Abstract

The properties of the cysteines in the pBR322-encoded tetracycline resistance protein have been examined. Cysteines are important but not essential for tetracycline transport activity. None of the cysteines reacted with biotin maleimide, suggesting that they are shielded from the aqueous phase or reside in a negatively charged local environment.

The tetracycline resistance protein (TetA) encoded by the pBR322 cloning vector (3) is a member of a family of related tetracycline efflux proteins that are prevalent in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (2, 15, 25). Six classes of TetA transporters have been identified, all of which catalyze H+-driven antiport of a divalent metal ion-tetracycline complex out of the cytoplasm (28). The class C protein encoded by pBR322 is 78% identical to the class A protein encoded by Tn1721 (2, 26) and is 44% identical to the class B transporter encoded by transposon Tn10 (23). Due to their high degree of sequence identity, it is likely that the three-dimensional structures of the proteins are very similar. TetA proteins also may be structurally similar to other members of the major facilitator superfamily to which they belong (24).

The membrane topologies of the Tn10- and pBR322-encoded proteins have been investigated by proteolysis (5, 8, 21, 22), chemical labeling (5, 10, 12, 13), and gene fusion (1) methods. Based on these studies and hydropathy analysis (23), the proteins were predicted to have 12 α-helical transmembrane (TM) segments and to have N and C termini located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). The five cytoplasmic loops of the proteins are exposed to water at the surface of the inner membrane and can be digested in inverted membrane vesicles by several proteases (5, 8, 21, 22). In contrast, the six periplasmic loops appear not to project outside the membrane surface because they are refractory to protease digestion. However, it has been possible to label cysteines introduced into each periplasmic loop by reaction with N-[14C]ethylmaleimide (12). Cysteine scanning mutagenesis and N-ethylmaleimide labeling also have been applied to determine the membrane boundaries of TM3 and TM9 in the Tn10-encoded protein (10, 13).

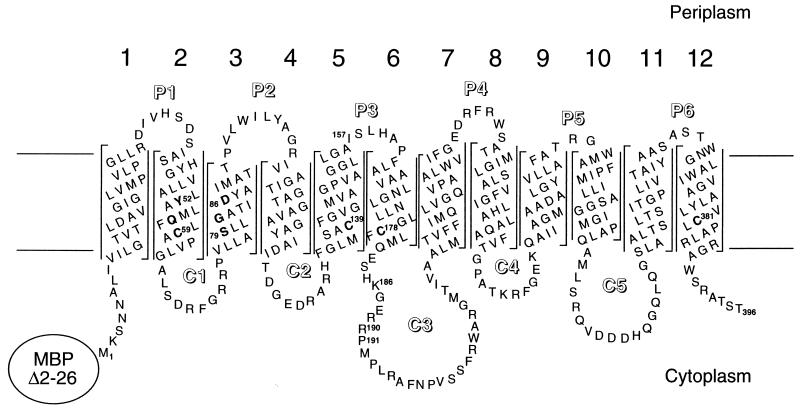

FIG. 1.

Membrane topology of the CMT10 MBP-TetA chimeric protein. The sequences of the 12 pBR322-encoded TetA TM segments are drawn in α-helical conformation, and the locations of periplasmic loops (P1 to P6) and cytoplasmic loops (C1 to C5) are indicated. The MBPΔ2-26 domain is fused to the N-terminal methionine of TetA. Naturally occurring cysteine residues in TM2 (C59), TM5 (C139), TM6 (C178), and TM12 (C381) are shown in boldface, as are several residues that may line the tetracycline transport pathway (13, 31, 34). Cysteines were introduced into a Cys-minus version of the protein at position I157 in the P3 loop (in the I157C protein) and between R190 and P191 of the C3 loop (in the C3Cys protein). The topology model is based on that for Tn10-encoded TetA (5) and has been modified in the P2 and P5 loops according to fine-structure mapping of the TM3 and TM9 boundaries of Tn10-encoded TetA (10, 13).

