Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study is to examine the amount of the total variance of the subjective well-being (SWB) of psychotherapists from 12 European countries explained by between-country vs. between-person differences regarding its cognitive (life satisfaction) and affective components (positive affect [PA] and negative affect [NA]). Second, we explored a link between the SWB and their personal (self-efficacy) and social resources (social support) after controlling for sociodemographics, work characteristics, and COVID-19-related distress.

Methods

In total, 2915 psychotherapists from 12 countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Great Britain, Serbia, Spain, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and Switzerland) participated in this study. The participants completed the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form (I-PANAS-SF), the General Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

Results

Cognitive well-being (CWB; satisfaction with life) was a more country-dependent component of SWB than affective well-being (AWB). Consequently, at the individual level, significant correlates were found only for AWB but not for CWB. Higher AWB was linked to being female, older age, higher weekly workload, and lower COVID-19-related distress. Self-efficacy and social support explained AWB only, including their main effects and the moderating effect of self-efficacy.

Conclusions

The results highlight more individual characteristics of AWB compared to CWB, with a more critical role of low self-efficacy for the link between social support and PA rather than NA. This finding suggests the need for greater self-care among psychotherapists regarding their AWB and the more complex conditions underlying their CWB.

Keywords: Well-being, Psychotherapist, Perceived social support, Self-efficacy, Cross-cultural comparison, COVID-19

The issue of psychological health and well-being of psychotherapists is a highly understudied research topic in psychotherapy and clinical psychology, which have traditionally focused almost exclusively on the clients of psychotherapy rather than the psychotherapists themselves (Laverdière et al., 2018; 2019). However, providing psychotherapy is related to multidimensional psychological distress and a constant requirement for empathy, which all pose a significant risk of emotional problems among psychotherapists (e.g., Raquepaw and Miller, 1989; Rosenberg and Pace, 2006; Rupert and Morgan, 2005; Rzeszutek and Schier, 2014). Until now, previous research has focused more on the negative aspects of psychotherapists' mental health (i.e., psychotherapists’ burnout; see systematic reviews: Lee et al., 2020; Simionato and Simpson, 2018); however, far fewer studies have examined the problem of psychological well-being among psychotherapists (Brugnera et al., 2020; Laverdière et al., 2018, 2019). In other words, while there is relatively high empirical evidence on the negative mental consequences of the psychotherapy occupation, little is known about how psychotherapists can enhance their well-being and quality of life. It is somewhat surprising that this last topic is still so neglected because previous systematic reviews have highlighted that clients choose to work with psychotherapists who they perceive as psychologically healthy and satisfied with their own lives (Lambert and Barley, 2001; Wogan and Norcross, 1985). Conversely, several studies have shown that a low quality of life among psychotherapists could deteriorate the therapeutic alliance and the entire therapeutic process (Enochs and Etzbach, 2004; Holmqvist and Jeanneau, 2006). The aforementioned issues are especially vital in light of the COVID-19 pandemic when psychotherapists were forced to tackle many new challenges regarding their therapeutic practice (Brillon et al., 2021). COVID-19 distress and related obstacles evoked high levels of depression and anxiety in this specific sample, which significantly deteriorated their personal well-being (Brillon et al., 2021). In this study, we explore the relationship between social support and the subjective well-being of psychotherapists from 12 European countries in the COVID-19 pandemic and the possible moderating effect of self-efficacy on that association.

A large body of empirical evidence exists on how social support exerts its mitigating effect on stressful events and enhances individual well-being in the general population (Cohen and Wills, 1985; Schwarzer and Knoll, 2007), in the clinical samples (Wang et al., 2021), and in the special case of occupational stress (Łuszczynska and Cieslak, 2005). In particular, although previous studies have observed the main and buffering effects of social support in stress adaptation, these findings are full of inconsistencies, especially regarding the buffering mechanism of perceived support (Gleason et al., 2008; Łuszczynska and Cieslak, 2005). For example, Gleason et al. (2008) described the phenomenon of the mixed blessing of receiving support, when receiving support can sometimes have a detrimental impact on the well-being under stress, as it may create feelings of guilt, dependency, or inefficiency in the support's recipient. Several authors claim that the reason for such inconsistent results is still the relative lack of studies on personal moderators in the social support-stress association (e.g., Łuszczynska et al., 2011; Stetz et al., 2006). In the current study, we focused on the cognitive personal moderator, which is self-efficacy (Łuszczynska et al., 2005).

Psychological studies on protective factors against work-related stress focused solely at first on the work environment (e.g., organizational structure, type of management) or on the stable individual characteristics of employees (e.g., age, personality; see review and meta-analysis by Alarcon et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013). However, the aforementioned variables are usually difficult to change; thus, in the next period, researchers concentrated on more modifiable individual features of workers, including cognitive coping with work-related stress (Shoji et al., 2016). One of the widely explored concepts within that field of study is self-efficacy, which the father of this construct defined as a person's beliefs in his or her ability to have control over challenging demands (Bandura, 1997). In terms of occupational stress, self-efficacy is conceptualized as the individual confidence that one has the skills to cope with specific work-related tasks, work-related challenges, and the accompanying stress and its consequences (Shoji et al., 2016). Some authors have observed that self-efficacy may act as a personal resource against work-related stress and strain (e.g., Hahn et al., 2011) and mitigate the process of employees' adaptation to organizational changes and conflicts within it (Unsworth and Mason, 2012). Self-efficacy can be assessed as either a domain-specific term or a general (global) construct (Łuszczynska et al., 2005). In our study, we followed this latter approach, as it enables us to measure this construct in the process of general stress adaptation and to better capture its possible interaction effects with other variables (Łuszczynska et al., 2005).

