Abstract

Background

The current study examined the interrelations among social support, family quality of life (FQOL), and family cohesion and adaptability in Chinese families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Methods

A sample of 163 caregivers of children with ASD in China were surveyed with the Social Support Rating Scale, Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale, and Chinese version of Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale II, respectively. We used structural equation modeling to examine the mediating role of family cohesion and adaptability on the relationship between social support and FQOL.

Results

The results indicated that social support had a positive impact on FQOL and that family cohesion and adaptability completely mediated the relationship between social support and caregivers’ satisfaction on FQOL.

Conclusions

Facilitating family cohesion and adaptability by providing social support may be beneficial to help families of children with ASD improve their FQOL. The findings identified the need for developing targeted interventions for this population.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, caregivers, social support, family quality of life, family cohesion, family adaptability

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and to sustain reciprocal social interaction and social communication, and by a range of restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behavior and interests (World Health Organization 2018). The prevalence of ASD has increased significantly in recent years. About 1 in 54 children has been identified with ASD according to the newest estimates from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in America. The prevalence of ASD in China has been found was at around 1% (Sun et al. 2019). According to latest National Population Sample Survey by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (2017), the child population aged 0–17 in China was 271 million, which means that there are more than two million children and adolescents with ASD in China. Family caregivers play an prominent role in supporting children with ASD, which may be stressful for caregivers and can further negatively influence the entire family quality of life (FQOL) (Hsiao et al. 2017, Wang et al. 2018, Zeng et al. 2020). FQOL is a construct that reflects family well-being (Garrido et al. 2020), which means conditions when the family’s needs are met, family members enjoy their life together as a family, and family members have the opportunity to pursue and achieve outcomes that are important to their happiness and fulfillment (Park et al. 2003). Caregivers of children with ASD were found to have a poorer FQOL both in the West (Vasilopoulou and Nisbet 2016) and in China (Li 2016a, Luo 2014, Ma 2014, Wang et al. 2018). Chinese and Western caregivers experience very different social and cultural contexts, as Chinese caregiving is characterized by a lack of formal support, and cultural concerns as loss of face and strong affiliated stigma (Chiu et al. 2012). It is therefore critical to focus on Chinese caregivers in order to determine specific interventions to improve their satisfaction on FQOL.

Background of the study

Previous study reported that parental health-related quality of life was negatively influenced by their child’s ASDs (Kuhlthau et al. 2014), especially the severity of the child’s ASD syndrome since it affects children’s rehabilitation outcomes and aggravates caregivers’ burden (Ji et al. 2014). So, family members raising children with ASD usually have to seek support from within or outside the family while having difficulty coping with stress (Ni and Su 2012). Social support is thus one of many factors that predict caregivers’ life satisfaction (Lu et al. 2015). It refers to the perceived or actual assistance that an individual receives from another person or institution and can be in the form of either physical and instrumental assistance or emotional and psychological support (Boyd 2002). Ekas et al. (2010) found each source of social support (partner, other family members, and friends) was associated with increased life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Kuhlthau et al. (2014) reported the perceived quality of life was influenced by the presence or absence of effective support systems for their child with ASD. Pozo et al. (2014) also found parents of children with ASD who perceived more social support were more likely to report a better FQOL. Studies in Chinese populations have also shown the positive correlation of social support and FQOL (Guan et al. 2015, Ji et al. 2014, Li 2016b, Liu 2013, Lu et al. 2015).

As the link between social support and FQOL has been drawn in literature, it is particularly important to explore the mechanism so as to identify how social support influences FQOL. Children with ASD significantly affect parental and family functioning (Rao and Beidel 2009). Olson et al. (1979) conceptualized the Circumplex Model in the 1970s and proposed a balanced level of both cohesion and adaptability was the most functional to family development. Family cohesion refers to the emotional bonding members have with one another and the degree of individual autonomy a person experiences in the family system, whereas family adaptability is defined as the ability of a marital/family system to change its power structure, role relationships, and relationship rules in response to situational and developmental stress (Olson et al. 1979). Family cohesion and adaptability both reflect the interaction of a family and are regarded as important determinants of family ‘health’. Family cohesion and adaptability may have a mediation effect between social support and FQOL. Research has found that social support contributes to perceived family cohesion and adaptability, and thus enhances a higher level of satisfaction on FQOL. For instance, previous studies reported social support positively correlated with family cohesion and adaptability (Ji et al. 2013, Lin et al. 2011, Zhou et al. 2015), and greater family sense of coherence and greater coping predicted higher level of maternal FQOL among caregivers raising a child with ASD (Ji et al. 2014, McStay et al. 2014, Pozo et al. 2014). Considering the role of family environment when studying family adjustment is important (Ekas et al. 2016). The role of family cohesion and adaptability in Chinese caregivers of children with ASD should be emphasized. On the one hand, culture predicts family functioning (Lin et al. 2011) and the collectivism culture in China may promote family bonding. On the other hand, disability is highly stigmatized in collectivist cultures (Singh et al. 2017), and the prevalent and strong affiliate stigma experienced by Chinese caregivers of children with autism (Zhou et al. 2018) might make it difficult for them to adapt to the stresses of caring for the child.

