Abstract

Sortilin is a post-Golgi trafficking receptor homologous to the yeast vacuolar protein sorting receptor 10 (VPS10). The VPS10 motif on sortilin is a 10-bladed β-propeller structure capable of binding more than 50 proteins, covering a wide range of biological functions including lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, neuronal growth and death, inflammation, and lysosomal degradation. Sortilin has a complex cellular trafficking itinerary, where it functions as a receptor in the trans-Golgi network, endosomes, secretory vesicles, multivesicular bodies, and at the cell surface. In addition, sortilin is associated with hypercholesterolemia, Alzheimer’s disease, prion diseases, Parkinson’s disease, and inflammation syndromes. The 1p13.3 locus containing SORT1, the gene encoding sortilin, carries the strongest association with LDL-C of all loci in human genome-wide association studies. However, the mechanism by which sortilin influences LDL-C is unclear. Here, we review the role sortilin plays in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and describe in detail the large and often contradictory literature on the role of sortilin in the regulation of LDL-C levels.

Supplementary key words: cholesterol/metabolism, cholesterol/trafficking, dyslipidemias, LDL/metabolism, lipoproteins/metabolism, sortilin, SORT1, cellular trafficking, CVD, VPS10

Abbreviations: AAV, adeno-associated virus; ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloprotease; AP, adaptor protein; apoB-100, apolipoprotein B-100; ATF3, cyclic adenosine monophosphate transcription factor 3; CAD, coronary artery disease; CD, chow diet; C/EBPα, CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein alpha; CELSR2, cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 2; CES1, carboxylesterase 1; CI, cation-independent; CRE, C-rich element; DLK1, delta-like noncanonical Notch ligand 1; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; EV, extracellular vesicle; FCR, fractional catabolic rate; GGA, Golgi-localized, γ-adaptin ear-containing ADP-ribosylation factor-binding protein; GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; GSV, GLUT4 storage vesicle; GWAS, genome-wide association study; HF/HC, high-fat/high-cholesterol diet; HFD, high-fat diet; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDLR, LDL receptor; MPR, mannose 6-phosphate receptor; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; NTR1, neurotensin receptor 1; PCBP, poly-rC-binding protein; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3-kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; p75NTR, p75 neurotrophin receptor; proBDNF, pro-brain derived neurotrophic factor; proNGF, pro-nerve growth factor; PSRC1, proline- and serine-rich coiled-coil 1; PVC, prevacuolar endosome compartment; RAP, receptor-associated protein; SMC, smooth muscle cell; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; Tg, transgenic; TGN, trans-Golgi network; UTR, untranslated region; VPS10, vacuolar protein sorting 10; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; WAT, white adipose tissue; WD, Western diet; WT, wild-type

Sortilin (SORT1) was first purified and cloned by affinity chromatography of membrane protein extracts from human brain using receptor-associated protein (RAP) as bait (1). RAP is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/Golgi-localized molecular chaperone involved in the folding and processing of members of the LDL receptor (LDLR) family. By binding to these receptors, RAP prevents premature binding of ligands (2, 3, 4, 5). Sortilin was the first receptor not seemingly related to the LDLR family that was found to bind to RAP. Sortilin instead is homologous with yeast vacuolar protein sorting 10 (VPS10) and the cation-dependent and cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptors (CD-MPR and CI-MPR), which traffic newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes toward the lysosome. Indeed, soon after its discovery, sortilin was shown to transport several resident lysosomal enzymes to the lysosome (6, 7, 8) as well as traffic other proteins for lysosomal degradation (9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

The initial observation that sortilin binds to RAP suggested that it may be involved in lipoprotein trafficking with the cell. Evidence for such a role came from human genetics. Four genome-wide association studies (GWASs), all published in the same year, found several noncoding SNPs in linkage disequilibrium located at an intergenic region on chromosome 1p13.3 that are strongly associated with circulating LDL-C levels (14, 15, 16, 17, 18). Three genes are located at this locus: cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 2 (CELSR2), proline- and serine-rich coiled-coil 1 (PSRC1), and SORT1. Follow-up analysis of the key SNP rs646776 revealed that it impacts the mRNA expression of all three genes in human liver, with the largest regulatory effect on SORT1 mRNA (14).

The GWAS findings led to attempts by many groups to reveal the molecular mechanism behind the association of hepatic SORT1 expression with LDL-C. Studies in cell lines and mouse model systems have led to contradictory results on the role of sortilin in cholesterol metabolism, the most notable regarding the directionality of the effect of sortilin on apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100) trafficking and VLDL secretion in hepatocytes. Studies by Musunuru et al. (19) and Kjolby et al. (20) found that sortilin regulates VLDL secretion from hepatocytes, thereby affecting LDL-C levels, as VLDL is the precursor of LDL. However, the data published by Musunuru et al. (19) showed sortilin to be a negative regulator of VLDL secretion by trafficking the apoB-100-containing lipoprotein toward the lysosome for degradation, whereas Kjolby et al. (20) showed sortilin to be a positive regulator of VLDL secretion by trafficking it toward the plasma membrane. These two articles were the foundation for a multitude of studies from several groups, but the reason for the discrepant results is still unknown.

In addition to its role in CVD, a large body of work has established sortilin as a regulator of neuronal development and maintenance and in the pathogenesis of neurological and mood disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Parkinson’s disease, depression, and anxiety (please see refs. 21, 22, 23, 24 for excellent reviews on this topic).

This review is divided into two major sections. The first revisits fundamental aspects of sortilin’s structure and function, including the tissue distribution and regulation of its expression, the cellular pathways by which it traffics, and its known ligands. The second half reviews and discusses the role that sortilin plays in cardiovascular and metabolic disease, including its involvement in lipoprotein and cholesterol metabolism, and its potential as a drug target. The primary goal of this review is to pull together the more well-recognized (and controversial) ways in which sortilin influences cholesterol metabolism with ones that may have been overshadowed, to better understand the complexity of sortilin’s function.

Structure and function of sortilin

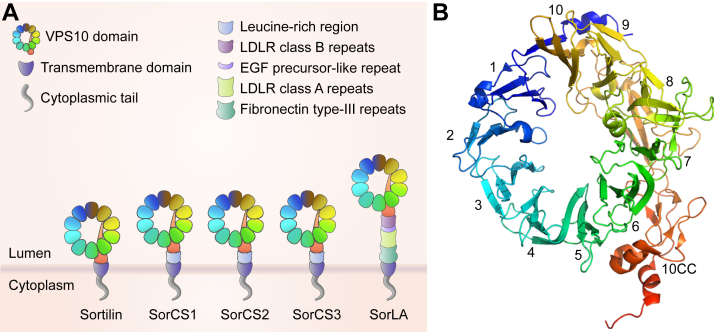

Sortilin (encoded by the SORT1 gene) is a ∼100 kDa type I transmembrane protein and member of the mammalian VPS10 family of post-Golgi trafficking receptors (Fig. 1A) (26, 27). The defining feature of this protein family is the presence of a ∼700 amino acid luminal/extracellular VPS10 domain, which folds into three structural domains: a large N-terminal 10-bladed β-propeller structure and two small C-terminal cysteine-rich domains (together designated the “ten cysteine consensus” or 10CC module) (25) (Fig. 1B). Following the luminal domain, each receptor has a transmembrane domain followed by a short cytoplasmic/intracellular tail of 40–60 amino acids.

Fig. 1.

Sortilin is a member of the VPS10 family. A: Sortilin is a member of the mammalian VPS10 family of receptors along with SorLA, SorCS1, SorCS2, and SorCS3, which have a large luminal/extracellular segment containing a VPS10 domain, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic/intracellular tail. Diagram adapted from Malik and Willnow (21). B: The VPS10 domain folds into a 10-bladed β-propeller and cysteine-rich 10CC module, as determined by Quistgaard et al. (25). Protein Data Bank ID: 3F6K.

Tissue distribution

Sortilin is expressed in a variety of tissues and cell types. In adult humans, it is highly expressed in tissues like the brain, spinal cord, heart, and skeletal muscle, and lowly expressed in the liver, kidney, pancreas, spleen, and small intestine (1). In the adult human brain, it is predominantly expressed in neurons with regional and neuronal cell-type variability (28). In adult C57BL/6 (B6) mice, sortilin is highly expressed in the hypothalamus, brain, and white adipose tissue (WAT) and lowly expressed in liver and skeletal muscle. In several tissues in mice, including lung, kidney, and pancreas, it is highly expressed during development and then downregulated in adulthood (29). There is a high differential expression in the central nervous system during embryonal development in mice (30, 31). Sortilin is also expressed in immune cells (32, 33, 34, 35).

Regulation of sortilin expression

Sortilin (SORT1) expression is tightly regulated at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational levels by many DNA and RNA binding proteins and signaling pathways in a cell- and tissue-specific manner.

Transcriptional regulation

At the DNA level, sortilin expression is regulated in a tissue-specific manner by the transcription factors CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα), cyclic adenosine monophosphate transcription factor 3 (ATF3), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, and by DNA methylation. Human GWAS have identified SNPs near the SORT1 gene, located in a noncoding region between the two neighboring genes CELSR2 and PSRC1, which affect the expression of SORT1, CELSR2, and PSRC1 in a tissue-specific manner (14, 19, 36, 37). The association of these SNPs with the expression of multiple genes suggests that variation at this locus may have a regional effect on gene expression. Musunuru et al. (19) discovered that the minor allele of rs12740374 increases the expression of SORT1 by creating a binding site for the C/EBP transcription factors in the liver. Furthermore, forced expression of C/EBPα specifically induced SORT1 expression in hepatocytes but not embryonic cells or adipocytes.

