Abstract

Protein condensation into liquid-like structures is critical for cellular compartmentalization, RNA processing, and stress response. Research on protein condensation has primarily focused on membraneless organelles in the absence of lipids. However, the cellular cytoplasm is full of lipid interfaces, yet comparatively little is known about how lipids affect protein condensation. Here, we show that nonspecific interactions between lipids and the disordered fused in sarcoma low-complexity (FUS LC) domain strongly affect protein condensation. In the presence of anionic lipids, FUS LC formed lipid-protein clusters at concentrations more than 30-fold lower than required for pure FUS LC. Lipid-triggered FUS LC clusters showed less dynamic protein organization than canonical, lipid-free FUS LC condensates. Lastly, we found that phosphatidylserine membranes promoted FUS LC condensates having β sheet structures, while phosphatidylglycerol membranes initiated unstructured condensates. Our results show that lipids strongly influence FUS LC condensation, suggesting that protein-lipid interactions modulate condensate formation in cells.

Disordered protein condensation is highly sensitive to nonspecific protein-lipid interactions.

INTRODUCTION

Lipid membranes are responsible for maintaining physical barriers around and establishing subcellular compartments within mammalian cells. Molecular heterogeneities associated with the structure of cellular membranes are thought to be responsible for controlling many biological processes such as membrane trafficking, cell signaling, sorting of membrane proteins, and cellular transport (1–4). Recent findings that macromolecules can spontaneously demix into membraneless biomolecular condensates (BCs) have challenged the belief that cellular compartmentalization requires membrane barriers. BCs are liquid-like assemblies of proteins and nucleic acids held together by multivalent interactions. P-granules, stress granules, Cajal bodies, and nucleoli are just a few examples for which demixing and self-assembly of proteins and other macromolecules are believed to play an important role (5–7). As a consequence of being liquid-like and requiring multivalent interactions, BCs often contain proteins with substantial disorder, known as intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). Over the past decade, numerous BC-forming IDPs have been identified via in vitro experiments, and triggers that drive condensation of IDPs, such as changes in local concentration, salt concentration, pH, and temperature, have been intensely explored (8–11). While phase separation of macromolecules into lipid-free BCs in vitro has been a strong focus, the cytoplasm of mammalian cells contains countless membrane-wrapped organelles. Therefore, self-assembling macromolecules and membranes are undoubtedly near one another in cells, yet only a handful of studies have investigated how membranes affect BC formation.

Lipid membranes have been shown to drive bundling/clustering of actin filaments, catalyze actin polymerization by locally increasing protein concentration at the membrane, and promote condensation of disordered proteins (12–14). Similarly, recent work by Stone et al. (15) showed that lipid domains sequestered B cell receptors that ultimately led to additional sorting of interacting proteins. In all these cases, a specific protein-lipid interaction was required to produce the observed phenomenon, or the receptor was anchored into the membrane. While specific anchoring of proteins to membranes can locally concentrate proteins and stimulate protein-protein interactions at concentrations far below what is required in lipid-free solutions, the role of nonspecific protein-lipid interactions, particularly with respect to the formation of liquid-like BCs at membranes, is unclear. Previous work has highlighted the catalytic influence of nonspecific protein-lipid interactions on the formation and structure of solid protein aggregates (16, 17). For example, membranes have been shown to modify the protein structure of α-synuclein (18), Aβ42 (19), or Tau (20–22), leading to β sheet–enriched amyloid fibrils. However, the impact of nonspecific interactions on liquid BC formation is unknown. In this work, we investigate how nonspecific membrane-protein interactions affect BC formation.

Considering the diversity of lipids in the cytoplasm and the many IDPs that have been identified to form liquid-like BCs, several questions can be asked regarding protein phase separation/clustering resulting from protein-lipid interactions. Here, we present results demonstrating how the nature of the head group, even among lipids with identical charge, can trigger distinct phase separation and protein structuring at lipid interfaces, using the fused in sarcoma (FUS) low-complexity (LC) domain as a model IDP. We combined fluorescence and broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (BCARS) imaging with interface-specific vibrational sum-frequency generation (SFG) spectroscopy to probe the interaction of FUS LC–lipid in situ. Our experiments show that phospholipid membranes trigger FUS LC phase separation via nonspecific interactions at ~30-fold lower concentrations compared to bulk, with different lipid head groups causing unique protein structuring at lipid interfaces.

RESULTS

Anionic lipids catalyze condensation of FUS LC

FUS is an RNA binding protein that is part of stress granules formed inside the cytosol via liquid-liquid phase separation (7, 23, 24). FUS LC (residues 1 to 163) is a Q/S/Y/G-rich intrinsically disordered domain that is known to exhibit numerous self-interactions and has been well characterized in terms of its phase-separating behavior in vitro, in bulk solutions (23, 25). Recently, Yuan et al. (14) showed that his-tagged FUS LC could phase-separate at lipid membranes and deform unilamellar vesicles when bound by specific Ni–NTA (nitrilotriacetic acid)–His interactions. As FUS LC does not specifically interact with membranes in cells, we asked whether nonspecific protein-lipid interactions could influence FUS LC phase separation.

As a starting point, we probed the influence of small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs), having a size similar to endocytic and exocytic vesicles, on FUS LC phase separation. We chose biologically relevant phospholipids present in the plasma membrane and on intracellular organelle membranes: phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidylglycerol (PG), which are zwitterionic, anionic, and anionic, respectively. Because cellular membranes facing the cytoplasm contain mostly (poly)unsaturated lipids, we used 18:1 (dioleoyl) unsaturated lipids for the present studies (26). The hydrodynamic diameter of the pristine SUVs was characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS), and these samples were used without any further processing. We found that the concentration of SUVs from PC, PG, and PS was ~1015 particles/ml (fig. S1 and table S1). At 10 μM FUS LC, far below the bulk concentration of FUS LC (~150 μM) (10) required for condensate formation in room temperature phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), we observed that negatively charged SUVs (from PG and PS lipids) caused FUS LC condensation (Fig. 1A). In addition to light microscopy, we used DLS to characterize the SUVs in PBS before and after incubation with 10 μM FUS LC. DLS results showed a new size distribution in DOPG [1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt)] and DOPS [1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (sodium salt)] SUVs after incubation with FUS LC but not for DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine). Turbidity measurements at 600-nm excitation showed that DOPS (0.126 ± 0.001) and DOPG (0.105 ± 0.002) had reduced transmittance upon addition of FUS LC compared to SUVs or FUS LC alone. The microscopy results and bulk assays confirm that DOPG and DOPS membranes catalyze the formation of micrometer-scale, phase-separated clusters at a much lower concentration than without lipids via nonspecific interactions. As PC lipids did not appear to catalyze cluster formation, we restricted our study to FUS interacting with PG and PS lipids in what follows. To further explore the effect of nonspecific interactions between PG and PS SUVs and FUS LC, we varied the protein bulk concentration and observed that protein-lipid cluster formation occurred at 5 and 3 μM FUS LC concentration for DOPS SUVs and DOPG SUVs, respectively (fig. S2). We then varied the number of SUVs at a fixed FUS LC concentration of 10 μM and investigated cluster formation. Our results show that cluster formation can be triggered at ~1000-fold dilution of SUV concentration for PG and PS SUVs (fig. S3). As DOPG and DOPS are nominally negatively charged, it appears that FUS LC has a sufficiently strong interaction with negatively charged lipids to drive cluster formation. We note that FUS LC has a very low negative charge density (with two negative charges and zero positive charges) at pH 7.4, so the interaction with negatively charged PS and PG lipids is likely not electrostatic.

