Dear Editor,

Since the beginning of 2020, the world has been grappling with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Coincidentally, in May 2022, at least 640 suspected or confirmed cases of the monkeypox virus (MPXV) were documented in 36 countries of different continents (Table 1 ) [1]. This virus was first discovered in 1958 by Preben von Magnus in laboratory crab-eating Macaques, Macaca fascicularis [[2], [3], [4]]. MPXV is an enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus of genus orthopoxvirus and family Poxviridae which are all antigenically interrelated and cause relatively similar symptoms. MPXV can infect, and be detected in, a large range of hosts including non-human primates, African squirrels, and rodents [4,5]; its spillover occasionally causes sporadic infections among humans [6].

Table 1.

Distribution of the 641 reported cases of monkeypox among 36 countries (a 30-day profile of monkeypox epidemic; detailed data are available at https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox).

| Countries | May 30, 2022 | Absolute Change |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 2 | +2 |

| Australia | 2 | +2 |

| Austria | 1 | +1 |

| Belgium | 9 | +9 |

| Bolivia | 1 | +1 |

| Brazil | 1 | +1 |

| Canada | 65 | +55 |

| Czechia | 5 | +5 |

| Denmark | 2 | +2 |

| Ecuador | 1 | +1 |

| Finland | 1 | +1 |

| France | 16 | +16 |

| French Guiana | 2 | +2 |

| Germany | 23 | +23 |

| Greece | 1 | +1 |

| Iran | 6 | +6 |

| Ireland | 2 | +2 |

| Israel | 4 | +4 |

| Italy | 16 | +16 |

| Malaysia | 0 | +0 |

| Malta | 1 | +1 |

| Mexico | 1 | +1 |

| Morocco | 3 | +3 |

| Netherlands | 32 | +32 |

| Pakistan | 1 | +1 |

| Peru | 1 | +1 |

| Portugal | 96 | +76 |

| Slovenia | 2 | +2 |

| Spain | 210 | +187 |

| Sudan | 1 | +1 |

| Sweden | 2 | +2 |

| Switzerland | 4 | +4 |

| Thailand | 3 | +3 |

| United Arab Emirates | 4 | +4 |

| United Kingdom | 106 | +97 |

| United States | 14 | +13 |

| World | 641 | +578 |

Implications of the 2022 monkeypox outbreak

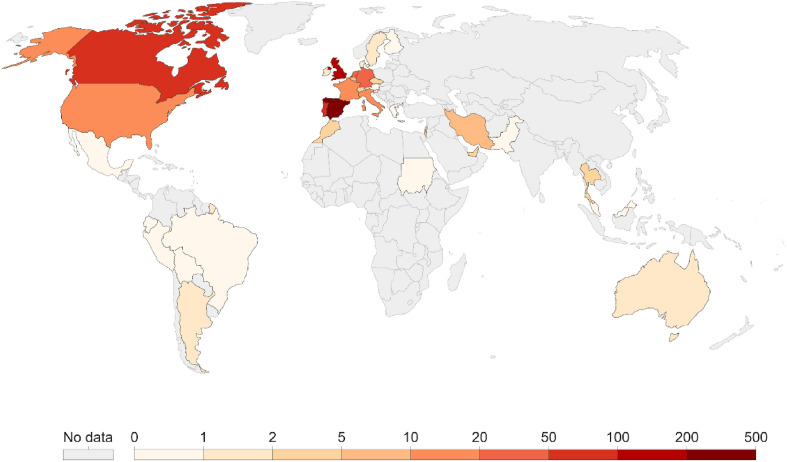

The transition of endemic monkeypox into an epidemic has intensified public-health concerns. The rapid spread of MPXV among distant WHO regions has also reignited debate about its exact transmission routes, especially that cases with the present viral clades have emerged outside the endemic African countries (Fig. 1 , Table 1). This is concerning also because travel links were not found between positive cases in the UK or other countries [7,8], suggesting that MPXV particles may have disseminated by asymptomatic carriers in some regions until they have become detectable as symptomatic cases. Subsequent cases confirm that close contact causes viral transmission.

Fig. 1.

Global distribution of the 641 confirmed or suspected cases of MPXV recorded until 30 May 2022 (https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox).

Clinical symptoms due to zoonotic monkeypox are similar to those caused by the smallpox virus in humans. Nevertheless, MPXV cases are slightly less severe or even sub-clinical compared to smallpox cases. Some patients infected with MPXV, especially immunocompromised individuals, will need hospital care. A considerable proportion of the patients, however, will experience mild symptoms for 2–4 weeks. The case-fatality ratio due to MPXV infections historically has been 1–10%; no fatality has been officially reported during the 2022 outbreak so far. Though the present ongoing outbreak seems to be containable, the case numbers will expectedly increase soon, and this epidemic will grow [9].