Obesity in humans is associated with downregulation of sortilin at the mRNA and protein levels in subcutaneous WAT (38) and liver (39). Similarly, sortilin mRNA and protein expression is downregulated in the liver, gonadal WAT, and skeletal muscle in response to high-fat diet-induced obesity and genetic obesity (ob/ob) in B6 mice (38, 40), making them a good model system for studying the regulation of sortilin expression in obesity. Overnutrition results in hyperactivation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and activation of the ER stress response. Ai et al. (40) demonstrated that ATF3, which is rapidly induced by ER stress downstream of phospho-eukaryotic initiation factor 2a, binds to a site in the proximal Sort1 promoter and acts as a transcriptional repressor in liver and adipose tissue. Obesity induces inflammation and a proinflammatory environment, which activates Toll-like receptors and subsequent nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells activation and ATF3 transcription. Multiple cytokines that are key inflammatory mediators regulate the expression of Sort1 mRNA. TNFα controls Sort1 mRNA expression in adipocytes and skeletal muscle partly through a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent mechanism (38). IFN-γ controls hepatic Sort1 levels through the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 transcription factor, which is activated and bound to the Sort1 gene upon IFN-γ treatment, reducing the expression of Sort1 (41). In addition, in a mouse model that is deficient in regulatory T cells, hepatic Sort1 mRNA expression is significantly reduced, likely through the coincident dramatic increase in hepatic ATF3 in these mice (42).

Post-transcriptional regulation

Sortilin expression is regulated by a variety of mechanisms at the RNA level. A network of RNA-binding proteins, including TAR-DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L (hnRNP L), polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB), and hnRNP A1/A2, is involved in the proper splicing of Sort1 mRNA (43, 44, 45, 46). Poly-rC-binding proteins 1 and 2 (PCBP1 and PCBP2) stabilize Sort1 mRNA by recognizing the C-rich element (CRE) in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (47, 48). The nucleotide-binding ability of PCBP1 and PCBP2 is impaired by zinc ions, and alterations in intracellular zinc affect Sort1 expression. In differentiated PC12 cells, C2C12 myotubes, and rat skeletal muscles, Sort1 expression is positively regulated by glucose through a post-transcriptional mechanism involving 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase and mTORC1, possibly through enhancement of protein translation (49, 50). In addition, the microRNAs miR-182 and miR378a-3p have been shown to bind to the 3′ UTR of Sort1 mRNA, decreasing Sort1 mRNA levels and sortilin protein (51, 52).

Post-translational regulation

At the protein level, sortilin expression is regulated by palmitoylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic tail. Palmitoylation of cysteine 783 in the tail of sortilin stabilizes sortilin protein (53). Nonpalmitoylated sortilin is ubiquitinated by the “neural precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated 4” E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (NEDD4) and internalized into the lysosomal compartment via the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport pathway for degradation (54). Sortilin is post-translationally downregulated in the liver and gonadal WAT in obesity (38, 39, 40, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59). Saturated fatty acids downregulate hepatic sortilin protein through activation of ERK, which phosphorylates serine 793 in the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin. This phosphorylation event is followed by ubiquitination of lysine 818 and lysosomal degradation (39, 56). Oxidized LDL activates ERK signaling to downregulate sortilin expression in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (60). In C2C12 myotubes, saturated fatty acids induce downregulation of sortilin via mechanisms involving protein kinase C (PKC) (61).

Sortilin protein is a target of insulin signaling through the insulin/phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B (insulin/PI3K/AKT) signaling cascade, whereby insulin increases sortilin protein expression. In hepatocytes, casein kinase II is activated by insulin signaling and phosphorylates serine 825 in the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin, inducing sortilin expression. Inhibition of PI3K signaling or prevention of sortilin phosphorylation induces the lysosomal degradation of sortilin (58). Hepatic sortilin is also a target of leptin signaling, potentially through the action of leptin to stimulate insulin receptor substrate-mediated PI3K activity (62). Interestingly, the insulin/PI3K/AKT signaling cascade also regulates sortilin protein in adipocytes through an unknown mechanism but not through phosphorylation of serine 825 (57).

There is great interest in the significance of the downregulation of sortilin in WAT and liver in obesity. The role of insulin and inflammatory cytokine signaling in regulating liver, adipose, and skeletal muscle sortilin stability suggests that inflammation and impaired insulin signaling (insulin resistance) contribute to reduced sortilin protein in these tissues in obesity.

Cellular trafficking itinerary of sortilin

Sortilin is a post-Golgi trafficking receptor

Sortilin was the first VPS10 domain-containing mammalian protein to be discovered. The domain was first identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the sorting receptor protein known as VPS10. Primarily localized in the late Golgi compartment, VPS10 interacts with soluble vacuolar hydrolases, including carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) and proteinase A (PrA), and traffics them to a prevacuolar endosome compartment (PVC) (63, 64, 65). At the PVC, VPS10 releases its ligand and recycles back to the Golgi apparatus for additional rounds of sorting. The hydrolase continues to the vacuole. VPS10 was recognized as being analogous to the CD-MPR and the CI-MPR in mammalian cells. Newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes acquire a mannose 6-phosphate moiety as they pass through the cis-Golgi. MPRs then bind these enzymes in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and traffic them to an endosomal compartment. The lysosomal enzymes dissociate from the MPRs in the endosome, where the enzymes continue to the lysosome and the MPRs recycle back to the TGN. The majority of the MPRs traffic between the TGN and endosomes, but some traffic to the cell surface to internalize extracellular lysosomal enzymes (66, 67). The similarity of sortilin to VPS10 and the MPRs prompted initial studies that investigated the involvement of sortilin in targeting lysosomal enzymes to the lysosome in mammalian cells. As predicted, sortilin was found to traffic between the TGN and endosomes (1, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73), mediating the lysosomal targeting of prosaposin (PSAP) (6, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80), GM2 ganglioside activator protein (GM2AP) (6, 75, 76), acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) (7, 80, 81, 82), and cathepsins D and H (8).

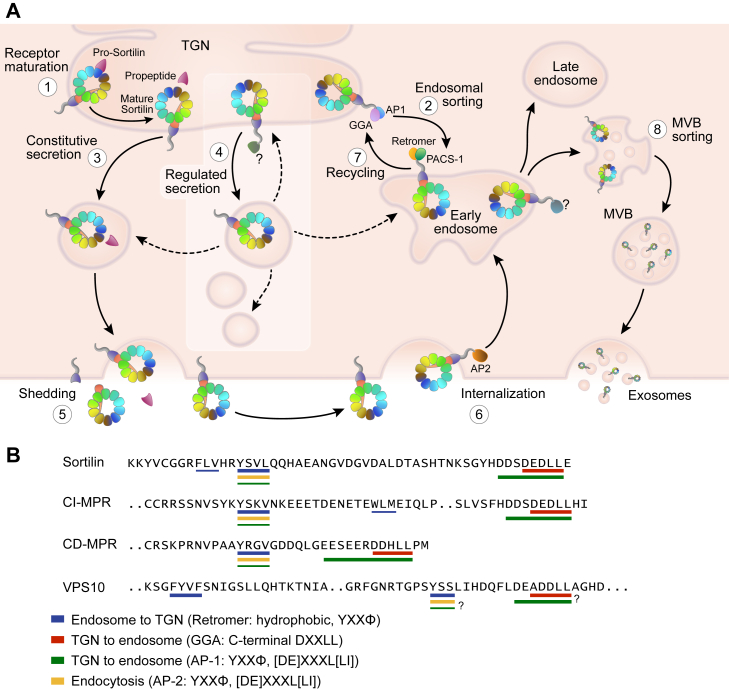

Subsequent studies continue to elucidate a much more complex trafficking itinerary of sortilin. In addition to shuttling between the TGN and endosomes, sortilin can also traffic through the constitutive secretory pathway (34), sort into the regulated secretory pathway in specialized cell types (83, 84, 85), function as an endocytosis receptor at the cell surface (11, 68, 86, 87, 88), and aid in exosome formation and release (89, 90, 91, 92) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Cellular trafficking of sortilin. A: 1) Sortilin is converted from its proform to its mature form in the TGN by furin cleavage of its propeptide. Mature sortilin can exit the TGN through three different routes, depending on the cell type, 2) through anterograde sorting to endosomes, which requires binding of APs GGA and/or AP-1 to its cytoplasmic tail, 3) through the constitutive secretory pathway, or 4) through the regulated secretory pathway in specialized cell types. Sortilin does not localize to mature secretory granules, and it is unclear how it exits immature secretory granules, indicated by dotted arrows. When sortilin reaches the cell surface, it can be 5) shed from the surface, or 6) endocytosed, which requires AP-2 binding. The majority of sortilin at the plasma membrane is rapidly endocytosed. 7) Sortilin is returned from endosomes to the TGN by retrograde sorting, which requires interaction with the retromer complex and PACS-1. 8) Sortilin is also involved in sorting cargo to multivesicular bodies and can itself be secreted from the cell in exosomes. Highlighted box indicates a process that occur in specialized cell types. Diagram adapted from Malik and Willnow et al. (21). B: Important sorting motifs located in the cytoplasmic tails of sortilin, CI-MPR, CD-MPR, and yeast VPS10 include a tyrosine-based motif (YXXΦ) and an acidic cluster dileucine motif (DXXLL) that overlaps with an acidic cluster motif ([DE]XXXL[LI]), which are important for AP binding. Thickness of the underline indicates relative potency of the motif for the transport and AP binding indicated. MVB, multivesicular body; PACS-1, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 1.

