Abstract

Objective

To analyze the influence of mechanical power and its components on mechanical ventilation for patients infected with SARS-CoV-2; identify the values of the mechanical ventilation components and verify their correlations with each other and with the mechanical power and effects on the result of the Gattinoni-S and Giosa formulas.

Methods

This was an observational, longitudinal, analytical and quantitative study of respirator and mechanical power parameters in patients with SARS-CoV-2.

Results

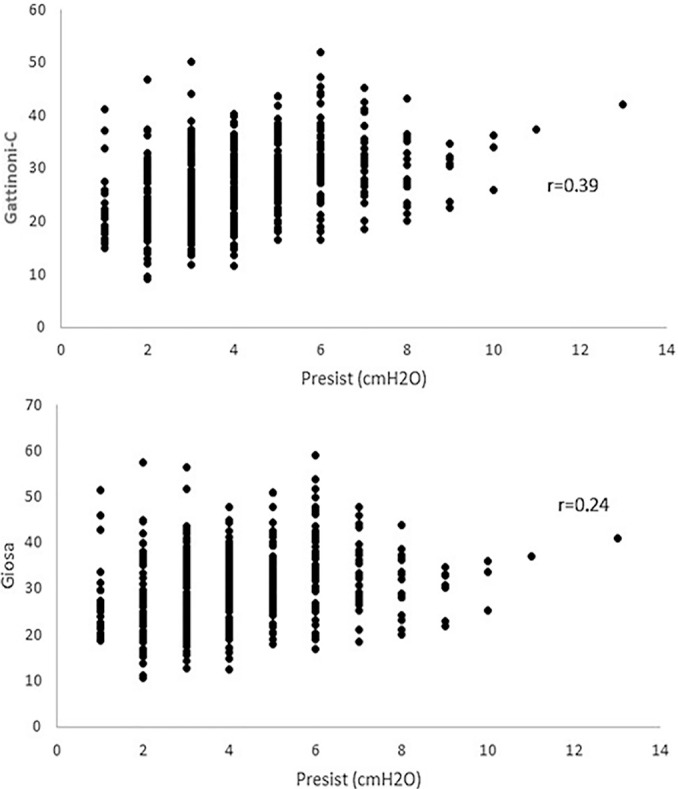

The mean mechanical power was 26.9J/minute (Gattinoni-S) and 30.3 J/minute (Giosa). The driving pressure was 14.4cmH2O, the plateau pressure was 26.5cmH2O, the positive end-expiratory pressure was 12.1cmH2O, the elastance was 40.6cmH2O/L, the tidal volume was 0.36L, and the respiratory rate was 32 breaths/minute. The correlation between the Gattinoni and Giosa formulas was 0.98, with a bias of -3.4J/minute and a difference in the correlation of the resistance pressure of 0.39 (Gattinoni) and 0.24 (Giosa). Among the components, the correlations between elastance and driving pressure (0.88), positive end-expiratory pressure (-0.54) and tidal volume (-0.44) stood out.

Conclusion

In the analysis of mechanical ventilation for patients with SARS-CoV-2, it was found that the correlations of its components with mechanical power influenced its high momentary values and and that the correlations of its components with each other influenced their behavior throughout the study period. Because they have specific effects on the Gatinnoni-S and Giosa formulas, the mechanical ventilation components influenced their calculations and caused divergence in the mechanical power values.

Keywords: Coronavirus infections, SARS-CoV-2, Lung injury, Respiration, artificial, Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Respiratory mechanics

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) can generate inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis. Consolidations and bilateral air bronchogram with peripheral distribution of ground-glass opacification in radiological examinations, acute hypoxemia, respiratory failure and a ratio of partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) less than 300mmHg suggest the diagnosis.(1) Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 often require high-energy mechanical ventilation (MV) in which the unfavorable prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) must be weighed.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome and VILI merge into a single and complex form, in which the individual contributions of lung injury are indistinguishable.(2)

