Abstract

Objective:

To capture the complete patient experience, knowledge and perceptions among women with stress urinary incontinence (SUI) by conducting a large-scale digital ethnographic analysis of anonymous online posts.

Methods:

Online posts were identified through data mining. First, 200 randomized posts were analyzed using grounded theory qualitative methods. To ensure full thematic discovery, we also applied a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) probabilistic topic modeling approach to the entire dataset of identified posts. LDA topics are represented as a distribution of words, similar to a “word cloud” which were manually reviewed to identify themes.

Results:

985 online posts by 762 unique users were extracted from 98 websites. There was significant overlap between the grounded theory and LDA identified themes. Our analysis suggests that these online communities help women manage the quality-of-life impact of their SUI, navigate specialty care, and reach a decision regarding surgical versus non-surgical management. Additionally, we identified risk factors, prevention strategies, and treatment recommendations discussed online.

Conclusions:

Findings demonstrated patient values that may influence decision making when seeking care for SUI and choosing a treatment. Social media interactions provide insight into patient behaviors that are important to improve patient-centered care and decision making.

Keywords: Female urology, stress urinary incontinence, grounded theory, health services research

II. INTRODUCTION

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is defined by the International Continence Society as the leakage of urine with physical exertion, cough, laugh, or sneeze.1 Information on the prevalence of SUI varies, with survey studies demonstrating a prevalence of 37%−42% among women in the United States and United Kingdom.2,3 SUI affects 4–14% of young and 12–35% of older women.4 Fultz et al. demonstrated that only 47% of women with moderately to extremely bothersome symptoms of SUI consulted a physician for their symptoms.5 Fear, shame, avoidance of social activities, lead to patient underreporting of SUI and hinder communication and shared-decision making with physicians.3,5–7 While the well-being and life quality associated with urge urinary incontinence (UUI), have been documented, there are fewer studies focusing on SUI.

Qualitative studies of SUI to date have focused on quality-of-life impact and SUI-treatment specific interviews. However, such studies were designed and guided by the researchers, rather than the direct perspective of patients.8–10 To capture a more complete experience of women with SUI, we applied a mixed methods approach using two forms of digital ethnography, a novel technique to examine the online behavior of individuals.11 Unlike traditional qualitative methods, social ethnography allows for analysis of anonymous, free-range, non-experimental conversations that may be generalized to the broader population of women coping with SUI. Specifically, digital ethnography is a method that involves adapting traditional ethnographic principles to analyze the cultural phenomena found in online spaces from the perspective of the population.12,13

Despite successful prior efforts in phenotyping lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) by the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction (LURN) Network, limited data exist that inform LUTS prevention interventions based on patient knowledge and behavior. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)-funded Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Network has adopted the social ecological model (SEM) as a framework for understanding the dynamic interactions among personal and environmental factors.12–16 With the goal of improving quality of care, shared-decision making and informing further prevention studies, we sought to determine the biopsychosocial experience, knowledge, and perceptions of women with SUI by performing digital ethnographic analysis of social media posts.

III. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Collection

This study was reviewed by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Institutional Review Board and was exempt from review. To identify relevant SUI-related online posts by women, we worked with Treato®, a social media data mining service that collected and analyzed patient content by providing website extraction templates that enabled our large-scale analysis. Researchers used a proprietary natural language processing algorithm-based lexicon of over 100,000 medical terms (using the unified medical language system) in order to index posts and search them in aggregate.17 Subject matter experts from our research team identified a set of keywords and exclusion criteria to extract relevant posts specific to women using Treato’s proprietary search algorithm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search and exclusion terms used in the Treato® algorithm.

| Stress (Urinary) Incontinence, SUI, Mixed urinary incontinence, and MUI |

Behavior modification: Kegels, Pelvic muscle exercises, Fluid restriction/reduction Surgical: Slings/ Mesh,Autologous fascial sling, Native tissue sling, Midurethral sling, Bladder neck sling, Tension-free vaginal tape, TVT , Urethral bulking agent, Periurethral injection therapy, Bladder lift, Collagen injection, Macroplastique, Coaptite Non-surgical: Uresta, Impressa, Incontinence pessary, Incontinence pads, Incontinence pull-ups, Diapers |

