Abstract

Background

The relative proportion of visceral fat (VAT) to subcutaneous fat (SAT) has been described as a major determinant of insulin resistance (IR). Our study sought to evaluate the effect of body fat distribution on glucose metabolism and intrahepatic fat content over time in a multiethnic cohort of obese adolescents.

Subjects/Methods

We examined markers of glucose metabolism by oral glucose tolerance test, and body fat distribution by abdominal MRI at baseline and after 19.2 ± 11.4 months in a cohort of 151 obese adolescents (88 girls, 63 boys; mean age 13.3 ± 3.4 years; mean BMI z-score 2.15 ± 0.70). Hepatic fat content was assessed by fast-gradient MRI in a subset of 93 subjects. We used the median value of VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio within each gender at baseline to stratify our sample into high and low ratio groups (median value 0.0972 in girls and 0.118 in boys).

Results

Female subjects tended to remain in their VAT/(VAT + SAT) category over time (change over follow-up P = 0.14 among girls, and P = 0.04 among boys). Baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) strongly predicted the hepatic fat content, fasting insulin, 2-h glucose, and whole-body insulin sensitivity index at follow-up among girls, but not in boys.

Conclusions

The VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio is a major determinant of impaired glucose metabolism and hepatic fat accumulation over time, and its effects are more pronounced in girls than in boys.

Introduction

Childhood obesity epidemic represents one of the main health problem worldwide [1], as early-onset obesity is associated with increased morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in young adults [2]. The pathogenic link between obesity and CVD is driven mainly by insulin resistance (IR), the most common complication of obesity and the major pathogenic determinant of early-onset type 2 diabetes (T2D) and dyslipidemia [3].

Altered partitioning of fat has a profound influence on systemic metabolism and, hence, on the risk for metabolic diseases [4, 5]. Indeed, the ratio of visceral fat depot to abdominal subcutaneous fat depot measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents the propensity to store fat viscerally and ectopically in both adults and pediatric subjects [6–8]. In a cross-sectional study, our group previously described a distinct “phenotype” in obese adolescents characterized by a thin superficial layer of abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), increased visceral adipose tissue (VAT), fatty liver and marked IR [5]. Moreover, Taksali et al. showed that in obese adolescents an imbalance between VAT and SAT depots and a corresponding dysregulation of the adipokine milieu were associated with excessive accumulation of fat in the liver and muscle, and ultimately led to IR and the metabolic syndrome [7]. The excess accumulation of lipids in the VAT is most likely due to the relatively poor expandability of the SAT in certain individuals [6], and represents a major source of proinflammatory mediators and free fatty acids (FFAs), two major players in the development of IR [9]. However, these studies are limited by the cross-sectional design and inability to provide information on potential causality.

Although there is vast literature describing the effects of altered fat distribution and ectopic fat accumulation on metabolic deterioration in adults [10–12], little is known about this phenomenon during adolescence [13].

In our current study, we set out to investigate the dynamic changes of VAT depot relative to the overall abdominal fat over time, and how these changes might affect metabolic changes over time in a population of ethnically diverse obese adolescents. We hypothesized that higher baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio would have a significant negative impact on the changes in glucose metabolism, IR, and fatty liver over time in obese youth. Furthermore, the latter would have different effects among girls as compared with boys.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This longitudinal study included 151 obese adolescents (88 girls and 63 boys; mean age 13.3 ± 3.4 years; mean body mass index (BMI) z-score 2.15 ± 0.70; Caucasians 35.1%, African Americans 27.2%, and Hispanics 37.7%) from our multiethnic cohort participating in the Yale Study of Pathogenesis of Youth Onset Type 2 Diabetes (PYOD) study (NCT01967849). The latter is an on-going project aimed at studying early alterations in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in obese youth. Subjects were followed biannually as outpatients, receiving standard lifestyle counselling for both nutrition and physical activity aimed at obese pediatric population. Nutrition counselling included decreasing intake of juice, switching to diet beverages, switching from whole to low-fat milk, and bringing lunch to school vs. choosing hot lunch. Exercise counselling included decreasing sedentary activities (computer and video games) and finding an activity the participant enjoyed enough to engage in on a regular basis. Subjects were eligible if they had no chronic illness, had a BMI of > 85th percentile for age and gender, and were not taking any medications that might alter glucose and lipid metabolism. Clinical examination was performed in all subjects, including weight and height measurements, BMI calculation, and staging of pubertal development according to Tanner’s classification [14]. All subjects underwent oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) and MRI to assess VAT and SAT [15] deposits at baseline and at follow-up. The Yale Human Investigation Committee approved the study, and written informed consent and assent were obtained.

Imaging studies

Abdominal fat partitioning

Abdominal MRI studies were performed on a GE or Siemens Sonata 1.5 Tesla system, as previously reported [16]. A single slice, obtained at the level of the L4/L5 disc space, was analyzed for each subject [16].

Intrahepatic fat content

Hepatic fat fraction (HFF), an estimate of the percentage of fat in the liver, was measured by fast-gradient MRI in 49 girls and 44 boys at baseline and follow-up [16]. HFF was measured in a single slice of the liver; we validated this method against proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) and found a strong correlation (r = 0.93, P = 0.001) [17]. During the validation study [18], repeated assessments were performed on the same day by the same operator to investigate the technique reproducibility. The reported within-subject SD for %HFF was 1.9%. This degree of reproducibility is within the boundaries to make this a viable method to assess the relation between HFF and metabolic outcomes. Moreover, they demonstrated that a two-point Dixon (2PD) HFF cutoff of 3.6% provided good sensitivity (80%) and specificity (87%) compared with a 1H-MRS reference [17].

Body composition

Total body composition was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry with a Hologic scanner.

