Abstract

Mathematical relations for the number of mature T4 bacteriophages, both inside and after lysis of an Escherichia coli cell, as a function of time after infection by a single phage were obtained, with the following five parameters: delay time until the first T4 is completed inside the bacterium (eclipse period, ν) and its standard deviation (ς), the rate at which the number of ripe T4 increases inside the bacterium during the rise period (α), and the time when the bacterium bursts (μ) and its standard deviation (β). Burst size [B = α(μ − ν)], the number of phages released from an infected bacterium, is thus a dependent parameter. A least-squares program was used to derive the values of the parameters for a variety of experimental results obtained with wild-type T4 in E. coli B/r under different growth conditions and manipulations (H. Hadas, M. Einav, I. Fishov, and A. Zaritsky, Microbiology 143:179–185, 1997). A “destruction parameter” (ζ) was added to take care of the adverse effect of chloroform on phage survival. The overall agreement between the model and the experiment is quite good. The dependence of the derived parameters on growth conditions can be used to predict phage development under other experimental manipulations.

Studies on bacteriophage growth and development in the 1940s played a vital role in the history of molecular biology (11, 24, 29). The classical one-step growth experiment (17) defined latent period, rise time, and burst size, and the eclipse period was discovered by disrupting infected bacteria before their spontaneous lysis (14). By the time bacterial physiology was established as a discipline (25, 32), molecular biology had become so attractive that some unsolved questions in phage-host cell interactions have been ignored and never seriously looked at since. The vast amount of knowledge gained during the last 35 years on the biochemistry, genetics, and physiology of bacteria (23, 26, 30) enables a fresh look on these interactions, which may shed light on various cell properties (15, 20).

In a typical one-step growth experiment, a culture of cells is mixed with phage suspension at a low multiplicity of infection to guarantee single infections. Samples are withdrawn periodically and plated on a lawn of sensitive bacteria, and the number of phages is calculated from the number of plaques formed after overnight incubation. This straightforward procedure has recently been used to describe the development of the T4 bacteriophage inside Escherichia coli under varying well-defined physiological states of the host. The dependence of phage growth parameters on cell size, age, and shape, on rates of metabolism and chromosome replication, and on time of lysis was evaluated semiquantitatively (20). In this series of experiments, the parameters obtained were indeed distributed over wide ranges; they were however derived “by eye.” To obtain well-defined quantitative values of the parameters, they should be defined rigorously, and the complete time dependence of the process should be calculated and compared with the experiment. Such a quantitative model is developed here, with due note taken of the statistical distributions of the parameters within the populations of both phages and bacteria.

The former model of a one-step growth experiment (3, 12, 17) implicitly assumed that the latent period ends prior to cell burst and that the different numbers of PFU per bacterium (PPBs) obtained by titration as a function of time were therefore due to the different burst times of individual cells only. Since these times are normally distributed, the PPB should have increased as erfc[(q − t)/Δ], where q is the burst time (latent period) and 2Δ is the width of the normal distribution. Such an assumption would however entail a step function for chloroform titration of bacteria, which is not observed. The present model avoids such a limitation.

The model.

