Abstract

The 5′ end of the Enterococcus faecalis pyr operon specifies, in order, the promoter, a 5′ untranslated leader, the pyrR gene encoding the regulatory protein for the operon, a 39-nucleotide (nt) intercistronic region, the pyrP gene encoding a uracil permease, a 13-nt intercistronic region, and the pyrB gene encoding aspartate transcarbamylase. The 5′ leader RNA is capable of forming stem-loop structures involved in attenuation control of the operon. No attenuation regions, such as those found in the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon, are present in the pyrR-pyrP or pyrP-pyrB intercistronic regions. Several lines of evidence demonstrate that the E. faecalis pyr operon is repressed by uracil via transcriptional attenuation at the single 5′ leader termination site and that attenuation is mediated by the PyrR protein.

The pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthetic (pyr) operon in Bacillus subtilis is regulated by an autogenous transcriptional attenuation mechanism in which the first gene of the operon, pyrR, encodes a regulatory protein that causes transcriptional termination by binding in a uridine nucleotide-dependent manner to three specific sites in the pyr mRNA (9, 19, 21). These sites are located in the 5′ untranslated leader of the operon, between the first (pyrR) and second (pyrP) cistrons, and between the second and third (pyrB) cistrons of the operon (11, 21). The same arrangement of genes and regulatory sites is found in the Bacillus caldolyticus pyr operon (4, 5). A similar attenuation mechanism appears to regulate pyr genes in Lactococcus lactis (1) and in Lactobacillus plantarum (2), but different organizations of the pyr genes and attenuation sites are found in these cases. Regulation of pyr genes by transcriptional attenuation in bacteria has been reviewed by Switzer et al. (19).

The occurrence of transcriptional attenuation mechanisms for regulating pyr genes in various gram-positive bacteria suggests that they might also be found in medically important gram-positive pathogenic genera. A strong indication that such is the case was provided by the work of Li et al. (8), who showed that the pyr genes in Enterococcus faecalis are organized into a cluster like that found in Bacillus spp. and that the sequence of a portion of the first gene in the cluster indicated its probable identity as a PyrR regulatory protein homologue. The sequence data were not sufficiently complete to allow further characterization of the regulation, however. As pointed out by Li et al. (8), enterococci are a frequent cause of serious infections, and antibiotic-resistant strains present a growing problem in therapy. Since a capacity for de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for the virulence of some bacteria (3), an understanding of the regulation of this pathway in enterococci may aid in development of novel approaches to controlling their virulence.

Structure of the 5′ end of the E. faecalis pyr gene cluster.