One of the still unresolved research questions is the mutual relationship between social support and self-efficacy in enhancing well-being under stress (Carmeli et al., 2020; Hohl et al., 2016). In other words, it is not entirely known whether, in this process, those constructs mutually reinforce each other or compensate for deficiencies in one resource to another. Initially, social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997) suggests two potential interactions of these resources, known as synergistic versus compensation effects (e.g., Dishman et al., 2009; Warner et al., 2011). On the one hand, the synergistic effect highlights that the interaction of social support and self-efficacy may have a stronger effect on well-being than each of them separately. For example, if a higher level of social support is positively related to well-being at all levels of self-efficacy, but at the same time, this effect is stronger for higher levels of self-efficacy, and we have a synergistic effect. On the contrary, when an interaction of these two constructs is significant only if one of them is at a low intensity, we have a compensatory effect. For example, if I am low in self-efficacy, I may profit emotionally much more from receiving support compared to when I am high in this cognitive resource and I rely only on my own abilities, so receiving support could be an admission of weakness for me (Warner et al., 2011).

In this study, we assumed that the aforementioned effects could differ depending on the subjective well-being (SWB) components we measured, i.e., cognitive well-being (CWB; life satisfaction) versus affective well-being (AWB; positive affect [PA] and negative affect [NA]). According to the classic definition, SWB is operationalized as people's satisfaction with their lives as a whole or with the individual domains of their lives and includes two main components: satisfaction with life, which is the cognitive aspect of subjective well-being (CWB), and affective well-being (AWB), i.e., positive and negative emotional reactions to peoples' lives (Diener et al., 1985, 2016). It has been proved that high levels of SWB are related to good health, longevity, and optimal human functioning (Fredrickson, 2013; Steptoe et al., 2015). Several authors have found that these two elements are associated, but separable constructs, especially regarding their temporal stability, various predictors, and different backgrounds (Eid and Diener, 2004; Kaczmarek et al., 2015; Luhmann et al., 2012a). More specifically, it has been proven that CWB is relatively stable throughout a person's entire life, but also depends mostly on external circumstances (e.g., income, job status, current life situation; see Diener et al., 2016; Lyubomirsky, 2011). In other words, between-country differences (see e.g. economic situation) may significantly impact the level of CWB between study participants. On the other hand, AWB is a much more dynamic state and is highly person-dependent, usually rooted in individual personality differences (e.g., Schimmack et al., 2002; Steel et al., 2008). Thus, in this cross-cultural study, these two SWB components may reveal various levels of country-versus intrapersonal sources of variance among psychotherapists as well as their different associations with social support and self-efficacy (synergistic versus compensation effect).

Present study

The aim of this study was twofold. First, we examined how much of the total variance of subjective well-being (SWB) of psychotherapists from 12 European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic was explained by between-country differences when we compared cognitive well-being (CWB; life satisfaction) and AWB (PA and NA). Second, at the individual level, we examined the relationship between SWB and personal (self-efficacy) and social resources (perceived social support). In particular, we tested a moderating effect (synergistic vs. compensatory) of self-efficacy on the social support–SWB association to explore whether this effect is different for the SWB components. We implemented a multilevel approach to reflect the fact that the psychotherapists were nested in the national samples. Thus, we focused on the relationships at the individual level (Level 1) after adjusting for between-country differences in the variables under study (Level 2). We also controlled the results for sociodemographic, work-related characteristics, and COVID-19-related distress. To the best of our knowledge, there is no cross-cultural research on the abovementioned issues in a specific sample of psychotherapists. Thus, our study is mainly explorative, but we formulated at least two directional hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

In the case of the CWB, there would be high between-country differences among the participants.

Hypothesis 2

In the case of the AWB, there would be high between-people differences among the participants.

Hypothesis 3

A moderating effect of self-efficacy would be observed on its relationship with perceived social support, for both SWB components (CWB and AWB). The synergistic vs. compensatory character of this effect is a subject of exploration.

Methods

Participants

In our cross-cultural survey, we used standardized questionnaires in an online format (see below) using a specialized online platform to interview psychotherapists from 12 European countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Great Britain, Serbia, Spain, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and Switzerland. The process of gathering data in all these countries took place between June 2020 and June 2021 during the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. The online questionnaires were sent to the professional psychotherapeutic associations of various therapeutic modalities in each country and distributed among their members.

A total of 2915 psychotherapists from 12 countries representing various psychotherapeutic modalities agreed to participate in this study. The eligibility criteria included certification (or being in the process of certification) in a particular psychotherapeutic school and practice for at least one year. The study participants filled out the online versions of the questionnaire, along with detailed sociodemographic and work-related questions. In the first part of the survey, we also asked participants how the COVID-19 pandemic had influenced their practice and to what extent they suffered from COVID-19-related psychological distress. In each country, participating in the research was anonymous and voluntary, and the participants received no remuneration. The overall study protocol was accepted by the ethics committee of the Polish coauthors of this study. Below, detailed sociodemographic, work-related data and data on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on therapeutic practice among psychotherapists in all countries are presented.

According to the above-mentioned tables, we see that age distributions were similar among all countries (mean range = 37–53 years). In all countries, female psychotherapists were overrepresented (83%) when compared to male participants. The majority of participants declared being in some form of stable relationship (n = 75%). Also, the majority of psychotherapists held psychology degrees and worked with adult clients. Working in a private workplace was also characteristic of most of the psychotherapists. Furthermore, most of the psychotherapists ran a psychotherapy service and submitted their work for supervision at least once a month. However, the majority of Spanish therapists did not employ supervision at all, whereas Austrian psychotherapists used it on a quarterly basis. The therapeutic modalities were distributed differently in all the included countries. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy appeared to be the more common therapeutic approach in Cyprus, Spain, Poland, and Romania, while psychodynamic therapy was mostly prevalent in Bulgaria, Norway, and Sweden. In Austria and Switzerland, Gestalt therapy was used most by the participants, and integrative psychotherapy was mostly mentioned by psychotherapists in the United Kingdom. Years of experience varied from an average of eight years in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Poland, Romania, and Serbia to 10–16 years in Austria, Finland, Spain, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The usual weekly workload ranged from a couple of hours a week to more than 20 h a week. More specifically, in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Romania, and Serbia, the weekly workload ranged from one to 10 h. The typical workweek in Sweden and the United Kingdom was between 10 and 20 h. The latter two workload categories were equally distributed among Austrian, Spanish, and Swiss psychotherapists. Finland, Norway, and Poland had the most psychotherapists who worked more than 20 h each week. Last but not least, there was a widespread tendency to work partially online during the COVID-19 epidemic, and this was the case for psychotherapists in 11 different nations (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Spain, Norway, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Switzerland, and Sweden). The majority of UK therapists were still exclusively offering their services online at the time of data collection.