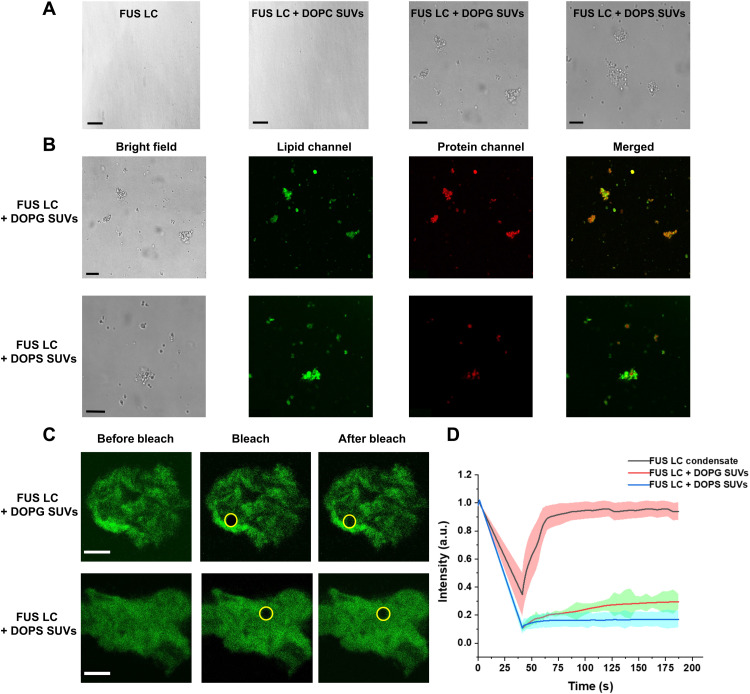

Fig. 1. Negatively charged lipid membranes trigger FUS LC condensation at 10 μM FUS LC.

(A) Bright-field images of FUS LC (10 μM) in the presence and absence of different SUVs (~1015 SUVs/ml) in PBS (pH 7.4) (pristine FUS LC, FUS LC + DOPC SUVs, FUS LC + DOPG SUVs, and FUS LC + DOPS SUVs, from left to right). Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Confocal microscopy images of SUVs {doped with 0.1 mol % of 18:1 Liss Rhod PE [1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (ammonium salt)]} incubated with 10 μM FUS LC (doped with 0.1 mol % of Cy5-labeled FUS LC) in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). From left to right: Bright-field image, lipid, and protein fluorescence channels and merged fluorescence images. Top: FUS LC and DOPG SUVs. Bottom: FUS LC and DOPS SUVs. Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Representative images from FRAP experiments of 0.1 mol % Cy3-labeled FUS LC (10 μM) incubated with DOPG (top) and DOPS (bottom) SUVs. The yellow circle marks the bleached area. Scale bars, 5 μm. (D) Normalized fluorescence intensity of FUS LC from FRAP experiments. Lines show the average traces from N = 5 samples for FUS LC condensates (black) and FUS LC + DOPG SUV (red) and FUS LC + DOPS SUV (blue) clusters. The shaded regions show the SDs for each type of sample. a.u., arbitrary units.

Fluorescence microscopy of labeled lipids and FUS LC showed that DOPS and DOPG SUVs caused micrometer-sized phase-separated clusters containing FUS LC and lipids (Fig. 1B). A similar type of membrane-triggered aggregation of α-synuclein has been reported by Dobson and co-workers (18, 27). We note that fluorescence colocalization of FUS LC and lipids and turbidity values were different for PG versus PS SUVs in the presence of FUS LC, suggesting that the micrometer-scale, phase-separated clusters from the two lipid head groups are somehow unique. To probe the protein dynamics inside the protein-lipid colocalized clusters, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments (Fig. 1C) using 0.1 mole percent (mol %) of N-terminal Cy3-labeled FUS LC in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). From these experiments, the estimated half-life (t1/2) value for FUS LC in PG SUVs revealed a relatively slower (t1/2 = 30.5 ± 1 s) fluorescence recovery compared to FUS LC recovery in PS SUVs (t1/2 = 19.5 ± 2 s) (Fig. 1D). In addition, we found that PS–FUS LC clusters show less total fluorescence recovery. The decreased fluorescence intensity recovery and increased recovery speed of FUS LC in PS–FUS LC clusters show that the material properties of PG and PS protein-lipid clusters are distinct. The results indicate that fewer FUS LC molecules are free to move in PS clusters, but those that can move do so with increased mobility when compared to PG clusters. The FUS LC–lipid clusters that we study here show much retarded and only partial recovery compared to pure FUS LC condensates (near-full recovery, with t1/2 = 4.5 ± 2.5 s; Fig. 1D); hence, the FUS LC–lipid clusters appear to be more solid-like compared to pure FUS LC condensates. This is distinct from the phase-separated FUS LC protein networks on giant (~30-μm-diameter) vesicles initiated by specific Ni-NTA–His interactions in the work of Yuan et al. (14), which the authors described as liquid-like. The interactions between FUS LC and SUVs are nonspecific in our work, and we use ~20-nm SUVs, both of which likely contribute to the different recovery times of the clusters that we report here (14).

Protein and lipid composition in PS and PG protein-lipid clusters is similar

With turbidity assays and FRAP experiments showing that FUS LC phase separation triggered by DOPS and DOPG lipid membranes exhibits unique properties, we wondered whether the molecular composition of FUS LC–lipid clusters triggered by DOPS and DOPG SUVs was similar. To that end, we used molecular microscopy via nonlinear Raman scattering to quantify the composition of protein-lipid clusters. We have previously used quantitative BCARS microscopy for measurements of protein structure and composition in pure FUS LC BCs, peptide-polymer phase-separated systems (28), and lipid droplets (23, 29). BCARS can also shed light on the subtle differences between DOPS and DOPG SUVs from, e.g., lipid packing (29), that potentially cause the differences in turbidity or FRAP seen for FUS LC–lipid clustering.