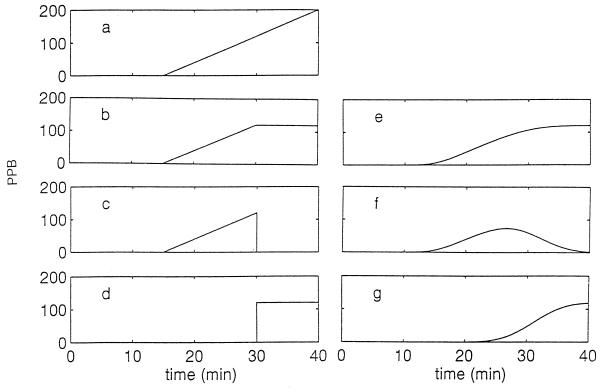

All times are measured from the moment of infection of an E. coli cell by a single wild-type bacteriophage T4. If no spread occurs in the times of onset and termination of phage multiplication, the number of PPB is ideal, as shown schematically in Fig. 1a through d. The time ν (eclipse period; 15 min in the example shown in Fig. 1a) is the average delay between infection and appearance (inside the cell) of the first complete phage. From this time onwards, the PPB is assumed to increase linearly during the rise period with a constant rate α (8 per min; Fig. 1a). The number of PPB (φ) stops increasing when the bacterium bursts, at the end of the latent period μ (on average, 30 min in the example shown in Fig. 1b), reaching a final value (burst size) of B = α(μ − ν) (120 phages in the example shown in Fig. 1b). The PPB inside an infected cell before its burst (φ1) is shown in Fig. 1c, and the number which emerges from lysed cells (φ2) is shown in Fig. 1d. Evidently, φ1 + φ2 = φ. The experiments (20) yield both φ and φ2 separately; φ2 is obtained by titrating phages in the suspension (17) while φ is obtained after lysing the cells artificially (4), such as with chloroform.

FIG. 1.

A schematic ideal situation of the increase in the number of T4 phages per Escherichia coli bacterium (PPB), with parameters as given in the text. (a) PPB if bacteria do not burst; (b) total PPB, in lysed and nonlysed cells; (c) PPB in nonlysed cells; (d) PPB in lysed cells (phages in suspension). Panels e, f, and g display schematically the nonideal cases (“real” situation) of those shown in panels b, c, and d, respectively.

These experiments, however, are performed for a population which is not ideal and for which μ and ν are distributed around their averages. Thus, in the population, ν and μ vary from one infected cell to another and from one infecting phage to another; the actual curves for the φs are thus smoother. These are shown schematically in Fig. 1e through g and are calculated below. In the model, both ν and μ are assumed to have Gaussian distributions around their averages with coefficients of variation ς/ν and β/μ (of 20%, 3 and 6 min, respectively, in the example shown in Fig. 1). The probability that the phages would start to multiply between t′ and t′ + dt′ is thus considered to be

|

1 |

Note that we follow the notation of reference 1 of a Gaussian distribution. Thus, ς in our case measures the time increment (positive or negative) with respect to ν, where probability decreases by l/e relative to the peak probability. A different notation is sometimes used (32), in which ς1 = ς21/2 appears instead of our ς.

In bacteria where phages started to multiply at time t′, the PPB at t > t′ will be α(t − t′). Therefore, the average PPB at time t is given by

|

2 |

provided, of course, that no bacterium bursts up to t. Using well-known mathematical results (1),

|

3 |

where ierfc(z) is the integral of the error function erfc(z). Equation 3 can also be written as

|

4 |

Now, to determine the probability that a bacterium bursts between t′ and t′ + dt′ we use

|

5 |

The average PPB in the lysed bacteria at t is therefore

|

6 |

where the integrand measures PPB for the bacteria that burst between t and t + dt. Using equations 4 and 5,

|

7 |

The average PPB in bacteria which have not lysed by the time t is given by

|

8 |

where the relation in the brackets is the probability that the bacterium did not burst by t and m(t) (equation 2) is the PPB if the bacterium indeed did not lyse. Hence,

|

9 |

and the total PPB is

|

10 |

As mentioned before, the measured quantities are φ(t) and φ2(t).

In order to check these relations, we use the asymptotic forms of the functions appearing here (1). Thus for t >> ν, (ν − t)/ς, which we denote by −u, is negative, and

|

11 |

For u → ∞ we have erfu → 1 and e−u2 → 0; therefore ierfc(−u) → 2u, and m(t) (equation 2) → α(t − ν), as it should (Fig. 1). Hence,

|

12 |

|

where u = (t′ − μ)/β. And after some algebra,

|

13 |

|

For t >> μ, the second term →0 and φ2 → α(μ − ν), as it should (Fig. 1). Similarly,

|

and thus by equation 9, φ1 → 0.

Methods.