There is no way to clinically separate the VILI resulting from the underlying process that causes ARDS, but its prediction is made with the progressive reduction of lung volume and unresponsiveness to positive endexpiratory pressure (PEEP) in addition to overcoming the reparative responses(3) that can determine an irreversible acute lung injury. No component of the isolated MV can be held responsible for the VILI, which results in MV configurations and a lung parenchyma condition related to its size, vascular pressure and heterogeneity.(4-6) In addition, VILI depends on the innate vulnerability of the lung tissues.(7) It would be interesting to determine the specific characteristics of VILI that each variable can cause.(8) Mechanical power is a physiological concept that simplifies the evaluation of MV, portraying it as encompassing the set of MV components(2-9) and the injury produced by the energy determined by the pressure gradient, which promotes alveolar deformation.(10) Composed of plateau pressure (Pplateau), driving pressure (∆P), PEEP, tidal volume (Vt), flow (F), resistance (R), elastance (Elast) and respiratory rate (RR),(11,12) mechanical power represents the energy transferred from the ventilator to the respiratory system(13) for a period of time in Joules per minute (J/minute).(9,14) The understanding of the biophysical causes of VILI changed the focus of concern of the inflation pattern of the current cycle strictly related to Vt and to the pressures to consider the energy exposures harmful to the lung by mechanical power.(3) The purpose of MV to rest the lungs is compromised when the mechanical strength of its components is inadequately used with increased mechanical power, as the chance of VILI occurring with worsening of the outcome increases.(9) The VILI is influenced by the three stress amplification mechanisms, which are the stress generated by the geometric asymmetry, the accentuation of the forces applied to the microelements by the viscoelastic drag of the flow and the progressive reduction of the microstructures that support the stress, with an increase in the cumulative load in the structures that remain intact.(15) The same load of energy supported without stress or harmful strain in a healthy lung can determine VILI in a “baby lung.”(3,16) The resolution of the injury that determines the alteration of pulmonary mechanics and sufficient tissue repair are necessary or the pulmonary irrecoverability is imminent.(3)

This study aimed to analyze the influence of mechanical power and its components on MV in SARS-CoV-2, identify the values of the MV components and verify their relevant correlations with each other and with mechanical power, in addition to their effects on the results of the Gattinoni-S and Giosa formulas.

METHODS

Longitudinal, observational, analytical and quantitative study of the data collected from the ventilator parameters of patients with SARS-CoV-2 and moderate ARDS admitted to a respiratory intensive care unit of a university hospital, reference in this care modality, from March 2021 to May 2021 in order to analyze the energy provided by the MV and the influence of its components. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Universidade Federal do Paraná, under opinion 4.571.036.

During the study period, 150 patients with SARS-CoV-2 and moderate ARDS who remained intubated in volumecontrolled ventilation with the Puritan Bennet™ 840 respirator and under deep sedoanalgesia and neuromuscular blocker, 510 bits of data were collected from the set of MV components to analyze and insert them into the mechanical power formulas.

The following were considered inclusion criteria for patients: World Health Organization (WHO) severity scale 6 or 7, PaO2/FiO2 between 100 and 200, chest radiography or tomography with bilateral opacities and D-dimers within the normal range with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for confirmed SARS-CoV-2.

We chose to collect data from the set of MV components every six days to capture the changes in respiratory mechanics and the behavior of the MV components over the length of time on MV as a result of SARS-CoV-2. The removal of the neuromuscular blocker or death determined the end of the collection.

Respiratory rate, Vt and peak pressure (Ppeak) were recorded, and the Pplateau was obtained by inspiratory pause. From these data, the minute volume (Ve), ∆P, resistance pressure (Presist), static compliance (C) and Elast were generated. The mechanical power was calculated using the formula of Gattinoni et al.(17) simplified (Gattinoni-S) (Equation 1) and the formula of Giosa et al.(18) (Equation 2).

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

These values and information were transcribed in an Excel® spreadsheet, and statistical analyses of the correlations between the components of MV and mechanical power were performed. Subsequently, the information found in articles published in the literature was discussed.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative variables were described considering the mean, median, minimum and maximum values, first and third quartiles and standard deviation. The comparison of the Gattinoni-S and Giosa formulas was performed using the Bland-Altman method. To evaluate the association of quantitative variables, the Pearson linear correlation coefficient was estimated. To evaluate the association of the variables of interest with the results of the methods evaluated, simple linear regression and multiple linear regression models were considered. Values of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States) and Stata/SE 14.1 (Stata Corp LP, United States) processing systems were used.

RESULTS

The length of stay of patients included in the study ranged from 8 to 54 days, with a mean of 22 days. During follow-up, of the 150 patients with SARS-CoV-2 and moderate ARDS, 96 died for a mortality rate of 64%.

