Abstract

In hermatypic scleractinian corals, photosynthetic fixation of CO2 and the production of CaCO3 are intimately linked due to their symbiotic relationship with dinoflagellates of the Symbiodiniaceae family. This makes it difficult to study ion transport mechanisms involved in the different pathways. In contrast, most ahermatypic scleractinian corals do not share this symbiotic relationship and thus offer an advantage when studying the ion transport mechanisms involved in the calcification process. Despite this advantage, non-symbiotic scleractinian corals have been systematically neglected in calcification studies, resulting in a lack of data especially at the molecular level. Here, we combined a tissue micro-dissection technique and RNA-sequencing to identify calcification-related ion transporters, and other candidates, in the ahermatypic non-symbiotic scleractinian coral Tubastraea spp. Our results show that Tubastraea spp. possesses several calcification-related candidates previously identified in symbiotic scleractinian corals (such as SLC4-γ, AMT-1like, CARP, etc.). Furthermore, we identify and describe a role in scleractinian calcification for several ion transporter candidates (such as SLC13, -16, -23, etc.) identified for the first time in this study. Taken together, our results provide not only insights about the molecular mechanisms underlying non-symbiotic scleractinian calcification, but also valuable tools for the development of biotechnological solutions to better control the extreme invasiveness of corals belonging to this particular genus.

Subject terms: Physiology, Transcriptomics, Marine biology

Introduction

In scleractinian corals (Cnidaria, Anthozoa), also known as stony corals, calcification leads to the formation of a biomineral composed of two fractions, one made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) in the mineral form of aragonite1–3, and the other made of organic molecules4–6. Based on the ability of scleractinian corals to build reef structures, they are functionally divided into two main groups, namely, hermatypic (i.e. reef-building) and ahermatypic (i.e. non-reef-building). The majority of hermatypic corals hosts symbiotic dinoflagellates of the Symbiodinacae family7 in their tissues, commonly known as zooxanthellae8. This symbiotic association, which is lacking in most ahermatypic corals, provides the nutritional foundation for the host metabolism and boosts calcification in nutrient-poor tropical waters9.

Given the ability of hermatypic corals to build reefs, and given the economic and ecological importance associated with reef structures10, symbiotic scleractinian corals have been a major focus of calcification research over the years2,11. Whereas, ahermatypic non-symbiotic scleractinian corals have not been extensively studied and to date they remain under-represented especially in terms of molecular data12. These corals, however, should not be neglected as they represent important resources for scleractinian calcification research. This is because, in symbiotic scleractinian corals, calcification is linked to the photosynthetic fixation of CO2—both at the spatial as well as the temporal scales—which makes it difficult to disentangle these processes. Whereas, non-symbiotic scleractinian corals allow studying the transport mechanisms involved in calcification without the confounding factor of symbiosis13. In addition, studying calcification in non-symbiotic scleractinian corals further allows obtaining comparative information on the different scleractinian calcification strategies, therefore aiding in a better understanding of how calcification evolved within this order.

One of the main questions surrounding scleractinian calcification is how (i.e. via which molecular tools) corals promote a favorable environment for calcification14. As in other biological groups, coral calcification is a biologically controlled process, meaning that the precipitated mineral is not a byproduct of metabolic processes (also known as biologically induced biomineralization), but rather under strict biological and physiological control15,16. This control is exerted by a specialized tissue called the calicoblastic epithelium, that comprises the calcifying calicoblastic cells17. These cells control and promote calcification by modifying the chemical composition at the sites of calcification, which comprise intracellular vesicles and the extracellular calcifying medium (ECM)14. As recently suggested, calcification begins with the formation of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) nanoparticles, within intracellular vesicles, in the calicoblastic cells. ACC nanoparticles are then released via exocytosis into the ECM18. Here, ACC nanoparticles attach (i.e. nanoparticle attachment) and crystallize, while ions fill the interstitial spaces between them (i.e. ion-by-ion filling). Both, nanoparticle attachment and ion-by-ion filling processes require the calicoblastic cells to regulate ion transport and their concentration at the sites of calcification2,19. Furthermore, the calicoblastic cells also secrete an organic matrix which may stabilize ACC in the intracellular vesicles and play other roles, such as aiding and promoting ACC crystallization20–24.

Ion (i.e. calcium, carbonate, protons, and others) transport, to and from the sites of calcification, is of particular interest2,19. For instance, calcium and carbonate ions, the building blocks of the coral skeleton, have to be constantly supplied to the sites of calcification to sustain its growth25. Whereas, protons must be removed from the sites of calcification to increase the aragonite saturation state, prevent dissolution of calcium carbonate nanoparticles, and promote ion-by-ion filling mechanisms14.

Over the years, the ion transport model underlying scleractinian calcification has been well characterized for the calicoblastic cells through physiological and molecular studies26–28. However, such understanding is only partial and many calcification-related ion transporters still need to be identified. When searching for calcification-related candidates, different approaches are possible. One is the so called “targeted” approach and is based on the analysis of genes and/or proteins that have been chosen a priori- generally based on known biological functions in other model systems. This approach is extremely powerful for studying the genetic architecture of complex traits, such as calcification, in addition to being an effective approach for direct gene discovery29. Nevertheless, although the targeted approach has led to the identification of some of the most relevant calcification-related candidates in scleractinian calcification13,30–32, it is largely limited by the requirement of existing knowledge about the gene(s) under investigation. To overcome this limitation, other approaches, the so-called “broad” approaches, have been developed throughout the years. Broad approaches have the potential to discover novel candidates and pathways that have not been previously considered in the context of calcification, thus allowing a more holistic understanding of the process. These approaches have been performed at different levels, including the transcriptomic one, which relies on the use of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technology33–35. To date, however, the use of RNA-seq to identify calcification-related candidates has been limited to analyzing coral molecular responses to environmental parameters known to influence calcification (such as light33 and CO236), and only one study, performed in the symbiotic scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata, has analyzed genes being more highly expressed in the coral calcifying tissue37.

Therefore, given the high potential of broad approaches in discovering novel candidates, and given the scarce amount of data available for non-symbiotic scleractinian corals12, we have performed, in this study, RNA-seq on coral species belonging to the ahermatypic non-symbiotic scleractinian genus Tubastraea (Lesson, 1829)38. Tubastraea corals include invasive saltwater species39–42 that were introduced into the southwestern Atlantic on oil platforms42. Since the late 1980s, these corals have been colonizing the rocky shores of the southeastern Brazilian coast40. Their rapid spread and growth provides them a competitive advantage and, therefore, represent a serious risk for endemic biodiversity loss43. In the absence of innovation in control methods, the dispersal of Tubastraea is expected to continue. In this context, calcification studies are fundamental to a better understanding of the life histories and population ecology of this genus. Of particular interest is the rapid linear skeletal growth of Tubastraea that could increase the competitiveness of these species44. In this study, we searched for calcification-related candidates, by sequencing the whole transcriptome from total colonies and oral fractions (i.e. fractions devoid of the aboral tissues that contain the calicoblastic cells) of Tubastraea spp., obtained through a tissue micro-dissection technique. After assembling and annotating a highly complete transcriptome for Tubastraea spp., we identified and analyzed genes enriched in the total colony transcriptomes compared to the oral fraction transcriptomes. The analysis included both a comparison with calcification-related candidates previously characterized in symbiotic scleractinian corals, as well as a search for novel calcification-related ion transporter candidates.

This study provides insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying non-symbiotic scleractinian calcification and identifies valuable tools for the development of biotechnological solutions to better control the extreme invasiveness of corals belonging to this genus.

Results

Sequence read data and raw data pre-processing

RNA sequencing was performed for two sample groups, total colony and oral fraction (i.e. fraction devoid of the aboral tissues containing the calcifying calicoblastic cells), of three independent biological replicates (n = 3) of Tubastraea spp. Both groups, obtained through a previously developed micro-dissection protocol45, produced a total of 539,331,300 raw reads with an average of 44.9 ± 8.7 (mean ± SD) million read pairs per sample. Raw reads were subjected to quality trimming, which included adaptor removal, yielding a total of 369,357,576 trimmed reads.