The model was tested against results (20) obtained with wild-type T4 phage (5) infecting either E. coli B/r (H266) (36) or E. coli K12 (CR34, thr leu thy drm) (35). Bacteria were cultured with vigorous shaking at 37°C in the following media (36): Luria-Bertani broth containing glucose (LBG) (0.4%; doubling time τ = 23 min); M9 minimal medium supplemented with casein hydrolysate (1%), tryptophan (50 μg/ml), and glucose (GC) (0.4%; τ = 28 to 30 min) or with 0.4% of either glucose (τ = 48 min), glycerol (τ = 70 min), or succinate (τ = 90 min). For the thyA strain of E. coli K12, 5 μg of thymine/ml was added, either with deoxyguanosine (100 μg/ml) or not (35). Upon achieving a steady state (18, 34) at a concentration of 108 cells ml−1, cells were infected with phage (or treated prior to infection as described previously [20]) at a multiplicity of 0.5 (to guarantee a single infection) in the presence of 2 mM KCN (to synchronize the infective process). Phage development was initiated 4 min after phage addition by dilution (10−4) in the same medium to cease further infections and eliminate the bacteriostatic effect of the cyanide. Samples were withdrawn periodically and plated immediately and through chloroform (after evaporation) after appropriate dilutions, with soft agar using E. coli B/r (H266) as indicator. The number of phages was calculated from the number of plaques formed after overnight incubation at 37°C. The raw data (in PFU per milliliter) were transformed to derive the number of phages per infected cell as a function of time (20). The number of PFU obtained in the chloroform series reflects the concentration of all phages, both free and newly matured inside infected bacteria. PFU obtained without chloroform stem from either ripe phages or infected bacteria (infective centers), whether harboring mature phages or not. The number of unadsorbed phages during the eclipse period is considered the background PFU value and is thus subtracted from all raw data.

To obtain different cell sizes under the same growth rate, parameters which are usually correlated (32), three regimes were employed (20). (i) Synchronous glucose-grown cells, obtained by the “baby-machine” (22), were infected either upon collection (“babies”) or after 40 min of growth (almost one mass doubling). The latter, larger synchronous cells indeed supported a slightly faster phage assembly and yielded more phages than the babies. (ii) Thymine limitation of a thyA mutant strain delays cell division due to a slowing down of the chromosome replication rate and thus results in enlarged cells (20, 35). (iii) Low penicillin-G (Pn) concentrations were used to specifically block division without affecting mass growth rate (19). Exposure during about two τs before infection resulted in ca. fourfold-larger cells (data not shown). Superinfection (SI) (6) was employed to delay cell lysis, thus extending the period during which phages continue to develop (20).

The numerical data processing method used here was developed in the last decade. The data contain values of φ and φ2 at t1, t2, …tn. The independent model parameters were sought in such a way as to minimize the error. An elaborate least-squares method was used here because the problem is complicated due to the functional form (an integral for which no analytic expression was found).

The programs used to evaluate the parameters were Minpack (Argonne National Laboratory, 1980) and Simusolv (Dow Chemical Co., 1990). The algorithm used in Minpack is a modified Newton one (27, 28), where an approximation is built for the Hessian of the Newton method. It can be noted that in many cases Minpack helps to find the global minimum, independent of the starting point. In Simusolv, the movement towards the minimum is accomplished by combining two subgroups, Search and GRG (Generalized Reduced Gradient).

In the processing performed here, the simpler program, Minpack, was used to obtain good first approximations. Note that Simusolv can fit several (here, two [φ and φ2]) functions simultaneously and even functions given by their differential equations. The latter was used specifically for φ2.

Results and discussion.

Equations 7, 9, and 10 constitute a system whereby the experimental results can be analyzed. The measurement of total PPB (φ) is performed by applying chloroform. We have found (data not shown) that the addition of chloroform usually causes a reduction of phage ability to form plaques (plating efficiency) by 5 to 20%, resulting in an effective reduction of PPB which does not change with time. Hence, we assumed that the measured PPB is given by ζ · φ, where ζ is the chloroform “destruction parameter.” Thus, altogether six independent parameters were calculated: μ, ν, α, β, ς, and ζ.