Considerable progress has been made in determining the mechanism of transport and the substrate translocation pathway through the proteins. Aspartates in TM1, TM3, and TM9 (11, 19, 32) and a histidine in TM8 (30), which are conserved in all family members (2), have been shown by site-directed mutagenesis experiments to be essential for tetracycline and proton transport. The substrate translocation pathway through the Tn10-encoded protein is lined by Y50 and Q54 in TM2 (34) and by S77, G80, and D84 in TM3 (13, 31). Amino acids in the conserved GXXXX(R/K)XGR(R/K) sequence in the C1 loop appear to form a gate that regulates movement of tetracycline through the Tn10-encoded transporter (29, 33). Many other functionally important residues have been located in the pBR322-encoded protein by random mutagenesis (20).

In this paper, we report on the functional importance of the four naturally occurring cysteines that reside in TM2 (C59), TM5 (C139), TM6 (C178), and TM12 (C381) of pBR322-encoded TetA (Fig. 1). We also have examined the local environments near the cysteines by attempting to label them with 3-(N-maleimidylpropionyl)biocytin (biotin maleimide). While none of the cysteines are fully conserved, each one is found in at least three of the six members of the family (2). It was shown previously that substitutions at C59 and C139 reduce activity (20); however, the requirements for C178 and C381 have not been studied before. All four cysteines appear to be located within one to two α-helical turns of the cytoplasmic surface of the inner membrane and therefore could be accessible to the aqueous phase. In addition, C59 is located on the same side of TM2 as Y52 and Q56, and by comparison to Tn10-encoded TetA, C59 could face the tetracycline translocation pathway in pBR322-encoded TetA (Fig. 1). Thus, an analysis of the chemical labeling properties of C59 may provide additional information about the properties of the translocation pathway.

Effects of cysteine substitutions on activity.

The functional requirements for the naturally occurring cysteines in pBR322-encoded TetA were investigated by using four cysteine-to-serine single substitution mutants (the C59S, C139S, C178S, and C381S proteins) and a Cys-minus mutant (CMT0) in which all four cysteines were replaced with serines (Table 1). Four cysteine-to-serine triple substitution mutants (designated C59, C139, C178, and C381) were constructed and used to determine the accessibility of each cysteine to biotin maleimide. In addition, two CMT0 derivatives with cysteines in the P3 and C3 loops (the I157C and C3Cys proteins) were constructed as controls for labeling experiments. The tetracycline resistance levels conferred by the triple substitution mutants and the I157C and C3Cys proteins also were measured. All of the proteins studied are derivatives of the CMT10 maltose-binding protein (MBP)–TetA chimeric protein in which an MBPΔ2-26 domain that lacks a signal sequence is attached to the N-terminal methionine of TetA (8, 22). The MBP domain served as a tag for immunoprecipitation of biotinylated proteins and detection of proteins by Western immunoblotting. It should be noted that MBP lacks cysteines (4).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5 | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 9 |

| PR722 | [F′ Δ(lacIZ)E65 pro+/proC::Tn5 Δ(lacIZYA)U169 hsdS20 ara-14 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-15 mtl-1 supE44 leu] | New England Biolabs |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCMT10 | AmprlacIqmalE(Δ2-26)-tetA fusion gene | 22 |

| pC59S | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C59S substitution | This study |

| pC139S | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C139S substitution | This study |

| pC178S | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C178S substitution | This study |

| pC381S | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C381S substitution | This study |

| pC59 | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C139S, C178S, and C381S substitutions | This study |

| pC139 | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C59S, C178S, and C381S substitutions | This study |

| pC178 | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C59S, C139S, and C381S substitutions | This study |

| pC381 | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C59S, C139S, and C178S substitutions | This study |

| pCMT0 | pCMT10 derivative encoding TetA C59S, C139S, C178S, and C381S substitutions | This study |

| pI157C | pCMT0 derivative encoding TetA I157C substitution | This study |

| pC3Cys | pCMT0 derivative encoding -R190-G-A-C-H-R-P191-insertion in the TetA C3 loop | This study |

The substitution of serine codons for each of the four cysteine codons was accomplished by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of the tetA gene inserted into bacteriophage M13mp18 (27, 35). After confirmation of mutations by DNA sequencing, DNA fragments were swapped by conventional cloning procedures for the wild-type sequence regions in plasmid pCMT10 (22), creating the substitution mutant plasmids described in Table 1. Plasmid pI157C, which contains a TGC cysteine codon in place of the I157 ATC codon, was constructed by ligating a PCR amplification product into the BamHI-SphI region of tetA DNA in plasmid pCMT0. The 3′ (leftward) PCR primer used for DNA synthesis encoded the I157C substitution. Plasmid pC3Cys was constructed by inserting a synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding a -Gly-Ala-Cys-His-Arg-sequence at the SalI restriction site between the R190 and the P191 codons of tetA DNA in pCMT0. In all cases, the sequences of the mutagenized inserts were confirmed by double-stranded DNA sequencing after they were cloned into the plasmids.

