Abstract

Premixed hydrogen–air explosion experiments were carried out in a 1000 mm × 50 mm × 10 mm half-open narrow channel, concerning with the influences of equivalence ratio and ignition position on explosion behaviors. Experimental phenomena were different from explosion in large space. The results indicated that when ignited at the closed end of the channel, three overpressure peaks appeared, caused by the rupture of the film, Helmholtz Oscillation, and the flame-acoustic interaction, respectively. As the equivalence ratio of the hydrogen–air mixtures varied from 0.6 to 1.6, the peak overpressure first increased and then decreased. The maximum peak overpressure occurred at ϕ = 1.2. The hydrogen flame would develop into the plane tulip structure without the influence of the end wall. With the ignition position moved to the open end, overpressure wave and flame oscillated significantly. Compared with other ignition positions, the minimum value of Pmax was obtained at IP950. Based on the explosion behaviors in the narrow channel, it was concluded that the closer the ignition was to the open end, the easier the oscillation was to be formed, the smaller the explosion hazard was.

Introduction

With the drying out of traditional energy and growth of global energy demand, environmental problems and greenhouse effect had become increasingly serious.1 Therefore, hydrogen is gaining more attention because of its long-lasting ability, high calorific value, and nonpolluting nature.2−6 However, hydrogen also has a larger flammable limit range and is prone to form the risk of pre-ignition and explosion.7−12 Once hydrogen leaks, it could trigger an explosion, especially in confined spaces, which might generate an overpressure of several atmospheres.13,14 Therefore, it is necessary to fully evaluate the safety problems in hydrogen utilization and prefect the explosion database, so as to guide the engineering practice.15,16

It has been established that many factors affected the explosion characteristics. The common influencing factors included obstacle,17,18 initial turbulence,19 vent burst pressure,20,21 ignition position,1,22,23 initial pressure,24 vent area,25 equivalence ratio,26,27 and so forth. Exploring the impact results of these factors brought a deeper understanding of hydrogen–air explosion. Among these factors, the equivalence ratio and ignition position were important factors affecting the overpressure and flame behaviors.

The effects of equivalence ratio and hydrogen concentration on explosion were essentially the effects of hydrogen content on explosion. Guo et al.23 conducted vented explosion experiments in a small cylindrical vessel, and the hydrogen concentration range was from 20 to 68 vol%. They concluded that the internal overpressure increased in the range of 20∼40 vol% hydrogen concentration. However, the internal overpressure decreased with the further increase in hydrogen concentration. By conducting hydrogen–air explosion experiments in a 2.3 m diameter spherical vessel with a hydrogen concentration range of 6–20 vol%, Kumar et al.28 concluded that the effect of venting on the peak overpressure was different at different hydrogen concentrations. The influences of the ignition position on the explosion overpressure were explored by Rui et al.1 with different hydrogen concentrations. The results showed that the ignition position had almost no influence on explosion overpressure at low concentrations. Yet, as the hydrogen concentration increased, the ignition position which could induce the maximum explosion pressure was uncertain. In order to study the combined influence of the equivalence ratio and the obstacle position on the overpressure of hydrogen–air explosion, Lv et al.29 performed deflagration experiments in a 5 L duct with the equivalence ratio from 0.6 to 1.4 under different obstacles. It was also found that the venting overpressure was hardly observed with the combined action of the obstacle position and equivalence ratio. Rui et al.30 carried out hydrogen–air explosion experiments in an enclosure of the same size as a 40-foot ISO container. It was proved that only when hydrogen concentration greater than 12 vol%, the maximum peak overpressure was induced by the obstacles. Bauwens et al.13 conducted hydrogen–air explosion with the hydrogen concentration ranging from 12 to 15 vol% under high turbulence. It was found that the maximum flame length grew with an increase in the hydrogen concentration. It was also found that between the lower and upper explosion limits, any hydrogen concentration could be reached in real life.31 Based on these studies, it was of considerable interest to study the phenomenon of hydrogen–air explosion in the poor and rich combustion states.

Besides, the ignition position was also an important influencing factor for hydrogen–air explosion. Hydrogen was prone to leak during transportation, while the ignition location was often hard to determine. Therefore, it was worth studying the hydrogen–air explosion at different ignition positions. Several research studies showed that the ignition position had important impacts on the explosion intensity, which are summarized in Table 1. It was generally believed that large overpressures could easily occur in small exhaust containers32 or large closed vessel.33 However, later, Bauwens et al.34 argued that the ignition location for the most severe explosion was often uncertain; it was influenced by many factors. There were no consistent conclusions for the effects of ignition on explosion behaviors, which needed further exploration. Table 1 reveals that with different shape and size of the duct, the ignition location had different effects. It was also found that the shape of the explosion containers was mostly square, cylindrical, spherical, and so forth, and the size was large. It was necessary to study in the innovative channel that was different from the conventional duct that different experimental results would be obtained. It was also the main innovation of this study.