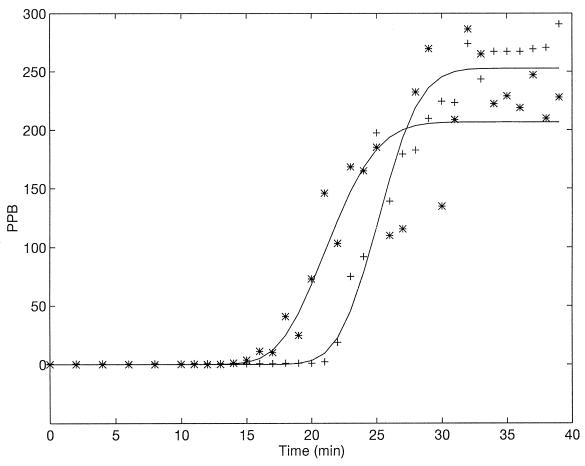

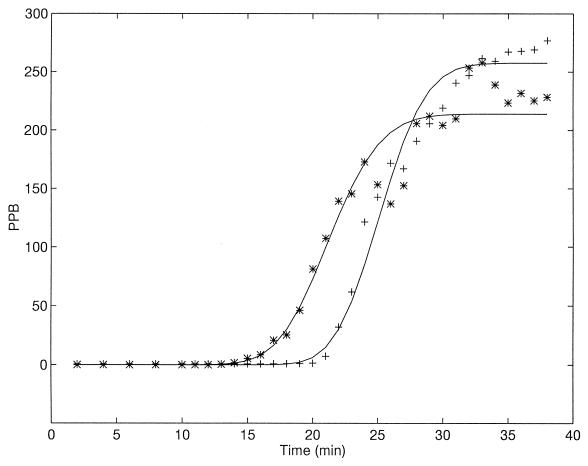

The model was tested against previously published results (20). Results appear in Table 1, together with the burst size [B = α(μ − ν)]. The large variation in derived estimated parameters might have been caused by a small number of data points. To appreciate the problems in analysis, the classical LBG experiment (17) is presented at a higher measured accuracy (minute-by-minute intervals) (Fig. 2). Even under casual observation it is seen that the scatter of points in the chloroform titration results is quite large. Applying the Simusolv procedure as described above yielded the following estimates for the parameters: ν = 18.2 ± 0.1; ς = 2.93 ± 0.1; μ = 24.11 ± 0.1; β = 3.8 ± 0.14; ζ = 0.82 ± 0.02; and B = 250.4 ± 5.2. The r2 values of the fit, shown by the lines in Fig. 2, are however rather poor. For the regular titration, we get 95.2, while for the chloroform titration it is only 90.3. To improve these estimates, we used the moving average method (see, e.g., reference 8), which smooths out the results. The average of the first three points was calculated and taken as the second value, the average of the second to fourth points was used for the third value, etc. The parameters estimated following this averaging process were as follows: ν = 18.3 ± 0.3; ς = 3.37 ± 0.2; μ = 23.6 ± 0.1; β = 4.3 ± 0.15; ζ = 0.84 ± 0.01; and B = 247.1 ± 5.3 (Fig. 3), with an obvious improvement in r2 (regular titration, 97.8; chloroform, 97.4). It is clearly seen that such a smoothing transformation is quite beneficial. In addition, all parameter values other than β remained essentially unchanged, indicating that they were quite robust and reliable.

TABLE 1.

Parameters, at different growth conditions, calculated by the analysis from experimental dataa

| E. coli strain medium/treatment | τ (min) | ν ± ς (min) | μ ± β (min) | ζ | B | α = B/(μ − ν) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/r, LBG/steady statebc | 23 | 18.3 ± 3.4 | 23.6 ± 4.3 | 0.84 | 247.1 | 46.6 |

| B/r, LBG/SI 6 minc | 23 | 22.7 ± 4.0 | 31.9 ± 5.0 | 0.91 | 197.0 | 21.5 |

| B/r, LBG/SI 10 min | 23 | 20.9 ± 4.7 | 27.5 ± 8.2 | 0.88 | 105.6 | 15.8 |

| B/r, LBG/Pn | 23 | 19.2 ± 4.0 | 21.8 ± 5.2 | 0.75 | 195.2 | 77.1 |

| B/r, GC | 28 | 21.0 ± 1.6 | 24.4 ± 4.0 | 0.89 | 143.7 | 42.3 |

| K12-CR34, GC/dG | 30 | 22.3 ± 3.0 | 41.1 ± 10.1 | 0.87 | 169.0 | 9.0 |

| K12-CR34, GC/Thy-limited | 30 | 19.5 ± 4.7 | 30.7 ± 4.1 | 0.92 | 444.1 | 39.7 |