We first used BCARS to acquire the hyperspectral images of pristine, as-prepared concentrated DOPS and DOPG SUVs (Fig. 2, A and B). The Raman bands at ~2850, 2888, 2930, 2950, and 3010 cm−1 were assigned to the symmetric CH2 stretching, antisymmetric CH2 stretching (and CH2 Fermi resonance), CH3 symmetric, antisymmetric CH3 stretch, and ═C─H stretch, respectively, based on previous coherent Raman scattering work (30–32). Because the relative abundance of CH2 groups in lipid molecules is higher than that of CH3 groups, BCARS intensities at 2850 and 2888 cm−1 (due to CH2 vibrations) were dominant over CH3 group vibrations at 2930 and 2950 cm−1, as expected. The CH vibrational features for the SUVs from both lipids are highly similar. The lipid packing ratio I2888 cm−1/I2850 cm−1 that reports on the packing of the lipid acyl tails was 0.99 ± 0.13 for DOPG and 0.92 ± 0.11 for DOPS pristine SUVs, showing that acyl chains were in liquid form in both types of SUVs, as expected (33–35). DOPG membranes were slightly more tightly packed than DOPS membranes, possibly because of a less bulky head group.

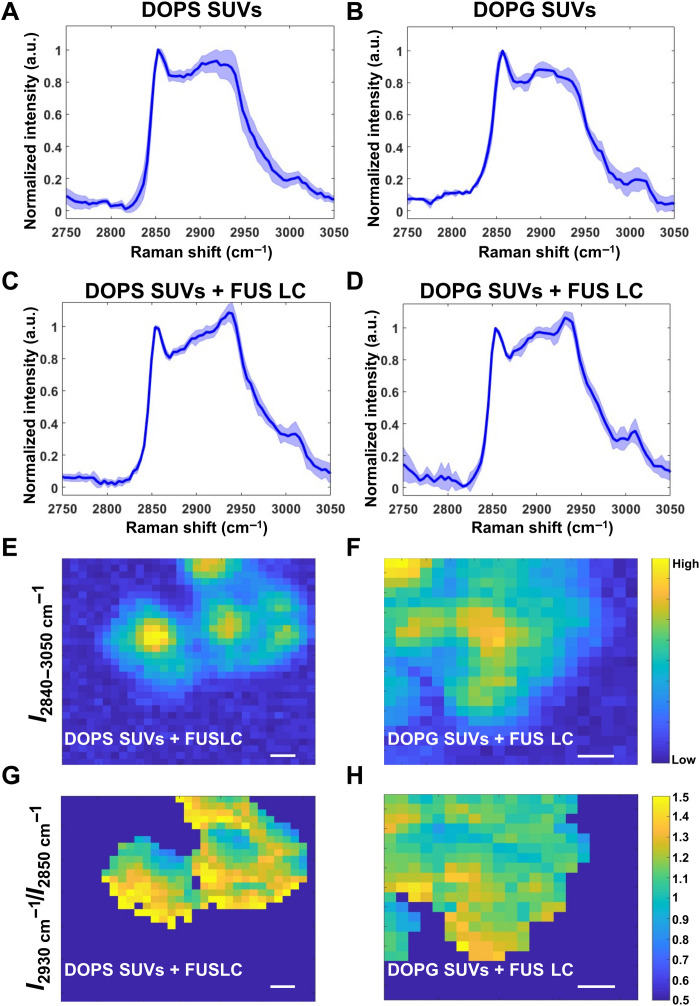

Fig. 2. BCARS hyperspectral imaging of FUS LC–lipid clusters.

(A and B) Resonant BCARS spectra of pristine DOPS SUVs and DOPG SUVs, respectively. (C and D) Resonant BCARS spectra of phase-separated clusters after adding 10 μM FUS LC to DOPS SUVs and DOPG SUVs (~1015 SUVs/ml), respectively. Buffer conditions were PBS (pH 7.4). All spectra were normalized by the intensity at 2850 cm−1. Dark lines and shaded areas in (A) to (D) are the average and SD from n > 3 samples from three independent sample preparations. (E and F) Representative total CH (2840 to 3050 cm−1) region images of FUS LC DOPS and DOPG FUS LC–lipid clusters, respectively, from spectral integration. (G and H) Protein:lipid ratio images, with ratios calculated by the integrated intensity of the CH3 symmetric peak (2930 cm−1) divided by the intensity of the CH2 symmetric peak (2850 cm−1) from the FUS LC–lipid clusters imaged in (E) and (F), respectively. Note that the images are thresholded such that regions with very little 2850 cm−1 are set to 0. Scale bars, 1 μm.

Upon adding FUS LC to the PS and PG SUVs, the spectral shapes of the protein-lipid clusters for both types of SUVs changed substantially. This change reflects the presence and interaction between FUS LC and lipids in the SUVs. DOPS and DOPG SUV–FUS LC clusters shared several overlapping vibrational bands in CH stretching region, most prominently an increased CH3 symmetric (2930 cm−1) band from the protein CH3 groups (Fig. 2, C and D) (31). Thus, the 2930 cm−1 band provides a mostly protein-specific signal, while the 2850 cm−1 CH2 symmetric band reflects mostly lipids. The BCARS spectrum of the pristine phase-separated FUS LC was measured as a control and showed a strong CH3 and aromatic CH stretch peak with only a shoulder for the CH2 symmetric peak (fig. S4).

The protein signal at 2930 cm−1 increased relative to the lipid signal (at 2850 cm−1) in PG– and PS–FUS LC clusters (Fig. 2, C and D). Protein-lipid clusters were imaged on the basis of the integrated CH band (from 2840 to 3050 cm−1) as shown in Fig. 2 (E and F). Ratio images of the lipid and protein bands (I2930 cm−1/I2850 cm−1) allowed us to compare the relative abundance of proteins and lipids in the PG– and PS–FUS LC clusters (Fig. 2, G and H). These images show that the normalized protein signal (at 2930 cm−1) in the FUS LC–PS and FUS LC–PG SUV clusters were similar and nonuniform (varying by up to threefold), with FUC LC–PS clusters having slightly more protein compared to lipids compared to PG clusters on average.

The cytosol contains different membranes with distinct morphologies, and these membrane interfaces play crucial roles in many subcellular processes. Hence, we were curious to investigate the impact of larger model membrane systems, in addition to SUVs, on FUS LC phase separation. We prepared pristine DOPS and DOPG giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) via electroformation and incubated them with FUS LC (5 μM) in PBS, taking care to match the osmolarity across the GUVs with glucose during formation. Even at this low concentration, we observed a protein signal at the surface of both DOPS and DOPG GUVs (fig. S5). With the protein signal being localized primarily at the periphery of the GUVs, this indicates that the nonspecific interaction between the protein and lipid again drives protein interaction. However, with no obvious morphological differences for FUS LC–lipid clusters for SUVs or GUVs from fluorescence or BCARS microscopy, we next used interfacially specific vibrational SFG spectroscopy to probe for molecular-scale differences.

