Abstract

Cordyceps (Cordyceps militaris) exhibits many biological activities including antioxidant, inhibition of inflammation, cancer prevention, hypoglycemic, and antiaging properties, etc. However, a majority of studies involving C. militaris have focused only on in vitro and animal models, and there is a lack of direct translation and application of study results to clinical practice (e.g., health benefits). In this study, we investigated the regulatory effects of C. militaris micron powder (3 doses) on the human immune system. The study results showed that administration of C. militaris at various dosages reduced the activity of cytokines such as eotaxin, fibroblast growth factor-2, GRO, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. In addition, there was a significant decrease in the activity of various cytokines, including GRO, sCD40L, and tumor necrosis factor-α, and a significant downregulation of interleukin-12(p70), interferon-γ inducible protein 10, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β activities, indicating that C. militaris at all three dosages downregulated the activity of cytokines, especially inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Different dosages of C. militaris produced different changes in cytokines.

Keywords: Cordyceps militaris, Cytokine reduction, Human cytokines, Human trial, Immune system

1. Introduction

Cordyceps militaris, also known as north Cordyceps sinensis, is the most common species of the genus Cordyceps (Division: Ascomycotina; Order: Hypocreales; Family: Clavicepitaceae) [1]. The bioactive components in C. militaris such as cordycepin, cordyceps polysaccharide, cordycepic acid, and superoxide dismutase [2] have been reported to possess various biological properties, including antioxidant [3], antineoplastic [4], antiaging [5], hypoglycemic [6], and inhibition of inflammation [7]. Although many studies have documented the biological activity of C. militaris, most of these have focused on in vitro or animal models, which are unable to reveal the impact of these components on immune regulation because of the cutoff of communication between immune cells.

In elucidating the action mechanism of the phytochemicals in C. militaris, we conducted a human study to gain a better understanding of regulatory effects of this special Cordyceps species. Twelve young volunteers were selected as participants for oral administration of C. militaris submicron powder. A liquid chip scanner was used to determine the content changes of 39 cytokines and to explore regulatory functions and signal pathways of C. militaris with respect to the immune system; in addition we also evaluated its antitumor activity. A cell communication network of the human immune system was established based on the experimental data.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

C. militaris was purchased from Yancheng Shennong Functional Food Co., Ltd., dried, and crushed into a powder form with a particle size smaller than 48 μm in diameter. A 3K15 high-speed refrigerated centrifuge was purchased from Sigma Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). A light biochemical incubator was purchased from Donglian Ltd. Co. (Harbin, China). The human kit with 96 enzyme-labeled plates and the liquid chip scanner were purchased from Millipore Corporation (Billerica, MA, USA).

2.2. Participants

Volunteers for the study were five male and seven female healthy college students aged from 20 years to 21 years; the average male and female body weights were 65 ± 2 kg and 48 ± 2 kg, respectively. The body mass index of male and female volunteers was in the range of 21.14–21.46 and 17.96–18.36, respectively. All volunteers signed informed, responsibility, and safety agreements and were randomly divided into three dosage groups of four students. All experiments were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and all experimental protocols were approved by the ethical committee for human trials of the College of Biotechnology and Food Science, Tianjin University of Commerce (Tianjin, China). The volunteers were required to follow a schedule of regular and normal hours of work and rest, as well as strict restrictions on strenuous exercise, cigarettes smoking, or alcohol. Except for nonfunctional meals provided for these volunteers, any other functional foods, drugs, or beverages were prohibited. During the study period, all volunteers stayed in a relaxed environment to protect them from sources of stress [8].

During the 2-day period of experimental duration, the volunteers were provided with unbiased meals on the 1st day and with the same meals with the addition of the test foods on the 2nd day. Blood samples were collected at 2 PM every day, incubated at 4 °C for 16 hours, centrifuged at 3200g for 10 minutes, and stored at −70 °C for future use. Test results from the 1st day were used as the control.

