Abstract

Objective:

Although immune checkpoint blockade has demonstrated limited effectiveness against ovarian cancer, subset analyses from completed trials suggest possible superior efficacy in the clear cell carcinoma subtype. The aim of this study was to describe the outcomes of patients with ovarian clear cell carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint blockade.

Methods:

This was a single-institution, retrospective case series of patients with ovarian clear cell carcinoma treated with a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor with or without concomitant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) inhibition between January 2016 to June 2021. Demographic variables, tumor microenvironment, molecular data, and clinical outcomes were examined. Time-to-treatment failure was defined as the number of days between start of treatment and next line of treatment or death.

Results:

A total of 16 eligible patients were analyzed. The median treatment duration was 56 days (range, 14–574); median time to treatment failure was 99 days (range, 27–1568). The reason for discontinuation was disease progression in 88% of cases. Four patients (25%) experienced durable clinical benefit (time to treatment failure ≥180 days). One patient was treated twice with combined immune checkpoint blockade and experienced a complete response each time. All 12 patients who underwent clinical tumor-normal molecular profiling had microsatellite-stable disease, and all but one had low tumor mutation burden. Multiplex immunofluorescence analysis available from pre-treatment biopsies of two patients with clinical benefit demonstrated abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressing PD-1.

Conclusion:

Our study suggests a potential role for immune checkpoint blockade in patients with clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Identification of genetic and microenvironmental biomarkers predictive of response will be key to guide therapy.

Keywords: Ovarian, Clear Cell Carcinoma, Immunotherapy, Immune Checkpoint Blockade

Precis:

In our single-institution experience of 16 patients with ovarian clear cell carcinoma, treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors resulted in a durable clinical benefit rate of 25%.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian clear cell carcinoma is an aggressive gynecologic malignancy with a high prevalence in Asian and Pacific Islander populations (1). It is associated with endometriosis and a high frequency of somatic mutations in ARID1A and in genes encoding for components of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway (2, 3). Although 47–81% of patients present with stage I/II disease, outcomes for patients with advanced disease are inferior to those of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancers (2). Although clear cell carcinomas are less chemoresponsive than high-grade serous ovarian cancers, standard upfront treatment includes surgery with platinum-based chemotherapy, with first-line response rates of 18–56% (2, 4, 5). After disease progression, response to subsequent lines of chemotherapy is limited, with response rates of 6–8% (6).

Recently, immune checkpoint blockade has emerged at the forefront of gynecologic cancer treatment. Although evidence of tumor immune recognition has been demonstrated in patients with ovarian cancer, response rates to immune checkpoint blockade have been modest, ranging from 8–13% with single-agent therapy, up to 31% with combinations of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibition (7–11).

Subset analyses from clinical trials suggest that immune checkpoint blockade may offer superior benefit to patients with clear cell histology, although numbers are limited. In a phase II randomized controlled trial of nivolumab versus nivolumab/ipilimumab for recurrent or persistent ovarian cancer, patients with the clear cell subtype were approximately five times more likely to respond to treatment with nivolumab/ipilimumab compared to patients with other subtypes (7). In the phase II KEYNOTE-100 study, one of the two patients with a complete response to immunotherapy had clear cell histology, and in a phase 1b study of avelumab for patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer, of two patients with clear cell histology, one had a partial response and the other had an immune-related partial response (9, 10).

Based on these observations, we sought to examine the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in patients with clear cell carcinoma of the ovary and explore the histologic and molecular characteristics that could predict clinical benefit.

METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

We identified all patients with histopathologically confirmed ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center with at least one dose of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor with or without a CTLA-4 inhibitor between January 2016 and June 2021. Patients who had been treated as part of an unpublished trial were excluded. Patients who had received immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy were also excluded to homogenize the cohort as it would have been difficult to assess the impact of immune checkpoint blockade in the presence of cytotoxic drugs. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (#15–200). Patients that have provided prior consent to future biospecimen and data use (# 06–107) were included.

Clinical Information

Age at diagnosis, stage, somatic mutations, tumor mutation burden, association with endometriosis, and immunohistochemistry results for mismatch repair proteins were obtained from the electronic medical record. Data on surgical outcomes, such as complete gross resection, optimal debulking, and suboptimal debulking, were collected. Use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, treatment regimen, dates of treatment, next line of treatment, and date of death or last follow-up (until database closure on October 7, 2021) were noted. Other treatment variables, such as reason for discontinuation, treatment-related adverse events, progression of disease (radiographic/clinical), and number of treatment lines before and after immunotherapy were also obtained.

Study Definitions

Stage was assessed using the 2014 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics classification system (12). Complete gross resection was defined as no macroscopic tumor remaining after surgery, optimal debulking as residual tumor ≤1 cm, and suboptimal debulking as residual tumor >1 cm. Treatment duration was defined as the time from first infusion until the clinic visit after the last infusion. Time-to-treatment failure was defined as the time from start of treatment until the start of the next-line treatment or death. Progression free survival was defined as the time between start of treatment until the date of radiologic scan demonstrating disease progression after which treatment was discontinued. Patients who had not started a next line of treatment at the time of database closure (October 7, 2021) were censored at date of last follow-up. Durable clinical benefit was defined as time to treatment failure of ≥180 days or no evidence of disease at the time of data censoring. Toxicities were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 4.0.

