II. INTRODUCTION

Pelvic floor disorders and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) including urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections, and pelvic organ prolapse, are increasingly common, with current estimates suggesting that up to 30% of women are affected.1,2 Despite this, the majority of women do not seek medical care for their conditions, with embarrassment and lack of knowledge of available treatments often cited as the primary reasons.3 Many patients turn to the Internet to find more information on their disease or symptoms, as it provides an anonymous avenue for women who may be too embarrassed to obtain health information in person.

Though the quality of online published information on pelvic floor disorders is varied, there has been little research on the health information portrayed on social media sites such as Facebook and Reddit.4 Unlike published websites which act as a one-way source of information, social media allows for ongoing conversation and shared content between users. More and more people, especially those over 65, are joining sites and posting their own content.5

Pelvic floor disorder patients have expressed a high desire to learn more about their conditions from social media sites.6 However, little is known about the quality of information available on social media, other than the fact that paid advertisements account for a large majority of content.7 We sought to evaluate the quality of information provided by actual users (rather than advertisers) as it relates to recommendation strategies for five common pelvic floor disorders. Given the varied quality of information about pelvic floor disorders online, we hypothesized that the quality of the recommendation strategies regarding disease prevention and treatment would be suboptimal and would not be in line with evidence-based recommendations.

III. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Collection

This study was deemed exempt by our institution’s IRB. Online posts related to stress urinary incontinence (SUI), pelvic organ prolapse (POP), urinary tract infection (UTI), overactive bladder (OAB), and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) were identified using Treato ®, a social media data mining company that collected and analyzed patient content from e-forums, blogs, and websites such as Healthcaremagic and Reddit.8 A natural language processing algorithm was utilized in order to index posts in the five aforementioned categories. Our research team identified a set of keywords and exclusion criteria to extract relevant posts specific to women (Appendix). Inclusion criteria consisted of a set of condition terms (for UTI, the terms “Bladder infection,” “Cystitis,” and “Pyelonephritis” were also included) and exclusion of posts with terms such as “dog”, “cat”, or “baby”. Data was collected from January 6, 2016 – August 5, 2018.

Two hundred random posts from each of the five categories (1000 total) were extracted from each data set to ensure thematic saturation based on our prior studies.8 Posts were excluded if they were not in the English language, had advertisement features, included male-specific descriptions, or were clearly not relevant to a pelvic floor disorder. Two separate investigators (CB, GG) conducted line-by-line analysis to identify recommendations for prevention or treatment. A given post could have multiple recommendations.

Analysis of Evidence

A PubMed search was conducted for relevant clinical guidelines for each of the five topics. Individual recommendation strategies from each post were compared to existing guidelines and given a level of evidence based on that guideline. If no guidelines were available, a PubMed search was conducted for systematic reviews. If no systematic review was available that addressed a specific recommendation strategy, a PubMed search for the specific strategy was conducted. Strategies were marked as having “no evidence” if no clinical guidelines, systematic reviews, or original research was identified for that recommendation, or if available research demonstrated no significant benefit. Levels of evidence were assigned based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (Table 1).9 Percentages were defined as the number of recommendations with a given level of evidence divided by the total number of recommendations on the topic.

Table 1:

Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence9

| 1a | Systematic review (with a homogeneity of RCTs) |

| 1b | Individual RCT with narrow confidence interval |

| 2a | Systematic review (with homogeneity of cohort studies) |

| 2b | Individual cohort study (including low quality RCT) |

| 2c | Outcomes research; Ecological studies |

| 3a | Systematic Review (with homogeneity of case-control studies) |

| 3b | Individual case-control study |

| 4 | Case-series (and poor-quality cohort and case-control studies) |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research, or “first principles” |

