Abstract

Purpose of Review

Acute brain injury (ABI) is a broad category of pathologies, including traumatic brain injury, and is commonly complicated by seizures. Electroencephalogram (EEG) studies are used to detect seizures or other epileptiform patterns. This review seeks to clarify EEG findings relevant to ABI, explore practical barriers limiting EEG implementation, discuss strategies to leverage EEG monitoring in various clinical settings, and suggest an approach to utilize EEG for triage.

Recent Findings

Current literature suggests there is an increased morbidity and mortality risk associated with seizures or patterns on the ictal-interictal continuum (IIC) due to ABI. Further, increased use of EEG is associated with better clinical outcomes. However, there are many logistical barriers to successful EEG implementation that prohibit its ubiquitous use.

Summary

Solutions to these limitations include the use of rapid EEG systems, non-expert EEG analysis, machine learning algorithms, and the incorporation of EEG data into prognostic models.

Keywords: Acute brain injury, EEG, seizures, monitoring, Rapid EEG

Introduction

Acute brain injury (ABI) is a broad category of pathologies that includes traumatic brain injury, spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and hypoxic ischemic brain injury. ABI is seen across a variety of clinical settings from emergency departments in community hospitals to neuroscience intensive care units in tertiary care centers. Injuries range from mild to severe with coma or brain death. Commonly used indices to judge severity and prognosis of ABI typically use clinical features (Glasgow Coma Scale, NIH Stroke Scale), imaging (ASPECT), or a combination of both (IMPACT, CRASH). Few prognostic scales incorporate electrographic features found on the electroencephalogram (EEG), such as the presence of seizures and epileptiform discharges, which have important clinical and prognostic implications. In this review, we discuss (1) important EEG findings relevant to ABI, (2) use and practical barriers of EEG in ABI patients, (3) strategies to leverage EEG monitoring in clinical settings where EEG or clinical neurophysiologists are not readily available, and (4) a suggested clinical approach for the use of EEG to quickly triage and manage patients with ABI.

