This cohort study uses US Veterans Health Administration data to assess the association of prostate-specific antigen screening with prostate cancer–specific mortality among non-Hispanic Black men and non-Hispanic White men.

Key Points

Question

What are outcomes after prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening among non-Hispanic Black men, and how do they compare with those among non-Hispanic White men?

Findings

In this cohort study of 45 834 US veterans, PSA screening was associated with decreased risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) among Black men and White men. Compared with less frequent screening, annual screening was associated with decreased risk of PCSM among Black men but not among White men.

Meaning

The findings suggest that PSA screening is associated with decreased risk of PCSM among both Black men and White men and that annual screening may be particularly important for Black men.

Abstract

Importance

Black men have higher prostate cancer incidence and mortality than non-Hispanic White men. However, Black men have been underrepresented in clinical trials of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening; thus, there is a lack of data to guide screening recommendations for this population.

Objective

To assess whether PSA screening is associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) among non-Hispanic Black men.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used data from the US Veterans Health Administration Informatics and Computing Infrastructure for men aged 55 to 69 years who self-identified as non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic White and were diagnosed with intermediate-, high-, or very high–risk prostate cancer from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2017. Data were analyzed from August 2021 to March 2022.

Exposures

Prostate-specific antigen screening rate, defined as the percentage of years in which PSA screening was conducted during the 5 years before diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was risk of PCSM among Black men and White men. The association between PSA screening and risk of PCSM was assessed using Fine-Gray regression analysis. Risk of PCSM was also assessed categorically among patients classified as having no prior PSA screening, some screening (less than annual), or annual screening in the 5 years before diagnosis.

Results

The study included 45 834 veterans (mean [SD] age, 62.7 [3.8] years), of whom 14 310 (31%) were non-Hispanic Black men and 31 524 (69%) were non-Hispanic White men. The PSA screening rate was associated with a lower risk of PCSM among Black men (subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR], 0.56; 95% CI, 0.41-0.76; P = .001) and White men (sHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46-0.75; P = .001). On subset analysis, annual screening (vs some screening) was associated with a significant reduction in risk of PCSM among Black men (sHR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46-0.92; P = .02) but not among White men (sHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.74-1.11; P = .35).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, PSA screening was associated with reduced risk of PCSM among non-Hispanic Black men and non-Hispanic White men. Annual screening was associated with reduced risk of PCSM among Black men but not among White men, suggesting that annual screening may be particularly important for Black men. Further research is needed to identify appropriate populations and protocols to maximize the benefits of PSA screening.

Introduction

Randomized clinical trials evaluating prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer are limited by the underrepresentation of Black men. Less than 5% of participants in a US-based trial were Black,1 and representation in European trials is presumed to be low.2,3 Black men have higher prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) compared with non-Hispanic White men, likely reflecting systemic inequities in health care access and delivery, social determinants of health, and possible differences in tumor biology.4 Prostate-specific antigen screening among Black men may be associated with reductions in these disparities in mortality.5,6 However, more data on screening are needed to develop appropriate, personalized recommendations for Black men.7 Our objective was to investigate whether previous PSA screening was associated with decreased PCSM risk among non-Hispanic Black men and non-Hispanic White men with prostate cancer in a racially diverse cohort of US veterans.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Veterans Health Administration Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Inclusion criteria were men aged 55 to 69 years who were diagnosed with intermediate-, high-, or very high–risk prostate cancer based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria8 from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2017, and who self-identified as non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic White. Data were analyzed from August 2021 to March 2022. This study was approved by the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Informed consent was waived because the research was deemed to pose no more than minimal risk to participants. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. The primary end point of the study was PCSM, with the hypothesis that prior screening would be associated with a similar, if not larger, reduction in risk of PCSM among Black men compared with White men.

Patient information, including age, year of diagnosis, employment status, marital status, tobacco use, Agent Orange exposure, Gleason score, PSA level, and cancer stage, was recorded at diagnosis. Median income and educational level were estimated from US census data for the patient’s zip code. We recorded the number of years before diagnosis in which each patient visited a primary care practitioner (PCP) at least once during the year. The percentage of years with 1 or more PCP visit of the 5 years preceding diagnosis was defined as the PCP visit rate.

