Abstract

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is essential for practical and theoretical efforts to protect biodiversity. However, species classified as “Data Deficient” (DD) regularly mislead practitioners due to their uncertain extinction risk. Here we present machine learning-derived probabilities of being threatened by extinction for 7699 DD species, comprising 17% of the entire IUCN spatial datasets. Our predictions suggest that DD species as a group may in fact be more threatened than data-sufficient species. We found that 85% of DD amphibians are likely to be threatened by extinction, as well as more than half of DD species in many other taxonomic groups, such as mammals and reptiles. Consequently, our predictions indicate that, amongst others, the conservation relevance of biodiversity hotspots in South America may be boosted by up to 20% if DD species were acknowledged. The predicted probabilities for DD species are highly variable across taxa and regions, implying current Red List-derived indices and priorities may be biased.

Subject terms: Biodiversity, Ecological modelling, Machine learning, Conservation biology

Data Deficient species are more likely to be at extinction risk than previously thought across multiple taxonomic groups.

Introduction

Measuring ongoing and anticipating potential threats is vital for preventing damage to the natural world1–8, which entails detailed knowledge about the current state of biodiversity. A central data resource enabling a multitude of overarching analyses in conservation and sustainability science9 is the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List of Threatened Species (hereafter: Red List). The Red List assesses extinction risks and reports Red List categorization for more than 140,000 species based on a set of quantitative criteria10 relying for instance on extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, population trends, or population size. However, the sheer amount of known and unknown species globally11,12, the dynamic nature of threats and trends7, and limited human resources for undertaking such Red List assessments13,14 turn this critical endeavour into a Sisyphean task.

Consequently, only a small proportion of known species have been assessed for their conservation priority so far15,16, unevenly distributed across space, time and taxa13,16. In addition, numerous assessed species are classified as Data Deficient (DD) even in otherwise comprehensively assessed species groups. A species is considered DD if there is “inadequate information to make a direct, or indirect, assessment of its risk of extinction based on its distribution and/or population status”17. More specifically Bland et al. identified 8 main justifications as to why species are assessed as DD: uncertain provenance, type series, few records (<5), old records (before 1970), uncertain population status or distribution, uncertain threats, new species (discovered in the last 10 years), and taxonomic uncertainty18. In parallel, Butchart and Bird stated that the DD category “is probably the most controversial and misunderstood Red List category”19. One of the main reasons are value choices when dealing with uncertainty and applying the IUCN Guidelines. If, due to uncertain data, a species can be listed as Critically Endangered (CR) and Least Concern (LC), the species should be listed as DD. However, if the assessor considers a species being not LC but is unsure about its exact threat-level, DD is not the appropriate category. In this case, the assessor needs to decide and assign the species to a category, i.e., risk tolerance. It is important to note that we do not distinguish the DD species according to the reason for their classification as DD17.

On average across all taxa and regions, one of six assessed species is classified as DD15,18,20. Although DD species are sometimes treated as being not threatened21, studies suggest that they are of particular conservation importance because a higher portion of them may be threatened by extinction compared to data-sufficient (DS) species22–24. However, since DD species could belong to any Red List category, they are difficult to handle for practitioners21,25 and are therefore generally ignored in studies analysing biodiversity impacts and change26,27. For instance, the Red List Index27 is built upon well-assessed threat-levels for individual species at several points in time and directly applied in, e.g., sustainable development goals28 and biodiversity targets29. In addition, studies linking biodiversity loss to global trade footprints30,31 and approaches to transform threat-levels to numerical conservation indicators32 have ignored DD species. Similarly, the recently suggested metric26 for measuring success of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework will not be applicable for DD species.

In stark contrast, the continuous growth in knowledge turnover during the digital era has resulted in constant improvement in the availability of global data on biodiversity, human activities, and environmental threats33. Statistical tools, such as machine learning (ML), can detect relevant signals in large datasets, thereby offering a time- and cost-effective approach to tackle data deficiency34–37. The utility of ML models for predicting species’ extinction risk or conservation status was successfully proven for species in single taxonomic groups with great accuracy24,38–44, regionally as well as globally. However, such predictions are needed consistently for all relevant species to effectively benefit global conservation and sustainability analyses16.

Here, we present a global multitaxon ML classifier that predicts the probability of being threatened by extinction (hereafter: PE score) based on, amongst others, species taxonomy, range extent, and summarized stressors (min., max., mean and median) within species range maps, as well as species occurrence cells (0.5-degree cells). The classifier was trained and tested on threat levels for 28,363 DS species, drawing on selected features out of more than 400 predictors, human pressures, and environmental stressors. We applied the classifier to predict PE scores for DD species (n = 7699) that include range maps of their distribution in their IUCN Red List database record (Version 2020-3)45,46, to our knowledge the largest data provider of range maps for thousands of species. Since biodiversity varies greatly through space, it is crucial to perform assessments in a spatially explicit way and include their entire spatial extent.

