Abstract

There are known cultural variations in correlates of and symptoms related to suicide-related thoughts and behaviors; however, the majority of research that informs suicide prevention in school systems has focused on research based on Euro-American/White students. By exploring school-related risk and protective factors in ethnic-racial minoritized students, we expand existing multicultural models of suicide prevention for school settings. Specifically, this systematic literature review identified 33 studies conducted with American Indian and Alaskan Native, Hispanic and Latinx, Black and African American, and Asian American and Pacific Islander students. Findings underscore the importance of building relationships with the school community and fostering a sense of safety for students, the need to approach school-based suicide prevention and intervention with cultural considerations, and the importance of connecting students and families with providers in culturally sensitive and informed ways. Taken together, schools need to build school-family-community partnerships that promote culturally sensitive approaches to suicide prevention.

Keywords: Suicide, Community-School Collaboration, Family-School Collaboration, Ethnicity, Social Justice

Introduction

Schools have long been advocated as an ideal place to house suicide prevention programs (Singer et al. 2018; Surgenor et al. 2016). Schools have the potential to foster positive student and teacher relationships and provide a safe environment to protect against suicide (Marraccini & Brier, 2017); however, they can also inadvertently exacerbate risk for suicide by way of negative experiences such as bullying and academic stress (Holt et al., 2015; Walsh & Eggert, 2007). Despite variations in suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (STB) across cultural, racial, and ethnic groups, the majority of research and theory used to guide our understanding of suicide is based on samples of predominately Euro-American/White populations (Lorenzon-Lucas & Phillips, 2014).

Death by suicide in children and adolescents of all racial and ethnic backgrounds has increased over the past decade (Curtin & Heron 2019). The highest rates of suicide deaths in individuals ages 5–18 have been found in non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives, with 9.7 deaths per 100,000 youth from 2009 to 2018, followed by non-Hispanic White children and adolescents (3.8 deaths per 100,000; Curtin & Hedegaard, 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], n.d.). Hispanic and Latinx children and adolescents have been estimated to die by suicide at lower rates than non-Hispanic youth over the past decade (2.1 compared to 3.4 per 100,000), with rates comparably low among non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islanders (2.1 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic Black and African Americans (2.0 per 100,000; CDC, n.d.). Suicide deaths in Black children, however, have been increasing in recent years (Lindsey et al., 2019). While the high rates of suicide deaths in American Indian/Alaska Native youth are compounded by a federal system of severely underfunded mental health care, mental health problems, chronic pain, and historical and systemic trauma (e.g., Tucker et al., 2016; Wexler, 2012), the lower rates in other racial/ethnic (R/E) minoritized youth are likely compounded by misclassifications that occur during cause of death ascertainment procedures. That is, suicide misclassifications (i.e., the erroneous identification of a suicide as an injury of undetermined death) are significantly more likely to occur in Black and Hispanic deaths compared to White deaths, resulting in underestimates of the prevalence of suicide (Rockett et al., 2010).

Rates of self-reported suicide attempts have also been declining in many R/E minoritized groups over the past few decades (Lindsey et al. 2019). Results from the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), however, indicate that the percentage of Hispanic youth contemplating suicide slightly exceeded the average rate observed across groups (17.7%). Additionally, a greater proportion of Hispanic adolescents (18.8%) reported seriously considering suicide compared to Black adolescents (14.5%; Kann et al. 2016) and suicide attempts among Black adolescents have actually been increasing in recent years (Lindsey et al. 2019). Moreover, sexual minoritized youth identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ) appear more at-risk for suicide; however, risk may vary based on racial and ethnic background, indicating the need to consider intersectionality when examining suicide data (Bostwick et al., 2014).

In addition to differences in rates of STB between R/E minoritized groups, there is also variability in predictors of suicide and cultural sanctions around the acceptability of suicide (Goldston et al. 2008). Predictors of suicide often reflect characteristics of individuals or systems that may increase or decrease the likelihood of STB (Tucker et al. 2015). Systemic racism and racial discrimination are systems-level stressors that can precipitate psychological difficulties, increasing risk for suicide (Assari et al. 2017) and serving as a barrier to treatment seeking (Goldston et al. 2008) in Black individuals. Acculturative stress has been identified as a risk factor for suicide in Hispanic communities (Silva & Van Orden 2018) as well as an important factor for understanding suicide risk in Asian American youth (Wyatt et al., 2015). At the individual level, the potential for hidden suicidal ideation (i.e., concealment of suicidal distress) is another important consideration when assessing risk of R/E minoritized individuals (Chu et al. 2018). Preliminary research identifies Asian Americans among the least likely to receive treatment for suicidal ideation (Nestor et al. 2016). Although a number of prevention programs tailored to the cultural heritage of specific American Indian tribes have shown promising results, differences in cultural traditions between tribes greatly limit the generalizability of any single program (Goldston et al. 2008). This cultural variability negates the “one size fits all” approach to addressing suicide in school and signifies the critical need to distinguish risk and protective factors for varying R/E groups. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to explore school-related risk and protective factors of STB across diverse R/E minoritized groups of students to inform a culturally relevant model of suicide prevention in schools.

School Context and Suicide Prevention

There are important considerations regarding the ways in which schools have treated R/E minoritized students and families. Historically, American Indian students were forced to attend off-reservation boarding schools, with efforts focused on assimilation severely and negatively impacting their mental health (Burnette et al., 2016). Oppression of students of color permeates educational settings through language barriers, discrimination, and low teacher expectations (Montoya-Ávila et al., 2018). Black, Hispanic, and American Indian youth receive aggressive school disciplinary actions at disproportionate rates relative to their White and Asian American counterparts (Wallace et al., 2008). Moreover, referrals for mental health services are disproportionate based on race (Guo et al., 2014), with racial and ethnic disparities in access to outside care following risk assessments in school (Cummings et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018).

As schools integrate comprehensive suicide prevention programs into their curricula and attend to malleable school-related risk and protective factors of suicide, there is a critical need to consider implications for racially and ethnically diverse student bodies. Unfortunately, existing frameworks for addressing suicide in schools have given very little attention to specific cultural factors beyond indicating a need for further exploration (Singer et al., 2018). Research identifying school-related factors that may influence STB, such as school connectedness, bullying victimization, and difficulties with academics, has also infrequently disaggregated results by R/E groups or accounted for intersectionality of racial, ethnic, sexual and gender identities (e.g., Holt et al., 2015; Marraccini & Brier 2017). Missing from this research is a focus on cultural considerations pertaining to school-related risk and protective factors of suicide, as well as a deeper understanding of their variability across R/E minoritized groups.

Theoretical Framework

The significance of school-related factors for protecting against STB in R/E minoritized students can be situated in some of the most prominent theories of suicide risk. Specifically, ideation-to-action frameworks (e.g., integrated motivational-volitional theory, Dhingra et al., 2016; the three-step theory of suicide, Klonsky & May, 2015; and the interpersonal theory of suicide [IPT], Van Orden et al., 2010) are empirically supported theories that explain how individuals shift from experiencing thoughts of suicide (ideation) to engaging in risk behaviors such as suicide attempts (action). They contend that (1) the development of suicidal ideation, and (2) the shift from ideation to attempt, are distinct processes with different contributing factors (Klonsky et al., 2018). The first ideation-to-action theory, IPT, has received perhaps the most attention and has had substantial influence on contemporary understanding of suicide risk (Klonsky et al., 2018). IPT identifies diminished feelings of belongingness as well as perceived burdensomeness to others as proximal risk factors, with hopelessness regarding these states as a key precursor to suicidal ideation (Van Orden et al., 2010). Individuals are believed to move from ideation to attempt as their fear of death diminishes and their pain tolerance increases (i.e., they acquire capability for suicide; Van Orden et al., 2010).