Plasmids were introduced into Escherichia coli DH5 to determine if the cysteine substitution mutants conferred tetracycline resistance. Cultures first were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani liquid medium containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml until mid-log phase. A series of 5-ml Luria-Bertani liquid broth cultures containing the appropriate range of tetracycline concentrations but no ampicillin was prepared and inoculated with 0.005 to 0.01 ml of the culture broths. The test cultures then were incubated overnight at 37°C and were scored the next day for the presence or absence of turbidity.

Untransformed strain DH5 and strain DH5/pCMT10, which synthesizes the CMT10 protein, served as controls in the experiments. As shown in Table 2, the MIC of tetracycline for DH5/pCMT10 was 60 μg/ml, whereas the MIC for untransformed DH5 cells was 1 μg/ml. The tetracycline resistance levels conferred by the mutants fell between these limits. In all four cases, the substitution of a single cysteine reduced the MICs of tetracycline to 50 μg/ml; none of the substitutions appeared to exert a larger effect on activity than did the others. Similarly, all four triple substitutions caused equivalent reductions in the MICs of tetracycline. In these cases, MICs were reduced to 25 μg/ml. A larger reduction in the MIC (to 15 μg/ml) was observed for strain DH5/pCMT0, which synthesizes the Cys-minus CMT0 protein. As shown below, the reductions in tetracycline MICs were not caused by decreased expression of the mutant proteins.

TABLE 2.

Tetracycline MICs for bacterial strains

| Strain | Tetracycline MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| DH5 | 1 |

| DH5/pCMT10 | 60 |

| DH5/pC59S | 50 |

| DH5/pC139S | 50 |

| DH5/pC178S | 50 |

| DH5/pC381S | 50 |

| DH5/pC59 | 25 |

| DH5/pC139 | 25 |

| DH5/pC178 | 25 |

| DH5/pC381 | 25 |

| DH5/pCMT0 | 15 |

| DH5/pI157C | 20 |

| DH5/pC3Cys | 4 |

The results show for the first time that C179 and C381 are not essential for the activity of the pBR322-encoded TetA protein, and they confirm earlier work showing that C59 and C139 also are not essential for function. In the previous study (20), it was shown that the substitution of tyrosines for C59 and C139 produced a greater reduction in MIC than was observed with serine substitutions. This may be attributable to the larger volume of the tyrosine side chain. Because the resistance levels conferred by the single, triple, and Cys-minus substitution mutants were significantly above the baseline resistance level of untransformed DH5 cells, only minor changes in tertiary structure appear to have resulted from the mutations (20). This indicates that the Cys-minus protein should be useful for analyzing the structure and function of pBR322-encoded TetA by the technique of cysteine substitution mutagenesis and chemical labeling.

The I157C protein conferred the same level of tetracycline resistance as did CMT0. This suggests that I157 is not required for catalysis of tetracycline transport. The importance of I157 has not been studied before, but it has been shown that replacement of a fully conserved serine residue located immediately downstream in the sequence almost completely inactivates the Tn10-encoded protein (12). Interestingly, the isoleucine at position 157 of pBR322-encoded TetA, while not essential, is conserved in four of the six classes of TetA proteins (2). In contrast, the insertion of the -Gly-Ala-Cys-His-Arg-sequence into the C3 loop greatly reduced the MIC for the C3Cys protein. This result is noteworthy in that mutations in the C3 loop sequence often do not cause a large reduction in the tetracycline MIC (15, 20). In fact, the efflux function of the Tn10-encoded protein can be reconstituted by expressing it as separate N- and C-terminal six-TM-segment domains derived by splitting the protein in the C3 loop (26). Although the C3Cys insertion exerted a strong effect on the MIC for the strain, the mutation did not appear to change the membrane topology of the transporter. In this regard, the C3 loop of C3Cys remained as susceptible to trypsin, chymotrypsin, and endoproteinase LysC digestion in inverted membrane vesicles as did the C3 loop of CMT10 (data not shown).