Clinical Significance

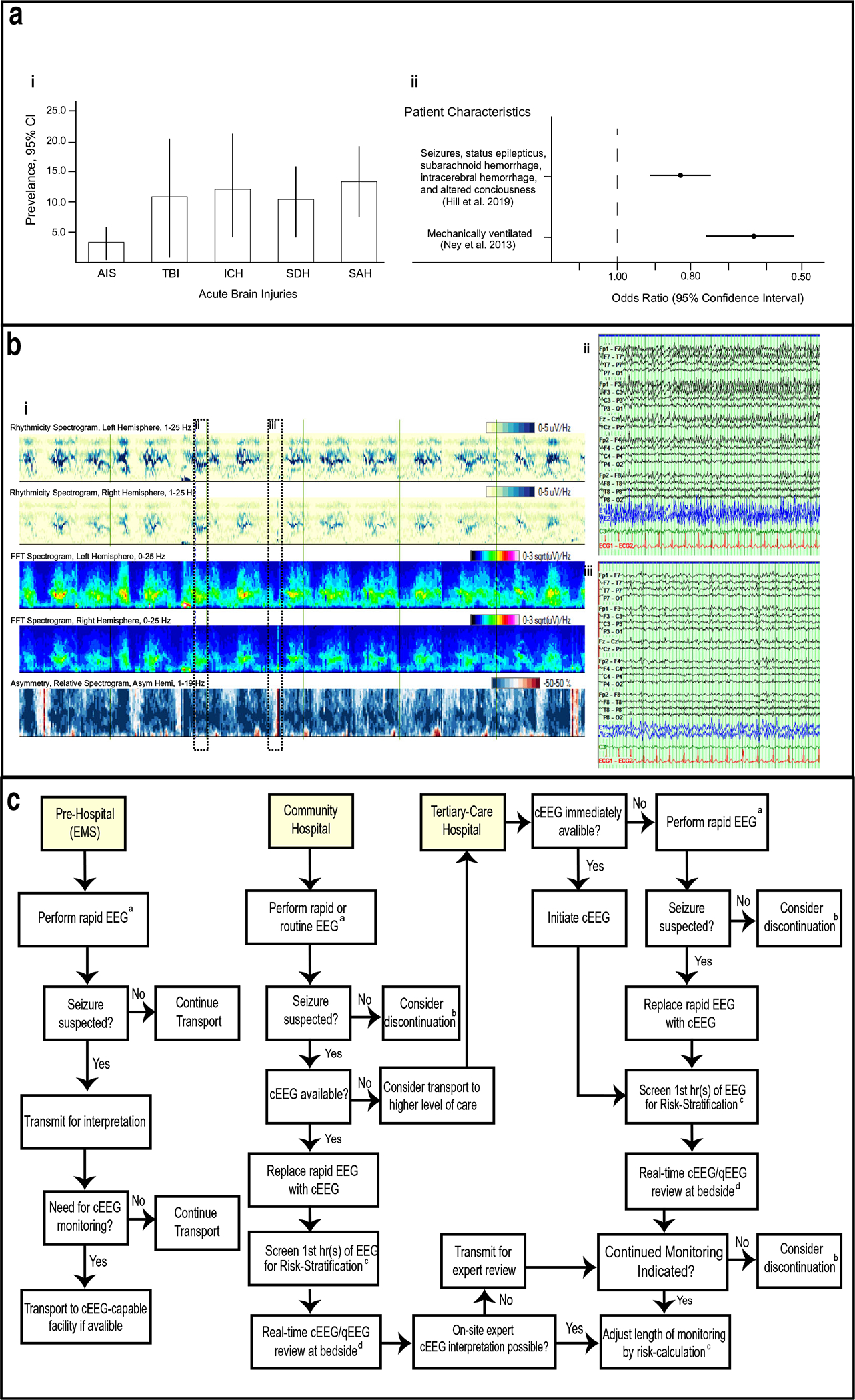

The development of seizures is associated with poor prognosis in patients with acute brain injury [1–6]. Seizures occur in 1.5–3.1% of patients with acute ischemic strokes [1, 7], 9.7–38% of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage [2, 4, 7], and 13.3–31% of those with intracerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 1a) [5, 7]. Seizures are associated with decreased oxygenation of brain tissue, metabolic crises, elevation of intracranial pressure (ICP), and delayed increase in regional cerebral blood flow, all of which affect brain tissue recovery [8•, 9]. Prolonged seizures (particularly those lasting longer than 30 min) are associated with neuronal cell death and increased seizure burden is independently associated with worse neurological outcomes in both adults and children[2, 10–12]. While the risk-benefit balance of aggressive treatment of all seizures associated with ABI remains unclear, accurate and timely diagnosis is important for patient-specific management decisions and prognostication.

Figure 1.

a (i) Seizure prevalence in ABI (adapted from Limotai et al. 2019) (ii) Mortality odds ratios in ABI patients receiving no/routine EEG vs continuous EEG. b (i) Diagram of qEEG recording showing rhythmicity (first two rows), FFT spectrograms (next two rows) and power asymmetry (bottom row). Time period between vertical green lines is 10 min. (ii-iii). Raw EEG trace shown in dotted boxes in (i) showing periods of seizure (ii) and no seizure (iii). Time period between vertical lines is 1 s. c Algorithm to guide use of cEEG in different clinical settings, see section Algorithm for further details. aRapid EEG, or emergency EEG, using technologies and techniques proposed to extend EEG acquisition to pre-hospital and precEEG contexts. bPerform limited study (≤ 6 h) or discontinue. Resume EEG if indicated due clinical concern. cRisk stratification using 2HELPS2B score to adjust monitoring session length. dUse real-time qEEG review and monitoring by bedside staff trained to identify salient EEG features

Seizures with a clinical correlate, such as focal motor or generalized tonic-clonic movements, are more readily identified compared with seizures without overt physical manifestations, termed nonconvulsive seizures (NCSZ). NCSZ, in their most severe form, manifest as prolonged seizures termed non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE). Diagnosis of NCSZ is difficult in patients with ABI, as they often already have altered mental status, which limits the neurological exam. Diagnosis of NCSZ and NCSE relies upon clinical suspicion and EEG monitoring. NCSZ and NCSE have likely been previously underdiagnosed since recent increased use of continuous EEG (cEEG) monitoring has led to higher detection rates for both [13–19]. Early diagnosis of NCSE is particularly important as the longer the duration, the more difficult it becomes to manage [20].

Other EEG findings that are highly associated with seizures but do not qualify as definitive seizures by strict criteria are considered to lie on the ictal-interictal continuum (IIC). These findings, which encompass periodic and rhythmic patterns, are common in ABI patients and may lead to secondary brain injury, thus warranting treatment [21•, 22, 23] or at least a diagnostic treatment trial while undergoing EEG monitoring. These patterns often have seizure-like features, causing clinical symptoms or potential neuronal injury, but fail to meet traditional electrographic criteria for seizures. At other times, these patterns may persist even in the setting of clinical improvement. An example of a highly epileptiform pattern is periodic discharges (PDs) [24]. PDs have been associated with altered consciousness and worse clinical outcomes. Bilateral independent periodic discharges (BIPDS) in particular are highly predictive of mortality and are commonly found in ABIs such as stroke and anoxic brain injury [21•].

PDs in ABI patients have been linked to disruption of metabolic processes and brain tissue homeostasis [8•, 25]. Witsch et al. (2017) found that in subarachnoid hemorrhage, the metabolic demand required by PDs, particularly higher frequency PDs (> 2.0 Hz), is inadequately compensated by a rise in cerebral blood flow, a finding that may lead to brain tissue hypoxia and further injury [8•]. These associations are summarized in Table 1. While no guidelines based on validated algorithms exist on when and how to treat PDs, recognition of PDs on EEG may help guide management.

Table 1.

Association of EEG characteristics and outcomes in acutely brain injured and critically ill patients

| Study Critically ill patients | Year | Sample | Age | Characteristic | Definition of Poor Outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Sainju R, Manganas L, Gilmore E et al. | 2015 | 74 | Pediatric and adult | LPDs | Function decline in mRS ≥1 | 6.4 (.3–17.6), p <0.001 (Unadjusted) 4.8 (.6–15.4), p = .001 |

| Cheng JY | 2016 | 151 | Adult | Treatment of seizures 30 min after onset | In-hospital mortality | p = 0.046 2.06 (1.01–4.17) (Unadjusted) |

| Osman G, Rahangdale R, Britton J et al. | 2018 | 170 | Adult | BEPDs | severe disability, vegetative state or death at hospital discharge | p < 0.006 2.9 (1.4–6.2) |

| Moderate/severe traumatic brain injury | ||||||

| Vespa P, Nuwer M, Nenov V et al. | 1999 | 94 | Adult | NCSE | Death | p < 0.001 |

| Lee H, Mizrahi M, Hartings J et al. | 2019 | 152 | Adult | Delta activity, 24 h | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.002 2.31 (1.19–4.49) |

| Delta activity, 72 h | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.007 2.80 (1.29–6.22) | ||||

| Absence of PDR, 24 h | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.001 3.65 (1.57–8.87) | ||||

| Absence of PDR, 72 h | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.01 3.34 (1.31–9.27) | ||||

| Absence of N2 sleep transients, 24 h | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.001 2.97 (1.55–5.80) | ||||

| Background II or III, anytime | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.005 3.15(1.58–6.18) | ||||

