Abstract

With growing attention to youth’s efforts to address sexual and gender diversity issues in Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs), there remains limited research on adult advisors. Do advisor characteristics predict their youth members’ advocacy? Among 58 advisors of 38 GSAs, we considered whether advisor attributes predicted greater advocacy by youth in these GSAs (n = 366) over the school year. GSAs varied in youth advocacy over the year. Youth in GSAs whose advisors reported longer years of service, devoted more time to GSA efforts each week, and employed more structure to meetings (to a point, with a curvilinear effect), reported greater relative increases in advocacy over the year (adjusting for initial advocacy and total meetings that year). Relative changes in advocacy were not associated with whether advisors received a stipend, training, or whether GSAs had co-advisors. Continued research should consider how advisors of GSAs and other social justice-oriented groups foster youth advocacy.

Keywords: Advocacy, GSA, Extracurricular groups, social justice, Adult mentors, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth

Youth are taking action and leadership to address social injustices in the current sociopolitical context (Akiva, Carey, Cross, O’Connor, & Brown, 2017; Stornaiuolo & Thomas, 2017). To this end, extracurricular groups and school clubs oriented around issues of social justice are settings wherein youth can come together to engage in collective action (Akiva et al., 2017; Iwasaki, 2016). Seeing that youth do not always have the same outlets as adults to have a voice and engage in civic action (Camino, 2000), these groups may be important for youth to participate in and lead advocacy efforts. Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs), school-based clubs in 37% of U.S. secondary schools (CDC, 2019), represent one such group for sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth and their heterosexual, cisgender allies (Griffin, Lee, Waugh, & Beyer, 2004). In GSAs, youth can garner support from peers, access SGM-affirming resources, and advocate to promote awareness of SGM issues and resist oppression (Griffin et al., 2004; Poteat, Yoshikawa, Calzo, Russell, & Horn, 2017). In the case of advocacy, GSAs may use school displays, social media, or awareness-raising events to promote visibility of SGM youth and to counteract oppression, petition for inclusive school policies and practices (e.g., gender-neutral bathrooms or inclusive curricula), among other efforts (Kosciw, Clark, Truong, & Zongrone, 2020; Mayberry, 2013; Poteat, Scheer, Marx, Calzo, & Yoshikawa, 2015).

Whereas GSAs and their youth members’ experiences have received increased attention from scholars in recent years (Marx & Kettrey, 2016; Poteat et al., 2017), there has been limited attention paid to their adult advisors (Graybill et al., 2015; Watson, Varjas, Meyers, & Graybill, 2010). Advisors often are teachers, counselors, nurses, or other school personnel (Griffin et al., 2004; Graybill et al., 2015). As key figures in GSAs, advisors may differ in their background and in their approaches to their role that could help explain why youth in some GSAs engage in more advocacy over a school year than others. We consider a number of these potentially relevant advisor attributes in the current study.

Understanding the Functions of GSAs

Although GSAs are not standardized programs, they are organized and operate in ways that emulate youth programs grounded in positive youth development (PYD) frameworks (Catalano et al., 2004; Lerner, Lerner, Bowers, & Geldhof, 2015). Essential elements of successful youth programs include providing a space that is safe and supportive, offering opportunities for youth to take on leadership, ensuring sufficient structure for the group to operate, and including adults who can provide guidance and mentorship (Catalano et al., 2004; Lerner et al., 2015). Many GSA members perceive support from their peers (Poteat, Calzo, & Yoshikawa, 2016; Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, & Laub, 2009) and some take on leadership roles in the GSA (Poteat, Yoshikawa, et al., 2015; Russell et al., 2009), both of which are factors associated with youth’s sense of agency, confidence, and empowerment (Poteat et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2009).

GSAs are similar to other school- and community-based groups created for and by SGM youth, and they resemble groups for youth facing other forms of marginalization and working to promote social justice (e.g., Taines, 2012). Scholars have pointed to advocacy as a means to empower youth (Morsillo & Prilleltensky, 2007; Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, 2015), and advocacy has been linked to a sense of empowerment and well-being among youth in GSAs (Maybery, 2013; Poteat et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2009). At the same time, advocacy can be time-intensive, challenging, and larger in scale than other GSA discussions or activities. One study found that whereas a large majority of youth reported socializing and emotional support in their GSA (88% and 74%, respectively), relatively fewer youth reported various advocacy activities (ranging from 13% to 54% of youth; Kosciw et al., 2020). There is further evidence that levels of youth advocacy vary significantly across GSAs to a greater extent than socializing or support activities (Poteat, Scheer, et al., 2015). Youth involved in advocacy can face hostility, leading some to feel disempowered (Godfrey, Burson, Yanisch, Hughes, & Way, 2019). As such, it is important to identify factors which could foster youth’s advocacy. Adult mentors and advisors have key roles in shaping the experiences of youth in clubs and programs (Grossman & Bulle, 2006; Zeldin, Christens, & Powers, 2013). Few studies, however, have considered advisor attributes and practices in relation to youth advocacy in GSAs.

