Abstract

PROTACs represent a promising modality that has gained significant attention for the treatment of cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and so forth. Due to limited structural information of the POI-PROTAC-E3 ligase ternary complex, the discovery of active PROTACs relies on the screening of diversity-oriented PROTAC libraries. VH032 amine is a key building block for the synthesis of VHL E3 ligase-based PROTACs. To construct VHL PROTAC libraries rapidly, the availability of VH032 amine is crucial. In this paper, we report a column chromatography-free process which enables the production of 42.5 g of VH032 amine hydrochloride in 65% overall yield with 97% purity in a week.

Introduction

Proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology was initially described in 20011 and has recently attracted significant attention in the treatment of cancer, immune disorders, viral infections, neurodegenerative diseases, and so on.2 It was estimated that there will be a dozen PROTACs under different stages of clinical development by the end of 2021.3 A PROTAC compound is a heterobifunctional small molecule composed of a protein-of-interest (POI) warhead, an E3 ligase recruiter, and a linker that connects them together. Recruitment of the E3 ligase to the POI results in ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the POI via proteasomal machinery.

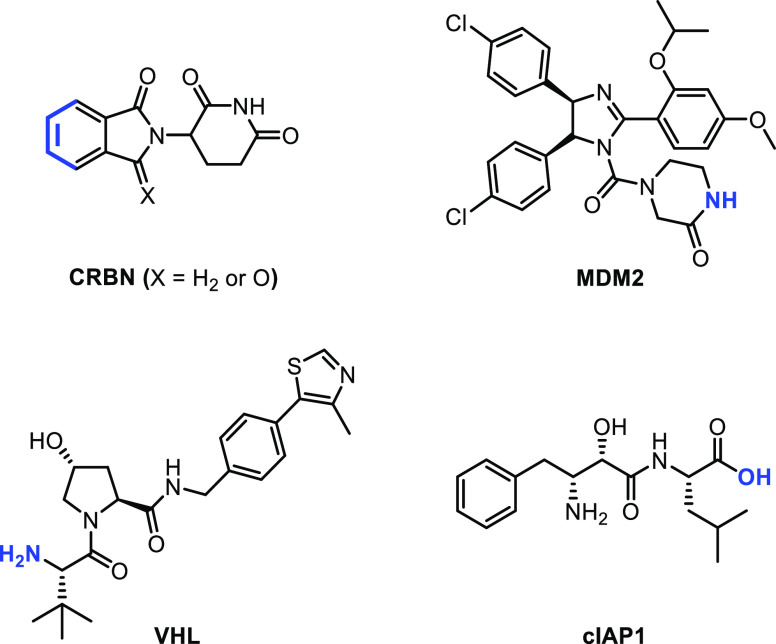

Up to date, PROTACs targeting 50 proteins have been successfully developed;4 however, E3 ligase was limited mainly to four types: cereblon (CRBN), von Hippel Lindau (VHL), mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2), and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (cIAP1). The representative ligands are illustrated in Scheme 1, where the blue-colored atoms indicate the linking position to linkers. Of these four types of E3 ligases, CRBN and VHL are widely used in the design of PROTACs due to their efficacy and broad expression in cancer cells. Although most clinical drugs are reported with CRBN ligands,5 VHL ligands have their advantages. VHL ligands are more stable since thalidomide-based PROTACs have been reported to decompose even in a mild PBS buffer.6,7 In addition, VHL E3 ligase has different expression levels in different cells. Taking advantage of the low VHL expression in platelets, Zheng and Zhou’s groups were able to develop a VHL ligand-based BCL-XL PROTAC that was much less toxic to platelets than its parent compound and is in phase I clinical trials.8

Scheme 1. Chemical Structures of Representative E3 Ligase Ligands.

CRBN ligands can be synthesized from commercially available starting materials within a few steps or are commercially available at affordable prices. However, the synthetic routes for VHL ligands are relatively lengthy. The price of VH032 amine from commercial suppliers is high, with 1 g costing an estimated ∼$3,100.9 Due to limited structural information of the POI-PROTAC-E3 ligand ternary complex,10 the discovery of potent PROTACs largely relies on the screening of diversity-oriented PROTAC libraries by adjusting the POI warhead linking position, linker types, linker lengths, rigidity, and so on. Therefore, the rapid access of this important ligand on a large scale and in an economic manner is essential in the drug discovery of VHL-based PROTACs.

