Abstract

Introduction

Chondral defects of the knee are common and their treatment is challenging.

Source of data

PubMed, Google scholar, Embase and Scopus databases.

Areas of agreement

Both autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) and membrane-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (mACI) have been used to manage chondral defects of the knee.

Areas of controversy

It is debated whether AMIC and mACI provide equivalent outcomes for the management of chondral defects in the knee at midterm follow-up. Despite the large number of clinical studies, the optimal treatment is still controversial.

Growing points

To investigate whether AMIC provide superior outcomes than mACI at midterm follow-up.

Areas timely for developing research

AMIC may provide better outcomes than mACI for chondral defects of the knee. Further studies are required to verify these results in a clinical setting.

Keywords: Knee, chondral defect, mACI, AMIC

Introduction

Hyaline cartilage tissue is alymphatic and hypocellular, with low metabolic activity and limited regenerative capabilities.1–3 The healing process of chondrocytes often does not result in restitutio ad integrum, and residual chondral defects or a fibrotic scar are frequent.4,5 Focal chondral defects of the knee are debilitating, leading to marked decline in quality of life and, in athletes, a high chance of retirement from sport.6,7 Conservative strategies are often not adequate to manage focal chondral defects of the knee.8,9 Thus, surgical management is often required.10,11 Several different surgical strategies have been proposed to manage focal chondral defects of the knee.12–14 After its introduction, membrane-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (mACI) has been broadly performed.11,15,16 In 2005, Behrens17 first described an enhanced microfractures technique, which quickly evolved into the autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) procedure. Given its simplicity, AMIC quickly gained the favour of surgeons and patients.18 To the best of our knowledge, no previous study compared these two strategies in a clinical setting for chondral defect of the knee. AMIC was supposed to perform better than the mACI procedure; however, no consensus has been reached, and updated evidenced-based recommendations are required. Thus, a systematic review was conducted to investigate whether AMIC provides better outcomes than mACI for knee chondral defects at midterm follow-up. This study focused on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and complication rates. We hypothesized that AMIC and mACI procedures provided equivalent clinical outcome.

Method

Search strategy

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).19 The PICO algorithm was preliminarily stated:

P (Problem): knee chondral defect;

I (Intervention): chondral regeneration;

C (Comparison): AMIC versus mACI;

O (Outcomes): PROMs and complications.

Data source and extraction

The literature search was conducted by two authors (Filippo Migliorini1 and Jörg Eschweiler) separately in January 2022. The following databases were accessed: PubMed, Google scholar, Embase and Scopus. The following keywords were used in combination: chondral, cartilage, articular, damage, defect, injury, chondropathy, knee, pain, matrix-induced, autologous, chondrocyte, transplantation, implantation, mACI, AMIC, therapy, management, surgery, outcomes, hypertrophy, failure, revision, reoperation, recurrence. The same authors independently screened the resulting articles from the search. The full-text of the articles of interest was accessed. A cross-reference of the bibliographies was also performed. Disagreements between the two authors were solved by a third author (Nicola Maffulli).

Eligibility criteria

All the studies investigating the outcomes of AMIC and/or mACI for knee chondral defects were accessed. Given the authors language abilities, articles in English, Italian, French, Spanish and German were eligible. Levels I to IV of evidence studies, according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine,20 were suitable. Only studies investigating a minimum of five patients were included. Abstracts, reviews, letters, opinion, editorials and registries were excluded. Biomechanics, animals or in vitro studies were not considered. Only studies that used a cell-free bioresorbable membrane were considered. Studies augmenting AMIC or mACI with less committed cells (e.g. bone marrow concentrate, mesenchymal stem cells) or grow factors were not considered. Studies involving patients with kissing lesions were not included, nor were those involving patients with end-stage osteoarthritis. Only studies that clearly stated the duration of the follow-up were eligible. Only studies which reported quantitative data with regards to the outcomes of interest were included in this study.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted independently by two authors (Filippo Migliorini1 and Jörg Eschweiler). Generalities of the included studies (author and year, journal, study design) and patients demographic at baseline were collected (length of symptoms prior of treatment, number of procedures, mean body mass index (BMI) and age of the patients, length of the follow-up, gender, mean defect size). For each of the two techniques, the following data were retrieved: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Tegner Activity Scale,21 International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC)22 and the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale.23 Data regarding the following complications were also collected: rate of hypertrophy, failures, revision surgeries and total knee arthroplasty. The recurrence of symptomatic chondral defects which affect negatively the patient quality of life was considered as failure.