Purpose of the study

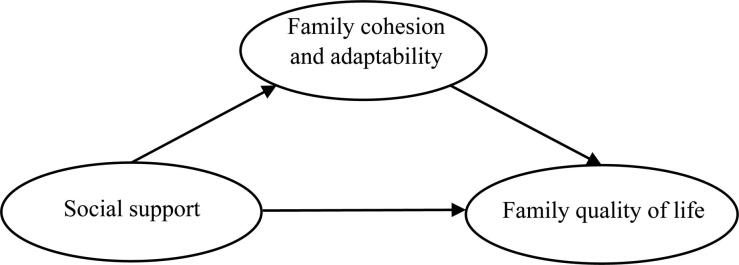

It has been established that FQOL, social support, and family cohesion and adaptability are all important factors for the well-being of caregivers raising children with ASD. The correlations of social support and FQOL, social support and family cohesion and adaptability, and family cohesion and adaptability and FQOL have been identified in existing studies. However, to our knowledge, there is no study to examine the interrelations among social support, FQOL, and family cohesion and adaptability in caregivers of children with ASD, especially a study concerning families in China. A better understanding of the interrelations among the three variables might help inform interventions targeted to supporting families of children with ASD. In view of this, the current study examined the interrelations among these factors in a sample of Chinese caregivers of children with ASD. We presented the conceptual model illustrated in Figure 1 which proposed that: (1) a direct relationship between social support and FQOL existed and (2) family cohesion and adaptability acted as a mediator on this relationship. Consequently, the purposes of this observational study were: (1) to examine the relationship between social support and FQOL in caregivers raising children with ASD in China and (2) to determine the mediating effect of family cohesion and adaptability on this relationship.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized model.

Methods

Procedure

The caregiver in the current study was defined as the key person living with and caring for the child with ASD. We recruited participants through convenience sampling in Sichuan province, southwest China. The inclusion criteria were: (1) one parent or caregiver of, (2) a child diagnosed with ASD, (3) under 18 years old. We contacted the parents or caregivers of children with ASD through special education schools and introduced the study and explained the anonymity and confidentiality of the data. We tried to involve all potential participants. And 190 participants agreed to participate in the study. Each of the 190 families received the questionnaire and one parent or caregiver was asked to complete it on behalf of the family. And a total of 163 families completed and returned the questionnaires. Ethics approval was obtained from the funding body. There was expected no risk from the participation in the study that was voluntary.

Participants

Participants in the present study included 163 caregivers raising a child with ASD in Sichuan province. More than half of the respondents were mothers (56.40%), others were fathers (21.50%), grandparents or other legal guardians (22.10%). The majority of them were from urban areas (70.60%), the remaining caregivers were from rural areas (29.40%). Almost all were married or living with a partner (85.80%), and a small percentage of caregivers were divorced, separated, or widowed (14.20%). More than half of the caregivers were unemployed (53.70%), the rest had full-time or part-time job (46.30%). The educational levels of caregivers varied among primary school or below (29.40%), junior school (19.00%), senior high school (16.60%), junior college (16.00%), bachelor’s degree or above (19.00%). The monthly income levels varied from less than 2000 RMB (about 282 USD) (27.60%) to more than 10,000 RMB (about 1410 USD) (6.70%), with the largest group of caregivers (38.70%) reporting their income were between 2000 RMB and 4000 RMB (about 564 USD). More than half of the families had only one child (57.40%), and 42.60% had more than one child. In terms of the children with ASD, they ranged in age 2–17 (M = 9.77, SD = 3.97), and were almost twice more males (66.70%) than females (33.30%). Almost half of them had (46.90%) severe level of autism, 36.40% had moderate level, and 16.70% had mild level.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

All of the measures used in this study were self-administered written questionnaires. A brief questionnaire was used to obtain demographic information, including marital status, educational level, employment status, family residence, household income, number of children, age, gender, and levels of severity of the child with ASD.