OGTT

All subjects were invited to the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation at 08:00 a.m. after an overnight fast. After the placement of an indwelling venous line, baseline samples were obtained for glucose, insulin, C-peptide, lipid profile, liver enzymes, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). A standard 2-h OGTT was performed as previously reported [18]. The degree of IR was evaluated in fasting conditions as homeostasis model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR), [insulin (mU/l) × glucose level (mmol/l)/22.5] [19]. In addition, the Matsuda index or whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI), the ratio of the incremental changes in insulin vs. glucose over the first 30-min of the OGTT (insulinogenic index (IGI)) were calculated as previously described [18, 20].

Biochemical analyses

Plasma glucose was determined using a glucose analyzer by the glucose oxidase method (Beckman Instruments, Brea, CA). Plasma insulin was measured by the Linco RIA, lipid levels were determined with an Auto-Analyzer (model 747–200), and liver enzymes were measured using standard automated kinetic enzymatic assays.

Statistical analysis

Using median values of VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio among boys and girls, a binary variable of low/high VAT/(VAT + SAT) was used to track the proportion of adolescents either maintaining or changing the relative fat distribution over time. A sample size of at least 40–60 adolescents within each gender stratum will achieve 80% power to detect an effect size (f 2) in the range of 0.15–0.26 in a multiple linear regression analysis, attributable to one independent variable (baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio) using an F-test with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05, and adjusting for an additional five independent variables. Cohen defined values of f 2 near 0.02 as small, near 0.15 as medium, and above 0.35 as large [21]. Thus, we will have at least 80% [21] power to observe medium to large effect sizes when modeling continuous outcomes of interest at follow-up, such as fasting insulin, 2-h glucose, WBISI, and HFF%. We were able to include at least 40 boys and at least 40 girls when analyzing HFF%, and at least 60 boys and even more girls (N = 88) for other outcomes of interest.

Wilcoxon sum rank test was used to compare the distributions of VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio between boys and girls. Differences in anthropometric and metabolic biomarkers between subjects with low or high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline were evaluated separately among boys and girls both at baseline and follow-up. Generalized linear models (with either logit, multinomial and identity link functions for binary, categorical and continuous outcomes, respectively), adjusting for age, BMI z-score, Tanner stage, and ethnicity, was performed to evaluate differences in anthropometric and metabolic parameters. Results were tabulated as percent and means (standard deviations). Observed proportions of subjects with high/low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratios at baseline and follow-up were compared using McNemar’s test for matched pairs. In adjusted analyses, stability of high/low VAT/(VAT + SAT) phenotype over time was examined using nonlinear mixed effects modeling, with categorical time (baseline and follow-up), age, Tanner stage, change in BMI z-score, and ethnicity as fixed effects, and with subject as a random effect. Spearman correlation coefficient (r) was used to evaluate the unadjusted associations between baseline continuous VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio and biochemical characteristics of subjects at follow-up, stratified by gender. Multiple linear regression models further examined the effect of baseline continuous VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio on the markers of glucose metabolism and fatty liver at follow-up, as continuous variables and as rates of change over time, adjusting for the baseline values of the outcomes, the duration of follow-up, changes in BMI z-score, Tanner stage, and ethnicity. Results are presented as scatter plots with trend lines for linear associations, and adjusted parameter estimates with standard errors for the continuous VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio. Gender was evaluated as an effect modifier in the multiple linear regressions, using an interaction term with the baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio; therefore, the results are presented separately for boys and girls. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and statistical significance was assessed at the two-tailed 0.05 alpha threshold.

Results

Stability of VAT/(VAT + SAT) phenotype over time

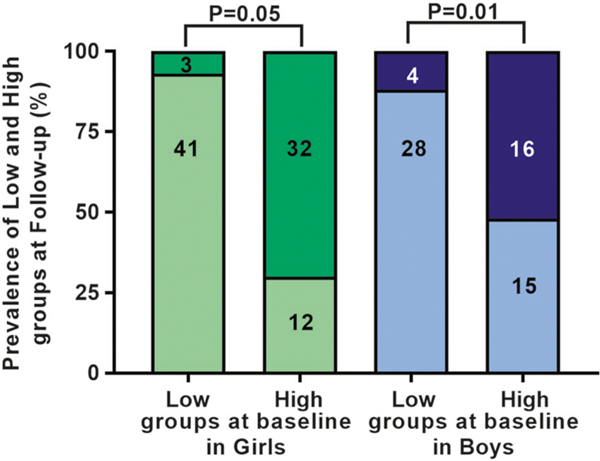

Baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio strongly correlated with the ratio at follow-up (r = 0.82, among girls, and r = 0.70 in boys; both P = 0.001) and its change from baseline to follow-up (r = −0.53, among girls, and r = −0.54 in boys; both P < 0.0001). Subjects in the low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio group at baseline were likely to remain in the low group at follow-up (median follow-up 16.1 months, interquartile range (IQR) 11.3–25.2). Regards to subjects in the high VAT/(VAT + SAT) group, girls retained their body fat distribution phenotype (P = 0.05). Conversely, boys significantly changed their phenotype (P = 0.02) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Changes in VAT/(VAT + SAT) categories over time. Subjects in the low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio group at baseline tended to remain in the low group at follow-up, whereas subjects in the high VAT/(VAT + SAT) group at baseline tended to retain their group membership among girls, but not among boys. Light green indicates low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio and dark green indicates high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio group in girls. Light blue indicates low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio and dark blue indicates high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio group in boys. Numbers in histograms describe the number of adolescents by category and group

Anthropometric and metabolic features of girls and boys at baseline and follow-up by low and high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline

