Abstract

In the present work, two novel complexes of zinc(II) and copper(II) were synthesized from the ligand 2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinoline-3-carbaldehyde (H2L) in a 1:2 metal-to-ligand ratio in methanol. The complexes were characterized by UV–visible spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy-energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), mass spectrometry (MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) experimental techniques and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The spectral data revealed that the mono-deprotonated (HL) ligand acted as a bidentate ligand, which bound to both Zn(II) and Cu(II) ions via the nitrogen atom of the amine (N–H) and the hydroxyl (O–H) groups through the deprotonated oxygen atom. Formation constants and thermal analysis indicated that both metal complexes are stable up to 100 °C with thermodynamically favored chemical reactions. The Cu(II) complex showed antibacterial activities with the zones of inhibition of 20.90 ± 2.00 mm against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 19.69 ± 0.71 mm against Staphylococcus aureus, and 18.58 ± 1.04 mm against Streptococcus pyogenes. These results are relatively higher compared with the Zn(II) complex at the same concentration. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results for the complexes also showed similar trends against the three bacteria. On the other hand, radical scavenging activities of both Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes showed half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 4.72 and 8.2 μg/mL, respectively, while ascorbic acid (a positive control) has a value of 4.28 μg/mL. The Cu(II) complex exhibited better communication with the positive control, indicating its potential use for biological activities. The calculated and in silico molecular docking results also strongly support the experimental results.

1. Introduction

Microbial drug resistance has become a serious medical problem, causing morbidity and mortality, which has attracted the attention of different researchers working on the discovery of antimicrobial drugs.1 Therefore, there are reports of extensive drug discovery studies being carried out elsewhere to develop new therapeutic approaches and effective drugs with a wide range of antimicrobial activities toward biological targets.2−4 In this aspect, quinoline is among the most important nitrogen-containing heterocyclic molecules being used for the synthesis of biologically active molecules.5,6 It plays a vital role in biochemical processes as a pharmaceutical agent with its skeleton being often used for the design of many synthetic compounds having diverse pharmacological properties.5−9 Quinoline derivatives are also being used for antiprotozoal, antifungal,9 anticancer,8 antiviral,7 antioxidant, and antibacterial5,6,9 activities.

On the other hand, transition-metal complexes are being used in pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry since the discovery of cisplatin.10 Several coordination compounds of metal ions (chromium, cobalt, copper, manganese, molybdenum, palladium, ruthenium, tungsten, vanadium, and zinc) have been applied in the treatment of various diseases owing to their antimicrobial and antioxidant,11−16 anticancer,10,17 antiproliferative,17,18 anti-inflammatory,19 DNA binding and cytotoxicity,11,14,20,21 antitumor,22 and antidiabetic23 activities. Studies also indicated that Zn(II) complexes exhibit anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic,23 antioxidant,24 and antimicrobial activities,16,25 whereas Cu(II) complexes exhibited promising antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiviral, DNA binding,2,20,26 and antiproliferative18 activities. Previous studies of a zinc(II) complex of quinoline derivative ligand indicated an in vitro biological screening effect tested against four bacterial strains, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative) as well as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis (Gram-positive). The results showed a moderate antibacterial activity compared with the free ligand due to chelation.27 Another study also indicated that the zinc(II) complex of a quinoline derivative showed antibacterial activity against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus.28 Similarly, copper(II) complexes of quinoline derivatives also showed moderate antibacterial activity against E. coli(29) but showed higher antibacterial activities than the parent ligand.15 The efficiencies of metal complexes having biological activities depend on the nature of both metal ions and the ligands that the complexes are made from. Accordingly, metal complexes synthesized from single ligands with different metal ions exhibited different biological properties.11,20,30 In recent years, antioxidant activity and possible antibacterial activity of metal complexes with quinoline derivatives have been reported.11,14,20,21,30,31

The synthesis of transition-metal complexes with a detailed study of biological activities remains to be an open area of research. In addition to these, understanding the mode of drug action and the efficiency of therapeutic agents with the aid of DFT calculations and molecular docking studies is also a hot topic of research.11,21,30−32 These observations aroused our interest in the synthesis of new transition-metal compounds from a single ligand that possesses antimicrobial and antioxidant activities.5,6 In relation to this, we recently investigated and reported the coordinating ability of quinoline derivative ligand complexed with Zn(II), Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II), and V(IV) metal ions and evaluated their biological activities.13 This work introduces new Zn(II) and Cu(II) metal complexes with new quinoline derivative ligand 2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinoline-3-carbaldehyde. In addition, we studied the binding stoichiometry, formation constants, antimicrobial activities, and antioxidant activities using spectroscopy, disk diffusion, and DPPH assay methods. The result analyses were supported using quantum mechanical and molecular docking approaches. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out for a better understanding of the electronic properties of the complexes.3,33,34

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

The chemicals and solvents used in this study were aniline, acetic anhydride, acetic acid, phosphorous oxychloride, ethanolamine, acetone, sulfuric acid, potassium dichromate, methanol, triethylamine, zinc chloride, copper(II) nitrate trihydrate, DMSO, and DPPH. All chemicals were purchased from Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd. (Mumbai, India) and were reagent grade.

2.2. Characterization Methods

The IR spectra of the compounds were recorded using a PerkinElmer spectrophotometer using the potassium bromide pellet technique. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded using a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz instrument in d6-DMSO using TMS as an internal reference. Mass spectra were recorded using a SHIMADZU LC-MS (8030). The UV–visible data were recorded using an SM-1600 spectrophotometer, and fluorescence spectra measurements were performed on an Agilent: MY-18490002/PC spectrofluorophotometer. The analysis of morphology and elemental composition was carried out with energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and FESEM-EDX spectroscopy (CARL ZE 155, Oxford Instruments EDX); powder X-ray diffraction data were recorded on an X-ray diffractometer at diffraction angles in the 2θ° range of 5–80°, and the analysis was performed using Cu Kα1 radiation with a λ of 1.5406 Å.35 Conductivity was measured using an electrical conductometer (AD8000), and melting point was measured using capillary tubes with a digital melting point. Data of thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were recorded under an inert atmosphere of nitrogen (N2, 20 mL/min) using detectors with a DTG-60H Shimadzu thermal analyzer at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and the mass loss was evaluated at a temperature range of 25–800 °C. The spectroscopically determined formation constants were recorded with UV–vis absorbance.

2.3. Synthesis of the Ligand (H2L)

The ligand was synthesized based on reported procedures with minor modifications.5 The precursor ligand (5 g, 0.019 mol), [(E)-2-(((2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinolin-3-yl)methylene) amino)ethanol], was refluxed in 20% H2SO4 (10 mL) for 2 h. The success of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography. Once the reaction was completed, the resulting product was cooled down to room temperature and then put into 200 mL of ice-cold water, and then the precipitate was filtered and washed with 100 mL of ice-cold water.5,6

The ligand (H2L), [2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinoline-3-carbaldehyde], has the formula C12H12N2O2 and is obtained with a yield of 3.50 g, 85% in the form of a yellow powder. Composition: Calc. for C12H12N2O2: C, 66.65; H, 5.59; N, 12.96; and O, 14.80%. Found: C, 66.70; H, 5.80; N, 12.91; and O, 14.59%. UV–vis λmax (methanol) = 408 nm; FT-IR (υ cm–1, KBr (pellet)): 3361 ν(O–H), 3245 ν(N–H), 1679 ν(carbonyl C=O), 1618 ν(quinoline C=N). The NMR analysis is presented in the supplementary information (SI) (Figures S1–S3).

2.4. Synthesis of Zinc(II) and Copper(II) Complexes

Both Zn(HL)2 and Cu(HL)2(H2O)2 complexes of the quinoline derivative were prepared by mixing a drop of triethylamine with a hot methanolic solution of the ligand (H2L) (0.5 g, 2.3 mmol, 20 mL) in a 250 mL two-neck round-bottom flask. After 40 min of continuous stirring at room temperature, a methanolic solution (20 mL, 1.15 mmol) of ZnCl2 (0.157g) and Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (0.278 g) were added dropwise to the starting solution and mixed with continuous stirring and refluxed for 4 h at 80 °C. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was cooled down to room temperature and washed repeatedly using ice-cold absolute methanol to remove unreacted starting materials and then dried in vacuum over anhydrous calcium chloride in a desiccator.2,3,33,34,36,37

2.4.1. Zinc(II) Complex (1)

The Zn(II) complex has a molecular formula [Zn(HL)2] and is yellowish-white in color, nonhygroscopic, and an amorphous powder; yield: 72% (0.41 g). Composition: Calc. for C24H22N4O4Zn: C, 58.14; H, 4.47; N, 11.30; O, 12.91; and Zn, 13.19%. Found: C, 58.27; H, 4.41; N, 11.08; O, 12.84; and Zn, 13.40%. FT-IR (υ cm–1, KBr (pellet)): 1642 ν(Imin C=O), 1622 ν(quin C=N), 758 ν(Zn–O), 529 ν(Zn–N). UV–vis (MeOH, nm): 231 and 259 (π → π*), 303 and 393 (n → π*).

