Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is caused by a head impact with a force exceeding regular exposure from normal body movement which the brain normally can accommodate. People affected include, but are not restricted to, sport athletes in American football, ice hockey, boxing as well as military personnel. Both single and repetitive exposures may affect the brain acutely and can lead to chronic neurodegenerative changes including chronic traumatic encephalopathy associated with the development of dementia. The changes in the brain following TBI include neuroinflammation, white matter lesions, and axonal damage as well as hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau protein. Even though the human brain gross anatomy is different from rodents implicating different energy transfer upon impact, especially rotational forces, animal models of TBI are important tools to investigate the changes that occur upon TBI at molecular and cellular levels. Importantly, such models may help to increase the knowledge of how the pathologies develop, including the spreading of tau pathologies, and how to diagnose the severity of the TBI in the clinic. In addition, animal models are helpful in the development of novel biomarkers and can also be used to test potential disease-modifying compounds in a preclinical setting.

Keywords: animal models, axonal damage, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, neuroinflammation, tau, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

While single traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the human may certainly cause acute damage to the brain, repetitive mild TBI may as well lead to damages and a chronic disease stage, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). CTE is a neurodegenerative disease associated with contact sport participation and repetitive head impacts. Since TBI is the underlying cause of CTE, it is important to increase the knowledge and awareness of the severe consequences, for example, contact sport participation can lead to. Clinically, symptoms manifest many years after a period of exposure [1] and consist of irritability, impulsivity, aggression, depression, short-term memory loss and heightened suicidality. As the disease advances, symptoms become more severe and include dementia, gait and speech abnormalities and parkinsonism [2,3]. The clinical syndrome was first described in boxers in 1928 [4] and called dementia pugilistica or ‘punch drunk syndrome’. It was later associated pathologically with a tau pathology distinct from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [5], and eventually, the nomenclature of CTE was adopted to underscore the diverse aetiologies beyond boxing. Currently, CTE is a neuropathological diagnosis that can only be definitively diagnosed at autopsy. The pathology of CTE is distinct and involves the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) within brain regions that correspond to the symptomatology [6].

Many sports have now been linked to an increasing risk of developing CTE, including boxing, American football, ice hockey, soccer and wrestling. In fact, former National Football League (NFL) players over 50 years old are five times more likely to have dementia than the national average for men in that age group [7]. Out of a group of former football players who have died and donated their brains to research, the percentage of players who have pathologically confirmed CTE is remarkably high (>87%) with the frequency increasing from high school to college to professional player [8]. While many players had a history of repeated concussions, some did not, suggesting that repeated subconcussive blows to the head may also induce this disease. Moreover, CTE has been documented in military personnel exposed to an explosive blast injury [9]. Thus, the hundreds of thousands of soldiers that have suffered brain trauma from conventional and improvised explosive devices in wars including those in Iraq and Afghanistan [10] may be at risk of developing CTE.

Affecting millions of individuals worldwide each year, concussion is now recognized as a major health concern. While this disorder is alternatively referred to as ‘mild traumatic brain injury’ (mTBI), the term is somewhat of a misnomer for the approximately 20% of individuals who suffer persisting neurocognitive dysfunction [11,12]. Emerging evidence from this group of individuals suggests that they suffered permanent brain damage that selectively affects brain networks. This selective type of injury appears to be unique to concussion, most likely springing from the initial biomechanical events.

The role of repeated concussions in the development of CTE, including the epidemiology and the link between neuropathological characteristics and its clinical manifestations, is poorly understood. There are numerous potential underlying mechanisms of concussion that could trigger progressive neuropathological changes. Indeed, the term ‘concussion’ is used only to describe clinical symptoms after blunt impacts and not as an indicator of pathophysiological changes in the brain. Nonetheless, there is a large body of work that provides insight into the acute pathological mechanisms of concussion that may contribute to progressive neurodegeneration.

Accumulating evidence suggests an altered neuroinflammatory state may persist for many years following a period of repetitive head impacts [13]. Within a group of former American football players, the cellular density of CD68 immunoreactivity, a marker that labels phagocytic/activated microglia, was significantly increased in subjects with a history of football participation with or without CTE, when compared to noncontact sport athlete controls. Consistent with increased density of CD68 immunoreactive cells, microglia also exhibited a phenotypic change [14]. In addition, a simultaneous equation regression model analysis demonstrated that number of years of American football play was significantly associated with both increased activated microglia cell density (CD68) and with increased tau pathology, as detected with an anti-pTau antibody, AT8, frequently used to detect neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in AD, both directly and indirectly through increased density of activated microglia. This increased density of activated microglia was a significant predictor of dementia via increased tau neurofibrillary tangle pathology [14].

Overall, the association in human brain between neuroinflammation and tau pathology in CTE is also supported by mouse models demonstrating possible mechanistic links [15,16]. Indeed, these models can play a role in studying well-defined aspects of head injury. However, it is incumbent upon the research community to continually return to the human pathology in order to ensure the relevance of any particular model system. It is clear from decades of experience with AD animal models that the spectrum of human pathology is not easily replicated in a single model. It will likely be more fruitful to tailor specific models to defined aspects of disease to systematically build an understanding of pathogenesis.

Human pathology of CTE

The gross findings in CTE include atrophy of the cerebral and medial temporal lobes, ventriculomegaly, and cavum and fenestrated septum pellucidum. Microscopically, it is a tauopathy with numerous tau-positive NFTs throughout the neocortex, thalamus, brainstem, and occasionally, spinal cord. Consensus criteria for the neuropathological diagnosis of CTE have established CTE as a distinct tauopathy defined by abnormal p-tau accumulation within neurons in an irregular and patchy distribution that is perivascular and concentrated within the depths of sulci [17]. Although tau-positive astrocytes, including thorn-shaped astrocytes, may be present, the presence of neuronal tau distinguishes CTE from age-related tau astrogliopathy [18]. In addition, there is a significant TDP-43 proteinopathy that occurs in many of the same regions as the tauopathy [19,20]. Many cases are associated with amyloid b-peptide (Aβ) deposition [21]; however, the distribution of abnormal tau is distinct from that seen in AD [19,22].

The spectrum of tau pathology within CTE suggests stages of disease severity that increase with age and years of contact sport participation [6,14,19]. The pathology appears to begin in a focal and patchy distribution within neocortical sulcal depths, most often in superior and dorsolateral frontal cortex, but later extending to include multiple patchy foci within temporal and parietal cortices. In later stages of disease, NFTs extend to involve the frontal, temporal, parietal and insular cortices, with greatest severity at the depths of the sulci, as well as medial temporal lobe structures, diencephalon, brainstem and spinal cord. In severe disease, tau pathology affects widespread brain regions including white matter with increasing neuronal loss and gliosis, increasing glial tau pathology and axonal loss. These stages of CTE tau pathology correlate with age, clinical symptoms, duration of contact sports or repetitive head impact exposure, and length of survival after exposure. Notably, the progression of tauopathy in CTE is distinct from that of AD where the tau pathology begins in the brainstem, progresses to the medial temporal lobe, and only in the later stages involves the neocortex [23]. In addition to taupathy, increased Lewy Body Disease pathology is observed in CTE in subjects of contact sports [24].