Sorting motifs and adaptor proteins

Like VPS10 and the MPRs, the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin harbors sorting motifs required for the binding of adaptor proteins (APs), Golgi-localized, γ-adaptin ear-containing ADP-ribosylation factor-binding proteins (GGAs), retromer, and other proteins that regulate the trafficking of sortilin (Fig. 2B). Transport of sortilin from the TGN to endosomes is regulated by the binding of GGA1, GGA2, and AP-1 to an acidic cluster dileucine motif (DXXLL, where X is any amino acid) and overlapping acidic cluster motif ([DE]XXXL[LI]) at the far C-terminus of the sortilin tail (68, 69, 71, 93, 94, 95). The dileucine is the most critical part of the motif (68), and it is essential that it be positioned at the C-terminus, as adding extra amino acids to the C-terminus of sortilin (such as a tag) has been shown to inhibit GGA binding (94). AP-1 binding to a tyrosine-based motif in the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin (YXXΦ, where X is any amino acid and Φ is a bulky hydrophobic residue) may also be involved in the TGN-to-endosome transport. At the endosome, the tyrosine-based motif is a potent signal for retromer binding and required for its efficient retrieval back to the TGN for further rounds of sorting (70, 71, 72, 73, 96). There is evidence that a nearby hydrophobic motif, FLV in sortilin and WLM in CI-MPR, may be part of a bipartite retromer binding site (97, 98). This site has similarity to the FYVF site in VPS10 that is required for its retrieval from the PVC in yeast (99). Ceroid-lipofuscinosis neuronal protein 5 (CLN5) has been shown to be required for retromer binding to sortilin at early endosomes (100), and AP-5, a relatively uncharacterized AP, can interact with sortilin and function as a backup to the retromer in retrieving sortilin from the endosome (101). In addition, Rab7b is important for the formation of transport carriers that move sortilin between the TGN and endosomes (102). Calnuc regulates the activity of Rab7 in this process and is also involved in the recruitment of retromer to endosomes (103).

Post-translational modifications of the sorting motifs regulate AP binding, and therefore the trafficking and localization of sortilin. Palmitoylation of cysteine 783 in the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin (nine amino acids N-terminal to the YXXΦ motif) by the aspartic acid-histidine-histidine-cysteine-containing palmitoyltransferase 15 (DHHC-15) is required for efficient retromer binding and retrieval of sortilin from endosomes (53). Palmitoylation is not required for AP-1 binding, suggesting that this modification is required for exit of sortilin from the endosomes but not from the TGN. Mutation of the palmitoylation site results in the trapping of sortilin in endosomes. Unable to recycle, it is subject to ubiquitination and degradation.

The acidic cluster motif in the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin contains a serine residue (serine 825) that can be phosphorylated by casein kinase II (68). Investigation of whether this acidic cluster or the phosphorylation status of its serine residue affects binding of APs and trafficking of sortilin has generated complicated results (68, 69). There is speculation that the hydrophilic nature of the serine residue, but not its phosphorylation status, is important, as has been shown for the sorting of the CI-MPR (104), or that its phosphorylation status is important for binding of GGA2 but not GGA1 (93). Phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 1 (PACS-1) binds phosphorylated acidic clusters, mediating retrograde Golgi-endosome transport (105) and may play a role in the retrieval of sortilin (69, 106). The YXXΦ motif (YSVL) also contains a serine residue, one that can be phosphorylated by Rac-p21-activated kinases 1–3 (107). The phosphorylation of this serine residue alters the affinity for AP-1 binding and changes the intracellular localization of sortilin, supporting prior evidence that the YXXΦ motif is involved in TGN-to-endosome transport through AP-1 binding, in addition to being a potent internalization signal through AP-2 binding at the plasma membrane.

The molecules involved in directing sortilin into the secretory pathways are not as well elucidated. Entry into the regulated secretory pathway requires interaction with still unidentified APs (108). Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) may be involved (109). Although it is not an AP itself, it may aid in AP recruitment to the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin. Proteins do not require specific interaction with APs to exit the TGN into the constitutive secretory pathway. It is unknown how sortilin’s entry into this pathway is regulated; however, the “sorting for entry” model of Golgi sorting indicates that proteins enter the constitutive secretory pathway by default if not directly or indirectly bound by APs for regulated secretory pathway or endosome targeting (108). Therefore, sortilin’s entry into the constitutive secretory pathway may be indirectly regulated by post-translational modifications of its cytoplasmic tail that affect binding of APs and entry into these other pathways.

Sortilin molecules that reach the cell surface can have up to three different fates, depending on the cell type. The majority of sortilin receptors at the plasma membrane are rapidly endocytosed. Others become a substrate for a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10) (10, 110, 111), which cleaves the luminal domain from the transmembrane and cytosolic domains, shedding it from the cell in a soluble form. ADAM17/TNFα-converting enzyme may also be involved in cleaving sortilin (112), but this is controversial and may be cell type specific (10). After the luminal domain is cleaved, the C-terminal fragment left behind in the cell membrane can become a substrate for γ-secretase, potentially aiding in the degradation of the fragment (113). The majority of the cleavage by ADAM10 occurs at the cell surface; however, soluble sortilin has also been detected intracellularly from cleavage by ADAM10 in the secretory pathway, leading to its constitutive secretion from the cell (10). In certain cell types such as neurons, sortilin that reaches the plasma membrane can hetero-oligomerize with the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), allowing it to bind pro-nerve growth factor (proNGF) and transmit a signal for apoptosis (see refs. 21, 22, 23, 24 for reviews).

In the steady state, sortilin is predominantly localized to the TGN and endosomes, with a small amount localized (∼10%) at the cell surface (1, 68, 69, 72, 86). At the cell surface, the tyrosine-based motif is a potent signal for internalization by AP-2 (68). The acidic cluster dileucine, to which AP-2 can bind, also plays a role in sortilin internalization, but to a much lesser extent (68). Mutation of the tyrosine-based motif results in the accumulation of sortilin at the plasma membrane (9, 68), indicating that the steady-state localization of sortilin can be deceiving and that a large number of the receptors reach the cell surface but are rapidly internalized.

Ligands and binding sites

Sortilin is a multiligand receptor, trafficking and binding a number of soluble and membrane proteins of varying size that have diverse and often unrelated functions. Over 50 different proteins have been identified to bind sortilin and/or have altered trafficking or signaling upon manipulation of sortilin expression or function (Table 1). Neurotensin was the first ligand identified and is the only one that has been co-crystalized with sortilin, revealing its binding in a small pocket inside the tunnel of the 10-bladed β-propeller of sortilin’s VPS10 domain (25). Competitive binding measurements have demonstrated that other ligands, including proNGF, pro-brain derived neurotrophic factor (proBDNF), and progranulin (PRGN) likely bind in a distinct but overlapping region with that of neurotensin (25, 165, 166), revealing that at least part of the binding site of proneurotrophins is located outside the tunnel of the β-propeller (166).

Table 1.

Sortilin ligands

| Pathway | Ligand | References |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid related | Apolipoprotein A-V (apoA-V) | (87) |

| Apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100) | (9, 20, 114, 115, 116) | |

| Apolipoprotein E (apoE) | (117) | |

| Apolipoprotein J/clusterin (apoJ) | (118) | |

| ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) | (12) | |

| Delta like non-canonical Notch ligand 1 (DLK1) | (95) | |

| Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) | (11) | |

| Carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) | (13) | |

| Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) | (119) | |

| Neurotrophin related | p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) | (120, 121, 122) |

| pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (proBDNF) | (10, 35, 45, 84, 109, 120, 123, 124) | |

| pro-nerve growth factor (proNGF) | (121, 125, 126, 127, 128) | |

| Proneurotrophin-3 (proNT-3) | (129) | |

| Tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TRKA) | (130) | |

| Tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TRKB) | (130) | |

| Tropomyosin receptor kinase C (TRKC) | (130) | |

| Neurotensin related | Neurotensin | (25, 86, 131, 132) |

| Neurotensin receptor 1 (NTR1) | (133, 134) | |

| Neurotensin receptor 2 (NTR2) | (135) | |

| Amyloid precursor protein (APP) related | Amyloid-precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2) | (136) |

| Amyloid precursor protein (APP) | (137, 138) | |

| β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) | (139) | |

| Cytokine related | Cardiolipin-like cytokine/cytokine-like factor-1 (CLC/CLF-1) | (140) |

| Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) | (140) | |

| Glycoprotein 130/leukemia inhibitory factor receptor β (gp130/LIFRβ) | (140) | |

| Interferon-α (IFN-α) | (48) | |

| Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) | (33, 34, 48) | |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | (33, 48) | |

| Interleukin-10 (IL-10) | (48) | |

| Interleukin-12 (IL-12) | (48) | |

| Interleukin-17A (IL-17A) | (48) | |

| Neuropoietin | (140) | |

| Lysosomal proteins | Acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) | (7, 81) |

| Cathepsin D | (8) | |

| Cathepsin H | (8) | |

| Prosaposin (PSAP) | (6, 75, 78, 79, 80) | |

| Other | Activin | (141) |

| Adiponectin | (142) | |

| α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A) | (88) | |

| α-synuclein | (143) | |

| Bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) | (141) | |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) | (144, 145) | |

| Gelsolin | (146) | |

| Glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) storage vesicles | (83, 85, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152) | |

| GM2 ganglioside activator pseudogene (GM2AP) | (6, 75) | |

| Golgi phosphoprotein 4 (GPP130) | (153) | |

| Na+/Cl− cotransporter (NCC) | (154) | |

| Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3) | (155) | |

| Prion (PrPC and PrPSc) | (156) | |

| Progranulin (PGRN) | (43, 157, 158) | |

| Prorenin receptor (PRR) | (159) | |

| Receptor-associated protein (RAP) | (1) | |

| Sonic hedgehog (SHH) | (160) | |

| Thyroglobulin | (161, 162) | |

| TWIK-related potassium channel 1 (TREK-1) | (163, 164) |

A comprehensive list of known ligands or receptor binding partners of sortilin.

