Abstract

Cancer is a severe condition characterized by uncontrolled cell division and increasing reported mortality and diagnostic cases. In 2040, an estimated 28.4 million cancer cases are expected to happen globally. In 2020, an estimated 19.3 million new cancer cases (18.1 million excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) had been diagnosed worldwide, with around 10.0 million cancer deaths. Breast cancer cases have increased by 2.26 million, lung cancer by 2.21 million, stomach by 1.089 million, liver by 0.96 million, and colon cancer by 1.93 million. Cancer is becoming more prevalent in Pakistan, with 19 million new cancer cases recorded in 2020. Food adulteration, gutkha, paan, and nutritional deficiencies are major cancer risk factors that interplay with cancer pathogenesis in this country. Government policies and legislation, cancer treatment challenges, and prevention must be revised seriously. This review presents the current cancer epidemiology in Pakistan to better understand cancer basis. It summarizes current cancer risk factors, causes, and the strategies and policies of the country against cancer.

Keywords: cancer epidemiology, healthcare policy, health services, burden of disease, food adulteration

Introduction

Cancer is one of the arduous diseases in which the entry and spread of irregular cell development to other body regions occur. Cancer signs and symptoms depend on cancer grade and type. There are many causes of cancer in which, mostly inherited genetic abnormalities (such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations) (1), infections (2), environmental factors (such as air pollution) (3), and bad lifestyle choices (such as smoking and high alcohol use) (4), may damage DNA and cause cancer. Fatigue, weight loss, skin changes, unusual bleeding, persistent cough, fever, lump, and tissue mass are the common symptoms of this disease (5). Different drug strategies have been developed to treat cancer in different conditions (6). Carcinoma affects the skin, lungs, breast, pancreas, and other organs. Sarcoma is a kind of cancer that affects the joints, muscle, fats, arteries, collagen, and other collagenous tissues of the body. Melanoma occurs in cells that make pigments in the skin (7). Lymphoma is a cancer of lymphocytes and leukemia occurs in the blood. Breast, leukemia, lips, and oral void space cancer are the top 3 tumors in all age groups and gender (8). According to Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center Lahore (SKMCH&RC) (9), the three most common cancers among young women are breast, ovary and uterine adnexa, and lip and oral hollow space cancers (9).

The three most common cancers among adult men are genital, intestine canal/anus, and lip and oral hollow space cancers (9). The most common cancers in adults, regardless of gender, are malignant neoplasms of the chest (10), lips and mouth (11), and intestine canal/anus (12). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) are the most frequent cancers in children (13). NHL in children may occur at any age, although it is more frequent in younger children. Adolescents are more likely to get HL (13). In children, there is no recognized cause of lymphoma. Young males with the least frequently diagnosed cancers are stomach, prostate, and mouth (14), while mature girls are commonly diagnosed with chest, cervical, and intestine canal/anus cancers (15).

The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging recommendations, Tumor nodes and metastasis (TNM), classifies malignancies into four stages from 0 to 4 and unstageable and no longer acceptable tumors, according to those of unstageable tumors to all publicly available cancer websites and registry (16). According to the reports, 0.8% of the 6,291 analytical cases were assigned to stage 0, 12.9% to stage-I, and 27.2% to stage II. There were 25.4% in stage III and 18.2% in stage IV, with 10.2% getting no level and 5.3% implacable (9).

Mechanisms of Cancers

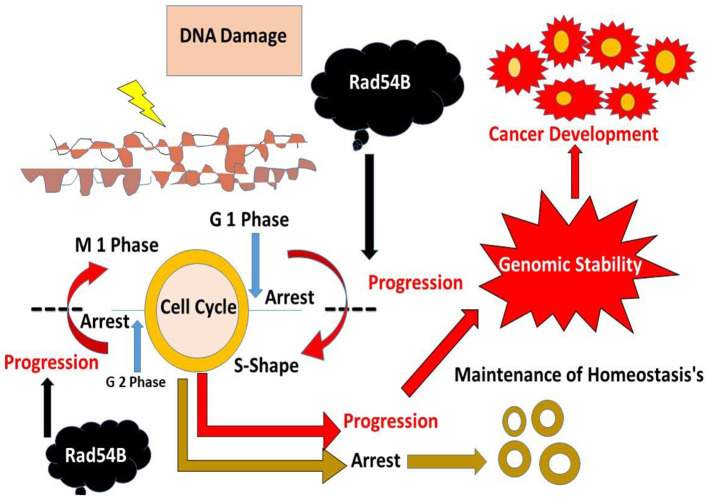

The cancer spreads as the normal processes that govern cell activity fail. A single mobile is becoming the father of many cells with unusual abilities or behaviors. It is often the result of cells accumulating genetic damage over time. Sustained proliferative signaling (17), cell death resistance (18), invasion and metastasis activation (19), and angiogenesis induction (20) are substitutes for cancer (21, 22). Figure 1 shows how most cells inside an individual are vulnerable to DNA damage. An individual's cells usually grow and divide in a highly controlled way known as a mobile cycle throughout their lives (23). It helps tissues to mature but also live a healthy life. Until a mobile phase cell divides, it must replicate its DNA (and hence its genetic code) so that each daughter cell has DNA equivalent to the parent cell. DNA replication is a complicated process prone to sequencing errors (24).

Figure 1.

The different mechanisms of cancer and its progression.

Cells are constantly found to have elements that could harm DNA (25). Exogenous factors, such as rays or chemicals in cigarette smoke, and endogenous indicators, such as free radicals or toxic metabolites, are present in the body (26). A carcinogen is a chemical or agent capable of producing cancer, even if not all cancer-causing substances destroy DNA immediately (27). Endogenous defensive mechanisms are less effective due to inherent genetic abnormalities, excessive amounts of exposure to external cancer-causing chemicals, and endogenous elements that damage DNA integrity (27). Unsuitable nutrients over the whole basis represent a disordered dietary microenvironment at the cell level. This can lead to an environment that encourages the buildup of DNA damage and, as a result, the development of cancer stated to the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) (22).

Global Burden of Cancer

Cancer is the leading killer, with more than 10 million deaths in 2020 (28, 29). According to the cancer statistics 2020 (29), breast cancer (2.26 million cases) (29), lung cancer (2.21 million cases) (29), intestine and rectum cancer (1.93 million cases), prostate cancer (1.93 million cases), carcinoma (1.20 million cases), and stomach cancer (1.20 million cases) are the most common cancers in the United States in 2020 (in terms of new cases; 1.09 million cases) (29). The shortage of oxygen in the body is the leading cause of cancer mortality. Breast cancer has affected almost 2.3 million people worldwide in 2020, including 0.685 million fatalities (30). The new cases and deaths are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

New cases and deaths for different types of cancer worldwide. (Data have been acquired from Global Cancer Statistics 2020).

| Cancer type | New cases (% of all sites) | Death (% of all sites) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | %age | Number | %age | |

| Gastrointestinal | 3,573,928 | 18.5 | 2,228,749 | 22.4 |

| Leukemia | 474,519 | 2.5 | 311,594 | 3.1 |

| Melanoma of skin | 1,198,073 | 6.2 | 63,731 | 0.6 |

| Brain/Nervous system | 308,102 | 1.0 | 99,840 | 1.0 |

| Pulmonary cancer | 2,707,406 | 14.7 | 2,019,937 | 20.3 |

| Genitourinary | 4,017,064 | 21 | 1,548,189 | 15.6 |

| Liver cancer | 1,401,450 | 7.3 | 1,296,183 | 13 |

| Mouth/Oral cavity cancer | 431,296 | 2.3 | 167,235 | 2.0 |

| Breast cancer | 2,261,419 | 11.7 | 684,996 | 6.9 |

| Multiple myeloma | 176,404 | 0.9 | 117,077 | 1.2 |

| Mesothelioma | 30,870 | 0.2 | 26,278 | 0.3 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) | 83,087 | 0.4 | 23,376 | 0.2 |

| Mesothelioma | 30,870 | 0.2 | 26,278 | 0.3 |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 34,270 | 0.2 | 15,086 | 0.2 |

| Others | 2,564,031 | 1,329,584 | ||

| Sum of all sites | 19,292,789 | 9,958,133 | ||

Cancer Situation in Pakistan

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has reported in Pakistan that the proportion of newly diagnosed cancers is 0.18 million, the number of cancer fatalities is 0.11 million, and the number of prevalent cases (5 year) is 0.32 million (31). In Asia, Pakistan regionally represents the most significant breast cancer rate (32). Breast cancer has grown increasingly frequent in Pakistan, with one out of nine women now having a lifetime risk of the disease (33). Pakistan has one of the highest breast cancer mortality rates globally (34). Lips and mouth cancer is the 2nd most frequent malignancy in Pakistan and the top among males when both genders are included (15.9%) (35). The increased usage of smokeless tobacco, such as areca nut, can increase the burden of severe lung tumors (SLT) (36). SLT is a collection of over 30 low and high-toxic substances (37). The list of cancers, number of deaths, and new cases in Pakistan in 2020 are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