While the whole brain undergoes dynamic tissue deformation at all levels of TBI, the white matter is at greatest risk of damage, possibly due to its highly organized, highly directional anisotropic structure. In particular, axon tracts have been shown to suffer selective damage in several unique ways due to a viscoelastic response at the cellular level [25,26]. The resulting diffuse axonal injury (DAI) has long been identified as common neuropathological feature of higher levels of TBI where post-mortem histopathological analyses have been possible. More recently, human and animal studies using advanced imaging alongside animal histopathology examinations have also implicated DAI as a key pathological substrate of concussion [27–30].

Diffuse axonal injury includes multiple pathophysiological changes

Under normal daily mechanical loading conditions, axons can easily stretch to at least twice their resting length and relax back unharmed to their prestretch straight geometry [31]. However, under dynamic loading with rapid stretch, the axonal cytoskeleton can physically break, evidenced by an undulating appearance upon relaxation immediately afterwards. These axonal undulations have been observed in an in vitro model of dynamic stretch injury of axons, in preclinical TBI models and in human TBI [26,31,32].

Microtubule breaking

Electron microscopic analysis demonstrated that microtubules, representing the stiffest components of the axon, display clear break points after trauma, typically at the apex of the undulations [31]. The break sites along the microtubule lattice are thought to impede sliding and relaxation of the axon, thereby causing the undulating appearance. With breaking and subsequent depolymerization of the axonal microtubules after trauma, transport is interrupted at periodic locations, resulting in varicose swellings along the injured axon [27,32].

Role of tau in axonal trauma

Computational modelling of traumatic axonal injury has recently identified tau as a potential viscoelastic spring underlying microtubule breaking [33,34]. Tau crosslinks and stabilizes the parallel arrangement of microtubules along the axon. As the axon is stretched under normal loading conditions, adjacent microtubules slide past each other, stretching the stabilizing tau, which must unfold from their resting conformation. This extension includes the sequential breaking of hydrogen bonds along tau. However, under dynamic stretching of axons at the rates predicted for concussion, too many hydrogen bonds must release at the same time. This causes sufficient mechanical strain at the microtubule binding sites to rupture the microtubules [33,34].

Axonal transport interruption after trauma

While axons themselves rarely disconnect at the time of trauma, large swellings from transport interruption can cause a secondary disconnection of axons [27,28]. There is a broad range in the rate and morphology of axonal swellings identified with undulated axons, varicose swellings and disconnected axonal bulbs.

The gold standard for post-mortem clinical diagnosis of these types of DAI is immunohistochemistry using anti-amyloid precursor protein (APP) antibodies, which can identify axonal swellings in white matter within hours of injury [27]. Although APP+ swollen axonal profiles are indicative of DAI, the vast majority of axons in white matter tracts appear relatively normal after TBI, even in severe cases [27,35]. TBI must therefore involve injury beyond axon transport interruption and swelling.

Ionic and metabolic challenges after axonal trauma

Axonal trauma can also induce an immediate change in ion concentrations, which affect network function, proteolysis and metabolism [28,36–38]. In vitro analyses demonstrate that at the time of axonal trauma, sodium channels become non-inactivated, meaning that sodium influx into the axons is not blocked by the inactivation gate. This results in the inability or reduced capacity to generate action potentials, affecting network function. It is thought that this may be reflected in the common concussion symptoms, including decreased processing speed and memory dysfunction [27]. With the overload of sodium in axons after injury, sodium–calcium exchangers are reversed and the high-voltage state maintains opening of calcium channels. This causes progressive increases in intra-axonal calcium concentrations [38], which, in turn, can activate calcium-dependent proteases causing further damage to the axonal structure [36,39,40]. In addition, axonal mitochondria sequester the calcium in an attempt to reduce the cytosolic concentration, but the process can cause a decreased capacity to generate ATP. In many if not most axons, these structural and chemical changes appear to be reversible over time after concussion as may be reflected by the recovery of cognitive function. However, in other axons, these processes appear to trigger progressive pathological processes that can last for years after injury.

Progressive axonal pathology and accumulation of tau and Aβ

While there may be many pathological processes that contribute to TBI-induced progressive neurodegeneration, DAI is certainly a key suspect [27,41–43]. Curiously, tau protein and APP, the parent protein of Aβ, are normally most abundant in axons [44–47]. Therefore, it has been suggested that axonopathy in concussion may lead to the aberrant production and/or aggregation of tau and Aβ [42,48]. Indeed, in severe TBI axon degeneration and white matter atrophy have been found to progress for years after injury [27] and advanced neuroimaging changes in white matter connectivity have been observed long after concussion. Furthermore, tau accumulations in neurons and glia are the most frequently described pathologies of CTE following repeated concussions and Aβ pathologies are also commonly observed. Seeing that tau is an axonal protein, its phosphorylation and aggregation may in some ways reflect chronic axonopathy. With regards to amyloid pathologies, notably, in humans and animal models, Aβ was found to be produced within the axonal membrane compartment after TBI providing a plausible link with the rapid and progressive formation of Aβ plaques [41–43,48].