Social support

Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), developed by Xiao (1994) based on Chinese environmental and cultural background, was used to measure caregivers’ perceptions of social support. This 10-item scale includes three dimensions: subjective support (4 items), objective support (3 items), and the utilization of support (3 items). The participants responded to their levels of agreement with items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much) except for items 6 and 7, for which they selected one source of social support (which counted as one score). The total score is the sum of the scores for each item, ranging from 12 to 66, and is defined as low (≦44) and high (>44) (Dai et al. 2016, Xiao et al. 2017). The scale has been proved to be with good reliability and validity (Liu 2013). The value of Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study was 0.703, showing an acceptable reliability coefficient.

Family quality of life

Chinese version of Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale (BCFQOL) was used. This 25-item scale includes five subdomains (family interaction, parenting, emotional well-being, physical/material well-being, and disability-related support). For each item, caregivers rated their satisfaction on this 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). Responses were summed to form a total FQOL score, ranging from 0 to 125, which was then averaged into a single mean score. A higher score indicates a greater satisfaction on FQOL. The Chinese version of BCFQOL has been proved with high internal consistency (Li 2016a). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.927, indicating a good level of internal consistency.

Family cohesion and adaptability

Chinese version of Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale II (FACES II-CV) was used to evaluate family cohesion and adaptability. It was developed by Olson et al. in 1982, and imported into China by Phillips et al. in 1991. It’s a 30-item self-report scale. The original scale includes the participant’s perception of actual and idea family conditions. In this study, the respondents only need to reflect the actual conditions on the 5-point Likert scale with the poles from ‘almost never’ to ‘almost always’. The ranges of scores for cohesion and adaptability are 28–92 and 8–64, respectively (Deng et al. 2011). Higher scores equate to higher family cohesion and adaptability. The Chinese version has been verified with high retest reliability, internal consistency and convergence validity (Phillips et al. 1998). The value of Cronbach’s alpha for family cohesion was 0.826 and family adaptability was 0.845 in this study, reflecting a good level of reliability consistency.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 18.0 and AMOS version 17.0. Descriptive statistics were used to obtain the means and standard deviations of the study variables. One-way ANOVAs and independent-sample t-tests were conducted to examine the differences in demographic variables related to socioeconomic status, including educational level, employment status, and household income. Pearson correlations were calculated to examine the relationships among social support, family cohesion and adaptability, and FQOL. A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was conducted to test mediation effect. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The criteria for the model indices including: χ2/df (the ratio of chi-square statistic to its degrees of freedom) < 5, NFI (normed fit index) > 0.9, CFI (comparative fit index) > 0.9, and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) < 0.08 (Hsiao et al. 2017).

Results

As common method bias (CMB) may occur in this study due to the use of three scales to measure the same participant, Harman’s Single-Factor Test was used to address the concern about CMB in this study. The results showed that there were 16 factors with eigenvalue greater than 1, and the variation explained by the first factor was 23.62%, less than the critical standard of 40% (Podsakoff et al. 2003). It suggests that CMB did not pose a serious threat to interpreting our present findings.

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations of the study variables and their correlations. Our sample perceived low level of social support (M = 34.85, SD = 8.80) and moderate satisfactory FQOL (M = 3.40, SD = 0.62). When compared with the Chinese norm of family cohesion and adaptability (M = 63.90, SD = 8.00; M = 50.90, SD = 6.20, respectively) (Phillips et al. 1998), caregivers of children with ASD scored significantly higher on family cohesion (t = 2.05, p < 0.05), and significantly lower on adaptability (t = −7.92, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for social support, family cohesion, family adaptability, and family quality of life

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

34.85 | 8.80 | – | |||

|

65.56 | 10.19 | 0.467*** | – | ||

|

45.40 | 8.73 | 0.423*** | 0.758*** | – | |

|

3.40 | 0.62 | 0.424*** | 0.552*** | 0.482*** | – |

Note. M = mean, SD = standard deviation, ***p < 0.001.