| B/r, glucose | 48 | 27.5 ± 5.0 | 40.9 ± 11.1 | 1.06 | 57.8 | 4.3 |

| B/r, glucose + Pn | 48 | 22.2 ± 3.5 | 33.9 ± 13.3 | 0.86 | 264.3 | 22.2 |

| B/r, small synchronous cellsd | 48 | 23.1 ± 3.5 | 31.1 ± 7.9 | 1.00 | 32.9 | 4.1 |

| B/r, large synchronous cellsd | 48 | 21.9 ± 2.2 | 31.3 ± 5.3 | 0.83 | 59.9 | 6.3 |

| B/r, glycerol | 70 | 42.2 ± 13.4 | 51.5 ± 8.5 | 0.88 | 33.5 | 3.6 |

| B/r, succinatec | 90 | 35.5 ± 7.5 | 40.2 ± 12.0 | 0.83 | 9.5 | 2.0 |

FIG. 2.

Comparison between the model (lines) and results of a classical experiment (17, 20). ∗, samples titered after chloroform treatment. +, naturally released phage.

FIG. 3.

Comparison between the model (lines) and results of the same experiment as in Fig. 2, with a moving average (3-points) technique. (See text.)

Note that the results (Table 1) were obtained with the same six parameters used for both ζ · φ and φ2(t) in each case. The overall agreement is quite good (see the Statistical Analysis section below). The value of ζ that is larger than 1.0 cannot be simply explained; more data points in the plateau region may solve this apparent discrepancy.

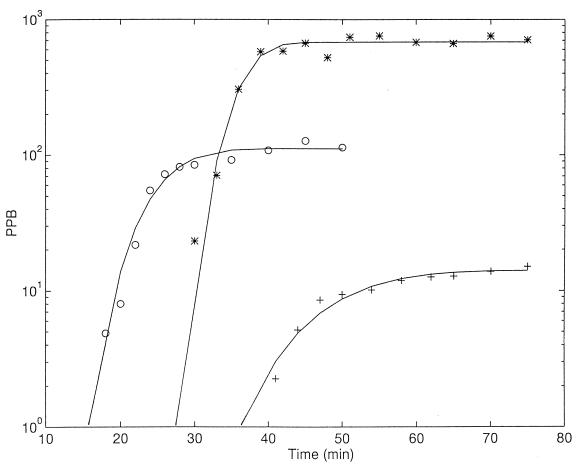

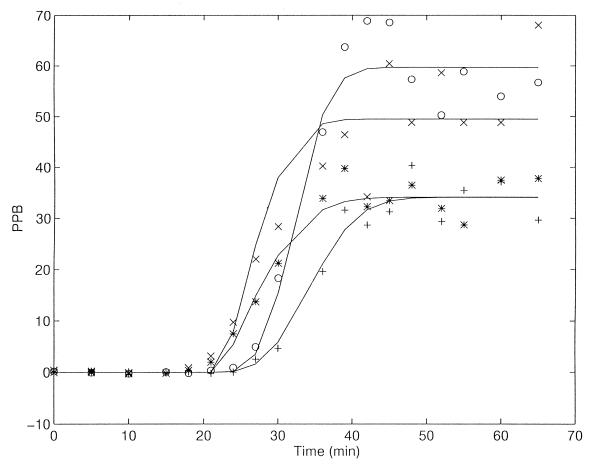

Figure 4 presents three comparisons between the model and actual experiments previously reported (20) (Table 1). The three examples displayed were selected to cover the whole range of burst sizes (between 9 and 720); thus, a semilog presentation was used. (For clarity, the corresponding experiments with chloroform were not included, and the points at early times were deleted.) Correlations between burst size and cell size were observed in early studies with the T-series bacteriophages (see, e.g., references 13 and 21), but it was too early for them to be accounted for by the physiological parameters of E. coli, which emerged a decade later (25, 32).

FIG. 4.

Comparisons between the model (lines) and results of three experiments previously described (20). ○ and +, steady-state cultures (17) grown in LBG and succinate-minimal media, respectively. ∗, cells grown in LBG medium, treated with Pn (75 U/ml) (19) for 60 min and superinfected (6) 6 min after primary infection at a multiplicity of 10.

