Abstract

Background and Objectives:

To assess the safety and efficacy of single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SPLC) for the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis in different gallbladder pathologic conditions.

Methods:

All patients who underwent SPLC in our department between October 1, 2017 and March 31, 2020 were registered consecutively in a prospective database. Patients’ charts were retrospectively divided according to histological diagnosis: normal gallbladder (NG) (n = 13), chronic cholecystitis (CC) (n =47), and acute cholecystitis (AC) (n = 10). The parameters for assessing the procedure outcome included operative time, blood loss, use of additional trocars, conversion to laparotomy, intraoperative and postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay. Patient groups were statistically compared.

Results:

Seventy patients underwent SPLC. Duration of surgery increased from NG (55 ± 22.7 min) to CC (70 ± 33.5 min), and to AC patients (110.5 ± 50.5 min), which is statistically significant (P = .001). Postoperative complication rates were 7.6% in NG patients, 17% in CC, and 30% in AC (P = .442). Length of hospitalization was shorter for NG patients (1.0 ± 0.6 days) versus CC (2.0 ± 1.1 days) and AC patients (2.0 ± 4.7 days), with statistical significance (P = .020). Multivariate analysis found that pathology type and the occurrence of postoperative complications were independent predictors for prolonged operative times and prolonged hospital stay, respectively.

Conclusion:

SPLC is feasible for acute and chronic cholecystitis with good procedural outcomes. Since SPLC technique itself can be sometimes challenging with the existing technology, its application, especially in cases of acute cholecystitis, should be done with caution. Only prospective randomized studies on this approach for acute and chronic gallbladder diseases will assess the complete reliability of this technique.

Keywords: Acute cholecystitis, Chronic cholecystitis, Single-port access surgery, Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Single incision laparoscopic surgery, Laparo-endoscopic single-site surgery

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, interest in single-port laparoscopic surgery has awakened as a new minimally invasive approach. Since the advent of the first single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy described in 1995 by Navarra and colleagues,1 various other abdominal interventions have benefited from this approach.2–5 Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SPLC) for uncomplicated benign gallbladder disease is comparable to conventional multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy in regard to safety and efficacy.6–8 In addition to well-established cosmetic advantage, less postoperative pain and faster return to normal activity are potential benefits. 9–12 However, a nonstatistically significant trend towards a higher rate of complications and a higher risk of trocar site hernia at follow-up have been reported for SPLC compared to traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy.13,14 Moreover, a slight increase in serious adverse events such as bile duct injury, reoperations, bile leaks, or intra-abdominal collections requiring drainage have been described.15 This could be the reason why this approach has been poorly studied in cases of acute or chronic cholecystitis, conditions that can make the intervention more complex and at greater risk of procedural complications.

To date, only a few retrospective monocentric studies have addressed this subject, so that the preservation of safety and effectiveness of the single-port technique even in the case of acute or chronic cholecystitis is not established yet.16,17 The purpose of this work is to verify the impact of gallbladder pathologic conditions in the outcome of SPLC and in particular to assess whether safety and efficacy of the procedure are preserved in chronic cholecystitis (CC) and acute cholecystitis (AC) conditions. Hence, a series of 70 SPLC patients was retrospectively reviewed and potential predictive parameters that can affect intraoperative or immediate postoperative outcome were investigated as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SPLC was introduced in our department on October 1, 2017. Since then, all the laparoscopic cholecystectomies (n = 70) performed until March 31, 2020 were SPLCs and registered consecutively in a prospective database. Patients characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), previous abdominal surgery, and associated comorbidities. All the SPLC procedures were performed by three senior surgeons (MC, TT, and SPM) experienced in laparoscopic procedures. All patients with symptomatic gallbladder stones were included. Patients’ charts were retrospectively divided according to histological diagnosis into normal gallbladder (NG) (n = 13), CC (n = 47), and AC (n = 10).

The outcome of the procedure was defined by the following parameters: duration of operation (time from skin incision to wound dressing), estimated blood loss, associated operations, surgical conversion, need of additional trocars, abdominal drain positioning, postoperative pain measured by visual analogue scale (VAS), analgesia requirement, length of hospital stay, and postoperative morbidity (according to Clavien-Dindo Classification).

