Abstract

Discovery research in rodent models of cognitive aging is instrumental for identifying mechanisms of behavioral decline in old age that can be therapeutically targeted. Clinically relevant behavioral paradigms, however, have not been widely employed in aged rats. The current study aimed to bridge this translational gap by testing cognition in a cross-species touch screen-based platform known as paired-associates learning (PAL) and then utilizing a trial-by-trial behavioral analysis approach. This study found age-related deficits in PAL task acquisition in male rats. Furthermore, trial-by-trail analyses and testing rats on a novel interference version of PAL suggested that age-related impairments were not due to differences in vulnerability to an irrelevant distractor, motivation, or to forgetting. Rather, impairment appeared to arise from vulnerability to accumulating, proactive interference, with aged animals performing worse than younger rats in later trial blocks within a single testing session. The detailed behavioral analysis employed in this study provides new insights into the etiology of age-associated cognitive deficits.

Keywords: cognitive aging, hippocampus, strategy, striatum, win-stay, lose-shift

1. INTRODUCTION

Clinically relevant behavioral paradigms in animal models of cognitive aging have great potential for increasing the translational efficacy of discovery research that identifies new therapeutic targets for enhancing cognitive function in older adults. While recent rodent studies have examined the link between cognition and distributed systems-level changes in advanced age that are related to networks defined in humans (Ash et al. 2016; Hernandez et al. 2016; Gardner et al. 2020; Colon-Perez et al. 2019), clinically minded assessments have yet to be broadly adopted in rat models of cognitive aging. Importantly, experiments in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease that parallel work in human patients with dementia (Beraldo et al. 2019; Romberg et al. 2011) suggest that there is utility in implementing cognitive assessments that build towards a cross-species consensus to close the translational gap between discovery and clinical science.

Nonverbal, touchscreen-based testing platforms have emerged as reliable and automated ways to test cognition across species (Kangas et al. 2017; Bussey et al. 2008, 2012; McCallister et al. 2013). Originally developed with extensive lesion data from nonhuman primates, the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) has been used clinically to test multiple neurocognitive domains including memory, attention, and executive functioning (Robbins & Sahakian, 1994). CANTAB has been widely validated and several tests in this assessment have been successfully reverse translated for use in rodents, including the Paired Associates Learning (PAL) Test (Barnett et al. 2016). PAL has been used in humans to detect deficits in visuo-spatial associative memory in advanced age and mild cognitive impairment related to Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Swainson et al. 2001; Blackwell et al. 2004; Robbins et al. 1998), but has not yet been employed in a rat model of advanced age.

Successful completion of the rodent PAL task requires associative learning to correctly pair a stimulus (flower, plane, spider) with its correct location on the touchscreen (left, center, right). This cognitive ability is known to require the hippocampus (HPC; Talpos et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2015; Langston, 2010; Yoon, 2012). Moreover, it also likely involves the perirhinal cortex (PER) for visual stimulus recognition, and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) for selective attention, executive control, and behavioral flexibility (Barker et al. 2007; Barker & Warburton, 2015; Jo & Lee, 2010a; Staresina & Davachi, 2008; Vilberg & Davachi, 2013; Gemperie et al. 2003; Bizon et al. 2012). Previous studies have investigated stimulus-location associative learning in large, three-dimensional mazes and reported age-related impairments in acquisition. This work has linked behavioral impairments in aged rats to altered activity patterns in the medial PFC (Hernandez et al. 2020a), PER (Hernandez et al. 2018a), and dorsal striatum (Colon-Perez et al. 2019). Whether age-related impairments in the acquisition of stimulus-location associations arise from age-related differences in strategy selection, memory abilities, or vulnerability to distraction has not been directly assessed, however. This lack of understanding regarding the origins of age-related changes in stimulus-location association is due to the low-throughput and manual nature of standard versions of these tasks, which render trial-by-trial analyses of ongoing performance difficult to implement. The higher throughput data collection and ease of trial-by-trial analyses enabled by the touchscreen-based PAL task permit a more granular analysis.

To assess PAL performance in young and aged rats, along with traditional performance measures of percent correct and trials to criterion, this study also used trial-by-trial analyses to elucidate behavioral tendencies that may point to underlying dysfunction in terms of three potential sources of behavioral variability: 1) the use of aberrant behavioral strategies, 2) memory impairments resulting in associations being forgotten between testing sessions, and 3) vulnerability to interference. These analyses included response-driven biases toward selecting a certain location or stimulus, outcome biases toward win-stay and lose-shift strategies, and within and between session changes in percent correct across trial blocks. Furthermore, we assessed interference vulnerability by creating a new variant of the PAL task in which an irrelevant distractor stimulus was included, referred to as interference (i)PAL. This study revealed age-related differences in acquisition of the PAL task. Detailed behavioral analysis of performance throughout cognitive testing was used to more richly inform task strategies and performance dynamics that will be crucial to future studies determining network level impairments in the PAL test of cognitive function.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects.

A total of 12 aged and 12 young male Fischer 344 x Brown Norway F1 hybrid rats (NIA colony) were used in this experiment. At the time of arrival from the NIA, young rodents were 4 months and aged were 24 months old. Two aged rats were excluded from this study due to health issues that prevented the completion of testing. Rats were single-housed in standard Plexiglas cages and maintained on a reversed 12-h light/dark schedule (lights off at 8:00 am). Upon arrival rats were given one week to habituate prior to food restriction and the initiation of behavioral shaping. All experiments took place during the dark phase, 5–7 days per week at approximately the same time every day. To encourage appetitive behavior in the touchscreen apparatus, rats were placed on restricted feeding in which ~20.5 g (1.9 kcal/g) moist chow was provided daily, and drinking water was provided ad libitum. Shaping began once rats reached approximately 85% of their baseline weights. Baseline weight was considered the weight at which an animal had an optimal body condition score of 3.0. Throughout the period of restricted feeding, rats were weighed daily, and body condition was assessed and recorded weekly to ensure a range of 2.5–3.5. The body condition score was assigned based on the presence of palpable fat deposits over the lumbar vertebrae and pelvic bones (Hickman & Swan, 2010; Ullman-Culleré & Foltz, 1999). Animals with a score under 2.5 were given additional food to promote weight gain. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Florida.

2.2. Apparatus.

Behavioral testing was conducted using standard Bussey-Saksida Rat Touch Screen Chambers purchased from Lafayette Instruments (21.6 × 17.8 × 12.7 cm) equipped with a touchscreen monitor (16 × 21.2 cm, screen resolution 1024 × 768), fan (providing ventilation and white noise), tone and click generator, house light (LED), magazine unit (with light and infrared beam to detect entries) and pump connected to bottle of liquid Ensure reward. The chambers have a trapezoidal shape, composed of three black plastic walls. The shape is intended to help guide the focus of the animal towards both the touchscreen and reward delivery area. A three-panel black mask is placed over the touchscreen monitor with rectangular panels cut out to allow the presentation of stimuli in a specific area and prevent accidental touches. A spring-loaded shelf was affixed to the front of the mask to allow rats to direct their attention to the response windows and rear up to make selections. Chambers were housed within a soundproof box to prevent outside noise from impacting behavior. Our system used custom software from Lafayette to present trial stimuli and control inputs/outputs: ABET II software for operant control and Whisker Standard Software.