De novo transcriptome assembly and quality assessment

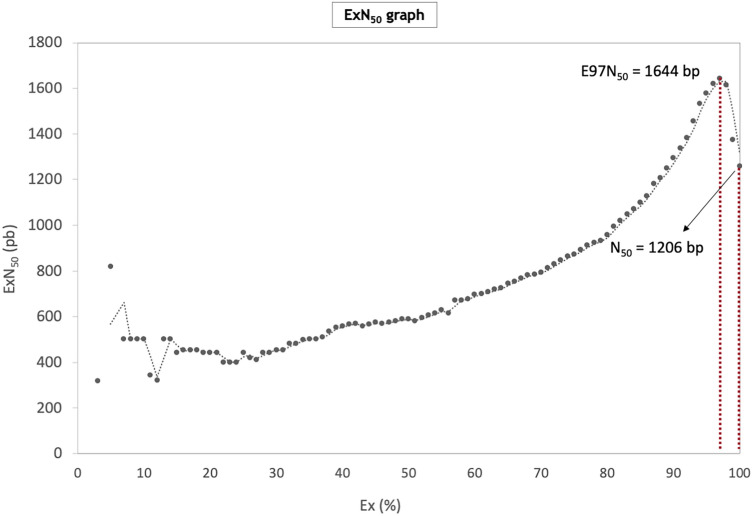

Trimmed reads were subjected to de novo whole transcriptome assembly using Trinity, after being further reduced to 73,014,522 by in silico normalization. Trinity assembler produced 691,300 transcripts, which were then clustered into 48,638 unigenes (i.e. uniquely assembled transcripts) with N50 1206 bp. Based on BUSCO, the assembled transcriptome was highly complete with 94.9% ortholog genes from Eukaryota database being present with low fragmentation (2.7%), missing (2.4%), and duplication (15.7%). In addition, ExN50 statistics showed that the maximum N50 value was on E97% with 1644 bp N50 length (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Expression-dependent N50 (ExN50), as calculated against a fraction of the total expressed data (Ex). ExN50 at the point of assembly saturation (97%) and traditional N50 are highlighted.

Functional annotation

To evaluate the completeness of the transcriptome library, functional annotation—including GO terms, EggNOG and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis—of the whole transcriptome of Tubastraea spp. was performed using Blastx results and OmicsBox. A summary of the whole transcriptome assembly and annotation results is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the transcriptome assembly, annotation, and differential abundance analysis.

| Total number of contigs | 75,006 |

| Total number of unigenes | 48,638 |

| Blast annotated | 59,505 |

| InterProScan annotated | 75,005 |

| GO annotated | 18,246 |

| EggNOG annotated | 44,319 |

| KEGG annotated | 4,203 |

| Differentially expressed genes FDR < 0.05, LogFC < ± 1 | 4,483 |

| Enriched genes in the total vs oral | 3,174 |

| Enriched genes in the oral vs total | 1,309 |

Differential expression analysis

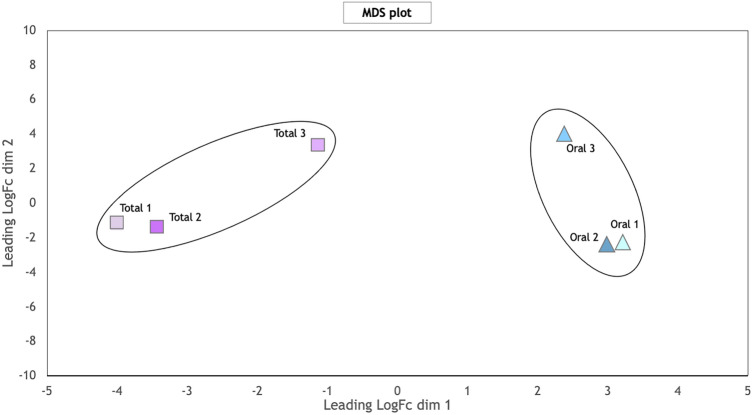

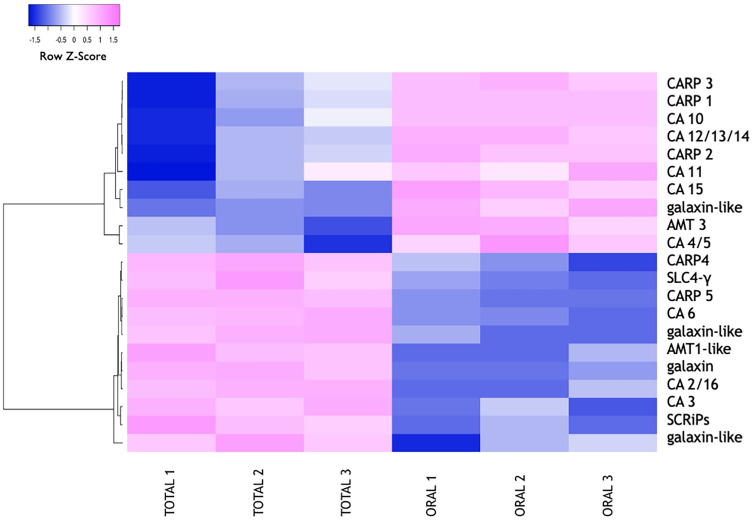

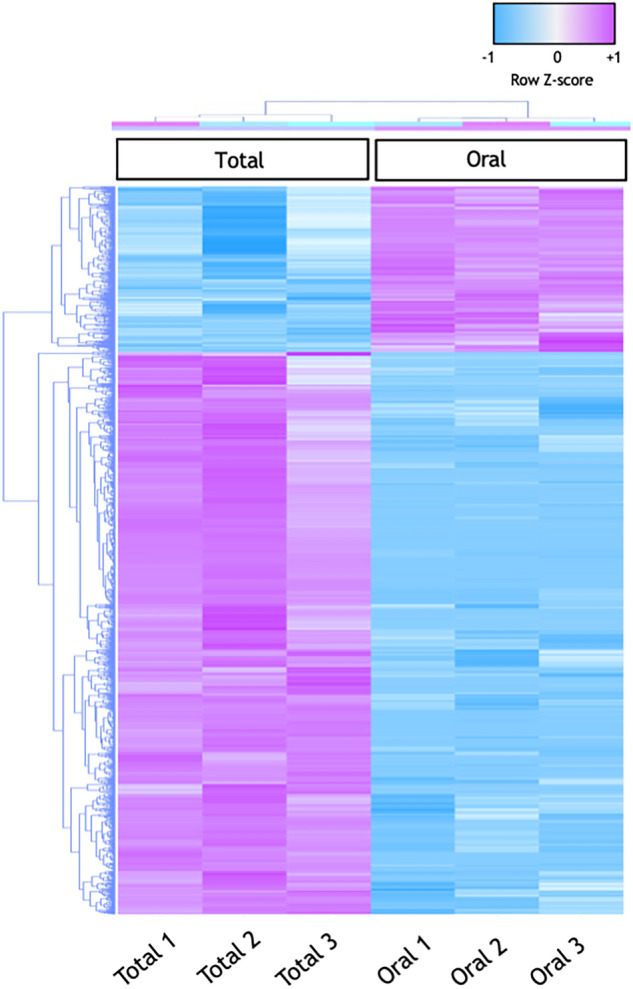

To identify differentially expressed genes between the total colony and the oral fraction, we first selected genes that had count per millions (CPM) more than 1 in at least two samples. Differential expression analysis was then performed using OmicsBox, followed by Benjamini–Hochberg multiple test correction. A total of 4,483 genes were reported to be differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05, LogFC < ± 1) between the total colony and the oral fraction (Table 1). Of these, 3,174 genes were significantly enriched in the total colony compared to the oral fraction, and 1,309 genes were significantly enriched in the oral fraction compared to the total colony. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) have been clustered using Pearson’s correlation and displayed in a heatmap (Fig. 2). In this heatmap, biological replicates (1, 2 and 3) show strong clustering within the same group (Total and Oral), which are also clearly separated. In addition, a Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) plot was performed to examine the homogeneity across biological replicates (Fig. 3). According to the MDS results, biological replicates showed strong clustering within each group and each group formed a distinct cluster.