2.3. Administration dosages and methods

In this study, the submicron powder at high, medium, and low dosages (3, 1.5, and 0.5 g) was mixed with water to form a paste, respectively. The paste was steamed for 15 minutes before oral administration to the volunteers.

2.4. Cytokine detection

A Millipore human kit with 96-well enzyme-labeled plates was used to detect the following cytokines: epidermal growth factor (EGF), eotaxin, fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), Flt-3L, fractalkine, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), growth regulated oncogene (GRO), interferon-α2 (IFN-α2), IFN-γ, interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12(p40), IL-12(p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IFN-γ inducible protein 10 (IP-10), monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 (MCP-1), MCP-3, macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, sCD40L, sIL-2Ra, transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TNF-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The content-change rates of these cytokines can be expressed using following equation:

| [1] |

2.5. Data analysis

SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis of experimental results using t test. Significant differences or extreme significant differences were considered at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of low dosage of C. militaris on cytokines

Following the administration of C. militaris at the 0.5 g dosage, no obvious changes were observed in 19 cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12(p40), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, MCP-3, MIP-1α, sIL-2Ra, and TNF-β, whereas the concentrations of IFN-γ in blood samples taken from the volunteers increased from the 1st day to the 2nd day, which suggested upregulation of IFN-γ. By contrast, the concentrations of EGF, eotaxin, FGF-2, Flt-3L, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFN-α2, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IP-10, MCP-1, MDC, MIP-1β, sCD40L, TGF-α, TNF-α, and VEGF in blood samples from the volunteers decreased from the 1st day to the 2nd day, which suggested that these cytokines were downregulated (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Administration of Cordyceps militaris at the 0.5 g dosage and the rate of change in the concentration of different cytokines. 1. Epidermal growth factor; 2. Eotaxin; 3. Fibroblast growth factor-2; 4. Flt-3L; 5. Fractalkine; 6. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; 7. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; 8. GRO; 9. Interferon-α2 (IFN-α2); 10. IFN-γ; 11. Interleukin-1α (IL-1α); 12. IL-1β; 13. IL-1ra; 14. IL-2; 15. IL-3; 16. IL-4; 17. IL-5; 18. IL-6; 19. IL-7; 20. IL-8; 21. IL-9; 22. IL-10; 23. IL-12(p40); 24. IL-12(p70); 25. IL-13; 26. IL-15; 27. IL-17; 28. IFN-γ inducible protein 10; 29. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1); 30. MCP-3; 31. Macrophage-derived chemokine; 32. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α); 33. MIP-1β; 34. sCD40L; 35. sIL-2Ra; 36. Transforming growth factor-α; 37. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); 38. TNF-β; and 39. Vascular endothelial growth factor. Similarly hereinafter.

Results of the t test revealed a significant decrease in eotaxin, FGF-2, GRO, and MCP-1, suggesting that C. militaris at a dosage of 0.5 g can downregulate these four cytokines dramatically (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cytokines exhibiting significant changes after Cordyceps militaris administration at a dosage of 0.5 g.

| Cytokines | C Control/(pg/mL) | C Experimental/(pg/mL) | Average change rate/% | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eotaxin | 52.3 | 55.7 | 67.8 | 75.5 | 42.6 | 18.6 | 24.2 | 55.7 | −1.095* | 0.052↓ |

| FGF-2 | 34.9 | 3.8 | 36.5 | 15.3 | 8.0 | 3.49 | 17.3 | 5.9 | −1.538* | 0.095↓ |

| GRO | 428 | 355 | 149 | 438 | 409 | 210 | 66.7 | 309 | −0.597** | 0.045↓ |

| MCP-1 | 105 | 100 | 155 | 226 | 78.6 | 61.1 | 111 | 154 | −0.459** | 0.018↓ |

p < 0.05, significant difference.

p < 0.01, extreme significant difference.

FGF-2 = fibroblast growth factor-2; MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; ↓ = decrease in the mean concentration. Similarly hereinafter.

