Abstract

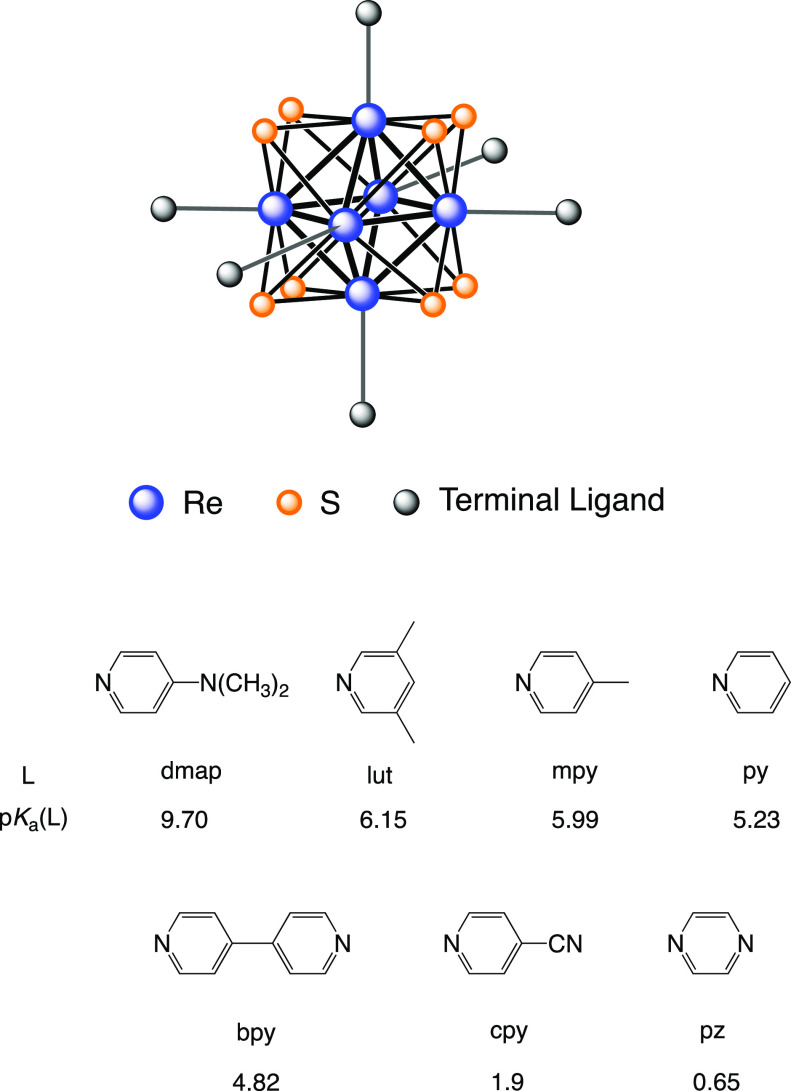

The present study reports that the ground- and excited-state Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potentials of an octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complex can be controlled by systematically changing the number and type of the N-heteroaromatic ligand (L) and the number of chloride ions at the six terminal positions. Photoirradiation of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– with an excess amount of L afforded a mono-L-substituted hexanuclear rhenium(III) complex, [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = 4-dimethylaminopyridine (dmap), 3,5-lutidine (lut), 4-methylpyridine (mpy), pyridine (py), 4,4′-bipyridine (bpy), 4-cyanopyridine (cpy), and pyrazine (pz)). The bis- and tris-lut-substituted complexes, trans- and cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2]2– and mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(lut)3]−, were synthesized by the reaction of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]3– with an excess amount of lut in refluxed N,N-dimethylformamide. The mono-L-substituted complexes showed one-electron redox processes assignable to E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] = 0.49–0.58 V versus Ag/AgCl. The ground-state oxidation potentials were linearly correlated with the pKa of the N-heteroaromatic ligand [pKa(L)], the 1H NMR chemical shift of the ortho proton on the coordinating ligand, and the Hammett constant (σ) of the pyridyl-ligand substituent. The series of [Re6(μ3-S)8X6–n(L)n]n−4 complexes (n = 0, X = Cl, Br, I, or NCS; n = 1–3, X = Cl) showed a linear correlation with the sum of the Lever electrochemical parameters at the six terminal ligands (ΣEL). The cyclic voltammograms of the mono-L-substituted complexes (L = bpy, cpy, and pz) showed one-electron redox waves assignable to E1/2(L0/L–) = −1.28 to −1.48 V versus Ag/AgCl. Two types of photoluminescences were observed for the complexes, originating from the cluster core-centered excited triplet state (3CC) for L = dmap, lut, mpy, and py and from the metal-to-ligand charge-transfer excited triplet state (3MLCT) for L = bpy, cpy, and pz. The complexes with the 3CC character exhibited emission features and photophysical properties similar to those of ordinary hexanuclear rhenium complexes. The emission maximum wavelength of the complexes with 3MLCT shifted to the longer wavelength in the order L = 4-phenylpyridine (ppy), bpy, pz, and cpy, which agreed with the difference between E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] and E1/2(L0/L–). The calculated oxidation potential of the excited hexanuclear rhenium complex with the 3CC character was linearly correlated with pKa(L), σ, and ΣEL. The ground- and excited-state oxidation potentials were finely tuned by the combination of halide and L ligands at the terminal positions.

Introduction

Controlling the redox potentials and energy levels of the ground and excited states of a metal complex is important for understanding the fundamental properties of the complex as well as for applications to redox and photo-induced reactions of the complex.1−5 The electron-donating and electron-accepting abilities of a ligand (L) significantly contribute to the control of redox potentials of the metal complexes with L.6−14 Among the several parameter sets available for deriving electron-donating and electron-accepting abilities, the Lever’s electrochemical ligand parameter EL series are particularly useful because they are applicable to predicting the redox potentials and the energy of electronic transitions of the complexes with L.6−12 These parameters are based on the Ru(III)/Ru(II) redox potentials of mononuclear complexes and can be widely applied to elucidate the redox properties of metal complexes.

The chemistry of chalcogenide-capped octahedral hexanuclear rhenium complexes with six terminal ligands has been well studied:15−29 the complex has 24 d electrons (24e), and the oxidation state of each rhenium ion is +3. The complex unit is intriguing because it exhibits rich redox and photoluminescent properties.16−20,28−75 The terminal ligands on the complex are moderately inert to a substitution reaction, which results in stepwise ligand substitutions at the terminal positions.35,51,76,77 The complex unit undergoes one-electron oxidation, and the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) process is dependent on the nature of the terminal ligands.35,37,51,52 The one-electron oxidation process of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– (0.31 V vs Ag/AgCl) shifts positively upon substitution of the terminal chloride ligands with pyridine (py), leading to show at 0.77 V for trans-/cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(py)2]2– or 1.03 V for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(py)3]−.35 A trend similar to that mentioned above has also been observed for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(PEt3)n]n−4 (PEt3: triethylphosphine, n = 1–4).51 The Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potentials for a series of trans-/cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– is linearly correlated with the acid dissociation constant of L, pKa(L), where pKa(L) is an indicator of the electron-donating ability of L.37,52 Szczepura et al. have reported the linear correlation between the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potential for complexes containing {Re6(μ3-Se)8}2+ and the sum of EL at the six terminal ligands.46 Levi and Gatti et al. recently have proposed that the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potential of a {Re6(μ3-Q)8}2+ complex (Q = S, Se, Te) can be well explained by EL.73 However, there is still limited information on the redox properties of mono-L-substituted octahedral hexanuclear rhenium complexes because these complexes remain still scarce.

Sulfide-capped octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes exhibit photoluminescence in the solid state and in solution.28,31−34,37−41,44,45,47−49,51−58,60,61,63,65−67,69−71,75 The photoemissive excited triplet states of these complexes can be classified into two types: cluster core-centered (3CC) and cluster core-to-L charge-transfer [more generally metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (3MLCT)] states. Most octahedral hexanuclear complexes generate the relevant 3CC states upon photoexcitation. The complexes showing the 3MLCT states are still limited to [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(ppy)]3– (ppy: 4-phenylpyridine) and trans-/cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– (L = 4,4′-bipyridine (bpy) or pyrazine (pz)), which possess relevant low-lying π* ligand orbitals.52,53

In the present study, we synthesized and characterized a series of octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes to systematically investigate the ligand dependences of the ground- and excited-state redox properties as well as of the photoluminescence of the complexes. The complexes studied include mono-L-substituted complexes, [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine (dmap), 3,5-lutidine (lut), 4-methylpyridine (mpy), py, bpy, 4-cyanopyridine (cpy), and pz), as shown in Chart 1 in addition to trans-/cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2]2– and mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(lut)3]−. The pKa(L) values reported in the literature are used for L = dmap,78 lut,79 mpy,79 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethane (bpe),80 py,79 ppy,80 bpy,81 cpy,82 and pz79 in the present study. We demonstrate that the ground-state Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potential linearly correlates with pKa(L), the Hammett constant (σ) of the pyridyl-ligand substituent, and the 1H NMR chemical shift of the ortho protons (Ho) in the coordinating pyridyl ligand. The Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potential is also shown to correlate linearly with the sum of the EL values at the six terminal ligands (ΣEL) for the complex. Furthermore, it has been shown that the mono-L-substituted complexes with dmap, lut, mpy, and py exhibit the 3CC emission characters, while the complexes with L = bpy, cpy, and pz show the 3MLCT emission characters. The excited-state properties of the complex are clearly dependent on the energy difference between the highest-occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) level of the octahedral hexanuclear rhenium core and the π* level of the coordinating L. We also found that the excited-state redox potentials of the new complexes and the known sulfide-capped complexes with the 3CC characters showed linear correlations with pKa(L), σ, and ΣEL. This demonstrates clearly that the energy levels of the ground and emissive excited states of an anionic octahedral hexanuclear rhenium complex and its excited-state characteristics are controllable by the nature of L and the combination of L and chloride ligands coordinating at the terminal positions in [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 0–3).

Chart 1. Octahedral Hexanuclear Rhenium Complex and N-Heteroaromatic Ligands.