IV. RESULTS

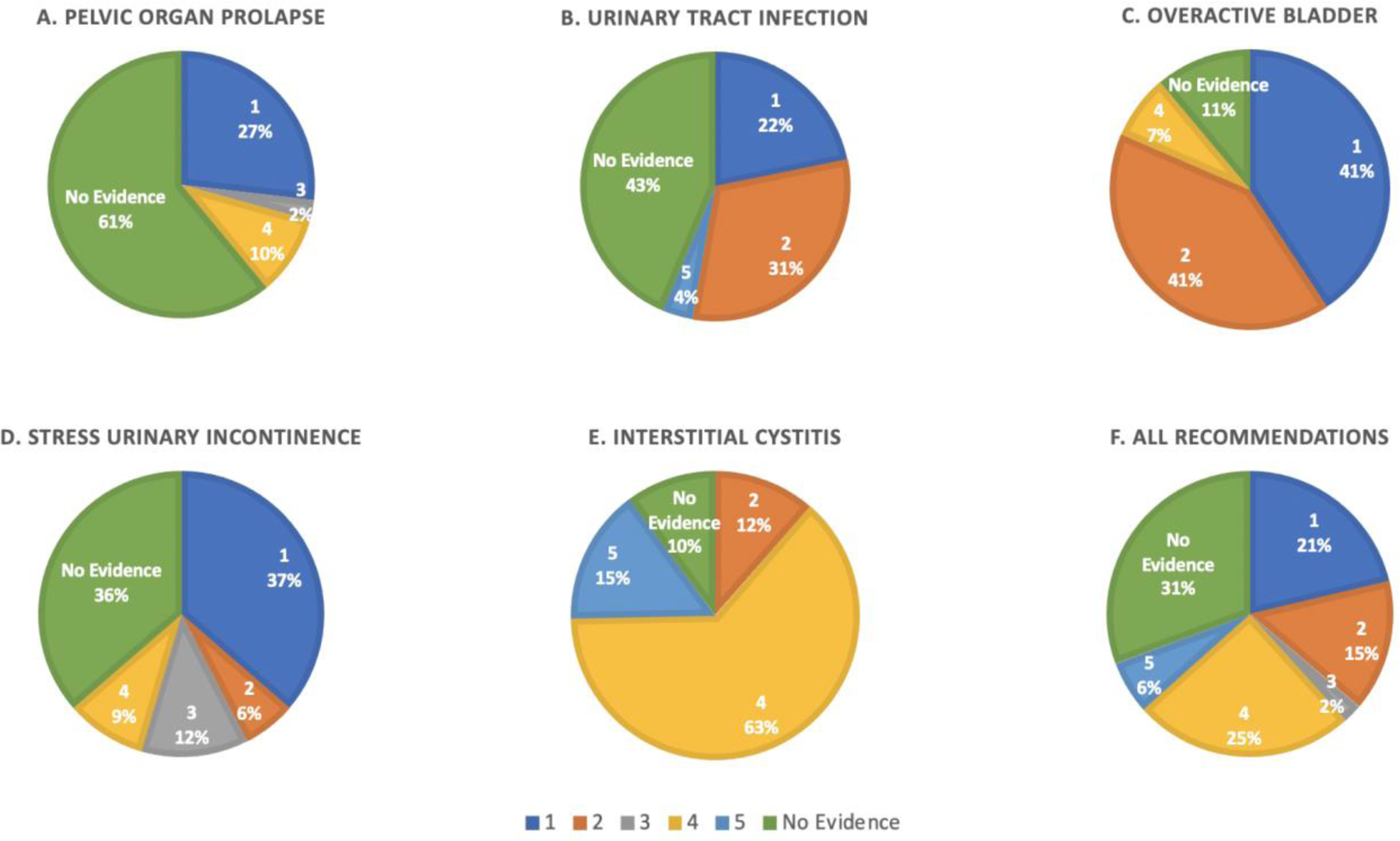

Of the 1,000 posts randomly selected to be reviewed, 158 posts contained 239 recommendations on disease prevention. Thirty-one percent (72/239) of those recommendations lacked any scientific evidence (Figure 1F).