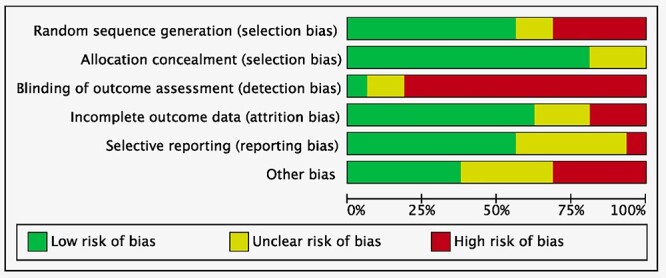

Methodology quality assessment

The methodological quality assessment was accomplished by two independent authors (Filippo Migliorini1 and Jörg Eschweiler). The risk of bias graph tool of the Review Manager Software (The Nordic Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen) was used. The following risks of bias were evaluated: selection, detection, attrition, reporting and other sources of bias.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Version 25. Continuous data were reported as mean difference (MD), while binary data were evaluated using the odd ratio (OR) effect measure. The confidence interval (CI) was set at 95% in all the comparisons. T-test and  2 were evaluated for continuous and binary data, respectively, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

2 were evaluated for continuous and binary data, respectively, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Search result

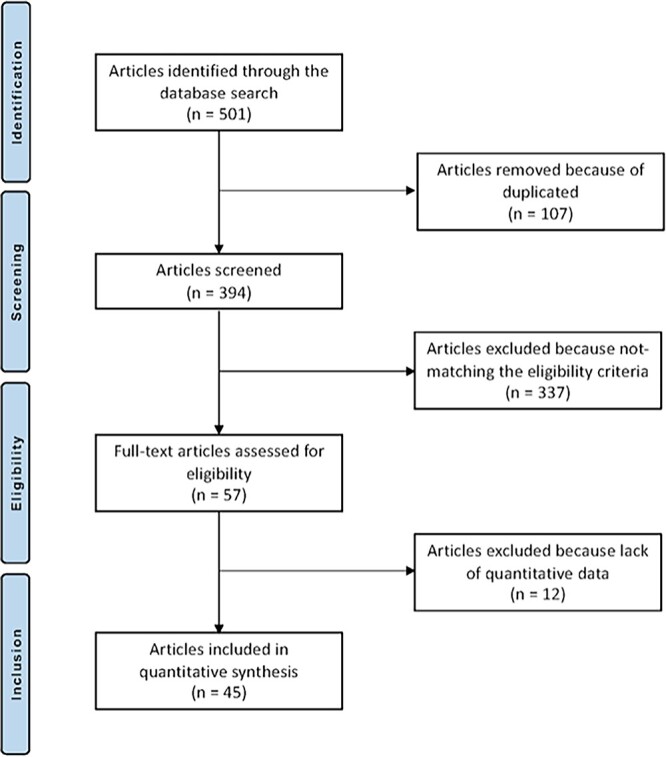

A total of 503 articles were initially obtained and 107 were excluded as they were duplicates. A further 349 articles were excluded because they did not match the inclusion criteria: not focused on mACI or AMIC (N = 225), not focusing on knee (N = 37), study design (N = 51), not reporting quantitative data under the outcomes of interest (N = 12), combined with other committed cells (N = 12), other (N = 8), language limitations (N = 3), not clearly stating the duration of the follow-up (N = 1). Finally, 47 articles were available for this study. The results of the literature search are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the literature search.

Methodological quality assessment

As 27% (12 of 45) of the investigations were randomized clinical trials, and 20% (9 of 45) were retrospective studies, the risk of selection bias of random sequence generation was moderate. The overall risk of selection bias of allocation concealment was low. Given the overall lack of blinding, detection bias was moderate-high. The risk of attrition and reporting bias across all included studies was low, as was the risk of other bias. In conclusion, the risk of bias was moderate, attesting to this study acceptable methodological assessment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Methodological quality assessment.

Patient demographics

Data from 1667 procedures were retrieved; 36% (600 of 1667 patients) were women. The mean follow-up was 37.9 ± 21.7 months. The mean age of the patients was 34.7 ± 6.5, and the mean BMI 25.5 ± 1.6 kg/m2. The mean defect size was 3.9 ± 1.2 cm2. Generalities and demographics of the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Generalities and demographics of the included studies

| Author, year | Journal | Study Design | Follow-up (months) | Treatment | Procedures (n) | Female (%) | Mean age | Mean BMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akgun et al. 2015 28 | Arch Orthop Trauma Surg | Prospective, Randomized | 24 | Control Group | 7 | 57 | 32 | 24.1 |

| mACI | 7 | 57 | 32 | 24.3 | ||||

| Anders et al. 2013 64 | Open Orthop J | Prospective, Randomized | 24 | AMIC | 8 | 12 | 35 | 27.4 |

| AMIC | 13 | 23 | 39 | 27.7 | ||||

| Control Group | 6 | 33 | 41 | 25.2 | ||||

| Astur et al. 2018 65 | Rev Bras Orthop | Prospective | 12 | AMIC | 7 | 14 | 37 | |

| Bartlett et al. 2005 | J Bone Joint Surg | Prospective, Randomized | 12 | Control Group | 44 | 41 | 34 | |

