Abstract

The aim of present study was to evaluate antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antitumor activities of methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh Euphorbia royleana. Total phenolic and flavonoid contents were estimated as gallic acid and querectin equivalents, respectively. Antioxidant activity was assessed by scavenging of free 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radicals and reduction of ferric ions, and it was observed that inhibition values increase linearly with increase in concentration of extract. The results of ferric reducing antioxidant power assay showed that hexane extract has maximum ferric reducing power (12.70 ± 0.49mggallic acid equivalents/g of plant extract). Maximum phenolic (47.47 ± 0.71 μg gallic acid equivalents/mg of plant extract) and flavonoid (63.68 ± 0.43 μg querectin equivalents/mg of plant extract) contents were also found in the hexane extract. Furthermore, we examined antimicrobial activity of the three extracts (methanol, hexane, aqueous) against a panel of microorganisms (Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtillis, Pasteurella multocida, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium solani) by disc-diffusion assay, and found the hexane extract to be the best antimicrobial agent. Hexane extract was also observed as to be most effective in a potato disc assay. As hexane extract showed potent activity in all the investigated assays, it was targeted for cytotoxic assessment. Maximum cytotoxicity (61.66%) by hexane extract was found at 800 μg/mL. It is concluded that investigated extracts have potential for isolation of antioxidant and antimicrobial compounds for the pharmaceutical industry.

Keywords: Agrobacterium tumefaciens; antioxidant; 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; Euphorbia royleana; flavonoids

1. Introduction

Plants are friends of mankind. They contribute strongly to fulfill necessities of life such as food, medicine, clothing, and construction. The World Health Organization has catalogued 20,000 plant species studied for medicinal purposes [1]. Bioactive components of plants include array of compounds (e.g., tannins, lignans, coumarins, quinones, stilbenes, xanthones, phenolic acids, flavones, flavonols, catechins, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanins) that could delay or inhibit the inception of degenerative diseases [2] and increase life expectancy. Infectious diseases are also the major cause of mortality worldwide. About 50,000 people die worldwide every day because of infectious disease. Literature surveys show that plant-based drugs play a promising role in the treatment of infectious diseases [3]. Efficacy of plant extracts against plant pathogens such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens is also well documented [4]. The bioactive compounds in plants lead to their fundamental role in modern drug development.

Euphorbia royleana is an important medicinal plant, known as Dandathor or Dozakhimeva in Pakistan. It is a spiny shrub usually up to 1.8–2.4 m tall. It is traditionally used for treatment of many ailments including paralysis, ear pain, and loose motions [5]. Its latex is documented for anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic attributes [6]. Stem bark extract of E. royleana has piscicidal and antiacetylcholinesterase activity [7]. The ethyl acetate fraction of E. royleana has immunosuppressive characteristics [8]. E. royleana belongs to the family Euphorbeaceae, different plants of which are traditionally used for the treatment of skin problems, asthma, jaundice, anemia, cough, and constipation [9]. Euphorbeaceae is scientifically reported for its antiviral [10], antimicrobial [11], anticancer [12], cytotoxic, and antitumor activities [13].

On the basis of the strong medicinal background of Euphorbiaceae, E. royleana was targeted for investigation. Although work has been done to explore some pharmacological properties of E. royleana, there is a complete gap of knowledge about the medicinal attributes of fresh E. royleana. As fresh E. royleana is used in most of traditional remedies [5], the ultimate goal of the present study was to explore antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitumor, and cytotoxic activities of fresh E. royleana.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant material

Plant material was collected from the Botanical Garden, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan. Fresh plant material was washed with distilled water and cut into cubes of 2 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm with a stainless steel knife (Global, Chiba, Japan). Cubes of fresh plant material were immediately used for extraction. Cubes of fresh plant material (20 g) were placed in a 500 mL flask, mixed with 200 mL of methanol, plugged with cotton swab, and tightly wrapped with aluminum foil. Extraction was carried out using an orbital shaker at 350 rpm for 72 hours [14], after which the suspensions was filtered using Whatman No.1 filter paper. The filtrate was evaporated at 65°C using a vacuum drying oven (Memmert GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany), maintained at 69°C for hexane and 100°C for water, to get dry extract. Solvent free extract was transferred to extract vials and stored at 4°C for further use. Similar practice for extraction was done with hexane and water solvents individually.