Results and Discussion

The retro-synthetic analysis reveals that VH032 amine is composed of four building blocks: leucine (A), proline (B), benzyl amine (C), and thiazole (D) (Scheme 2). Three linear and one convergent synthetic strategy can be applied to access VH032 amine. Although synthetic routes of i-a and i-b were reported by Arvinas and GlaxoSmithKline in their patent applications,11,12 it is preferred that the coupling between C and D occurs prior to amide bond formation (route i-c) to avoid epimerization of the chiral amino acids in the presence of base under elevated temperatures.

Scheme 2. Retro-Synthesis Analysis of VH032 Amine.

Scheme 3 summarizes the published methods toward the construction of (4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)methanamine (building blocks C + D, compound 4) and the methods we used in our process. In the same paper published by Buckley et al., two methods were described to synthesize compound 4. First, TEOC-protected 4-bromo-benzyl amine (1) and 4-methylthiazole-5-carboxylic acid (2) reacted via a palladium-catalyzed decarboxylation C–N coupling reaction under harsh microwave conditions at 170 °C; however, the yield of intermediate 3 was low (44%). The second method required the combination of CoCl2 and NaBH4 to reduce the CN group.13 The synthesis worked well in a small-scale reaction (<1 g), but when we tried a 10 g scale reaction, the reaction mixture turned into clay and was extremely difficult to filter even though a diatomite pad was used, thus resulting in only <30% yield. Kymera Therapeutics reported a Suzuki-coupling reaction of Boc-protected benzyl amine boronic acid (8) and 5-bromo-4-methylthiazole (9) in their patent application,14 while Han et al. and Steinebach et al. published the Pd(OAc)2-catalyzed direct Heck coupling of boc-protected 4-bromo-benzyl amine (11) and 4-methylthiazole (6) to connect C and D. In comparison with Kymera’s method, the Heck coupling introduced by Han et al. was reported to have the following advantages: (1) the starting materials and the catalyst are cheap and (2) the reaction features a short reaction time and high yield.15 Therefore, we investigated this coupling condition for potential large-scale synthesis. We first tried the Heck coupling at 90 °C, as reported by Han et al. The reaction worked well in a small-scale reaction (<1 g of the bromide 11), but the reaction was very sluggish in a 10 g scale reaction. Since only 50% conversion was observed after heating overnight, we increased the reaction temperature to 130 °C as also reported by Steinebach et al.(16) To our delight, the reaction was completed within 4 h. To test the stability of the product, a portion of the reaction mixture was further heated overnight and no significant side-products were formed. It was worth noting that the reaction should be monitored with a UV detector at the wavelength of 214 nm until >90% bromide 11 was consumed, as it had a weak UV absorbance at 254 nm. We used HCl to remove the Boc-protection group because when TFA was used, the resulting product was a sticky syrup containing significant amounts of residual TFA even after deep concentrations; on the contrary, the HCl salt of 4 can form a fine solid and precipitate out in >95% purity without the necessity of further purification.

Scheme 3. Published Methods to Synthesize Compound 4 and the Methods Used in Our Process.

As analyzed in Scheme 2, linear or convergent synthesis could be applied to assemble the building blocks from the key intermediate 4 (detailed in Scheme 4). In the linear synthetic route, compound 4 was coupled with proline and leucine sequentially to give Boc-VH032 amine (17); while in the convergent synthetic route, leucine and proline were coupled first and then coupled with compound 4. Both routes required three steps, but the advantage of the convergent synthetic route was that the synthesis of benzyl amine and leucine–proline coupling can be carried out simultaneously. We investigated these routes several times. In terms of product yield and purity, the two routes were comparable. However, in the convergent synthetic route, both of the starting materials (14 and 15) and the product (16) were not UV active, making it challenging to monitor the reaction progress and product purity. The reaction was thus considered to be less controllable and was therefore aborted.

Scheme 4. Methods toward the Synthesis of Compound 18.

Reagents and conditions: (a) HATU, DIPEA, DCM/DMF, r.t. overnight; (b) HCl/dioxane, r.t., DCM, overnight; and (c) LiOH, THF/H2O, r.t., overnight.