Regulation of ligand binding and trafficking

Sortilin is synthesized as a proprotein and converted to its mature form in the late Golgi by furin cleavage of its propeptide. The propeptide binds inside the tunnel of the β-propeller with high affinity and inhibits binding of some of sortilin’s ligands in the early secretory pathway, including neurotensin (25, 166, 167) and RAP (167). Interestingly, binding of the propeptide to sortilin does not block the binding of all ligands, including proNGF and proBDNF (166), supporting the view that sortilin has multiple binding sites for ligands. Recently, a small molecule that specifically binds to “binding site 2” (the site where neurotensin does not bind) was shown to augment binding of neurotensin to sortilin binding site 1, suggesting that site 2 is an allosteric regulator of site 1 binding (168).

Since sortilin can bind to multiple ligands and traffic them through several possible pathways in the same cell, various questions emerge: Upon binding of a particular ligand, what determines which of the multiple trafficking pathways are pursued? What is the link between specific ligand binding and recruitment of the appropriate APs to transport a ligand to its correct destination? The answers to these questions are largely unknown. However, recent work by Trabjerg et al. (165) using hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry found that different ligands exhibit distinct conformational impacts on sortilin. These specific ligand binding-induced conformational changes extend into the membrane-proximal domain of sortilin, and potentially across the membrane, possibly affecting AP binding. This hints at a mechanism by which sortilin mediates diverse ligand-dependent trafficking. Another possibility is that ligands destined for different pathways localize to different regions of the Golgi, prior to their interaction with sorting receptors. Recently, the Bonifacino group provided direct evidence for this additional level of protein sorting in the Golgi, where there is early segregation of different sets of proteins that are destined for different pathways, well before their export in transport carriers (169). This creates regions of the Golgi that generate carriers destined for the constitutive secretory pathway that are distinct from regions that generate carriers destined for the endolysosomal system, for example. Therefore, it is possible that sortilin localized to the section of the Golgi that buds transport carriers destined for the endolysosomal system only has access to proteins that have been presorted for this pathway. Generation of these carriers and their targeting to the endolysosomal pathway would require AP binding to receptors. Similarly, sortilin localized to the section of the Golgi that generates transport carriers destined for the constitutive secretory pathway would only have access to proteins that have been presorted for this pathway. However, these carriers would be generated and targeted independently of APs.

Interestingly, in some cases, sortilin has been shown to traffic the same ligand to different pathways depending on the cellular context. For example, under normal conditions, sortilin targets proBDNF to the regulated secretory pathway in neurons. However, under conditions where the cell has excess proBDNF, sortilin targets this excess to the endolysosomal system for degradation (10, 84). In hepatocytes, sortilin may traffic apoB-100 toward the secretory pathway for secretion or toward the lysosome for degradation, depending on the metabolic context (114, 115, 170). The mechanism underlying these switches is unknown.

Ligand binding is also regulated by dimerization of sortilin at low pH. During sortilin’s transport between the TGN, cell surface, endosomes, and other vesicular compartments, it is exposed to dramatic fluctuations in pH. Ligands tend to show high affinity for sortilin at neutral pH but have a reduced or a complete loss of affinity at acidic pH (1, 119, 137, 167, 171), consistent with release of ligands in secretory granules or late endosomes. Recent reports by several groups have revealed that low pH triggers sortilin to undergo a conformational change and dimerize, causing the collapse of the binding site in the tunnel of the β-propeller and release of the ligand (92, 172, 173, 174) (Fig. 3). Sortilin is predominantly a monomer at neutral pH and predominantly a dimer at acidic pH. It dimerizes through the top face of its β-propeller, opposite the 10CC module. Hydrophobic loops that protrude from the blades of the β-propeller at the dimer interface are important for dimer formation. In addition, disruption and formation of Coulombic repulsions between charged residues (173), salt bridges (173), and disulfide bonds (92) are important for the conformational changes and monomer-dimer shift that occurs upon pH change. Only structures of the sortilin luminal domain were determined, but the structure of the soluble sortilin dimer reveals that the C termini of the luminal domains are in close proximity to each other, indicating that the 2-fold axis that describes the dimer is oriented perpendicular to the cell surface (173). The ligand binding site located in the tunnel of the β-propeller undergoes a conformational change in the monomer-dimer transition that triggers release of ligand from sortilin (173). Januliene et al. (174) proposed the appealing idea that the various cytosolic APs may have different affinities for the cytoplasmic tail of sortilin when in the monomeric or dimeric state. Therefore, dimerization may be a mechanism by which sortilin traffics specific ligands toward different pathways in the cell.

Fig. 3.

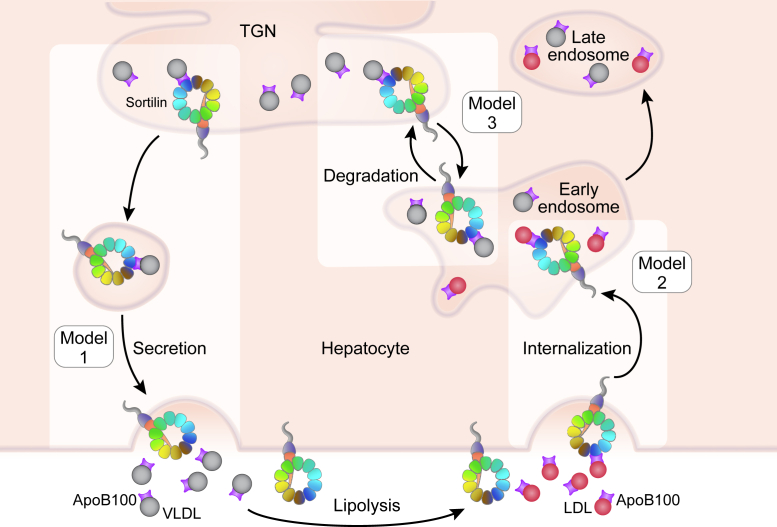

Models of sortilin function in lipoprotein metabolism in the liver. Model 1: Sortilin facilitates the secretion of VLDL, increasing circulating VLDL and LDL through lipolysis. Model 2: Sortilin promotes LDL internalization, decreasing circulating LDL. Model 3: Sortilin traffics VLDL from the TGN toward the endolysosomal system for degradation, decreasing circulating VLDL and LDL. Diagram adapted from Schmidt and Willnow (175). LDL, red shaded; VLDL, gray shaded.

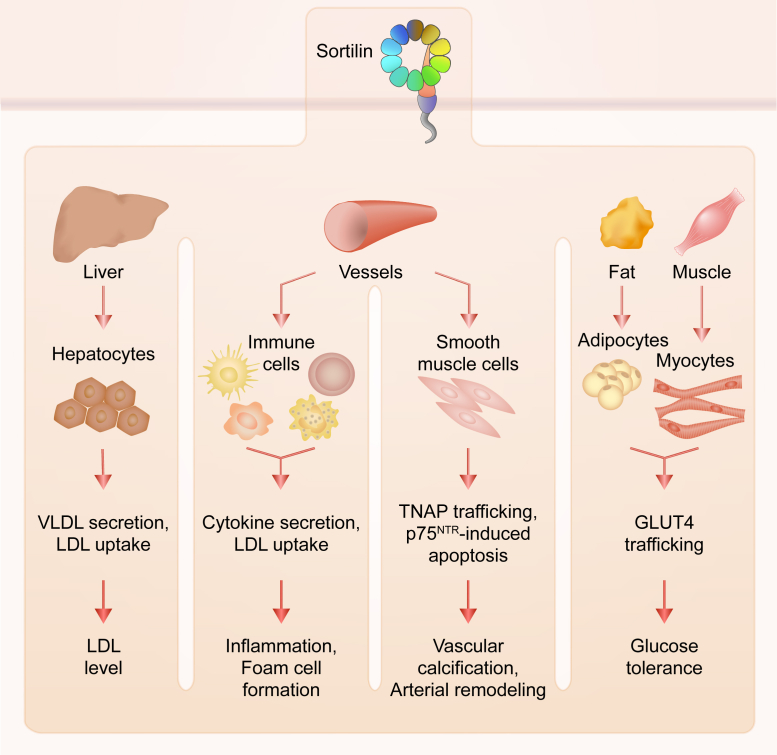

The role of sortilin in cardiovascular and metabolic disease

Sortilin is implicated in many aspects of health and disease through its function in the cellular trafficking of over 50 different molecules, including apolipoproteins, cytokines, proneurotrophins, and enzymes, and also being a coreceptor for neurotrophin signaling (Table 2). Sortilin is involved in many facets of cardiovascular and metabolic disease pathogenesis, including atherosclerosis, lipoprotein metabolism, vascular calcification, obesity, insulin resistance, and glucose homeostasis. This section reviews the extensive evidence linking sortilin to these pathways and diseases and discusses its potential as a drug target.