Describing the Roles of GSA Advisors

A few studies have highlighted why some adults elect to serve as GSA advisors and have identified certain roles they play. Often, advisors are intrinsically motivated to support SGM youth, have a personal connection with SGM individuals or the community, or perceive a need for an adult to serve in this position (Graybill et al., 2015; Valenti & Campbell, 2009; Watson et al., 2010). Their roles in the group are broad, ranging from providing emotional support, co-facilitating discussions, speaking with administrators on behalf of students, to scaffolding youth’s work on GSA initiatives (Graybill, Varjas, Meyers, & Watson, 2009). Many of these roles align with those described in the broader literature on mentoring and youth-adult partnerships. This literature has highlighted how adults in these roles provide support, guidance, and aid in decision-making (Grossman & Bulle, 2006; Wong, Zimmerman, & Parker, 2010; Zeldin et al., 2013).

Apart from a descriptive understanding of some advisors’ motivations and practices, limited evidence exists on how advisor attributes and efforts might relate to youth’s experiences in their GSA, including youth’s advocacy efforts. Advisors may hold the historical memory of prior GSA advocacy successes and challenges. They may have a better understanding of school or district policies and prior experience with administrators that informs their assessment of the GSA’s ability to engage in certain advocacy efforts. In addition, advisors may provide a level of continuity that could be essential for longer-term advocacy efforts. For these reasons, we give advisors direct attention here.

Advisor Background and Supportive Resources

We consider several factors related to advisors’ backgrounds and their access to resources that may aid them in supporting youth advocacy efforts within their GSA. We first consider the how long advisors have served in their position. Newer advisors’ grasp of their GSA’s advocacy history could be limited. Some GSA events occur annually (e.g., Day of Silence, National Coming Out Day, Transgender Day of Remembrance; GLSEN, n.d.). Other efforts may require a sustained course of action over several years, such as in challenging a discriminatory school policy. Longer-serving advisors may help to sustain youth’s commitment to longer-range goals or provide continuity when youth leaders or members change. More experienced advisors may also have more confidence or knowledge of how best to support youth to take on more advocacy initiatives. Thus, we expect that youth in GSAs whose advisors have served longer in their position will report engaging in more advocacy over the school year than youth in other GSAs with newer advisors.

Although GSA advisors often evince a desire to support SGM students as motivation to serve, many report that they have not received adequate training (e.g., to cover SGM topics or to facilitate advocacy efforts; Graybill et al., 2015; Valenti et al. 2009). In one study of GSA advisors’ experiences, 42% felt that their professional training had “not at all” prepared them for their role (Graybill et al., 2015). At the same time, some advisors expressed hesitation in taking on the role due to low self-efficacy (i.e. confidence in their ability) in discussing SGM issues (Watson et al., 2010). Additionally, advisors can face challenges in their role, such as hostility from administrators to their GSA’s advocacy (Graybill et al., 2009, 2015). Advisors who have received training in their role may be more aware of how to respond to unique challenges faced by GSAs. Generally, then, GSAs whose advisors have received training may be able to do more advocacy over the school year than GSAs whose advisors have not received training.

We also consider potential differences across GSAs based on any stipend received by advisors. Albeit nominal, some advisors may direct their funds to secure resources (e.g., poster boards) or to cover costs (e.g., transportation) for certain advocacy initiatives. In contrast to inward-facing support provision to members, GSA advocacy reflects an outward-facing effort broader in scope and potentially costlier. Advisor stipends, in part, could enable some GSAs to engage in more advocacy.

In addition, we compare GSAs based on whether they have one advisor or multiple advisors. Some advocacy efforts can be time-intensive and thus require more support from advisors. Youth-led initiatives may be more feasible in GSAs which have more than one advisor.

Advisor GSA-Related Practices

In addition to differences in their tenure, training, and resources, advisors may differ in some of their demonstrated practices within their GSAs. These could relate to variability in a GSA’s level of advocacy. As one indicator, we consider the average number of hours per week advisors report devoting to GSA efforts. Again, advocacy initiatives can extend beyond the timeframe of regular meetings, sometimes spread over the course of days, weeks, or longer periods in the case of promoting policy change (Mayberry, 2013; Poteat, Scheer, et al., 2015; Russell et al., 2009). It would be important for schools to know whether GSA advocacy demands a significantly greater time commitment and expense from advisors.