2.2. Chemicals

Potassium ferricyanide and agar powder were from Daejung Chemicals and Metals (Shiheung, Korea), nutrient broth was from Lab M (Bury, Lancashire, UK), and ferric chloride from BDH laboratory supplies (Lutterworth, Leicestershire, UK). Aluminum chloride hexahydrate, trichloroacetic acid, 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), gallic acid (GA), quercetin, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Methanol, hexane, and chloroform used for extraction purpose were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Folin–Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, sodium carbonate and nutrient agar were acquired from Applichem, GmbH (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.3. Total phenolic content

Total phenolics were determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu process [15,16]. Briefly, 1 mL of each extract (methanol, hexane, water) solution at concentration of 800 μg/mL was mixed with 7.5 mL of double deionized water, 500 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 1 mL of 5% Na2CO3. The mixture was incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature. After the incubation absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a spectrophotometer (Lambda EZ 201, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The content of phenolics expressed as μg GA equivalents (GAEs) per mg of extract.

| (1) |

2.4. Total flavonoid content

Total flavonoids were determined by the AlCl3 method [17,18]. A 2 mL sample of each extract (methanol, hexane, water) solution at concentration of 800 μg/mL was mixed with 2 mL of aqueous AlCl3.6H2O (0.1M). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes and absorbance was measured with the spectrophotometer at 417 nm. The content of flavonoids expressed as μg querectin equivalents (QEs):

| (2) |

2.5. DPPH assay

The free radical scavenging capability of each extract solution on DPPH radicals was determined as described previously [19]. Briefly, 4 mL of methanol solution of DPPH (0.1mM) was mixed with 1 mL of each of extract (methanol, hexane, water) solution at different concentrations (25–800 μg/mL). The reaction mixture was incubated in a dark room for 30 minutes and the free radical scavenging ability was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 515 nm with the spectrophotometer. The reaction was carried out in capped glass test tubes that were tightly wrapped with aluminum foil. The DPPH radical stock solution was freshly prepared every day for the reaction, and precautionary measures were taken to reduce the loss of free radical activity during the experiment. The inhibition percentage of DPPH radicals was calculated as:

| (3) |

where Ac is absorbance of the control reaction (all reagents except plant extract) and As is absorbance of the sample (plant extract).

2.6. Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

The ferric reducing antioxidant power assay [20] was used to assess the reducing capacities of extracts of fresh E. royleana. Different dilutions (25–800 μg/mL) of each plant extract (methanol, hexane, water) were added to 2.5 mL of phosphate buffer and 2.5 mL potassium ferricyanide (1% W/V). The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 25 minutes, after which 2.5 mL trichloroacetic acid solution was added to stop the reaction. Then 2.5 mL of this mixture was mixed with 2.5 mL of water and 500 μL of ferric chloride solution. Absorbance was measured at 700 nm after 30 minutes.

| (4) |

2.7. Antimicrobial activity

The agar disc diffusion method [21] was used for determination of diameters of inhibition zones made by methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana against various bacterial and fungal strains (Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtillis, Pasteurella multocida, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium solani). Sterile nutrient agar was inoculated with 100 μL suspension of tested bacteria and sterile potato dextrose agar was inoculated with 100 μL of tested fungi. The inoculated nutrient agar and potato dextrose agar were then poured into sterilized petri plates individually. Sterile filter discs impregnated with 50 μL of sample solution were placed in inoculated petri plates using sterile forceps. Rifampicin and terbinafine were used as positive control in bacterial and fungal inoculated plates, respectively. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and at 27°C for 48 hours for maximum bacterial and fungal growth, respectively. Antibacterial and antifungal activities were evaluated by measuring diameter (mm) of inhibition zones using a zone reader.

2.8. Antitumor assay

Antitumor activities of methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana were evaluated by the potato disc method using Vincristine sulfate as positive and DMSO as negative control [22]. A. tumefaciens from storage culture was inoculated into sterilized growth medium using aseptic techniques. The culture was vigorously shaken and then placed in a shaker for 48 hours at 28°C. Red skinned potatoes were surface sterilized in 10% sodium hypochlorite for 20 minutes and extensively washed with autoclaved distilled water and cut into 4 mm thick discs of 8 mm diameter using cork and surgical blades sterilized by γ-irradiation (2.5 MRads). Agar was prepared by dissolving agar powder in autoclaved distilled water. Agar was poured into sterilized petri plates and allowed to solidify in laminar air flow. Eight potato discs were placed on each agar plate using sterilized forceps (Rolzem International, Sialkot, Pakistan). A 50 μL sample of inoculum was placed on the surface of each disc. Plates were wrapped with parafilm and incubated at 27°C for 21 days. After 21 days, discs were stained with Lugol solution (10% KI+5% I2) for 20 minutes and tumors were counted on each disc using a dissecting microscope. Twenty-eight tumors were counted in negative control (DMSO). Percent inhibition was calculated using the formula described by Kanwal et al [4].