Tumor Molecular Profiling and Immunofluorescence Analyses

Twelve patients underwent tumor-normal targeted massively parallel sequencing analysis of up to 468 cancer-related genes using archival tumor tissue (13). The genomic data extracted included somatic pathogenic mutations, copy number alterations, and structural variants (n=12); germline pathogenic variants (n=8); MSIsensor score (>10 considered MSI-high); and tumor mutation burden (≥10 mutations/megabase considered tumor mutation burden-high) (13, 14). Multiplex immunofluorescence analyses were performed on tumor biopsy samples collected immediately prior to therapy. For immunofluorescence analyses, primary antibody staining conditions were optimized using standard immunohistochemistry on the Leica Bond RX automated research stainer with DAB detection (Leica Bond Polymer Refine Detection DS9800). Using 4-μm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and serial antibody titrations, the optimal antibody concentration was determined followed by transition to a seven-color multiplex assay with equivalency. The multiplex immunofluorescence antibody panel included CD8, PD-L1, and PD-1, and a panel of cytokeratin antibodies (PanCK, CK7, Cam5.2).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed using the number of patients in each category and percentage. Continuous variables were assessed for normality. As none of the continuous variables had a parametric distribution, they were described using median and range. Descriptive statistics were used to convey the results of this case series. All analyses were performed with Stata (version 17.0).