| mACI | 47 | 33 | ||||||

| Basad et al. 2010 27 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Prospective, Randomized | 24 | mACI | 40 | 38 | 33 | 25.3 |

| Control Group | 20 | 15 | 38 | 27.3 | ||||

| Basad et al. 2015 15 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 25 | 37 | 32 | 24.0 |

| Becher et al. 2017 54 | J Orthop Surg Res | Prospective, Randomized | 36 | mACI | 25 | 32 | 33 | 24.9 |

| mACI | 25 | 16 | 34 | 25.6 | ||||

| mACI | 25 | 40 | 34 | 25.1 | ||||

| Behrens et al. 2006 25 | Knee | Prospective | 35 | mACI | 38 | 50 | 35 | |

| Brittberg et al. 2018 66 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective, Randomized | 60 | mACI | 65 | 38 | 35 | |

| Control Group | 63 | 33 | 34 | |||||

| Chung et al. 2014 67 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Prospective | 24 | Control Group | 12 | 83 | 44 | |

| AMIC | 24 | 42 | 47 | |||||

| Cvetanovich et al. 2017 68 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 24 | Control Group | 12 | 22 | 17 | 22.8 |

| mACI | 11 | 22 | 17 | 22.8 | ||||

| mACI | 14 | 22 | 17 | 22.8 | ||||

| De Girolamo et al. 2019 47 | J Clin Med | Prospective, Randomized | 100 | AMIC | 12 | 38 | 30 | |

| AMIC | 12 | 50 | 30 | |||||

| Ebert et al. 2011 11 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 44 | 48 | 39 | 25.5 |

| Ebert et al. 2012 16 | Arthroscopy | Prospective | 24 | mACI | 20 | 50 | 34 | 26.6 |

| Ebert et al. 2015 69 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 24 | mACI | 10 | 20 | 39 | 25.8 |

| mACI | 13 | 07 | 36 | 25.6 | ||||

| mACI | 9 | 66 | 38 | 25.1 | ||||

| mACI | 15 | 53 | 37 | 25.3 | ||||

| Ebert et al. 2017 70 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 31 | 51 | 35 | 26 |

| Efe et al. 2011 71 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 24 | mACI | 15 | 60 | 26 | |

| Enea et al. 2013 72 | Knee | Retrospective | 22 | AMIC | 9 | 45 | 48 | |

| Enea et al. 2015 73 | Knee | Retrospective | 29 | AMIC | 9 | 44 | 43 | |

| Ferruzzi et al. 2008 74 | J Bone Joint Surg | Prospective | 60 | Control Group | 48 | 38 | 32 | |

| mACI | 50 | 28 | 31 | |||||

| Gille et al. 2013 75 | Arch Orthop Trauma Surg | Prospective | 24 | AMIC | 57 | 33 | 37 | |

| Gobbi et al. 2009 76 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 34 | 32 | 31 | |

| Gudas et al. 2018 77 | J Orthop Surg | Retrospective | 54 | AMIC | 15 | 33 | 31 | |

| Hoburg et al. 2019 33 | Orthop J Sports Med | Prospective | 63 | mACI | 29 | 48 | 16 | 21.3 |

| 48 | mACI | 42 | 29 | 27 | 24.1 | |||

| Kon el al. 2011 61 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 61 | Control Group | 22 | 32 | 46 | 24.7 |

| 58 | mACI | 39 | 35 | 45 | 25.6 | |||

| Lahner et al. 2018 78 | Biomed Res Int | Prospective | 15 | AMIC | 9 | 48 | 29.3 | |

| Lopez-Alcorocho et al. 2018 79 | Cartilage | Prospective | 24 | mACI | 50 | 30 | 35 | |

| Macmull et al. 2011 80 | Int Orthop | Prospective | 66 | Control Group | 24 | 29 | 16 | |

| mACI | 7 | |||||||

| Macmull et al. 2012 81 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 45 | Control Group | 25 | 80 | 35 | |

| 35 | mACI | 23 | 61 | 35 | ||||

| Marlovits et al. 2012 82 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 24 | 12 | 35 | |

| Meyerkort et al. 2014 83 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 23 | 42 | ||

| Migliorini et al. 2021 84 | LIFE | Prospective | 43.7 | AMIC | 52 | 35 | 30 | 27.1 |

| 39.5 | Control Group | 31 | 32 | 31 | 26.5 | |||

| Migliorini et al. 2021 85 | LIFE | Prospective | 45.1 | AMIC | 27 | 48 | 36 | 26.9 |

| 49.1 | Control Group | 11 | 55 | 31 | 25.1 | |||

| Nawaz et al. 2014 32 | J Bone Joint Surg | Retrospective | 74 | Control Group | 827 | 40 | 34 | |

| mACI | ||||||||

| Nejadnik et al. 2010 31 | Am J Sports Med | Retrospective | 24 | mACI | 36 | 50 | 43 | |

