Abstract

Over recent years, an increase in alcohol-related problems has been noted in China. Taking effective measures against the problem requires clear reviewing and understanding of the evolution of the Chinese alcohol policy. This study is aimed to evaluate the alcohol policy with special focus on reviewing the alcohol production and consumption situation in China and assessing the changes in Chinese alcohol policy along with other related fields. This article finishes with a set of recommended policy changes that could help solve the recent alcohol-related problems and analyze the major impediments.

Keywords: alcohol management, alcohol policy, China, public health

1. Introduction

The urgent need for reducing alcohol-related harm through instituting alcohol policies has received worldwide attention and recognition. From 1975 to the 1980s, the World Health Assembly paid much attention to issues concerning alcohol reduction and made numerous resolutions. In 2005, the World Health Assembly spearheaded by the Director-General designed excellent policies and intervention measures for reducing alcohol-related harm and unanimously seconded the implementation and evaluation strategic proposals in all the represented member states [1]. After several rounds of consultations, and discussions, key amendments were made and global strategy was seconded and adopted in the 63rd session of the World Health Assembly in 2010 [2]. The strategy clearly highlights the proven operational and effective measures to forward the policy as a feasible means of control to all and the relevant areas in context. Thereafter, the alcohol policy has attracted global attention.

Several alcohol-related studies focusing on the alcohol policies of the USA [3], UK [4], Australia [5], New Zealand [6], Russia [7,8], Japan [9], and Africa [10,11] have been undertaken. However, there is little information regarding the same subject in relation to China's alcohol policy. China has a long history of alcohol production and consumption, most notably the excessive drinking of alcoholic beverages on special occasions that has been a custom for thousands of years. In recent decades, China has experienced a rapid increase in alcohol production and consumption compared to other parts of the world, which is strongly associated with increased trends of social and alcohol-related problems in China [12]. This clearly indicates that China still lacks a good alcohol policy, which urgently calls for more study and amendment of the alcohol policies in place. Here, we review alcohol production and consumption, and the evolution of the alcohol policy in China. Then we make recommendations regarding the key areas within the current alcohol policy that require amendments with an overall aim of contribution towards the reducing alcohol-related consequences within China.

2. Review of alcohol production and consumption in China

Archaeological discoveries and the literature show that the Chinese alcohol history stretches back 8000 years [13]. As early as 5000 BC, Chinese ancient people had acquired the relevant knowledge of brewing along with drinking etiquette. Over the years, grain has been the main raw material for alcohol production, which presents a threat to the country's food security. Alcohol still plays a very important role in the development of agricultural in China and in other social occasions such as worship, funerals, marriages, and festivals and in the daily lives of Chinese people. The development of the alcohol industry demands more grain; however, this presents a possible threat of food scarcity that may result in famine since China has a large population. Bearing that in mind along with the past experiences, the government considers imposing restrictions on the development of the alcohol industry to avoid a repeat of the past situation. During the thousands of years of Chinese alcohol history, each dynasty has attempted to impose measures on alcohol production, always with the intention of avoiding a possible food crisis. Those measures did not, however, solve the problem of food insecurity in any dynasty. Therefore this presents an ideological basis for government to design a policy to control the alcohol industry. Currently, all the trends of social and political problems have been linked to alcohol. However, the government policy is still unclear on its stand on alcohol production risking the possibility of facing a similar situation and challenges as cited in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911).

According to the statistical data compiled on the development of alcohol industry after the establishment of the Republic of China (1912), the current total output of the Chinese brewing industry is > 9.03 millions of tons [14]. While the magnitude of beer and wine production is almost negligible, Chinese white spirit, accounts for about 94% of the total output, and rice wine, medicinal alcohol, and homemade alcohol take up the remaining percentage [14]. For over 100 years, white spirit has remained the main consumed alcohol in China compared to the current highly produced beer as well as wine. In 1915, the Beijing National Government transformed the alcohol management guidelines into a national policy. A series of laws and regulations were instituted, the tax system was redesigned and aligned with the national financial revenue and the budget expenditure system. At the same time, the government reformed the existing alcohol tax rate and tax system, adopted a sale system similar to the monopoly sale imposed on tobacco and alcohol license tax, which like other business taxes have strengthened the management alcohol production and distribution. For the first time, an import tax was imposed on imported alcohol [14]. However, for unclear reasons, the production and consumption of Chinese alcohol still remained low and alcohol-related problems were less pronounced and thus did not attract attention at the national level.