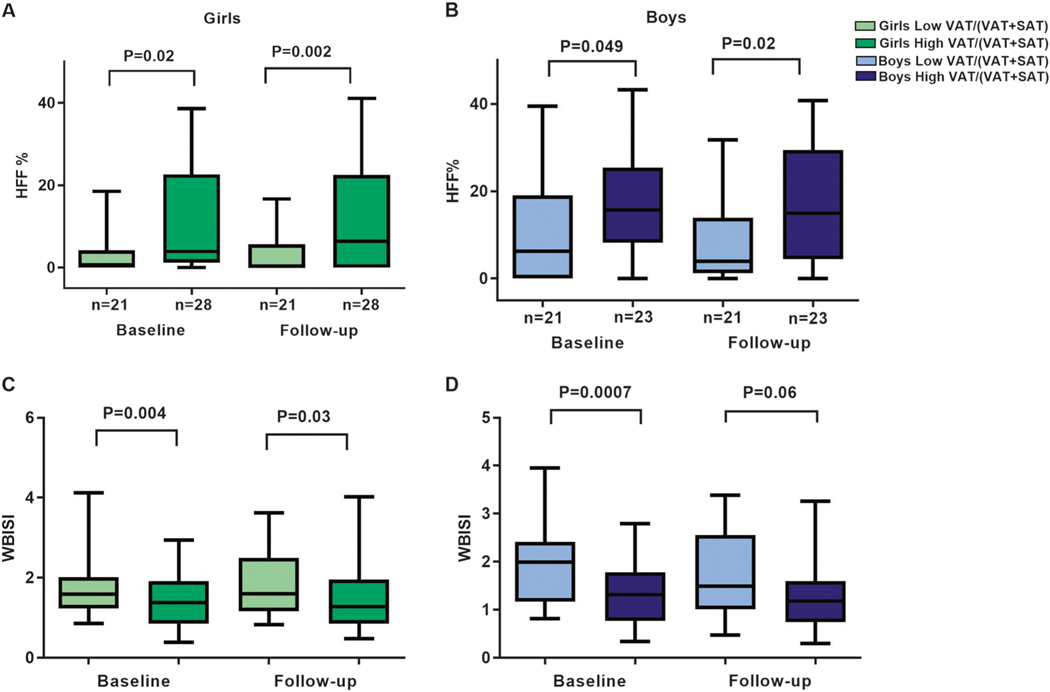

The distribution of VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline significantly differed by gender (P = 0.01), with the median value of 0.0972 (IQR 0.075–0.128) among girls, and 0.118 (IQR 0.088–0.152) in boys (Supplementary Figure 1). Groups of low vs. high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline did not differ significantly by weight, height, BMI, z-score BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio, body fat %, and duration of follow-up. African Americans were less likely to be in the group with high VAT/(VAT + SAT) among both boys (P = 0.01) and girls (P = 0.002). Among girls, the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and T2D was greater in the high VAT/(VAT + SAT) group compared with the low ratio (odds ratio (OR) 5.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.7–15.7, P = 0.005) (Table 1). Furthermore, girls with high VAT/(VAT + SAT) at baseline showed higher 2-h glucose (P = 0.008), AUC 2-h glucose (P = 0.003), higher fasting insulin (P = 0.004), higher HOMA-IR (P = 0.01), lower oral disposition index (P = 0.001), lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (P = 0.02), and lower WBISI (P = 0.004) at baseline adjusted for confounders (Table 2 and Fig. 2). These differences in 2-h glucose (P = 0.009), AUC 2-h glucose (P = 0.01), HDL-cholesterol (P = 0.02) (Table 2), and WBISI (P = 0.03) (Fig. 2) were also confirmed at follow-up. Moreover, girls with high ratio shewed a significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome compared with girls with low ratio at follow-up (10.3 vs. 31.3%, respectively; P = 0.02).

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics of the study population at baseline and follow-up, stratified by gender and median VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline

| Girls (n = 88) | Boys (n = 63) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Low (n = 44) | High (n = 44) | P-value | Low (n = 44) | High (n = 44) | P-value | Low (n = 32) | High (n = 31) | P-value | Low (n = 32) | High (n = 31) | P-value | |

| Ethnicity (C/AA/H)% | 31.1/44.4/24.5 | 43.2/15.9/40.9 | 0.01 | 15.6/37.5/46.9 | 48.4/6.5/45.2 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Follow-up (months) | 19.0 ± 11.2 | 19.1 ± 11.0 | 0.67 | 16.7 ± 10.8 | 22.3 ± 11.5 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Age (years) | 14.2 ± 2.7 | 15.7 ± 2.7 | 0.18 | 15.7 ± 2.7 | 15.0 ± 3.3 | 0.19 | 14.0 ± 2.2 | 12.6 ± 2.2 | 0.02 | 15.4 ± 2.2 | 14.5 ± 2.5 | 0.13 |

| Tanner stage (II-III/IV-V)% | 34.1/65.9 | 47.7/52.3 | 0.27 | 13.6/86.4 | 27.3/72.7 | 0.19 | 56.3/43.7 | 77.4/22.6 | 0.11 | 28.1/71.9 | 38.7/61.3 | 0.43 |

| Glucose tolerance (NGT/IGT/T2D) | 82.2/17.8/0 | 50/45.2/4.8 | <0.01 | 86.7/13.3/0.0 | 71.4/26.2/2.4 | 0.17 | 71.9/28.1/0.0 | 76.7/20/3.3 | 0.46 | 61.3/35.5/3.2 | 92.6/7.4/0.0 | 0.02 |

| Metabolic syndrome (%) | 31.8 | 44.4 | 0.26 | 10.3 | 31.3 | 0.02 | 37 | 40 | 0.21 | 44 | 41.4 | 0.21 |