Measures

Below, we present the study questionnaires that were adapted for all countries and presented to the participants in their native language versions.

Life satisfaction was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985). The SWLS is an internationally renowned tool to assess cognitive aspects of SWB and consists of five items, each assessed on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree; e.g. In most ways my life is close to my ideal; The conditions of my life are excellent; I am satisfied with my life). A higher total score indicates a higher level of life satisfaction. The Cronbach coefficients for the SWLS in all 12 countries varied from 0.84 in the English version to 0.89 in the Norwegian and Bulgarian versions.

PA and NA were assessed using the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form (I-PANAS-SF; Thompson, 2007). The I-PANAS-SF consists of 10 items derived from the original 20-item PANAS questionnaire (Watson et al., 1988). The five PA items were active, determined, attentive, inspired, and alert. The five negative items were afraid, nervous, upset, hostile, and ashamed. Participants were asked to rate these adjectives, depending on the extent to which each one depicted the way they had felt generally during the last month. The Cronbach coefficients for the I-PANAS-F in all 12 countries varied for PA from .68 in the Spanish version to 0.77 in the Finnish version, and for NA from 0.66 in the Austrian version to 0.80 in the Serbian version.

To examine the participants’ level of self-efficacy, we chose the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES; Schwarzer and Jerusalem, 1995), which is a well-known 10-item tool to measure the general (global) construct of self-efficacy. Respondents rate various statements on a 4-point Likert scale (from NO to YES), and the global index of self-efficacy is obtained as the sum of all items. GSES, the most popular questionnaire to assess this cognitive resource, has been adapted in nearly 28 nations (Łuszczynska et al., 2005). The Cronbach coefficients for the GSES in all 12 countries varied from 0.82 in the Spanish version to .93 in the Norwegian version.

Social support was evaluated using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1990). The MSPSS is a 12-item questionnaire created to measure perceived social support from three sources: family, friends, and a significant other, as well as the total support level. In our study, we followed the total support index. Participants rated several sentences on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The MSPSS is also an internationally renowned tool for assessing various aspects of perceived social support. The Cronbach coefficients for the total support scale in all 12 countries varied from 0.93 in the Polish and Swiss versions to 0.97 in the Cyprian version.

Data analysis

Multilevel analysis was performed to reflect a two-level data structure: persons (i.e., 2915 psychotherapists) nested in 12 European countries (Bryk and Raudenbush, 2002). The separate models were tested for the cognitive and two affective components of the SWB. The level 1 variable was individual scores centered on the group mean, which in this case is the mean for a given country. The level 2 variables were means for each country centered on the grand mean, which is an average across all countries for a given variable (Enders and Tofighi, 2007).

To verify Hypotheses 1 and 2, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated based on an unconditional model to obtain the amount of overall variance in SWB explained by a grouping variable (i.e., country; Gelman and Hill, 2007).

Next, to examine the interaction assumed in Hypothesis 3, variables were introduced into the models in four steps. In the first step, sociodemographic, and work-related characteristics and COVID-19-related distress were added. Continuous variables were centered on the group mean (e.g., age, work experience, and pandemic-related stress), and categorical variables were dummy-coded (sex: female = 0, male = 1; relationship status: single = 0, in a stable relationship = 1; weekly workload: 0 = less than 20 h, 1 = 20 h and more; supervision: 0 = quarterly or less, 1 = once a month or more). The second step introduced level 1 self-efficacy and perceived social support, and the third step introduced level 2 values of these variables to control for possible between-country differences. The fourth step brought in the level 1 interaction of self-efficacy x social support. Simple slope analyses were conducted using the calculation tools provided by Preacher et al. (2006).

For random effects, the covariance structure of the variance components (VC) was assumed. The maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method was used, and all statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27. This paper presents only the resultant models.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. As can be seen, countries differ in terms of the average values of SWB components. Fig. 1 shows that the dispersion of these differences is larger for CWB than for AWB. Accordingly, ICC indicates that for CWB, as many as 53.7% of the total variance is explained by between-country differences. The analogical values for AWB were much lower and equal to 12.8% and 8.9% for PA and NA, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the studied variables among the sample of psychotherapists (N = 2915) according to country of origin.

| Country | n | Mean | SD | Range | Kurtosis | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Life | ||||||