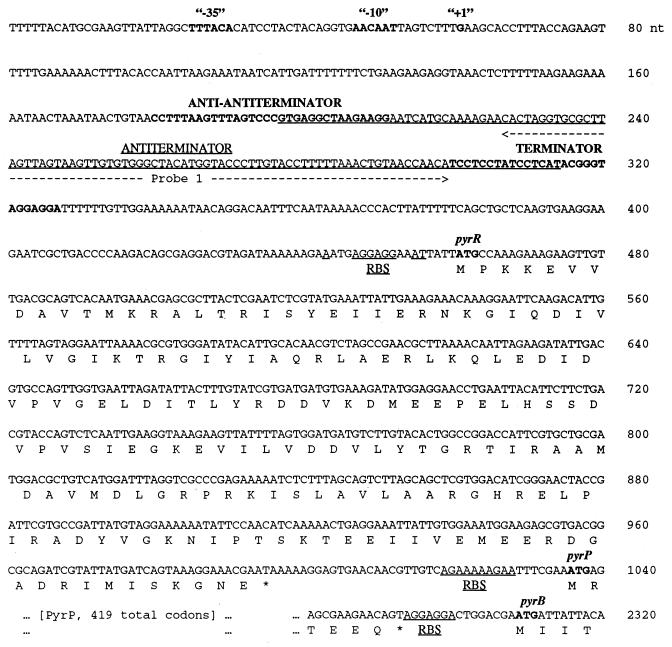

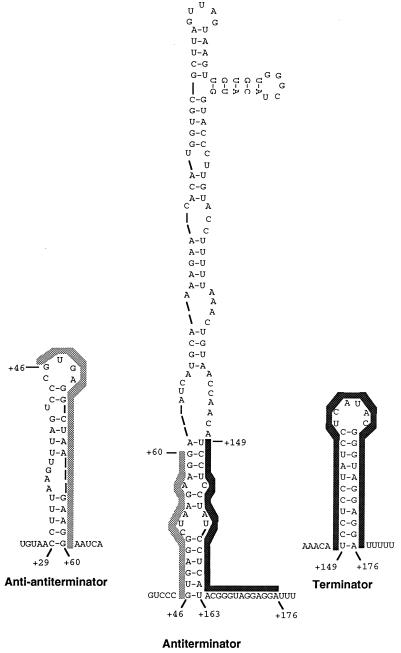

E. faecalis DNA specifying the 5′ end of the pyr gene cluster was subcloned from the pBEM215 plasmid, kindly provided by Barbara E. Murray (8), and the nucleotide sequence of a 2.6-kbp contiguous segment was determined (Fig. 1). A putative promoter with good matches to consensus sequences for gram-positive bacterial promoters (Fig. 1) is followed by a 400-nucleotide (nt) untranslated leader sequence that precedes the first open reading frame, which encodes a PyrR homologue. It should be noted that at least two other regions downstream from this putative promoter site also fit reasonably well to promoter consensus sequences, but the promoter shown in Fig. 1 was selected as more probable because its location predicts the length of the attenuated transcript from the 5′ end of the operon that was detected on Northern blot analysis, as described below. In analogy to the sequence of the 5′ end of pyr mRNA from B. subtilis (10, 21), the 5′ leader mRNA can be folded into three hairpin secondary structures (Fig. 2) whose positions and sequences suggest that they are capable of functioning as a transcription terminator, an antiterminator, and an anti-antiterminator (Fig. 1). The terminator is a typical RNA hairpin structure with a stem rich in G-C base pairs, followed on the 3′ side by a series of U residues in the mRNA (Fig. 2). The upstream antiterminator is predicted to form a large hyphenated hairpin (Fig. 2). The trailing strand of the stem of this structure overlaps the 5′ strand of the terminator, so that formation of the antiterminator structure would prevent the terminator from forming, as is typical of attenuation systems of this type (19). The anti-antiterminator hairpin is formed by alternative folding of the 5′ strand of the antiterminator structure (Fig. 2), so that its formation would disrupt base pairing in the antiterminator stem and release the nucleotides needed to form the terminator. Furthermore, the sequence of nucleotides in the terminal loop of the anti-antiterminator (CCUUUAAGUUUAGUCCCGUGAGGCUAGGAAGGA) fits well with the consensus sequence (underlined) in the same position of 10 other known pyr anti-antiterminator structures. This region of B. subtilis pyr mRNA is the site of binding of the PyrR regulatory protein (10, 20).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the DNA encoding the 5′ end of the E. faecalis pyr operon. Deduced amino acid sequences for the protein encoded by the pyrR gene, the 5′ and 3′ ends of the pyrP gene, and the 5′ end of the pyrB gene are shown in single letter code below the DNA sequences of the genes, with the start codons in boldface type and putative ribosome binding sites (RBS) underlined. Transcription termination codons are indicated with asterisks. The presumed promoter for the operon is shown in boldface type, consensus RNA polymerase recognition elements are indicated with “−35” and “−10,” and the likely start of transcription is designated “+1.” The sequences specifying the proposed anti-antiterminator and terminator stem-loop structures in pyr mRNA are indicated in boldface type, and the sequence specifying the proposed antiterminator stem-loop is underlined. The sequence complementary to the deoxyribonucleotide probe, probe 1, used in Northern hybridization analysis (Fig. 3) is indicated with a dashed line.

FIG. 2.

Postulated secondary structures in the E. faecalis pyr 5′ leader mRNA. The anti-antiterminator and terminator structures can exist simultaneously, but both are disrupted by formation of the antiterminator structure. The RNA sequences denoted by the lightly shaded bars are identical, as are those denoted by the darkly-shaded bars, demonstrating that the two alternative sets of secondary structures are mutually exclusive.