| Weight (kg) | 90.1 ± 20.6 | 87.4 ± 21.1 | 0.55 | 96.4 ± 18.2 | 95.8 ± 22.7 | 0.89 | 98.9 ± 23.1 | 88.7 ± 21.0 | 0.08 | 106.9 ± 22.8 | 106.9 ± 24.7 | 0.99 |

| Height (cm) | 157.9 ± 8.8 | 157.2 ± 11.2 | 0.75 | 159.7 ± 6.7 | 160.9 ± 9.7 | 0.49 | 166.1 ± 13.4 | 161.5 ± 12.2 | 0.17 | 171.2 ± 10.9 | 170.5 ± 10.4 | 0.79 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.8 ± 6.4 | 34.9 ± 5.8 | 0.51 | 37.6 ± 5.9 | 36.6 ± 6.5 | 0.44 | 35.5 ± 5.6 | 33.6 ± 4.6 | 0.17 | 36.4 ± 6.4 | 36.4 ± 5.7 | 0.98 |

| BMI z-score | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.51 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.61 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.62 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.67 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 107.8 ± 12.8 | 105.9 ± 10.1 | 0.34 | 112.4 ± 13.4 | 113.4 ± 14.7 | 0.75 | 101.0 ± 16.6 | 102.8 ±10.4 | 0.52 | 106.0 ± 15.8 | 109.8 ± 14.9 | 0.26 |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.66 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.65 ± 0.07 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.83 |

| Body fat (%) | 42.9 ± 4.6 | 44.1 ± 5.5 | 0.81 | 43.9 ± 4.6 | 44.6 ± 5.2 | 0.94 | 40.3 ± 8.1 | 43.9 ± 9.8 | 0.07 | 39.5 ± 8.2 | 40.2 ± 9.4 | 0.78 |

| Lean body mass | 51.6 ± 13.7 | 48.1 ± 9.9 | 0.82 | 50.5 ± 8.5 | 51.5 ± 9.6 | 0.98 | 56.2 ± 13.6 | 48.1 ± 14.7 | 0.36 | 59.8 ± 11.6 | 60.2 ± 14.9 | 0.72 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 115.4 ± 7.7 | 121.7 ± 10.2 | <0.01 | 115.6 ±8.7 | 117.5 ± 10.7 | 0.55 | 122.4 ± 11.9 | 121.0 ± 12.9 | 0.32 | 123.7 ± 12.4 | 125.4 ± 9.4 | 0.88 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 69.1 ± 10.3 | 72.1 ± 8.9 | 0.08 | 70.8 ±8.6 | 69.1 ± 7.6 | 0.32 | 70.4 ± 8.5 | 69.6 ± 10.3 | 0.53 | 70.7 ± 11.0 | 73.3 ± 13.8 | 0.82 |

| At distribution | ||||||||||||

| Visceral fat (cm2) | 43.8 ±14.2 | 75.1 ±20.8 | <0.0001 | 47.5 ± 17.2 | 73.5 ±27.7 | <0.0001 | 52.4 ±24.3 | 84.0 ±27.0 | <0.0001 | 58.3 ± 29.2 | 78.4 ± 41.4 | <0.01 |

| Subcutaneous fat (cm2) | 562.1 ± 155.7 | 499.7 ± 164.2 | <0.01 | 621.8 ± 177.6 | 574.7 ± 176.5 | 0.09 | 576.3 ± 182.6 | 449.2 ± 119.4 | 0.02 | 579.8 ± 194.2 | ± 166.6 | 0.07 |

| VAT/(VAT + SAT) | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ±0.05 | <0.0001 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ±0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ±0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ±0.04 | <0.01 |

| VAT/SAT | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ±0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ±0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ±0.05 | <0.0001 | 0.10±0.04 | 0.15 ±0.06 | <0.01 |

Data are shown as mean and SD. P-values refers to differences between group comparisons (low ratio vs. high ratio group). P-values are adjusted by age, BMI z-score, Tanner stage, and ethnicity.P-values < 0.05, shown in bold, are statistically significant

C Caucasian, AA African American, H Hispanic, NGT normal glucose tolerance, IGT impaired glucose tolerance, T2D type 2 diabetes, VAT visceral adipose tissue, SAT subcutaneous adipose tissue

Table 2.

Metabolic characteristics of the study population at baseline and follow-up, stratified by gender and median VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline

| Girls (n = 88) | Boys (n = 63) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Low (n = 44) | High (n = 44) | P-value | Low (n = 44 ) | High (n = 44) | P-value | Low (n = 32) | High (n = 31 ) | P-value | Low n= 32) | High (n = 31) | P-value | ||||||||||||

| Glucose metabolism | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 91.8 ± 8.5 | 94.9 ± 9.4 | 0.06 | 90.3 ± 7.7 | 93.3 ± 10.2 | 0.24 | 95.4 ± 9.9 | 94.7 ± 8.5 | 0.62 | 98.6 ± 11.0 | 93.0 ± 7.1 | 0.07 | |||||||||||

| Fasting insulin (mcU/ml) | 29.3 ± 10.6 | 39.3 ± 20.9 | <0.01 | 32.5 ± 13.6 | 39.4 ± 19.8 | 0.12 | 30.9 ± 11.6 | 41.9 ± 21.1 | <0.01 | 37.4 ± 31.3 | 47.0 ± 36.6 | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| 2-h glucose (mg/dl) | 121 ± 19.9 | 137 ± 32.6 | <0.01 | 116 ± 18.3 | 127 ± 31.4 | <0.01 | 120 ± 25.1 | 125 ± 21.9 | 0.77 | 125 ± 25.1 | 123 ± 15.9 | 0.69 | |||||||||||