RESULTS

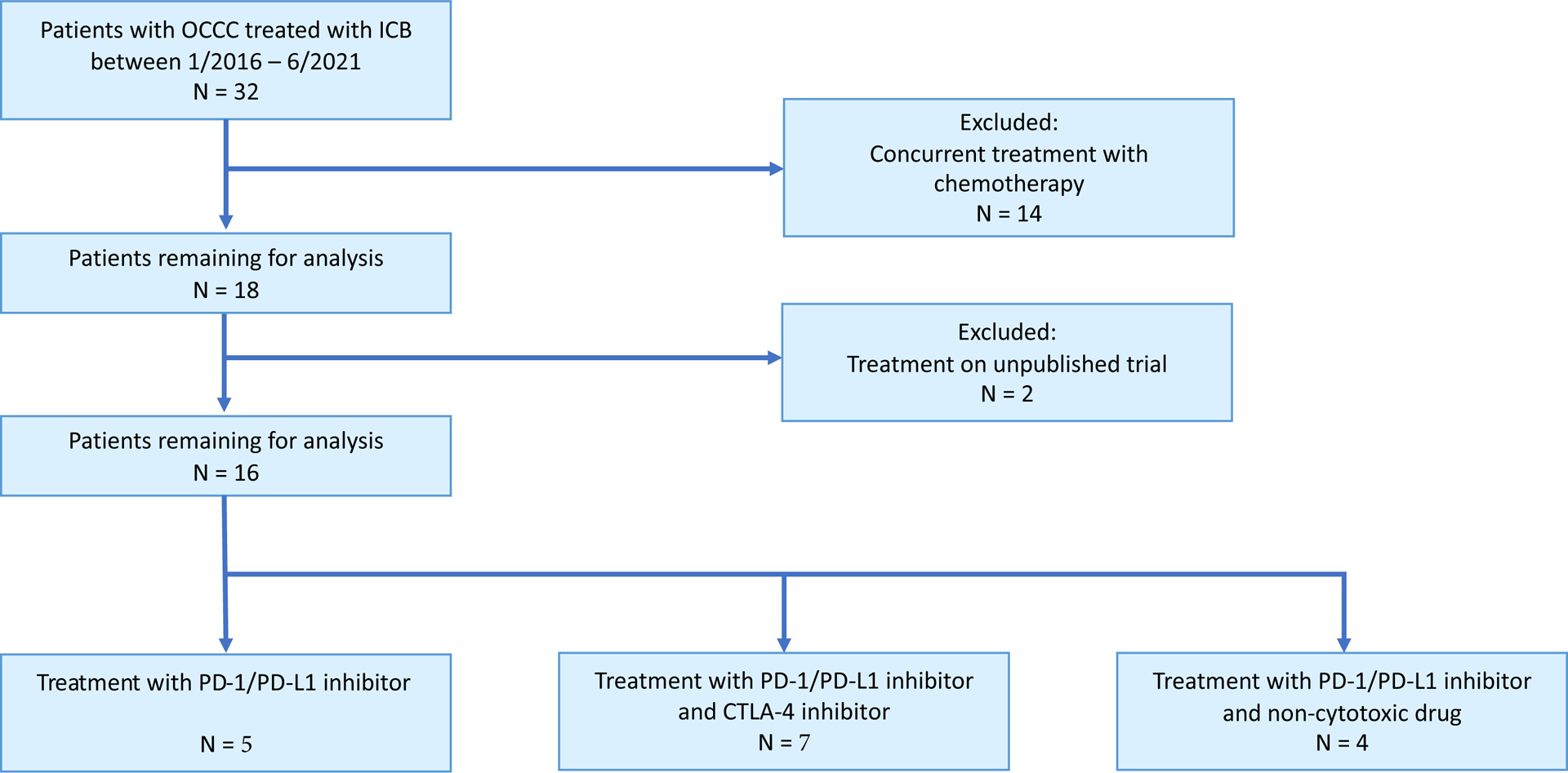

Of 32 identified patients, 16 were included in the analysis. Fourteen patients who received immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy and 2 patients who were part of an unpublished trial were excluded (Figure 1, Table 1). The median age at diagnosis was 50 years (range, 34–69), and 9 (56%) patients had endometriosis-associated tumors. All patients have been confirmed to have clear cell carcinoma with no mixed histologic features. Two patients had germline mutations, including a monoallelic PMS2 mutation and a pathogenic BRCA1 variant with copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (Table 2).

Figure 1:

CONSORT diagram summarizing the selection process and final series of the 16 patients included in this study.

Table 1:

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with and without clinical benefit from immune checkpoint blockade therapy

| Variables | Patients with clinical benefit n (%) | Patients with no clinical benefit n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 4 (25) | 12 (75) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (mean), range, YEARS | 50.5 (49.3), 34–62 | 51.5 (53.5), 38 – 69 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||

| I | 0 | 2 (17) |

| II | 0 | 1 (8) |

| III | 3 (75) | 5 (42) |

| IV | 1 (25) | 4 (33) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 2 (50) | 2 (17) |

| No | 2 (50) | 10 (83) |

| Surgery outcome | ||

| CGR | 0 | 5 (42) |

| OD | 2 (50) | 3 (25) |

| SD | 2 (50) | 1 (8) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (17) |

| No cytoreductive surgery | 0 | 1 (8) |

| ICB target | ||

| PD-1/PD-L1 | 1 (25) | 4 (33) |

| PD-1/PD-L1 + CTLA-4 | 3 (75) | 4 (33) |

| PD-1/PD-L1 + targeted therapy | 0 | 4 (33) |

| ICB duration, median (mean), range, DAYS | 383 (340), 21–574 | 51.5 (57.6), 14 – 153 |

| Discontinuation reason a | ||

| POD | 2 (50) | 12 (100) |

| Adverse event | 1 (25) | 1 (8) |

| Still on treatment | 1 (25) | 0 |

| TTF, median (mean), range, DAYS | 402 (776), 358–1568b | 76 (87), 27–167 |

| PFS, median (mean), range, DAYS | 387 (754), 336–1538b | 53 (70), 21 – 151 |

| Number of treatment lines | ||

| Prior to ICB | 3 (3.4), 1–7 | 3 (2.9), 1–7 |

| After ICB | 2 (1.6), 0–4 | 1 (1.2), 0–6 |

CGR: complete gross resection; OD: optimal debulking; SD: suboptimal debulking; ICB: immune checkpoint blockade; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4; POD: progression of disease; TTF: time to treatment failure; PFS: progression free survival

One patient discontinued treatment due to simultaneous POD and adverse event

Does not include TTF/PFS for Patient 10 and Patient 12, both of whom remain disease free and have not started next-line therapy at the time of data freeze, when censoring occurred.

Table 2:

Patient demographic variables by individual patient

| Patient | Age at Diagnosis | Germline Mutation | Stage | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | Surgery Outcome | Concurrent Endometriosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | negative | IVB | No | OD | No |

| 2 | 58 | negative | IIA | No | CGR | No |

| 3 | 34 | negative | IIIC | Yes | SD | Yes |

| 4 | 67 | - | IC | No | OD | No |

| 5 | 63 | PMS2 | IIIA1 | No | CGR | Yes |

| 6 | 53 | negative | IVB | No | OD | Yes |

| 7 | 50 | negative | IIIC | No | OD | Yes |

| 8 | 38 | negative | IVB | Yes | CGR | Yes |

| 9 | 49 | SDHA | IIIA2 | No | CGR | Yes |

| 10 | 47 | negative | IIIB | No | OD | Yes |

| 11 | 54 | BRCA1 | IVB | No | SD | No |

| 12 | 62 | negative | IIIC | Yes | OD | No |

| 13 | 48 | - | IC | No | - | No |

| 14 | 58 | - | IIIB | No | - | Yes |

| 15 | 42 | - | IV | Yes | - | No |

| 16 | 47 | - | IIIA | No | CGR | Yes |

OD: optimal debulking; CGR: complete gross resection; SD: suboptimal debulking

After a median of 3 lines of cytotoxic treatment (range, 1–7), 5 patients received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor alone, 7 received a combination of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor and CTLA-4 inhibitor, and 4 received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor in combination with a non-cytotoxic drug (Tables 1 and 3). The median duration of treatment was 56 days (range, 14–574). The most common reason for discontinuation was progression of disease in 14 (88%) patients. Two patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events—a grade 4 acute liver injury and grade 4 autoimmune neuropathy (Table 3). The median time to treatment failure was 99 days (range, 27–1568) and the median progression-free survival was 80 days (range, 21 – 1538). At the time of database closure, 2 patients (Patient 10 and Patient 12) had not started next line of treatment and were either disease free or had ongoing response (157 days and 383 days, respectively; Table 3). Four patients (25%) experienced durable clinical benefit. The median number of treatment lines after immunotherapy was 1 (range, 0–6). Five patients did not undergo further systemic therapy after treatment discontinuation due to progression of disease and died within 2 months.

