Abstract

The patterns of genetic variation of samples of Candida albicans isolated from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Durham, N.C., and Vitória, Brazil, were compared. Genotypes for 126 strains were obtained at 16 polymorphic restriction sites distributed on nine PCR fragments. The results indicated evidence of clonality both within and between these two geographically diverse samples. The samples are genetically very similar, with little evidence of genetic differentiation.

Previous studies on the population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans (Robin) Berkhout (1923) revealed its diploid nature and predominantly clonal mode of reproduction (3, 7, 8, 19). However, little is known about the geographic structure of this species. Clemons et al. showed that strains from the United States and Europe were on average more similar to each other than they were to strains from Singapore (2). Since their genotyping methods did not allow the unambiguous assignment of alleles to individual loci, the population gene frequencies and genetic distances cannot be calculated to determine whether geographically diverse samples of C. albicans are statistically differentiated. Codominant markers are best able to address these issues.

As an initial attempt to understand the geographic structure of C. albicans, we applied codominant markers to examine the patterns of genetic variation between different geographic samples of C. albicans. Sixty-two and sixty-four isolates of C. albicans were obtained by oral swabs of patients at Infectious Diseases Clinics at Duke University Medical Center (Durham, N.C.) and Vitória Hospital (Vitória, Brazil). There was one isolate per patient, and all patients had AIDS at the time of sampling. Genomic DNA was isolated as previously described (10).

The molecular markers were described in a previous study; an additional polymorphic restriction site (around 350 bp) in primer pair E15n7 was present in the Vitória sample but absent in the Durham samples (19). Altogether, 16 polymorphic restriction sites were analyzed for the two samples. The protocols for PCR amplification, digestion with restriction endonucleases, agarose gel electrophoresis, and scoring were performed as previously described (19).

A total of 45 multilocus genotypes were found among the 126 strains. Six genotypes were shared between the two samples, representing a total of 80 isolates, 43 from Durham and 37 from Vitória. The most common genotype was found in both samples, 35 isolates from Durham and 15 from Vitória.

To compare genetic variation between samples, the following genetic parameters were analyzed: (i) observed heterozygosity (4), (ii) gene diversity (4), and (iii) Stoddart’s genotypic diversity (12, 13). The statistical significance between the samples for the three measures was assessed by the t test (1, 11). The results indicated that the samples have similar observed heterozygosities, gene diversities, and genotypic diversities (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons of heterozygosity, gene diversity, and genotypic diversity between two geographically diverse samples of C. albicans isolated from patients with AIDS

| Geographic origin | Sample type | Mean ± SDa

|

Stoddart’s genotypic diversityb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed heterozygosity | Gene diversity | |||

| Durham, N.C. | All isolates | 0.1027 ± 0.2071 | 0.1318 ± 0.1534 | 3.013c |

| Clone corrected | 0.1619 ± 0.1756 | 0.2056 ± 0.1939 | NAd | |

| Vitória, Brazil | All isolates | 0.1213 ± 0.2173 | 0.1552 ± 0.1642 | 8.896c |

| Clone corrected | 0.1541 ± 0.1674 | 0.1779 ± 0.1549 | NA | |

Based on Student’s t test, none of the differences in heterozygosities and gene diversities were statistically significant between the two geographically diverse samples at a P value of < 0.05.

The difference in genotypic diversity between the two samples is not statistically significant by the t test as suggested by Chen et al. (1).

Significantly lower (P < 0.001) than expected from the hypothesis of random recombination conditional on gene frequencies (13).

NA, not applicable.

To examine whether the samples showed similar evidence of clonality and recombination, we used three common tests: (i) the Hardy-Weinberg (HW) equilibrium test, which examines the associations of alleles within each locus (4, 11, 15); (ii) the composite genotypic equilibrium test, which examines the associations of alleles between pairs of loci (6, 15, 20); and (iii) a t test between observed and expected genotypic diversities (13).