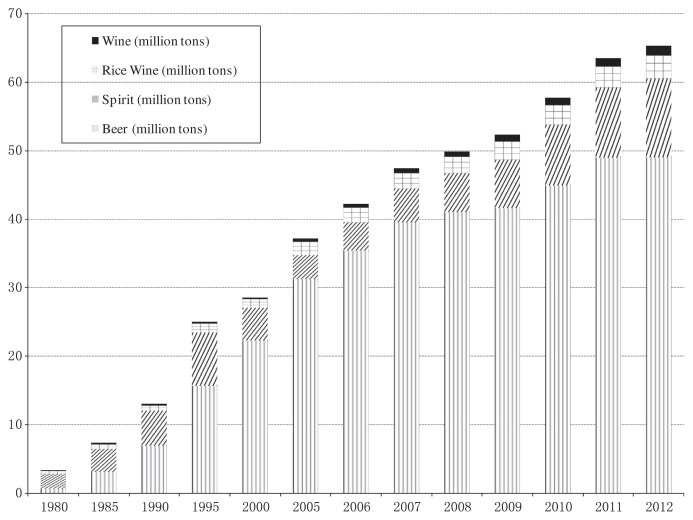

Since the establishment of the dominant Mainland China Communist Party in 1949, there has been rapid growth of the alcohol industry and the emergence of alcohol-related problems. Lately, there has been an overall sharp increase of Chinese alcoholic beverage consumption (Fig. 1), irrespective of the source and type, coinciding with the fact that by 2002 China was the world's leading beer producer. In 2001, the percentage beer marketing level was 73.1% compared to the 26% white spirit production of total alcoholic beverage sales in China [15]. By 2011, beer production had reached 48.99 billion L, which accounted for 77%, while white spirit production was 10.26 billion L, which accounted for 16%. From the consumption point of view, a decrease in white spirit consumption was associated with the increase in beer consumption. World Health Organization (WHO) statistics indicate that the per capita alcohol consumption of pure alcohol in China was 1.03 L in 1970, and had risen to 5.17 L by 1996 [16]. According to the 2011 WHO report, China's pure alcohol consumption was 5.91 L per capita with an average drinking rate of 10.60 L/ drinker. The consumption rate of pure alcohol derived from beer, wine, white spirit, and other alcoholic beverage was 1.50 L, 0.15 L, 2.51 L, and 0.23 L, respectively [17]; spirit still remains the main source of Chinese pure alcohol intake.

Fig. 1.

National consumption of alcoholic beverage in China (million tons).

In traditional Chinese culture, drinking is socially embraced and it is considered to be less of a social problem [18]. However, excessive drinking can be regarded as defective to personal moral cultivation and may cause a series of personal alcohol-related problems. Until the late 1980s, there was a significant change in the Chinese society, a rapid development of Chinese alcohol industry, and a sharp rise in alcohol-related problems such as alcoholism, alcohol intoxication, and increased road accidents due to drink-driving, which aroused the concern of researchers [19–22]. Until the late 1970s, alcohol-related problems were neglected due to cultural, economic, and ethnic reasons [23]. Since the early 1980s, patterns of alcohol consumption in China have changed rapidly [24]. The amount of alcoholic beverages produced and consumed in China have steadily increased, with consumption increasing by almost 10-fold from 1978 to 1996 [25]. The modern Chinese society primarily comprises urban and rural subpopulations both with a passion and cultural attitude towards the custom of alcohol drinking. The variations in the rates of drinking may depend on factors such as subpopulations, and geographic location resulting in different behaviors and problems. The rural set-up bears a relatively high proportion of heavy drinkers but the urban population scores the highest overall drinking rates [26]. Although income is not the definitive causative factor of increased alcohol consumption, other factors such as sociodemography, education, employment, marital status, and, most strikingly, differences in regional origin are also suggested to significantly contribute to the subject [27]. Most notably violence, crime, economics, and family are among the numerous short-term alcohol consumption related consequences, but physical, mental, public health, and social are the most pronounced long-term consequences, yet the China government does not have any outstanding programs and plans in place to counteract alcohol consumption and its associated problems [12].

3. Evolution of alcohol policy since 1949

In recent decades, the Chinese alcohol policy has transformed from monopoly to a multiple management system. An elaborate review on the entire evolution process and the various efforts made by the government is instrumental in understanding the existing alcohol-related problems and the current alcohol policy in China.

3.1. Alcohol monopoly of the People's Republic of China

Prior to constituting the national regime, the Chinese Communist Party implemented the alcohol monopoly in the areas under their rule to limit alcohol consumption, save grain for food and as a way of supplementing the military income. In January 1951, the Ministry of Finance held the first national monopoly conference, in which the monopoly management system on alcoholic commodities was confirmed. In May 1951, the Ministry of Finance issued the Provisional Regulations on Monopoly and unified management of the national alcohol monopoly. The high alcohol consumption rate among Chinese people presented a great potential source of revenue; therefore, through monopoly the government would obtain huge tax revenue that could be used for developing the nation. Since grain was the main raw material of alcohol, the government monopoly system would perfectly regulate the alcohol production according to the grain harvest status to ensure sustainable food availability.

After the Three Years of Natural Disaster (1959–1961) and a series of unsuccessful exploration, China was faced with great difficulties. Among them was the widespread famine and lack of food in many provinces resulting in millions of people starving to death [28]. Facing this grim situation, with the support of the government, the alcohol industry launched a series of research activities, focusing on saving food and searching for alternative raw materials that could be used in alcohol production, to supplement and improve the traditional brewing technology. With the very high market demand, legitimate manufacturers were unable to meet the calls, as a result rural village communities, organizations, schools, farms, and other units reverted to crude methods of brewing such as bootlegging flooding the market with poor quality products. On August 22, 1963, the State Council issued a notice, stressed the need to continue implementing the alcohol monopoly policy, further strengthening the alcohol monopoly system.

During the 1966–1976 Great Cultural Revolution, there was a massive transfer of personnel from one area to another, which greatly weakened the alcohol monopoly status in most areas. A special report compiled and submitted to the State Council on April 5, 1978 highlighted the need of strengthening the alcohol monopoly system. On May 3, 1978, the Ministry of Commerce urged all the respective local authorities to establish alcohol monopoly implementing committees and to urgently recruit personnel, to streamline all alcohol production, distribution, retail activities, and to revise the Provisional Regulations on Monopoly in reference to the original monopoly management framework. Basing on the set guidelines, Guizhou, Guangdong, Hebei, Ningxia, and other provinces drafted their respective relevant alcohol administrative provisions.

From 1949 to the early 1980s, the Chinese alcohol monopoly management was in place to the planned economic system, low social productivity, and widespread poverty in Chinese residents. Communist China used a highly centralized Soviet model of administration where the alcohol-related issues were totally under monopoly management [7]. As an important source of revenue under the planned economic system, alcohol monopoly generated a lot of income that was used in the national development, and the spontaneous increase in the national treasury. Although the overall agricultural productivity of China was extremely low, the use of gain as the raw material for alcohol production was noted to be the main cause of food crisis. The problem persisted even after the establishment of the People's Republic of China; this was marked by the tragic memories of the Three Years of Natural Disasters when millions of Chinese starved to death [28]. The government then strongly imposed the alcohol monopoly and unified management system as a means to regulate alcohol production and consumption to minimize the use of the food grain as a raw material for alcohol production. However, because alcohol production, technology, and the consumption levels were low, it was easy to implement the alcohol monopoly system. No doubt the monopoly system of administration was an effective management tool at the time, given the historical background.