Figure 1:

Percentage of recommendations by level of evidence for A) pelvic organ prolapse, B) urinary tract infection, C) overactive bladder, D) stress urinary incontinence, E) interstitial cystitis, F) all lower urinary tract recommendations combined

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Thirty-three of 200 posts contained 41 recommendations on prevention, 61% (26/41) of which had no evidence (Figure 1A), such as limiting physical activity, changing posture, breathing techniques, and topical honey (Table 2). Ten percent (4/41) also contained recommendations for using topical estrogen, for which limited data exist (level 4 evidence)10. Twenty-seven percent (11/41) of posts suggested pelvic floor muscle exercises or pelvic floor physical therapy to prevent or treatPOP, which has level 1 evidence.11

Table 2:

Categorization and examples of prevention recommendation strategies for pelvic floor disorders

| Disease | Prevention Strategy Recommendation | Representative Quotes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence-Based (n) | No Evidence (n) | |||

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse | • Kegel Exercises (5) • Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (6) • Avoid oophorectomy (1) • Topical Estrogen (4) |

1a11 1a11 3 22 410 |

• Whole Woman Solution (14) ◦ Posture ◦ “Jiggling” ◦ “Fire-breathing” • Topical Honey (1) • Limit Exercise (8) • Pessary (1) • Regular exercise (1) |

“….but I was so complacent about pelvic floor exercises and even the physio said that’s what lead to me having so many issues.” (Level 1a) “Running IS bad for prolapses!” (No evidence) “A profound uterine prolapse does require more than just good posture. You really need to commit to lots of firebreathing and jiggling of the organs forward, with the goal of keeping them forward for longer and longer periods as you stand upright.” (No evidence) |

| Urinary Tract Infection | • Increased fluid intake (11) • Vaginal Estrogen (1) • Cranberry Supplement (10) • Vitamin C (3) • D-Mannose (4) • Self-catheterization (2) |

1b19 1b12,23 2b12,24 2b25 2b24 513 |

• Avoid Ibuprofen (1) • Dietary Modification (10) ◦ Avoid alcohol, caffeine, citrus, & sugar ◦ Alkalinize urine ◦ Low pH diet ◦ Zinc • Hygiene (7) 12 • Timed Voiding (1) • Probiotics (4) • Cystex (1) |

“If you can get your mum to drink loads of fluids it will help. You may need to use a straw and keep topping up with fresh liquid every now and again” (Level 1) “Catheterizing saved my life too though. Before that, the bladder never emptied. Hence, the double back to the restroom in 10–15 minutes. That was the cause of infection back then.” (Level 5) “I wash every single time after pooping with some lather from an organic bar of soap with antibacterial properties.” (No evidence) |

| Overactive Bladder | • Kegel Exercises (2) • Decrease caffeine (9) • Decrease alcohol (2) • Decrease carbonated beverages (3) • Fluid restriction (3) • Timed voiding (3) • Bowel regimen (2) |

1b14 1b15 2c26 2b27 2b17 2b17 417 |

• Breathing techniques (1) • Magnesium Supplementation (1) • Avoid citrus (1) |

“Avoid coffee, tea, fizzy drinks, cocoa products and avoid constipation” (Level 1) “Belly breath [combos] need to be employed to alleviate the frequent urination. Only reverse kegel once the PF is no longer tense.” (No evidence) |

| Stress Urinary Incontinence | • Kegels (4) • PFMT (6) • Vaginal weights (2) • Weight loss (2) • Low impact exercise (4) • Pilates (3) |

114 114 114 214 314 414 |

• Bladder training (2) • Diet modification (5) ◦ ginger tea, nutmeg ◦ Avoid gluten, dairy, caffeine, and refined sugar • Laser rejuvenation (1) • Elective C-Section (1) • Posture (1) • Progesterone Cream (1) • Control Diabetes (1)28 |

“You do kegels to put you in the best position to avoid stress incontinence” (Level 1) “I would advise a second opinion or asking for a referral to a pelvic floor physiotherapist… I’m going again this time just to prevent any long term issues.” (Level 1) “Personally I would go for a c-section. The pregnancy itself is a risk factor (the urgency might get worse as your womb grows- relaxin loosens everything) but a c-section would limit the damage.” (No evidence) |

| Interstitial Cystitis / Bladder Pain Syndrome | • Avoid Kegels (2) • Pelvic floor therapy (7) • Dietary modification (47) ◦ Gluten free, celery juice, alkaline diet ◦ Avoid cranberry, carbonation, chocolate, acidic foods, dairy, red meat, sugar, mercury, citrus, alcohol, genetically modified organisms (GMOs) • Estrogen (3) • Hot baths / heating pads (2) • Ozone Gas (1) • Herbal supplements (9) ◦ Aloe Vera ◦ Pumpkin seed ◦ Oregano ◦ Marshmallow root |