Surgical Technique

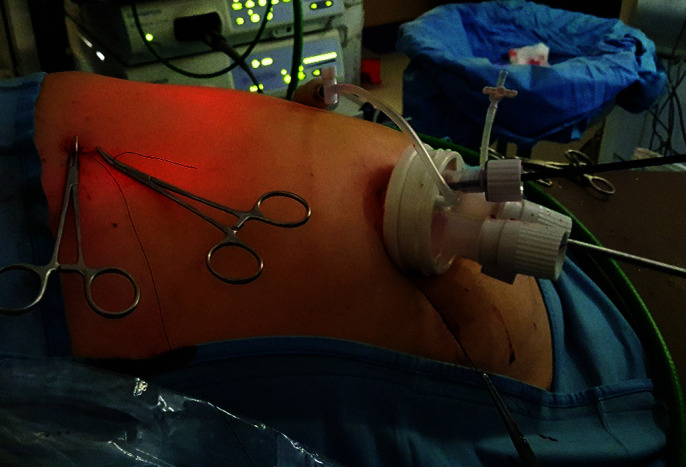

Surgical technique for SPLC is well described in the literature.18 In summary, for SPLC technique a single-port device with four-channels (Single port, Unimax Medical Systems Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) is inserted through the umbilicus (Figure 1). After creation of pneumoperitoneum, a 10-mm 30-degree angle telescope is introduced. Dissection is conducted with a reusable 5-mm laparoscopic hook and a 5-mm reusable prebent grasper (Olympus Medical Systems, Hamburg, Germany).

Figure 1.

The four-channel Unimax single-port positioned for a laparoscopic procedure and the transabdominal stay sutures passed for gallbladder suspension.

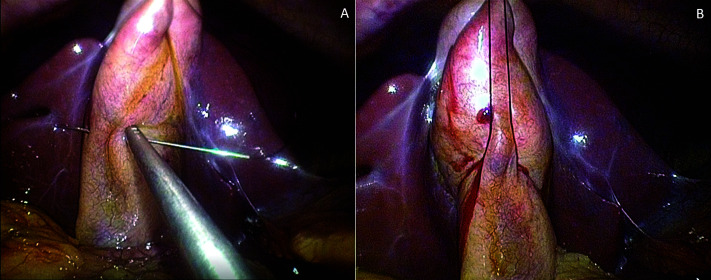

To obtain a correct exposition, one percutaneous thread can be passed in the gallbladder fundus and used for retraction. In case of a really long gallbladder, an additional suture is passed in the infundibulum (Figure 2 A-B). This suture allows a “puppeteering technique” for mobilization of the infundibulum, enabling complete visualization of Calot’s triangle by suture traction.10

Figure 2.

(A) A second suture is passed through the gallbladder’s infundibulum. (B) Gallbladder retraction is completed for calot’s triangle exposition.

The rest of the procedure follows the steps of traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. No specimen retrieval bag is used as the Unimax system is designed to act as a wound protector.

Statistical Methods

Continuous and categorical variables were presented as median (standard deviation) and n (%) respectively. We compared differences among histological groups using χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and ANOVA or nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Univariable and multivariable models were fitted to assess which variables were associated with duration of surgery (on log-scale due to high skewness) and hospital stay; univariable logistic models were fitted to explore risk-factors associated with morbidities. A two-sided α less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were done using the SAS software (version 90.4).

RESULTS

SPLC patients, divided according to the histological diagnosis into NG, CC, and AC groups, did not differ significantly regarding age, sex, and comorbidity (Table 1). Pre-operative endoscopic treatment for suspected choledocholithiasis was performed in three patients. Previous abdominal surgery in the upper quadrants was not experienced in any group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Postoperative Results Grouped for Hystological Diagnosis

| Characteristic | NG (n = 13) | CC (n = 47) | AC (n = 10) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, F/M | 7/6 | 31/16 | 4/6 | .277 |

| Age, years | 50 (14.9) | 58 (15.6) | 54.5 (14.8) | .588 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4 (3.6) | 26 (5.3) | 260.4 (4.7) | .041* |

| Associated comorbidities, patients (%) | 5 (38.4) | 28 (59.5) | 5 (50) | .383 |

| Duration of surgery, min | 55 (22.7) | 70 (33.5) | 110 (50.5) | .001* |

| Trocar addition, patients (%) | 0 | 2 (4.26) | 2 (20) | |

| Blood loss, patients (%) | 1 (7.6) | 4 (8.5) | 5 (50) | .006 |

| Surgery conversion, patients (%) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (10) | |