Table 1. Previous Investigations of the Effects of the Ignition Location on Gas Explosions.

| authors | vessel shape | size/m3 | worst case | vented | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. | cylindrical | 2.52 × 12 | less impact | changed | (18) |

| Yang et al. | square | 0.12 × 1 | one side | no | (44) |

| Yang et al. | square | 0.12 × 1 | closed-end | end | (22) |

| Guo et al. | cylindrical | central | end | (23) | |

| Rui et al. | square | 0.53 | closed-end | end | (1) |

| Rui et al. | square | 0.53 | closed-end | end | (20) |

| Rocourt et al. | square | 0.153 | closed-end | changed | (45) |

| Zheng et al. | square | 0.12 × 1 | closed-end | end | (46) |

| Xiao et al. | square | 0.0822 × 0.53 | 5 cm off | no | (25) |

| Dai et al. | spherical | 0.02 | central | no | (47) |

Later, more and more research studies focused on the explosion in large L/D elongated narrow channels. The propagation of flame in elongated tubes received much attention since Chatelier35 studied the combustion of explosive gas. Diao and Wu et al.36,37 also studied the explosion behaviors of syngas in the narrow channel. It was found that the hydrodynamic instability could be avoided in a narrow channel, and burning gas could achieve stable combustion.38−40 At the same time, the explosion problem was studied in a narrow channel, which could effectively simplify the mathematical problems for easy calculation and understanding.41 The explosion behaviors of premixed gas in a narrow channel provided a better understanding of overpressure oscillation and flame propagation. In addition, the study of explosion behaviors in the narrow channel had great practical significance. The narrow gap between the piston and the cylinder wall in the internal combustion engine, portable power generation equipment, and fuel cells all had a similar volume structure with the narrow channel.42,43 Once hydrogen leakage occurred in these narrow spaces, the explosion risk would occur in the case of discharge or other ignition sources. Consequently, it was of great significance to study the hydrogen–air explosion behaviors in the narrow channel.

In this work, the experiments were carried out in a narrow channel to explore the effects of the equivalence ratio and ignition location on overpressure and flame behaviors of hydrogen. Based on the innovation of the duct, the influences of two important parameter variables on hydrogen–air explosion were analyzed. The experimental results were more valuable for practical application.

Experimental Section

As shown in Figure 1, the experiments were performed in a narrow channel. The cross-section of the channel was a narrow rectangle with an edge length of 50 and 10 mm. Also, the channel was 1000 mm long. The TP304 stainless-steel plate was at the right end of the channel. The gas inlet and pressure transducer were mounted at this stainless-steel plate. The position of the pressure sensor was appropriate because it had been shown that the position of the pressure sensor did not have effects on the overpressure variation.46 It was worth noting that the spark igniter used a 6 V direct current as the power source, and the position of the igniter changed according to the experimental conditions. The measurement rang of the pressure transducer was from −0.1 to 1 MPa, and the electrical signal was from 1 to 5 V.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of the experimental apparatus and the piping structure.

In the intake process, the outlet was sealed with a PVC film. The effect of PVC film on experimental results could be neglected.48 The hydrogen–air mixtures were filled with the combustion channel before ignition. According to the experimental condition, the mass flow controllers (D008-1F71FP Flow Readout Box) were employed to control the flow rate of hydrogen and air. The gas supply process lasted for 5 min. When the volume of filled gas was five times the volume of the combustion channel, the original gas in the vessel was exhausted, hydrogen and air mixed well. The inflation was then completed, and the mixtures within the channel were allowed to settle for 30 s before ignition.49−51 Later, ignition started, and the duration of the spark was about 1 ms, while the pressure and picture acquisition systems started to collect data. The shooting speed of the high-speed camera was 3000 f/s.

The equivalence ratio is utilized to quantify the fuel lean or rich condition of a fuel-oxidizer mixture. It can be defined by the following formula.

| 1 |

where A is the amount of oxidant in units of mol, referring to the air and not only the oxygen in the air. F is the amount of fuel in units of mol.

The experimental conditions are summarized in Table 2. Six equivalence ratios of 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, and 1.6 were taken into account. In particular, three ignition sources were installed for the case of ϕ = 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2, with the distances of 0, 500, and 950 mm from the closed end of the channel, respectively. To ensure the accuracy and repeatability of the experimental data, each condition was conducted at ambient temperature and pressure, and repeated at least three times.

Table 2. Summary of Experimental Conditions.

| test no. | equivalence ratio | chamber volume (L) | volume flow of hydrogen (L/min) | volume flow of air (L/min) | ignition position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.6 | 0.05 | 0.101 | 0.399 | IP0 |

| 2 | 0.8 | 0.05 | 0.126 | 0.374 | IP0, P500, IP950 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.148 | 0.352 | IP0, P500, IP950 |

| 4 | 1.2 | 0.05 | 0.168 | 0.332 | IP0, P500, IP950 |

| 5 | 1.4 | 0.05 | 0.185 | 0.315 | IP0 |

| 6 | 1.6 | 0.05 | 0.201 | 0.299 | IP0 |

Results and Discussion

Effects of the Equivalent Ratio on Explosion Overpressure and Flame Behaviors

Generally, because of the venting effect, the overpressure at the closed end was higher than that at the open end. From the perspective of explosion safety, the greater the overpressure, the greater the harm.46 Therefore, it was more meaningful to further analyze the overpressure profiles recorded at the closed end. In this study, the peak overpressure (i.e., Pmax) was defined as the maximum value among the overpressure peaks. As exhibited in Figure 2, the overpressure-time profiles had consistent change trend at different equivalence ratios, and three peaks (every overpressure peak was marked in Figure 2) were well identified. Figure 2a presents the overpressure profiles under the fuel lean condition, in which the overpressure peaks reduced and the oscillation behaviors diminished with the decrease of equivalence ratios. Figure 2b indicates the overpressure change in the fuel-rich condition. It was found that the overpressure peaks were relatively large with ϕ = 1.2 and 1.4. Still, as the equivalence ratios continued to increase, the peak overpressure was only around 0.5 bar.