| AUC 2-h glucose | 126 ± 17.3 | 141 ± 27.4 | <0.01 | 123 ± 15.6 | 132 ± 21.9 | 0.01 | 132 ± 22.0 | 135 ± 18.9 | 0.67 | 137 ± 24.4 | 133 ± 15.4 | 0.79 | |||||||||||

| HbAlc % (mmol/mol) | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 0.93 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.76 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.86 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 0.52 | |||||||||||

| (36.8 ± 4.4) | (36.2 ± 4.5) | (36.8 ± 4.9) | (36.1 ± 4.2) | (36.9 ± 5.1) | (35.4 ± 5.1) | (36.6 ± 4.6) | (36.5 ± 4.8) | ||||||||||||||||

| HOMA- IR | 6.7 ± 2.5 | 8.3 ± 3.8 | 0.01 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 8.7 ± 3.9 | 0.38 | 7.2 ± 2.7 | 8.4 ± 3.1 | 0.14 | 8.0 ± 3.9 | 8.5 ± 3.7 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| WBISI | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | <0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.03 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | <0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.06 | |||||||||||

| IGI | 4.8 ± 3.7 | 4.0 ± 2.6 | 0.23 | 4.4 ± 2.7 | 4.5 ± 2.9 | 0.96 | 4.8 ± 5.9 | 5.2 ± 3.8 | 0.05 | 4.1 ± 3.1 | 5.4 ± 3.4 | 0.04 | |||||||||||

| DI | 7.8 ± 4.9 | 4.9 ± 2.9 | <0.01 | 7.4 ± 5.9 | 6.9 ± 3.7 | 0.12 | 7.7 ± 8.8 | 5.7 ± 2.8 | 0.82 | 6.4 ± 5.6 | 5.7 ± 2.5 | 0.85 | |||||||||||

| Lipid profile | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 161.9 ± 32.9 | 156.7 ± 25.1 | 0.68 | 152.1 ± 34.2 | 154.3 ± 29.1 | 0.27 | 146.4 ± 31.4 | 164.8 ± 35.3 | 0.11 | 138.7 ± 30.6 | 158.8 ± 35.0 | 0.06 | |||||||||||

| HDL- cholesterol (mg/dl) | 43.7 ± 9.1 | 37.8 ± 6.8 | 0.02 | 47.8 ± 12.1 | 39.8 ± 9.4 | 0.02 | 42.4 ± 9.7 | 40.5 ± 9.7 | 0.26 | 41.6 ± 11.2 | 40.4 ± 9.3 | 0.97 | |||||||||||

| LDL- cholesterol (mg/dl) | 96.9 ± 27.5 | 93.5 ± 22.9 | 0.39 | 87.3 ± 32.4 | 92.5 ± 27.5 | 0.08 | 86.6 ± 24.8 | 94.3 ± 29.9 | 0.44 | 77.3 ± 24.1 | 92.2 ± 30.4 | 0.18 | |||||||||||

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 101.8 ± 58.6 | 115.7± 46.1 | 0.27 | 86.1 ± 71.0 | 107.1 ±41.5 | 0.02 | 86.7 ± 38.1 | 129.3 ± 55.5 | 0.02 | 86.3 ± 49.5 | 131.4± 84.9 | 0.07 | |||||||||||

| Liver enzymes | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ALT (U/l) | 14.0 ± 7.3 | 24.5 ± 22.0 | 0.13 | 14.3 ± 7.83 | 24.4 ± 19.5 | 0.13 | 30.3 ± 24.1 | 39.2 ± 25.7 | 0.23 | 25.1 ± 15.0 | 42.2 ± 36.3 | 0.15 | |||||||||||

| AST (U/l) | 21.8 ± 9.4 | 22.2 ± 12.5 | 0.71 | 17.5 ± 4.6 | 22.2 ± 11.3 | 0.14 | 26.7 ± 11.5 | 29.8 ± 10.2 | 0.39 | 23.8 ± 10.2 | 31.5 ± 20.0 | 0.18 | |||||||||||

Data are shown as mean and SD. P-values refers to differences between group comparisons (low ratio vs. high ratio group). P-values are adjusted by age, BMI z-score, Tanner stage, and ethnicity. P-values < 0.05, shown in bold, are statistically significant

F. glucose fasting glucose, F. insulin fasting insulin, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, WBISI whole-body insulin sensitivity index, IGI insulinogenic index, DI oral disposition index; AUC area under the curve

Fig. 2.

Differences in hepatic fat content (HFF%) (a, b) and whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI) (c, d) between low and high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio groups at baseline and follow-up in girls and boys. The data are expressed using box plots (5th percentile, median, 95th percentile). Light green indicates low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio and dark green indicates high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio group in girls. Light blue indicates low VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio and dark blue indicates high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio group in boys

Boys with high VAT/(VAT + SAT) had higher fasting insulin levels (P = 0.003) and triglycerides (P = 0.02) at baseline (Table 2). Adjusting for confounding factors, insulin sensitivity (WBISI) at baseline was significantly reduced in boys with the high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio compared with the low VAT/(VAT + SAT) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Intrahepatic fat content according to low and high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline

Data for HFF% were available for 49 (55.6%) girls and for 44 (69.8%) boys. We found no statistically significant differences in the anthropometric patient characteristics between those who had this outcome measured and those who had missing observations (Supplementary Table 1). Girls and boys with high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio showed a significantly higher %HFF both at baseline (P = 0.02 and P = 0.049, respectively) and follow-up (P = 0.002 and P = 0.02, respectively) (Fig. 2). Moreover, among girls and boys, high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio was significantly associated with HFF% at baseline (r = 0.44, P = 0.002, and r = 0.37, P = 0.01, respectively) (data not shown).