Figure 2.

Heatmap and hierarchical cluster of 4,483 differentially expressed transcripts. The heatmap was generated using trimmed mean of M-values (TMM). Sample clustering was done using Pearson’s correlation. The Z-score scale is shown in the top-right corner ranging from − 1 (blue) to + 1 (violet).

Figure 3.

MDS plot of the data set. Samples (n = 6) are separated by the biological replicate in the first dimension and by the coral fraction in the second dimension.

Comparison of calcification-related candidates between non-symbiotic and symbiotic scleractinian corals

To assess whether calcification-related candidates, previously identified in symbiotic scleractinian corals, were also present in Tubastraea spp., we performed a search for known homologs in the Tubastraea spp. transcriptome. Based on their role and their cellular/extracellular localization, these candidates can be divided into two groups: ion membrane transporters/enzymes and skeletal organic matrix proteins. Ion membrane transporters/enzymes comprise: Ammonium Transporters (AMTs)46, voltage gated proton channels (HvCNs)47, Na+/H+ exchanger (SLC9A)47, the SoLute Carrier 4-γ (SLC4-γ)31, Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPases (PMCAs)30 and the Voltage-Gated Ca2+-Channel (VGCC)32. Whereas, skeletal organic matrix proteins comprise: Coral Acid-Rich Proteins (CARPs)35, neurexins48, galaxins49 and Small Cysteine-Rich Proteins (SCRiPs)50. Carbonic Anhydrases (CAs)34,51 fall in between these two groups as they have been also identified in the organic matrix of the coral skeleton13. Our results show that, among the 75,006 contigs (Table 1), Tubastraea spp. possesses 55 protein sequences homologous to calcification-related candidates of symbiotic scleractinian corals (Table S1). Of these, only 21 (38%) are differentially expressed between the total colony and the oral fraction: 10/21 are enriched in the oral fraction compared to the total colony (CARP-1, -2 and -3, CA-4/5, 10, 11, 12/13/14 and 15, AMT3 and one galaxin-like) and 11/21 are enriched in the total colony compared to the oral fraction (CARP-4 and -5, SLC4-γ, CA-6, -2/16 and 3, two galaxin-like proteins and one galaxin, AMT1-like and SCRiPs) (Fig. 4 and Table S2). It is important to note that Tubastraea spp. CARPs and CAs have been named according to the phylogenetic trees provided in Figures S1 and S2.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of calcification-related genes differentially expressed between the total colony and the oral fraction.

Our results also show that 34 (62%) of the 55 protein sequences are not differentially expressed between the total colony and the oral fraction, and thus are not found in the heatmap (Fig. 4). These included: HvCNs, SLC9s, PMCAs, and VGCC.

Functional annotation and identification of unigenes putatively involved in coral calcification

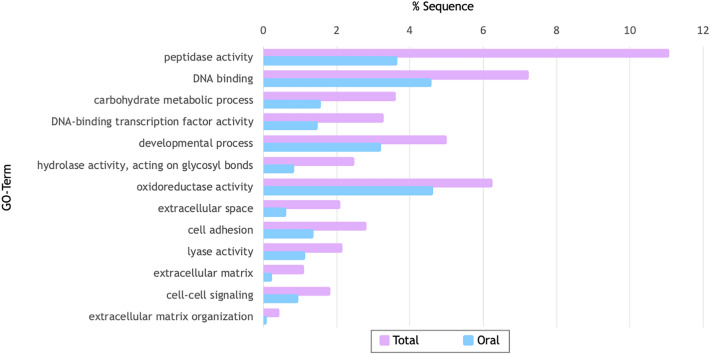

DEGs were annotated using the same databases used for the whole transcriptome annotation. First, GO-term enrichment analysis using Fisher’s exact test was performed to infer which biological processes are associated with the enriched genes in the total colony compared to the oral fraction. Our results show 13 enriched GO-terms, including biological processes associated with “carbohydrate metabolic process”, “extracellular space”, “cell adhesion”, “extracellular matrix” and “extracellular matrix organization” (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis GO-terms associated with enriched genes in the total colony compared to the oral fraction.

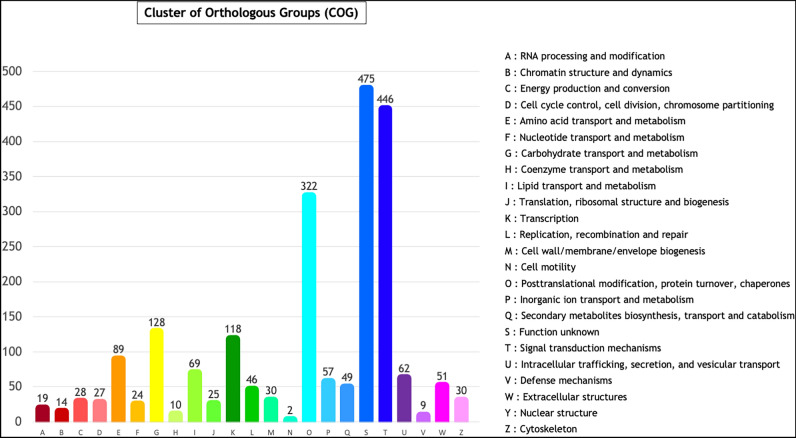

EggNOG functional annotation of the enriched genes in the total colony compared to the oral fraction was then performed. A total of 2,841 out of 3,174 enriched genes (88.6%) are functionally annotated into 23 COG functional categories, including inorganic ion transport and metabolism (P), and intracellular trafficking, secretion and vesicular transport (U) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

EggNOG classifications of enriched genes in the total colony compared to the oral fraction EggNOG categories are shown on the horizontal axis as alphabets with corresponding category names on the right.

Finally, using the KO term, provided by the EggNOG mapper, of each annotated gene, we performed KEGG annotation. KEGG annotation further divided genes into multiple families. Among these, 39 KO terms are associated with ion transporters (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of enriched transcripts, involved in ion transport, in the total colony compared to the oral fraction.

| KO term | Ion transporters unigenes | Functional annotation | FC |

|---|---|---|---|

| K14611 | TRINITY_DN1292_c0_g1_i21.p1 | Solute carrier family 23 (nucleobase transporter), member 1 | 916.1 |

| K15381 | TRINITY_DN15243_c0_g1_i12.p1 | MFS transporter, FLVCR family, disrupted in renal carcinoma protein 2 | 500.7 |

| K05655 | TRINITY_DN13741_c0_g1_i13.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily B (MDR/TAP), member 8 | 333.1 |

| K06580 | TRINITY_DN11254_c0_g1_i6.p1 | SLC42A; ammonium transporter Rh | 317.7 |

| K22190 | TRINITY_DN43565_c0_g1_i3.p1 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains subfamily A member 3/4/8/12/15/18 | 206.8 |

| K21893 | TRINITY_DN88858_c0_g1_i5.p1 | Neuroglobin | 182.3 |

| K21396 | TRINITY_DN29747_c0_g1_i6.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (WHITE), eye pigment precursor transporter | 100.7 |

| K15104 | TRINITY_DN18817_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial oxoglutarate transporter), member 11 | 95.7 |

| K21396 | TRINITY_DN10851_c0_g1_i5.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (WHITE), eye pigment precursor transporter | 85.5 |

| K08187 | TRINITY_DN104999_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters), member 10 | 62.1 |

| K17769 | TRINITY_DN45389_c0_g1_i4.p1 | Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM22 | 61.4 |

| K13868 | TRINITY_DN7767_c0_g1_i15.p1 | Solute carrier family 7 (L-type amino acid transporter), member 9/15 | 53.2 |

