographic information of the patients were described by the health units and sent to the LACEN de Palmas/Tocantins. Afterwards, these data were sent to the Retrovirology Laboratory. The samples analyzed were collected between the months of January to August of 2017.

Study area

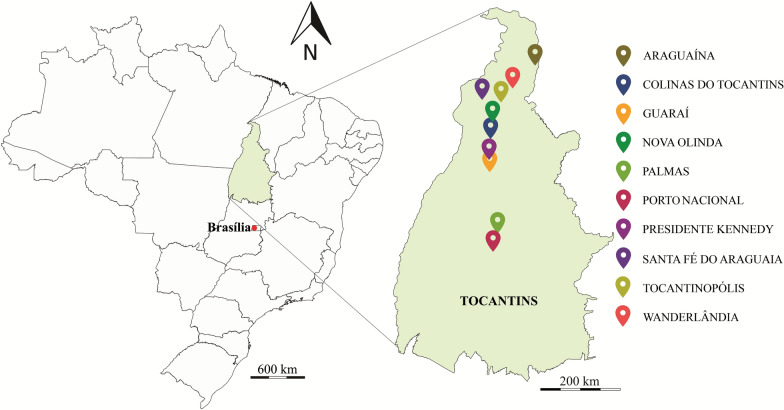

Tocantins is a Brazilian state located in the northern region of the country. With an area of 277,720.520 km2, it borders the states of Goiás (South), Piaui (East), Maranhão (Northeast), Bahia (Southeast), Pará (Northwest) and Mato Grosso (Southwest) (Fig. 1) [22].

Fig. 1.

Location of the study area (state of Tocantins/TO) and of the municipalities where the samples were collected (collection points). This map was built using the program QGIS, v. 2.18

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Sao Paulo [21] (CAAE: 18908719.2.0000.5505). All patients enrolled signed an informed written consent. The patients’ personal information was anonymized before the data was accessed. This study accessed the information of the patients on demographic characteristics, clinical signs, and symptoms.

Inclusion criteria

The study participants were individuals with more than 18 years of age, included both sexes and presented compatible symptoms of arboviral infections (fever, arthralgia, exanthema, headache, myalgia, nausea, retro-orbital pain, generalized body pain, among other clinical aspects and were tested within 8 days of the onset of symptoms, following criteria established by the World Health Organization [23] and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [24].

Detection molecular of dengue, chikungunya and mayaro

All 102 samples were analyzed by molecular diagnosis. First, the RNA viral was obtained from 200 μL of serum.

samples using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Previously, we had performed RT-qPCR assay for detection of dengue and chikungunya using the GoTaq®Probe1-Step RT-qPCR System following recommendations of the manufacturer. The primers and probes were previously described in Alm et al. [25] and Cecilia et al. [26] for dengue and chikungunya, respectively. For the detection of MAYV, complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated using GoScript™ Reverse Transcriptase, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Immediately, these cDNAs were used in the Real Time RT-PCR assay with SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix using a pair of primers described by Mourão et al. [27] for identification of this pathogen. Strains of DENV, CHIKV and MAYV obtained from cell culture and confirmed by sequencing were used as positive controls. Ultra-pure water served as a negative control and Ribonuclease P was used as internal control. All reactions were performed in duplicate. The reactions were carried out in the ABI 7500 Real Time PCR system. In this study, serological tests were not performed.

Confirmation of MAYV by sequencing

All the positive samples for MAYV were sequenced using Sanger-based sequencing. Firstly, conventional PCR was performed using protocol, including primers and thermal profiles previously established [27], generating a product of 201 base pairs (E1 glycoprotein). The cDNA previously generated was used as target. All reactions included positive and negative controls to ensure the reliability of the reaction. All the amplified products were sequenced using BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit. The sequences were edited and aligned using Sequencher v.5.0.1 and BioEdit v.7.1. All sequences generated were subjected to the BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) analysis using the megablast algorithm for highly similar sequences [28] and deposited in GenBank.

Statistical analysis

The percentage of women and men were determined. The mean age and Cycling threshold (Ct) with the respective standard deviations (SD) were calculated. The prevalence was presented as absolute values with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All analyses were realized in the IBM SPSS software version 21.0.