| Control Group | 36 | 44 | 44 | |||||

| Niemeyer et al. 2008 30 | Arch Orthop Trauma Surg | Retrospective | 38 | Control Group | 95 | 34 | 25.1 | |

| mACI | ||||||||

| Niemeyer et al. 2016 86 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective, Randomized | 12 | mACI | 25 | 33 | 33 | 24.9 |

| mACI | 25 | 16 | 34 | 25.6 | ||||

| mACI | 25 | 40 | 34 | 25.1 | ||||

| Niemeyer et al. 2019 87 | Orthop J Sports Med | Prospective, Randomized | 24 | mACI | 52 | 36 | 36 | 25.7 |

| Control Group | 50 | 44 | 37 | 25.8 | ||||

| Saris et al. 2014 88 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective, Randomized | 24 | mACI | 72 | 37 | 35 | 26.2 |

| Control Group | 72 | 33 | 26.4 | |||||

| Schagemann et al. 2018 89 | Arch Orthop Trauma Surg | Retrospective | 24 | AMIC | 20 | 35 | 38 | 27.0 |

| AMIC | 30 | 43 | 34 | 23.9 | ||||

| Schiavone Panni et al. 2018 90 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Retrospective | 84 | AMIC | 21 | |||

| Schneider et al. 2011 91 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective | 30 | mACI | 116 | 42 | 33 | 24.5 |

| Schüttler et al. 2019 92 | Arch Orthop Trauma Surg | Prospective | 60 | mACI | 23 | 34 | 27.8 | |

| Siebold et al. 2018 93 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Prospective | 35 | mACI | 30 | 36 | 36 | 23.8 |

| Steinwachs et al. 2019 94 | Knee | Retrospective | 6 | AMIC | 93 | 28 | 42 | |

| Volz et al. 2017 95 | Int Orthop | Prospective, Randomized | 60 | AMIC | 17 | 29 | 34 | 27.4 |

| AMIC | 17 | 11 | 39 | 27.6 | ||||

| Control Group | 13 | 23 | 40 | 25.0 | ||||

| Zeifang et al. 2010 96 | Am J Sports Med | Prospective, Randomized | 24 | mACI | 11 | 45 | 29 | |

| Control Group | 10 | 00 | 30 |

Good comparability was found between the two groups at baseline (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the two cohorts at baseline (n.s.: not significant)

| Endpoint | AMIC (n = 373) | mACI (n = 1237) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (months) | 37.8 ± 29.9 | 39.8 ± 17.2 | n.s. |

| Women | 34% (125 of 373) | 37% (455 of 1237) | n.s. |

| Mean age | 28.2 ± 6.0 | 33.5 ± 6.5 | n.s. |

| Mean BMI | 26.1 ± 1.6 | 25.9 ± 1.2 | n.s. |

| Right side | 33% (124 of 373) | 52% (643 of 1237) | n.s. |

| Defect size (cm2) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 1.0 | n.s. |

| VAS | 6.4 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | n.s. |

| Tegner | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.3 | n.s. |

| Lysholm | 54.1 ± 12.6 | 53.7 ± 10.7 | n.s. |

| IKDC | 47.0 ± 9.1 | 40.2 ± 8.3 | n.s. |

Outcomes of interest

The AMIC group demonstrated greater values of IKDC (MD 7.7; P = 0.03) and Lysholm (MD 16.1; P = 0.02) scores. Similarity was found concerning the VAS (P = 0.5) and Tegner (P = 0.2) scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of Tegner and IKDC scores (n.s.: not significant)

| Endpoint | AMIC | mACI | MD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 0.07 | n.s. |

| Tegner | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 0.3 | n.s. |

| Lysholm | 81.9 ± 7.1 | 65.7 ± 28.2 | 16.1 | 0.02 |

| IKDC | 79.2 ± 10.4 | 71.5 ± 6.3 | 7.7 | 0.03 |

Complications

The AMIC group demonstrated lower rate of failures (OR 0.2; P = 0.04). Similarity was found concerning the rate of hypertrophy (P = 0.05), knee arthroplasty (P = 0.4) and revision surgery (P = 0.07) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of complications (n.s.: not significant)

| Complications | AMIC | mACI | OR | 95% CI | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| events | obs | rate | events | obs | rate | ||||

| Hypertrophy | 0 | 96 | 0 | 29 | 381 | 7.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 to 1.0 | 0.05 |

| Failure | 2 | 114 | 1.8 | 41 | 562 | 7.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 to 0.9 | 0.04 |

| Knee Arthroplasty | 2 | 126 | 1.6 | 2 | 64 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 to 3.6 | n.s. |

| Revision Surgery | 7 | 117 | 6.0 | 39 | 328 | 11.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 to 1.0 | 0.07 |