While IPT has been extensively studied, the majority of empirical support is drawn from studies conducted with White individuals. In a recent meta-analysis exploring IPT, a total of 63% of the participants across 122 samples were White (Chu et al., 2017; Opara et al., 2020). Recent adaptations of IPT, however, have explored models that address suicide risk in R/E minoritized groups. In American Indian populations, O’Keefe and colleagues (2014) found that perceived burdensomeness, as well as the interaction of burdensomeness and thwarted belongness, predicted suicidal ideation, while thwarted belongingness alone did not. Wyatt et al. (2015) described how suicidal ideation in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities may stem from unmet interpersonal needs resulting from a clash of Western values of individualism with Asian American values of collective identity. Opara and colleagues (2020) provided an integrated framework drawing from IPT, intersectionality theory, and the bioecological model to underscore the impact of interacting systems variables, such as systemic oppression, racism, and marginalization, as risk factors for suicide among Black children. The authors contended that Black youth may experience psychological factors of IPT (burdensomeness, thwarted belonginess, hopelessness) within a broader bioecological system (e.g., society, community, school, immediate environment) characterized by unique and intersecting risk factors that contribute to suicide risk (Opara et al., 2020). Similarly, Silva and Van Orden (2018) proposed that, for Hispanic individuals, increased acculturative stress may reduce participation in culturally-valued social activities (e.g., familism, religion, and cultural traditions), thereby decreasing feelings of belonging and leading to suicidal ideation.

This emphasis on acculturative stress has also been integrated into Chu and colleagues’ (2010) Cultural Theory and Model of Suicide, which describes three principles that may apply to R/E minoritized groups: (1) culture determines how individuals express suicidality, including methods for suicide attempts (identified as “idioms of distress”); (2) culture influences the types of stressors leading to suicide, with specific cultural risk factors proposed: cultural sanctions (i.e., acceptability or unacceptability of suicide); minority stress (i.e., stress experienced in relation to minoritized status and discrimination exposure); and social discord (i.e., lack of social connection to family, community, or friends); and (3) cultural meanings of stressors and suicide impact tolerance for psychological pain and subsequent STB. These culture-specific stressors also interact with other risk and protective factors, given that multiple pathways can lead to suicide.

Drawing from previous research on the effects of school-related variables on suicide, we aimed to develop a more nuanced understanding of how these multicultural theories of suicide prevention can be adapted for school settings. Issues pertaining to idioms of distress, including cultural variability in signs and symptoms of suicide, have direct implications for school practice regarding risk assessment procedures and comprehensive suicide prevention programs (e.g., Chu et al., 2018; Goldston et al., 2008). Cultural sanctions around suicide and mental health may influence students’ willingness to disclose suicidal ideation and their help-seeking behaviors (Goldston et al., 2008). Moreover, school experiences, such as negative teacher expectations, stereotypes, and discrimination, may contribute to minority stress and a sense of disconnectedness and social discord (e.g., Voight et al., 2015). We also believe schools can mitigate minority stress by embracing cultural differences and fostering social connection by way of positive peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, home-school-community relationships, and overall feelings of school connectedness. Thus, a review synthesizing literature related to school-specific risk and protective factors in R/E minoritized groups has important implications for preventing suicide in schools.

Purpose of Current Review

In order to fill a significant gap in the literature (i.e., that most research on the relations between school factors and STB has failed to consider racial and ethnic diversity), the purpose of this systematic review was to: (1) identify school-related factors influencing STB in R/E minoritized students; and (2) draw from these findings to expand previous cultural models of suicide by explicitly addressing school factors related to suicide. Drawing from ideation-to-action frameworks (e.g., Klonsky et al., 2018) and Chu et al.’s (2010) Cultural Theory and Model of Suicide, we hypothesized that R/E minoritized youth would have specific school-related protective (e.g., connectedness) and risk (e.g., bullying, acculturative stress) factors for STB that inform a more comprehensive approach to addressing their needs in schools.

Methods

The systematic search and retrieval process was conducted using a standardized protocol guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009). It was part of a larger review exploring school-related risk and protective factors of STB in both R/E and sexual minoritized youth. Although we present methods for the larger review, results pertaining to sexual minoritized youth (currently in analysis phase) are not presented here. The current study is focused only on R/E minoritized youth.

Peer reviewed, published articles examining school constructs and suicide-related outcomes in ethnic, racial, and sexual minoritized students were identified using key terms that were refined according to pilot searches and feedback from the first author’s university librarian. Comprehensive searches were performed in PsycINFO, PubMed, Academic Search Premier, ERIC, and Education Full Text using combinations of search terms within three areas: a) suicide-related thoughts and behaviors; b) school; and c) racial, ethnic, and sexual minoritized groups. Search terms for R/E minoritized groups focused on American Indian/Alaskan Native, Hispanic/Latinx, Black/African American, Asian American/Pacific Islander, and Arab American/Muslim American youth. Articles were also selected from the following literature reviews focused on R/E minoritized groups: Burnette et al., 2016; Hooper et al., 2016; Planey et al., 2019; Wyatt et al., 2015). (For a list of specific search terms and the review articles selected to identify articles exploring sexual minorized youth please see Supplementary Materials.)

Abstracts were reviewed by three of the authors (first, fifth, and sixth) and a trained research assistant. For this review focused on R/E minoritized youth, we examined titles, abstracts, and full texts and selected final studies based on the following eligibility criteria:

The study used a direct assessment of STB such as suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide attempts, or suicide deaths;

The study examined a school-related construct (e.g., school connectedness, bullying, school relationships) in relation to STB. Although studies of services and programs routinely integrated in schools (e.g., special education services) were included, explorations of manualized interventions were excluded, given our focus on risk and protective factors;

The study either (a) examined STB within a R/E minoritized sample or (b) compared differences between R/E minoritized students and students of other racial and ethnic backgrounds (i.e., either comparing between R/E minoritized groups or comparing R/E minoritized groups to European American/White groups);

The study included either a (a) K-12 sample or (b) adult sample with measures of school experiences captured retrospectively (case studies were excluded);

The study was published either electronically or in print between 1999 and 2019;

The study was published in English and conducted in the U.S.

Three of the authors (first, fifth, and sixth) extracted data into a predetermined, standardized coding manual that identified the study’s sample, sampling method, school and suicide-related constructs and measures, and key findings. Findings were organized into categories according to the school-related constructs they described. These categories included: in-school bullying experiences; school safety; school connectedness; academics; school programs and policies; behavior; and other (see Supplementary Materials for detailed descriptions of each category). Studies examining topics across multiple categories or multiple R/E minoritized groups are presented separately for each category or group. Study information and key findings, displayed in Table 1 and Supplementary Materials (Table S1), were checked for accuracy by the first, fifth, and sixth author. Effect sizes are presented when available and interpreted according to general rules of thumb (i.e., small odds ratio [OR] = 1.52, medium OR = 2.74, or large OR = 4.72; Chen et al., 2010), with consideration of indicators of precision and variability (e.g., confidence intervals; Durlak, 2009).

Table 1.

Included Studies Exploring Culturally Specific School-related Factors and Suicide

| Study | Sample sizea | R/E Minoritized Backgroundb | Dataset/sampling method | Grade, School Level, or Age | Location | School Construct(s) | STB Measurec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett & Joe (2015) | 2626 | African American (n = 1116); Latino (n = 1510) | 2004 Centers for Disease Control Youth Violence Survey | Grades 7, 9, 11, 12 | Northeastern US | Connectedness | SA: Past year (4 items, NR) |

| Borowsky et al. (1999) | 11666 | American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 11666) | 1990 National American Indian Adolescent Health Survey | Grades 7–12 | US (national sample) | Connectedness; Academics; Behavior; Programs; Other (school characteristics) | SA: Lifetime history (1 item, binary) |

| Borowsky et al. (2001) | 13110 | Black (NR); Hispanic (NR) | 1995, 1996 Add Health | Grades 7–12 | US (national sample) | Safety; Connectedness; Academics; Programs; Behavior | SA: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Bush & Qeadan (2020) | 2730 (2011); 3171 (2013); 2604 (2015) | American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 2730; 3171; 2604) | 2011, 2013, 2015 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resilience Survey | High school, 9–12 | New Mexico | Connectedness | SA: Past year (1 item, frequency) |

| Cardoso et al (2018) | 534 | Latino (n = 534) | 2014 random cluster sample of NC schools | Middle and high | North Carolina | Bullying | SI: Past year (2 items, latent variable of SI and SP) |

| Cervantes et al. (2014) | 1254 | Hispanic (n = 1254) | Random classroom sampling design (nonclinical sample) | Ages 10–20 years (retrospective, clinical and non-clinical sample) | Los Angeles; Miami; El Paso; Boston | Other (cultural-educational stress) | SI: Child’s Depression Inventory