2b18 2b18 418 429 518 530 518 |

• Avoid Zoloft (1) • Cannabinoids (1) • D mannose (1) • Hydration (1) • Avoid UTIs (1) • Antiparasitic cleanse (1) • MSM crystals (1) • Collagen hydrosylate (1) |

“Kegels at pelvic PT (for prolapse and incontinence) made my symptoms SO much worse...avoid these things” (Level 1) “Then, a few years ago was diagnosed with IC and began removing certain things from my diet that seemed to contribute and started taking Freeze Dried Aloe Vera tablets” (Level 5) “I have to make myself drink plenty of water and dehydration makes me ten times as bad” (No evidence) |

Urinary Tract Infections

There were 58 recommendations in 31 posts. Forty-three percent (24/58) had no evidence (Figure 1B), including recommendations for dietary modifications such as avoiding alcohol, caffeine, citrus, and sugar, urinary alkalization, avoidance of ibuprofen, and hygienic routines. Half (53%) of prevention recommendations had either level 1 (increased fluid intake, vaginal estrogen) or level 2 (cranberry supplement, Vitamin C, D mannose) evidence.12 Two posts (4%) recommended intermittent catheterization to improve bladder emptying, which is a level 5 recommendation.13

Overactive Bladder

With 27 recommendations in 17 posts, 41% (11/27) of recommendations had level 1 evidence, either recommending pelvic floor exercises or decreased caffeine intake (Figure 1C).14,15 Another 41% (11/27) of the recommendations were for reducing alcohol intake, decreasing fluid intake, and timed voiding (level 2).16,17 Eighteen percent of recommendations (3/27) had level 4 (decrease constipation), or no evidence (magnesium supplementation and breathing techniques).

Stress Urinary Incontinence

There were 33 recommendations in 30 posts, 36% (12/33) of which had prevention recommendations with low or no evidence including nutmeg supplementation, laser rejuvenation, bladder training, dietary modifications (avoiding caffeine, refined sugar, gluten, dairy), changing posture, and progesterone cream. Thirty-seven percent (12/33) recommended pelvic floor exercises, or vaginal weights (level 1), two posts recommended weight loss (level 2), and the remainder (7 posts) recommended low impact exercise or Pilates (level 3).

Interstitial Cystitis

For IC there were 79 recommendations in 46 posts. IC had the highest number of recommended prevention strategies of the five groups, and most were low (level 4 or 5) or no evidence (70/79, 89%) (Figure 1E). Ten percent (8/79) had no evidence at all, and included use of cannabinoids, collagen hydrosylate, marshmallow root, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) crystals, or D-mannose. The majority of recommendations (57/79, 72%), had low evidence (clinical principle) for a variety of recommendations on dietary modifications and herbal supplements.18 Eleven percent (9/79) recommended avoiding Kegel exercises or going to pelvic floor physical therapy (level 2).