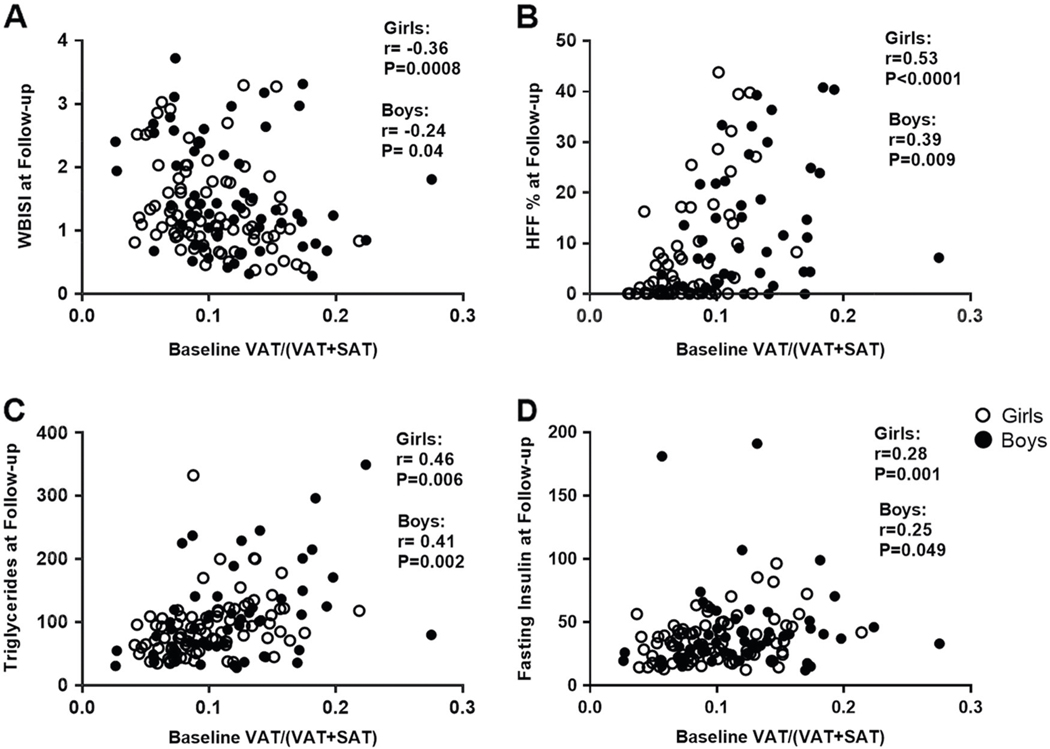

Association between baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) and markers of glucose metabolism and fatty liver at follow-up in the populations of girls and boys

In the unadjusted analyses, we observed an inverse correlation between baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) and WBISI at follow-up among girls (r =−0.36, P = 0.0008) and boys (r =−0.24, P = 0.04). Significant correlations were also observed with triglycerides (r = 0.46 in girls, P = 0.006; and r = 0.41, in boys, P = 0.002), fasting insulin (r = 0.28 in girls, P = 0.001; and r = 0.25, in boys, P = 0.049) and HFF% (r = 0.53 in girls, P < 0.0001; and r = 0.39, in boys, P = 0.009) at follow-up (Fig. 3). Only in girls, the baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio was positively correlated with the 2-h glucose (r = 0.22, P = 0.04) and the AUC 2-h glucose (r = 0.25, P = 0.02), whereas negatively correlated HDL-cholesterol (r =−0.43, P < 0.0001) (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Association of the baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio with whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI), hepatic fat fraction (HFF, %), triglycerides, and fasting insulin at follow-up in girls, and boys (a–d). White circles indicate girls and black circles indicate boys

In the adjusted analyses, the baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio was found to be a significant predictor of fasting insulin (P = 0.01), 2-h glucose (P = 0.004), WBISI (P = 0.008), and HFF% (P = 0.005) at follow-up, with gender as an effect modifier (PVAT/(VAT+SAT)*gender = 0.08 for fasting insulin, PVAT/(VAT+SAT)*gender = 0.02 for 2-h glucose, PVAT/(VAT+SAT)*gender = 0.11 for WBISI, and PVAT/(VAT+SAT)*gender = 0.02 for HFF%). In the adjusted analyses performed separately for gender, these associations were confirmed for girls, whereas no significant associations were observed among boys at follow-up. Of note, the baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio was found to be a predictor of changes in HFF % over time among girls (β = 248, SE 106, P = 0.03), no association was found among boys. Ethnicity was a predictor of WBISI at follow-up, being the Caucasian ethnicity positively associated with WBISI (P = 0.02) in boys, no associations were found between ethnicity and metabolic outcomes among girls. We did not observe any ethnic-related difference in the prediction of impaired glucose metabolism (boys P = 0.50; girls P = 0.42) and hepatic fat content (boys P = 0.72; girls P = 0.85).

Moreover, compared with girls with a low baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio, those with a high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline showed a 4.4-fold higher risk of IGT and T2D at follow-up, independent of confounding factors (OR 4.4, 95% CI 1.2–16.4, P = 0.03).

In addition, we investigated the association between VAT area and VAT/SAT ratio at baseline and metabolic parameters at follow-up. The VAT area was significantly correlated with VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio at baseline (r = 0.73, P < 0.0001). The VAT area showed a significant correlation with intrahepatic fat content at follow-up (r = 0.52, P = 0.0001 in girls, and r = 0.39, P = 0.01 in boys), and fasting insulin only in girls (r = 0.30, P = 0.009). However, it was not correlated with 2-h glucose (r = 0.20, P = 0.07 in girls, and r =−0.19, P = 0.16 I boys), glucose AUC (r = 0.13, P = 0.21 in girls, and r =−0.12, P = 0.36 in boys) and whole-body insulin sensitivity index (r = −0.21, P = 0.05 in girls, and r =−0.19, p = 0.34; in boys). The VAT/SAT ratio was significantly correlated with metabolic parameters at follow-up in both sexes (HFF%: r = 0.44, P = 0.001 in girls, and r = 0.37, P = 0.01 in boys; fasting insulin: r = 0.28, P = 0.04 in girls, and r = 0.26, P = 0.04 in boys; WBISI: r =−0.36, P = 0.0008 in girls, and r =−0.25, P = 0.04, in boys). VAT/SAT was significantly correlated with 2-h glucose (r = 0.28, P = 0.02) and 2-h glucose AUC (r = 0.24, P = 0.02) only in girls.