Inflammation in acute brain injury

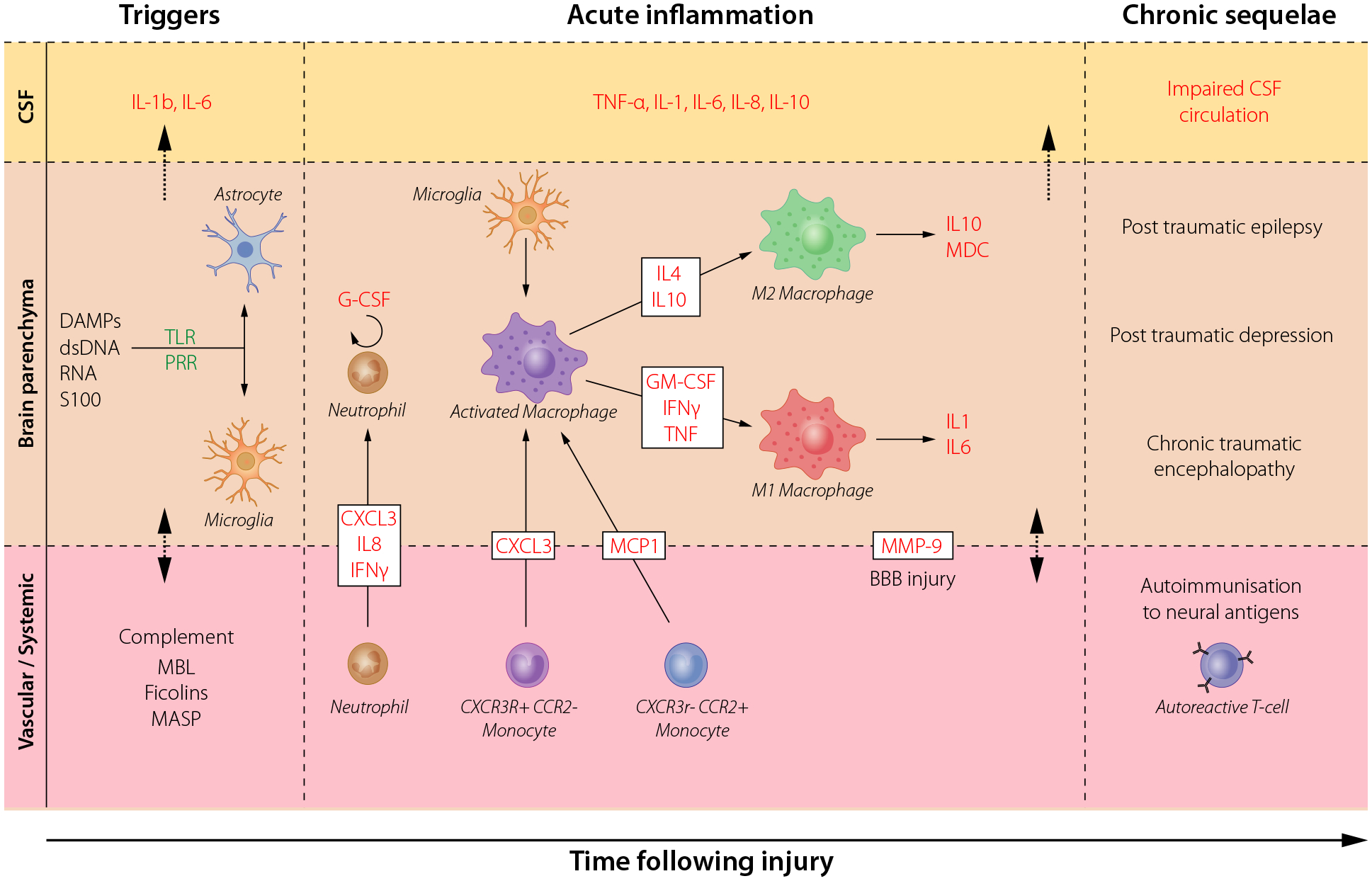

The inflammatory response to acute brain injury is primarily driven by the innate immune system; however, there is also an increasing knowledge regarding the role of the adaptive immune system. Immediately after trauma, there is a release of alarmins and a damage-associated molecular pattern including host DNA which triggers an inflammatory response, primarily considered as pro-inflammatory in the early stages (minutes to days) of brain injury [49]. Inflammasome activation takes place after the immediate reaction, with subsequent cellular (macrophages, granulocytes) response hours to days after injury [49]. A week after injury increased migration of monocytes and lymphocytes takes place, resulting in an adaptive/anti-inflammatory-like response. The pro-inflammatory response seen early after injury is generally considered to have both negative (e.g. increased influx of fluid and cells through the blood–brain barrier (BBB), increased excitotoxicity and production of neurotoxic factors) and positive (e.g. clearing up debris and dead cells, promoting neurogenesis and production of neurotrophic factors) effects [50]. Presumably, if this immediate reaction was reduced, damaging effects of the remaining tissue debris or nonfunctioning cells could cause problems such as epilepsy, neoplasia or infections. However, it is generally agreed within the research field that the host response is often too excessive, killing healthy cells in the process as the central nervous system CNS recovers from injury [51]. Microglia, residing in the CNS, are key players in traumatic inflammatory reactions being able to rapidly release cytokines in order to promote an inflammatory response and having the capacity to phagocyte cells (Fig. 1). Traditionally, microglia act either in a pro-inflammatory way (‘classical activation’, M1) or in a more adaptive, anti-inflammatory fashion (‘alternative activation’, M2) [52]. However, this polarity is currently under debate as this classification might be too biased and lack adequate granularity [53]. Interestingly, astrocytes may also show a similar duality depending on exposure to pro-inflammatory conditions (A1) as compared to nonstimulated cells (A2) [54]. In animal models, the flexibility of microglia- and astrocyte-activation also seems to depend of the age of the host, as older hosts present a less flexible, pro-inflammatory response [55,56]. Moreover, in in vitro models, neurons have been shown to exhibit a downstream cytokine response when exposed to a milieu mimicking the aftermath of TBI [57]. In summary, the inflammatory response is driven by several different cells in the CNS, as well from migrating inflammatory cells from the periphery.

Fig. 1.

Acute and chronic neuroinflammatory responses in brain injury. The cellular and molecular sequelae and inflammatory cascades in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), brain parenchyma and in the vascular system that occur upon traumatic brain injury (TBI). Danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) including double-stranded (ds)DNA, RNA and proteins such as S100B are early triggers to resident cells, caused by the tissue injury that leads to subsequent humoral and cellular cascades. These lead to an increasingly cytotoxic environment which stimulates immunocompetent cells in the CNS (microglia and astrocytes), and recruites peripheral monocytes, through pattern recognition receptors (PRR) including toll-like receptors (TLR). The secretion of cytokines, chemokines and other chemotactic substances (including complement proteins), attract neutrophils and monocytes to the brain parenchyma through the increasingly permeable blood–brain barrier (BBB). The release of cytokines also initiates a long-term inflammatory process, which includes a shift of macrophages and microglial canonical phenotype from M1 (classical activation) to M2 (alternative activation, presumably the result of antigen presenting cells migrating into the brain from the periphery). This results in chronic inflammation and auto-immunization towards brain-enriched antigens. Key cytokines are highlighted in red. MBL; mannose-binding lectin, MASP; mannose-associated serine protease, MMP-9; Matrix MetalloProteinase 9. Adopted from Thelin et al. [62].

The adaptive immune response is less studied in TBI but does play a role in modulating the inflammatory response [58]. One of the key aspects for the adaptive response is the T-cell mediated auto-immunity towards brain-enriched proteins. It has been shown that S100B, glial fibrillary acidic protein and myelin basic protein auto-antibodies increase after TBI and that circulating levels have been associated with both tissue- and functional outcome [59–61]. However, the true role of auto-immunity in TBI is not fully understood.