Among the evaluations of the remaining 510 subjects, the mean ∆P, Pplateau and PEEP were 14.4 cmH2O, 26.5cmH2O and 12.1cmH2O, respectively. The mean Vt was 0.36L, the RR was 32 breaths/minute, and Elast was 40.6cmH2O/L. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the results obtained in the study.

Table 1.

Results of the mechanical ventilation and mechanical power components

| Variables | n | Mean | Minimum | 1st quartile | Median | 3rd quartile | Maximum | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow (L/minute) | 510 | 53.1 | 24.0 | 48.0 | 53.0 | 58.0 | 81.0 | 8.5 |

| Static compliance (L/cmH2O) | 510 | 0.028 | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.034 | 0.064 | 0.009 |

| Vt (L) | 510 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.06 |

| Ve (L/minute) | 510 | 11.6 | 6.0 | 10.2 | 11.6 | 13.0 | 18.9 | 2.2 |

| RR (L/minute) | 510 | 32.0 | 16.0 | 30.0 | 33.0 | 35.0 | 43.0 | 3.6 |

| Ppeak (cmH2O) | 510 | 30.6 | 18.0 | 27.0 | 30.0 | 33.0 | 47.0 | 4.7 |

| ∆insp (cmH2O) | 510 | 18.5 | 7.0 | 15.0 | 17.5 | 21.0 | 40.0 | 5.1 |

| ∆P (cmH2O) | 510 | 14.4 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 14.0 | 16.0 | 34.0 | 4.6 |

| Pplateau (cmH2O) | 510 | 26.5 | 16.0 | 24.0 | 26.0 | 29.0 | 41.0 | 4.1 |

| Presist (cmH2O) | 510 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 13.0 | 1.9 |

| PEEP (cmH2O) | 510 | 12.1 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 14.0 | 24.0 | 3.9 |

| Elastance (cmH2O/L) | 510 | 40.6 | 15.6 | 29.6 | 37.5 | 48.0 | 109.7 | 15.2 |

| Resistance (cmH2O/L/minute) | 510 | 0.079 | 0.014 | 0.055 | 0.074 | 0.100 | 0.243 | 0.038 |

| Gattinoni-S (J/minute) | 510 | 26.9 | 9.1 | 21.2 | 26.5 | 31.7 | 51.9 | 7.4 |

| Giosa (J/minute) | 510 | 30.3 | 10.7 | 24.0 | 29.6 | 36.1 | 58.9 | 8.3 |

Vt - tidal volume; Ve - minute volume; RR - respiratory rate; Ppeak - peak pressure; ∆insp - variation in inspiratory pressure; ∆P - driving pressure; Pplateau - plateau pressure; Presist - resistance pressure; PEEP - positive end-expiratory pressure.

The mean mechanical power was 26.9J/minute for the Gattinoni-S formula and 30.3J/minute for the Giosa formula.

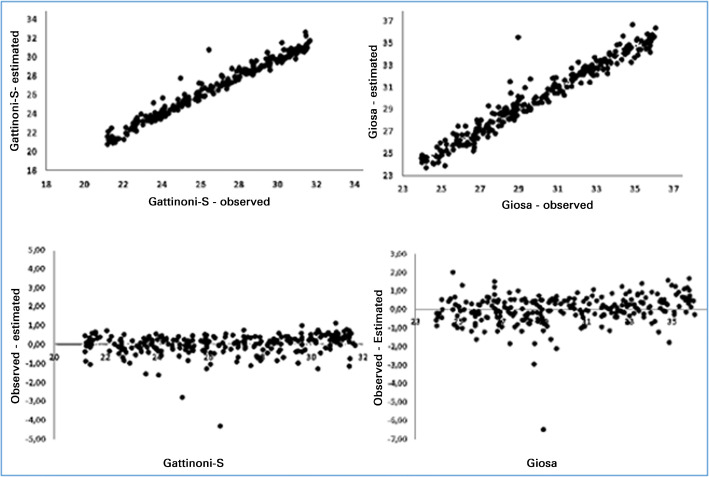

To prove the reliability of the results, the hypothesis of the absence of a linear association was tested versus the hypothesis of the existence of a linear correlation between the formulas. The bias is shown in the Brand-Altman graph shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Correlation and bias between Gattinoni-S and Giosa.

The dispersion diagram shows a strong positive correlation of 0.98 (p < 0.001) between the results of the two formulas, but there was a predominance of higher values with Giosa. The magnitude of the difference between the results depended on the Gattinoni-S value, with an average bias of -3.4J/minute, which was approached when values were low, but as the values increased, the difference between the results of the two formulas increased.