3.2. The conspired downfall of the alcohol monopoly system

In the 1980s China embarked on practicing reforms and an open policy nationally and this greatly impacted the alcohol management, resulting in wild alcohol production. There was no more respect for laws and regulations managing the retail sale and distribution. All the established alcohol departmental structures were disbanded, so the monopoly system was gradually abolished and the government could not effectively manage alcohol production, marketing, and distribution. There was overall increased alcohol production, distribution, adulteration, and use of grain as a raw material for alcohol production; this sparked public demand for a draft law to regulate alcohol production and related issues.

On December 18, 1990, State Council Premier Li Peng presided over the 129th premier office conference that was dedicated to addressing alcohol production and related concerns. The meeting unanimously resolved that there was urgent need to address the existing appalling alcohol management status. This was to be spearheaded by the State Council Bureau of Legislative Affairs in conjunction with the Ministry of Light Industry and Commercial Department and other Departments. They were tasked to analyze the conspired downfall of the alcohol monopoly management system by the People's Republic of China and to determine if it was necessary to revive the system or not. After the conference, each department made a comprehensive search on the subject and the findings were submitted to the State Council for implementation and used in 1991 to draft an alcohol management ordinance [29].

The Alcohol Management Ordinance (Draft) highlighted that, in order to improve alcohol production and sales management, ensure the quality of alcohol product, save grain for food, protect the lawful operation, safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of consumers, and ensure national fiscal revenue, the government needed to control alcohol production systematically. The State Council alcohol administration department under the Ministry of Light Industry was mandated to formulate alcohol regulations, industrial development planning, issue production license, and jointly monitor the alcohol-related legal issues with other relevant departments as a way of encouraging the development of low-degree alcohol products and limiting high-degree alcohol production. All alcohol-producing enterprises were required to obtain a production permit. Private brewery business owners were prohibited from making any kinds of alcoholic beverages for profit purposes. Alcohol distribution was to be controlled by the Ministry of Commerce and its subordinate agencies along with alcohol marketing issues and issuing licenses. All the prominent national alcohol brands were to be sold by authorized retail argents. Alcohol management organs were established and regulations released before the draft was approved by the government and was to be implemented on the provincial level.

Originally, the State Council convened with the intentions of formulating a nationwide ordinance on alcohol production and distribution, standardizing the alcohol management, making new laws, and where necessary upgrading the existing laws. However, the drafted ordinances were faced with a number of limitations, such as the lack of legal impact in association with the national regulations. According to China's legislative practice, the alcohol management regulations issued by the People's Congresses were more effective than those imposed by the administrative departments. Coordinating different departments proved to be hard under the adopted decentralized management approach since each department has its own interests. Transforming from a free departmental alcohol management approach to a limited legal system has proved to be tough in China. The current revived economy plan strongly supports the protection to the famous national alcohol brands and state-owned enterprise, which is not in agreement with previous rapid development market economy that prevailed in the early 1990s. As a result, the Alcohol Management Ordinance (draft) have not been implemented and the mandated authorities have since still remained in their respective industrial, commercial, taxation departments, and local governments.

3.3. Discussions on the restoration of monopoly

Although the central government did not fully abolish the alcohol monopoly system, the alcohol production and distribution management system is yet to be resolved on the national level. There exists independent management in industrial, commercial, taxation, and other departments, posing a great challenge to the provincial government. The existing vibrant management chaos and alcohol monopoly revival have sparked the interest of many officials and scholars. During the National People's Congress (NPC) convention held in 1991, 31 representatives including Zhu Ermei suggested the draft of a tobacco and alcohol monopoly law. In 1995, some NPC representatives proposed that there was urgent need to draft an alcohol monopoly law.

The Ministry of Domestic Trade argued that the alcohol management system was far from perfect, and lacked effective uniform management measures coupled with the chaos within the Chinese alcohol market. With the lack of production standards and distribution, there are high chances of circulating poor quality alcohol products resulting in loss of tax revenue. In view of this, the restoration of the alcohol monopoly was the only way forward. The government would formulate the Alcohol Monopoly Regulations to strengthen the management of alcohol production and overall marketing and that the national agency would be responsible for the Ministry of Domestic Trade. Later on, a delegation from the Ministry of Domestic Trade went to the USA to study their relevant management experience further. However, this arrangement did not bear any fruit towards the restoration of alcohol monopoly.

While inspecting the Ministry of Finance in 2003, Premier Wen Jiabao suggested that there was need to conduct research on the alcohol monopoly system. On August 15, 2003, the National Development and Reform Commission organized convened a forum attended by the Bureau of Legislative Affairs of the State Council, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Commerce, the State Administration of Taxation, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, the State Quality Inspection Administration, and the China Brewing Industry Association to discuss China's alcohol production monopoly fully. On September 2, 2003, the National Development and Reform Commission held the alcohol monopoly enterprise forum attended by the main liquor, beer, and wine enterprises and the China Brewing Industry Association; thereafter they went to Sichuan, Xinjiang, Shanghai and other places launching studies geared towards alcohol monopoly and held discussions with the local relevant departments, alcohol associations, and enterprises. In November, 2003, the National Development and Reform Commission issued the research plan that required all provinces to make a detailed investigation on ways of addressing the alcohol monopoly problem and sent experts to Sichuan, Shanghai and other places, to establish if there was need to revive the alcohol monopoly. Through a series of research projects, all the relevant alcohol management related departments deemed it necessary to establish a complete set of feasible alcohol management approaches, and found that the monopoly system did not address the situation in relation to national development.