Figure 2.

Overpressure profiles with different equivalence ratios for fuel-lean conditions (a) and fuel-rich conditions (b) at IP0.

The peak overpressure changed obviously with the change in the equivalence ratio.46Figure 3 shows the variation of the peak overpressure with the equivalence ratio. The peak overpressure increased first and then decreased as the combustion state changed from the fuel lean to rich condition at IP0. It was worth noting that in a large L/D narrow channel, the peak overpressure reached the summit at ϕ = 1.2. In contrast, Lv et al.29 found that the maximum peak overpressure occurred at ϕ = 1.0 in a 5 L combustion pipe. Li et al.52 concluded that the maximum peak overpressure still occurred at ϕ = 1.0 in a channel with a cross-section of 7 × 7 cm. Guo et al.31 addressed that the maximum peak overpressure of the hydrogen–air explosion occurred at ϕ = 1.6 in a small cylindrical container. Zheng et al.46 carried out the premixed hydrogen–air deflagration experiment and found that peak overpressure reached the summit at ϕ = 1.25. This study discovered that the maximum peak overpressure appeared at ϕ = 1.2. Upon investigating its reason, it was found that the equivalence ratio and the reaction temperature showed a strong correlation.7,53 The combustion theory suggested that when the equivalence ratio was slightly greater than 1.0, the maximum flame temperature appeared,54 resulting in the increase in the flame combustion rate, flame propagation speed, and peak overpressure. This was not the main objective of this work but to provide a new idea for studying the effect mechanism of the equivalent ratio in the explosion process.

Figure 3.

Peak overpressure under various equivalence ratios at IP0.

The equivalence ratio had important influence on laminar flame speed, temperature, and pressure in the explosion. The relationship between laminar flame speed, temperature, and pressure can be expressed by the following formula37,55,56

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where SL0, T0, P0 are laminar flame speed, temperature, and pressure in the reference state. BM, B2, and ϕM are constants determined by fuel type, ϕ is the equivalence ratio, and m and n are the temperature index and pressure index. m and n are functions of the equivalence ratio, which are expressed as follows:

| 6 |

| 7 |

Because the hydrogen flame was light blue and spreads fast, it was difficult to determine the flame front location for fuel-lean conditions.57 Therefore, when analyzing the flame images of the combustion process, the fuel-rich conditions before and after ϕ = 1.2 were adopted. Also, the images were subjected to certain exposure processing. Figure 4 provides the flame diagrams of the hydrogen–air mixtures with different equivalent ratios. The flame images were selected from a representative batch of several dozens of images taken using a high-speed camera. It could be seen from the figures that the hydrogen–air flame was divided into a light blue region and a yellow region. The blue region was formed by the chemical reaction of hydrogen in the air. In this experiment, the yellow flame was caused by the combustion of impurity particles in the channel at high temperatures, mainly including dust particles remaining in the channel and film fragments produced by the rupture of PVC film.58 Because of the limitation of experimental conditions, these could not be completely avoided.

Figure 4.

Flame propagation images under ϕ = 1.0 (a), 1.2 (b), 1.4 (c), and 1.6(d).

Obviously, as the equivalence ratio increased, the flame front became clearer. Therefore, taking ϕ = 1.6 as an example, the structural evolution process of flame was analyzed. After ignition, the flame began to expand freely in a hemispherical shape, seeing t = 1.00 ms. After that, because of the restriction of the channel wall, the flame was stretched into a finger shape, and it could be visually observed at t = 2.00 ms. At t = 4.67 ms, the flame skirt started to contact the upper and lower walls, the flame front became a flat type, and the flame surface area decreased. Between t = 5.33 ms and t = 6.33 ms, the shape of the flame was distorted and the front of the flame was reversed. In this study, it was called the plane tulip flame, which was different from the tulip flame that appeared in the cube pipe. From the images, it could only roughly judge the speed of flame propagation. The corresponding flame front speed is shown in Figure 5. The flame propagation to the right was taken as the positive direction, and its speed and flame front position were positive, while the opposite propagation to the left was negative. The right end of the channel was the closed end.

Figure 5.

Flame front speed at different equivalence ratios.

The flame speed mentioned in the study was the flame front speed, which was figured out using the following formula.

| 8 |

where V is the speed of flame front in units of m/s, dx is the displacement of flame front in a short time in units of cm, and dt is the time of flame propagation in units of ms. The change trend of the flame front speed was basically the same under different equivalent ratios. The maximum speed appeared earliest at ϕ = 1.2, and the flame took the least time to pass through the channel. In other operating conditions, the maximum speed was not much different from that at ϕ = 1.2. However, the time to reach the maximum speed was later. The combustion was relatively weak at ϕ = 1.0, so the flame front speed became slower at this time. In the case of large equivalent ratios (i.e., ϕ = 1.4 or 1.6), the reason for this situation was the violent oscillation in the explosion. As shown in Figure 5, the flame had rightward propagation in the process of propagation to the left, and the speed to the right was larger, which made the flame propagation distance and propagation time longer.