Table 3:

Treatment characteristics by individual patient

| Patient | Regimen | Treatment Time (days) | Discontinuation Reason | Type of Progression | TTF (days) | PFS (days) | Lines before Treatment | Lines after Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PD-1/PD-L1 | 153 | POD | radiographic | 167 | 151 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 14 | POD | clinical/radiographic | 36 | 21 | 7 | 0 |

| 3 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 329 | POD | radiographic | 358 | 336 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 56 | POD | clinical/radiographic | 106 | 81 | 4 | 2 |

| 5 | PD-1/PD-L1+ targeted therapy | 28 | POD, adverse event (autoimmune neuropathy) | clinical, radiographic | 60 | 43 | 3 | 0 |

| 6 | PD-1/PD-L1 | 28 | POD | clinical, radiographic | 53 | 49 | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | PD-1/PD-L1 | 49 | POD | radiographic | 74 | 50 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | PD-1/PD-L1+ targeted therapy | 104 | POD | radiographic | 146 | 119 | 3 | 1 |

| 9 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 14 | POD | clinical, radiographic | 78 | 45 | 3 | 0 |

| 10 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 574 | adverse event (acute liver injury) | N/A | 1568 | 1538 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 21 | adverse event | N/A | 157a | N/A | 3 | N/A |

| 11 | PD-1/PD-L1 | 393 | POD | radiographic/biopsy-proven | 402 | 387 | 7 | 2 |

| 12 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 383 | N/A | N/A | 383a | N/A | 2 | N/A |

| 13 | PD-1/PD-L1 | 54 | POD | radiographic | 62 | 55 | 2 | 6 |

| 14 | PD-1/PD-L1+CTLA-4 | 63 | POD | clinical/radiographic | 99 | 80 | 1 | 0 |

| 15 | PD-1/PD-L1+ targeted therapy | 15 | POD | clinical/radiographic | 27 | 21 | 2 | 0 |

| 16 | PD-1/PD-L1+ targeted therapy | 113 | POD | radiographic | 134 | 123 | 2 | 1 |

TTF: time to treatment failure; PFS: progression free survival; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4; POD: progression of disease

these patients continue to have an ongoing response to ICB therapy and remain disease free at the time of database closure. Their duration of response between start of ICB and time of data censoring is indicated here.

