Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate adherence to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for abstracts in reports of randomised trials on child and adolescent depression prevention. Secondary objective was to examine factors associated with overall reporting quality.

Design

Meta-epidemiological study.

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycArticles and CENTRAL.

Eligibility criteria

Trials were eligible if the sample consisted of children and adolescents under 18 years with or without an increased risk for depression or subthreshold depression. We included reports published from 1 January 2003 to 8 August 2020 on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster randomised trials (CRTs) assessing universal, selective and indicated interventions aiming to prevent the onset of depression or reducing depressive symptoms.

Data extraction and synthesis

As the primary outcome measure, we assessed for each trial abstract whether information recommended by CONSORT was adequately reported, inadequately reported or not reported. Moreover, we calculated a summative score of overall reporting quality and analysed associations with trial and journal characteristics.

Results

We identified 169 eligible studies, 103 (61%) RCTs and 66 (39%) CRTs. Adequate reporting varied considerably across CONSORT items: while 9 out of 10 abstracts adequately reported the study objective, no abstract adequately provided information on blinding. Important adverse events or side effects were only adequately reported in one out of 169 abstracts. Summative scores for the abstracts’ overall reporting quality ranged from 17% to 83%, with a median of 40%. Scores were associated with the number of authors, abstract word count, journal impact factor, year of publication and abstract structure.

Conclusions

Reporting quality for abstracts of trials on child and adolescent depression prevention is suboptimal. To help health professionals make informed judgements, efforts for improving adherence to reporting guidelines for abstracts are needed.

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, MENTAL HEALTH, PAEDIATRICS, Child & adolescent psychiatry, Depression & mood disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to systematically assess the reporting quality for abstracts of randomised trials on paediatric depression prevention.

Our extensive, reproducible search strategy identified 169 eligible journal articles reflecting the available evidence from such trials published in 2003–2020.

Two reviewers independently screened abstracts and extracted data using standardised methods, but the reviewers were not blinded to meta-data such as study authors, journal name or year of publication.

Since no method has so far been established for determining overall reporting quality of abstracts, we approximated overall reporting quality by calculating a summative score based on Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials items.

Because we applied a topic-based approach without restricting the information source to specific journals, our study findings offer insights into general reporting quality in trials on childhood depression prevention.

Introduction

Reports of trials should provide all necessary information allowing readers to evaluate the reproducibility, validity and utility of studies and findings.1 2 Poor reporting of health research leads, at the very least, to avoidable waste of resources3 and can ultimately jeopardise patient care.4 The same applies to abstracts of trials. Due to time, access and language constraints, health professionals often use abstracts as the primary source of information to learn about a trial,5 6 and the way abstracts report study details can influence their decisions in patient management.7 Researchers conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses may incorrectly exclude eligible studies in title and abstract screening due to poor reporting which can distort evidence synthesis.8 Moreover, indexers of literature databases rely on adequate title and abstract reporting to correctly determine search terms such as medical subject headings, otherwise relevant journal articles cannot be found, read and quoted to affect medical practice.

For these reasons, authors of randomised trial reports are encouraged to follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines5–8 and its extension for abstracts (CONSORT-A).9 10 CONSORT-A was published in 2008 to provide guidance to authors on information to be reported in abstracts of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In 2012, the guidelines were further complemented by a module for cluster randomised trial (CRT) abstracts (CONSORT-C).11 Although some improvement in reporting quality of trials has been observed over recent years,12 general adherence to CONSORT guidelines remains suboptimal in articles published both in general medicine13–17 and psychiatry/psychology journals.18–20 Similar results have been reported from studies on adherence to CONSORT-A for abstract reporting in various health disciplines including one previous study on abstracts of psychiatric RCTs.21 However, no prior study has investigated the abstract reporting quality of depression prevention trials in young people. We, therefore, aimed to evaluate to what extend CONSORT-A and CONSORT-C criteria are met by abstracts of reports on child and adolescent depression prevention trials. Secondary objective of our study was to explore trial and journal characteristics associated with the abstracts’ overall reporting quality.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included reports on RCTs and CRTs assessing universal, selective and indicated interventions aiming to prevent the onset of depression or reducing depressive symptoms in children and adolescents under 18 years with or without an increased risk for depression or subthreshold depression. A detailed list of the eligibility criteria is provided in online supplemental file S1. We only included research articles published in peer-reviewed journals, the primary source of information for paediatric health specialists,22 and we considered the period between 1 January 2003 and 5 August 2020 to assess reporting quality before and after the publication of CONSORT-A and CONSORT-C guidelines.

bmjopen-2022-061873supp001.pdf (260.3KB, pdf)

Information sources

We searched the electronic literature databases MEDLINE (via PubMed and Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via EBSCOhost), PsycArticles (via EBSCOhost) and CENTRAL (via Cochrane Library) on 9 March 2019 and updated the search on 8 August 2020. Search strings were developed in collaboration with a trained librarian. The electronic search strategy for MEDLINE via PubMed is shown in online supplemental file S2. Electronic search strategies for the other databases are provided in an online repository.23 Additional articles were retrieved by handsearching four specialty journals and the reference lists of systematic reviews (online supplemental file S3).

