Abstract

Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that contains <10% murine protein. To prevent infusion-related hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs), the initial bevacizumab infusion is delivered for 90 min, the second for 60 min and subsequent doses for 30 min. Several previous studies have shown that short bevacizumab infusions are safe and do not result in severe HSRs in patients with colorectal, lung, ovarian and brain cancer. However, the efficacy of short bevacizumab infusions for colorectal cancer management remains unclear. Therefore, to investigate this issue, a prospective multicenter study was conducted using 23 patients enrolled between June 2017 and March 2019. The initial infusion of bevacizumab was for 30 min followed by a second infusion rate of 0.5 mg/kg/min (5 mg/kg over 10 min and 7.5 mg/kg over 15 min. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). The overall response and disease control rates were 57 and 87%, respectively. The median PFS time was 306 days (interquartile range, 204-743 days). No HSRs were noted. Adverse events associated with bevacizumab included grade 4 small intestinal perforation and grade 3 stroke in 1 patient each. These results suggest that a short bevacizumab infusion regime comprising an initial infusion for 30 min followed by a second infusion at 0.5 mg/kg/min is safe and efficacious for the management of colorectal cancer.

Keywords: bevacizumab, infusion, colorectal cancer, target therapy, PFS

Introduction

Clinical benefits are derived from agents that bind to circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key factor in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets VEGF-A, has been widely used for the treatment of a number of solid tumors, such as metastatic colon, non-small-cell lung, breast, brain and kidney cancer (1-3). Infusion of certain humanized monoclonal antibodies, such as rituximab and trastuzumab, results in infusion-related hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) (4). Bevacizumab contains <10% murine protein, which may also cause HSRs. Therefore, these antibodies are initially infused cautiously at a slower rate. To prevent HSRs, bevacizumab is initially infused for 90 min, with a second infusion for 60 min and subsequent infusions administered over a period of 30 min. Serious HSRs have not been reported in any major phase II or III trial (1,5,6). However, the standard dose of bevacizumab varies, for example, 5 or 7.5 mg/kg for colorectal cancer and 15 mg/kg for lung and brain cancer (7,8). Bevacizumab has been reported to be administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg for 90 min, followed by 5 mg/kg for 30 min at the same infusion rate of 0.166 mg/kg/min. Furthermore, bevacizumab administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg for 30 min has been infused at a rate of 0.5 mg/kg/min. This demonstrated that a high bevacizumab infusion rate of up to 0.5 mg/kg/min, which is three-fold higher than normal, is also safe and does not increase HSRs (2,3).

Standard bevacizumab infusions over 90, 60 and 30 min, which are widely used in the management of various cancer types, may be cumbersome and burden patients. Several studies have reported the use of short bevacizumab infusions in patients with colorectal cancer without any severe clinical HSRs (9-13). The safety of short infusions was also reported in the management of other types of cancer, such as lung, ovarian and breast cancer (9,14). Regarding other adverse effects, short bevacizumab infusions did not increase the risk of proteinuria and hypertension (9). Although the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines state that a bevacizumab infusion rate of 0.5 mg/kg/min is safe (15), short bevacizumab infusions have not been adopted in numerous countries owing to a lack of published safety and efficacy data. The present prospective, multicenter study was conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of short bevacizumab infusions in patients with colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Study protocol and patients

In this prospective study, patients with untreated, unresectable, advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer who had not previously received chemotherapy or bevacizumab were recruited between June 2017 and March 2019 from four hospitals (Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka; Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka; Machida Gastrointestinal Hospital, Osaka; and Osaka Ekisaikai Hospital, Osaka) in Japan. Inclusion criteria were as follows: An age of ≥20 years, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) score of 0, 1 or 2, and one or more measurable lesions assessed by an investigator according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumor (RECIST; version 1.1) guidelines (16). Exclusion criteria included the prior use of bevacizumab, brain metastasis and a history of bleeding or thrombosis. All patients received the first bevacizumab dose (5 or 7.5 mg/kg) for 30 min. If it was tolerated, the second bevacizumab infusion rate was 0.5 mg/kg/min (5 mg/kg over 10 min and 7.5 mg/kg over 15 min). No premedication was required prior to bevacizumab administration. It was essential to observe the patients for HSRs (pruritus, flushing, laryngeal edema and hypertension) at 10 and 30 min after treatment.