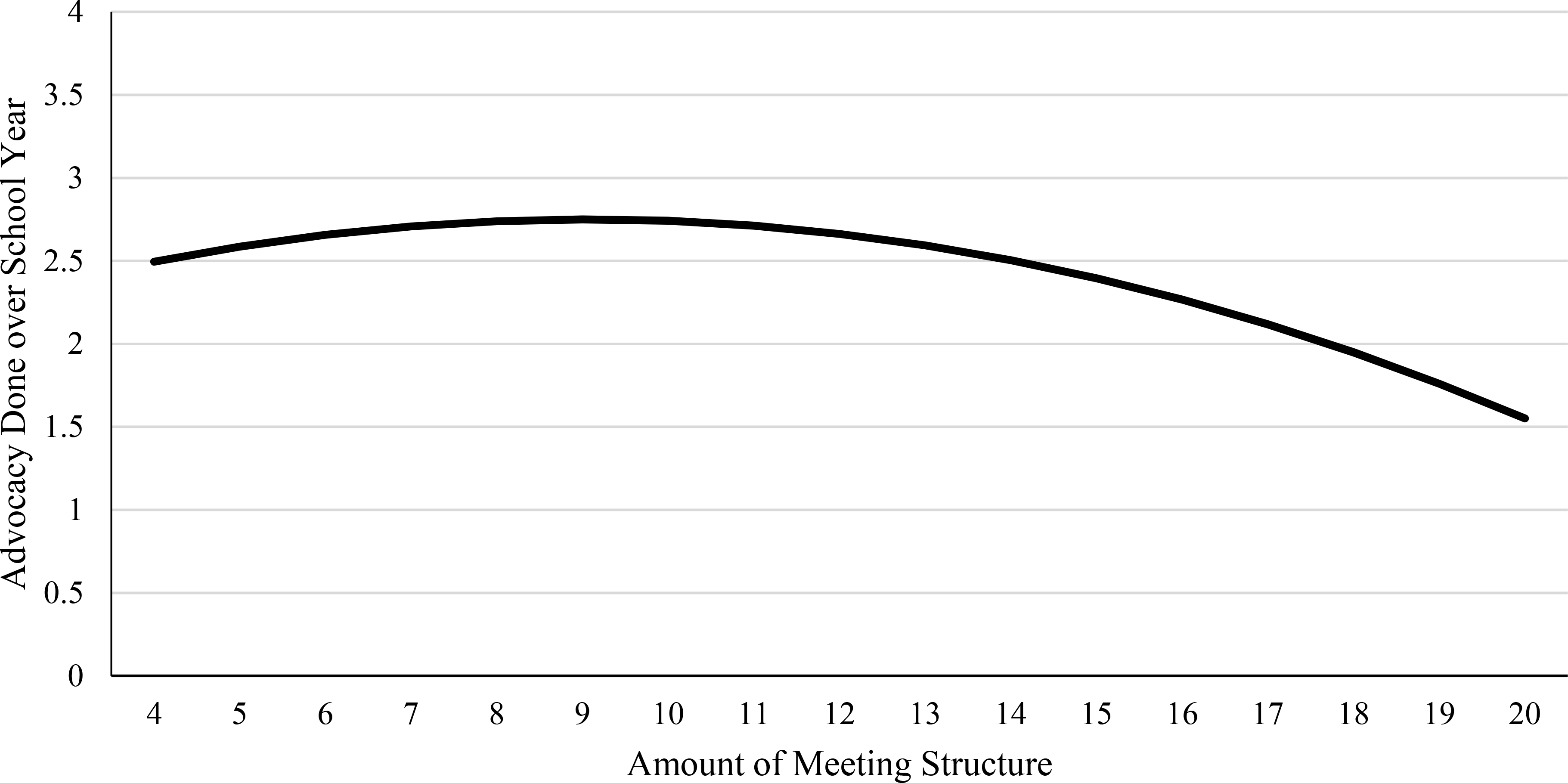

Advisors also may have some voice in determining the general structure, organization, and co-facilitation of meetings in youth settings (Wong et al., 2010). For instance, GSA meetings can be structured to include check-ins at the beginning of meetings, follow-ups on past meetings, a planned agenda, or youth or advisor facilitation or co-facilitation of meetings (Poteat, Heck, Yoshikawa, & Calzo, 2016). As stipulated in PYD frameworks, successful youth programs are characterized as having sufficient organizational structure (Catalano et al., 2004). Some GSA research also points to the importance of meeting structure. Some youth report not joining their school’s GSA due to their impression of its disorganization (Heck, Lindquist, Stewart, Brennan, & Cochran, 2013; Kosciw et al., 2020), while another study found a curvilinear relationship between meeting structure and youth’s level of engagement in the GSA (Poteat, Heck, et al., 2016). Structure was beneficial to a point, after which it was associated with lower engagement. We expect a similar pattern to emerge in the case of advocacy. Youth in GSAs whose advisors report more meeting structure may go on to engage in more advocacy than other GSAs to a point, after which high levels of structure may hamper spontaneity or flexibility and predict less advocacy over the school year.

Study Purpose and Hypotheses

Although there has been growing attention to youth’s experiences in GSAs, there has been limited focus on the adult advisors. It is unclear how advisor characteristics and practices might relate to the actions undertaken by youth in GSAs, including their involvement in advocacy. In the current study, we give direct focus to GSA advisors of 38 purposively sampled GSAs across Massachusetts and consider whether a number of advisor-related variables predict the extent to which the youth in their GSAs engage in greater advocacy over the course of the school year.

After adjusting for any initial differences in youth’s reported levels of advocacy at the beginning of the school year, we hypothesize that GSAs whose advisors have served longer in their position, have received training for their position, receive a stipend for their position, and have co-advisors will do more advocacy over the school year than other GSAs. In addition, we hypothesize that youth in GSAs whose advisors report devoting a greater number of hours per week on GSA issues and having more structure to their meetings (up to a point) will report a greater amount of advocacy over the school year than youth in other GSAs. We further consider the number of meetings held by the GSA over the year as a simple covariate in our model in order to more finely consider whether differences across GSAs might be more attributable to the fact that some GSAs simply have more meetings and time to do more activities rather than to advisor characteristics and practices.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data from the current study come from a larger project focused on youth’s experiences in GSAs. The project included 366 youth and 58 adult advisors from 38 GSAs located across the state of Massachusetts. Participants completed surveys at the beginning and end of the school year. Of these GSAs, slightly over half (n = 21) had one advisor, while 15 GSAs had two advisors, one GSA had three advisors, and one GSA had four advisors. In the current study, we draw from youth-reported data on their level of GSA-based advocacy at the beginning and end of the school year and link their data to data reported by the advisor(s) of their GSA. Demographic information for the adult advisors of these GSAs are reported in Table 1. More details regarding the youth participant sample are reported in Poteat and colleagues (2020).