The existing management chaos resulted in a series of problems in alcohol production and consumption in China. In response, the Ministry of Domestic Trade, or the Ministry of Finance, expressed the need for the concerned departments to exercise monopoly. However even after years of discussions, the proposal to revive the monopoly system is yet to be implemented. Interestingly, after years of intensive rounds of the discussion, people have gradually realized that so many departments and the alcohol industry had selfish interests regarding the restoration of the alcohol monopoly management to the extent that some deliberately opposed the reintroduction of the alcohol monopoly. The numerous rounds of discussions on alcohol monopoly policy recovery resulted in two opposing thoughts. With one faction seconding that alcohol monopoly is the only weapon for controlling the alcohol production and marketing disorder and the other side insisting that the monopoly approach could not stand the heavy responsibility and challenges at stake that a pressing matter that urgently required to be addressed by alcohol legislation. “Under the situation, Xiao Derun vice chairman China Brewing Industry Association by then declared that the monopoly system was to adapt to the open market and WTO [World Trade Organization], to improve the alcohol industry” [30]. Despite all those efforts, China is yet to have a unified national alcohol law and regulations that matches the development of market economy system as well the situation. Although it is not conducive to control alcohol production and consumption, and strengthen the alcohol industry management systems, the urgency and relevance make it an issue.

4. Alcohol policy in China

The current Chinese alcohol supervision and management system mainly focuses on aspects such as issuing production licenses, taxation, distribution, and advertising. With regard to production, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology system is mandated with issuing production license with strict consideration of quality but it no longer issues production licenses to new spirit manufacturers. There are a few reports on alcohol policies encompassing taxation, laws on drink and driving, selling alcohol to minors, control over market supply, licensing, and regulation of availability of alcohol in China [31]. In this article, we exhaustively describe the alcohol industrial policy, taxation, distribution, advertisement, minimum age of alcohol purchase, packaging and the inclusion of public health warning labels. In general, the current alcohol policy in China has contributed less to public health concerns (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of alcohol policy in China and Japan.

| Areas of policy | China | Japan |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction of availability | ||

| Monopoly on production and sale | No | No |

| Retail sale and production licensing system | Yes | Yes |

| Off-premise retail sales | No restrictions (include hours, days, places, etc.) | No restriction |

| Minimal legal drinking age | No | 20 |

| Density of alcoholic outlets | 0.5%, no maximum limit | 1% or more alcohol by volume |

| Price | No provisions | Beer–cola ratio: 1.53 Relative cost: decreasing |

| Tax | Yes (by type of alcoholic beverages) | Yes (by type of alcoholic beverages) |

| Drink-driving legislation | Yes (Road Traffic Law) | Yes (Road Traffic Law) |

| Advertising | Yes (Regulation of Alcohol Advertising) | No restrictions |

| Sponsorship | No restrictions | No restrictions |

| Warning labels | Recommended (“Excessive drinking is harmful to your health”, “Pregnant women and young children should not be drinking”, etc.) | Administrative guidance (by the National Tax Agency) Voluntary code (by alcoholic beverage industry) |

| Alcohol-free environment | No provisions | No provisions |

4.1. Alcohol industrial policy

Through strategic planning, the Chinese government has strongly encouraged and guided the development of the alcohol industry, resulting in a steady increase in alcohol production. In the provincial governments, such as Henan, Shandong, Jiangsu, Hubei, Sichuan, and Guizhou, policies and regulations have been instituted to improve on the alcohol industry development. Although mainly focused on the white spirits industry, the successful application of alcohol legislations in the above-mentioned provinces sets a good precedent for all the other regions in China. For example, Guizhou province is an important alcohol-producing area located in the southwest of China that formulated a series of laws and regulations as measures to support and encourage the development of the alcohol-making industry but with special focus on strong drinks. Similarly, the increased support for the development of Kweichow Moutai spirits has played a leading role marketing of Moutai spirit brand, creating Guizhou White Spirit brand, enhancing the overall competitiveness of Guizhou white spirit, strengthening the environmental protection, comprehensive utilization of resources, and the accelerated construction of high quality raw materials base.