Demographic differences on each variable were examined. The results suggested that caregivers at different educational levels showed significant differences in social support (F = 5.16, p < 0.01), FQOL (F = 4.42, p < 0.01), family cohesion (F = 5.83, p < 0.001), and family adaptability (F = 7.51, p < 0.001). Employed caregivers reported higher social support (t = 4.92, p < 0.001), FQOL (t = 4.36, p < 0.001), family cohesion (t = 4.56, p < 0.001), and family adaptability (t = 4.36, p < 0.001) compared with unemployed ones. Caregivers with different household income levels also differed significantly in their perceptions of social support (F = 4.58, p < 0.01), FQOL (F = 3.56, p < 0.01), family cohesion (F = 3.06, p < 0.5), and family adaptability (F = 3.15, p < 0.05).

As reported in Table 1, a statistically significant, positive association was found between social support and FQOL (r = 0.424, p < 0.001). It means that families with higher level of social support were more satisfied with their FQOL. We also found that family cohesion and family adaptability were positively correlated with social support (r = 0.467, p < 0.001 and r = 0.423, p < 0.001, respectively) and FQOL (r = 0.552, p < 0.001 and r = 0.482, p < 0.001, respectively). This indicated that higher levels of family cohesion and adaptability were observed when the caregivers reported greater social support, and caregivers who were identified as higher cohesion and better adaptability were more likely to perceive higher satisfaction with their FQOL.

Model fit testing

The model (Figure 1) was assessed regarding how well the collected data fitted with the hypothesized model. The fit indices of the SEM analyses revealed an excellent fit with the data (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of model fit

| Fit index | Value |

|---|---|

| χ2/df | 1.672 |

| CFI | 0.971 |

| NFI | 0.933 |

| RMSEA | 0.067 |

Mediation analysis

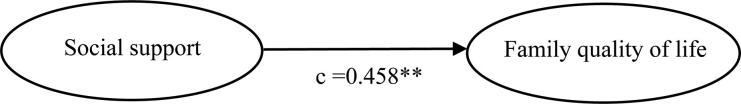

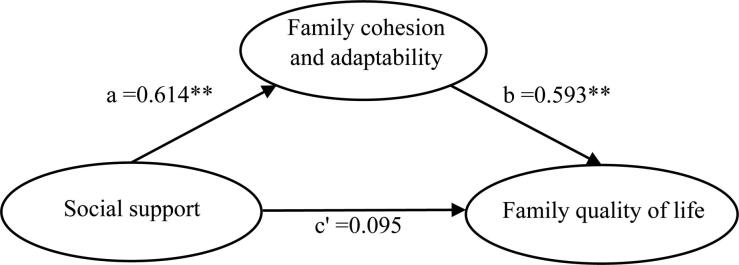

The existed significant bivariate correlations among social support, FQOL, and family cohesion and adaptability provided a certain prerequisite for the subsequent mediator analysis. A SEM approach was conducted to examine whether the mediation effect occurs. As illustrated in Figure 2, the total effect was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.01). And Figure 3 presents the results of the hypothesized model test. It showed that the indirect paths were reported to be statistically significant (p < 0.01), while no direct effect between social support and FQOL (p = 0.452 > 0.05). This means that family cohesion and adaptability completely mediated the relationship between social support and FQOL in caregivers of children with ASD. Confidence intervals of the total standardized indirect effect of social support on FQOL (95% CI: 0.244, 0.573) based on 2000 bootstrap sample did not include zero, further suggesting significant complete mediation. The ratio of the indirect to total effect for this relationship was 0.793 (namely 0.364/0.459), indicating that approximately 79.3% of the total effect of social support on FQOL was accounted for by the mediation.

Figure 2.

The total effect between social support and family quality of life (Path c). Standardized path coefficient was presented. Note. **p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

The mediation model. Path c′ indicates the direct effect, and Paths a and b indicate the indirect effects. Standardized path coefficients were presented. Note. **p < 0.01.

Discussion

The present study aimed to elucidate the interrelations among social support, FQOL, and family cohesion and adaptability in Chinese families of children with ASD. We replicated the results of previous research in other countries by showing that caregivers of children with ASD experienced low level of social support (Ekas et al. 2016, Singh et al. 2017, Xue et al. 2014), increased family cohesion (Iacolino et al. 2016, Javadian 2011, Rodrigue et al. 1990), less adaptability (Gau et al. 2012, Higgins et al. 2005, Xue et al. 2014), and moderate satisfaction on FQOL (Meral et al. 2013, Schlebusch et al. 2017). The differences found in study variables in terms of the background characteristics of the caregivers, like educational level, employment status, and household income, may illustrate that one’s socioeconomic status acts as a significant determinant of the positive perceptions. Better socioeconomic status is related to better financial and social resources to acquire, and associated with increased awareness of health-care needs and a greater motivation for improvement of psychological health (Chiu et al. 2012).

