Abstract

Percutaneous vertebroplasty has emerged as an increasingly popular intervention for managing a variety of common spinal conditions. Nevertheless, kyphoplasty cement can accidentally leak into paravertebral venous plexus, then travel to the right heart chambers through the venous system. We report an exceedingly rare case of an intracardiac cement embolism, likely an inadvertent complication of a recent percutaneous lumbar vertebroplasty. A mobile mass was incidentally found during a cardiac catheterization procedure, most likely in right atrium. Subsequent computed tomography angio chest and cardiac imaging confirmed a floating foreign body in the right atrium, which was then retrieved successfully through an endovascular approach. Gross examination of the removed body confirmed a bone cement-like material. Intracardiac cement embolism warrants serious attention as it may result in catastrophic cardiac complications.

Learning objective

Intracardiac cement embolism is an extremely rare, but potentially life-threatening complication after percutaneous vertebroplasty. The bone cement fragments accidentally leak into paravertebral plexus and then via venous system into the right-sided cardiac chambers and pulmonary arteries.

Keywords: Bone cement, Endovascular approach, Intracardiac cement embolism, Percutaneous vertebroplasty

Introduction

Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) has gained vast popularity in the past three decades. A rare complication may include migration of bone cement (made of either calcium phosphate or magnesium phosphate) fragments through paravertebral plexus and then via azygous venous system into the right-sided cardiac chambers and pulmonary arteries [1,2]. Although, intrapulmonary cement embolization following vertebral instrumentation is relatively an uncommon occurrence, intracardiac cement embolization (ICE) remains an important and potentially devastating complication [3]. Clinical manifestations range widely from being asymptomatic and only an incidentally detected finding, in the majority of cases, to valvular dysfunction, and even life-threatening cardiac tamponade when the cement causes free wall cardiac rupture requiring emergent surgical intervention [4,5]. In this report, we present a rare case of an incidental ICE which was suspected during a cardiac catheterization when a mobile structure was visualized over the projected area of the right atrium, most likely complicating a recent PVP of multiple lumbar vertebrae. The cement was successfully removed through an endovascular approach with an unremarkable patient's recovery. The current literature is reviewed, and most of the published cases of ICE following PVP are briefly presented in this report.

Case report

A 74-year-old female with a significant past medical history of coronary artery disease (CAD) with remote percutaneous coronary intervention in 2014, and degenerative lumbar spine spondylosis status-post PVP in April 2021 presented to the emergency department with chest pain and shortness of breath for two days (September 2021). Electrocardiogram on admission showed new diffuse ST segment depressions. High sensitivity troponin raised dynamically from 32 pg/ml to 672 pg/ml (normal reference 0–10 pg/ml) over 3 h. The diagnosis of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction was made.

The patient underwent an urgent left heart catheterization (LHC) which revealed diffuse calcified CAD with small-vessel disease as etiology of the patient's clinical presentation and was deemed best served with medical management. Surprisingly, a mobile radiopaque non-coronary structure was visualized over the projected area of the right atrium (RA) on fluoroscopy (Fig. 1A, Video 1), which represented a new interval finding compared to the patient's last LHC performed almost a year previously (September 2020) when the patient presented with similar symptoms (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Left heart catheterization (LHC) on right coronary artery left anterior oblique view. New radiopaque noncardiac mobile structure (white arrow) was visualized around right atrial area (A) compared to previous LHC in 2020 (B).

RCA, right coronary artery.

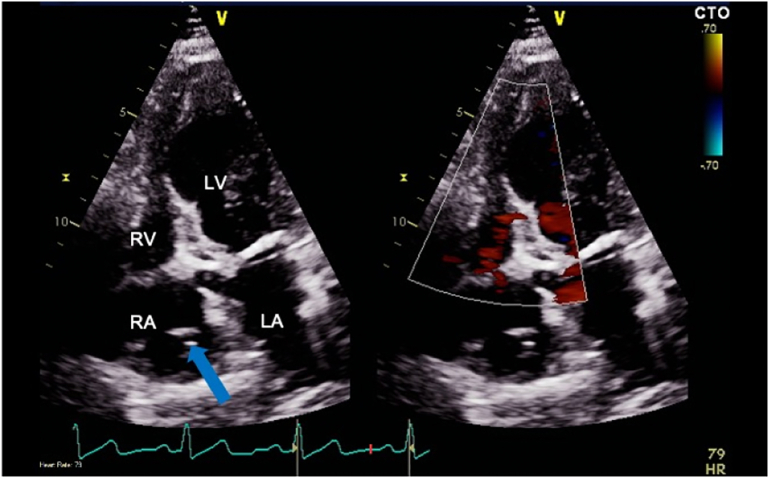

Further cardiac imaging with a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a floating foreign body in the RA extending caudally into the cranial end of inferior vena cava (IVC) as shown in Fig. 2 and Video 2. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest similarly depicted a foreign body in the right heart without evidence of pulmonary emboli (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram on apical four-chamber view. A foreign body in right atrium extending caudally into the cranial end of the inferior vena cava.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Fig. 3.

A computed tomography scan of the chest. A foreign body (blue arrow) in the right atrium seen on the bone window.

The patient was hemodynamically stable, had no pulmonary emboli on chest CT imaging, and had no evidence of gross valvular dysfunction, pericardial effusion, or new wall motion defects on TTE. After having multispecialty discussion, it was decided to proceed with an endovascular approach for the foreign body retrieval by interventional radiology services. An endovascular approach was performed through the right common femoral vein under ultrasound guidance. A 10-French sheath was advanced over a wire to IVC, then a gooseneck snare and ensnare device were used. A linear looped foreign body in pieces from the cranial end of the IVC was successfully retrieved (Online Fig. 1).