Study selection and data collection

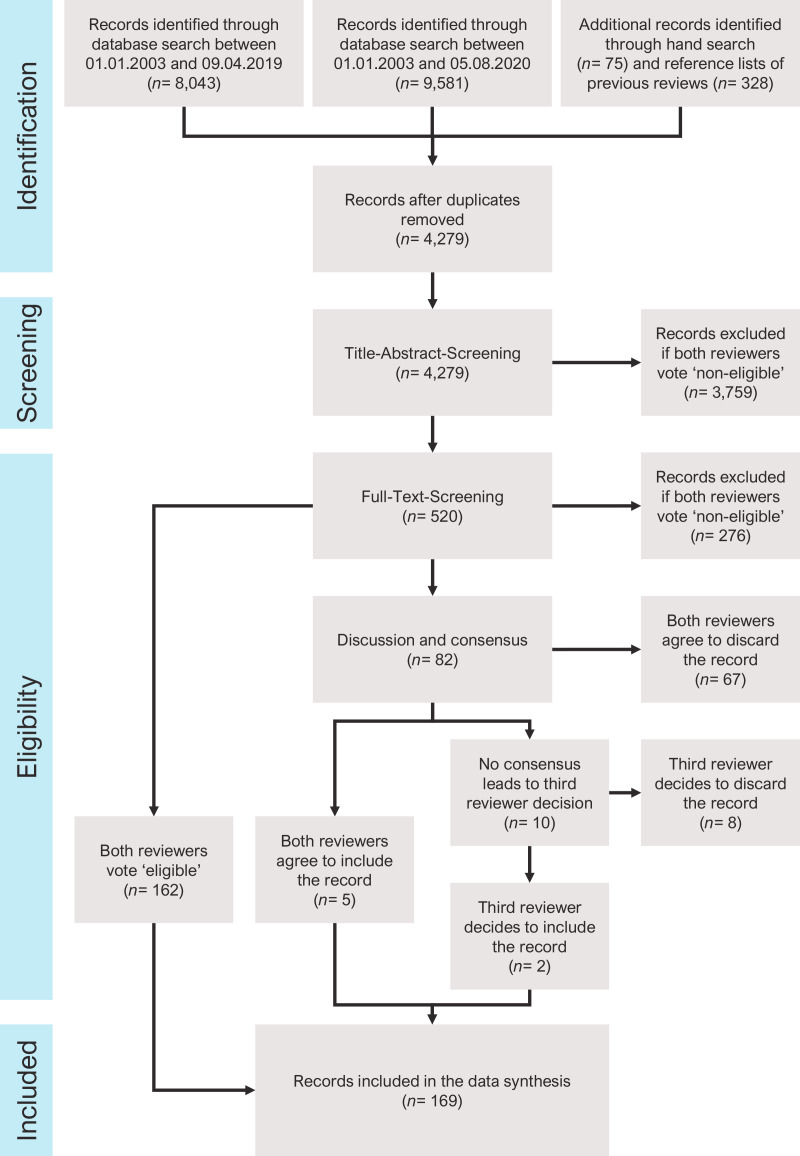

The study selection process consisted of a title and abstract screening, a full-text screening and a discussion and consensus phase (figure 1). Two independent reviewers extracted information from articles into piloted spreadsheets with drop-down menus. The reviewers first determined whether randomisation was performed on an individual (RCT) or cluster level (CRT) and subsequently assessed all abstracts according to CONSORT-A and CRTs additionally according to CONSORT-C.10 11 For each item, the reviewers judged whether the abstract reported information adequately, inadequately or not at all.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart depicting the study selection process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. (Source: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n160)

For items with multiple dimensions, we operationalised each dimension separately and then created item variables for analysis based on the extracted information. For example, CONSORT-A item 03 Participants requires reporting the eligibility criteria for participants and settings where the data were collected. Thus, if both dimensions were reported adequately (or not at all), then the item was judged as adequately reported (or as not reported). However, if either the eligibility criteria for participants or for settings was reported inadequately, the item was judged as inadequately reported.

Based on earlier studies, we prespecified seven study characteristics previously associated with overall reporting quality (online supplemental file S4). We operationalised these study characteristics using the variable definitions in online supplemental file S5.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarise the extent to which RCT and CRT abstracts adhered to the 15 CONSORT-A items and CRT abstracts adhered to the additional eight CONSORT-C items. For each CONSORT item, we thus present the proportion of trial abstracts adequately, inadequately or not reporting the item information as required by the appropriate guideline.