4.2. Alcohol taxation

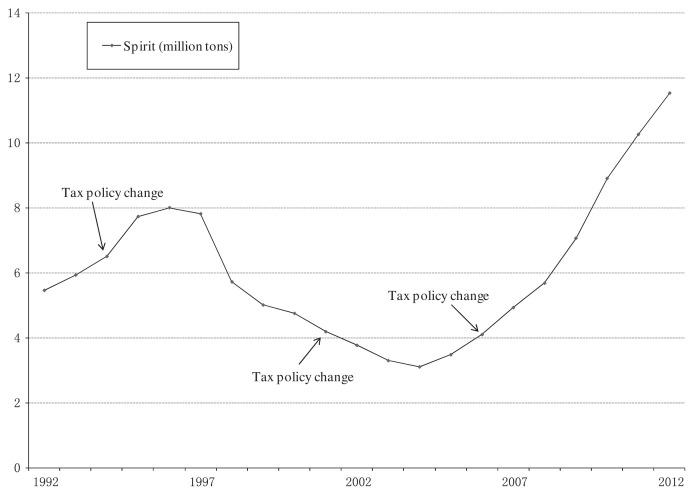

The relationship between the increase in alcohol taxes and the reduction in alcohol-related harm has well been established since the 1980s in China. In 1984, the Chinese government began to levy taxes on grain-produced alcohol, grain alcohol tax rate 50%, and potato alcohol 40%. An increase in alcohol tax levy is cited to impact reduction in alcohol-related harm [32]. In 1994, the State Council passed the Provisional Regulations of the People's Republic of China, extending the alcohol tax levy from just production to the consumption tax, the tax rate declined compared to that originally levied. On January 1, 2009, the newly revised consumption tax regulations were implemented, but the tax rates were just reaffirmed (Table 2). But in the real tax practice, alcohol-making enterprises are also required to pay value added tax, business tax, enterprise income tax, personal income tax, city maintenance and construction tax, urban education surtax, local education surtax, price regulation fund, stamp duty, and other various taxes and fees. Although the current alcohol taxation rate is relatively low, it is clear that overall alcohol taxation in China has been used to raise the government revenue without any effort to improve public health [31]. In 1994, the sprit tax rate dropped from 50% to 25%, followed by a sharp increase in alcohol outlets (Fig. 2). In 2001, a specific tariff of 0.5 Yuan per 500 g or 500 mL on spirit was levied until 2004, and a dramatic decrease in sprit production was reported. In 2006, the government discontinued differential taxation on potato and grain spirit, fueling acute increase in alcohol production.

Table 2.

Alcohol tax rates (%) by types of alcoholic beverages.

| 1984a | 1994b | 2001c | 2006d | 2009e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain spirit | 50 | 25 | 0.5 Yuan/500 mL | 20 | 20 |

| Potato spirit | 40 | 15 | 0.5 Yuan/500 mL | 20 | 20 |

| Beer | 40 | 220 Yuan/ton | 220 or 250 Yuan/ton | 220 or 250 Yuan/ton | |

| Rice wine | 50 | 240 Yuan/ton | 240 Yuan/ton | ||

| Other alcoholic beverage | 13–30 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Edible alcohol | 10 | 5 | 5 |

Other alcoholic beverages include reproduction liquor (30%), fruit wine and sparkling wine (15%), medicinal liquor (13%), spirit distilled by bran (28%), distilled by other raw materials (15%) and indigenous sweet alcohol (38%).

Quota tax rates were 220 Yuan/ton for beer, 240 Yuan/ton for rice wine. Flat tax rates on other kinds of alcoholic beverages were set.

Beer tariff was divided into two grades, a 250 Yuan/ton and 220 Yuan/ton.

Tax rates on grain spirits and potato spirits were unified.

Tax rates have not been changed since 2006, and the tax rates were reaffirmed in 2009.

Fig. 2.

Spirit outlets and tax policy changes from 1992 to 2012.

4.3. Regulate the distribution

In 2005 the Ministry of Commerce introduced two industry standards specifying the minimum operation requirements and management guidelines that were meant to be followed by the different stake holders engaged in alcohol wholesale and retail trading activities [33,34]. This was designed to regulate alcohol market distribution management at wholesale and retail levels, ensuring the sale of high quality alcohol products and documentation of all transactions to allow traceability. The standard mainly focuses on the alcohol distribution and was recommended to be voluntarily adopted by the involved enterprises. Surprisingly, the two standards have since become the pioneers of alcohol distribution management change and have been endorsed by Commerce Minister Bo Xilai as the ideal alcohol circulation management approach [35]. This approach ultimately streamlines the alcohol distribution, promotes systematic development of the alcohol market, protects alcohol producers, and operators, and the legitimate rights and interests of consumers. Furthermore the inclusion of the registration and tracking system ensures traceability of the distributed alcohol from the factory to the point of final consumption. However, the approach does not cater for other stages such as the raw material distribution and after purchase from the designated outlets. The Ministry of Commerce is mandated to supervise and administer nationwide alcohol circulation through the establishment of commerce departments or other certified agencies.

4.4. Restrictions on alcohol advertising

The State Administration for Industry and Commerce was charged with overseeing all alcohol advertisements. On November 17, 1995, the body released the first alcohol advertising regulations [36,37], which specified that alcohol advertising labels were required to state details such as product name, trademark, packaging of alcohol, and name of alcohol company and also highlighted the information not to be presented to the public (Table 3). With the development of the mass media reforms, this regulation has been further revised, but there are no contents on the network advertising. At the same time, illegal alcohol advertising is a serious problem. According to a report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the most serious is the illegal alcohol advertising becoming exceeding amount to the standard. There are drinking actions in some advertising, and others directly or indirectly owing success at personal, business, society level to alcohol drinking. There is a conflict between the Regulation of Alcohol Advertising and the Management Approach of Advertisement Broadcasting by the State Administration of Radio Film and Television. According to the former management object is alcohol advertising, but to the latter includes only spirits commercial advertising.[38].

Table 3.

Restrictions on alcohol advertising in China.

| Content | Details |

|---|---|

| Forbidden information |

|

| Restrictions on different media |

|

4.5. Age limit for purchasing

There are a few legal provisions for underage drinking in China. The Law on the Protection of Minors stipulates: that parents have the duty to prevent the underage from being drunk; prohibition the sale of alcohol to people aged <18 years; and that the retailer must display a clear notice that prohibits the sale of alcohol to minors, the retailers will pay a relevant penalty if they violate the regulation. No one should drink in middle and primary schools, kindergarten, and other places where minors assemble. The alcohol circulation management approach prohibits the retailer selling alcohol to minors and stipulates that the retailer must display a clear notice.

4.6. Package and warning labels

The general standards for the labeling of prepackaged alcoholic beverages, fermented alcoholic, distilled spirits, blended alcoholic beverage and so on stipulates that all products will have an alcoholic concentration (ethanol content) of ≥ 0.5% by volume, which will be indicated on all product labels. The labels should convey a warning message about the product such us “Excessive drinking is harmful to your health” or “Pregnant women and young children should not be drinking”. Unpackaged alcoholic beverages are also required to conform to national food health standards.