The greatest difference between the results was a value of Giosa 10.62 J/minute higher than the Gattinoni-S value, and in the largest differences, there was a high Vt, between 0.48L and 0.56L, and a low Presist, with a maximum of 2cmH2O. Ten evaluations showed that the value of Gattinoni-S was higher than the value of Giosa, and in all situations, high Presist was found between 8 and 13cmH2O, and in these cases, the largest difference was 1.08J/minute.

To understand the influence of the components on the mechanical power result and the trend of variation of the results between the formulas, the MV components were separately correlated with the results obtained from the formulas, as shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation between mechanical ventilation components and mechanical power

| Variables | Gattinoni-S | Giosa |

|---|---|---|

| ∆P | 0.14 (0.001) | 0.14 (0.002) |

| Pplateau | 0.61(< 0.001) | 0.58 (< 0.001) |

| Presist | 0.39 (< 0.001) | 0.24 (< 0.001) |

| PEEP | 0.47 (< 0.001) | 0.44 (< 0.001) |

| Elastance | -0.16 (< 0.001) | -0.20 (< 0.001) |

| Vt | 0.61 (< 0.001) | 0.68 (< 0.001) |

| RR | 0.39 (< 0.001) | 0.40 (< 0.001) |

∆P - driving pressure; Pplateau - plateau pressure; Presist - resistance pressure; PEEP - positive end-expiratory pressure; Vt - tidal volume; RR - respiratory rate.

The Pplateau, PEEP, Vt and RR demonstrated a moderate positive correlation, while ∆P had a weak positive correlation. In contrast, the Elast was the only one that had a weak negative correlation with both formulas. The only component that showed a significant correlation difference was Presist, which had a moderate positive correlation with Gattinoni-S (0.39) and a weak positive correlation with Giosa (0.24), as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Dispersion diagram between the resistance pressure and formulas Presist - resistance pressure.

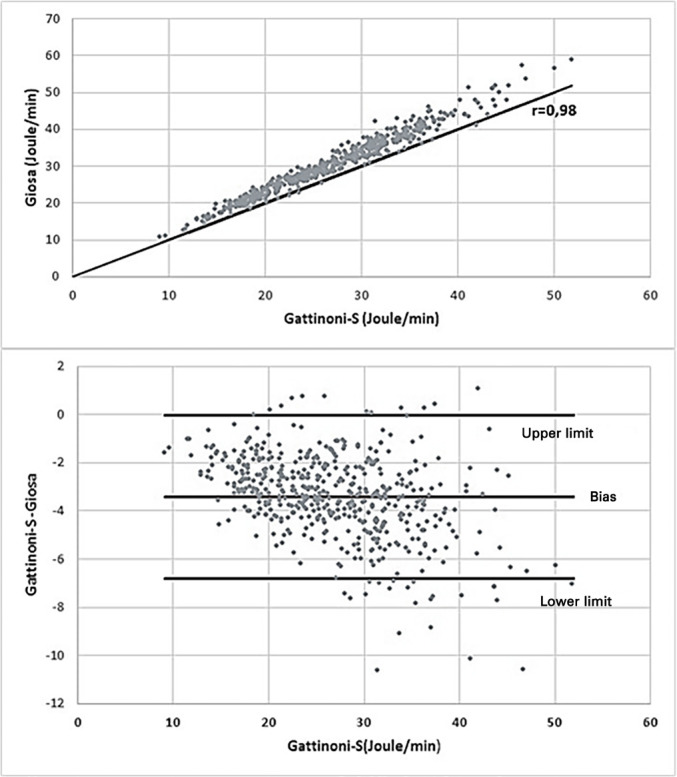

Table 3 shows the effects of the MV components on the mechanical power values based on the analysis of a multiple regression model. For this analysis, the combined effect of the covariates represented by the Pplateau, Presist, PEEP, Elast, Vt and RR was evaluated, while the two response variable models were the Gattinoni and Giosa formulas. Due to the strong correlation between ∆P and Elast (0.88), these two variables could not be included concomitantly in the models, and for the subsequent analyses, the Elast results were considered.

Table 3.