We calculated summative scores of overall reporting quality grading CONSORT items as follows: (1) adequately reported (two points), (2) inadequately reported (one point) and (3) not reported (0 points). Depending on the study design, these overall reporting quality scores (RQS) could thus theoretically range from 0 to 30 for RCTs (15 CONSORT-A items) and from 0 to 46 for CRTs (8 additional CONSORT-C items). We transformed RQS to standardised percentages with possible ranges from 0 (lowest reporting quality) to 100 (highest reporting quality). We compared unstructured (1 section), structured (2–4 sections) and highly structured (>4 sections) abstracts24 in relation to RQS using the Kruskal-Wallis test. We fitted separate linear regression models to quantify associations between overall reporting quality and (1) number of authors, (2) sample size, (3) number of sampling points, (4) abstract word count, (5) journal impact factor and (6) year of publication. Because of heavily skewed distributions (online supplemental file S6) we log-transformed (log 10) the first five above-mentioned variables for analysis. We used RStudio (R V.4.1.1) for data analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Instead of patient data we used information of previously published trial reports. Thus, no patients or public were involved in this study. Yet, our results can inform authors, editors, reviewers and readers of the scientific literature.

Results

Included abstracts

We screened the title and abstract of 4279 articles and the full text of 520 articles, and we ultimately included 169 articles in the data synthesis (figure 1). Inter-rater reliability as assessed by Cohen’s kappa (unweighted) for the agreement between the three reviewer pairs (article eligible vs non-eligible) was moderate in the title and abstract screening with κ=0.39, κ=0.47 and κ=0.55 and higher in the full text screening with κ=0.59, κ=0.73 and κ=0.67. For interrater reliability on CONSORT items, please refer to online supplemental file S7.

Of all 169 articles, 61% were reports on RCTs (n=103) and 39% reports on CRTs (n=66). More than half of these articles were published between 2015 and 2020 (online supplemental file S8). Median number of authors was five (range: 1–24, Q1: 4, Q3: 8). Sample size ranged from 23 to 12 391 participants, with a median of 271 (Q1: 120, Q3: 670). Twenty-one of the reported studies were performed at a single site, while 117 were reports of multicentre studies. Median abstract word count was 225 words, with range from 68 to 623 (Q1: 175, Q3: 253). The median journal impact factor was 3.2 (Q1: 2.1, Q3: 4.3). Fifty-seven per cent of the included abstracts were unstructured (n=97), one-third of the abstracts were structured with two to four sections (n=56), and the remaining 10% were highly structured (n=16), that is, with more than four sections.

Adherence to CONSORT for abstracts

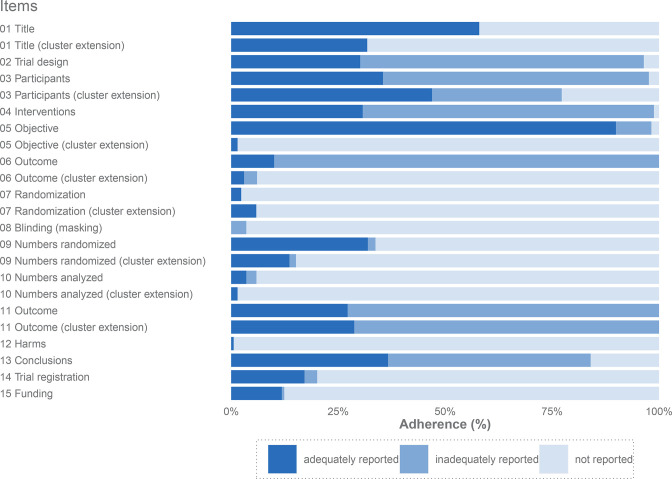

Figure 2 summarises the results on adherence to CONSORT for abstracts items, that is, the proportion of trial abstracts reporting item information adequately, inadequately and not at all (please see also online supplemental file S7 for exact figures). The percentage of adequate reporting among general items ranged from 58.0% (item 01 Title) to 30.2% (item 02 Trial design). With regard to trial methodology, the highest percentage of adequate reporting was in item 05 Objective and the lowest in item 08 Blinding. Regarding trial results, item 13 Conclusions had the highest percentage of adequate reporting (36.7%) and item 12 Harms the lowest (0.6%).

Figure 2.