Excluded words: Dog, Cat, Baby, Babies, Child, Pet, Infant, Kid, Prostatectomy, Men, Posts by: companies, advertisements, doctors, urologists, offices, physical therapists, nurses |

Qualitative Methods: Traditional coding

Once posts were identified, we randomized the order of the posts and selected two hundred posts after excluding conversations that were in a non-English language, contained advertisement content, or mentioned male specific symptoms. We applied Grounded Theory methods, as described by Kathy Charmaz, to the two hundred posts.18 We chose this number to achieve a large enough sample of posts to achieve thematic saturation, in which themes begin to repeat and no new themes are generated with coding additional posts. Grounded Theory is hypothesis-generating and allows a researcher to find implicit theories in the data by coding and identifying categories.19 This method of analysis involved line-by-line coding of the posts with the purpose of identifying key phrases that are coded.19 Two investigators separately performed line-by-line coding. Similarly coded phrases were grouped into preliminary themes and subthemes, from which core categories, or emergent concepts are derived.

Mixed Quantitative/Qualitative Methods: LDA

In addition to our qualitative analysis, we performed quantitative analysis of all the posts identified by Treato using a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) probabilistic topic model. LDA was used to fit a model to the entirety of the data set of posts to explore themes within the collection in an unsupervised manner. LDA uses the contextual co-occurrence of words to find patterns of words that together represent a semantic concept. One way of thinking of a topic is through the familiar notion of a “word cloud,” where words that occur together frequently in the unit of analysis (e.g., social media posts), will be highly ranked in their corresponding topic. This allows for words to have multiple senses (e.g., the word “bank” could be associated with finance or nature), which reflects how language is used.11 The number of topics and the hyperparameters of the model are set manually, with the former typically increasing with the size of the corpus under analysis.

In LDA, documents are modeled as multinomial mixtures of topics, and thus it is the distribution over topics that characterizes what a document is about. Table 2 shows example topics with their respective prevalence in the collection and their assigned themes. The topics were ordered based on descending collection prevalence and manually reviewed by the entire research team who grouped them into themes and subthemes based on the interpretation of the topic’s associated word cloud. The designation of themes for a topic was then confirmed by reviewing posts, sorted by the topic’s prevalence, to ensure that language used in the posts accurately reflected the assigned themes. Although we utilized the quantitative signatures of posts in our LDA analysis, ultimately, we drew qualitative conclusions.

Table 2.

Example “word cloud” topics with their respective prevalence and assigned theme

| Birth, vaginal, giving, issues, totally, mild, term, damage, pregnancy, sex, childbirth, looked, especially, fun, progress, painful, information, regular, soon. | 7.8% | Childbirth risk factor |

| Pelvic, exercises, Incontinence, stress, muscles, Kegels, help, strengthen, recommend, leaking, physio, really, working, exercise, especially, childbirth, longer, pregnancy, urine, minutes. | 2.7% | Physical therapy, physical therapy after childbirth |

| Mesh, sling, complications, slings, suffering, experience, urinary, believe, concerns, removed, trust, resolve, damage, implant, inserted, offered, ugh, cut, urethra, infections. | 1.2% | Mesh complications, removal of mesh |

Incorporating LDA with traditional qualitative methods, allowed us to review all posts enabling theme discovery not apparent with grounded theory methodology that involves manual review limited by the number of posts identified. We were able to compare themes derived with each method to ensure consistency in capturing the breadth and depth of online posts.

IV. RESULTS

From our social media data mining, we identified 985 posts by 762 unique users collected from January 6, 2016 to December 5, 2018 from 98 different websites worldwide (Appendix 1).

Grounded Theory Analysis

We identified several preliminary themes with multiple subthemes related to the experience of women with SUI symptoms during data analysis using Grounded Theory (Table 3). One overarching theme centered on the interaction between patients and physicians. It appeared that women turned to online sources for further information after dismissive or frustrating medical encounters as described by online users. Their unsatisfying patient-physician interactions and lack of proper knowledge acquisition highlighted in the forums created a perceived sense of mismanagement and lack of trust. Additionally, women expressed frustration with access to proper specialty care and obtaining referrals for pelvic floor therapy.