The first open reading frame, pyrR, is preceded by an appropriately located ribosome binding site and encodes a protein of 178 residues with 60 and 73% amino acid sequence identity to the PyrR proteins from B. subtilis and L. plantarum, respectively. Several other bacterial PyrR sequences are compared to the E. faecalis PyrR sequence in reference 19. The pyrR gene is separated from the downstream open reading frame, pyrP, by a 39-nt intercistronic region, which is not predicted to fold into any of the secondary structures needed to form a functional attenuation region. The pyrP open reading frame is preceded by a ribosome binding site and is composed of 419 codons. The PyrP protein is identifiable as a uracil permease from its sequence similarity to other known uracil permeases (4, 21). A hydropathy plot (not shown) of the deduced amino acid sequence of E. faecalis PyrP predicts that it, like other uracil permeases, is capable of forming 12 hydrophobic transmembrane helices. The pyrP gene is separated from the downstream gene, pyrB, encoding aspartate transcarbamylase, by only 13 nt. This intercistronic region also lacks the structural features of an attenuation region. Thus, the 5′ end of the E. faecalis pyr operon differs from the corresponding regions from the pyr operons of other bacteria (19) in one important respect: the E. faecalis pyr operon has only one attenuation region, which is located in its 5′ untranslated leader.

Repression of E. faecalis pyr genes by uracil in vivo.

E. faecalis OG1RF, kindly provided by Barbara E. Murray, was grown on the defined medium described by Murray et al. (14) with or without supplementation with 150 μg of uracil per ml. The cultures were grown with a 3% inoculum from a beef heart infusion culture. The cells were harvested after 2.5 h of growth at 37°C and disrupted by sonic oscillation, and the centrifuged extracts were assayed for aspartate transcarbamylase activity by the procedure of Shindler and Prescott (17). The specific activity of the cells grown without uracil (140 nmol of carbamyl-l-aspartate per min per mg of protein) was 30 times that of cells grown in uracil-supplemented medium (4.5 nmol of carbamyl-l-aspartate per min per mg of protein). This clearly documents that expression of the E. faecalis pyr operon is repressed by exogenous uracil.

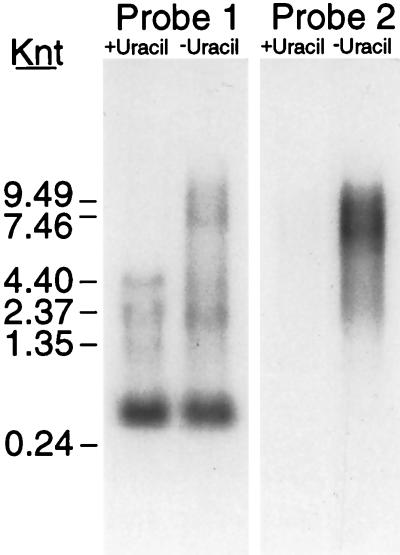

To determine whether repression results from transcriptional attenuation, as proposed in the preceding paragraph, total RNA was extracted (16) from strain OG1RF cells grown with and without 150 μg of uracil per ml of medium, as described above. This RNA was subjected to electrophoresis, the electropherogram was blotted, and the blot was probed with 32P end-labeled deoxyribonucleotides (12) which were complementary to E. faecalis pyr mRNA nt 227 to 299 (probe 1, complementary to the 5′ leader transcript upstream of the putative transcription terminator [Fig. 1]) and nt 2367 to 2428 (probe 2, complementary to the pyrB open reading frame [not shown]). Thus, probe 1 is expected to hybridize to all pyr transcripts, whereas probe 2 should not hybridize to those transcripts that are terminated within the 5′ leader. As seen in the Northern blot (Fig. 3), probe 1 detected a short transcript (estimated at about 270 nt) in uracil-grown cells and a somewhat smaller amount of the same transcript (about 90% of the amount found in uracil-grown cells) and small amounts of much longer transcripts in the cells grown without uracil. Probe 2 hybridized only to the longer transcripts, as expected, and these were detected only in cells grown without uracil. The length of the short transcript is consistent with the postulated transcription start site and terminator location in Fig. 1 (268 nt). These observations are consistent with the presence of a uracil-regulated attenuation site in the 5′ leader. The length of the longest transcript was estimated to be about 9.5 knt, whereas the full length transcript would be about 11 to 12 knt (8). The range of sizes of the transcripts detected with probe 2 probably reflects degradation of the full-length pyr transcript in vivo.