| K14387 | TRINITY_DN6094_c0_g1_i13.p1 | Solute carrier family 5 (high affinity choline transporter), member 7 | 52.7 |

| K14613 | TRINITY_DN38892_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 46 (folate transporter), member 1 | 49.4 |

| K09866 | TRINITY_DN9220_c0_g1_i2.p1 | Aquaporin-4 | 43.4 |

| K08204 | TRINITY_DN84629_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 22 (organic anion transporter), member 7 | 42.5 |

| K05673 | TRINITY_DN43332_c0_g1_i2.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 4 | 39.9 |

| K08187 | TRINITY_DN57711_c0_g1_i2.p1 | Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters), member 10 | 39.2 |

| K15109 | TRINITY_DN17474_c0_g1_i7.p1 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carnitine/acylcarnitine transporter), member 20/29 | 35.1 |

| K15108 | TRINITY_DN12359_c10_g1_i3.p1 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial thiamine pyrophosphate transporter), member 19 | 32.2 |

| K05643 | TRINITY_DN170738_c0_g1_i2.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A (ABC1), member 3 | 23.7 |

| K14445 | TRINITY_DN38284_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 13 (sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter), member 2/3/5 | 16.4 |

| K05673 | TRINITY_DN29216_c2_g1_i3.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 4 | 13.6 |

| K21396 | TRINITY_DN29747_c0_g1_i3.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (WHITE), eye pigment precursor transporter | 12.4 |

| K05673 | TRINITY_DN73454_c0_g1_i2.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 4 | 8.9 |

| K08204 | TRINITY_DN23500_c0_g1_i4.p1 | Solute carrier family 22 (organic anion transporter), member 7 | 8.8 |

| K14686 | TRINITY_DN90716_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 31 (copper transporter), member 1 | 8.6 |

| K21862 | TRINITY_DN29586_c0_g1_i7.p1 | Voltage-gated cation channel | 8.5 |

| K21988 | TRINITY_DN5910_c4_g1_i1.p1 | Transmembrane channel-like protein | 7.4 |

| K14611 | TRINITY_DN1292_c0_g1_i23.p1 | Solute carrier family 23 (nucleobase transporter), member 1 | 6.8 |

| K08204 | TRINITY_DN23500_c0_g1_i3.p1 | Solute carrier family 22 (organic anion transporter), member 7 | 6.5 |

| K14445 | TRINITY_DN20897_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 13 (sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter), member 2/3/5 | 6.4 |

| K15109 | TRINITY_DN22386_c0_g1_i6.p1 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carnitine/acylcarnitine transporter), member 20/29 | 6.4 |

| K14994 | TRINITY_DN9280_c0_g1_i8.p1 | Solute carrier family 38 (sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter), member 7/8 | 6.3 |

| K05039 | TRINITY_DN7450_c0_g1_i13.p1 | Solute carrier family 6, member 6 | 5.7 |

| K15015 | TRINITY_DN68697_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 32 (vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter) | 5.7 |

| K08187 | TRINITY_DN26257_c3_g1_i4.p1 | Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters), member 10 | 5.3 |

| K11536 | TRINITY_DN3340_c0_g2_i6.p1 | Pyrimidine nucleoside transport protein | 5.3 |

| K05038 | TRINITY_DN12243_c1_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 6, member 5/9 | 5.1 |

| K00799 | TRINITY_DN12289_c0_g1_i14.p1 | Glutathione S-transferase | 4.8 |

| K21862 | TRINITY_DN9832_c0_g1_i2.p1 | Voltage-gated cation channel | 4.6 |

| K08204 | TRINITY_DN19075_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 22 (organic anion transporter), member 7 | 4.3 |

| K08187 | TRINITY_DN16679_c0_g2_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters), member 10 | 4.2 |

| K14453 | TRINITY_DN16687_c0_g1_i7.p1 | Solute carrier family 26 | 4.2 |

| K14683 | TRINITY_DN5423_c0_g1_i6.p1 | Solute carrier family 34 (sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter) | 4.2 |

| K03320 | TRINITY_DN16401_c0_g1_i7.p1 | Ammonium transporter, Amt family | 4.1 |

| K05048 | TRINITY_DN609_c1_g1_i13.p1 | Solute carrier family 6, member 15/16/17/18/20 | 3.9 |

| K21396 | TRINITY_DN10851_c0_g1_i4.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (WHITE), eye pigment precursor transporter | 3.8 |

| K05048 | TRINITY_DN609_c1_g1_i14.p1 | Solute carrier family 6, member 15/16/17/18/20 | 3.6 |

| K05678 | TRINITY_DN8486_c0_g1_i4.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily D (ALD), member 4 | 3.5 |

| K05048 | TRINITY_DN2910_c0_g1_i4.p1 | Solute carrier family 6, member 15/16/17/18/20 | 3.3 |

| K00799 | TRINITY_DN1669_c0_g1_i3.p1 | Glutathione S-transferase | 3.2 |

| K15281 | TRINITY_DN9775_c0_g1_i5.p1 | Solute carrier family 35 | 3.2 |

| K14995 | TRINITY_DN19648_c0_g1_i1.p1 | Solute carrier family 38 (sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter), member 9 | 3.2 |

| K06580 | TRINITY_DN1639_c0_g1_i6.p1 | SLC42A; ammonium transporter Rh | 3.1 |

| K12385 | TRINITY_DN8972_c0_g1_i9.p1 | Niemann-Pick C1 protein | 3.1 |

| K05038 | TRINITY_DN8948_c0_g1_i15.p1 | Solute carrier family 6, member 5/9 | 2.9 |

| K15015 | TRINITY_DN14356_c0_g1_i5.p1 | Solute carrier family 32 (vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter) | 2.9 |

| K15381 | TRINITY_DN1196_c2_g2_i3.p1 | MFS transporter, FLVCR family, disrupted in renal carcinoma protein 2 | 2.9 |

| K11518 | TRINITY_DN2445_c7_g1_i4.p1 | Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM40 | 2.8 |

| K14613 | TRINITY_DN9535_c0_g1_i2.p1 | Solute carrier family 46 (folate transporter), member 1 | 2.7 |

| K12385 | TRINITY_DN2483_c0_g1_i6.p1 | Niemann-Pick C1 protein | 2.5 |

| K05643 | TRINITY_DN2705_c1_g1_i6.p1 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A (ABC1), member 3 | 2.3 |

| K05399 | TRINITY_DN12573_c1_g1_i4.p1 | Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein | 2.1 |