Results and Discussion

Syntheses and Characterizations of the Complexes

Various neutral and anionic ligands have been introduced at the six terminal positions of sulfide-capped octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes by thermal substitution reactions of the terminal halides or hydroxides in [Re6(μ3-S)8X6]4– (X = Cl, Br, I, OH) in solution or under melt conditions (see refs (16, 35, 37, 39, 44, 45, 47−49, 52−54, 56−58, 61, 63, 65−67, 70, 71, 75, 76, 83−88)). To our knowledge, several reports have been published on photosubstitution reactions of octahedral hexanuclear metal complexes.31,38,89−92 Gray et al. reported that the emission lifetime (τem) and quantum yield (Φem) of a hexanuclear rhenium complex with terminal iodides or solvent molecules in dichloromethane increase in the presence of an added iodide ion or neat solvent molecules [i.e., dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)], suggesting the labile nature of the terminal halides in the excited state.31,38 Zheng et al. reported that UV irradiation of [Re6(μ3-Se)8(PEt3)5{HN=C(OCH3) (CH3)}]2+ in acetonitrile produces [Re6(μ3-Se)8(CH3CN) (PEt3)5]2+ and that of a dichloromethane solution of [Re6(μ3-Se)8(CO)(PEt3)5]2+ affords a 23e complex, [Re6(μ3-Se)8Cl(PEt3)5]2+, in which the coordinating chloride ion originates from dichloromethane.90,91 Szczepura et al. reported oxazoline and oxazine ligand removal reactions on [Re6(μ3-Se8) (PEt3)5(L)]2+ (L = 2-methyloxazoline, 2-phenyloxazoline, and 2-methyloxazine) by UV irradiation.92 In the case of [Mo6(μ3-Cl)8Cl6]2–, spectroscopic and photophysical measurements in acetonitrile revealed that the bond between the chloride atom and the {Mo6(μ3-Cl)8}4+ core was excited by UV irradiation.89 Furthermore, we previously reported that the photosubstitution reaction of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– with an excess of ppy in acetonitrile afforded [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(ppy)]3–.53 In this study, a photosubstitution reaction of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– in acetonitrile was applied to synthesize new octahedral hexanuclear rhenium complexes, [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, bpy, pz, and cpy). The photosubstitution reaction of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– with py was monitored using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Since the substitution reaction of the complex did not proceed in the dark at room temperature, that of the terminal chlorides on the sulfide-capped hexanuclear rhenium(III) complex occurred owing to the labile nature of the terminal chlorides in the complex in the excited state. In contrast to a 24e (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] complex (Bu4N: (n-C4H9)4N), 1H NMR indicates that a 23e (Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] complex does not undergo a substitution reaction with py (10 equiv) in CD3CN at room temperature, even after 40 h photoirradiation. Photosubstitution reactions of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– in acetonitrile are likely to proceed faster with a stronger electron-donating L. After photoirradiation, the solution was evaporated to dryness and the product was purified by silica gel column chromatography to provide a new complex in moderate yield. The chemical shift value of the ortho position (Ho) observed for the coordinate L in the photoproduct in CD3CN is shifted downfield by ca. 1 ppm compared with that observed for the corresponding free ligand. The integrated signal intensity ratio of L to (Bu4N)+ is (Bu4N)+/L = 3:1, confirming that the obtained product is a mono-L-substituted complex anion, [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (abbreviated as [1-L]3–). The structures of [1-dmap]3–, [1-lut]3–, [1-py]3–, and [1-cpy]3– were characterized by single-crystal X-ray analysis. Bis- and tris-lut coordinate complexes were synthesized by the reaction of (Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] with an excess amount of lut in reflux N,N-dimethylformamide and separated by silica gel column chromatography. Tris-substituted [3-1ut]− was eluted first, followed by bis-substituted [2a-lut]2– and [2b-lut]2–, which were eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) mixture. The elution order of the lut-coordinate complexes is similar to that of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(ppy)n]n−4.52 The 1H NMR spectrum of [3-lut]− shows that the integrated intensity ratio of the Ho signal at 9.00 to the signal at 9.06 ppm is 2:1, and the integrated intensity ratio of (Bu4N)+ to lut is 1:3, indicating that [3-lut]− is the tris-lut-substituted complex with the meridional geometry, mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(lut)3]−. The integrated intensity ratios of (Bu4N)+ to lut observed for [2a-lut]2– and [2b-lut]2– are both 2:2. In previously synthesized bis-L-coordinate sulfide-capped octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes, the trans isomer of the complex eluted before the relevant cis isomer in silica gel column chromatography, and the Ho signal of the trans isomer was observed in the upfield side relative to that of the cis isomer in 1H NMR spectroscopy. Based on these observations, we characterized [2a-lut]2– and [2b-lut]2– as the trans and cis isomers, respectively. The structures of [2a-lut]2–, [2b-lut]2–, and [3-lut]− were confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis as described below.

Single-Crystal X-ray Analysis of New Complexes

The molecular structures of [1-dmap]3–, [1-lut]3–, [1-py]3–, [1-cpy]3–, [2a-lut]2–, [2b-lut]2–, and [3-lut]− were determined as shown in Figure 1. The selected bond distances and angles of the complexes are listed in Table 1. The crystallographic data are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information. All the complexes possess {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ units, and the six terminal sites are occupied by chloride ions or L. The six rhenium atoms form an octahedron with the Re–Re–Re angles being approximately 60 and 90°, while the Re–Re distances are in the range of 2.5803(4)–2.6075(7) Å. The faces of the octahedral core are capped with eight sulfur atoms with the Re–S distances of 2.382(3)–2.4273(18) Å. These values resemble the distances and angles of previously reported sulfide-capped octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes with N-heteroaromatic ligands.35,37,52,53,57,85,87,93 In the complexes with a pyridyl ligand, one L and five chlorides occupy at the terminal positions of the {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ unit. The Re–N distances in the mono-L-coordinate complexes are 2.178(5), 2.196 (5), 2.196(8), and 2.230 (6) Å for L = dmap, lut, py, and cpy, respectively. Figure S1 in the Supporting Information shows the relationship between the Re–N bond distance in each complex and the relevant acid dissociation constant of L, pKa(L), including the datum of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(ppy)]3– which was previously reported ([1-ppy]3–).53 The Re–N bond distance tends to decrease with an increase in the electron-donating ability of L and appears to be influenced by molecular packing in the crystal since the Re–N bond distance in the ppy-coordinate complex is longer than those in the other complexes. The Re–Cl bond distances for the mono-pyridyl-coordinate complexes are within a range of 2.4228(19)–2.446(3) Å. In the series of the lut-coordinate complexes, the average Re–Cl bond distance tends to decrease upon substitution of Cl– by lut. This trend is also observed for the series of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(py)n]n−4 (n = 1–3). It is well known that the M–Clterminal bond distance decreases with the increase of the charge on the cluster core in the {Re6(μ3-S)8–n(μ3-Cl)n}n+2 and {Mo6(μ3-Se)n(μ3-Cl)8–n}4–n systems due to Coulomb interactions between the cluster core and terminal chlorides.94−97 The Re–Cl bond distance is proportional to the net charge of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 0–3, L = lut and py) as shown in Supporting Information Figure S2. This suggests that the Coulomb interactions between the cluster core and the terminal chloride are strengthened by the substitution of Cl– with a neutral L.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of [1-dmap]3– (a), [1-lut]3– (b), [1-py]3– (c), [1-cpy]3– (d), [2a-lut]2– (e), [2b-lut]2– (f), and [3-lut]− (g). Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 1. Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) of (Bu4N)3[1-dmap], (Bu4N)3[1-lut], (Bu4N)3[1-py], (Bu4N)3[1-cpy], (Bu4N)2[2a-lut], (Bu4N)2[2b-lut], and (Bu4N)[3-lut].

| (Bu4N)3[1-dmap] | (Bu4N)3[1-lut] | (Bu4N)3[1-py] | (Bu4N)3[1-cpy] | (Bu4N)2[2a-lut] | (Bu4N)2[2b-lut] | (Bu4N)[3-lut] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Distance/Å | |||||||

| Re–Re | 2.5859(4)–2.6062(4) avg. 2.594(1) | 2.5879(3)–2.6023(3) avg. 2.594(1) | 2.5844(6)–2.6075(7) avg. 2.594(2) | 2.5870(4)–2.6057(4) avg. 2.595(1) | 2.5915(4)–2.6043(4) avg. 2.595(1) | 2.5803(4)–2.5999(4) avg. 2.594(1) | 2.5809(4)–2.5999(4) avg. 2.591(1) |

| Re–S | 2.3907(17)–2.4143(19) avg. 2.407(8) | 2.3898(14)–2.4233(14) avg. 2.409(7) | 2.382(3)–2.420(4) avg. 2.405(16) | 2.394(2)–2.414(2) avg. 2.404(10) | 2.390(2)–2.420(2) avg. 2.405(7) | 2.3889(18)–2.4219(18) avg. 2.406(19) | 2.404(2)–2.4273(18) avg. 2.414(9) |

| Re–N | 2.178(5) | 2.196(5) | 2.196(8) | 2.230(6) | 2.207(8) | 2.205(8) | 2.204(6)–2.213(6) avg. 2.209(10) |

| Re–Cl | 2.423(2)–2.4415(18) avg. 2.435(4) | 2.4259(16)–2.4419(15) avg. 2.434(3) | 2.429(4)–2.446(3) avg. 2.435(8) | 2.4228(19) −2.4447(16) avg. 2.433(4) | 2.435(2)–2.437(2) avg. 2.436(3) | 2.4260(19)–2.4408(18) avg. 2.432(4) | 2.4017(18)–2.4079(19) avg. 2.404(3) |

| Bond Angle/deg | |||||||

| Re–Re–Re | 59.679(10)–60.456(10) avg. 60.00(5) | 59.694(8)–60.328(8) avg. 60.00(4) | 59.668(18)–60.554(19) avg. 60.00(9) | 59.666(12)–60.384(11) avg. 60.00(6) | 59.795(12)–60.347(12) avg. 60.00(4) | 59.573(10)–60.373(11) avg. 60.00(5) | 59.694(11)–60.421(11) avg. 60.00(5) |