Discussion

Body fat distribution and metabolic impairment

In this study, we confirmed our previous report of a cross-sectional association between altered body fat partitioning and higher prevalence of alteration in glucose and lipid homeostasis [7, 8]. Additionally, novel information is provided by our longitudinal follow-up data indicating that these associations seem to persist over time and to be more pronounced in obese girls, despite having a 12% lower visceral fat area than boys. In particular, obese girls with a high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio show higher 2-h glucose, as well as lower degree of IR and HDL-cholesterol. Furthermore, in obese girls the baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) was predictive of the degree of IR, 2-h glucose, intrahepatic fat content and IGT at follow-up. Moreover, we found similar results evaluating the association between VAT/SAT ratio and metabolic parameters at follow-up. Several studies have addressed VAT/SAT as a stronger determinant of IR rather than total amount of VAT or overall adiposity [10–12]. Kaess et al. have reported an association between high VAT/SAT and higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in a group of adults and, consistent with our results, the association was weaker in men than in women [10]. Gastaldelli et al. found that VAT/SAT was inversely correlated with insulin sensitivity assessed by a 3-h OGTT [11]. Similarly, high VAT/SAT ratio was associated with increased hepatic IR in a population of 36 adult males with T2D [12]. These studies support our findings that this phenotype is an important risk factor of adverse cardiometabolic profile. Moreover, in our population, baseline VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio was correlated with intrahepatic fat content at follow-up. Intrahepatic deposition of fat has been associated with IR, impaired beta-cell function, and prediabetes in obese adolescents [22]. As suggested by cross-sectional studies, our longitudinal data further support the hypothesis that higher VAT proportion in obese adolescents is associated with ectopic liver fat accumulation and metabolic alterations [7, 8], especially among girls. Here we report how this association persists over time in obese youth.

Potential underlying mechanisms: the role of sex and genetics

Due to the protective effect of estrogen, pubertal girls and adult women are generally less likely to develop unfavorable metabolic profile until the onset of menopause [23, 24]. During menopause, women lose this protective effect and, therefore, are prone to develop VAT [25] and adverse cardiometabolic events [24]. In our cohort, obese adolescent girls with a high VAT/(VAT + SAT) also seem to lose this metabolic advantage. They tend to develop a metabolic profile closer to that seen in post-menopausal women, characterized by severe IR, fatty liver, and dyslipidemia at a young age. Moreover, girls tend to have a more stable body fat distribution phenotype compared with boys. This observation might be clinically relevant as it identifies a specific group of girls with a high cardiometabolic risk.

The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are unclear and need to be studied. A potential influence of sexual hormones might be hypothesized in determining the unfavorable metabolic profile and the stability of phenotype. White adipose tissue is a metabolically active depot in which sex hormones, both estrogen and androgen, are metabolized [26]. Corbould et al. have shown that, in basal conditions, the rates of estrogen and androgen productions are the same in subcutaneous and visceral fat depots of women [27]. Later, they found that the two depots differed in enzymes’ gene expression in obese women, having a lower androgen production in subcutaneous adipocytes and a relative higher production of androgens in visceral adipocytes [28]. Unfortunately, to date no additional data are available, therefore, this hypothesis warrants further investigation.

In our study, we observed that girls with a high VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio were more likely to have a high ratio at follow-up, suggesting that in some obese adolescents there is a higher constitutional propensity to store fat viscerally. These findings are in line with several genome-wide association studies that have reported several associations between genetic loci and body fat distribution [29–33]. Heritability estimate for body fat distribution varies from 36 to 47%, independent of total adiposity [29], with higher rates in twin females [30]. Moreover, the evidence that body fat partitioning differs among different ethnicity support the genetic background underlying body fat distribution [34], even if the VAT deleterious effect on metabolic impairment seems to overcome the genetic background [35]. Nevertheless, the molecular and genetic mechanisms that underlie body fat partitioning are poorly understood.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study assessing the association between VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents. Moreover, we used a highly sensitive technique to characterize the body fat distribution (MRI). Limitations of the study are: (1) the lack of measurements of sexual hormones, which could help us in understanding the different findings among boys and girls; (2) there is no guarantee that due to the available sample size for boys we did not commit a type 2 error by reporting the observed nonsignificant findings in the outcomes for this group of adolescents; (3) the relative short duration of follow-up might impair the ability to detect modifications of glucose tolerance status and metabolic impairment [30]; and the lack of measures of adherence to diet and physical activity counselling during the observation period.

In conclusion, VAT/(VAT + SAT) ratio predicts insulin sensitivity in adolescents over time and predisposes obese youth, especially girls, to develop an unfavorable cardiometabolic profile. Therefore, VAT proportion might represent a clinically meaningful tool in the light of individuate obese adolescents with a higher risk of cardiometabolic comorbidities.