3.2. Impact of medium dosages of C. militaris on cytokines

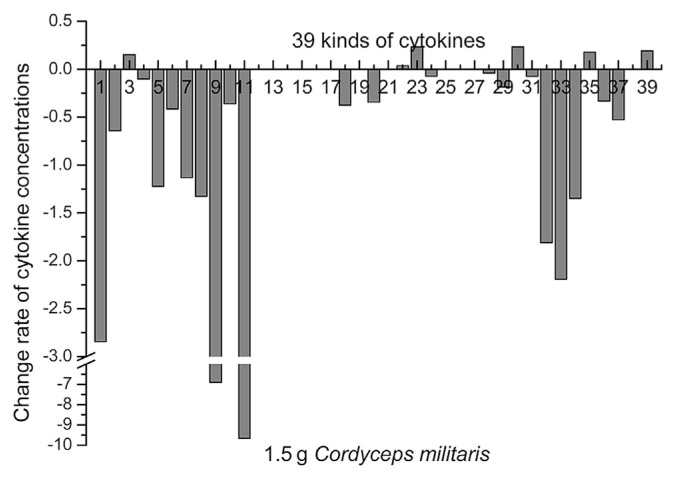

The administration of C. militaris at a dosage of 1.5 g produced no observable changes in Flt-3L, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12(p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IP-10, MDC, or TNF-β, whereas the concentrations of FGF-2, IL-10, IL-12(p40), MCP-3, sIL-2Ra, and VEGF in blood samples from the volunteers were much higher on the 2nd day, suggesting that these cytokines were upregulated (Fig. 2). In addition, the concentrations of EGF, eotaxin, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFN-α2, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, sCD40L, TGF-α, and TNF-α in blood samples from the volunteers decreased on the 2nd day, suggesting that these cytokines were downregulated.

Fig. 2.

Administration of Cordyceps militaris at the 1.5 g dosage and the rate of change in the concentration of different cytokines.

Results of the t test revealed a significant decrease in GRO, sCD40L, and TNF-α levels, which indicated that C. militaris at a dosage of 1.5 g can downregulate these three cytokines (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cytokines exhibiting significant changes after Cordyceps militaris administration at a dosage of 1.5 g.

| Cytokines | C Control/(pg/mL) | C Experimental/(pg/mL) | Average change rate/% | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRO | 519 | 483 | 340 | 340 | 105 | 153 | 156 | 232 | −1.327* | 0.022↓ |

| sCD40L | 24,017 | 24,017 | 24,017 | 18,756 | 5454 | 24,017 | 14,456 | 8070 | −1.347** | 0.084↓ |

| TNF-α | 3.7 | 4.4 | 8.4 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 1.5 | −0.525** | 0.065↓ |

TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α.