Figure 5 presents the results of an experiment not previously described, with two samples of a glucose-grown synchronous culture obtained by the “baby machine” (22); one infected upon collection (babies) and the other infected after 40 min of growth (almost one mass doubling). The latter supported a slightly faster phage assembly and yielded more phages (burst size of about 60) than the babies (B = ca. 33). The results are qualitatively consistent with the hypothesis proposed before (20) that the rate of phage synthesis and assembly is proportional to the size of the protein-synthesizing system (9) in the cell upon its infection. This hypothesis will be rigorously tested, and results will be published separately.

FIG. 5.

PPB in synchronous E. coli B/r cells (22) pregrown in glucose-minimal medium, infected (at a multiplicity of 0.5) with bacteriophage T4. + and ∗, eluted “babies”; ○ and ×, “old” cells, after 40 min of growth following elution. + and ○, without chloroform; ∗ and ×, with chloroform.

Statistical analysis.

Since the number of points in each experiment is small (of the order of 40 for the chloroform [φ] and nonchloroform [φ2] parts combined), the statistical significance of our results is not expected to be excellent. As we presently show, however, some parameters have a higher statistical validity than others. We analyze here two cases (the LBG assay from Fig. 3 and the babies from Fig. 5), while other cases show similar statistical attributes. Consider first the percentage of variation explained, which is a measure equivalent to r2 in our case. As mentioned, for the average LBG, an r2 of ca. 97.5% was obtained, while for Fig. 5 the results were, for regular titration, 96.9% and, for chloroform, 95.1%, with an overall fit of 96.0%. A result of ∼96 to 97% is fair and seems higher than would have been expected, since the parameters have to explain both φ and φ2.

The standard deviations (Table 2) were calculated from the diagonal elements of the variance-covariance matrix (see below). The results show (i) the much-improved accuracy of the LBG case due to the increased number of measured points and to the averaging procedure and (ii) better accuracy of μ, ν, and ζ relative to the B and of all these relative to ς and β. For the baby cells, the latter are not really determined. The larger errors in β and ς (and see the discussion below of the correlation matrix) stems from the fact that these parameters are determined by the curvatures of the PPBs at the beginning and the end of their increase. Since the numbers of experimental points at these regions are small, the inability to get exact values of ς and β seems obvious. This observation is enhanced by the correlation matrix of the baby cells (Table 2), where it is seen that the covariance between μ and β is of the order of −0.9.

TABLE 2.

Statistical results of the young “baby” cells (Fig. 5)

| Variable | % Standard deviation | Correlation

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | ν | β | ς | ζ | B | ||

| μ | 8.1 | 1.000 | |||||

| ν | 5.3 | −0.603 | 1.000 | ||||

| β | 25.8 | −0.886 | 0.374 | 1.000 | |||

| ς | 270 (!) | −0.515 | 0.404 | 0.354 | 1.000 | ||

| ζ | 4.4 | 0.006 | 0.136 | −0.133 | −0.040 | 1.000 | |

| B | 6.4 | 0.294 | −0.179 | −0.271 | 0.551 | −0.378 | 1.000 |

To summarize the statistical results, it seems that for the experiments carried out here, the validity of the model is fairly established. The parameters μ, ν, and ζ have a higher statistical significance than B, and much higher significance than α and β. The latter is not even robust. Higher accuracies for both were obtained with an increased number of measured points.

Calculation of correlation matrix.

To calculate the correlation matrix, the following steps are taken (7, 27, 28, 31). (i) The log likelihood function is calculated by

|

where zij is the measured value of the j response of the ith data point, fij is the predicted j response of the ith data point, γ1 is the heteroscedasticity parameter for the jth response, r is the number of measured response variables and nj is the number of data points of the j response.

(ii) The Hessian matrix Hk1k2 is defined as the matrix of the second partial derivatives of Φ with respect to each pair of parameters. Here, the Gauss approximation is used:

|

where θ is the vector of adjustable parameters.

(iii) The variance-covariance matrix V is estimated from the inverse of the Hessian, V = H−1.

(iv) The correlation matrix is given by the normalized variance-covariance matrix of the parameters estimated by

|

with k1,k2 = 1, 2, …, m, where m is the number of adjustable parameters.