New cancer cases and death for different types of cancer in Pakistan (Data have been acquired from Global Cancer Statistics 2020).

| Cancer type | New cases (% of all sites) | Death (% of all sites) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | %age | Number | %age | |

| Gastrointestinal | 23,220 | 14.87 | 21,077 | 18.08 |

| Leukemia | 8,305 | 4.7l | 6,261 | 5.3 |

| Melanoma of skin | 502 | 0.28 | 290 | 0.25 |

| Brain/Nervous system | 4,770 | 2.7 | 3,934 | 3.4 |

| Pulmonary tract cancer | 19,008 | 10.61 | 14,488 | 12.31 |

| Genitourinary | 25,241 | 11.35 | 11,026 | 9.46 |

| Liver Cancer and Gallbladder | 8,372 | 4.7 | 7,739 | 6.6 |

| Mouth/Oral cavity cancer | 20,620 | 10.01 | 11,761 | 10.07 |

| Breast cancer | 25,928 | 14.5 | 13,725 | 11.7 |

| Multiple myeloma | 1,978 | 1.1 | 1,726 | 1.5 |

| Mesothelioma | 41 | 0.02 | 34 | 0.03 |

| Non and Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) | 8,305 | 4.63 | 4,550 | 4.36 |

| Mesothelioma | 41 | 0.02 | 34 | 0.03 |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 77 | 0.04 | 51 | 0.04 |

| Others | 31,980 | – | 20,453 | |

| Sum of all sites | 178,388 | – | 117,149 | – |

Potential Risk Factors of Cancer in Pakistan

Diet and Nutrition

Malnutrition was common among advanced cancer patients (38). The nutritional deficiency was linked to poor clinical outcomes (38). According to numerous studies, poor nutrition is prevalent among cancer patients, with rates ranging from 31 to 97% (39–42). Malnutrition can result in impaired immunity (43), higher infection rates (44), inadequate reaction and endurance for therapy (45), higher healthcare costs (46), worse quality of life (47), and shorter survival durations (48).

Dietary Consumption

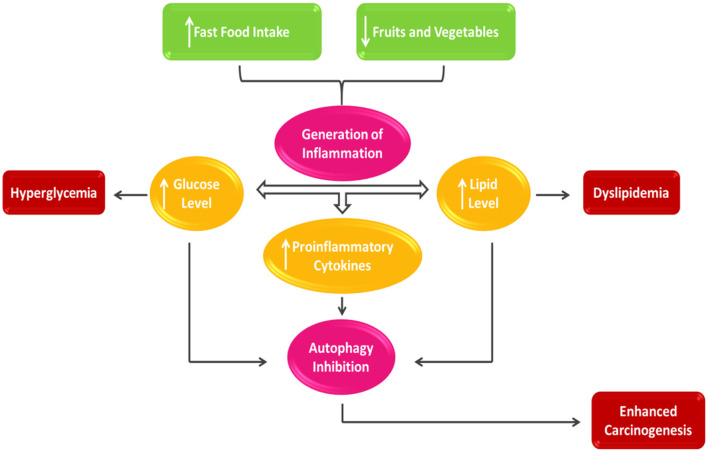

Cereals continue to be the mainstay of the Pakistani diet, accounting for 62% of total energy (49). Pakistan has a high level of dietary patterns compared to other Asian countries (50). However, there is a lack of diet quality and fish and meat consumption (51). Fruit and fresh vegetables, which are sensitive to local seasonal availability, are similarly limited due to the country's lack of established marketing facilities. Micronutrient deficiency disorders in Pakistan are likely to be caused by fluctuations in the availability of these essential foods (52). Figure 2 shows the link between dietary consumption and cancer.

Figure 2.

Nutrient intake and cancer prognosis.

A healthy diet rich in fruits and vegetables has been related to a decreased risk of cancer. Consumption of vegetables reduces cancer risk, according to American Institute of Cancer Research (AICR) (53). As a result, it is assumed that vegetables contain chemopreventive chemicals. Isothiocyanates and myo-inositol have been the emphasis. Isothiocyanates, found as glucosinolates in green vegetables like mustard, cabbage, lettuce, radish, and cauliflower, seem plentiful (54). Beans, cereals, and nuts all contain myo-inositol (55). These compounds inhibited the enzymatic activity of 4-(N-Methyl-N-nitrosamine)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (56, 57).

Epidemiological and experimental studies indicate that Brussels sprouts, kale, broccoli, and cabbages have anticancer properties (58). Sulforaphane, a phytochemical found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, sorghum and cabbage, has anticancer characteristics (58, 59). Cabbage has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that could help prevent cancer (60). Foods that increase the bioavailable content of non-heme iron and alternative treatments for cancer patients can all benefit from fresh cabbage juice, whether made individually or combined with other vegetables like carrot and celery (61, 62) Thiocynate obtained from the hydrolysis of Brassica oleraceae has anticancer and antioxidant properties (60, 63). Cauliflower and cruciform vegetable intake has reduced cancer rates (64). Radish sprouts may have a more substantial chemoprotective effect against carcinogens than broccoli sprouts (65). Antimutagenic efficacy of aqueous extract of salted radish roots against Salmonella typhimurium TA98 and TA100 (66). Radish sprouts have a high concentration of glucoraphanin, glucosinolates that hydrolyze to produce sulforaphane, a potent inducer of phase 2 detoxification enzymes with anticancer properties (65). Due to the indoles present in turnip, it has anti-tumorigenic properties (67). Substantial antimutagenic factors and hydroxyl radical scavengers have been found in Turnip seeds (68).

Flavonoids, also present in tomatoes, have been shown to prevent carcinogenesis in vitro, and there is strong evidence that they can do so in vivo (69, 70). In considerable amounts, Tomato leaf extract includes isolated active components with anticancer activity (70). Cardioprotection, anti-inflammatory, Antimutagenic, and anti-carcinogenic qualities are only a few of the biological advantages of tomato lycopene (71). Lycopene-rich tomatoes and tomato products have decreased the risk of chronic diseases such as cancer and heart disease (71). Cancer might be prevented or delayed by delaying or inhibiting the steps leading to genetic damage or activating preventive systems (72). The large-scale (α-Tocopherol and β-carotene) cancer prevention studies and carotene and retinol effectiveness trial intervention studies found that anyone who gained early plasma or potency layers of carotenoid had a lower risk of developing lung cancer (73, 74). Those with greater pre-intervention carotene concentrations in their plasma or diets reduced cancer incidence (75). A high-carotene diet may also benefit cancer treatment (76, 77).

Adulteration

Pakistan is indeed an agricultural land, and farmland has always significantly influenced the nation's economy with cattle (78). Pakistan produced 42.199 million tons of milk last year, with buffaloes accounting for 62.17% of total milk output, cows 34.21%, sheep, goats, and camels 3.60%. Pakistan's milk production and delivery infrastructure are antiquated and insufficient, despite the country's favorable position among dairy-producing countries (79). The irregular private sectors, which are made up of many agents such as sellers, collectors, mediators, processors, merchants, and dairy stores, perform a specific function at a different stage of the production process and manage it (80). Pakistan's dairy industry is beset by many issues, including a scarcity of industrial milk production, milk expertise, and legal and technological resources (81).

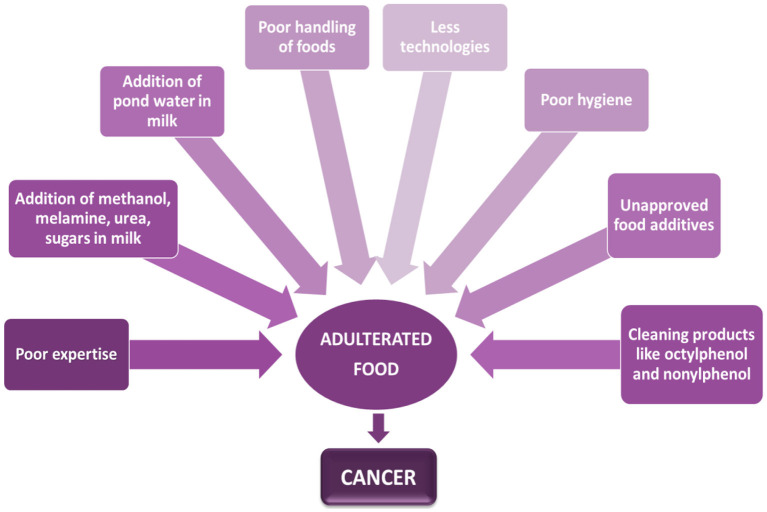

Moreover, its lack of decent inspection is the system's biggest overlooked flaw. At practically every stage of the marketing process, testing is just about non-existent (82). On the other hand, rising inflation and poverty levels have made most Pakistani consumers budget-conscious. As a result, open raw milk has a higher demand than pasteurized milk (83). Different factors are shown in Figure 3. Water is perhaps the most basic and transparent adulteration in milk and is applied to boost the volume of a valuable product. Still, dirty water puts people's health in danger from waterborne illnesses (84).