Clinically, after TBI different aspects of the inflammatory response are monitored, mainly by assessing markers of inflammation in different body fluids and sometimes tissue [62]. By detecting cytokine profiles in blood, which is easily accessible, it is possible to both separate healthy individuals from patients with radiological visible injury [63], and predict outcome months after injury [64]. However, detection of inflammatory markers in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is often more specific for brain injuries as compared to blood. Increases of many predominantly pro-inflammatory cytokines in CSF have been associated with outcome [65]. By using microdialysis to analyse brain extracellular fluid, it has been determined that many cytokines are produced locally in brain after injury and that several cytokines exhibit distinct temporal patterns [66]. Thus, the neuroinflammatory markers could be potential biomarkers of TBI. Brain biopsies, mainly from autopsies or selective severe TBI cases, may also be used to study the inflammatory response. Histochemical analysis of brains from injured patients has shown that many components of the innate immune systems are present close to lesions, including complement activation [67]. It is also possible to noninvasively monitor CNS inflammation following TBI by using positron emission tomography, where microglial ligands ([PK]11195) reveal activity up to a year after injury [68].

The neuroinflammatory response following TBI has been shown to be involved in a number of neurological complications seen in the aftermath of the trauma [69]. These sequelae include, among others, depression [70], seizures [71] and amnesia [72]. Biopsy studies have revealed that microglial activation persists especially in white matter tracts many years after TBI. Such microglial activation is associated with axonal pathology and NFTs and tau pathology [14,73], hence linking neuroinflammation to what is seen in CTE. The glymphatic system, a proposed drainage system for cerebral proteins [74], has been shown to be affected following TBI disturbing the clearance of Aβ and tau and may play an important role in the link between neuroinflammation and dementia development following TBI [75].

Due to the many tentative inflammatory processes being involved in the underlying pathophysiology of TBI, several different inflammatory modulating therapies have been tested [76]. Some of the more notable trials in TBI include corticosteroids (CRASH) [77] and progesterone (ProTECT III) [78]; however, none of these studies showed clinical efficacy and the active treatment have been shown to be more harmful than placebo in some subgroups. One explanation as to why many studies have failed is that TBI was regarded as a homogenous disease, not taking into account which type of intracranial pathology the patients suffered from. Presumably, some types of more diffuse lesions and patients with more oedema and BBB disruption would benefit from anti-inflammatory therapy, while patients with extradural- or subdural haematomas would benefit from rapid evacuation surgery. Moreover, many pharmacological studies focus primarily on clinical outcome and not pharmacokinetic endpoints or indications of supposed biological effects that the drug is supposed to have. Further, even when anti-inflammatory drugs are administered, they have been shown to have a more pro- than anti-inflammatory effect [79]. Therefore, it is important to expand our knowledge about the properties of the inflammatory response in TBI in order to design better trials in the future.

In summary, the inflammatory response plays a major role in the underlying pathophysiology in both acute and chronic TBI. It has both detrimental and beneficial properties and activates CNS resident cells as well as inflammatory cells from the systemic circulation. Further development of biomarkers targeting the inflammatory response will likely be crucial for monitoring the clinical and pathological sequelae of TBI during life. Thus far, no anti-inflammatory trials in human TBI have shown an improvement in outcome, but lessons learned from previous trials will allow us to better tailor and design future studies. Improved understanding of the pathobiology of TBI will be crucial for the development of both diagnostics and eventual therapeutic agents.

Animal models for TBI

TBI in animal models and humans

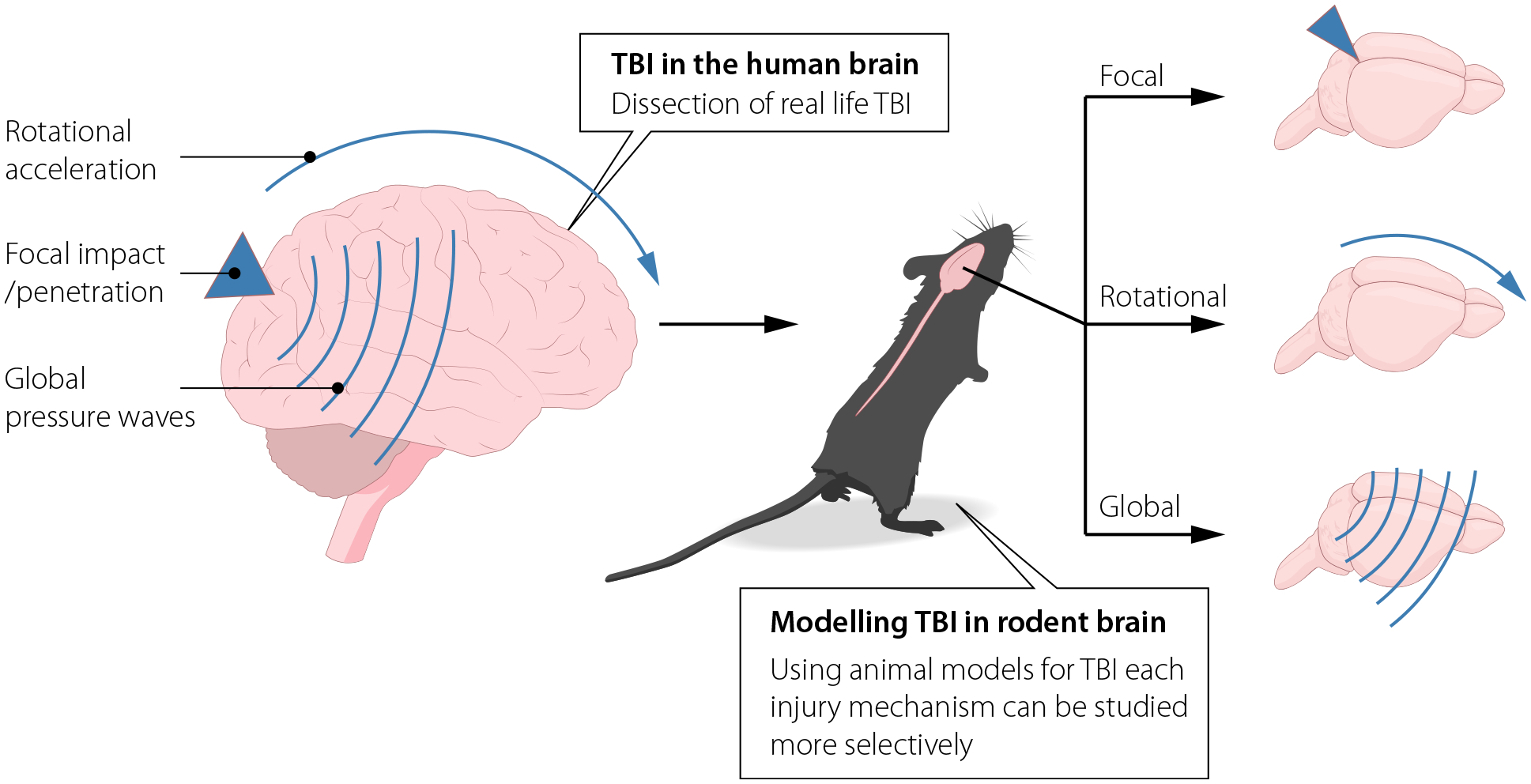

Physical impact leading to TBI results in a rapid transfer of energy to the brain. This energy dissipation is complicated to analyse in terms of duration and direction [80]. Secondary impacts and rotational acceleration generate complex situations that are drastically dissimilar from case to case (Fig. 2). The injury results in immediate injuries (primary TBI) and also usually delayed injuries (secondary TBI). Due to its size, the human brain is particularly vulnerable to the mechanical forces imparted during head impacts. During normal daily activities, the brain can endure substantial tissue deformation and return back to its resting shape unharmed. However, due to its viscoelastic nature, brain tissue acts stiffer under the very rapid or dynamic deformations resulting from rotational accelerations triggered by head impacts. Decades ago, it was established that due to the exceptional size of the human brain, mass effects caused high shear, tensile and compressive strains as different brain regions dynamically pulled and pushed one another.