| Associated operation, patients (%) | 1 (7.6) | 3 (6.3) | 2 (20) | |

| Drain positioning, patients (%) | 0 | 2 (4.2) | 3 (30) | |

| VAS at 4 h | 0 (2) | 10.5 (1.9) | 1 (1.6) | .664* |

| VAS at 24 h | 3 (2.7) | 0 (1.8) | 1.5 (1.8) | .045* |

| Pain medications, patients (%) | 11 (84.6) | 41 (89.1) | 9 (90) | .854 |

| Paracetamol, g/d | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (3.9) | .634* |

| Toradol, mg/d | 7.5 (18.1) | 10 (12.9) | 11.6 (22.5) | .405* |

| Hospital stay, days | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (4.7) | .020* |

| Morbidity, patients (%) | 1 (7.6) | 8 (17) | 3 (30) | .442 |

Note: Values are meant as median (SD) unless indicated otherwise.

Abbreviations: NG, normal gallbladder; CC, chronic cholecystitis; AC, acute cholecystitis; BMI, body-mass index; VAS, visual analogue scale.

*nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test.

Duration of surgery increased from NG (55 ± 220.7 min), to CC (70 ± 330.5 min) and to AC patients (1100.5 ± 500.5 min), statistical significance (P = .001).

A conversion to an open approach due to a bleeding from an hepatic vein branch of the liver bed was experienced in a CC patient. Another surgical conversion occurred in an AC patient with a gangrenous cholecystitis for a complete transection of the common bile duct necessitating an immediate choledocho-choledochal anastomosis. In both cases an abdominal drain was left in place at the end of surgery. No surgical conversion occurred in NG patients.

The addition of one trocar was required in two (20%) difficult AC and two (40.2%) CC procedures respectively. Blood loss >100 ml occurred in one CC and one AC patient, it was < 50 ml in four AC, three CC, and one NG patients respectively.

An appendectomy and an annessectomy were associated with cholecystectomy in the AC group, an appendectomy and two umbilical hernia repairs in the CC group, and an umbilical hernia was repaired in an NG patient. Clinical parameters able to influence the operative time were analyzed. Univariate analysis showed that male gender (P = .011), trocar addition (P = .014), blood loss (P < .001), surgical conversion (P = .016), and AC condition (P < .001) were significantly associated with the risk of longer duration of surgery. To avoid overfitting, only the most biologically relevant variables were included in the multivariable models and all the above-mentioned variables were entered. The final model retained AC condition (P = .0038), blood loss (P = .0002), and sex (P = .049). According to VAS evaluation, the pain profile as well as the analgesics requirement were similar in all groups and did not differ significantly .

Length of hospitalization was shorter for patients operated on by SPLC with a NG (1.0 ± 0.6 days) when compared to the CC group (2.0 ± 1.1 days) and to the AC group (2.0 ± 4.7 days), reaching a statistically significant difference (P = .020). Clinical factors influencing the hospital stay in the whole group were analyzed. Univariate analysis showed that duration of surgery (P < .001), blood loss (P = .001), surgical conversion (P < .001), drain positioning (P < .001), morbidity (P < .001), and AC condition (P = .006) were significantly associated with the risk of longer duration of hospitalization. As for the previous model, only the most relevant variables were included in the multivariable models and all the above-mentioned variables were entered. The final model retained the occurrence of postoperative complications (P = .001).

Postoperative complication rates were 7.6% in the NG group, 17% in the CC group and 30% in the AC group (P = .442). In each group mostly minor complications such as fever as the only symptom (two CC and two AC patients) and four prolonged abdominal pain in right hypocondrium probably due to intercostal neuralgia (one NG and three CC patients) were experienced. The AC patient who had the common bile duct reparation experienced a bile leak that was managed conservatively and he was discharged 17 days after surgery. Postoperative complications of Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb occurred in one CC and one AC patient. In the former case, an 83-year-old ASA3 arteriopathic dialysis patient was reoperated on postoperative day three for a massive intestinal infarction which resulted in death the next day. The second patient needed reoperation through laparotomy on the first postoperative day to manage a bile leak from the liver bed.

Univariable logistic models were fitted to explore risk-factors associated with morbidity. Considering the small number of complications (n = 12) we did not fit multivariable logistic models. The occurrence of postoperative complications was found to be 20.4-fold higher in the CC group and 50.1-fold higher in the AC group when compared to the NG group.