| Austria | 151 | 27.66 | 4.82 | 16–35 | −0.76 | −0.14 |

| Bulgaria | 217 | 14.24 | 5.60 | 5–33 | 0.80 | 0.43 |

| Cyprus | 202 | 24.31 | 5.73 | 8–35 | −0.51 | −0.24 |

| Finland | 254 | 25.53 | 5.23 | 5–35 | −0.99 | 1.53 |

| Norway | 225 | 24.72 | 5.44 | 5–35 | −0.81 | 1.02 |

| Poland | 340 | 24.49 | 4.34 | 5–35 | −0.42 | 0.91 |

| Romania | 202 | 12.67 | 4.60 | 5–29 | 1.01 | 1.26 |

| Serbia | 237 | 14.34 | 4.72 | 5–30 | 0.51 | 0.31 |

| Spain | 320 | 14.51 | 5.57 | 5–33 | 0.81 | 0.38 |

| Sweden | 275 | 24.07 | 5.86 | 5–35 | −0.75 | 0.23 |

| Switzerland | 205 | 28.01 | 4.50 | 12–35 | −1.08 | 1.16 |

| United Kingdom | 287 | 16.12 | 6.06 | 5–34 | 0.66 | −0.25 |

| Positive affect | ||||||

| Austria | 151 | 16.03 | 3.27 | 6–25 | −0.25 | 0.09 |

| Bulgaria | 217 | 16.16 | 2.80 | 5–23 | −0.09 | 0.66 |

| Cyprus | 202 | 16.32 | 2.76 | 5–22 | −0.44 | 0.69 |

| Finland | 254 | 17.14 | 2.70 | 10–24 | −0.18 | 0.07 |

| Norway | 225 | 14.40 | 2.43 | 5–20 | −0.53 | 1.07 |

| Poland | 340 | 15.90 | 2.91 | 8–25 | −0.19 | 0.00 |

| Romania | 202 | 16.27 | 2.93 | 5–25 | −0.36 | 2.09 |

| Serbia | 237 | 19.35 | 2.31 | 12–25 | −0.25 | 0.37 |

| Spain | 320 | 16.85 | 2.70 | 9–24 | −0.10 | −0.14 |

| Sweden | 275 | 15.44 | 2.81 | 7–22 | −0.08 | −0.23 |

| Switzerland | 205 | 15.96 | 3.02 | 9–24 | 0.10 | −0.12 |

| United Kingdom | 287 | 16.31 | 3.62 | 7–25 | 0.05 | −0.24 |

| Negative affect | ||||||

| Austria | 151 | 8.76 | 2.06 | 5–15 | 0.97 | 1.30 |

| Bulgaria | 217 | 14.24 | 5.60 | 5–33 | 0.80 | 0.43 |

| Cyprus | 202 | 24.31 | 5.73 | 8–35 | −0.51 | −0.24 |

| Finland | 254 | 8.58 | 1.72 | 5–13 | −0.06 | −0.41 |

| Norway | 225 | 8.78 | 2.27 | 5–20 | 1.20 | 3.78 |

| Poland | 340 | 10.92 | 2.57 | 6–22 | 0.73 | 0.76 |

| Romania | 202 | 9.42 | 2.68 | 5–20 | 1.40 | 3.46 |

| Serbia | 237 | 11.15 | 3.07 | 5–20 | 0.40 | −0.26 |

| Spain | 320 | 8.84 | 2.75 | 5–21 | 1.38 | 2.13 |

| Sweden | 275 | 8.94 | 2.33 | 5–16 | 0.77 | 0.40 |

| Switzerland | 205 | 9.03 | 2.09 | 5–14 | 0.37 | −0.19 |

| United Kingdom | 287 | 9.35 | 2.89 | 5–23 | 1.08 | 1.54 |

| General self-efficacy | ||||||

| Austria | 151 | 30.42 | 5.13 | 15–40 | −0.55 | 0.42 |

| Bulgaria | 217 | 29.43 | 5.00 | 10–40 | −0.90 | 1.97 |

| Cyprus | 202 | 30.04 | 5.12 | 10–40 | −0.58 | 1.31 |

| Finland | 254 | 31.10 | 4.20 | 15–40 | −0.72 | 1.74 |

| Norway | 225 | 30.19 | 5.87 | 10–48 | −0.36 | 0.38 |

| Poland | 340 | 31.13 | 3.61 | 18–40 | 0.21 | 0.68 |

| Romania | 202 | 32.76 | 4.54 | 10–40 | −1.45 | 5.69 |

| Serbia | 237 | 32.91 | 4.27 | 20–40 | −0.43 | −0.11 |

| Spain | 320 | 32.20 | 3.83 | 22–40 | 0.09 | −0.44 |

| Sweden | 275 | 29.50 | 3.76 | 17–40 | −0.46 | 1.06 |

| Switzerland | 205 | 31.07 | 3.68 | 22–40 | 0.30 | −0.10 |

| United Kingdom | 287 | 30.63 | 3.55 | 19–40 | 0.35 | 0.63 |

| Social Support | ||||||

| Austria | 151 | 65.46 | 18.11 | 15–84 | −1.15 | 0.34 |

| Bulgaria | 217 | 65.70 | 16.16 | 12–84 | −1.36 | 1.16 |

| Cyprus | 202 | 66.09 | 17.24 | 21–84 | −1.09 | 0.03 |

| Finland | 254 | 67.65 | 15.37 | 12–84 | −1.15 | 0.63 |

| Norway | 225 | 66.28 | 15.71 | 12–84 | −1.03 | 0.28 |

| Poland | 340 | 67.98 | 12.18 | 12–84 | −1.54 | 3.80 |

| Romania | 202 | 72.64 | 11.83 | 12–84 | −2.04 | 5.61 |

| Serbia | 237 | 69.84 | 14.74 | 26–84 | −1.41 | 1.15 |

| Spain | 320 | 69.67 | 12.40 | 12–84 | −1.23 | 1.94 |

| Sweden | 275 | 68.55 | 15.21 | 12–84 | −1.19 | 0.82 |

| Switzerland | 205 | 70.96 | 11.11 | 13–84 | −1.51 | 4.12 |

| United Kingdom | 287 | 62.76 | 14.49 | 12–84 | −0.76 | 0.20 |

Fig. 1.

Country averages in subjective well-being: a) life satisfaction, b) positive affect and c) negative affect. The dotted lines depict grand means.

Multilevel analysis showed that both self-efficacy and perceived social support and their interaction were not significant for CWB. By contrast, for AWB, self-efficacy and social support were independently associated with higher PA and lower NA. A moderating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between AWB and social support was also noted for both valences. Table 2 presents these results.

Table 2.