| Discontinuous background, anytime | GOSE 1–4; death, unresponsive wakefulness, or severe disability | p < 0.005 5.29 (22.27–12.84) | ||||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | ||||||

| Claasen J, Hirsch L, Frontera J et al. | 2006 | 756 | Adult | No sleep architecture, 24 h | mRS 4–6 | Adjusted p < 0.023 OR 10.4 |

| No sleep architecture, any | mRS 4–6 | Adjusted p < 0.036 | ||||

| Periodic epileptiform discharges, any | mRS 4–6 | Adjusted p < 0.011 | ||||

| Claassen J, Albers D, Schmidt et al. | 2014 | 479 | Adult | In hospital seizures | mRS 4–6 | 5.7, (2.6–12.8) (Unadjusted) 3.5 (1.2–9.8) |

| De Marchis GM, Pugin D, Meyers E et al. | 2016 | 402 | Adult | Any seizure presence | mRS 4–6 | p < 0.001 3.67 (1.34–10.1) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | ||||||

| Claassen J, Jette N, Chum F. et al. | 2007 | 102 | Adult | PEDs | Glasgow Outcome Score 1–2 | p < 0.001 (Unadjusted) 7.6 (2.1–27.3), p = 0.002 |

| Acute ischemic stroke | ||||||

| Lima F, Ricardo J, Goan A et al. | 2017 | 157 | Adult | Seizures | mRS 3–6 | p = 0.09 2.56 (0.88–7.69) |

| Epileptiform activity | mRS 3–6 | p = 0.001 2.94 (1.51–5.88) (Unadjusted) 2.27 (1.04–5.00), p = 0.04 | ||||

| Interictal epileptiform discharges | mRS 3–6 | p = 0.002 2.94 (1.51–5.88) | ||||

LPD lateral periodic discharges, BIPD bilateral independent periodic discharges, NCSE non-clinical status epilepticus, PDR posterior dominant rhythm, PED periodic electrographic discharges

Use of EEG monitoring

EEG provides a noninvasive means of monitoring neurologic function in critically ill patients and is the gold standard for identifying NCSZ and epileptiform patterns. Ney et al. (2013) found that prolonged monitoring with cEEG was associated with higher inpatient survival in mechanically ventilated patients as opposed to a cohort with equal severity of illness monitored with shorter routine EEG [26••] (Fig. 1b). This result held even in patients without a primary neurologic diagnosis and when patients with epilepsy and convulsions were excluded from the analysis, suggesting that cEEG monitoring may help guide management even when seizures are not the primary concern.

Expanded use of cEEG monitoring has been associated with lower in-hospital mortality for critically ill patients [27]. In a database review of over 7 million ventilated patients, investigators found a 10-fold increase in cEEG use from 2004 to 2013; although cEEG monitoring was more likely to be utilized in clinically sicker patients, its use was associated with lower odds of in-hospital mortality.

Given the number of patients likely to benefit from cEEG and limited capacity of cEEG monitoring at most hospitals, risk stratification of patients into seizure probability groups can be useful for allocating resources and initiating earlier interventions. One recently developed score is the 2HELPS2B, a clinical risk score based on identification of EEG patterns associated with seizure risk [28]. The score ranges from 0 to 7 and is based on variables such as prior seizure, sporadic epileptiform discharges, and lateralized periodic discharges, among others. This score was recently validated in a multicenter retrospective medical record review, which demonstrated that in patients without prior clinical seizures, a low 2HELPS2B score (0 or 1) calculated from a 1-h screening EEG was sufficient to place patients into a low-risk seizure group, whereas a higher 2HELPS2B score (> 1) required at least 24 h of subsequent EEG recording to exclude nonconvulsive seizures with reasonable certainty [29••].

Barriers

In the 2015 Consensus Statement on continuous EEG in Critically Ill Adults and Children, the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) made recommendations for an “idealized” system that requires trained clinical neurophysiologists and technologists. In practice, there are often significant financial and logistical barriers to implementing such a system.

Logistical Barriers

The logistical barriers of EEG include the technical application of cEEG equipment, insufficient availability of trained physicians for interpretation and diagnosis, and the processing of high volumes of data.

Once EEG monitoring is indicated, it may take several hours for electrodes to be placed and recording to begin depending on the clinical setting [30]. This is often due to EEG tech availability and transit time, as well as the labor of placing EEG electrodes, particularly in more challenging cases with thick hair, hair extensions, or recent neurosurgical procedures. Once placed, the EEG electrodes may be removed by patients with altered mental status, requiring technologists to return for reapplication.

More substantial delays can be seen during off-hours when technologist availability is more sparse or nonexistent, requiring staff to commute from home. The estimated time from approval of EEG order to preliminary interpretation of results can range from one to 24 h [31–33]. These logistical problems have provided challenges for critical care cEEG monitoring in intensive care units.

The detection and definitive interpretation of cerebral activity patterns also currently requires the expertise of a trained electroencephalographer [32, 34]. The availability of expert physicians to review real-time continuous EEG is limited. Typically, cEEG recordings are only reviewed twice per day by electroencephalographers, even in high resource settings [2, 32]. Given these relatively limited review times, there can be delays in seizure detection and subsequent treatment. Some of this can be mitigated by use of off-site EEG review (a.k.a., “tele-EEG”) but may be limited by data storage, networking capabilities, and the cost of personnel [32]. However, with advances in server and network technology, these barriers are more easily overcome.

The initiation of EEG in certain environments is also challenging and can limit its availability. For instance, in a busy emergency department with limited staffing, small rooms, and extensive electrical noise, the use of cEEG may be difficult. More controlled and secure environments, such as the ICU, lend themselves to an increased ability to perform high quality EEG recordings. However, even with private rooms and increased staffing to monitor patients and prevent electrode removal, the ICU setting frequently contains signal contamination from nearby machines [35••].