3.3. Impact of high dosages of C. militaris on cytokines

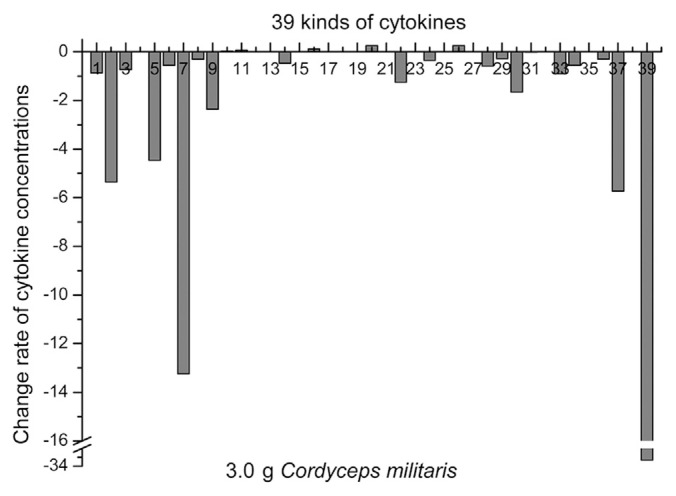

The administration of C. militaris at a dosage of 3.0 g did not result in obvious changes in Flt-3L, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12(p40), IL-13, IL-17, MDC, MIP-1α, sIL-2Ra, or TNF-β, whereas the concentrations of IL-4, IL-8, and IL-15 in blood samples from the volunteers were much higher on the 2nd day compared with that of the 1st day, suggesting that these cytokines were upregulated (Fig. 3). However, the concentrations of EGF, eotaxin, FGF-2, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFN-α2, IL-2, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IP-10, MCP-1, MCP-3, MIP-1β, sCD40L, TGF-α, TNF-α, and VEGF in blood samples from the volunteers were lower on the 2nd day, which suggested that these cytokines were downregulated.

Fig. 3.

Administration of Cordyceps militaris at the 3.0 g dosage and the rate of change in the concentration of different cytokines.

Results of the t test revealed a significant decrease in IL-12(p70), IP-10, MCP-1, and MIP-1β levels, indicating that C. militaris at high dosages can downregulate these four cytokines (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cytokines exhibiting significant changes after Cordyceps militaris administration at a dosage of 3.0 g.

| Cytokines | C Control/(pg/mL) | C Experimental/(pg/mL) | Average change rate/% | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12(p70) | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.92 | 1.7 | 1.5 | −0.364* | 0.026↓ |

| IP-10 | 502 | 497 | 358 | 575 | 435 | 180 | 298 | 450 | −0.599** | 0.099↓ |

| MCP-1 | 127 | 101 | 80.7 | 129 | 87.9 | 91.4 | 70.2 | 87.6 | −0.293** | 0.064↓ |

| MIP-1β | 43.5 | 40.3 | 25.9 | 5.7 | 26.9 | 21.4 | 23.9 | 1.86 | −0.912** | 0.097↓ |

IL-12(p70) = interleukin-12(p70); IP-10 = interferon-γ inducible protein 10; MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP-1β = macrophage inflammatory protein-1β.

4. Discussion

In this study, the effects of administering C. militaris at low, medium, and high dosages (0.5 g, 1.5 g, and 3.0 g, respectively) were analyzed. Downregulation by C. militaris was observed for different chemokines at all three dosages, including eotaxin, FGF-2, GRO, and MCP-1 at low dosage; GRO, sCD40L, and TNF-α at medium dosage; and IL-12(p70), IP-10, MCP-1, and MIP-1β at high dosage. This regulatory effect is important because chemokines play important physiological and pathological roles in many diseases, including inflammation, cancer, cancer metastasis, autoimmune diseases, hypersensitivity, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and other diseases associated with the involvement of chemokines and their receptors [9–14]. C. militaris at low and medium dosages was observed to downregulate the expression of GRO, which can promote the growth of epithelial cells and endothelial cells [15], whereas at the medium dosage C. militaris exerted a major influence on TNFs, such as sCD40L and TNF-α. TNF-α can bind to a specific receptor on the surface of the cell membrane to induce growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation [16]. At higher dosages, C. militaris significantly decreased the levels of IP-10 and MIP-1β. The concentration of IP-10, which originates in monocytes/macrophages and T cells, has been observed to increase in the neural system, liver, and spleen as an inflammatory response to virus infection, which is a consequence of immune response to pathogen invasion. However, recent studies have reported other factors that may contribute to excessive inflammatory responses and chemostatic effects, including diet and nutrition, which may lead to transplant rejection [11]. The chemokine MIP-1β has been found to regulate the migration of dendritic cells. A previous study demonstrated that increased and decreased expressions of MIP-1β were related to the early and late stages of colon cancer, respectively [17]. The administration of C. militaris at both low and high dosages was also observed to downregulate cytokine MCP-1. MCP-1 is the initial factor associated with inflammation, and can form a cascade reaction or mediate excessive inflammatory response by inducing and regulating other inflammatory factors [18]. MCP-1 can also boost the growth, survival, and migration of tumor cells [19]. Results of this study indicate that C. militaris can exhibit antitumor functions by downregulating the activity of these cytokines.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the consumption of C. militaris at three dosages can significantly reduce the concentrations of cytokines, resulting in downregulation of the immune system in the body. Different dosages of C. militaris produced significant changes in different cytokines and in cell communication. The strongest immunoregulatory role of C. militaris appeared to occur with administration of the medium dosage. These results suggest that C. militaris can downregulate the immune system by reducing inflammatory chemokines such as IP-10, MCP-1, and eotaxin, which can in turn induce the migration of immune cells including macrophages and monocytes to the infection locations under inflammatory environments as well as by stimulating the secretion of TNF-α and by the activation of nuclear factor-κB. However, the significant reduction of TNF-α also suggests decreased activity of macrophages and monocytes. All of these results indicate that C. militaris at the various dosages can reduce the excessive immune responses, which is expected to produce beneficial effects against some diseases resulting from appropriate diet or autoimmunity, including an inhibitory role in tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from China Agriculture Research System (CARS-24).