Results of multilevel analysis of subjective well-being among psychotherapists (level 1, N = 2915) from 12 countries (level 2).

| SWL |

PA |

NA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | ||||

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 20.30 | (1.43)*** | 16.05 | (0.31)*** | 9.58 | (0.23)*** |

| Level 1 control variables | ||||||

| Sex | 0.39 | (0.27) | −0.27 | (0.14)** | −0.01 | (0.11) |

| Relationship status | 0.44 | (0.24) | 0.16 | (0.12) | −0.13 | (0.10) |

| Age | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.03 | (0.01)*** | −0.05 | (0.01)*** |

| Work experience | −0.01 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.01) | −0.00 | (0.01) |

| Weekly workload | −0.17 | (0.22) | 0.19 | (0.11) | −0.24 | (0.09)** |

| Supervision | 0.40 | (0.23) | 0.1 | (0.12) | 0.10 | (0.10) |

| COVID-19-related distress | 0.09 | (0.10) | −0.18 | (0.05)*** | 0.72 | (0.04)*** |

| Level 1 variables | ||||||

| Self-efficacyw | 0.04 | (0.03) | 0.17 | (0.01)*** | −0.12 | (0.01)*** |

| Social supportw | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.00)** | −0.01 | (0.00)*** |

| Level 2 variables | ||||||

| Self-efficacyb | −3.27 | (1.58) | 0.87 | (0.28)** | 0.32 | (0.24) |

| Social supportb | 0.56 | (0.72) | −0.13 | (0.12) | −0.05 | (0.10) |

| Level 1 interaction | ||||||

| Self-efficacyw* Social supportw | −0.001 | (0.001) | 0.002 | (0.001)*** | −0.003 | (0.000)*** |

| Random effects | ||||||

| Residual variance | 27.48 | (0.73)*** | 7.40 | (0.20)*** | 4.81 | (0.13)*** |

| Between-country variance | 23.65 | (9.71)** | 0.63 | (0.27)** | 0.48 | (0.20)** |

Note. ***p < .001, **p < .05, *p < .01; SWL = satisfaction with life, PA = positive affect, NA = negative affect, SE = standard error, indexes: w = within-country, b = between-country.

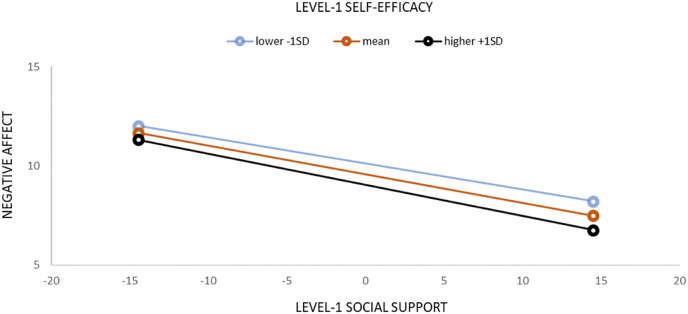

Further analysis of simple effects revealed slightly different patterns for PA and NA. As illustrated in Fig. 2 , for self-efficacy lower than the national sample average, the relationship between perceived social support and PA was insignificant (γ = 0.002, SE = 0.004, z = 0.55, p = .58), whereas for values equal to (γ = 0.011 SE = 0.004, z = 2.75, p = .006) or higher than the average (γ = 0.0197, SE = 0.005, z = 3.72, p < .001), this relationship was positive. These findings mean that higher perceived social support was related to higher PA at higher values of self-efficacy; thus, synergistic effects of these resources were observed, but present only in individuals with sufficiently high self-efficacy relative to their national sample average. Furthermore, as simple slopes were significant outside the region described with the following bounds (−13.64; −1.69) of self-efficacy, we identified a number of participants in each country for whom there was no significant relationship between social support and PA. Table 3 presents these results. The percentage is highest for Spain (41.3%) and lowest for Bulgaria (21.66%), with a value for the whole sample equal to 30.60%.

Fig. 2.

Simple slopes of moderating effect of self-efficacy on a relationship between perceived social support and positive affect: Level 1 interaction. Self-efficacy and social support were centered around the within-country means. Slopes are probed at a mean value of self-efficacy and one standard deviation above and below this mean.

Table 3.

Simple Slope Analysis of Self-Efficacy x Social Support on Positive Affect: Number and Percentage of Participants with Insignificant Simple Slopes.

| Country | Sample Size | Insignificant Simple Slopes |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of Sample Size | ||

| Austria | 151 | 38 | 25.17 |

| Bulgaria | 217 | 47 | 21.66 |

| Cyprus | 202 | 59 | 29.21 |

| Finland | 254 | 70 | 27.56 |

| Norway | 225 | 74 | 32.89 |

| Poland | 340 | 104 | 30.59 |

| Romania | 202 | 73 | 36.14 |

| Serbia | 237 | 94 | 39.66 |

| Spain | 320 | 132 | 41.25 |

| Switzerland | 205 | 74 | 36.10 |

| Sweden | 275 | 64 | 23.27 |

| United Kingdom | 287 | 63 | 21.95 |

| Total | 2915 | 892 | 30.60 |

Fig. 3 presents the results of the same analysis for NA. The simple slopes for perceived social support and NA are significant for all self-efficacy values, but the strength of this relationship becomes greater with higher self-efficacy values (for values lower than a national sample average γ = −0.131, SE = 0.003, z = −39.57, p < .001; for values equal to a national sample average γ = -0.144, SE = 0.003, z = −44.44, p < .001; for values higher than a national sample average γ = −0.157, SE = 0.004, z = −37.48, p < .001). Thus, in this case, a synergistic effect of these resources was observed across all the values of self-efficacy, which was confirmed by the fact that simple slopes are significant for all the participants (they are insignificant in a region between −67.19 and −37.42, which is outside the range of group-centered values of self-efficacy in our study).

Fig. 3.