Figure 3.

Association between contaminated food and cancer.

Owing to decreased milk output, milk yield in Pakistan is reduced by 55% throughout the summer (85). However, when milk production is abundant in contrast to the spring, price increases of up to 60% are usual. Water is blended into the whole dairy throughout the summer to enhance the milk available to meet demand (86, 87). Because pond water is an excellent nitrogen resource, some unscrupulous people add it to milk to increase the relative density. Human ingestion of these water-spoiled milk can induce gastrointestinal problems, mainly in the elderly, or pose significant health risks to children and infants who regularly eat dairy (88). Table 3 shows the many cancers induced by various foodstuffs.

Table 3.

Linkage of certain foods to various malignancies.

| Food items | Type of cancer | References |

|---|---|---|

| High intake of red meat | Colorectal cancer | (89) |

| High salted vegetables/food | Gastric cancer | (90) |

| Ultra-processed food and drinks | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | (91) |

| High fat | Breast cancer | (92) |

| Low vitamin C, E rich foods | Skin cancer | (93) |

| High alcoholic beverages intake | Lung cancer | (94) |

| High carbs | Brain tumor | (95) |

| High fat | Liver cancer | (96) |

To avoid milk from spoiling during delivery, especially in hot weather, it is refrigerated (the ice used may be contaminated) (97). Milk is also important because it has whey protein with many health benefits (98). Methanol, melamine, urea, and sugars can be illegally polluted in milk (97). In summers, H2O2 protects milk whenever the heat is exceptionally high. Hydrogen peroxide damage to stomach cells can cause gastritis, bowel inflammation, and severe diarrhea (99). Cleaning products used to clean milk also cause cancer (86).

Fast Food and Junk Intake

Fast food is food that can be prepared and served quickly (100). They're known for offering rich, delectable food at affordable costs. Nonetheless, many people nowadays, especially the young, like fast food like burgers, chicken wings, pizza, and shawarma (101). Fast food's success can be attributed to a variety of things. The changing level of living is among the essential variables. Most individuals spend extra shifts and even whole study hours to make finances meet. They won't have time to shop for supplies or prepare delectable meals. The increasing number of young, wealthy people is one factor. Most people in most countries spend a lot of money on fast food since they are primarily young (102). Children are regularly exposed to fast food advertisements on television and the Internet (103). Youngsters enjoy dishes with vivid shades and miniature gadgets, although full of fat, salty, or artificial sweeteners. Fast-food consumption has increased dramatically in Pakistan (104). Client meal preferences are impacted by several factors, including client desire to dine out (105), networking (106), globalization (107), a need for university undergraduates (108), the convenience of Pakistani households with two incomes, and a variety of other factors (109). People are eating in a new way in terms of global with the rising relative importance of snacks, burgers, pizzas, and fizzy beverages (110). As previously stated, the need for food is linked to urban culture, and development is one of the factors contributing to changing lifestyles, increasing wealth, and the independence of young people (111).

Many individuals like eating fast food regularly, even though they may be unaware of its negative health impacts. One of the ailments caused by consuming fast food is cancer (112)People in Pakistan often buy and eat fast food between 6 and 9 p.m., as per findings of a study (113). Due to its delectability, fast is consumed by single and joint households in Pakistan. The nuclear family unit is more cost-conscious than the common family unit. Fast food is popular among the general public, and many people choose to dine outdoors in their houses (114). People who were overweight were more likely to eat fast food at home (115).

As a consequence, dining out is a better choice (116). There is conflicting evidence of a relationship between food quality and prostate cancer (117). According to recent research, taking in more food, fruits, and vegetables is linked to a decreased incidence of prostate cancer (118). The low-fat, high-vegetable, and fruit-intake diet can help to reduce the risk of prostate cancer (119). In several studies, a high-fat diet, particularly red meats and dairy products, has increased cancer risk (120). In South Asia, vitamin D insufficiency is relatively frequent. According to studies, 70–97% of Pakistan's primary population is deficient in vitamin D, with vitamin D insufficiency being more prevalent in cities (121). Vitamin D deficiency is widespread among Pakistan's general population (122). Vitamin D insufficiency was detected in 95% of women with breast cancer and 77% of healthy people in research from a prestigious cancer clinic in Pakistan (123). On the other hand, Chlebowski discovered no link between vitamin D deficiencies and cancer (62, 123). In earlier studies, vitamin D levels over 50 ng/ml have been linked to a 50% decreased risk of breast cancer (124, 125).

Gutkha and Paan

Tobacco use seems to have a long history in many regions, particularly India, Pakistan, other Asian nations, and America (126). There are around 28 carcinogenic chemical constituents in smokeless tobacco, the most common of which is nitrosamine (127). Due to a significant lack of information and awareness, most people utilize Paan and Gutkha (128).

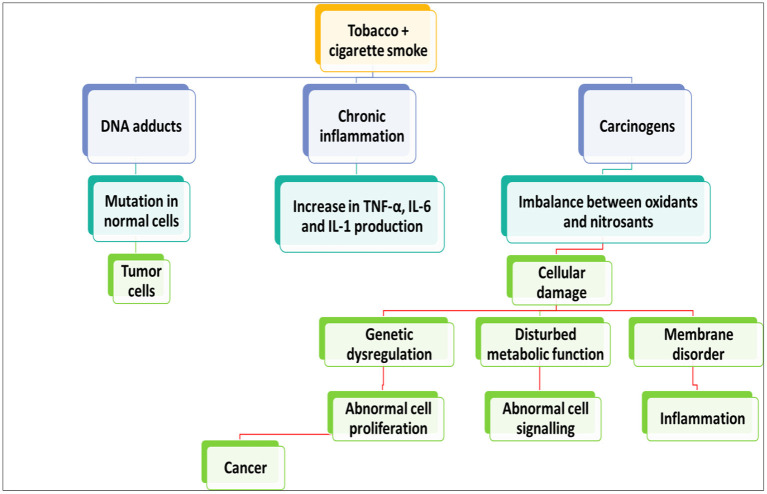

Children think of Gutkha as candy because of its pleasant flavor (36). Gutkha is widely assumed to be a mouthwash (36). However, its pleasant taste and smooth texture attract bacteria, leading to tooth disease (36). In most places where Paan and Gutkha are widely used, it is difficult to control their use, and their widespread use contributes to oral cancer. Tobacco, seed, soaked lime, herbs, and geek wrapped in flake are common ingredients in paan (129). Mouth Sub Mucous Carcinoma seems to be a chronic oral condition marked by mucus buildup in the mouth, pain, and necrosis of subcutaneous soft tissue. Oral cancer is relatively frequent in Pakistan, India, China, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia (130). Gutkha intake was already proven even to have carcinogenic and chromosomal effects. In certain circumstances, drinking rather than smoking significantly impacts oral cancer (131). In Pakistan, males and females had prevalence estimates of 21.3 and 19.3%, respectively. Pakistan is the second most common country where smokeless tobacco is used (132). Tobacco products have been connected to almost 90% of mouth cancer cases, which is critical in cancer formation (133). People who inhaled smoke more than 10 times per day have been found to have a higher chance of acquiring cancer than those who did not (134). Paan is consumed by 3.3–37.0% in Pakistan and India (36). Mouth cancer is the third least frequent cancer in Pakistan and India (135), behind breast and lung cancer. Breast cancer affects more females than males (136). The use of such items is considered normal in the culture. Despite their deliciousness, Gutkha, Chaalia, paan, toombak, and naswar lead to mouth cancer (36). Numerous studies show that these goods are consumed by 20–30% of individuals and teenagers in Pakistan, India, and Nepal (137, 138). In Karachi, Pakistan, 40% of the populace chews betel nut, areca nut, and tobacco products (139). According to a study, more than 74% of pupils in Karachi, Pakistan, consume digestible items regularly (140). Paan, chaalia, gutkha, naswar, and toombak were utilized 34.3, 34.7, 46.0, and 50% of the time in Sindh, Punjab, respectively Pathan, and Mohajir districts, according to a 2006 report (141). According to a study conducted a decade ago, gutkha was consumed on a regular basis by 46% of Karachi residents (142). Another study found that 35% of persons attending a medical care facility from Karachi, Pakistan, consumed paan, gutkha, or other oral tobacco frequently (143). The paan and gutkha processes have been proposed for humans, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Links between the oxidative and nitrosative induced damage and progression of cancer.