| Re–Re–Re | 89.726(11)–90.380(11) avg. 90.00(4) | 89.486(9)–90.399(9) avg. 90.00(3) | 89.54(3)–90.449(19) avg. 90.00(8) | 89.573(11)–90.575(12) avg. 90.00(4) | 89.519(13)–90.477(14) avg. 90.00(3) | 89.702(12)–90.319(12) avg. 90.00(4) | 89.475(12)–90.347(12) avg. 90.00(4) |

| Re–S–Re | 65.02(5)–65.53(5) avg. 65.2(2) | 64.73(4)–65.56(3) avg. 65.11(18) | 64.84(8)–65.78(9) avg. 65.3(4) | 65.03(5)–65.92(5) avg. 65.3(3) | 65.05(5)–65.51(5) avg. 65.3(2) | 64.80(4)–65.66(5) avg. 65.2(2) | 64.64(5)–65.34(5) avg. 64.9(2) |

| S–Re–S | 89.12(6)–90.34(6) avg. 89.8(3) | 88.71(5)–90.55(5) avg. 89.8(2) | 88.46(12)–90.59(12) avg. 89.8(6) | 88.85(8)–90.51(7) avg. 89.8(3) | 88.95(8)–90.63(7) avg. 89.8(2) | 88.93(6)–90.65(6) avg. 89.8(3) | 89.09(6)–90.47(6) avg. 89.8(3) |

| S–Re–S | 173.10(6)–174.55(6) avg. 173.5(2) | 173.19(5)–174.59(5) avg. 173.65(17) | 172.80(11)–174.76(11) avg. 173.5(4) | 173.04(7)–174.67(7) avg. 173.4(2) | 172.76(7)–174.40(7) avg. 173.5(2) | 173.03(6)–174.49(6) avg. 173.5(2) | 173.31(6)–174.64(6) avg. 173.9(2) |

| Re–Re–N | 134.16(16)–135.47(16) avg. 134.8(3) | 133.45(14)–136.14(14) avg. 134.8(3) | 134.1(3)–135.5(3) avg. 134.8(5) | 133.72(17)–135.69(17) avg. 134.8(4) | 132.5(2)–137.0(2) avg. 134.8(4) | 132.76(16)–137.13(16) avg. 134.9(5) | 133.18(15)–136.76(16) avg. 134.9(6) |

| Re–Re–Cl | 131.79(5)–138.17(5) avg. 135.0(2) | 133.52(4)–137.60(4) avg. 135.0(2) | 133.44(10)–136.57(10) avg. 135.0(4) | 133.05(7)–137.18(7) avg. 135.0(3) | 134.59(6)–135.89(6) avg. 135.1(1) | 132.99(5)–137.04(5) avg. 135.0(2) | 133.47(5)–136.71(5) avg. 135.1(2) |

Electrochemistry

The cyclic voltammetry (CV) of the new complexes was performed in 0.1 M (Bu4N)PF6–acetonitrile solutions. Figures S3–S5 in the Supporting Information show the cyclic voltammograms of the new complexes together with that of [1-ppy]3–, whose electrochemical properties have not yet been reported. Table 2 summarizes the redox potentials of [Re6(μ3-S)8X6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 0, X = Cl, Br, I, and NCS; n = 1–3, X = Cl) together with the data of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(PEt3)n]n−4 (n = 1–4). The CV of the new mono-L-coordinate complexes shows reversible one-electron oxidation waves in the range of 0.49–0.58 V versus Ag/AgCl, which can be assigned to the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) process. The one-electron oxidation potentials ((E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] versus Ag/AgCl)) for the mono-L-coordinate complexes are between those of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– and [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2–. This indicates that E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] shifts positively upon substitution of the terminal chlorides with L. A trend similar with that mentioned above has been reported for the [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(PEt3)n]n−4 (n = 0–4) series.51 Previously, we reported that the E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– was linearly correlated with the basicity of the coordinating L.37,52 A similar trend observed for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– is confirmed for the E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] of the mono-L-coordinate complexes; the complexes with a more basic L show more negative E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] of the present L-coordinate complexes. Figure 2 shows the pKa(L) dependence of E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– together with that of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2–. Linear correlations between pKa(L) and E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] have been confirmed for both series of the complexes, with the slope values being −0.010 ± 0.001 V for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– and −0.020 ± 0.001 V for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2–. The slope value of the plot observed for the series of the mono-L-coordinate complexes in Figure 2 is half of that for the bis-L-coordinate complexes. Therefore, it is concluded that the electron-donating ability of L influences E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)], and the ligand additivity by the number of L is also confirmed.

Table 2. Ground-State Redox Potential vs Ag/AgCl in 0.1 M (Bu4N)PF6–Acetonitrile and Emission Maximum Wavelength, Emission Lifetime, Emission Quantum Yield, and Calculated Excited-State Oxidation Potential.

| acetonitrile at 298 or 296 K |

solid state at 296 K |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] vs Ag/AgCl | E1/2(L0/L–) vs Ag/AgCl | λmax/nm | τem/μs | Φem | Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] vs Ag/AgCl | ΣEL of the terminal ligands | λmax/nm | τem/μs | |

| Complex with the Core-Centered Excited State | |||||||||

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– | 0.31a | 770b | 6.3b | 0.039b | –1.30 | –1.44 | 770b | 5.6b | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Br6]4– | 0.34c | 780b | 5.4b | 0.018b | –1.25 | –1.32 | 780b | 4.4b | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8I6]4– | 0.36c | 800b | 4.4b | 0.015b | –1.19 | –1.44 | 800b | 3.4b | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(dmap)]3– ([1-dmap]3–) | 0.49 | 754 | 0.18, 6.4 | 0.030 | –1.15 | –1.05 | 721 | 1.7, 4.0 | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(PEt3)]3– | 0.500d,e | 713d | 4.13d | 0.038d | –1.24 | –0.86 | |||

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(lut)]3– ([1-lut]3–) | 0.52 | 756 | 5.8 | 0.046 | –1.12 | –0.99 | 754 | 1.9, 4.1 | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(mpy)]3– ([1-mpy]3–) | 0.53 | 755 | 4.9 | 0.022 | –1.11 | –0.97 | 747 | 1.3, 4.2 | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(py)]3– ([1-py]3–) | 0.54 | 756 | 4.6 | 0.040 | –1.11 | –0.95 | 752 | 0.87, 4.3 | |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(PEt3)2]2– | 0.665d,e | 710d | 4.74d | 0.036d | –1.08 | –0.28 | |||

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(PEt3)2]2– | 0.664d,e | 714d | 5.60d | 0.041d | –1.07 | –0.28 | |||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(dmap)2]2– ([2a-dmap]2–) | 0.68f | 747 | 1.4, 6.4 | 0.051 | –0.98 | –0.66 | 738 | 2.2, 5.1 | |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(dmap)2]2– ([2b-dmap]2–) | 0.68f | 751 | 5.9 | 0.049 | –0.97 | –0.66 | 748 | 0.86, 3.6 | |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2]2– ([2a-lut]2–) | 0.74 | 750 | 4.4 | 0.039 | –0.91 | –0.54 | 743 | 1.7, 4.8 | |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2]2– ([2b-lut]2–) | 0.74 | 747 | 6.4 | 0.056 | –0.92 | –0.54 | 747 | 1.7, 5.4 | |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(mpy)2]2– ([2a-mpy]2–) | 0.75f | 749f | 4.2f | 0.031f | –0.91 | –0.50 | |||

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(mpy)2]2– ([2b-mpy]2–) | 0.75f | 745f | 6.2f | 0.057f | –0.91 | –0.50 | |||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(bpe)2]2– ([2a-bpe]2–) | 0.76g | 751g | 4.4g | 0.024g | –0.89 | –0.44 | 738g | 0.78, 4.0g | |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(bpe)2]2– ([2b-bpe]2–) | 0.76g | 746g | 5.9g | 0.036g | –0.90 | –0.44 | 718g | 0.81, 4.5g | |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(py)2]2– ([2a-py]2–) | 0.77a | 750f | 4.5f | 0.033f | –0.88 | –0.46 | 764 | 0.48, 3.1 | |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(py)2]2– ([2b-py]2–) | 0.77a | 745f | 5.1f | 0.042f | –0.89 | –0.46 | 764 | 0.60, 2.5 | |

| mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(PEt3)3]− | 0.819d,e | 703d | 5.68d | 0.038d | –0.94 | 0.30 | |||

| fac-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(PEt3)3]− | 0.831d,e | 711d | 7.11d | 0.041d | –0.91 | 0.30 | |||

| [Re6(μ3-S)8(NCS)6]4– | 0.84h | 745h | 10.4h | 0.091h | –0.82 | –0.36 | |||

| mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(lut)3]− ([3-lut]−) | 0.94 | 742 | 6.3 | 0.055 | –0.73 | –0.09 | 743 | 1.8, 5.0 | |

| mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(py)3]− ([3-py]−) | 0.97a | 740f | 5.9f | 0.045f | –0.71 | 0.03 | |||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl2(PEt3)4] | 0.980d,i | 717d,j | 7.01d,j | 0.042d,j | –0.75 | 0.88 | |||