Table 3.

Combined grounded theory and LDA themes with illustrative patient quotes from online posts.

| Themes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|

Patient-Physician Interaction

|

|

Prevention and Risk Factors

|

|

Non-Surgical vs. Surgical Management

|

|

Quality of lifes

|

|

Online Engagement

|

|

| Decision Making |

|

SUI prevention and risk factors was a second overarching theme found in posts that involved women’s rationale for why they experienced SUI. Based on the keyword content, it was evident that many women on the selected forums had not sought treatment for their SUI symptoms. Additionally, others attempted to learn about prevention and the etiology by detailing their own experiences and medical histories. The posts also identified numerous co-morbid pelvic floor conditions, including pelvic organ prolapse symptoms and surgical repair, history of a hysterectomy, prior vaginal deliveries, frequent urinary tract infections, diet and co-morbid associations such as obesity and diabetes. There was also an overlap with other gynecological discussions such as copper intrauterine devices, protracted labor, cervical length and endometriosis.

Another important theme identified was non-surgical management versus surgical management treatment considerations. Discussions about Kegel exercises concentrated on the use of pelvic floor exercises to prevent SUI and concerns about the appropriate timing of Kegels after a vaginal delivery. Women recommended self-starting Kegels prophylactically and as a management solution. Experiences and outcomes with treatment modalities such as bulking agents, Yoni device (intravaginal egg-shaped tool), “Mona Lisa laser,” and bladder training were discussed. Posts about surgical management primarily included information seeking and sharing about pre-operative logistical planning (scheduling and child care), post-operative logistics (recovery times with slings versus concomitant repairs, recurrent leaking, dyspareunia, bleeding, soreness), post-operative complications (recurrent urinary tract infections, trans-obturator tape sling-associated neuralgias and defecatory symptoms attributed to the sling). There were frequent recommendations to search for multiple opinions before getting non-native tissue repairs due to perceptions about mesh. Both positive and negative experiences with mesh were stated.

We also found a significant focus on the quality-of-life burden of SUI. Subthemes included the negative effect of SUI on intimate relationships and sexuality, as well as self-management with diapers and pads. A wide range of emotions included hope, depression, suicidality, frustration, embarrassment, worry, stress, anxiety, unhappiness, and low self-esteem. Women detailed leaking while being sexually intimate resulting in the avoidance of dating and sex. Self-management with pads and diapers was described in the context of embarrassment, fear of leakage, and hiding incontinence products.

Online engagement was another major theme with prominent subthemes surrounding symptom sharing, information seeking, and peer validation. Gratitude for the online community support, recommendations received, and symptom validation were consistently expressed. Decision making about reaching a surgical versus non-surgical resolution and seeking an initial medical consultation or further specialty care was also a major theme. Online users obtained information about treatment outcomes, surgical planning, and combined pelvic floor surgeries to reach conclusions.

LDA Topic Modeling Analysis

Every theme identified by Grounded Theory was also identified with LDA analysis. However, the word clouds lacked the detail found with our hand coding of posts. Nonetheless, the LDA methodology identified similar pelvic floor co-morbidities, with an additional focus on self-diagnosis, finding the etiology of SUI, and different concerns about surgical management. Lack of vaginal tightness appeared as a possible etiology of SUI. Concerns about the overlap of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) symptoms was identified. Additionally, the durability of surgery procedures and the concomitant repair of sector defects (cystocele and rectocele) with or without hysterectomy during SUI management was described. Overall, both methods of conducting digital ethnography included perspectives from women who not received medical care, women in the treatment decision process, and those sharing their knowledge of different treatment modalities.