2.3. Shaping.

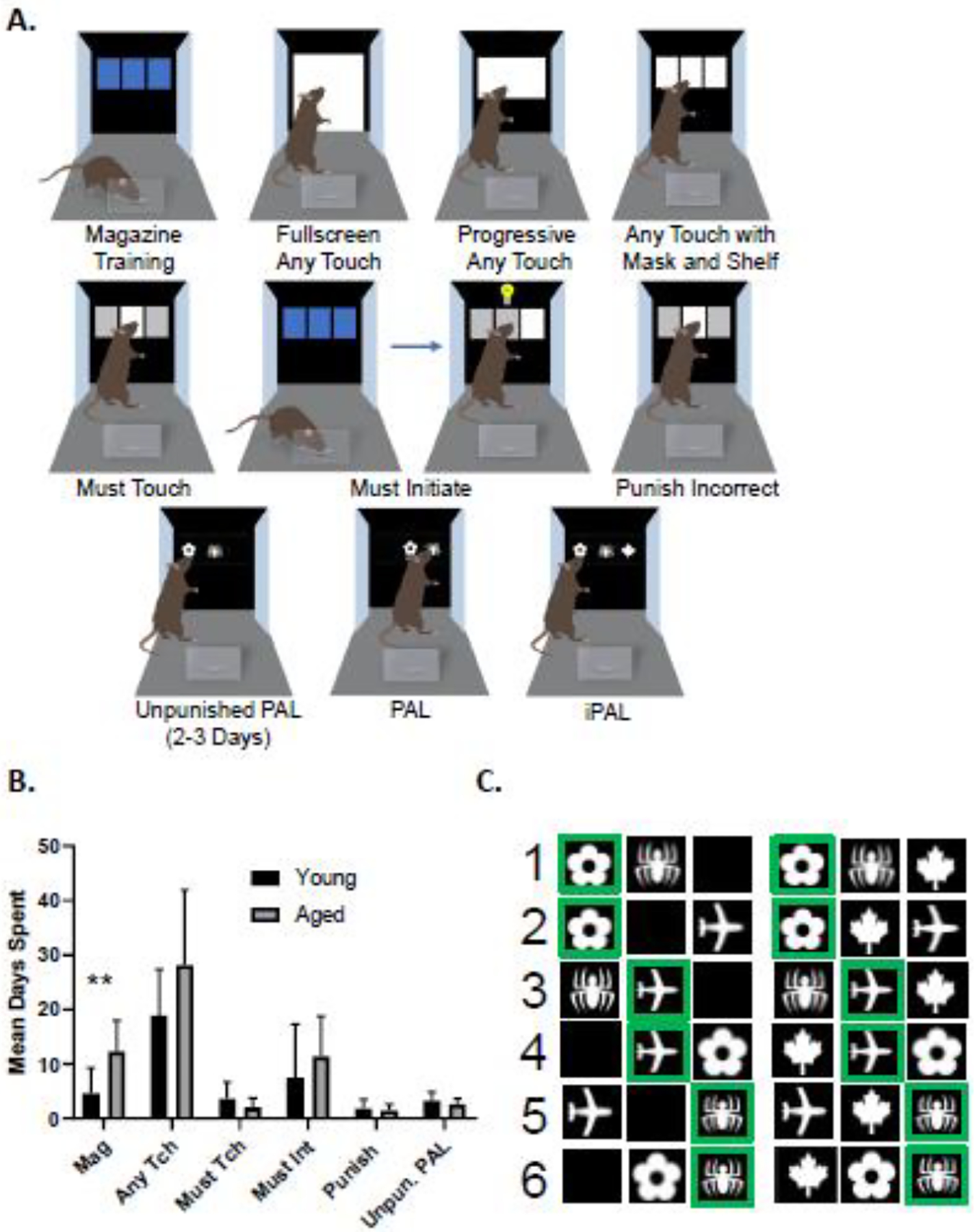

Rats were shaped to use the touch screens through five incremental training stages: Magazine, Any Touch, Must Touch, Must Initiate, and Punish Incorrect. Due to difficulties completing the Any Touch stage for the aged rats, a modified shaping paradigm was adapted that included three additional stages within the Any Touch training level (Fullscreen Any Touch, Progressive Any Touch, and standard Any Touch with mask and shelf introduced). A schematic of this training procedure is depicted in Figure 1A. Rats were first introduced to the touch screen chamber with Magazine training. This stage dispensed liquid Ensure reward when the rat nose poked the magazine opening. During this stage of training rats were not required to engage with the touchscreen. Rats were kept on magazine training until they could complete 100 trials in under 30 minutes.

Figure 1: Touchscreen Tasks & Shaping Procedure.

A) Timeline depicting the modified shaping protocol for the PAL task. B) Average number of days (y-axis) spent on each shaping procedure (x-axis) for young (black; n = 12) and aged (gray; n = 10) rats. Any Touch was measured as the sum of all three Any Touch stages. Aged rats took significantly longer on the first stage of shaping, magazine training (T(20) = 3.491, p = 0.0023), but not on any subsequent stage of shaping (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). Error bars are ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM) and ** indicates p < 0.005. C) Touchscreen stimuli for PAL (left) and iPAL (right) tasks. There are six possible trial types that are presented pseudo-randomly for a total of 90 trials in a session. Rewarded stimuli are shown with a green border. For each of the six trial types in PAL the blank panel is not responsive to touch and is therefore not a valid selection. In iPAL, a novel stimulus, the maple leaf, is in the blank panel. While the maple leaf is always incorrect, it can be selected unlike the blank panel in PAL.

The next step of shaping is Fullscreen Any Touch, which was used to introduce the relationship between engagement with the touchscreen and the liquid reward. During this stage of shaping the entirety screen was illuminated and the rat could touch any part to obtain reward. Rats were required to complete 100 trials of touching the screen with a nose or paw in one 45 min session to move on to the Progressive Any Touch step. Progressive Any Touch was used to gradually direct the rat’s attention to the upper portion of the screen where stimulus images would later be presented. The first 20 trials of a session in this stage illuminated the entire screen as previously done in any touch full screen. The next 20 trials only illuminated the upper ¾ of the screen, followed by the next 20 trials illuminating ½ the screen. This gradual approach to shifting their attention to the upper portion of the screen ensured that rats learned to attend to the relevant region of the screen for proper task performance.

After rats had reached criterion on Progressive Any Touch, they were moved on to standard Any Touch, which introduced a shelf and a three-panel stimulus mask. The shelf was placed to allow rats the opportunity to prop themselves up on their hind legs while touching the touchscreen with their nose. During this stage of training, a white square was presented in one of the three panels. To receive a liquid reward, the rat could nose poke either the blank panels or the panel with the white square. The screen remained active with the white square displayed until a response occurred. Once the response occurred, a tone sounded, and a reward was delivered, and the touchscreen was deactivated. After the reward was collected, the next trial began after a 10 second inter-trial interval (ITI). This stage of training was repeated until the rats could complete 80 or more trials in 45 minutes. The main distinction of the Any Touch stage of training from other subsequent stages is that the rat received a reward for engaging with any part of the touchscreen and not just the white square.

After completing Any Touch, the rats moved on to the Must Touch stage. Unlike the previous stage of shaping, Must Touch required the rat to select the white square presented on the screen to receive food reward. Touches to the blank panels were not rewarded in this stage of shaping. To prevent the development of a side bias, the target image was randomly assigned to one of three possible locations for each trial. This stage was continued until the rat could complete 80 or more trials in 45 minutes.

The next stage in shaping is Must Initiate. This stage required that the rat nose poke the feeder to initiate a new trial. This facilitates both inter-trial latency measurements as well as active attention to the task. Again, animals were required to complete 80 or more trials in 45 minutes to move on in the shaping procedure. The final stage of shaping is Punish Incorrect, which introduced a punishment for incorrect choices. During this stage if the rat did not select the white square being presented on the screen, the house light was turned on and a 10 second timeout period occurred before another trial could be initiated. Figure 1B shows the mean number of days that young and aged rats spent at each stage of shaping. Aged rats took significantly longer on the magazine training stage of shaping compared to the young group (T(20) = 3.491, p = 0.0023). This was likely due to the aged rats being at a higher body condition score initially and requiring more extensive weight loss than young animals to become appetitively motivated. There were no significant differences between age groups for the subsequent stages of shaping (p > 0.05 for all comparisons), which suggests that young and old rats acquired the procedural aspects of PAL testing at a similar rate.

2.4. Paired Associates Learning (PAL) task and the interference (i)PAL task.

After rats had completed all stages of the shaping protocol, they were moved on to the PAL task. The PAL task contained three possible stimuli (S1, S2, S3) and three possible locations on the screen (L1, L2, L3). Each of the three stimuli was assigned to a correct location that was unique to the stimuli. During a trial, two stimuli were presented at the same time. One stimulus was presented in the correct location and the other was in the incorrect location, and the third location was a blank panel. Thus, six trial types are possible: 1. S+=L1S1, S−=L2S3; 2. S+=L1S1, S−=L3S2; 3. S+=L2S2, S−=L1S3; 4. S+=L2S2, S−=L3S1; 5. S+=L3S3, S−=L1S2; 6. S+=L3S3, S-L2S1, which are depicted in Figure 1C. The trials were pseudo-randomly selected to ensure that no specific trial type was presented more than three consecutive times. During the first 2–3 days of PAL testing, subjects were tested on an unpunished version of PAL where only the correct selection would initiate a reward, but incorrect choices were not punished, and the stimuli remained on the screen until the correct choice was made. Once a criterion of two consecutive days of 90 trials or 180 trials total was reached, rats advanced to the standard PAL task in which incorrect trials were punished with illumination of the house light and a time out. Young and aged rats therefore received comparable numbers of unpunished acquisition trials and these days were not included in the analyses.

During the PAL task, rats were required to nose poke the object being presented in its correct location to receive a food reward. After a trial was completed, an inter-trial interval would begin, which lasted 10 seconds. If the rat selected the incorrect image or the blank panel, no food reward was delivered, and a timeout period occurred during which the house light turned on. Each PAL session lasted for a total of 45 minutes or upon completion of 90 trials. Rats were tested on the PAL task until they reached a criterion performance of 83.33% correct for two testing days. After rats established criterion on the PAL task, they participated in the novel interference (i)PAL task, which was designed to test the hypothesis that aged rats are more vulnerable to distracting stimuli. The iPAL task was a modification of PAL in which a novel image (a white maple leaf) was presented in the blank panel as a distractor. Selection of the novel stimulus did not elicit a reward and was therefore considered an incorrect choice. Figure 1C depicts the 6 possible iPAL trial types.

Previous PAL procedures have included correction trials such that when the subject makes an incorrect response, the next trial initiated will be the same stimuli and locations. There is typically no limit on the number of correction trials that can be given consecutively, but once the subject correctly responds the correction procedure ends (Horner et al. 2013). Because correction trials can counteract side and stimulus biases, which were two variables of interest in the current study, we elected to implement a version of PAL without correction trials. Additionally, since this study aimed to assess age differences in PAL acquisition, we were concerned that differences in the numbers of correction trials between age groups and a potential age effect in the ability to benefit from correction trials could confound the interpretation of potential age differences.

2.5. Analyses and Statistics.

Stimulus and Location Bias.

To assess whether rats used different performance strategies, trial-by-trial analytical approaches were implemented. One potential strategy is to select a stimulus based on a single feature domain (either its location or its identity) without considering the stimulus-location association. If persistent, this stimulus or location bias would interfere with task acquisition. A stimulus bias index was therefore calculated for each individual stimulus (plane, spider, and flower) as the total number of choices (maximum 60) - total number of correct responses for that stimulus (maximum of 30) / total number of correct responses for that stimulus (maximum of 30). Within a 90-trial session, each selection can only be correct 30 times, but occurs 60. Thus, a maximal bias for an individual stimulus would be 1. The total bias index was then calculated by adding up the 3 individual biases. The location bias index was calculated in the same way using location on the screen (left, center, right) as the feature parameter.

Win-stay and Lose-Shift Strategies.