Percentage of abstracts adhering to CONSORT items in 169 trial reports on the prevention of depression in children and adolescents. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Overall reporting quality and associated factors

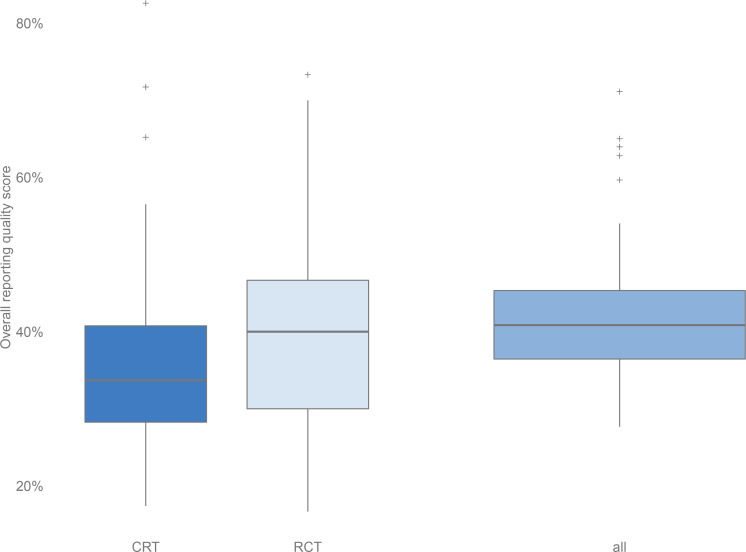

The distribution of the RQS among all abstracts and stratified by study design is depicted in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of overall reporting quality by study design. CRT, cluster randomised trial; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

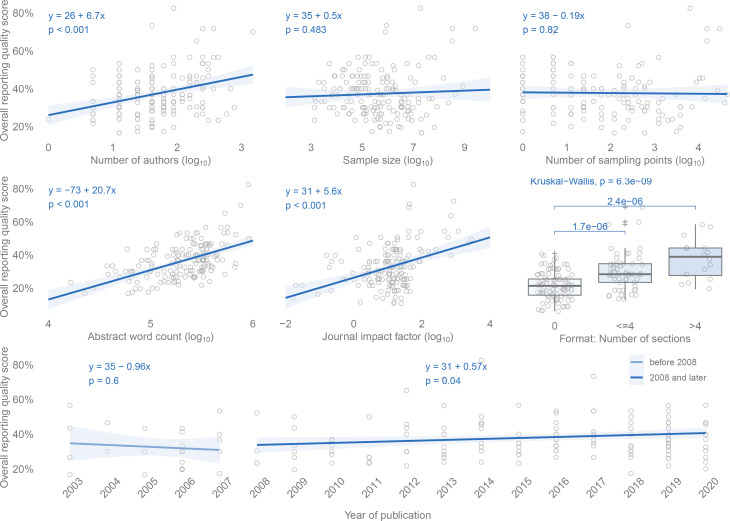

The graphs in figure 4 visualise the relationship of trial and journal characteristics with RQS. Number of authors, abstract word count and journal impact factor were positively associated with RQS. For example, for every 10% increase in the journal impact factor, the RQS increased by about 1.9 percentage points (calculation: coefficient 5.6×log(1.10) ≈ 1.9). Structured (2–4 sections) and in particular highly structured abstracts (>4 sections) had a higher RQS than unstructured abstracts (1 section). Sample size and number of sampling points were not related to RQS. Finally, after publication of CONSORT-A in 2008, RQS annually increased by 0.57 units.

Figure 4.

Associations of overall reporting quality with abstract and journal characteristics.

An additional before-and-after comparison illustrates that the RQS was higher in the period from 2008 to 2020 (median: 36.7, Q1: 30.0, Q3: 43.5) than in the period from 2003 to 2007 (median: 32.0, Q1: 22.9, Q3: 41.8).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed reporting quality for abstracts of child and adolescent depression prevention trial reports. Overall, we found that adherence with CONSORT-A and CONSORT-C for abstracts is suboptimal in journal articles reporting on such studies between 2003 and 2020.

Comparison with previous studies

Meta-epidemiological studies of reporting quality follow two distinct methodological approaches. In the journal-based approach, one or more journals are selected, usually top journals in a specific field with a high-impact factor and the published articles are assessed. Examples comprise studies on the abstract reporting quality in general15 16 25–27 and internal medicine,28–30 anaesthesiology,31–33 surgery,34 35 nursing36 and critical care.37 The only prior study on abstracts of psychiatric trials followed this approach as well.21 However, the restriction to top journals could affect generalisability, as a higher impact factor may be associated with better reporting quality.21 28 36 38–42 Thus, journal-based meta-epidemiological studies might overestimate the quality of abstract reporting. On the contrary, in the topic-based approach, no constraints are made regarding the journals. Instead, literature databases are systematically searched for articles on a specific disease, therapy or other topic.38 39 42–48 This increases the variety of journals, making it difficult to draw conclusions about reporting quality of specific journals. However, the topic-based approach increases generalisability by also including journals with a lower impact factor and thus provide a more complete picture of reporting quality.