2 Self-harm: Child’s Depression Inventory 2 (NR) |

| De Luca et al. (2015) | 4983 | Latino and Latina (n = 755) | 2007–2008, random sampling of stratified classrooms or all students | Grades 9, 10, 12 | Georgia; New York | Programs | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| De Luca & Wyman (2012) | 4122 | Latino and Latina (n = 663) | 2007–2008, random sampling of stratified classrooms | Grades 9, 10, 12 | Georgia; New York | Academics | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| De Luca et al. (2012) | 1618 | Latina (n = 1618) | Add Health | High school | US (national sample) | Connectedness | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) SA: Past year (1 item, frequency) |

| Evans-Campbell et al. (2012) | 447 | Two-sprit American Indian/Alaskan Native (n = 447) | Targeted, partial network, and respondent-driven sampling | Adults (retrospective assessment of high) | 7 metropolitan areas of US | Programs | SI: Lifetime (NR) SA: Lifetime (NR) |

| Feinstein et al. (2019) and Hedegaard (2019) | 18515 | Black, bisexual (17.0%); Hispanic, bisexual (32.1%) | 2011–2015 YRBS | Grades 9–12 | 85 jurisdictions of US | Bullying | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Gloppen et al. (2018) | 1409 | American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 1409) | 2013 Minnesota Student Survey | Grades 8, 9, 11 | Minnesota | Bullying; Safety; Connectedness | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) SA: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Gulbas & Zayas (2015) | 10 | Latina (n = 10) | Community recruitment from multiple hospitals/clinics and after-school programs | Clinical sample, mean age 15.7 years | New York City | Connectedness; Academics | SA: Disclosure at a clinic used to identify participants |

| Hall et al. (2018) | 7641 | Hispanic (n = 7641) | 2013 New Mexico Youth Risk and Resilience Survey | High school | New Mexico | Connectedness; Academics | SA: Past year (1 item, frequency recoded as binary) |

| Hart et al. (2018) | 578 | African American (86.3% [based on total n of 678]) | Longitudinal universal intervention study beginning 1993 in elementary schools | Elementary (grades 1–3), middle and high school (grades 6–12) | Baltimore City | Behavior; Programs | SA: Lifetime (1 item, binary) |

| Ialongo et al. (2004) | 1197 | African American (n = 1197) | Longitudinal universal intervention study beginning 1993 in elementary schools | Grades 4–6 (time 1); young adulthood (time 2) | Baltimore City | Behavior | SA: Lifetime (1 item, binary) |

| Kim et al. (2018) | 17009–18205/ year; over 6 years | Asian American (52.3%); Latino (42.2%) | School district population data 2011–2017 | Elementary and high school | Southern California | Programs | Risk Assessment and Referral for STB over 1 year |

| LaFromboise et al. (2007) | 122 | American Indian (n = 122) | All students invited for effectiveness study, 2005–2006 school year (30.5% acceptance rate) | Middle school | Northern Plains reservation | Connectedness | SI: Current levels, The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (15 items, 7-point scale, α = .97) |

| LeVasseur et al. (2013) | 11887 | Hispanic (n = 4947); Hispanic, sexual minority (NR) | 2009 New York City YRBS | Grades 9–12 | New York City | Bullying | SA: Past year (1 item, frequency recoded as binary) |

| Li & Shi (2018)* | 1586 | Asian and Pacific Islanders (n = 317); Hispanic (n = 508); Mixed races/ethnicities (n = 475) | 2015 California YRBS | Grades 9–12 | California | Bullying | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) SP: Past year (1 item, binary) SA: Past year (1 item, frequency recoded as binary) |

| Manzo et al. (2015) | 21610 | American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 1323) | 1999–2011 YRBS | High school | Montana | Safety | STB: Past year, combined measure with SI, SP, SA, SA with injury (4 items, binary and frequency) |

| Mereish et al. (2019) | 1129 | Black (n = 1129); Black heterosexual (n = 839); Black mostly heterosexual (n = 224); Black bisexual, mostly gay or lesbian, or gay, lesbian or homosexual (n = 66) | 2014 Youth Development Survey | Middle and high school | 1 large county in North Carolina | Bullying | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) SP: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Mueller et al. (2015) | 75344 | Black (19.8%); Black, heterosexual (NR); Black, gay or lesbian (NR); Black, bisexual (NR); Hispanic (30.8%); Hispanic, heterosexual (NR); Hispanic, gay or lesbian (NR); Hispanic, bisexual (NR) | 2009 and 2011 YRBS | High school | School district data: Boston; Chicago;

Washington, DC; Houston; Los Angeles; Milwaukee; New York City; San

Diego; San Francisco; Seattle. Statewide data: Connecticut; Delaware; Hawaii; Illinois; Maine; Massachusetts; North Dakota; Rhode Island; Wisconsin |

Bullying | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Novins et al. (1999) | 1353 | American Indian (n = 1353) | 1993 Voices of Indians Teens Project | Grades 9–12 | 4 rural communities west of Mississippi | Academics | SI: Past month, Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (6 items, binary if at least two items endorsed twice a week) |

| Piña-Watson et al. (2014) | 345 | Latina (n = 345) | Add Health | Ages 13–18 years | US (national sample) | Academics | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Poteat et al. (2011) | 15923 | Racial/ethnic minority, heterosexual (NR); Racial/ethnic minority, LGBTQ (NR) | 2009 Dane County Youth Assessment | Grades 7–12 | Dane County, Wisconsin | Bullying; Connectedness; Academics | Factor score of SI and SA combined

(loadings .62–.82) SI: Past 30 days (1 item, multiple choice of frequency) SA: Past year, multiple choice frequency) |

| Qiao & Bell (2017) | 173274 | Indigenous adolescents (American Indian/Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian/ other Pacific Islander) attending high schools off reservations (n = 2996) | 12 biennial surveys 1991–2013 YRBS | Grades 9–12 | US (national sample) | Safety | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) SP: Past year (1 item, binary) SA: Past year (1 item, frequency) |

| Turanovik & Pratt (2017) | 558 | Native American (n = 558) | 1994–1995 Add Health | Grades 7–12 | US (national sample) | Connectedness | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) |

| Wang et al. (2019) | 301628 | Latino (13.1%); Black (34.8%); Asian (4.2%) | 2013–2014 Georgia Student Health Survey 2.0 | Grades 6–8 | Georgia | Academics | STB: Past year (4 items, frequency of behaviors, α = .86) |

| Wang et al. (2018) | 12511 | Asian American (n = 12511) | 2013–2014 Georgia Student Health Survey 2.0 | Grades 6–8 | Georgia | Bullying; Connectedness; Academics; Other: school demographics | STB: Past year (4 items, frequency of behaviors, α = .84) |

| Whaley & Noel (2013) | 3008 | African American (n = 2600); Asian American (n = 408) | 2001 YRBS | High school | US (national sample) | Academics | SI and Depression: Past year (3 items, binary response options summed, α = .73) |

| Wintterowd et al. (2010) | 338 | Mexican American (n = 338) | Community recruitment | Community sample, ages 14–19 | Southwestern US | Connectedness; Academics | SI: Past year (1 item, 4-point scale

recoded as binary) SA: Past year (1 item, 4-point scale recoded as binary) |

| Wong & Maffini (2011) | 959 | Asian American (n = 959) | Add Health | Middle and high | National | Connectedness | SI: Past year (1 item, binary) SA: Past year (1 item, binary) |

Notes.

Total analytic sample size may include students representative of multiple R/E backgrounds;

R/E background listed as described in each study, with sample size per R/E minoritized group displayed in parentheses when available;

STB Measures reflect time (number of items, response options, and, if available, estimates of internal reliability).

Add Health = National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning/queer; R/E = racial/ethnic; SA = suicide attempt; SI = suicidal ideation; SP = suicide plan; N/A = not applicable; NR = not reported; STB = suicide-related thoughts and behaviors; YRBS = Youth Risk Behavioral Survey.