Screening was analyzed continuously based on the percentage of years in which 1 or more PSA screening was conducted of the 5 years before diagnosis (similar to the PCP visit rate). For example, a patient with 1 or more PSA screening in 3 of 5 years preceding diagnosis would have a screening rate of 0.6. Screening was also analyzed categorically, and patients were classified as having no previous PSA screening, 1 or more PSA screening in the 5 years preceding diagnosis (some screening), or 1 or more PSA screening in each of the 5 years preceding diagnosis (annual screening).

Baseline comparisons were conducted using χ2 tests for categorical variables, 2-proportion z tests for proportional variables, and t tests for continuous variables. Fine-Gray regression analysis assessed the association between screening and risk of PCSM. Patients were censored at the time of death from causes other than prostate cancer (considered a competing event for PCSM) or at the time of their last follow-up visit. Survival times were adjusted by withholding estimated lead times for each patient during analysis.6,9 Missing values were binned into unknown (categorical) or were imputed with the median (continuous). Sensitivity analyses assessed the effects of limiting the study population to age 60 to 69 years and of removing nonsignificant variables from multivariable models. Statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 3.5.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing), with a significance level of 2-sided P = .05.

Results

The cohort included 45 834 veterans (mean [SD] age, 62.7 [3.8] years), of whom 14 310 (31%) were non-Hispanic Black men and 31 524 (69%) were non-Hispanic White men (Table 1). Median follow-up was 77 months (IQR, 41-111 months). At diagnosis, compared with White men, Black men were younger (mean [SD] age, 61.8 [3.9] years vs 63.1 [3.8] years; P = .001) and had slightly higher PSA levels (mean [SD] PSA level, 15.1 [21.0] ng/mL vs 13.0 [19.3] ng/mL [to convert to μg/L, multiply by 1.0]; P = .001) but were not more likely to have regional or metastatic disease. Screening frequency was similar between Black and White men. In total, 2465 men (5.4%) died of prostate cancer and 2007 (4.4%) died of other causes.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Patients.

| Variable | Patientsa | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 45 834) | Non-Hispanic White men (n = 31 524) | Non-Hispanic Black men (n = 14 310) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.7 (3.8) | 63.1 (3.8) | 61.8 (3.9) | .001 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 2004-2008 | 15 273 (33.3) | 10 966 (34.8) | 4307 (30.1) | .001 |

| 2009-2012 | 15 686 (34.2) | 10 791 (34.2) | 4895 (34.2) | |

| 2013-2017 | 14 875 (32.5) | 9767 (31.0) | 5108 (35.7) | |

| T categoryc | ||||

| T1 | 30 105 (65.7) | 19 729 (62.6) | 10 376 (72.5) | .001 |

| T2 | 14 150 (30.8) | 10 643 (33.8) | 3462 (24.2) | |

| T3 | 1194 (2.6) | 870 (2.8) | 324 (2.3) | |

| T4 | 430 (0.9) | 282 (0.9) | 146 (1.0) | |

| N categoryc | ||||

| N0 | 44 879 (97.9) | 30 865 (97.9) | 14 014 (97.9) | .86 |

| ≥N1 | 955 (2.1) | 655 (2.1) | 296 (2.1) | |

| M categoryc | ||||

| M0 | 43 915 (96.4) | 30 270 (96.5) | 13 645 (96.2) | .21 |

| M1 | 1657 (3.6) | 1111 (3.5) | 546 (3.8) | |

| Gleason scored | ||||

| ≤6 | 4451 (13.9) | 3244 (14.7) | 1207 (12.2) | .001 |

| 7 | 18 350 (57.4) | 12 472 (56.5) | 5878 (59.2) | |

| 8 | 4049 (12.7) | 2678 (12.1) | 1371 (13.8) | |

| ≥9 | 3510 (10.9) | 2240 (11.0) | 1090 (11.1) | |

| Unknown | 1624 (5.1) | 1245 (5.6) | 379 (3.8) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index scoree | ||||

| 0 | 19 858 (43.3) | 13 616 (43.2) | 6242 (43.6) | .001 |

| 1 | 5137 (11.2) | 3381 (10.7) | 1756 (12.3) | |

| ≥2 | 20 839 (45.5) | 14 527 (46.1) | 6312 (44.1) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 11 292 (24.7) | 8232 (26.1) | 3060 (21.4) | .001 |

| Unemployed | 34 496 (75.3) | 23 258 (73.9) | 11 238 (78.6) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 23 686 (51.7) | 14 895 (47.3) | 8791 (61.4) | .001 |