Discussion

According to the main findings of the present systematic review, AMIC performed better than mACI for chondral defects of the knee at ~40 months follow-up. The rate of complications was noticeably lower in the AMIC group. While the Tegner and VAS scores were similar, the mean difference of the Lysholm and IKDC scales exceeded the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) in favour of the AMIC group.21,24

mACI has been largely performed in patients with focal chondral defects of the knee.25,26 For the mACI procedure, an arthroscopy of the knee is performed first to assess cartilage status, identify the chondral defect and harvest chondrocytes from a non-weightbearing zone of the distal femur.27–29 Autologous chondrocytes are subsequently extracted and cultivated, and expanded in vitro for ~3 weeks, over a membrane that acts as medium for cell proliferation.30,31 In a second-step surgery, the defect is debrided and the membrane is secured into the defect.32,33 The current literature presents several clinical trials reporting the surgical outcomes of mACI. However, there are still controversies. The optimal surgical approach, whether arthrotomy, mini-arthrotomy or arthroscopy, has not been clarified. Additionally, there are several different membranes used for expansion (resorbable cell-free or cell-based, synthetic), and the most appropriate type of fixation (suture or fibrin glue) is still unclear.34–39

Recently, AMIC has gained increasing interest.36,40–43 Differently from mACI, which uses laboratory expanded autologous chondrocytes, AMIC is a single session procedure which exploits the regenerative potential of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs).14,44 After defect debridement and curettage, microfractures are performed.45,46 A membrane is then placed into the defect. BM-MSCs from the subchondral layer migrate into the membrane and regenerate the hyaline cartilage layer.12,47,48 Similar to mACI, AMIC can be performed through arthrotomy, mini-arthrotomy or arthroscopy.49,50 However, AMIC is more cost-effective, since it requires only one surgical step, avoiding in vitro cell expansion. Moreover, along with the avoidance of chondrocyte harvesting, AMIC should lead to less morbidity and faster recovery. These features make AMIC attractive to both surgeons and patients. We were unable to identify clinical studies which directly compare AMIC versus mACI for chondral defects of the knee: this is the single most important limitation of the available literature. Future studies should establish the most appropriate strategy for knee chondral defects. We hypothesize that the AMIC procedure will promote faster recovery and result in higher patient satisfaction.

We point out that all statistical analyses were performed regardless of the surgical approach. Indeed, authors performed the procedures using arthrotomy, mini-arthrotomy or arthroscopy. The mACI cohort included a larger number of studies and related procedures compared with the AMIC group. This discrepancy may generate biased results and influence the rate of uncommon complications related to poorer outcome. Given the lack of quantitative data, the average return to daily activities and/or sport participation were not investigated. All the membranes considered in the present investigation were cell-free and bioresorbable (collagenic or hyaluronic): this study did not consider cell-based or more innovative synthetic scaffolds.51–59 Moreover, the typology of membrane fixation (fibrin glue, suture, both methods or no fixation) was not considered as separate. Given the lack of relevant data, it was not possible to overcome these limitations. Many authors did not differentiate between primary and revision settings, and several studies included patients who received combined surgical procedures. Two studies60,61 performed membrane-assisted autologous chondrocyte transplantation (mACT). In mACT procedures, chondrocytes are harvested, cultivated and expanded into a membrane in the same fashion of mACI. The chondrocyte-loaded membrane is then carefully implanted into the defect using custom-made instruments in a full-arthroscopic fashion.62,63 Given these similarities, we analysed mACT and mACI as a single entity. The lack of detailed information did not allow us to analyse the aetiology of chondral defects as separate data sets. These limitations suggest cautious interpretation of the conclusions of this study.

Conclusion

AMIC may provide better outcomes than mACI for chondral defects of the knee. Further studies are needed to validate these results in a clinical setting.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