Results

Our literature review (conducted on August 8, 2019) yielded a total of 1,218 peer reviewed articles (see Supplementary Figure S1 for PRISMA style flow chart). Following screening of titles and abstracts, the full text of 145 articles was reviewed. At this stage, 72 articles were excluded due to not meeting eligibility criteria, yielding 73 articles that examined sexual minoritized (k = 46), American Indian (k = 9), Black (k = 9), Hispanic (k = 17), and Asian American (k = 6) students. One study (k = 1) examined R/E minoritized students in aggregate, and one (k = 1) included separate results for students identifying as mixed R/E; no studies examined Arab American students. For the current review, studies that focused on sexual minoritized students who were not R/E minoritized students were excluded (k = 40), resulting in the inclusion of a total of 33 articles.

Sample characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1. Findings from studies are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1) and described in the subsequent section. For ease of interpretation, findings are presented according to R/E group and categorized according to the broad domains described previously and presented in the following order: (1) bullying and safety; (2) school connectedness; (3) academics; (4) program effects; and (5) in-school behavior and other school-related variables.

American Indian and Alaskan Native Students

Studies exploring STB in American Indian students (k=9) examined bullying (k=1), safety (k=3), school connectedness (k=5), academics (k=2), programs (k=2), behavior (k=1), and other (school characteristics, k=1).

Bullying and Safety

Both bullying perpetration and victimization were significantly associated with increased reports of past year suicidal ideation (OR ranging from 1.81 to 2.15) and lifetime suicide attempts (OR ranging from 2.23 to 2.87) in a sample of 1,409 American Indian students (Gloppen et al., 2018). Results varied according to the type of bullying; for example, R/E bullying victimization was associated with increased reporting of past year suicidal ideation but not suicide attempts (Gloppen et al., 2018). Feelings of safety at school played a protective role for suicide attempts (OR ranging from 0.53 to 0.58), but not for ideation (Gloppen et al., 2018). Lack of school safety (i.e., being threatened in school) was also found to significantly relate to an increase in both suicidal ideation (OR = 2.38) and suicide plans (OR = 2.56), but not in suicide attempts (Qiao & Bell, 2017). In contrast, Manzo and colleagues (2015) found that being threatened at school was not significantly related to an aggregate measure of STB in American Indian students. Across studies, findings suggest bullying experiences are negatively linked to STB in American Indian students, with relatively large effect sizes, and indicate preliminary support for feeling safe at school to protect against suicide.

School Connectedness

Findings pertaining to the protective role of school connectedness and positive school relationships against STB were mixed in American Indian students. Student-teacher relationships were not significantly related to past year suicidal ideation or lifetime history of suicide attempts (Gloppen et al., 2018). Bivariate relationships between school attachment or school belonging were significantly related to suicidal ideation, yielding small to moderate effect sizes, but when accounting for other significant predictors of suicide (e.g., depression, substance use, child victimization), findings were no longer significant (LaFromboise et al., 2007; Turanovik & Pratt, 2017). Moreover, school attachment was not supported as a significant moderator of the relationship between violence victimization and suicidal ideation (Turanovik & Pratt, 2017). In a different sample of secondary school students, liking school served a protective function against lifetime histories of suicide attempts (approximately half as many students who liked school reported a suicide attempt compared to those who did not like school; Borowsky et al., 1999). Finally, one study used an aggregate measure of social support from parents, schools, and peers and found that students reporting low (adjusted OR [aOR] range = 2.2 to 5.5) and moderate (aOR range = 1.5 to 1.9) levels of support were significantly more likely to have a past year suicide attempt compared to students with high support (Bush & Qeadan, 2020). Note that in the latter study, while some of the effect sizes were moderate to large, the confidence intervals were relatively wide (e.g., 3.1 to 9.6 for the largest effect) indicating a low level of precision. In summary, findings that have supported a relationship between school connectedness and STB in American Indian students have yielded small to moderate effect sizes, with the greatest effects for those with the lowest levels of school connectedness.

Academics

Studies exploring academics in relation to STB among American Indian students point to the importance of differentiating between individual academic performance and school-level indicators of academic success. Specifically, although individual grade performance was not associated with past month suicidal ideation or plans (Novins et al., 1999), schools with high levels of academic achievement (in the top quarter) were found to have significantly lower numbers of students with lifetime histories of suicide attempts (9.6% compared to 14.6% of boys; and 18.3% compared to 27.0% of girls; Borowsky et al., 1999).

Program Effects

Borowsky et al. (1999) examined additional school factors in relation to STB, including whether schools had in-house clinics or nurses and whether students had histories of attending special education classes. The proportion of girls, but not boys, reporting lifetime history of suicide attempts was significantly higher among those in schools without a school clinic or nurse (24.2%) compared to those with one (20.9%). Reporting a lifetime history of being in a special education class was also positively associated with attempt for boys (13.8% compared to 11.3% without a history of special education) but only approached significance for girls. In a final multivariate analysis, controlling for the effects of age, special education status (OR = 1.38) and having a school-based clinic or nurse (OR = 0.83) remained significant predictors of suicide attempts for girls (but were not included in the model for boys). Regarding sexual minoritized American Indian students, Evans-Campbell and colleagues (2012) explored the relation between attending boarding school and STB in two-spirit (i.e., gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender) students. Attending a boarding school was associated with lifetime suicidal ideation and making a suicide attempt, and having a caregiver who attended boarding school was significantly related to lifetime ideation (but not attempts). Proportions of suicidal ideation were between 4–9 percentage points higher in individuals with a history of attending a boarding school or having a caregiver attend one. The proportion of suicide attempts was 22 percentage points higher for those attending a boarding school than those not attending one (Evans-Campbell et al., 2012).

In-School Behavior and Other School-Related Domains

Findings from Borowsky et al.’s (1999) study also suggested that the proportions of suicide attempts for boys and girls skipping school in the last month (boys 18.6%, 31.5% girls) were significantly higher than for those not skipping school (boys 9.4%, girls 18.7%); they were also higher for boys and girls who had health problems limiting time in school (boys 19.2%, girls 26.8%) than those who did not (boys 11.0%, girls 21.2%). The proportion of girls, but not boys, reporting lifetime history of suicide attempt was significantly higher among those in schools with mostly students of other races (26.0%) than those in other schools (21.4%); however, for both boys and girls, suicide reports were higher in schools with higher delinquent activity (boys 14.9%, girls 26.2%) than lower delinquent activity (boys 11.0%, girls 20.0%).

Hispanic and Latinx Students

Among Hispanic students, studies (k=17) addressed bullying (k=5), safety (k=1), school connectedness (k=6), academics (k=7), programs (k=3), behavior (k=1), and other areas (cultural-education stress, k=1).

Bullying and Safety

Li and Shi (2018) found an indirect relationship between bullying and STB through depression for all R/E groups. Although the direct effects of bullying remained significant after accounting for depression for all other R/E groups, they were no longer significant for Hispanic youth, with depression accounting for the greatest proportion of total effects for Hispanic (51.9% of the total effect was mediated by depression) and Asian American groups. Bullying was indirectly related to suicide through alcohol use for Hispanic youth; however, only 7.8% of the total effect was mediated by alcohol (Li & Shi, 2018). Regarding different types of bullying, depression was also found to mediate the relationship between ethnic-biased and verbal/relational bullying (but not general or physical bullying) and suicidal ideation (Cardoso et al., 2018). LeVasseur and colleagues (2013) reported that, among non-Hispanic sexual minoritized students and Hispanic non-sexual minoritized students, victimization was related to STB (OR = 2.76 for girls; 3.30 for boys); however, this relationship was not significant for Hispanic sexual minoritized students (LeVasseur et al., 2013).

Comparisons of rates of STB between Hispanic students and others, after controlling for bullying, revealed mixed findings. Research examining data from the 2009 and 2011 YRBS found that Hispanic heterosexual female students had increased odds for reporting past year suicidal ideation compared to White heterosexual females even after accounting for bullying (OR = 1.33), but Hispanic males did not (Mueller et al., 2015). Among sexual minoritized students, however, Hispanic lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth had increased odds for ideation compared to White heterosexual students, even after accounting for bullying (OR ranging from 2.21 to 4.42; Mueller et al., 2015). In a different analysis of the 2017 YRBS data, however, Feinstein and colleagues (2019) reported that there were no significant differences in reports of past year suicidal ideation in bisexual Hispanic students compared to bisexual White students, even after controlling for bullying; nevertheless, as compared to Black bisexual students, Hispanic bisexual students were nearly two times as likely to report past year suicidal ideation after controlling for bullying (OR = 1.74).