The positive relationship found between social support and FQOL suggested that families who obtained more social support were more satisfied with their family’s quality of life. Reciprocally, when families perceived a lower level of satisfaction with their FQOL, they perceived limited social support. This finding is consistent with prior researches that have found a positive relationship between social support and FQOL in families raising a child with ASD (e.g. Pozo et al. 2014). The result is also supported by Chinese previous findings with other disability groups (Guan et al. 2015, Li 2016b, Liu 2013). In a systematic review, Vasilopoulou and Nisbet (2016) highlighted social support as one of the significant factors associated with quality of life for parents of children with ASD, which also supports our finding. Due to a greater level of caregiver’s burden, a greater likelihood to quit a job because of child-care problems, less participation in activities/events, and less involvement in community services (Lee et al. 2008), families of children with ASD usually experience greater stress (Plumb 2011, Rao and Beidel 2009, Zeng et al. 2020) and thus are more likely to report a lower level of satisfaction with their FQOL (Hsiao et al. 2017, Zeng et al. 2020). The provision of social support could empower families by giving them hope and leading them to positively appraise the future (Ekas et al. 2010), in turn, contributing to reduce depression, negative affect, and parental stress (Benson 2012, Ekas et al. 2010, Plumb 2011, Sawyer et al. 2010), then be beneficial in promoting their life satisfaction or FQOL (Lu et al. 2015, Pozo et al. 2014). However, our sample perceived limited social support. Because they often experience social exclusion and isolation (Marsack and Samuel 2017) and frequently employ escape-avoidance coping strategies (Pisula and Kossakowska 2010, Pozo et al. 2014). As found by Ekas et al. (2016) that mothers of children with ASD were turning more to family members in place of friends. They are more likely to seek support from their inner circle of the social network, and not from outside of the family (Singh et al. 2017). The findings of the current study contribute to researches on families raising children with ASD in China. It provides supporting evidence that social support is an important factor contributing to a family’s quality of life, thus justifying the need for focusing on providing effective social support that might enhance the well-being of the family.

Family cohesion and adaptability are important constructs to understand coping in families of children with ASD. We found family cohesion and adaptability acted as a significant mediator explaining the path from social support to FQOL. The finding is consistent, in part, with the findings of Ekas et al. (2016), in which family cohesion was found to have a mediating effect on the relationship between friend support and depressive symptoms for Hispanic mothers of children with ASD. The complete mediation finding in our study suggested that more social support was related to higher level of family cohesion and adaptability, which was associated with a higher overall satisfaction of FQOL. It provides an explanation of how the social support affects FQOL and suggests that a focus on family cohesion and adaptability is warranted. Previous studies reported greater social support predicted better family cohesion and adaptability in parents of children with ASD (e.g. Altiere and Kluge 2009, Ekas et al. 2016), and found the association between family cohesion and adaptability and quality of life in caregivers of individuals with other diseases (e.g. Han et al. 2006, Rodríguez-Sánchez et al. 2011, Tramonti et al. 2015). The findings of this study extended previous research examining the three important aspects for families of children with ASD. This finding is particularly important for families raising children with ASD because it lends evidence to consider the role of family cohesion and adaptability while developing coping strategies to promote FQOL for this group. Existing researches show the importance of family cohesion and adaptability for both caregivers and their children. For example, family cohesion and adaptability were reported to be significantly associated with caregivers’ perceived well-being (Boyraz and Sayger 2011), affiliate stigma, and depressive symptoms (Zhou et al. 2018). And poor family functioning was found to predict poorer levels of functioning in the child with ASD (Sikora et al. 2013). Thus, a cohesive family environment may not only increase caregivers’ well-being and help obtain the skills to restructure family characteristics to adjust to the impact of challenges but also foster children’s ability to cope with stressors (Boyraz and Sayger 2011). The increased family cohesion and less adaptability found in the current study support that caregivers of children with ASD demonstrate resilience and positive outcomes (McStay et al. 2014), but lack positive coping strategies (Lin et al. 2011). Studies reported a majority of mothers felt their child with ASD enriched their lives (King et al. 2009) and had a positive effect on their marital relationship (Luo 2014). Both higher and lower family cohesion and adaptability may be associated with dysfunctional family interaction (Gau et al. 2012, Higgins et al. 2005). The role of social support in promoting family cohesion and adaptive outcomes has been examined (Ekas et al. 2016, Lin et al. 2011). Hence, social support can be implemented to facilitate the family’s cohesion and adaptability, which would be beneficial for their FQOL.