| Married | 22 143 (48.3) | 16 624 (52.7) | 5519 (38.6) | |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Yes | 29 243 (63.8) | 20 235 (64.2) | 9008 (62.9) | .001 |

| No | 11 022 (24.0) | 7593 (24.1) | 3429 (24.0) | |

| Unknown | 5569 (12.2) | 3696 (11.7) | 1873 (13.1) | |

| Agent Orange exposure | ||||

| Yes | 11 627 (25.4) | 8923 (28.3) | 2704 (18.9) | .001 |

| No | 33 245 (72.5) | 21 846 (69.3) | 11 399 (79.7) | |

| Unknown | 962 (2.1) | 755 (2.4) | 207 (1.4) | |

| PSA screening rate | ||||

| None | 13 249 (28.9) | 9020 (28.6) | 4229 (29.6) | .06 |

| Some, y | ||||

| 1 | 6505 (14.2) | 4458 (14.1) | 2047 (14.3) | |

| 2 | 7028 (15.3) | 4687 (14.9) | 2341 (16.3) | |

| 3 | 7841 (17.1) | 5384 (17.1) | 2457 (17.2) | |

| 4 | 6757 (14.7) | 4867(15.4) | 1890 (13.2) | |

| Total | 28 131 (61.4) | 19 396 (61.5) | 8735 (61.0) | |

| Annual | 4454 (9.7) | 3108 (9.9) | 1346 (9.4) | |

| PCP visit rate, mean (SD), % | 67.9 (37.6) | 66.4 (37.9) | 70.8 (36.7) | .001 |

| PSA level at diagnosis, mean (SD), ng/mL | 13.7 (19.8) | 13.0 (19.3) | 15.1 (21.0) | .001 |

| Income, mean (SD), $f | 50 037 (18 730) | 52 394 (18 509) | 44 816 (18 151) | .001 |

| Bachelor’s degree, mean (SD), %f | 15.3 (7.4) | 16.2 (7.6) | 14.4 (7.0) | .001 |

Abbreviations: PCP, primary care practitioner; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA to μg/L, multiply by 1.0.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

P values were calculated using χ2 tests for multigroup categorical variables, 2-proportion z tests for proportional variables, and t tests for continuous variables.

According to American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria.

Higher score indicates greater risk of cancer progression and death.

Higher score indicates greater severity of comorbidity.

Estimated from US census data for the patient’s zip code.

On multivariable survival analysis, PSA screening rate as a continuous variable was associated with a significant reduction in risk of PCSM (subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR], 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.69; P = .001) (Table 2). The reduction in risk of PCSM associated with screening was similar among Black men (sHR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.41-0.76; P = .001) and White men (sHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46-0.75; P = .001). Multivariable analysis with nonsignificant variables removed from the model demonstrated similar findings (eTable 1 in the Supplement), as did a sensitivity analysis excluding patients younger than 60 years (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Full Model Outputs for Fine-Gray Competing Risk Regression With PCSM as the End Point and Death From Non−Prostate Cancer Causes as a Competing Event.

| Characteristic | sHR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-Hispanic White men | Non-Hispanic Black men | |

| PSA screening rate | 0.57 (0.47-0.69) | 0.58 (0.46-0.75) | 0.56 (0.41-0.76) |

| PCP visit rate | 0.97 (0.83-1.13) | 0.94 (0.77-1.14) | 1.03 (0.80-1.33) |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.02 (0.93-1.11) | NA | NA |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 1.02 (1.01-1.04) | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004-2008 | 2.70 (2.25-3.24) | 2.60 (2.07-3.25) | 2.95 (2.16-4.04) |

| 2009-2012 | 1.92 (1.59-2.30) | 1.93 (1.54-2.41) | 1.91 (1.39-2.62) |

| 2013-2017 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index scorea | |||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 1.14 (0.99-1.31) | 1.14 (0.97-1.35) | 1.15 (0.89-1.48) |

| ≥2 | 1.44 (1.33-1.57) | 1.36 (1.23-1.51) | 1.67 (1.43-1.96) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other or not employed | 1.17 (1.06-1.31) | 1.21 (1.07-1.37) | 1.08 (0.88-1.32) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other or not married | 1.24 (1.15-1.35) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) | 1.10 (0.95-1.29) |

| Bachelor’s degreeb | |||

| Top 50% | 0.88 (0.57-1.36) | 0.84 (0.48-1.48) | 1.03 (0.54-1.99) |

| Bottom 50% | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Median incomeb | |||