Consequently, the priority should be to halt further MPXV transmission and spread to other countries [10]. Investigators should determine if a cluster of mutations may have facilitated efficient recombination to allow MPXV to gain high transmission capability in human hosts [11,12] because MPXV is a DNA virus, and a high mutation rate to facilitate its evolution is inconceivable. Sufficient sequencing evidence will confirm emergence of any new MPXV clade, and expansive sequencing programs will better facilitate the management of the outbreak. Tecovirimat is a useful antiviral against MPXV at least for patients at risk of severe prognoses [11,[13], [14], [15]]; however, this medication is not widely available. Smallpox and monkeypox vaccines are formulated based on a vaccinia virus and confer cross-protection due to immune response to orthopoxviruses. Emergence of the 2022 MPXV outbreak is likely due to abandonment of the global smallpox vaccination programs, rendering a massive proportion of the world population vulnerable to monkeypox because of loss of immunity against orthopoxviruses. Thus, clinical, public-health, and vaccination strategies against members of orthopoxviruses should be revisited and reinvigorated.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, internally peer-reviewed.

Data statement

Not applicable

Funding

None.

Please state whether ethical approval was given, by whom and the relevant Judgement's reference number

This article does not require any human/animal subjects to acquire such approval.

Please state any sources of funding for your research

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contribution

Amin Talebi Bezmin Abadi: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – review & editing.

Farid Rahimi: Writing – Review & editing.

All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript before submitting.

Research registration Unique Identifying number (UIN)

1.Name of the registry: Not applicable.

2.Unique Identifying number or registration ID: Not applicable.

3.Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked):Not applicable.

Guarantor

Both authors.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors’ opinions in this commentary do not necessarily reflect the official strategies by their affiliated institutes.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106712.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.CTV News Monkeypox cases near 200 in more than 20 countries: WHO. 2022. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/monkeypox-cases-near-200-in-more-than-20-countries-who-1.5921034 Available from:

- 2.Magnus P.v., Andersen E.K., Petersen K.B., Birch-Andersen A. A pox-like disease in Cynomolgus monkeys. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1959;46:156–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1959.tb00328.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker S., Buller R.M. A review of experimental and natural infections of animals with monkeypox virus between 1958 and 2012. Future Virol. 2013;8:129–157. doi: 10.2217/fvl.12.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenner F., Wittek R., Dumbell K.R. The Orthopoxviruses. Academic Press; San Diego: 1989. Chapter 8. Monkeypox Virus; pp. 227–267. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . 2022. Monkeypox.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adalja A., Inglesby T. A novel international monkeypox outbreak. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022 doi: 10.7326/M22-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahase E. Monkeypox: what do we know about the outbreaks in Europe and North America? BMJ. 2022;377:o1274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler H., Gould S., Hine P., Snell L.B., Wong W., Houlihan C.F., Osborne J.C., Rampling T., Beadsworth M.B., Duncan C.J., Dunning J., Fletcher T.E., Hunter E.R., Jacobs M., Khoo S.H., Newsholme W., Porter D., Porter R.J., Ratcliffe L., Schmid M.L., Semple M.G., Tunbridge A.J., Wingfield T., Price N.M. N.H.S.E.H.C.I.D. Network. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahase E. Seven monkeypox cases are confirmed in England. BMJ. 2022;377:o1239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awan U.A., Riasat S., Naeem W., Kamran S., Khattak A.A., Khan S. Monkeypox: a new threat at our doorstep. J. Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zumla A., Valdoleiros S.R., Haider N., Asogun D., Ntoumi F., Petersen E., Kock R. Monkeypox outbreaks outside endemic regions: scientific and social priorities. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00354-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozlov M. Monkeypox outbreaks: 4 key questions researchers have. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-01493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoy S.M. Tecovirimat: first global approval. Drugs. 2018;78:1377–1382. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0967-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grosenbach D.W., Honeychurch K., Rose E.A., Chinsangaram J., Frimm A., Maiti B., Lovejoy C., Meara I., Long P., Hruby D.E. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:44–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues Garcia D., Rodrigues de Souza F., Paula Guimaraes A., Castro Ramalho T., Palermo de Aguiar A., Celmar Costa Franca T. Design of inhibitors of thymidylate kinase from Variola virus as new selective drugs against smallpox: part II. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019;37:4569–4579. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1554510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.