Local environments of cysteines.

The local environments of the cysteines were examined by determining if they were susceptible to labeling with biotin maleimide (6, 17, 18). Cysteines react with biotin maleimide, and N-ethylmaleimide, by nucleophilic addition of a thiolate anion to the olefinic double bond of the maleimide ring (16). The formation of cysteinyl thiolate anions is favored by increasing the solution pH (7) and is optimum in an aqueous rather than in a nonpolar medium. For this reason, biotin maleimide reacts preferentially with cysteines exposed to the aqueous phase rather than with cysteines residing within the nonpolar interior of the membrane. As shown below, biotin maleimide can pass through both the outer and the inner membranes of E. coli.

Labeling experiments were performed with strain PR722 transformed with the chimeric protein expression plasmids. Strains were grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 to 0.7 in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% dextrose, 0.2% Casamino Acids, 2 μg of thiamine-HCl per ml, and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. MBP-TetA protein synthesis was induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at a 1 mM final concentration to the cultures for 30 min. Subsequently, cells were washed once in M9 salts containing 2 mM dithiothreitol and once in M9 salts alone and then were resuspended at 5 OD600 U/ml in 20 mM 3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0)–0.25 M KCl–1 mM MgSO4 buffer (18) containing 1 mM biotin maleimide (Molecular Probes) (added from a 100 mM stock in dimethyl formamide). Labeling was performed for 30 min at 37°C, and then excess reagent was quenched and removed by washing cells three times with M9 salts containing 28 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. When experiments were conducted with the charged, membrane-impermeant blocking reagent stilbenedisulfonate maleimide (SDM) (Molecular Probes) (6, 17), cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the above 3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid buffer containing 250 μM SDM and then were washed one time in M9 salts before resuspension in labeling buffer containing 1 mM biotin maleimide.

After completion of labeling and washing steps, cell pellets were lysed at 5 OD600 U/ml in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) by heating them at 65°C for 5 min. To detect biotinylated MBP-TetA proteins, lysates were diluted 10-fold in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7), and 50-μl aliquots of the lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-MBP rabbit antiserum (New England Biolabs), separated on a 10% polyacrylamide–SDS gel (14), and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose filter paper. Filter papers were incubated in a solution of avidin complexed with biotinylated alkaline phosphatase (ABC kit; Pierce) and developed with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate substrates (Promega). The relative expression levels of MBP-TetA proteins were compared by incubating a parallel set of electroblotted samples with rabbit anti-MBP antiserum and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Promega) followed by development with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (21).

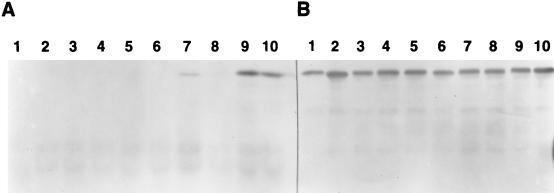

The results obtained for biotin maleimide labeling of CMT10, the four triple cysteine-to-serine substitution mutants, and CMT0 are shown in Fig. 2A. None of the four naturally occurring cysteines in CMT10 (lane 2) or in the C59, C139, C178, and C381 proteins (lanes 3 to 6) reacted with the reagent. In contrast, the periplasmic and cytoplasmic loop substitution mutants used as positive controls—I157C (lane 7) and C3Cys (lane 9)—were labeled strongly. Labeling was specific for cysteines, as the CMT0 negative control protein (lane 1) was not labeled. The results obtained with C3Cys rule out the possibility that the naturally occurring cysteines failed to be labeled because the cytoplasmic membrane is impermeable to biotin maleimide. In addition, the lack of labeling was not caused by poor expression of the mutants (Fig. 2B). The analysis of the control proteins demonstrates that SDM blocking can be applied to discriminate between periplasmic and cytoplasmic locations in pBR322-encoded TetA. In this regard, pretreatment of cells with SDM blocked I157C (lane 8) but not C3Cys (lane 10) from subsequent reaction with biotin maleimide.

FIG. 2.