Before swallowing, paan, gutkha, and zarda are crushed, licked, or rubbed between gums and teeth. According to the World Health Organization, Nicotine mycotoxins constitute 76–91% of N-nitroso compounds (144). Paan and gutkha produce irritation of the oral mucosa, which stimulates T-cells and macrophages, resulting in the generation of prostaglandins. The pyogenic granuloma (PG) generation by buccal cavity keratinocytes is stimulated by areca nut extract, which is critical for tissue stiffness and malignancy. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-6, and growth factor-like have all been produced in areas of aggravation (36).

The nitrosamine in tobacco is biologically changed via cyp450 enzymes, which can form N-nitrosonornicotine, a carcinogenic solid that can cause DNA damage and, as a result, oral cancer (145). cytochrome P450 (CYP), Glutathione S-transferase (GST), and TNF represent cytochrome polymorphism, glutathione-s-transferase, and cancer necrosis signals.

Reduced salivation and mucus production have been observed in paan and gutkha eaters, decreasing the oral mucosa's normal microbiota and an increased risk of infection from Aspergillus (146). In laboratory animals, Paan and gutkha have been shown to cause stomach, mouth, throat, and laryngeal cancers. To mice, paan is just a melanoma agent (147). According to studies, mice given smokeless tobacco developed malignancies in their reproductive organs, ovaries, stomach, kidneys, abdomen, and lungs. As a result, smokeless tobacco is carcinogenic to the mouth and other bodily systems (148).

Micro-Nutrients Deficiency

A deficiency of vitamin A may cause metaplastic changes in the nasal passage (149). Both inheritance and the effects of harmful practices such as smoking and eating a diet lacking plant-based items increase the chance of secondary cancer cells in many body regions (150). The relation between micro-nutrient deficiencies with cancers has been supplemented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Micro-nutrient deficits linked with a variety of cancers.

| Type of cancer | Micro-nutrients | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Vitamin D3 | In breast cancer patients, vitamin D insufficiency is a typical occurrence. | (151) |

| Selenium | In 2014, a meta-analysis identified a link between selenium blood levels and the risk of breast cancer. | (152) | |

| Folate, zinc, beta-carotene | In a 2014 investigation, many genetic abnormalities and/or deficits in folate, zinc, and beta-carotene were linked to triple-negative breast cancer development, especially when they were identified together. | (153) | |

| Iodine | Iodine is a mineral found in the thyroid and breast tissue that aids in preventing breast cancer. Low iodine levels may be considered a risk factor for breast cancer due to the high prevalence of hypothyroidism in breast cancer patients. | (154) | |

| Prostate cancer | Zinc | A study of Nigerian prostate cancer patients identified a relationship between zinc deficit and prostate cancer and selenium and vitamin E deficiency. | (155) |

| Vitamin E and trace minerals | As previously indicated, a study on Nigerian males with prostate cancer was undertaken. According to this study, prostate cancer patients exhibited significantly decreased levels of whole blood superoxide dismutase (SOD), vitamin E, serum selenium, and zinc. AS A RESULT, Vitamin E, zinc, and selenium deficiency may be risk factors for prostate cancer. | (155) | |

| Selenium | Increased plasma/serum selenium levels (170 ng/mL) were found to lessen the incidence of prostate cancer in a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of selenium and prostate cancer. | (156) | |

| Vitamin D3 | Vitamin D3 25(OH) D concentrations were inversely correlated with prostate cancer risk but not vitamin D–related polymorphisms or parathyroid hormone. This suggests a relationship between low vitamin D3 blood pathology and a higher risk of prostate cancer. | (157) | |

| Colon cancer | Folic acid | In colorectal cancer treatment, folic acid is a contentious vitamin. Even though high folate levels have been linked to a lower risk of colorectal cancer, too much folate can stimulate cancer growth. | (158) |

| Selenium | In animal studies, selenium deficiency has been shown to aggravate colitis and speed tumor formation and progression in inflammatory carcinogenesis. | (159) | |

| Vitamin D | Many colorectal cancer patients have vitamin D3 insufficiency and deficiency. | (160) | |

| Fiber, low fruit and vegetable, high red and processed meat intake | Even if not a single nutrient, it has long been known that a diet poor in fruits and vegetables, fiber, and red and processed meat intake is related to the development of colorectal cancer. | (161) | |

| Lung cancer | Selenium | Several epidemiological studies have found that persons with low selenium levels in their blood had a higher risk of lung cancer, albeit the findings are contradictory. Research done in the southeast United States showed that lower-income and black Americans were more likely to get lung cancer. | (162) |

| Vitamin A | Cigarette smoking has been linked to the development of lung cancer. Cigarette smoking has been shown to lower retinoic acid levels in the lungs of rats and increase the growth of precancerous and cancerous tumors. | (163) | |

| Vitamin D3 | Vitamin D3 deficiency is common in lung cancer patients, ranging from mild to severe. | (160) | |

| Zinc | Human investigations on zinc deficiency and lung cancer are few and far between. Zinc deficiency has been demonstrated to cause DNA instability and undermine its integrity in cell culture studies on human lung fibroblasts, suggesting that it may have a role in preventing DNA damage and cancer. | (164) |

Vitamin C insufficiency is common among south Asians and one of the contributing causes (165). Vitamin C levels in the blood of Indians and Pakistanis living in India and Pakistan have dropped dramatically (165). The primary cause might be a lack of vitamin C rich fruits and vegetables, especially among individuals from poor socioeconomic categories (166). Patients with advanced disease receiving chemo or immunotherapy may be at a higher risk of Vitamin C depletion due to increasing demands rather than a lack of consumption (167). Women had more significant amounts of ascorbate than males, while active patients had more meaningful levels than sedentary people (168). Anemia is more common in people who have had a tumor recurrence and are in the later stage of the disease. That is, from 40% of individuals with early-stage colon cancer to almost 80% of patients with advanced cancer (169). An iron shortage can be fatal (usually related to bleeding), for those with low iron reserves or who are iron deficient somehow (170). Poverty, hunger, illiteracy, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of policy and law are all factors that contribute to the international development association (IDA) in Pakistan, according to several indicators (171).

According to the Pakistan National Nutritional Survey Key Report (PNNSKR), 2019, Vitamin D deficiency among children under five is a severe problem in Pakistan (172). Vitamin D insufficiency was found in a substantial percentage of people (62.7%) (173). Many youngsters (13.2%) suffer from a severe deficit. The incidence is somewhat higher (63.1%) among girls than it is among boys (62.4%) (174). Vitamin D insufficiency affects the majority of women of reproductive age (WRA) (79.7%), with 54.0% having a moderate deficit and 25.7% having severe deficiency (175).Vitamin D insufficiency is more prevalent in urban areas (83.6%) than in rural areas (77.1%) (175, 176). Vitamin A deficiency in a child under the age of five affects 51.5% of children, with 12.1% suffering from severe inadequacy (175, 177). Anemia is more common in those with a tumor recurrence at a later stage of their disease (from 40% of patients with early-stage colon cancers to almost 80% of patients with advanced disease) (175, 178). Iron deficiency can be absolute (typically caused by bleeding) or functional (caused by insufficient iron reserves) (175, 179). The prevalence of the disease is somewhat higher (51.7%) in males than in girls (51.3%) (174, 175). Adolescent females in rural regions are more likely than their urban counterparts to be anemic (175, 180). Zinc Deficiency in Children under the age of five zinc deficiency affects 18.6% of the population, with comparable rates in males and girls (175). Children in rural regions had a somewhat greater likelihood (19.5%) than in large cities (17.1%) (175, 181). Some cancer types related to different nutrients are supplemented in Table 4.

Challenges

No National Cancer Registry (NCR) in Pakistan can give the actual magnitude of the problem to create a health policy (182). Pakistan has a scarcity of nationally representative statistics. There are no long-term cancer patient data available. No comprehensive cancer control plan exists (182–184). There are currently no systematic cancer prevention and control health education efforts (183). The only national initiative was the National Program for Family Planning and Primary Health Care Pakistan (NPFPPH), which created 100 television advertisements to promote awareness of cancer's early warning signals (185). This, however, is not a long-term activity. In a few institutions, government agencies and activist groups have produced patient education materials (186); nevertheless, these activities have had limited impact. At the national, provincial, and municipal levels, a network of organizations is lacking. Low-cost public health methods to promote palliative care are lacking, particularly in low-resource areas. Due to a shortage of government money, planning was halted. Policymakers, the health sector, and other government institutions engaged in cancer care and treatment are less enthused. Pakistan lacks adequate policies and professionals for medical nutrition therapy (187). Vertical service delivery arrangements and poor performance accountability within the government are causing less efficiency and quality concerns in the health system. The private sector also duplicates services, primarily unregulated for quality treatment and cost. Pakistan's present health infrastructure are scattered and unidirectional (188). Current healthcare technology has not progressed (189). The current systems for determining the suitability of supplies, diagnostics, medications, and laboratory reagents are not based on evidence (189). There are concerns with medicine quality, pricing, and recommendations (189). The price of medicines is controversial between regulators and the pharmaceutical industry (190).