The overpressure and flame behaviors had certain coupling relationships in the explosion. The overpressure profiles and flame images of IP0 were analyzed with ϕ = 1.2, as shown in Figure 6. Because ϕ = 1.2 was a special condition, the maximum peak overpressure appeared in this condition. Three overpressure peaks P1, P2, and P3 could be obviously observed when the hydrogen–air mixtures were ignited. This was in line with the experimental results of Rocourt et al. and Zheng et al.45,46 The first peak P1 was caused by the rupture of PVC film. Because of the appearance of P1, the channel was completely half-open. The flame was in the finger shape, the flame surface area increased, and the overpressure rose. With the flame skirt touching the upper and lower walls, the flame surface area decreased until a flat flame formed. With the combustion area reduced, the overpressure dropped.59 It was generally accepted that the formation of P2 was due to the emission of burning gas60 or the external explosion.23,45,61,62 However, this conclusion was denied by Zheng et al.46 By means of the analysis of flame front evolution and overpressure profiles, it was found that the overpressure reached P2 just before the flame left the channel. At present, the reasonable explanation for the formation of P2 was that it was caused by Helmholtz Oscillation.20,25,28 Studies had shown that Helmholtz oscillation only occurred in explosion pipelines with vents.63 It was a dynamic response caused by a sharp change of pressure in the channel.64 After breaking the film, the flame promoted the combustion gas to rush out of the channel quickly, and then refluxed quickly, triggering Helmholtz oscillation.1,21

Figure 6.

Overpressure profile under ϕ = 1.2 at IP0.

The accelerating flame acted as a piston and generated compression waves in the unreacted gas.65 A large number of unreacted gas was compressed at the flame front, resulting in a narrow overpressure peak on the scale of the flame width.65 This overpressure peak was the dominant peak in the channel, and the flame was in the formation stage of the tulip flame at this time. The third overpressure peak (i.e., P3) was the result of the combined action of the flame and the acoustic wave. Yang et al.22 and Bauwens et al.19 also pointed out that the interaction of the flame with acoustic wave promoted the generation of the overpressure peak. Tang et al.66 also attributed the third overpressure peak in the experiment to the coupling effect of flame and sound.

Effects of the Ignition Position on Explosion Overpressure and Flame Behaviors

The ignition position was considered to be an important factor affecting hydrogen–air explosion. Xu et al.67 pointed out that the ignition location determined the intensity of the explosion. Yang et al.22 found that in a half-open square duct, the ignition location was closer to the closed end of the duct, and the explosion was more intense. Guo et al.23 experimentally studied that the overpressure was different with different ignition positions.

In order to make the experimental results more common, the effects of the ignition position on hydrogen–air explosion were investigated under ϕ = 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2, respectively. Figure 7 shows the difference in the overpressure profiles at different ignition positions. At the same ignition position, the overpressure change trend was basically consistent for different equivalence ratios. In general, with the increase in the equivalent ratio, the overpressure peaks appeared earlier and became more obvious. At IP0, there was no overpressure soaring phenomenon. Also, the overpressure wave did not show a significant oscillation. Because the flame directly spread to the opening and vented, the overpressure wave in the channel was not enough to maintain the Rayleigh Taylor instability that caused the oscillation.44 At IP500, the overpressure wave showed a low-frequency oscillation. This oscillation lasted about 5 ms. There was also an overpressure oscillation lasting about 40 ms at IP950, that is, a multipeak pressure oscillation distribution.23 This finding was consistent with previous studies on hydrocarbon fuels.68,69 In the flame propagation process, the Rayleigh Taylor instability induced by the Helmholtz oscillation was observed. The RT instability interacted with the Helmholtz oscillation in the same phase, which could significantly increase the amplitude and time of oscillation.45

Figure 7.

Overpressure profiles for ignitions at IP0 (a), IP500 (b), IP950 (c) with ϕ = 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that the ignition position significantly affected the duration of Helmholtz oscillation,70 and the duration of oscillation was the longest at IP950. The results were explained as follows: once the exhaust rate exceeded the volume production rate after breaking the film, the overpressure in the channel would decrease, and because of the inertial effect of gas flow in the exhaust process, a certain negative pressure would be formed. In order to balance the negative pressure, the gas would flow back. Meanwhile, the unburned gas in the channel continued to burn and provided energy for the Helmholtz oscillation.71 The interaction of flame and sound also controlled the periodic oscillation by affecting the RT instability. This explanation was consistent with the experiment results of Guo et al.23 Furthermore, the oscillation time of middle ignition was less than that of open end ignition, because there was less-burning mixtures left in the channel after the film breaking at IP500.