The results of the first two tests are presented in Table 2. In both samples, about half of the loci showed genotypic frequencies not significantly different from those expected from random recombination, and in both samples, all but one of the loci in HW disequilibrium showed an excess of homozygotes. A similar pattern of allelic association between loci was found for the two samples, with more than half the pairs of loci in composite genotypic disequilibrium (Table 2). The third test (13) also showed evidence for significant departure from panmixia in both samples (P < 0.001 for both samples). Therefore, consistent with previous studies based on codominant molecular markers (3, 8, 19), these geographically diverse samples showed a significant clonal component, with some evidence for recombination (Table 2). The possible mechanisms and implications of this pattern of genetic variation within a population have been discussed elsewhere (3, 8, 19).

TABLE 2.

Patterns of allelic association in the two geographically diverse samples of C. albicans isolated from patients infected with HIV

| Geographic origin | Sample type | No. of polymorphic loci

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Within a locus

|

Between locid

|

||||||

| Xa | Yb | Zc | Ue | Lf | Tg | |||

| Durham, N.C. | All isolates | 14 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 16/76 | 2/15 | 18/91 |

| Clone corrected | 14 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 37/76 | 6/15 | 43/91 | |

| Vitória, Brazil | All isolates | 15 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 17/92 | 3/13 | 20/105 |

| Clone corrected | 15 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 36/92 | 4/13 | 40/105 | |

Loci in HW equilibrium.

Loci with excess of homozygotes.

Loci with excess of heterozygotes.

Number of pairs of loci in equilibrium/total number of polymorphic pairs.

Loci on different PCR fragments.

Loci on the same PCR fragment.

All pairs of loci, regardless whether they were from the same or different PCR fragments.

Genetic differentiation between the two samples was quantified with traditional F statistics (4–6, 15–17). The F statistics were calculated by an analysis of variance approach, implemented in the program GDA1d32, and the 95% confidence limits were estimated by jackknifing (6, 16). Probability testing for genetic differences between samples was performed by chi-square contingency table tests of gene frequencies at each individual locus and summed across all loci (5, 11, 18, 19).

The overall FST value between the two samples was 0.017, with 95% confidence limits of 0.001 to 0.035. Hence, the large geographic separation of the two sampling locations contributed only about 1.7% to the overall levels of genetic variation of the total sample. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in allele frequencies for 13 of the 16 loci (data not shown). The summed chi-square values for the 16 loci was 25.561 (df = 16, P > 0.05). Both tests provide strong evidence for genetic homogeneity between these two samples.

Because C. albicans and many other microbes are known to reproduce clonally via mitosis, the use of clone correction has been proposed as a means of reducing overrepresentation of individual genotypes derived from locale-specific clonality (1, 19). In the clone-corrected sample analyses, only one isolate of each multilocus genotype was taken from each sample. The patterns of genetic variation within and between clone-corrected samples were similar to the results that included all the isolates (Tables 1 and 2). The overall FST value between the two clone-corrected samples was 0.002, lower than between the total samples. None of the 16 loci showed any significant difference in gene frequency between the two geographically diverse samples in the clone-corrected data analysis (data not shown), with a summed chi-square value of 23.257 (df = 16, P > 0.05).