Funding Statement

The authors acknowledge financial support from China Agriculture Research System (CARS-24).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shao L. Fungal taxonomy. Beijing: China Forestry Press; 1984. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xia C, Sun W, Liu X. Research advances on bioactive constituents of cordyceps. Edible Fungi China. 2009;28:3–7. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang Q, Hang X. Effect of Cordyceps militaris on rat metabolism of free radical. J Liaoning Teach Coll (Nat Sci Ed) 2002;4:104–6. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li J, He Z, Gong H, et al. Regulation of cordycepin on MMP-9/TIMP-1 production and TIMP-1 mRNA expression of Hela cells. J Mod Oncol. 2009;17:1615–8. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu W, Wang Y, Yong L, et al. Regulative effect of artificial northern Chinese caterpillar fungus on mRNA expression of GnRH cell in hypothalamus. Shanghai J Tradit Chin Med. 2009;43:72–4. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu L, Wang J, Tang X, et al. Hypoglycemia effect and the mechanism of Cordyceps militaris. Chin Pharmacol Bull. 2011;27:1331–2. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bin W, Shong L, Yu R, et al. Studies on the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating actions of the polysaccharide in the tissue culture of Cordyceps militaris. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 2003;14:1–2. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu S, Gao G, Luo X, et al. Evaluation of a functional food in improving human memory. Chin Prev Med. 2010;11:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma X. Chemokine with tumor and inflammation. J Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;14:287–90. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leng H. Current research development of the chemokine-10. Int J Immunol. 2006;29:241–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ji S. Research progress on IL-12 antitumor immunotherapy and gene therapy. Foreign Med Sci (Immunol Fascicle) 2000;23:42–6. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shin HY, Kuo YC, Hus FL, et al. Regulation of cytokine production by treating with Chinese tonic herbs in human peripheral blood mononuclear and human acute monocytic leukemia cells. J Food Drug Anal. 2010;18:414–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu S, Lou Y, Huang L. Research progress on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mechanism. Chin J Clin. 2012;6:2773–5. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chiu YW, Lo HJ, Huang HY, et al. The antioxidant and cytoprotective activity of Ocimum gratissimum extracts against hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity in human HepG2 cells. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21:253–60. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ni W, Xiong S. The GRO family: cell growth and related chemokines. Chem Life. 2002;22:8–10. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qiu C, Hou G, Huang D. Molecular mechanism of TNF-α signal transduction. Chin J Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;23:430–5. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao L, Jia L, He Y. The expression and significance of MIP-1β and S-100 protein in human colon cancer. Heilongjiang Med J. 2007;31:161–3. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Y, Zeng Y. Research progress on MCP-1 and its receptor CCR2 and cardiovascular diseases. J Mil Surg Southwest China. 2012;14:124–7. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Z, Wang Y. Development on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) in cancer. Clin Med J China. 2008;15:735–7. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]