General items

In our study, the general items 01 Title and 02 Trial design were adequately reported in about 60% and 30% of trial abstracts, respectively. Similarly, Song et al reported in their study that 66% of trials stated ‘randomised’ in the title but only 14% of trials described the study design in the abstract.21

CONSORT-C requires that abstracts are denoted as cluster randomised in the title (item 01 Title (cluster extension)). In our study, however, only one-third of all CRT abstracts adequately reported this item. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine adherence to CONSORT-C guidelines in CRT abstracts. Yet, some meta-epidemiological studies examined adherence to CONSORT-C for full texts, which includes the same item. For example, Chan et al showed that about two-thirds of pilot or feasibility CRT reports published between 2011 and 2014 adequately met this CONSORT item.49 Similarly, Ivers et al, Diaz-Ordaz et al, and Walleser et al found that 48%, 60% and 98% of CRTs, respectively, state in the title or abstract that the study is a CRT.50–52

Trial methodology

Among all 169 included abstracts, 36% adequately reported both eligibility criteria for participants and setting. In line with many previous studies,16 21 28 33 37 53 we extracted the originally combined information for CONSORT item 03 Participants using separate dimensions: (1) eligibility criteria for participants and (2) eligibility criteria for settings. In contrast, other studies assessed reporting of eligibility criteria for participants only.26 43 54 55 It is not surprising that these studies show the higher proportions of adequate reporting for this item.

We found that 98% of abstracts failed to adequately include information on how participants were assigned to interventions and that 96% of abstracts lacked complete information on whether participants, programme deliverer and data collectors/analysts were blinded. With a few exceptions,16 36 42–44 48 most previous studies reported adherence to these items of well below 10%.15 21 25 26 28–35 37–41 45 46 55–60

Trial results

The number of participants randomised to each group was adequately reported in approximately one-third of all abstracts and only 4% of the included trial abstracts adequately reported the number of participants analysed in each group. This gap between item 09 Numbers randomised and item 10 Numbers analysed has also been observed in previous studies.57

Only one article in our sample elaborated on adverse or unintended effects in the abstract, whereas all other 168 abstracts failed to mention important adverse events or side effects (item 12 Harms). Other meta-epidemiological studies found considerably higher proportions of adequate reporting for this item, particularly trials that also included pharmacological interventions.26 34 44

Finally, our study showed that about 12% of abstracts adequately reported the item 15 Funding. Many meta-epidemiological studies even found the proportion of abstracts that adequately report funding is in the single digits21 30 33 37 40 46 59 61 or even zero per cent.29 31 32 34 35 38 41 45 55–57 60 However, it may be rather the journal regulations than CONSORT to influence whether funding information appears in the abstract or in another place, for example, at the end of the manuscript.

Associations with overall reporting quality

In line with previous findings,28 39–41 46 59 we observed that overall reporting quality increases with the number of authors. In contrast, some studies found no such relationship.21 36 46 56–58 Other studies suggest, although not consistently,62 that the involvement of methodologists is associated with higher reporting quality.51 63 64 However, number of authors may reflect at least to some extent whether author groups include methodologists.

Furthermore, overall reporting quality seems to be positively related with the abstract word count. This observation is consistent with the results of previous meta-epidemiological studies.39–43 46 48 56 61 It seems that the more words authors have at their disposal, the more information they can provide.

Our data suggest that a higher journal impact factor correlates with increased overall reporting quality. If the impact factor is an indicator for journal quality,65 journals with a higher impact factor may apply more rigorous quality control to reporting. This result would thus underline that restricting studies to top journals may hamper generalisability.

We observed that structured abstracts showed higher overall reporting quality compared with unstructured abstracts. With some exceptions,16 40 46 48 57 many meta-epidemiological studies have shown similar results both since21 28 36 39 41 42 56 61 and before the publication of CONSORT-A.66–72 However, a few studies also suggest that structured abstracts are not superior73–75 and that abstract structure was unrelated to reporting quality.76

In line with previous studies, we found that abstract reporting quality was higher in the period since the publication of CONSORT-A as compared with the period before.21 26 29 34 38 40 41 However, our data do not allow causal conclusions. Our data indicate that overall reporting quality is improving since 2008: in contrast to the period from 2003 to 2007, the RQS increased between 2008 and 2020. Chhapola et al observed a similar trend comparing the reporting quality of trial abstracts published in high-impact paediatric journals in 2003–2007 and 2010–2014.77

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first on reporting quality of trial abstracts in childhood depression prevention. Key strength of our study is the topic-based approach we have chosen; compared with journal-based studies, our results provide a more complete picture of abstract reporting in the field. We carried out an extensive, reproducible methodology to screen the literature for eligible studies and retrieve study information. We analysed abstracts published over a broad timespan allowing for comparison of reporting quality before and after publication of CONSORT guidelines. We assess adherence not only to CONSORT-A for RCT abstracts but also to CONSORT-C for CRT abstracts, which was not evaluated by any prior study.