Fig. 2.

Real-life severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) induced by road traffic accidents or weapons is a complex mixture of injury mechanisms, such as impact and rotational forces. Animal models can be used to study these mechanisms more separately, with better control of physical parameters.

Animal models represent important and useful tools for systematic research on TBI and can provide precise control of the physical parameters in the impact. In addition, animal experiments allow for better control of genetics and age. It is also possible to have baseline data and control for timetables for the evaluation of the outcome of the experiment. This type of detailed control in the experimental situation can generate useful data even from a relatively small number of observations. Experimental studies have, for example, pointed out that rotational acceleration is an important mechanism for white matter injuries. However, it can be difficult to translate results from experimental studies on TBI in rodents to clinical situation, due to differences in anatomy and physiology. Accordingly, animal modelling of concussion has been challenging since the rotational acceleration forces have to be substantially scaled up to create the same tissue deformation in much small-brained animals as occur in human concussion [28,30,37,81]. Experimental studies that have suggested candidates for pharmacological treatment of TBI have been difficult to reproduce in the clinical situations. It has also been noted that results from experimental studies can be difficult to repeat in other animal experiments. Some recent publications have presented guidelines [82,83] for experimental studies in order to reduce confounding factors and facilitate the translation between different experiments and to clinical situations.

Concussion or mild TBI

The majority of TBI cases is mild and referred to as concussions or mild TBI, whereas the majority of the experimental studies have focused on a more severe TBI. Thus, we do not have much detailed information about mechanisms, injury thresholds, pathology or pathophysiology in mild TBI. The current definition of concussion includes any transient neurological symptoms following a head impact [84]. Thus, concussion may, but does not need to, include a transient loss of consciousness (LOC). There might also be a period of nausea/vomiting, confusion, memory loss. In many patients, there is a period of persistent symptoms that can include headache, vision disturbance, light sensitivity, difficulty to concentrate and sleep disturbance. Such outcomes can be difficult to evaluate in a direct way in experimental animals. For example, to evaluate LOC in anesthetized animals would be difficult in any experimental setup. Furthermore, in the context of chronic sequelae, such as CTE, the relatively short life span in rodents may be a limiting factor. Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that there are not many good validated animal models for concussion available. One classical mechanism for concussion is an impact that results in a rotational acceleration/deceleration of the head. Thus, animal models that can induce such movements of head and subsequent transient functional changes, for example, in memory function, could be suggested as useful for studies on mild TBI. One such example is the graded rotational TBI model for rats [85] and in mild TBI induced by rotational forces which causes axonal injury in swine [81]. This results in white matter injuries, without focal contusions, and a transient decrease in both reference and working memory. In addition, there is a release of injury biomarkers such as tau and neurofilament light into the blood. Such models can provide suggestions for pathological changes, injury thresholds and relevant biomarkers. However, there are several limitations in such models. One is that the amount of acceleration, that is needed to produce this type of mild TBI in rodent is very high, due to the small size of the rodent brain. The distance between the axis of rotation and the site of injury is so critical that this model is applicable in large rats, but not in mice where acceleration needed would create injuries in the skull and other tissues. One other limitation in rodent models for concussion is that the rodent cerebrum lacks the gyri and sulci that are present in the human brain. There are several indications that the gyri and sulci complicate the energy distribution during rotational injuries and the large mass of the human brain makes it particularly vulnerable. Computational modelling suggests the greatest strain following a head collusion occur within the sulcal depth [86]. It is noteworthy that tau accumulation in CTE is usually observed in the same region, namely within the cortical sulci and along the convexities of the brain [6]. It may be suggested that the sulci of the rodent cerebellum could provide a possibility to compensate for that, but this needs to be verified. Nevertheless, the initiating events involving damage to the BBB, axonal injury and the brain’s inflammatory response are likely conserved across organisms.

Thus, the classical mechanism for mild TBI seems to involve rotational acceleration, but many studies indicate additional mechanisms. One of these is blast waves from detonations of road bombs or pressure waves from large guns. There are a number of experimental models for blast [87]. It is usually difficult to completely avoid acceleration effects in blast, but these can be monitored during experiments. There are numerous ongoing experimental studies with a focus on blast-induced mild TBI and many of these evaluate the effect of repeated exposure [9]. For example, mood changes can be one important outcome of concussion. Studies using a model for mild blast in rats have shown that there are changes in the levels of monoamine transmitters and galanin in the brain [88]. Several studies suggest a link between the function of the monoamine systems and the progression of dementia [89]. Therefore, these acute changes may partially underlie a more chronic dysfunction.

What would be the relevant outcomes to look for in animal models for concussion? Although one study in unanesthetized mice used LOC as an outcome [90], LOC cannot be reliably accessed in anesthetized animals. However, EEG might be used to evaluate correlates to LOC. Headache and vomiting would also be difficult to access in rodents. Sleep pattern changes and anxiety could be relevant parameters to investigate. Biomarkers of the injury, including brain tissue markers such as S100B, neurofilament light and tau should be relevant to monitor, both in serum and CSF.

Strengths of animal models in TBI research:

Precise control of physical parameters during trauma

Trauma can be ‘dissected’ to focus on particular physical mechanisms, for example, rotational acceleration

Possibility to control age and genetics (including gender)

Possibility to monitor post-traumatically development of pathologies with exact timetables for evaluation and possibility to include baseline data

Disadvantages of animal models in TBI research:

Differences in gross anatomy as compared to humans (e.g. lack of gyri/sulci)

Differences in the physiology and timewise progression of pathology as compared to humans

Few models for concussion available

Difficult to translate outcome parameters for concussion between rodents and humans

TBI-induced tau pathologies modelled in animals

Estimated 5–10% of dementia in the community is thought to be TBI associated [91]. Interestingly, young TBI patients whom are unlikely to show other risk factors for dementia show higher risk of dementia compared to aged patients, when stratified by time since TBI [92]. There is increasing evidence that for some individuals, TBI might not only be an acute and self-limiting event but rather triggers a chronic, sometimes life-long disease process [93]. This highlights the need to understand the determinants driving the transitions from a biomechanical injury to late neurodegeneration.