2.4.2. Copper(II) Complex (2)

The Cu(II) complex has a molecular formula Cu(HL)2(H2O)2 and is deep-green in color, nonhygroscopic, and an amorphous powder; yield: 64% (0.39 g). Composition: Calc. for C24H26CuN4O6: C, 54.38; H, 4.94; N, 10.57; O, 18.11; and Cu, 11.99%. Found: C, 54.55; H, 4.95; N, 10.35; O, 18.09; and Cu, 12.06%. FT-IR (υ cm–1, KBr (pellet)): 1646 ν(C=O), 1562 ν(quinol C=N), 607 ν(Cu–O), 544 ν(Cu–N). UV–vis (nm): 255 (n → π*) and 351(LMCT).

2.5. Pharmacological Studies

2.5.1. Antimicrobial Activity

Antibacterial activity of the newly synthesized Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes was evaluated using the disk diffusion method against Gram-positive S. aureus (ATCC25923) and Streptococcus pyogenes (ATCC19615) and Gram-negative Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) bacteria strains by adopting previously reported media preparation methods.5,6,13,38−40 The bacterial strains were screened against two sample concentrations (100 and 200 μg/mL) in DMSO using ciprofloxacin as a reference with the same concentrations. The bacterial growths were recorded by measuring the zones of inhibition.

In addition to the disk diffusion method, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for the investigated complexes were determined by the agar dilution assay method against all of the bacterial strains as previously reported.11,14 Bacterial suspension was prepared by inoculating nutrient broth with a loopful of the bacterial culture from the slant and incubated at 37 ± 1 °C for 24 h. A few mL of the above bacterial suspensions (24-h broth cultures) of each strain was added to 20 mL of fresh broth until the final inoculum concentration was approximately 5 × 105 CFU/mL, and a 2-fold serial dilution method was followed.15,41−43

Complexes 1 and 2 were dissolved in water separately to a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL solution. A 0.2 mL solution of the complex was added to 1.8 mL of the seeded broth to form the first dilution in each case (250 μg/mL concentration). Then, 10 various dilutions were prepared for each complex by diluting 1 mL of this dilution with a further 1 mL of the seeded broth to produce the second dilution. The process was repeated until the 10th dilution, generating concentrations of 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25, 15.63, 7.81, 3.91, 1.95, 0.98, and 0.49 μg/mL. A positive control was prepared using ciprofloxacin in the same concentration as the complexes against all of the four bacterial strains. A set of tubes containing only seeded broth and a suitable solvent were kept as a negative control. After incubation for 24 h at 37 ± 1 °C, the last tube with no visible growth of the microorganism was taken to represent the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the complexes in each strain. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean of the triplicates was reported.15,41,42

2.5.2. Radical Scavenging Activity

The free radical scavenging activity of the free ligand and the corresponding Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes was measured using the stable radical DPPH described by the Blois method.44 A stock solution of the sample (1000 μg/mL) was prepared freshly in methanol, solutions of different concentrations (1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) were prepared from the stock solution, and 1 mL of 0.004% DPPH solution was added to the above test solutions according to the previous studies.13,45 The mixture was shaken vigorously and incubated for 30 min, and then the absorbance was measured at 517 nm in triplicate and ascorbic acid was used as a positive control parallel to the test compounds. In the absence of the test sample, 1 mL of the DPPH solution in 1 mL of methanol was used as the negative control.20,30 The scavenging capability of the DPPH radical was calculated using the following eq 1

| 1 |

where AI is the absorbance of the DPPH solution without the samples and AS is the absorbance of the titled compounds with the DPPH solution. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated from the intercept and the slope of the plotted graph of percent radical scavenging activity vs serial concentrations of the targeted samples.

2.6. Computational Studies

Geometry optimizations of the ligand (H2L) and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were performed using the Gaussian 16 program package.46 The results were visualized using GaussView 06 and Chemcraft. The DFT and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations were done using the B3LYP hybrid functional47−49 together with the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set50 for the light atoms and LanL2DZ basis sets for the metal atoms to account for relativistic effects. Grimme’s dispersion correction was made to consider nonbonding interactions during the calculations.51 This method has been used and gave results, which are in good agreement with the corresponding experimental results in our previous studies.13,52−54 Methanol and the polarizable continuum model in its integral equation formalism (IEF-PCM)55 were employed to mimic the experimental synthesis method and consider solvent effects. The same method and level of theory as that of the geometry optimizations was employed to calculate the frequencies and confirm that the optimized geometries are real minima. The computation of the Eigenvalues for the frontier molecular orbitals, dipole moments of the optimized geometries, and quantum chemical descriptors were calculated and performed similarly to our previous reports.13,53,54

2.7. Molecular Docking

The interaction and the binding affinity of the ligand and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were investigated with two key bacterial protein receptors using molecular docking studies. The molecular docking analysis of the free ligand and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes was performed using AutoDock 4.2 (MGL tools 1.5.7) with previously reported protocol.56 The crystal structures of the receptor proteins of E. coliDNA gyrase B (PDB ID 6F86) and the P. aeruginosa LasR (PDB ID: 2UV0) were downloaded from the protein database and processed by removing the cocrystallized ligand, deleting water molecules, and adding polar hydrogen and cofactors according to the AutoDock 4.2 (MGL tools1.5.7) procedure. Then, the grid box was set with the graphical user interface program. The grid was used to surround the key amino acid residue (Asp-73, Tyr-47, Trp-60, and Val-76 for PDB ID: 2UV0 and Asp-73, Asn-46, Arg-76, and Gly-77 for PDB ID: 6F86) regions in the macromolecule. The redocking was validated with grid center coordinates 58, 58, and 40 pointing in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, with a grid point spacing of 0.375 Å. The center grid box was 14.527, 56.689, and −5.122 Å.53 Standard docking parameters were used for the metals. Nine different conformations were generated for each targeted ligand and complexes. The conformation of the free ligand and the complexes with the least free binding energy was selected to analyze their interaction with the receptors using the Discovery Studio Visualizer and PyMOL (Version 2).57

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The antibacterial evaluation data of the ligand and the synthesized Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were recorded in triplicate (mean ± standard deviation). The graphical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 (GraphPad Software, California).13,58 Hence, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test on behalf of correlation with significance (p < 0.05) was evaluated for significant differences with groups (Table S1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of the Ligand and Its Transition-Metal Complexes

The synthesis of ligand (H2L) [(H2L) = 2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinoline-3-carbaldehyde] from (E)-2-(((2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinolin-3-yl)methylene)amino) ethanol afforded a good yield (85%), as indicated in Scheme 1. The physicochemical properties of the ligand and the complexes are presented in Table 1. The ligand and its metal complexes were soluble in methanol, ethanol, and water (polar solvents) but insoluble in hexane, dichloromethane, and chloroform (nonpolar solvents).

Scheme 1. Proposed Synthesis Reaction Scheme of (A) Ligand (H2L) and (B) Zn(II) and Cu(II) Complexes.

Table 1. Physicochemical Properties of the Free Ligand and Its Zn(II) and Cu(II) Complexes.

| compounds | color | yield (%) | conductivity (Ω–1 mol–1 cm2, 25 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C12H12N2O2 (H2L) | yellow | 85 (3.50 g) | |

| [Zn(HL)2] (1) | yellowish white | 72 (0.41 g) | 20 |

| [Cu(HL)2(H2O)2] (2) | deep green | 64 (0.39 g) | 21 |

3.2. Molar Conductance

The molar conductance of the free ligand and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes was measured in methanol with a concentration of 1 mM of the complexes59 and was found to be 20 and 21 Ω–1 mol–1 cm2 at 25 °C, respectively (Table 1). The molar conductance was very low, indicating that the complexes consist of lower electrolytes, which resulted in the nonelectrolytic nature of the complexes.60,61 As noted above, the two synthesized complexes are soluble in polar solvents and insoluble in nonpolar solvents. Their solubility mainly emanates from the polarity and polar groups of the ligand (Scheme 1). However, since there are no coordinated anionic species in the coordination sphere of the two synthesized complexes (vide infra), dissolving the complexes in polar solvents does not result in ionic species in the ionization sphere, resulting in the low conductivity of the two complexes. This was also further confirmed by the chloride test for the Zn(II) complex. This is in line with a previous report for similar complexes.62

3.3. Determination of Binding Stoichiometry and Formation Constants

The binding stoichiometry of Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes was determined with Job’s continuous variation method. The binding stoichiometry of the ligand with the two metal ions was determined by measuring the absorbance spectra at λmax values of 393 and 351 nm, respectively, for Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes. The Job’s plot was constructed by varying the mole fraction with constant total concentration (1 × 10–5 M) throughout the experiment (Figure S4A,B). The point of intersection was found at 0.65, which suggested a 1:2 metal-to-ligand [M/HL] stoichiometric ratio, in agreement with related studies.63−65 Similarly, the formation constant (K) was evaluated spectroscopically at different temperatures (Table S2). From the extrapolated Job’s plot (Figure S4A,B), both the Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes have K values of 2.47 × 108 and 4.29 × 108, respectively, which is in line with previously reported studies (Table 2).13,63−65

Table 2. Thermodynamic Parameters of the Novel Zn(II) and Cu(II) Complexes.

| complexes | 1 | 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| temp. (K) | 298 | 303 | 310 | 313 | 298 | 303 | 310 | 413 |

| ln K | 19.33 | 19.32 | 19.32 | 19.32 | 19.88 | 19.88 | 19.87 | 19.87 |

| –ΔG (kJ/mol) | 47.78 | 48.59 | 49.71 | 50.19 | 49.22 | 50.04 | 51.20 | 51.70 |

| –ΔH (J/mol) | 52.93 | 17.62 | ||||||

| ΔS (J/mol) | 160.52 | 165.22 | ||||||

From the plot of ln K vs 1/T (Figure S5), we determined the thermodynamic parameters (ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS). The negative values of change in Gibbs free energy and enthalpy showed the spontaneity of the metal–ligand interactions and the exothermic nature of the reactions. Moreover, the positive values of the change in entropy (ΔS) showed that complex formations are entropically favored,66,67 also implying that the complexes are thermally stable up to 40 °C (Table S2). This is in good agreement with the thermal analysis study (vide infra), which indicated that both complexes are stable up to 100 °C.