Another potential strategy that could be used during PAL testing is the implementation of reward heuristics, where the choice selection on a trial is a function of the reward or lack thereof received on the immediately preceding trial. In this regard, rats could choose to adopt a win-stay strategy to stay with selecting a previously rewarded feature (either stimulus or location) without considering the stimulus-location association. For example, the selection of the flower in the left location resulted in a reward. Thus, on the subsequent trial the animal would select the left location even though the plane is in this location and that is an incorrect response. Similarly, if the flower were rewarded, the animal could select the flower on the next trial even though it was presented in the center location, which would be incorrect. Rats could choose to adopt a lose-shift strategy and not repeat the selection of a previous stimulus or location that was previously punished without considering the stimulus-location association and whether it is currently correct. The use of win-stay and lose-shift strategies were calculated as the total number of times a strategy was used / total number of times a strategy was possible. For each of the four possible strategies, stimulus win-stay, stimulus lose-shift, location win-stay, location lose-shift, the maximal bias is 1, with 0 indicating that the strategy was not used at all. These calculations included the presentation of pseudorandom duplicate trials and trials in which the win-stay or lose-shift strategies resulted in the correct response.

Maintenance of stimulus-location associations across test day.

To assess whether the aged rodents were impaired on PAL because of forgetting the stimulus-location associations they formed during the previous day’s session, average percent correct by discrete trial blocks was calculated and compared within and between daily test sessions. The 90 trials were divided into 3 blocks of 30 trials (1–30, 31–60, and 61–90) and percent correct was calculated for each individual block of trials. Values for the final 30 trials were only included if the rat completed at least 15 trials. A decline in performance between the last 30 trials one day and the first 30 trials of the subsequent testing day would be evidence of forgetting and an inability to maintain the newly formed associations. Measures of bias, strategy, and latency were also analyzed using a similar trial block format to assess maintenance of response type.

All trial-by-trial analyses were conducted using custom written code (MATLAB, MathWorks Inc, R2021A) that is available upon request. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism and the statistical software R.3.6.3. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Shaping performance was analyzed based on the number of days required to establish criterion at each stage of shaping in both young and aged groups. Behavioral data were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA), with the within subjects’ factor of testing day and the between-subjects factor of age group, unless specified otherwise. When appropriate, behavioral data were analyzed with t-tests with correction for unequal variances if necessary. The choice of statistical test was based on assumptions of normality, assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test and with Levene’s test.

3. RESULTS

3.1. PAL Task Performance and Latency.

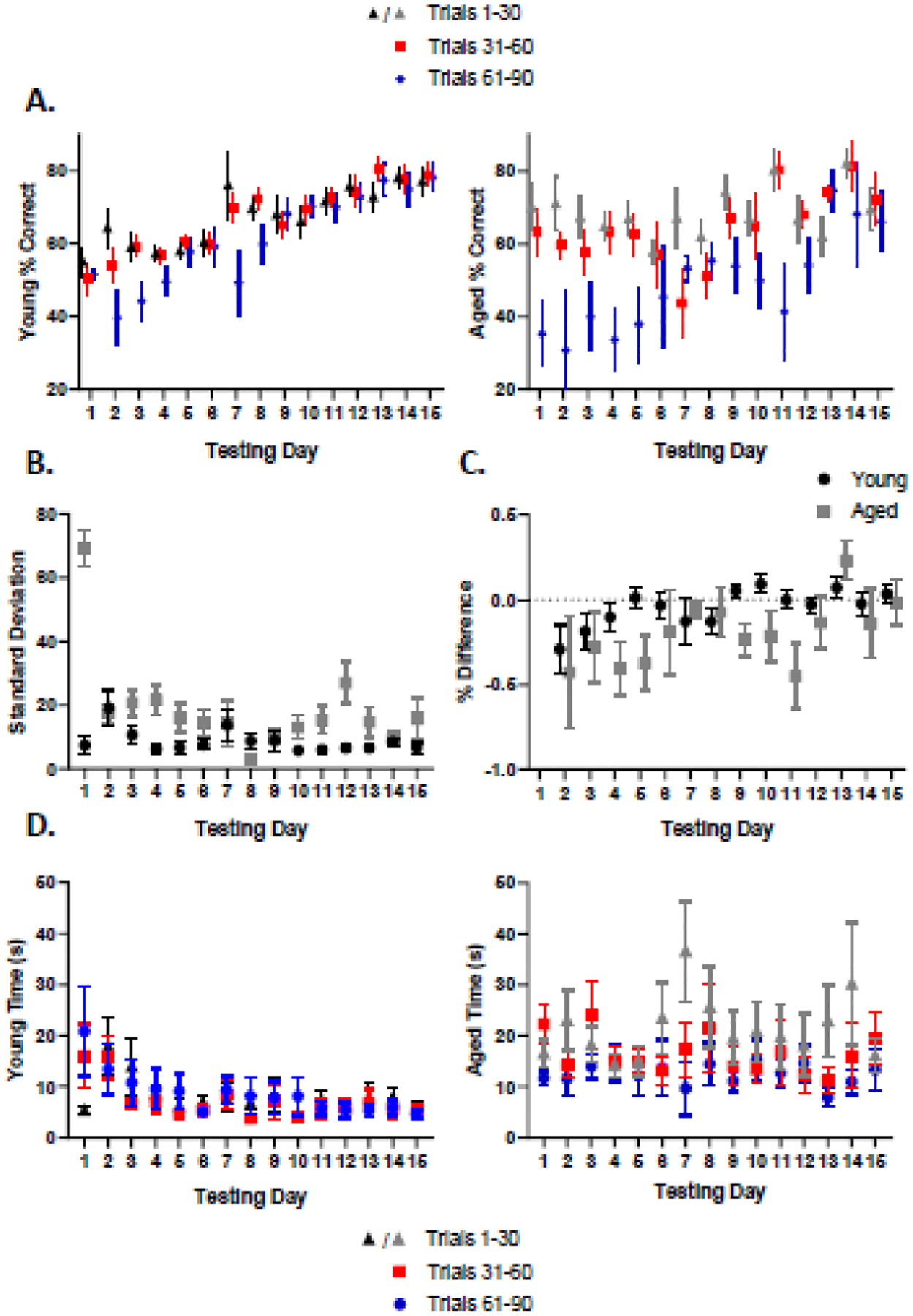

Young and aged rats were tested on PAL. Figure 2A shows the mean percent correct responses during the first 15 days of testing for young (black) and aged (gray) rats. RM ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of day (F(14,280) = 17.84, p < 0.0001), but there was not a significant main effect of age group (F(1,20) = 4.279, p = 0.0518). The day by age interaction effect did reach statistical significance, however (F(14, 280) = 2.340, p = 0.0045). This was likely due to the young rats’ performance across days 1–15 improving at a faster rate than was evident in the aged rats. To further understand this significant interaction effect, post-hoc contrast analysis revealed that both groups had a significant increase in performance on day 7 (F(1,20) = 9.779, p = 0.005). This was also the day when the age groups began to deviate significantly from one another (F(1,20) = 5.836, p = 0.025). Figure 2B shows the mean number of incorrect trials made prior to reaching a criterion performance of 83.33% for two consecutive testing days for both young and aged rats. Aged rats made significantly more incorrect trials compared to young animals before reaching criterion (T(20) = 2.339, p = 0.0298; Figure 2B). Furthermore, young rats took 22.83 ± 11.32 days to reaching criterion, whereas aged rats took 42.30 ± 15.43 days. This difference was statistically significant (T(20) = 3.412, p = 0.0028). Figure 2C shows the mean number of incorrect trials made across testing as a function of trial type for each age group. RM ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of age (F(1,20) = 5.149, p = 0.0345) as well as trial type (F(5,100) = 3.972, p = 0.0025). The age by trial type interaction did not reach significance (F(5,100) = 1.097, p = 0.3667). Post-hoc Tukey’s test of multiple comparisons found significant trial type differences in both groups between trial types 2 and 3 (p = 0.0257), 2 and 4 (p = 0.0041), and 2 and 6, (p = 0.0051). While these results are somewhat surprising, the lack of an interaction effect suggests that trial type 2 was simply easier for both age groups.

Figure 2: PAL Task Performance and Latency.

A) Percent correct responses (y-axis) on the PAL task shown across the first 15 days of testing (x-axis) for young (black; n = 12) and aged (gray; n = 10) rats. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed statistically significant main effects of day (F(14,280) = 17.84, p < 0.0001), and a day x age interaction (F(14, 280) = 2.340, p = 0.0045). B) Mean number of incorrect trials (y-axis) made by young and aged rats prior to achieving criterion of 83.33% correct for two consecutive days on PAL. C) Mean number of incorrect trials (y-axis) made across testing by young and aged rats as a function of trial type. RM ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of age (F(1,20) = 5.149, p = 0.0345) as well as trial type (F(5,100) = 3.972, p = 0.0025). D) Average 90-trial touch latency (y-axis) across 15 days of testing (x-axis) for young and aged animals. RM ANOVA revealed a significant interaction effect of day by age (F(14, 280) = 1.732, p = 0.0491). E) Average 90-trial latency (y-axis) separated into 5-day blocks (x-axis). The 5-day criterion block includes latencies for the two days of criterion performance achievement and the preceding three days. Both age groups had a significant decline in latency between days 1–5 and the 5-day criterion block (young: T(11) = 2.290, p = 0.0427; aged: T(9) = 3.678, p = 0.0051). F) Average latency (y-axis) across 15 days of testing as a function of trial type (x-axis). Two-way RM ANOVA of latency by trial type with age as a between-subjects factor showed a significant main effect of age (F(1, 20) = 5.716, p = 0.0268) and trial type (F(5, 100) = 2.583, p = 0.0306). Error bars are ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM), * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.005.