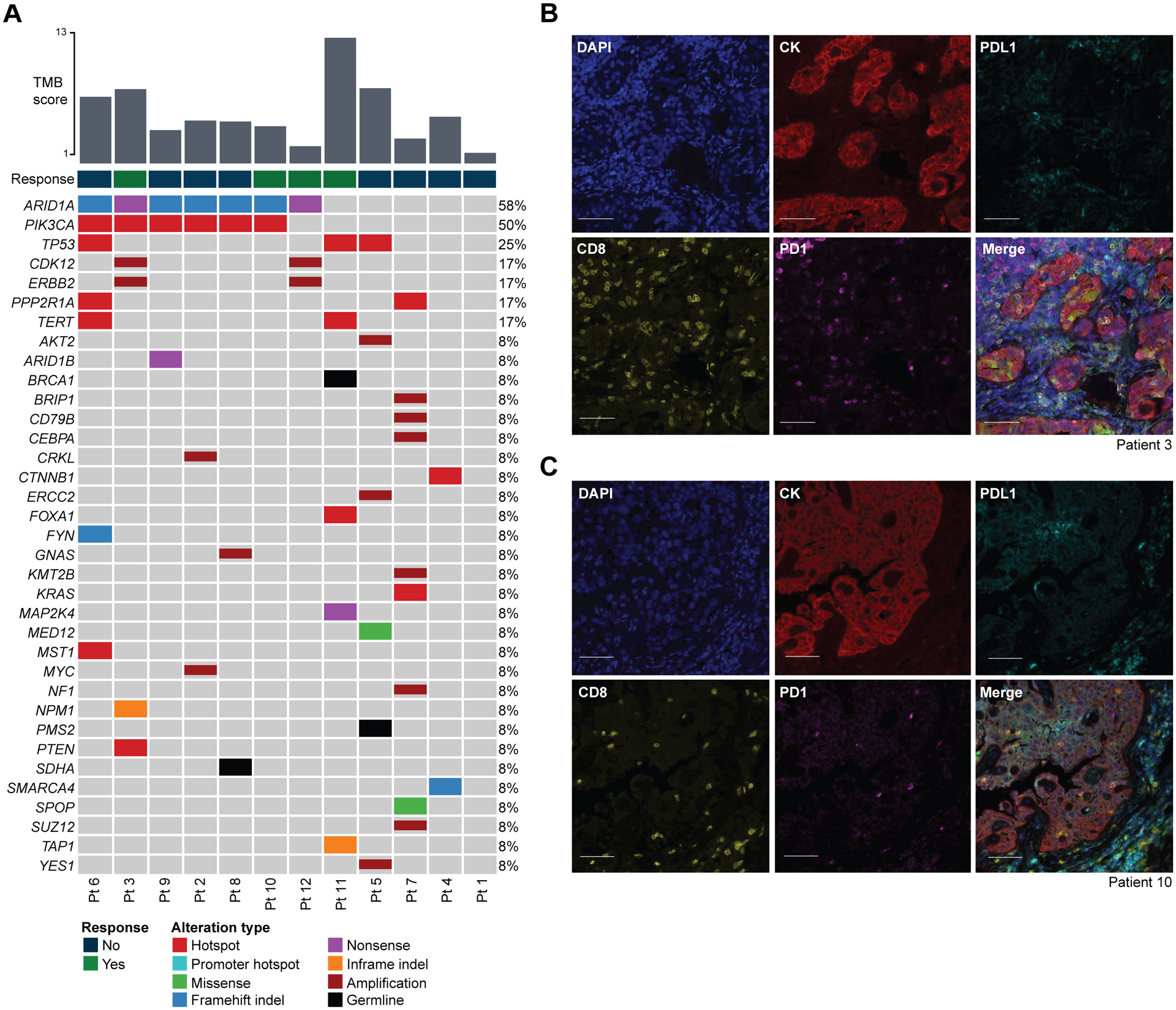

Tumors from 12 patients underwent sequencing (Figure 2A). The median number of somatic mutations was 6 (range, 1–15), with a median tumor mutation burden of 4.4 mutations/megabase (range, 0.9–13.2). One tumor mutation burden-high cancer had 13.2 mutations/megabase. Truncating ARID1A mutations were found in 7 (58%) of 12 specimens. Three tumors (25%) harbored pathogenic TP53 mutations, and 6 (50%) had alterations in PIK3CA. Immunohistochemistry analysis for mismatch repair proteins was performed in 7 tumors, and all had intact expression, consistent with the MSIsensor score. Number of mutations, MSIsensor score, tumor mutation burden, age at diagnosis, and presence of mutation in the PI3K pathway were not associated with clinical benefit.

Figure 2: Tumor molecular profiling and immunofluorescence analysis of ovarian clear cell carcinomas (OCCCs) treated with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB).

A: Somatic mutations identified in OCCC using MSK-IMPACT targeted sequencing, including those with a durable clinical response (n = 4, green), and those without a durable clinical response (n = 12, navy). Only pathogenic mutations are shown. Genetic alterations are color-coded according to the legend. Indel, small insertion and deletion. TMB, tumor mutation burden.

B-C: Multiplex immunofluorescence analysis of tumor samples from Patient 3 (B) and Patient 10 (C), both of whom achieved a durable clinical benefit from ICB. Markers as indicated in the figures. CK, cytokeratin. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Four patients (3, 10, 11, and 12) experienced durable clinical benefit. Patient 3 was diagnosed at age 34 with stage IIIC cancer (Table 2). She underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy with carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel followed by interval cytoreductive surgery with suboptimal debulking. After progressing through 4 lines of treatment, she started treatment with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus CTLA-4 inhibitor. Her tumor harbored alterations in PIK3CA, ARID1A, and PTEN, as well as a pathogenic TSC2/BCL2L1 fusion. Multiplex immunohistochemistry of her tumor showed numerous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) positive for PD-1 expression and low levels of PD-L1 expression predominantly localized to TIL-rich areas (Figure 2B). She completed 4 doses of the immunotherapy combination and remained on anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatment for 329 days prior to radiographically confirmed progression. Time to treatment failure was 358 days. She then progressed through 4 additional lines of cytotoxic treatment before death 24 months later.

Patient 10 was diagnosed with stage IIIB cancer at 47 years. She underwent primary cytoreductive surgery with optimal debulking followed by adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel (Table 2). After progression, she was started on a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus CTLA-4 inhibitor combination. Her tumor harbored pathogenic PIK3CA, ARID1A, and NOTCH2 mutations (Figure 2A). Multiplex immunohistochemistry revealed TILs positive for PD-1 and low levels of PD-L1 expression predominantly localized to TIL-rich areas (Figure 2C). She experienced a partial response to combination therapy and remained on PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor maintenance for 429 days until progression. She was then restarted on a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus CTLA-4 inhibitor combination and received radiation to an isolated metastasis in a periportal lymph node. She remained on PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor maintenance for 61 days until the onset of biopsy-confirmed grade 4 immune-related hepatic injury. She was started on prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil with marked improvement in her transaminase, and was tapered off all immunosuppressive medications. Subsequent computed tomography (CT) scans showed a complete response, and she remained disease free for 30 months (time to treatment failure, 1,568 days) until a CT scan showed progression, after which she trialed two additional treatment regimens with progression. Approximately 1 year later she was restarted on treatment with the same anti–PD-1/PD-L1 plus anti–CTLA-4 regimen given her previous robust response as her hepatic function tests had normalized and her clinical trial options were limited. She achieved a complete response after 2 cycles; however, she again developed transaminitis and treatment was stopped after 21 days with no plan for subsequent therapy due to concern for recurrent immune-related hepatic injury. At the time of data censoring 6 months later, the patient had been off treatment and still had no evidence of disease.