DISCUSSION

In general, there is a lack of high-level evidence and of long-term follow-up in the field of single-incision endoscopic surgery. To draw the consensus statement on single-incision endoscopic surgery, the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery selected 11 randomized controlled trials for review.19 Overall, evidence on SPLC suggests better cosmetic results and less postoperative pain when compared to standard LC. On the other hand, the operating time is longer. Concerning morbidity, inconsistent results were found. However, these studies have several limitations. Most of the studies included only patients with BMI < 30 kg/m2; moreover, previous abdominal surgery and presence of acute cholecystitis were exclusion criteria in all studies. Furthermore, in the two main European randomized controlled trials that analyzed SPLC, the SPOCC 20 and the MUSIC 8 trials, the number of cases per center slightly exceeded the learning curve, averaging between 27 and 35 cases. Thus, in order to investigate the impact of a gallbladder’s pathologic condition on this procedure, it is necessary to refer to large casuistries of Eastern experience in which acute cholecystitis condition is taken into account.17, 21,22 According to these studies, the gallbladder's inflammatory state seems to affect the outcome of the procedure.

Similarly in our study, the surgical outcome varies according to the pathology, with increased difficulties from NG to CC and to AC conditions. In particular, the duration of the intervention for AC is doubled when compared to NG. Also, the need for trocar addition (20%) and conversion rates (10%) are higher in AC condition, but still in line with the data presented in the literature. Ikumoto et al.22 in a retrospective study on 100 patients undergoing SPLC for AC report a 12% rate of conversion laparotomies. In a study comparing SPLC in 52 AC patients vs. 308 patients without acute cholecystitis (NAC), Sato et al.17 report a 60% rate of additional trocar insertion.

The length of hospital stay also reflects the gallbladder's pathologic conditions, since the difference among groups reached a statistical significance in our study. In any case, a median stay of two days for AC patients is a good result if we consider a median stay of six days reported by the main case studies.16, 17,22 Concerning morbidity, complication rates were 7.6% in the NG group, 17% in the CC group and 30% in the AC group (P = .442). Our data correlate with the previously cited study by Sato et al.,17 in which the postoperative complication rate was significantly higher in the AC group than in the NAC group (12% vs. 48%; P = .0238).

A worse outcome in case of severe cholecystitis is also demonstrated with the use of traditional laparoscopy. In fact, in a meta-analysis including seven studies with 1,408 patients treated with standard LC for severe cholecystitis or uncomplicated gallbladder disease, a threefold higher conversion rate was found in the former group and morbidity rate increased from 11% to 20%.23

These numerical data are comparable to those of the previously cited studies on SPLC showing the reliability of the technique despite a recognized increased difficulty. No statement can be made regarding the difference in common bile duct lesion occurrence since overall incidence is very low. In fact, although our series is small, the only bile duct injury occurred in an AC patient where the anatomy of Calot was practically unrecognizable.

Therefore, it is of paramount importance to maintain all principles of safe dissection during SPLC, especially in case of AC and CC condition. The use of intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) is advocated by some authors to assess the biliary anatomy.17 However, the use of IOC during SPLC can be challenging due to technical difficulty. The isolation of the cystic artery and duct following the Strasberg’s critical view of safety (CVS) principles represents another technical option to decrease the rate of common bile duct injury. The principle followed by some authors trying to obtain the CVS as the main achievement of the procedure and converting to multiport when CVS cannot be created seems correct to us.22

The reasons that make single-port technique challenging is that currently there are no dedicated instruments, only adaptations of instruments conceived for traditional laparoscopy. The known limitations of this technique are the reduced mobility and excursion of the instruments, the lack of triangulation with the possibility of clashing until some maneuvers otherwise feasible in traditional laparoscopy are rendered impossible. In light of this, the role of single-port technique in acute cholecystitis remains controversial. What is evident from our study and confirmed by literature data is that SPLC in AC and CC conditions is feasible but it is associated with longer operative times, increased blood loss, higher rate of additional trocar requirement, higher rate of postoperative complications, and longer hospital stay. The worst outcome is directly related to the inflammatory state of the gallbladder which makes the intervention more complex. Since SPLC technique itself can be sometimes challenging with the existing technology, its application in cases of acute cholecystitis should be done with caution.

CONCLUSION

Each case of symptomatic cholelithiasis with concomitant AC and CC must be well weighed before using single-port technique, especially in light of the relative recognized benefits such as better cosmesis and less pain. Furthermore, SPLC should be done by experienced laparoscopic surgeons who have passed the learning curve of this technique treating a reasonable number of cases with normal gallbladder. Only prospective randomized studies for acute and chronic gallbladder diseases will assess the complete reliability of this technique.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: none

Disclosure: none

Funding sources: none

Conflict of interests: none

Informed consent: Dr. Marco Casaccia declares that written informed consent was obtained from the patient/s for publication of this study/report and any accompanying images.