2.9. Brine shrimp lethality test

The brine shrimp cytotoxicity assay was performed according to a previously described method [23]. Brine shrimp (Artemianauplii) eggs were hatched in a rectangular tank (19.5 cm length × 19.5 cm width × 20.3 cm height) containing 1 L of artificial sea water [mixture of commercial salt (Harvest Co. Hong Kong) and distilled water] and subjected to continuous gentle aeration. Brine shrimp eggs were spread in the dark part of container. Mature nauplii (age 48 hours) were collected from the other half of the container that, which was exposed to continuous illumination (60 W). Methanol extract of fresh E. royleana was dissolved in water to make final concentrations of 25 ppm, 50 ppm, 100 ppm, 200 ppm, 400 ppm, and 800 ppm. A 0.5 mL aliquot of each concentration was taken in graduated vial and subjected to evaporation overnight. Twenty shrimps were added into each vial and the volume was made up to 5 mL with seawater. Vials were kept at 25°C under illumination for 24 hours. After 24 hours the number of live nauplii was counted using a 5 × magnifying glass. Median lethal dose was calculated by linear regression analysis [13].

2.10. Statistical analysis

Minitab software version 16 (Statistical software, Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA)was used to performanalysis of variance (ANOVA) and to determine significant differences (p < 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Total phenolic contents

Phenolic compounds are health benefactors because they act as antioxidative agents [19]. In the present study, the total phenolic contents of methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana were determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method and results are shown in Table 1. This method involves the reaction of phosphomolybdate and phosphotungstate with all phenolic compounds in the sample [24]. This reaction generates a blue pigment that has extensive light absorption at 760 nm [25]. Total phenolic contents of the three extracts ranged from 30.65 ± 0.46 μg GAEs/mg of plant extract to 63.68 ± 0.43 μg GAEs/mg of plant extract, with hexane extract exhibiting the highest value. A similar result for hexane extract was previously reported [26]. Phenolic contents of fresh E. royleana are not previously reported. Amount of phenolic contents in methanol extract of fresh E. royleana is higher than previously reported values of Euphorbiaceace [27].

Table 1.

Total phenolic and flavonoid contents of methanol, hexane and water extracts of fresh Euphorbia royleana.

| E. royleana extracts | Total phenolic content | Total flavonoid contents |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| (μg GAE/mg of plant extract) | (μg QE/mg of plant extract) | |

| Methanol | 56.97 ± 0.27a | 43.98 ± 0.79e |

| Hexane | 63.68 ± 0.43b | 47.47 ± 0.71d |

| Water | 30.65 ± 0.46c | 18.89 ± 0.41f |

Data are presented as mean ± SD of three individual determinations. Means with different letters in the same column indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences among the solvents used.

GAE = gallic acid equivalents; QE = querectin equivalents.

3.2. Total flavonoid contents

Flavonoids (polyphenolic plant compounds) possess a wide range of pharmacological properties. They do a lot for human health by scavenging free radicals [2]. In the present investigation, the aluminum chloride colorimetric method was used for detection of flavonoid contents. In this method, reaction of aluminum chloride with adjacent keto or hydroxyl groups of flavones or flavonols generates acid-stable complexes [28], which show maximum absorption at 415 nm. Methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana showed significant (p < 0.05) amount of flavonoid contents (Table 1). The highest amount of flavonoids was observed in hexane extract (47.47 ± 0.71 μg QE/mg of plant extract) followed by methanol (43.98 ± 0.79 μg QE/mg of plant extract) and aqueous (18.89 ± 0.41 μg QE/mg of plant extract) extracts. The flavonoid contents of fresh E. royleana extracts are not previously published, but are comparable with other medicinal flora of Pakistan [29].