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl2(PEt3)4] | 1.00d,i | 722d,j | 6.61d,j | 0.049d,j | –0.72 | 0.88 | |||

| Complex Involving Marginal Core-Centered and MLCT Excited States | |||||||||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(ppy)2]2– ([2a-ppy]2–) | 0.77g | –1.70g | 734g | 4.1g | 0.030g | –0.92 | –0.50 | 727g | 2.0, 4.1g |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(ppy)2]2– ([2b-ppy]2–) | 0.77g | –1.65g | 720g | 4.1g | 0.038g | –0.95 | –0.50 | 685g | 4.9g |

| mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(ppy)3]− ([3-ppy]−) | 1.01g,k | –1.57g,k | 728g | 5.7g | 0.042g | –0.69 | –0.03 | 705g | 1.7, 5.3g |

| mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(bpy)3]− ([3-bpy]−) | 1.06g,k | –1.20g,k | 709g | 1.01g | 0.0057g | –0.69 | 0.09 | 696g | 0.95, 3.1g |

| Complex Involving the MLCT Excited State | |||||||||

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(ppy)]3– ([1-ppy]3–) | 0.53 | –1.74 | 739l | 0.33l | 0.0089l | –1.15 | –0.97 | 690l | 0.96, 3.4l |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(bpy)]3– ([1-bpy]3–) | 0.55 | –1.48 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | –0.93 | 714 | 0.096, 0.52 | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(cpy)]3– ([1-cpy]3–) | 0.57 | –1.28 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | –0.88 | 753 | 0.011, 0.051 | |

| [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(pz)]3– ([1-pz]3–) | 0.58 | –1.44 | n.d. | n.d | n.d. | –0.87 | 750 | 0.088, 0.20 | |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(bpy)2]2– ([2a-bpy]2–) | 0.79f | –1.45 (2e)f | 763f | 0.019f | 0.0013f | –0.84 | –0.42 | 699g | 2.92g |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(bpy)2]2– ([2b-bpy]2–) | 0.79f | –1.44 (2e)f | 768f | 0.013f | 0.0011f | –0.82 | –0.42 | 701g | 0.50, 1.91g |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(cpy)2]2– ([2a-cpy]2–) | 0.83a | –1.19a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | –0.32 | 721 | 0.19, 1.0 | |

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(cpy)2]2–) ([2b-cpy]2–)) | 0.83a | –1.18a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | –0.32 | 750 | 0.050, 0.14 | |

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(pz)2]2–) ([2a-pz]2–)) | 0.86f | –1.34f | 782f | 0.029, 0.013f | 0.0017f | –0.73 | –0.30 | ||

| cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(pz)2]2–) ([2b-pz]2–)) | 0.86f | –1.33f | 785f | 0.021f | 0.0010f | –0.72 | –0.30 | ||

| Complex Whose Excited State Character Is Not Assigned | |||||||||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl2(ppy)4] | 0.44 | 708m | |||||||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Br2(ppy)4] | 0.48 | 715m | |||||||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl2(bpy)4] | –1.07n,o | 0.60 | 725n | ||||||

| trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Br2(bpy)4] | –0.93n,o | 0.64 | 730n | ||||||

Figure 2.

Plot of the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) potential for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz) and [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– (L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, bpe, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz) against pKa(L). The fit lines are drawn by linear least-squares analyses to the data points. The slope values are −0.010 ± 0.001 V (r2 = 0.97) for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– and −0.020 ± 0.001 V (r2 = 0.98) for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2–.

In the present study, we also investigated the relationships between E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] and other physical parameters such as Hammett constant (σ) and the 1H NMR chemical shift of Ho for the coordinating L. The σ values for −N(CH3)2 (−0.83), −CH3 (−0.17), −C6H5 (−0.01), −H (0), -p-C5H4N (0.44), and −CN groups (0.66)98 which are responsible for para-substituent effects are employed for those of dmap, mpy, ppy, py, bpy, and cpy, respectively. In the case of lut, the σ value of −0.14, which is double of the value of meta-substituent effects for a −CH3 group (−0.07),98 was used. As shown in Figures S6 and S7 in the Supporting Information, E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] is linearly correlated with σ and the chemical shift value of Ho for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(pyridyl ligand)n]n−4 (n = 1 and 2), suggesting that E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] of both series can be predicted from these parameters. The respective slope values are 0.051 ± 0.004 V for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(pyridyl ligand)]3– and 0.095 ± 0.008 V for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(pyridyl ligand)2]2– (Figure S6) and 0.087 ± 0.014 Vppm–1 for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(pyridyl ligand)]3–, 0.14 ± 0.01 Vppm–1 for trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(pyridyl ligand)2]2–, and 0.13 ± 0.01 Vppm–1 for cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(pyridyl ligand)2]2– (Figure S7). In Figures S6 and S7, the slope values observed for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(pyridyl ligand)]3– are almost half those of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(pyridyl ligand)2]2–. Therefore, σ and the Ho chemical shift of the coordinating pyridyl ligands show the ligand additivity by the number of L to E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)]. Furthermore, E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] is linearly correlated with the sum of the Lever electrochemical parameter values for the six terminal ligands (ΣEL).6,7 The ΣEL values for the complexes are summarized in Table 2. The plot shows a linear correlation; thus, the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potential can also be predicted from ΣEL, as shown in Figure 3. The SM and IM values are derived from the slope and intercept values in linear least-squares analysis.6,7 These values for {Re6(μ3-S)8}3+/2+ are 0.47 ± 0.01 and 1.19 ± 0.01 V, respectively. The SM value is smaller than that of Re(IV)/Re(III) for mononuclear rhenium complexes (0.86).6,7 It is noted that the SM value for {Re6(μ3-S)8}3+/2+ (0.282 ± 0.003) with triethylphosphine calculated from the reported Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) potential51 are smaller than that of the SM value in this study. This reason for this is unclear at present.

Figure 3.

Linear correlation between the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) potential for [Re6(μ3-S)8X6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 0, X = Cl, Br, I, and NCS; n = 1, X = Cl, L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz; n = 2, X = Cl, L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, bpe, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz; n = 3, X = Cl, L = lut, py, ppy, and bpy) and ΣEL of the terminal ligands. The fit line is drawn by linear least-squares analysis to the data points. The slope and intercept values are 0.47 ± 0.01 and 0.99 ± 0.01 V, respectively (r2 = 0.99).

The mono-L-coordinate complexes with L = ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz show reversible one-electron reduction waves ranging from −1.28 to −1.74 V versus Ag/AgCl, which can be assigned to L-centered reduction processes (L0/L–): see also the Supporting Information, Figure S5. Table 2 summarizes the L0/L– redox potential of the complexes, E1/2(L0/L–). In the case of L = bpy, the complex exhibits an irreversible ligand-centered reduction wave assignable to bpy2–/bpy–. The L-centered reduction waves were not observed up to −2.0 V for the complexes with L = dmap, lut, mpy, and py because the potentials are more negative than −2.0 V and out of the measurable potential range. E1/2(L0/L–) shifts negatively in the order of [1-cpy]3– (−1.28 V) > [1-pz]3– (−1.44 V) > [1-bpy]3– (−1.48 V) > [1-ppy]3– (−1.74 V). This order is consistent with that observed for bis-L-substituted complexes [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– (L = ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz).37,52E1/2(L0/L–) of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– is more negative than those of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– (L = ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz),37,52mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(L)3]− (L = ppy and bpy),52 and trans-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl2(bpy)4].71 In the series of bpy-coordinate complexes, E1/2(L0/L–) shifts positively in the order of [1-bpy]3– (−1.48 V) < [2a-bpy]2– (−1.45 V) < [2b-bpy]2– (−1.44 V) < [3-bpy]− (−1.20 V) < [4-bpy] (−1.07 V). Such a trend was also observed for the ppy-coordinate complexes: [1-ppy]3– (−1.74 V) < [2a-ppy]2– (−1.70 V) < [2b-ppy]2– (−1.65 V) < [3-ppy]– (−1.57 V). The dependence of E1/2(L0/L–) could be due to the energy stabilization of the π* ligand orbitals by stronger solvation with increasing net charge of the complex. The EL parameter is also applicable to the L-centered reduction of ppy- and bpy-coordinate complexes based on the ligand electrochemical parameter theory.6,7 The EL(VWXYZ) values apply to the Re6(μ3-S)8L fragments (L = ppy and bpy) in Re6(μ3-S)8LVWXYZ, where V, W, X, Y, and Z are terminal ligands. For example, V, W, X, Y = Cl and Z = bpy for the reducible {Re6(μ3-S)8}bpy fragment in [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(bpy)2]2–. E1/2(L0/L–), which is the ligand-centered redox potential vs NHE, is given by eq 1

| 1 |

Figure 4 shows the relationship between E1/2(L0/L–) of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (L = ppy; n = 1–3 and L = bpy; n = 1–4) and the ΣEL (VWXYZ) value. For both L = ppy and bpy, the linear correlations afforded the SL and IL values being 0.18 ± 0.04 and −1.33 ± 0.03 V for the Re6(μ3-S)8ppy fragment and 0.35 ± 0.05 and −0.94 ± 0.03 V for the Re6(μ3-S)8bpy fragment, respectively. These SL values are within the range of those reported for polypyridine-coordinate mononuclear metal complexes (0.06 ± 0.02–0.62 ± 0.04).6,7

Figure 4.

Plot of the L0/L– potential for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n–4 [L = ppy; n = 1–3 (black) and L = bpy; n = 1–4 (red)] against ΣEL(VWXYZ) value for the terminal ligands. The fit line is drawn by linear least-squares analysis to the data points. The slope and intercept values are 0.18 ± 0.04 and −1.53 ± 0.03 V (r2 = 0.90) for the Re6(μ3-S)8ppy fragment and 0.35 ± 0.05 and −1.14 ± 0.03 V (r2 = 0.91) for the Re6(μ3-S)8bpy fragment, respectively.

ΔEredox is defined as the difference between the oxidation potential and reduction potentials of the complex: ΔEredox = E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] – E1/2(L0/L–). For the series of mono-L-coordinate complexes, ΔEredox increases in the order of [1-cpy]3– (1.85 V) < [1-pz]3– (2.02 V) < [1-bpy]3– (2.03 V) < [1-ppy]3– (2.27 V). Such a trend in the order of ΔEredox can be discussed in terms of the absorption energy of the band >500 nm and in the emission energy at the peak maximum, as described in later sections.