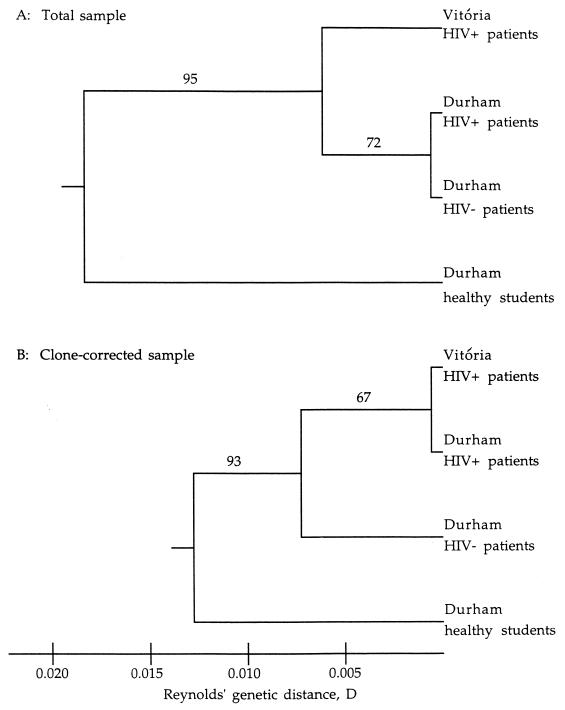

We tested whether the high genetic similarity between the two samples is related to the AIDS patients. Two additional samples from Durham (one sample from human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-negative patients and the other from healthy student volunteers [19]) were included in the genetic distance analysis (9). The genetic similarities among samples are presented in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1A, the two patient samples from Durham are seen to be most similar to each other. Surprisingly, these two samples were more similar to the sample from AIDS patients in Vitória than to the sample from healthy students in Durham. The analysis of clone-corrected samples (Fig. 1B) produced strong support for potential association of AIDS with genetic similarity of C. albicans isolates. In this analysis, the two samples from HIV-infected patients were more similar to each other than either was to any of the other samples (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

UPGMA phenograms describing genetic similarity among four samples of C. albicans. The distance measure is based on Reynolds’ genetic distance (9). The phenograms are based on two sample types, total samples and clone-corrected samples. Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates are given.

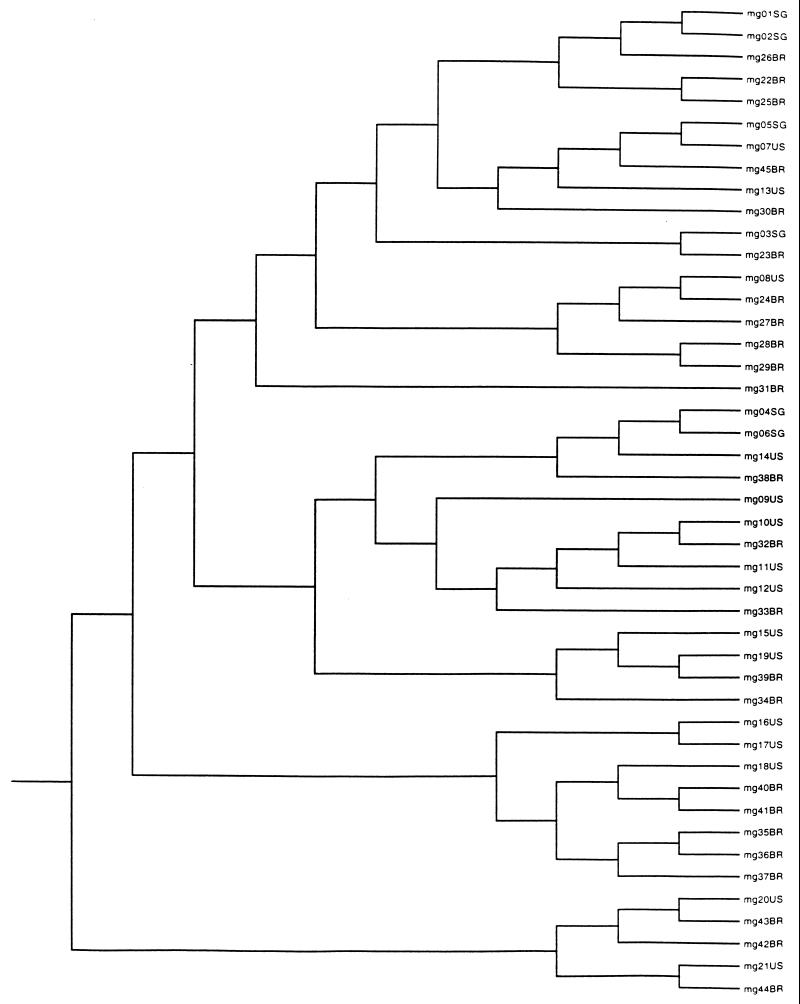

The similarity analysis among individual multilocus genotypes, assessed with the unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic means (UPGMA) algorithm of PAUP4d64 (14), generated a phenogram for all 45 multilocus genotypes (Fig. 2). This phenogram indicated no evidence that a single cluster contained all the strains from one geographic origin. The genotypes shared by isolates from the two geographic areas were also dispersed in the phenogram.