Results

Of the total number of samples analyzed in this study, we detected 6 cases of MAYV, and all these cases presented coinfection with CHIKV. The clinical features of these patients are shown in Table 1. MAYV monoinfections were not detected. Of the remaining samples, 41 cases of CHIKV monoinfection were detected, 50 cases of DENV monoinfection and 5 coinfections between CHIKV/DENV. The clinical and demographic characteristics of these participants are shown in Table 1. These findings were described in one study previously published by our group [21].

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the CHIKV or DENV monoinfected patients and CHIKV/DENV coinfected

| Clinical and demographic characteristics | Patients (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIKV (n = 41) | DENV (n = 50) | CHIKV/DENV (n = 5) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 18 (43.9) | 16 (32.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| Female | 23 (56.1) | 34 (68.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 9 (21.9) | 12 (24.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| 25–31 | 12 (29.2) | 9 (18.0) | – |

| 32–38 | 16 (39.0) | 21 (42.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| 39–45 | 4 (9.7) | 8 (16.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| Location of residence | |||

| Araguaína | 8 (19.5) | 6 (12.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Colinas do Tocantins | – | 7 (14.0) | – |

| Guaraí | – | 6 (12.0) | – |

| Nova Olinda | – | 2 (4.0) | – |

| Palmas | 14 (34.1) | 10 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| Porto Nacional | 5 (12.2) | 7 (14.0) | – |

| Presedente Kennedy | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.0) | – |

| Santa fé do Araguaína | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.0) | – |

| Tocantinópolis | – | 2 (4.0) | – |

| Wanderlândia | 11 (26.8) | 8 (16.0) | – |

| Signs and symptoms | |||

| Fever | 38 (92.6) | 41 (82.0) | 5 (100) |

| Arthralgia | 39 (95.1) | 34 (82.9) | 5 (100) |

| Exanthema | 36 (87.8) | 42 (84.0) | 5 (100) |

| Headaches | 37 (90.2) | 39 (78.0) | 5 (100) |

| Myalgia | 34 (82.9) | 43 (86.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (14.6) | 6 (12.0) | – |

| Non-purulent conjunctivitis | 14 (34.1) | 4 (8.0) | 5 (100) |

| Retro-orbital pain | 11 (26.8) | 50 (100) | 5 (100) |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (12.1) | 36 (72.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Edema | 4 (9.7) | – | – |

| Hemorrhagic manifestations | – | 32 (64.0) | – |

| Generalized body pain | 38 (92.6) | 49 (98.0) | – |

| Nausea | 16 (39.0) | 32 (64.0) | 5 (100) |

| Vomiting | 14 (34.1) | 25 (50.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Leukopenia | 11 (26.8) | 16 (32.0) | 5 (100) |

*Number of patients (% of clinical and demographic characteristics)

We observed a prevalence of 5.88% (95% CI 1.78–8.96) patients confirmed with simultaneous infection between CHIKV and MAYV. The mean age of these patients was 34.16 years (SD = 21.13). Of these six patients, 2 (33.33%) were women and 4 (66.67%) were men. The mean Cycle threshold (Ct) for CHIKV was 26.87 (SD = 10.54) and for MAYV was 29.58 (SD = 6.34). These individuals were residents of the municipalities of Colinas do Tocantins, Wanderlândia and Palmas, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical aspects of the six patients detected with simultaneous infection between CHIKV and MAYV in Tocantins/Brazil

| Patientsa | Sex | City | Clinical features | Genbank accessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0190 | F | Colina do Tocantins | Fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, rash | OM718766 |

| 0237 | M | Wanderlândia | Fever, headache, myalgia, generalized body pain, arthralgia, nausea, rash | OM718767 |

| 0802 | M | Palmas | Fever, headache, myalgia, polyarthralgia, nausea, rash, generalized body pain | OM718768 |

| 0740 | M | Palmas | Fever, headache, myalgia, generalized body pain, arthralgia, nausea, rash | OM718769 |

| 0264 | F | Colina do Tocantins | Arthralgia, fever, headache, abdominal pain, nausea, generalized body pain | OM718770 |

| 0755 | M | Palmas | Fever, headaches, myalgia, arthralgia, vomiting, generalized body pain | OM718771 |

aPatient identification numbers

The MAYV sequences generated in this study showed 95–100% identity with other; Brazilian sequences of this virus, such as HQ664947 isolated in Manaus/AM (2012), KM400591 isolated in the state of Acre (2014) and KY618130 in the state of Pará (2017). Other MAYV isolates obtained from human and arthropods in different regions of the world also showed high similarity with our sequences, as well as MK573240 from Trinidad and Tobago (1957), MK070491 from Peru (1997), MK573246 from Bolivia (1955), KJ742385 from French Guiana (2014) and KP842810 from Venezuela (2015). The six MAYV sequences obtained were deposited in GenBank and accession numbers are showed in Table 2.