Implications for practice

This study identified several important implications for practitioners that may be used to enhance FQOL for families raising a child with ASD. It informs practitioners who work with these families a better understanding that facilitating family cohesion and adaptability by providing social support might be an alternative way to help this population improve their FQOL. We need interventions that help foster family cohesion and adaptability by helping families to strengthen the bonds among family members, and to enhance parental adjustment and coping skills. The provision of mental appease, financial help, disability-related services, and respite care might be useful steps toward this direction. For example, the Parent-to-Parent model could be utilized in this population, in which parents of children with disabilities were matched with parent supporters (i.e. individuals who have experience caring for children with disabilities) (Ekas et al. 2010). As the severity of disorder had a negative relation to FQOL (Pozo et al. 2014), plus Chinese general population only have limited knowledge about ASD (Ji et al. 2014), practitioners should pay more attention to provide families with clear and consistent information about the characteristics of ASD and develop resources to manage family demands and to empower families to acquire feelings of control. Due to the crisis in the long-term caring, ensuring caregivers have the time and resources to be able to participate in social and other health-promoting activities could be beneficial in promoting their FQOL, so providing respite care, experienced child-care at home, as well as support in planning outdoor activities with or without the child might be useful (Vasilopoulou and Nisbet 2016). It should be noted that Chinese caregivers of children with a disability may be reluctant to seek support from outside the family since they are characterized by strong affiliated stigma due to the socio-political context (Chiu et al. 2012). Helping caregivers raise awareness of ASD and reduce any associated stigma (Lu et al. 2015) and increase the use of available social support could therefore contribute to their FQOL. As this study underscores the importance of developing family-centered interventions, those views could be used to design intervention programs to benefit families of children with ASD.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

Although the current study may provide a useful framework for developing family-centered interventions tailored to meet the needs of families of children with ASD, several limitations of the current study must be taken into account. One of these limitations is the small sample size and the sample consisted of mainly Sichuan province of China, leading to the limited generalizability of the results. Future research may consider conducting a study that includes a large sample from diverse areas, especially families from economically constrained environments. It would help in understanding how these relationships change across different contexts. Also, the present study recruited participants from special education schools and future research may consider expanding the participants to families whose children with ASD don’t attend schools or any other institutions. Besides, this study surveyed the families at only a single time point. Future research is needed to further examine the process longitudinally to make stronger inferences about the relations among social support, family cohesion and adaptability, and FQOL for families of children with ASD. Also, exploring the relations among these three important aspects (i.e. social support, family cohesion and adaptability, FQOL) in a qualitative study may identify additional mechanisms involved in these families.