There is experimental evidence that a single severe TBI in mice induces long term and progressive neuropathology at up to 1 year after injury [94–96] supporting the feasibility of using rodent models to model the long-term pathobiology of human TBI. The controlled cortical impact model was first described in the early nineties [97,98] and has been validated in several experiments and laboratories worldwide with more than 1150 indexed publications. It replicates both the mechanical forces and the main secondary injury processes observed in patients with traumatic brain contusion and, importantly, is associated with clinically relevant behavioural and histopathological outcomes. While it has been used widely for short-term observations, and it is thought of as a focal injury model, recent investigations of the neuropathological changes occurring up to several months after injury provide evidence of long-term evolution of brain damage with bilateral involvement and distributed white matter injury like in human TBI [99]. As discussed in the above paragraphs, elevated tau levels have been found in the brain of severe TBI patients as a consequence of acute axonal damage [100] and widespread deposition of p-tau can be detected in autoptic brain specimens many years after TBI [48] suggesting that axonal injury-associated tau pathology may be a key contributor to late neurodegeneration after TBI. Tau pathology has been shown to occur in rodent models within 2 weeks from TBI [9,101–105]. This has mainly been reported in transgenic mice, which are genetically generated to develop tau pathology (typically 3xTg-AD and TauP301L mice) [101–104]. Kondo et al. first demonstrated aggregation of endogenous tau in wild-type mice reporting an increase in the fraction of sarcosyl-insoluble tau at 6 months post-TBI [106,107]. Furthermore, they found that an antibody against p-tau was able to attenuate the progression of tau pathology and reduce functional and structural damage in TBI mice [107]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain tau pathomechanisms (reviewed in [108]). In AD, tau pathology appears to progress along neural networks, suggesting transcellular spread of tau via neural connections [109]. In vivo studies have described AD-related tau protein spreading from local sites to distant regions of the brain [110,111] and it has been suggested that tau aggregates – or seeds – serve as this agent of spread, transmitting the aggregated state from cell to cell in a prion-like manner [112]. Prions are proteinaceous infectious agents consisting of misfolded prion protein (PrP), which propagate by imposing their abnormal structure on native PrP molecules [113]. Recent data demonstrate that tau in the context of TBI also shows prion-like properties. Single severe TBI in wild-type mice induces a self-propagating tau pathology that progressively spreads in the brain from the site of injury to remote brain regions and can be horizontally transmitted to naïve mice by intracerebral inoculation causing synaptic degeneration in the hippocampus and memory deficits [114] (Fig. 3). The observation that severe TBI in mice recapitulates a p-tau pathology reminiscent of post-TBI pathology in humans and which has ‘prion-like’ properties suggests a mechanism by which a biomechanical insult may predispose to chronic neurological deterioration. Understanding the relationship between TBI-induced tau spreading and the development of late evolving pathologies such as CTE, is of utmost importance, since modulation of this process – that lasts for years after injury – offers a large therapeutic window within which an effective intervention could improve outcome.

Fig. 3.

Cartoon showing the emergence, propagation and transmissibility of tau pathology after a single severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) by controlled cortical impact in wild-type mice. Hyperphosphorylated tau (in brown) was detected only in the pericontusional area at 3 months, but was widespread 1 year after injury. Brain homogenates from 12-month TBI mice, when inoculated into the hippocampus and overlying cortex of naive mice, induced persistent memory deficits and widespread tau pathology [114].