UV–Vis Absorption Spectra

The UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded in acetonitrile and are shown in the Supporting Information, Figures S8–S10. The absorption bands in λ > 400 nm observed for the new mono-L-coordinate complexes and [1-ppy]3– are shown in the Supporting Information, Figure S11. The band in λ > 500 nm was not observed for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– when L = dmap, lut, mpy, or py (group A), whereas they were observed when L = ppy, bpy, cpy, or pz (group B). In group B, the absorption peak maxima of the complexes with L = cpy, pz, bpy, and ppy are 537, 534, 518, and 511 nm, respectively. Such absorption bands in the visible region were also observed for trans- and cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(bpy)2]2– and assigned to the hexanuclear rhenium core to π* of bpy charge-transfer (MLCT) transition.52 For the complex with metal-centered HOMO and the π* L-centered lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), it is well known that the energy difference between removing a d electron from the metal orbital and adding an electron to the π* orbital of the ligand has a linear correlation with the MLCT absorption band energy.2,6,7Figure S12 in Supporting Information shows the correlation between ΔEredox and the absorption energy, from which the origin of the band in λ > 500 nm for group B can be investigated. The absorption band energy increases in the order of [1-cpy]3– (18 600 cm–1) < [1-pz]3– (18 700 cm–1) < [1-bpy]3– (19 300 cm–1) < [1-ppy]3– (19 600 cm–1) and is linearly correlated with ΔEredox. These results clearly indicate that the absorption band in λ > 500 nm for group B possesses the hexanuclear rhenium core to π* of the ligand MLCT character.

Density Functional Theory Calculations

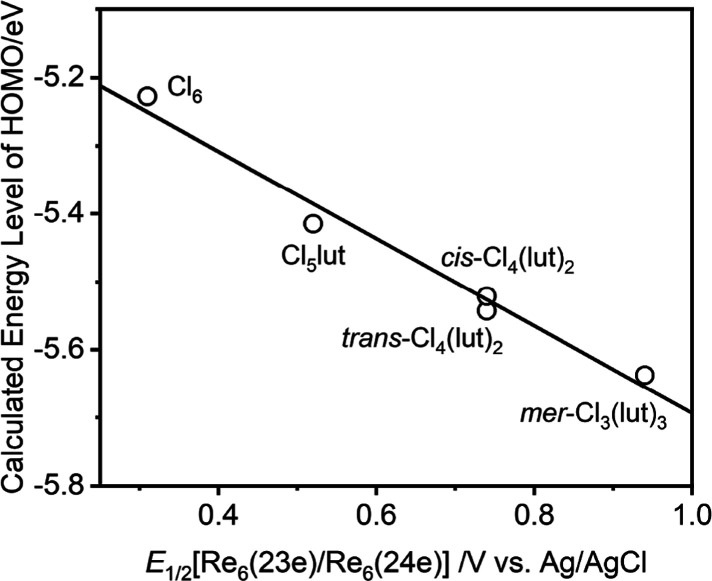

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 0–3, L = lut; n = 1, L = cpy) were performed. The bond distances and angles of the geometrically optimized structures are listed in the Supporting Information, Table S3. The Supporting Information also reports the calculated energy levels and the MO components near the frontier orbital levels (Tables S4–S9) and the energy-level diagrams near the frontier orbitals of the complexes (Figures S13 and S14). The calculated bond distances and angles of the geometrically optimized {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ units evaluated in the present study are similar to those reported previously for octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes.38,40,97,99,100 The calculated Re–Re and Re–Cl bond distances are slightly longer than those determined by single-crystal X-ray analyses (approximately +0.05 Å for Re–Re and +0.05–0.07 Å for Re–Cl). A trend similar to that described above was previously reported for geometrically optimized octahedral hexanuclear rhenium complexes.38,40,97,99,100 The HOMOs are localized on the {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ units. The HOMO energy level is stabilized in the following order: [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– (−5.227 eV), [1-lut]3– (−5.408 eV), [2a-lut]2– (−5.525 eV) and [2b-lut]2– (−5.522 eV), and [3-lut]− (−5.638 eV). As shown in Figure 5, we obtain the linear correlation between E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] and the calculated HOMO energy level, suggesting that the positive shift of E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)], induced by the substitution of chloride with L, stabilizes in energy the HOMO of the complex. The LUMOs of the lut-coordinate complexes range from −1.860 to −2.197 eV, and these MO components are consisted with both π*(lut) and hexanuclear rhenium core orbitals. It is known that the excited electron is localized in the hexanuclear rhenium core orbitals: 3CC excited-state.38,52 The MO composed purely of metals is laid on ca. 0.2 eV upper energy than the LUMO in the present DFT calculations for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(lut)n]n−4 (n = 1–3). The emissive excited triplet states of the lut-coordinate complexes are best characterized by core-centered nature, as described later. Therefore, the MO with the core-centered character will be energetically stabilized larger than the π*(lut) orbital in the excited triplet state. On the other hand, the LUMO of [1-cpy]3– is composed purely of cpy orbitals and has an energy of −2.755 eV, which is approximately 1 eV lower than that of [1-lut]3– (−1.860 eV). The results support the assignment of the cpy-centered reduction wave in the electrochemical measurements. The energy difference between the HOMO and LUMO of [1-cpy]3– is 2.469 eV, which is quite small compared to those of [1-lut]3– (3.548 eV), [2a-lut]2– (3.485 eV), [2b-lut]2– (3.547 eV), and [3-lut]– (3.441 eV). The HOMO–LUMO energy gap of [1-cpy]3– (2.469 eV) is ca. 500 nm, suggesting that the absorption band in λ > 500 nm observed for group B can be attributed to the MLCT transition: CT from hexanuclear rhenium to π* of L. The energy differences between the HOMO and the MO composed purely of metal character are very similar with one another in [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– (3.705 eV), [1-lut]3– (3.686 eV), [2a-lut]2– (3.678 eV), and [3-lut]− (3.678 eV). This indicates that the emission peak energies of the complexes with 3CC character are similar, regardless of the number of L coordinating to the {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ unit as discussed in the following sections.

Figure 5.

Plot of energy level of the HOMO energy level in [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(lut)n]n−4 (n = 0–3) against the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potential.

Excited-State Properties of the New Complexes: Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties

We have previously reported the emission data (maximum wavelength (λem), quantum yield (Φem), and lifetime (τem)) for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(ppy)]3–, trans- and cis-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– (L = py, mpy, bpe, ppy, bpy, and pz), and mer-[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(L)3]− (L = py, ppy, and bpy) in acetonitrile at 296 or 298 K and demonstrated that the origins of the emissive excited states of the complexes can be classified into three groups: the 3CC, 3MLCT, and marginal (3CC/3MLCT) states.52 The complexes with the 3CC excited state are those with L = py, mpy, and bpe ligands, while the complexes possessing the 3MLCT or marginal excited states are those with L = ppy, bpy, and pz. The nature of the excited state is dependent on the type of L and the number of L coordinating to the {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ unit; the complexes showing the 3MLCT excited state are [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 1, L = ppy; n = 2, bpy and pz), and the complexes exhibiting the marginal excited states are [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 2, L = ppy; n = 3, L = bpy).52 In the present work, we studied the emission characteristics of the new complexes together with the known complexes which have not been reported with the emission spectroscopic and photophysical data. Table 2 summarizes the spectroscopic and photophysical data for (Bu4N)4–n[Re6(μ3-S)8X6–n(L)n] (n = 0, X = Cl, Br, I, and NCS; n = 1, X = Cl, L = py, mpy, lut, dmap, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz; n = 2, X = Cl, L = py, mpy, lut, dmap, bpe, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz; n = 3, X = Cl, L = py, lut, bpy, and ppy; n = 4, X = Cl and Br, L = bpy) in solution and in the solid state and (Bu4N)4–n[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(PEt3)n] (n = 1–4) in solution at 296 or 298 K. Figures 6 and 7 show the emission spectra of the Group A complexes ([1-dmap]3–, [1-lut]3–, [1-mpy]3–, [1-py]3–, [2a-lut]2–, [2b-lut]2–, and [3-lut]−) in acetonitrile at 296 K. The complexes in group A exhibit broad and structureless emission spectra, and the emission characteristics [spectral shape, λem (742–756 nm), Φem (0.022–0.056), and τem (4.4–6.4 μs)] are very similar with one another and show very little L dependencies. Such emission characteristics are very similar to those observed for L-coordinate complexes with the 3CC excited states in acetonitrile at 296 or 298 K (Table 2). The λem of the group A complexes shift slightly to the longer wavelength when the phase is changed from the solid state to solution. Such trends were also reported for L-coordinate complexes with the 3CC excited states.52 These results indicate that the emissive states of the complexes belonging to group A are the 3CC excited states, which has been observed for ordinary octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes. The λem values shift slightly to the shorter wavelength in the order of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– (770 nm) > [1-lut]3– (756 nm) > [2a-lut]2– (750 nm) > [2b-lut]2– (747 nm) > [3-lut]− (742 nm) in acetonitrile at 296 K as shown in Figure 7. This trend is also observed for the py-coordinate complexes in acetonitrile at 296 K; [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– (770 nm) > [1-py]3– (756 nm) > [2a-py]2– (750 nm) > [2b-py]2– (745 nm) > [3-py]− (740 nm). The slight blue shift of λem is likely due to the increase of the energy gap with the increase of the number of the substituted terminal L.

Figure 6.

Emission spectra for (Bu4N)3[1-dmap] (black), (Bu4N)3[1-mpy] (red), and (Bu4N)3[1-py] (blue) in acetonitrile at 296 K.

Figure 7.

Emission spectra for (Bu4N)3[1-lut] (black), (Bu4N)2[2a-lut] (red), (Bu4N)2[2b-lut] (blue), and (Bu4N)[3-lut] (olive) in acetonitrile at 296 K.