Table 1.

Advisor Demographic Information

| Variable | N (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 28 (48.3) | |

| Gay or lesbian | 14 (24.1) | |

| Queer | 4 (6.9) | |

| Pansexual | 2 (3.4) | |

| Asexual | 1 (1.7) | |

| Bisexual | 1 (1.7) | |

| Respondent written: Gay/lesbian and queer | 1 (1.7) | |

| Not reported | 7 (12.1) | |

| Gender identity | ||

| Cisgender female | 38 (65.5) | |

| Cisgender male | 11 (19.0) | |

| Gender fluid | 1 (1.7) | |

| Genderqueer | 1 (1.7) | |

| Transgender | 1 (1.7) | |

| Not reported | 6 (10.3) | |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| White | 51 (87.9) | |

| Respondent written: Indian | 1 (1.7) | |

| Not reported | 6 (10.3) | |

| Age (in years) | 43.6 (10.5) |

The participating GSAs were purposively sampled in consultation with the Massachusetts Safe Schools Program for LGBTQ Students. We included GSAs in traditional public schools, public charter schools, and vocational and technical public schools that varied in their geographic diversity, population density, and in size, racial, and socioeconomic composition. Advisors provided adult consent for students to participate and consented to their own participation. Youth further assented to participate. Advisor adult consent was used over parent consent to avoid risks of outing SGM youth to parents, a common practice in SGM youth research to protect their safety (American Psychological Association, 2018). All procedures were approved by the primary institution’s IRB and each participating school.

Data collection occurred over a period of two years, with 19 different GSAs participating in each year for a total of 38 GSAs. This ensured that in each year we could visit all GSAs within a close time frame at each wave. Youth and advisors completed surveys during a regular GSA meeting, once toward the beginning of the school year (mid-September to late-October) and once toward the end of the school year (late-April to late-May). They received a $10 gift card for completing the first survey and a $20 gift card for the second survey.

Measures

Demographics.

Advisors reported their age, sexual orientation, gender identity, and race or ethnicity, with responses included in Table 1.

Advisor attributes.

At wave 1, advisors reported whether they received a stipend for their position based on the question, “Do you receive a stipend or get paid for your GSA advising position?” (coded as no = 0, yes = 1). In GSAs with more than one advisor, if any of the advisors received a stipend, the GSA was coded as having an advisor with a stipend.

At wave 1, advisors reported whether they had received advisor training based on the question, “Have you received any training specific to being a GSA advisor?” (coded as no = 0, yes = 1). In GSAs with more than one advisor, if any of the advisors had received training, the GSA was coded as having an advisor with training.

At wave 1, advisors reported how long they had served as the GSA advisor based on the question, “How long have you been an advisor for your GSA?” wherein they could report the number of months and/or years of service. We scored responses such that values represented a total duration of years. In GSAs with more than one advisor, we used the highest value among those reported by the advisors.

At wave 2, advisors reported how much time they devoted to GSA-related work based on the question, “Over this current year, in an average week, how many hours did you devote to work you considered GSA-related?” In GSAs with more than one advisor, we used the highest value among those reported by the advisors.

Number of meetings.

At wave 2, advisors reported their number of GSA meetings held since November (i.e., since our initial visit at wave 1). In GSAs with more than one advisor, if the reports among the advisors differed, we used the average of their responses.

Meeting organizational structure.

At wave 2, advisors reported the level of structure to their GSA meetings (Poteat, Heck, et al., 2016) based on the following items, preceded by the stem, “From November until now, how often did your GSA do these things” (a) We did check-ins at the beginning of GSA meetings, (b) We followed-up about things that were discussed in the last GSA meeting, (c) Our GSA meetings followed an agenda, and (d) I or a student (or students) led/co-led our GSA meetings. Response options were never, rarely, sometimes, often, or all the time (scored 1 to 5). Higher total scale scores indicated that the GSA employed a higher level of structure to their meetings. The internal reliability coefficient estimate was α = .48. In GSAs with more than one advisor, we used the average of their responses.

Youth-reported advocacy.

At waves 1 and 2, youth reported the amount of advocacy they had engaged in up to that point in the school year (wave 1) or since November (wave 2) on the 7-item advocacy subscale of the GSA Involvement Scale (e.g., “Organize school events to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues” or “Speak out for LGBTQ issues”; Poteat et al., 2016). Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (a lot), and higher average scale score indicated engagement in greater advocacy. The coefficient alpha internal reliability estimates were α = .89 (wave 1) and .88 (wave 2).