Results and discussion

Classifier performance

The trained classifier was able to successfully separate between threatened and non-threatened species within a set-aside testing dataset, as well as continuous predictions (i.e., PE scores) (Fig. 1). The binary classifier obtained an overall accuracy of 85% (Table 1), being more precise in predicting which species are not threatened by extinction than in predicting which species are threatened. 93% and 92% of species that we predicted to be not threatened were indeed not threatened (for marine and non-marine species respectively). Hence, with only 7–8% of negative predictions (i.e., predicted as not threatened) being incorrect, we are confident that our binary classifier avoids underestimating the conservation status of most taxa. Instead, the binary classifier may be prone to overestimating the status of some taxa; only 60% to 67% of species that we predicted to be threatened are also classified as threatened by the IUCN (for marine and non-marine species respectively). The continuous classifier, however, seems to only underestimate the risk for marine species when directly compared to non-marine species. The relative ranking of continuous predictions within the groups remains valid for all species (AUC = 0.91, AUCPR = 0.80, Gini-Coefficient = 0.82) and across taxonomic classes (Supplementary Table 1). Hence, on average, species being threatened by extinction obtain higher predicted PE scores than not threatened species, for both marine and non-marine species (Fig. 1). Binary as well as continuous predictions across marine versus non-marine groups perform well but are not directly comparable.

Fig. 1. Predicted scores for threatened versus not threatened species.

Boxplot showing the interquartile range (box), median (black line), minimum and maximum values without outliers (error bars), and outliers (points) of predicted probability of being threatened by extinction (PE score) across the actual IUCN assessment (not threatened and threatened) for marine (n = 875) and non-marine (n = 5982) species in the set-aside testing data.

Table 1.

Classifier performance.

| Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Not threatened | Threatened | Not threatened | Threatened |

| Not threatened | 695 (26) | 54 (10) | 3786 (20) | 309 (4) |

| Threatened | 51 (8) | 75 (25) | 616 (7) | 1271 (23) |

| Marine species | Non-marine species | |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.88 (0.74) | 0.85 (0.80) |

| Specificity | 0.93 (0.76) | 0.86 (0.74) |

| Sensitivity | 0.58 (0.71) | 0.80 (0.85) |

| Negative Pred. Value | 0.93 (0.72) | 0.92 (0.83) |

| Positive Pred. Value | 0.60 (0.76) | 0.67 (0.77) |

| Balanced Accuracy | 0.76 (0.74) | 0.83 (0.80) |

Confusion matrix and resulting performance measures for marine and non-marine species based on the set-aside testing data (25% of the dataset) and based on formerly Data Deficient species (n = 123) in IUCN version 2021-2 (in brackets).

We further tested our classifier against an IUCN update (Version 2021-2)15 that was released after our model was trained (Supplementary Fig. 1). In this update, we found that 123 former DD species from Version 2020-3 were now assigned a threat-level. Our classifier labelled 94 of those species (76%) correctly (Table 1), being equally precise in predicting whether the species was threatened (76%) or not threatened (77%) but more accurate for non-marine (80%) than for marine species (74%).

Data deficient species are more threatened by extinction than data-sufficient species

On average we obtained higher PE scores for DD species (43%) than for DS species (26%), resulting in 56% of DD species (n = 4336) predicted to be threatened by extinction (Supplementary Table 1) versus 28% of DS species46. The generated predictions reinforce the concern that DD species are of high conservation interest21,25 and, given the large variance in predicted probabilities of being threatened (Supplementary Fig. 2), highlight the importance of treating DD species individually.

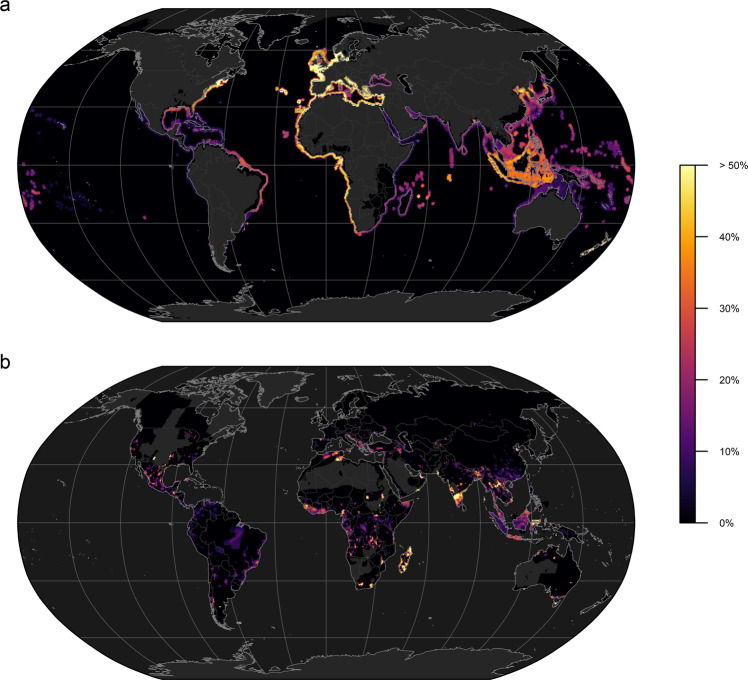

On land, these likely threatened DD species are scattered across all continents and are often geographically restricted to smaller ranges (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 3), such as in central Africa, Madagascar and southern Asia. The greatest number of threatened marine DD species are found in south-eastern Asia, followed by the eastern Atlantic coastline as well as numerous atolls and islands (Supplementary Fig. 4). In fact, between a third and half of marine DD species around the world’s coastlines were predicted to be threatened by extinction, most notably along the eastern Atlantic coastline including the Mediterranean basin (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Potentially threatened fraction of data deficient species.

Fraction of Data Deficient species (n = 7699, IUCN Version 2020-3) predicted to be threatened by extinction for marine (a) and non-marine species (b) according to our machine learning classifier.