FIG. 3.

Northern hybridization analysis of pyr transcripts from E. faecalis OG1RF cells grown on medium (14) with and without 150 μg of uracil per ml. Probe 1 is complementary to nt 227 to 299 in the 5′ leader (Fig. 1), and probe 2 is complementary to nt 2367 to 2428 in the pyrB open reading frame.

Transcriptional attenuation by E. faecalis PyrR in vivo.

To demonstrate the ability of the E. faecalis PyrR protein to function in vivo as a pyrimidine-responsive attenuation regulatory protein, we examined its capacity to restore normal regulation to a B. subtilis strain in which the pyrR gene has been deleted (21). Aspartate transcarbamylase activity in this strain is very high and resistant to repression by exogenous uracil (Table 1). When the pEFG2 plasmid, which contains the E. faecalis pyr promoter, 5′ leader, and pyrR gene inserted into pHPS9 (7), was introduced into the B. subtilis ΔpyrR strain, regulation of the B. subtilis pyr genes by endogenous and exogenous pyrimidines was observed. The same result was obtained with pEFG3, in which the same segment of E. faecalis DNA was inserted into pHPS9 in the opposite orientation, which indicates that expression of E. faecalis pyrR was driven from the E. faecalis pyr promoter. The ability of the E. faecalis PyrR protein to regulate transcriptional attenuation in B. subtilis suggests that this protein regulates its own pyr attenuation by a similar mechanism.

TABLE 1.

E. faecalis pyrR restores regulation by pyrimidines to a B. subtilis ΔpyrR straina

| Plasmidb | Sp act of aspartate transcarbamylase (nmol/min/mg of protein)

|

Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without uracil | With uracil | ||

| pHPS9 | 2,630 | 2,580 | 1.0 |

| pEFG2 | 167 | 22 | 7.6 |

| pEFG3 | 162 | 29 | 5.6 |

Cells of B. subtilis DB104 ΔpyrR (21) transformed with the indicated plasmid were grown at 37°C on minimal medium (18) containing 0.5% glucose, 0.1% glutamate, and 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml to midlog phase with or without 50 μg of uracil per ml. Cells were harvested, extracted, and assayed for aspartate transcarbamylase activity, as described by Ghim and Switzer (6).

The pHPS9 vector has been previously described (7). The other plasmids were constructed as follows. First, a 1.16-kbp fragment of DNA specifying the E. faecalis pyr promoter, 5′ leader sequence, and complete pyrR gene was amplified by PCR with pBEM215 as the template. This fragment had a BamHI site added to the PCR primer at one end and included the natural HindIII site at nt 1073 to 1078 (Fig. 1) at the other end. The PCR fragment was inserted into pUC18 (15), generating pEFG1. pEFG2 and pEFG3 were constructed by isolation of the 1.16-kbp BamHI/HindIII fragment of pEFG1, filling in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and insertion into the SmaI site of pHPS9. In pEFG2, the pyr promoter is in the same orientation as the vector-borne P59 promoter; pEFG3 contains the same insert as pEFG2 but in the opposite orientation.

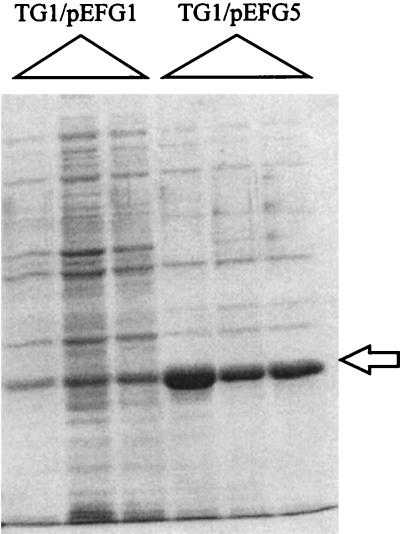

Removal of the attenuator increases production of recombinant E. faecalis PyrR.