Analytic Approach

We tested our model using multilevel modeling with maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017), to adjust for the interdependence of youth nested within GSAs. Prior to considering our proposed model, we first tested an unconditional null model to determine the amount of variance across GSAs in youth’s reported advocacy over the school year (i.e., reported at wave 2). We referred to the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the proportion of total variance in advocacy that existed across GSAs. Next we tested our proposed model. All of our predictors were included at the GSA level (i.e., level 2 of the model), with the exception of youth’s wave 1 advocacy, which was included at the individual and group level (i.e., to adjust for initial variability in advocacy among youth in the same GSA [level 1] and for initial variability in advocacy across GSAs [level 2]). Youth’s level of advocacy at wave 2 was included as the dependent variable in the model. To consider the potential curvilinear association between the degree of meeting structure and advocacy over the school year, we included the linear and quadratic effects of meeting structure as predictors in the model. The full model is presented below:

Results

Before proceeding to test our multilevel model of interest, we present various descriptive data for the GSAs and GSA advisors. Most GSAs had an advisor who received a stipend for their advisory role (81%). However, only slightly more than half of the GSAs (57.9%) had an advisor who had ever received any training. Of note, there was a wide representation among advisors in their time served in this role, ranging from two months to 25 years. On average, advisors had served about five years in their role (M = 5.01 years, SD = 5.61). Advisors also varied in the amount of time per week that they devoted to their advising role, ranging from 30 minutes to 13.50 hours. On average, advisors reported devoting a bit over 2.5 hours per week to their role (M = 2.66 hours, SD = 2.14). GSAs also varied in their total number of meetings held between November and the school year’s end, ranging from five meetings to 28 meetings, with an average of about 17 meetings (M = 17.61 meetings, SD = 6.80). Finally, the amount of meeting structure varied across GSAs, ranging from scores of 8 (which would align with marking “rarely” for all four indicators of meeting structure) to 19 (which would align with marking “all the time” for all four indicators of meeting structure), while across GSAs the total score averaged around a score of 15 (M = 15.13, SD = 2.38).

Moving to our multilevel analyses, the results of our initial null model indicated that GSAs varied significantly from one another in the amount of advocacy youth had done over the school year (level 1 variance = 0.93, p < .001; level 2 variance = 0.10, p = .04; ICC = 0.10). We then tested our full model with our set of independent variables, the results of which are reported in Table 2. As hypothesized, after adjusting for initial levels of advocacy at wave 1 and the number of meetings held over the school year, youth in GSAs whose advisors had served for longer durations (γunstand. = 0.021, γstand. = 0.359, p = .001) and devoted more time per week to their advising role (γunstand. = 0.104, γstand. = 0.443, p = .007) reported greater relative increases in their advocacy over the school year. Also as hypothesized, we found evidence of a curvilinear association between the degree of meeting organizational structure and advocacy done over the year (see Figure 1), again adjusting for initial levels of advocacy at wave 1 and the number of meetings held over the year. As shown in the figure, a greater amount of meeting structure predicted greater advocacy done by the GSA up to a point, after which higher levels of structure predicted less advocacy done by the GSA. Contrary to our hypotheses, the relative change in a GSA’s level of advocacy over the school year was not associated with whether their advisors had received a stipend or training, or whether the GSA had more than one advisor. Our model accounted for 22% of the variance among individual youth based on their initial advocacy reported at wave 1 (R2 = .22 at level 1) and most of the variance across GSAs after including all our variables of interest at that level (R2 = .97 at level 2). The remaining variance across GSAs was no longer statistically significant (residual level 2 variance = 0.03, p = .86).

Table 2.

Predicting Relative Change in Advocacy among GSAs Reported at School Year End

| Predictor Variables | Unstandardized Coefficient (95% CI) |

Standardized Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | ||

| Initial individual advocacy | 0.492*** (0.391, 0.594) |

0.467 (0.383, 0.551) |

| Level 2 | ||

| Initial collective advocacy | 0.905*** (0.451, 1.358) |

0.785 (0.492, 1.079) |

| Number of advisors | 0.019 (−0.191, 0.229) |

0.029 (−0.286, 0.343) |

| Stipend received | −0.104 (−0.367, 0.160) |

−0.117 (−0.407, 0.173) |

| Any training received | 0.116 (−0.033, 0.266) |

0.174 (−0.057, 0.406) |

| Years as advisor | 0.021** (0.008, 0.034) |

0.359 (0.067, 0.650) |

| Hours/week in advisor role | 0.104** (0.029, 0.180) |

0.443 (0.148, 0.737) |

| Number meetings over year | 0.017** (0.006, 0.028) |

0.341 (0.114, 0.569) |

| Amount of structure | 0.181* (0.011, 0.351) |

1.323 (−0.019, 2.666) |

| Amount of structure (squared) | −0.010** −0.017, −0.003) |

−2.043 (−3.597, −0.490) |

Note. Values are unstandardized and standardized coefficient estimates, with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) in parentheses.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Figure 1.

Curvilinear association between the degree of structure to GSA meetings and GSAs’ level of advocacy done over the school year.

Discussion

Our current findings build upon extant GSA research to give greater focus to how advisor attributes and practices predict youth’s advocacy over the school year. We found that GSAs varied significantly in their members’ level of advocacy done over the school year. Furthermore, youth in GSAs whose advisors reported longer years of service, devoting more time to GSA efforts each week, and employing more structure in GSA meetings (up to a point), reported greater relative increases in advocacy over the school year (adjusting for initial levels of advocacy at the beginning of the year and the total number of GSA meetings that year). Our findings underscore the need for GSA research, as well as research on other social justice-oriented groups, to give greater attention to adult advisors and how they work in partnership with youth to promote youth’s advocacy efforts.

