The meta-analytic by Mertens et al. (1) interprets nudges as a generally effective technique for increasing desirable decision-making, with an overall pooled effect size of d = 0.43. This research also reports large systematic variations (meta-analytic heterogeneity) in effects, primarily attributed to moderators such as the domain, as well as asymmetrically distributed effects, interpreted as moderate publication bias.

Apart from publication bias, non-normality and high heterogeneity may be problematic for the representativeness of meta-analytic means (2). Here, we reanalyze the corrected data made available by Mertens et al. (1), finding evidence that nudges have more limited than general effectiveness. We show that effects are clearly left-truncated, likely due to substantial publication bias, consistent with another reanalysis (3). We also find that most of the pooled effects as reported in Mertens et al. (1) are overestimated and hence unrepresentative.

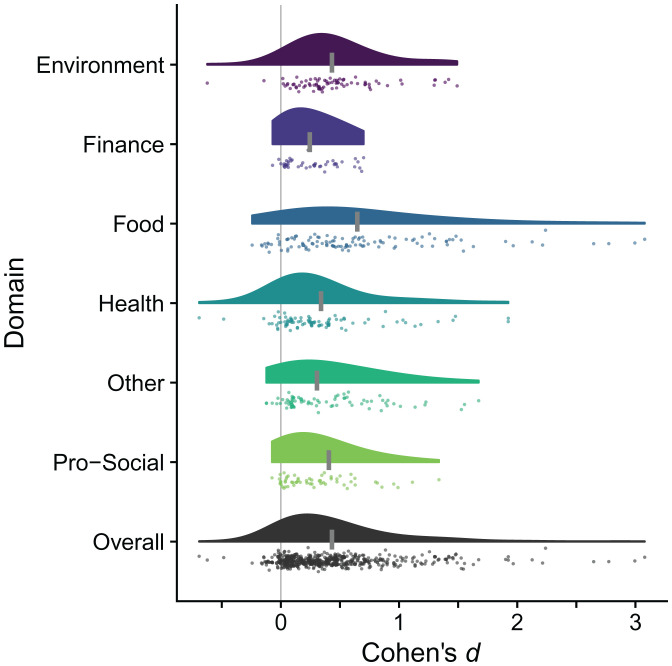

First, we visualize the distributions of effects, by domain, using raincloud plots (4); see Fig. 1. Four domains (finance, food, other, and prosocial) show a concerning pattern of sharply left-truncated tails at or slightly below zero. The two remaining domains only have a handful of effects slightly below zero. A plausible mechanism for this left “cliff” is suppression of unfavorable results (5). Most domains also exhibit long right tails—a limited number of effects with large and very large magnitudes. This pattern of left truncation and long right tails strongly indicates that publication bias is greater than moderate.

Fig. 1.

Raincloud plots of individual effects by domain and all effects. The rain is the reported effects from papers, jittered vertically, and the cloud is the smoothed distribution of effects. The short, wide, vertical gray lines on each cloud depict the corresponding meta-analytic mean. The single tall thin vertical gray line is an effect size of zero.

Second, we evaluate non-normality and the representativeness of pooled effects by domain (Table 1). Normality was assessed using Egger’s regression test for asymmetry (6). Representativeness was tested by quantifying the estimated proportion of effects below meaningful thresholds (7), here, the meta-analytic means. A perfectly representative (meta-analytic) mean would have 50% of values below it.

Table 1.

Normality of effects and representativeness of meta-analytic effects

| Egger’s | Meta-analytic | Proportion of | |

|---|---|---|---|

| regression | mean | effects | |

| Domain | test (P value) | (Cohen’s d) | below (%) |

| Environment | <0.001 | 0.43 | 55.26 |

| Finance | 0.01 | 0.24 | 55.56 |

| Food | 0.01 | 0.65 | 60.36 |

| Health | <0.001 | 0.34 | 72.62 |

| Other | <0.001 | 0.31 | 49.32 |

| Prosocial | <0.001 | 0.41 | 67.39* |

| Overall | <0.001 | 0.43 | 62.64 |

*For prosocial, the proportion of effects below is underestimated because 12 effects with a Cohen’s |d| < 0.04 out of 58 effects were removed due to estimation problems.

All domains exhibited asymmetry, and all but one (other) had some overestimation in pooled effects, that is, a greater than expected proportion of effects below their meta-analytic mean. Despite left truncation of effects, nearly two-thirds of all effects were still below the overall meta-analytic mean.

Funnel plots can often be difficult to interpret (8), and, typically, all effects are plotted together; thus, the severity and nature of the non-normality in effects, especially by domain, may not be apparent in Mertens et al. (1). Here, we evaluate effects by domain; therefore, our results cannot be solely attributed to the heterogeneity and non-normality potentially caused by combining domains.

The end goal of nudges and related behavioral interventions is increasing desirable decision-making. Achieving this requires identifying factors associated with positive impacts, but also factors that have minimal and even negative effects on decisions (9, 10). Publication bias impedes understanding for variations in nudge effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Schultheis for editing a previous version of this work. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory or the US government. The US government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data Availability

Data and code are available at https://osf.io/jydb7/ (11) and https://codeocean.com/capsule/3133766/tree/v1 (12).

References

- 1.Mertens S., Herberz M., Hahnel U. J. J., Brosch T., The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2107346118 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine T. R., Weber R., Unresolved heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Combined construct invalidity, confounding, and other challenges to understanding mean effect sizes. Hum. Commun. Res. 46, 343–354 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szaszi B., et al., No reason to expect large and consistent effects of nudge interventions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2200732119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen M., Poggiali D., Whitaker K., Marshall T. R., Kievit R. A., Raincloud plots: A multi-platform tool for robust data visualization. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 63 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Formann A. K., Estimating the proportion of studies missing for meta-analysis due to publication bias. Contemp. Clin. Trials 29, 732–739 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egger M., Smith G. Davey, Schneider M., Minder C., Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathur M. B., VanderWeele T. J., New metrics for meta-analyses of heterogeneous effects. Stat. Med. 38, 1336–1342 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terrin N., Schmid C. H., Lau J., In an empirical evaluation of the funnel plot, researchers could not visually identify publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 58, 894–901 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunstein C. R., Nudges that fail. Behav. Public Policy 1, 4–25 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawley J. K., Mares A. L., “Human performance challenges for the future force: Lessons from patriot after the second gulf war” in Designing Soldier Systems: Current Issues in Human Factors, Savage-Knepshield P., Allender L., Martin J. W., Lockett J., Eds. (CRC, 2018), pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakdash J., Marusich L., Data for “Left-truncated effects and overestimated meta-analytic means.” Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/jydb7/. Deposited 14 February 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bakdash J., Marusich L., Data and code for “Left-truncated effects and overestimated meta-analytic means.” Code Ocean. https://codeocean.com/capsule/3133766/tree/v1. Deposited 20 April 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and code are available at https://osf.io/jydb7/ (11) and https://codeocean.com/capsule/3133766/tree/v1 (12).