Simple slopes of moderating effect of self-efficacy on a relationship between perceived social support and negative affect: Level 1 interaction. Self-efficacy and social support were centered around the within-country means. Slopes are probed at a mean value of self-efficacy and one standard deviation above and below this mean.

Additionally, notable differences across SWB components were found for the control variables. The CBW was independent of all the studied sociodemographic and work-related characteristics, as well as the self-reported distress due to the pandemic. For higher AWB, two variables were significant regardless of valence: older age and lower COVID-19-related distress. Two other variables were valence-specific covariates. Namely, for higher PA, being female was a significant correlate, whereas for lower NA, a significant correlate was higher than 20 h per week workload. Being in a stable intimate relationship, years of professional experience, and working under supervision were unrelated to SWB in the studied sample of psychotherapists.

Discussion

The results of our study were in accordance with our first two hypotheses, as we found that among psychotherapists, CWB was more country-dependent, while AWB was mostly related to individual characteristics. Specifically, we observed that nearly 54% of the total variance in life satisfaction was explained by belonging to national samples, compared to only about 13% of the overall variance in PA and 9% in NA. This finding may be treated as another argument for the distinctiveness of cognitive and affective components of SWB (e.g., Busseri and Sadava, 2011; Diener et al., 2016), as well as its potentially different background, which is dependent on shared external conditions in the case of life satisfaction and more individualized factors in the case of affect (Schimmack et al., 2002). The existing literature has provided various explanations for this phenomenon. Some authors have attributed these differences to measurement bias (i.e., time frames used to measure these two components), with a relatively short time perspective for affect, and a global, unspecified period of time for life satisfaction (Kim-Prieto et al., 2005). Other authors have highlighted the structural distinctions between the SWB components, which persist even when we control for the time frame of assessment (Diener et al., 2006; Luhmann et al., 2012a). Namely, life satisfaction deals with the global evaluation of life events, whereas AWB is based on the assessment of recent activities and events, which are much more dynamic and transient; as such, AWB reflects rather momentary well-being. The latter may explain why cognitive and affective components of SWB differ in their temporal stability and sensitivity to various major life events (Luhmann et al., 2012b). For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Luhmann et al. (2012b) revealed that critical life events, such as childbirth, divorce, or retirement, may have a much more powerful and persistent impact on cognitive SWB components in the long run compared to affective ones. The same deals with other external circumstances, such as changes in income, job status, or the current socio-economic situation in a particular country. Conversely, AWB is much more fluid and is rooted mostly in personality characteristics (Schimmack et al., 2002).

The above finding corresponds to the fact that, in our study, at the individual level, life satisfaction among psychotherapists from 12 countries was unrelated to all the analyzed psychological, sociodemographic, and work-related variables, including distress caused by the pandemic. It seems that this cognitive component of SWB is resistant and not susceptible to any of the assessed factors, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic. This null result may be an interesting adjunct to a still highly understudied topic, which is the psychological well-being of psychotherapists (Laverdière et al., 2018; 2019).

On the other hand, we found significant associations between the studied variables and AWB among our participants. Namely, better AWB was associated with sociodemographic data (being female, older age), some work-related characteristics (higher weekly workload), and lower experience of COVID-19 distress. Regarding participants' gender, some studies have found that male psychotherapists suffer more from work-related distress and are thus more vulnerable to burnout in this occupation compared to female psychotherapists (Rupert and Kent, 2007). It is often connected with sex differences in self-efficacy, which is usually higher among females working in helping professions (Purvanova and Muros, 2010). Regarding the participants’ age, our finding is in line with other, yet scarce, studies, which showed that older psychotherapists declare higher levels of well-being (Brugnera et al., 2020) and suffer less from burnout (Rupert and Kent, 2007) than their younger colleagues. In terms of workload, we found that workloads higher than 20 h per week were linked to less NA. We should take into account the specific period when this study was conducted, i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic, when, for many people, including psychotherapists (Brillon et al., 2021), staying professionally active could serve as a method of coping with chronic and uncontrollable conditions. However, we should also consider the other direction —people who were feeling better (less NA, higher PA) might be better able to work during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the COVID-19-related distress was significantly associated with low positive and high NA in this sample. The impact of this distress was revealed only in the case of the affective component of SWB, which indicates the limited consequences of the pandemic on the evaluation of individual SWL. Further research using a longitudinal design would help confirm this suggestion.

For AWB, we received partial confirmation of our last hypothesis. Namely, for both PA and NA, we found moderating effects of self-efficacy on their relationship with perceived social support in the form of a synergistic effect. In other words, a higher level of social support was positively related to AWB, but this effect was boosted by higher levels of self-efficacy (Dishman et al., 2009; Warner et al., 2011). Nevertheless, we also observed slight differences in this synergistic relationship for each valence. Namely, for PA, low self-efficacy negated the positive effect of perceived social support. Thus, if psychotherapists are low in self-efficacy within their national sample, their perception of social support is benign for PA. The likely mechanism is that such a person cannot effectively discount support from others for the maintenance of PA. Furthermore, this null effect was not equally distributed across the countries; therefore, it can be regarded as somehow country dependent. Conversely, in the case of NA, we observed a pure synergistic effect because social support was negatively related to NA at every level of self-efficacy, and this relationship was observed in all participants but with a different strength. Thus, in our study, individual self-efficacy was more critical for the association of perceived social support with PA than for NA. These results may add some new theoretical input to research on self-efficacy (Hohl et al., 2016; Shoji et al., 2016), especially in the context of its interplay with other individual resources. These results also point to the diverse mechanisms underlying the role of PA and NA in adaptation to stressful situations (Fredrickson, 2001).