Variability in the Attributes of GSA Advisors

The adult advisors of GSAs in the current study differed from one another in several ways, akin to other GSA studies documenting variability among youth members (Griffin et al., 2004; Poteat, Yoshikawa, et al., 2015). The range of advisors’ years of service in their position and the amount of time each week they devoted to it were notable. As with youth, advisors likely contend with a range of responsibilities outside of the GSA that could affect their ability to devote time to GSA-related issues or to serve as an advisor over multiple years. It would be useful for future research to identify factors that may affect the extent to which advisors are able to serve in their role (from week to week or over school years), because, as we later note, these two factors were associated with the amount of advocacy that youth engaged in over the school year. There was less differentiation among advisors in their receipt of a stipend for their position. The availability of a stipend and its amount could depend on district policies or union negotiations, which can be subject to change. Still, it would be useful for future research to consider how advisors view or use their stipends, as well as their own personal funds, as this financial resource could make a peripheral yet important contribution to the GSA’s functioning. From our own visits, some advisors anecdotally reported using their stipend or their own money for snacks, which attracted members to attend meetings.

Striking—given the average length of service among advisors of five years—was our finding that only somewhat more than half had received any type of training for their position. Still, although our findings may be reflective of Massachusetts, they add to prior reports from advisors located in various other U.S. regions, among whom 42% did not feel prepared for their role (Graybill et al., 2015). Adults fill multiple roles in youth settings, such as providing guidance and mentoring (Graybill et al., 2015; Rhodes & DuBois, 2008; Wong et al., 2010). In GSAs, these roles could be important, while also challenging, given the concerns that youth raise in meetings (e.g., chronic peer harassment, family rejection; Poteat et al., 2017) and the unique barriers that GSAs and other social justice-oriented clubs face when engaging in advocacy (Watson et al., 2010). Also, youth may be required to have an adult advisor designated and present for a school-based club to be formed, yet it may be difficult for youth in some schools to identify an SGM-affirming adult. Adults in this role may be selected for varying reasons and hold varying levels of expertise related to the club’s purpose. Such challenges for GSAs could extend to other social justice-oriented clubs. Thus, professional development for advisors of these clubs could be a key area of focus in future work. Advisors may benefit from learning ways to support and mentor SGM youth, how to respond to instances of discrimination, or how to scaffold or promote youth advocacy.

Predicting Variability Across GSAs in their Advocacy

GSAs varied in their members’ level of advocacy, as found in other studies (Poteat, Scheer, et al., 2015). As a significant extension of prior work, we identified advisor attributes and their GSA practices that accounted for this variability in advocacy across GSAs. Among the strongest predictors were advisors’ years of service and the amount of time they devoted to their position each week. Advisors with longer service in the GSA may have been able to draw from their past GSA-related experiences to anticipate challenges or feel more confident supporting and guiding youth in a range of advocacy efforts. Advisors’ years of experience may have benefited youth when completing annual advocacy and awareness-raising initiatives (e.g., National Coming Out Day, Transgender Day of Remembrance; GLSEN, n.d.). Also, longer-serving advisors may have had better knowledge of school policies or politics that could either support or hinder youth’s advocacy efforts, as some GSA advisors have reported pushback from their administrators (Graybill et al., 2015; Valenti et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2010). Other school-based groups oriented around social justice, such as Black Student Unions advocating for racial justice, have faced similar pushback from administrators and school systems (Cammarota, 2016). Although we did not ask how long advisors had worked at their school (as opposed to how long they had been GSA advisors), longer tenure at a school could influence an advisor’s familiarity with the school’s history vis à vis student advocacy. Conversely, an advisor who is new to a school might be wary to assume the risks which may come with advocacy or may have less social capital to advance it. Our findings suggest the importance of having at least one advisor in GSAs and similar groups who can leverage their historical and institutional knowledge and experience in the school and in these groups.

It is also noteworthy that, beyond their years of service as advisors, the amount of time advisors devoted to GSA efforts from week to week was significantly associated with a GSA’s greater advocacy over the school year. Notably, this association was significant even when adjusting for the varying number of meetings that GSAs held over the year. Advisors’ close involvement in supporting youth’s advocacy may have been important in order to ensure youth’s ability to sustain their actions over time. Advisors have reported speaking with administrators on behalf of students, managing certain planning efforts, and scaffolding youth’s work (Graybill et al., 2009, 2015). These efforts may have been more time-intensive for advocacy initiatives, whether because they faced more pushback than other types of activities (e.g., bake sales, movie screenings) or because their scale required more resources or individuals to pursue them. This finding speaks to how the level of time investment of GSA advisors ties directly to certain experiences (i.e., advocacy) that youth report in their GSAs. It would be useful for future research to consider how advisors of GSAs and similar social justice-oriented groups use their time to support youth’s advocacy. Moreover, it would be important for school administrators to recognize the time commitment of advisors to these groups. Advisors of GSAs and similar school-based groups carry other primary responsibilities (e.g., as teachers, nurses, school counselors), and their contribution and service within these groups could go under-recognized in their evaluations.

We did not find that advisors’ receipt of a stipend predicted youth’s relative increase in advocacy over the school year. In our discussions with GSA advisors from this study, some reported anecdotally that they used their stipend for GSA-related purchases, such as for snacks or supplies. Although advocacy initiatives can be potentially costlier than support or socializing efforts, advisor stipends may not have predicted greater advocacy because the stipend amount may have been nominal and was not intended directly for the GSA or because GSAs also may have engaged in separate fund-raising efforts to cover costs of certain advocacy efforts.