Acknowledgements

This work has been made possible by R01-DK111038 and R01-HD028016 to SC. NS is funded by the American Heart Association (AHA) through the 13SDG14640038 and the 16IRG27390002. AG was supported by the Robert Leet Patterson and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust Mentored Research Award and the European Medical Information Framework (EMIF 115372). VS is funded by CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. This work was also made possible by DK045735 to the Yale Diabetes Research Center and Clinical and Translational Science Awards Grant UL1-RR- 024139 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0227-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.de Onis M, Blossner M, Borghi E. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twig G, Yaniv G, Levine H, Leiba A, Goldberger N, Derazne E,et al. Body-mass index in 2.3 million adolescents and cardiovascular death in adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Adamo E, Santoro N, Caprio S. Metabolic syndrome in pediatrics: old concepts revised, new concepts discussed. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58:1241–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee MJ, Wu Y, Fried SK. Adipose tissue heterogeneity: implication of depot differences in adipose tissue for obesity complications. Mol Asp Med. 2013;34:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss R, Dufour S, Taksali SE, Tamborlane WV, Petersen KF, Bonadonna RC, et al. Prediabetes in obese youth: a syndrome of impaired glucose tolerance, severe insulin resistance, and altered myocellular and abdominal fat partitioning. Lancet. 2003;362:951–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravussin ESS. Increased fat intake, impaired fat oxidation, and failure of fat cell proliferation result in ectopic fat storage, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:363–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taksali SE, Caprio S, Dziura J, Dufour S, Cali AM, Goodman TR, et al. High visceral and low abdominal subcutaneous fat stores in the obese adolescent: a determinant of an adverse metabolic phenotype. Diabetes. 2008;57:367–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kursawe R, Eszlinger M, Narayan D, Liu T, Bazuine M, Cali AM,et al. Cellularity and adipogenic profile of the abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue from obese adolescents: association with insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Diabetes. 2010;59:2288–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaess BM, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Murabito J, Hoffmann U, FoxCS. The ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat, a metric of body fat distribution, is a unique correlate of cardiometabolic risk. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2622–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gastaldelli A, Sironi AM, Ciociaro D, Positano V, Buzzigoli E, Giannessi D, et al. Visceral fat and beta cell function in nondiabetic humans. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2090–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki Y, DeFronzo RA. Visceral fat dominant distribution inmale type 2 diabetic patients is closely related to hepatic insulin resistance, irrespective of body type. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly AS, Dengel DR, Hodges J, Zhang L, Moran A, Chow L,et al. The relative contributions of the abdominal visceral and subcutaneous fat depots to cardiometabolic risk in youth. Clin Obes. 2014;4:101–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH. Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamashita A, Watanabe M, Sato K, Miyashita T, Nagatsuka T, Kondo H, et al. Reverse reaction of lysophosphatidylinositol acyltransferase. Functional reconstitution of coenzyme Adependent transacylation system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278: 30382–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgert TS, Taksali SE, Dziura J, Goodman TR, Yeckel CW, Papademetris X, et al. Alanine aminotransferase levels and fatty liver in childhood obesity: associations with insulin resistance, adiponectin, and visceral fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H, Taksali SE, Dufour S, Befroy D, Goodman TR, Petersen KF, et al. Comparative MR study of hepatic fat quantification using single-voxel proton spectroscopy, two-point dixon and three-point IDEAL. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:521–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, Taksali SE, Dufour S, Burgert TS, et al. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1096–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeckel CW, Taksali SE, Dziura J, Weiss R, Burgert TS, Sherwin RS, et al. The normal glucose tolerance continuum in obese youth: evidence for impairment in beta-cell function independent of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90: 747–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral-sciences. Perceptual and motor skills. Hillsdale, N.J. - L. Erlbaum Associates. 1988;67:1007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cali AM, De Oliveira AM, Kim H, Chen S, Reyes-Mugica M, Escalera S, et al. Glucose dysregulation and hepatic steatosis in obese adolescents: is there a link? Hepatology. 2009;49:1896–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hevener AL, Clegg DJ, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Impaired estrogen receptor action in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418(Pt 3):306–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. The sexual dimorphism of obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;402:113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried SK, Lee MJ, Karastergiou K. Shaping fat distribution: new insights into the molecular determinants of depot- and sex-dependent adipose biology. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:1345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meseguer APC, Cabero A. Sex steroid biosynthesis in white adipose tissue. Horm Metab Res. 2002;34:731–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbould AM, J J, Rodgers RJ. Expression of types 1, 2, and 3 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in subcutaneous abdominal and intra-abdominal adipose tissue of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corbould AMB, Lavranos TC, Rodgers RJ, Judd SJ. The effect of obesity on the ratio of type 3 17bhydroxysteroid dehydrogenase mRNA to cytochrome P450 aromatase mRNA in subcutaneous abdominal and intra-abdominal adipose tissue of women. Int J Obes. 2002;26:165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, Winkler TW, Qi L, Stein-thorsdottir V, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010;42:949–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, Ferreira T, Locke AE, Magi R, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518:187–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindgren CM, Heid IM, Randall JC, Lamina C, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Genome-wide association scan meta-analysis identifies three loci influencing adiposity and fat distribution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu AY, Deng X, Fisher VA, Drong A, Zhang Y, Feitosa MF, et al. Multiethnic genome-wide meta-analysis of ectopic fat depots identifies loci associated with adipocyte development and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2017;49:125–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox CS, Liu Y, White CC, Feitosa M, Smith AV, Heard-Costa N, et al. Genome-wide association for abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipose reveals a novel locus for visceral fat in women. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maligie M, Crume T, Scherzinger A, Stamm E, Dabelea D. Adiposity, fat patterning, and the metabolic syndrome among diverse youth: the EPOCH study. J Pediatr. 2012;161:875–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jukarainen S, Holst R, Dalgard C, Piirila P, Lundbom J, Hakkarainen A, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity as determinants of metabolic health-pooled analysis of two twin cohorts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]