Conclusion

Experiences of social support and family cohesion and adaptability are important constructs in how families experience their FQOL. This study demonstrates that the relations between social support and FQOL can be explained by perceived family cohesion and adaptability. The findings of this study provide considerable and valuable information, which is an important step toward targeted family-centered interventions to strengthen FQOL in families raising a child with ASD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the families who donate their time participating in this study and all the teachers in the special education schools who helped to contact with the participants.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Sichuan Applied Psychology Research Center (CSXL-172014), Sichuan Special Education Development Research Center (SCTJ-2019-03), and Leshan Normal University (S16001).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Altiere, M. J. and Kluge, S. V.. 2009. Family functioning and coping behaviors in parents of children with autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, P. R. 2012. Network characteristics, perceived social support, and psychological adjustment in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 2597–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, B. A. 2002. Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Boyraz, G. and Sayger, T. V.. 2011. Psychological well-being among fathers of children with and without disabilities: The role of family cohesion, adaptability, and paternal self-efficacy. American Journal of Men's Health, 5, 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, M. Y. L., Yang, X., Wong, F. H. T., Li, J. H. and Li, J.. 2012. Caregiving of children with intellectual disabilities in China–an examination of affiliate stigma and the cultural thesis. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 12, 1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W., Chen, L., Tan, H., Wang, J., Lai, Z., Kaminga, A. C., Li, Y. and Liu, A.. 2016. Association between social support and recovery from post-traumatic stress disorder after flood: A 13–14 year follow-up study in Hunan, China. BMC Public Health, 16, 194–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y., Yang, L. and Yin, Y.. 2011. Family adaptability and cohesion among rural attempted suicides. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 27, 184–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ekas, N. V., Ghilain, C., Pruitt, M., Celimli, S., Gutierrez, A. and Alessandri, M.. 2016. The role of family cohesion in the psychological adjustment of non-Hispanic White and Hispanic mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 21, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ekas, N. V., Lickenbrock, D. M. and Whitman, T. L.. 2010. Optimism, social support, and well-being in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1274–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, D., Carballo, G. and Garcia-Retamero, R.. 2020. Siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders: Social support and family quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 29, 1193–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau, S. S., Chou, M., Chiang, H., Lee, J., Wong, C., Chou, W. and Wu, Y.. 2012. Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W., Yan, T. and Deng, M.. 2015. The characteristics of parenting stress of parents of children with disabilities and their effects on their quality of life: The mediating role of social support. Psychological Development and Education, 4, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K. S., Khim, S. Y., Lee, S. J., Park, E. S., Park, Y. J., Kim, J. H., Lee, K. M., Kang, H. C. and Yoon, J. W.. 2006. Family functioning and quality of life of the family caregiver in cancer patients. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi, 36, 983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, D., Bailey, S. and Pearce, J.. 2005. Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 9, 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, Y. J., Higgins, K., Pierce, T., Whitby, P. J. S. and Tandy, R. D.. 2017. Parental stress, family quality of life, and family-teacher partnerships: Families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 70, 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacolino, C., Pellerone, M., Pace, U., Ramaci, T. and Castorina, V.. 2016. Family functioning and disability: A study on Italian parents of disabled children. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 39–52.doi: 10.15405/epsbs.2016.05.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javadian, R. 2011. A comparative study of adaptability and cohesion in families with and without a disabled child. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2625–2630. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B., Chen, S., Yi, R., Wang, Q. and Tang, S.. 2013. Study on social support, coping style, and family functioning in parents of children with autism. Guangdong Medical Journal, 10, 1594–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B., Zhao, I., Turner, C., Sun, M., Yi, R. and Tang, S.. 2014. Predictors of health-related quality of life in Chinese caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders: A cross-sectional study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28, 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, G., Baxter, D., Rosenbaum, P., Zwaigenbaum, L. and Bates, A.. 2009. Belief systems of families of children with autism spectrum disorders or Down syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlthau, K., Payakachat, N., Delahaye, J., Hurson, J., Pyne, J. M., Kovacs, E. and Tilford, J. M.. 2014. Quality of life for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. C., Harrington, R. A., Louie, B. B. and Newschaffer, C. J.. 2008. Children with autism: Quality of life and parental concerns. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1147–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. 2016. a. Research on family quality of life of families with the autistic children in Shanghai. Masters’ dissertation. East China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. 2016. b. Study on the relation of social support, psychological stress, and life satisfaction for the main caregivers of autistic children. Master’s dissertation. Southwest University. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L. Y., Orsmond, G. I., Coster, W. J. and Cohn, E. S.. 2011. Families of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders in Taiwan: The role of social support and coping in family adaptation and maternal well-being. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. 2013. Study in the relationship between the social support, coping style, mental stress and life satisfaction of the disabled children’s parents. Master’s dissertation. South-Central University for Nationalities. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M., Yang, G., Skora, E., Wang, G., Cai, Y., Sun, Q. and Li, W.. 2015. Self-esteem, social support, and life satisfaction in Chinese parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 17, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L. 2014. The study of the life quality of families with autistic children in Chengdu. Master’s dissertation. Sichuan Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S. 2014. Quality of life of autistic children’s parents and study on its relevant influence factors. Master’s dissertation. Shandong University. [Google Scholar]

- Marsack, C. N. and Samuel, P. S.. 2017. Mediating effects of social support on quality of life for parents of adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2378–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McStay, R. L., Trembath, D. and Dissanayake, C.. 2014. Stress and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Parent gender and the double ABCX model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 3101–3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meral, B. F., Cavkaytar, A., Turnbull, A. P. and Wang, M.. 2013. Family quality of life of Turkish families who have children with intellectual disabilities and autism. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 38, 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China . 2017. UNICEF China, UNFPA China. Population status of children in China in 2015: Facts and figures. [online] Available at: <https://www.unicef.cn/en/reports/population-status-children-china-2015> [Accessed 10 February 2020].