Effects of the mechanical ventilation components on the formulas

| Response variables | Explanatory variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pplateau (cmH2O) | Presist (cmH2O) | PEEP (cmH2O) | Elastance (cmH2O/L) | Vt (L) | RR (L/minute) | R2 (%) | |

| Gattinoni-S | 0.92 | 1.07 | 0.20 | -0.13 | 55.79 | 0.87 | 96.73 |

| Estimate | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.053 | 0.018 | 1.993 | 0.015 | |

| Standard error | |||||||

| Giosa | 0.95 | 0.60 | 0.15 | -0.14 | 70.40 | 1.03 | 94.54 |

| Estimate | 0.078 | 0.027 | 0.078 | 0.026 | 3.017 | 0.022 | |

| Standard error | |||||||

Pplateau - plateau pressure; Presist - resistance pressure; PEEP - positive end-expiratory pressure; Vt - tidal volume; RR - respiratory rate.

If the other components remained with fixed values, for each cmH2O increase in the Pplateau, an increase of 0.92 J/ minute was estimated in Gattinoni-S and 0.95J/minute in the results of Giosa. For each cmH2O increase in Presist, an increase of 1.07J/minute was estimated in the Gattinoni-S value and 0.60 J/minute in the Giosa results. For each cmH2O increase in PEEP, an increase of 0.20J/minute was estimated in Gattinoni-S units and 0.15J/minute in the results for Giosa. Each cmH2O/L increase in Elast estimated a reduction of 0.13J/minute in the value of Gattinoni-S and 0.14 J/minute of Giosa. For each unit of RR increase, an increase of 0.87J/minute was estimated in the value of Gattinoni-S and 1.03J/minute in Giosa, and for each 0.01L increase in Vt, there was an increase of 0.55J/minute in the Gattinoni-S value and 0.7 J/minute in the results for Giosa.

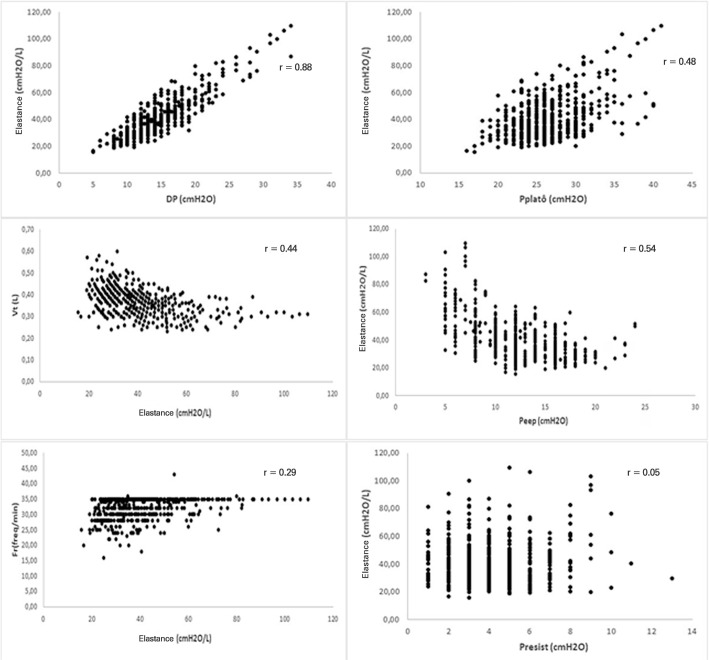

The models showed good adherence to Gattinoni-S and Giosa values between the first and third quartiles. Figure 3 shows the results of the estimates obtained in the range of 21.7 and 31.7J/minute for Gattinoni-S and 24 and 26.1J/ minute for Giosa.

Figure 3.

Correlations and differences between the estimated and observed results of the formulas

In the analysis of these results, greater influence was observed in the results with Vt; when it was high, the value of Giosa, and Presist increased, in turn generating an increase in the value of Gattinoni-S. The largest differences in the value of Giosa compared to Gattinoni-S resulted from high Vt with low Presist. Figure 4 shows the behavior of Elast and its correlation with the other components of MV. In the intercorrelations of the components with Elast, there was a strong positive correlation with ∆P (0.88), a moderate positive with Pplateau (0.48), a moderate negative with PEEP (-0.54) and with Vt (-0.44), a weak negative with RF and no correlation with Presist (0.05).

Figure 4.

Elastance dispersion diagram with the other components of mechanical ventilation

DP - driving pressure; Pplateau - plateau pressure; Vt - tidal volume; PEEP - positive end-expiratory pressure; Presist - resistance pressure.