Discussion

In this study, we performed one molecular screening to detection of infections by the MAYV and identified six patients coinfected with CHIKV/MAYV in the state of Tocantins. There is still little information available on the emergence of the MAYV and cases of coinfection involving this arbovirus in Brazil, especially in the northern region of the country. This is the first report of detection of coinfection between chikungunya e mayaro viruses in State of Tocantins. Thus, our study had the objective of contribute to this field of knowledge helping to inform public policies that ensure improvements in the diagnosis of arboviruses.

The emergence of MAYV has been documented in many countries of the Latin America and Caribbean [29]. During an outbreak of febrile illness with arthralgic manifestations in Venezuela in 2010, the MAYV was identified and characterized as the causative agent of the outbreak [30]. In Haiti, between 2014 and 2015, a total of 177 blood samples obtained from children with acute febrile illness were analyzed. This screening detected a child infected with MAYV [31]. One cross-sectional study conducted with 359 serum samples from patients with suspected febrile illness in Peru, in 2017, were detected 40 participants infected with MAYV [32].

In Brazil, the circulation and sporadic cases of infection by MAYV have been reported in different regions of the country. Recently, Saatkamp et al. [33] analyzed 49 serum samples from patients in the state of Pará and detected four positive cases for MAYV. Still in the northern region of the country, another case of MAYV infection in humans was detected in the state of Acre [34]. Silveira–Lacerda et al. [35] in the city of Goiânia/Goiás, Midwest region, showed a molecular epidemiology investigation of the MAYV in febrile patients from 2017 to 2018 and of a total of 375 individuals analyzed, 26 were positive for this virus. A serological survey realized to track MAYV infections in blood donors from São Carlos in the state of São Paulo, has left evidence of the circulation of this virus also in the southeast region [36]. This shows that MAYV has a wide circulation in Brazil, and this reinforces the need of the differential diagnosis for the arboviruses of importance to public health.

An important finding in our work was the detection of the coinfection between CHIKV/MAYV. Some studies show that dual infection involving these two arboviruses can cause a severe and potentially incapacitating joint disease [37]. However, we did not observe severe symptoms in the six patients with the coinfection. Fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia were the clinical aspects common in these people, corroborating a study which detected and phylogenetically characterized dual arbovirus infections among humans during a chikungunya fever outbreak in Haiti. In this work, the authors identified one coinfection with CHIKV/MAYV and pointed that these clinical features are common in both types of infection [38]. This shows that during an outbreak of CHIKV, only clinical criteria are not enough to differentiate infections between this virus and the MAYV, which makes necessary to realization of an effective differential diagnosis for these two arboviruses.

In conclusion, the molecular screening performed in this study was effective in detection of infections by mayaro virus as well as in the detection of coinfection with chikungunya virus during an outbreak occurred in State of Tocantins in 2017. In this way, our findings reinforce that MAYV circulates in urban areas causing infections in humans and that both viruses (MAYV and CHIKV) cause similar clinical conditions in the patients.

This shows also that clinical and epidemiological aspects alone are not enough to differentiate infections by these arboviruses, which makes necessary a differential diagnosis for MAYV during CHIKV outbreaks.

Limitations

This combination of concomitant circulating of arbovirus in Brazil presents a major challenge in national public Health operations regarding case confirmation. The patients of this study are adults living in different cities of the state of Tocantins. However, there are some limitations in our work due the low number of clinical samples that we received. As it was a retrospective study, we could not get complete medical information.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Central Laboratory of Public Health of Tocantins (LACEN/Tocantins) for their collaboration in this study. They also thank Dr. Almicar Tanuri and Dr. Ricardo Krouri who provided of the control samples used in this study. We are grateful to the Dr. Antônio Charlys da Costa for kindly to provide some reagents used in this work.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% Confidence Intervals