- Ni, C. and Su, M.. 2012. “Ideal model” and construction of autism family supporting web: Empirical analysis of Shenzhen 120 autism families. Social Work, 9, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D. H., Sprenkle, D. H. and Russell, C. S.. 1979. Circumplex model of marital and family systems: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Family Process, 18, 3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., Hoffman, L., Marquis, J., Turnbull, A. P., Poston, D., Mannan, H., Wang, M. and Nelson, L. L.. 2003. Toward assessing family outcomes of service delivery: Validation of a family quality of life survey. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47, 367–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. R., West, C. L., Shen, Q. and Zheng, Y.. 1998. Comparison of schizophrenic patients’ families and normal families in China, using Chinese versions of FACES-II and the family environment scales. Family Process, 37, 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisula, E. and Kossakowska, Z.. 2010. Sense of coherence and coping with stress among mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1485–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumb, J. C. 2011. The impact of social support and family resilience on parental stress in families with a child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. PhD. University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. and Podsakoff, N. P.. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo, P., Sarriá, E. and Brioso, A.. 2014. Family quality of life and psychological well‐being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A double ABCX model. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58, 442–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P. A. and Beidel, D. C.. 2009. The impact of children with high-functioning autism on parental stress, sibling adjustment, and family functioning. Behavior Modification, 33, 437–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue, J. R., Morgan, S. B. and Geffken, G.. 1990. Families of autistic children: Psychological functioning of mothers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, E., Pérez-Peñaranda, A., Losada-Baltar, A., Pérez-Arechaederra, D., Gómez-Marcos, M. Á., Patino-Alonso, M. C. and García-Ortiz, L.. 2011. Relationships between quality of life and family function in caregiver. BMC Family Practice, 12, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, M. G., Bittman, M., La Greca, A. M., Crettenden, A., Harchak, T. F. and Martin, J.. 2010. Time demands of caring for children with autism: What are the implications for maternal mental health? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlebusch, L., Dada, S. and Samuels, A.. 2017. Family quality of life of South African families raising children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 1966–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, D. M., Moran, E., Orlich, F., Hall, T. A., Kovacs, E., Delahaye, J., Clemons, T. and Kuhlthau, K.. 2013. The relationship between family functioning and behavior problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P., Ghosh, S. and Nandi, S.. 2017. Subjective burden and depression in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder in India: Moderating effect of social support. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3097–3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X., Allison, C., Wei, L., Matthews, F. E., Auyeung, B., Wu, Y. Y., Griffiths, S., Zhang, J., Baron-Cohen, S. and Brayne, C.. 2019. Autism prevalence in China is comparable to Western prevalence. Molecular Autism, 10, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramonti, F., Bonfiglio, L., Di Bernardo, C., Ulivi, C., Virgillito, A., Rossi, B. and Carboncini, M. C.. 2015. Family functioning in severe brain injuries: Correlations with caregivers’ burden, perceived social support and quality of life. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20, 933–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulou, E. and Nisbet, J.. 2016. The quality of life of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Xiao, L., Chen, R., Chen, C., Xun, G., Lu, X., Shen, Y., Wu, R., Xia, K., Zhao, J. and Ou, J.. 2018. Social impairment of children with autism spectrum disorder affects parental quality of life in different ways. Psychiatry Research, 266, 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2018. International Classification of Diseases (11th Revision). [online] Available at: <https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/437815624> [Accessed 4 December 2019].

- Xiao, J., Huang, B., Shen, H., Liu, X., Zhang, J., Zhong, Y., Wu, C., Hua, T. and Gao, Y.. 2017. Association between social support and health-related quality of life among Chinese seafarers: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 12, e0187275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S. 1994. Theoretical basis and research application of Social Support Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J., Ooh, J. and Magiati, I.. 2014. Family functioning in Asian families raising children with autism spectrum disorders: The role of capabilities and positive meanings. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58, 406–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S., Hu, X., Zhao, H. and Stone-MacDonald, A. K.. 2020. Examining the relationships of parental stress, family support and family quality of life: A structural equation modeling approach. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 96, 103523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C., Wu, H., Zhu, D., Xie, J., Zhou, Z. and Li, Y.. 2015. Study on the correlation between family intimacy and adaptability of children with cerebral palsy and social support. Maternal and Child Health Care of China, 14, 2184–2187. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T., Wang, Y. and Yi, C.. 2018. Affiliate stigma and depression in caregivers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in China: Effects of self-esteem, shame and family functioning. Psychiatry Research, 264, 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]