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths, including a large international sample of psychotherapists from 12 different countries; the critical period of this research, i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic; and the multilevel methodological approach, which may all constitute a substantial contribution to the literature. Nevertheless, some limitations should be underscored. First, due to organizational obstacles, we could not properly control for psychotherapeutic modalities or work-related characteristics among the samples of our participants. In other words, these samples cannot be treated as representative samples of psychotherapists of the countries from which they are sampled, which is a common bias in studies on the psychological functioning of this professional group (Simionato and Simpson, 2018). Second, the cross-sectional design of our study prevented any causal inferences. Lastly, we cannot forget about the two typical biases in cross-cultural research: the reference group effect (Heine et al., 2002) and the response style effect (Van de Vijver and Leung, 1997). The first is associated with using familiar others as a benchmark for self-reported comparison; the latter is rooted in culture-related differences in response styles. Both of these biases can be reduced by a multilevel design and adequate centering of the variables, but only to some extent. It is therefore worth noting that the obtained results are not generalizable and are relative to the specificity of the national samples that participated in the study.

Conclusion

From a theoretical viewpoint, the results of our study call for more research in a multilevel design on the mechanisms and correlates of subjective well-being in various occupational settings (Bakker, 2015). This design offers much deeper insight than the most frequent single-level approach. Examining SWB predictors with the most valid representation of their real-life complex hierarchical structure may lead to more advanced knowledge of what is actually highly individualized and what depends on the nesting of the person in the overarching contexts of their functioning. This approach is crucial in cross-cultural comparisons, where a multilevel viewpoint has seldom been employed (Disabato et al., 2016). A wider context of being rooted in a given time and society can counterbalance the widespread study of resources only at the individual level (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

From a practical perspective, our findings highlight the possibility for greater effectiveness of self-care regarding the AWB of psychotherapists, which is much more dependent on intra- and external factors compared to their overall life satisfaction. Specifically, our results showed that, for AWB, self-efficacy acts synergistically with social support, with its low values undoing the positive effects of social support for PA. Thus, interventions to enhance this cognitive resource, popular in various work settings (e.g., Lloyd et al., 2017), could be tailored to this specific occupational group. In this way, our findings may add to a more in-depth discussion on the education and training of psychotherapists in the international context.

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization: Angelika Van Hoy, Marcin Rzeszutek

Data curation: Angelika Van Hoy, Marcin Rzeszutek, Małgorzata Pięta, Jose M. Mestre, Álvaro Rodríguez Mora, Nick Midgley, Joanna Omylinska-Thurston, Anna Dopierala, Fredrik Falkenström, Jennie Ferlin, Vera Gergov, Milica Lazić, Randi Ulberg, Jan Ivar Røssberg, Camellia Hancheva, Stanislava Stoyanova, Stefanie Schmidt, Ioana Podina, Nuno Ferreira, Antonios Kagialis, Henriette Löffler-Stastka

Formal analysis: Marcin Rzeszutek, Ewa Gruszczyńska

Methodology: Marcin Rzeszutek

Supervision: Marcin Rzeszutek

Writing – original draft: Marcin Rzeszutek, Ewa Gruszczyńska, Angelika Van Hoy

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the New Ideas of POB V project implemented within the scope of the “Excellence Initiative - Research University” Program, by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland (number PSP: 501-D125-20-5004310).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.07.065.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Alarcon G., Eschleman K., Bowing N.A. Relationship between personality variables and burnout: a meta-analysis. Work. Stress. 2009;23:244–263. doi: 10.1080/02678370903282600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A. Towards a multilevel approach of employee well-being. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2015;24:839–843. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2015.1071423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Freeman; 1997. Self-efficacy: the Exercise of Control. [Google Scholar]

- Brillon P., Philippe F.L., Paradis A., Geoffroy M., Orri M., Ouellet Morin I. Psychological distress of mental health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison with the general population in high- and low-incidence regions. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021;1:20. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnera A., Zarbo C., Compare A., Talia A., Tasca G.A., de Jong K., Greco A., Greco F., Pievani L., Auteri A., Lo Coco G. Self-reported reflective functioning mediates the association between attachment insecurity and well-being among psychotherapists. Psychother. Res. 2020;31:247–257. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2020.1762946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk S., Raudenbush A. Sage Publications; 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Busseri M., Sadava S. A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011;15:290–314. doi: 10.1177/1088868310391271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli A., Peng A.C., Schaubroeck J., Amir I. Social support as a source of vitality among college students: the moderating role of social self‐efficacy. Psychol. Sch. 2020;58:351–363. doi: 10.1002/pits.22450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T. Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985;98:310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R., Larsen R., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Lucas R.E., Scollon C.N. Beyond the hedonic treadmill – revising the adaptation theory of well-being. Am. Psychol. 2006;61:305–314. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Heintzelman S.J., Kushlev K., Tay L., Wirtz D., Lutes L.D., Oishi S. Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2016;58:87–104. doi: 10.1037/cap0000063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Disabato D., Goodman F., Kashdan T., Short J., Jarden A. Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychol. Assess. 2016;28:471–482. doi: 10.1037/pas0000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman R., Saunders R., Motl R., Dowda M., Pate R. Self-efficacy moderates the relation between declines in physical activity and perceived social support in high school girls. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009;34:441–451. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid M., Diener E. Global judgments of subjective well-being: situational variability and long-term stability. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2004;65:245–277. doi: 10.1023/B:SOCI.0000003801.89195.bc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C., Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enochs W., Etzbach C. Impaired student counselors: ethical and legal considerations for the family. Fam. J. 2004;12:396–400. doi: 10.1177/1066480704267240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B.L. Updated thinking on positivity ratios. Am. Psychol. 2013;68:814–822. doi: 10.1037/a0033584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A., Hill J. Cambridge University Press; 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/hierarchical Models. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason M., Iida M., Shrout P., Bolger N. Receiving support as a mixed blessing: evidence for dual effects of support on psychological outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008;94:824–838. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn V., Binnewies C., Sonnentag S., Mojza E. Learning how to recover from job stress: effects of a recovery training program on recovery, recovery-relates self-efficacy, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011;16:202–216. doi: 10.1037/a0022169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine S., Lehman D.R., Peng K., Greenholtz J. What's wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales: the reference-group problem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002;82:903–918. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll S., Halbesleben J., Neveu J., Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018;5:103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl D., Knoll N., Wiedemann A., Keller J., Scholz U., Schrader M., Burkert S. Enabling or cultivating? The role of prostate cancer patients' received partner support and self-efficacy in the maintenance of pelvic floor exercise following tumor surgery. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016;50:247–258. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9748-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist R., Jeanneau M. Burnout and psychiatric staff's feelings towards patients. Psychiatr. Res. 2006;145:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek Ł., Bujacz A., Eid M. Comparative latent state–trait analysis of satisfaction with life measures: the steen happiness index and the satisfaction with life scale. J. Happiness Stud. 2015;16:443–453. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Prieto C., Diener E., Tamir M., Scollon C., Diener M. Integrating the diverse definitions of happiness: a time-sequential framework of subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2005;6:261–300. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-7226-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M., Barley D. Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychother. Theor. Res. Pract. Train. 2001;38:357–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laverdière O., Kealy D., Ogrodniczuk J., Morin A. Psychological health profiles of Canadian psychotherapists: a wake up call on psychotherapists' mental health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2018;59:315–322. doi: 10.1037/cap0000159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laverdière O., Ogrodniczuk J., Kealy D. Clinicians' empathy and professional quality of life. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019;207:49–52. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.T., Seo B., Hladkyj S., Lovell B., Schwartzmann L. Correlates of physician burnout across regions and specialties: a meta-analysis. Hum. Resour. Health. 2013;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Kim E., Paik I., Chung J., Lee S. Relationship between environmental factors and burnout of psychotherapists: meta-analytic approach. Counsell. Psychother. Res. J. 2020;20:164–172. doi: 10.1002/capr.12245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J., Bond F., Flaxman P. Work-related self-efficacy as a moderator of the impact of a worksite stress management training intervention: intrinsic work motivation as a higher order condition of effect. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017;22:115–127. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M., Hawkley L., Eid M., Cacioppo J. Time frames and the distinction between affective and cognitive well-being. J. Res. Pers. 2012;46:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M., Hofmann W., Eid M., Lucas R.E. Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events. Meta-anal. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:592–615. doi: 10.1037/a0025948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S. In: The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Folkman S., editor. University Press; 2011. Hedonic adaptation to positive and negative experiences; pp. 200–224. [Google Scholar]