Patient 11 had a germline biallelic BRCA1 mutation and was diagnosed with stage IV cancer at 54 years; she underwent cytoreductive surgery with suboptimal debulking (Table 2). She experienced 2 recurrences and was treated with 7 lines of therapy, including Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition, with poor response prior to starting a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor. She achieved a complete response with immunotherapy, with a time to treatment failure of 402 days before progression. Tumor molecular profiling showed a high tumor mutation burden of 13.2 mutations/megabase, a MSIsensor score of 0.24 (low), and somatic mutations affecting TP53 and the TERT promoter. No mutations in the PI3K pathway were identified (Figure 2A).

Patient 12 was diagnosed with stage IIIC cancer after presenting with a 20-cm pelvic mass, carcinomatosis, and ascites. Following biopsy of the omentum which confirmed carcinoma, she was started on neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 3 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel. She underwent cytoreductive surgery with optimal debulking; pathology revealed ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Germline testing did not show pathogenic mutations, and tumor molecular profiling demonstrated a low tumor mutation burden of 1.8 mutations/megabase and a pathogenic mutation in ARID1A, as well as amplifications in CKD12 and ERBB2 (Figure 2A). After surgery, she continued adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel but was switched to gemcitabine with carboplatin and bevacizumab due to progression after 3 cycles. This regimen was continued for a total of 7 cycles until radiographic progression. She was then started on treatment with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus CTLA-4 inhibitor. After 4 cycles, however, she presented to the emergency room with generalized muscle weakness. Laboratory testing demonstrated elevated C reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, with normal creatinine kinase and aldolase. She was given IV methylprednisolone and started on high-dose oral prednisone for grade 3 immune-related myositis with significant improvement in symptoms. CT scans after 4 cycles showed mixed response but was overall favorable. One month after her fourth cycle, she started maintenance PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition. She continued treatment over the next 9 months, with daily prednisone 10 mg and trimethoprim prophylaxis against opportunistic infections. Her PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment time at the time of censoring was 383 days, and imaging continued to show response.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Main Results

Given poor outcomes and chemotherapy resistance, finding effective therapies for advanced or recurrent clear cell carcinoma of the ovary is imperative. In this case series, we demonstrated a durable clinical benefit rate of 25% (4/16) with immunotherapy for ovarian clear cell histology; all 4 patients who responded had sustained response for over a year. Of note, a patient who achieved a durable complete response achieved a second complete response after disease recurrence and re-treatment with combination PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibition.

Results in the Context of Published Literature

We did not identify genetic alterations predictive of treatment response. A patient with a germline bi-allelic BRCA1 mutation had a tumor with high tumor mutation burden and was treated for 393 days with an eighth-line PD-1 inhibitor prior to progression. Although prior findings have not shown improved outcomes in patients with BRCA 1/2-mutated ovarian cancer treated with immunotherapy, our patient’s excellent response may be attributed to her high tumor mutation burden, or possibly to a sensitizing effect of prior PARP inhibition (15, 16). Three of the other responders had pathogenic somatic mutations in ARID1A, and 2 of the responders also had ERBB2 amplifications. Although the conclusions that can be drawn are limited by the small cohort, our data support other clinical and preclinical studies that have shown the potential role of ARID1A and HER2 alterations, as well as a clear cell carcinoma-specific gene signature, as biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade (17–22). Interestingly, the patient with a germline monoallelic PMS2 mutation had preserved PMS2 immunohistochemistry and low tumor mutation burden, suggesting the tumor was not driven by mismatch repair alteration.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry analysis of the tumor samples from 2 responders demonstrated abundant TILs and high levels of PD-1 expression (Figure 2B and C). As PD-1 expression has been shown to enrich for tumor antigen-reactive lymphocytes, it is likely that the tumors of the responders exhibited higher levels of intratumoral CD8+ TILs compared with non-responders (23, 24). Unfortunately, there was no available tissue from non-responders for multiplex analyses.

Compared to high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas, clear cell carcinomas have shown better response to immunotherapy (7, 9, 10, 25). However, in a randomized trial of nivolumab versus standard chemotherapy (NINJA) in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, no benefit was observed with nivolumab in the clear cell subgroup (n=67) (26). Given that the durable benefit in our cohort was predominantly observed in patients who received an anti–CTLA-4 plus anti–PD-1 combination, this approach may offer optimal therapeutic efficacy (27). Furthermore, as platinum chemotherapies induce T-cell proliferation and improve tumor recognition, some studies have suggested a potential benefit of immunotherapy with either concurrent or subsequent lines of platinum-based treatment (28–30). Future study in these areas is warranted.