Finally, only one study explored school safety in relation to STB in Hispanic youth. In a national sample of over 130,000 students, Borowsky et al. (2001) reported positive and large effects of individual perceptions of school safety in relation to past year suicide attempts in Hispanic boys (OR = 0.25) but not girls.

School Connectedness

Across the six studies exploring school connectedness in Hispanic populations, findings largely support a protective role against STB with moderate to large effect sizes. School connectedness was associated with reduced odds for past year suicide attempts in a national sample of Hispanic boys (OR = 0.12) and girls (OR = 0.23; Borowsky et al., 2001), and positive relationships with school adults appeared to protect against past year suicide attempts in a sample of high schoolers in New Mexico (OR range = 0.67 to 0.69; Hall et al., 2018). De Luca et al. (2012) found that teacher caring appeared to protect against suicide attempts in Hispanic female students, with relatively robust effects (for every point increase on teacher caring, there was a 23% decrease in likelihood for reporting a suicide attempt), even after accounting for other protective factors (e.g., depression, parent caring). Results were not significant for suicidal ideation. In a sample of Mexican American adolescents, school friendship connections were significantly related to past year suicidal ideation among girls (OR = 1.14) but not boys (Wintterrowd et al., 2010). After accounting for educational status, however, results indicated that school friendships were protective against suicidal ideation only for girls in good academic standing (these relationships were not significant for attempts; Winterrowd et al., 2010). A qualitative study examining perceived reasons for having made a suicide attempt in 10 adolescent-parent Hispanic dyads and triads found that adolescents without a sense of emotional isolation described having a sense of belonging to school, including positive peer and adult school relationships (Gulbas & Zayas, 2015). In contrast, a study of both Hispanic and Black students found that social support, which included family, friends, and school support, was not significantly related to past year suicide attempts for Hispanic students (Bennett & Joe, 2015).

Academics

For Hispanic students, preliminary research has supported moderate effects for parental academic interest to protect against STB; however, findings yielded mixed results related to academic performance and school engagement. Parental academic interest was found to be protective against ideation in Hispanic females (OR range = 0.68 to 0.71), even after accounting for other predictors (Piña-Watson et al., 2014). In another study, although perceived parental involvement in education was found to protect against past year STB for students across R/E groups, its effects were less beneficial for Hispanic than White students (Wang et al., 2019).

Regarding academic performance, educational status (i.e., being in good academic standing versus academically at-risk) was not significantly related to past year ideation or attempts among Mexican American adolescents (Wintterowd et al., 2010). In a longitudinal study, Hispanic females, but not males, were more likely to report a past year suicide attempt after repeating a grade in high school (OR = 1.9). Conversely, grade point average was strongly related to lower reports of suicide attempts for Hispanic boys (OR = 0.15), but not girls (Borowsky et al., 2001). Problems with academics, however, were a strong predictor of suicide attempts for all students (male and female, Black, Hispanic, White, and Hispanic), with large effects for Hispanic boys (OR = 6.9) and girls (OR = 3.1; Borowsky et al., 2001). Gulbas and Zayas (2015) also reported that, of the 10 Hispanic girls in their qualitative study, some identified academic difficulties as having contributed to their suicide attempts.

Remaining studies focused on school engagement. For students attending all types of schools (both predominantly Hispanic and not), school engagement did not predict past year help-seeking or suicidal ideation disclosure in Hispanic youth (De Luca & Wyman, 2012). For Hispanic males only, school engagement did significantly predict disclosure of ideation to an adult (OR = 7.65) and help-seeking behaviors (OR = 6.17) in predominantly Hispanic schools; however, confidence intervals indicated a wide degree of variability with low precision (De Luca & Wyman, 2012). Finally, having post-high school education plans was negatively related to past year suicide attempts (boys, OR = 0.62; girls, OR = 0.61; Hall et al., 2018).

Programs Effects

Two studies explored school programs and policies in relation to STB. School policies on fighting did not demonstrate a significant effect for suicide attempts for any R/E group, including Hispanic students (Borowsky et al., 2001). In one southeastern California school district comprising predominantly Hispanic and Asian American students, Kim and colleagues (2018) found that Hispanic students were most represented in risk assessments across all school levels (K-12) and less likely to decline services compared to Asian American students (relative risk ratio [RRR] = 0.26). Moreover, De Luca et al. (2015) found that being Hispanic and having a history of past year suicidal ideation was associated with lower perceptions of acceptability for both males and females; however, the interaction of ethnicity and ideation was only significant for males. Hispanic males reporting past year suicidal ideation endorsed more favorable attitudes toward help-seeking and adult support for suicidal concerns, as compared with non-Hispanic White males, yielding small effects (β = .08, .10, respectively; De Luca et al., 2015).

In-School Behavior and Other School-Related Domains

Skipping school was related to increased rates of past year suicide attempts for Hispanic girls (OR = 3.1) , but not Hispanic boys (Borowsky et al., 2001). After accounting for other types of stress (e.g., family drug stress, discrimination stress), cultural educational stress did not significantly relate to suicidal ideation or self-harm for Hispanic youth (Cervantes et al 2014).

Black and African American Students

Nine studies examined STB and school-related variables in Black students, including bullying (k=3), safety (k=1), connectedness (k=2), academics (k=3), programs (k=2), and behaviors (k=3).

Bullying and Safety

Bullying was explored primarily in relation to differences in rates of STB in Black students compared to other R/E groups, and findings consistently indicated moderate to large effect sizes (although not always in the same direction). Mueller and colleagues (2015) reported that Black heterosexual female students (but not Black heterosexual males) had increased odds for reporting past year suicidal ideation as compared to White heterosexual females, only after accounting for bullying (OR = 1.27; Mueller et al., 2015). In sexual minoritized students, however, Black LGB students had increased odds for reporting ideation compared to White heterosexual students with or without accounting for bullying (OR range = 1.98 to 4.59 after accounting for bullying; Mueller et al., 2015). In contrast, however, Feinstein et al. (2019) reported that, as compared to White bisexual students, Black bisexual students were significantly less likely to report past year suicidal ideation, even after controlling for bullying (OR = 0.59).

An additional study exploring bullying in Black youth focused on sexual orientation disparities in mental health and substance use outcomes (Mereish et al., 2019). Black students identifying as LGB or mostly heterosexual reported higher rates of suicidal ideation and planning as well as more cyber- and bias-based victimization compared to their Black heterosexual peers. Among Black LGB and heterosexual students, victimization only partially mediated the link between sexual minoritized status and suicide planning (aOR = 1.30) but not suicidal ideation. Among Black “mostly heterosexual” and Black heterosexual students, victimization partially mediated the link between status and both suicide planning (aOR = 1.40) and ideation (aOR = 1.24; Mereish et al., 2019). Finally, one study explored perceptions of school safety in relation to STB in Black students, and results were not significant (Borowsky et al., 2001).

School Connectedness

Results from one study suggested that school connectedness was not significantly related to past year suicide attempts in Black boys and girls (Borowsky et al., 2001). In contrast, a study of Hispanic and Black students found that social support from family, friends, and school was significant in predicting past year suicide attempts for Black students (Bennett & Joe, 2015).

Program Effects

African American boys receiving special education services in elementary school were significantly less likely to report a lifetime history of suicide attempt, yielding a moderate effect size (β = −0.51; Hart et al., 2018). Results from another study did not find a significant relationship between receipt of counseling services and STB (Borowsky et al., 2001).

Academics

School problems (e.g., difficulties with paying attention or completing homework), but not repeating a grade, were related to past year suicide attempts one year later for all R/E groups, including Black students (girls, OR = 5.3; boys, OR = 7.2; Borowsky et al., 2001). In the same study, grade point average was also strongly related to lower reports of suicide attempts for Black boys (OR = 0.10), but not Black girls (Borowsky et al., 2001). Additionally, high academic achievement played a protective role against suicide risk (Whaley & Noel, 2013). In a study exploring middle schoolers’ perceptions of parent involvement in education, involvement appeared to protect against past year STB for all students, although it was a somewhat less powerful buffer for R/E minoritized students than for White students (Wang et al., 2019).