Interfacial protein structuring at lipid monolayers

FRAP, DLS, and turbidity experiments showed that protein-lipid clusters formed by PS and PG SUVs with FUS LC are distinct, and the BCARS data show that the protein:lipid composition is slightly different for PG versus PS lipids. Therefore, we speculated that the nature of the lipids, despite having the same net charge, influenced protein organization at the lipid interface. Indeed, a very recent report by Hannestad et al. (36) highlighted a very similar phenomenon for α-synuclein interacting with DOPS and DOPG SUVs. Therefore, we used interfacially specific SFG spectroscopy, a second-order nonlinear spectroscopy to probe molecular structure precisely at the lipid interface. In contrast to BCARS, SFG provides a readout of molecular vibrations that exhibit noncentrosymmetric organization at interfaces (37).

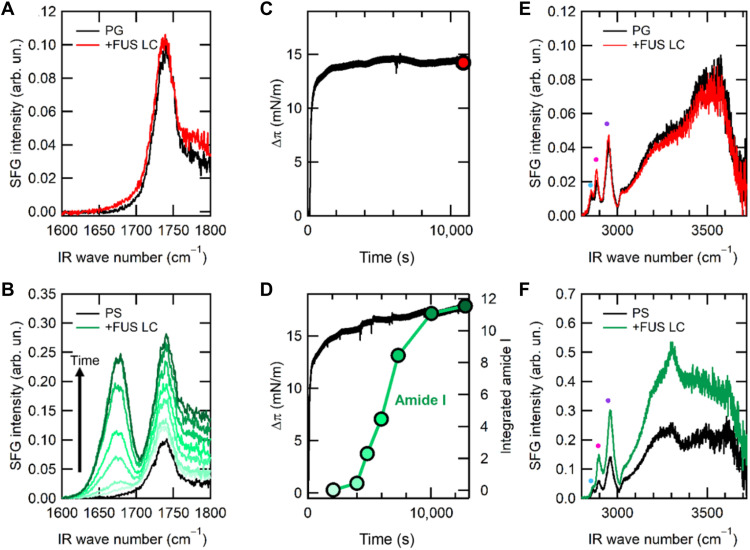

To probe the interactions between the FUS LC and PG and PS lipids, we formed lipid monolayers at an air-buffer interface and simultaneously measured both SFG and surface pressure (SP) signals in the absence and presence of FUS LC (Fig. 3). SFG spectra of pristine DOPG and DOPS monolayers prepared on a PBS subphase with an SP of ~20 mN/m are shown as the black curves in Fig. 3 (A and B, respectively). The SFG signal centered at ~1740 cm−1 was present for both DOPG and DOPS and corresponds to the carbonyl stretching vibration originating from C═O group of the lipids at the lipid-buffer interface. Upon addition of 3 μM FUS LC into the PBS subphase (t = 0 in Fig. 3, C and D, black curves), the SP increased for both DOPG and DOPS monolayers by an initial jump of 13 mN/m, a clear indication that FUS LC adsorbed/inserts to both monolayers to a similar extent. However, in the case of the DOPG, the SP plateaued, while it continued to gradually increase for DOPS. Looking at the SFG signal, we observed no change in the signal for DOPG after the addition of FUS LC. In particular, there was no change in the amide I region after adding FUS LC (red curve, Fig. 3A), even more than 2.5 hours after protein addition. Combining the SFG and SP experimental results, we conclude that FUS LC protein adsorbs to the DOPG monolayer (based on SP results); however, it remains disordered (based on SFG results).

Fig. 3. SFG spectra show FUS LC orders at DOPS membranes.

(A) SFG spectra acquired in the amide I and carbonyl stretching region for a DOPG monolayer, π ~ 20 mN/m, before (black) and after (red, t ~ 12,000 s) FUS LC addition. (B) SFG spectra acquired in the amide I and carbonyl stretching region for a DOPS monolayer, π ~ 20 mN/m, before (black) and after (green, t ~ 12,000 s) FUS LC addition. (C) Time dependence of the SP change Δπ after the addition of FUS LC to the PBS buffer subphase (at t = 0) for the DOPG monolayer. The red circle indicates the time at which the red SFG spectrum in (A) was recorded. (D) Time dependence of Δπ (black) and integrated SFG amide I intensity (green) after the addition of FUS LC to the PBS buffer subphase (at t = 0) for the DOPS monolayer. Amide I intensity was obtained from SFG spectral fitting to data in (B), with the same color coding. (E and F) SFG spectra acquired in the ─CH and ─OH stretching region for a DOPG and DOPS monolayer, respectively, before (black) and after (red and green) FUS LC addition. The colored dots in (E) and (F) indicate the spectral peak assignments: (cyan) symmetric CH2 stretching, (magenta) symmetric CH3 stretching, and (purple) symmetric CH3 stretching (Fermi resonance). IR, infrared.

On the contrary, the SFG response was markedly different for the DOPS monolayer. After FUS LC was added to the subphase, a peak in the amide I region centered at ~1675 cm−1 appeared after ~1 hour and grew substantially over the next ~1.5 hours (green curves, Fig. 3B). The presence of an SFG amide I response indicates a net ordering of FUS LC amide bonds at the DOPS monolayer. On the basis of previous SFG studies, the observed amide I signal frequency suggests that the interfacial FUS LC protein adopts a β sheet conformation at the DOPS monolayer (38–40). Spectral fitting of the SFG amide I region (see fig. S6 and table S2) to isolate the contribution of the amide I signal in the measured SFG spectra allowed quantification of the amide I intensity over time. The increase of this peak over time, similar to the SP, shows that folding and/or ordering of FUS LC at the DOPS monolayer interface is also accompanied by a slower but steady increase in SP (Fig. 3D). Figure 3D shows that the initial FUS LC adsorption process resulting in the large SP increase happens on a short time scale compared to the FUS LC interfacial ordering.