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectra of the Free Ligand and Its Zn(II) and Cu(II) Complexes

FT-IR spectra of the ligand and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were compared with those of the precursor ligand to determine the coordination sites, which may be involved in the metal complexation process. The detailed results and related explanations are presented in Table 3 and Figures S6, S7. The Zn(II) complex has the possibility of forming complexes with both the bulky groups in the same side or in opposite sides (Figure S8). However, the DFT calculations showed that the geometry with the two bulky groups on the same side is stable by 1.84 kcal/mol than the other conformer. The IR spectra of the free ligand showed characteristic strong stretching bands at 1679 (calcd 1678) cm–1 corresponding to the ν(C=O) aldehyde carbonyl group and 1618 (calcd 1584) cm–1 for ν(C=N) of the quinoline ring.5 This band shifted toward a lower frequency in the spectra of both the metal complexes in the range (1642–1646) cm–1 for ν(C=O)68,69 and shifted to higher frequencies ranging from 1562 to 1622 cm–1 for ν(C=N), indicating the involvement of the ligand in dative bond formation in both metal complexes.2,15,24,70,71 The bands around 2923–2926 cm–1 are for aliphatic C–H stretching and 3035–3066 cm–1 correspond to C–H aromatic vibrations for all of the synthesized compounds. In another case, the medium stretching frequency of the ligand at 3361 (calcd 3709) cm–1 ν(O–H) disappeared in the case of both Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes due to deprotonation; however, there exists coordinated water molecule in the Cu(II) complex, which is attributed to the broad bands ν(O–H) group observed at 3689–3094 cm–1. Both the experimental and calculated results indicated the participation of the oxygen atom of the ligand through the deprotonated hydroxyl group in complex formation. Similarly, the medium FT-IR stretching frequency of the ligand at 1079 cm–1 for ν(C–O) was diminished to lower frequency regions of 1057 cm–1 for Cu(II) and 1056 cm–1 for the Zn(II) complex. This is an indication of the participation of the deprotonated oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group in complex formation. However, there exist coordinated water molecules in the Cu(II) complex that contribute to the O–H group in which a broad band in the range of 3689–3298 cm–1 was observed. In addition, the medium FT-IR stretching frequency of the ligand at 3245 cm–1 for ν(N–H) was enhanced to higher frequency regions 3398 and 3290 cm–1 for both Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes, respectively. This is an indication of the participation of the amine nitrogen atom in complex formation.13,29,70 The NH group is preferred for coordination and hence N from the quinoline ring (imine group) is sterically hindered when compared with the aliphatic nitrogen atom of the amine group. In addition, low solubility, which might arise from the generation of the polynuclear structure due to the nitrogen atom of the quinoline ring participating in coordination is not observed, and hence the complexes were found to be soluble in polar solvents. Moreover, a very weak vibrational band was observed at 598 cm–1 for ν(Zn–O) and a medium band at 529 cm–1 for ν(Zn–N) bonds of the zinc complex and medium bands at 607 and 544 cm–1 for ν(Cu–O and Cu–N) bonds of the copper complex, in line with literature data.2,15,24,70,71 This indicates that both Zn(II) and Cu(II) metals were bonded to the donor atoms of the ligand during the complexation process.

Table 3. FT-IR Data of the Ligand and Its Zn(II) and Cu(II) Complexesa,b.

| Cpds. | ν(O–H) | ν(N–H) | ν(C–H) Arom. | ν(C–H) Aliph. | (C=O) Aldeh.y | ν(C=N) Ql. | ν(C–O) | ν(M–O) | ν(M–N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2L | 3361s,w (3709) | 3245b,w (3535) | 3035 (3103) | 2923w (3021) | 1679s (1678) | 1618s (1584) | 1079m (1047) | ||

| 1 | 3398 (3428) | 3065w (3125) | 2925m (3055) | 1642s (1679) | 1622s (1588) | 1056m (1085) | 598w (560) | 529w (482) | |

| 2 | 3689-3298b,s (3740) | 3290 (3400) | 3066w (3113) | 2926m (2952) | 1646s (1679) | 1562s (1586) | 1057s (1076) | 607m (576) | 544m (490) |

The B3LYP-GD3/6-311++G**/LanL2DZ-calculated results are presented in parenthesis.

s = strong, m = medium, str = stretching, b = broad, w = weak, Cpds. = Compounds.

3.5. UV–Visible Spectroscopy

The electronic spectra of the free ligand and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were obtained using dilute methanolic solutions (1 × 10–5 M) of the sample at room temperature.45 The results are presented in Table 4, Figure 1, and Figure S9. The free ligand exhibited absorption bands at 231 and 261 nm (π → π*) and 305 and 408 nm (n → π*) (Figure S9). But these bands blue-shifted at different absorbance values in the case of the metal complexes.72 The hypsochromic effect24,71 shows the formation of the titled metal complexes when compared with the free ligand (Figure 1).

Table 4. Electronic Spectra of the Free Ligand and Its Zn(II) and Cu(II) Complexes.

| compounds | absorption (nm) | transition |

|---|---|---|

| H2L | 231, 261, 305, 408 | (π → π*), (π → π*), (n → π*), and (n → π*) |

| 1 | 231, 259, 303, 393 | (π → π*), (π → π*), (n → π*), and (n → π*) |

| 2 | 255, 351 | (n → π*) and LMCT |

Figure 1.

Comparison of the experimental absorption wavelengths with the corresponding B3LYP-GD3/6-311++G(d,p)/LanL2DZ/IEF-PCM/Methanol-calculated results of the Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes. The calculated absorption maxima red-shifted by 20 nm for better comparison with the experimental results.

The observed spectral features of the Zn(II) complex observed at 231 and 259 were assigned to π → π* and 303 and 393 to n → π* transitions, and those of the Cu(II) complex at the spectral band of 255 nm was assigned to the n → π* transition.29,73−75 Additionally, the broad band observed at 351 nm for Cu(II) may be assigned to the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT), in line with our DFT calculations (Figure 2), which showed the presence of electron transitions from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the ligand to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the metal center.24,71,74,76 There is no d → d transition band for the Cu(II) complex; however, ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) was observed to be dominant, in agreement with the literature.74,77 This is due to the vacant d-orbital of the Cu(II) complex and the presence of lone-pair electrons on the ligand.78,79 Similar trends were found in the TD-DFT-calculated absorption spectra (Figures 1 and S9).

Figure 2.

(a) HOMO and LUMO of the ligand and its metal complexes. (b) Spin density plots of the Cu(II) complex. The HOMO–LUMO energies are in hartrees.

The wave function analysis (Figure 2) of the ligand showed that the HOMO of the ligand electron density resided on the quinoline ring and ethanolamine part of the molecule, whereas the LUMO of the ligand was found to reside on the quinoline part of the molecule and the carbonyl part of the molecule, revealing the possibility of π → π* and n → π* electronic transitions. The HOMO and LUMO of the Zn(II) complex (1) were found to show different band gap energies and wave function distributions (Figure 2), which clearly showed that the HOMO and LUMO reside on the metal and ligand part of the complex, respectively. This indicates the possible π → π* electronic transitions. However, in the case of the Cu(II) complex, the HOMO and LUMO are localized over the coordinated system, with the ligand for the HOMO and the metal center for the LUMO, inferring the possible LMCT electronic transitions. The spin density analysis of the Cu(II) complex showed that the unpaired electron spin density is delocalized over the metal d-orbitals (Figure 2).

3.6. Quantum Chemical Analysis

Analysis of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) was used to compare the reactivity of the free ligand (H2L) and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes. The HOMO–LUMO energy gap (Eg) can be associated with the antibacterial and antioxidant activities.29,61 Accordingly, the energy gaps (Eg = ELUMO– EHOMO) for possible electron transitions were calculated to be 3.533, 3.580, and 2.973 eV for the H2L and Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes (Table 5), respectively. These band gap energy values were found to be in line with the experimentally found antioxidant activity of the complexes: Cu(II) > Zn(II) (Figure 7). The chemical reactivity of the complexes increases with a decrease in the energy gap (Eg) values. Based on this, it is deduced that the Cu(II) complex is more reactive than the Zn(II)complex, in line with previously reported studies.29,61 Moreover, the reaction between copper and the ligand has reduced the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of the Cu(II) complex, an indication of improved biological activities. Accordingly, from the band gap and dipole moment results, the metal complexes showed better biological activities than the free ligand, also in line with the experimental biological activities. The Eigenvalues for the HOMO of the ligand and its metal complexes (Table 5) showed the improvement of the softness of the metal complexes than the ligand, inferring the potential of the synthesized metal complexes to interact with soft molecules. According to the HSAB principle, “soft acids prefer to bind with soft bases and hard acids prefer to bind with hard bases”, and it is observed that the higher global softness of the Cu(II) complex than the Zn(II) complex is in a good agreement with the results obtained for antibacterial activities (Table 8). Similarly, from the results of the electronic chemical potential (μ), the Cu(II) complex has a stronger reactivity than the Zn(II) complex. As known, chemical potential can be used to determine the chemical reactivity of molecules, which is directly proportional to the spontaneity of the reactions. The chemical reactivity increases with decreasing chemical potentials. Our calculated results were found to be in line with the spectroscopically determined thermodynamic parameters (Table 2). In addition, electrophilicity (ω) and nucleophilicity index (Nu) parameters showed that the Cu(II) complex has a higher electrophilicity index than the Zn(II) complex, implying that the Cu(II) complex has the ability to accept electrons,61 and the Zn(II) complex has a stronger nucleophilicity index (Table 5).