Discussion

The “calcification toolkit” is the collective term documented and/or hypothesized to be involved in biomineral formation at various stages of an organism’s life history52. Out of all the toolkit components, proteins have been the most intensively characterized26,53,54. As a result, proteomic studies have suggested that, although proteins from distant organisms share common properties53, each taxon-specific suite appears to have evolved independently through convergent and co-option evolution. This has led to variable contributions, from new lineage- and species-specific proteins, to the “calcification toolkit”, which show contrasting rates of conservation between and within lineages55. Several tools of the “calcification toolkit” have also been identified in scleractinian corals48,56, yet to date only few experiments have been conducted and solely for symbiotic species54. Other than being particularly attractive for calcification studies because of the lack of symbiotic dinoflagellates in their tissues, corals belonging to the Tubastraea genus have been the focus of numerous biological57–59 and ecological research studies60,61 aiming at identifying key parameters underlying their invasiveness. Nevertheless, their “calcification toolkit”, which may include specific components providing these corals with an advantage in terms of calcification strategies, has never been investigated at the molecular level. In this study, we aimed to fill this knowledge gap by searching for candidates of the “calcification toolkit” in the non-symbiotic scleractinian coral Tubastraea spp. using a tissue micro-dissection technique to remove the oral fraction (easily accessible and free of the calicoblastic cells) from the total colony of Tubastraea spp. This previously developed technique has already been used in the past and has contributed to the identification of some of the most frequently searched and studied candidates in a wide range of calcifying metazoans26,62,63, other than corals31,45,47. By coupling this technique with RNA-seq, we have then identified and analyzed differentially expressed genes with a focus on those enriched in the total colony compared to the oral fraction. Indeed, these genes are specific of the aboral tissues and include calicoblastic cell-specific genes, that could play a role in calcification. This is supported by our results showing that, although many genes are ubiquitously expressed in the total colony—and thus in both oral and aboral tissues -, others are differentially expressed, with clearly distinct expression profiles between the total colony and the oral fraction (Figs. 2 and 3). It follows that the different expression profiles reflect specific gene functions related to the oral and aboral tissues. Amongst the 3,174 aboral-specific genes (Table 1), we identified most calcification-related candidates previously described as part of the “calcification toolkit” of symbiotic scleractinian corals (Fig. 4). These include the bicarbonate transporter SLC4-γ64. SLC4-γ has been proposed to play a role both in the regulation of intracellular HCO3- homeostasis—which is critical to buffer excess of H+ generated during CaCO3 precipitation—and the supply of HCO3- to the calcifying cells in several organisms, including sea urchins63,65, mussel62, coccolithophores66 and corals31,67. We also identified an ammonium transporter belonging to the AMT1 sub-clade (Fig. 4). AMT transporters have been suggested to play a role in calcification in multiple metazoans, including mollusks68–70 and symbiotic scleractinian corals71–73. Although their role in coral calcification still needs to be investigated in detail, it has been suggested that AMT1 transporters mediate pH regulation in the ECM by transporting NH3 into the ECM which could buffer excess of protons. Organic matrix proteins, including 2 CARPs and 1 SCRiP, were also identified (Fig. 4). CARPs are proteins with dominant Low Complexity Domains (LCDs) that have been described in the secreted organic matrix of biominerals in different metazoan taxa74–77. CARPs have been identified also in previous proteomic studies on coral skeletons35, where they have been suggested to play a role in CaCO3 formation given their high affinity to positively charged ions (i.e. Ca2+)78–80. SCRiPs, instead, are a family of putatively coral-specific genes for which different roles have been suggested based on their molecular features (i.e. presence of signal peptide, high amino acidic residues content and cysteine-rich)50. Moreover, three galaxins-like proteins and three CAs were also identified (Fig. 4). Galaxin was first identified in the exoskeleton of the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis and was described as a tandem repeat structure with a di-cysteine motif fixed at nine positions49. Since this discovery, galaxin homologs have been observed in the exoskeleton of other scleractinian species81–83, as well as in mollusks84 and squid85. It has also been shown that galaxin is associated with the developmental onset of calcification after larval stage in Acropora millepora86. Whereas CAs are metallo-enzymes that catalyze the reversible hydration of CO2 into HCO3-, the source of inorganic carbon for CaCO3 precipitation. In metazoans, CAs belong to a multigenic family and are widely known to be involved in calcification in diverse metazoans such as sponge spicules87,88, mollusk shells89,90, sea urchin skeleton91, and bird eggshells92, as well as scleractinian corals34,51. In Tubastraea aurea, CAs were previously identified both in the coral tissues and the skeletal organic matrix, where they have been suggested to play a direct role in calcification13. Here, we have identified 3 CAs with higher expression in the total colony compared to the oral fraction, which suggests a potential role in calcification.

The presence of these candidates amongst the aboral-specific genes of a non-symbiotic scleractinian coral strongly suggests a calcification-related function and, in a wider context, further supports the hypothesis of a “common calcification toolbox” in scleractinian corals, as previously suggested93.

However, several components of the toolbox have not been identified amongst the aboral-specific genes of Tubastraea spp. (Fig. 4). These include: (1) voltage-gated H+ channels (HvCN), that have been suggested to participate in the pHi homeostasis of calcifying coccolithophore cells94, in the larval development and shell formation of the blue mussel62 and in the calicoblastic cells of several symbiotic scleractinian coral species47,95; (2) SLC9s, that have been suggested to play a role in H+ removal during trochophore development in mussels62 and coral calcification47, (3) Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA), which have been suggested to take part in Ca2+ supply to the sites of calcification in mussels62, as well as in the pHECM regulation of the ECM in corals30, neurexins, that connect the calicoblastic cells to the extracellular matrix in corals48 and (4) Voltage-Gated Ca2+-channels (VGCC), which have been suggested to facilitate Ca2+ transport in the calcifying epithelium of oysters96 and corals30. One possible explanation of these results is that gene gain/loss or even change of protein function has occurred during scleractinian evolutionary history, resulting in a different “calcification toolkit”. This is further supported by the hypothesis that, although calcification-related proteins from distant organisms share common properties53, they have evolved independently, through convergent evolution and co-option, in each taxon, thus resulting in contrasting rates of conservation between and within lineages55.

In addition to comparing these calcification-related candidates between non-symbiotic and symbiotic scleractinian corals, we have also searched for novel ion transporter candidates of the “calcification toolkit” in Tubastraea spp. by focusing on the rest of the aboral-specific genes. To explore their involvement in biological processes, we performed a GO enrichment analysis, and showed that, among several processes, these aboral-specific genes are enriched in “extracellular space”, “cell adhesion”, “extracellular matrix” and “extracellular matrix organization” (Fig. 5). These results highlight the importance of extracellular matrices in the aboral tissues, in which they play a pivotal role in the spatial organization of the cells, as they organize them according to their function. Some examples include both the organic extracellular matrix (ECM), which facilitates cell–cell and cell-substrate adhesion with the help of desmocytes97, as well as the skeletal organic matrix (SOM), which facilitates the controlled deposition of the CaCO3 skeleton. Also, the expression of genes in the aboral tissues linked to “carbohydrate metabolic processes” suggests an enrichment of biochemical processes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, which may ensure a constant supply of energy needed to support the energy-demanding process of calcification98,99.

Moreover, EggNOG annotation (Fig. 6) shows that some of the aboral-specific genes belong to the following categories: “inorganic ion transport and metabolism” and “intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport”, thus underling the importance of membrane and vesicular transport linked to calcification in the aboral tissues2,14,18. These results are supported by recent observations of intracellular vesicles moving towards the calcification site both in corals14,18 and sea urchins100. Calcification-related ions have been suggested to be highly concentrated in these vesicles in order to promote the formation of ACC nanoparticles, which are successively deposited into the calcification compartment where crystallization occurs14. The regulation of endocytosis and vesicular transport between membrane-bound cellular compartments is therefore strictly necessary in coral calcification, and the identification of genes related to these pathways, among the Tubastraea spp. aboral-specific genes, further underlines their importance also in non-symbiotic scleractinian species.