Biotin maleimide labeling of MBP-TetA cysteine substitution mutants. (A) Avidin-stained electroblot of biotin maleimide-labeled proteins. Samples (50 μl) of SDS-solubilized, biotin maleimide-labeled cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-MBP antiserum, analyzed on a 10% polyacrylamide–SDS gel, and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and the blot was developed as described in the text to detect biotinylated MBP-TetA proteins. Lane 1, CMT0; lane 2, CMT10; lane 3, C59; lane 4, C139; lane 5, C178; lane 6, C381; lane 7, I157C; lane 8, I157C blocked with SDM before biotin maleimide labeling; lane 9, C3Cys; lane 10, C3Cys blocked with SDM before biotin maleimide labeling. (B) Western immunoblot of biotin maleimide-labeled proteins. Samples (19 μl) of SDS-solubilized, biotin maleimide-labeled cells were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide–SDS gel and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and the blot was developed as described in the text to detect MBP-TetA proteins. Sample order is the same as in panel A.

The results indicate that the local environments of the four naturally occurring cysteines are unfavorable for their reaction with biotin maleimide. This could be explained by the exclusion of water or biotin maleimide from these sites or by increases in the cysteine pKas due to juxtaposed negatively charged amino acid side chains or phospholipids (3a). Although it is difficult to discriminate between possibilities, topology mapping experiments and hydropathy modeling indicate that all four cysteines could reside within the interior of the membrane. There are few negatively charged amino acids near the cysteines in the primary structure, but negatively charged residues or phospholipids could be located nearby in the folded structure of the protein.

In contrast, the labeling results indicate that the regions of the P3 and C3 loops containing the I157C and C3Cys substitutions are in contact with the aqueous phase. In further support of this conclusion, K186 located just upstream of the C3 loop insertion site in pBR322-encoded TetA can be cleaved by endoproteinase LysC (8, 21, 22), and S156 in the P3 loop of the Tn10-encoded protein can be labeled with N-ethylmaleimide (12).

N-Ethylmaleimide labeling experiments performed with the Tn10-encoded TetA protein suggest that the tetracycline translocation pathway through the transporter is relatively hydrophobic and narrow (13). In this regard, the activity of Tn10-encoded TetA is inhibited by amino acid substitutions that increase the side chain volumes of residues lining the translocation pathway, and cysteines introduced into the pathway show almost no reactivity with N-ethylmaleimide (13). The biotin maleimide labeling results that were obtained for the C59 mutant are consistent with those obtained for Tn10-encoded TetA. They indicate that the environment surrounding C59, which probably is located on the translocation pathway, is unfavorable for reaction with biotin maleimide. As in the case of Tn10-encoded TetA, the translocation pathway through the pBR322-encoded protein appears to restrict the entry of moderately bulky maleimide compounds and their reaction with cysteines.

Concluding remarks.