Figure 8 shows the flame propagation images at different ignition positions with ϕ = 1.0. The case of ignition at the closed end of the channel had been mentioned above. When the ignition was in the middle of the channel (IP500), the flame could propagate to both ends of the channel. First, the flame at the right end developed from the hemispherical shape (see t = 1.00 ms) to the finger shape (see t = 2.99 ms). As the flame continued to propagate toward the right end, it evolved into a flat flame. It could be noticed that because of the combination of the flame and the sound of the explosion, the front edge of the flat flame began to fold.72 This phenomenon could be seen as a precursor to the formation of plane tulip flame. Only hemispherical and finger-shaped fronts were seen on the left flame. Because the channel at the left end lacked tightness, the flame would be discharged directly. The flame front speed was slow at IP950. Also, the flame showed intensive oscillation, which was in line with the overpressure change trend. As shown in Figure 8c, compared to ignition at other locations, the flame front became unclear at IP950. This indicated that the explosion intensity was weakened.

Figure 8.

Flame propagation images at IP0 (a), IP500 (b), and P950 (c).

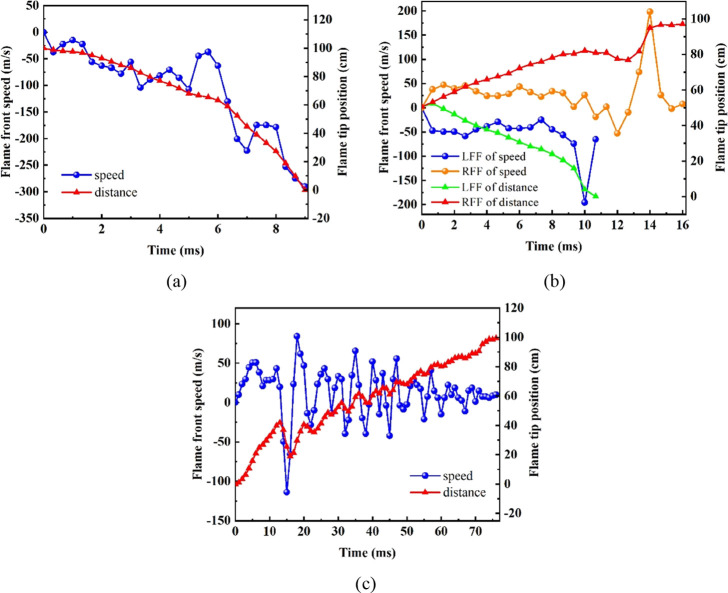

As can be seen from Figure 9a, the flame front speed increased as the flame propagated toward the opening. At t = 5.67 ms, the flame front speed began to rise sharply. It was found that this phenomenon occurred after the first overpressure peak appeared, which might be caused by the rupture of PVC film. As shown in Figure 10b, the flame at IP500 spread to both ends of the channel. The flame propagating to the open end was called the left flame (LFF), and the flame propagating to the closed end was named the right flame (RFF). The change trend of speed at both ends was consistent. In the figure, the time that the RFF reached the maximum speed was later than the LFF. By comparing with the overpressure profiles, it was found that the time to reach the peak speed of the RFF was consistent with the time to reach the second overpressure peak. Therefore, the peak speed of the RFF was likely caused by the Helmholtz oscillation. Moreover, a powerful overpressure wave was accumulated at the right end, and it made the speed increment larger. In Figure 9c, it could be seen that the flame tip position and speed oscillated significantly at IP950, which were consistent with overpressure behavior. In addition, the flame propagated much faster at the closed end (IP0) than that the ignition at other locations, as shown in Figure 9. This was due to the role of the wall effect in explosion, and the influence of heat losses and wall compression would lead to the difference in the flame speed.73 The propagation speed of flame was accelerated by the flow inside the burned zone caused by wall compression.73 The interaction with the wall was reduced when the flame propagated to the open end, the heat losses were small, and the speed increased accordingly.

Figure 9.

Flame front speed and flame tip position for IP0 (a), IP500 (b), and IP950 (c) with ϕ = 1.0.

Figure 10.

Coupled relationship among flame tip position, flame front speed (a), and flame structure (b) at IP950.

The overpressure profiles, flame propagation images, and speed variation curves all showed extremely prominent oscillation at IP950. Here, this oscillation process was analyzed in detail from Figure 10. After ignition, the overpressure wave generated at the open end, and it made the flame advanced to the right end of the channel, and the flame front speed increased. Later, the PVC film was broken, some burning gas and burning products were discharged outward due to inertia. This led to a negative overpressure in the narrow channel, thus causing the reflow phenomenon. The flame propagating to the right was pulled back, formed point A. After that, the flame continued to maintain positive acceleration, propagating to the right forming point B. Also, this process was synchronized with the reduction of the flame area.20 Because of the presence of the RT instability and the turbulence phenomenon caused by the change in the flame morphology, the alternating propagation of the flame to the right and left continued many times. The flame front speed varied spirally with the flame tip position, as shown in Figure 10. It was affected by the exchange of pressure energy and fluid kinetic energy that was caused by the interaction between the flame front and sound wave.74

Maximum explosion pressure was an important index to measure explosion power.75Figure 11 exhibits the variation of the peak overpressure with the ignition position. As for the influences of the ignition position on explosion, there was no consistent conclusion about the worst case (i.e., the ignition position leading to the maximum peak overpressure). In this narrow channel, the maximum peak overpressure occurred at IP500. Rocourt et al.45 proved that central ignition resulted in high overpressure by conducting hydrogen–air explosion experiments in a small, vented vessel. This work concluded that the best case (i.e., the minimum Pmax) occurred at IP950, and the worst case did not always occur at IP0. This was consistent with the conclusion presented by Yang et al. that the open end reduced the flame overpressure.44

Figure 11.