In addition to roughly 40% of Data Deficient ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii), malacostracans (Malacostraca), bivalves, snails and slugs (Gastropoda), we found a staggering 960 out of 1130 (85%) Data Deficient amphibians (Amphibia), and more than half of Data Deficient anthozoans (Anthozoa; marine invertebrates including anemones and corals), insects (Insecta), mammals (Mammalia) and reptiles (Reptilia) likely to be threatened by extinction (Supplementary Table 1).

This is highly relevant for conservation and sustainability analyses, as some of these groups are amongst the most frequently considered ones7. More specifically, the classification of DD amphibians, mammals, and reptiles is likely to further increase both the absolute and relative number of species threatened by extinction in these taxonomic groups. For instance, an additional 14% of amphibians were predicted to be threatened by our ML classifier. This would raise the relative number of amphibian species being threatened by extinction from 39% to 47%. Similarly, the fraction of threatened mammals and reptiles likely increases when accounting for DD species (from 26% to 31% and 19% to 25%, respectively; Supplementary Table 1).

For selected species groups, models that suggest Red List categories or probabilities of being threatened for DD species exist, e.g., for amphibians24, reptiles38, terrestrial mammals39 or sharks and rays43. Howard and Bickford found 63% of DD amphibians to be threatened, mostly in South America, central Africa and North Asia, but also state that this is an underestimation24. Our model predicts 85% of DD amphibians to be threatened. Bland and Böhm identified 19% out of 292 DD terrestrial reptile species as threatened38, while our model identified 59% of reptiles as threatened, but we include over 1000 species and terrestrial, freshwater and marine species, the latter of which are thought to be more likely to be threatened47. The regions for conservation priorities for both reptiles and amphibians match those previously found, which are congruent with known hotspots for threatened species38. A previous assessment for terrestrial mammals identified 64% of DD terrestrial mammals as threatened39, while our model classifies 61% of DD terrestrial and marine mammals as threatened. Sharks and rays in the Mediterranean and North East Atlantic were modelled to contain 62% and 55% threatened species, respectively44. On a global scale, we found 26% of DD species in this group to be threatened (Supplementary Table 1). This is concordant with Dulvy et al., which found every fourth species of the ray and shark family to be threatened with extinction and who found the Mediterranean to be a hotspot for extinction48, explaining the large discrepancy of the local values to our global one.

Data-deficiency causes regionally biased conservation priorities

The high variance found in the predicted probabilities of being threatened by extinction (i.e., PE scores) at the species level implies that more accurate assessments of DD species could shift regional conservation priorities. We predicted higher PE scores for DD than for DS species in most regions of the world (Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting that current conservation concerns could, in fact, be underestimated. In marine systems, however, this seems to be restricted to coastal waters as well as high latitudes.

DD species in marine systems seem to be most relevant around the world’s coastlines, as well as around temperate to tropical islands and atolls, but less relevant in international waters (Fig. 3a). For instance, we found an increase in average PE score by more than 20% once DD were considered alongside DS species in e.g., the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean and south America’s Atlantic coast (Fig. 3a). Even in biodiversity-rich regions the average PE score increased another 10% to 15% due to the extant DD species, such as in the Gulf of Guinea and South-eastern Asian seas. Here, numerous DD reef forming corals, sharks, rays, chimaeras, and marine fish species seem to be particularly relevant for a timely and expert-based threat assessment (Supplementary Figs. 3, 6). In contrast, including DD species did not change or even lowered the average PE score in large parts of international seas (Fig. 3a). Although marine biodiversity as we know it today is richest in coastal waters49, these results should be interpreted with caution because the underlying range maps for many marine species can be too coarse50, which may be especially true for DD species in international seas.

Fig. 3. Data Deficient species change conservation priorities.

Percent change in average PE score (i.e., predicted probability of being threatened by extinction) for marine (a) and non-marine species (b) following the inclusion of Data Deficient species alongside data-sufficient species.

Furthermore, DD species on land (i.e., strictly non-marine species) seem to have the potential to regionally boost the conservation relevance in most of the world’s megadiverse countries51. Across Central to South America, we found a widespread increase of 10% to 20% in average PE score when including DD in addition to DS species (Fig. 3b). Notably, often only few taxonomic groups accounted for most of the observed increase in average PE score (Supplementary Fig. 6). For instance, the addition of predicted scores for DD amphibians, reptiles, mammals, rays and other freshwater groups in large parts of South America resulted in a widespread increase in average PE score, including for example the Amazon basin, the tropical Andes, the Atlantic Forest and Cerrado. However, these estimates are based on limited taxonomic groups and may be different if spatially explicit range maps for more taxa were available (e.g., plants).

In Africa, DD amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and freshwater ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) increased the average PE score locally across freshwater systems (e.g., Lake Victoria), tropical rainforests and savannas throughout the continent (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 6). We further discovered an increase in average PE score in numerous smaller isolated patches distributed around the world once DD extant species’ scores were acknowledged, such as in the Northern Territory and the Murray–Darling basin of Australia. Overall, the potential effects on PE score due to DD species were much more restricted to a regional level on land compared to marine systems, presumably due to spatially more explicit, and restricted, range maps for DD species on land.