Financial Barriers

Given the amount of resources needed to implement cEEG monitoring, it is unsurprising that such monitoring comes at a significant cost. The costs of EEG originate from the purchase and maintenance of the machines, staffing technicians to place and remove electrodes, and physicians for time spent analyzing cEEG. These costs increase significantly during each additional hour of monitoring [36]. According to Medicare.org, the average cost for a routine EEG is between $200.00 and $700.00, with similar costs for cEEG [26, 27]. However, studies demonstrate the total cost of continuous EEG for neurointensive care unit patients accounted for only 1 to 5% of the cost of their hospital stay [26]. The benefits of early detection and treatment of NCSZ and NCSE suggest that cEEG use and impact on patient care may outweigh its cost.

Geographic Barriers

With the stated logistical and financial barriers, initiation of cEEG monitoring, the frequency of review, and communication of results are all determined by local resources that, in practice, vary considerably between institutions. The “ideal” system put forth by ACNS has best been implemented at tertiary care centers with the resources to afford both the physicians and technologists needed for its implementation. Specifically, its implementation has been best achieved within neuroscience intensive care units (Neuro ICU), which have the ability to integrate EEG monitoring into daily care.

While the presence of Neuro ICUs is growing, access to a Neuro ICU remains varied. A 2012 study cited that only 67.3% of the US population has access to a Neuro ICU within 90 min via air ambulance [37]. While the northeast has the highest rate of access, and the South the lowest, variability within regions is high. A large proportion of patients in these low-access areas must rely on community hospitals and smaller centers for their first line of care. With acute brain injury, the first several hours are crucial [38•], making early access to cEEG monitoring more vital.

In 2018, one community hospital group implemented a continuous video EEG program using bedside providers instead of EEG technologists for lead placement [39••]. After 3 years, a total of 92 studies were performed with increasing utilization of cEEG each year. Of the 92 patients studied, 25 had seizures on video EEG, and 18 of those were successfully treated at the community hospital [39••]. This program was implemented with the smallest possible financial and logistical cost to limit the burden on hospital and staff members. Nontechnologists were able to initiate monitoring with the use of disposable, MRI compatible, and electrode templates. Data storage and interpretation of cEEGs merged with the existing hospital system, and the cEEG monitoring machine utilized was borrowed from a larger partner hospital. However, not all community hospitals would be able to adopt such a program without the support of a larger institution. Thus, despite evidence of the benefit of cEEG monitoring in patients with ABI, adoption has been slow outside of tertiary centers due to the aforementioned logistical and financial barriers.

There have been several recent technological developments aiming to improve the ease of cEEG deployment, both in the prehospital, emergency room, and inpatient settings. These products, discussed later are easier and faster to apply to the patient and have novel functionalities that improve the rate of seizure detection and treatment.

Rapid EEG Systems

Recent EEG products have worked to lower some of these barriers and broaden the use of EEG to a wider number of clinical environments. Portable, easy to apply systems may extend EEG monitoring into the prehospital setting. Devices such as a quick-application cap and wireless computer transmission was developed and specifically applied to prehospital environments such as ambulances [40]. An accelerometer was included in the headcap to record patient movement due to ambulance motion, allowing clinicians to distinguish physiologic signals from motion artifact. Further development and validation of the device is needed, though it shows promise in advancing prehospital electroencephalography.

In the hospital setting, new EEG acquisition products have increased the feasibility of initiating EEG monitoring. A recently developed portable EEG system, consisting of a portable EEG monitoring recorder and 10-lead headband, requires little training to set up and can be applied in < 10 min. A 19-channel, dry-electrode EEG system has been developed that similarly reduces application time and is wireless, utilizing Wi-Fi to upload EEG data in real-time to cloud-accessible servers [41]. Other systems incorporate a “peel and stick” design that allows for the quick application of a disposable, 18-lead headband by nonexpert staff [42]. Compact, portable, and easy to apply EEG devices may not only increase EEG accessibility in ICU settings but also in emergency departments where space or staffing may be a limitation to initiating a conventional EEG. These systems decrease the amount of time necessary to obtain an EEG recording without significantly decreasing its diagnostic utility [35]. In clinical settings with limited access to cEEG or 24-h EEG technicians, where seizures are suspected, these systems can be placed by house-staff, nurses, or other clinical staff to quickly assess for NCSZ or NCSE.

Reduced montage configurations can miss certain types of focal seizures, mainly those in the parasagittal region. Nevertheless, a recent study suggests that the majority of clinically significant EEG patterns in critical care and emergency settings can be detected with fewer electrodes that are included in the conventional 10–20 EEG system [38].

Rapid EEG systems, such as those described above, may provide a simplified way to bridge the gap between the demand for EEG and the logistical constraints of traditional systems.

Advancements in Nonexpert EEG Analysis

The gold standard for interpreting cEEG data is visual inspectionby a trained clinical neurophysiologist. However, analysis of cEEG data spanning hours to days is time intensive. In many settings, particularly community hospitals where a neurophysiologist is not readily available, this is not feasible. More resource and time efficient methods to analyze and interpret the data are needed. Strategies to address this include the use of quantitative (qEEG), training nonexperts to identify simple cEEG or qEEG patterns relevant to ABI, and the use of automated seizure detection algorithms.