Programs and Policies in Pakistan

Cancer Treatment Program in Pakistan

The Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) has played an essential role in the health sector (191). PAEC now offers over 13 Nuclear Medicine and Oncology Centers equipped with Health and Nutrition having excellent facilities and offers to continue integrated programs to identify various malignancies and associated ailments (192). The primary disciplines accessible and in use in PAEC nuclear medical institutes are nuclear medicine, clinical oncology, surgical oncology, clinical labs, radiology, medical physics, and bioengineering (193). In addition to directing the operations of essential disciplines at several PAEC nuclear medical facilities, the Directorate General of Medical Sciences, PAEC Headquarter, is working on a Human Resource Development Program (HRDP). This would ensure that qualified and competent people in every aspect of cancer diagnosis and treatment are available (193).

Cancer Care Hospital and Research Centre (CCHRC) Pakistan

Its purpose is to provide high-quality, all-inclusive cancer treatment at no cost while addressing their physical, social, economic, and spiritual requirements (194). They also don't turn away any patients, accepting around 20,000 each year. This hospital was created due to a lack of chemotherapy facilities in Punjab 26/110, Baluchistan 1/12, Sindh 21/4, and KPK 14/35 (195). Chemotherapy takes 4–6 months, just like it did at SKMCH&RC.

Children Cancer Foundation Pakistan Trust (CCFPT)

This is intended for children only. This trust's mission is to offer cancer screening and treatment to all children, regardless of their financial situation. CCFPT was established years back with a strong direction and commitment to building a Children's Cancer Hospital (CCH) in Pakistan. Every child may receive quality cancer treatment and raise public awareness about childhood cancer (196).

National Cancer Data Base Pakistan (NCDBP)

In 2010, the NCDBP was established. The Pakistan Society of Clinical Oncology (PSCO) and its associated centers also work together (197). A cancer registry must be established to prevent and manage cancer. We now need an NCR that can offer information on the actual scope of the problem to establish health policy. The Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination (NHSRC) has tasked the Pakistan Health Research Council (PHRC) with establishing a cancer registry by affiliating all of the country's leading public and private institutions. Eight hospitals (Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Center, Karachi, Civil Hospital, Karachi, National Institute of Child Health, Karachi, Nishtar Hospital, Multan, Allied Hospital Faisalabad, Bolan Hospital, Quetta, Khyber Teaching Hospital, Peshawar, and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Rawalpindi) have been sending data to the Human Rights Commission Pakistan (HRCP) every quarter since May 2015 (198).

Pakistan Cancer Care Welfare Society (PCCWS)

This society's main objective is to provide financial assistance to the patient because it's challenging for someone diagnosed with cancer to manage expenses. However, Government assistance is needed too. Its mission is to help cancer patients medically, physically, socially, economically, and psychologically.

The PCCWS is a non-profit public welfare organization based in Pakistan to promote cancer awareness. PCCWS started in 2006 and presently has over 200 members and is currently striving to improve cancer awareness in lower Punjab (199). PCCWS follows the American Society of Cancer's monthly theme-based calendar system and organizes lectures, seminars, presentations, and campaigns throughout the lower Punjab, both rural and urban. PCCWS makes cancer literature in Urdu accessible, comprehensive, and up-to-date for local populations (199).

Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS)

The department houses Pakistan's World Health Organization (WHO) National Cancer Control Project. The Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences treats patients from Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, FATA, Gilgit-Baltistan, Kashmir, and Punjab (200). In addition, PIMS provides round-the-clock service to Parliamentarians, government officials, and judicial employees (32). All components have very visible and unambiguous signposting for services provided at PIMS to assist patients and their attendants (200). All cancers are treated at the oncology department with curative purpose chemotherapy. PIMS only have eight beds in its indoor section. Despite this, it regularly has more than 14 patients since it is the only government-run clinic in the region. The daily outpatient clinic sees 40 patients every day. Outpatient chemotherapy for 10–15 patients every day (200).

With the help of Saylani Welfare Trust and the EHSAAS Program, the patient's attendants are provided with free meals three times a day (201). In the “Shelter Home,” patient's attendants are also given a place to sleep at night (201). A “Sarai” is also available to accommodate the parents of pediatric patients (201).

Pakistan Society of Clinical Oncology (PSCO)

PSCO is a professional organization in Pakistan for cancer/oncology experts who have come together to fight cancer nationally (202). PSCO is the largest organization in the country, representing all of the experts who treat cancer patients (202). The society's mission is to promote and support the field of clinical oncology and associated sciences in cancer treatment (202). PSCO improves clinical oncology practice as a best-cost-effective cancer strategic approach in resource-constrained countries. PSCO encourages patients and the general public to learn more about cancer care by supporting prevention, screening programs, and accurate disease information. PSCO maintains relationships with other oncology societies, cancer forums, universities, patient groups, radiotherapy machine vendors, and the pharmaceutical business (202). Its main objectives are to assist and enhance the speciality of clinical oncology and related sciences engaged in cancer therapy and to serve the community using its diagnostic, therapeutic, and research capabilities (202).

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre (SKMCH&RC)

Thousands of underprivileged cancer patients received free comprehensive care at the clinic in 1989 (203). It is a humanitarian institute in Punjab formed by former cricketer and Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan and is primarily sponsored by donations from friends and well-wishers (203). It aims to serve as a model organization for improving the welfare of cancer patients via the use of current preventive and palliative therapy techniques for all cancer patients, regardless of their ability to pay, health care professionals and public education, and cancer research (203).

Surgical Oncology Society Pakistan (SOS-PK)

SOS-PK is a professional society promoting cancer patient treatment in Pakistan by enabling interaction and lifelong learning. Pakistan is subjected to a substantial illness load (204). The SOS-PK is Pakistan's leading national cancer surgeons' representative organization. It is a member of the ESSO (European Society of Surgical Oncology) and the Society of Surgical Oncology and USA's Global Cancer Surgery Leadership Forum Initiative (204).

The goals of SOS-PK (founded in Lahore in 2008) are to promote the advancement of cancer surgery education and training by improving communications among surgeons with a primary interest in the subject (204). SOS-PK accomplishes this by hosting conferences and symposia across the country to advocate for the highest possible quality of cancer care for patients, highlighting the necessity of a multi-sectoral approach and campaigning for the establishment of comprehensive cancer hospitals that provide all treatment under one roof and by raising public awareness, it is expected to encourage cancer prevention and early detection among the general population, health administrators, and healthcare providers (204).

Food and Nutrition

One of the most critical determinants of human resource quality is nutritional adequacy. Cancer remains a serious public health problem despite significant advancements in technology in the health and other medical industries (205). The National Action Plan for Non-Communicable Disease Prevention, Control, and Health Promotion in Pakistan (NAP-NCD) combines cancer prevention and control with a comprehensive Non-communicable Diseases (NCD) prevention framework that includes cross-cutting risks such as tobacco and food and physical activity (206). By marking cancer days and world cancer day, the PHRC hopes to improve public awareness of six common diseases of body parts (oral, lung, and liver, breast, cervical, and blood/bone marrow; schedule attached). An education pamphlet on the risk factors and prevention of common cancers has been developed in English and Urdu to easily comprehend common cancers in Pakistan. A deficiency of macronutrients and micronutrients, such as iron (207), vitamin A (208), vitamin C (209), and vitamin D (210), causes cancer (207). The major causes of such deficiencies are insufficient bioavailability and insufficient food intake. A balanced diet ensures sufficient nutrients for a healthy life (211). Malnutrition affects millions worldwide due to inadequate food intake and disease (212). Pakistan is attempting to address health-related concerns by implementing various food and nutrition initiatives.

Food and Nutrition Society Gilgit Baltistan (FNSGB)

FNSGB is a platform for giving people awareness about the basic needs of nutrition and healthcare. Public health issues related to food, nutrition, and health-related disorders are the major handling areas of this society (59). It gives policy and future planning for food and nutrition programs and dietary guidelines for the population on the local level (98). Delivering different campaigns having information about the cancer risk factor and their relation to the dietary patterns and food is the primary core field of this society (6, 62, 98).