Conclusion

Previously, the risk of misjudging the importance of individual DD species outweighed the benefits of including them in Red List applications, resulting in regionally biased conservation prioritization. This study suggests that automatized classifiers built on species’ range maps and species observations can provide accurate and rapid pre-assessments on a large, global, and multitaxon scale. In contrast to previous approaches, our classifier is able to provide standardized predictions across multiple taxonomic groups16, making results between taxa directly comparable. The presented results show that DD species vary greatly in probability of being threatened by extinction, indicating a highly heterogenous bias that propagates into consequential Red List applications. As such, inferences built upon Red List-derived numbers of threatened species30 as well as numerically converted threat-levels32 could be biased. The generated predictions (i.e., PE scores) could facilitate the inclusion of DD species in sustainability-relevant applications27 and modelling approaches26. We encourage the extended use of our algorithm for screening for updates14 in the status of DS species, as well as large-scale pre-assessments of species not yet evaluated by the IUCN42 for a targeted completion of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Methods

Species data

We retrieved all spatial range map datasets (i.e., mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, marine groups, selected vascular plant groups and freshwater groups) available at the IUCN Red List (https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/spatial-data-download, Version 2020-3)45,46 in March 2021, covering 44,924 species in the following taxonomic classes: Actinopterygii, Agaricomycetes, Amphibia, Anthozoa, Aves, Bivalvia, Branchiopoda, Bryopsida, Cephalaspidomorphi, Charophyaceae, Chondrichthyes, Clitellata, Gastropoda, Hydrozoa, Insecta, Jungermanniopsida, Lecanoromycetes, Liliopsida, Lycopodiopsida, Magnoliopsida, Malacostraca, Mammalia, Myxini, Polypodiopsida, Reptilia and Sarcopterygii. Range maps for bird species were not downloaded separately, because of their limited number of DD species. Species taxonomy, native countries, environmental domain (i.e., the occurrence in terrestrial, freshwater, marine systems and combinations thereof) and Red List category were available from IUCN for all species, i.e., Least Concern (LC), Lower Risk/Least Concern (LR/LC), Lower Risk/Conservation Dependent (LR/CD), Near Threatened (NT), Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), Critically Endangered (CR), Extinct (EX), Extinct in the Wild (EW) and Data Deficient (DD). The spatial dataset consists of seasonal range maps (i.e., for each species one or several range maps out of “resident”, “breeding season”, “non-breading season”, “passage”, and “seasonal occurrence uncertain” were available). Only those range maps labelled as “native” and “extant” and only species that were not categorized as EW or EX were considered (n = 44,908 species).

Predictor data

The correlate variables are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Species taxonomy (i.e., taxonomic kingdom, phylum, and class) was included as potential predictor and surrogate for phylogenetic data42. Habitat preferences were retrieved from the Red List using rredlist52 in R. Occupied types of habitats as well as the number of different types of habitats, sub-habitats, and habitats of major importance were included as predictor. Occurrence data was retrieved from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)53 and the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS)54 using their corresponding application programming interfaces via the packages rgbif55 and robis56 in R. We only considered occurrence data that were collected between the years 2010 and 2020. For each species, we retrieved the maximum number of occurrence points per native country from GBIF (i.e., 100,000 data points per request), and for marine species, we additionally downloaded all data available from OBIS. The total number of occurrence points as well as the number of occurrence cells in a global grid (0.5-degree cells) was counted.

Because environmental threats can vary considerably across space and we expect the species to be exposed heterogeneously within their ranges, we extracted mean, minimum, maximum, and median values of environmental stressors and features across each species’ seasonal range map as well as its occurrence cells.

The included features were representative for the major drivers of biodiversity change, i.e. climate change, habitat change, overexploitation, invasive species and pollution57. As climatic dataset we retrieved all CHELSA bioclimatic variables58,59. The European Space Agency’s land cover product for the year 2015 in 300 m resolution60 was used to calculate fractions for different natural land cover types (n = 17). One raster was calculated per land cover class, representing the proportion of land covered by that class per cell. As general indicators of anthropogenic land use and land use change we included the global human footprint index61, including associated stressors such as population density, cropland area and pasture area, human modification index62, future urban expansion probabilities63, fraction of land designated to protected areas64, deforestation rates between the years 2000 and 201965, different habitat heterogeneity metrics66 and cumulative application rates of different pesticides67. We counted the number of power plants68 and dams69 within each species geographical range, and included country-specific water scarcity estimates70, annual streamflow71, stream connectivity indices72 as well as freshwater environmental variables73, including eutrophication, pollution and upstream land use fractions, to account for the most severe impacts in freshwater systems74,75. Illegal hunting activities remain problematic for many species76. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, global poaching data does not exist. Therefore, we included factors that may affect the rate of poaching on a global scale77,78, i.e., the human development index (HDI) in 2019, the average annual HDI growth between 1990–201979 and the corruption perceptions index (CPI) in 2020 at country-level80. We further included estimated threats from species invasions, country-specific capacities to respond to invasion81, a set of modelled impacts on marine ecosystems82,83 and marine environmental variables84,85. All layers were aggregated for computational efficiency by averaging to 0.5-degree cells (approximately 56 km at the equator).

Machine learning classifier

We aimed to estimate the probability of being threatened by extinction (hereafter: PE score) for DD species by training a machine learning classifier, fitted using species with known threat-levels. All DS species were reclassified into two groups based on their IUCN Red List categories: threatened by extinction (i.e., all species in the categories VU, EN, and CR) and not threatened by extinction (i.e., all species in the categories LC, LR/LC, LR/CD and NT). Species classified as DD (n = 7699) were set aside and not used for training or testing the classifier. All assessments identified by the IUCN as in need of an update were removed16, with one exception: if fewer than five records remained for a given taxonomic class, outdated assessment were kept to maximize the amount of training data. We used a data split for model validation16,39,86,87. Therefore, the remaining dataset (n = 28,363 species) was split into training (75%) and testing (25%) data. During the data split the balance of threat categories were maintained within both taxonomic families and environmental domains, i.e., marine and non-marine.