Table 5. HOMO Energy, LUMO Energy, Energy Gap (Eg), Electronegativity (χ), Electronic Chemical Potential (μ), Global Hardness (η), Softness (σ), Electrophilicity (ω), Nucleophilicity Index (Nu), Dipole Moment of the Ligand, and Metal Complexes in eV (Cpds = Compounds).

| Cpds. | EHOMO | ELUMO | Eg | χ | M | η | σ | Ω | Nu | dipole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2L | –6.117 | –2.584 | 3.533 | 4.350 | –4.350 | 1.766 | 0.283 | 5.357 | 0.187 | 4.737 |

| 1 | –6.352 | –2.772 | 3.580 | 4.562 | –4.562 | 1.790 | 0.279 | 5.814 | 0.172 | 14.794 |

| 2 | –6.120 | –3.147 | 2.973 | 4.633 | –4.633 | 1.487 | 0.336 | 7.220 | 0.138 | 1.863 |

Figure 7.

(A) Percent of free radical scavenging activities and (B) IC50 of titled compounds.

Table 8. Mean Zone of Inhibition of Synthesized Compounds in mm (Mean ± SD).

| compounds |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bacterial strains | conc. (μg/mL) | 1 | 2 | H2L | ciprofloxacin |

| E. coli | 100 | 14.62 ± 2.00 | 13.79 ± 0.65 | 10.66 ± 1.75 | 20.79 ± 2.00 |

| 200 | 16.71 ± 1.50 | 14.55 ± 1.75 | 11.55 ± 0.68 | 21.54 ± 1.78 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 100 | 18.67 ± 0.50 | 19.56 ± 0.84 | 8.50 ± 0.52 | 19.99 ± 0.95 |

| 200 | 20.75 ± 2.05 | 20.9 ± 2.00 | 9.60 ± 2.00 | 20.94 ± 2.01 | |

| S. aureus | 100 | 13.76 ± 0.75 | 18.71 ± 0.82 | 10.66 ± 0. 39 | 20.81 ± 0.84 |

| 200 | 14.70 ± 0.86 | 19.69 ± 0.71 | 10.96 ± 0.96 | 21.72 ± 0.64 | |

| S. pyogenes | 100 | 11.57 ± 0.79 | 18.58 ± 1.04 | 0.00 ± 00 | 19.53 ± 0.91 |

| 200 | 12.62 ± 0.50 | 19.75 ± 0.93 | 0.00 ± 00 | 20.79 ± 0.73 | |

3.7. Fluorescence Study

The emission spectra of the free ligand (H2L) and its corresponding Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes showed emission bands at 487, 460, and 471 nm, respectively (Table 6). The complexation of metal ions with the free ligand induces the hyperchromic (intense) and hypsochromic (blue shift) shifts. The metal complexes showed intense fluorescent intensities as compared with their precursor ligand (Figure 3).13

Table 6. Absorption, Emission, Wavelength, and Intensity of Free Ligand and Its Complexes.

| compounds | absorption λmax (intensity) | emission λmax (intensity) |

|---|---|---|

| H2L | 408 (0.10) | 487 (102.05) |

| 1 | 393 (0.09) | 460 (483.91) |

| 2 | 351 (0.25) | 471 (835.57) |

Figure 3.

Fluorescence spectra of the free ligand (H2L) and its (1) Zn(II) and (2) Cu(II) complexes.

The observed emission of the Zn(II) complex could be due to the intraligand emissions,72 while in the case of the Cu(II) complex, the enhancement in intensity compared with the free ligand was due to ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT). Generally, the emission intensities of the Zn(II) complex were found to be nearly 4-fold and those of Cu(II) were 8-fold greater than that of the free ligand. These results indicate that the Zn(II) complex could be used for photochemical applications80 and the participation of the ligand in coordinate covalent bond formation, in which the emission peaks have blue-shifted by 12–25 nm. These analyses are in agreement with the previously reported studies.72,80,81

3.8. X-ray Diffraction Study

The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the synthesized Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes showed an amorphous structure (Figure S10) as confirmed by the XRD pattern of the complexes, which indicated a broad peak in the range of 2θ = 5–80°.31,82

3.9. EDX-SEM analysis

The composition of the free ligand and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes was obtained from energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis. In the EDX spectrum, the Zn(II) complex showed four signals, which correspond to carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and zinc. This proves that the metal complex existed without any impurity. It also clearly confirms the formation of the CHZnNO compound (Figure 4A). Similarly, the EDX spectrum of the Cu(II) complex showed four characteristic signals corresponding to carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and copper. Hence, the complex was present without any impurity, and the formation of the complex with the elemental composition of CHCuNO (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectra of (A) Zn(II), (B) Cu(II), and (C) H2L(II). SEM images of (D) Zn(II) and (E) Cu(II) complexes and (F) H2L(II).

Finally, in a similar fashion, the EDX spectrum of the free ligand exhibited three characteristic signals assigned to carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen, indicating the CHNO composition of the free ligand (Figure 4C). The analyses also indicated that the experimental percentage compositions of the atoms were found to be very close to those of the theoretical values, in line with previously reported studies.13,83,84 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to evaluate the morphology and particle size of the compounds. The SEM micrographs showed the agglomerated particles of the compounds. The free ligand (H2L) and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes showed the mass of agglomerations (Figure 4D–F). Both the SEM images and the powder XRD data agreed with each other, in which all compounds showed amorphous-like structures.13,83−86

3.10. Mass Spectrometry (MS)

To get a confirmation of the complete formation of the complexes, the synthesized H2L and its Zn(II) and Cu(II) metal complexes were subjected to LC-MS spectrometric analysis. The results are presented in the SI (Figure S11). For the ligand, a molecular ion peak was obtained at an m/z of 215.75 (calcd 216.09), corresponding to [C12H12N2O2] with a molecular weight of 216.24 g/mol (Figure S11A). In the case of the Zn(II) complex, a molecular ion peak was found at an m/z of 493.95 (calcd 494.09), corresponding to [C24H22N4O4Zn] with a molecular weight of 495.84 g/mol (Figure S11B). In addition, the spectrum also exhibited other peaks at m/z values of 435.95 (62.30%) (calcd 436.09) and 386.35 (30.80%) (calcd 386.07), which correspond to the possible fragments of [C22H20N4O2Zn]+ and [C18H18N4O2Zn]+, respectively. On the other hand, the Cu(II) complex exhibited a molecular ion peak at an m/z of 529.45 (calcd 529.11), which corresponds to the formula [C24H26CuN4O6] with a molecular weight of 530.03 g/mol (Figure S11C). This complex also showed a peak at an m/z of 392.75 (60.80%) (calcd 393.04), leading to a possible [C19H14CuN4O2]+ fragment. This is in line with the previously reported studies.38,87−89

3.11. Thermogravimetric Analysis (Thermal Studies)

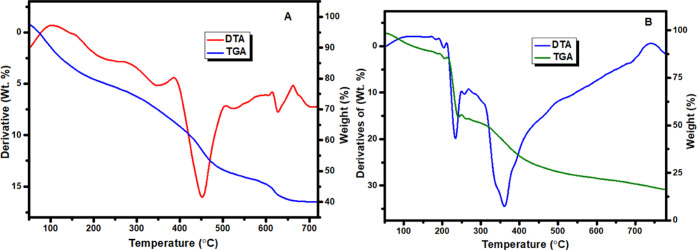

The TGA and DTA curves presented in Figure 5, Figure S10, and Table 7 reflect the maximum temperature values with the corresponding weight losses for each step of decomposition reactions of the Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes. The obtained data strongly support the formulae proposed.

Figure 5.

TGA and DTA curves of (A) Zn(II) and (B) Cu(II) complexes.