Similarly, advisors’ reported receipt of training for their role was not a significant predictor of youth’s reported advocacy in their GSAs. Still, future research should attend to this factor with greater nuance. The broader youth program literature has suggested that professional development for adults in these settings can carry significant benefits such as in promoting closer youth-adult relationships (Arnold & Sillman, 2017; Grossman & Bulle, 2006; Vance, 2012). Although there was a fairly even split between advisors who had or had not received any training, it may be more important to consider the number of trainings advisors receive, their recency, quality, and whether training may benefit some advisors more than others (e.g., new advisors versus longer-serving advisors). Also, advisors without training may have been able to consult informally with others or draw from their own prior experiences of successes and challenges in order to encourage youth’s advocacy efforts. Finally, training for advisors may be more important in fostering their skills to support youth on some types of advocacy than others.

As we hypothesized, there was a curvilinear association between the degree of meeting structure and the extent of GSA advocacy over the school year. This finding aligns with a tenet in PYD frameworks that sufficient structure is essential in youth programs (Catalano et al., 2004). Our finding builds upon work showing that youth’s perceptions of organization in their GSA informs their level of involvement (Heck et al., 2013; Poteat, Heck, et al., 2016). In our study, GSAs that employed some of these structural strategies may have been able to better organize around advocacy efforts that involved individuals with different roles and responsibilities and requiring multiple meetings to plan. Given the challenges of advocacy (Godfrey et al., 2019) and the hostility that some groups organized around social justice can face in their efforts (Cammarota, 2016; Graybill et al., 2015), greater structure could have sustained youth’s investment and hopefulness through possible setbacks or hostile outside responses.

At a certain point, however, structure may have created a degree of inflexibility that prevented other opportunities from arising organically. Although structure and scaffolding are important aspects of PYD-informed programs, so are opportunities for youth autonomy (Catalano et al., 2004). If too much structure inhibited these opportunities, its benefits (e.g., promoting more advocacy) may have been diminished. As an example, whereas we assessed the extent to which meetings had designated leaders—whether advisors or youth—we assessed this in a single item. It would be important for future work to consider how youth and advisors may distribute or balance their leadership responsibilities, as meetings led predominantly by advisors could diminish youth’s sense of empowerment and potential to engage in advocacy. Also, some common GSA practices (e.g., check-ins or follow-ups) may have surfaced concerns among members that led the GSA to focus less on advocacy and more on member support. Given that providing support is a major aim of GSAs (Griffin et al., 2004), it would be useful for future research to consider how elements of meeting structure affect GSA efforts more broadly, whether related to advocacy, support, or other endeavors.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Although the current study offers a greater understanding of certain advisor attributes and practices which could underlie youth’s greater engagement in advocacy, there are several limitations to note. Our data from two time points can begin to address directionality of associations, but they are correlational and do not imply causality. Also, advisor training was assessed with a single item; a multi-item measure would have provided more substance and nuance as to the potential association between advisor training and youth advocacy. The internal reliability of our measure of meeting structure was low, potentially due to the relatively small sample of respondents on which it is based or perhaps because some GSAs pick and choose certain structural approaches to use more frequently. Also, as noted earlier, one of the items assessed the frequency of student- and advisor-led meetings with a single item. Given our findings for this construct, future research should consider other more robust measures of meeting structure in order to disentangle specific strategies that are most effective. In addition, although we purposively sampled our GSAs to increase their diversity along multiple indicators, they were all located in Massachusetts, a state that is relatively more progressive than others. It is possible that GSAs vary even more substantially on advocacy when compared across a wider geography and range of political contexts. It is also possible that a unique set of advisor attributes underlie youth advocacy in GSAs located in more conservative communities. It would be important to consider broader contextual factors (e.g., attributable to the school, community, or state) that promote or inhibit advocacy in GSAs and other social justice-oriented groups.

Finally, although we purposively sampled GSAs for diversity in the racial/ethnic composition of their schools, with some GSAs in majority-minority schools, almost all GSA advisors who reported their race or ethnicity identified as White. Notably, our percentage of White advisors (87.9%) was nearly identical to the percentage of White advisors in an earlier descriptive study of several hundred GSA advisors surveyed nationally (85.7%; Graybill et al., 2015). This underscores the need for research to give focus to GSA advisors of color in order to identify potentially unique experiences and challenges in their advising role and with attention to how intersectionality issues may arise for them and their youth members (e.g., in facing multiple forms of oppression or in benefitting from different constellations of privilege). On the one hand, GSA advisors of color may have more experience and proficiency with social justice advocacy; on the other, they may face more pushback than their White colleagues.

Our study also carries several strengths. It is one of few studies not only to give direct attention to the adult advisors of GSAs but also to directly connect advisor attributes and practices to variability in youth’s GSA experiences. In doing so, we used multi-informant data from advisors and youth and moved from a primarily descriptive characterization of advisors to further consider how their attributes predict youth’s GSA experiences. Also, we moved beyond the cross-sectional design of most other GSA studies to consider youth and advisor data gathered at the beginning and end of the school year. This allowed us to adjust for youth’s initial levels of advocacy and to provide a more rigorous test of the extent to which advisor factors predicted relative change in youth’s advocacy during the school year.

Our study brings a greater focus to youth advocacy in the context of GSAs and to how certain advisor attributes and practices could facilitate these efforts. Given their presence in an increasing number of schools across the United States (CDC, 2019), GSAs provide a setting for a growing number of youth to come together to engage in collective action against discrimination and to promote justice for those in the SGM community. It will be important for ongoing research to identify ways to support youth and their adult advisors as they work together to take on advocacy initiatives.