In-School Behavior

The in-school behaviors of Black students in relation to STB were explored in three studies. Findings reported by Borowsky and colleagues (2001) did not support a significant relationship between skipping school and past year suicide attempts. The remaining studies focused on teacher observations of behavior. Hart and colleagues (2018) conducted latent class growth models in a predominantly Black middle and high school sample and found support for two classes based on teacher observations of aggressive behavior from 6th grade to end of high school; however, race did not significantly predict class membership, and class membership did not significantly predict suicide (Hart et al., 2018). In contrast, Ialongo et al. (2004) explored teacher reports of aggression in a sample of nearly 2,000 Black children and found that, after accounting for reports of childhood depression and suicidal ideation, reports of aggressive behavior in grades 4 (OR = 1.40) and 5 (OR = 1.36) demonstrated a significant positive relationship with lifetime history of suicide attempts (measured in young adulthood). Among grade 6 students, however, only depressed mood (but not aggression) predicted attempt. In fact, findings from Receiver Operating Curve Analyses indicated that aggressive behavior only minimally increased specificity after accounting for depressed mood in grades 4, 5, and 6 (areas under the curve increased by 0.03, 0.02, and 0.00, respectively; Ialongo et al., 2004).

Asian American and Pacific Islander Students

Six studies focused on Asian American students, including bullying; connectedness (k=2); academics (k=3); programs (k=1); and other (school demographics, k=1).

Bullying

Results from two studies indicated that student reports of bullying or victimization were significantly related to STB with small (β range = 0.02 to 0.09; Wang et al., 2018) and large (OR = 4.66; Li & Shi, 2018) effects. Results from the former study suggested that perceptions of positive school climate (perceived cultural acceptance, safety and connectedness) buffered effects of face-to-face victimization (when climate was measured at the individual level) and cyber victimization (when climate was measured at the school-level) on STB, but perceptions of parent involvement did not interact with the relationship between STB and either type of victimization (Wang et al., 2018). Results from the latter study (Li & Shi, 2018) supported significant indirect effects related to STB through depression, with depression accounting for the greatest proportion of total effects for Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander groups (proportion of total effect mediated by depression was 55.3% for Asian American youth).

School Connectedness

In a measure of school climate that included perceptions of school connectedness, peer and adult social support, cultural acceptance, character, physical environment, safety, and order/discipline, individual perceptions were significantly protective against past year STB (yielding a small effect size); findings were not significant when measured at the school level (Wang et al., 2018). In a study exploring a national sample of Asian American students using Add Health data, Wong and Maffini (2011) used latent class analysis to identify subgroups of students based on levels of family, school, and peer belongingness and rates of suicide attempts. While bivariate relationships supported a small, protective effect of school relationships against past year suicidal ideation (r = −.16) and attempts (r = −.11), they were not significant for suicide attempts measured over the following year. Results of the latent class analysis, however, suggested that school relationships as a protective factor against suicide may vary according to perceptions of family and peer relationships, gender, and acculturation. High levels of acculturation and being a girl were associated with membership in a non-protective relationship class (in which students’ parent and peer relationships did not significantly predict suicide attempts, but stronger school relationships predicted higher rates of suicide attempts). Low levels of acculturation were associated with the mixed relationships class (in which stronger school and family relationships were significantly related to lower rates of suicide attempts, but stronger peer relationships were significantly related to higher rates of suicide attempts). Although the majority of students (57%) fell in a protective relationship class, in which stronger relationships with parents, school, and peers were related to reduced likelihood of having made a suicide attempt, approximately one-third of students (32%) were classified in the non-protective class described above. The researchers postulated that because these students were also more likely to be girls and have higher levels of acculturative stress, connectedness to school may have actually exacerbated parental disapproval and STB in Asian American girls (Wong & Maffini, 2011).

Academics

Asian American perceptions of parent involvement in education demonstrated a protective effect against past year STB (yielding a small effect size; Wang et al., 2018). Within the larger sample inclusive of all R/E minoritized and majority students, student perceptions of parent involvement demonstrated a protective effect against past year STB, but effects were less beneficial for Asian American students than White students (Wang et al., 2019). Finally, Whaley and Noel (2013) found that high academic achievement appeared protective against suicide risk.

Program Effects

As reported previously, Kim and colleagues (2018) explored the likelihood of R/E minoritized students receiving services in a district of predominantly Hispanic and Asian American students. Asian American students were underrepresented in risk assessments relative to percent enrollment across all school levels (K-12). Among boys, however, Asian American students were most represented in risk assessments conducted in elementary and middle schools. Furthermore, Asian American students were significantly less likely to accept mental health services and less likely to have an initial treatment session following risk assessment compared to Hispanic, but not other, students (RRR = 0.26 and 0.55, respectively; Kim et al., 2019).

Other School-Related Domains

Only one study explored school level demographics (e.g., student-teacher ratio, percent minority) as predictors of STB and did not find a significant relationship in Asian American students (Wang et al., 2018).

Mixed Racial/Ethnic Minoritized Students and Students Reported in Aggregate

One study explored the relationship between bullying and STB in R/E minoritized students, and one study explored multiple domains of school experiences (bullying, connectedness, and academics) in relation to STB in a general sample of R/E minoritized students reported in aggregate.

Bullying

Li and Shi (2018) found a direct relationship between bullying and STB in mixed R/E students (OR = 4.70) that remained significant even after accounting for alcohol and drug use. Significant indirect effects of bullying on STB through depression were also supported, with depression accounting for 32.3% of the total effects in mixed R/E groups (Li & Shi, 2018). In a general sample of R/E minoritized students (not disaggregated by ethnicity or race), Poteat and colleagues (2011) explored the indirect effects of bullying victimization on academic outcomes (grades, truancy, and perceived importance of graduating) through STB. Results supported this model in both R/E minoritized heterosexual students and R/E sexual minoritized students, as well as White heterosexual students, but not in White sexual minoritized students. Homonegative victimization (i.e., being bullied, threatened, or harassed for being perceived as gay, lesbian, or bisexual) was also found to indirectly relate to academic outcomes (grades and importance of graduating only) through STB for R/E minoritized heterosexual students, but not for R/E minoritized LGBTQ students. Note, however, that the researchers did report significant correlations between both types of bullying (general and homonegative) and STB in both heterosexual and LGBTQ R/E minoritized youth, with small to moderate effect sizes (r range = .13 to .33).

Connectedness

Poteat and colleagues (2011) also reported significant correlations between school belonging and STB in heterosexual (r = −.14) and LGBTQ (r = −.26) R/E minoritized students.

Academics

Finally, significant correlations between academics (i.e., grades, truancy, and the importance of graduating) and STB were supported in both heterosexual (r range = −.08 to −.18) and LBGTQ (r range = .24 to −.31) R/E minoritized students (Poteat et al., 2011).

Discussion

This systemic literature review identified research exploring school-related factors that may influence STB in R/E minoritized students to expand previous cultural models of suicide and inform a culturally relevant approach to suicide prevention in schools. A number of cross-cutting findings emerged, signifying the importance of building a school-family-community partnership. As expected, findings also indicate the need for unique considerations regarding protective and risk factors across individual R/E minoritized groups. We elaborate on cross-cutting and unique findings across R/E groups and expand on findings to inform a cultural model of suicide prevention specific to school settings. Findings outline the complexities involved in addressing STB in R/E minoritized youth, indicating the need for a more comprehensive preventive approach to addressing suicide in schools.

Cross-Cutting Risk and Protective Factors

Cross-cutting risk and protective factors of STB signify the importance of attending to: individual perceptions of school environments (promoting a sense of school connectedness and strengthening school relationships, improving school safety, and disrupting patterns of school bullying); school-level factors that include demographic characteristics of the student body and school-level indicators of climate; and individual behaviors such as academic performance and parent involvement in education. In contrast, there appears to be minimal evidence to suggest that some of the intraindividual behaviors explored in these studies, such as problem behaviors in school, are among the most salient risk factors for STB in R/E minoritized youth.