5. A public health approach to policy

5.1. Towards a public health approach to alcohol policy

An alcohol policy is a set of approved regulations that covers alcohol marketing, consumption in public places, distribution, taxation, and underage access [39]. Babor defines an alcohol policy as set laws, regulations, and practices designed to reduce excessive alcohol use and related harm at the population level [40]. Davison et al [41] suggested that a good alcohol policy should include establishing the minimum age of the consumers, amount to be served to consumers in bars and restaurants, alcohol taxation, drink driving policies, and regulations for licensing selling, marketing, and distributing alcohol. Among theoretically linked policy groups, alcohol price restrictions were the highest-rated policies, followed by those that limited its physical availability. State alcohol excise taxes and restrictions on wholesale and retail pricing were all rated highly for both youth and the general population, whereas policies targeting the physical availability of alcohol were rated as slightly more effective for youths than for adults [42]. The WHO global strategy elaborates 10 target areas as the basic measures for reducing alcohol harm: leadership, awareness, and commitment; health services response; community action; drink-driving policies and counter measures; availability of alcohol; marketing of alcoholic beverages; pricing policies; reducing the negative consequences of drinking and alcohol intoxication; reducing the public health impact of illicit alcohol and informally produced alcohol; and monitoring and surveillance [2]. In view of the comparison between tobacco and alcohol, plus the precedent established by the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, calls for a Framework Convention on Alcohol Control are not surprising [43]. Many researches provide us with the theoretical foundation to establish a basic framework of alcohol policy.

Alcohol is closely related to public health [44], and thus deserves more consideration and recognition under current government alcohol policy. In order to improve the interdepartmental strategy and cooperation, the government should establish a cross-department coordination organization. The government should give priority to public health when making the alcohol policy and consider its integrality and direction [45]. The Chinese government should amend the current industrial policy, which encourages and supports the development of alcohol industry to strengthen the alcohol production license and quality control, reduce alcohol outlets, and improve the quality of alcoholic products to prevent low-quality alcoholic beverages. It should: strengthen taxation; regulate the production of different kinds of alcoholic beverages; raise the spirit tax; reduce alcohol density; strengthen the management of retailing [46]; prevent illegal alcohol beverages and reduce the informal alcohol; revise the Regulations of Alcohol Advertising to regulate advertising, sponsorship, and promotion, and place restrictions on the Internet and other new media [47]; make alcohol laws and set a minimum age for purchasing and drinking to reduce teenage drinking harms; provide an alcohol-free environment for minors; fully consider the impact on the environment when making policy [48,49]; reduce minors' exposure to alcohol advertising [50]; regulate the hours [51], days [52], and places [53,54] of retail sales, restricting the availability [55,56]; require all packaging to adopt mandatory clearly displayed warning labels [57]; and establish a research institution [58] to collect relevant data [59], and carry out alcohol related research. Local government should make a strategy and plan to reduce the alcohol-related problems [60].

5.2. The impediments of the Chinese alcohol policy

There may be impediments to making and implementing alcohol policies in China. First of all, the decentralized management is implemented in alcohol production and circulation. It is hard to harmonize the interests of each management department [61]. In the current alcohol management system, the Department of Agriculture is in charge of planting, the quality inspection department is responsible for production, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce monitors the market, the Department of Commerce manages distribution, the Customs Department controls import and export, the Health Department controls health indicators, and the Food Department and Drug Department care for consumption. Some areas even have a specialized alcohol management department, in addition to all levels of industry association. While defects in multiple management are reflected in two aspects, it is difficult to reach a consensus, especially where there are self interests that are indicated by the different parties betraying each other and no sector committing to take full responsibility.

The country is still in a deadlock over what kinds of alcohol management system should be adopted, which explains why the legislative activities are still unsuccessful. After the Communist regime took charge, the monopoly system was implemented nationwide, but after the process of the reform and opening up since 1978, the alcohol management system gradually loosened and even became ineffective. Since then, the alcohol monopoly or other management model has been proposed. Although it is hard to embrace the monopoly system nationwide, the debate to apply it still rages. In the absence of a clear management mode, it is difficult to adopt a national alcohol policy.

The pronounced conflict of interest at the provincial and central level in regards to policy implementation remains the main reason for failure to establish an alcohol management system and an alcohol policy. In the policy established by the National Development and Reform Commission and the State Council, the white spirit industry is under strict state restrictions, but in provinces where there is large-scale white spirit production, almost all forms of local legal legislation favor the development of alcohol industry, making it hard to achieve the original government intention of controlling spirit production.

The Chinese alcohol industry is a huge business, which has a strong impact on government policies. In recent years, the alcohol industry led the proposal for relevant legislation. Forty NPC representatives presented a proposal on the Establishment of Alcohol Law (No. 410) in 2009 [62]. The proposal was led by Jin, the chairman of Tsingtao Beer, along with Moutai Group Chairman Ji Keliang, the vice chairman of Wuliangye Group Tang Qiao, Yanjing Brewery chairman Li Fucheng, and Changyu chairman Sun Liqiang. The proposed analysis mainly catered for the interests of large alcohol business leaving out the small and medium sized enterprises, distribution field agencies and most importantly, the views of consumers and the public. Many surveys indicate that the alcohol industry plays an important role in alcohol policy [63], however, it constantly argues against the implementation of regulatory approaches that have a strong evidence base for effectiveness (such as increasing the price, reducing the availability, and restricting the marketing of alcohol) [64,65]. The alcohol industry association should be involved in the making and implementation of the alcohol policy but it has consistently shown little interest [66].