3.3. DPPH assay

The antioxidant potential of methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana was evaluated on the basis of their ability to scavenge stable free DPPH radicals. This test is based on change in color of DPPH solution from purple to yellow, due to scavenging of stable free DPPH radicals [30]. A stronger yellow color indicates a greater ability of the extract to scavenge free DPPH radicals and stronger antioxidant potential. In the present study, the antioxidant potential of the three extracts was explored in a dose-dependent (25–800 μg/mL) manner as shown in Table 2. An increase in DPPH scavenging ability was observed with increase in concentration of extracts. This trend is in agreement with a previous study [19]. The DPPH scavenging ability of hexane extract (60.52 ± 0.39%) was higher than methanol extract (56.78 ± 1.37%), and least (51.64 ± 0.46%) in aqueous extract. The DPPH scavenging ability of methanol extract is in agreement with literature [31].

Table 2.

Free radical (DPPH) scavenging (%) activities of methanol, hexane and water extracts fresh Euphorbia royleana.

| Extracts | Concentration (μg/mL) | IC50 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| 25 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 800 | (mg/mL) | |

| Methanol | 18.22 ± 1.11ac | 23.46 ± 0.64bd | 28.22 ± 1.46ca | 33.51 ± 1.30df | 46.71 ± 1.25eb | 56.78 ± 1.37fe | 0.58 |

| Hexane | 16.09 ± 0.51dc | 24.89 ± 0.68fd | 31.19 ± 0.38bc | 39.38 ± 1.19ea | 50.96 ± 0.44ce | 60.52 ± 0.39af | 0.38 |

| Water | 11.18 ± 0.77ba | 17.47 ± 1.49eb | 20.18 ± 0.96ad | 25.95 ± 1.51fe | 36.68 ± 0.29cf | 51.64 ± 0.46dc | 1.13 |

Data are mean ± SD of three individual determinations. Means with different superscript letters in the same row indicate significant (p < 0.05) difference among concentrations tested. Means with different subscripts in the same column indicate significant (p < 0.05) difference among solvents used.

IC50 = half maximal inhibitory concentration.

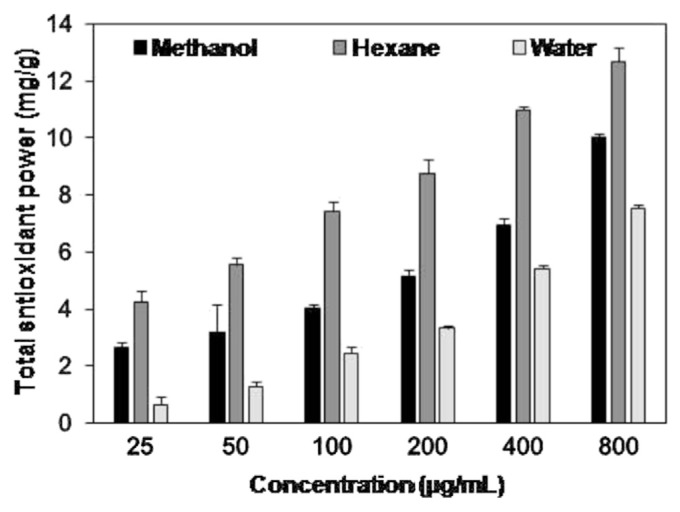

3.4. Total antioxidant activity assay

Reducing power is an important parameter for assessment of antioxidant activity. Antioxidant compounds reduce reactive radicals to stable species by donating electrons [32]. Reducing capacities of methanol, hexane and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana ranged from 0.651 ± 0.25 mg GAEs/g of plant extract to 12.70 ± 0.49 mg GAEs/g of plant extract (Fig. 1). Reducing capacity of the three investigated extracts increases with increase in concentration (25–800 μg/mL). This relation is also supported by previous studies [33]. A significant difference (p < 0.05) among reducing activities of each extract was observed at different concentrations (25–800 μg/mL). Reducing power of the hexane extract was significantly (p < 0.05) higher than of methanol and aqueous extracts. Significantly (p < 0.05) lower reducing ability was observed in aqueous extract. The reducing power of fresh E. royleana is not reported previously in the literature.

Fig. 1.

Total antioxidant power of methanol, hexane, and water extracts of fresh Euphorbia royleana. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation of three individual determinations.