Overall Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

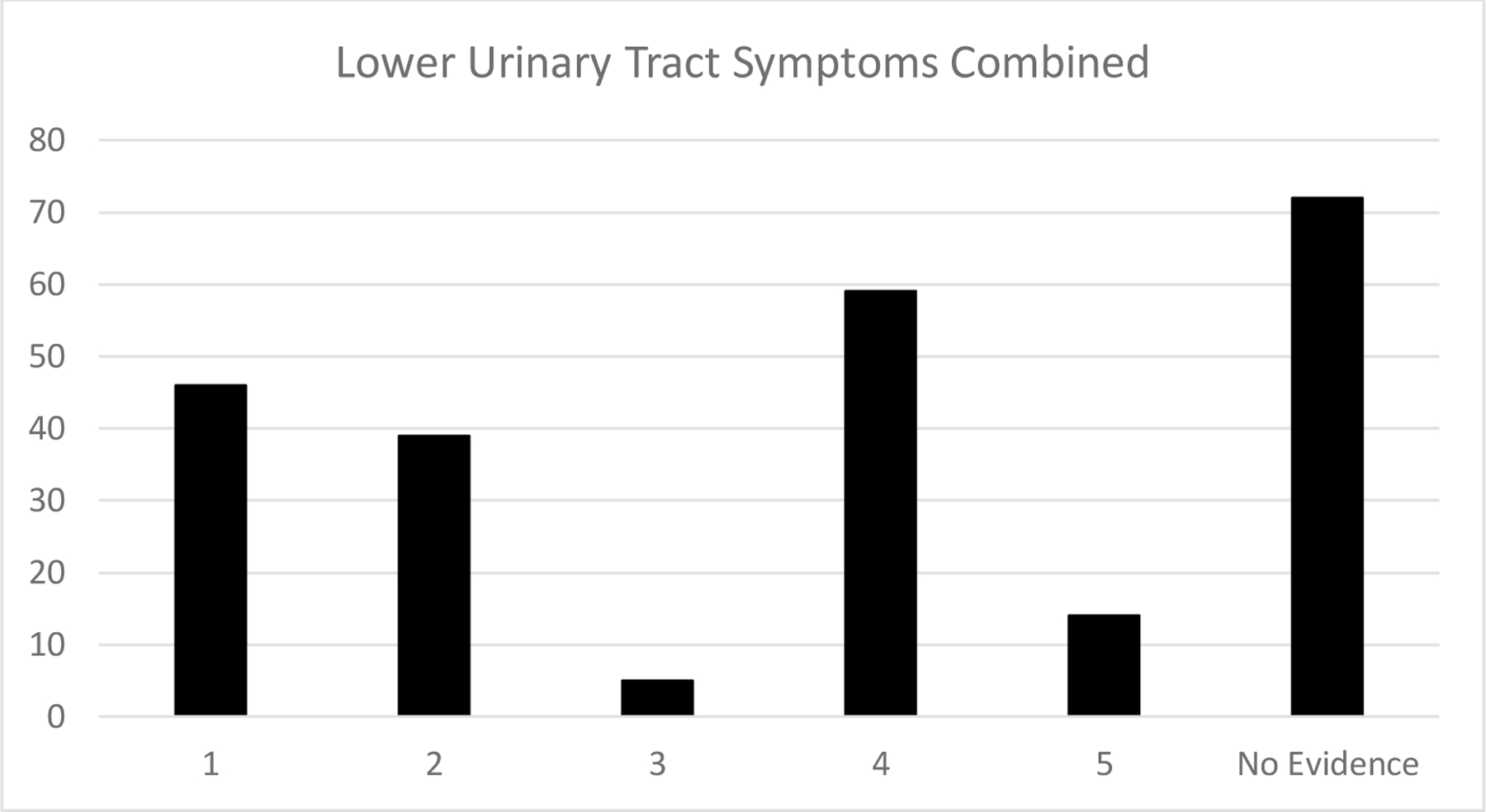

Overall there was no relationship between the content of the posts and the level of evidence (Figure 2). In addition, the frequency by which a prevention strategy was mentioned did not correlate with level of evidence. Approximately one third of the posts had level 1 or 2 evidence, one third of the posts had no evidence, and one third had level 3, 4, or 5.

Figure 2:

Total number of recommendation strategies by level of evidence for all five lower urinary tract symptoms combined

Identification of Author Credentials

The majority of posts with recommendations were identified as being the personal experience of the author (n=121, 76%). Twenty percent (n=32) of authors did not provide an form of identification or basis for their recommendations. Four percent (n=5) of authors identified themselves as a professional (physician (n=3), Pilates instructor, and weight lifting instructor).

V. DISCUSSION

In this analysis of the quality of prevention and treatment recommendations for pelvic floor disorders by users of social media sites, we found a wide sample of recommendations supported by varying levels of evidence. Almost one third of the posts lacked any scientific evidence at all and only 21% were backed by level I evidence.

Recommendations on prevention of UTIs were supported by the most evidence, largely driven by recommendations to increase fluid intake. This is possibly related to the recent press surrounding the publication by Hooton et al that demonstrated the benefits of increased water intake 19. Yet vaginal estrogen, one of the most effective means of preventing UTIs in peri- and post-menopausal women, was only mentioned once.12 Conversely, the recommendations for interstitial cystitis were supported by the least amount of evidence, primarily due to the fact that there is a dearth of quality research on strategies and mechanisms to prevent IC flares.18 Manual physical therapy has the strongest evidence for preventing IC flares, but this was only discussed in 11% of evaluated posts.18 The vast majority of posts recommended dietary modification and herbal supplementation, which are given “clinical principle” designation in the AUA Guideline.18

Similarly, pelvic floor muscle exercises are associated with improvements and prevention of stress urinary incontinence, but only one third of the evaluated posts recommended it. On the other hand, there were five recommendations for dietary modifications which have no evidence for prevention or treatment of SUI.