In the other legal context, some people think that China does not need an alcohol policy. In fact, China has issued the Food Safety Law, Product Quality Law, Consumer Protection Law, Trademark law, Advertisement Law, Anti-Monopoly Law, Anti-Unfair Competition Law, Circular Economy Promotion Law, and other laws. The development departmental regulations in areas such as alcohol advertising, alcohol distribution management approach, and management standards for the wholesale and retail of alcohol commodities. The implementation of the alcohol production licensing system involves the attachment of an alcohol-distribution documentation system, the provisions for food security are linked to criminal law where violation would amount to a death penalty. In view of this, China Food Industry Association officials insist that the alcohol legislation is needless.

6. Conclusion

After 1949, China's alcohol monopoly system for controlling alcohol production, consumption, and the inhibition of alcohol-related problems played an important role. After the 1980s, the government abandoned the monopoly management of alcohol, and adopted a laissez-faire policy; alcohol production is increasing rapidly, and alcohol-related problems have emerged. The government is aware that these problems must be changed, but there is still no unified management mechanism, management measures, or national alcohol law. No matter how much intentional and nationwide efforts were invested in the early 1990s by the State Council issuing the Alcohol Management Ordinance (Draft), the discussion on the restoration of the monopoly system remains a pressing matter that can easily spark endless debate justifying why there are still no remarkable achievements registered at any level in recent years. If the government wants to make progress in the management of alcohol and alcohol-related problems, complete transformation of government functions and more understanding about alcohol is paramount. Furthermore, alcohol should be regarded as a special drink instead of a kind of commodity or food. There is an urgent need to establish a good relationship among the revenue, industrial, commercial, and other government departments, the central and local governments, industry interests and public health, and so on. Embracing the local legislation and regulations is the foundation for introducing a nationwide alcohol policy accounting for alcohol production, circulation, marketing, consumption, and other aspects, and establish related management mechanism presents good prospects and a clear direction towards the public health of an alcohol policy in China.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Gan-ming Yao from the School of Humanities and Professor Wen-shui Xia from the School of Food Science and Technology at Jiangnan University for useful discussion. The authors specially thank Mr. Ndawula Junior Charles, Mr. Guang-rong Huang and Mr. Yue-shui Jiang for their assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Public-health problems caused by the harmful use of alcohol (WHA58.26) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yörük BK. Legalization of Sunday alcohol sales and alcohol consumption in the United States. Addiction. 2014;109:55–61. doi: 10.1111/add.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCambridge J, Hawkins B, Holden C. The challenge corporate lobbying poses to reducing society's alcohol problems: insights from UK evidence on minimum unit pricing. Addiction. 2014;109:199–205. doi: 10.1111/add.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chalmers J, Carragher N, Davoren S, O'Brien P. Real or perceived impediments to minimum pricing of alcohol in Australia: public opinion, the industry and the law. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24:517–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacLennan B, Kypri K, Room R, Langley J. Local government alcohol policy development: case studies in three New Zealand communities. Addiction. 2013;108:885–95. doi: 10.1111/add.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levintova M. Russian alcohol policy in the making. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2007;42:500–5. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gil A, Polikina O, Koroleva N, Leon DA, McKee M. Alcohol policy in a Russian region: a stakeholder analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20:588–94. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higuchi S, Matsushita S, Osaki Y. Drinking practices, alcohol policy and prevention programmes in Japan. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17:358–66. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parry C. Alcohol policy in South Africa: a review of policy development processes between 1994 and 2009. Addiction. 2010;105:1340–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pitso J, Obot I. Botswana alcohol policy and the presidential levy controversy. Addiction. 2011;106:898–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cochrane J, Chen HH, Conigrave K, Hao W. Alcohol use in China. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:537–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li HR. The Chinese alcoholic culture. Taiyuan: Shanxi People's Publishing House; 1995. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo X. Study on the changes of the alcohol tax system at the end of the Qing Dynasty and the early years of the Republic. Guizhou Wen Shi Cong Kan. 2011;4:25–32. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hao W, Chen HH, Su ZH. China: alcohol today. Addiction. 2005;100:737–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hao W, Young D. Drinking pattern and problems in China. J Substance Use. 2000;5:71–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang YL, Conner K, Phillips M. Alcohol use disorders and acute alcohol use preceding suicide in China. Addict Behav. 2010;35:152–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou L, Conner K, Phillips M, Caine ED, Xiao S, Zhang R, Gong Y. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse and dependence in rural Chinese men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1770–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin DH, Li XM, Yang HM, Fang X, Stanton B, Chen X, Abbey A, Liu H. Alcohol intoxication and sexual risk behaviors among rural-to-urban-migrants in China. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hao W, Derson Y, Xiao SY, Li L, Zhang Y. Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems: Chinese experience from six area samples, 1994. Addiction. 1999;94:1467–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hao W. Alcohol policy and the public good: a Chinese view. Addiction. 1995;90:1448–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demers A, Room R, Bourgault C. Surveys of drinking patterns and problems in seven developing countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hao W, Su ZH, Liu BL, Zhang K, Yang H, Chen S, Biao M, Cui C. Drinking and drinking patterns and health status in the general population of five areas of China. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:43–52. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou XH, Su ZH, Deng HQ, Xiang X, Chen H, Hao W. A comparative survey on alcohol and tobacco use in urban and rural populations in the Huaihua district of Hunan province, China. Alcohol. 2006;39:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yen ST, Yuan Y, Liu XW. Alcohol consumption by men in China: a non-Gaussian censored system approach. China Economic Review. 2009;20:162–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacFarquhar R, Fairbank J, editors. The Cambridge History of China. The People's Republic, Part 1: The emergence of revolutionary China. Vol. 14. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. pp. 1949–65. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guo X. Discussion on prohibition against alcoholic drinks: discussion with Yang Yong. Niang Jiu Ke Ji. 2012;12:126–30. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Recovery alcohol monopoly has been questioned. [accessed 20, 01,14]. Available at: http://www.foodqs.cn/news/gnspzs01/200415191536.htm.