No external source of funding was used.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Kreuz PC, Steinwachs MR, Erggelet C, et al. Results after microfracture of full-thickness chondral defects in different compartments in the knee. Osteoarthr Cartil 2006;14:1119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scillia AJ, Aune KT, Andrachuk JS, et al. Return to play after chondroplasty of the knee in National Football League athletes. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:663–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dávila Castrodad IM, Mease SJ, Werheim E, et al. Arthroscopic chondral defect repair with extracellular matrix scaffold and bone marrow aspirate concentrate. Arthrosc Tech 2020;9:e1241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atala A, Irvine DJ, Moses M, Shaunak S. Wound healing versus regeneration: role of the tissue environment in regenerative medicine. MRS Bull 2010;35:597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buckwalter JA. Articular cartilage injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;402:21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robinson PG, Williamson T, Murray IR, et al. Sporting participation following the operative management of chondral defects of the knee at mid-term follow up: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Exp Orthop 2020;7:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Baroncini A, et al. Allograft versus autograft osteochondral transplant for chondral defects of the talus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2021;036354652110373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hinckel BB, Gomoll AH. Autologous chondrocytes and next-generation matrix-based autologous chondrocyte implantation. Clin Sports Med 2017;36:525–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Eschweiler J, et al. Reliability of the MOCART score: a systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol 2021;22:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carey JL, Remmers AE, Flanigan DC. Use of MACI (autologous cultured chondrocytes on porcine collagen membrane) in the United States: preliminary experience. Orthop J Sports Med 2020;8:232596712094181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ebert JR, Robertson WB, Woodhouse J, et al. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging-based outcomes to 5 years after matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation to address articular cartilage defects in the knee. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Migliorini F, Berton A, Salvatore G, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation and mesenchymal stem cells for the treatments of chondral defects of the knee- a systematic review. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2020;15:547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosa D, Balato G, Ciaramella G, et al. Long-term clinical results and MRI changes after autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee of young and active middle aged patients. J Orthop Traumatol 2016;17:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Migliorini F, Eschweiler J, Schenker H, et al. Surgical management of focal chondral defects of the knee: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Basad E, Wissing FR, Fehrenbach P, et al. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI) in the knee: clinical outcomes and challenges. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:3729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ebert JR, Fallon M, Ackland TR, et al. Arthroscopic matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation: 2-year outcomes. Art Ther 2012;28:952–64 e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Behrens P. Matrixgekoppelte Mikrofrakturierung. Art Ther 2005;18:193–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bark S, Piontek T, Behrens P, et al. Enhanced microfracture techniques in cartilage knee surgery: fact or fiction? World J Orthop 2014;5:444–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Howick J CI, Glasziou P, Greenhalgh T, Heneghan Carl, Liberati A, Moschetti I, Phillips B, Thornton H, Goddard O, Hodgkinson M. The 2011 Oxford CEBM levels of evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available athttps://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=56532011