Strategies to Avoid Cancer

Anti-smoking regulations in public places have only recently gained traction; even then, they are not being adequately enforced (213). To manage this problem, adequate measures such as anti-smoking education must be used. Advertisements have been discovered to play a substantial role in promoting smoking (214, 215). In Pakistan, regulations prohibiting such advertising techniques were enacted. In Pakistan, two principal regulations oversee tobacco control (216). Using the powers conferred by the two pieces of law. The first necessary regulation is the cigarettes (printing of warning) ordinance of 1979 (Ordinance No. LXXIII of 1979) (217). This essentially requires health warnings to be included on cigarette product packaging. Statutory regulatory orders established the regulations for publishing warnings (SROs) 86(KE)/2009 (218). The initial warning wording and graphics are established by SRO 87(E)/2009 (219). The second necessary regulation is the Ban of Smoking in Enclosed Places and Protection of Non-smokers Health Law, approved in 2002 (Ordinance No. LXXIV of 2002) (220). It controls a variety of facets of tobacco control, including public smoking prohibitions, sales to minors, cigarette advertisements, marketing, and finance. The Committee on Tobacco Advertisement Guidelines was formed by SRO 655(I)/2003 in tobacco advertising, marketing, and finance (221). Despite predictions that increasing the price of cigarettes by 10% will result in a 4.8% immediate drop and a long-term reduction of 11.7% in cigarette smoking, business economics are proving to be a pivotal hurdle to tobacco control (97). SRO 2019 will display a 60% pictorial warning label on cigarette boxes.

Conclusion

This review focuses on cancer and its prevalence across the globe, as well as in Pakistan. Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality around the globe. In 2025, an estimated 19.3 million more cancer cases [18.1 million excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and basal carcinoma] and 10 million additional cancer deaths (9.9 million excluding non-melanoma skin cancers and squamous cell carcinoma) will have been reported globally. Several cancers are also becoming more common in Pakistan. Pakistan's population is 220.9 million. According to GLOBACAN 2020, In Pakistan, there have been 178,388 new cancer cases, 117,149 cancer deaths, and 329,547 overall cancers cases found in five years. Cancer may be caused by poor nutrition, and harmful behaviors such as eating more junk food, adulterating infectious substances, gutkha, and paan. Pakistan is nutritionally deficient in vitamin D, vitamin A, zinc, and iron, according to the national nutrition survey report of 2018 (175). These nutritional deficiencies are the contributing causes of cancer. The use of gutkha, paan, fast foods and adulteration of foods are common culprits for cancer. When it comes to cancer therapy, Pakistan lacks proper policies and strategies. Different governmental and non-governmental organizations are working which are nonetheless making a substantial contribution to the health sector by applying nuclear and other cutting edge technology for cancer diagnosis and treatment. The national action plan also works on cancer prevention measures for NAP-NCD and other groups.

This is a difficult aim for Pakistan to achieve, and it will need dedication from all levels of society. Many characteristics connected to cancer burden discussed here assist to highlight features of cancer epidemiology that may be used to drive intervention programs and promote cancer determinants and outcomes research. Current data on cancer burden will be required for the establishment of national NCD action and cancer control plans, and cancer control measures must be prioritized based on local requirements. Annual updates on the cancer burden will be published in response to this demand.

Author Contributions

AAl, MM, NA, SR, and AAh: wrote the original article. RA, HQ, RS, MM, SK, and WK: reviewed and edited the manuscript. LA and NA: supervised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Key Research and Development Program, China under grant [2018SK2065].

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Authors pay special thanks to Central South University, and Food and Nutrition Society Gilgit Baltistan for giving free access to journals.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Brca1

breast cancer gene-1

- Brca2

breast cancer gene-2

- SKMCH&RC

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center

- NHL

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- HL

Hodgkin lymphoma

- TNM

tumor nodes and metastasis

- WCRF

World Cancer Research Fund

- SLT

severe lung tumors

- IDA

International Development Association

- PNNSKR

Pakistan National Nutritional Survey Key Report

- NCR

National Cancer Registry

- NPFPPH

National Program for Family Planning and Primary Health Care

- PAEC

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission

- HRDP

Human Resource Development Program

- CCHRC

Cancer care hospital and research Centre Pakistan

- CCFPT

Children Cancer Foundation Pakistan Trust

- CCH

Children Cancer Hospital, Pakistan

- NCDBP

National Cancer Data Base Pakistan

- PSCO

Pakistan Society of Clinical Oncology

- NHSRC

National Health Services Regulations and Coordination

- PHRC

Pakistan Health Research Council

- HRCP

Human Rights Commission Pakistan

- PCCWS

Pakistan Cancer Care Welfare Society

- PIMS

Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences

- SOS-PK

Surgical Oncology Society of Pakistan

- NAP-NCD

National Action Plan for Non-Communicable Disease Prevention, Control and Health Promotion in Pakistan

- NCD

non-communicable diseases

- SROs

statutory regulatory orders

- NMSC

non-melanoma skin cancer

- GLOBACAN

global cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence

- IARC

International agency for research on cancer

- AICR

American Institute of cancer research

- PG

pyogenic granuloma

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- WRA

women of reproductive age.

References

- 1.Godet I, Gilkes DM. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integr Cancer Sci Ther. (2017) 4:1–7. 10.15761/ICST.1000228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. (2006) 20:197–209. 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kampa M, Castanas E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ. Pollut. (2008) 151:362–7. 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duell EJ. Epidemiology and potential mechanisms of tobacco smoking and heavy alcohol consumption in pancreatic cancer. Mol Carcinog. (2012) 51:40–52. 10.1002/mc.20786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams PD, Piamjariyakul U, Ducey K, Badura J, Boltz KD, Olberding K, et al. Cancer treatment, symptom monitoring, and self-care in adults: pilot study. Cancer Nurs. (2006) 29:347–55. 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali A, Mughal H, Ahmad N, Babar Q, Saeed A, Khalid W, et al. Novel therapeutic drug strategies to tackle immune-oncological challenges faced by cancer patients during COVID-19. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. (2021) 21:1371–83. 10.1080/14737140.2021.1991317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WebMD Cancer Center,. Understanding Cancer – the Basics. (2020). Available online at: https://www.webmd.com/cancer/guide/understanding-cancer-basics (accessed March 12, 2022).

- 8.Elliott P, Shaddick G, Douglass M, de Hoogh K, Briggs DJ, Toledano MB. Adult cancers near high-voltage overhead power lines. Epidemiology. (2013) 24:184–90. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31827e95b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center SKMCHaR,. Cancer Statistics . (2020). Available online at: https://shaukatkhanum.org.pk/health-care-professionals-researchers/cancer-statistics/ (accessed March 16, 2022).

- 10.Turcotte LM, Neglia JP, Reulen RC, Ronckers CM, Van Leeuwen FE, Morton LM, et al. Risk, risk factors, and surveillance of subsequent malignant neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:2145. 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.7764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anis R, Gaballah K. Oral cancer in the UAE: a multicenter, retrospective study. Libyan J Med. (2013) 8:21782. 10.3402/ljm.v8i0.21782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Angelis R, Francisci S, Baili P, Marchesi F, Roazzi P, Belot A, et al. The EUROCARE-4 database on cancer survival in Europe: data standardisation, quality control and methods of statistical analysis. Eur J Cancer. (2009) 45:909–30. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg J, Waxman IM, Kelly KM, Morris E, Cairo MS. Adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma: state of the science. Br J Haematol. (2009) 144:24–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends-an update. Cancer Epidemiol Prevent Biomark. (2016) 25:16–27. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbeiro S, Atalaia-Martins C, Marcos P, Gonçalves C, Cotrim I, Vasconcelos H, et al. case series of anal carcinoma misdiagnosed as idiopathic chronic anal fissure. GE-Portug J Gastroenterol. (2017) 24:227–31. 10.1159/000452869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Cancer Society,. Cancer Staging . (2021). Available online at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/staging.html (accessed March 17, 2022).

- 17.Feitelson MA, Arzumanyan A, Kulathinal RJ, Blain SW, Holcombe RF, Mahajna J, et al. Sustained proliferation in cancer: mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Semin Cancer Biol. (2015) 35(Suppl.):S25–54. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labi V, Erlacher M. How cell death shapes cancer. Cell Death Dis. (2015) 6:e1675.e. 10.1038/cddis.2015.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egelund R, Petersen H. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2000) 57:25–40. 10.1007/s000180050497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marx RE, Ehler WJ, Tayapongsak P, Pierce LW. Relationship of oxygen dose to angiogenesis induction in irradiated tissue. Am J Surg. (1990) 160:519–24. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81019-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentry M. World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF). Impact. (2017) 2017:32–3. 10.21820/23987073.2017.4.32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Cancer Research Fund International. Research Findings. (2021). Available online at: https://www.wcrf.org/research-we-fund/research-findings/ (accessed March 22, 2022).