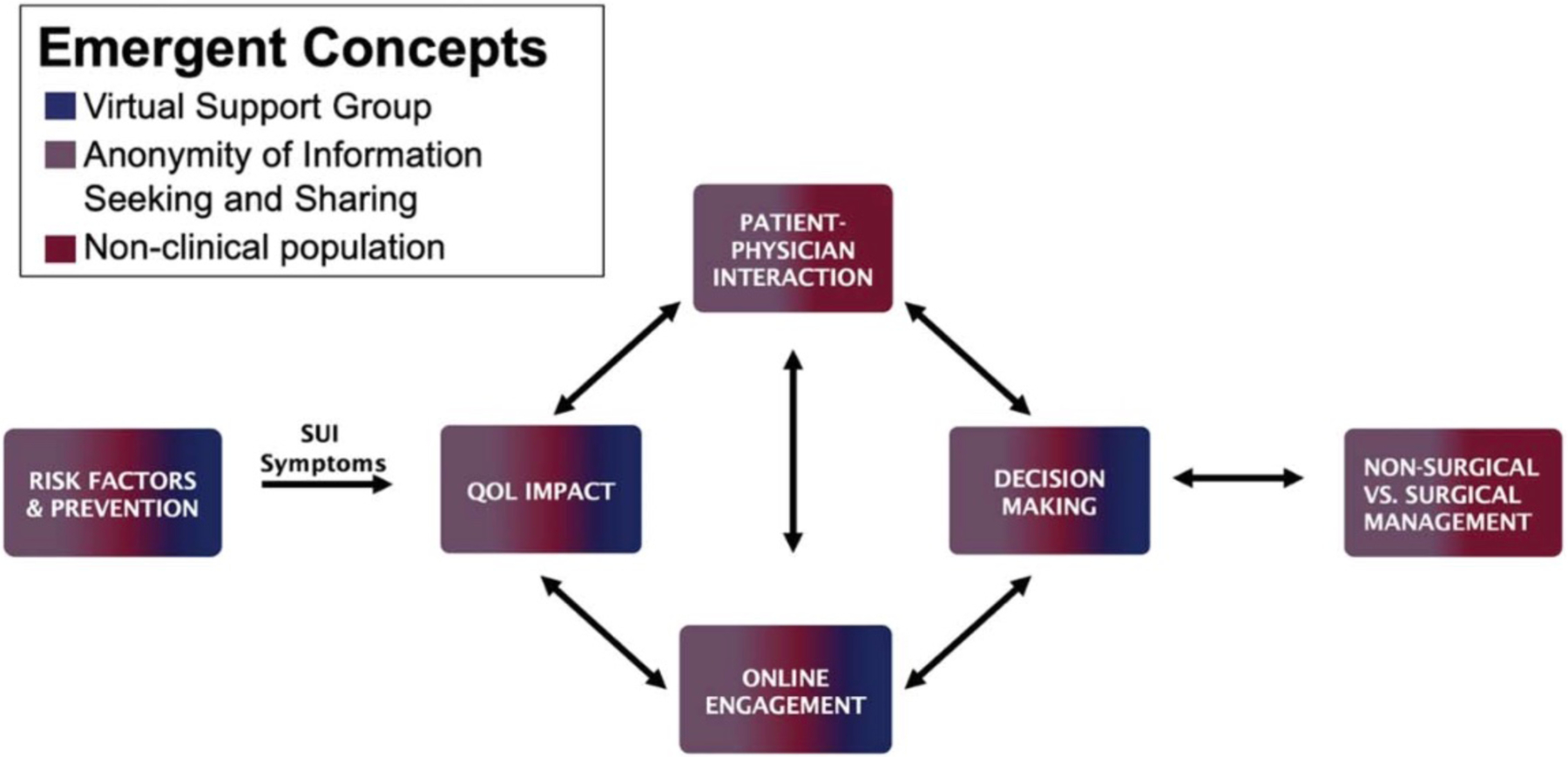

Emergent Concepts

Three emergent concepts arose from the six preliminary themes (Figure 1). First, online forums serve as a virtual support group to address knowledge gaps and receive recommendations. Second, it is clear that women are comfortable discussing their pelvic health on anonymous online platforms based on candid, descriptive posts. Third, our analysis identified new perspectives from people outside the clinical setting, providing information not identified with traditional qualitative methods to date.