- BLAST

Basic local alignment search tool

- CAAE

Certificate of presentation of ethical appreciation

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- CHIKV

Chikungunya virus

- Ct

Cycling threshold

- DENV

Dengue virus

- ECSA

East-Central South Africa

- HDI

Human development index

- IBGE

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics

- LACEN

Central Public Health Laboratory

- MAYV

Mayaro virus

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- SD

Standard deviation

- SPSS

Statistical package for the social sciences

- TO

Tocantins

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

RSSM, RLSD, DBC, JG and MTOM were responsible for the planning and execution of the experiments performed; RSSM also interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript; JH contributed with the correction of the manuscript; MART and FAPM were responsible for processing and transport of the samples to the Laboratory of Retrovirology; RSD is the head of the Laboratory of Retrovirology where we carry out this study; FSK and SVK was involved in the planning of the experiments performed, discussion of the data and helped in writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

National Council for Scientific and Technological Development [CNPQ] [Scholarship No 167330/2018-7] and the Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo [FAPESP] [Grant No 2015/19343-0].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (CAAE: 18908719.2.0000.5505). All patients enrolled signed an informed written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The corresponding author affirms, on behalf of all authors, that there are no competing interests related to this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alva-Urcia C, Aguilar-Luis MA, Palomares-Reyes C, Silva-Caso W, Suarez-Ognio L, Weilg P, et al. Emerging and reemerging arboviruses: a new threat in Eastern Peru. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang YS, Higgs S, Vanlandingham DL. Emergence and re-emergence of mosquito-borne arboviruses. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;34:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Souza Costa MC, Siqueira Maia LM, Costa de Souza V, Gonzaga AM, De Correa Azevedo V, Ramos Martins L, et al. Arbovirus investigation in patients from Mato Grosso during zika and chikungunya virus introdution in Brazil, 2015–2016. Acta Trop. 2019;190:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vieira CJ, Silva DJ, Barreto ES, Siqueira CE, Colombo TE, Ozanic K, et al. Detection of mayaro virus infections during a dengue outbreak in Mato Grosso. Brazil Acta Trop. 2015;147:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuchi N, Heinen LB, Santos MA, Pereira FC, Slhessarenko RD. Molecular detection of mayaro virus during a dengue outbreak in the state of Mato Grosso Central-West Brazil Mem. Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109(6):820–823. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima-Camara TN. Emerging arboviruses and public health challenges in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2016;50:36. doi: 10.1590/S1518-8787.2016050006791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang G, Gao X, Gould EA. Factors responsible for the emergence of arboviruses; strategies, challenges and limitations for their control. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2015;4(3):e18. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bopp NE, Jencks KJ, Siles C, Guevara C, Vilcarromero S, Fernandez D, et al. Serological responses in patients infected with mayaro virus and evaluation of cross-protective responses against chikungunya virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sam IC, Loong SK, Michael JC, Chua CL, Wan Sulaiman WY, Vythilingam I, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of chikungunya virus of different genotypes from Malaysia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e50476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De O’Mota MT, Avilla CMS, Nogueira ML. Mayaro virus: a neglected threat could cause the next worldwide viral epidemic. Future Virol. 2019;14:375–377. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2019-0051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazilian Health Portal. Boletim epidemiológico. 2015. http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/. Accessed 20 May 2022.