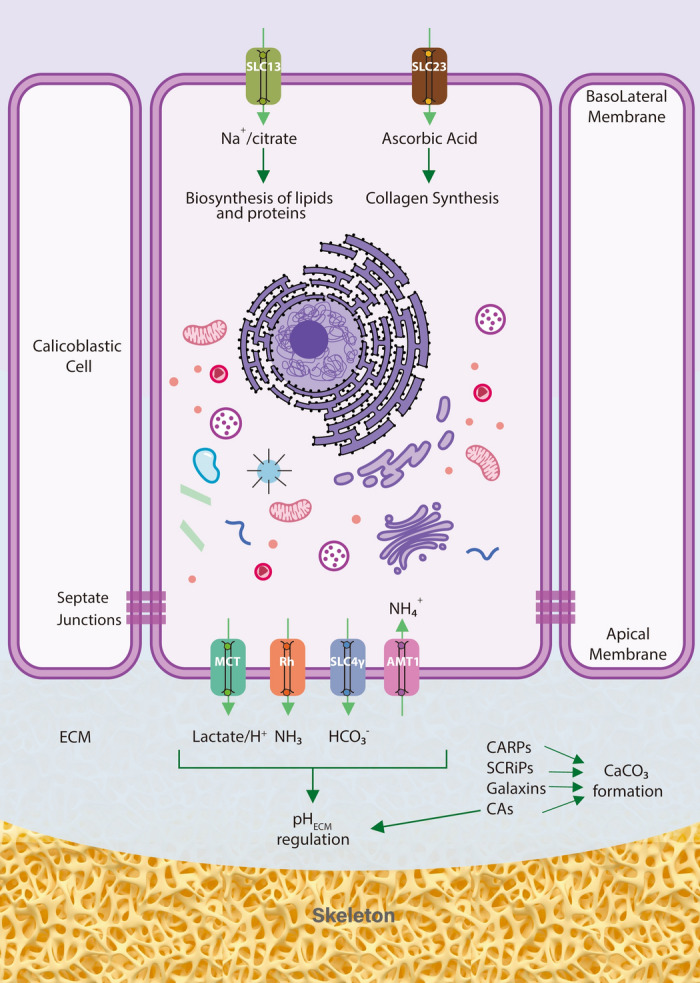

KEGG analysis further allowed us to identify a list of candidates that could play a role in calcification related ion transport (Table 2). The list includes several genes belonging to the ammonium transporter family (AMT/Rh/MEP), notably, AMT and Rh homologs. As well as for AMT transporters, also Rh transporters have been suggested to be involved in coral calcification. Rh homologs have been identified in the calicoblastic epithelium of the symbiotic scleractinian coral Acropora yongei, where they have been suggested to mediate a possible pathway for CO2—a critical substrate for CaCO3 formation—in the ECM101. The identification of these genes also among the Tubastraea spp. aboral-specific ones strongly suggests a direct role of these transporters in non-symbiotic scleractinian calcification.

We also identified a large number of transporters belonging to the SoLute Carrier (SLC) families that, in vertebrates, constitute a major fraction of transport-related genes 102 (Table 2). Some of these members (SLC7, SLC25 and SLC35) have been previously reported to be involved in coral thermal stress, while others (SLC26) have been proposed to participate in coral larval development103, as well as cellular pH and bicarbonate metabolism31.

Two plasma-membrane homologs belonging to the SLC13 family have also been identified (Table 2). These transporters function as Na+-coupled transporters for a wide range of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates104, and have been widely described in vertebrates for their role in calcification105–108. The tricarboxylic acid citrate has also been found to be strongly bound to the bone nanocrystals in fish, avian, and mammalian bone109, whereas in corals no study has shown the presence of citrate in the skeleton. In invertebrates, SLC13 members have been mainly described for their role in nutrient absorption110,111, as they provide TCA cycle metabolites, that are used for the biosynthesis of macromolecules, such as lipids and proteins2,20. These macromolecules are among the principal components of the skeletal organic matrix and SLC13 members might contribute to their transport into the coral aboral tissues.

SLC16 family members, and precisely the monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCTs), are also enriched in the total colony compared to the oral fraction (Table 2). Members of the SLC16 family comprise several subfamilies that differ in their substrate selectivity112. In corals and sea anemones, SLC16 subfamilies transporting aromatic amino acids have been mostly characterized for their role in nutrient exchange between the coral host and its symbionts36,113, while no information is available for those transporting monocarboxylic acids. In human, MCTs function as pHi regulatory transporters by mediating the efflux of monocarboxylic acid (predominantly lactate) and H+, in tissues undergoing elevated anaerobic metabolic rates114,115, and in Tubastraea spp. they might be involved in H+ extrusion at the sites of calcification perhaps functioning as pHi regulators.

Interestingly, members of the SLC23 family (FC = 916.1), which comprise ascorbic acid transporters, are the most enriched in the total colony compared to the oral fraction, in Tubastraea spp. (Table 2). This result is in agreement with another RNA-seq study performed on swimming and settled larvae of the coral Porites astreoides, also showing that an SLC23 transporter is among the most highly expressed ion transporters in larvae initiating calcification116. Ascorbic acid is an essential enzyme cofactor that participates in a variety of biochemical processes, most notably collagen synthesis117,118. Collagen is a fibrillar protein, that forms one of the main components of extracellular matrices119. Previous studies have shown that the addition of ascorbic acid stimulates collagen production in many metazoans120–122, including corals119. It is thus possible that SLC23 transporters might provide ascorbic acid to the aboral tissues, and potentially the calcifying cells, which use it to promote collagen that, together with other ECM proteins, builds a structural framework for the recruitment of calcium binding proteins, as previously suggested48,123–125.

Last but not least, our study also identified so-called “dark genes”, i.e., genes that lack annotation126, within the list of aboral-specific genes. These genes are potentially equally important, as they are expressed in the aboral tissues along with other genes with known functions in calcification. It is therefore possible that “dark genes” and calcification-related genes may be linked, as they can be involved in the same pathway e. g. enzymes and/or regulatory factors. Heterologous expression of “dark genes” in model systems, easy to manipulate and with available molecular tools for visualizing gene expression and protein localization (e. g. Nematostella vectensis) could be taken in consideration to investigate their role and contribute to functional annotation127.

Conclusion

The Tubastraea spp. transcriptome here provided is a fundamental tool which promises to provide insights not only about the genetic basis for the extreme invasiveness of this particular coral genus, but also to understand the differences between calcification strategies adopted by symbiotic and non-symbiotic scleractinian corals at the molecular level. The analysis of the aboral-specific genes of Tubastraea spp. revealed numerous candidates for a potential role in scleractinian calcification, including both previously described candidates (SLC4-γ, AMT-1like) and novel ion transporters (SLC13, −16, −23, and others) (Fig. 7). Future studies will then be required to better dissect the precise mechanisms behind these candidates and may offer further knowledge which could lead to the development of novel biotechnological strategies for prevention, management, and control of this and other invasive species.

Figure 7.

Model of a calicoblastic cell from a non-symbiotic scleractinian coral showing aboral specific ion transporter candidates identified in this study. Cellular localization of ion transporters on the apical and basolateral membrane is hypothetical and has been assigned based on previous immunolocalization studies and/or existing literature in other model systems. Dark green arrows indicate putative biological processes in which ion transporters could be involved. Abbreviation: ECM: Extracellular Calcifying Medium.

Methods

Biological material and experimental design

Experiments were conducted on non-symbiotic corals belonging to the Tubastraea genus. Corals belonging to this genus possess poorly defined taxonomic features and several unidentified morphotypes that severely challenge species identification128. Three independent Tubastraea spp. colonies, of unknown genotype, were collected in Australia in February 2018. The colonies were purchased from De JONG Marine Life, Netherland and imported with the CITES N°2018MC39519. These were grown in the long-term culture facilities at the Centre Scientifique de Monaco in aquaria supplied with seawater from the Mediterranean Sea (exchange rate 2% h−1 and flow rate of 20 L/h), under the following controlled conditions: semi-open circuit, temperature of 26 °C and no light. Corals were fed daily with frozen rotifers and twice a week with live Artemia salina nauplii.

Micro-dissection, RNA isolation and sequencing from Tubastraea spp.

Three biological replicates of Tubastraea spp. were micro-dissected by separating the oral fraction from the total colony. Then, RNA was extracted from each fraction, as previously described47. Preparation of mRNAs, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, library preparation, and sequencing using Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 were performed at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST)93.