Maximum peak overpressure for ignitions at IP0, IP500, and IP950.

Conclusions

In this study, the effects of equivalence ratios and ignition positions on the overpressure and flame behaviors in the hydrogen–air explosion were investigated. The explosion experiments were performed in a narrow channel. The experimental variables included six equivalent ratios, that is, ϕ = 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and three ignition positions, that is, IP0, IP500, and IP950. The main conclusions drawn were as follows.

-

(1)

There were three overpressure peaks in the overpressure profiles measured in the narrow channel. P1 was caused by the flame breaking through the PVC film at the opening. The formation of P2 was due to the Helmholtz oscillation, and P3 was the result of the combined action of the overpressure wave and sound wave.

-

(2)

The explosion power was the strongest at ϕ = 1.2 in the narrow channel. In this state, the peak pressure was the largest and the flame front speed was the fastest. As the equivalence ratio increased to 1.2, the overpressure peaks increased and appeared earlier.

-

(3)

As the ignition position moved to the open end of the channel, the oscillation of the overpressure and flame behavior became more and more obvious. At IP950, there was an overpressure oscillation lasting about 40 ms, the pressure showed a multi-peak distribution, and the flame front speed varied spirally with position.

-

(4)

The maximum overpressure increased slowly and then decreased rapidly with the ignition position moving to the open end. In the narrow channel, the explosion power was the largest at IP500, and the power was the smallest at IP950. This had an important reference value for hydrogen application in practical engineering.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51774115, 51904094).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Rui S.; Wang C.; Luo X.; Jing R.; Li Q. External explosions of vented hydrogen-air deflagrations in a cubic vessel. Fuel 2021, 301, 121023 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Law C. K. Combustion at a crossroads: Status and prospects. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2007, 31, 1–29. 10.1016/j.proci.2006.08.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai S. Hydrogen electrical energy storage by high-temperature steam electrolysis for next-millennium energy security. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 21358–21370. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.09.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verhelst S.; Wallner T. Hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 490–527. 10.1016/j.pecs.2009.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acar C.; Dincer I. The potential role of hydrogen as a sustainable transportation fuel to combat global warming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 3396–3406. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.10.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Li Q.; Wang L.; Guo J.; Li C.; Lu S. Experimental investigation of detonation propagation in hydrogen-air mixtures in a tube filled with bundles. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2019, 102, 316–324. 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2018.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Yuan Y.; Yan X.; Malekian R.; Li Z. A study on a numerical simulation of the leakage and diffusion of hydrogen in a fuel cell ship. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2018, 97, 177–185. 10.1016/j.rser.2018.08.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmipathy S.; Skjold T.; Hisken H.; Atanga G. Consequence models for vented hydrogen deflagrations: CFD vs. engineering models. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 8699–8710. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.08.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molkov V.Fundamentals of hydrogen safety engineering; Bookboon. com, 2012; pp 978–987. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerketvedt D.; Bakke J. R.; Wingerden K. V. Gas explosion handbook. J. Hazard. Mater. 1997, 52, 1–150. 10.1016/S0304-3894(97)81620-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q.; Luo Z.; Wang T.; Xie C.; Deng J. The flammability limits and explosion behaviours of hydrogen-enriched methane-air mixtures. Exp. Therm. Fluid. Sci. 2021, 126, 110395 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2021.110395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Jiao F.; Huang Q.; Cao W.; Cao X. Experimental and numerical studies on the closed and vented explosion behaviors of premixed methane-hydrogen/air mixtures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 159, 113907 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.113907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens C. R.; Chaffee J.; Dorofeev S. B.. 22nd international colloquium on the dynamics of explosions and reactive systems, 2009.