- 21. Briggs KK, Lysholm J, Tegner Y, et al. The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm score and Tegner activity scale for anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee: 25 years later. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higgins LD, Taylor MK, Park D, et al. International knee documentation C. reliability and validity of the international knee documentation committee (IKDC) subjective knee form. Joint Bone Spine 2007;74:594–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lysholm J, Gillquist J. Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med 1982;10:150–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, et al. Measures of knee function: international knee documentation committee (IKDC) subjective knee evaluation form, knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score physical function short form (KOOS-PS), knee outcome survey activities of daily living scale (KOS-ADL), Lysholm knee scoring scale, Oxford knee score (OKS), western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC), activity rating scale (ARS), and Tegner activity score (TAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:S208–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Behrens P, Bitter T, Kurz B, Russlies M. Matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation/implantation (MACT/MACI)--5-year follow-up. Knee 2006;13:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bartlett W, Skinner JA, Gooding CR, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation versus matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation for osteochondral defects of the knee: a prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Basad E, Ishaque B, Bachmann G, et al. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus microfracture in the treatment of cartilage defects of the knee: a 2-year randomised study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akgun I, Unlu MC, Erdal OA, et al. Matrix-induced autologous mesenchymal stem cell implantation versus matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation in the treatment of chondral defects of the knee: a 2-year randomized study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015;135:251–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korner D, Gonser CE, Dobele S, et al. Matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation with autologous bone grafting of osteochondral lesions of the talus in adolescents: patient-reported outcomes with a median follow-up of 6 years. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Niemeyer P, Steinwachs M, Erggelet C, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for the treatment of retropatellar cartilage defects: clinical results referred to defect localisation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008;128:1223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nejadnik H, Hui JH, Feng Choong EP, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells versus autologous chondrocyte implantation: an observational cohort study. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nawaz SZ, Bentley G, Briggs TW, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee: mid-term to long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:824–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoburg A, Loer I, Korsmeier K, et al. Matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation is an effective treatment at midterm follow-up in adolescents and young adults. Orthop J Sports Med 2019;7:232596711984107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kwan H, Chisari E, Khan WS. Cell-free scaffolds as a monotherapy for focal chondral knee defects. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bekkers JE, Tsuchida AI, Malda J, et al. Quality of scaffold fixation in a human cadaver knee model. Osteoarthr Cartil 2010;18:266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Benthien JP, Behrens P. Autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC): combining microfracturing and a collagen I/III matrix for articular cartilage resurfacing. Cartilage 2010;1:65–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hindle P, Hall AC, Biant LC. Viability of chondrocytes seeded onto a collagen I/III membrane for matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation. J Orthop Res 2014;32:1495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gigante A, Bevilacqua C, Ricevuto A, et al. Membrane-seeded autologous chondrocytes: cell viability and characterization at surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cappuccio JA, Blanchette CD, Sulchek TA, et al. Cell-free co-expression of functional membrane proteins and apolipoprotein, forming soluble nanolipoprotein particles. Mol Cell Proteomics 2008;7:2246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gao L, Orth P, Cucchiarini M, Madry H. Autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. Am J Sports Med 2019;47:222–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gotze C, Nieder C, Felder H, Migliorini F. AMIC for focal osteochondral defect of the Talar shoulder. Life (Basel) 2020;10:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Migliorini F, Eschweiler J, Maffulli N, et al. Autologous matrix induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) compared to microfractures for chondral defects of the Talar shoulder: a five-year follow-up prospective cohort study. Life (Basel) 2021;11:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gotze C, Nieder C, Felder H, et al. AMIC for traumatic focal osteochondral defect of the talar shoulder: a 5 years follow-up prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dewan AK, Gibson MA, Elisseeff JH, Trice ME. Evolution of autologous chondrocyte repair and comparison to other cartilage repair techniques. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gille J, Schuseil E, Wimmer J, et al. Mid-term results of autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis for treatment of focal cartilage defects in the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:1456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kusano T, Jakob RP, Gautier E, et al. Treatment of isolated chondral and osteochondral defects in the knee by autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20:2109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Girolamo L, Schonhuber H, Vigano M, et al. Autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) and AMIC enhanced by autologous concentrated bone marrow aspirate (BMAC) allow for stable clinical and functional improvements at up to 9 years follow-up: results from a randomized controlled study. J Clin Med 2019;8:392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Baroncini A, et al. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis for chondral defects of the talus: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 2021;138:144–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Schenker H, et al. Surgical Management of Focal Chondral Defects of the talus: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2021;036354652110296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Migliorini F, Eschweiler J, Spiezia F, et al. Arthroscopy versus mini-arthrotomy approach for matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee: a systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol 2021;22:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Migliorini F, Eschweiler J, Goetze C, et al. Membrane scaffolds for matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 2021;140:50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vilchez F, Lara J, Alvarez-Lozano E, et al. Knee chondral lesions treated with autologous chondrocyte transplantation in a tridimensional matrix: clinical evaluation at 1-year follow-up. J Orthop Traumatol 2009;10:173–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bozkurt M, Asik MD, Gursoy S, et al. Autologous stem cell-derived chondrocyte implantation with bio-targeted microspheres for the treatment of osteochondral defects. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Becher C, Laute V, Fickert S, et al. Safety of three different product doses in autologous chondrocyte implantation: results of a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. J Orthop Surg Res 2017;12:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ishihara K, Nakayama K, Akieda S, et al. Simultaneous regeneration of full-thickness cartilage and subchondral bone defects in vivo using a three-dimensional scaffold-free autologous construct derived from high-density bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Surg Res 2014;9:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Klangjorhor J, Nimkingratana P, Settakorn J, et al. Hyaluronan production and chondrogenic properties of primary human chondrocyte on gelatin based hematostatic spongostan scaffold. J Orthop Surg Res 2012;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jamil K, Chua KH, Joudi S, et al. Development of a cartilage composite utilizing porous tantalum, fibrin, and rabbit chondrocytes for treatment of cartilage defect. J Orthop Surg Res 2015;10:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tomaszewski R, Wiktor L, Gap A. Enhancement of cartilage repair through the addition of growth plate chondrocytes in an immature skeleton animal model. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Delgado-Enciso I, Paz-Garcia J, Valtierra-Alvarez J, et al. A phase I-II controlled randomized trial using a promising novel cell-free formulation for articular cartilage regeneration as treatment of severe osteoarthritis of the knee. Eur J Med Res 2018;23:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kon E, Gobbi A, Filardo G, et al. Arthroscopic second-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation compared with microfracture for chondral lesions of the knee: prospective nonrandomized study at 5 years. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kon E, Filardo G, Condello V, et al. Second-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation: results in patients older than 40 years. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1668–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Filardo G, Kon E, Andriolo L, et al. Clinical profiling in cartilage regeneration: prognostic factors for midterm results of matrix-assisted autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino A, et al. Arthroscopic second-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation: a prospective 7-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:2153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Anders S, Volz M, Frick H, Gellissen J. A randomized, controlled trial comparing autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC(R)) to microfracture: analysis of 1- and 2-year follow-up data of 2 Centers. Open Orthop J 2013;7:133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Astur DC, Lopes JC, Santos MA, et al. Surgical treatment of chondral knee defects using a collagen membrane - autologus matrix-induced chondrogenesis. Rev Bras Ortop 2018;53:733–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Brittberg M, Recker D, Ilgenfritz J, et al. Matrix-applied characterized autologous cultured chondrocytes versus microfracture: five-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Am J Sports Med 2018;46:1343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chung JY, Lee DH, Kim TH, et al. Cartilage extra-cellular matrix biomembrane for the enhancement of microfractured defects. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:1249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cvetanovich GL, Riboh JC, Tilton AK, Cole BJ. Autologous chondrocyte implantation improves knee-specific functional outcomes and health-related quality of life in adolescent patients. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ebert JR, Fallon M, Smith A, et al. Prospective clinical and radiologic evaluation of patellofemoral matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:1362–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ebert JR, Fallon M, Wood DJ, Janes GC. A prospective clinical and radiological evaluation at 5 years after arthroscopic matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Efe T, Theisen C, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, et al. Cell-free collagen type I matrix for repair of cartilage defects-clinical and magnetic resonance imaging results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20:1915–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Enea D, Cecconi S, Calcagno S, et al. Single-stage cartilage repair in the knee with microfracture covered with a resorbable polymer-based matrix and autologous bone marrow concentrate. Knee 2013;20:562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Enea D, Cecconi S, Calcagno S, et al. One-step cartilage repair in the knee: collagen-covered microfracture and autologous bone marrow concentrate. A pilot study. Knee 2015;22:30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ferruzzi A, Buda R, Faldini C, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee joint: open compared with arthroscopic technique. Comparison at a minimum follow-up of five years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gille J, Behrens P, Volpi P, et al. Outcome of autologous matrix induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) in cartilage knee surgery: data of the AMIC registry. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gobbi A, Kon E, Berruto M, et al. Patellofemoral full-thickness chondral defects treated with second-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation: results at 5 years' follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1083–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gudas R, Maciulaitis J, Staskunas M, Smailys A. Clinical outcome after treatment of single and multiple cartilage defects by autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27:230949901985101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lahner M, Ull C, Hagen M, et al. Cartilage surgery in overweight patients: clinical and MRI results after the autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis procedure. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lopez-Alcorocho JM, Aboli L, Guillen-Vicente I, et al. Cartilage defect treatment using high-density autologous chondrocyte implantation: two-year follow-up. Cartilage 2018;9:363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Macmull S, Parratt MT, Bentley G, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the adolescent knee. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1723–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Macmull S, Jaiswal PK, Bentley G, et al. The role of autologous chondrocyte implantation in the treatment of symptomatic chondromalacia patellae. Int Orthop 2012;36:1371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Marlovits S, Aldrian S, Wondrasch B, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes 5 years after matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation in patients with symptomatic, traumatic chondral defects. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Meyerkort D, Ebert JR, Ackland TR, et al. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI) for chondral defects in the patellofemoral joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:2522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Migliorini F, Eschweiler J, Maffulli N, et al. Autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) and microfractures for focal chondral defects of the knee: a medium-term comparative study. Life (Basel) 2021;11:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Migliorini F, Eschweiler J, Maffulli N, et al. Management of Patellar Chondral Defects with autologous matrix induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) compared to microfractures: a four years follow-up clinical trial. Life (Basel) 2021;11:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Niemeyer P, Laute V, John T, et al. The effect of cell dose on the early magnetic resonance morphological outcomes of autologous cell implantation for articular cartilage defects in the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med 2016;44:2005–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Niemeyer P, Laute V, Zinser W, et al. A prospective, randomized, open-label, Multicenter, phase III noninferiority trial to compare the clinical efficacy of matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation with spheroid technology versus arthroscopic microfracture for cartilage defects of the knee. Orthop J Sports Med 2019;7:232596711985444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Saris D, Price A, Widuchowski W, et al. Matrix-applied characterized autologous cultured chondrocytes versus microfracture: two-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:1384–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Schagemann J, Behrens P, Paech A, et al. Mid-term outcome of arthroscopic AMIC for the treatment of articular cartilage defects in the knee joint is equivalent to mini-open procedures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018;138:819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Schiavone Panni A, Del Regno C, Mazzitelli G, et al. Good clinical results with autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (Amic) technique in large knee chondral defects. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018;26:1130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Schneider U, Rackwitz L, Andereya S, et al. A prospective multicenter study on the outcome of type I collagen hydrogel-based autologous chondrocyte implantation (CaReS) for the repair of articular cartilage defects in the knee. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:2558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Schuttler KF, Gotschenberg A, Klasan A, et al. Cell-free cartilage repair in large defects of the knee: increased failure rate 5 years after implantation of a collagen type I scaffold. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2019;139:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Siebold R, Suezer F, Schmitt B, et al. Good clinical and MRI outcome after arthroscopic autologous chondrocyte implantation for cartilage repair in the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018;26:831–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Steinwachs M, Cavalcanti N, Mauuva Venkatesh Reddy S, et al. Arthroscopic and open treatment of cartilage lesions with BST-CARGEL scaffold and microfracture: a cohort study of consecutive patients. Knee 2019;26:174–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Volz M, Schaumburger J, Frick H, et al. A randomized controlled trial demonstrating sustained benefit of autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis over microfracture at five years. Int Orthop 2017;41:797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zeifang F, Oberle D, Nierhoff C, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation using the original periosteum-cover technique versus matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:924–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.