Data analysis pipeline

Data analysis pipeline contained three major sections including: raw data pre-processing, de novo transcriptome assembly and post-processing of the transcriptome. First, raw reads of six individual libraries were subjected to quality trimming, using the software Trimmomatic (version 0.36)129. This step consisted in trimming low quality bases, removing N nucleotides, and discarding reads below 36 bases long. Then, contaminant sequences were removed, using the software BBDuk130, by blasting raw reads against a previously created contaminant_DB of the most common contaminant species—including Symbiodiniaceae. Clean and trimmed reads from all samples were then pooled together and further assembled using Trinity software (version 2.8.0) with default parameters131. The in-silico normalization was performed within Trinity prior to de novo assembly. To obtain sets of non-redundant transcripts, we applied the following filtering steps: (1) transcripts with more than 95% of identity were clustered together using CD-HIT software132 and (2) all likely coding regions were filtered by selecting the single best open reading frame (ORF) per transcript, using TransDecoder (version 3.0.0)133. Also, in the latter step, transcripts with ORFs < 100 base pairs (bp) in length were removed before performing further analyses. The final transcriptome (referred to as transcriptome_all) was subjected to quality assessment via generation of ExN50 statistics, using “contig_ExN50_statistic.pl”, and examination of orthologs completeness, using BUSCO (version 3) against eukaryota_odb10 database134. Transcriptome_all was then aligned against NCBI’s non-redundant metazoan databases using Blastx135, with a cutoff E-value of < 10–15, and the alignment results were used to annotate all the unigenes (= uniquely assembled transcripts). For their further annotation and classification, OmicsBox software (version 2.0.36)136 was used to assign Gene Ontology (GO) terms137, Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (EggNOG)138 and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis139. Additionally, differential abundance analysis to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed using OmicsBox136. To convert the RNA-Seq data into quantitative measure of gene expression, we calculated the number of RNA-Seq reads mapping to transcriptome_all. Transcripts that had at least a log fold change (LogFC) of ± 1 with a false discovery rate (FDR or adjusted p-value) less than 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dominique Desgré for coral maintenance and Alexander Venn for kindly revisioning the text of the manuscript. This study was conducted as part of the Centre Scientifique de Monaco research program, supported by the Government of the Principality of Monaco.

Author contributions

S.T. and D.Z.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, and Writing–review and editing; L.C.: Formal analysis, Investigation, and Writing–original draft; M.A., G.C. and M.P.: Validation and Writing–review and editing. All authors gave final approval for publication and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the manuscript and/or the Additional Files. Additional data related to this manuscript may be requested from the authors. Genomic and transcriptomic data were obtained from the public available database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information or from the private database of the Centre Scientifique de Monaco.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sylvie Tambutté, Email: stambutte@centrescientifique.mc.

Didier Zoccola, Email: zoccola@centrescientifique.mc.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-17022-4.

References

- 1.Allemand D, et al. Coral calcification, cells to reefs. Coral Reefs Ecosyst. Transit. 2011;1:119–150. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0114-4_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tambutté S, et al. Coral biomineralization: from the gene to the environment. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2011;408:58–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen AL. Geochemical perspectives on coral mineralization. Rev. Mineral. Geochemistry. 2003;54:151–187. doi: 10.2113/0540151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg WM. Acid polysaccharides in the skeletal matrix and calicoblastic epithelium of the stony coral Mycetophyllia reesi. Tiss. Cell. 2001;33:376–387. doi: 10.1054/tice.2001.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farre B, Cuif JP, Dauphin Y. Occurrence and diversity of lipids in modern coral skeletons. Zoology. 2010;113:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantz B, Weiner S. Acidic macromolecules associated with the mineral phase of scleractinian coral skeletons. J. Exp. Zool. 1988;248:253–258. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402480302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaJeunesse TC, et al. Systematic revision of symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:2570–2580.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furla P, et al. The symbiotic anthozoan: A physiological chimera between alga and animal. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2005;45:595–604. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muscatine L. The role of symbiotic aklgae in carbon and energy flux in reef corals. Coral Reefs. 1990;1:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleypas JA, Buddemeier RW, Gattuso JP. The future of Coral reefs in an age of global change. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2001;90:426–437. doi: 10.1007/s005310000125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falini G, Fermani S, Goffredo S. Coral biomineralization: A focus on intra-skeletal organic matrix and calcification. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;46:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soares-Souza, G. B. et al. The genomes of invasive coral Tubastraea spp. (Dendrophylliidae) as tool for the development of biotechnological solutions. bioRxiv (2020) 10.1101/2020.04.24.060574.

- 13.Tambutté S, et al. Characterization and role of carbonic anhydrase in the calcification process of the azooxanthellate coral Tubastrea aurea. Mar. Biol. 2007;151:71–83. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0452-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun CY, et al. From particle attachment to space-filling coral skeletons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:30159–30170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012025117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowenstam HA. Minerals formed by weathering. Science. 1981;211:1126–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.7008198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann S. Molecular recognition in biomineralization. Nature. 1988;332:119–124. doi: 10.1038/332119a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattuso JP, Allemand D, Frankignoulle M. Photosynthesis and calcification at cellular, organismal and community levels in coral reefs: A review on interactions and control by carbonate chemistry. Am. Zool. 1999;39:160–183. doi: 10.1093/icb/39.1.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganot P, et al. Ubiquitous macropinocytosis in anthozoans. Elife. 2020;9:1–25. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allemand D, et al. Biomineralisation in reef-building corals: From molecular mechanisms to environmental control. Compt. Rend. – Palevol. 2004;3:453–467. doi: 10.1016/j.crpv.2004.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puverel S, et al. Antibodies against the organic matrix in scleractinians: A new tool to study coral biomineralization. Coral Reefs. 2005;24:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s00338-004-0456-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mass T, Drake JL, Peters EC, Jiang W, Falkowski PG. Immunolocalization of skeletal matrix proteins in tissue and mineral of the coral Stylophora pistillata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:12728–12733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408621111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isa Y. An electron microscope study on the mineralization of the skeleton of the staghorn coral Acropora hebes. Mar. Biol. 1986;93:91–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00428658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clode PL, Marshall AT. Low temperature FESEM of the calcifying interface of a scleractinian coral. Tissue Cell. 2002;34:187–198. doi: 10.1016/S0040-8166(02)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clode PL, Marshall AT. Calcium associated with a fibrillar organic matrix in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Protoplasma. 2003;220:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s00709-002-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohn S, Merico A. Modelling coral polyp calcification in relation to ocean acidification. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:4441–4454. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-4441-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark MS. Molecular mechanisms of biomineralization in marine invertebrates. J. Exp. Biol. 2020;223:1. doi: 10.1242/jeb.206961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutner-Hoch E, Ben-Asher HW, Yam R, Shemesh A, Levy O. Identifying genes and regulatory pathways associated with the scleractinian coral calcification process. PeerJ. 2017;2017:3590. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardet C, Tambutté E, Techer N, Tambutté S, Venn AA. Ion transporter gene expression is linked to the thermal sensitivity of calcification in the reef coral Stylophora pistillata. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu M, Zhao S. Candidate gene identification approach: Progress and challenges. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2007;3:420–427. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoccola D, et al. Molecular cloning and localization of a PMCA P-type calcium ATPase from the coral Stylophora pistillata. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2004;1663:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zoccola D, et al. Bicarbonate transporters in corals point towards a key step in the evolution of cnidarian calcification. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1. doi: 10.1038/srep09983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoccola D, et al. Cloning of a calcium channel α1 subunit from the reef-building coral Stylophora pistillata. Gene. 1999;227:157–167. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moya A, et al. Whole Transcriptome Analysis of the Coral Acropora millepora Reveals Complex Responses to CO 2-driven Acidification during the Initiation of Calcification. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:2440–2454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertucci A, et al. Carbonic anhydrases in anthozoan corals—A review. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013;21:1437–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mass T, et al. Cloning and characterization of four novel coral acid-rich proteins that precipitate carbonates in vitro. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1126–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertucci A, Forêt S, Ball EE, Miller DJ. Transcriptomic differences between day and night in Acropora millepora provide new insights into metabolite exchange and light-enhanced calcification in corals. Mol. Ecol. 2015;24:4489–4504. doi: 10.1111/mec.13328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy S, Elek A, Tanay A, Grau-bove X. A stony coral cell atlas illuminates the molecular and cellular basis of coral symbiosis, calcification, and immunity. Cell. 2021;1:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miranda RJ, Cruz ICS, Barros F. Effects of the alien coral Tubastraea tagusensis on native coral assemblages in a southwestern Atlantic coral reef. Mar. Biol. 2016;163:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00227-016-2819-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cairns SD. Revision of the shallow-water azooxanthellate Scleractinia of the western Atlantic. Stud. Nat. Hist. Caribb. Reg. 2000;75:1–240. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castro CB, Pires DO. Brazilian coral reefs: What we already know and what is still missing. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001;69:357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fenner D. Biogeography of three Caribbean coral (Scleractinia) and a rapid range expansion of Tubastraea coccinea into the Gulf of Mexico. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001;69:1175–1189. [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Paula AF, Creed JC. Two species of the coral Tubastraea (Cnidaria, Scleractinia) in Brazil: a case of accidental introduction. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2004;74:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermeij MJA. Early life-history dynamics of Caribbean coral species on artificial substratum: The importance of competition, growth and variation in life-history strategy. Coral Reefs. 2006;25:59–71. doi: 10.1007/s00338-005-0056-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wellington GM, Trench RK. Persistence and coexistence of a non symbiotic coral in open reef environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1985;82:2432–2436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganot P, et al. Structural molecular components of septate junctions in cnidarians point to the origin of Epithelial Junctions in Eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:44–62. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capasso L., Zoccola D., Ganot P., M. A. and S. T. SpiAMT1d: molecular characterization, localization, and potential role in coral calcification of an ammonium transporter in Stylophora pistillata. Coral Reefs (2022). 10.1007/s00338-022-02256-5