Figure 8 shows the solid-state emission spectra of the group B complexes ([1-pz]3–, [1-cpy]3–, [1-bpy]3–, and [1-ppy]3–) at 296 K. These complexes except for [1-ppy]3– are not emissive in acetonitrile at 296 K. The emission spectral band shapes of the group B complexes are narrower than those of the group A complexes. λem is largely dependent on the type of L and shifts to the longer wavelength in the order of [1-ppy]3– (690 nm) < [1-bpy]3– (714 nm) < [1-pz]3– (750 nm) < [1-cpy]3– (753 nm). Similar narrower emission spectral band shapes and the large L dependence of λem on the type of L to those observed for the group B complexes were reported for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– (L = bpy and pz), which show 3MLCT emission.37,52 In this study, we observed the linear correlations between the emission energy and absorption energy of the band in λ > 500 nm and between the emission energy and the ΔEredox value: Supporting Information, Figures S20 and S21, respectively. On the basis of these results, we conclude that the emissive excited state of the complexes in group B possesses 3MLCT characters.

Figure 8.

Emission spectra for (Bu4N)3[1-ppy] (black), (Bu4N)3[1-bpy] (red), (Bu4N)3[1-cpy] (blue), and (Bu4N)3[1-pz] (olive) in the solid state at 296 K.

Tuning the Excited-State Oxidation Potential Based on a Combination of Terminal Halide and N-Heteroaromatic Ligands

E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] is finely tuned in the range of 0.3–1.0 V by the combination of halide and L at the six terminal sites on the {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ unit, as described in the section on Electrochemistry. Similarly, the L-centered redox potential can also be tuned by the combination of halide and L. In this section, we investigate the dependence of the excited-state oxidation potential on the nature of the terminal ligands. The oxidation potential, Eox(Mn+1/Mn+*) (Mn+* is the complex in the excited state), in the excited complex can be evaluated based on the ground-state redox potential [E1/2(Mn+1/Mn+)] and the excitation energy E0–0 as in eq 2(2,5)

| 2 |

In the present study, we approximated E0–0 as the emission maximum energy of a complex in eV. The emissive excited states of the hexanuclear rhenium complexes are the 3CC, 3MLCT, and 3CC/3MLCT marginal states, as described in the previous section. Here, we discuss the excited-state oxidation potentials of the complexes with the 3CC and 3MLCT characters. Table 2 shows the calculated Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)* oxidation potential: Eox(Mn+1/Mn+*) = Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*]. Figures S22 and S23 in the Supporting Information show the Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] dependencies of the pKa(L) and σ of the pyridyl ligand, respectively. Good linear correlations are obtained between Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] and both pKa(L) and σ, and the slope values obtained for the series of mono-L-coordinate complexes (−0.011 ± 0.002 V in Figure S22 and 0.056 ± 0.011 V in Figure S23) are almost half those of the corresponding bis-L-coordinate complexes (−0.020 ± 0.002 V in Figure S22 and 0.098 ± 0.007 V in Figure S23). Therefore, the electron-donating ability of L influences Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*]. Figure 9 shows the linear relationship between Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] and ΣEL. Thus, Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] is finely tuned by the combination of halide and L at the six terminal positions on the {Re6(μ3-S)8}2+ unit. The SM and IM values for {Re6(μ3-S)8}3+/2+* obtained from the linear least-squares fitting analysis in Figure 9 are 0.39 ± 0.01 and −0.51 ± 0.01 V, respectively. The SM value of {Re6(μ3-S)8}3+/2+* is similar to that observed for {Re6(μ3-S)8}3+/2+ (SM = 0.47 ± 0.01) owing to the sensitivity of the ground-state redox potential, E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)], while the emission energy shifts slightly depending on the type of terminal ligand for complexes with the 3CC excited-state character. From the slight shift in the excitation energy across the series of complexes, Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] of the complexes with the 3CC character can be predicted on the basis of the properties of the complexes in the ground state, such as the 1H NMR chemical shift, as shown in the Supporting Information, Figure S24. In this case, the slope value of the plot observed for the mono-L-coordinate complex is almost half those of the trans- and cis-oriented bis-L-coordinate complexes.

Figure 9.

Linear correlation between the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)* potential of the excited Re6 complex with the hexanuclear rhenium core-centered excited state for [Re6(μ3-S)8X6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 0, X = Cl, Br, I, and NCS; n = 1, X = Cl, L = dmap, lut, mpy, and py; n = 2, X = Cl, L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, and bpe; n = 3, X = Cl, L = lut and py) and ΣEL value of the terminal ligands. The fit line is drawn by linear least-squares analysis to the data points. The slope and intercept values are 0.39 ± 0.01 and −0.71 ± 0.01 V, respectively (r2 = 0.98).

The Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] values of the complexes with the 3MLCT character were calculated by eq 2, where the excitation energies (E0–0) of the complexes were approximated as the emission energies derived from the relevant λem values. In the present study, analyses of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = ppy, bpy, cpy and pz) were performed using λem in the solid state and E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] in acetonitrile because the complexes are not emissive in acetonitrile at 296 K. Figure S25 in the Supporting Information shows the linear correlation between Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] and ΣEL for the six terminal ligands. The SM and IM values of the plot are 2.1 ± 0.1 and 0.99 ± 0.10 V, respectively. The SM value is larger than that obtained for the complexes with the 3CC excited state. This will be due to the sensitive nature of the emission energy to the coordinating L. The linear correlations were observed between Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] and pKa(L), σ of the pyridyl ligand, or the ground-state 1H NMR chemical shift value of Ho on the pyridyl ligand, as shown in the Supporting Information, Figures S26–S28, respectively. It should be noted that the linear regressions and slope values obtained for the complexes with the 3MLCT excited state are not necessarily reliable because the data are limited for only three or four complexes.

Conclusions

In this study, a series of mono-L-coordinate octahedral hexanuclear rhenium(III) complexes [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = dmap, mpy, py, bpy, cpy, and pz) and a series of lut-coordinate complexes [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(lut)n]n−4 (n = 1–3) were newly synthesized, and their electrochemical, spectroscopic, and photophysical properties were investigated to propose an experimental approach for controlling the ground- and excited-state redox potentials of the octahedral hexanuclear rhenium complexes. The Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potentials of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– ranged between those of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6]4– and [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2–. The Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potentials of [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– and [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2]2– were found to correlate with the electron-donating ability of L, which was quantified by pKa(L), σ of the pyridyl ligand, and the 1H NMR chemical shift value of Ho on the coordinating pyridyl ligand. The Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) redox potentials also correlated well with ΣEL for the six terminal ligands in the series of the complexes, [Re6(μ3-S)8X6–n(L)n]n–4 (n = 0, X = Cl, Br, I, and NCS; n = 1, X = Cl, L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz; n = 2, X = Cl, L = dmap, lut, mpy, py, bpe, ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz; n = 3, X = Cl, L = py, lut, bpy, and ppy). The Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) potential was found to be finely tuned by the combination of halide and L at the terminal positions in the potential range of 0.3–1.0 V versus Ag/AgCl. For the ppy-, bpy-, cpy-, or pz-coordinate complexes, L-centered redox wave(s) were observed. The ligand-centered L0/L– redox potentials of the complexes with the {Re6(μ3-S)8}ppy or {Re6(μ3-S)8}bpy fragment were also found to correlate with ΣEL for the terminal ligands.

The new complexes showed photoemission, and the emission properties were dependent on the type of L coordinating at the terminal position. The photoemissive excited states of the complexes were assigned to the 3CC and 3MLCT excited states. The π* orbital for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(L)]3– (L = ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz) was more energy-stabilized than the metal-centered orbital in which the excited electron was localized in the 3CC excited state, while the π* orbital for [Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6–n(L)n]n−4 (n = 1, L = dmap, lut, mpy, and py; n = 2, L = lut, and n = 3, L = lut) was higher in energy than the metal-centered orbital. On the basis of such results, it was concluded that the emissions from the complexes with L = ppy, bpy, cpy, and pz were assigned to the 3MLCT emissions, while the complexes with L = dmap, lut, mpy, and py exhibited 3CC emissions. In the lut- or py-coordinate complexes with the 3CC characters, λem was found to shift slightly upon substitution of the terminal chloride with L. The oxidation potential of the excited Re6(24e) complex, Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*], was calculated based on E1/2[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)] and the emission energy of the complex. Interestingly, Eox[Re6(23e)/Re6(24e)*] correlated well with the electron-donating ability of L, and this could be predicted from the Re6(23e)/Re6(24e) potential and the emission energy. In this work, the dependence of the L0*/L– potential on the emission properties could not be investigated for the complexes with the 3MLCT excited states because the emissive excited states turned to 3MLCT/3CC characters with an increase in the number of coordinating bpy and ppy. An investigation of the L0*/L– potential dependence of the emission characteristics for the complexes with the 3MLCT excited states is interesting for understanding the chemical properties of octahedral hexanuclear metal complexes in the excited state, which will be worth exploring in future.

Experimental Section

Materials

The hexanuclear rhenium complexes, (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6],30 (Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6],30 (Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(ppy)] (ppy: 4-phenylpyridine),53 and (Bu4N)2[trans-, cis-{Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(L)2}] (L = 4-dimethylaminopyridine (dmap), trans isomer (Bu4N)2[2a-dmap] and cis isomer (Bu4N)2[2b-dmap];37 L = pyridine (py), trans isomer (Bu4N)2[2a-py] and cis isomer (Bu4N)2[2b-py];35 L = 4-cyanopyridine (cpy), trans isomer (Bu4N)2[2a-cpy] and cis isomer (Bu4N)2[2b-cpy]37), were prepared according to the literature methods. Tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate ((Bu4N)PF6) was prepared by metathesis of NH4PF6 with (Bu4N)Br in water and recrystallized twice from ethanol. Spectroscopic grade acetonitrile (Wako) was used for electrochemical and photophysical measurements. All other commercially available reagents were used as received. The photoreaction was performed by using a 100 W high-pressure Hg lamp Riko UVL-100HA as a UV-light source.

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(dmap)] ((Bu4N)3[1-dmap])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and dmap (8.0 mg, 0.065 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 8 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The orange band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetone/diisopropyl ether and allowed to stand for several days. The orange solid obtained was collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-dmap]: 84 mg (59%). Anal. Calcd for C55H118N5Cl5Re6S8·1.5H2O: C, 27.21; H, 5.02; N; 2.89%. Found: C, 26.83; H, 4.64; N, 2.85%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 3.02 (s, 6H, CH3), 3.09 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 6.44 (d, 2H, Hm), 8.77 (d, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 431 (1100), 378 (sh, 2100), 299 (sh, 31 000), 277 (42 000), 238 (50 000), 225 (65 000).