In the final step, we were able to obtain 18 with ∼90% purity after de-protection. However, a fine solid was not formed in any solvent (DCM, EA, dioxane, ACN, etc.) we tried. Fortunately, the HCl salt 18 was readily soluble in water, and the impurities were removed by washing with DCM. The water solution was basified with NaHCO3, saturated with NaCl, and then extracted with DCM/MeOH (10/1, v/v). The free base of 18 was a foamy solid that stuck to the recovery flask after the evaporation of solvents. To increase its storage stability and handling convenience, the free base was saltified with HCl again. The resulting salt was dissolved in MeOH and added dropwise to ethyl acetate. The product precipitated out during addition. The solid was filtered and dried under vacuum to give VH032 amine hydrochloride (18) as a fine beige solid with 65% net overall yield and 97% purity. The obtained solid contains ∼5% of residual ethyl acetate and ∼10% inorganic salts, for example, NaCl, which were carried over from the work-ups. However, the residual solvents or inorganic salts in the product will not affect the product quality for subsequent synthesis uses. The 1H NMR spectrum of 18 synthesized in this work was almost identical to the one from a commercial source (Caymanchem, item NO. 21591) except the thiazole proton of the commercial product had a larger chemical shift (9.96 ppm vs 9.64 ppm) (Figures S11–S13). We speculated that this was because excessive amounts of HCl existed in the commercial product which protonated the thiazole nitrogen. In addition, trace amounts of residual dichloromethane, dioxane, and methanol were also observed in the commercial product (Figure S13).

We next tested whether the biological activity of a PROTAC derived from the synthesized compound 18 was comparable to that from the commercial source. We synthesized two batches of the published BRD4 PROTAC MZ1(17) using the compound 18 synthesized in this work or from the commercial supplier in a similar yield. The BRD4 PROTACs generated were named as MZ1-S (synthesized) and MZ1-C (commercial), respectively. We tested their BRD4 degradation and cell survival inhibition activities in 22RV1 human prostate cancer cells. As demonstrated in Figure 1, MZ1-S and MZ1-C exhibited nearly identical capabilities for degrading BRD4 protein and inhibiting 22RV1 cell survival in a dose-dependent manner. These data proved that the VH032 amine prepared using our process performed equivalently to commercially available VH032 amine in generating VHL-based PROTACs.

Figure 1.

Biological activity comparison of (A) MZ1-S and (B) MZ1-C. Top panels: BRD4 degradation test. 22RV1 cells were treated with the compounds at the indicated concentrations. Cells were lysed, and the lysate was analyzed by Western blotting. Bottom panels: cell viability test. 22RV1 cells were treated with the compounds at the indicated concentrations; viable cells were counted by the MTT method. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Conclusions

In summary, a feasible column chromatography-free, multi-gram scale synthetic process of VH032 amine was developed. Following the optimized synthetic procedures with cheap starting materials, one chemist will be able to synthesize 42.5 g of VH032 amine hydrochloride in 65% overall yield with 97% purity in a week. The quality of the synthesized VH032 amine was comparable to that of the one received from a commercial source. Although we did not validate the process on a manufacturing scale, all conditions in theory can be applied to a kilo-gram scale pilot plant synthesis.

Experimental Section

Chemical Synthesis

All starting materials and reagents were either obtained from commercial suppliers or prepared according to literature-reported procedures. All purchased chemicals and solvents were used without further purification unless otherwise noted. All reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography or liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (Thermo Surveyor HPLC system with Thermo Finnigan LCQ Deca). 1H NMR spectral data were recorded on a Varian 400 NMR spectrometer, and 13C NMR was recorded on a Varian Mercury 101 NMR spectrometer at ambient temperature. Chemical shifts (δ) were reported in parts per million, coupling constants (J) values were in hertz, and the splitting patterns were abbreviated as follows: s for singlet; d for doublet; t for triplet; q for quartet; and m for multiplet. HPLC spectra were collected using an Agilent 1100 HPLC instrument (column: Phenomenex kinetex 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; solvent A: H2O/0.1% TFA; solvent B: MeOH/0.1% TFA; run time: 12 min; time/%B: 0.0/30, 6.0/100, 7.0/100, 7.01/30, 12.0/30; flow rate: 0.8 mL/min; wavelength: 254 nm).