While the amide SFG spectroscopy demonstrates FUS LC ordering at the DOPS lipid layer, another important feature of protein adsorption to the lipids is the hydration of the interface. To address this question, we probed the CH stretch (2800 to 3100 cm−1) and OH stretch (3200 to 3700 cm−1) vibrations using SFG. SFG spectra acquired in CH/OH stretching region for DOPG showed no significant changes in spectral shape and/or intensity of the CH or OH vibrational response after the FUS LC addition, similar to that seen for the amide I mode (Fig. 3E and table S3). As before, DOPS lipid interfaces were again different. The SFG OH stretching signal intensity increased substantially for the DOPS monolayer (Fig. 3F) in the presence of FUS LC. The increased OH signal shows that protein-lipid interaction strongly perturbed the hydration compared to the pristine DOPS-buffer interface. The increased OH signal for FUS LC ordering at the DOPS interface possibly comes from enhanced ordering of OH bonds in water or from OH moieties of FUS LC side chains (present in tyrosine and serine). The spectral feature centered at ~3300 cm−1 (less apparent before and more apparent after FUS LC addition) corresponds to the ─NH stretching (41). After FUS LC addition, a relatively pronounced ─NH signal appeared, likely because of the reorganization of the DOPS lipid head group in the monolayer induced by FUS LC adsorption and/or by ─NH groups in FUS LC itself. Looking at the CH peaks (indicated by cyan, magenta, and purple dots in Fig. 3F) shows that their relative intensity also changed for the DOPS monolayer with a much larger ICH3/ICH2 ratio (fig. S7 and table S4). However, because both lipid and FUS LC molecules contain CH2 and CH3 moieties in their chemical structures, the exact origin of CH signal changes is challenging to assign.

FUS LC β sheet structuring is more prominent on DOPS lipid bilayers

SP measurements clearly showed that FUS LC adsorbed to PG and PS monolayers, and SFG spectroscopy showed protein ordering and β sheet formation at DOPS lipid monolayers. As a follow-up experiment, we investigated whether FUS LC showed a similar association and structuring at planar lipid bilayers. Therefore, we used supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy for direct visualization of the FUS LC binding to PG and PS lipid bilayers. TIRF allows fluorescence detection from the first ~200 nm above the glass surface with minimal background. TIRF images of pristine SLBs from DOPG and DOPS labeled with 18:1 Liss Rhod PE [1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (ammonium salt)] on cleaned glass slides showed uniform fluorescence, as expected (fig. S8). Next, we added 10 μM FUS LC to the SLBs. Because the amide I response in SFG took ~1 hour to appear after FUS LC addition to the PS monolayer (Fig. 3, B and D), we imaged labeled FUS LC and SLBs in TIRF 1 hour after FUS LC addition. Both PG and PS SLBs showed micrometer-sized structures in the lipid channel (Fig. 4, A and G, respectively) that were evenly distributed in the field of view. Looking at labeled FUS LC, we also saw micrometer-sized features on PS and PG SLBs, as expected from SP measurements, showing an increase after FUS LC addition to both monolayers. The micrometer-sized features in the protein channel were less prominent than structures in the lipid channel (Fig. 4, B and H). These features show that FUS LC modifies the morphology of lipids from a homogeneous bilayer to a patchy distribution of spherical domains.

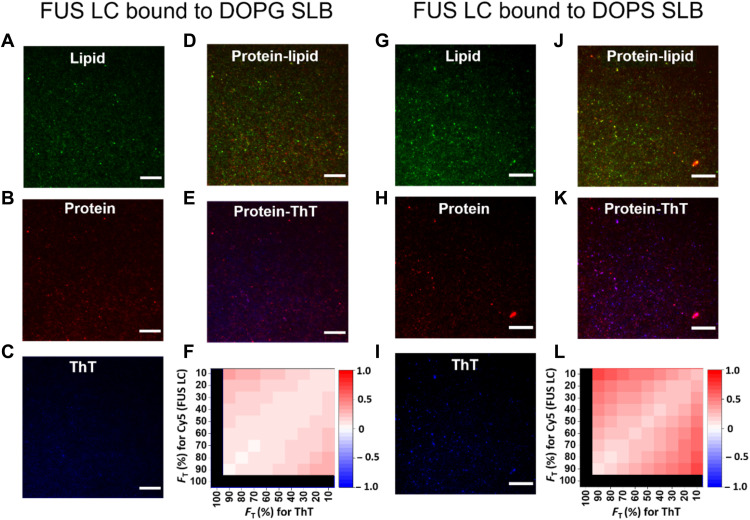

Fig. 4. FUS LC–lipid clusters on DOPS bilayers bind more thioflavin T than clusters on DOPG bilayers.

TIRF microscopy images of SLBs incubated with FUS LC (10 μM) and thioflavin T (ThT) (10 μM). Images of DOPG SLBs (left) and DOPS SLBs (right) of (A and G) lipid, (B and H) protein, (D and J) protein (green)–lipid (red) composite, (C and I) ThT, (E and K) protein-ThT composite, (F and L) metric matrix plots for the median TOS (linear) value for protein-ThT colocalization analysis. Lipids were visualized by doping with 0.1 mol % Liss Rho PE; FUS LC was imaged with 0.1 mol % of Cy5-labeled FUS LC. ThT, lipid, and FUS LC images were acquired at 405-, 561-, and 641-nm wavelength laser excitation, respectively. Scale bars, 1 μm.

With SFG experiments showing a dominant β sheet amide I signal for FUS LC when incubated with DOPS monolayers, we used thioflavin T (ThT), a well-known β sheet binding molecule (42, 43), to assay for β sheet structuring of FUS LC in the presence of PG and PS SLBs. ThT (blue) and Cy5–FUS LC (red) channels in Fig. 4 (E and K) show increased colocalization for PS SLBs. To quantitatively analyze the ThT and FUS LC colocalization, we used metric matrices for the threshold overlap score (TOS) for the analysis of localization patterns for ThT and Cy5–FUS LC channels (see Fig. 4E for PG and Fig. 4K for PS). Such analysis provides localization patterns by calculating values of a colocalization metric for many threshold combinations (44–46). The matrix showed colocalization at different threshold values for the signal intensities of Cy5–FUS LC and ThT. TOS matrices for both ThT–FUS LC on PG SLBs and ThT–FUS LC on PS-SLBs showed colocalization (TOS > 0) at many threshold combinations (Fig. 4, F and L, for PG and PS, respectively). However, at high signal intensities, i.e., small FT for Cy5 and small FT for ThT, there are some differences in FUS LC–ThT colocalization between the PG and PS FUS LC samples. PS SLBs showed higher ThT–FUS LC TOS (more red pixels in Fig. 4, F and L) compared to PG-SLBs. Figure S9 shows an additional SLB experiment with TIRF images from which the same conclusions can be drawn. This quantitatively demonstrates a higher degree of protein-ThT colocalization in ThT and FUS LC on PS SLBs, which is consistent with the increased β sheet presence observed in SFG spectroscopy of FUS LC at PS monolayers.

DISCUSSION

Nonspecific interactions between anionic lipids (in this case, DOPS and DOPG) and Q/S/Y/G-rich FUS LC domain, but not DOPC lipids, showed the ability to substantially reduce the threshold for FUS LC condensation (by at least 30-fold) compared to pure FUS LC in solution. Reduction of the FUS LC phase separation concentration is similar to what has been seen for specific interactions between FUS LC and membranes. Notably, the FUS LC–lipid clusters that formed here via nonspecific interactions are more solid-like than those created and previously observed from specific interactions between phase-separated proteins and lipids (14, 24). While DOPS and DOPG lipids both catalyze FUS LC condensation with lipids through nonspecific interactions, the difference in FUS LC structure at the two lipid interfaces shows that not all anionic lipids lead to the same protein-lipid cluster formation. Thus, head group charge is not the only important feature of lipids in promoting protein condensation.