Table 7. Temperature Range Values for Decomposition and Corresponding Weight Loss Values.

| mass loss

(%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| decomposition temp. (°C) | obsd. | calcd | peak type | interpretation | |

| 1 | 100–250 | 18.06 | 18.16 | Exo | loss due to C6H4N of the quinoline ring moiety |

| 280–385 | 10.78 | 10.89 | Exo | loss due to C3H2O of the carbonyl moiety | |

| 395–505 | 20.42 | 20.58 | Exo | loss due to C7H4N of the quinoline ring with an amine substituent | |

| 510–610 | 5.51 | 5.44 | Exo | loss due to CHN of the amine moiety | |

| 620–665 | 6.26 | 6.26 | Endo | loss due to CH3O of the carbonyl moiety | |

| 2 | 100–210 | 9.86 | 9.81 | Exo | loss of two water molecules and carbonyl oxygen |

| 215–312 | 39.87 | 40.01 | Exo | loss of C13H12N2O of the quinoline ring with an amine substituent | |

| 320–720 | 33.90 | 34.16 | Exo | loss due to C11H5N2O of the amine with a quinoline ring | |

The TGA curve of [C24H22N4O4Zn] exhibited approximately five stages of decomposition (Figures 5A and S12A). The first stage that occurred at a temperature range of 100–250 °C was related to the C6H4N quinoline ring moiety with a weight loss of 18.06% (calcd 18.16%). The second step of decomposition occurred within a temperature range of 280–385 °C, accompanied by a weight loss of 10.78% (calcd = 10.89%), which corresponds to a loss due to C3H2O of the carbonyl moiety. The third step of degradation recorded in the temperature range of 395–505 °C having a weight loss of 20.42% (calcd = 20.58%) could be attributed to the loss of C7H4N of the quinoline ring with an amine substituent moiety. The fourth step of degradation observed in the temperature range of 510–610 °C with a weight loss of 5.51% (calcd = 5.44%) might be due to the loss of CHN of the amine moiety. The fifth and final step of degradation occurred in the temperature range of 620–665 °C and resulted in a weight loss of 6.26% (calcd = 6.26%) attributed to the loss of CH3O of the carbonyl moiety. Thereafter, the compound showed a gradual decomposition up to 665 °C with a weight loss of many organic moieties. The weight of the residue, which corresponds to the respective zinc oxide (ZnO) and some organic moieties (C4H7NO + C2H4) was about 38.97% (calcd = 38.67%). These results are in line with previously reported studies.45,90

The thermal decomposition of complex 2 [C24H26CuN4O6] proceeds with three main degradation steps (Figures 5B and S12B). The first stage of decomposition occurred at a temperature range of 100–210 °C. The weight loss related to this step was 9.86% and could be due to the loss of two water molecules and the carbonyl oxygen moiety, which is in agreement with the calculated value of 9.81%. In addition, the second stage of decomposition occurred at a temperature range of 215–312 °C. The weight loss found associated with this step is 39.87% and may be attributed to the loss of C13H12N2O of the quinoline ring with an amine substituent moiety, which is in line with the calculated value of 40.01%. The third and final stage of decomposition occurred at a temperature range of 320–720 °C, and the weight loss found at this stage was equal to 33.9%, corresponding to a loss due to C11H5N2O of the amine with a quinoline ring, which is in agreement with the calculated value of 34.16%. This complex decomposed into three steps with a total mass loss of 83.64% (calcd = 83.98%) and 15.36% mass loss, leaving copper oxide (CuO) as a residue (Table 5), which is in very good agreement with the calculated value of 15.01% and related reported studies.75,90,91

3.12. Biological Applications

3.12.1. Antibacterial Activity

The synthesized ligand and the corresponding Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were evaluated for their in vitro antibacterial activities against four human pathogenic bacteria using the disk diffusion and agar dilution assay methods. The results are presented in Tables 8 and 9. The disk diffusion data showed that both Zn(II) and Cu(II) metal complexes exhibited medium-to-high antibacterial activity against the targeted bacterial strains with mean zones of inhibition that ranged from medium (11.57 ± 0.79 mm at 100 μg/mL) to high (20.9 ± 2.00 mm at 200 μg/mL). Both metal complexes showed good activities against P. aeruginosa, with mean inhibition zones of 20.75 ± 2.05 and 20.9 ± 2.00 mm in diameter at 200 μg/mL, respectively, when compared with the positive control, ciprofloxacin, which has a mean inhibition zone of 20.94 ± 2.01 within similar concentrations (Table 8).

Table 9. Antimicrobial Activity of the Complexes against Selected Bacterial Strains (MIC in μg/mL).

| bacterial

strains |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| complexes | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | S. pyogenes |

| 1 | 125.0 | 1.95 | 15.63 | >250 |

| 2 | 125.0 | 0.98 | 3.91 | 62.5 |

| ciprofloxacin | <0.49 | <0.49 | 0.98 | 31.25 |

The Cu(II) complex has high antibacterial activities with the range of zone of inhibition from 13.79 ± 0.65 to 20.9 ± 2.00 mm at both concentrations of 100 and 200 μg/mL for all of the bacterial strains (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. pyogenes, and S. aureus). The free ligand has 11 and below mean zones of inhibition for E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus, whereas it has no antibacterial activity against the Gram-positive bacteria, S. pyogenes. This indicates that the precursor ligand has lower antibacterial activity than Zn(II) and Cu(II) metal complexes (Table 8 and Figure 6). This is in agreement with the fact that the antimicrobial activity of metal complexes can be elucidated on the basis of chelation theory, which suggested that chelation could promote the ability of the complexes to pass through a cell membrane.13,39,40,80 From the results, the complexes were found to be potential antibacterial agents when compared to the standard drug.

Figure 6.

Mean inhibition zone of bacterial activity of the titled compounds. n = 3. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Furthermore, the results shown in Table 9 indicate better antibacterial activity for complex 2 against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes with MIC values of 0.98, 3.91, and 62.5 (μg/mL), respectively. Both complexes showed significant antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa in comparison to other bacterial strains and have smaller MIC values against this bacteria, in which complex 2 is stronger than complex 1 in all four bacterial strains. However, in all cases, the minimum inhibitory concentrations are somewhat larger than those of ciprofloxacin and the parent ligand.

The character of the metal ions coordinated to the ligand may have its own role in such difference, in addition to the chelation, which considerably increases the lipophilic character of the central metal ion because of the partial sharing of its positive charge with the donor groups and possible π-electron delocalization over the chelate ring. This favors the permeation through the lipid layer of the cell membrane. The increased liposolubility of the ligand upon being complexed with a metal may contribute to the easy transportation into the bacterial cells, which then blocks the metal-binding sites in the enzyme of microorganisms.27,38 Furthermore, different factors should be under consideration for metal complexes having antibacterial activities, viz, chelate effect, nature of the ligands, total charge of the complex, and nature of the ion that neutralizes the given ionic complex.13,27,38−40,80

3.12.2. Antioxidant Activity

The radical scavenging activities of the free ligand and its synthesized Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes were evaluated in terms of their proton-donating ability with UV–visible absorbance using the DPPH assay, which is a stable free radical that accepts proton or electron from corresponding donor compounds, resulting in the loss of the characteristic deep purple (λmax = 517 nm) color.13,44,86 Accordingly, the compounds that have antioxidant activity may reduce the absorbance at 517 nm corresponding to DPPH radicals, and hence the color of DPPH changes in the reaction process.13,86 From the results, it was observed that the complexes have higher antioxidant activities as compared to the precursor ligand (Figure 7 and Table S3). Such results have previously been reported for similar transition-metal complexes.11,20,21,30,84

Generally, in this work, when we compared the radical scavenging activities of the synthesized metal complexes, standard and free ligands, we found that A/A > 2 > 1 > H2L. This confirms that the free ligand has lower radical scavenging activities5 as compared with the standard (ascorbic acid), complexes 1 and 2. It can be concluded that metal complexes have more radical scavenging activities than their free ligand due to synergy effects. This makes the metal complexes have strong potential use as radical scavengers and eliminates radicals.20,21,30,75

Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of the titled free ligand and its complexes are shown in Figure 7B and Table S3 as radical eliminators. The ligand and its transition-metal complexes 2 and 1 exhibit IC50 values of 42.5, 4.72, and 8.2 μg/mL, respectively, while ascorbic acid has a value of 4.28 μg/mL. From IC50 values, both the complexes have good communication with a positive control, and these results are in good agreement with previously reported studies.74,75

3.13. Molecular Docking Analysis

Bioactive molecules inhibit either the reproduction of pathogenic bacteria or kill them by acting on some essential components of bacterial strains. DNA gyrase is one of the essential enzymes, which induces negative supercoils into bacterial DNA. In this aspect, fluoroquinolones are among DNA gyrase-targeted drugs.92 Some bacteria also secrete a variety of toxic substances, including exotoxin A (ETA), phospholipases, and several proteases and the like. P. aeruginosa is opportunistic pathogenic bacteria, which activate the expression of the LasR gene required for the transcription of the genes for elastase (LasA and LasB) protease, associated with virulence.93,94 Therefore, the molecular docking of the two complexes and the ligand was performed against the DNA gyrase of E. coli and LasR of P. aeruginosa to investigate their mode of action, and the results were compared with the in vitro antibacterial assays.