Table 2.

Pleiotropic role of sortilin in disease

| Pathway or disease | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular and metabolic disorders | ||

| Lipoprotein metabolism | Hepatic VLDL trafficking | (9, 19, 20, 39, 40, 114, 115, 116) |

| Hepatic LDL clearance | (9, 37, 176) | |

| Hepatic PCSK9 secretion | (119) | |

| LPL trafficking | (11) | |

| ApoA-V trafficking | (87) | |

| Altered plasma cholesterol, unknown mechanism | (55, 177, 178) | |

| Atherosclerosis | Lipoprotein metabolism (see above) | |

| Macrophage proinflammatory cytokine trafficking | (33) | |

| Macrophage LDL uptake and foam cell formation | (32) | |

| Macrophage ABCA1 trafficking | (12) | |

| Smooth muscle cell apoptosis via proNT signaling | (179) | |

| Osteoblastic differentiation and vascular calcification | (51, 90, 180, 181) | |

| Obesity, insulin resistance, and glucose homeostasis | Adipocyte and myocyte GLUT4 vesicle trafficking | (61, 83, 148, 150, 152) |

| Adipocyte differentiation | (95, 182) | |

| Intestinal lipid absorption via neurotensin binding | (178, 183) | |

| Altered diet-induced obesity or insulin resistance, unknown mechanism | (55, 59, 178, 184) | |

| Neurological and neurodegenerative disease | ||

| Neuronal development and maintenance | Binds proNGF and p75NTR, forming apoptotic signaling complex in neurons | (121, 127) |

| proBDNF signaling and trafficking | (10, 35, 45, 84, 109, 120) | |

| TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC trafficking | (129) | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | APP and BACE1 trafficking | (137, 138, 139) |

| Neuronal apoE and apoJ metabolism | (117, 118) | |

| Tau prion trafficking | (185) | |

| proNT signaling and trafficking | (186, 187, 188, 189) | |

| Aβ toxicity mediated by p75NTR-sortilin complex | (190) | |

| Prion diseases | PrPc and PrPSc trafficking | (156) |

| Frontotemporal dementia | Clearance of PGRN | (43, 157, 191, 192) |

| Parkinson’s disease | p75NTR-sortilin assembly in substantia nigra neurons | (193) |

| α-synuclein trafficking | (143) | |

| Depression and anxiety | proNT signaling and trafficking | (194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199) |

| TREK-1 trafficking | (163, 164) | |

| Other | ||

| Cancer | Neurotensin, proNT, and PGRN signaling and trafficking | (134, 144, 145, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217) |

| EGFR trafficking | (144, 145) | |

| Immune processes and inflammation | Proinflammatory cytokine and receptor trafficking | (33, 34, 48, 140) |

| Microglia activation and migration via neurotensin binding | (218, 219, 220, 221) | |

List of diseases and pathways that sortilin has been implicated in and the mechanism(s) by which it is involved in the pathology.

SNPs controlling hepatic SORT1 expression are associated with LDL-C in human GWAS

Human GWAS have identified several SNPs (rs599834, rs646776, rs629301, rs660240, rs602633, and rs12740374) in a haplotype block in the region of the gene cluster CELSR2-PSRC1-SORT1 on chromosome 1 at the 1p13.3 locus that strongly associate with LDL-C levels in several cohorts and ethnic populations (14, 15, 16, 17, 36, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229). The minor alleles of these SNPs are protective, associated with a 5–8 mg/dl decrease in LDL-C. The effect size of the association between the locus and LDL-C levels is larger in younger populations and males (230, 231, 232) and is independent of obesity (182). In addition, rs646776 displayed a major impact on statin efficacy to reduce LDL-C levels in an elderly population (233). Of particular relevance, the minor allele of rs646776 has been shown to be most highly associated with levels of small LDL (19). In humans, there are several distinct subclasses of LDLs that range in size and density (234). The small dense LDLs are associated with risk of atherosclerotic CVD, being more atherogenic than their larger and more buoyant counterparts (235, 236, 237, 238, 239). In recent years, an increasing number of studies demonstrating that small dense LDLs have a greater propensity to cause atherosclerosis have emerged. This has propelled researchers to further investigate the mechanism behind the atherogenicity of small dense LDLs in order to develop new therapies to prevent cardiovascular events and to establish a clinically effective method to accurately measure circulating small dense LDL levels (240, 241, 242, 243).

The six LDL-C-associated SNPs at the 1p13.3 locus cluster in a noncoding region that is 6.1 kb in length, spanning the 3′ UTR of CELSR2, the intergenic region, and the 3′ UTR of PSRC1, and downstream of SORT1. These SNPs seem to regulate the expression of SORT1, PSRC1, and CELSR2 in a tissue-specific manner. Schadt et al. (36) found that the minor allele of rs599839 is associated with increased hepatic SORT1 and CELSR2 expression and decreased PSRC1 expression. Studies by Kathiresan et al. (14) and Musunuru et al. (19) showed that the minor allele of rs646776 is associated with increased hepatic expression of all three genes with the increase in SORT1 expression being the largest. Kathiresan et al. found that rs646776 explained 86, 58, and 58% of the interindividual variability in SORT1, CELSR2, and PSRC1 expression levels, respectively. In analyses conditioning on either the CELSR2 or PSRC1 transcript levels, rs646776 remained associated with SORT1 expression. Conversely, when conditioning on SORT1 expression, rs646776 was weakly or not associated with PSRC1 or CELSR2 expression. In addition, Musunuru et al. found that the minor allele of rs12740374 is associated with increased hepatic SORT1 and PSRC1 expression and not associated with the expression of CELSR2 in the liver. By analyzing haplotype maps from humans of varying ethnicity, Musunuru et al. identified rs12740374 as the causal SNP in the haplotype block and determined that the minor allele generates a C/EBP transcription factor binding site, increasing SORT1 expression. There was no association between the SNPs and SORT1 expression found in studies of WAT (19), whole blood (244), monocytes (245), or blood vessels (246, 247). These analyses suggested that the regulatory mechanism underlying the association of the SNPs at the 1p13.3 locus with LDL-C was sortilin mediated and liver specific and predicted an inverse relationship between hepatic SORT1 expression and circulating LDL-C level.

The controversial role of sortilin in hepatic lipoprotein metabolism

With SORT1 being nominated as the gene responsible for the association of the 1p13.3 locus with LDL-C, functional studies by several groups sought to validate this finding and determine the underlying mechanism. The prevailing conclusion is that sortilin plays a direct role in trafficking apoB-100 containing lipoproteins in hepatocytes. However, the directionality of sortilin’s effects is highly disputed.

Sortilin promotes cellular LDL uptake, but is this dependent on the LDLR?

The first evidence linking sortilin function with LDL-C levels showed an effect of sortilin overexpression on cellular LDL uptake. Linsel-Nitschke et al. (37) overexpressed SORT1 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and found increased internalization of radiolabeled LDL particles. Subsequent studies in HeLa cells (176) and the human hepatocyte cell line HuH7 (9) produced the same result. Conversely, in the HepG2 human hepatocyte (159), A431 human epidermoid carcinoma (159), and HeLa (248) cell lines, silencing of SORT1 reduced LDL uptake. Importantly, the studies in HeLa, HepG2, and A431 also looked for an effect of Sort1 manipulation on the total and/or cell surface abundance of LDLR protein. SORT1 overexpression in HeLa cells had no effect on the amount of LDLR at the cell surface (176). The studies measuring only total cellular abundance of LDLR protein produced conflicting results (136, 159, 248). Measurement of total hepatic LDLR protein abundance in Sort1−/− mice has also produced conflicting results (119, 136).

To directly assess whether the LDLR is required for the effect of sortilin on LDL uptake, Strong et al. (9) measured the clearance of LDL from the circulation in chow diet (CD)-fed female mice with either global genetic deletion or liver-specific overexpression of Sort1 in both wild-type (WT) and Ldlr−/− backgrounds. In a WT background, knockout of Sort1 resulted in a lower fractional catabolic rate (FCR) of radiolabeled LDL, and overexpression caused an increase in the LDL FCR. On an Ldlr−/− mouse background, Sort1 overexpression also resulted in increased LDL clearance. The authors state that Sort1−/−;Ldlr−/− mice, compared with Ldlr−/− mice, have a 50% lower LDL FCR. However, the curves showing the percent LDL remaining in the circulation over time that were used to calculate the FCRs appear nearly identical (panels E and F in Fig. 4 in ref. 9). Therefore, from this in vivo work in B6 mice, it appears that the LDLR is required for sortilin to promote LDL clearance at a normal physiological level of sortilin, but when expressed at a supraphysiological level, sortilin may promote the clearance of LDL independently of the LDLR, possibly by directly binding and internalizing LDL itself. Interestingly, an article by Patel et al. (32) found that bone marrow-derived macrophages isolated from Sort1−/− mice internalized 40% less LDL in both WT and Ldlr−/− backgrounds, suggesting that a requirement for the LDLR for sortilin to promote LDL uptake may be dependent on cell type. Contradictory to the findings by Strong et al., a study by Kjolby et al. found no difference in the uptake of radiolabeled LDL into primary hepatocytes isolated from WT and Sort1−/− mice (20). However, primary hepatocytes begin losing mature function within the first few hours of traditional in vitro culture (249, 250, 251), possibly explaining the lack of an effect on loss of Sort1 on LDL uptake in these experiments.