The unique interactions responsible for FUS LC–phospholipid phase separation at the PS or PG lipid interfaces appear to depend on the nature of the head group, possibly originating from differences in lipid packing or head group charge density. Such molecular-level discrimination allows different lipids to manipulate FUS LC folding and eventually form phase-separated protein-lipid clusters that are distinct in composition and structure (Fig. 5). A similar observation of unique protein-lipid interaction has been recently reported for nonspecific, electrostatic interactions of aggregation-prone α-synuclein with PG and PS SUVs (36). In that study, Hannestad et al. (36) found changes in adsorption kinetics and remodeling of SUVs, whereas we find unique protein structuring and protein-lipid cluster composition for the two SUVs. α-Synuclein has an N-terminal amphipathic helix that is known to mediate interaction with membranes, while FUS LC has no obvious lipid-binding domain. Previous work on α-synuclein has suggested that defects in lipid packing could strongly affect protein-lipid interaction, with poorer packing increasing interaction (47, 48). We found that PS SUVs, which contain slightly less packed lipids compared to PG SUVs, showed a larger FUS LC:lipid ratio. In addition, FUS LC ordered into β sheet structures at the PS lipid interface but remained unstructured at the PG interface. Given that FUS LC does not have an obvious membrane-interacting domain, clarifying the mechanisms through which PG and PS lipid interactions affect FUS LC ordering is an area of future interest.

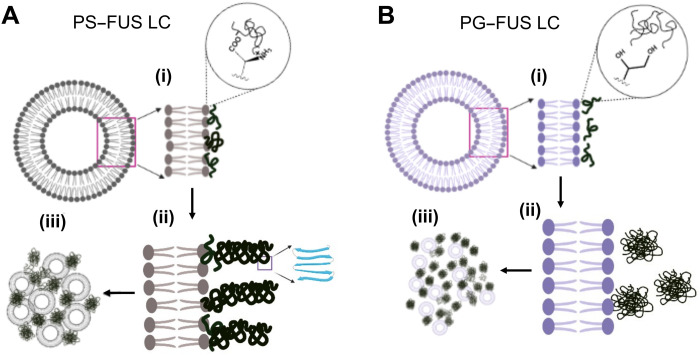

Fig. 5. Schematic representation of FUS LC–lipid cluster formation on DOPG and DOPS membranes.

Phase separation of FUS LC takes place in the presence of (A) DOPS SUVs and (B) DOPG SUVs. (i) Noncovalent interaction between protein and lipid head groups, (ii) phase separation and/or ordering of FUS LC at lipid interfaces with β sheet ordering of FUS LC on PS membranes, and (iii) the formation of micrometer-sized FUS LC–lipid clusters.

In conclusion, we have shown that FUS LC phase separation can be catalyzed by nonspecific interactions with negatively charged lipid membranes, despite having a slightly negative charge at physiological pH. FUS LC together with negatively charged, PS or PG, lipids resulted in phase separation of FUS LC at 5 μM bulk concentration, which is ~30-fold lower than is required for FUS LC alone under identical buffer conditions. Unexpectedly, PS membranes lead to the formation of β sheet structures at the lipid interface, whereas PG lipids did not lead to discernible protein structuring. This differential protein structuring perhaps arises from the different charge density of the head groups or lipid packing in PG versus PS lipids. Our results suggest that PG/PS lipids in the cell cytosol could lead to increased phase separation of FUS, and possibly similarly disordered proteins such as TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43), into solid-like clusters in contrast to liquid-like condensation from protein-protein or protein-RNA interactions in the absence of lipids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

DOPG, DOPS, DOPC, and 18:1 Liss Rhod PE were purchased from Avanti and used as received. All solvents and other materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without any further distillation.

Protein expression and purification

RP1B FUS LC 1–163 plasmid for protein expression was a gift from N. Fawzi (Addgene plasmid #127192; http://n2t.net/addgene:127192; Research Resource Identifier: Addgene_127192). Human FUS LC (residues 1 to 163) was expressed in chemically competent Escherichia coli bacterial strain. Cells were grown in LB medium containing kanamycin, shaking at 37°C until reaching an optical density at 600 nm within 0.6 to 1. Expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to its final concentration of 1 μM. After 4 hours of IPTG addition, cells were centrifuged at 4500g for 10 min at 4°C. Resultant pellet was stored at −20°C. For cell lysis, the pellet was redispersed in 20 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (containing 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole) and sonicated in an ice bath. The lysed cells were sediment by centrifugation at 18,500g for 1 hour at 4°C. Obtained pellet was redispersed in solubilizing buffer [phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 8 M urea] and stirred overnight at 4°C. Sample was centrifuged again at 18,500g for 1 hour at 4°C, and the supernatant was loaded to Ni-NTA agarose resin–containing columns. After binding of His-tagged protein to Ni-NTA (for 1 hour at 4°C), the unbound proteins and cell fragments were washed several times with phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 300 mM NaCl and 5 mM imidazole. Protein of interest was subsequently eluted in steps by running through the washing buffer with increasing imidazole concentration (10, 20, 40, and 100 mM). Purified protein was cleaved by diluting in solubilizing buffer with the addition of tobacco etch virus protease with a 1:10 mass ratio. Cleaved purified protein was buffer-exchanged to CAPS (N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid) (pH 11) overnight, then concentrated using a 3-kDa Amicon filter, and stored at −80°C.

Protein labeling

Cy3-NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) ester or Cy5-NHS ester dyes (Lumiprobe) were dissolved in 100 μl of dry DMF (N,N′-dimethylformamide) to make the stock of 10 mg/ml. Molar excess (10×) of dye solution in DMF was added to the FUS LC protein, and the resultant mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. The excess dye was removed by dialysis against 20 mM CAPS (pH 11) at 4°C for 24 hours with change of buffer every 4 hours. The labeled FUS LC was concentrated using a 3-kDa Amicon filter, the percentage of dye labeling was confirmed by an ultraviolet-visible spectrometer, and protein was stored at −80°C for further use.

Preparation of SUVs

We used a standard method for SUV preparation. Briefly, lipids were spread on a fresh standard glass vial, hydrated with agitation, and then detailed to obtain a homogeneous distribution of vesicles. Typically, 1 mg of either DOPG or DOPS was dissolved in 1 ml of chloroform (for fluorescence experiments, 0.1 weight % of 18:1 Liss Rhod PE was doped in the lipid solution) and mixed thoroughly by vortexing for 10 s, and then volatile was removed under vacuum to yield a lipid film on the vial walls. Next, the dried lipid film was hydrated with PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and incubated overnight at 4°C to yield large, multilamellar vesicles. Disruption of multilamellar vesicles into SUVs was done by a probe tip sonicator at 40% amplitude for ~10 min. The average hydrodynamic diameter of the SUVs was measured by DLS studies.