The primary study endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary endpoints were incidence of HSRs, toxicities associated with bevacizumab (proteinuria, hypertension, gastrointestinal perforations, arterial/venous thromboembolic events and bleeding) and overall response rate (RR). Tumor response was assessed by computed tomography according to the RECIST ver. 1.1 every 8 weeks. Adverse events were scored at each follow-up according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0) (17). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine (Osaka, Japan; protocol no. 3666). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Statistical analysis

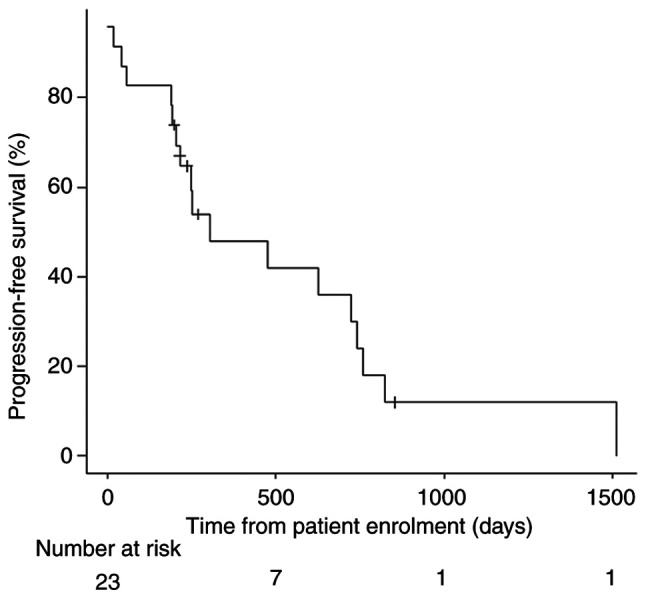

Continuous variables are presented as the median (range), and categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate the PFS curve. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (version 1.34; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University), which is a graphical user interface for R (version 3.3.2; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

A total of 23 patients (12 men and 11 women) were enrolled in the study, with a median age of 70 years (range, 44-80 years). Of these, 13 (57%) patients had an ECOG PS score of 0, and 10 (43%) patients had a PS score of 1. The primary tumor site included the right side, left side and rectal colon in 8 (35%), 6 (26%) and 9 (39%) patients, respectively. Regarding RAS mutation status, 7 (30%) and 16 (70%) patients had the RAS wild-type and the RAS mutant-type, respectively. A total of 18 (78%) patients had undergone primary tumor resection. Bevacizumab was administered with SOX (n=11; 48%), XELOX (n=9; 39%), FOLFOX (n=2; 9%) and FOLFOXIRI (n=1; 4%). Overall, 12 (52%) patients were on antihypertensive medication, and 1 (4%) patient had proteinuria. In total, 3 (13%) patients had a history of HSRs. Patient characteristics are shown in Table I. The median follow-up period after bevacizumab initiation was 751 days, and the median PFS time was 306 days (interquartile range, 204-743 days) (Fig. 1). The protocol treatment was discontinued owing to disease progression in 13 (57%) patients, toxicities unrelated to bevacizumab in 4 patients (17%; grade 1 pneumonitis, grade 2 palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome, grade 2 leukoencephalopathy and grade 2 malaise in 1 patient each), toxicities associated with bevacizumab in 2 patients (9%; grade 4 small intestinal perforation and grade 3 stroke in 1 patient each), a complete response in 2 patients (9%) and surgery in 1 (4%) patient. The treatment protocol was continued in 1 patient (data not shown). The responses to the protocol treatment were complete response, partial response, stable disease and progressive disease in 2 (9%), 11 (48%), 7 (30%) and 3 (13%) patients, respectively. The overall RR and disease control rate were 57 and 87%, respectively (Table II). No HSRs were reported in any of the 23 patients. A total of 6 (26%) patients developed proteinuria, of whom 3 exhibited grade 1 disease and 3 exhibited grade 2 disease. Hypertension was observed in 12 (52%) patients, of whom 3 (13%), 6 (26%) and 3 (13%) patients had grade 1, 2 and 3 disease, respectively. The adverse events associated with bevacizumab included grade 4 small intestinal perforation and grade 3 arterial/venous thromboembolic event (stroke) in 1 patient each (Table III). No treatment-related deaths occurred during the study period. After the failure of first-line chemotherapy, 17 patients received second-line chemotherapy. Consequently, 11 (65%) of these patients were treated with bevacizumab.

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 70 (44-80) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 12(52) |

| Female | 11(48) |

| Median weight (range), kg | 57 (41-76) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | |

| Yes | 12(52) |

| No | 11(48) |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1(4) |

| No | 22(96) |

| Hypersensitivity reactions, n (%) | |

| Yes | 3(13) |

| No | 20(87) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 13(57) |

| 1 | 10(43) |

| Primary tumor site, n (%) | |

| Right colon | 8(35) |

| Left colon | 6(26) |

| Rectum | 9(39) |

| Metastatic organs, n (%) | |

| Liver | 13(57) |

| Lung | 11(48) |

| Lymph node | 4(17) |

| Peritoneum | 4(17) |

| Number of metastatic organs, n (%) | |

| 1 | 13(57) |

| 2 | 8(35) |

| 3 | 2(9) |

| RAS mutation status, n (%) | |

| Wild-type | 7(30) |

| Mutant-type | 16(70) |

| Resection of primary tumor, n (%) | |

| Yes | 5(22) |

| No | 18(78) |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| SOX | 11(48) |

| CAPOX | 9(39) |

| FOLFOX | 2(9) |

| FOLFOXIRI | 1(4) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival. The protocol treatment was discontinued owing to disease progression in 13 (57%) patients and toxicities unassociated with bevacizumab in 4 (17%) patients (grade 1 pneumonitis in 1 patient and grade 2 palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome in 3 patients).