Individual-Level Perceptions of School Environment

The literature was relatively consistent in revealing the potential for bullying to exacerbate STB and perceptions of school safety to protect against STB in most R/E minoritized groups. Findings indicate that depression may serve as an important mediator between bullying experiences and STB in Hispanic students. Rates of STB in Black students appear to be higher than in White students after accounting for bullying experiences (with moderate effects). There is also preliminary support for bullying as a risk factor for STB in American Indian and Asian American students; however, additional studies are needed to substantiate these findings.

Feelings of school connectedness were also consistently shown to have protective effects against STB in both American Indian and Hispanic students, demonstrating small and moderate effects respectively. Although preliminary support for the buffering effects of positive school climate against STB was also found in Asian American students, findings are less clear regarding the protective effects of school connectedness in Black students. Additional research exploring if and how school connectedness can protect against STB in R/E minoritized students is warranted. Still, because school connectedness provides numerous social-emotional and academic benefits, it should be considered an integral part of universal school-based suicide prevention programs.

School-Level Risk and Protective Factors

Although only explored in a small number of studies, school-level characteristics also appear to be an important consideration for suicide prevention across R/E minoritized groups. For American Indian students, school factors related to limited representativeness of American Indian students, academics, and delinquent behavior were significantly associated with increased STB. However, findings related to intraindividual risk factors, including academics and skipping school, were mixed, with only the latter showing significance (Borowsky et al., 1999). Similarly, the demographic characteristics of schools appeared to influence help-seeking behaviors; for example, attending schools with predominantly Hispanic student bodies appeared to promote more help-seeking behaviors in Hispanic males who also endorsed higher levels of school engagement (De Luca & Wyman, 2012). Although one study did not support a significant relationship between student body demographics and STB in Asian American students (Wang et al., 2018), overall findings across studies suggest the importance of considering the makeup of the school community when implementing prevention programs.

These findings also underscore the need for further research investigating both individual- and school-level predictors of STB. For example, findings from one study indicated that the negative effects of face-to-face bullying on STB were weaker in Asian American students reporting higher levels of positive school climate; moreover, the negative effects of cyberbullying on STB were weaker for students in schools with higher levels of school climate (Wang et al., 2018). While individual perceptions of the school environment are clearly linked to STB, there is also the potential for aggregate perceptions of school environment to mitigate the risks from other environmental stressors. Given the limited number of studies exploring school-level factors in relation to STB, however, the generalizability of these findings remains unclear.

Individual-Level Behaviors

Studies exploring student behavior as a predictor of STB across R/E minoritized groups have revealed mixed findings according to specific school-related constructs. In-school aggression and school-related problems only minimally predicted STB in Black students (Hart et al., 2018; Ialongo et al., 2004), and skipping school was inconsistently related to STB in American Indian, Hispanic, and Black students (Borowsky et al., 2001). Findings were mixed regarding school engagement as a protective factor against STB in Hispanic students; however, school engagement was not examined in other R/E minoritized groups. While aggressive behaviors in elementary school-aged (but not middle or high school-aged) Black children were significant predictors of STB over time, effects of aggressive behavior above those of depressive symptoms were very small (Ialongo et al., 2004). Moreover, aggressive behavior may actually reflect how students learn to cope with existing racial trauma. Future inquiries should consider how underlying trauma associated with systemic racism may exacerbate suicidal tendencies, and conversely, how antiracist and racially positive school climates could protect against them.

Studies exploring parent behaviors as predictors of STB consistently revealed protective effects of parent engagement in school for Asian American youth, with preliminary evidence supporting this relationship in Hispanic and Black students. The potential for academic achievement to be protective against suicide was also supported across most R/E minoritized groups, with some exceptions (e.g., Novins et al., 1999; Winterrowd et al., 2010); such exceptions indicate the potential for related academic stressors to serve as risk factors (Gulbas & Zayas, 2015). Thus, partnering with parents to promote academic success within a healthy school environment that emphasizes both academic and social-emotional well-being is of priority.

Cultural Variability

While crosscutting findings offer a useful heuristic for understanding school-related risk and protective factors across R/E minoritized groups, there are also a number of critical considerations for school-based suicide prevention that vary according to each R/E minoritized group. While by no means exhaustive, findings shed light on specific considerations that may vary across cultures. Specifically, these include the need to consider intersectionality; addressing barriers in services due to stereotyping; and accounting for and recognizing the sociopolitical context of individual cultures in relation to suicide risk assessment and intervention.

Consideration of Intersectionality

Suicide prevention for sexual minoritized students of color requires careful consideration. Findings suggest that bullying victimization may exacerbate suicidal tendences among Hispanic heterosexual youth but not necessarily their sexual minoritized peers (LeVasseur et al., 2013). Yet other studies suggest that victimization may be an important consideration for suicide prevention in Black sexual minoritized students (Mereish et al., 2019) and sexual minoritized students of color more generally (Poteat et al., 2011); note, however, another study suggested it may be less salient for Black bisexual youth (Feinstein et al., 2019). Discrepancies in findings may be attributable to the heterogeneity of sexual minoritized groups (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer) or to cross-cultural differences in acceptance of sexual minoritized identities (e.g., Glick & Golden, 2010; Richter et al., 2017), reinforcing the importance of approaches to suicide prevention that are flexible and adaptive to the unique needs within and across cultures.

Stereotypes as a Barrier to Services

Given the potential for hidden suicidal ideation and the influence of model minority myth (Shih et al., 2019), findings suggest the need to proactively identify Asian American students at risk for suicide. These findings align with previous, more general mental health research (i.e., not focused on suicide) suggesting that Asian Americans are less likely to receive referrals for mental health in schools (Guo et al., 2014) and other settings (Nestor et al. 2016). Future work is warranted not only for uncovering improved and more culturally appropriate identification methods for all students, but also for identifying mechanisms for supporting treatment engagement and reducing disparities in care linkage, especially for R/E minoritized students.

Sociopolitical Context

Consideration of different ways in which R/E minoritized groups have been oppressed in schools and elsewhere – both historically and presently – is particularly important for structuring culturally-informed suicide prevention in schools. The forced removal of tens of thousands of American Indian children from their homes into boarding schools has had lasting deleterious effects on mental health across multiple generations of youth (Burnette et al., 2016). Results from one of the included studies reinforce the importance of considering these effects for school-based suicide prevention (Evans-Campbell et al., 2012), perhaps explaining some of the mixed findings regarding school connectedness as protective against STB. Likewise, the persistent bias and stereotyping of Black students that occurs in schools could explain the incongruent findings related to school safety, school connectedness, and counseling services. These were relatively consistent predictors of STB for other minoritized groups but not for Black students. Previous work suggests Black students feel less connected to their schools than their White peers (Bonny et al., 2000) and that feelings of connectedness may diminish with age (Cook et al., 2012). Thus, school connectedness could be protective against suicide in Black students, but investigations of this relationship require a deeper understanding of the ways in which institutional racism compromises opportunities for school connectedness and disenfranchises Black youth.

Implications of Cross-Cutting and Variable Findings

Findings underscore the need for research that addresses the variability in cultural meanings of school connectedness, parent involvement, and acculturative stress for all R/E minoritized groups. Although previous research has focused on cultural meanings of suicide risk and protective factors in R/E individuals, virtually no studies have explored them in the context of school-specific variables. Yet, even with deeper insights into how cultural meaning varies by R/E group, we cannot expect to take a standard approach to suicide prevention for all students within a given group. Inevitably, within group variability in individual and family experiences will interact with other cultural influencers of STB, necessitating an approach to risk assessment, interventions, and community referrals that is sensitive to individual and cultural differences.

Schools should adopt systems-level interventions incorporating prevention practices that are sensitive to previously identified risk factors and warning signs of suicide risk, with appreciation for the variability across R/E students. That is, a preventive, collaborative approach to increasing feelings of belonging, safety, and support for R/E minoritized students may look different based on both school and student characteristics. Invariably, however, it entails a more comprehensive, collaborative, strength-based, and solution-oriented framework. It situates problems outside of students and approaches student suicide risk within a systemic framework. Similar to integrated models of youth suicide risk among minoritized youth (Opara et al., 2020), this framework considers the intersection of individual and systems-level risk factors that are unique to R/E groups, thereby allowing for targeted prevention and intervention at various levels. While there are a number of promising school-based universal prevention programs (e.g., signs of suicide; the good behavior game), we are not aware of any evidence-based interventions that have been culturally tailored to specific R/E minoritized groups. Moreover, implementation of any program requires consideration of the unique needs of each school and school district at large. Thus, schools should consider integrating the cultural values, norms, and practices that reflect their student body into existing school-based mental health supports and comprehensive suicide prevention programs. By implementing culturally sensitive interventions that value and celebrate cultural diversity, schools can deliver culturally responsive, evidence-based treatments tailored to specific individual needs (Jackson & Hodge, 2010).