QEEG consists of a simplified, time compressed view of cEEG data displaying values such as frequency, power/amplitude, entropy, functional connectivity, rhythmicity, and brain asymmetry [43]. Such compressed views allow for faster interpretation and shorter review times of EEG data (Fig. 1b) [44]. The sensitivity of seizure detection by qEEG ranges between 67 and 90%, depending on the approach used [45, 46]. Using qEEG as a screening tool may still fail to enable detection of more nuanced seizure-related features that would otherwise be detected by trained physicians directly reviewing the raw EEG. For example, seizures that are not detected are typically low amplitude, short duration, and focal [47]. Higher specificities are seen when readers are able to corroborate findings by referring to the raw EEG trace. This is particularly important in the ICU setting where artifacts from chest physiotherapy/bed percussion, ventilators, etc. can be mistaken for seizures, potentially leading to unnecessary interventions that may lengthen ICU stay. Nevertheless, the use of qEEG may allow for faster seizure detection and therefore earlier interventions in ABI patients.

While trained clinical neurophysiologists are available at large academic centers, most community hospitals do not have easy access to neurophysiologists to interpret cEEG. This can lead to a delay in EEG reads as they would need to first be interpreted remotely based on availability of a neurophysiologist, subsequently postponing the triage and treatment of ABI patients. Even in most academic centers, cEEG data is only periodically reviewed and not continually monitored. A more efficient method would be to train nonexperts such as ED physicians, bedside nurses, or physician assistants to identify seizures in ABI patients in order to influence earlier interventions (Table 2). One study used a simple training module to improve the ability of ED physicians to correctly identify seizures on single page snapshots of cEEG data [48]. ICU nurses and nonneurophysiologists have been successfully trained to read qEEG to detect seizures in the ICU setting with sensitivities approaching those of trained neurophysiologists [49]. Training need not be time intensive, as in one study it consisted of a 2-h one-on-one session followed by supervised review of 27 cEEG recordings [50•]. Additionally, use of qEEG by nurses at the bedside in real time resulted in 85% sensitivity and 90% specificity after training [51]. However, smaller, focal seizures were not as readily detected. Less well-studied are the ability of nonexperts to identify features along the ictal-interictal continuum. While experts can readily identify most features with favorable interrater reliability [52], the ability of nonexperts has to date not been fully explored.

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of EEG interpreters with varying levels of training reading qEEG or conventional EEG

| Study | Year | Sample | Age | Interpreters | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Stewart CP, Otsubo H, Ochi A, et al. | 2010 | 27 | Pediatric | 3 Neurophysiologists | 82% | FP: 0–0.19/h |

| Pensirikul AD, BEslow LA, Kessler SK, et al. | 2013 | 21 | Pediatric | 8 Neurophysiologists | 65–75% | 78–92% |

| Moura L, Shafi MM, NG M, et al. Williamson CA, Walhster S, Shafi M, et al. | 2014 | 118 | Adult | 3 Neurophysiologists | 87–89% | NR |

| Dericioglu N, Yetum E, Bas DF, et al. | 2015 | 20 | Adult | 2 ICU fellows 2 ICU RNs |

88–99% | 89–95% |

| Siwsher CB, White CR, Mace BE, et al. | 2015 | 45 | Adult | 5 Neurophysiologists 7 EEG technologists 5 ICU RNs |

80–87% | 61–80% |

| Topjian AA, Fry M, Jawad AF, et al. | 2015 | 39 | Pediatric | 12 ICU MDs 8 ICU fellows 19 ICU RNs |

70% | 68% |

| Haider HA, Esteller R, Hahn CD, et al. | 2016 | 15 | Adult | 9 Neurophysiologists | 67% | FP: 1/h |

| Amorim E, Williamson CA, Moura L, et al. | 2017 | 30 | Adult | 33 ICU RNs4 Neurophysiologists | 74%66% | 38%69% |

| Du Pont-Thibodeau G, Sanchez SM, Jawad JF, et al. | 2017 | 39 | Pediatric | 6 ICU MDs 12 ICU fellows 5 ICU RNs |

77% | 65% |

| Lalgudi Ganesan S, Steward CP, Atenafu EG, et al. | 2018 | 22 | Pediatric | 3 Neurophysiologists 3 EEG technologists 3 ICU fellows 3 ICU RNs |

67–84% | FP: 0–4.2/24 h |

| Sun J, Ma D, Lv Y | 2018 | 30 | Adult | 3 Neurophysiologists | 81% | FP: 2/24 h |

| Kang JH, Sherill GC, Sinha SR, Swisher CB | 2019 | 21 | Adult | NR ICU RNs | 85% | 90% |

More recently, there has been significant interest in the potential use of machine learning algorithms for the purpose of automated seizure detection. Machine learning is a type of classification system wherein users train the machine, or algorithm, to predict desired outcomes. In a series of studies of machine learning algorithms in known epilepsy patients, sensitivity of seizure detection ranged from 75 to 90% [53]. However, most studies have used patient specific predictors that were then tested on the same patient and thus were not generalizable. An automated detector that can be used for ABI patients must be able to quickly and reliably identify multiple types of seizures originating in different parts of the brain. While still in its infancy, this would represent a powerful tool to drastically lower time spent interpreting vast amounts of EEG data. However, a major limit of machine learning is the need for large amounts of data in order to use more sophisticated training methods, thus necessitating more time intensive methods for development.

Seizure detection can be achieved, with varying levels of sensitivity and specificity, by trained neurophysiologists, non-experts, and some machines. However, a large component of clinical management of ABI patients is driven by estimates of prognosis. Therefore, models of outcome prognostication utilizing cEEG data can add invaluable information for the clinician and patient families. For instance, delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) detection can be facilitated with the use of cEEG [54]. Additionally, in traumatic brain injury (TBI), the International Mission for Prognosis and Clinical Trial Design (IMPACT) Score is the best available predictor for neurologic outcome after TBI [55]. The IMPACT score takes into account static variables present upon admission, such as age, motor score, pupils, hypoxia, hypotension, and imaging findings. However, IMPACT falls short when it comes to incorporating dynamic assessment over time or EEG findings. Efforts have been made to incorporate IMPACT scores into machine learning algorithms alongside qEEG data [56]. However, to date there is not one standardized scoring system for predicting functional outcomes in TBI patients incorporating cEEG. Similarly, other forms of ABI also lack prognostication tools with integrated cEEG data.