We used different partitions of the dataset to train ML classifiers in two ways: (1) all species together, and (2) separate classifiers for marine and non-marine species to account for the different spatial extents of the predictor data. For each data partition, we utilized a set of machine learning methods suitable for classification problems, each with its own strengths and weaknesses88. The best performing data partition (i.e., partition 1; for all species) was selected based on the highest average AUC (see section Model evaluation) across all taxonomic groups. Although irrelevant covariates tend to be automatically ignored in the utilized algorithms89–92, a smaller set of covariates can improve performance and increase interpretability of the model. Therefore, we performed feature selection on the training data of each partition by using the Boruta algorithm93. This algorithm compares the original feature importance to the importance of random shadow features while accounting for possible correlations and interactions. All features considered relevant at the 99% confidence level after 50 runs of the algorithm were kept (i.e., 270 features in partition 1). NA-values were imputed with random values using the package Hmisc94 in R, i.e., about 5% of the values in the remaining features. Optimal model settings and parameters were selected using the AutoML function in H2O.ai89,90. We used 10-fold cross validation for calibrating all models (e.g., tuning hyperparameters). In addition, the two classes (i.e., threatened versus not threatened species) were balanced during cross validation by oversampling of the smaller class (i.e., threatened species). In partition 1, a total of 220 models (i.e., base-learners) was trained, including generalized linear models, random forests, gradient boosted classification trees, deep neural networks and an extremely randomized forest (details in reference90). Ultimately, a so-called super-learner95 was generated using a non-negative generalized linear model with regularization (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) to produce more sparse ensembles90, combining the best features of the trained base-learners into one superior model. In total, 23 base-learners contributed to the predictions of the super-learner (Supplementary Table 3).

Model evaluation

The performance of all base-learners and the super-learner of the best performing data partition (i.e., partition 1; trained using all species) was assessed using the set aside testing data (n = 6857 species). In addition, we assessed model performance using DD species that have been re-evaluated and assigned a threat category in Red List Version 2021-2 (n = 123 species)15.

We calculated accuracy as the fraction of correctly classified species across the total number of species (Eq. 1), specificity as the fraction of not threatened species being correctly classified as not threatened (Eq. 2), sensitivity (i.e., recall) as the fraction of threatened species being correctly classified as threatened (Eq. 3), the false positive rate as fraction of not threatened species being classified as threatened (Eq. 4), the negative predictive value as the fraction of not threatened species across species predicted to be not threatened (Eq. 5), the positive predictive value (i.e., precision) as the fraction of threatened species across species predicted to be threatened (Eq. 6) and, balanced accuracy as the average of specificity and sensitivity.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

In addition, AUC, AUCPR and GINI coefficient were calculated89,90 as threshold-independent performance measures for binary classifiers. A value of 1 depicts the highest performance for all metrics. AUC is the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for sensitivity (Eq. 3) versus false positive rate (Eq. 4). This measure is influenced by correctly assigned species as being not threatened (True Negatives), which is the dominating class in our dataset. In contrast, AUCPR, as the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for precision (Eq. 6) versus recall (Eq. 3), is not affected by true negatives (i.e., correctly predicted not-threatened species) but instead affected by how precise the classifier is in predicting which species are threatened. The GINI coefficient describes the degree of separation between both classes (i.e., threatened versus not threatened), with a value of 1 indicating perfect separation.

Permutation variable importance was calculated as the performance loss (i.e., in AUC) on the testing data before and after a feature was permuted. Features were permuted one at a time in a total of 50 repetitions. In partition 1, the species’ taxonomic affiliation, proxies for geographic range size (i.e., number of native countries, species range extent and number of occurrence cells), anthropogenic activities within the species’ range (number of dams, road density, number of powerplants, human footprint index), and occupied environmental domains (combinations of terrestrial, freshwater and marine) are most important for the super-learner in accurately separating not threatened and threatened species (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Statistics and reproducibility

Analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.396 in RStudio version 1.4.110397. Data were obtained from GBIF, OBIS and IUCN using the packages rgbif, robis, and rredlist52,55,56. Handling of spatial and other data was conducted using the R packages caTools, doParallel, exactextractr, fasterize, maptools, parallel, raster, readxl, rgdal, rgeos, sf, sp, stringr, tidyverse, and xlsx96,98–110, and in python using the arcpy module from ArcGIS Pro version 2.9.0111. Machine learning algorithms were trained and evaluated using the H2O.ai interface (Version 3.36.0.4) for R89 and caret112. Figures were created using ggplot113, ggridges114, rnaturalearth115, viridis116 and base R96.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the Digital Transformation initiative of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The contribution of M.H., M.D. and F.V. has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 850717). We further thank Daniel Moran and Caitlin Mandeville for valuable feedback during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

J.B. and M.D. designed the study and gathered predictor data. J.B. performed data analyses, model building and evaluation. J.B., M.D., M.H., and F.V. interpreted the results and wrote the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Barnaby Walker and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Caitlin Karniski and Luke R. Grinham.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Data availability

Previously published and open-access source data were retrieved from refs. 45,46,53,54,58–73,79–84. All data generated in this study is available without restrictions. The generated predictions for the testing data, complete dataset and updated Data Deficient species are provided as supplementary files (Supplementary Data 1–3). Any further requests can be directed to the corresponding author.