Step 1. Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-Bromobenzylcarbamate (11)

(4-Bromophenyl)methanamine (50 g, 269 mmol) was dissolved in EA (250 mL). NaHCO3 (15.8 g, 188 mmol) and water (250 mL) were added subsequently. To this mixture, a solution of Boc2O (70 g, 322 mmol) in EA (100 mL) was added dropwise at room temperature. A white solid precipitated out during addition. The resulting slurry was stirred at room temperature overnight and turned clear. The reaction mixture was separated, and the water phase was extracted with EA (200 mL). The EA phase was combined and washed with water (100 mL) twice and brine (100 mL) twice. The EA phase was concentrated under vacuum to give colorless oil of 89.6 g (weight percent 83%, yield 97%), which solidified upon standing. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.50 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.08 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 1.38 (s, 9H).

Step 2. Synthesis of tert-Butyl 4-(4-Methylthiazol-5-yl)benzylcarbamate (10)

A mixture of crude 11 (62 g, 180 mmol), 6 (54 g, 420 mmol), and KOAc (41.2 g, 420 mmol) in DMAc (420 mL) was degassed with nitrogen for 20 min. Pd(OAc)2 (1.0 g, 10.5 mmol) was added. The mixture was degassed with nitrogen for another 10 min and then heated to 130 °C. The mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 4 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated. EA (800 mL) and water (300 mL) were added to the residue and filtered through a pad of diatomite. The diatomite pad was rinsed with EA (200 mL). The filtrate was separated, and the EA phase was washed with water (200 mL) twice and brine (200 mL) twice. The EA phase was concentrated. DCM (200 mL) was added to the residue and concentrated (repeat once). The resulting residue was used directly for the next step.

Step 3. Synthesis of (4-(4-Methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)methanamine Hydrochloride (4)

DCM was added to the above residue to reach a final volume of 400 mL. To the solution, HCl (160 mL, 4 M in dioxane) was added dropwise at room temperature for over 30 min. A solid precipitated out during addition. The slurry was stirred at room temperature overnight. The mixture was filtered and dried under vacuum to get a 44.8 g dark yellow solid (weight percent 93%, two-step yield 96%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.57 (s, 3H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 4.06 (q, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (s, 3H).

Step 4. Synthesis of (2S,4R)-tert-Butyl 4-Hydroxy-2-((4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidine-1-carboxylate (Boc-13)

Compound 4 (66.7 g, 258 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (300 mL) and DCM (300 mL). The solution was cooled to 0 °C, and TEA (100 mL, 720 mmol) was added. Then, 12 (61.2 g, 264 mmol) and HATU (118.56 g, 312 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 1 h and then stirred at room temperature overnight. Most of the solvent was removed under vacuum. To the residue was added saturated NaHCO3 solution (1 L) and then extracted with EA (800 mL) once and (400 mL) twice. The organic phase was combined and washed with NaHCO3 solution (450 mL) once and brine (450 mL) twice. The organic phase was dried over sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under vacuum to give a 128.8 g crude product.

Step 5. Synthesis of (2S,4R)-4-Hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide Hydrochloride (13)

Crude Boc-13 (125 g, 300 mmol) was dissolved in dioxane (400 mL) and EA (100 mL). Then, HCl (550 mL, 4 M in dioxane) was added dropwise at room temperature over 1 h. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The yellow solid was filtered, washed with EA, and dried under vacuum to give a 104.5 g crude product (weight percent 82%, yield 94%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.70 (s, 1H), 9.01–8.95 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 4.61 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.55–4.47 (m, 3H), 3.66 (s, 1H), 3.49–3.39 (m, 1H), 2.58 (s, 3H), 2.52–2.45 (m, 1H), 2.13–2.05 (m, 1H).

Step 6. Synthesis of tert-Butyl ((S)-1-((2S,4R)-4-Hydroxy-2-((4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)carbamate (17)

Compound 14 (46.3 g, 200 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (530 ml). The solution was cooled to 0 °C, and DIPEA (87 mL, 501 mmol) was added, followed by HATU (88.9 g, 234 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, then cooled to 0 °C, and compound 13 (53 g, 123 mmol) was added slowly. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight. DCM (530 mL) was added to the reaction mixture. Then, the reaction mixture was transferred to a separation funnel and washed with 10% citric acid (300 mL) twice, saturated NaHCO3 (300 mL) twice, water (300 mL) twice, and brine (300 mL) once. The organic phase was concentrated under vacuum to about 600 mL and used for the next step directly.