3.5. Antimicrobial activity

The results of antimicrobial potential of methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana against five pathogenic microorganisms are shown in Table 3. The three investigated extracts exhibited considerable antimicrobial effects against all tested microorganisms. Methanol and hexane extracts showed the excellent activities against A. niger and with inhibition zones of 11.66 ± 0.57 mm and 14.00 ± 1.00 mm, respectively. A smaller zone of inhibition (5.67 ± 0.57 mm) was observed by methanol extract against E. coli than previously reported values of inhibition zones by methanol extracts of Euphorbia hirta, Euphorbia tricholi, and Euphorbia nurofila [11]. The highest activity of aqueous extract was observed against A. niger with inhibition zone of 9.33 ± 0.57 mm. A previous study [11] showed that methanol extract of E. hirta has inhibition a zone of 9.00 ± 0.00 mm against B. subtilis, which is smaller than our value of 10.67 ± 0.57mm by methanol extract of fresh E. royleana. In the present study, antibacterial and antifungal potential may be attributed to bioactive components present in the plant [34]. Overall, the hexane extract showed better antibacterial activities than the other two extracts.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of methanol, hexane and water extracts of fresh Euphorbia royleana.

| Tested microorganisms | Methanol | Hexane | Water | Rifampicin | Terbinafine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Diameter of inhibition zone (mm) | |||||

| Escherichia coli | 5.67 ± 0.57b | 7.00 ± 1.00b | 6.00 ± 1.00b | 21.66 ± 1.41a | — |

| Bacillus subtilis | 10.67 ± 0.57b | 12.00 ± 0.57b | 8.33 ± 0.00c | 24.66 ± 0.47a | — |

| Pasteurella multocida | 8.33 ± 0.57c | 10.33 ± 0.57c | 8.00 ± 1.00c | 23.33 ± 1.69b | — |

| Aspergillus niger | 11.66 ± 0.57c | 14.00 ± 1.00b | 9.33 ± 0.57a | — | 25.66 ± 1.69d |

| Fusarium solnai | 10.00 ± 1.00a | 10.33 ± 0.57a | 8.66 ± 0.57a | — | 24.00 ± 0.82b |

Data are mean ± SD of three individual determinations. Means with different superscript letters in the same row indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences among the solvents used.

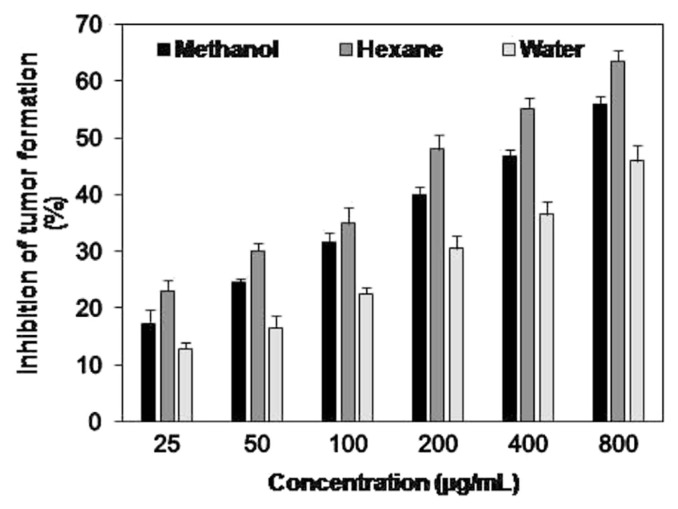

3.6. Potato disc assay

E. royleana is used for the treatment of paralysis, bladder stone, earache, inflammation, and other diseases [5], but the antitumor potential of plant has not been investigated previously. Therefore, different concentrations (25–800 μg/mL) of methanol, hexane, and aqueous extracts of fresh E. royleana were investigated by bench top potato disc assay. The results (Fig. 2) indicate that percent tumor inhibition increase with increases in concentration of plant extracts. A similar relation between percent tumor inhibition and concentration of plant extract was previously reported [4]. Maximum tumor inhibition was investigated in hexane extract (63.49 ± 1.81%) followed by methanol (56.01 ± 1.34%) and aqueous (45.87 ± 2.71%) extracts. The effect of concentration on tumor inhibition was statistically significant (p < 0.01), and the results reveal that the three investigated extracts have considerable antitumor activity.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of tumor formation by methanol, hexane and water extracts of fresh Euphorbia royleana. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation of three individual determinations.