Combinations with other targeted agents have also been suggested to potentially improve the efficacy of immunotherapy via immunomodulatory rather than direct cytotoxic effects. Of the four patients noted as have received “targeted” therapy, two had received folate receptor alpha tumor vaccine, one received multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and one received a histone deacetylase inhibitor. While none of these patients exhibited clinical benefit on our study, there is nevertheless a rationale for exploration of additional targeted agents to overcome the inherent tumor microenvironment resistance to immunotherapy.

Strengths and Weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first case series to report specifically on the outcomes of patients with clear cell carcinoma treated with immunotherapy. A limitation of our study is that it is a single institution study with a small cohort size. A collaborative effort to collect real world data on treatment information and prognostic factors would certainly be of interest. Another limitation is that 5 of 16 patients underwent <30 days of treatment before discontinuing for symptomatic progression. Of these, 4 died within 2 months. This rapid deterioration suggests the regimen may have been chosen late in their treatment course. As immunotherapies require time to achieve therapeutic effect, a treatment of <30 days may not be sufficient to achieve a response in patients at risk for symptomatic clinical progression, making it challenging to evaluate the true efficacy of these agents (31). Although our cohort is small, the findings regarding tumor molecular profiling, microenvironment analysis, clinical characteristics, and treatment details have generated hypotheses for exploration in larger cohorts.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

Larger case series that incorporate information regarding tumor molecular profiling and microenvironment are needed to identify patients who may benefit from immunotherapy. Our findings suggest that immunotherapy can result in durable clinical benefit in some patients with ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Further investigation of treatment combinations and predictors of response is warranted.

We eagerly await the results of clinical trials investigating the efficacy of immunotherapy in ovarian clear cell carcinoma, including the MOCCA study, which is studying durvalumab compared to standard chemotherapy in recurrent ovarian clear cell carcinoma (NCT02879162), the BrUOG 354 study, which compares nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in ovarian and extra-renal clear cell carcinomas (NCT03355976), and more recently EON, a study of etigilimab with nivolumab in patients with platinum resistant OCCC (NCT05026606).

CONCLUSION

In this case series of 16 patients with ovarian clear cell carcinoma, treatment with immunotherapy resulted in a clinical benefit rate of 25% with all responses lasting over one year, suggesting a potential role for immune checkpoint blockade in select patients with this histology. However, additional investigation into treatment combinations and biomarkers to predict response is needed to guide therapeutic decisions.

Highlights:

Four (25%) of 16 patients experienced a durable clinical benefit, defined as time to treatment failure of ≥180 days

No clearly identified biomarkers were predictive of response, although sample size was small

One patient was treated twice with an immune checkpoint inhibitor and had a complete response to treatment both times

What is already known on this topic: Subset analyses from clinical trials in ovarian cancer have suggested that immune checkpoint blockade may offer superior benefit to patients with clear cell carcinoma histology.

What this study adds – This is the first case series to report specifically on the outcomes of patients with ovarian clear cell carcinoma treated with immunotherapy. We demonstrate a durable clinical benefit rate of 25%, with all responses lasting over one year.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy – Although response rates of ovarian cancer to immune checkpoint blockade have thus far been limited, our study suggests a potential role in clear cell carcinoma, though further investigation of treatment combinations and predictors of response is necessary.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant P30 CA008748. D.Z. is supported by the Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation Liz Tilberis Award and the Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Academy (OC150111). B.W. is supported in part by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and Cycle for Survival grants. C.F.F. is supported by SU2C Convergence 2.0.

Funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Disclosure statement

D.Z. reports institutional grants from Genentech, AstraZeneca, and Plexxikon, as well as personal fees from Genentech, AstraZeneca, Xencor, Memgen, Takeda, Synthekine, Immunos, and Calidi Biotherapeutics, outside of the submitted work. D.Z. is also an inventor on a patent related to the use of oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus for cancer therapy. He is also a member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at MSK. B.W. reports ad hoc membership of the Scientific Advisory Board of Repare Therapeutics. Y.L.L. reports research funding from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and REPARE therapeutics, outside of the submitted work. C.F.F. reports institutional funding from Merck, Daiichi, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb; personal consulting fees from Seagen and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and Scientific Advisory Board participation for Merck and Genentech (compensation waived), outside of the submitted work. The remaining authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Korenaga TR, Ward KK, Saenz C, McHale MT, Plaxe S. The elevated risk of ovarian clear cell carcinoma among Asian Pacific Islander women in the United States is not affected by birthplace. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157(1):62–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anglesio MS, Carey MS, Köbel M, MacKay H, Huntsman DG. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: A report from the first Ovarian Clear Cell Symposium, June 24th, 2010. Gynecologic Oncology. 2011;121(2):407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anglesio MS, Papadopoulos N, Ayhan A, Nazeran TM, Noë M, Horlings HM, et al. Cancer-Associated Mutations in Endometriosis without Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(19):1835–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itamochi H, Kigawa J, Sugiyama T, Kikuchi Y, Suzuki M, Terakawa N. Low proliferation activity may be associated with chemoresistance in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oseledchyk A, Leitao MM Jr., Konner J, O’Cearbhaill RE, Zamarin D, Sonoda Y, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage I endometrioid or clear cell ovarian cancer in the platinum era: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cohort Study, 2000–2013. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(12):2985–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takano M, Sugiyama T, Yaegashi N, Sakuma M, Suzuki M, Saga Y, et al. Low response rate of second-line chemotherapy for recurrent or refractory clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a retrospective Japan Clear Cell Carcinoma Study. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 2008;18(5):937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamarin D, Burger RA, Sill MW, Powell DJ Jr., Lankes HA, Feldman MD, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Nivolumab Versus Nivolumab and Ipilimumab for Recurrent or Persistent Ovarian Cancer: An NRG Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(16):1814–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, Gimotty PA, Massobrio M, Regnani G, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(3):203–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disis ML, Taylor MH, Kelly K, Beck JT, Gordon M, Moore KM, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Avelumab for Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Ovarian Cancer: Phase 1b Results From the JAVELIN Solid Tumor Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(3):393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matulonis UA, Shapira-Frommer R, Santin AD, Lisyanskaya AS, Pignata S, Vergote I, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-100 study. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1080–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James FR, Jiminez-Linan M, Alsop J, Mack M, Song H, Brenton JD, et al. Association between tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, histotype and clinical outcome in epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prat J Staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2014;124(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):703–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Middha S, Zhang L, Nafa K, Jayakumaran G, Wong D, Kim HR, et al. Reliable Pan-Cancer Microsatellite Instability Assessment by Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Data. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu YL, Selenica P, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Callahan M, Feit NZ, et al. BRCA Mutations, Homologous DNA Repair Deficiency, Tumor Mutational Burden, and Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4:PO.20.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konstantinopoulos PA, Waggoner S, Vidal GA, Mita M, Moroney JW, Holloway R, et al. Single-Arm Phases 1 and 2 Trial of Niraparib in Combination With Pembrolizumab in Patients With Recurrent Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Carcinoma. JAMA oncology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura R, Kato S, Lee S, Jimenez RE, Sicklick JK, Kurzrock R. ARID1A alterations function as a biomarker for longer progression-free survival after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Qu J, Zhou N, Hou H, Jiang M, Zhang X. Effect and biomarker of immune checkpoint blockade therapy for ARID1A deficiency cancers. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020;130:110626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang T, Chen X, Su C, Ren S, Zhou C. Pan-cancer analysis of ARID1A Alterations as Biomarkers for Immunotherapy Outcomes. Journal of Cancer. 2020;11(4):776–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasniqi E, Barchiesi G, Pizzuti L, Mazzotta M, Venuti A, Maugeri-Saccà M, et al. Immunotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: state of the art and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janjigian YY, Maron SB, Chatila WK, Millang B, Chavan SS, Alterman C, et al. First-line pembrolizumab and trastuzumab in HER2-positive oesophageal, gastric, or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):821–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami R, Hamanishi J, Brown JB, Abiko K, Yamanoi K, Taki M, et al. Combination of gene set signatures correlates with response to nivolumab in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duraiswamy J, Turrini R, Minasyan A, Barras D, Crespo I, Grimm AJ, et al. Myeloid antigen-presenting cell niches sustain antitumor T cells and license PD-1 blockade via CD28 costimulation. Cancer Cell. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sue-A-Quan R, Patel PG, Shakfa N, Nyi M-PN, Afriyie-Asante A, Kang EY, et al. Prognostic significance of T cells, PD-L1 immune checkpoint and tumour associated macrophages in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecologic Oncology. 2021;162(2):421–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Ikeda T, Minami M, Kawaguchi A, Murayama T, et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of Anti-PD-1 Antibody, Nivolumab, in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(34):4015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamanishi J, Takeshima N, Katsumata N, Ushijima K, Kimura T, Takeuchi S, et al. Nivolumab Versus Gemcitabine or Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin for Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer: Open-Label, Randomized Trial in Japan (NINJA). Journal of Clinical Oncology.0(0):JCO.21.00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu YL, Zamarin D. Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade Strategies to Maximize Immune Response in Gynecological Cancers. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018;20(12):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao JB, Gwin WR, Urban RR, Hitchcock-Bernhardt KM, Coveler AL, Higgins DM, et al. Pembrolizumab with low-dose carboplatin for recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer: survival and immune correlates. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu YL, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Emengo VN, Friedman C, Konner JA, et al. Subsequent therapies and survival after immunotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;155(1):51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamarin D, Walderich S, Holland A, Zhou Q, Iasonos AE, Torrisi JM, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and clinical efficacy of durvalumab in combination with folate receptor alpha vaccine TPIV200 in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a phase II trial. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boland JL, Zhou Q, Martin M, Callahan MK, Konner J, O’Cearbhaill RE, et al. Early disease progression and treatment discontinuation in patients with advanced ovarian cancer receiving immune checkpoint blockade. Gynecologic oncology. 2019;152(2):251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]