It is important to understand the information being propagated on social media, as a survey of patients in female pelvic medicine practices across the United States showed that women are interested in using social media for information about pelvic floor disorders.6 Additionally, investigation into the posts on social media can provide valuable insight into the patient experience, as was previously reported by Dr. Du et al in their analysis of urinary incontinence forums on Reddit.20 In our analysis we identified the concerning fact that there was no correlation with frequency of posts and evidence level, meaning that the propagation of recommendations occurs based on popularity of ideas rather than facts. As a medical community we should continue to educate our patients, engage in social media in a professional capacity, and correct misinformation in order to best serve our patients who look to the Internet for health information. This will require many providers to develop a social media presence across a variety of platforms with consistent and regular engagement so as to reach a wide array of women.

This analysis also demonstrates the desire among many women for natural or herbal remedies for many pelvic floor disorders, and particularly for IC. Unfortunately, few studies currently exist to examine the impact of these treatments on pelvic floor disorders. Further research evaluating the potential benefits of herbal supplements may help more clinicians effectively counsel patients on their benefit or lack thereof, and increase the quality of these recommendations that are at this point solely anecdotal in nature. We imagine that, the lower the evidence base for a given condition, the more that lay people will seek unfounded and outlandish treatments. Increasing the evidence base for or against treatment options will hopefully trickle down to recommendations on social media as well.

The majority of these posts represent the personal experience of those posting, though one fifth of the authors provided recommendations without any identifying information. While some of the perceived advantages of social media are the ability to share personal experiences and relate to other people with a given condition, there is a risk that those who provide recommendations may have other motivations such as financial gain. Many social media sites and health forums support anonymity, but perhaps health-related sites should encourage authors to identify their qualifications or specify if they are speaking from personal experience, so that other readers may more appropriately evaluate the quality of the source of recommendations.

While our study provides insights on the gap between the existing evidence-based prevention strategies and what is propagated on websites, there are several important limitations. It is possible that the 1000 posts randomly selected are not representative of social media posts as a whole, although our prior analysis of the SUI social media posts demonstrated significant thematic overlap between the same randomly selected subset and almost 1000 online posts.8 Additionally, the anonymity of the posts may limit the generalizability of these findings, as social media users tend to be younger and more educated than the general population.21 Finally, the data mining company used to obtain this data, ceased operations in August 2018 so while the opportunity for repeated searches or validation of methodology cannot be exactly replicated, other data mining tools exist for similar searches.

Despite these limitations, this study provides an important characterization of the types of prevention and treatment recommendations that exist on social media in regards to pelvic floor disorders. Unlike previous studies that have examined posts on a single platform such as Twitter or Reddit, we were able to analyze a variety of sites in order to capture a broader representation of social media posts. By comparing existing evidence for prevention and treatment recommendations with the recommendations on social media, we identified a gap between what is being recommended and what is supported by evidence. We hope this encourages physicians to continue to engage in patient education and social media outreach to promote treatments that are likely to be the most successful.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Many recommendations for prevention and treatment of pelvic floor disorders on social media lacked any scientific support, and numerous evidence-based strategies were not promoted. Clinicians should continue educating the public about pelvic floor disorders and lower urinary tract symptoms and promote prevention strategies that are likely to be successful. We should also continue to engage in high quality research to further the body of evidence regarding disease treatment and prevention, including research on the use of vitamins and supplements to meet the interests of our patients. In addition, we should discourage those strategies that lack evidence and could even be potentially harmful. Clinicians should continue to engage in social media outreach, as many women desire to obtain health information through social media sites.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Funded by a pilot grant from NIDDK Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium (JA, BS)

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: None

Disclosures: Dr. Jennifer T. Anger is an expert witness for Boston Scientific

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(1):141–148. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wilson D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;107(12):1460–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11669.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SHAW C, GUPTA RDAS, WILLIAMS KS, ASSASSA RP, MCGROTHER C. A survey of help-seeking and treatment provision in women with stress urinary incontinence. BJU Int 2006;97(4):752–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakos AB, Lovejoy DA, Whiteside JL. Quality of information on pelvic organ prolapse on the Internet. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26(4):551–555. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2538-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perrin A, Duggan M. Americans’ Internet Access: 2000–2015. Pew Res Cent 2015;June:1–12.