- Łuszczynska A., Cieslak R. Protective, promotive, and buffering effects of perceived social support in managerial stress: the moderating role of personality. Hist. Philos. Logic: Int. J. 2005;18:227–244. doi: 10.1080/10615800500125587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Łuszczynska A., Scholz U., Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J. Psychol. 2005;139:439–457. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łuszczynska A., Schwarzer R., Lippke S., Mazurkiewicz M. Self-efficacy as a moderator of the planning–behaviour relationship in interventions designed to promote physical activity. Psychol. Health. 2011;26:151–166. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.531571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K., Curran P., Bauer D. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006;31:437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purvanova R., Muros J. Gender differences in burnout: a meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010;77:168–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raquepaw J., Miller R. Psychotherapist burnout: a componential analysis. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1989;20:32–36. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.20.1.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg T., Pace M. Burnout among mental health professionals: special considerations for the marriage and family therapist. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2006;32:87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2006.tb01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupert P., Kent J. Gender and work setting differences in career-sustaining behaviors and burnout among professional psychologists. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2007;38:88–96. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rupert P.A., Morgan D.J. Work setting and burnout among professional psychologists. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005;36:544–550. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rzeszutek M., Schier K. Temperament traits, social support, and burnout symptoms in a sample of therapists. Psychotherapy. 2014;51:574–579. doi: 10.1037/a0036020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmack U., Diener E., Oishi S. Life-satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: the use of chronically accessible and stable sources. J. Pers. 2002;70:345–384. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R., Jerusalem M. In: Measures in Health Psychology: A User's Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs. Weinman J., Wright S., Johnston M., editors. NFER-NELSON; 1995. Generalized self-efficacy scale; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R., Knoll N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: a theoretical and empirical overview. Int. J. Psychol. 2007;42:243–252. doi: 10.1080/00207590701396641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji K., Cieslak R., Smoktunowicz E., Rogala A., Benight C., Luszczynska A. Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: a meta-analysis. Hist. Philos. Logic. 2016;29:367–386. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2015.1058369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato G., Simpson S. Personal risk factors associated with burnout among psychotherapists: a systematic review of the literature. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018;7:1431–1456. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Deaton A., Stone A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet. 2015;14:640–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetz T., Stetz M., Bliese P. The importance of self-efficacy in the moderating effects of social support on stressor–strain relationships. Work. Stress. 2006;20:49–59. doi: 10.1080/02678370600624039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steel P., Schmidt J., Shultz J. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 2008;134:138–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E. Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2007;38:227–242. doi: 10.1177/0022022106297301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth K., Mason C.M. Help yourself: the mechanisms through which a self-leadership intervention influences strain. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012;17:235–245. doi: 10.1037/a0026857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver F., Leung K. Sage; 1997. Methods and Data Analysis of Comparative Research. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chung M., Wang N., Yu X., Kenardy J. Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021;85 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner L., Ziegelmann J., Schüz B., Wurm S., Schwarzer R. Synergistic effect of social support and self-efficacy on physical exercise in older adults. J. Aging Phys. Activ. 2011;19:249–261. doi: 10.1123/japa.19.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D., Clark L., Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect. The PANAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1053/:102670883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wogan M., Norcross J.C. Dimensions of therapeutic skills and techniques: empirical identification, therapist correlates, and predictive utility. Psychother. Theor. Res. Pract. Train. 1985;22:63–74. doi: 10.1037/h0088528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G., Powell S., Farley G., Werkman S., Berkoff K. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990;55:610–617. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5503&4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.