We applied CONSORT to measure reporting quality, although it was not designed for this purpose. However, in the current absence of standardised tools for assessment, validated guidelines such as CONSORT are the best available choice to evaluate reporting quality. Moreover, CONSORT for social and psychological interventions were not checked for adherence.78 79 However, these guidelines were only published in 2017 and 2018, respectively, and thus a few studies could have considered these standards. We assess the reporting quality of trial abstracts and cannot draw conclusions about the quality of reporting in the main text. Reviewers were not blinded to trial and journal characteristics such as authors, publication date and impact factor, during the study selection and the data extraction. We can, therefore, not exclude the possibility of bias in the evaluation due to metadata insight of the judging reviewers.

When we calculated overall RQS, we treated each CONSORT item equally, although some items could be more or less relevant than others.30 37 43 These scores are simplified proxies to represent reporting quality with a single measure. The assessment of reporting quality should however primarily be based on the individual items.31

We did not assess associations between overall reporting quality and journal requirements, such as word count limits and format structure. However, the word count and structure of the included abstracts may largely reflect these journal requirements.

We used descriptive modelling to explore factors associated of reporting quality; neither predictive nor causal conclusions can be derived from this. Unmeasured factors such as journal endorsement of CONSORT80 may also be associated with reporting quality. Findings from our secondary research aim may thus be incomplete and should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Reporting quality plays a crucial role in generating and translating scientific evidence as it increases transparency and accuracy and thereby enables health professionals to identify, evaluate and replicate trial results. CONSORT extensions are valuable tools for authors, reviewers and editors to formulate trial abstracts in a transparent and comprehensible way. Although these tools have been openly available for years, the reporting quality of RCT and CRT abstracts on the prevention of depression in children and adolescents is suboptimal. According to our results, some CONSORT-A and CONSORT-C items are adequately reported in most depression prevention trial abstracts, and this should be the benchmark for all items. Interventions aimed at strengthening abstract reporting quality are thus needed.81 These efforts will very likely not only benefit the scientific community and practitioners in the field, but may ultimately improve mental healthcare for children and adolescents worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Jan Taubitz at the Medical Library, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, who with his expertise provided support for the research project in the development and evaluation of the literature search strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: JW is the guarantor. JW conceived the idea for the project. JW and CP developed the concept and methods. JW and JN performed the data selection and extraction. CP gave final instructions when consensus could not be reached. JW performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the study findings. JW drafted the first version of the manuscript. CP contributed to data interpretation, writing and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Funding: We acknowledge financial support from the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. https://osf.io/ahzwn/?view_only=e2f08c5c0d2d4936ba88d38968aba5d9.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, et al. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010;8:24. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SD, Furrow D, Hill DF, et al. A Duty to Describe. Perspect Psychol Sci 2014;9:626–40. 10.1177/1745691614551749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. The Lancet 2009;374:86–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman DG, Moher D, et al. Importance of Transparent Reporting of Health Research. In: Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, eds. Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: A User’s Manual: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996;276:637. 10.1001/jama.276.8.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. The Lancet 2001;357:1191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz KF, Altman DG, CONSORT MD. Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;2010:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D. Consort for reporting randomised trials in Journal and conference Abstracts. The Lancet 2008;371:281–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D. Consort for reporting randomized controlled trials in Journal and conference Abstracts: explanation and elaboration. JAMA 2008;5:e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345:e5661. 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Atal I, et al. Evolution of poor reporting and inadequate methods over time in 20 920 randomised controlled trials included in Cochrane reviews: research on research study. BMJ 2017;357:j2490. 