Acknowledgments

Author Note: Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MD009458 (Principal Investigator: V. Paul Poteat; Co-Investigators: Jerel P. Calzo and Hirokazu Yoshikawa). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Support for Sarah B. Rosenbach was provided through a Predoctoral Interdisciplinary Research Training Fellowship from the Institute of Education Sciences (R305B140037).

Contributor Information

V. Paul Poteat, Boston College.

Michael D. O’Brien, Boston College

Megan K. Yang, Boston College

Sarah B. Rosenbach, New York University

Arthur Lipkin, Cambridge, MA.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

- Akiva T, Carey RL, Cross AB, Delale-O’Connor L, & Brown MR (2017). Reasons youth engage in activism programs: Social justice or sanctuary? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 53, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2018). APA resolution on support for the expansion of mature minors’ ability to participate in research. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/resolution-minors-research.pdf

- Arnold ME, & Silliman B (2017). From theory to practice: A critical review of positive youth development program frameworks. Journal of Youth Development, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Camino LA (2000). Youth-adult partnerships: Entering new territory in community work and research. Applied Developmental Science, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota J (2016). The praxis of ethnic studies: Transforming second sight into critical consciousness. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19, 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JA, Lonczak HS, & Hawkins JD (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591, 98–124. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey EB, Burson EL, Yanisch TM, Hughes D, & Way N (2019). A bitter pill to swallow? Patterns of critical consciousness and socioemotional and academic well-being in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 55, 525–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybill EC, Varjas K, Meyers J, & Watson LB (2009). Content-specific strategies to advocate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: An exploratory study. School Psychology Review, 38, 570–584. [Google Scholar]

- Graybill EC, Varjas K, Meyers J, Dever BV, Greenberg D, Roach AT, & Morillas C (2015). Demographic trends and advocacy experiences of gay–straight alliance advisors. Journal of LGBT Youth, 12, 436–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hanasono LK, Broido EM, Yacobucci MM, Root KV, Peña S, & O’Neil DA (2019). Secret service: Revealing gender biases in the visibility and value of faculty service. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Lindquist LM, Stewart BT, Brennan C, & Cochran BN (2013). To join or not to join: Gay-straight student alliances and the high school experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 25, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y (2016). The role of youth engagement in positive youth development and social justice youth development for high-risk, marginalised youth. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 21, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Clark CM, Truong NL, & Zongrone AD (2020). The 2019 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Marx RA, & Kettrey HH (2016). Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1269–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry M (2013). Gay-straight alliances: Youth empowerment and working toward reducing stigma of LGBT youth. Humanity & Society, 37, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Morsillo J, & Prilleltensky I (2007). Social action with youth: Interventions, evaluation, and psychopolitical validity. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Calzo JP, Yoshikawa H, Lipkin A, Ceccolini CJ, Rosenbach SB, … & Burson E (2020). Greater engagement in Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs) and GSA characteristics predict youth empowerment and reduced mental health concerns. Child Development, 91, 1509–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Calzo JP, & Yoshikawa H (2016). Promoting youth agency through dimensions of gay–straight alliance involvement and conditions that maximize associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1438–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Heck NC, Yoshikawa H, & Calzo JP (2016). Greater engagement among members of Gay-Straight Alliances: Individual and structural contributors. American Educational Research Journal, 53, 1732–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Scheer JR, Marx RA, Calzo JP, & Yoshikawa H (2015). Gay-Straight Alliances vary on dimensions of youth socializing and advocacy: Factors accounting for individual and setting-level differences. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 422–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Yoshikawa H, Calzo JP, Gray ML, DiGiovanni CD, Lipkin A, … & Shaw MP (2015). Contextualizing Gay-Straight Alliances: Student, advisor, and structural factors related to positive youth development among members. Child Development, 86, 176–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Yoshikawa H, Calzo JP, Russell ST, & Horn S (2017). Gay-Straight Alliances as settings for youth inclusion and development: Future conceptual and methodological directions for research on these and other student groups in schools. Educational Researcher, 46, 508–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, & DuBois DL (2008). Mentoring relationships and programs for youth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, & Laub C (2009). Youth empowerment and high school gay-straight alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 891–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornaiuolo A, & Thomas EE (2017). Disrupting educational inequalities through youth digital activism. Review of Research in Education, 41, 337–357. [Google Scholar]

- Taines C (2012). Intervening in alienation: The outcomes for urban youth of participating in school activism. American Educational Research Journal, 49, 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti M, & Campbell R (2009). Working with youth on LGBT issues: Why gay–straight alliance advisors become involved. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 228–248. [Google Scholar]

- Vance F (2012). An emerging model of knowledge for youth development professionals. Journal of Youth Development, 7, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wagaman MA (2016). Promoting empowerment among LGBTQ youth: A social justice youth development approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Watson LB, Varjas K, Meyers J, & Graybill EC (2010). Gay–straight alliance advisors: Negotiating multiple ecological systems when advocating for LGBTQ youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 7, 100–128. [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, & Hipolito-Delgado CP (2015). Thinking ourselves to liberation? Advancing sociopolitical action in critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47, 847–867. [Google Scholar]

- Wong NT, Zimmerman MA, & Parker EA (2010). A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 100–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin S, Christens BD, & Powers JL (2013). The psychology and practice of youth-adult partnership: Bridging generations for youth development and community change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51, 385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.