To examine the extent that young and aged rats may have differed in their processing speed and motor behavior, the latency between stimulus onset and time to touch the screen was analyzed across testing day and by trial type. Figure 2D shows the average latency for all trials completed across testing day for young and aged animals. RM ANOVA comparing latency across testing day with age as a between-subjects factor revealed a statistically significant main effect of age (F(1, 20) = 4.914, p = 0.0384), and a significant day by age interaction (F(14, 280) = 1.732, p = 0.0491). There was not a significant effect of day (F(14,280) = 1.610, p = 0.0758). This pattern of results was likely because the young animals had a tendency for latency to decrease across testing day with rats completing trials faster as they neared criterion performance. Because aged animals generally took more than 15 days to reach criterion, we could not observe this effect of decreasing latency within the same timeframe as the young animals. Thus, we also included a 5-day block of the days leading up to criterion performance, which represents different days for the young and aged rats relative to the start of testing, but equivalent days with respect to reaching criterion (Figure 2E). This analysis indicated that aged animals showed a similar pattern to young and had shorter latencies when nearing criterion compared to the start of testing. In fact, a paired-samples t-test showed that latencies were significantly faster during the final 5 days of testing compared to the first 5 days for both young (T(11) = 2.290, p = 0.0427), and aged rats (T(9) = 3.678, p = 0.0051). Finally, we analyzed latency as a function of trial type. Figure 2F shows the mean trial type latency for testing days 1–15. RM ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of age (F(1, 20) = 5.716, p = 0.0268) and trial type (F(5, 100) = 2.583, p = 0.0306), but no age by trial type interaction (F(5,100) = 2.217, p = 0.0584). Post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons revealed no significant differences in the young animals’ latency between trial types, but significant differences in the aged animal’s latencies between trial types 1 and 4 (p = 0.0013) and trial types 2 and 4 (p = 0.0270), with aged rats having the longest latencies for trial type 4.

3.3. Within Session Trial Block Performance and Latency.

To understand whether age-associated PAL task deficits could be explained by aged animals forgetting the associations made in the previous day’s session, a trial block analysis was conducted to see if rats showed improvements within a testing session that were lost at the beginning of testing on the subsequent day. This type of ‘saw tooth’ performance pattern in which aged rats may forget acquired information across days of testing has been observed during a variant of the Morris water maze test of spatial memory in aged rats (Foster, 2012; Guidi et al. 2014). Trials were separated into blocks of 30: 1–30, 31–60, and 61–90. Figure 3A shows the average percent correct by trial block for young (left) and aged (right). Across 15 days of testing, a mixed model ANOVA found young animals had a significant main effect of day (F(14, 410) = 21.07, p < 0.0001) and a significant day by trial block interaction (F(28, 410) = 2.070, p = 0.0013). There was no effect of trial block (F(2,33) = 2.974, p = 0.0650), and although there was a slight difference in performance between trial blocks 1–30 and 61–90 at the beginning of testing (post-hoc Tukey; p = 0.0382), this resolved over time with performance between trial blocks becoming more consistent by day 8. In contrast, the aged rats had main effects of both testing day (F(14, 212) = 2.771, p = 0.0008) and trial block (F(2, 27) = 11.39, p = 0.0003), but there was not a significant interaction between the two factors (F(28, 212) = 1.364, p = 0.1140). Furthermore, aged rats showed a tendency to perform worse over the entire course of testing by making significantly more errors during the last 30 trials compared to trials 1–30 and 31–60 (post-hoc Tukey; p=0.0002, 0.0036). To directly compare trial block performance between age groups, a mixed model was fit for both young and aged animals to analyze the effects of testing day and age on the difference in performance between trials 61–90 and trials 1–30. Across 15 days of testing, we found significant main effects of age (F(1,20) = 9.813, p = 0.0052), with age rats having a larger decline in performance between the early and late trials. There was also a significant effect of day (F(14,179) = 1.67, p = 0.0304), with rats showing smaller within session performance declines during the later testing days. The interaction of day and age, however, did not reach statistical significance (F(14,179) = 1.52, p = 0.1077). The less consistent performance of aged compared to young rats within a testing session is illustrated in Figure 3B, which shows the standard deviation between trial blocks across testing day.

Figure 3: Trial Block Performance and Latency.

A) Average percent correct (y-axis) for testing days 1–15 (x-axis) by trial block for young (black) and aged (gray) rats. While both age groups performed worse during trial block 61–90 during the first week of testing, the young rats overcame this by day 8 (day and trial block interaction; F(28,410) = 2.070, p = 0.0013, post-hoc Tukey; p = 0.0382). In contrast, the aged rats continued to perform worse during the later trial block across 15 days (day by trial block interaction; p > 0.05). B) Standard deviation in the percent correct across trial blocks (y-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) animals across 15 days of testing (x-axis). RM ANOVA detected significant main effects of age (F(1,20) = 45.25, p < 0.0001, Ɛ = 0.4020) and testing day (F(5.628,81.61) = 10.18, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction effect of testing day and age (F(14,203) = 11.06, p < 0.0001). C) Percent difference (y-axis) in performance between final 30 trials and first 30 trials (final 30 – first 30 / first 30). Positive values reflect forgetting of the information that was learned in the preceding testing session. Neither age group showed any significant indication of forgetting across 15 days of testing (y-axis). D) Average latency by trial block (y-axis) over testing day (x-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) rats. Neither age group had significant differences between trial block (trial block factor; p > 0.05 for both measures). Young rats showed a significant effect of testing day (F(14, 434) = 5.695, p < 0.0001), whereas the aged group did not (p > 0.05). These results parallel the overall latency findings for young rats across days 1–15. Error bars are ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM).

When the effect of age and testing day on standard deviation between all three trial blocks was analyzed with a mixed model ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser’s correction, there was a significant main effect of age (F(1,20) = 45.25, p < 0.0001, Ɛ = 0.4020) and testing day (F(5.628,81.61) = 10.18, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction effect of testing day and age (F(14,203) = 11.06, p < 0.0001), which is likely related to the observation that the standard deviation changed across testing days in the young rats more than the aged. The observation that aged rats performed worse during the final 30 trials, rather than the first 30, suggests that they were not ‘forgetting’ learned associations within a testing session prior to the next day of testing. To further demonstrate this point, Figure 3C shows the difference in performance between the final 30 trials and the first 30 trials on the subsequent day of testing. Positive values would reflect forgetting the information that was learned in the preceding testing session.

The worsening performance of aged rats in later trial blocks of a single testing session could suggest that they satiated more quickly and were less motivated as testing went on. To examine this possibility, the mean latency as a function of testing block was also examined, as longer latencies could be indicative of reduced motivation. Figure 3D depicts latency as a function of trial block. For young animals, RM ANOVA revealed a significant effect of testing day (F(14,434) = 5.695, p < 0.0001). There was not a significant effect of trial block (F(2, 33) = 0.0418, p = 0.9591) or a testing day by trial block interaction (F(28, 434) = 0.8076, p = 0.7480). For aged animals, there was no effect of testing day (F(14,280) = 0.5407, p = 0.9078), trial block (F(2,27) = 1.435, p = 0.2557), or testing day by trial block interaction (F(28, 280) = 0.8877, p = 0.6332). Additionally, RM ANOVA for the difference in latency between trial blocks 3 and 1 for the age groups revealed a significant effect of age (F(1,20) = 6.829, p = 0.0171), likely reflecting the day effect seen in young but not aged rats. Together, these findings reveal that there was not a significant difference between the three trial blocks for either the young or the aged rats, suggesting that motivation for reward did not change as a function of testing. Furthermore, the testing day effect seen in young animals parallels the overall latency findings for testing days 1–15 and indicates that across all trial blocks there was a tendency for young, but not aged rats, to get faster.