Code availability

All code generated in this study is available without restrictions. R code for preparing the data, for training and testing the ML classifier, as well as applying the algorithm is available on GitHub (https://github.com/jannebor/dd_forecast)117. Although functionality may be given in other version, the code in this study was used in R version 4.0.396 in RStudio version 1.4.110397. The classifier can be applied for single species using our web application (https://ml-extinctionrisk.indecol.no/). Any further requests can be directed to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/23/2022

In this article the statement in the Funding information section was incorrectly given as ‘NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)’. and should have read ‘Open access funding provided by Norwegian University of Science and Technology’. The original article has been corrected.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-03638-9.

References

- 1.Cardillo M, Meijaard E. Are comparative studies of extinction risk useful for conservation? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012;27:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mace GM, Norris K, Fitter AH. Biodiversity and ecosystem services: a multilayered relationship. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffen W, Broadgate W, Deutsch L, Gaffney O, Ludwig C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015;2:81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Díaz S, et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Sci. (80-.). 2019;366:eaax3100. doi: 10.1126/science.aax3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newbold T, et al. Has land use pushed terrestrial biodiversity beyond the planetary boundary? A global assessment. Sci. (80-.) 2016;353:288–291. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimm SL, et al. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Sci. (80-.). 2014;344:1246752–1246752. doi: 10.1126/science.1246752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IPBES. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Zenodo (2019) 10.5281/zenodo.3831674.

- 8.Barnosky AD, et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature. 2011;471:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nature09678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigues A, Pilgrim J, Lamoreux J, Hoffmann M, Brooks T. The value of the IUCN Red List for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006;21:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mace GM, et al. Quantification of extinction risk: IUCN’s system for classifying threatened species. Conserv. Biol. 2008;22:1424–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S, Simpson AGB, Worm B. How many species are there on Earth and in the Ocean? PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purvis A, Hector A. Getting the measure of biodiversity. Nature. 2000;405:212–219. doi: 10.1038/35012221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachman SP, et al. Progress, challenges and opportunities for Red Listing. Biol. Conserv. 2019;234:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rondinini C, Di Marco M, Visconti P, Butchart SHM, Boitani L. Update or outdate: long-term viability of the IUCN red list. Conserv. Lett. 2014;7:126–130. doi: 10.1111/conl.12040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021-2. https://www.iucnredlist.org (2021).

- 16.Cazalis V, et al. Bridging the research-implementation gap in IUCN Red List assessments. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022;37:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee. Guidelines for using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Committee. Downloadable fromhttps://www.iucnredlist.org/documents/RedListGuidelines.pdf vol. 15 (2022).

- 18.Bland LM, et al. Toward reassessing data‐deficient species. Conserv. Biol. 2017;31:531–539. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butchart SHM, Bird JP. Data Deficient birds on the IUCN Red List: What don’t we know and why does it matter? Biol. Conserv. 2010;143:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao L, et al. Spatial knowledge deficiencies drive taxonomic and geographic selectivity in data deficiency. Biol. Conserv. 2019;231:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons ECM. Why IUCN should replace “Data Deficient” conservation status with a precautionary “Assume Threatened” Status—A Cetacean Case Study. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016;3:2015–2017. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts DL, Taylor L, Joppa LN. Threatened or Data Deficient: assessing the conservation status of poorly known species. Divers. Distrib. 2016;22:558–565. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jetz W, Freckleton RP. Towards a general framework for predicting threat status of data-deficient species from phylogenetic, spatial and environmental information. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015;370:20140016. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard SD, Bickford DP. Amphibians over the edge: silent extinction risk of Data Deficient species. Divers. Distrib. 2014;20:837–846. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarić I, Courchamp F, Gessner J, Roberts DL. Potentially threatened: a Data Deficient flag for conservation management. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016;25:1995–2000. doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1164-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mair L, et al. A metric for spatially explicit contributions to science-based species targets. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021;5:836–844. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butchart SHM, et al. Measuring Global Trends in the status of biodiversity: red list indices for birds. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations. Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1 (2015).

- 29.Butchart SHM, et al. Using Red List Indices to measure progress towards the 2010 target and beyond. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005;360:255–268. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenzen M, et al. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature. 2012;486:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran D, Kanemoto K. Identifying species threat hotspots from global supply chains. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017;1:0023. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mooers AØ, Faith DP, Maddison WP. Converting endangered species categories to probabilities of extinction for Phylogenetic Conservation Prioritization. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Runting RK, Phinn S, Xie Z, Venter O, Watson JEM. Opportunities for big data in conservation and sustainability. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2003. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15870-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochkirch A, et al. A strategy for the next decade to address data deficiency in neglected biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 2021;35:502–509. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hino M, Benami E, Brooks N. Machine learning for environmental monitoring. Nat. Sustain. 2018;1:583–588. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0142-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wearn OR, Freeman R, Jacoby DMP. Responsible AI for conservation. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019;1:72–73. doi: 10.1038/s42256-019-0022-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bland LM, et al. Cost-effective assessment of extinction risk with limited information. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015;52:861–870. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bland LM, Böhm M. Overcoming data deficiency in reptiles. Biol. Conserv. 2016;204:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bland LM, Collen B, Orme CDL, Bielby J. Predicting the conservation status of data-deficient species. Conserv. Biol. 2015;29:250–259. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luiz OJ, Woods RM, Madin EMP, Madin JS. Predicting IUCN extinction risk categories for the World’s Data Deficient Groupers (Teleostei: Epinephelidae) Conserv. Lett. 2016;9:342–350. doi: 10.1111/conl.12230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stévart T, et al. A third of the tropical African flora is potentially threatened with extinction. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaax9444. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax9444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darrah SE, Bland LM, Bachman SP, Clubbe CP, Trias-Blasi A. Using coarse-scale species distribution data to predict extinction risk in plants. Divers. Distrib. 2017;23:435–447. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walls RHL, Dulvy NK. Tracking the rising extinction risk of sharks and rays in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:15397. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94632-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walls RHL, Dulvy NK. Eliminating the dark matter of data deficiency by predicting the conservation status of Northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea sharks and rays. Biol. Conserv. 2020;246:108459. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.IUCN. Species Information Service. Version 2020-3. https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/spatial-data-download (2021).