| Top 50% | 1.21 (0.79-1.85) | 1.31 (0.78-2.22) | 0.98 (0.54-1.96) |

| Bottom 50% | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Yes | 1.51 (1.37-1.68) | 1.52 (1.35-1.72) | 1.49 (1.23-1.79) |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Unknown | 1.11 (0.94-1.31) | 1.12 (0.92-1.38) | 1.07 (0.79-1.43) |

| Agent Orange exposure | |||

| Yes | 0.95 (0.87-1.05) | 0.97 (0.87-1.09) | 0.88 (0.73-1.06) |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Unknown | 1.00 (0.77-1.30) | 1.00 (0.74-1.35) | 1.04 (0.59-1.84) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PCP, primary care practitioner; PCSM, prostate cancer–specific mortality; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; sHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Higher score indicates greater severity of comorbidity.

Estimated from US census data for the patient’s zip code.

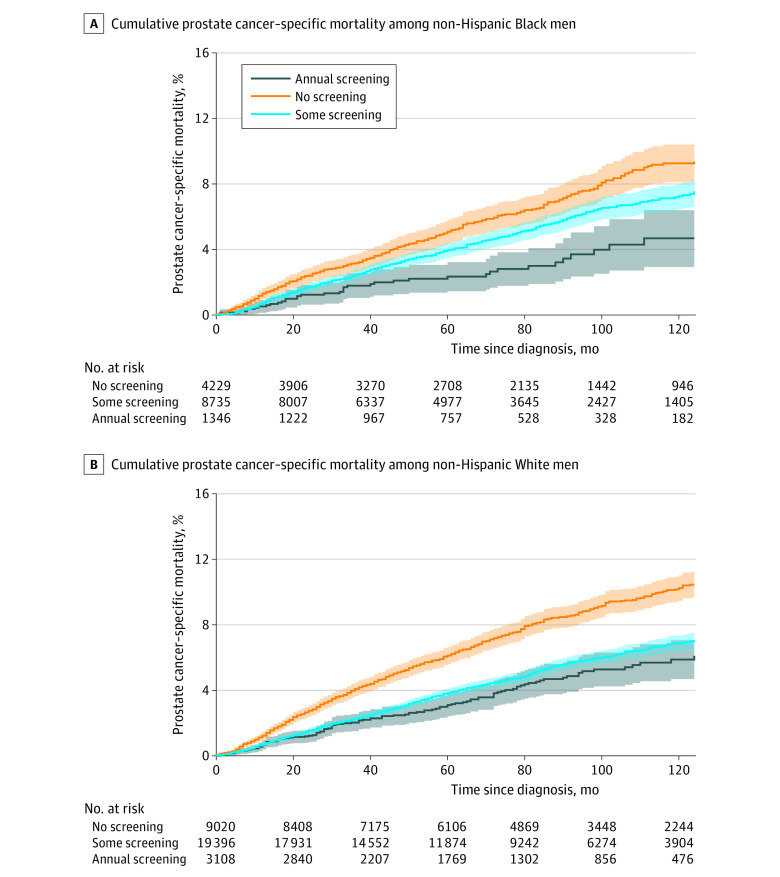

Cumulative incidence functions for PCSM with screening analyzed categorically revealed larger differences between some screening and annual screening among Black men (Figure, A) than among White men (Figure, B). At 120 months’ follow-up, the cumulative incidence of PCSM among Black men receiving annual screening was 4.7% (95% CI, 2.9%-6.4%) compared with 7.3% (95% CI, 6.5%-8.0%) among Black men receiving some screening (absolute difference, 2.6%). At this same time point, the cumulative incidence of PCSM among White men receiving annual screening was 5.9% (95% CI, 4.7%-7.0%) compared with 6.9% (95% CI, 6.4%-7.3%) among White men receiving some screening (absolute difference, 1.0%). On multivariable regression, annual screening (vs some screening) was associated with a significant reduction in risk of PCSM among Black men (sHR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46-0.92; P = .02) but not among White men (sHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.74-1.11; P = .35).

Figure. Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality Among Non-Hispanic Black Men and Non-Hispanic White Men.

Shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

In this cohort study of US veterans, PSA screening was associated with a reduction in risk of PCSM among non-Hispanic Black men and non-Hispanic White men, suggesting that PSA screening is at least as beneficial for Black men as it is for White men. Our results for White men are consistent with those of a pooled analysis of previous randomized clinical trials.10 However, those trials were conducted in predominantly White populations. Given that Black men are younger at diagnosis and have worse prostate cancer survival compared with White men,4 customized screening recommendations may be beneficial in this population.11 A study by some of us recently demonstrated that screening was associated with reduced PCSM among younger Black veterans (age 40-55 years).6 The present analysis suggests that these findings are also applicable to older Black men in a similar age range as those in the aforementioned screening trials.1,2,3

Furthermore, among Black men, annual screening was associated with reduced PCSM risk compared with some screening. Among White men, annual screening was not associated with reduced PCSM risk compared with some screening despite a similar distribution of screening frequency in the group that received some screening. Thus, Black men in particular may benefit from more intensive screening protocols. These results may be biologically plausible because a shorter screening interval may be valuable for detecting aggressive disease, which is more common in Black men.4,12 A recent model-based analysis also predicted benefit associated with increased screening frequency among Black men,5 and an investigation using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Medicare database suggested that frequent PSA screening was associated with reduced racial disparities in the risk of presentation with metastatic disease.13

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the large, racially diverse cohort with detailed records available, including laboratory PSA values. Many previous analyses have relied on self-reported PSA screening, the accuracy of which is limited and may vary with race.14

Limitations of our study include the use of retrospective data. Although we accounted for frequency of PCP visits as a measure of engagement with the health care system, there may be other unmeasured health care–seeking behaviors that confound the association between screening and lower PCSM. Our study excluded patients with very low– and low-risk disease because these patients are unlikely to die of prostate cancer and the goal of screening is to detect prostate cancers that require intervention. In addition, it may be difficult to generalize these results because of the differences in prostate cancer disparities and outcomes when comparing US Veterans Health Administration patients with the general US population.15

Conclusions

The results of this cohort study of US veterans demonstrated that previous PSA screening was associated with reduced risk of PCSM among both non-Hispanic Black men and non-Hispanic White men. Annual screening was associated with reduced PCSM risk among Black men but not among White men, suggesting that more intensive screening protocols may benefit Black patients. Further research is needed to identify appropriate protocols to maximize the benefits of PSA screening.

eTable 1. Full Model Outputs for Fine-Gray Competing Risk Regression With Nonsignificant Variables Removed From the Model

eTable 2. Full Model Outputs for Fine-Gray Competing Risk Regression for Patients Aged 60-69

References

- 1.Pinsky PF, Prorok PC, Yu K, et al. Extended mortality results for prostate cancer screening in the PLCO trial with median follow-up of 15 years. Cancer. 2017;123(4):592-599. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ; ERSPC Investigators . Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2027-2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. ; CAP Trial Group . Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: the CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(9):883-895. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahal BA, Gerke T, Awasthi S, et al. Prostate cancer racial disparities: a systematic review by the Prostate Cancer Foundation panel. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5(1):18-29. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyame YA, Gulati R, Heijnsdijk EAM, et al. The impact of intensifying prostate cancer screening in Black men: a model-based analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(10):1336-1342. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiao EM, Lynch JA, Lee KM, et al. Evaluating prostate-specific antigen screening for young African American men with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(4):592-599. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901-1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): prostate cancer. Version 3.2022. January 10, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://isotopia-global.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/NCCN-guidlines-prostate-cancer-2022.pdf

- 9.Draisma G, Boer R, Otto SJ, et al. Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(12):868-878. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsodikov A, Gulati R, Heijnsdijk EAM, et al. Reconciling the effects of screening on prostate cancer mortality in the ERSPC and PLCO trials. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):449-455. doi: 10.7326/M16-2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shenoy D, Packianathan S, Chen AM, Vijayakumar S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? BMC Urol. 2016;16(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0137-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahal BA, Alshalalfa M, Spratt DE, et al. Prostate cancer genomic-risk differences between African-American and White men across Gleason scores. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):1038-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taksler GB, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Explaining racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4280-4289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kensler KH, Pernar CH, Mahal BA, et al. Racial and ethnic variation in PSA testing and prostate cancer incidence following the 2012 USPSTF recommendation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):719-726. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic white men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1683-1690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Full Model Outputs for Fine-Gray Competing Risk Regression With Nonsignificant Variables Removed From the Model

eTable 2. Full Model Outputs for Fine-Gray Competing Risk Regression for Patients Aged 60-69