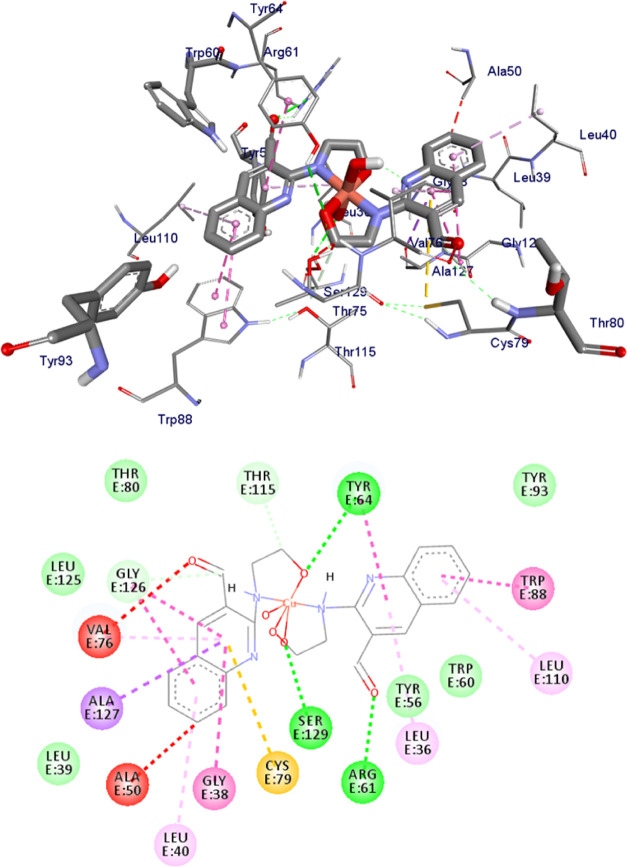

The molecular docking interaction was studied between the ligand and its complexes against the proteins of P. aeruginosa LasR (PDB ID: 2UV0) (Figures 8 and 9) and E. coli DNA gyrase B (PDB ID: 6F86) (Figures S14–S16) to understand the binding mechanism of action, in which all compounds interacted with the key amino acids of the two bacteria. Accordingly, the metal complexes have shown significant interactions within the active sites of the P. aeruginosa LasR.DNA protein through the key amino acids like Tyr-47, Trp-60, Asp-73, Tyr-64, Leu-36, Trp-88, and Arg-61 (see Table S4). Hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions with Arg-61 and Leu-36, Tyr-64, Val-76, Cys-79, Ala-127 for complex 1 and Arg-61, Tyr-64, Ser-129 and Leu-36, Val-76, Cys-79, Ala-127 for complex 2 showed moderate to equivalent binding scores compared to the clinical drug ciprofloxacin (see Table S4).

Figure 8.

Binding interactions of complex 1 against P. aeruginosa LasR.DNA (PDB: 2UV0).

Figure 9.

Binding interactions of complex 2 against P. aeruginosa LasR.DNA (PDB: 2UV0).

Similarly, the targeted compounds interacted with the key amino acids of E. coli DNA gyrase B by forming hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions; for instance, with Asn-46, Arg-76, and Thr-165 for complex 1 and Thr-165 and Glu-50 for complex 2 within the active sites (see Table 10). The results clearly showed that the free carbonyl oxygen chain in the complexes interacted with the amino acids within the active sites of the protein. Both the reported docking scores of the complexes showed better docking scores with binding energies of −7.4 and −7.0 kcal/mol for Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes, respectively, while that of the standard is −7.2 kcal/mol (Table 10).

Table 10. Molecular Docking Scores and Residual Amino Acid Interactions of Synthesized Compounds against E. coli DNA Gyrase B (PDB ID: 6F86).

| residual interactions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpds. | affinity (kcal/mol) | H-bond | hydrophobic/Pi-cation | van der Waals |

| H2L | –6.5 | Asp-73, Thr-165, Gly-77 | HOH-616, Asn-46, Ile-94, Ile-78, Val-43 | Val-71, Ala-47, Arg-76 |

| 1 | –7.4 | Asn-46, Arg-76 | Thr-165, Ala-47, Ile-78, Val-167, Gly-77, Glu-50 | Ile-94, Pro-79, Asp-73, Val-43 |

| 2 | –7.0 | Thr-165 | Glu-50, Arg-76, Pro-79 | Gly-77, Ile-78, Asp-49, Asn-46, |

| Cipro. | –7.2 | Asp-73, Asn-46, Arg-76 | Glu-50, Gly-77, Pro-79, Ile-78, Ile-94, Ile-78 | Ala-47 |

The Zn(II) complex has a stronger binding energy than ciprofloxacin since it interacts through more van der Waals forces within the active sites of the enzyme via Ile-94, Pro-79, Asp-73, and Val-43 amino acid residues, while the van der Waals interaction of the ciprofloxacin was only via Ala-47. Even though there are four amino acid residues (Gly-77, Ile-78, Asp-49, and Asn-46) within the active sites of the enzyme that interacted with the Cu(II) complex via van der Waals interaction, only Thr-165 interacted via a H-bond, whereas more H-bond interactions were possible with the Zn(II) complex and ciprofloxacin. On the other hand, the in vitro activities of the complexes against E. coli showed a mean inhibition zone (MIZ) of 14.55 ± 1.75 mm for the Cu(II) complex and 16.71 ± 1.50 mm for the Zn(II) complex, indicating that the docking results are in good agreement with the in vitro activities.

The molecular docking results of the complexes (1 and 2) and the ligand against the P. aeruginosa LasR binding domain were −8.6, −5.3, and −7.6 kcal/mol, respectively, whereas the affinity energy of ciprofloxacin in this case was found to be −8.3 kcal/mol. The in vitro mean inhibition zone of complexes 1 and 2 and the ligand (20.75 ± 2.05, 20.9 ± 2.00, and 9.60 ± 2.00 mm, respectively, Table 8) have slight differences in the docking results compared to those of E. coli DNA gyrase B. Thus, the complexes may hinder bacterial growth through inhibition of their DNA gyrase rather than the LasR protein. Indeed, this is in good agreement with the literature report that quinolones (fluoroquinolones) target the DNA gyrase of bacteria.92 Since the complexes in the current work were also developed on a quinoline scaffold, their mode of action could be through hindering the DNA gyrase of bacteria.

4. Conclusions

These novel Zn(II) and Cu(II) metal complexes were prepared with a bidentate ON donor ligand (H2L), [H2L = 2-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)quinoline-3-carbaldehyde]. The complexes were characterized by FT-IR spectroscopy, SEM-EDX spectroscopy, powder XRD, UV–vis spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, TGA, and mass spectroscopy. The comparison of the B3LYP-GD3-calculated IR frequencies and TD-B3LYP-GD3-calculated absorption spectra is in very good agreement with the corresponding experimental results. Such agreements further confirmed the analyses as well as the characterization of the complexes. Based on the comparison of the results from the FT-IR, mass spectral data, elemental analysis, TGA, and DFT calculations, we proposed that the Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes have tetrahedral and octahedral coordinate systems, respectively, with the bidentate nature of the free ligand. The results of the binding stoichiometry, elemental analysis, mass spectra, and thermogravimetric analysis deduced the formation of a 1:2 metals/ligand ratio, in both Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes and have formation constant (K) values of 2.47 × 108 and 4.29 × 108, respectively. Antimicrobial studies were carried out against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. pyogenes, and S. aureus using the disk diffusion and agar dilution methods. The results showed a significant increase in the antibacterial activity of the metal complexes as compared to the uncomplexed ligand due to chelation, with a mean inhibition zone ranging from 11.57 ± 0.79 to 20.90 ± 2.00 at 100 and 200 μg/mL concentrations. Specifically, the Cu(II) complex exhibited zones of inhibition that ranged from 18.58 ± 1.04 to 20.90 ± 2.00 mm (MIC = 62.5, 0.98, and 3.91 μg/mL) compared with ciprofloxacin with the zone of inhibition ranging from 19.53 ± 0.91 to 20.94 ± 2.01 mm (MIC = 31.25, 0.49, and 0.98 μg/mL) for S. pyogenes, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus, respectively, at the same concentration. The radical scavenging activity of the free ligand and its metal complexes was studied using the DPPH assay, and both Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes have shown very good free radical scavenging activities with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 4.72 and 8.2 μg/mL, respectively, while ascorbic acid (positive control) has a value of 4.28 μg/mL. The molecular docking results of the binding mode of these compounds against E. coli DNA gyrase B (PDB ID: 6F86) were found to be in good agreement with the in vitro biological activity results.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Adama Science and Technology University, Wachemo University and University of Botswana for the research facilities. Computational resources were supplied by Metacentrum under the project “e-Infrastruktura CZ” (e-INFRA CZ ID: 90140) supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c02205.