- 46.IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-3. https://www.iucnredlist.org (2020).

- 47.Böhm M, et al. The conservation status of the world’s reptiles. Biol. Conserv. 2013;157:372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dulvy NK, et al. Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. Elife. 2014;3:1–34. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selig ER, et al. Global priorities for Marine biodiversity conservation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e82898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Hara CC, Afflerbach JC, Scarborough C, Kaschner K, Halpern BS. Aligning marine species range data to better serve science and conservation. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mittermeier, R. A., Goetsch Mittermeier, C., Gil, P. R. & Wilson, E. O. Megadiversity: Earth’s Biologically Wealthiest Nations. CEMEX (2005).

- 52.Chamberlain, S. rredlist: ‘IUCN’ Red List Client. R package version 0.7.0. (2020).

- 53.GBIF. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility: What is GBIF?https://www.gbif.org/what-is-gbif (2021).

- 54.OBIS. Ocean Biodiversity Information System. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO. www.obis.org. (2021).

- 55.Chamberlain, S. et al. rgbif: Interface to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility API. R package version 3.6.0. https://cran.r-project.org/package=rgbif (2021).

- 56.Provoost, P. & Bosch, S. robis: Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) Client. R package version 2.3.9. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=robis. (2020).

- 57.Pereira HM, Navarro LM, Martins IS. Global biodiversity change: the bad, the good, and the unknown. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012;37:25–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-042911-093511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karger DN, et al. Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Sci. Data. 2017;4:170122. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karger, D. N. et al. Data from: Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Dryad, Dataset10.5061/dryad.kd1d4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.ESA. Land Cover CCI Product User Guide Version 2. Tech. Rep. http://maps.elie.ucl.ac.be/CCI/viewer/download.php (2017).

- 61.Venter O, et al. Global terrestrial Human Footprint maps for 1993 and 2009. Sci. Data. 2016;3:160067. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennedy CM, Oakleaf JR, Theobald DM, Baruch‐Mordo S, Kiesecker J. Managing the middle: a shift in conservation priorities based on the global human modification gradient. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019;25:811–826. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seto KC, Guneralp B, Hutyra LR. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2012;109:16083–16088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211658109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.UNEP-WCMC & IUCN. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA). Cambridge, UK:UNEP-WCMC and IUCNwww.protectedplanet.net (2021).

- 65.Hansen MC, et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Sci. (80-.) 2013;342:850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1244693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tuanmu MN, Jetz W. A global, remote sensing-based characterization of terrestrial habitat heterogeneity for biodiversity and ecosystem modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015;24:1329–1339. doi: 10.1111/geb.12365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maggi F, Tang FHM, la Cecilia D, McBratney A. PEST-CHEMGRIDS, global gridded maps of the top 20 crop-specific pesticide application rates from 2015 to 2025. Sci. Data. 2019;6:170. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0169-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Byers, L. et al. A Global Database of Power Plants. World Resour. Inst. 1–18 (2019).

- 69.Mulligan M, van Soesbergen A, Sáenz L. GOODD, a global dataset of more than 38,000 georeferenced dams. Sci. Data. 2020;7:31. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boulay A-M, et al. The WULCA consensus characterization model for water scarcity footprints: assessing impacts of water consumption based on available water remaining (AWARE) Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018;23:368–378. doi: 10.1007/s11367-017-1333-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barbarossa V, et al. Erratum: FLO1K, global maps of mean, maximum and minimum annual streamflow at 1 km resolution from 1960 through 2015. Sci. Data. 2018;5:180078. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barbarossa V, et al. Impacts of current and future large dams on the geographic range connectivity of freshwater fish worldwide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2020;117:3648–3655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912776117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Domisch S, Amatulli G, Jetz W. Near-global freshwater-specific environmental variables for biodiversity analyses in 1 km resolution. Sci. Data. 2015;2:150073. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2015.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reid AJ, et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2019;94:849–873. doi: 10.1111/brv.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dudgeon D, et al. Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 2006;81:163. doi: 10.1017/S1464793105006950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schlossberg S, Chase MJ, Gobush KS, Wasser SK, Lindsay K. State-space models reveal a continuing elephant poaching problem in most of Africa. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:10166. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66906-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burn RW, Underwood FM, Blanc J. Global trends and factors associated with the illegal killing of Elephants: a hierarchical Bayesian Analysis of Carcass Encounter Data. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hauenstein S, Kshatriya M, Blanc J, Dormann CF, Beale CM. African elephant poaching rates correlate with local poverty, national corruption and global ivory price. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2242. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09993-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.UNDP. Human Development Report 2020. The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene. New York. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2020. (2020).

- 80.Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index2020. (2020).