- Bauwens C. R.; Chaffee J.; Dorofeev S. Experimental and numerical study of methane-air deflagrations in a vented enclosure. Fire Saf. Sci. 2008, 9, 1043–1054. 10.3801/IAFSS.FSS.9-1043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X.; Xiu G.; Wu S. Experimental study on the explosion characteristics of methane/air mixtures with hydrogen addition. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 120, 741–747. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Razus D.; Mitu M.; Giurcan V.; Movileanu C.; Oancea D. Additive influence on maximum experimental safe gap of ethylene-air mixtures. Fuel 2019, 237, 888–894. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.10.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Yu M.; Zheng K.; Luan P.; Han S. An experimental study on premixed syngas/air flame propagating across an obstacle in closed duct. Fuel 2020, 267, 117200 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Rui S.; Luo X.; Wang C. Ceiling-vented deflagrations of a hydrogen-air mixture in a 75 m3 container. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 31916–31925. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.07.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens C. R.; Dorofeev S. B. Effect of initial turbulence on vented explosion overpressures from lean hydrogen–air deflagrations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 20509–20515. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.04.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rui S.; Wang C.; Luo X.; Li Q.; Zhang H. Experimental study on the effects of ignition location and vent burst pressure on vented hydrogen-air deflagrations in a cubic vessel. Fuel 2020, 278, 118342 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rui S.; Guo J.; Li G.; Wang C. The effect of vent burst pressure on a vented hydrogen–air deflagration in a 1 m3 vessel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 21169–21176. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.09.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Zheng L.; Wang C.; Wang X.; Jin H.; Fu Y. Effect of ignition position and inert gas on hydrogen/air explosions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8820–8833. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.12.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Sun X.; Rui S.; Cao Y.; Hu K.; Wang C. Effect of ignition position on vented hydrogen–air explosions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 15780–15788. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.09.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitu M.; Giurcan V.; Razus D.; Oancea D. Influence of initial pressure and vessel’s geometry on deflagration of stoichiometric methane–air mixture in small-scale closed vessels. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 3828–3835. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b04450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.; Wang Q.; Shen X.; An W.; Duan Q.; Sun J. An experimental study of premixed hydrogen/air flame propagation in a partially open duct. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 6233–6241. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitu M.; Giurcan V.; Razus D.; Oancea D. Inert gas influence on propagation velocity of methane-air laminar flames. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 196–200. 10.37358/RC.18.1.6073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitu M.; Razus D.; Schroeder V. Laminar Burning Velocities of Hydrogen-Blended Methane–Air and Natural Gas–Air Mixtures, Calculated from the Early Stage of p (t) Records in a Spherical Vessel. Energies 2021, 14, 7556. 10.3390/en14227556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R. K.; Dewit W. A.; Greig D. R. Vented explosion of hydrogen-air mixtures in a large volume. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1989, 66, 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Lv X.; Zheng L.; Zhang Y.; Yu M.; Su Y. Combined effects of obstacle position and equivalence ratio on overpressure of premixed hydrogen–air explosion. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 17740–17749. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.07.263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rui S.; Wang C.; Wan Y.; Luo X.; Zhang Z.; Li Q. Experimental study of end-vented hydrogen deflagrations in a 40-foot container. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 15710–15719. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.04.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Liu X.; Wang C. Experiments on vented hydrogen-air deflagrations: the influence of hydrogen concentration. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2017, 48, 254–259. 10.1016/j.jlp.2017.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponizy B.; Leyer J. C. Flame dynamics in a vented vessel connected to a duct: 2. Influence of ignition site, membrane rupture, and turbulence. Combust. Flame 1999, 116, 272–281. 10.1016/S0010-2180(98)00039-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGood R.; Chatrathi K. Comparative analysis of test work studying factors influencing pressures developed in vented deflagrations. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 1991, 4, 297–304. 10.1016/0950-4230(91)80043-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens C. R.; Chaffee J.; Dorofeev S. Effect of ignition location, vent size, and obstacles on vented explosion overpressures in propane-air mixtures. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2010, 182, 1915–1932. 10.1080/00102202.2010.497415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelier L. Recherches sur la combustion des mélanges gazeux explosifs. J. Phys. Theor. Appl. 1885, 4, 59–84. 10.1051/jphystap:01885004005901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diao S.; Wen X.; Guo Z.; He W.; Deng H.; Wang F. Experimental study of explosion dynamics of syngas flames in the narrow channel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 17808–17820. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.03.258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Wen X.; Guo Z.; Zhang S.; Deng H.; Wang F. Experimental study on the propagation characteristics of hydrogen/methane/air premixed flames in a narrow channel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 6377–6387. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdyumov V. N.; Matalon M. Flame acceleration in long narrow open channels. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 865–872. 10.1016/j.proci.2012.07.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matalon M. Flame dynamics. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2009, 32, 57–82. 10.1016/j.proci.2008.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivashinsky G. I. Some developments in premixed combustion modeling. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2002, 29, 1737–1761. 10.1016/S1540-7489(02)80213-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdyumov V. N.; Matalon M. Influence of heat-loss on compressibility-driven flames propagating from the closed end of a long narrow duct. Combust. Flame 2020, 214, 1–13. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2019.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Galisteo D.; Kurdyumov V. N.; Ronney P. D. Analysis of premixed flame propagation between two closely-spaced parallel plates. Combust. Flame 2018, 190, 133–145. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2017.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov M.; Grune J. Experiments on combustion regimes for hydrogen/air mixtures in a thin layer geometry. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 8727–8742. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.11.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Yu M.; Zheng K.; Wan S.; Wang L. A comparative investigation of premixed flame propagation behavior of syngas-air mixtures in closed and half-open ducts. Energy 2019, 178, 436–446. 10.1016/j.energy.2019.04.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocourt X.; Awamat S.; Sochet I.; Jallais S. Vented hydrogen–air deflagration in a small enclosed volume. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 20462–20466. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.03.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L.; Zhu X.; Wang Y.; Li G.; Yu S.; Pei B.; Wang Y.; Wang W. Combined effect of ignition position and equivalence ratio on the characteristics of premixed hydrogen/air deflagrations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 16430–16441. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.06.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai T.; Zhang B.; Liu H. On the explosion characteristics for central and end-wall ignition in hydrogen-air mixtures: A comparative study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 30861–30869. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.06.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M.; Zheng K.; Zheng L.; Chu T.; Guo P. Scale effects on premixed flame propagation of hydrogen/methane deflagration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 13121–13133. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.07.143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z.; Deng H.; Zhao W.; Wen X.; Dong J.; Wang F.; Chen G.; Guo Z. Experimental study on explosion characteristics of premixed syngas/air mixture with different ignition positions and opening ratios. Fuel 2020, 279, 118426 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.; Wen X.; Zhang S.; Wang F.; Pan R.; Sun Z. Experimental study on the combustion-induced rapid phase transition of syngas/air mixtures under different conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 19948–19955. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.05.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X.; Wang M.; Su T.; Zhang S.; Pan R.; Ji W. Suppression effects of ultrafine water mist on hydrogen/methane mixture explosion in an obstructed chamber. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 32332–32342. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.10.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Sun X.; Lu S.; Zhang Z.; Wang X.; Han S.; Wang C. Experimental study of flame propagation across a perforated plate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 8524–8533. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.03.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clanet C.; Searby G. On the “tulip flame” phenomenon. Combust. Flame 1996, 105, 225–238. 10.1016/0010-2180(95)00195-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams F. A.Combustion Theory; CRC Press, 2018.