FIG. 2.

UPGMA phenogram of the 45 multilocus genotypes. The genotypes shared by isolates from the two geographic areas are all marked by SG following a code designation. All other multilocus genotypes are presented by a code number followed by abbreviations of geographic origins (US, from Durham, N.C.; BR, from Vitória, Brazil).

In summary, this is the first study to apply population genetic approaches to compare geographically separated samples of C. albicans from AIDS patients. The results showed evidence for clonality both within and between geographically diverse samples. Even though the two samples, one from North America and the other from South America, are genetically indistinguishable, many questions remain. For example, is this pattern of genetic structure typical for other host groups in the two regions? Will other geographic regions show similar patterns of clonality and genetic homogeneity? The approaches presented here should contribute to the understanding of these and other questions relating to the epidemiology and pathogenesis of candidiasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wiley Schell, Kieren Marr, Preston Klassen, Barbara Alexander, and Cynthia Boyd for helping to collect strains. We appreciate the extensive comments of one anonymous reviewer. We gratefully acknowledge the collaboration of Reynaldo Dietze of the Federal University of Espirito Santo, Brazil, whose contributions made this research possible.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI 28836 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen R S, Boeger J M, McDonald B A. Genetic stability in a population of a plant pathogenic fungus over time. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemons K V, Feroze F, Holmberg K, Stevens D. Comparative analysis of genetic variability among Candida albicans isolates from different geographic locales by three genotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1332–1336. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1332-1336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gräser Y, Volovsek M, Arrington J, Schönian G, Presber W, Mitchell T G, Vilgalys R. Molecular markers reveal that population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans exhibits both clonality and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12473–12477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartl D L, Clark A G. Principles of population genetics. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson R R, Boos D D, Kaplan N L. A statistical test for detecting geographic subdivision. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:138–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis P O, Zaykin D. Genetic data analysis: software for the analysis of discrete genetic data. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1998. . (Test version used with permission of the authors.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odds F C. Candida and candidosis: a review and bibliography. 2nd ed. Toronto, Canada: Bailliere Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pujol C, Reynes J, Renaud F, Raymond M, Tibayrenc M, Ayala F J, Janbon F, Mallie M, Bastide J-M. The yeast Candida albicans has a clonal mode of reproduction in a population of infected human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9456–9459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds J, Weir B S, Cockerham C C. Estimating the coancestry coefficient: basis for a short-term genetic distance. Genetics. 1983;105:767–779. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.3.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scherer S, Stevens D A. A Candida albicans dispersed, repeated gene family and its epidemiological applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1452–1456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokal R R, Rohlf F J. Biometry. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoddard J A. A genotypic diversity measure. J Hered. 1983;74:489–490. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoddart J A, Taylor J F. Genotypic diversity: estimation and prediction in samples. Genetics. 1988;118:705–711. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.4.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swofford D L. PAUP4d64: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution of Natural History; 1998. . (Test version.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weir B S. Genetic data analysis. 2nd ed. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weir B S, Cockerham C C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution. 1984;38:1358–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright S. Evolution and genetics of populations. 2. The theory of gene frequencies. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Kerrigan R W, Callac P, Horgen P A, Anderson J B. The genetic structure of natural populations of Agaricus bisporus, the commercial mushroom. J Hered. 1997;88:482–488. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu J, Mitchell T G, Vilgalys R. PCR-RFLP analyses reveal both extensive clonality and local genetic differentiation in Candida albicans. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:59–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaykin D, Zhivotovsky L, Weir B S. Exact tests for association between alleles at arbitrary numbers of loci. Genetica. 1995;96:169–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01441162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]