SUV-derived cluster formation

FUS LC in CAPS buffer (pH 11) was mixed with SUVs (~1015 SUVs/ml; lipid concentration of 1 mg/ml) in 500 μl of PBS, and the final pH of the mixture was adjusted to 7.4. The final concentration of FUS LC was 10 μM. The mixture was incubated for 2 hours at 22°C for further use. All mixing was performed at room temperature. The imaging was done on the Olympus IX70 microscope by drop-casting the solution on the glass slide (20 mm by 20 mm). Image analysis was carried out with FIJI. Additional methods for SFG spectroscopy, SP measurements, BCARS microscopy, and TIRF microscopy are in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Pütz and S. Turk for assistance with protein purification and quality control (mass spectrometry). We also thank M. Gelléri from the Institute of Molecular Biology Microscopy Core Facility for technical advice on and use of the Visitron TIRF system.

Funding: S.C., Y.K., and S.H.P. acknowledge support from the Human Frontier Science Program RGP0045/2018, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SPP 2191 #PA2526/3-1, the National Science Foundation #2146549, and Welch Foundation F-2008-20190330.

Author contributions: S.C., M.B., and S.H.P. designed and conceived the study. S.C. and D.M. performed and analyzed the FRAP, light microscopy, and TIRF measurements. S.C., E.H., and Y.K. performed and analyzed the BCARS measurements. D.M. and S.C. performed and analyzed the SFG studies. M.B., G.G., and S.H.P. supervised the study. S.C., D.M., M.B., and S.H.P. wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Methods