A plasmid was constructed in which the bulk of the 5′ leader region between the pyr promoter and the pyrR gene was deleted so that no attenuation of transcription could occur. This plasmid was derived from pEFG1, which contains a 1.16-kb DNA fragment that specifies the E. faecalis pyr promoter, 5′ leader, and complete pyrR gene in the pUC18 (15) vector (construction of pEFG1 is described in Table 1, footnote b). PCR primers were designed for amplification of all of the pEFG1 DNA except for the attenuation region between nt 205 and 400 (Fig. 1) by using primers with engineered XbaI 5′ ends. The amplified PCR product was digested with XbaI to generate a linear product with cohesive ends, which was self-ligated to yield the desired plasmid, pEFG5, identical to the parent pEFG1 plasmid except for the 195-bp deletion from the pyr attenuation region. Escherichia coli TG1 was then transformed with plasmids pEFG5 and pEFG1. A very high level of PyrR was produced in E. coli TG1/pEFG5; we estimate that as much as 50% of the cell protein was PyrR (Fig. 4). The fact that much more PyrR was produced in TG1/pEFG5 cells than in TG1/pEFG1 cells (Fig. 4) indicates that the attenuation region in the 5′ leader functions to reduce expression of downstream genes.

FIG. 4.

Deletion of pyr attenuation sequences leads to overproduction of PyrR. Extracts of E. coli TG1 (12) bearing pEFG1, which contains the complete 5′ leader, or pEFG5, from which the leader was deleted, grown to late log phase on Luria-Bertani medium (13) containing 100 μg of Timentin (a mixture of ticarcillin and clavulanic acid that was included to help maintain a high plasmid copy number) per ml, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Triplicate cultures were examined to evaluate reproducibility. The position of migration of PyrR is shown by the arrow.

Properties of the purified E. faecalis PyrR protein.

The pEFG5 plasmid was introduced into E. coli SØ408 (relA1 rpsL254 metB1 upp-11) (from J. Neuhard, University of Copenhagen) for overproduction of PyrR, which was purified by a modification of the procedure developed by Turner et al. for purification of recombinant B. subtilis PyrR (20). There were two significant differences in the behavior of PyrR from these two sources. B. subtilis PyrR precipitated between 35 and 65% saturation with ammonium sulfate, whereas greater than 70% saturation was required to precipitate E. faecalis PyrR. Also, elution of E. faecalis PyrR from Q-Sepharose FF (Pharmacia) required significantly higher NaCl concentrations than needed to elute B. subtilis PyrR. The purified PyrR was at least 95% pure on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (not shown).

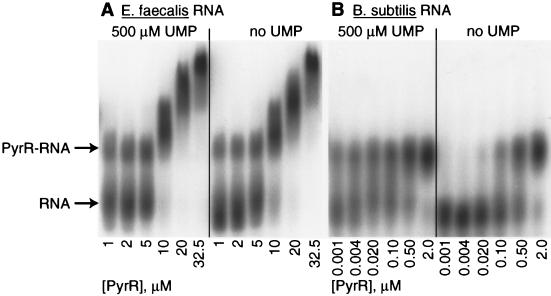

Purified E. faecalis PyrR was shown by electrophoretic gel mobility shift analysis, with procedures previously described by Turner et al. (20), to bind to a 73-nt segment of E. faecalis pyr RNA corresponding to the anti-antiterminator region of the 5′ leader (nt 160 to 232 [Fig. 1]). The pattern of binding was complex and appeared to consist of two phases (Fig. 5A). The first PyrR-RNA complex formed at roughly 1 to 5 μM PyrR (50 pM RNA), and a second, more highly shifted complex formed at higher PyrR concentrations. The second complex is probably an artifact of PyrR aggregation at the very high concentrations used in the gel shift assays, because a similar, more highly shifted complex was formed with B. subtilis pyr anti-antiterminator RNA when bound to PyrR from either E. faecalis or B. subtilis at concentrations above 5 μM (data not shown). However, even with such high concentrations of PyrR, no gel-shifted complexes were detected with the other RNA species described below (20). Whereas the addition of UMP stimulated PyrR binding to B. subtilis RNA quite well (next paragraph), it stimulated binding to E. faecalis RNA only slightly. For example, the levels of RNA bound to 1 μM PyrR were 15% in the absence of UMP and 24% in the presence of 0.5 mM UMP, as determined from quantitation of the gel shift pattern in Fig. 5 with a PhosphorImager.

FIG. 5.