Step 7. (2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-Amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide Hydrochloride (18, VH032 Amine HCl)

To a solution of compound 17 in DCM (from the last step), HCl (117 mL, 4 M in dioxane) was added dropwise at room temperature for over 30 min. MeOH (50 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated, and water (600 mL) was added. The solution was transferred to a separation funnel and washed with DCM (200 mL) three times. The aqueous phase was then transferred to a beaker, and solid NaHCO3 (53 g) was added to the solution to adjust the pH to 8. A solution of DCM/MeOH (500 mL, 10/1, v/v) was added, followed by solid NaCl (300 g). The mixture was stirred for 30 min and filtered. The filtrate was transferred to a separation funnel and separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with DCM/MeOH (200 mL, 10/1, v/v) twice. The organic phase was combined and concentrated under vacuum. The resulting beige foam was dissolved in dioxane (600 mL), and HCl (42.8 mL, 4 M in dioxane) was added dropwise for over 30 min. The resulting mixture was concentrated under vacuum and dissolved in MeOH (220 mL). The solution was added dropwise to EA (2.4 L) over 2 h. The precipitated solid was filtered and dried under vacuum to give a 50 g beige solid (weight percent 85%, net weight 42.5 g, two-step yield 74%; and overall yield 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 9.64 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.71–4.65 (m, 1H), 4.59–4.52 (m, 2H), 4.43–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.07 (s, 1H), 3.87–3.82 (m, 1H), 3.74–3.69 (m, 1H), 2.57 (s, 3H), 2.34–2.27 (m, 1H), 2.13–2.05 (m, 1H), 1.14 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD): δ 174.10, 168.55, 155.45, 144.48, 141.79, 130.44 (2C), 129.25 (2C), 129.10, 71.16, 60.98, 60.34, 58.07, 49.00, 43.63, 39.11, 35.79, 26.65 (3C), 13.90. HPLC purity 97.1%.

Quantitative NMR

Compounds 4, 11, 13, 18, and N,N-dimethylacetamide

(internal standard) were dissolved in

DMSO-d6 to make 20 mM solutions. Solutions

of 4, 11, 13, and 18 were mixed with N,N-dimethylacetamide

solution at the ratio of 1/1 (v/v). 1H NMR spectra were

obtained for each mixture with a relaxation delay of 30 s at ambient

temperature (Figures S14–S17). The

weight percent of each compound was calculated with the following

equation:  , where Si was the integrated

signal area, and Ni was the number of protons in

the functional group.

, where Si was the integrated

signal area, and Ni was the number of protons in

the functional group.

Biological Activity Test

The stock solution of 10 mM MZ1-S and MZ1-C was prepared in DMSO. 22RV1 (CRL-2505) cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/mL penicillin/streptomycin, and l-glutamine. Cells were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and the cell line was routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert kit from Lonza.

Western Blotting

22RV1 cells were incubated with 0.01, 0.1, 1 μM MZ1-S or MZ1-C, or an equivalent volume of vehicle DMSO for 16 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with BRD4-specific (39909, Active motif) and β-actin-specific (A5441, Sigma) antibodies.

Cell Viability

5 × 103 22RV1 cells were seeded in a volume of 100 μL in complete growth medium on 96-well plates. Test cells were incubated with 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μM MZ1-S or MZ1-C in a total volume of 100 μL per well for three days. After incubation, cells were stained with thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (Sigma). Relative viability was calculated using baseline values of untreated cells as a reference. The optical density at 570 nm (OD570) was determined using an ELISA microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Acknowledgments

H.L. was supported by a grant from the Arkansas Research Alliance. H. Lin was supported by NIH R01 grants (R01CA248037 and R01CA256158).

Glossary

Abbreviations used

- ACN

acetonitrile

- Boc2O

di-tert-butyl decarbonate

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- EA

ethyl acetate

- KOAc

potassium acetate

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate

- HCl

hydrochloride

- MeOH

methanol

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- NaHCO3

sodium bicarbonate

- Pd(OAc)2

palladium(II) acetate

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00245.