DISCUSSION

The normalization of the mechanical power value as a safety limit for the prevention of VILI depends on lung volume and its distribution in pulmonary heterogeneity.(12,13) The safety thresholds of mechanical power vary for different pulmonary conditions because, in lungs affected by ARDS, the mechanical power values, capable of generating VILI, may be lower than in normal lungs.(9) However, the problem lies in establishing a specific mechanical power value expectation for each triggering factor of pulmonary insult. As normalization is related to the pulmonary condition, which is influenced over time by the evolution of ARDS and VILI, the recognition of these values could help determine the prognosis for patients with SARS-CoV-2.

The original equation allows quantifying the contribution of the components of MV and, in theory, could predict its effects on the lung parenchyma.

However, in clinical practice, the effects of its changes are not always predictable because it is necessary to modify other components to compensate for MV.(17) In this study, in the correlations between the variables, a trend of lower values of Vt and PEEP and higher values of Pplateau and ∆P, with the increase of Elast were observed.

Complex equations require obtaining ∆P, Elast and resistance, while simplified formulas facilitate medical practice with small value bias. The differences in values between the formulas occurred with low and high values due to the influence of the correlations of the components with the formulas and their effects on the results.(18) In this study, there was a tendency of the Giosa values to decline as the Gattinoni-S values increased, which was due to the differences in the effects of the specific components in each formula. In addition, the correlations of the components seem to represent the behavior of the MV components by pulmonary consequences during the course of SARS-COV-2, while the correlations of components with mechanical power seem to represent the need for energy current in relation to the pulmonary condition at a given time.

Divergent variations of mean values and limits of mechanical power were published, such as the mean of 9.1J/minute for normal lungs and 8.8J/minute for ARDS.(12) Another study reported variation in the severity of ARDS between 19 and 24 J/minute.(19) The question remained as to what is the threshold for producing VILI,(20) although it was suggested that mechanical power can cause VILI when it exceeds 12J/minute, and above 17J/minute, it is associated with increased mortality.(6) Even above 13J/ minute, it could cause serious damage.(21) In this study, an average mechanical power equal to 26.9J/minute was found for the Gattinoni-S formula, which is higher than the value of previous studies,(6,12,19,20,21) possibly because the sample is composed only of moderate ARDS generated by SARS-CoV-2.

Differences of up to 2J/minute were considered tolerable in the results of the simplified formulas of mechanical power compared to the geometric method, which is considered the gold standard and obtained by the area generated in the pressure-volume graph of the respirator.(22) In this analysis, the mean value of the results of the two simplified formulas showed a strong positive correlation, but with an average bias of -3.4J/minute and a prevalence of higher values for Giosa. As the Gattinoni-S values increase, the difference between the two formulas becomes more pronounced, a fact that is due to the difference in the specific effects of each MV component on their calculations.

It was shown that the effect of PEEP on the formulas is greater than that of Elast, and PEEP has a moderate positive correlation, while Elast denotes a weak negative correlation with mechanical power. In addition, the correlation of these two components of the MV is moderately negative. For example, the mixture of effects and intricate intercorrelations may result in a higher mechanical power when the lung responds with recruitment to PEEP than in the lung condition that indicates fibrosis of low response to PEEP recruitment and high Elast. This is due to the greater effect of PEEP on the calculation of mechanical power in relation to Elast and the tendency of the correlation between these components, which denotes a reduction in PEEP when Elast increases. The high mechanical power, regardless of the combination of its components, can cause VILI.(11) However, pointing to a single MV component with or without the determinant of VILI may be misleading, because it seems more reasonable that VILI is the result of a combination of the various MV components(8) and the interdependence between mechanical power and its components.(23) The question remains as to which of these factors most influences the advent of VILI.(7) It is indicated that isolated mechanical power values cannot provide definitive information on the prognosis of lung recovery capacity because they may represent the severity of ARDS but not that of VILI. Combining these analyses, it is assumed that an interrelation between the values of some MV components and mechanical power could expand the safety margin for VILI diagnosis. A mechanical power value greater than 17J/minute is considered a marker of increased mortality due to VILI,(6) and its worsening may be predicted by nonresponsiveness to PEEP and prone, with progressive reduction of lung volume, in addition to overcoming the opposite reactive responses, which culminate in irreversible acute lung injury.(3) In this study, mean values of mechanical power were found above this level, with a mortality rate of 64%, but it is not possible to state which deaths were determined by VILI or for other reasons.