Figure 1.

Conceptual thematic model demonstrating overlap among emergent concepts, combined grounded theory and LDA themes that influence treatment decision making.

The conceptual model (Figure 1) depicts the overlap of the emergent concepts among the combined grounded theory and LDA derived themes. The themes represent the viewpoint of a non-clinical population not found in current literature that can be further generalized. The anonymity of information seeking and sharing overlaps all of the identified themes, and it allowed for a patient-centered understanding of SUI. The virtual support group network supplements information provided by physicians and in some posts appeared to be the primary source of information about risk factors, etiologies, and healthcare navigating in the management of SUI.

IV. Discussion

Our study of women with SUI using digital ethnography identified the prominent concerns of the public. However, our results likely do not incorporate patients that are satisfied with their care. We described and analyzed themes about patient-physician interactions, prevention strategies, risk factors, social effects, and treatment choice among users. Our analysis revealed a variety of themes, knowledge, and lack thereof that can be leveraged to improve shared-decision making. Online posts served as both primary and secondary sources of information that influenced decision making between surgical and non-surgical management. Finally, our data indicate the utility of maximizing social media to engage and connect with women coping with SUI. Social media is integrated into people’s everyday lives and serves as a space for self-management, online engagement to support the illness experience, and the improvement of offline frustrations.20 The exchange of medical information via online forums allows users to customize their searches to acquire condition-specific knowledge lay referrals.20,21

The vast majority of literature focuses broadly on urinary incontinence and LUTS.10,22 SUI quality of life burden has been explored in prior qualitative studies using semi-structured patient interviews.9,10 The quality-of-life impact found in the current study is consistent with previous findings that SUI symptoms are associated with significant emotional impacts, even suicidality. Likewise, perceptions about recurrent SUI treatment options, after initial management failure, using semi-structured patient interviews have been documented in a European study.23 Unlike prior studies, we identified specific aspects of surgical planning and limitations at home that concern women. These prior interview-based studies have relied on recruiting women that have already established care for their SUI and reside in a specific geographic location. Despite the semi-structured interview methods, the limited flexibility of the interview may be a limiting factor.24 Additionally, the current study has the advantage of developing themes from a larger sample size and eliciting perspectives anonymously.

Interestingly, the use of an incontinence pessary for the management for urinary incontinence was not identified in the posts, which may be due to the younger demographics of users of social media and that older women are more likely to opt to use pessaries for treatment.25,26 Or, since incontinence pessaries are not very efficacious, perhaps they are offered less often by providers and hence not discussed on line. Additionally, less rigorously studied treatments such as the “yoni egg” device and “Mona Lisa” were frequently mentioned. Further studies of these treatments for SUI are needed, and it may benefit patients for physicians to discuss treatment modalities that appear on the internet.

The National Association for Continence, American Urological Association, and International Urogynecological Association websites have been rated among the best sources of SUI consumer health-related information.27 None of these websites were mentioned in our identified posts, which may suggest that it would benefit patients to incorporate forums onto these sites, address the relevant concerns identified in our analysis or direct patients appropriately.

While our study provided population-level insights, there are important limitations. As mentioned above, the choice of search terms for the social data mining process could have limited the number of identified posts. Also, patients were not involved in selection of terms, thereby we may have biased our results. Even though we removed terms that were related to male incontinence, such as prostate and prostatectomy, the content on the identified social media sites could nonetheless have included men. The anonymity of online discussions makes it challenging to identify demographic information and to determine if specific users post a large share of the discussions. Additionally, perspectives of individuals that do not have online access or choose not to use social media for medical-related purposes are, by default, excluded. Furthermore, the quality, accuracy, and content of all the websites are unknown. Regardless, these are the sources people are visiting for further information.