- 12.Machado LC, de Morais-Sobral MC, Campos TL, Pereira MR, de Albuquerque MFPM, Gilbert C, et al. Genome sequencing reveals coinfection by multiple chikungunya virus genotypes in a recent outbreak in Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(5):e0007332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azevedo RS, Silva EV, Carvalho VL, Rodrigues SG, Neto JP, Monteiro HA, et al. Mayaro fever virus, Brazilian Amazon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(11):1830–1832. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.090461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauvolid-Corrêa A, Juliano RS, Campos Z, Velez J, Nogueira RM, Komar N. Neutralising antibodies for mayaro virus in Pantanal, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(1):125–133. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760140383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caicedo EY, Charniga K, Rueda A, Dorigatti I, Mendez Y, Hamlet A, et al. The epidemiology of mayaro virus in the Americas: a systematic review and key parameter estimates for outbreak modelling. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coimbra TL, Santos CL, Suzuki A, Petrella SM, Bisordi I, Nagamori AH, et al. Mayaro virus: imported cases of human infection in São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49(4):221–224. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652007000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.da Costa VG, de Rezende Féres VC, Saivish MV, de Lima Gimaque JB, Moreli ML. Silent emergence of mayaro and oropouche viruses in humans in Central Brazil. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;62:84–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figueiredo LTM. Large outbreaks of chikungunya virus in Brazil reveal uncommon clinical features and fatalities. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017;50(5):583–584. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0397-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguilar-Luis MA, Valle-Mendoza JD, Sandoval I, Silva-Caso W, Mazulis F, Carrillo-Ng H, et al. A silent public health threat: emergence of mayaro virus and co-infection with dengue in Peru. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14:29. doi: 10.1186/s13104-021-05444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lobkowicz L, Ramond A, Sanchez Clemente N, Ximenes RAA, Miranda-Filho DB, Montarroyos UR, et al. The frequency and clinical presentation of zika virus coinfections: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5):e002350. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dos Santos S, Marinho R, Sanz Duro RL, Santos GL, Hunter J, Da Aparecida RTM, Brustulin R, et al. Detection of coinfection with chikungunya virus and dengue virus serotype 2 in serum samples of patients in State of Tocantins Brazil. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics—IBGE. 2018. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/to/panorama. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

- 23.World Health Organization—WHO. Information on arboviruses in the region of the Americas. 2019. https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=comcontent&view=article&id=12905:informationarbovirusesregio-americas&Itemid=42243&lang=pt. Accessed 8 Feb 2022.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC. Diagnostic testing. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/hc/diagnostic.html. Accessed 8 Feb 2022.

- 25.Alm E, Lindegren G, Falk KI, Lagerqvist N. One-step real-time RT-PCR assays for serotyping dengue virus in clinical samples. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:493. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1226-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cecilia D, Kakade M, Alagarasu K, Patil J, Salunke A, Parashar D, et al. Development of a multiplex real time RT-PCR assay for simultaneous detection of dengue and chikungunya viruses. Arch Virol. 2015;160(1):323–327. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mourão MP, Bastos Mde S, de Figueiredo RP, Gimaque JB, Galusso Edos S, Kramer VM, et al. Mayaro fever in the city of Manaus, Brazil, 2007–2008. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12(1):42–46. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganjian N, Riviere-Cinnamond A. Mayaro virus in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e14. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auguste AJ, Liria J, Forrester NL, Giambalvo D, Moncada M, Long KC, et al. Evolutionary and ecological characterization of mayaro virus strains isolated during an outbreak, Venezuela, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(10):1742–1750. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.141660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lednicky J, De Rochars VM, Elbadry M, Loeb J, Telisma T, Chavannes S, et al. Mayaro virus in child with acute febrile illness, Haiti, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(11):2000–2002. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.161015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguilar-Luis MA, Del Valle-Mendoza J, Silva-Caso W, Gil-Ramirez T, Levy-Blitchtein S, Bazán-Mayra J, et al. An emerging public health threat: mayaro virus increases its distribution in Peru. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saatkamp CJ, Rodrigues LRR, Pereira AMN, Coelho JA, Marques RGB, Souza VC, et al. Mayaro virus detection in the western region of Pará state. Brazil Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2021;54:e0055–2020. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0055-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terzian AC, Auguste AJ, Vedovello D, Ferreira MU, da Silva-Nunes M, Sperança MA, et al. Isolation and characterization of mayaro virus from a human in Acre. Brazil Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(2):401–404. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Paula S-L, Laschuk Herlinger A, Tanuri A, Rezza G, Anunciação CE, Ribeiro JP, et al. Molecular epidemiological investigation of mayaro virus in febrile patients from Goiania City, 2017–2018. Infect Genet Evol. 2021;95:104981. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romeiro MF, Fumagalli MJ, Dos Anjos AB, Figueiredo LTM. Serological evidence of mayaro virus infection in blood donors from São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;114(9):686–689. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Z, Lang D. The effectiveness of disease management interventions on health-related quality of life of patients with established arthritogenic alphavirus infections: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2013;11(56–72):3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.White SK, Mavian C, Elbadry MA, De Beau Rochars VM, Paisie T, Telisma T, et al. Detection and phylogenetic characterization of arbovirus dual-infections among persons during a chikungunya fever outbreak, Haiti 2014. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(5):e0006505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.