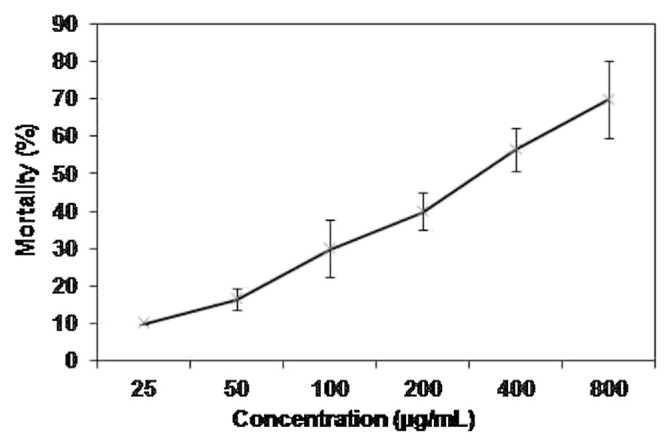

3.7. Brine shrimp lethality test

The brine shrimp lethality test is a potent, precise, and economical method for assessment of cytotoxic, phototoxic, pesticidal, and many other activities [35]. In the present study, the brine shrimp lethality test was used to assess cytotoxic potential of hexane extract of fresh E. royleana. The results obtained are shown in Fig. 3. Minimum and maximum mortality (6.66% and 61.66%) was found at 25 ppm and 800 ppm, respectively. These values are lower than previously reported values of percent mortality for E. hirta, E. heterophylla, and E. neriifolia [12]. Median lethal dose (598.8 μg/mL) of hexane extract of fresh E. royleana is in comparison with other medicinal flora of Pakistan [36].

Fig. 3.

Cytotoxic activity of hexane extract of fresh Euphorbia royleana. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation of three individual determinations.

4. Conclusion

The present study was carried out to explore antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitumor, and cytotoxic potential of methanol, hexane, and water extracts of E. royleana. Maximum antioxidant and antitumor activities were observed for hexane extract, which might be correlated to its leading phenolic and flavonoid contents as compared to its methanolic and aqueous counterparts. Significant difference (p < 0.05) in antimicrobial activity was noted in all of the investigated extracts. On the basis of our pharmacological findings (antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitumor) of hexane extract, it was selected to assess cytotoxic activity. In future, work will be done to isolate bioactive constituents of fresh E. royleana extract to locate potential pharmacological agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Higher Education Commission, Pakistan for financial and Central Hi-Tech Laboratory, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad staff for technical and logistic support.