Contributor Information

Marco Casaccia, Surgical Clinic Unit I, Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics (DISC), Genoa University, Genoa, Italy..

Marta Ponzano, Unit of Clinical Epidemiology and Trials, National Institute for Cancer Research, Genoa, Italy..

Tommaso Testa, Surgical Clinic Unit I, Department of Surgery, San Martino Hospital, Genoa, Italy..

Sofia Paola Martigli, Surgical Clinic Unit I, Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics (DISC), Genoa University, Genoa, Italy..

Cecilia Contratto, Surgical Clinic Unit I, Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics (DISC), Genoa University, Genoa, Italy..

Franco De Cian, Surgical Clinic Unit I, Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics (DISC), Genoa University, Genoa, Italy..

References:

- 1.Navarra G, Pozza E, Occhionorelli S, Carcoforo P, Donini I. Short note: one wound laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84(5):695–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponsky TA, Diluciano J, Chwals W, Parry R, Boulanger S. Early experience with single port laparoscopic surgery in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19(4):551–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saber AA, El-Ghazaly TH, Dewoolkar AV. Single-incision laparoscopic bariatric surgery: a comprehensive review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(5):575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Targarona EM, Lima MB, Balague C, Trias M. Single-port splenectomy: current update and controversies. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7(1):61–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow AG, Purkayastha S, Zacharakis E, Paraskeva P. Single incision laparoscopic surgery for right hemicolectomy. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Thrumurthy S, Muirhead L, Kinross J, Paraskeva P. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) vs. conventional multiport cholecystectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(5):1205–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pisanu A, Reccia I, Porceddu G, Uccheddu A. Meta-analysis of prospective randomized studies comparing single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) and conventional multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CMLC). J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(9):1790–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arezzo A, Passera R, Bullano A, et al. Multi-port versus single-port cholecystectomy: results of a multi-centre, randomised controlled trial (MUSIC trial). Surg Endosc. 2017;31(7):2872–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee PC, Lo C, Lai PS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus minilaparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97(7):1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow A, Purkayastha S, Aziz O, Pefanis D, Paraskeva P. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for cholecystectomy: a retrospective comparison with 4-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2010;145(12):1187–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsimoyiannis EC, Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos G, et al. Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):1842–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucher P, Pugin F, Buchs NC, Ostermann S, Morel P. Randomized clinical trial of laparoendoscopic single-site versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2011;98(12):1695–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Cassera MA, Spaun GO, Hammill CW, Hansen PD, Aliabadi-Wahle S. Randomized controlled trial comparing single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;254(1):22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raakow J, Klein D, Barutcu AG, Biebl M, Pratschke J, Raakow R. Safety and efficiency of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy in obese patients: a case-matched comparative analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019;29(8):1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph M, Phillips MR, Farrell TM, Rupp CC. Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a higher bile duct injury rate: a review and a word of caution. Ann Surg. 2012;256(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob D, Raakow R. Single-port versus multi-port cholecystectomy for patients with acute cholecystitis: a retrospective comparative analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10(5):521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato N, Kohi S, Tamura T, Minagawa N, Shibao K, Higure A. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a retrospective cohort study of 52 consecutive patients. Int J Surg. 2015;17:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casaccia M, Palombo D, Razzore A, Firpo E, Gallo F, Fornaro R. Laparoscopic single-port versus traditional multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2019;23(3):e2018.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morales-Conde S, Peeters A, Meyer YM, et al. European association for endoscopic surgery (EAES) consensus statement on single-incision endoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(4):996–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lurje G, Raptis DA, Steinemann DC, et al. Cosmesis and body image in patients undergoing single-port versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multicenter double-blinded randomized controlled trial (SPOCC-trial). Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chuang SH, Chen PH, Chang CM, Lin CS. Single-incision vs three-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy for complicated and uncomplicated acute cholecystitis. WJG. 2013;19(43):7743–7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikumoto T, Yamagishi H, Iwatate M, Sano Y, Kotaka M, Imai Y. Feasibility of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7(19):1327–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borzellino G, Sauerland S, Minicozzi AM, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for severe acute cholecystitis. A meta-analysis of results. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]