- 6.Mazloomdoost D, Kanter G, Chan RC, et al. Social networking and Internet use among pelvic floor patients: a multicenter survey. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(5):654.e1–654.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sajadi KP, Goldman HB. Social Networks Lack Useful Content for Incontinence. Urology 2011;78(4):764–767. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez G, Vaculik K, Khalil C, et al. Women’s Experience with Stress Urinary Incontinence: Insights from Social Media Analytics. J Urol December 2019. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine - Levels of Evidence (March 2009) - CEBM https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- 10.Weber MA, Kleijn MH, Langendam M, Limpens J, Heineman MJ, Roovers JP. Local Oestrogen for Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2015;10(9):e0136265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(12):CD003882. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003882.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anger J, Lee U, Ackerman AL, et al. Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol May 2019:101097JU0000000000000296. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000296 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Johansen TEB, et al. Guidelines on Urological Infections; 2015. https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- 14.Dumoulin C, Hunter KF, Moore K, et al. Conservative management for female urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse review 2013: Summary of the 5th International Consultation on Incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2016;35(1):15–20. doi: 10.1002/nau.22677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivera CK, Meriwether K, El-Nashar S, et al. Nonantimuscarinic treatment for overactive bladder: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(1):34–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson D, Hanna-Mitchell A, Rantell A, Thiagamoorthy G, Cardozo L. Are we justified in suggesting change to caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated drink intake in lower urinary tract disease? Report from the ICI-RS 2015. Neurourol Urodyn 2017;36(4):876–881. doi: 10.1002/nau.23149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol 2015;193(5):1572–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Am Urol Assoc Guidel 2014:1–45. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.064 [DOI]

- 19.Hooton TM, Vecchio M, Iroz A, et al. Effect of Increased Daily Water Intake in Premenopausal Women With Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(11):1509. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du C, Lee W, Moskowitz D, Lucioni A, Kobashi KC, Lee UJ. I leaked, then I Reddit: experiences and insight shared on urinary incontinence by Reddit users. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31(2):243–248. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04165-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Topolovec-Vranic J, Natarajan K. The use of social media in recruitment for medical research studies: A scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2016;18(11). doi: 10.2196/jmir.5698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mant J, Painter R, Vessey M. Epidemiology of genital prolapse: observations from the Oxford Family Planning Association Study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104(5):579–585. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9166201. Accessed June 19, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, Albert X, Ng CW. Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AL, Brown J, Wyman JF, Berry A, Newman DK, Stapleton AE. Treatment and Prevention of Recurrent Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Rapid Review with Practice Recommendations. J Urol 2018;200(6):1174–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.04.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aydin A, Ahmed K, Zaman I, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26(6):795–804. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2569-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson D, Hanna-Mitchell A, Rantell A, Thiagamoorthy G, Cardozo L. Are we justified in suggesting change to caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated drink intake in lower urinary tract disease? Report from the ICI-RS 2015. Neurourol Urodyn 2017;36(4):876–881. doi: 10.1002/nau.23149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dallosso HM, Mcgrother CW, Matthews RJ, Donaldson MMK. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with overactive bladder and stress incontinence: a longitudinal study in women doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04271.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Danforth KN, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Stress, Urge and Mixed Urinary Incontinence. J Urol 2009;181(1):193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardella B, Daniela Iacobone A, Porru D, et al. Effect of local estrogen therapy (LET) on urinary and sexual symptoms in premenopausal women with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/ BPS) Effect of local estrogen therapy (LET) on urinary and sexual symptoms in premenopausal women with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS). Gynecol Endocrinol 2015;31(10):828–832. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2015.1063119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayrak O, Erturhan S, Seckiner I, Erbagci A, Ustun A, Karakok M. Chemical cystitis developed in experimental animals model: Topical effect of intravesical ozone application to bladder. Urol Ann 2014;6(2):122–126. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.130553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.