V. CONCLUSION

Digital ethnography revealed perspectives from treatment-naïve women, women navigating the treatment decision making process and those sharing their experiences with different treatment modalities. There also appears to be an access problem for women with SUI. The patient behaviors and values identified can be targeted to improve shared-decision making and inform further prevention interventions. The online presence of physicians and the improvement of online curated materials are important in meeting the population’s knowledge gaps. Before prevention of LUTS can be undertaken, it is critical to learn what people know and say about LUTS both inside and outside of the healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This study was funded by a pilot grant from the NIDDK Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium (JTA, BS).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Jennifer T. Anger is an expert witness for Boston Scientific

References

- 1.Haylen BT, De Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. : An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn 2010; 29: 4–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunskaar S, Lose G, Sykes D, et al. : The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int. 2004: 839–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lose G: The burden of stress urinary incontinence. Eur. Urol. Suppl 2005; 4: 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME, et al. : Urinary incontinence in women a review. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc 2017; 318: 1592–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fultz NH, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. : Burden of stress urinary incontinence for community-dwelling women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2003; 189: 1275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norton PA, MacDonald LD, Sedgwick PM, et al. : Distress and delay associated with urinary incontinence, frequency, and urgency in women. Bmj 2009; 297: 1187–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuelsson E, Victor A and Tibblin G: A population study of urinary incontinence and nocturia among women aged 20–59 years. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand 2008; 76: 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eves YD: A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. J. Adv. Nurs 2001; 35: 654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Cam C, et al. : Effects of urinary incontinence subtypes on women’s quality of life (including sexual life) and psychosocial state. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol 2014; 176: 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagg AR, Kendall S and Bunn F: Women’s experiences, beliefs and knowledge of urinary symptoms in the postpartum period and the perceptions of health professionals: A grounded theory study. Prim. Heal. Care Res. Dev 2017; 18: 448–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dzubur E, Khalil C, Almario CV., et al. : Patient Concerns and Perceptions Regarding Biologic Therapies in Ankylosing Spondylitis: Insights from a Large-Scale Survey of Social Media Platforms. Arthritis Care Res. 2019; 71: 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan-Trimmer S and Wood F: Ethnographic methods for process evaluations of complex health behaviour interventions. Trials 2016; 17: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia AC, Standlee AI, Bechkoff J, et al. : Ethnographic approaches to the internet and computer-mediated communication. J. Contemp. Ethnogr 2009; 38: 52–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyer K, Wallis AB and Hamberger LK: Neighborhood Environment and Intimate Partner Violence. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2013; 16: 16–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaren L and Hawe P: Ecological perspectives in health research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005; 59: 6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bavendam TG, Palmer MH, Brubaker L, et al. : The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium : Bladder Health and Preventing Lower Urinary Tract. 2018; 27: 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez B, Dailey F, Almario CV., et al. : Patient Understanding of the Risks and Benefits of Biologic Therapies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2017; 23: 1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: an explication and interpretation. In: Emerson RM, ed. Contemporary Filed Research. Boston, Ma: Little Brown; 1983:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser BG: Conceptualization: On Theory and Theorizing Using Grounded Theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017; 1: 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen C, Vassilev I, Kennedy A, et al. : Long-term condition self-management support in online communities: A meta-synthesis of qualitative papers. J. Med. Internet Res 2016; 18: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, et al. : Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res 2008; 18: 405–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breyer BN, Kenfield SA, Blaschko SD, et al. : The Association of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms, Depression and Suicidal Ideation: Data from the 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Urol 2014; 191: 1333–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tincello DG, Armstrong N, Hilton P, et al. : Surgery for recurrent stress urinary incontinence: the views of surgeons and women. Int. Urogynecol. J 2018; 29: 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser A and Korstjens I: Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract 2018; 24: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sitavarin S, Wattanayingcharoenchai R, Manonai J, et al. : The characteristics and satisfaction of the patients using vaginal pessaries. J. Med. Assoc. Thail 2009; 92: 744–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Sokol ER, et al. : Patient characteristics that are associated with continued pessary use versus surgery after 1 year. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2004; 191: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dueñas-Garcia OF, Kandadai P, Flynn MK, et al. : Patient-focused websites related to stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse: a DISCERN quality analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J 2015; 26: 875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.