Conclusions

Traumatic brain injury causes enormous suffer to a large number of people in today’s society; however, no treatment is yet available. Great research efforts have unravelled some of the disease mechanism which can be permanent damages to the brain and eventually lead to dementia. The pathologies include neuroinflammation, axonal damages, hyperphosphorylation of tau and in some cases Aβ depositions. Modelling the pathologies in animal models has emerged as an important tool to further understand the disease mechanisms. Challenges include the differences between the human brain and rodent brain anatomy and how the forces of the impact in human TBI can be simulated. However, novel experimental designs have overcome some of the challenges and offer the possibility to better control the various forces of the impact. These models have enabled the recapitulation of the white matter degeneration observed in human brains and very importantly the pronounced tau pathology which seems to behave in a prion-like manner.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful for the financial support from Gamla Tjänarinnor and Journal of Internal Medicine to the TBI symposium held at Nobel Forum, Karolinska Institutet, May 24–25 2018. We also acknowledge the following financial support; M.R. is supported by Swedish Armed Forces R&D; E.Z. by the Alzheimer Association (AARG-18-532633), M.A. by Swedish Research Council, Alzheimerfonden and Hjärnfonden; PN by Hållstens forskn-ingsstiftelse, Swedish Research Council, Alzheimerfonden.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stein TD, Alvarez VE, McKee AC. Concussion in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2015; 19: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montenigro PH, Baugh CM, Daneshvar DH et al. Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014; 6: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montenigro PH, Corp DT, Stein TD, Cantu RC, Stern RA. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: historical origins and current perspective. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2015; 11: 309–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martland HS. Punch drunk. J Am Med Assoc 1928; 91: 1103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corsellis JAN, Bruton CJ, Freeman-Browne D. The aftermath of boxing1. Psychol Med 1973; 3: 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein TD, Alvarez VE, McKee AC. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a spectrum of neuropathological changes following repetitive brain trauma in athletes and military personnel. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014; 6: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weir D, Jackson JF. National Football League Player Care Foundation: Study of Retired NFL Players. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT et al. Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. JAMA 2017; 318: 360–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 134ra60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanten G, Xiaoqi L, Alyssa I et al. Updating memory after mild traumatic brain injury and orthopedic injuries. J Neurotrauma. 2013; 30: 618–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCauley SR 1, Wilde EA, Barnes A et al. Patterns of early emotional and neuropsychological sequelae after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014; 31: 914–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD. The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2014; 127: 29–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherry JD, Tripodis Y, Alvarez VE et al. Microglial neuroinflammation contributes to tau accumulation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2016; 4: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh S, Wu MD, Shaftel SS et al. Sustained interleukin-1 overexpression exacerbates tau pathology despite reduced amyloid burden in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 5053–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maphis N, Xu G, Kokiko-Cochran ON et al. Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain 2015; 138: 1738–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW et al. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2015; 131: 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs GG, Ferrer I, Grinberg LT et al. Aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG): harmonized evaluation strategy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2016; 131: 87–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 2013; 136: 43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King A, Sweeney F, Bodi I, Troakes C, Maekawa S, Al-Sarraj S. Abnormal TDP-43 expression is identified in the neocortex in cases of dementia pugilistica, but is mainly confined to the limbic system when identified in high and moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathology 2010; 30: 408–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein TD, Montenigro PH, Alvarez VE et al. Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2015; 130: 21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009; 68: 709–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2011; 70: 960–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams JW, Alvarez VE, Mez J et al. Lewy body pathology and chronic traumatic encephalopathy associated with contact sports. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018; 77: 757–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meaney DF, Smith DH. Cellular biomechanics of central nervous system injury. Traumatic Brain Injury, Part I. In: Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier, 2015; 105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith DH, Wolf JA, Lusardi TA, Lee VMY, Meaney DF. High tolerance and delayed elastic response of cultured axons to dynamic stretch injury. J Neurosci 1999; 19: 4263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 2013; 246: 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DH, Meaney DF. Axonal damage in traumatic brain injury. Neuroscientist 2000; 6: 483–95. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith DH, Hicks R, Povlishock JT. Therapy development for diffuse axonal injury. J Neurotrauma 2013; 30: 307–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meaney DF, Smith DH. Biomechanics of concussion. Clin Sports Med 2011; 30: 19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang-Schomer MD, Patel AR, Baas PW, Smith DH. Mechanical breaking of microtubules in axons during dynamic stretch injury underlies delayed elasticity, microtubule disassembly, and axon degeneration. FASEB J 2010; 24: 1401–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang-Schomer MD, Johnson VE, Baas PW, Stewart W, Smith DH. Partial interruption of axonal transport due to microtubule breakage accounts for the formation of periodic varicosities after traumatic axonal injury. Exp Neurol 2012; 233: 364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmadzadeh H, Smith Douglas H, Shenoy Vivek B. Viscoelasticity of tau proteins leads to strain rate-dependent breaking of microtubules during axonal stretch injury: predictions from a mathematical model. Biophys J 2014; 106: 1123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmadzadeh H, Freedman BR, Connizzo BK, Soslowsky LJ, Shenoy VB. Micromechanical poroelastic finite element and shear-lag models of tendon predict large strain dependent Poisson’s ratios and fluid expulsion under tensile loading. Acta Biomater 2015; 22: 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith DH, Uryu K, Saatman KE, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK. Protein accumulation in traumatic brain injury. Neuro-Mol Med 2003; 4: 59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwata A, Stys PK, Wolf J et al. Traumatic axonal injury induces proteolytic cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channels modulated by tetrodotoxin and protease inhibitors. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 4605–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith DH, Meaney DF, Shull WH. Diffuse axonal injury in head trauma. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2003; 18: 307–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf JA, Stys PK, Lusardi T, Meaney D, Smith DH. Traumatic axonal injury induces calcium influx modulated by tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels. J Neurosci 2001; 21: 1923–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Reyn CR, Mott RE, Siman R, Smith DH, Meaney DF. Mechanisms of calpain mediated proteolysis of voltage gated sodium channel α-subunits following in vitro dynamic stretch injury. J Neurochem 2012; 121: 793–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuen TJ, Browne KD, Iwata A, Smith DH. Sodium channelopathy induced by mild axonal trauma worsens outcome after a repeat injury. J Neurosci Res 2009; 87: 3620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hay J, Johnson VE, Smith DH, Stewart W. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: the neuropathological legacy of traumatic brain injury. Annu Rev Pathol 2016; 11: 21–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Traumatic brain injury and amyloid-β pathology: a link to Alzheimer’s disease? Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11: 361–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DH, Johnson VE, Stewart W. Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: substrates of dementia? Nat Rev Neurol 2013; 9: 211–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen X-H, Siman R, Iwata A, Meaney DF, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH. Long-term accumulation of amyloid-β, β-secretase, presenilin-1, and caspase-3 in damaged axons following brain trauma. Am J Pathol 2004; 165: 357–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Graham DI, Stewart JE, Praestgaard AH, Smith DH. A neprilysin polymorphism and amyloid-β plaques after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2009; 26: 1197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith DH, Chen X-H, Iwata A, Graham DI. Amyloid β accumulation in axons after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg 2003; 98: 1072–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uryu K, Chen X-H, Martinez D et al. Multiple proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases accumulate in axons after brain trauma in humans. Exp Neurol 2007; 208: 185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Widespread τ and amyloid-β pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol 2012; 22: 142–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gadani SP, Walsh JT, Lukens JR, Kipnis J. Dealing with danger in the CNS: the response of the immune system to injury. Neuron 2015; 87: 47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morganti-Kossmann MC, Rancan M, Stahel PF, Kossmann T. Inflammatory response in acute traumatic brain injury: a double-edged sword. Curr Opin Crit Care 2002; 8: 101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown GC, Neher JJ. Microglial phagocytosis of live neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014; 15: 209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol 2000; 164: 6166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ransohoff RM. A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nat Neurosci 2016; 19: 987–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017; 541: 481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke LE, Liddelow SA, Chakraborty C, Munch AE, Heiman M, Barres BA. Normal aging induces A1-like astrocyte reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115: E1896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar A, Stoica BA, Sabirzhanov B, Burns MP, Faden AI, Loane DJ. Traumatic brain injury in aged animals increases lesion size and chronically alters microglial/macrophage classical and alternative activation states. Neurobiol Aging 2013; 34: 1397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thelin EP, Hall CE, Gupta K et al. Elucidating pro-inflammatory cytokine responses after traumatic brain injury in a human stem cell model. J Neurotrauma 2018; 35: 341–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nizamutdinov D, Shapiro LA. Overview of traumatic brain injury: an immunological context. Brain Sci 2017; 7: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marchi N, Bazarian JJ, Puvenna V et al. Consequences of repeated blood-brain barrier disruption in football players. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e56805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cox AL, Coles AJ, Nortje J et al. An investigation of auto-reactivity after head injury. J Neuroimmunol 2006; 174: 180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang KK, Yang Z, Yue JK et al. Plasma anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein autoantibody levels during the acute and chronic phases of traumatic brain injury: a transforming research and clinical knowledge in traumatic brain injury pilot study. J Neurotrauma 2016; 33: 1270–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thelin EP, Tajsic T, Zeiler FA et al. Monitoring the neuroinflammatory response following acute brain injury. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lagerstedt L, Egea-Guerrero JJ, Rodriguez-Rodriguez A et al. Early measurement of interleukin-10 predicts the absence of CT scan lesions in mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2018; 13: e0193278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar RG, Boles JA, Wagner AK. Chronic inflammation after severe traumatic brain injury: characterization and associations with outcome at 6 and 12 months postinjury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015; 30: 369–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeiler FA, Thelin EP, Czosnyka M, Hutchinson PJ, Menon DK, Helmy A. Cerebrospinal fluid and microdialysis cytokines in severe traumatic brain injury: a scoping systematic review. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Helmy A, Carpenter KL, Menon DK, Pickard JD, Hutchinson PJ. The cytokine response to human traumatic brain injury: temporal profiles and evidence for cerebral parenchymal production. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 658–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bellander BM, Singhrao SK, Ohlsson M, Mattsson P, Svensson M. Complement activation in the human brain after traumatic head injury. J Neurotrauma 2001; 18: 1295–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramlackhansingh AF, Brooks DJ, Greenwood RJ et al. Inflammation after trauma: microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol 2011; 70: 374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sankowski R, Mader S, Valdes-Ferrer SI. Systemic inflammation and the brain: novel roles of genetic, molecular, and environmental cues as drivers of neurodegeneration. Front Cell Neurosci 2015; 9: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Juengst SB, Kumar RG, Failla MD, Goyal A, Wagner AK. Acute inflammatory biomarker profiles predict depression risk following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015; 30: 207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Webster KM, Sun M, Crack P, O’Brien TJ, Shultz SR, Semple BD. Inflammation in epileptogenesis after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 2017; 14: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Collins-Praino LE, Corrigan F. Does neuroinflammation drive the relationship between tau hyperphosphorylation and dementia development following traumatic brain injury? Brain Behav Immun 2017; 60: 369–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 2013; 136: 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 147ra11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iliff JJ, Chen MJ, Plog BA et al. Impairment of glymphatic pathway function promotes tau pathology after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci 2014; 34: 16180–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hellewell S, Semple BD, Morganti-Kossmann MC. Therapies negating neuroinflammation after brain trauma. Brain Res 2016; 1640: 36–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P et al. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 1321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wright DW, Yeatts SD, Silbergleit R et al. Very early administration of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 2457–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Helmy A, Guilfoyle MR, Carpenter KL, Pickard JD, Menon DK, Hutchinson PJ. Recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist promotes M1 microglia biased cytokines and chemokines following human traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1434–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson RWG, McLean AJ. Head injury. In: Reilly PL, Bullock R, eds. Biomechanics of Closed Head Injury, 2nd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Browne KD, Chen X-H, Meaney DF, Smith DH. Mild traumatic brain injury and diffuse axonal injury in swine. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 1747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith DH, Hicks RR, Johnson VE et al. Pre-clinical traumatic brain injury common data elements: toward a common language across laboratories. J Neurotrauma 2015; 32: 1725–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Watts S, Kirkman E, Bieler D et al. Guidelines for using animal models in blast injury research. J R Army Med Corps 2019; 165: 38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davidsson J, Risling M. A new model to produce sagittal plane rotational induced diffuse axonal injuries. Front Neurol 2011; 2: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ghajari M, Hellyer PJ, Sharp DJ. Computational modelling of traumatic brain injury predicts the location of chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology. Brain 2017; 140: 333–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Risling M, Plantman S, Angeria M et al. Mechanisms of blast induced brain injuries, experimental studies in rats. NeuroImage 2011; 54: S89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kawa L, Arborelius UP, Yoshitake T et al. Neurotransmitter systems in a mild blast traumatic brain injury model: catecholamines and serotonin. J Neurotrauma 2015; 32: 1190–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vermeiren Y, De Deyn PP. Targeting the norepinephrinergic system in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders: the locus coeruleus story. Neurochem Int 2017; 102: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tagge CA, Fisher AM, Minaeva OV et al. Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model. Brain 2018; 141: 422–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shively S, Scher AI, Perl DP, Diaz-Arrastia R. Dementia resulting from traumatic brain injury: what is the pathology? Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 1245–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fann JR, Ribe AR, Pedersen HS et al. Long-term risk of dementia among people with traumatic brain injury in Denmark: a population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wilson L, Stewart W, Dams-O’Connor K et al. The chronic and evolving neurological consequences of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 813–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dixon CE, Kochanek PM, Yan HQ et al. One-year study of spatial memory performance, brain morphology, and cholinergic markers after moderate controlled cortical impact in rats. J Neurotrauma 1999; 16: 109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Loane DJ, Kumar A, Stoica BA, Cabatbat R, Faden AI. Progressive neurodegeneration after experimental brain trauma: association with chronic microglial activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2014; 73: 14–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Smith GDP, Saldanha G, Britton TC, Brown P. Neurological manifestations of coeliac disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 63: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dixon CE, Clifton GL, Lighthall JW, Yaghmai AA, Hayes RL. A controlled cortical impact model of traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurosci Methods 1991; 39: 253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Smith DH, Soares HD, Pierce JS et al. A model of parasagittal controlled cortical impact in the mouse: cognitive and histopathologic effects. J Neurotrauma 1995; 12: 169–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pischiutta F, Micotti E, Hay JR et al. Single severe traumatic brain injury produces progressive pathology with ongoing contralateral white matter damage one year after injury. Exp Neurol 2018; 300: 167–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Magnoni S, Esparza TJ, Conte V et al. Tau elevations in the brain extracellular space correlate with reduced amyloid-b levels and predict adverse clinical outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain 2012; 135: 1268–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yoshiyama Y, Uryu K, Higuchi M et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary tangle formation, cerebral atrophy, and cognitive deficits induced by repetitive mild brain injury in a transgenic tauopathy mouse model. J Neurotrauma 2005; 22: 1134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tran HT, LaFerla FM, Holtzman DM, Brody DL. Controlled cortical impact traumatic brain injury in 3xTg-AD mice causes acute intra-axonal amyloid-beta accumulation and independently accelerates the development of tau abnormalities. J Neurosci 2011; 31: 9513–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tran HT, Sanchez L, Esparza TJ, Brody DL. Distinct temporal and anatomical distributions of amyloid-beta and tau abnormalities following controlled cortical impact in transgenic mice. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e25475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tran HT, Sanchez L, Brody DL. Inhibition of JNK by a peptide inhibitor reduces traumatic brain injury-induced tauopathy in transgenic mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012; 71: 116–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hawkins BE, Krishnamurthy S, Castillo-Carranza DL et al. Rapid accumulation of endogenous tau oligomers in a rat model of traumatic brain injury: possible link between traumatic brain injury and sporadic tauopathies. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 17042–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Albayram O, Kondo A, Mannix R et al. Cis P-tau is induced in clinical and preclinical brain injury and contributes to post-injury sequelae. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kondo A, Shahpasand K, Mannix R et al. Antibody against early driver of neurodegeneration cis P-tau blocks brain injury and tauopathy. Nature 2015; 523: 431–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li C, Götz J. Tau-based therapies in neurodegeneration: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 2017; 16: 863–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Goedert M The ordered assembly of tau is the gain-of-toxic function that causes human tauopathies. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 12: 1040–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ahmed Z, Cooper J, Murray TK et al. A novel in vivo model of tau propagation with rapid and progressive neurofibrillary tangle pathology: the pattern of spread is determined by connectivity, not proximity. Acta Neuropathol 2014; 127: 667–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sanders DW, Kaufman SK, DeVos SL et al. Distinct tau prion strains propagate in cells and mice and define different tauopathies. Neuron 2014; 82: 1271–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Prusiner SB. Cell biology. A unifying role for prions in neurodegenerative diseases. Science (New York, NY) 2012; 336: 1511–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982; 216: 136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zanier ER, Bertani I, Sammali E et al. Induction of a transmissible tau pathology by traumatic brain injury. Brain 2018; 141: 2685–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]