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(lut)] ((Bu4N)3[1-lut])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and 3,5-lutidine (lut) (31 mg, 0.29 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 12 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The orange band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in dichloromethane/diisopropyl ether and allowed to stand for several days. The orange solid obtained was collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-lut]: 104 mg (74%). Anal. Calcd for C55H117N4Cl5Re6S8·2CH2Cl2: C, 26.79; H, 4.77; N; 2.19%. Found: C, 26.57; H, 4.54; N, 2.39%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 2.26 (s, 6H, CH3), 3.09 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 7.54 (s, 1H, Hp), 9.09 (s, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 428 (980), 378 (sh, 2100), 270 (24 000), 239 (sh, 45 000), 226 (58 000).

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(mpy)] ((Bu4N)3[1-mpy])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and 4-methylpyridine (mpy) (27 mg, 0.29 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 12 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The orange band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetone/diisopropyl ether and allowed to stand for several days. The orange solid obtained was collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-mpy]: 87 mg (62%). Anal. Calcd for C54H115N4Cl5Re6S8: C, 27.35; H, 4.89; N; 2.36%. Found: C, 27.32; H, 4.76; N, 2.40%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 2.40 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.10 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 7.14 (d, 2H, Hm), 9.24 (d, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 429 (1100), 380 (sh, 2300), 269 (sh, 28 000), 238 (sh, 53 000), 226 (63 000).

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(py)] ((Bu4N)3[1-py])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and py (23 mg, 0.29 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 12 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The orange band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetone/diisopropyl ether and allowed to stand for several days. The yellow crystals obtained were collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-py]: 99 mg (71%). Anal. Calcd for C53H113N4Cl5Re6S8: C, 27.00; H, 4.83; N; 2.38%. Found: C, 26.97; H, 4.65; N, 2.38%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 3.10 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 7.33 (dd, 2H, Hm), 7.99 (dd, 1H, Hp), 9.43 (d, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 428 (870), 380 (sh, 1900), 270 (21 000), 239 (sh, 42 000), 226 (55 000).

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(bpy)] ((Bu4N)3[1-bpy])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and 4,4′-bipyridine (bpy) (23 mg, 0.15 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 12 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The red-brown band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second red-brown band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetonitrile/toluene and allowed to stand for several days. The solid obtained was collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-bpy]: 75 mg (52%). Anal. Calcd for C58H116N5Cl5Re6S8·2CH3CN·0.7C7H8: C, 31.13; H, 4.98; N; 3.80%. Found: C, 31.13; H, 4.63; N, 3.79%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 3.09 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 7.64 (m, 4H, Hm), 8.71 (d, 2H, Ho), 9.53 (d, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 516 (sh, 220), 427 (sh, 1600), 324 (sh, 11 000), 272 (sh, 29 000), 240 (60 000), 226 (63 000).

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(cpy)] ((Bu4N)3[1-cpy])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and cpy (61 mg, 0.59 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 12 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The brown band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second brown band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetonitrile/diisopropyl ether and allowed to stand for several days. The solid obtained was collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-cpy]: 90 mg (64%). Anal. Calcd for C54H112N5Cl5Re6S8: C, 27.22; H, 4.74; N; 2.94%. Found: C, 27.29; H, 4.74; N, 3.12%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 3.09 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 7.56 (d, 2H, Hm), 9.65 (d, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 537 (250), 423 (sh, 2500), 334 (9400), 268 (sh, 28 000), 238 (sh, 55 000), 224 (79 000).

(Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl5(pz)] ((Bu4N)3[1-pz])

An air-saturated acetonitrile solution (10 mL) of (Bu4N)4[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (150 mg, 0.059 mmol) and pyrazine (pz) (47 mg, 0.59 mmol) was equally divided to five pyrex glass tubes (ϕ8 mm), and rubber stoppers were plugged in the tubes. The sample tubes were photo-irradiated by the Hg lamp for 12 h at room temperature with both lamp and sample tubes being cooled in a water bath. After the photoreaction, the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and then the solution was charged into a silica gel column (ϕ2.5 cm × 13 cm). The red-brown band was held on the top of the column. The first band with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was discarded. The second red-brown band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 3/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetonitrile/toluene and allowed to stand for several days. The solid obtained was collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)3[1-pz]: 83 mg (60%). Anal. Calcd for C52H112N5Cl5Re6S8: C, 26.48; H, 4.79; N; 2.97%. Found: C, 26.39; H, 4.55; N, 2.97%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 36H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 3.09 (m, 24H, Bu4N), 8.56 (d, 2H, Hm), 9.43 (d, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 530 (sh, 170), 423 (sh, 1600), 374 (sh, 3300), 268 (sh, 22 000), 237 (sh, 44 000), 225 (55 000).

(Bu4N)2[trans-, cis-{Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2}] ((Bu4N)2[2a-lut] and (Bu4N)2[2b-lut]) and (Bu4N)[mer-{Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(lut)3}] ((Bu4N)[3-lut])

A DMF solution (20 mL) of (Bu4N)3[Re6(μ3-S)8Cl6] (200 mg, 0.086 mmol) and lut (93 mg, 0.86 mmol) was refluxed 1 h. The mixture was evaporated to dryness and dissolved in dichloromethane and then charged into a silica gel column (2.5 cm × 15 cm). The orange band was held on the top of the column.

(Bu4N)[mer-{Re6(μ3-S)8Cl3(lut)3}] ((Bu4N)[3-lut])

The first orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 10/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetonitrile/toluene and allowed to stand for several days. The orange crystals obtained were collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)[3-lut]: 28 mg (16%). Anal. Calcd for C37H63N4Cl3Re6S8: C, 21.74; H, 3.11; N; 2.74%. Found: C, 21.59; H, 2.94; N, 2.79%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 12H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 8H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 8H, Bu4N), 2.28 (s, 18H, CH3), 3.07 (m, 8H, Bu4N), 7.60 (s, 2H, Hp), 7.61 (s, 1H, Hp), 9.00 (s, 4H, Ho), 9.06 (s, 2H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 423 (740), 378 (sh, 1600), 273 (22 000), 240 (sh, 29 000), 224 (sh, 48 000).

(Bu4N)2[trans-{Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2}] ((Bu4N)2[2a-lut])

The second orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 10/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetonitrile/toluene and allowed to stand for several days. The orange crystals obtained were collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)2[2a-lut]: 21 mg (11%). Anal. Calcd for C46H90N4Cl4Re6S8: C, 24.95; H, 4.10; N; 2.53%. Found: C, 24.92 H, 3.97; N, 2.56%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 24H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 16H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 16H, Bu4N), 2.27 (s, 12H, CH3), 3.08 (m, 16H, Bu4N), 7.55 (s, 2H, Hp), 9.01 (s, 4H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 428 (830), 380 (sh, 1800), 271 (24 000), 240 (sh, 36 000), 223 (58 000).

(Bu4N)2[cis-{Re6(μ3-S)8Cl4(lut)2}] ((Bu4N)2[2b-lut])

The third orange band eluted with dichloromethane/acetonitrile = 10/1 (v/v) was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residual was dissolved in acetonitrile/toluene and allowed to stand for several days. The orange crystals obtained were collected by filtration and then dried in air. Yield of (Bu4N)2[2b-lut]: 38 mg (20%). Anal. Calcd for C46H90N4Cl4Re6S8·CH3CN: C, 25.56; H, 4.16; N; 3.11%. Found: C, 25.71; H, 4.35; N, 2.76%. 1H NMR in CD3CN: δ/ppm = 0.96 (t, 24H, Bu4N), 1.36 (m, 16H, Bu4N), 1.59 (m, 16H, Bu4N), 2.28 (s, 12H, CH3), 3.08 (m, 16H, Bu4N), 7.57 (s, 2H, Hp), 9.06 (s, 4H, Ho). UV–vis in acetonitrile/nm (M–1 cm–1): 424 (800), 378 (sh, 2000), 271 (25 000), 240 (sh, 39 000), 224 (56 000).

Physical Measurements

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL ESA 400 MHz spectrometer. All peaks were referred to the methyl signal of tetramethylsilane (TMS) at δ = 0.00. CV was performed using an ALS 802D electrochemical analyzer. Working and counter electrodes comprised a glassy carbon disk and a platinum wire, respectively. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded at a scan rate of 100 mV/s. Sample solutions (ca. 1 mM) in 0.1 M (Bu4N)PF6–acetonitrile were deoxygenated by purging an Ar gas stream. The reference electrode used was an Ag/AgCl electrode, against which the half-wave potential of a ferrocenium ion/ferrocene couple (Fc+/Fc) was +0.43 V. UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on a JASCO V-550 spectrophotometer. For photophysical measurements, sample solids were placed between two nonfluorescent glass plates, and solution samples were deoxygenated by purging an Ar gas stream for at least 15 min and then sealed. A pulsed Nd3+:YAG laser (Lotis TII Ltd., 355 nm, fwhm ∼6 ns or continuum, 355 nm, fwhm 4–6 ns) was used as an exciting light source. Corrected emission spectra were recorded on a red-sensitive multichannel photodetector (Hamamatsu Photonics, PMA-12), and the emission lifetime was measured by using a streak camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, C4334). Emission quantum yields were estimated by using (Bu4N)4[Re6S8Cl6] (Φem = 0.039) in acetonitrile as a standard.

X-ray Structural Determinations

Single crystals of (Bu4N)3[1-dmap] and (Bu4N)3[1-lut] were obtained by recrystallization from dichloromethane/benzene and dichloromethane/diisopropyl ether, respectively. Single crystals of (Bu4N)2[2b-lut] were afforded by recrystallization from acetonitrile/diisopropyl ether. Single crystals of (Bu4N)3[1-cpy] and (Bu4N)[3-lut] were obtained by recrystallization from acetonitrile/toluene. The crystallographic measurements were conducted on a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy Custom diffractometer or Rigaku R-AXIS RAPID diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation at −103 °C. Single-crystal X-ray structures were determined using SHELXS (2008) or SHELXT (2018).101,102 Structural refinements were performed by the full-matrix least-squares method using SHELXL (version 2018).103 Olex2 was used for the calculations. Crystallographic data for the structures have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center: CCDC 2161366–2161372.