Any experiments involving overexpression of sortilin need to be interpreted cautiously because both overexpression and C-terminal tagging can cause sortilin to mislocalize and become unphysiologically abundant at the cell surface. The predominant localization of sortilin to the TGN and endosomes is dependent upon interaction of APs, GGAs, and retromer with tyrosine- and dileucine-based sorting motifs in its C-terminus. C-terminal tagging of sortilin inhibits GGA binding (94), and mutation of the tyrosine and dileucine sorting motifs in sortilin’s cytoplasmic tail results in its accumulation at the plasma membrane (9, 68). Furthermore, overexpression of sorting receptors containing functional tyrosine- and dileucine-based sorting signals results in their accumulation at the cell surface because of the saturation of APs (252). This is discussed in more detail in a later section.

The majority of in vitro and in vivo work supports a role for sortilin in promoting LDL clearance by hepatocytes, which would work to lower LDL-C and is therefore consistent with the directionality predicted by the human genetics. The mechanism by which sortilin does this, however, seems to depend on whether it is expressed at a normal level or a supraphysiological level.

Sortilin regulates hepatic apoB-100 secretion, but in what direction?

Since circulating LDL levels are determined by both its rate of clearance and rate of production, several groups have also investigated a role for sortilin in the secretion of VLDL from the liver.

Musunuru et al. (19) were the first to publish on the effect of hepatic Sort1 expression on apoB-100 secretion. They treated four different C57BL/6 CD-fed mouse models with an adeno-associated virus 8 vector encoding the murine Sort1 gene driven by the liver-specific thyroxine binding globulin promoter (AAV8-TBG), resulting in liver-specific overexpression of Sort1. In all four backgrounds tested (Apobec−/−; APOB Tg, Apobec−/−; Ldlr−/−, Apobec−/−; APOB Tg; Ldlr+/−, and Apobec−/−; APOB Tg; Ldlr−/−), overexpression of Sort1 resulted in a significant reduction in plasma total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-C by 23–76% depending on the background. Conversely, knockdown of Sort1 with liver-targeted Sort1 siRNA in the same mouse models resulted in a significant increase in plasma TC and LDL-C by 16–125% depending on the background. Similarly, they observed a 50% increase in plasma TC and LDL-C in CD-fed Sort1−/− compared with WT mice. These findings were concordant with directionality predicted by the human genetics. To determine the mechanism behind this effect, the group assessed the rate of in vivo VLDL secretion by injecting mice with detergent to inhibit the lipolysis of VLDL and subsequently measuring the accumulation of circulating triglyceride (TG) and VLDL (via NMR) over time. Sort1 overexpression in Apobec−/−; APOB Tg decreased the rate of VLDL accumulation by 57%. Furthermore, overexpression of Sort1 in primary hepatocytes isolated from the Apobec−/−; APOB Tg; Ldlr+/− or Apobec−/−; Ldlr−/− mice overexpressing Sort1 significantly decreased the secretion of newly synthesized apoB-100. Consistently, secretion of apoB-100 was significantly increased in hepatocytes isolated from Apobec−/−; APOB Tg; Ldlr+/− mice treated with Sort1 siRNA. From these data, the authors proposed a model in which sortilin negatively regulates hepatic export of VLDL, the precursor of LDL, thereby decreasing the production of LDL from VLDL.

Nearly simultaneously, Kjolby et al. (20) published data contradicting that of Musunuru et al. In this study, Sort1−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background and fed a Western diet (WD; 43% kcal from fat, 0.15% cholesterol) for 6 weeks had a 20% reduction in plasma TC and a 65% decrease in LDL-C (20). On an Ldlr−/− background, Sort1−/− reduced plasma TC by 30% and plasma LDL-C by 25%. Using adenoviral gene transfer, they overexpressed Sort1 in the liver of WT mice and found a 42% increase in plasma TC. Similarly, Sort1 overexpression on the Ldlr−/− background increased plasma TC by 33% and increased LDL-C, restoring them to the levels of Ldlr−/− mice. Using a similar detergent-based method as Musunuru et al., they assessed VLDL secretion in WD-fed WT and Sort1−/− mice but found that Sort1−/− resulted in slower accumulation of circulating TG and total apoB-100 levels. Consistently, in primary hepatocytes isolated from the Sort1−/− mice, newly synthesized apoB-100 secretion was decreased by 54%. Using coimmunoprecipitation and surface plasma resonance, they found that sortilin can directly bind apoB-100. From these data, they concluded that sortilin acts as a positive regulator of VLDL export in the liver, increasing VLDL secretion (20).

Shortly thereafter, the Rader group published a second article that presented further evidence of sortilin acting as a negative regulator of VLDL export (9). In agreement with the group’s initial finding, they found that overexpression of Sort1 via AAV8-TBG in CD-fed female WT and Ldlr−/− mice reduced newly synthesized VLDL apoB-100 secretion into the circulation by 30% and 50%, respectively. To test if the endolysosomal trafficking of sortilin was required for the reduction in apoB-100 secretion, they conducted similar experiments with two different sortilin mutants that cannot traffic to the lysosome: Sort.LAYA, in which critical residues in the dileucine and tyrosine sorting motifs are mutated to alanine, and Sort.stop, which lacks the entire transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail. Overexpression of either mutant in Ldlr−/− mice failed to reduce apoB-100 secretion. Furthermore, overexpression of Sort1 in hepatocytes isolated from Apobec−/−; APOB Tg; Ldlr+/− mice resulted in decreased apoB-100 secretion, and this effect was completely inhibited by treatment with the endolysosomal inhibitor E64d. In contrast to their group’s original finding, however, their data showed that Sort1−/− in an Apobec−/−; APOB Tg mouse background had a 60% decrease in VLDL apoB-100 secretion. Therefore, in this article, both overexpression and knockout of Sort1 resulted in decreased VLDL apoB-100 secretion. In addition, both Strong et al. and a third article from this group by Patel et al. (32) reported normal plasma TC and LDL-C levels in Sort1−/− mice on an Apobec−/−; APOB Tg background, in contrast to the increased levels observed by Musunuru et al. upon siRNA knockdown of Sort1 in the same mice.

The story became increasingly confusing and complex as reports from several other groups emerged. Some agreed with the findings of Kjolby et al., showing a positive relationship between Sort1 level and plasma cholesterol and/or hepatic apoB-100 secretion (12, 55, 178, 184), whereas others observed a negative relationship, in agreement with Musunuru et al. (39, 40, 116, 177) (Table 3). Others found Sort1−/− to have no effect on plasma cholesterol (33, 90, 136) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Paradoxical role of sortilin in lipoprotein metabolism

| Model system | Diet | Sex | Method | TC/LDL-C | apoB secretion | LDL uptake | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulation of Sort1 | |||||||

| HEK293 cells | NA | NA | Plasmid | NA | ND | ↑ | Linsel-Nitschke et al. (37) |

| HeLa T-Rex cells | NA | NA | Plasmid | NA | ND | ↑ | Tveten et al. (176) |

| HuH7 cells | NA | NA | LV | NA | ↓ | ↑ | Strong et al. (9) |

| McA cells | NA | NA | Plasmid | NA | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| hAPOB McA cells | NA | NA | Plasmid | NA | ↓ | ND | Amengual et al. (116) |

| hAPOB McA cells | NA | NA | Plasmid | NA | ↓ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| HepG2 cells | NA | NA | AV | NA | ↓ | ND | Bi et al. (39) |

| WT mouse heps | CD | ♂ | AV | NA | ↓ | ND | Bi et al. (39) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg mouse heps | CD | NR | AAV8-TBG | NA | ↓ | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Ldlr+/− mouse heps | CD | ♀ | AAV8-TBG | NA | ↓ | ND | Strong et al. (9) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Ldlr+/− mouse heps | CD | NR | AAV8-TBG | NA | ↓ | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| WT mice | CD | ♀ | AAV8-TBG | ND | ↓ | ↑ | Strong et al. (9) |

| WT mice | CD | ♂ | AAV8-TBG | ↓ | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| WT mice | CD | ♂ | AV | ↓ | ND | ND | Bi et al. (39) |

| WT mice | CD | NR | AAV8 | ND | — | ND | Ai et al. (40) |

| WT mice | WD | NR | AV | ↑ | ND | ND | Kjolby et al. (20) |

| WT mice | HFD | ♂ | AAV8-TBG | ↓ | ↓ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| WT mice | HFD | NR | AAV8 | ND | ↓ | ND | Ai et al. (40) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg mice | CD | NR | AAV8-TBG | ↓ | ↓ | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Apobec−/−;Ldlr−/− mice | CD | NR | AAV8-TBG | ↓ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Ldlr−/−mice | CD | NR | AAV8-TBG | ↓ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Ldlr+/− mice | CD | NR | AAV8-TBG | ↓ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Ldlr−/− mice | CD | ♀ | AAV8-TBG | ND | ↓ | ↑ | Strong et al. (9) |

| Ldlr−/− mice | WD | ♂ | LV | ↑ | ND | ND | Lv et al. (12) |

| Ldlr−/− mice | WD | NR | AV | ↑ | ND | ND | Kjolby et al. (20) |

| ob/ob mice | CD | ♂ | AV | ↓ | ND | ND | Bi et al. (39) |

| ob/ob mice | WD | NR | AAV8 | ND | ↓ | ND | Ai et al. (40) |

| Downregulation of Sort1 | |||||||

| HeLa T-Rex cells | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | ND | ↓ | Tveten et al. (176) |