10.1136/bmj.j2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG. Does use of the CONSORT statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane reviewa. Systematic Reviews 2012;1:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials. JAMA 1992;2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berwanger O, Ribeiro RA, Finkelsztejn A. The quality of reporting of trial Abstracts is suboptimal: survey of major general medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghimire S, Kyung E, Kang W. Assessment of adherence to the CONSORT statement for quality of reports on randomized controlled trial Abstracts from four high-impact general medical journals. Trials 2012;13:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samaan Z, Mbuagbaw L, Kosa S. A systematic scoping review of adherence to reporting guidelines in health care literature. JMDH 2013;169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stinson JN. Clinical trials in the Journal of pediatric psychology: applying the CONSORT statement. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2003;28:159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han C, Kwak K, Marks DM. The impact of the CONSORT statement on reporting of randomized clinical trials in psychiatry. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2009;30:116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant SP, Mayo-Wilson E, Melendez-Torres GJ. Reporting quality of social and psychological intervention trials: a systematic review of reporting guidelines and trial publications. PLoS One 2013;8:e65442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song SY, Kim B, Kim I. Assessing reporting quality of randomized controlled trial Abstracts in psychiatry: adherence to consort for Abstracts: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones TH, Hanney S, Buxton MJ. The information sources and journals consulted or read by UK paediatricians to inform their clinical practice and those which they consider important: a questionnaire survey. BMC Pediatr 2007:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiehn J, Nonte J, Prugger C. Reporting quality of randomised controlled and cluster randomised trial Abstracts in childhood depression prevention: a meta-epidemiologic study. Open Science Framework 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua F, Walsh T, Glenny A-M. Structure formats of randomised controlled trial Abstracts: a cross-sectional analysis of their current usage and association with methodology reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Li J, Ai C. Assessment of the quality of reporting in Abstracts of randomized controlled trials published in five leading Chinese medical journals. PLoS One 2010;5:e11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mbuagbaw L, Thabane M, Vanniyasingam T. Improvement in the quality of Abstracts in major clinical journals since consort extension for Abstracts: a systematic review. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2014;38:245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hays M, Andrews M, Wilson R. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trial Abstracts among high-impact general medical journals: a review and analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011082.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigna JJR, Noubiap JJN, Asangbeh SL. Abstracts reporting of HIV/AIDS randomized controlled trials in general medicine and infectious diseases journals: completeness to date and improvement in the quality since consort extension for Abstracts. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sriganesh K, Bharadwaj S, Wang M. Quality of Abstracts of randomized control trials in five top pain journals: a systematic survey. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 2017;7:64–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan MS, Shaikh A, Ochani RK. Assessing the quality of Abstracts in randomized controlled trials published in high impact cardiovascular journals. Circ: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2019;12:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chow JTY, Turkstra TP, Yim E. The degree of adherence to consort reporting guidelines for the Abstracts of randomised clinical trials published in anaesthesia journals: a cross-sectional study of reporting adherence in 2010 and 2016. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2018:942–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Can OS, Yilmaz AA, Hasdogan M. Has the quality of Abstracts for randomised controlled trials improved since the release of consolidated standards of reporting trial guideline for Abstract reporting? A survey of four high-profile anaesthesia journals. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011;28:485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janackovic K, Puljak L. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trial Abstracts in the seven highest-ranking anesthesiology journals. Trials 2018;19:591 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30373644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speich B, Mc Cord KA, Agarwal A. Reporting quality of Journal Abstracts for surgical randomized controlled trials before and after the implementation of the CONSORT extension for Abstracts. World J Surg 2019:2371–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallo L, Wakeham S, Dunn E. The reporting quality of randomized controlled trial Abstracts in plastic surgery. Aesthet Surg J 2020;40:335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, WS RN, Ying Y. Abstracts reporting of randomized controlled trials in ten Highest-ranking nursing journals: improvement in the quality since consort extension for Abstracts 2021.