Binding of purified E. faecalis PyrR to pyr anti-antiterminator mRNA from E. faecalis and B. subtilis. Electrophoretic gel mobility shift analysis was used as described by Turner et al. (20) with 50 pM RNA, no UMP or 500 μM UMP, and the concentrations of purified E. faecalis PyrR shown in the figure. (A) E. faecalis pyr anti-antiterminator RNA. This RNA was prepared by PCR amplification of nt 160 to 232 from pEFG1 with an EcoRI site and T7 promoter on the 5′ side and a BamHI site on the 3′ side, followed by ligation into pUC18. The plasmid product was linearized with BamHI and used as a template for in vitro transcription. The RNA was isolated as described previously (20). (B) B. subtilis pyr anti-antiterminator RNA from pBSBL2 (20). The positions of unbound [32P]pyr RNA and the PyrR-RNA complex after electrophoresis are shown with arrows. Although it is not shown in this figure, no shift in the RNA was seen when no PyrR was added.

We also tested binding of E. faecalis PyrR to an 80-nt B. subtilis pyr mRNA segment derived from the pyrR-pyrP intercistronic attenuation region, which contains the conserved sequence found in the anti-antiterminator identified in the E. faecalis 5′ leader RNA and has been shown to bind tightly to B. subtilis PyrR (20). PyrR bound much more tightly to this RNA than to the E. faecalis pyr RNA described in the preceding paragraph. In this case, only a single complex was observed (Fig. 5B). The apparent dissociation constants for the complex were about 270 nM in the absence of UMP and about 4 nM in the presence of 0.5 mM UMP. The binding of PyrR to the anti-antiterminator RNA was highly specific. Three control RNAs, described by Turner et al. (20), all failed to bind significantly under the same conditions (data not shown).

Purified E. faecalis PyrR catalyzes substantial uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRTase) activity. At pH 9.2, the pH optimum for UPRTase activity, the maximal velocity at saturating substrate concentrations was 6 μmol per min per mg of protein, a value which is about 75% of that seen for B. subtilis PyrR at the same pH. As with the UPRTase activity of B. subtilis PyrR (20), the steady-state kinetics of the E. faecalis PyrR-catalyzed UPRTase fit best to a Ping Pong Bi Bi rate equation. The UPRTase activity of E. faecalis PyrR was described by Michaelis constants for uracil and PRPP (5-phosphoribosyl-α-1-pyrophosphate) of 2,500 ± 470 and 750 ± 130 μM, respectively, at pH 9.2. The corresponding values for B. subtilis PyrR at pH 9.2 were 98 ± 14 μM and 104 ± 14 μM, respectively (20). These very large values for the Michaelis constants for E. faecalis PyrR, which are substantially larger than the probable intracellular concentrations of their corresponding metabolites, lead us to suggest that the UPRTase activity of PyrR is not physiologically important for uracil salvage in E. faecalis. The high Michaelis constant for uracil is not an artifact of assaying the enzyme at pH 9.2, because this value was much higher (4 ± 0.8 mM) at pH 7.7, and the maximal velocity was much lower (1.3 μmol per min per mg).

Although the experiments described here do not establish the regulation of the E. faecalis pyr operon by transcriptional attenuation as fully as has been done with the B. subtilis pyr operon (9–11, 19–21), our findings make it virtually certain that essentially the same regulatory mechanism governs pyr operon expression in both organisms. Since E. faecalis PyrR has been demonstrated to regulate B. subtilis pyr genes in response to exogenous pyrimidines in vivo and the Northern maps of E. faecalis pyr transcripts are consistent with the proposed attenuation mechanism, there can be little question that PyrR regulates expression of the E. faecalis pyr operon. E. faecalis PyrR binds to the expected RNA sequences from the E. faecalis pyr attenuation region in vitro with high specificity. Curiously, E. faecalis PyrR binds the corresponding RNA from a heterologous B. subtilis attenuation region much more tightly than the homologous RNA, and only binding to the heterologous RNA is appreciably stimulated by UMP. The binding of E. faecalis RNA by E. faecalis PyrR has not been characterized in detail.

