Abstract

This letter to the editor considers outcomes for underrepresented populations across early phase pediatric oncology clinical trials, considering barriers to equitable representation of minorities in clinical trials.

Racial and ethnic minorities face systemic barriers to equitable representation in clinical trials.1 Snapshot data from the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration has shown Black and African American patients comprised less than 10% of study populations for clinical trials spanning from 2015 to 2020,2,3 which contrasts significantly from the current demographic landscape in the US. The extent of underrepresentation and outcomes for minority groups in early phase pediatric oncology studies is less well understood.

We sought to address this gap by re-analyzing our previously published systematic review assessing toxicity and response across phase I pediatric oncology trials4 to specifically evaluate representation of and outcomes for underrepresented groups. Articles were screened for reporting of race and ethnicity in baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes in the main text, tables, and figures. The percentage of patients who were Hispanic or Black was tabulated among all trials that reported both race and ethnicity.

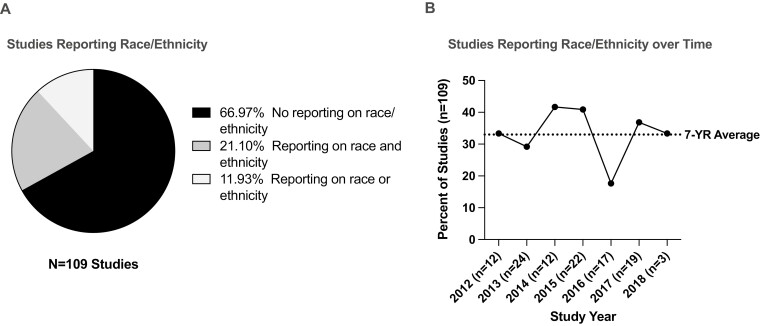

In total, 109 pediatric oncology clinical trial articles published between 2012 and 2018 were included, 78 (72%) of which incorporated targeted therapies. The total number of patients was 2713 with median age of 11 years (range 3–21). Median number of patients enrolled was 21 (range 4–79). Among all studies, 36 (33%) articles reported race or ethnicity in baseline patient characteristics, with 23 (21%) providing information on both race and ethnicity of trial participants (Fig. 1A). In these 23 studies, which included 644 (23.7%) patients, 107 (16.6%) patients were Hispanic, and 87 (13.5%) patients were Black. Reporting of race or ethnicity over time varied from 18% to 42% per year with no year-on-year trends (Fig. 1B). Only one study reported toxicity and response outcomes by race and ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Reporting of demographic trends in early phase pediatric oncology studies published between 2012 and 2018. (A) Percent of studies reporting demographic information for race and ethnicity. (B) Percent of studies reporting race or ethnicity of trial participants by publishing year.

While we sought to evaluate outcomes of racial/ethnic minority populations across early phase studies, reporting of racial/ethnic representation in early phase pediatric oncology trials was uncommon and inconsistent, precluding meaningful analysis of our primary aims. Moreover, reporting trends did not improve over time, and reporting of outcomes by race and ethnicity was virtually nonexistent. Although we are encouraged that representation in the small subset of trials (21%) that reported complete demographic information by race and ethnicity was comparable to the current US demographic landscape,5 without additional data, we simply cannot assume this is an accurate reflection of the landscape of enrollment across early phase pediatric oncology studies.

Our study serves to highlight the critical need to improve reporting of racial/ethnic representation in early phase pediatric oncology trials. Given how readily available such demographic information is, this should be a standard approach when reporting on trial data, even when numbers are limited. Such efforts would help to evaluate the extent of demographic underrepresentation, identify any demographic associated differential outcomes, and enable future systematic reviews and meta-analyses to examine toxicity and response outcomes by race and ethnicity. Ultimately, understanding demographic patterns for enrollment on early phase pediatric oncology studies is a first step to improving access to emerging therapies for groups that experience inferior cancer outcomes with conventional therapies.6,7

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and the Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center (ZIA BC 011823, N.N.S.). Research support was also provided by the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from the American Association for Dental Research and the Colgate-Palmolive Company (A.J.F.).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Contributor Information

Aiman J Faruqi, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA.

John A Ligon, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Julia W Cohen, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; Merck and Co, Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA.

Srivandana Akshintala, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Brigitte C Widemann, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Nirali N Shah, Pediatric Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Conflict of Interest

Julia W Cohen: Merck (E). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board.

References

- 1. Davis TC, Arnold CL, Mills G, Miele L.. A qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators of enrolling underrepresented populations in clinical trials and biobanking. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:74. 10.3389/fcell.2019.00074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bierer BE, Meloney LG, Ahmed HR, White SA.. Advancing the inclusion of underrepresented women in clinical research. Cell Reports Medicine. 2022:100553. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Camidge DR, Park H, Smoyer KE, et al. Race and ethnicity representation in clinical trials: findings from a literature review of Phase I oncology trials. Future Oncol. 2021;17(24):3271-3280. 10.2217/fon-2020-1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen JW, Akshintala S, Kane E, et al. A systematic review of pediatric Phase I trials in oncology: toxicity and outcomes in the era of targeted therapies. Oncologist. 2020;25(6):532-540. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nicholas Jones RM, Roberto Ramirez, Merarys Ríos-Vargas. 2020. Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. Census.gov (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html).

- 6. Eche IJ, Aronowitz T.. A literature review of racial disparities in overall survival of Black children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia compared with White children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2020;37(3):180-194. 10.1177/1043454220907547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shoag JM, Barredo JC, Lossos IS, Pinheiro PS.. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia mortality in Hispanic Americans. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(11):2674-2681. 10.1080/10428194.2020.1779260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]