- Poinsot T.; Veynante D.. Theoretical and numerical combustion; RT Edwards, Inc., 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Turns S. R.Introduction to combustion; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hu P.; Zhai S. Experimental study of lean hydrogen-air mixture combustion in a 12 m3 tank. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 133, 103633 10.1016/j.pnucene.2021.103633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Xue Q.; Zuo H.; She X.; Wang J. Effects of CO2 and N2 dilution on the characteristics and NOX emission of H2/CH4/CO/air partially premixed flame. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 15909–15921. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.03.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emami S.; Mazaheri K.; Shamooni A.; Mahmoudi Y. LES of flame acceleration and DDT in hydrogen–air mixture using artificially thickened flame approach and detailed chemical kinetics. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 7395–7408. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.03.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavetti M.; Carcassi M. Maximum overpressure vs. H2 concentration non-monotonic behavior in vented deflagration. Experimental results. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 7494–7503. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.03.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolias I. C.; Stewart J. R.; Newton A.; Keenan J.; Makarov D.; Hoyes J. R.; Molkov V.; Venetsanos A. G. Numerical simulations of vented hydrogen deflagration in a medium-scale enclosure. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2018, 52, 125–139. 10.1016/j.jlp.2017.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. G.; Fairweather M.; Tite J. P. On the mechanisms of pressure generation in vented explosions. Combust. Flame 1986, 65, 1–14. 10.1016/0010-2180(86)90067-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Wang C.; Li Q.; Chen D. Effect of the vent burst pressure on explosion venting of rich methane-air mixtures in a cylindrical vessel. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2016, 40, 82–88. 10.1016/j.jlp.2015.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao T.; Wang C.; Yan W.; Ren W.; Yuen K. Experimental investigation on the dynamic responses of vented hydrogen explosion in a 40-foot container. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19229–19243. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.03.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov M. F.; Kiverin A. D.; Yakovenko I. S.; Liberman M. A. Hydrogen–oxygen flame acceleration and deflagration-to-detonation transition in three-dimensional rectangular channels with no-slip walls. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 16427–16440. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.08.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z.; Li J.; Guo J.; Zhang S.; Duan Z. Effect of vent size on explosion overpressure and flame behavior during vented hydrogen–air mixture deflagrations. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 361, 110578 10.1016/j.nucengdes.2020.110578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Ni X.; Su X.; Xiao B.; Luo Y.; Zhang F.; Weng C.; Yao C. Experimental and numerical investigation on effects of pre-ignition positions on knock intensity of hydrogen fuel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 26631–26645. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.05.154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L.; Su Y.; Li G.; Wang Y.; Zhu X.; Wang Y.; Yu M. Effect of ignition position on deflagration characteristics of hydrogen/methane/air premixed gas. CIESC J 2017, 68, 4874–4881. 10.11949/j.issn.0438-1157.20170369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. G.; Lü X. S.; Zheng K.; Yu M.; Pan R.; Zhang Y. Influence of ignition position on overpressure of premixed methane-air deflagration. CIESC J 2015, 66, 2749–2756. 10.11949/j.issn.0438-1157.20141789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Wang X.; Guo J.; Zhang J.; Zhang S. Effect of concentration and ignition position on vented methane–air explosions. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020, 68, 104334 10.1016/j.jlp.2020.104334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y.; Xing H.; Sun S.; Wang M.; Li B.; Xie L. Experimental study of the effects of vent area and ignition position on internal and external pressure characteristics of venting explosion. Fuel 2021, 300, 120935 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey A. K.; Koyama Y.; Yoon S. H.; Hashimoto N.; Fujita O. Range of “complete” instability of flat flames propagating downward in the acoustic field in combustion tube: Lewis number effect. Combust. Flame 2020, 216, 326–337. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2020.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov V.; Akkerman V.; Fru G.; Petchenko A.; Eriksson L. Flame acceleration in the early stages of burning in tubes. Combust. Flame 2007, 150, 263–276. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2007.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Searby G. Acoustic instability in premixed flames. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1992, 81, 221–231. 10.1080/00102209208951803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giurcan V.; Razus D.; Mitu M.; Oancea D. Prediction of flammability limits of fuel-air and fuel-air-inert mixtures from explosivity parameters in closed vessels. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 34, 65–71. 10.1016/j.jlp.2015.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]