Algorithms

Based on the above data, we believe a number of strategies can be implemented to improve upon the feasibility of monitoring ABI patients with EEG (Fig. 1c). In the prehospital setting, a rapid EEG system can be applied. The system should provide easily interpretable diagnostic information. If a seizure is suspected, the EEG could be transmitted to a trained hospital physician for review and to determine the utility of diversion to a cEEG-capable facility. In a community hospital setting, an initial rapid, or routine if available, EEG can be used as a brief screen. If seizures are suspected and local capacity for cEEG exists, then patients can be transition to cEEG with bedside review of either qEEG or raw EEG data. If necessary, the cEEG can be transmitted for expert review and further stratification. If the patient is at high risk for continued seizures or cEEG is unavailable at the local institution, transfer should be initiated to a tertiary medical center. Finally, a similar paradigm could be implemented at the tertiary medical center, where rapid EEG is initiated to facilitate immediate monitoring with eventual transition to cEEG as time allows.

Conclusions

It is clear that EEG findings, both ictal and interictal, play important roles in the triaging, management, and prognosis of patients with ABI. Despite cEEG’s proven efficacy, numerous barriers have slowed its ubiquitous adoption across a variety of clinical environments. We have discussed possible solutions to these barriers including the development of rapid-EEG systems for faster placement when skilled EEG techs are not available, use of qEEG for quicker interpretation of large amounts of cEEG data, training of nonexperts to identify salient EEG features, and the possibility of machine learning for automatic interpretation.

Rapid-EEG technology provides an intriguing option, particularly, in settings that lack the necessary staffing to place conventional EEG electrodes. However, these either have practical limitations or incomplete scalp coverage. To what extent this limitation has on the identification of seizures and ultimately outcome is not well studied. Development of rapid EEG technology that combines the ease of use of the rapid EEG systems with the resolution of conventional EEG would increase the adoption of EEG in clinical settings. However, important questions remain about the use of rapid EEG in ABI and implementation of the novel strategies presented.

Further studies on optimal cEEG duration would inform important decisions impacting the availability of this currently limited resource. There is some evidence to support a brief initial EEG review in order to calculate future seizure risk [57] and guide decisions on EEG continuation for those at high risk. However, this quick screening model would benefit from further clinical implementation in order to better study its efficacy.

While the main focus of this article was on the importance of cEEG in ABI to detect seizures, the utility of managing patterns on the IIC continues to pose a significant challenge. While Witsch et al. (2017) demonstrated a possible mechanism on how PDs can negatively impact injured brain, the exact pathophysiology of this process remains unknown. Understanding underlying mechanisms of brain injury in the setting of epileptiform abnormalities would inform the decisions of when and how various IIC patterns should be managed.

To further democratize the use of EEG, a systematic training paradigm must be developed to allow nonexperts the ability to quickly recognize concerning EEG features and triage ABI patients to higher levels of care. This could be facilitated by further training and integration of qEEG features by non-expert staff. Alternatively, warning systems could be developed which would trigger expert review, as is done with EKG. With further data, formal guidelines on nonexpert roles would be helpful to streamline the EEG interpretation process while ensuring accuracy of reads.

Finally, a clear clinical algorithm which takes into account various clinical settings, clinical presentations, and access to EEG will help to triage those patients in which timely interventions will significantly improve morbidity and mortality. Ideally, such an algorithm would take advantage of rapid-EEG systems and rapid interpretation to quickly deliver the appropriate level of care.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Human and Animal Rights All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Huang CW, Saposnik G, Fang J, Steven DA, Burneo JG. Influence of seizures on stroke outcomes: a large multicenter study. Neurology. 2014;82(9):768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Marchis GM, Pugin D, Meyers E, Velasquez A, Suwatcharangkoon S, Park S, et al. Seizure burden in subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with functional and cognitive outcome. Neurology. 2015/12/25. 2016;86(3):253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purandare M, Ehlert AN, Vaitkevicius H, Dworetzky BA, Lee JW. The role of cEEG as a predictor of patient outcome and survival in patients with intraparenchymal hemorrhages. Seizure. 2018/08/24. 2018;61:122–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claassen J, Perotte A, Albers D, Kleinberg S, Schmidt JM, Tu B, et al. Nonconvulsive seizures after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Multimodal detection and outcomes. Ann Neurol. 2013. Jul [cited 2016 Jan 15];74(1):53–64. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3775941&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claassen J, Jetté N, Chum F, Green R, Schmidt M, Choi H, et al. Electrographic seizures and periodic discharges after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology [Internet]. 2007. Sep 25 [cited 2016 Jan 5];69(13):1356–65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17893296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vespa PM, Nuwer MR, Nenov V, Ronne-Engstrom E, Hovda DA, Bergsneider M, et al. Increased incidence and impact of nonconvulsive and convulsive seizures after traumatic brain injury as detected by continuous electroencephalographic monitoring. J Neurosurg. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limotai C, Ingsathit A, Thadanipon K, McEvoy M, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. How and whom to monitor for seizures in an ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(4):e366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.•. Witsch J, Frey HP, Schmidt JM, Velazquez A, Falo CM, Reznik M, et al. Electroencephalographic periodic discharges and frequency-dependent brain tissue hypoxia in acute brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(3):301–9 This study shows that high frequency periodic discharges create a harmful metabolic demand-supply mismatch that is detectable by continuous EEG.