3.4. Response-Related Biases During PAL Testing.

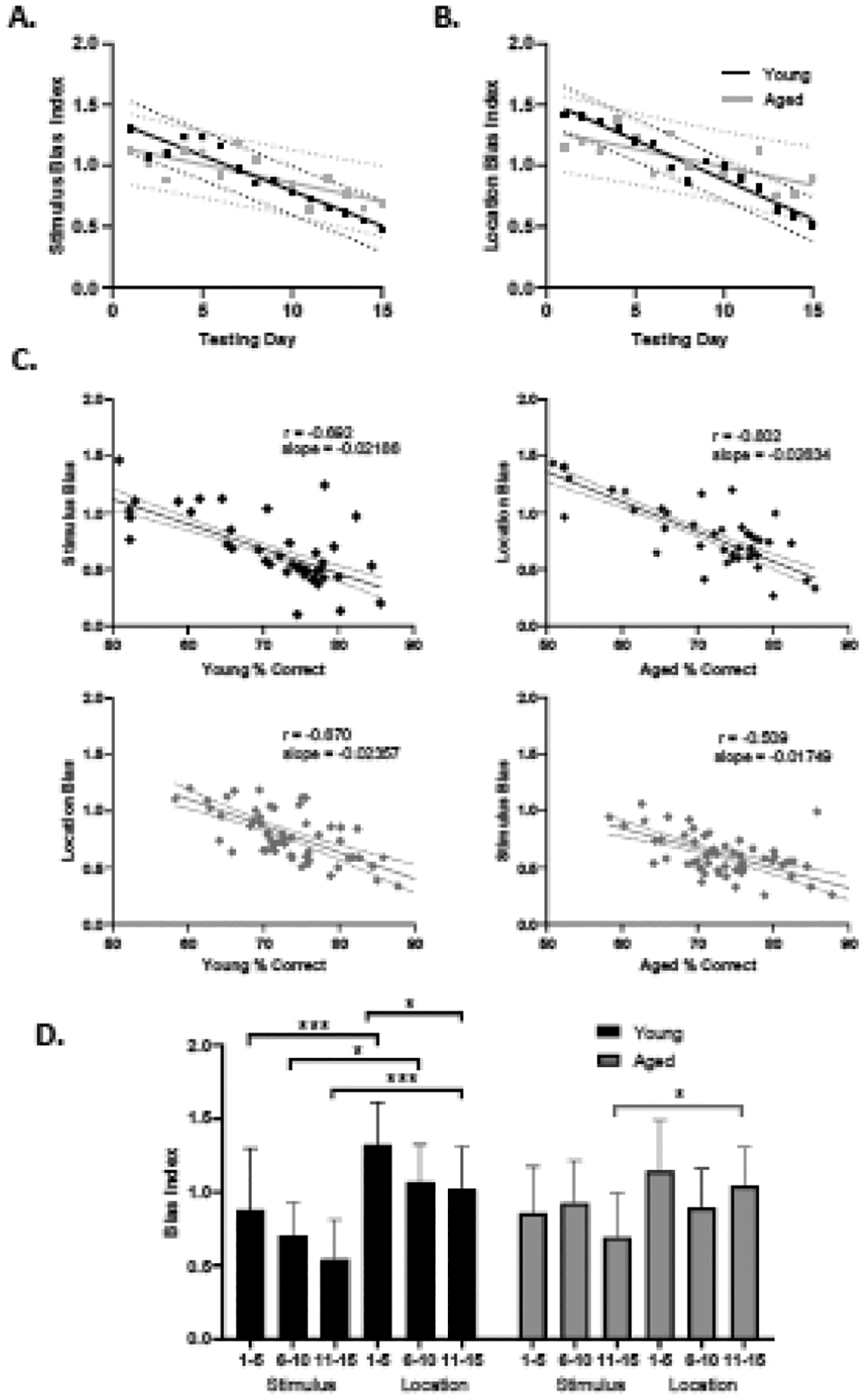

To examine potential age effects in response-related biases on PAL task performance, a bias index was calculated for the feature parameters of both location and stimulus as described in section 2.5. Plots depicting the linear regression of average bias index over the first 15 days of testing are shown in Figures 4A (stimulus) and Figure 4B (location). A significant effect of test day on response bias was found for both the stimulus feature (F(14,280) = 4.166, p < 0.0001) and the location feature (F(14,280) = 4.919, p < 0.0001). There was not a significant effect of age or age and test day interaction for either feature parameter (location: F(1,20) = 0.1189, p = 0.7338; age x test day: F(14, 280) = 1.390, p = 0.157; stimulus: F(1,20) = 0.02748, p = 0.8700; age x test day F(14, 280) = 1.401, p = 0.1516).

Figure 4: Stimulus and Location Biases.

A) Linear regression of stimulus bias (y-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) across 15 days of testing (x-axis). RM ANOVA found a significant main effect of time (F(14,280) = 4.166, p < 0.0001). B) Linear regression of location bias (y-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) across 15 days of testing (x-axis). RM ANOVA found a significant main effect of time F(14,280) = 4.919, p < 0.0001. For both the stimulus (T(20) = 2.846, p = 0.0100) and location (T(20) = 3.695, p = 0.0014) bias indices, the slopes were significantly more negative in the young compared to aged rats. C) Plots depicting the correlation between percent correct (x-axis) and stimulus or location bias respectively (y-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) rats across all days of testing. D) Representation of Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons for stimulus and location bias (y-axis) in 5-day blocks (x-axis). * denotes p < 0.05 and *** denotes p < 0.001.

The lack of a significant age by day interaction in either the location or stimulus bias could be due to the fact that young rats stopped testing once they reached criterion, so we could not make age comparisons past day 15, which limited the ability to detect age differences in response bias. The observation of a steeper slope in the young animals’ bias regressions (Figures 4A/4B), and the observation that lower bias values correlated with higher percent correct (Figure 4C), however, warranted further investigation. Thus, linear regressions were calculated from the average bias across all animals in an age group for each day of testing. For both the stimulus (T(20) = 2.846, p = 0.0100) and location (T(20) = 3.695, p = 0.0014) bias indices, the slopes were significantly more negative in the young compared to aged rats.

Furthermore, we also compared the use of stimulus versus location bias across testing by blocking days into three groups of five sessions. The mean biases for young and aged rats were plotted in Figure 4D. Tukey’s test of multiple comparisons for the bias indices indicated that young animals were more likely to show a location bias compared to a stimulus bias during days 1–5, 6–10, and 11–15 (p =0.0009, p = 0.0101, p = .0003, respectively). Additionally, young animals had a significant decrease in their stimulus bias between days 1–5 and 11–15 (p = 0.0305). In contrast, aged animals only had a significant difference between the stimulus and location bias index during the third test day block (days 11–15; p = 0.0360). Moreover, the overall bias indices of the aged rats did not significantly change across test day blocks (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). To directly compare both stimulus and location biases in one model, the difference between average location and stimulus biases across 15 testing days was analyzed in a mixed effects model. This found no significant effects of day, age, or interaction between day and age (F(14,257) = 1.481, p = 0.1181, F(1,20) = 0.1306, p = 0.7216, F(14, 257) = 0.5482, p = 0.9025), suggesting that age did not significantly impact the likelihood that a rat would have one type of bias over another.

The faster rate of abandoning a response bias in the young rats compared to the aged group could have resulted from looking over a range of testing days in which the young rats reached criterion, but the aged did not. To control for this, a potential relationship between use of a response bias and performance across all testing days was examined by looking at the relationship between bias index for stimulus or location and the percent correct. Figure 4D shows the relationship between percent correct and stimulus or location bias, respectively, for young (black) and aged (gray) rats. Both age groups had a higher correlation between percent correct and location bias (young; r = −0.802 p < 0.0001, aged; r = 0.670 p < 0.0001) than percent correct and stimulus bias (young, r = −0.692, p < 0.0001, aged; r = −0.509, p = 0.001), but this was not statistically significant (young; z = 0.535, p = 0.296, aged; z = −0.467, p = 0.32). While aged animals tended to have less tight correlations between bias and percent correct, this difference also did not reach statistical significance (stimulus; z = −0.576, p = 0.282, location; z = 0.582, p = 0.28). Together these data indicate that the ability to abandon any response bias in the PAL task is critical for performance improvements regardless of age.

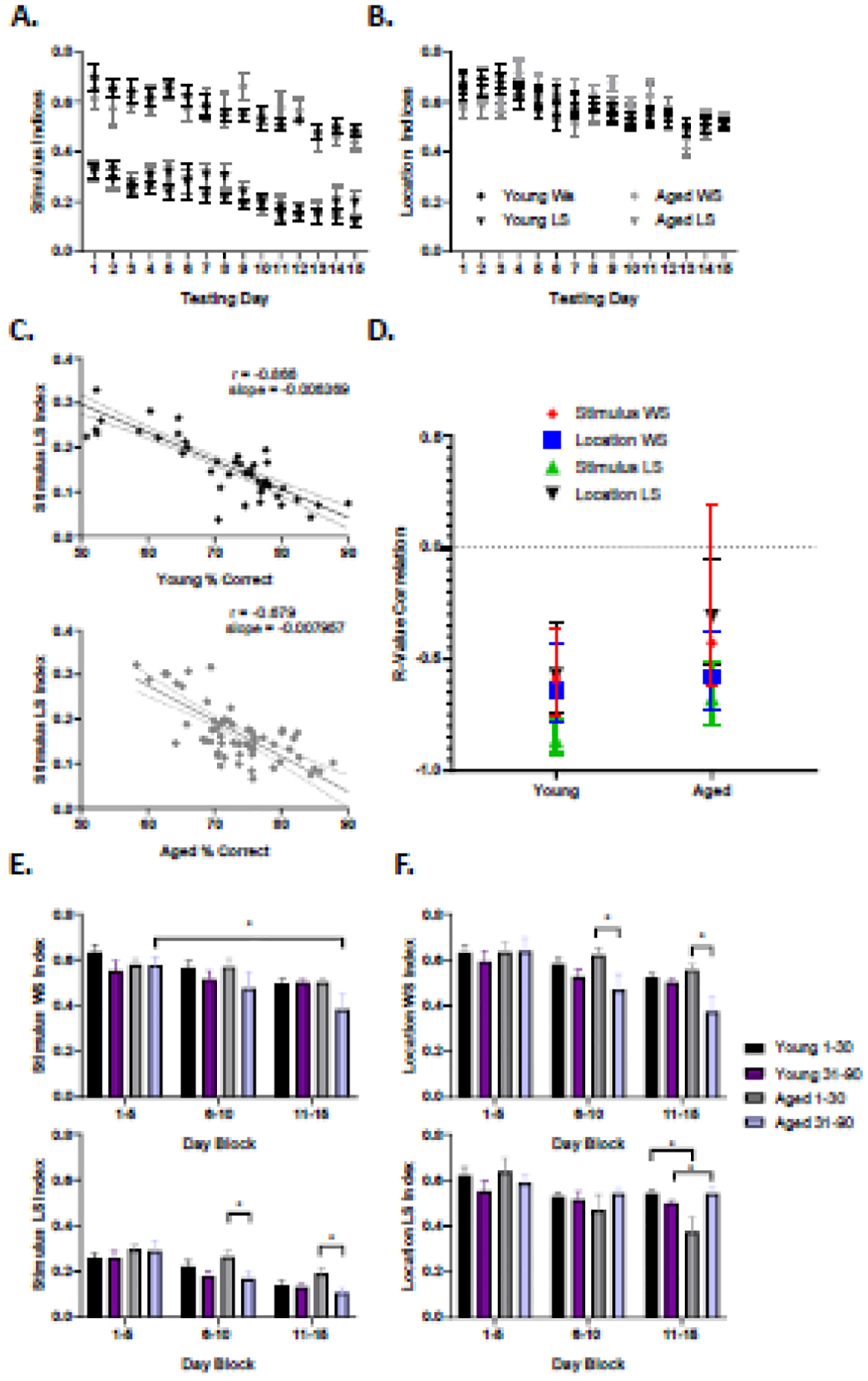

3.5. Outcome-related Strategy Implementation During PAL Testing.

While stimulus and location response biases provide some insight into performance variables that could impact learning on the PAL task, rats may also employ outcome-related heuristics that can be evaluated by examining the use of win-stay and lose-shift responding. To understand the impact of these task-solving strategies on PAL performance across age groups, win-stay and lose-shift indices were calculated as described in section 2.5. Win-stay and lose-shift responding can also be related to stimulus or location so these were calculated separately. The average win-stay and lose-shift indices for stimulus-based responding and location-based responding is shown Figures 5A and 5B, respectively.