- 23.Hartwell LH, Unger MW. Unequal division in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its implications for the control of cell division. J Cell Biol. (1977) 75:422–35. 10.1083/jcb.75.2.422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumner AT. Chromosomes: Organization and Function. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons; (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. (2004) 432:316–23. 10.1038/nature03097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valko M, Rhodes C, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact. (2006) 160:1–40. 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeb LA, Harris CC. Advances in chemical carcinogenesis: a historical review and prospective. Cancer Res. (2008) 68:6863–72. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int J Cancer. (2021) 149:778–89. 10.1002/ijc.33588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei S, Zheng R, Zhang S, Wang S, Chen R, Sun K, et al. Global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality: a population-based cancer registry data analysis from 2000 to 2020. Cancer Commun. (2021) 41:1183–94. 10.1002/cac2.12207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussain I, Majeed A, Rasool MF, Hussain M, Imran I, Ullah M, et al. Knowledge, attitude, preventive practices and perceived barriers to screening about colorectal cancer among university students of newly merged district, Kpk, Pakistan-A cross-sectional study. J Oncol Pharm Pract. (2021) 27:359–67. 10.1177/1078155220922598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rashid A, Aqeel M, Malik B, Salim S. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in breast cancer patients; a cross-sectional study of breast cancer patients experience in Pakistan. Nature. (2021) 1:1–7. 10.47391/NNJP.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohail S, Alam SN. Breast cancer in Pakistan-awareness and early detection (2007). Available online at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1449&context=pakistan_fhs_mc_radiol [PubMed]

- 34.Sarwar MR, Saqib A. Cancer prevalence, incidence and mortality rates in Pakistan in 2012. Cogent Med. (2017) 4:1288773. 10.1080/2331205X.2017.1288773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anwar N, Pervez S, Chundriger Q, Awan S, Moatter T, Ali TS. Oral cancer: Clinicopathological features and associated risk factors in a high risk population presenting to a major tertiary care center in Pakistan. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0236359. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niaz K, Maqbool F, Khan F, Bahadar H, Hassan FI, Abdollahi M. Smokeless tobacco (paan and gutkha) consumption, prevalence, and contribution to oral cancer. Epidemiol Health. (2017) 39:e2017009. 10.4178/epih.e2017009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddiqi K, Shah S, Abbas SM, Vidyasagaran A, Jawad M, Dogar O, et al. Global burden of disease due to smokeless tobacco consumption in adults: analysis of data from 113 countries. BMC Med. (2015) 13:194. 10.1186/s12916-015-0424-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aktas A, Walsh D, Galang M, O'Donoghue N, Rybicki L, Hullihen B, et al. Underrecognition of malnutrition in advanced cancer: the role of the dietitian and clinical practice variations. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. (2017) 34:547–55. 10.1177/1049909116639969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bossi P, Delrio P, Mascheroni A, Zanetti M. The spectrum of malnutrition/cachexia/sarcopenia in oncology according to different cancer types and settings: a narrative review. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1980. 10.3390/nu13061980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravasco P. Nutrition in cancer patients. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:1211. 10.3390/jcm8081211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Planas M, Álvarez-Hernández J, León-Sanz M, Celaya-Pérez S, Araujo K, García de. Lorenzo A. Prevalence of hospital malnutrition in cancer patients: a sub-analysis of the PREDyCES® study. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:429–35. 10.1007/s00520-015-2813-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capra S, Ferguson M, Ried K. Cancer: impact of nutrition intervention outcome-nutrition issues for patients. Nutrition. (2001) 17:769–72. 10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00632-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bourke CD, Berkley JA, Prendergast AJ. Immune dysfunction as a cause and consequence of malnutrition. Trends Immunol. (2016) 37:386–98. 10.1016/j.it.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC. Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2011) 8:514–27. 10.3390/ijerph8020514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dasarathy S, Merli M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J Hepatol. (2016) 65:1232–44. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freijer K, Tan SS, Koopmanschap MA, Meijers JM, Halfens RJ, Nuijten MJ. The economic costs of disease related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. (2013) 32:136–41. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasheed S, Woods RT. Malnutrition and quality of life in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. (2013) 12:561–6. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lummaa V, Clutton-Brock T. Early development, survival and reproduction in humans. Trends Ecol Evol. (2002) 17:141–7. 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02414-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiferaw B, Smale M, Braun H-J, Duveiller E, Reynolds M, Muricho G. Crops that feed the world 10. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by wheat in global food security. Food Secur. (2013) 5:291–317. 10.1007/s12571-013-0263-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: a focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr Res. (2012) 56:18891. 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ali A, Shaukat H, Ahmed M, Bostani A, Hussain S. Relation of electrical stimulation to meat standard. Vet Sci. (2021) 7:42–51. 10.17582/journal.vsrr/2021.7.1.42.51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mellin-Olsen T, Wandel M. Changes in food habits among Pakistani immigrant women in Oslo, Norway. Ethn Health. (2005) 10:311–39. 10.1080/13557850500145238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) . Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: WCRF/AICR; (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry. (2001) 56:5–51. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00316-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clements Jr RS, Darnell B. Myo-inositol content of common foods: development of a high-myo-inositol diet. Am J Clin Nutr. (1980) 33:1954–67. 10.1093/ajcn/33.9.1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hecht SS. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by isothiocyanates. Drug Metab Rev. (2000) 32:395–411. 10.1081/DMR-100102342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hecht SS, Kenney PM, Wang M, Upadhyaya P. Dose-response study of myo-inositol as an inhibitor of lung tumorigenesis induced in A/J mice by benzo [a] pyrene and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Cancer Lett. (2001) 167:1–6. 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00454-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maruthanila V, Poornima J, Mirunalini S. Attenuation of carcinogenesis and the mechanism underlying by the influence of indole-3-carbinol and its metabolite 3, 3′-diindolylmethane: a therapeutic marvel. Adv Pharmacol Sci. (2014) 2014:832161. 10.1155/2014/832161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khalid W, Ali A, Arshad MS, Afzal F, Akram R, Siddeeg A, et al. Nutrients and bioactive compounds of Sorghum bicolor L. used to prepare functional foods: a review on the efficacy against different chronic disorders. Int J Food Proper. (2022) 25:1045–62. 10.1080/10942912.2022.2071293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rokayya S, Li C-J, Zhao Y, Li Y, Sun C-H. Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var capitata) phytochemicals with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential Asian Pacific. J Cancer Prevent. (2013) 14:6657–62. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.11.6657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Craig WJ. Nutrition concerns and health effects of vegetarian diets. Nutr Clin Pract. (2010) 25:613–20. 10.1177/0884533610385707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Babar Q, Ali A, Saeed A, Tahir MF. Novel treatment strategy against COVID-19 through anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunostimulatory properties of the b vitamin complex. In: B-Complex Vitamins: Sources, Intakes and Novel Applications. Intechopen: (2021). 10.5772/intechopen.100251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farag MA, Motaal AAA. Sulforaphane composition, cytotoxic and antioxidant activity of crucifer vegetables. J Adv Res. (2010) 1:65–70. 10.1016/j.jare.2010.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abbaoui B, Lucas CR, Riedl KM, Clinton SK, Mortazavi A. Cruciferous vegetables, isothiocyanates, and bladder cancer prevention. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2018) 62:1800079. 10.1002/mnfr.201800079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liang H, Wei Y, Li R, Cheng L, Yuan Q, Zheng F. Intensifying sulforaphane formation in broccoli sprouts by using other cruciferous sprouts additions. Food Sci Biotechnol. (2018) 27:957–62. 10.1007/s10068-018-0347-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gautam S, Saxena S, Kumar S. Fruits and vegetables as dietary sources of antimutagens. J Food Chem Nanotechnol. (2016) 2:97–114. 10.17756/jfcn.2016-01828110066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banerjee S, Kong D, Wang Z, Bao B, Hillman GG, Sarkar FH. Attenuation of multi-targeted proliferation-linked signaling by 3, 3′-diindolylmethane (DIM): from bench to clinic. Mutat Res Rev. (2011) 728:47–66. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arora S, Vig AP. Inhibition of DNA oxidative damage and antimutagenic activity by dichloromethane extract of Brassica rapa var. rapa L seeds. Indus Crops Prod. (2015) 74:585–91. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.05.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ren W, Qiao Z, Wang H, Zhu L, Zhang L. Flavonoids: promising anticancer agents. Med Res Rev. (2003) 23:519–34. 10.1002/med.10033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Antioxidants in fruits and vegetables-the millennium's health. Int J Food Sci Technol. (2001) 36:703–25. 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2001.00513.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chaudhary P, Sharma A, Singh B, Nagpal AK. Bioactivities of phytochemicals present in tomato. J Food Sci Technol. (2018) 55:2833–49. 10.1007/s13197-018-3221-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.D'Archivio M, Santangelo C, Scazzocchio B, Varì R, Filesi C, Masella R, et al. Modulatory effects of polyphenols on apoptosis induction: relevance for cancer prevention. Int J Mol Sci. (2008) 9:213–28. 10.3390/ijms9030213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Das Gupta S, Suh N. Tocopherols in cancer: an update. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2016) 60:1354–63. 10.1002/mnfr.201500847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eggersdorfer M, Wyss A. Carotenoids in human nutrition and health. Arch Biochem Biophys. (2018) 652:18–26. 10.1016/j.abb.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmidt KM, Haddad EN, Sugino KY, Vevang KR, Peterson LA, Koratkar R, et al. Dietary and plasma carotenoids are positively associated with alpha diversity in the fecal microbiota of pregnant women. J Food Sci. (2021) 86:602–13. 10.1111/1750-3841.15586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brewczyński A, Jabłońska B, Kentnowski M, Mrowiec S, Składowski K, Rutkowski T. The association between carotenoids and head and neck cancer risk. Nutrients. (2022) 14:88. 10.3390/nu14010088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van den Brandt PA. Red meat, processed meat, and other dietary protein sources and risk of overall and cause-specific mortality in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol. (2019) 34:351–69. 10.1007/s10654-019-00483-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saqib SE, Kuwornu JK, Panezia S, Ali U. Factors determining subsistence farmers' access to agricultural credit in flood-prone areas of Pakistan. Kasetsart J Soc Sci. (2018) 39:262–8. 10.1016/j.kjss.2017.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Staal SJ, Nin Pratt A, Jabbar M. Dairy development for the resource poor. In: Part 3: Pakistan and India Dairy Development Case Studies FAO/PPLPI Working Paper. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vorley B, Lundy M, MacGregor J. Business Models That Are Inclusive of Small Farmers. Agro-industries for Development. Wallingford: CABI for FAO and UNIDO; (2009). p. 186–222. 10.1079/9781845935764.0186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tahir MN, Riaz R, Bilal M, Nouman HM. Current standing and future challenges of dairying in Pakistan: a status update. In: Javed K. editor. Milk Production, Processing and Marketing. London: (2019). p. 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Awan A, Naseer M, Iqbal A, Ali M, Iqbal R, Iqbal F. A study on chemical composition and detection of chemical adulteration in tetra pack milk samples commercially available in Multan. Pakistan J Pharm Sci. (2014) 27:183–6. Available online at: http://www.pjps.pk/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/27/1/Paper-27.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jalil H, Rehman HU, Sial MH, Hussain SS. Analysis of milk production system in Peri-urban areas of Lahore (Pakistan): a case study. Pakistan Econ Soc Rev. (2009) 47:229–42. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25825354 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Motta TC, Hoff R, Barreto F, Andrade R, Lorenzini D, Meneghini L, et al. Detection and confirmation of milk adulteration with cheese whey using proteomic-like sample preparation and liquid chromatography-electrospray-tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Talanta. (2014) 120:498–505. 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.11.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Javed K, Afzal M, Sattar A, Mirza R. Environmental factors affecting milk yield in Friesian cows in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak Vet J. (2004) 24:58–61. Available online at: http://www.pvj.com.pk/pdf-files/24_2/58-61.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 86.Handford CE, Campbell K, Elliott CT. Impacts of milk fraud on food safety and nutrition with special emphasis on developing countries. Comprehens Rev Food Sci Food Saf. (2016) 15:130–42. 10.1111/1541-4337.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.KC B, Schultz B, McIndoe I, Rutter H, Dark A, Prasad K, et al. Impacts of dairy farming systems on water quantity and quality in Brazil, Ethiopia, Nepal, New Zealand and the USA. Irrigat Drain. (2020) 69:944–55. 10.1002/ird.2486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Singh P, Gandhi N. Milk preservatives and adulterants: processing, regulatory and safety issues. Food Rev Int. (2015) 31:236–61. 10.1080/87559129.2014.994818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boada LD, Henríquez-Hernández LA, Luzardo O. The impact of red and processed meat consumption on cancer and other health outcomes: Epidemiological evidences. Food Chem Toxicol. (2016) 92:236–44. 10.1016/j.fct.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Peleteiro B, Lopes C, Figueiredo C, Lunet N. Salt intake and gastric cancer risk according to Helicobacter pylori infection, smoking, tumour site and histological type. Br J Cancer. (2011) 104:198–207. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Solans M, Castelló A, Benavente Y, Marcos-Gragera R, Amiano P, Gracia-Lavedan E, et al. Adherence to the Western, Prudent, and Mediterranean dietary patterns and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the MCC-Spain study. Haematologica. (2018) 103:1881. 10.3324/haematol.2018.192526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu AH, Pike MC, Stram DO. Meta-analysis: dietary fat intake, serum estrogen levels, and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1999) 91:529–34. 10.1093/jnci/91.6.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Black HS, Chan JT. Suppression of ultraviolet light-induced tumor formation by dietary antioxidants. J Invest Dermatol. (1975) 65:412–4. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12607661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carbamate E,. Volume 96: Alcohol Consumption Ethyl Carbamate. World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer (2010). p. 632–714. Available online at: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Alcohol-Consumption-And-Ethyl-Carbamate-2010