Table II.

Overall response.

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Complete response | 2(9) |

| Partial response | 11(48) |

| Stable disease | 7(30) |

| Progressive disease | 3(13) |

| Overall response rate | 13(57) |

| Disease control rate | 20(87) |

Table III.

Adverse events.

| Grade | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Hypersensitivity reaction, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | 3(13) | 3(13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3(13) | 6(26) | 3(13) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal perforations, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1(4) |

| Arterial/venous thromboembolic events, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1(4) | 0 (0) |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Discussion

The current prospective multicenter study investigated the safety and efficacy of short bevacizumab infusions in patients with colorectal cancer. The findings suggested that a shorter bevacizumab infusion was as effective as the standard infusion schedule and did not increase the risk of HSRs or associated severe adverse events. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of short bevacizumab infusions. The infusion duration affects the efficacy of certain drugs, such as 5-fluorouracil, as they have a short half-life. The >20-day half-life of bevacizumab, which implies that the infusion duration may not affect its efficacy, could explain the absence of reports correlating its efficacy and the infusion duration.

In the present study, the PFS time and RR was 306 days and 57%, respectively. Previous studies of oxaliplatin-containing regimens combined with bevacizumab showed a median PFS time of 9-10 months and an RR of 46-52% (1,5,6,18). The present study appears comparable to previous studies in terms of efficacy results. Besides HSRs, previous clinical studies have reported adverse events such as gastrointestinal perforation (0.3-2.0%) and stroke (0.3-5.0%) associated with bevacizumab infusion (1,5,6,18). In the present study, 1 patient (4%) had a grade 4 small intestinal perforation and another (4%) had a grade 3 stroke. Therefore, the results are comparable to those reported previously.

The incidence rates of severe proteinuria and hypertension were similar to those in other clinical studies (0.3-1.0% and 3.5-15%, respectively) (1,5,6,18). A higher incidence of all grade hypertension, comparable to that reported previously (22.4-43%) (1,5,6,18), was observed in the present study (52%). However, the previous studies failed to report the number of patients receiving active antihypertensive medication. In the present study, a relatively large number of patients (52%) had a history of hypertension. Therefore, they were considered to have elevated blood pressure.

Recently, bevacizumab has shown promise as an adjunct therapy that enhances the effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the management of non-small cell lung cancer (IMpower150 study) and renal cell cancer (IMmotion150 study) (19,20). In the field of colorectal cancer, phase II and III studies of bevacizumab plus immune checkpoint inhibitors plus cytotoxic chemotherapy have reported promising results (21-23). In future, the use of chemotherapy with bevacizumab is expected to increase, resulting in more infusions, and making short bevacizumab infusions increasingly important to reduce the infusion rate waiting times and increase patient convenience. Therefore, short bevacizumab infusions are meaningful.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a single-arm study, not a randomized controlled trial, and had a small sample size. Therefore, the conclusions of this study cannot be applied to clinical practice. However, being a prospective evaluation of the safety and efficacy of the approach in a multicenter setting, this study reflects real-world clinical practice. Second, PFS was used as the primary endpoint. In general, overall survival (OS) is used to show efficacy in clinical trials and PFS is used as a surrogate endpoint for OS in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. However, when the sample size is small, PFS has been reported to be inadequate as a surrogate endpoint of OS, which also affects effectiveness. Thus, there is a likelihood of bias pertaining to PFS due to other confounding factors (24). Finally, anti-epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors plus cytotoxic chemotherapy are used as first-line treatment for RAS wild-type left-sided colorectal cancer, as they are more effective than anti-VEGF inhibitors (25). The present study was conducted before this evidence was established. In the present study, 5 patients (22%) had RAS wild-type left-sided colorectal cancer. Additionally, BRAF mutation status was not evaluated in this study, as it was not required at that time.