- 81.Early R, et al. Global threats from invasive alien species in the twenty-first century and national response capacities. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12485. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Halpern BS, et al. Spatial and temporal changes in cumulative human impacts on the world’s ocean. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7615. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Halpern BS, et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Sci. (80-.) 2008;319:948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1149345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Assis J, et al. Bio‐ORACLE v2.0: extending marine data layers for bioclimatic modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018;27:277–284. doi: 10.1111/geb.12693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tyberghein L, et al. Bio-ORACLE: a global environmental dataset for marine species distribution modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012;21:272–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00656.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zizka A, Silvestro D, Vitt P, Knight TM. Automated conservation assessment of the orchid family with deep learning. Conserv. Biol. 2021;35:897–908. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hastie, T., Friedman, J. & Tibshirani, R. The Elements of Statistical Learning. The Elements of Statistical Learning vol. 27 (Springer New York, 2001).

- 88.Kampichler C, Wieland R, Calmé S, Weissenberger H, Arriaga-Weiss S. Classification in conservation biology: a comparison of five machine-learning methods. Ecol. Inform. 2010;5:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2010.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.LeDell, E. et al. h2o: R Interface for the ‘H2O’ Scalable Machine Learning Platform. R package version 3.36.0.4. https://github.com/h2oai/h2o-3 (2022).

- 90.H2O.ai. H2O AutoML. https://docs.h2o.ai/h2o/latest-stable/h2o-docs/automl.html (2022).

- 91.Cutler DR, et al. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology. 2007;88:2783–2792. doi: 10.1890/07-0539.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuhn M. Building Predictive Models in R using the caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008;28:1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v028.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kursa MB, Rudnicki WR. Feature selection with the Boruta package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010;36:1–13. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harrell Jr, F. E. Hmisc: Harrell miscellaneous. R package version 4.5-0. (2021).

- 95.van der Laan, M. J., Polley, E. C. & Hubbard, A. E. Super Learner. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 6 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austriahttps://www.r-project.org/ (2021).

- 97.RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MAhttp://www.rstudio.com/ (2021).

- 98.Hijmans, R. J. raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. R package version 3.0-7. https://cran.r-project.org/package=raster (2019).

- 99.Bivand, R., Keitt, T. & Rowlingson, B. rgdal: Bindings for the ‘Geospatial’Data Abstraction Library. https://cran.r-project.org/package=rgdal (2019).

- 100.Bivand, R. & Lewin-Koh, N. maptools: Tools for Handling Spatial Objects. R package version 0.9-5. https://cran.r-project.org/package=maptools/ (2019).

- 101.Bivand, R. & Rundel, C. rgeos: Interface to Geometry Engine - Open Source (‘GEOS’). R package version 0.5-1. https://cran.r-project.org/package=rgeos (2019).

- 102.Bivand, R. S., Pebesma, E. & Gómez-Rubio, V. Applied Spatial Data Analysis with R. (Springer New York, 2013).

- 103.Pebesma E. Simple features for R: standardized support for Spatial Vector Data. R. J. 2018;10:439. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2018-009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ross, N. Fasterize: Fast Polygon to Raster Conversion. R package version 1.0.3.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=fasterize (2020).

- 105.Microsoft Corporation & Weston, S. doParallel: Foreach Parallel Adaptor for the ‘parallel’ Package. R package version 1.0.16.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=doParallel (2020).

- 106.Wickham, H. stringr: simple, consistent wrappers for common string operations. R package version 1.4.0.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stringr (2019).

- 107.Tuszynski, J. caTools: tools: Moving Window Statistics, GIF, Base64, ROC AUC, etc. R package version 1.18.1.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caTools (2021).

- 108.Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4, 1686.10.21105/joss.01686 (2019).

- 109.Dragulescu, A. & Arendt, C. xlsx: Read, Write, Format Excel 2007 and Excel 97/2000/XP/2003 Files. R package version 0.6.5. (2020).

- 110.Wickham, H. & Bryan, J. readxl: Read Excel Files. R package version 1.3.1.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readxl (2019).

- 111.ESRI. ArcGIS Pro version 2.9.0. https://www.esri.com/en-us/home (2022).

- 112.Kuhn, M. caret: Classification and Regression Training. R package version 6.0-86. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret (2020).

- 113.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer, NY (2016).

- 114.Wilke, C. O. ggridges: Ridgeline Plots in ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.5.3.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggridges (2021).

- 115.South, A. rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth. R package version 0.1.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rnaturalearth (2017).

- 116.Garnier, S. viridis: Default Color Maps from ‘matplotlib’. R package version 0.5.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=viridis (2018).

- 117.Borgelt, J. jannebor/dd_forecast: Code for study ‘More than half of Data Deficient species predicted to be threatened by extinction’ (v1.0.1). 10.5281/zenodo.6627688.Zenodo (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Previously published and open-access source data were retrieved from refs. 45,46,53,54,58–73,79–84. All data generated in this study is available without restrictions. The generated predictions for the testing data, complete dataset and updated Data Deficient species are provided as supplementary files (Supplementary Data 1–3). Any further requests can be directed to the corresponding author.

All code generated in this study is available without restrictions. R code for preparing the data, for training and testing the ML classifier, as well as applying the algorithm is available on GitHub (https://github.com/jannebor/dd_forecast)117. Although functionality may be given in other version, the code in this study was used in R version 4.0.396 in RStudio version 1.4.110397. The classifier can be applied for single species using our web application (https://ml-extinctionrisk.indecol.no/). Any further requests can be directed to the corresponding author.