- 95.Mukherjee P, Seyfried T. Metabolic targeting of brain cancer. Nutr Metab (Lond). (2005) 2:30. 10.1186/1743-7075-2-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Caldwell SH, Crespo DM, Kang HS, Al-Osaimi AM. Obesity and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. (2004) 127:S97–103. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ahmad SA, Ahmed M, Qadir MA, Shafiq MI, Batool N, Nosheen N, et al. Quantitation and risk assessment of chemical adulterants in milk using UHPLC coupled to photodiode array and differential refractive index detectors. Food Anal Methods. (2016) 9:3367–76. 10.1007/s12161-016-0534-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ali A, Ain Q, Saeed A, Khalid W, Ahmed M, Bostani A. Bio-molecular characteristics of whey proteins with relation to inflammation. In: New Advances in the Dairy Industry. Intechopen: (2021). 10.5772/intechopen.99220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patel PK, Patel SK, Dixit S, Rathore R. Gastritis and peptic ulcer diseases in dogs: A review. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. (2018) 7:2475–501. 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.703.288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xiao A, Yang S, Iqbal Q. Factors affecting purchase intentions in generation Y: an empirical evidence from fast food industry in Malaysia. Administr Sci. (2018) 9:4. 10.3390/admsci9010004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Musaiger AO. Consumption, health attitudes and perception toward fast food among Arab consumers in Kuwait: gender differences. Glob J Health Sci. (2014) 6:136. 10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tannock S. Youth at Work: The Unionized Fast-Food and Grocery Workplace. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Evaluating Fast Food Nutrition and Marketing to Youth. New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 104.Baig AK, Saeed M. Review of trends in fast food consumption. Eur J Econ Finan Administr Sci. (2012) 48:77–85. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Munazza-Saeed-3/publication/266627067_Review_of_Trends_in_Fast_Food_Consumption/links/543652160cf2dc341db2fa61/Review-of-Trends-in-Fast-Food-Consumption.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 105.Blisard WN, Jolliffe D. Let's Eat Out: Americans Weigh Taste, Convenience and Nutrition. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cohen DA, Babey SH. Contextual influences on eating behaviours: heuristic processing and dietary choices. Obes Rev. (2012) 13:766–79. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01001.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mead E, Gittelsohn J, Kratzmann M, Roache C, Sharma S. Impact of the changing food environment on dietary practices of an Inuit population in Arctic Canada. J Hum Nutr Dietet. (2010) 23:18–26. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.James D. Factors influencing food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes among African Americans: application of a culturally sensitive model. Ethn Health. (2004) 9:349–67. 10.1080/1355785042000285375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harrington RJ, Ottenbacher MC, Kendall K. Fine-dining restaurant selection: Direct and moderating effects of customer attributes. J Foodservice Bus Res. (2011) 14:272–89. 10.1080/15378020.2011.594388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Anand R. A. study of determinants impacting consumers food choice with reference to the fast food consumption in India. Soc Bus Rev. (2011) 6:176–187. 10.1108/17465681111143993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. (2012) 379:1641–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fuhrman J. The hidden dangers of fast and processed food. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2018) 12:375–81. 10.1177/1559827618766483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yahya F, Zafar R, Shafiq S. Trend of fast food consumption and its effect on Pakistani society. Food Sci Qual Manage. (2013) 11:1–7. Available online at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234683616.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yan Y. Of Hamburger and Social Space: Consuming. Beijing: McDonald's; (2000). [Google Scholar]