- 31. Tang YL, Xiang XJ, Wang XY, Cubells JF, Babor TF, Hao W. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: policy changes needed. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:270–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delcher C, Maldonado-Molina MM, Wagenaar AC. Effects of alcohol taxes on alcohol-related disease mortality in New York State from 1969 to 2006. Addict Behav. 2012;37:783–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Ministry of Commerce. Management standard for alcohol commodities wholesale (SB/T103912005) The Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Ministry of Commerce. Management standard for alcohol commodities retail (SB/T103922005) The Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Ministry of Commerce. The Alcohol Circulation Management Approach (No.25) The Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The State Administration for Industry and Commerce. The Regulations of Alcohol Advertising (No.39) The State Administration for Industry and Commerce of the People's Republic of China; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang JF. Alcohol advertising in China. Asia Pacific NGO Meeting on Alcohol Policy. 2004 September; [Google Scholar]

- 38.Research Team on Rule of Law Studies in China, Law Institute, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS); Law Institute, CASS, editor. Annual report on China's rule of law (No9) Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press; 2011. Report on supervision and regulation of television advertisements; pp. 278–99. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Latimera W, Harwood E, Newcomb M, Wagenaar AC. Measuring public opinion on alcohol policy: a factor analytic study of a US probability sample. Addict Behav. 2003;28:301–13. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Babor T. Linking science to policy: the role of international collaborative research. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:66–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Davison C, Ford C, Peters P, Hawe P. Community-driven alcohol policy in Canada's northern territories 1970–2008. Health Policy. 2011;102:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nelson T, Xuan ZM, Babor T, Brewer RD, Chaloupka FJ, Gruenewald PJ, Holder H, Klitzner M, Mosher JF, Ramirez RL, Reynolds R, Toomey TL, Churchill V, Naimi TS. Efficacy and the strength of evidence of U.S. alcohol control policies. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Casswell S, Thamarangsi T. Reducing harm from alcohol: call to action. Lancet. 2009;373:2247–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, Grube JW, Hill K, Holder H, Homel R, Livingston M, Österberg E, Rehm J, Room R, Rossow I. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity: research and public policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naimi T, Blanchette J, Nelson T, Nguyen T, Oussayef N, Heeren TC, Gruenewald P, Mosher J, Xuan Z. A new scale of the U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maimon D, Browning C. Underage drinking, alcohol sales and collective efficacy: informal control and opportunity in the study of alcohol use. Soc Sci Res. 2012;41:977–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fogarty A, Chapman S. What should be done about policy on alcohol pricing and promotions? Australian experts' views of policy priorities: a qualitative interview study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:610. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rowland B, Toumbourou JW, Satyen L, Tooley G, Hall J, Livingston M, Williams J. Associations between alcohol outlet densities and adolescent alcohol consumption: a study in Australian students. Addict Behav. 2014;39:282–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Van Hoof JJ, Gosselt JF, de Jong MD. Determinants of parental support for governmental alcohol control policies. Health Policy. 2010;97:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rhoades E, Jernigan D. Risky messages in alcohol advertising, 2003–2007: results from content analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hahn RA, Kuzara JL, Elder R, Brewer R, Chattopadhyay S, Fielding J, Naimi TS, Toomey T, Middleton JC, Lawrence B. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Effectiveness of policies restricting hours of alcohol sales in preventing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:590–604. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Middleton JC, Hahn RA, Kuzara JL, Elder R, Brewer R, Chattopadhyay S, Fielding J, Naimi TS, Toomey T, Lawrence B. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Effectiveness of policies maintaining or restricting days of alcohol sales on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:575–89. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Humphreys D, Eisner M. Do flexible alcohol trading hours reduce violence? A theory-based natural experiment in alcohol policy. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Finch E. Addiction: the policy framework. Psychiatry. 2007;6:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gruenewald PJ. Regulating availability: how access to alcohol affects drinking and problems in youth and adults. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:248–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Young R, Macdonald L, Ellaway A. Associations between proximity and density of local alcohol outlets and alcohol use among Scottish adolescents. Health Place. 2013;19:124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Glock S, Krolak-Schwerdt S. Changing outcome expectancies, drinking intentions, and implicit attitudes toward alcohol: a comparison of positive expectancy-related and health-related alcohol warning labels. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2013;5:332–47. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chun S, Reid E, Sohn A, Welch ME, Yun-Welch S, Yun M. Addiction research centres and the nurturing of creativity: the Korean Institute on Alcohol Problems (KIAP) Addiction. 2013;108:675–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Humphreys D, Smith D. Alcohol licensing data: why is it an underused resource in public health? Health Place. 2013;24:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. MacLennan B, Kypri K, Langley J, Room R. Public sentiment towards alcohol and local government alcohol policies in New Zealand. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Strang J, Raistrick D. Alcohol and drug policy: why the clinician is important to public policy. Psychiatry. 2004;3:65–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chairman of Tsingtao Beer suggested Alcohol law, Moutai and Wuliangye respond jointly. [accessed 20, 01, 14]. Available at: http://business.sohu.com/20090311/n262732296.shtml.

- 63. Babor T, Hall W, Humphreys K, Miller P, Petry N, West R. Editorial: who is responsible for the public's health? The role of the alcohol industry in the WHO global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Addiction. 2013;108:2045–7. doi: 10.1111/add.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Davoren SL. Legal interventions to reduce alcohol-related cancers. Public Health. 2011;125:882–8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hawkins B, Holden C, McCambridge J. Alcohol industry influence on UK alcohol policy: a new research agenda for public health. Crit Public Health. 2012;22:297–305. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2012.658027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Munro G. Why the Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia is not a credible partner for the Australian government in making alcohol policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31:365–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]