Figure 5: Outcome-based Strategies.

A) Average outcome strategy index (y-axis) across 15 testing days (x-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) rats with stimulus as the feature parameter for win-stay strategies (circle) and lose-shift (square) strategies. All rats exhibited a downward trend of both strategies as a function of testing day (stimulus win-stay; F(14,280) = 4.530, p < 0.0001, stimulus lose-shift; F(14,280) = 5.393, p < 0.0001). B) Average outcome strategy index (y-axis) across 15 testing days (x-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) rats with location as the feature parameter. All rodents exhibited a downward trend of both strategies as a function of testing day (location win-stay; F(14,280) = 4.270, p < 0.0001, location lose-shift; F(14,280) = 3.450, p < 0.0001). C) Representative example of stimulus lose-shift strategy (y-axis) by percent correct (x-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) rats throughout all testing days. Stimulus lose-shift was the most highly correlated strategy with percent correct for both age groups and was therefore chosen as a representative. D) Average Pearson R-value correlation coefficients for outcome strategies vs. percent correct (y-axis) for young and aged rats. High variability between strategies and subjects can be seen in the aged cohort, though this was not statistically significant.

Both age groups exhibited strategy indices that significantly decreased across testing day (location win-stay: F(14,280) = 4.270, p < 0.0001; location lose-shift: F(14,280) = 3.450, p < 0.0001; stimulus win-stay: F(14,280) = 4.530, p < 0.0001; stimulus lose-shift: F(14,280) = 5.393, p < 0.0001). For stimulus strategies, RM ANOVA found significant main effects of strategy type (F(1,300) = 208.3, p < 0.0001), with win-stay being used more frequently than lose-shift. There was not a significant main effect of age (F(1, 20) = 0.9638, p =0.3270), but the age and strategy type interaction did reach significance (F(1,300) = 9.928, p = 0.0018). This was due to the young rats showing a greater difference between the use of win-stay over lose-shift than did the aged rats. For location strategies, RM ANOVA with a within-subjects measure of strategy type (win-stay vs. lose-shift) and between-subjects measure of age found significant main effects of strategy type with win-stay being used more frequently than lose-shift (F(1,300) = 16.10, p < 0.0001), but there was not a significant main effect of age (F(1,20) = 0.3243, p = 0.5685). The interaction effect of age by strategy type did reach statistical significance, however (F(1,300) = 4.919, p = 0.0273), with aged rats showing a greater difference in the use of win-stay over lose-shift responding compared to young rats.

Because we sought to understand how the use of task-solving strategies influenced task performance, strategy was also examined with regards to percent correct across all testing days. Both age groups had the highest correlation between percent correct and stimulus lose-shift (young; r = −0.866, p < 0.0001, aged; r = −0.679, p < 0.0001), followed by location win-stay (young; r = −0.638, p < 0.0001, aged; r = −0.581, p < 0.0001), stimulus win-stay (young; r = −0.588, p < 0.0001, aged; r = −0.427, p = 0.001) and finally location lose-shift showed the smallest correlation (young; r = −0.568, p < 0.0001, aged; r = −0.308, p = 0.018). Figure 5C shows representative examples of the use of a stimulus lose-shift (LS) strategy by percent correct for a young rat (left) and an aged rat (right). For all outcome-based strategies in both age groups, higher percent correct correlated with lower strategy use. Figure 5D is a summary plot depicting the R-value correlations between percent correct and all strategies for both age groups. While aged animals tended to show greater group variability for all strategies, the correlation values did not significantly differ between the young and aged groups (z > −1.645, p > 0.05 for all comparisons).

3.6. iPAL Performance.

Finally, to test whether vulnerability to interference from an irrelevant distractor was related to PAL task performance, performance on iPAL was compared across testing days for young and aged rats (Figure 6A). Two-way RM ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of test day (F(9,180) = 6.549, p < 0.0001), but no significant effect of age (F(1,20) = 2.452, p = 0.1331) or day by age interaction (F(9,180) = 0.6219, p = 0.7775). Figure 6B shows the mean number of incorrect trials to criterion performance on iPAL (2 consecutive days of 83.33% correct). There was no significant difference between age groups in the numbers of incorrect trials made (T(16) = 0.3796, p = 0.7092).

Figure 6: Interference (i)PAL.

A) Percent correct performance (y-axis) on iPAL across 10 days of testing (x-axis) for young (black) and aged (gray) rats. Two-way ANOVA found only a significant main effect of time F(9,180) = 6.549, p < 0.0001. B) Mean number of incorrect trials (Y-axis) needed to achieve criterion performance (83.33% for two consecutive days) for young (black) and aged (gray). There were no differences in incorrect trials between age groups (p > 0.05). C) Comparison of percent correct (y-axis) during the first five days of PAL, 5 days up to criterion of PAL, and first 5 days of iPAL. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of 5-day block (F(2,40) = 113, p < 0.0001). D) Linear regression of error type across 10 days of iPAL for young and aged rats. Error was separated into interference and associative error, adding to a total proportion of 1. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction effect F(27,360) = 1.940, p = 0.0039. Post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons revealed significant differences between the two error rates on day 2 (young; p = 0.0042, aged; p = 0.0263). Additionally, day 2 saw a significant difference between the age groups on both interference and associative error (p = 0.0115 for both comparisons). E) Error rates for PAL criterion 5-day block and all 10 days of iPAL. iPAL error rate is again proportioned into associative and interference error for iPAL. Across the 10 testing days of iPAL, error rate is significantly increased compared to PAL criterion (F(3,80) = 1.328, p = 0.2627), but interference and associative error rates make up comparable proportions of the total error rate (F(3,80) = 1.328, p = 0.2627) for both age groups. Error bars are ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM), and *** denotes p < 0.001.

To directly compare PAL and iPAL performances and determine how the distraction stimulus affects performance, percent correct for the first 5 days of PAL, the 5 days leading up to criterion achievement in PAL (Criterion PAL), and the first 5 days of iPAL were compared for the young and aged rats (Figure 6C). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of testing block (early PAL, late PAL, iPAL) (F(2,40) = 113.0, p < 0.0001), but no effect of age (F(1,20) = 0.1675) or age by PAL/iPAL block (F(2, 40) = 1.922, p = 0.1596). Post-hoc Tukey’s comparisons found there were significant differences between the first 5 days of PAL vs. the 5 days just prior to reaching criterion on PAL, and the 5 days just prior to reaching criterion PAL vs. iPAL (p < 0.0001 for all measures). When tested on iPAL, both groups showed a comparable decrease in performance, but they did not revert to original performance during the first 5 days of PAL testing, as indicated by the significant difference between the first 5 days of PAL and the first five days of iPAL (young; p < 0.0001, aged; p =0.005). Thus, both young and aged rats showed substantial savings of the learned associations in the presence of the distractor.

In iPAL, two types of errors can be made: an interference error (error made by selecting the irrelevant maple leaf distractor) and an associative error (error due to incorrect choices unrelated to maple leaf selection). Figure 6D shows a linear regression of total iPAL error across 10 days of testing proportioned into these two types. Two-way ANOVA of these proportions revealed no effects of age or time (p > 0.05) but did reveal a significant interaction effect (F(27,360) = 1.940, p = 0.0039). Post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons revealed significant differences between the two types of errors on day 2 (young: p =0.0042; aged: p =0.0263). Additionally, day 2 saw a significant difference between the age groups on both interference and associative error (p = 0.0115 for both comparisons). Taken together, these results indicate that at the beginning of testing, interference errors are more prevalent than associative, but over time, there is no difference between these two errors as the number of interference errors made by young and aged rats decreased. Additionally, at the beginning of testing there was a slight difference between age groups, with aged animals having more interference errors, but this difference waned after day 2.

To further unpack these results, error rate (# errors / total trials) for 5 PAL criterion days and 10 days of iPAL is depicted in Figure 6E. For iPAL, the error rate was again proportioned into interference versus associative error. Error rate between PAL and iPAL was significantly different (F(3,80) = 39.81, p < 0.0001), but there were no effects of age or age by PAL/iPAL interaction (p > 0.05) paralleling results from Figure 6C. Furthermore, total error in PAL and associative error in iPAL were directly compared because associative error is the only error type possible in PAL. In this case, there was not a significant effect of PAL/iPAL (F(3,80) = 1.328, p = 0.2627). Additionally, there were no effects of age by PAL/iPAL interaction (p > 0.05). Together, these results suggest that the extra error seen during the first 10 days of iPAL for both age groups was due to the addition of possible interference errors rather than an increase in associative errors indirectly related to maple leaf interference, as indicated by the similar rates of associative error in PAL and iPAL.

4. DISCUSSION

This study documents the impaired acquisition of stimulus-location associations in aged male rats on a clinically relevant behavioral paradigm: Paired Associates Learning (PAL). Furthermore, trial-by-trial analyses were performed to examine potential age differences not immediately apparent by percent correct alone. Specifically, the overall age-related deficits in PAL performance (Figures 2A and 2B) appeared to result from aged rats being slower to abandon response-driven behaviors of selecting a stimulus based on a single feature (Figures 4A and 4B) as well as having an increased error rate during later trials in a 90-trial session (Figures 3A, 3B and 5E-H). Furthermore, this observation of increased error rate in later trials for aged animals is consistent with a previous finding on a match-to-position test of spatial memory (Johnson et al. 2016). These complementary observations made across different behavioral paradigms highlight that aged rats may be more vulnerable than young to proactive interference that accumulates over testing session.