Expanding Multicultural Models for Preventing Suicide into Schools

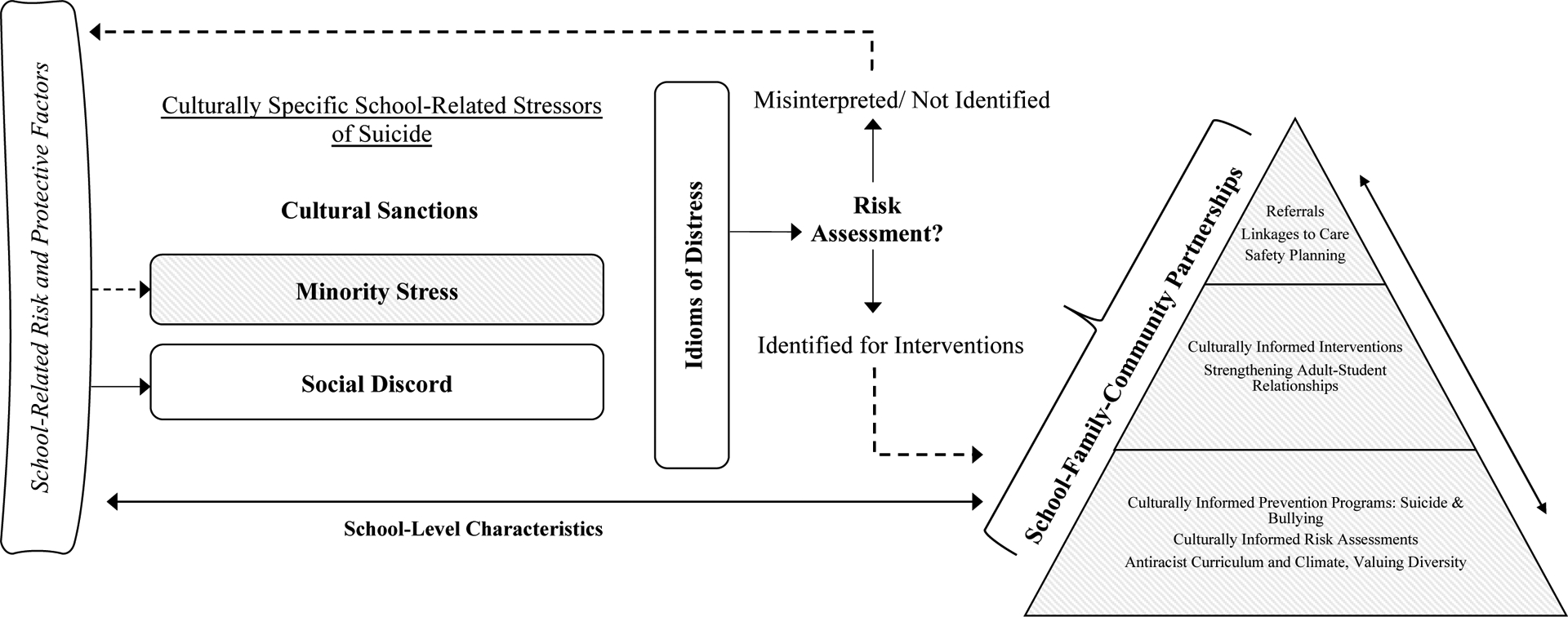

Findings, both cross-cutting and variable, shed light on the ways in which school-related risk and protective factors may be considered alongside the culturally specific risk categories (cultural sanctions, minority stress, and social discord) and cultural variations in psychological symptoms (i.e., idioms of distress) identified by Chu and colleagues (2010), with direct implications for practice. As shown in Figure 1, we propose that idioms of distress and a school’s ability to correctly identify and intervene in suicide risk are a determinant in whether or not schools can provide interventions or referrals to prevent suicide. Potential school-based supports, interventions, and services are shown within a multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) framework, with an arrow connecting school-based risk factors and MTSS that signifies the potential for dynamic patterns of risk; additionally, ongoing assessment, monitoring, and intervention are all housed within the broader influences of school level characteristics.

Figure 1.

Culturally Specific Risk Factors in Schools

Notes. Figure adapted from Chu (2010); Boxes in white indicate preliminary research supporting school context, boxes with dashed lines indicate areas requiring investigation.

If a student remains unidentified by schools for suicide risk, school-related risk factors may intersect with the domains of cultural sanctions, minority stress, and social discord, all of which are influenced by cultural and individual variability, as well as other known risk factors, thereby perpetuating a cycle of negative school experiences and STB. School-based risk and protective factors that align with minority stress and social discord have implications for both universal and targeted interventions, which in turn inform a multiculturally focused theory of suicide risk adapted for school environments. Drawing from a strength-based perspective, however, we also propose that risk may be mitigated in part by both naturally occurring and intentionally selected school protective factors, including universal school practices and positive, anti-racist school climates, as well as individual school relationships. Following an ideation-to-action framework, positive school experiences may protect against risk factors related to the development of suicidal ideation (e.g., disconnectedness and burdensomeness) as well as provide opportunities to intervene with students before they move from ideation to action (i.e., attempt).

In the following sections, we discuss practice implications for recognizing idioms of stress and considering cultural sanctions of suicide. We also describe how each school-related stressor may intersect with cultural risk factors and connect to intervention with consideration of school-related protective factors. Importantly, Chu et al.’s (2010) model is based on differences between minoritized and mainstream (predominantly White, heterosexual) groups; however, the current research was not limited to differences but rather inclusive of risk and protective factors that could benefit all students. Thus, while further research is needed to both expand and substantiate the proposed model, it can serve as a preliminary roadmap for practice and future research focused on culturally sensitive approaches to suicide prevention in schools.

Idioms of Distress

Idioms of distress relate to cultural variations in likelihood for expressing suicidality (e.g., hidden ideation), forms of expressing suicidality, and the methods or means for suicide attempts (Chu et al., 2010). Greater awareness of cultural variations in presentation of symptoms and risk identification procedures will better prepare providers and stakeholders within the school setting. For example, while acculturation and intercultural conflict are contributors to elevated risk of STB across many R/E minoritized groups (Goldston et al., 2008), Asian American and Hispanic adolescents often encounter unique challenges around intergenerational conflict as compared with Black or American Indian youth (Goldston et al., 2008); such challenges, including both inter- and intrapersonal ones, may indicate elevated risk.

School providers should also be aware of cultural variations in help-seeking behaviors and treatment engagement. Culture mediates preferences for support (e.g. seeking family or clergy support over mental health professionals), preferences for treatment (e.g. integration of spiritual healing), willingness to engage with mental health professionals, and disclosure of suicidal thoughts (Goldston et al., 2008). These are important elements to consider when assessing risk, especially given the limitations of assessment tools for detecting cultural variations. While we are not aware of any culturally informed risk assessments designed for schools, the Cultural Assessment of Risk of Suicide (CARS; Chu et al., 2018) includes culturally bound stressors. (Notably, this assessment has been explored in adult samples only.)

Consideration of the racial and ethnic disparities in connections to care outside of school (e.g., Cummings et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018) is also critical to consider when making community referrals. By partnering with stakeholders from R/E minoritized communities in this process, school-based providers may expand their awareness and understanding of cultural factors relevant to suicide risk assessment, intervention, and connection to care that is sensitive to all populations. School-family-community partnerships include collaborative relationships between school personnel and family members as well as individuals from community-based organizations (e.g., universities, businesses, religious organizations, libraries, and mental health and social service agencies; Bryan & Henry, 2012). Extensive research demonstrates improved academic outcomes for students when school personnel, families, and communities work together to meet the needs of students (Arriero & Griffin, 2018; Jeynes, 2011), warranting additional work that focuses on implications for social-emotional and suicide specific outcomes.

Cultural Sanctions