Computational Methods

DFT calculations were performed using the Amsterdam Modeling Suite (AMS 2020) package.104 For geometry optimizations and calculation of frequency calculations, structural optimizations were performed at the GGA level using PBE, the scalar relativistic ZORA (zero order regular approximation), and TZP for all atoms as provided in the ADF basis set library.105 The calculations of all positive IR frequencies confirmed the existence of the potential minimum. The single-point calculations were performed using the optimized geometries at B3LYP, scalar relativistic ZORA, and TZP for all atoms as provided in the ADF basis set library. The calculations used the COSMO solvent model for acetonitrile.106

Acknowledgments

This work was the result of using research equipment shared in MEXT Project for promoting public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (program for supporting construction of core facilities) grant number JPMXS0441200021. This study was partially supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (21H01862).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c03834.

Crystallographic data, calculated bond distances and angles, calculated energies and components of MOs near frontier orbital levels, plot of bond distances against pKa of the ligand or net charge of the complex anion, cyclic voltammograms, UV–vis absorption spectra, emission spectra, calculated energy diagrams, plot of redox potential against pKa, Hammett substitution constant, 1H NMR chemical shift value, sum of Lever electrochemical parameters, plot of absorption energy against ΔEredox values, and plot of emission energy against absorption energy or ΔEredox values (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gray H. B.; Maverick A. W. Solar Chemistry of Metal Complexes. Science 1981, 214, 1201–1205. 10.1126/science.214.4526.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juris A.; Balzani V.; Barigelletti F.; Campagna S.; Belser P.; von Zelewsky A. Ru(II) Polypyridine Complexes: Photophysics, Photochemistry, Eletrochemistry, and Chemiluminescence. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1988, 84, 85–277. 10.1016/0010-8545(88)80032-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage J. P.; Collin J. P.; Chambron J. C.; Guillerez S.; Coudret C.; Balzani V.; Barigelletti F.; De Cola L.; Flamigni L. Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) Bis(terpyridine) Complexes in Covalently-Linked Multicomponent Systems: Synthesis, Electrochemical Behavior, Absorption Spectra, and Photochemical and Photophysical Properties. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 993–1019. 10.1021/cr00028a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balzani V.; Juris A.; Venturi M.; Campagna S.; Serroni S. Luminescent and Redox-Active Polynuclear Transition Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 759–834. 10.1021/cr941154y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzani V.; Bergamini G.; Campagna S.; Puntoriero F. Photochemistry and Photophysics of Coordination Compounds: Overview and General Concepts. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 280, 1–36. 10.1007/128_2007_132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lever A. B. P.; Dodsworth E. S.. Inorganic Electronic Structure and Spectroscopy, Volume II: Applications and Case Studies; Wiley, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lever A. B. P.Ligand Electrochemical Parameters and Electrochemical-Optical Relationships. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II; McCleverty J. A., Meyer T. J., Ed.; Pergamon, 2003; pp 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Lever A. B. P. Electrochemical Parametrization of Metal Complex Redox Potentials, Using the Ruthenium(III)/ruthenium(II) Couple to Generate a Ligand Electrochemical Series. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 1271–1285. 10.1021/ic00331a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lever A. B. P. Electrochemical Parametrization of Rhenium Redox Couples. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 1980–1985. 10.1021/ic00009a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou C.; Lever A. B. P. Tuning Metalloporphyrin and Metallophthalocyanine Redox Potentials using Ligand Electrochemical (EL) and Hammett (σp) Parametrization. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 216–217, 45–54. 10.1016/S0010-8545(01)00350-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pombeiro A. J. L. Electron-donor/acceptor Properties of Carbynes, Carbenes, Vinylidenes, Allenylidenes and Alkynyls as Measured by Electrochemical Ligand Parameters. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 6021–6040. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.07.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pombeiro A. J. L. Characterization of Coordination Compounds by Electrochemical Parameters. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 1473–1482. 10.1002/ejic.200601095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Substituent Effects in Dinuclear Paddlewheel Compounds: Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Investigations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998, 175, 43–58. 10.1016/S0010-8545(98)00202-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toma H. E.; Araki K.; Alexiou A. D. P.; Nikolaou S.; Dovidauskas S. Monomeric and Extended Oxo-centered Triruthenium Clusters. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 219–221, 187–234. 10.1016/S0010-8545(01)00326-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T. Rhenium Sulfide Cluster Chemistry. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1999, 97–106. 10.1039/a806651e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel J.-C. P.; Boubekeur K.; Uriel S.; Batail P. Chemistry of Hexanuclear Rhenium Chalcohalide Clusters. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2037–2066. 10.1021/cr980058k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray T. Hexanuclear and Higher Nuclearity Clusters of the Groups 4-7 Metals with Stabilizing π-donor Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 243, 213–235. 10.1016/s0010-8545(03)00083-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y.; Abe M. Ligand-ligand Redox Interaction through Some Metal-cluster Units. Chem. Rec. 2004, 4, 279–290. 10.1002/tcr.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y. Recent Progress in the Chemistry of Rhenium Cluster Complexes and Its Relevance to the Prospect of Corresponding Technetium Chemistry. J. Nucl. Radiochem. Sci. 2005, 6, 145–148. 10.14494/jnrs2000.6.3_145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welch E. J.; Long J. R.. Atomlike Building Units of Adjustable Character: Solid-State and Solution Routes to Manipulating Hexanuclear Transition Metal Chalcohalide Clusters. Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005; Vol. 54, pp 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov V. E.; Mironov Y. V.; Naumov N. G.; Sokolov M. N.; Fedin V. P. Chalcogenide Clusters of Group 5-7 Metals. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2007, 76, 529–552. 10.1070/rc2007v076n06abeh003707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.; Fedorov V. E.; Kim S.-J. Novel Compounds Based on [Re6Q8(L)6]4– (Q = S, Se, Te; L = CN, OH) and Their Applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 7178–7190. 10.1039/b903929p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin A.; Perrin C. State-of-Art and New Trends in Transition Metal Clusters. J. Cluster Sci. 2009, 20, 1–7. 10.1007/s10876-009-0231-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin A.; Perrin C. Low-Dimensional Frameworks in Solid State Chemistry of Mo6 and Re6 Cluster Chalcohalides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 3848–3856. 10.1002/ejic.20110040010.1002/ejic.201100400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin A.; Perrin C. The Molybdenum and Rhenium Octahedral Cluster Chalcohalides in Solid State Chemistry: From Condensed to Discrete Cluster Units. C. R. Chim. 2012, 15, 815–836. 10.1016/j.crci.2012.07.00410.1016/j.crci.2012.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z. Chemical Transformations Supported by the [Re6(μ3-Se)8]2+ Cluster Core. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 5121–5131. 10.1039/c2dt00007e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumov N. G.; Brylev K. A.; Mironov Y. V.; Cordier S.; Fedorov V. E. Octahedral Clusters with Mixed Inner Ligand Environment: Self-assembly, Modification and Isomerism. J. Struct. Chem. 2014, 55, 1371–1389. 10.1134/S002247661408001010.1134/s0022476614080010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura N.; Kuwahara Y.; Ueda Y.; Ito Y.; Ishizaka S.; Sasaki Y.; Tsuge K.; Akagi S. Excited Triplet States of [{Mo6Cl8}Cl6]2–, [{Re6S8}Cl6]4–, and [{W6Cl8}Cl6]2– Clusters. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2017, 90, 1164–1173. 10.1246/bcsj.20170168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Castro A.; Paez-Hernandez D.; Arratia-Perez R. Rhenium Hexanuclear Clusters: Bonding, Spectroscopy, and Applications of Molecular Chevrel Phases. Struct. Bond 2019, 180, 109–123. 10.1007/430_2019_34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long J. R.; McCarty L. S.; Holm R. H. A Solid-State Route to Molecular Clusters: Access to the Solution Chemistry of [Re6Q8]2+ (Q = S, Se) Core-Containing Clusters via Dimensional Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4603–4616. 10.1021/ja960216u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray T. G.; Rudzinski C. M.; Nocera D. G.; Holm R. H. Highly Emissive Hexanuclear Rhenium(III) Clusters Containing the Cubic Cores [Re6S8]2+ and [Re6Se8]2+. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 5932–5933. 10.1021/ic991195i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbaud C.; Deluzet A.; Domercq B.; Molinié P.; Boubekeur K.; Batail P.; Coulon C. NBun4+)3[Re6S8Cl6]3-.: Synthesis and Luminescence of the Paramagnetic, Open Shell Member of a Hexanuclear Chalcohalide Cluster Redox System. Chem. Commun. 1999, 18, 1867–1868. 10.1039/a904669k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura T.; Ishizaka S.; Umakoshi K.; Sasaki Y.; Kim H.-B.; Kitamura N. Hexarhenium(III) Clusters [Re6(μ3-S)8X6]4– (X– = Cl–, Br–, I–) are Luminescent at Room Temperature. Chem. Lett. 1999, 28, 697–698. 10.1246/cl.1999.697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura T.; Ishizaka S.; Sasaki Y.; Kim H.-B.; Kitamura N.; Naumov N. G.; Sokolov M. N.; Fedorov V. E. Unusual Capping Chalcogenide Dependence of the Luminescence Quantum Yield of the Hexarhenium(III) Cyano Complexes [Re6(μ3-E)8(CN)6]4–, E2– = Se2– > S2– > Te2–. Chem. Lett. 1999, 28, 1121–1122. 10.1246/cl.1999.1121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura T.; Umakoshi K.; Sasaki Y.; Sykes A. G. Synthesis, Structures, and Redox Properties of Octa(μ3-sulfido)hexarhenium(III) Complexes Having Terminal Pyridine Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 5557–5564. 10.1021/ic9907922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]