Online Fig. 1.

Fluoroscopic guided IV foreign body retrieval. A looped foreign body from the cranial end of the inferior vena cava was identified on fluoroscopy.

Pathologic analysis of the 1 × 0.5 × 0.5 cm hard foreign body was consistent with a bone cement material (part of it shown in Online Fig. 2), in keeping with an intracardiac bone cement embolism following recent PVP that the patient underwent five months prior to her index presentation.

Online Fig. 2.

A 1 × 0.5 × 0.5 cm hard foreign body consistent with bone cement material.

Discussion

ICE represents a rare complication of PVP with a reported incidence of 3.9% in one retrospective cohort [3]. Symptomatic ICE is an even rarer phenomenon, with only 8.3% of total ICE cases being symptomatic in the latter cohort [3]. Nevertheless, ICE should be considered seriously as catastrophic cardiac events have been previously reported [1,4,5]. The size of cement emboli usually varies from small fragments to larger particles that may result in vascular occlusion or interference with valvular function and cause critical hemodynamic compromise [1]. Associated pulmonary embolization was also reported [3]. Furthermore, previous cases of right ventricular wall injury were documented due to sharp cement shards [6,7]. Paradoxical systemic embolization was described in the presence of interatrial communication [8].

Some risks factors for ICE following PVP were previously reported. Thoracic vertebrae instrumentation, presence of spinal metastasis, and a higher number of instrumented vertebrae during the same session were associated with an increased risk of ICE [8]. The procedure with multiple vertebrae fusions (L1-L5) that our patient underwent might be one of the risk factors for developing ICE.

Most of the reviewed cases underwent operative management to remove the cements. A robotic-assisted endoscopic right atriotomy was employed in one patient [9], and an endovascular approach was successful in another one [10]. After literature review, we concluded that an individualized approach was followed in each case according to a multitude of patient-specific characteristics and approach-related factors tailored to each patient's condition, physician's level of expertise and available resources. For instance, in one patient with an ICE that was traversing the tricuspid valve into the pulmonary valve, an endovascular approach was dismissed due to the proximity of cement to tricuspid valve leaflets, length of cast, and presence of patent foramen ovale with a risk of systemic embolization, and interdisciplinary discussions favored operative consensus [2]. Patients who sustained cement-induced atrial or ventricular wall perforation with pericardial effusion understandably warranted urgent operative intervention [6,7].

Conclusion

ICE is a rare complication after PVP. The majority of ICE cases remain asymptomatic, but serious complications of cement-induced valvular dysfunction and life-threatening cardiac tamponade have been reported. The onset of symptomatic ICE range widely following PVP. The current evidence regarding the management of ICE following PVP remains limited and most of the data were driven from isolated case reports and case series. An individualized approach is followed for managing ICE and a number of options are described tailored to each particular case.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

A mobile radiopaque non-coronary structure was visualized over the projected area of the right atrium (RA) on fluoroscopy.

A floating foreign body in the RA extending caudally into the cranial end of inferior vena cava (IVC).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Henderson R. Expert’s comment concerning Grand Rounds case entitled “Intracardiac bone cement embolism as a complication of vertebroplasty: Management strategy” by Hatzantonis C, Czyz M, Pyzik R, Boszczyk BM. (Eur Spine J; 2016. doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4695-x) Eur Spine J. 2017;26:3206–3208. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassawon R., Sirajjudin S., Martucci G., Shum-Tim D. Snare or scalpel: challenges of intracardiac cement embolism retrieval. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113:e107–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fadili Hassani S., Cormier E., Shotar E., Drir M., Spano J.P., Morardet L., et al. Intracardiac cement embolism during percutaneous vertebroplasty: incidence, risk factors and clinical management. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:663–673. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim S.P., Son B.S., Lee S.K., Kim D.H. Cardiac perforation due to intracardiac bone cement after percutaneous vertebroplasty. J Card Surg. 2014;29:499–500. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang T.Z., Zhu H.P., Gao B., Peng Y., Gao W.J. Intracardiac, pulmonary cement embolism in a 67-year-old female after cement-augmented pedicle screw instrumentation: a case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:3120–3129. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i13.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuerer S., Misfeld M., Schuler G., Mangner N. Intracardiac cement embolization in a 65-year-old man four months after multilevel spine fusion. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:783. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swojanowsky P., Brinkmeier-Theofanopoulou M., Schmitt C., Mehlhorn U. A rare cause of pericardial effusion due to intracardiac cement embolism. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3001. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shridhar P., Chen Y., Khalil R., Plakseychuk A., Cho S.K., Tillman B., et al. A review of PMMA bone cement and intra-cardiac embolism. Materials (Basel) 2016;9:821. doi: 10.3390/ma9100821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molloy T., Kos A., Piwowarski A. Robotic-assisted removal of intracardiac cement after percutaneous vertebroplasty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:1974–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.06.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan H.Y., Wu T.Y., Chen H.Y., Wu J.Y., Liao M.T. Intracardiac cement embolism: images and endovascular treatment. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.011849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A mobile radiopaque non-coronary structure was visualized over the projected area of the right atrium (RA) on fluoroscopy.

A floating foreign body in the RA extending caudally into the cranial end of inferior vena cava (IVC).