1H NMR, 13C NMR, DEPT-135, FT-IR, UV/vis, PXRD, mass spectra, TGA, Job’s curve, molecular docking, one-way analysis of variance, formation constant, and percent free radical scavenging (PDF)

Author Contributions

Experimental procedure: T.D., D.Z; data analysis: T.D., T.B.D., M.B., D.Z., T.D., and R.E; methodology: T.D., D.Z., T.D., T.B.D., M.B., and R.E; original draft writing: T.D. and T.D; and review and editing: T.D., T.B.D., M.B., T.D., and D.Z.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vicente D.; Basterretxea M.; de la Caba I.; Sancho R.; López-Olaizola M.; Cilla G. Low Antimicrobial Resistance Rates of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex between 2000 and 2015 in Gipuzkoa, Northern Spain. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2019, 37, 574–579. 10.1016/j.eimc.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargar H.; Ardakani A. A.; Tahir M. N.; Ashfaq M.; Munawar K. S. Synthesis, Spectral Characterization, Crystal Structure and Antibacterial Activity of Nickel(II), Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes Containing ONNO Donor Schiff Base Ligands. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1233, 1–12. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kargar H.; Behjatmanesh-Ardakani R.; Torabi V.; Kashani M.; Chavoshpour-Natanzi Z.; Kazemi Z.; Mirkhani V.; Sahraei A.; Tahir M. N.; Ashfaq M.; Munawar K. S. Synthesis, Characterization, Crystal Structures, DFT, TD-DFT, Molecular Docking and DNA Binding Studies of Novel Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes Bearing Halogenated Bidentate N,O-Donor Schiff Base Ligands. Polyhedron 2021, 195, 114988 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Łoboda D.; Rowińska-Zyrek M. Candida Albicans Zincophore and Zinc Transporter Interactions with Zn(II) and Ni(II). Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 2646–2654. 10.1039/C7DT04403H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digafie Z.; Melaku Y.; Belay Z.; Eswaramoorthy R. Synthesis, Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Molecular Modeling Studies of Novel [2,3′-Biquinoline]-4-Carboxylic Acid and Quinoline-3-Carbaldehyde Analogs. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 1–17. 10.1155/2021/9939506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Digafie Z.; Melaku Y.; Belay Z.; Eswaramoorthy R. Synthesis, Molecular Docking Analysis, and Evaluation of Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties of Stilbenes and Pinacol of Quinolines. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 2021, 1–17. 10.1155/2021/6635270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Zhang G.; Zhao J.; Cheng N.; Wang Y.; Fu Y.; Zheng Y.; Wang J.; Zhu M.; Cen S.; He J.; Wang Y. Synthesis and Antiviral Activity of a Series of Novel Quinoline Derivatives as Anti-RSV or Anti-IAV Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 214, 113208 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y.; Ruan Y.; Cheng B.; Li L.; Liu J.; Fang Y.; Chen J. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Acridine and Quinoline Derivatives as Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors with Anticancer Activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 46, 116376 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez–Prada J.; Robledo S. M.; Vélez I. D.; del Pilar Crespo M.; Quiroga J.; Abonia R.; Montoya A.; Svetaz L.; Zacchino S.; Insuasty B. Synthesis of Novel Quinoline–Based 4,5–Dihydro–1H–Pyrazoles as Potential Anticancer, Antifungal, Antibacterial and Antiprotozoal Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 131, 237–254. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q.; Zhou D. J.; Pan Z. Y.; Yang G. G.; Zhang H.; Ji L. N.; Mao Z. W. CAIXplatins: Highly Potent Platinum(IV) Prodrugs Selective Against Carbonic Anhydrase IX for the Treatment of Hypoxic Tumors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 18556–18562. 10.1002/anie.202005362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Dief A. M.; El-Metwaly N. M.; Alzahrani S. O.; Alkhatib F.; Abualnaja M. M.; El-Dabea T.; El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A. Synthesis and Characterization of Fe(III), Pd(II) and Cu(II)-Thiazole Complexes; DFT, Pharmacophore Modeling, in-Vitro Assay and DNA Binding Studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 326, 115277 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazmi G. A. A.; Abou-Melha K. S.; Althagafi I.; El-Metwaly N. M.; Shaaban F.; Abdul Galil M. S.; El-Bindary A. A. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Oxovanadium(IV) Complexes of Dimedone Derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, 1–16. 10.1002/aoc.5672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damena T.; Zeleke D.; Desalegn T.; B Demissie T.; Eswaramoorthy R. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Activities of Novel Vanadium(IV) and Cobalt(II) Complexes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 4389–4404. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazmi G. A. A.; Abou-Melha K. S.; El-Metwaly N. M.; Althagafi I.; Shaaban F.; Zaky R. Green Synthesis Approach for Fe (III), Cu (II), Zn (II) and Ni (II)-Schiff Base Complexes, Spectral, Conformational, MOE-Docking and Biological Studies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5403 10.1002/aoc.5403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azam M.; Mohammad Wabaidur S.; Alam M.; Trzesowska-Kruszynska A.; Kruszynski R.; Al-Resayes S. I.; Fahhad Alqahtani F.; Rizwan Khan M.; Rajendra Design, Structural Investigations and Antimicrobial Activity of Pyrazole Nucleating Copper and Zinc Complexes. Polyhedron 2021, 195, 114991 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri Rudbari H.; Iravani M. R.; Moazam V.; Askari B.; Khorshidifard M.; Habibi N.; Bruno G. Synthesis, Characterization, X-Ray Crystal Structures and Antibacterial Activities of Schiff Base Ligands Derived from Allylamine and Their Vanadium(IV), Cobalt(III), Nickel(II), Copper(II), Zinc(II) and Palladium(II) Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1125, 113–120. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.06.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M. C.; Perelmulter K.; Levín P.; Romo A. I. B.; Lemus L.; Fogolín M. B.; León I. E.; Di Virgilio A. L. Antiproliferative Activity of Two Copper (II) Complexes on Colorectal Cancer Cell Models: Impact on ROS Production, Apoptosis Induction and NF-KB Inhibition. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 169, 106092 10.1016/j.ejps.2021.106092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordestani N.; Amiri Rudbari H.; Fernandes A. R.; Raposo L. R.; Luz A.; Baptista P. V.; Bruno G.; Scopelliti R.; Fateminia Z.; Micale N.; Tumanov N.; Wouters J.; Abbasi Kajani A.; Bordbar A. K. Copper(Ii) Complexes with Tridentate Halogen-Substituted Schiff Base Ligands: Synthesis, Crystal Structures and Investigating the Effect of Halogenation, Leaving Groups and Ligand Flexibility on Antiproliferative Activities. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 3990–4007. 10.1039/D0DT03962D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Metwaly N.; Althagafi I.; Katouah H. A.; Al-Fahemi J. H.; Bawazeer T. M.; Khedr A. M. Synthesis of Novel VO (II)-Thaizole Complexes; Spectral, Conformational Characterization, MOE-Docking and Genotoxicity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, e5095 10.1002/aoc.5095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gammal O. A.; Mohamed F. S.; Rezk G. N.; El-Bindary A. A. Synthesis, Characterization, Catalytic, DNA Binding and Antibacterial Activities of Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) Complexes with New Schiff Base Ligand. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 326, 115223 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.115223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Melha K. S.; Al-Hazmi G. A.; Althagafi I.; Alharbi A.; Shaaban F.; El-Metwaly N. M.; El-Bindary A. A.; El-Bindary M. A. Synthesis, Characterization, DFT Calculation, DNA Binding and Antimicrobial Activities of Metal Complexes of Dimedone Arylhydrazone. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334, 116498 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abumelha H. M.; Alkhatib F.; Alzahrani S.; Abualnaja M.; Alsaigh S.; Alfaifi M. Y.; Althagafi I.; El-Metwaly N. Synthesis and Characterization for Pharmaceutical Models from Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II)-Thiophene Complexes; Apoptosis, Various Theoretical Studies and Pharmacophore Modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 328, 115483 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koleša-Dobravc T.; Maejima K.; Yoshikawa Y.; Meden A.; Yasui H.; Perdih F. Bis(Picolinato) Complexes of Vanadium and Zinc as Potential Antidiabetic Agents: Synthesis, Structural Elucidation and: In Vitro Insulin-Mimetic Activity Study. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 3619–3632. 10.1039/C7NJ04189F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halevas E.; Mavroidi B.; Pelecanou M.; Hatzidimitriou A. G. Structurally Characterized Zinc Complexes of Flavonoids Chrysin and Quercetin with Antioxidant Potential. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 523, 120407 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagesh G. Y.; Mahendra Raj K.; Mruthyunjayaswamy B. H. M. Synthesis, Characterization, Thermal Study and Biological Evaluation of Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) Complexes of Schiff Base Ligand Containing Thiazole Moiety. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1079, 423–432. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atasever Arslan B.; Kaya B.; Şahin O.; Baday S.; Saylan C. C.; Ülküseven B. The Iron(III) and Nickel(II) Complexes with Tetradentate Thiosemicarbazones. Synthesis, Experimental, Theoretical Characterization, and Antiviral Effect against SARS-CoV-2. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1246, 131166 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeek S. A.; El-Attar M. S.; Abd El-Hamid S. M. Preparation and Characterization of New Tetradentate Schiff Base Metal Complexes and Biological Activity Evaluation. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1051, 30–40. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.07.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchárová V.; Kuchár J.; Lüköová A.; Jendželovský R.; Majerník M.; Fedoročko P.; Vilková M.; Radojević I. D.; Čomić L. R.; Potočňák I. Low-Dimensional Compounds Containing Bioactive Ligands. Part XII: Synthesis, Structures, Spectra, in Vitro Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities of Zinc(II) Complexes with Halogen Derivatives of Quinolin-8-Ol. Polyhedron 2019, 170, 447–457. 10.1016/j.poly.2019.05.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I. A. I.; El-Sakka S. S. A.; Soliman M. H. A.; Mohamed O. E. A. In Silico, In Vitro and Docking Applications for Some Novel Complexes Derived from New Quinoline Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1196, 8–32. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.06.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sonbati A. Z.; Diab M. A.; Abbas S. Y.; Mohamed G. G.; Morgan S. M. Preparation, Characterization and Biological Activity Screening on Some Metal Complexes Based of Schiff Base Ligand. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 4125–4136. 10.21608/ejchem.2021.68740.3515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Metwaly N.; Althagafi I.; Khedr A. M.; Al-Fahemi J. H.; Katouah H. A.; Hossan A. S.; Al-Dawood A. Y.; Al-Hazmi G. A. Synthesis and Characterization for Novel Cu(II)-Thiazole Complexes-Dyes and Their Usage in Dyeing Cotton to Be Special Bandage for Cancerous Wounds. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1194, 86–103. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.05.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyramabadi S. A.; Saadat-Far M.; Faraji-Shovey A.; Javan-Khoshkholgh M.; Morsali A. Synthesis, Experimental and Computational Characterizations of a New Quinoline Derived Schiff Base and Its Mn(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1208, 127898 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kargar H.; Behjatmanesh-Ardakani R.; Torabi V.; Sarvian A.; Kazemi Z.; Chavoshpour-Natanzi Z.; Mirkhani V.; Sahraei A.; Nawaz Tahir M.; Ashfaq M. Novel Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes of Halogenated Bidentate N,O-Donor Schiff Base Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, Crystal Structures, DNA Binding, Molecular Docking, DFT and TD-DFT Computational Studies. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2021, 514, 120004 10.1016/j.ica.2020.120004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chai L.-Q.; Tang L.; Chen L.; Huang J. Structural, Spectral, Electrochemical and DFT Studies of Two Mononuclear Manganese (II) and Zinc (II) Complexes. Polyhedron 2017, 122, 228–240. 10.1016/j.poly.2016.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sonbati A. Z.; Diab M. A.; Eldesoky A. M.; Morgan S. M.; Salem O. L. Polymer Complexes. LXXVI. Synthesis, Characterization, CT-DNA Binding, Molecular Docking and Thermal Studies of Sulfoxine Polymer Complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, 1–22. 10.1002/aoc.4839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naz S.; Uddin N.; Ullah K.; Haider A.; Gul A.; Faisal S.; Nadhman A.; Bibi M.; Yousuf S.; Ali S. Homo- and Heteroleptic Zinc(II) Carboxylates: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Assessment of Their Biological Significance in in Vitro Models. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 511, 119849 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran E.; Gandin V.; Bertani R.; Sgarbossa P.; Natarajan K.; Bhuvanesh N. S. P.; Venzo A.; Zoleo A.; Glisenti A.; Dolmella A.; Albinati A.; Marzano C. Synthesis, Characterization and Cytotoxic Activity of Novel Copper(II) Complexes with Aroylhydrazone Derivatives of 2-Oxo-1,2-Dihydrobenzo[h]Quinoline-3-Carbaldehyde. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 182, 18–28. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indira S.; Vinoth G.; Bharathi M.; Shanmuga Bharathi K. Synthesis, Spectral, Electrochemical, in-Vitro Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Bisphenolic Mannich Base and 8-Hydroxyquinoline Based Mixed Ligands and Their Transition Metal Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1198, 126886 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.126886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan M. M.; Ahsan H. M.; Saha P.; Naime J.; Kumar Das A.; Asraf M. A.; Nazmul Islam A. B. M. Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Electrochemical Activity of (E)-N-(4 (Dimethylamino) Benzylidene)-4H-1,2,4-Triazol-4-Amine Ligand and Its Transition Metal Complexes. Results Chem. 2021, 3, 100115 10.1016/j.rechem.2021.100115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chebout O.; Trifa C.; Bouacida S.; Boudraa M.; Imane H.; Merzougui M.; Mazouz W.; Ouari K.; Boudaren C.; Merazig H. Two New Copper (II) Complexes with Sulfanilamide as Ligand: Synthesis, Structural, Thermal Analysis, Electrochemical Studies and Antibacterial Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1248, 131446 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand I.; Hilpert K.; Hancock R. E. W. Agar and Broth Dilution Methods to Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Antimicrobial Substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. C.; Liu J. W.; Wu X. Z.; Cao W.; Wang F.; Huang J. M.; Han Y.; Zhu X. Y.; Zhu B. Y.; Gan Q.; Tang X. Z.; Shen X.; Qin X. L.; Yu Y. Q.; Zheng H. P.; Yin Y. P. Comparison of Microdilution Method with Agar Dilution Method for Antibiotic Susceptibility Test of Neisseria Gonorrhoeae. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 1775–1780. 10.2147/IDR.S253811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta-ur-Rahman; Choudhary M. I.; Thomson W. J.. Bioassay Techniques for Drug Development; CRC Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kedare S. B.; Singh R. P. Genesis and Development of DPPH Method of Antioxidant Assay. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 412–422. 10.1007/s13197-011-0251-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevas E.; Mavroidi B.; Pelecanou M.; Hatzidimitriou A. G. Structurally Characterized Zinc Complexes of Flavonoids Chrysin and Quercetin with Antioxidant Potential. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 523, 120407 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams-Young D.; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Throssell K.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T. A.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Adamo C.; Cammi R.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 16, revision C. 01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Becke A. D. Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J.; Devlin F. J.; Chabalowski C. F.; Frisch M. J. Ab Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular Dichroism Spectra Using Density Functional Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. A 1994, 98, 11623–11627. 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R.; Binkley J. S.; Seeger R.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XX. A Basis Set for Correlated Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Calculation of the Electronic Spectra of Large Molecules. Rev. Comput. Chem. 2004, 20, 153–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lemilemu F.; Bitew M.; Demissie T. B.; Eswaramoorthy R.; Endale M. Synthesis, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Thiazole-Based Schiff Base Derivatives: A Combined Experimental and Computational Study. BMC Chem. 2021, 15, 67 10.1186/s13065-021-00791-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitew M.; Desalegn T.; Demissie T. B.; Belayneh A.; Endale M.; Eswaramoorthy R. Pharmacokinetics and Drug-Likeness of Antidiabetic Flavonoids: Molecular Docking and DFT Study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260853 10.1371/journal.pone.0260853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie T. B.; Sundar M. S.; Thangavel K.; Andrushchenko V.; Bedekar A. V.; Bouř P. Origins of Optical Activity in an Oxo-Helicene: Experimental and Computational Studies. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 2420–2428. 10.1021/acsomega.0c06079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3093. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche A. Software News and Updates Gabedit — A Graphical User Interface for Computational Chemistry Softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 32, 174–182. 10.1002/jcc.21600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby R. E.; Parker A. B. Using the PyMOL Application to Reinforce Visual Understanding of Protein Structure. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2016, 44, 433–437. 10.1002/bmb.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogana R.; Adhikari A.; Tzar M. N.; Ramliza R.; Wiart C. Antibacterial Activities of the Extracts, Fractions and Isolated Compounds from Canarium Patentinervium Miq. Against Bacterial Clinical Isolates. BMC Complementary Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 55 10.1186/s12906-020-2837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sonbati A. Z.; Diab M. A.; Morgan S. M.; Abou-Dobara M. I.; El-Ghettany A. A. Synthesis, Characterization, Theoretical and Molecular Docking Studies of Mixed-Ligand Complexes of Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II), Mn(II), Cr(III), UO2(II) and Cd(II). J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1200, 127065 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.127065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S.; Kumar U. Spectral and Magnetic Studies on Manganese(II), Cobalt(II) and Nickel(II) Complexes with Schiff Bases. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2005, 61, 219–224. 10.1016/j.saa.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismael M.; Abdel-Mawgoud A. M. M.; Rabia M. K.; Abdou A. Design and Synthesis of Three Fe(III) Mixed-Ligand Complexes: Exploration of Their Biological and Phenoxazinone Synthase-like Activities. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2020, 505, 119443 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I.; Wani W. A.; Saleem K. Empirical Formulae to Molecular Structures of Metal Complexes by Molar Conductance. Synth. React. Inorg., Met.-Org., Nano-Met. Chem. 2013, 43, 1162–1170. 10.1080/15533174.2012.756898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiya S.; Chowdhury S.; Haque L.; Das S. Spectroscopic, Photophysical and Theoretical Insight into the Chelation Properties of Fisetin with Copper (II) in Aqueous Buffered Solutions for Calf Thymus DNA Binding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1156–1169. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.08.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Zhang Y.; Xu Y. Modified Asynchronous Orthogonal Sample Design Scheme @ Job’s Method to Determine the Stoichiometric Ratio in the Molecular Association System. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1206, 127757 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kale K. B.; Shinde M. A. S. A.; Patil R. H.; Ottoor D. P. Exploring the Interaction of Valsartan and Valsartan-Zn(Ll) Complex with DNA by Spectroscopic and in Silico Methods. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2022, 264, 120329 10.1016/j.saa.2021.120329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirmizi S. A.; Hamid F.; Hamid M.; Wattoo S.; Sarwar S.; Nawaz A. Spectrophotometric Study of Stability Constants of Cimetidine – Ni (II) Complex at Different Temperatures. Arab. J. Chem. 2012, 5, 309–314. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby A. A.; Mohamed A. A. Determination of Stoichiometry and Stability Constants of Iron Complexes of Phenanthroline, Tris (2 - Pyridyl)- s - Triazine, and Salicylate Using a Digital Camera. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 3589–3595. 10.1007/s11696-020-01192-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastva A. N.; Singh N. P.; Shriwastaw C. K. In Vitro Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Binuclear Transition Metal Complexes of ONNO Schiff Base and 5-Methyl-2,6-Pyrimidine-Dione and Their Spectroscopic Validation. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9, 48–61. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan K.Spectral Methods in Transition Metal Complexes; Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]