Acknowledgments

We thank Itzhak Fishov for constructive discussions.

This work was partially supported by grant 91-00190/2 from the U.S.-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), Jerusalem (to A.Z.), and by a Ben-Gurion Fellowship administered by the Ministry of Science and the Arts (to H.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramovitz M, Stegun I A. Handbook of mathematical functions. New York, N.Y: Dover Publishers Inc.; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams M H. Bacteriophages. New York, N.Y: Interscience Publishers Inc.; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams M H, Wassermann F E. Frequency distribution of phage release in the one-step growth experiment. Virology. 1951;2:96–108. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(56)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ang A, Tang W. Probability concepts in engineering, planning and design. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benzer S. On the topology of the genetic fine structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1959;45:1607–1620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.45.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bode W. Lysis inhibition in Escherichia coli infected with bacteriophage T4. J Virol. 1967;1:948–955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.1.5.948-955.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bord Y. Nonlinear estimation. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Box G E P, Jenkins G M. Time series analysis: forecasting and control, revised ed. San Francisco, Calif: Holden-Day, Inc.; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bremer H, Dennis P P. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell by growth rate. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1553–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown A. A study of lysis in bacteriophage-infected Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1956;71:482–490. doi: 10.1128/jb.71.4.482-490.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairns J, Stent G S, Watson J D, editors. Phage and the origins of molecular biology. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delbrück M. Adsorption of bacteriophage under various physiological conditions of the host. J Gen Physiol. 1940;23:631–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.23.5.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delbrück M. The burst size distribution in the growth of bacterial viruses (bacteriophages) J Bacteriol. 1945;50:131–135. doi: 10.1128/JB.50.2.131-135.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doermann A H. The intracellular growth of bacteriophage. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book. 1948;47:176–182. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eddy S. Introns in the T-even bacteriophages. Ph.D. thesis. Boulder: University of Colorado; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenstark A. Bacteriophage techniques. Methods Virol. 1967;1:449–524. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis E L, Delbrück M. The growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol. 1939;22:365–384. doi: 10.1085/jgp.22.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishov I, Zaritsky A, Grover N B. On microbial states of growth. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:789–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadas H, Einav M, Fishov I, Zaritsky A. Division inhibition capacity of penicillin in Escherichia coli is growth-rate dependent. Microbiology. 1995;141:1081–1083. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadas H, Einav M, Fishov I, Zaritsky A. Bacteriophage T4 development depends on the physiology of its host Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1997;143:179–185. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heden C. Studies of the infection of E. coli B with the bacteriophage T2. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl. 1951;88:42–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helmstetter C E. Methods for studying the microbial division cycle. In: Norris J R, Ribbons D W, editors. Methods in microbiology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 317–364. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingraham J L, Maaløe O, Neidhardt F C. Growth of the bacterial cell. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karam J D. Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kjeldgaard N O, Maaløe O, Schaechter M. The transition between different physiological states during balanced growth of Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1958;19:607–616. doi: 10.1099/00221287-19-3-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch A L. The adaptive responses of Escherichia coli to a feast and famine existence. Adv Microb Physiol. 1971;6:147–217. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levenberg K. A method for the solution of certain problems in least squares. Q Appl Math. 1944;2:164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquardt D W. An algorithm for least squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. SIAM J. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathews C K, Kutter E M, Mosig G, Berget P B, editors. Bacteriophage T4. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reilly P M, Blau G E. The use of statistical methods to build mathematical models of chemical reacting systems. Can J Chem Eng. 1974;52:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaechter M, Maaløe O, Kjeldgaard N O. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced growth of Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1958;19:592–606. doi: 10.1099/00221287-19-3-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stent G S. Molecular biology of bacterial viruses. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman and Co.; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woldringh C L, Huls P G, Vischer N O. Volume growth of daughter and parent cells during the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae a/α as determined by image cytometry. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3174–3181. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3174-3181.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaritsky A, Woldringh C L. Chromosome replication rate and cell shape in Escherichia coli: lack of coupling. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:581–587. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.2.581-587.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaritsky A, Woldringh C L, Mirelman D. Constant peptidoglycan density in the sacculus of Escherichia coli B/r growing at different rates. FEBS Lett. 1979;98:29–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]