The four cysteines in the pBR322-encoded TetA protein are important, but not essential, for activity. These residues reside in regions of TM α-helices that are unfavorable for the generation of thiolate anions or reaction with bulky labeling reagents. Because a Cys-minus derivative of the protein retains significant activity, the structure and function of pBR322-encoded TetA can be investigated by cysteine substitution mutagenesis and chemical labeling.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a grant to K.W.M. from the National Institutes of Health (GM47269).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allard J D, Bertrand K P. Membrane topology of the pBR322 tetracycline resistance protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17809–17819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allard J D, Bertrand K P. Sequence of a class E tetracycline resistance gene from Escherichia coli and comparison of related tetracycline efflux proteins. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4554–4560. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4554-4560.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolivar F, Rodriguez R L, Greene P J, Betlach M C, Heynecker H L, Boyer H W, Crosa J H, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of a new cloning vehicle. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Bulaj G, Kortemme T, Goldenberg D P. Ionization-reactivity relationships for cysteine thiols in polypeptides. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8965–8972. doi: 10.1021/bi973101r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duplay P, Bedouelle H, Fowler A, Zabin I, Saurin W, Hofnung M. Sequences of the malE gene and of its product, the maltose-binding protein of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10606–10613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckert B, Beck C F. Topology of the transposon Tn10-encoded tetracycline resistance protein within the inner membrane of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11663–11670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glavas N A, Hou C, Bragg P D. Organization in the membrane of the N-terminal proton-translocating domain of the β subunit of the pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;214:230–238. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory J D. The stability of N-ethylmaleimide and its reaction with sulfhydryl groups. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:3922–3923. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo D, Liu J, Motlagh A, Jewell J, Miller K W. Efficient insertion of odd-numbered transmembrane segments of the tetracycline resistance protein requires even-numbered segments. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30829–30834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura T, Suzuki M, Sawai T, Yamaguchi A. Determination of a transmembrane segment using cysteine-scanning mutants of transposon Tn10-encoded metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15896–15899. doi: 10.1021/bi961568g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura T, Yamaguchi A. Asp-285 of the metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli is essential for substrate binding. FEBS Lett. 1996;388:50–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura T, Ohnuma M, Sawai T, Yamaguchi A. Membrane topology of the transposon 10-encoded metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter as studied by site-directed chemical labeling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:580–585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura T, Shiina Y, Sawai T, Yamaguchi A. Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis around transmembrane segment III of Tn10-encoded metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5243–5247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy S B. Resistance to the tetracyclines. In: Bryan L E, editor. Antimicrobial drug resistance. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 191–240. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu T-Y. The role of sulfur in proteins. In: Neurath H, Hill R L, Boeder C-L, editors. The proteins. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 239–402. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loo T W, Clarke D M. Membrane topology of a cysteine-less mutant of human P-glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:843–848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matos M, Fann M-C, Yan R-T, Maloney P C. Enzymatic and biochemical probes of residues external to the translocation pathway of UhpT, the sugar phosphate carrier of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18571–18575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurry L M, Stephan M, Levy S B. Decreased function of the class B tetracycline efflux protein Tet with mutations at aspartate 15, a putative intramembrane residue. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6294–6297. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6294-6297.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNicholas P, Chopra I, Rothstein D M. Genetic analysis of the tetA(C) gene on plasmid pBR322. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7926–7933. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.7926-7933.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller K W, Konen P L, Olson J, Ratanavanich K M. Membrane protein topology determination by proteolysis of maltose binding protein fusions. Anal Biochem. 1993;215:118–128. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller K W, Jewell J E. Identification of a topology control domain in the tetracycline resistance protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;322:445–452. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen T T, Postle K, Bertrand K P. Sequence homology between the tetracycline-resistance determinants of Tn10 and pBR322. Gene. 1983;25:83–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikaido H, Saier M H., Jr Transport proteins in bacteria: common themes in their design. Science. 1992;258:936–942. doi: 10.1126/science.1279804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin R A, Levy S B, Heinrikson R L, Kezdy F J. Gene duplication in the evolution of the two complementing domains of gram-negative bacterial tetracycline efflux proteins. Gene. 1990;87:7–13. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90489-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin R A, Levy S B. Tet protein domains interact productively to mediate tetracycline resistance when present on separate polypeptides. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4503–4509. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4503-4509.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor J W, Ott J, Eckstein F. The rapid generation of oligonucleotide-directed mutations at high frequency using phosphorothioate-modified DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8765–8785. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.24.8765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaguchi A, Udagawa T, Sawai T. Transport of divalent cations with tetracycline as mediated by the transposon Tn10-encoded tetracycline resistance protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4809–4813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaguchi A, Ono N, Akasaka T, Noumi T, Sawai T. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by a transposon, Tn10. The role of the conserved dipeptide, Ser65-Asp66, in tetracycline transport. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15525–15530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamaguchi A, Adachi K, Akasaka T, Ono N, Sawai T. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by a transposon, Tn10. Histidine 257 plays an essential role in H+ translocation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6045–6051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi A, Ono N, Akasaka T, Sawai T. Serine residues responsible for tetracycline transport are on a vertical stripe including Asp-84 on one side of transmembrane helix 3 in transposon Tn10-encoded tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1992;307:229–232. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80773-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi A, Akasaka T, Ono H, Someya Y, Nakatani M. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by transposon Tn10. Roles of aspartyl residues located in the putative transmembrane helices. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7490–7498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi A, Someya Y, Sawai T. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by transposon Tn10. The role of a conserved sequence motif, GXXXXRXGRR, in a putative cytoplasmic loop between helices 2 and 3. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19155–19162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi A, Akasaka T, Kimura T, Sakai T, Adachi Y, Sawai T. Role of the conserved quartets of residues located in the N- and C-terminal halves of the transposon Tn10-encoded metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5698–5704. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]