HPLC, LCMS, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and qNMR spectra of selected intermediates and final compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ W.Y. and B.-S.P. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sakamoto K. M.; Kim K. B.; Kumagai A.; Mercurio F.; Crews C. M.; Deshaies R. J. Protacs: chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 8554–8559. 10.1073/pnas.141230798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Gao H.; Yang Y.; He M.; Wu Y.; Song Y.; Tong Y.; Rao Y. PROTACs: great opportunities for academia and industry. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2019, 4, 64. 10.1038/s41392-019-0101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullard A. Targeted protein degraders crowd into the clinic. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 247–250. 10.1038/d41573-021-00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Song Y. Proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) for targeted protein degradation and cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 50. 10.1186/s13045-020-00885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford B. Arvinas unveils PROTAC structures. Chem. Eng. News 2021, 9, 5. 10.47287/cen-09914-scicon1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper E.; Smith N.; Cox M.; Scripture C.; Figg W. Thalidomide metabolism and hydrolysis: mechanisms and implications. Curr. Drug Metab. 2006, 7, 677–685. 10.2174/138920006778017777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessum N. E. A.; Sharp S. Y.; Caldwell J. J.; Pasqua A. E.; Wilding B.; Colombano G.; Collins I.; Ozer B.; Richards M.; Rowlands M.; Stubbs M.; Burke R.; McAndrew P. C.; Clarke P. A.; Workman P.; Cheeseman M. D.; Jones K. Demonstrating in-cell target engagement using a pirin protein degradation probe (CCT367766). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 918–933. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S.; Zhang X.; Lv D.; Zhang Q.; He Y.; Zhang P.; Liu X.; Thummuri D.; Yuan Y.; Wiegand J. S.; Pei J.; Zhang W.; Sharma A.; McCurdy C. R.; Kuruvilla V. M.; Baran N.; Ferrando A. A.; Kim Y.-m.; Rogojina A.; Houghton P. J.; Huang G.; Hromas R.; Konopleva M.; Zheng G.; Zhou D. A selective BCL-XL PROTAC degrader achieves safe and potent antitumor activity. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1938–1947. 10.1038/s41591-019-0668-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimate based on 2022 price listed by Cayman Chemical (100 mg/US $314. www.caymanchem.com. (accessed Feb 22, 2022).

- Hughes S. J.; Ciulli A. Molecular recognition of ternary complexes: a new dimension in the structure-guided design of chemical degraders. Essays Biochem. 2017, 61, 505–516. 10.1042/ebc20170041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crew A. P.; Hornberger K. R.; Wang J.; Crews C. M.; Jaime-Figueroa S.; Dong H.; Qian Y.; Zimmerman K.. Polycyclic compounds and methods for the targeted degradation of rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma polypeptides. 2020, 2020051564.

- Campos S. A.; Harling J. H.; Miah A. H.; Smith I. E. D.. Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) directed to the modulation of the estrogen receptor. 2014, 2014108452.

- Buckley D. L.; Gustafson J. L.; Van Molle I.; Roth A. G.; Tae H. S.; Gareiss P. C.; Jorgensen W. L.; Ciulli A.; Crews C. M. Small-molecule inhibitors of the interaction between the E3 ligase VHL and HIF1α. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 11463–11467. 10.1002/anie.201206231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan J.; Nello M.; Matthew W.. Mertk degraders and uses thereof. 2020, 2020010210.

- Han X.; Wang C.; Qin C.; Xiang W.; Fernandez-Salas E.; Yang C.-Y.; Wang M.; Zhao L.; Xu T.; Chinnaswamy K.; Delproposto J.; Stuckey J.; Wang S. Discovery of ARD-69 as a highly potent proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) degrader of androgen receptor (AR) for the treatment of prostate cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 941–964. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinebach C.; Voell S. A.; Vu L. P.; Bricelj A.; Sosič I.; Schnakenburg G.; Gütschow M. A Facile Synthesis of Ligands for the von Hippel–Lindau E3 Ligase. Synthesis 2020, 52, 2521–2527. 10.1055/s-0040-1707400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zengerle M.; Chan K.-H.; Ciulli A. Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1770–1777. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.