In conclusion, the present results suggest that a short bevacizumab infusion involving an initial infusion for 30 min followed by infusion at a rate of 0.5 mg/kg/min is safe and efficacious. Short bevacizumab infusions are expected to improve the patient's satisfaction and the tolerability, and reduce the burden on healthcare providers. As the study sample size was too small, further studies with larger sample sizes are required to validate the safety and efficacy of short bevacizumab infusions in patients with colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

KT, AK and AN were responsible for the conceptualization of the study. KT, KA, SO, HM and TI performed the formal analysis. KT performed the investigation. Data curation was provided by KT, KA, SO, HM, TI, AK and AN. YNad, MO, SF, KO, SH, FT, NK were involved in the data analysis. KT wrote the original draft. KT, YNad, MO, SF, KO, SH, FT, NK, YNag and YF reviewed and edited the manuscript. KT, YNag and YF supervised the study. KT, FT and NK were responsible for project administration. FT, NK, YNag and YF confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine (Osaka, Japan; protocol no. 3666). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Ziger A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, Dickler M, Cobleigh M, Perez EA, Shenkier T, Cella D, Davidson NE. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dillman RO. Infusion reactions associated with the therapeutic use of monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;18:465–471. doi: 10.1023/a:1006341717398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabbinavar FF, Schulz J, McCleod M, Patel T, Hamm JT, Hecht JR, Mass R, Perrou B, Nelson B, Novotny WF. Addition of bevacizumab to bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3697–3705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): NCCN Guidelines Central Nervous System: Cancers. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cns.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): NCCN Guidelines Central Nervous System: Cancers. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah SR, Gressett Ussery SM, Dowell JE, Marley E, Liticker J, Arriaga Y, Verma U. Shorter bevacizumab infusions do not increase the incidence of proteinuria and hypertension. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:960–965. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terazawa T, Nishitani H, Kato K, Hashimoto H, Akiyoshi K, Iwasa S, Nakajima TE, Hamaguchi T, Yamada Y, Shimada Y. The feasibility of a short bevacizumab infusion in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:1053–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makris G, Kantzioura A, Beredima M, Karampola M, Emmanouilides C. Feasibility of rapid infusion of the initial dose of bevacizumab in patients with cancer. J BUON. 2015;20:923–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanmaz MT, Guner SI, Satılmıs B, Akyol H, Aydın MA. Thirty-minutes infusion rate is safe enough for bevacizumab; no need for initial prolong infusion. Med Oncol. 2014;31(276) doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reidy DL, Chung KY, Timoney JP, Park VJ, Hollywood E, Sklarin NT, Muller RJ, Saltz LB. Bevacizumab 5 mg/kg can be infused safely over 10 minutes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2691–2695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mir O, Alexandre J, Coriat R, Ropert S, Boudou-Rouquette P, Bui T, Chapron J, Durand JP, Dusser D, Goldwasser F. Safety of bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg infusion over 10 minutes in NSCLC patients. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1756–1760. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9690-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): NCCN Guidelines Central Nervous System: Cancers. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physicio_gls/pdf/colon.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0 https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fctep.cancer.gov%2Fprotocoldevelopment%2Felectronic_applications%2Fdocs%2FCTCAE_4.03.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamazaki K, Nagase M, Tamagawa H, Ueda S, Tamura T, Murata K, Eguchi Nakajima T, Baba E, Tsuda M, Moriwaki T, et al. Randomized phase III study of bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI and bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (WJOG4407G) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1539–1546. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Moro-Sibilot D, Thomas CA, Barlesi F, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2288–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Escudier B, Fong L, Joseph RW, Pal SK, Reeves JA, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2018;24:749–757. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniotti C, Borelli B, Rossini D, Pietrantonio F, Morano F, Salvatore L, Lonardi S, Marmorino F, Tamberi S, Corallo S, et al. AtezoTRIBE: A randomised phase II study of FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab alone or in combination with atezolizumab as initial therapy for patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(683) doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damato A, Bergamo F, Antonuzzo L, Nasti G, Iachetta F, Romagnani A, Gervasi E, Larocca M, Pinto C. FOLFOXIRI/Bevacizumab plus nivolumab as first-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer RAS/BRAF mutated: Safety run-in of phase II NIVACOR trial. Front Oncol. 2021;11(766500) doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.766500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mettu NB, Ou FS, Zemla TJ, Halfdanarson TR, Lenz HJ, Breakstone RA, Boland PM, Crysler OV, Wu C, Nixon AB, et al. Assessment of capecitabine and bevacizumab with or without atezolizumab for the treatment of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(e2149040) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.49040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang PA, Bentzen SM, Chen EX, Siu LL. Surrogate end points for median overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: Literature-based analysis from 39 randomized controlled trials of first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4562–4568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aljehani MA, Morgan JW, Guthrie LA, Jabo B, Ramadan M, Bahjri K, Lum SS, Selleck M, Reeves ME, Garberoglio C, Senthil M. Association of primary tumor site with mortality in patients receiving bevacizumab and cetuximab for metastatic colorectal cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:60–67. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.