Figs. S1 to S9

Tables S1 to S4

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Simons K., Ikonen E., Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387, 569–572 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingwood D., Simons K., Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 327, 46–50 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikonen E., Roles of lipid rafts in membrane transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 470–477 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Meer G., Voelker D. R., Feigenson G. W., Membrane lipids: Where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 112–124 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uversky V. N., Intrinsically disordered proteins in overcrowded milieu: Membrane-less organelles, phase separation, and intrinsic disorder. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 44, 18–30 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu L., Brangwynne C. P., Nuclear bodies: The emerging biophysics of nucleoplasmic phases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 34, 23–30 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel A., Lee H. O., Jawerth L., Maharana S., Jahnel M., Hein M. Y., Stoynov S., Mahamid J., Saha S., Franzmann T. M., Pozniakovski A., Poser I., Maghelli N., Royer L. A., Weigert M., Myers E. W., Grill S., Drechsel D., Hyman A. A., Alberti S., A liquid-to-solid phase transition of the ALS protein FUS accelerated by disease mutation. Cell 162, 1066–1077 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakya A., King J. T., DNA local-flexibility-dependent assembly of phase-separated liquid droplets. Biophys. J. 115, 1840–1847 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroschwald S., Munder M. C., Maharana S., Franzmann T. M., Richter D., Ruer M., Hyman A. A., Alberti S., Different material states of Pub1 condensates define distinct modes of stress adaptation and recovery. Cell Rep. 23, 3327–3339 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke K. A., Janke A. M., Rhine C. L., Fawzi N. L., Residue-by-residue view of in vitro FUS granules that bind the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 60, 231–241 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elbaum-Garfinkle S., Kim Y., Szczepaniak K., Chen C. C. H., Eckmann C. R., Myong S., Brangwynne C. P., The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7189–7194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu A. P., Richmond D. L., Maibaum L., Pronk S., Geissler P. L., Fletcher D. A., Membrane-induced bundling of actin filaments. Nat. Phys. 4, 789–793 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firat-Karalar E. N., Welch M. D., New mechanisms and functions of actin nucleation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 4–13 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan F., Alimohamadi H., Bakka B., Trementozzi A. N., Day K. J., Fawzi N. L., Rangamani P., Stachowiak J. C., Membrane bending by protein phase separation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone M. B., Shelby S. A., Núñez M. F., Wisser K., Veatch S. L., Protein sorting by lipid phase-like domains supports emergent signaling function in B lymphocyte plasma membranes. eLife 6, e19891 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auluck P. K., Caraveo G., Lindquist S., α-Synuclein: Membrane interactions and toxicity in Parkinson’s disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 211–233 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fusco G., de Simone A., Arosio P., Vendruscolo M., Veglia G., Dobson C. M., Structural ensembles of membrane-bound α-synuclein reveal the molecular determinants of synaptic vesicle affinity. Sci. Rep. 6, 27125 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galvagnion C., Buell A. K., Meisl G., Michaels T. C. T., Vendruscolo M., Knowles T. P. J., Dobson C. M., Lipid vesicles trigger α-synuclein aggregation by stimulating primary nucleation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 229–234 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habchi J., Chia S., Galvagnion C., Michaels T. C. T., Bellaiche M. M. J., Ruggeri F. S., Sanguanini M., Idini I., Kumita J. R., Sparr E., Linse S., Dobson C. M., Knowles T. P. J., Vendruscolo M., Cholesterol catalyses Aβ42 aggregation through a heterogeneous nucleation pathway in the presence of lipid membranes. Nat. Chem. 10, 673–683 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wegmann S., Eftekharzadeh B., Tepper K., Zoltowska K. M., Bennett R. E., Dujardin S., Laskowski P. R., Kenzie D. M., Kamath T., Commins C., Vanderburg C., Roe A. D., Fan Z., Molliex A. M., Hernandez-Vega A., Muller D., Hyman A. A., Mandelkow E., Taylor J. P., Hyman B. T., Tau protein liquid–liquid phase separation can initiate tau aggregation. EMBO J. 37, e98049 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chirita C. N., Necula M., Kuret J., Anionic micelles and vesicles induce tau fibrillization in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25644–25650 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao H., Tuominen E. K., Kinnunen P. K., Formation of amyloid fibers triggered by phosphatidylserine-containing membranes. Biochemistry 43, 10302–10307 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murthy A. C., Dignon G. L., Kan Y., Zerze G. H., Parekh S. H., Mittal J., Fawzi N. L., Molecular interactions underlying liquid−liquid phase separation of the FUS low-complexity domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 637–648 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Protter D. S., Rao B. S., Van Treeck B., Lin Y., Mizoue L., Rosen M. K., Parker R., Intrinsically disordered regions can contribute promiscuous interactions to RNP granule assembly. Cell Rep. 22, 1401–1412 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portz B., Lee B. L., Shorter J., FUS and TDP-43 phases in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 46, 550–563 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorent J., Levental K. R., Ganesan L., Rivera-Longsworth G., Sezgin E., Doktorova M., Lyman E., Levental I., Plasma membranes are asymmetric in lipid unsaturation, packing and protein shape. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 644–652 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray S., Singh N., Kumar R., Patel K., Pandey S., Datta D., Mahato J., Panigrahi R., Navalkar A., Mehra S., Gadhe L., Chatterjee D., Sawner A. S., Maiti S., Bhatia S., Gerez J. A., Chowdhury A., Kumar A., Padinhateeri R., Riek R., Krishnamoorthy G., Maji S. K., α-Synuclein aggregation nucleates through liquid–liquid phase separation. Nat. Chem. 12, 705–716 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau H. K., Paul A., Sidhu I., Li L., Sabanayagam C. R., Parekh S. H., Kiick K. L., Microstructured elastomer-PEG hydrogels via kinetic capture of aqueous liquid–liquid phase separation. Adv. Sci. 5, 1701010 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paul A., Wang Y., Brännmark C., Kumar S., Bonn M., Parekh S. H., Quantitative mapping of triacylglycerol chain length and saturation using broadband CARS microscopy. Biophys. J. 116, 2346–2355 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freudiger C. W., Pfannl R., Orringer D. A., Saar B. G., Ji M., Zeng Q., Ottoboni L., Ying W., Waeber C., Sims J. R., de Jager P. L., Sagher O., Philbert M. A., Xu X., Kesari S., Xie X. S., Young G. S., Multicolored stain-free histopathology with coherent Raman imaging. Lab. Invest. 92, 1492–1502 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji M., Arbel M., Zhang L., Freudiger C. W., Hou S. S., Lin D., Yang X., Bacskai B. J., Xie X. S., Label-free imaging of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease with stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat7715 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slipchenko M. N., Le T. T., Chen H., Cheng J.-X., High-speed vibrational imaging and spectral analysis of lipid bodies by compound Raman microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 113, 7681–7686 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee C., Bain C. D., Raman spectra of planar supported lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1711, 59–71 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dmitriev A., Surovtsev N., Temperature-dependent hydrocarbon chain disorder in phosphatidylcholine bilayers studied by Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 119, 15613–15622 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsson K., Rand R., Detection of changes in the environment of hydrocarbon chains by Raman spectroscopy and its application to lipid-protein systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Lipids Lipid Metab. 326, 245–255 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannestad J. K., Rocha S., Agnarsson B., Zhdanov V. P., Wittung-Stafshede P., Höök F., Single-vesicle imaging reveals lipid-selective and stepwise membrane disruption by monomeric α-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 14178–14186 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu X., Suhr H., Shen Y., Surface vibrational spectroscopy by infrared-visible sum frequency generation. Phys. Rev. B 35, 3047–3050 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barth A., Zscherp C., What vibrations tell about proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 35, 369–430 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan E. C., Wang Z., Fu L., Proteins at interfaces probed by chiral vibrational sum frequency generation spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 119, 2769–2785 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meister K., Bäumer A., Szilvay G. R., Paananen A., Bakker H. J., Self-assembly and conformational changes of hydrophobin classes at the air–water interface. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 4067–4071 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barth A., Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1073–1101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biancalana M., Koide S., Molecular mechanism of thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 1405–1412 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vassar P. S., Culling C. F., Fluorescent stains, with special reference to amyloid and connective tissues. Arch. Pathol. 68, 487–498 (1959). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheng H., Stauffer W., Lim H. N., Systematic and general method for quantifying localization in microscopy images. Biol. Open 5, 1882–1893 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheng H., Stauffer W. T., Hussein R., Lin C., Lim H. N., Nucleoid and cytoplasmic localization of small RNAs in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 2919–2934 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stauffer W., Sheng H., Lim H. N., EzColocalization: An ImageJ plugin for visualizing and measuring colocalization in cells and organisms. Sci. Rep. 8, 15764 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ouberai M. M., Wang J., Swann M. J., Galvagnion C., Guilliams T., Dobson C. M., Welland M. E., α-Synuclein senses lipid packing defects and induces lateral expansion of lipids leading to membrane remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 20883–20895 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nuscher B., Kamp F., Mehnert T., Odoy S., Haass C., Kahle P. J., Beyer K., α-Synuclein has a high affinity for packing defects in a bilayer membrane: A thermodynamics study. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21966–21975 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koulouras G., Panagopoulos A., Rapsomaniki M. A., Giakoumakis N. N., Taraviras S., Lygerou Z., EasyFRAP-web: A web-based tool for the analysis of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching data. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W467–W472 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Billecke N., Rago G., Bosma M., Eijkel G., Gemmink A., Leproux P., Huss G., Schrauwen P., Hesselink M. K. C., Bonn M., Parekh S. H., Chemical imaging of lipid droplets in muscle tissues using hyperspectral coherent Raman microscopy. Histochem. Cell Biol. 141, 263–273 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cicerone M. T., Aamer K. A., Lee Y. J., Vartiainen E., Maximum entropy and time-domain Kramers–Kronig phase retrieval approaches are functionally equivalent for CARS microspectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 637–643 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schach D. K., Rock W., Franz J., Bonn M., Parekh S. H., Weidner T., Reversible activation of a cell-penetrating peptide in a membrane environment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12199–12202 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Y. Shen, Fundamentals of Sum-Frequency Spectroscopy (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosseinpour S., Roeters S. J., Bonn M., Peukert W., Woutersen S., Weidner T., Structure and dynamics of interfacial peptides and proteins from vibrational sum-frequency generation spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 120, 3420–3465 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Backus E. H., Bonn D., Cantin S., Roke S., Bonn M., Laser-heating-induced displacement of surfactants on the water surface. J. Phys. Chem. B. 116, 2703–2712 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makra I., Terejánszky P., Gyurcsányi R. E., A method based on light scattering to estimate the concentration of virus particles without the need for virus particle standards. MethodsX 2, 91–99 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lambert A. G., Davies P. B., Neivandt D. J., Implementing the theory of sum frequency generation vibrational spectroscopy: A tutorial review. J. App. Spec. Rev. 40, 103 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dreier L. B., Bonn M., Backus E. H., Hydration and orientation of carbonyl groups in oppositely charged lipid monolayers on water. J. Phys. Chem. B. 123, 1085–1089 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seki T., Yu C. C., Chiang K. Y., Tan J., Sun S., Ye S., Bonn M., Nagata Y., Disentangling sum-frequency generation spectra of the water bending mode at charged aqueous interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B. 125, 7060–7067 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mondal J. A., Nihonyanagi S., Yamaguchi S., Tahara T., Structure and orientation of water at charged lipid monolayer/water interfaces probed by heterodyne-detected vibrational sum frequency generation spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10656–10657 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods

Figs. S1 to S9

Tables S1 to S4

References