| HepG2 cells | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | ND | ↓ | Lu et al. (159) |

| HepG2 cells | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| HepG2 cells + FA | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | ↑ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| A431 cells | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | ND | ↓ | Lu et al. (159) |

| HUES 1 and 9 HLCs | NA | NA | TALEN KO | NA | ↑ | ND | Ding et al. (177) |

| McA cells | NA | NA | shRNA | NA | — | ND | Sparks et al. (115) |

| McA cells | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| McA cells - serum-starved | NA | NA | shRNA | NA | ↑ | ND | Sparks et al. (115) |

| McA cells + FA, Cer, or Tun | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | ↑ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| hAPOB McA cells | NA | NA | siRNA | NA | ↑ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Sort1−/− mouse heps | WD | NR | Global KO | NA | ↓ | — | Kjolby et al. (20) |

| Sort1−/− mouse heps | CD | ♂ | Global KO | NA | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Sort1−/− mouse heps + FA | CD | ♂ | Global KO | NA | ↑ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Ldlr+/− mouse heps | CD | NR | siRNA | NA | ↑ | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♀ | Global KO | ND | ND | ↓ | Strong et al. (9) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♂ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Goettsch et al. (90) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♂ | Global KO | — | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | NR | Global KO | ↑ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | NR | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Butkinaree et al. (136) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♂ | Hep KO | — | ND | ND | Chen et al. (55) |

| Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♂ | Hep KO | — | — | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Sort1−/− mice | WD | NR | Global KO | ↓ | ↓ | ND | Kjolby et al. (20) |

| Sort1−/− mice | WD | ♂ | Hep KO | ↓ | ND | ND | Chen et al. (55) |

| Sort1−/− mice | HFD | ♂ | Global KO | ↓ | ND | ND | Rabinowich et al. (184) |

| Sort1−/− mice | HFD | ♂ | Global KO | ↑ | ↑ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Sort1−/− mice + Tun | CD | ♂ | Global KO | ND | ↑ | ND | Conlon et al. (170) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♀ | Global KO | — | ↓ | ND | Strong et al. (9) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Sort1−/− mice | WD | ♂ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Patel et al. (32) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg mice | CD | NR | siRNA | ↑ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Apobec−/−; APOB Tg; Ldlr−/− mice | CD | NR | siRNA | ↑ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Apobec−/−;APOB Tg;Ldlr+/− mice | CD | NR | siRNA | ↑ | ND | ND | Musunuru et al. (19) |

| Ldlr−/−;Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♀ | Global KO | ↓ | ND | — | Strong et al. (9) |

| Ldlr−/−;Sort1−/− mice | CD | ♀ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Hagita et al. (178) |

| Ldlr−/−;Sort1−/− mice | WD | NR | Global KO | ↓ | ND | ND | Kjolby et al. (20) |

| Ldlr−/−;Sort1−/− mice | HF/HC | ♀ | Global KO | ↓ | ND | ND | Hagita et al. (178) |

| Ldlr−/−;Sort1−/− mice | HF/HC | ♀ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Goettsch et al. (90) |

| Ldlr−/−;Sort1−/− mice | HF/HC | ♂ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Goettsch et al. (90) |

| Apoe−/−;Sort1−/− mice | WD | ♀ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Mortensen et al. (33) |

| Apoe−/−;Sort1−/− mice | WD | ♂ | Global KO | — | ND | ND | Mortensen et al. (33) |

| L1B6Ldlr−/−; Sort1−/− mice | WD | ♂ | siRNA | ND | ↑ | ND | Ai et al. (40) |

| ob/ob mice + PBA | CD | NR | siRNA | ND | ↑ | ND | Ai et al. (40) |

AAV8-TBG; adeno-associated virus 8 with thyroxine-binding globulin promoter; AV, adenovirus; Cer, ceramide; heps, primary hepatocytes; HLC, hepatocyte-like cell; HUES, human embryonic stem cell line; LV, lentivirus; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; NR, not reported; PBA, 4-phenyl butyric acid; Tun, tunicamycin; —, no difference.

Summary of published results on the effect of Sort1 manipulation on lipoprotein metabolism.

Figure 3 diagrams three models that have been proposed to explain the genetic link between sortilin and LDL-C: trafficking VLDL for secretion, trafficking VLDL for degradation, and facilitating LDL clearance. An important review by Dube et al. pointed out that while a role for sortilin in VLDL secretion from hepatocytes is plausible, data from human GWAS show a negative association of SORT1 expression with plasma TC and LDL-C but not with plasma TGs or VLDL (253). Therefore, models that propose control of VLDL secretion as the primary mechanism by which sortilin function influences LDL-C cannot be directly reconciled by the human GWAS.

Intriguingly, a new study by the Rader group published earlier this year indicated that sortilin may also regulate the size of lipoprotein particles secreted from the liver (170). Their main goal was to investigate the effect of sortilin on apoB-100 secretion under basal versus metabolic stress conditions, as discussed further, but observed a disconnect between the effect of sortilin on TG versus total apoB-100 secretion in some of their experiments. For example, overexpression of Sort1 in CD-fed mice resulted in decreased TG secretion but no difference in the secretion of newly synthesized total apoB-100 in the plasma. To follow up on this surprising observation, they performed sucrose density gradient separation of lipoproteins on plasma pooled from mice of the same genotype taken 2 h after the injection of detergent and 35S-Met/Cys. A Western blot of apoB-100 in 11 fractions over a density range of 1.005–1.21 g/ml revealed decreased apoB-100 in the less dense “VLDL” fractions and increased apoB-100 in the higher density “LDL” fractions in the Sort1-overexpressing mice. This is consistent with the observed decrease in TG secretion with no difference in apoB-100 secretion because each apoB-100-containing lipoprotein contains one molecule of apoB-100, but the less dense lipoproteins contain more TG. The group found the opposite effect in primary hepatocytes isolated from Sort1−/− mice: increased TG secretion, no difference in the secretion of total apoB-100, but increased secretion of lower density “VLDL” and decreased secretion of the higher density “LDL.” An indication that sortilin regulates the size of the particles secreted by the liver certainly encourages a more robust study in the future. Interestingly, an earlier article by Ai et al. observed increased secretion of apoB-100 without an increase in TG secretion in Li-Tsc1KO mice, a genetic model of increased hepatic mTORC1 activity by liver-specific knockout of the upstream mTOR inhibitor Tsc1, which have 50% less hepatic sortilin mRNA and protein compared with control mice (40). Of the several other mouse models with altered hepatic sortilin expression that they studied (ob/ob, diet-induced obesity, L1B6Ldlr−/−), this was the only one that had differential effects on TG and apoB-100 secretion, leading the authors to speculate that the increased secretion of relatively TG-deficient particles was due to the modulation of other pathways involving mTORC1. However, the prospective finding by Conlon et al. may support a role of sortilin in this phenomenon.

Recently, sortilin has been indicated as a regulator of Lipoprotein(a) (Lp (a)) secretion; however, this was only demonstrated when sortilin was overexpressed (254). Lp(a) is a variant of LDL that has a second protein, apo(a), covalently attached to apoB-100 (255). A considerable amount of research has been dedicated to determining how Lp(a) is regulated because of the strong relationship between Lp(a) concentration in the plasma and vascular disease (256). Clark et al. (254) found that overexpression of sortilin in HepG2 cells that stably express apo(a) increased the secretion of Lp(a) and that this was dependent upon sortilin’s binding to apoB-100. However, knockdown of endogenous sortilin by siRNA had no effect on Lp(a) secretion. The authors propose that this may be due to the modest ∼60% knockdown of sortilin that was achieved by the siRNA. It is also possible that sortilin only has this effect on Lp(a) secretion when expressed at a supraphysiological level or that the experiments were performed in HepG2 cells, which required overexpression of apo(a) because this cell line does not express apo(a) endogenously (257). Further studies are needed to establish the contexts in which sortilin affects Lp(a) secretion.

Possible explanations for the discrepant results on sortilin’s role in hepatic lipoprotein metabolism

Because of the very strong association between hepatic Sort1 expression level and LDL-C in human GWAS, determining the reason why different functional studies have come to opposing conclusions about the directionality of the effect of sortilin and LDL is of great interest. Because sortilin function is sensitive to many factors, including, but not limited to, its level of overexpression, C-terminal tagging, and the metabolic environment, differences in experimental conditions that influence one or more of these factors are likely to alter the way sortilin traffics apoB-100-containing lipoproteins. There were numerous experimental conditions employed among the studies, and no two studies performed the same measurement under the same experimental conditions (based on the methodological details that were reported). Thorough comparison of the conditions used in each study failed to nominate any one variable to account for the contradictory results between and within research groups.