CONCLUSION

In the analysis of mechanical ventilation for patients with SARS-CoV-2 infections, it was found that the correlations of its components with mechanical power influenced its high momentary values and that the correlations of its components with each other influenced their behavior throughout the study period. Because they have specific effects on the Gatinnoni-S and Giosa formulas, the mechanical ventilation components influenced their calculations and caused divergence in the mechanical power values.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Responsible editor: Irene Aragão

REFERENCES

- 1.Gibson PG, Qin L, Puah SH. COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): clinical features and differences from typical pre-COVID-19 ARDS. Med J Aust. 2020;213(2):54.e1–56.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasques F, Duscio E, Pasticci I, Romitti F, Vassalli F, Quintel M, et al. Is the mechanical power the final word on ventilator-induced lung injury?-we are not sure. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(19):395. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.08.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Time course of evolving ventilator-induced lung injury: the “Shrinking Baby Lung”. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(8):1203–1209. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marini JJ. Dissipation of energy during the respiratory cycle: conditional importance of ergotrauma to structural lung damage. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018;24(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes T, Enk D. Ventilation for low dissipated energy achieved using flow control during both inspiration and expiration. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2019;24:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coppola S, Caccioppola A, Froio S, Formenti P, De Giorgis V, Galanti V, et al. Effect of mechanical power on intensive care mortality in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02963-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marini JJ, Rocco PR. Which component of mechanical power is most important in causing VILI? Crit Care. 2020;24(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2747-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vassalli F, Pasticci I, Romitti F, Duscio E, Aßmann DJ, Grünhagen H, et al. Does iso-mechanical power lead to iso-lung damage? An experimental study in a porcine model. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(5):1126–1137. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi Y, He HW, Long Y. Progress of mechanical power in the intensive care unit. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(18):2197–2204. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saffaran S, Das A, Laffey JG, Hardman JG, Yehya N, Bates DG. Utility of driving pressure and mechanical power to guide protective ventilator settings in two cohorts of adult and pediatric patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a computational investigation. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(7):1001–1008. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serpa Neto A, Deliberato RO, Johnson AEW, Bos LD, Amorim P, Pereira SM, Cazati DC, Cordioli RL, Correa TD, Pollard TJ, Schettino GPP, Timenetsky KT, Celi LA, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M, Schultz MJ, PROVE Network Investigators Mechanical power of ventilation is associated with mortality in critically ill patients: an analysis of patients in two observational cohorts. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(11):1914–1922. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnal JM, Saoli M, Garnero A. Airway and transpulmonary driving pressures and mechanical powers selected by INTELLiVENT-ASV in passive, mechanically ventilated ICU patients. Heart Lung. 2020;49(4):427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gattinoni L, Marini JJ, Collino F, Maiolo G, Rapetti F, Tonetti T, et al. The future of mechanical ventilation: lessons from the present and the past. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1750-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Meijden S, Molenaar M, Somhorst P, Schoe A. Calcutating mechanical power for pressure-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(10):1495–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marini JJ. Evolving concepts for safer ventilation. Crit Care. 2019;23(Suppl 1):114. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva PL, Pelosi P, Rocco PR. Understanding the mysteries of mechanical power. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(5):949–950. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattinoni L, Tonetti T, Cressoni M, Cadringher P, Herrmann P, Moerer O, et al. Ventilator-related causes of lung injury: the mechanical power. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(10):1567–1575. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giosa L, Busana M, Pasticci I, Bonifazi M, Macrì MM, Romitti F, et al. Mechanical power at a glance: a simple surrogate for volume-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s40635-019-0276-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiolo G, Collino F, Vasques F, Rapetti F, Tonetti T, Romitti F, et al. Reclassifying acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(12):1586–1595. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201709-1804OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva PL, Ball L, Rocco PR, Pelosi P. Power to mechanical power to minimize ventilator-induced lung injury? Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(Suppl 1):38. doi: 10.1186/s40635-019-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collino F, Rapetti F, Vasques F, Maiolo G, Tonetti T, Romitti F, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure and mechanical power. Anesthesiology. 2019;130(1):119–130. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiumello D, Gotti M, Guanziroli M, Formenti P, Umbrello M, Pasticci I, et al. Bedside calculation of mechanical power during volume- and pressure-controlled mechanical ventilation. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):417. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03116-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marini JJ, Gattinoni L, Rocco PR. Estimating the damaging power of high-stress ventilation. Respir Care. 2020;65(7):1046–1052. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]