Previous studies in our lab have probed animals’ abilities to acquire stimulus-location associations in rats using the object-place paired associated task (OPPA; Lee & Solivan, 2008), or the working memory/biconditional association task (WM/BAT; Hernandez et al. 2018b). Both behavioral tasks require rats to select between two different 3-dimensional objects presented simultaneously. The choice of the correct object depends on the place in the maze. Specifically, one object would be correct in the west region of the maze and the other object would be correct in the east. Several lines of evidence suggest that prior to learning the stimulus-location rule on WM/BAT and OPPA, rats use an egocentric response-based strategy in which they select an object on a particular side (that is, left or right) regardless of the object identity or region of the maze (east or west) (Hernandez et al. 2015; Lee & Solivan, 2008; Lee & Byeon, 2014; Jo & Lee, 2010). The magnitude of an animal’s tendency to use a response-based strategy is calculated with a side bias index. Aged rats have an elevated side bias over weeks of training compared to young animals (Hernandez et al. 2018b, 2020b; Colon-Perez et al. 2019). Furthermore, suppression of side bias as training progresses has been shown to correspond with an increase in correct responses guided by the task-specific rule (Hernandez et al. 2015, 2017; Lee & Byeon, 2014). Despite differences in the touchscreen platform used in the current study and maze-based tests of object-location associations, we observed response-driven behavior that was elevated early in testing and decreased over time more rapidly in young compared to aged rats (Figure 4A, 4B).

In the current study, testing parameters and analyses were designed to investigate the possibility of three distinct, but not mutually exclusive, hypotheses to explain age-related deficits in PAL acquisition. One hypothesis is that age-related PAL deficits arise from the aged animals’ vulnerability to distraction and environmental interference. In fact, older human study participants are more vulnerable to interference from irrelevant information than their younger counterparts (Gazzaley et al. 2005; Gazzaley et al. 2008). To test this hypothesis, we developed interference (i)PAL, which added an irrelevant distractor to the empty panel on the testing touchscreen. This level of interference is low, as the distractor has nothing to do with the task itself. That is, no interaction with the distractor is required (Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009; Clapp et al. 2011; Clapp and Gazzaley, 2012; Gray et al. 2017). Interestingly, the performance of young and aged rats was similarly disrupted on iPAL (Figures 6A and 6B) and the increased error rate between PAL and iPAL was due mainly to animals making interference errors (touching the maple leaf) rather than additional associative errors (incorrect non maple leaf touches) (Figure 6E). These results suggest that aged rats are not more susceptible to low levels of distraction than young animals, and do not make more associative errors due to distraction.

Another hypothesis that was tested is whether young and aged rats similarly shifted or maintained a response depending upon outcome. There are multiple strategies that can be employed during the learning of the PAL task: choosing to stay with a certain stimulus or location regardless of correctness (response-driven bias), choosing to stay with a choice that was previously rewarded (win-stay), and choosing to shift from a choice that was previously unrewarded (lose-shift). It is likely that successful completion of the PAL task requires a constant updating of strategies until the correct association is made. Previous data indicate that aged rodents may be more behaviorally rigid (Beas et al. 2017) and more likely to employ response-based strategies (Barnes & Nadel, 1980). Elderly adults’ selections in choice tasks are better fit by win-stay/lose-shift strategies than reinforcement-learning strategies (Worthy & Maddox, 2014), and aged rodents have both win-stay and lose-shift deficits in reversal learning tasks (Means & Holsten, 1992). We therefore looked at win-stay and lose-shift outcome responding. We found that overall win-stay and lose-shift responding between age groups shared similar trajectory (Figure 5A and 5B) by decreasing over testing sessions at similar rates and showing a significant correlation with percent correct across age groups (Figure 5D). Moreover, both age groups were more likely to employ win-stay over lose-shift strategies, and this was particularly evident for stimulus-based responses. The lack of a significant age effect on win-stay or lose-shift strategy use suggests that was outcome responding was not a substantial contributor to age-related PAL deficits.

A final hypothesis we explored was whether variability in memory could serve as a potential explanation for differences in task acquisition. Loss of encoded information between test sessions could potentially delay criterion achievement for the aged rats. Studies in rodents have shown that aged rats are impaired on search and recall trials that rely on the rat’s ability to remember conditions from previous trials (Foster & Kumar, 2007; Guidi et al. 2014). There is also evidence of poorer hippocampal memory consolidation in aged rodents (Bach et al. 1999; Gerrard et al. 2008). Thus, it is conceivable that aged rodents have impaired memory retention, and a potential loss of encoded information between test sessions could delay criterion achievement for the aged rats. Evidence to support this theory would be a decrease in performance in the first trials of a session compared to the final trials of the preceding session. When the average performance across blocks of 30 trials within a session was examined, we found no evidence to support this. We did, however, observe that performance decreased in the later trials and that this decrease was most evident in the aged animals (Figures 3A and 3C). This age-related performance decline did not appear to be due to differences in motivation, as the reaction time of the aged rats did not slow. In fact, aged animals tended to get faster in the later trials (Figure 3D). These data suggest that aged rats performed worse in later trials independent of satiation or motivational decreases.

The observation that aged animals performed worse than young in the later trial blocks suggest that older animals may be more vulnerable to proactive interference that accumulates across a session. Both age groups displayed their lowest performance during trials 61–90 in the initial days of testing. Across days of testing, however, the young rats were able to overcome this trend, whereas the aged rats did not. It is possible that when aged rats must make difficult associations across an increasing number of trials, they begin to default to previously stored information to complete the trial. This vulnerability to proactive interference could be exacerbated by the fact that across the trial types within the PAL task, all stimuli and locations being presented are technically correct during one of the trial types. A similar enhanced vulnerability to proactive interference in aged compared to young rats has been observed in a previous study that measured rats’ ability to discriminate between spatial locations with a delayed matching-to-position task (Johnson et al. 2016). In this task, rats had to discriminate between two spatial locations when the proximity of the locations was parametrically varied between trials. Young and aged performed similarly when the locations were far apart, but when the locations were closer together, age-related deficits on spatial discrimination were observed. Importantly, this age-related deficit was primarily due to aged rats’ declining performance on late relative to early trials. The authors hypothesized that these decrements in performance on late trials resulted from a greater potential for cumulative interference as trials pass and representations of previous task goals accumulate. This interpretation is consistent with the current data even though the two tasks are strikingly different. Moreover, the current data and findings from Johnson et al. are relevant to observations from human study participants. Relative to young adults, older subjects are particularly susceptible to proactive interference on working memory tests when similar stimuli are presented (Lustig and Hasher, 2001; Rowe et al. 2010).

The current data point to the reported neurobiological mechanisms that support PAL performance in the touchscreen platform being vulnerable in advanced age, which is consistent with previously published findings. For example, cholinergic hypofunction has been described extensively in the aged brain (Schliebs & Arend, 2011; Cooper et al. 1994; Stroessner-Johnson et al. 1992), and PAL task acquisition has been shown to be facilitated by the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil (Bartko et al. 2011). Additionally, pharmacological manipulations of the dopaminergic system (Lins et al. 2015), as well as administration of PCP and amphetamine (Talpos et al. 2014) have been shown to cause impairments on PAL. Similarly, striatal dopamine has been shown to be dysregulated in age (Bäckman et al. 200; Braskie et al. 2008). PAL has also been shown to be sensitive to detected cognitive decline in preclinical AD models (Saifullah et al. 2020). Our findings of PAL impairment during the normal aging process indicate a need for further investigation into the similarities between normal and pathological age impairment in the PAL task. In this regard, trial-by-trial analysis may be able to elucidate diverging behavioral phenotypes between normal cognitive aging and disease models. Finally, performance on OPPA and PAL appear to involve common brain regions with hippocampal inactivation leading to impairments on both tasks (Lee and Solivan, 2008; Talpos et al. 2009). While OPPA performance also critically relies on activity in the perirhinal and medial prefrontal cortices (Jo &Lee, 2010; Hernandez et al. 2017), the necessity of these structures for PAL performance has not yet been empirically examined and requires further investigation. It may also be fruitful to determine if age-related PAL impairments are related to elevated activity in the dorsal striatum, as observed in WM/BAT (Colon-Perez et al. 2019).

Animal models have long served as effective models of human cognition due to their similarity in both behavioral phenotypes and homologous structures. The emergence of touchscreen behavioral testing in preclinical science has allowed researchers to expand upon existing behavioral paradigms by providing more rigorous experimental control and homologous testing to those used in clinical work. Nonverbal tasks such as the PAL task have been routinely used in clinical settings for many years with dependable results in assessing changes in cognition associated with aging (Robbins et al. 1994; Blackwell et al. 2004). The ability to administer these tasks to animal models in a way that closely mirrors clinical settings will pave the way for improving assessments across species and the development of therapeutic interventions. Additionally, these computerized behavioral exams provide the ability to perform trial-by-trial analysis that can provide further insight into behavioral performance and standardize methods of analysis. Future studies will aim to identify relevant regions critical to the acquisition of multi-modal associations and further understanding of how cellular mechanisms are integrated into network level disruptions associated with aging through using the behavioral analysis pipeline derived from this study.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Aged male rats are impaired in PAL task acquisition relative to young.

Age-related impairments may stem from proactive accumulating interference.

Response-driven behavior translates from 3-D mazes to 2-D touchscreens.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NIA R01AG049722/2RF1AG049722 (SNB), the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, the University of Florida University Scholars Program (MR), and the McNair Scholars Program (AMR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement of Verification

The work described in the current manuscript has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere. Its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copy right holder.