More interesting than the similarities between the systems are their differences. Operons encoding pyr genes from gram-positive organisms that are regulated by PyrR-dependent attenuation at one (E. faecalis [this work]), two (L. plantarum, which lacks a pyrP gene [2]), or three (B. subtilis [11] and B. caldolyticus [4]) sites in their operons have now been described. All three arrangements presumably provide adequate regulation of the pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes for their host organisms. Since the effects of pyr attenuators in tandem are cumulative (11), one would predict that the most stringent control, as expressed by the ratio of fully derepressed to fully repressed activity of pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes, would be found in the Bacillus species. It is also to be expected that repression of E. faecalis genes would not be complete; some transcriptional readthrough of the single attenuator is needed in all of the species to allow sufficient synthesis of PyrR for regulation of the operon. Another variant of this theme is found in L. lactis, in which the pyr genes are scattered among several small operons, at least one of which appears to be regulated by a single attenuation region in its 5′ leader, although the L. lactis pyrR gene has not yet been found (1). The degree of repressive control by pyrimidines of these various PyrR-dependent attenuation regions has not been compared quantitatively under experimentally equivalent conditions. It would be interesting to learn whether there are quantitative differences among them and, if so, whether the differences correlate with the predicted stabilities of the secondary structures which they form.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence determined in this study has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF044978.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge James H. Hageman for valuable assistance with preparation of the manuscript and of Fig. 2.

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant GM47112 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Eric Bonner was supported by a fellowship from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen P S, Martinussen J, Hammer K. Sequence analysis and identification of the pyrKDbF operon from Lactococcus lactis including a novel gene, pyrK, involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5005–5012. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.5005-5012.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elagöz A, Abdi A, Hubert J-C, Kammerer B. Structure and organisation of the pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway genes in Lactobacillus plantarum: a PCR strategy for sequencing without cloning. Gene. 1996;182:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fields P I, Swanson R V, Haidaris C G, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghim S-Y, Neuhard J. The pyrimidine biosynthesis operon of the thermophile Bacillus caldolyticus includes genes for uracil phosphoribosyltransferase and uracil permease. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3698–3707. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3698-3707.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghim S-Y, Nielsen P, Neuhard J. Molecular characterization of pyrimidine biosynthesis genes from the thermophile Bacillus caldolyticus. Microbiology. 1994;140:479–491. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-3-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghim S-Y, Switzer R L. Characterization of cis-acting mutations in the first attenuator region of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon that are defective in regulation of expression by pyrimidines. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2351–2355. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2351-2355.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haima P, Sinderen D V, Bron S, Venema G. An improved β-galactosidase α-complementation system for molecular cloning in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1990;93:41–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90133-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Weinstock G M, Murray B E. Generation of auxotrophic mutants of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6866–6873. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6866-6873.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Y, Switzer R L. Transcriptional attenuation of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon by the PyrR regulatory protein and uridine nucleotides in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7206–7211. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7206-7211.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Y, Turner R J, Switzer R L. Function of RNA secondary structures in transcriptional attenuation of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14462–14467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, Turner R J, Switzer R L. Roles of the three transcriptional attenuators of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic operon in the regulation of its expression. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1315–1325. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1315-1325.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. p. 4.14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. pp. 353–355. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray B E, Singh K V, Ross R P, Heath J D, Dunny G M, Weinstock G M. Generation of restriction map of Enterococcus faecalis OG1 and investigation of growth requirements and regions encoding biosynthetic function. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5216–5223. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5216-5223.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene. 1983;26:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimotsu H, Kuroda M I, Yanofsky C, Henner D J. Novel form of transcription attenuation regulates expression of the Bacillus subtilis tryptophan operon. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:461–471. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.461-471.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shindler D B, Prescott L M. Improvements on the Prescott-Jones method for the colorimetric analysis of ureido compounds. Anal Biochem. 1979;97:421–422. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spizizen J. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:1072–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Switzer R L, Turner R J, Lu Y. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic operon by transcriptional attenuation: control of gene expression by an mRNA-binding protein. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1999;62:329–367. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner R J, Bonner E R, Grabner G K, Switzer R L. Purification and characterization of Bacillus subtilis PyrR, a bifunctional pyr mRNA-binding attenuation protein/uracil phosphoribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5932–5938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner R J, Lu Y, Switzer R L. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic (pyr) gene cluster by an autogenous transcriptional attenuation mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3708–3722. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3708-3722.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]