- 9.Vespa P, Tubi M, Claassen J, Buitrago-Blanco M, McArthur D, Velazquez AG, et al. Metabolic crisis occurs with seizures and periodic discharges after brain trauma. Ann Neurol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujikawa DG. The temporal evolution of neuronal damage from pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Brain Res. 1996;725(1):11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, Rossetti AO, Scheffer IE, Shinnar S, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus – report of the ILAE task force on classification of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne ET, Zhao XY, Frndova H, McBain K, Sharma R, Hutchison JS, et al. Seizure burden is independently associated with short term outcome in critically ill children. Brain. 2014;137(5):1429–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claassen J, Mayer SA., Kowalski RG, Emerson RG, Hirsch LJ. Detection of electrographic seizures with continuous EEG monitoring in critically ill patients. Neurology [Internet]. 2004. May 24 [cited 2014 Oct 13];62(10):1743–8. Available from: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000125184.88797.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman D, Claassen J, Hirsch LJ. Continuous electroencephalogram monitoring in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(2):506–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Towne AR, Waterhouse EJ, Boggs JG, Garnett LK, Brown AJ, Smith JR, et al. Prevalence of nonconvulsive status epilepticus in comatose patients. Neurology [Internet]. 2000. Jan 25 [cited 2014 Oct 13];54(2):340–340. Available from: 10.1212/WNL.54.2.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy JD, Gerard EE. Continuous EEG monitoring in the intensive care unit. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep [Internet]. 2012. Aug [cited 2014 Oct 13];12(4):419–28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22653639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narayanan JT, Murthy JMK. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in a neurological intensive care unit: profile in a developing country. Epilepsia. 2007;48:900–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman ST, Abend NS, Bleck TP, Chapman KE, Drislane FW, Emerson RG, et al. Consensus statement on continuous EEG in critically ill adults and children, Part I: Indications. J Clin Neurophysiol [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2018 Oct 4];32(2):87. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4435533/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caricato A, Melchionda I, Antonelli M. Continuous electroencephalography monitoring in adults in the intensive care unit. Critical Care. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazarati AM, Baldwin RA, Sankar R, Wasterlain CG. Time-dependent decrease in the effectiveness of antiepileptic drugs during the course of self-sustaining status epilepticus. Brain Res.1998;814(1–2):179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.•. Osman G, Rahangdale R, Britton JW, Gilmore EJ, Haider HA, Hantus S, et al. Bilateral independent periodic discharges are associated with electrographic seizures and poor outcome: a case-control study. Clin Neurophysiol 2018/09/19. 2018;129(11): 2284–9 This study shows that BIPDs are independent predictors of mortality andhighly prevelant in patients with disorders of conciousness.

- 22.Sivaraju A, Gilmore EJ. Understanding and managing the ictal-interictal continuum in neurocritical care. Curr Treat Options Neurol [Internet]. 2016. Feb 13 [cited 2017 Jan 6];18(2):8. Available from: 10.1007/s11940-015-0391-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cormier J, Maciel CB, Gilmore EJ. Ictal-interictal continuum: when to worry about the continuous electroencephalography pattern. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2017/12/21. 2017;38(6):793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsch LJ, LaRoche SM, Gaspard N, Gerard E, Svoronos A, Herman ST, et al. American clinical neurophysiology society’s standardized critical care EEG terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(1):1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sainju RK, Manganas LN, Gilmore EJ, Petroff OA, Rampal N, Hirsch LJ, et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of lateralized periodic discharges in patients without acute or progressive brain injury: a case-control study. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2015/07/23. 2015;32(6):495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.••. Ney JP, van der Goes DN, Nuwer MR, Nelson L, Eccher MA. Continuous and routine EEG in intensive care: utilization and outcomes, United States 2005–2009. Neurology. 2013/11/05. 2013;81(23):2002–8 This study shows that mechanically ventilated patients who received continuous EEG have significantly less in hospital mortality when compared to those receiving routine EEG.

- 27.Hill CE, Blank LJ, Thibault D, Davis KA, Dahodwala N, Litt B, et al. Continuous EEG is associated with favorable hospitalization outcomes for critically ill patients. Neurology [Internet]. 2019. Jan 1 [cited 2019 may 27];92(1):e9–18. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30504428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Struck AF, Ustun B, Ruiz AR, Lee JW, LaRoche SM, Hirsch LJ, et al. Association of an electroencephalography-based risk score with seizure probability in hospitalized patients. JAMA Neurol. 2017/10/21. 2017;74(12):1419–24 Using machine learning, the authors developed the 2HELPS2B scale, a 7-point scale that incorporates early EEG elements and clinical history to predict seizures risk in critically ill patients.

- 29.••. Struck AF, Tabaeizadeh M, Schmitt SE, Ruiz AR, Swisher CB, Subramaniam T, et al. Assessment of the validity of the 2HELPS2B score for inpatient seizure risk prediction. JAMA Neurol. 2020/01/14. 2020. This study validates the 2HELPS2B score in a large cohort and also shows that one hour of screening EEG is sufficient to accurately compute a 2HELPS2B score and determine appropriate monitoring session length.

- 30.Gururangan K, Razavi B, Parvizi J. Utility of electroencephalography: experience from a U.S. tertiary care medical center. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(10):3335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quigg M, Shneker B, Domer P. Current practice in administration and clinical criteria of emergent EEG. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:162–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herman ST, Abend NS, Bleck TP, Chapman KE, Drislane FW, Emerson RG, et al. Consensus statement on continuous EEG in critically ill adults and children, part II: personnel, technical specifications, and clinical practice. J Clin Neurophysiol 2015/01/30. 2015;32(2):96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baang HY, Swingle N, Sajja K, Madhavan D, Taraschenko O. Pharmacological treatment of status epilepticus at UNMC: assessment of seizure outcomes (P2.5–025). Neurology. 2019;92(15 Supplement):P2.5–025. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheuer ML. Continuous EEG monitoring in the intensive care unit. Epilepsia. 2002/06/13. 2002;43 Suppl 3:114–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.••. Kamousi B, Grant AM, Bachelder B, Yi J, Hajinoroozi M, Woo R. Comparing the quality of signals recorded with a rapid response EEG and conventional clinical EEG systems. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2019;4:69–75 Through both a concurrent and consecutive study, the authors shows that the Ceribell rapid-response system is statistically similar in diagnostic quality to conventional systems but can be placed more easily and rapidly by bedside staff.