Conflict of Interest

Authors report no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- Ash JA, Lu H, Taxier LR, Long JM, Yang Y, Stein EA, Rapp PR, 2016. Functional connectivity with the retrosplenial cortex predicts cognitive aging in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(43), 12286–12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach ME, Barad M, Son H, Zhuo M, Lu YF, Shih R, Mansuy I, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, 1999. Age-related defects in spatial memory are correlated with defects in the late phase of hippocampal long-term potentiation in vitro and are attenuated by drugs that enhance the cAMP signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(9), 5280–5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Bird F, Alexander V, Warburton EC, 2007. Recognition memory for objects, place, and temporal order: a disconnection analysis of the role of the medial prefrontal cortex and perirhinal cortex. J Neurosci 27(11), 2948–2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Warburton EC, 2015. Object-in-place associative recognition memory depends on glutamate receptor neurotransmission within two defined hippocampal-cortical circuits: a critical role for AMPA and NMDA receptors in the hippocampus, perirhinal, and prefrontal cortices. Cereb Cortex 25(2), 472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Nadel L, Honig WK, 1980. Spatial memory deficit in senescent rats. Can J Psychol 34(1), 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JH, Blackwell AD, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW, 2016. The Paired Associates Learning (PAL) Test: 30 Years of CANTAB Translational Neuroscience from Laboratory to Bedside in Dementia Research. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 28, 449–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Vendrell I, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, 2011. A computer-automated touchscreen paired-associates learning (PAL) task for mice: impairments following administration of scopolamine or dicyclomine and improvements following donepezil. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 214(2), 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beas BS, McQuail JA, Ban Uelos C, Setlow B, Bizon JL, 2017. Prefrontal cortical GABAergic signaling and impaired behavioral flexibility in aged F344 rats. Neuroscience 345, 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beraldo FH, Palmer D, Memar S, Wasserman DI, Lee WV, Liang S, Creighton SD, Kolisnyk B, Cowan MF, Mels J, Masood TS, Fodor C, Al-Onaizi MA, Bartha R, Gee T, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Strother SS, Prado VF, Winters BD, Prado MA, 2019. MouseBytes, an open-access high-throughput pipeline and database for rodent touchscreen-based cognitive assessment. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizon JL, Foster TC, Alexander GE, Glisky EL, 2012. Characterizing cognitive aging of working memory and executive function in animal models. Front Aging Neurosci 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell AD, Sahakian BJ, Vesey R, Semple JM, Robbins TW, Hodges JR, 2004. Detecting dementia: novel neuropsychological markers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 17(1–2), 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braskie MN, Wilcox CE, Landau SM, O’Neil JP, Baker SL, Madison CM, Kluth JT, Jagust WJ, 2008. Relationship of striatal dopamine synthesis capacity to age and cognition. J Neurosci 28(52), 14320–14328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Thome A, Plange K, Engle JR, Trouard TP, Gothard KM, Barnes CA, 2014. Orbitofrontal cortex volume in area 11/13 predicts reward devaluation, but not reversal learning performance, in young and aged monkeys. J Neurosci 34(30), 9905–9916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Holmes A, Lyon L, Mar AC, McAllister KA, Nithianantharajah J, Oomen CA, Saksida LM, 2012. New translational assays for preclinical modelling of cognition in schizophrenia: the touchscreen testing method for mice and rats. Neuropharmacology 62(3), 1191–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Padain TL, Skillings EA, Winters BD, Morton AJ, Saksida LM, 2008. The touchscreen cognitive testing method for rodents: how to get the best out of your rat. Learn Mem 15(7), 516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, Ginovart N, Dixon RA, Wahlin TB, Wahlin A, Halldin C, Farde L, 2000. Age-related cognitive deficits mediated by changes in the striatal dopamine system. Am J Psychiatry 157(4), 635–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp WC, Gazzaley A, 2012. Distinct mechanisms for the impact of distraction and interruption on working memory in aging. Neurobiol Aging 33(1), 134–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp WC, Rubens MT, Sabharwal J, Gazzaley A, 2011. Deficit in switching between functional brain networks underlies the impact of multitasking on working memory in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(17), 7212–7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Perez LM, Turner SM, Lubke KN, Pompilus M, Febo M, Burke SN, 2019. Multiscale Imaging Reveals Aberrant Functional Connectome Organization and Elevated Dorsal Striatal. eNeuro 6(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JD, Lindholm D, Sofroniew MV, 1994. Reduced transport of [125I]nerve growth factor by cholinergic neurons and down-regulated TrkA expression in the medial septum of aged rats. Neuroscience 62(3), 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC, 2012. Dissecting the age-related decline on spatial learning and memory tasks in rodent models: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in senescent synaptic plasticity. Prog Neurobiol 96(3), 283–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC, Kumar A, 2007. Susceptibility to induction of long-term depression is associated with impaired memory in aged Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem 87(4), 522–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RS, Newman LA, Mohler EG, Tunur T, Gold PE, Korol DL, 2020. Aging is not equal across memory systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem 172, 107232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Clapp W, Kelley J, McEvoy K, Knight RT, D’Esposito M, 2008. Age-related top-down suppression deficit in the early stages of cortical visual memory processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(35), 13122–13126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, Rissman J, D’Esposito M, 2005. Top-down suppression deficit underlies working memory impairment in normal aging. Nat Neurosci 8(10), 1298–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemperle AY, McAllister KH, Olpe HR, 2003. Differential effects of iloperidone, clozapine, and haloperidol on working memory of rats in the delayed non-matching-to-position paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 169(3–4), 354–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard JL, Burke SN, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, 2008. Sequence reactivation in the hippocampus is impaired in aged rats. J Neurosci 28(31), 7883–7890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DT, Smith AC, Burke SN, Gazzaley A, Barnes CA, 2017. Attentional updating and monitoring and affective shifting are impacted independently by aging in macaque monkeys. Behav Brain Res 322(Pt B), 329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi M, Kumar A, Rani A, Foster TC, 2014. Assessing the emergence and reliability of cognitive decline over the life span in Fisher 344 rats using the spatial water maze. Front Aging Neurosci 6, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Hernandez CM, Campos K, Truckenbrod L, Federico Q, Moon B, McQuail JA, Maurer AP, Bizon JL, Burke SN, 2018a. A Ketogenic Diet Improves Cognition and Has Biochemical Effects in Prefrontal Cortex That Are Dissociable From Hippocampus. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Maurer AP, Reasor JE, Turner SM, Barthle SE, Johnson SA, Burke SN, 2015. Age-related impairments in object-place associations are not due to hippocampal dysfunction. Behav Neurosci 129(5), 599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Reasor JE, Truckenbrod LM, Campos KT, Federico QP, Fertal KE, Lubke KN, Johnson SA, Clark BJ, Maurer AP, Burke SN, 2018b. Dissociable effects of advanced age on prefrontal cortical and medial temporal lobe ensemble activity. Neurobiol Aging 70, 217–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Reasor JE, Truckenbrod LM, Lubke KN, Johnson SA, Bizon JL, Maurer AP, Burke SN, 2016. Medial prefrontal-perirhinal cortical communication is necessary for flexible response selection. Neurobiol Learn Mem 137, 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Reasor JE, Truckenbrod LM, Lubke KN, Johnson SA, Bizon JL, Maurer AP, Burke SN, 2017. Medial prefrontal-perirhinal cortical communication is necessary for flexible response selection. Neurobiol Learn Mem 137, 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Truckenbrod LM, Barrett ME, Lubke KN, Clark BJ, Burke SN, 2020a. Age-Related Alterations in Prelimbic Cortical Neuron. Front Aging Neurosci 12, 588297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AR, Truckenbrod LM, Campos KT, Williams SA, Burke SN, 2020b. Sex differences in age-related impairments vary across cognitive and physical assessments in rats. Behav Neurosci 134(2), 69–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman DL, Swan M, 2010. Use of a body condition score technique to assess health status in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 49(2), 155–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner AE, Heath CJ, Hvoslef-Eide M, Kent BA, Kim CH, Nilsson SR, Alsiö J, Oomen CA, Holmes A, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, 2013. The touchscreen operant platform for testing learning and memory in rats and mice. Nat Protoc 8(10), 1961–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YS, Lee I, 2010. Disconnection of the hippocampal-perirhinal cortical circuits severely disrupts object-place paired associative memory. J Neurosci 30(29), 9850–9858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Sacks PK, Turner SM, Gaynor LS, Ormerod BK, Maurer AP, Bizon JL, Burke SN, 2016. Discrimination performance in aging is vulnerable to interference and dissociable from spatial memory. Learn Mem 23(7), 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas BD, Bergman J, 2017. Touchscreen technology in the study of cognition-related behavior. Behav Pharmacol 28(8), 623–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Heath CJ, Kent BA, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, 2015. The role of the dorsal hippocampus in two versions of the touchscreen automated paired associates learning (PAL) task for mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232(21–22), 3899–3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston RF, Wood ER, 2010. Associative recognition and the hippocampus: differential effects of hippocampal lesions on object-place, object-context and object-place-context memory. Hippocampus 20(10), 1139–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Byeon JS, 2014. Learning-dependent Changes in the Neuronal Correlates of Response Inhibition in the Prefrontal Cortex and Hippocampus. Exp Neurobiol 23(2), 178–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Solivan F, 2008. The roles of the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in a spatial paired-association task. Learn Mem 15(5), 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lins BR, Phillips AG, Howland JG, 2015. Effects of D- and L-govadine on the disruption of touchscreen object-location paired associates learning in rats by acute MK-801 treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232(23), 4371–4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, May CP, Hasher L, 2001. Working memory span and the role of proactive interference. J Exp Psychol Gen 130(2), 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister KA, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, 2013. Dissociation between memory retention across a delay and pattern separation following medial prefrontal cortex lesions in the touchscreen TUNL task. Neurobiol Learn Mem 101, 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]