Funding Statement

The authors are thankful to Higher Education Commission, Pakistan for financial and Central Hi-Tech Laboratory, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad staff for technical and logistic support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gulluce M, Aslan A, Sokmen M, et al. Screening the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the lichens Pamelia saxatilis, Platismatia glauca, Ramalina pollinaria, Ramalina polymorpha and Umbilicaria nylanderiana. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:515–21. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robards K, Paul DP, Greg T, et al. Phenolic compounds and their role in oxidative processes in fruits. Food Chem. 1999;66:401–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmad I, Beg AZ. Antimicrobial and phytochemical studies on 45 Indian medicinal plants against multi-drug resistant human pathogens. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;74:113–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kanwal S, Ullah N, Haq IL, et al. Antioxidant, antitumor activities and phytochemical investigation of Hedera nepalensis K. Koch, an important medicinal plant from Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2011;43:85–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sabeen M, Ahmad SS. Exploring the folk medicinal flora of Abbotabad city, Pakistan. Ethnobot Leaflets. 2009;13:810–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bani S, Kaul A, Jaggi BS, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of the hydrosoluble fraction of Euphorbia royleana latex. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:655–62. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tiwari S, Singh A. Effect of Oleandrin on a freshwater air breathing murrel, Channa punctatus. Ind J Exp Biol. 2004;42:419–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bani S, Kaul A, Khan B, et al. Immunosuppressive properties of ethyl acetate fraction from Euphorbia royleana. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hussain K, Nisar MF, Majeed A, et al. Ethnomedicinal survey for important plants of JalalpurJattan district Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. Ethnobot Leaflets. 2010;14L:807–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng WF, Cui Z, Zhu Q. Cytotoxicity and antiviral activity of the compounds from Euphorbia kansui. Planta Med. 1998;64:754–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chanda S, Baravalia Y. Screening of some plant extracts against some skin diseases caused by oxidative stress and microorganisms. Afr J Biotech. 2010;9:3210–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galvez J, Zarzuelo A, Crespo ME, et al. Antidiarrhoeic activity of Euphorbia hirta extract and isolation of an active flavonoid constituent. Planta Med. 1993;59:333–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patil SB, Magdum CS. Determination of LC50 values of extracts of Euphorbia hirta Linn and Euphorbia nerifolia Linn using brine shrimp lethality assay. Asian J Res Pharm. 2011;1:42–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shofian NM, Hamid AA, Osman A, et al. Effect of freeze-drying on the antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activity of selected tropical fruits. Intern J Mole Scien. 2011;12:4678–92. doi: 10.3390/ijms12074678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jagadish LK, Krishnan VV, Shenbhagaraman R, et al. Comparative study on the antioxidant, anticancer and antimicrobial property of Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach before and after boiling. Afr J Biotech. 2009;8:654–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Slinkard K, Singleton VL. Total phenol analysis: automation and comparison with manual methods. Am J Enol Viticul. 1997;28:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quettier-Deleu C, Gressier B, Vasseur J, et al. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of buckwheat (Fagospyrum esculentum Moench) hulls and flour. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamaison JL, Carnat A. Levels of principal flavonoids in flowers and leaves of Crataegus-Monogyna Jacq and Crataegus-Laevigata (Poiret) Dc (Rosaceae) Pharma Acta Helv. 1990;65:315–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Öztürk H, Kolak U, Meric C. Antioxidant, anticholinesterase and antibacterial activities of Jurinea consanguinea DC. Rec Nat Prod. 2011;5:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan EWC, Lim YY, Omar M. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of leaves of Etlingera species (Zingiberaceae) in Peninsular Malaysia. Food Chem. 2007;104:1586–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCCLS (National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards) Performance standards for antimicrobial disc susceptibility test. Approved Standard. 6th ed. Wayne, PA: NCCLS; 1997. pp. M2–A6. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mclaughlin JL, Rogers LL, Anderson JE. The use of biological assays to evaluate botanicals. Drug Info J. 1998;32:513–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meyer BN, Ferrigni NR, Putnam JE, et al. Brine shrimp; a convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Med. 1982;45:31–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramirez-Sanchez I, Maya L, Ceballos G, et al. Flourescent detection of (−)-epicatechin in microsamples from cacao seeds and cocoa products: comparison with Folin–Ciocalteu method. J Food Compost Anal. 2011;23:790–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schofield P, Mbugua DM, Pell AN. Analysis of condensed tannins: a review. Anim Feed Sci Techol. 2001;91:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aris SRS, Mustafa S, Ahmat N, et al. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of fruits of Ficus deltoidea var.angustifolia sp. Malay J Anal Sci. 2009;13:146–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shahwar D, Rehman SU, Ahmad N, et al. Antioxidant activities of selected plants from the family Euphorbiaceae, Lauraceae, Malvaceae and Balsaminaceae. Afr J Biotech. 2010;9:1086–96. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang CC, Yang MH, Wen HM, et al. Estimation of total flavonoid contents in propils by two complementary colorimetric methods. J Food Drug Anal. 2002;3:178–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naz R, Bano A. Phytochemical screening, antioxidants and antimicrobial potential of Lantana camara in different solvents. Asia Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3:480–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khadri A, Neffati M, Smiti S, et al. Antioxidant, antiacetylcholinesterase and antimicrobial activities of Cymbopogon schoenanthus L. Spreng (lemon grass) from Tunisia. Food Sci Technol. 2010;43:331–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Priyanka C, Kadam DA, Kadam AS, et al. Free radical scavenging (DPPH) and ferric reducing ability (FRAP) of some Gymenosperm species. Int J Res Bot. 2013;3:34–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ksouri R, Megdiche W, Falleh H, et al. Influence of biological, environmental and technical factors on phenolic content and antioxidant activities of Tunisian halophytes. C R Biol. 2008;331:865–75. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Koksal E, Bursal E, Dikici E, et al. Antioxidant activity of Melissa officinalis leaves. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5:217–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cowan MM. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:564–82. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ahmad B, Azam S, Bashir S, et al. Insecticidal, brine shrimp cytotoxicity, antifungal and nitric oxide free radical scavenging activities of the aerial parts of Myrsine africana L. Afr J Biotech. 2011;10:1448–53. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haq I-U, Mannan A, Ahmed I, et al. Antibacterial activity and brine shrimp toxicity of Artemisia dubia extract. Pak J Bot. 2012;44:1487–90. [Google Scholar]