- 36.Abend NS, Topjian AA, Williams S. How much does it cost to identify a critically ill child experiencing electrographic seizures? J Clin Neurophysiol. 2015/01/30. 2015;32(3):257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward MJ, Shutter LA, Branas CC, Adeoye O, Albright KC, Carr BG. Geographic access to US Neurocritical Care Units registered with the Neurocritical Care Society. Neurocrit Care 2011/11/03. 2012;16(2):232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.•. Westover MB, Gururangan K, Markert MS, Blond BN, Lai S, Benard S, et al. Diagnostic value of electroencephalography with ten electrodes in critically ill patients. Neurocrit Care. 2020/02/09. 2020. This study shows that a 10-electrode circumferential configuration retains key EEG features and that inter-rater reliability and concordance is high when comparing reduced system readings to traditional EEG readings.

- 39.••. Kolls BJ, Mace BE, Dombrowski KE. Implementation of continuous video-electroencephalography at a community hospital enhances care and reduces costs. Neurocrit Care 2017/10/27. 2018;28(2):229–38 These authors successfuly implemented a continuous EEG program into their existing workflow at a very low cost and with measurable benefits.

- 40.Jakab A, Kulkas A, Salpavaara T, Kauppinen P, Verho J, Heikkila H, et al. Novel wireless electroencephalography system with a minimal preparation time for use in emergencies and prehospital care. Biomed Eng Online 2014/06/03. 2014;13:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zarroli K, Alexander H, Bauer D, Tanabe S, Hucek C, Quigg M. Validation of a dry-electrode EEG recording system: results of a multi-reader blinded comparison to standard EEG (P4.5–009). Neurology. 2019;92(15 Supplement). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ladino LD, Voll A, Dash D, Sutherland W, Hernández-Ronquillo L, Téllez-Zenteno JF, et al. StatNet electroencephalogram: a fast and reliable option to diagnose nonconvulsive status Epilepticus in emergency setting. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;43(2):254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kramer AH, Kromm J. Quantitative Continuous EEG: Bridging the gap between the ICU bedside and the EEG interpreter. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(3):499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moura LMVR, Shafi MM, Ng M, Pati S, Cash SS, Cole AJ, et al. Spectrogram screening of adult EEGs is sensitive and efficient. Neurology [Internet]. 2014. Jul 1 [cited 2014 Oct 13];83(1):56–64. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24857926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esteller R, Hahn CD, Halford JJ, Lee JW, Shafi MM, Gaspard N, et al. Sensitivity of quantitative EEG for seizure identification in the intensive care unit. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson C, Wahlster S, Shafi MM, Westover MB. Sensitivity of compressed spectral arrays for detecting seizures in acutely ill adults. Neurocrit Care [Internet]. 2014. Feb [cited 2014 Oct 13];20(1):32–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24052456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart CP, Otsubo H, Ochi A, Sharma R, Hutchison JS, Hahn CD. Seizure identification in the ICU using quantitative EEG displays. Neurol Int. 2010;75(17):1501–8. Available from:. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f9619e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chari G, Yadav K, Nishijima D, Omurtag A, Zehtabchi S. Improving the ability of ED physicians to identify subclinical/electrographic seizures on EEG after a brief training module. Int J Emerg Med. 2019;12(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amorim E, Rittenberger JC, Zheng JJ, Westover MB, Baldwin ME, Callaway CW, et al. Continuous EEG monitoring enhances multimodal outcome prediction in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Resuscitation. 2016/08/25. 2016;109:121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.•. Lalgudi Ganesan S, Stewart CP, Atenafu EG, Sharma R, Guerguerian AM, Hutchison JS, et al. Seizure identification by critical care providers using quantitative electroencephalography. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):e1105–11 The authors show that hospital staff demonstrate similar sensitivity for seizure detection as neurophysiologist after one-on-one training sessions.

- 51.Kang JH, Sherill GC, Sinha SR, Swisher CB. A trial of real-time Electrographic seizure detection by Neuro-ICU nurses using a panel of quantitative EEG trends. Neurocrit Care. 2019;31(2):312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jing J, Sun H, Kim JA, Herlopian A, Karakis I, Ng M, et al. Development of expert-level automated detection of epileptiform discharges during electroencephalogram interpretation. JAMA Neurol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abbasi B, Goldenholz DM. Machine learning applications in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2019;60(10):2037–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo Y, Fang S, Wang J, Wang C, Zhao J, Gai Y. Continuous EEG detection of DCI and seizures following aSAH: a systematic review. British Journal of Neurosurgery. Taylor and Francis Ltd; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray GD, Butcher I, McHugh GS, Lu J, Mushkudiani NA, Maas AIR, et al. Multivariable prognostic analysis in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(2):329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haveman ME, Putten MJAM Van, Hom HW, Eertman-meyer CJ, Beishuizen A, Tjepkema-Cloostermans MC. Predicting outcome in patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury using electroencephalography 2019;1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Struck AF, Rodriguez-Ruiz AA, Osman G, Gilmore EJ, Haider HA, Dhakar MB, et al. Comparison of machine learning models for seizure prediction in hospitalized patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]