- 37.Kuriyama A, Takahashi N, Nakayama T. Reporting of critical care trial Abstracts: a comparison before and after the announcement of consort guideline for Abstracts. Trials 2017;18:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui Q, Tian J, Song X. Does the CONSORT checklist for Abstracts improve the quality of reports of randomized controlled trials on clinical pathways? J Eval Clin Pract 2014;20:827–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang D, Chen L, Wang L. Abstracts for reports of randomized trials of COVID-19 interventions had low quality and high spin. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;139:107–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hua F, Deng L, Kau CH. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trial Abstracts. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2015;146:669–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Li Z, Liu B. Quality improvement in randomized controlled trial Abstracts in prosthodontics since the publication of consort guideline for Abstracts: a systematic review. J Dent 2018:23–9 (published Online First: 6 May 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo J-W, Iribarren SJ. Reporting quality for Abstracts of randomized controlled trials in cancer nursing research. Cancer Nurs 2014;37:436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baulig C, Krummenauer F, Geis B. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trial Abstracts on age-related macular degeneration health care: a cross-sectional quantification of the adherence to consort Abstract reporting recommendations. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivendran S, Newport K, Horst M. Reporting quality of Abstracts in phase III clinical trials of systemic therapy in metastatic solid malignancies. Trials 2015;16:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar S, Mohammad H, Vora H. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trials of periodontal diseases in Journal Abstracts-A cross-sectional survey and bibliometric analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2018;18:e22.:130–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang X, Hua F, Riley P. Abstracts of published randomized controlled trials in Endodontics: reporting quality and spin. Int Endod J 2020;53:1050–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaqman M, Al-Abedalla K, Wagner J. Reporting quality and spin in Abstracts of randomized clinical trials of periodontal therapy and cardiovascular disease outcomes. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knippschild S, Loddenkemper J, Tulka S. Assessment of reporting quality in randomised controlled clinical trial Abstracts of dental implantology published from 2014 to 2016. BMJ Open 2021;11:e045372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan CL, Leyrat C, Eldridge SM. Quality of reporting of pilot and feasibility cluster randomised trials: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ivers NM, Taljaard M, Dixon S, et al. Impact of CONSORT extension for cluster randomised trials on quality of reporting and study methodology: review of random sample of 300 trials, 2000-8. BMJ 2011;343:d5886. 10.1136/bmj.d5886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diaz-Ordaz K, Froud R, Sheehan B. A systematic review of cluster randomised trials in residential facilities for older people suggests how to improve quality. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walleser S, Hill SR, Bero LA. Characteristics and quality of reporting of cluster randomized trials in children: reporting needs improvement. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hua F, Sun Q, Zhao T. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trial Abstracts presented at the sleep annual meetings: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e029270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon U, Knobloch K. Quality of reporting in sports injury prevention Abstracts according to the CONSORT and STROBE criteria: an analysis of the world Congress of sports injury prevention in 2005 and 2008. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L, Li Y, Li J. Quality of reporting of trial Abstracts needs to be improved: using the CONSORT for Abstracts to assess the four leading Chinese medical journals of traditional Chinese medicine. Trials 2010;11:75 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20615225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin L, Hua F, Cao Q. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trial Abstracts published in leading laser medicine journals: an assessment using the CONSORT for Abstracts guidelines. Lasers Med Sci 2016;31:1583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fleming PS, Buckley N, Seehra J. Reporting quality of Abstracts of randomized controlled trials published in leading orthodontic journals from 2006 to 2011. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2012;142:451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seehra J, Wright NS, Polychronopoulou A. Reporting quality of Abstracts of randomized controlled trials published in dental specialty journals. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2013;13:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiriakou J, Pandis N, Madianos P. Assessing the reporting quality in Abstracts of randomized controlled trials in leading journals of oral implantology. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2014;14:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.CM FJ, Giannakopoulos NN. Quality of reporting in Abstracts of randomized controlled trials published in leading journals of Periodontology and implant dentistry: a survey. J Periodontol 2012;83:1251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menne MC, Pandis N, Faggion CM. Reporting quality of Abstracts of randomized controlled trials related to implant dentistry. J Periodontol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Péron J, You B, Gan HK. Influence of statistician involvement on reporting of randomized clinical trials in medical oncology. Anticancer Drugs 2013;24:306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kloukos D, Papageorgiou SN, Doulis I. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trials published in prosthodontic and implantology journals. J Oral Rehabil 2015;42:914–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pandis N, Polychronopoulou A, Eliades T. An assessment of quality characteristics of randomised control trials published in dental journals. J Dent 2010;38:713–21 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300571210001235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saha S, Saint S, Christakis DA. Impact factor: a valid measure of Journal quality? J Med Libr Assoc 2003;91:42–6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12572533 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trakas K, Addis A, Kruk D. Quality assessment of pharmacoeconomic Abstracts of original research articles in selected journals. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 1997;31:423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McIntosh N. Abstract information and structure at scientific meetings. The Lancet 1996;347:544–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taddio A, Pain T, Fassos FF. Quality of nonstructured and structured Abstracts of original research articles in the British medical Journal, the Canadian Medical association Journal and the Journal of the American Medical association. CMAJ 1994;150:1611–5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8174031 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dupuy A, Khosrotehrani K, Lebbé C. Quality of Abstracts in 3 clinical dermatology journals. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:589–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burns KEA, Adhikari NKJ, Kho M. Abstract reporting in randomized clinical trials of acute lung injury: an audit and assessment of a quality of reporting score*. Critical Care Medicine 2005;33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharma S, Harrison JE. Structured Abstracts: do they improve the quality of information in Abstracts? American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2006;130:523–30 https://www.ajodo.org/article/S0889-5406(06)00893-6/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosen AB, Greenberg D, Stone PW. Quality of Abstracts of papers reporting original cost-effectiveness analyses. Medical Decision Making 2005;25:424–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scherer RW. Reporting of randomized clinical trial descriptors and use of structured Abstracts. JAMA 1998;280:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Einarson TR, Lee C, Smith R. Quality and content of Abstracts in papers reporting about drug exposures during pregnancy. Birth Defect Res A 2006;76:621–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khosrotehrani K, Dupuy A, Lebbé C. [Abstract quality assessment of articles from the Annales de Dermatologie]. Annales de dermatologie et de venereologie 2002;129 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12514515/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wong H, Truong D, Mahamed A. Quality of structured Abstracts of original research articles in the British medical Journal, the Canadian Medical association Journal and the Journal of the American Medical association: a 10-year follow-up study. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2005;21:467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chhapola V, Tiwari S, Brar R. An interrupted time series analysis showed suboptimal improvement in reporting quality of trial Abstract. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;71:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D. Consort statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a consort extension for nonpharmacologic trial Abstracts. Annals of Internal Medicine 2017;167:40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Montgomery P, Grant S, Mayo-Wilson E. Reporting randomised trials of social and psychological interventions: the CONSORT-SPI 2018 extension. Trials 2018;19:407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sarkis-Onofre R, Poletto-Neto V, Cenci MS. Consort endorsement improves the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials in dentistry. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;122:20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blanco D, Altman D, Moher D. Scoping review on interventions to improve adherence to reporting guidelines in health research. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061873supp001.pdf (260.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. https://osf.io/ahzwn/?view_only=e2f08c5c0d2d4936ba88d38968aba5d9.