Issues with overexpression and tagging of sortilin

The level of overexpression and the presence of C-terminal tags greatly affect the function of sortilin. In the steady state, sortilin is predominantly localized to the TGN and endosomes, with only a small portion (∼10%) localizing to the cell surface (1, 68, 69, 72, 86). Entry of sortilin into the endolysosomal system from the TGN, recycling back to the TGN, and internalization from the cell surface all require APs (68, 71, 73). High levels of overexpression like that achieved by the constructs used in the majority of the studies can saturate APs like GGA and alter the distribution and localization of sorting receptors like sortilin toward increased levels at the cell surface (252). This has also been shown to occur upon overexpression of VPS10, the yeast homolog of sortilin (65, 99). Strong et al. (258) proposed that overexpression of sortilin may also saturate ADAM10, disturbing the balance of full-length sortilin and soluble sortilin abundances in the cell, contributing to the inconsistent results. The soluble form of sortilin, generated by ADAM10 at the plasma membrane and also to some extent in the secretory pathway, binds ligands with similar affinity to full-length sortilin (110, 112, 120). Since soluble sortilin retains the ability to bind ligand, it has been postulated that it could function as a “decoy receptor” in the secretory pathway and extracellularly. Regulating sortilin cleavage by ADAM10 can be a way for the cell to control the amount of ligand available to bind to full-length sortilin or other receptors that share the same ligand. C-terminal tagging of sortilin can also alter its distribution and localization. GGA proteins are critical to the proper trafficking of sortilin in endosomes (68, 69, 93, 94), and placement of a tag at the C-terminus of sortilin interferes with the binding to GGA (94).

Differences in the tissue specificity of the methods used to manipulate Sort1 levels

Another factor that could contribute to the discrepant findings is the level by which different methods of overexpression, knockdown, and knockout of Sort1 occurred in nonhepatic tissues in experiments conducted by various research teams. Sortilin has lipid-related functions in cells other than hepatocytes, such as its role in mediating the internalization and degradation of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) (11), intestinal cholesterol absorption (178), intestinal fatty acid absorption via its function as a neurotensin receptor (183), as discussed in later sections.

A recent article by Chen et al. was the first to publish results from a tissue-specific Sort1−/− mouse. The study found that hepatocyte-specific knockout of sortilin (by breeding Sort1flox/flox mice to mice expressing Cre driven by the hepatocyte-specific albumin promoter) results in a 22% decrease in plasma TC in mice fed a WD for 12 weeks. This suggests that the results showing a lowering of plasma TC or LDL-C upon knockdown or knockout of Sort1 obtained by Kjolby et al., Hagita et al., Goettsch et al., and Strong et al. are due to altering the abundance of sortilin in hepatocytes. However, this is the opposite directionality of the prediction from human GWAS, namely that decreased hepatic Sort1 levels would result in increased LDL-C (14, 19, 36).

Use of different Sort1−/− mouse models

Three different global Sort1−/− mice were used between the studies: one that was generated by replacing a segment between exon 2 and intron 3 of the Sort1 gene with a neomycin-resistance cassette (9, 19, 32, 136)), another that was made by replacing of a fragment from exon 14 and the subsequent intron with Neo (20, 33, 119, 184), and a third that was made by targeted deletion of a fragment of exon 14 (90, 178). The latter two models likely express a truncated protein consisting of part of the luminal domain that may fold and be able to bind ligand.

Differences in metabolic context—genetic background, age, sex, and diet of mice, and cell culture conditions

Since the expression and trafficking of sortilin is affected by levels of insulin resistance (40, 57, 58), ER stress (40, 58), saturated fatty acids (39, 56, 61), glucose (50), oxidized LDL (12), and inflammatory cytokines (41, 56), it is likely that metabolic context influences the directionality by which sortilin affects LDL-C. Many of the differences in experimental conditions used in the studies can greatly influence these parameters, including the genetic background of the mice being studied (e.g., WT, Apobec−/−, APOB Tg, Ldlr−/−, Apoe−/−, ob/ob), the diets used (e.g., CD, WD, high-fat/high-cholesterol (HF/HC) diet, high-fat diet (HFD)), the age at which the mice were started on experimental diet, the length of diet feeding, the sex of the mice, and the culture conditions in studies using cell lines. Some studies used only female mice, whereas others used only males, with very few studying both. In many cases, the sex of the mice used was not reported. C57BL/6 mice were used in all the studies, but report of the specific substrain (e.g., the phenotypically different and widely studied J and N lines) was often lacking. In a case where these details were provided, mice of a mixed C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N background were used (55).

Studies by the Sparks group using the McArdle RH7777 (McA) rat hepatocyte cell line have clearly demonstrated how cell culture conditions that affect insulin sensitivity alter the role of sortilin in VLDL secretion. Insulin suppresses the secretion of VLDL and apoB-100 by favoring the presecretory degradation of apoB-100 (259, 260, 261, 262). Under serum-enriched conditions, McA cells are insulin resistant, and under serum-starved conditions, they are insulin sensitive. Under baseline conditions in the insulin-sensitive state, sortilin facilitates VLDL secretion. Upon addition of insulin in this state, sortilin shifts to facilitating the insulin-dependent presecretory degradation of VLDL, potentially through a mechanism involving binding of the insulin-signaling molecule phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate to the luminal domain of sortilin (155). However, in the insulin-resistant state of the cells (serum-enriched conditions), VLDL secretion and degradation is regulated independently of sortilin (114, 115).

There were three groups that conducted experiments on both chow- and either WD- or HFD-fed mice in the same study: Ai et al. (40), Chen et al. (55), Conlon et al. (170). All three found that WD or HFD feeding was required for manipulation of Sort1 expression to have an effect on apoB-100 secretion and/or plasma TC. Both Conlon et al. and Ai et al. presented data showing that this unmasking of a role for sortilin in apoB-100 secretion under HFD-fed conditions was due to the increased level of ER stress in the livers of the diet-fed mice (40, 170).

Many reviews have endorsed the idea that sortilin acts through distinct mechanisms that can raise and lower LDL-C (trafficking VLDL for secretion, trafficking VLDL for degradation, and facilitating LDL clearance) and that the balance of these actions in a specific metabolic environment determines its contribution to circulating levels of LDL-C (175, 253, 258, 263, 264, 265).

SORT1 may not be the only important gene

Even though SORT1 has been the primary functional candidate gene at the 1p13.3 locus for the association with LDL-C in GWAS, its neighboring genes, CELSR2 and PSRC1, are also regulated by the causal SNPs, making it possible that multiple genes at the locus act together to regulate LDL levels (14, 19, 36, 266). In fact, a study published earlier this year that analyzed published GWAS and quantitative trait locus studies using Mendelian randomization methods found that higher expression levels of SORT1, PSRC1, and CELSR2 in liver were all individually significantly associated with lower LDL-C and coronary artery disease (CAD) risk (267). Similarly, in another article published this year, analysis of allelic ratios built from tissue-specific RNA sequencing data available through the human Genotype-Tissue Expression Project (GTEx) indicated that the multiple SNPs at the 1p13.3 locus likely regulate more than one gene to account for the predicted disease risk (268).

The Musunuru group has investigated developing alternative models to those that have been used to study the role of sortilin in hepatic lipoprotein metabolism and began by returning to the original human GWAS observation. Unfortunately, the minor allele of rs12740374 does not create a C/EBPα binding site in mice as it does in humans. The group explored the potential usefulness of three different model systems: 1) a collection of primary human hepatocytes with varied rs12740374 genotypes, 2) a population cohort of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells, and 3) a mouse model where the human 1p13.3 locus containing the rs12740374 minor allele has been incorporated into the genome via bacterial artificial chromosome transgenesis (269). Initial experiments indicated that primary human hepatocytes and bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice could be better alternatives to the current model systems for studying how the common human 1p13.3 SNP affects lipoprotein metabolism.

Potential roles for sortilin in cholesterol metabolism outside of hepatic lipoprotein trafficking

Although much of the studies investigating the role of sortilin in cholesterol metabolism revolves around its trafficking of lipoproteins in the hepatocyte, its involvement in intestinal cholesterol and fatty acid absorption and bile acid synthesis may also affect circulating cholesterol levels.

Intestinal cholesterol and fatty acid absorption

There is evidence that sortilin plays a role in intestinal cholesterol absorption, which contributes to plasma cholesterol levels. Female Sort1−/−Ldlr−/− mice fed an HF/HC diet have elevated fecal TC, suggesting impaired intestinal cholesterol absorption (178). Sortilin deficiency decreases intestinal mRNA levels of Niemann-Pick C1-like intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (Npc1l1), an intestinal cholesterol transporter, liver X receptor (LXR), a key transcriptional lipid metabolism regulator, and of several of their regulators. It is unknown how sortilin deficiency affects the mRNA levels of these genes, but because sortilin is a trafficking receptor, it is likely that this effect on transcription is indirect. In addition, it is difficult to determine whether these changes are a cause of the reduced fecal TC in the mice or a result of it. Even though it was not evaluated in this study, the possibility that sortilin directly participates in intestinal cholesterol absorption by trafficking proteins involved in this process cannot be ruled out. In addition, one of sortilin’s most well-studied ligands, neurotensin, has been shown to play a role in HFD-induced obesity by increasing fat absorption in the intestine (183). It is possible that sortilin is involved in this process by regulating neurotensin levels.

Bile acid synthesis

Sortilin may regulate cholesterol metabolism by playing a role in bile acid synthesis. Bile acids are synthesized from free cholesterol, stored in the gall bladder, and released into the intestine to facilitate digestion and absorption of lipids in the small intestine as well as to regulate cholesterol homeostasis (270, 271). Cholestasis occurs when flow of bile out of the liver is impaired as a result of decreased secretion from the hepatocytes or obstruction of bile flow (272, 273) and can lead to liver inflammation, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis (274, 275, 276). In the initial stages of cholestatic injury, a ductular reaction occurs, characterized by the proliferation of reactive bile ducts, myofibroblast activation, and an influx of inflammatory cells (274, 277, 278).