- 47.Capasso L, Ganot P, Planas-Bielsa V, Tambutté S, Zoccola D. Intracellular pH regulation: Characterization and functional investigation of H+ transporters in Stylophora Pistillata. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;1:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12860-021-00353-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, et al. The evolution of calcification in reef-building corals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:3543–3555. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fukuda I, et al. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding a soluble protein in the coral exoskeleton. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;304:11–17. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sunagawa S, DeSalvo MK, Voolstra CR, Reyes-Bermudez A, Medina M. Identification and gene expression analysis of a taxonomically restricted cysteine-rich protein family in reef-building corals. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moya A, et al. Carbonic anhydrase in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata: Characterization, localization, and role in biomineralization. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:25475–25484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Livingston BT, et al. A genome-wide analysis of biomineralization-related proteins in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Dev. Biol. 2006;300:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans JS. The biomineralization proteome: Protein complexity for a complex bioceramic assembly process. Proteomics. 2019;19:1–12. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201900036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaquin T, Malik A, Drake JL, Putnam HM, Mass T. Evolution of Protein-Mediated Biomineralization in Scleractinian Corals. Front. Genet. 2021;12:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.618517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drake JL, Mass T, Falkowski PG. The evolution and future of carbonate precipitation in marine invertebrates: Witnessing extinction or documenting resilience in the Anthropocene? Elementa. 2014;2:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhattacharya D, et al. Comparative genomics explains the evolutionary success of reef-forming corals. Elife. 2016;5:1–26. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Capel KCC, Migotto AE, Kitahara MV. Another tool towards invasion? Polyp “bail-out” in Tubastraea coccinea. Coral Reefs. 2014;33:1. doi: 10.1007/s00338-014-1200-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Paula AF, De Oliveira Pires D, Creed JC. Reproductive strategies of two invasive sun corals (Tubastraea spp.) in the southwestern Atlantic. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK. 2014;94:481–492. doi: 10.1017/S0025315413001446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luz BLP, et al. A polyp from nothing: The extreme regeneration capacity of the Atlantic invasive sun corals Tubastraea coccinea and T. tagusensis (Anthozoa, Scleractinia) J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2018;503:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lages BG, Fleury BG, Pinto AC, Creed JC. Chemical defenses against generalist fish predators and fouling organisms in two invasive ahermatypic corals in the genus Tubastraea. Mar. Ecol. 2010;31:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miranda RJ, Tagliafico A, Kelaher BP, Mariano-Neto E. Impact of invasive corals Tubastraea spp. on native coral recruitment. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2018;605:125–133. doi: 10.3354/meps12731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramesh, K., Melzner, F., Yarra, T., Clark, M. S. & John, U. Expression of calcification ‐ related ion transporters during blue mussel larval development. 7157–7172 (2019). 10.1002/ece3.5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Hu MY, et al. A SLC4 family bicarbonate transporter is critical for intracellular pH regulation and biomineralization in sea urchin embryos. Elife. 2018;7:1–17. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Romero MF, Chen A-P, Parker MD, Boron WF. The SLC4 family of bicarbonate (HCO3-) transporters. Mol Asp. Med. 2013;34:159–182. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu MY, Petersen I, Chang WW, Blurton C, Stumpp M. Cellular bicarbonate accumulation and vesicular proton transport promote calcification in the sea urchin larva: Mechanism of skeleton calcification. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020;287:1. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Von Dassow P, et al. Transcriptome analysis of functional differentiation between haploid and diploid cells of Emiliania huxleyi, a globally significant photosynthetic calcifying cell. Genome Biol. 2009;10:1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barott KL, Perez SO, Linsmayer LB, Tresguerres M. Differential localization of ion transporters suggests distinct cellular mechanisms for calcification and photosynthesis between two coral species. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2015;309:R235–R246. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00052.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kauffman S. Homeostasis and differentiation in random genetic control networks. Nature. 1969;224:177–178. doi: 10.1038/224177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shick JM, Widdows J, Gnaiger E. Calorimetric studies of behavior, metabolism and energetics of sessile intertidal animals. Integr. Comp. Biol. 1988;28:161–181. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ip YK, et al. Light induces an increase in the pH of and a decrease in the ammonia concentration in the extrapallial fluid of the giant clam Tridacna squamosa. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2006;79:656–664. doi: 10.1086/501061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crossland CJ, Barnes DJ. The role of metabolic nitrogen in coral calcification. Mar. Biol. 1974;28:325–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00388501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Biscéré T, et al. Enhancement of coral calcification via the interplay of nickel and urease. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018;200:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roberty S, Béraud E, Grover R, Ferrier-Pagès C. Coral productivity is co-limited by bicarbonate and ammonium availability. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marie B, et al. Different secretory repertoires control the biomineralization processes of prism and nacre deposition of the pearl oyster shell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:20986–20991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210552109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kocot KM, Aguilera F, McDougall C, Jackson DJ, Degnan BM. Sea shell diversity and rapidly evolving secretomes: Insights into the evolution of biomineralization. Front. Zool. 2016;13:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12983-016-0155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Le Roy N, Jackson DJ, Marie B, Ramos-Silva P, Marin F. The evolution of metazoan a α-carbonic anhydrases and their roles in calcium carbonate biomineralization. Front. Zool. 2014;11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson DJ, et al. Parallel Evolution of Nacre Building Gene Sets in Molluscs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:591–608. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Puverel S, et al. Soluble organic matrix of two Scleractinian corals: Partial and comparative analysis. Comp Biochem. Physiol. - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;141:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marin F, Roy NL, Marie B. The formation and mineralization of mollusk shell. Front. Biosci. 2012;1:1099–1125. doi: 10.2741/s321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Addadi L, Weiner S. Interactions between acidic proteins and crystals: Stereochemical requirements in biomineralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985;82:4110–4114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takeuchi T, Yamada L, Shinzato C, Sawada H, Satoh N. Stepwise evolution of coral biomineralization revealed with genome-wide proteomics and transcriptomics. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ramos-Silva P, et al. The skeletal proteome of the coral Acropora millepora: The evolution of calcification by co-option and domain shuffling. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2099–2112. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karako-Lampert S, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Allam B, et al. Transcriptional changes in Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) in response to Brown Ring Disease. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;41:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heath-heckman EAC, et al. Shaping the microenvironment: Evidence for the influence of a host galaxin on symbiont acquisition and maintenance in the squid-vibrio symbiosis. 2015;16:3669–3682. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reyes-Bermudez A, Lin Z, Hayward DC, Miller DJ, Ball EE. Differential expression of three galaxin-related genes during settlement and metamorphosis in the scleractinian coral Acropora millepora. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009;9:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Voigt O, Adamski M, Sluzek K, Adamska M. Calcareous sponge genomes reveal complex evolution of α-carbonic anhydrases and two key biomineralization enzymes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014;14:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0230-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jackson DJ, Macis L, Reitner J, Degnan BM, Wörheide G. Sponge paleogenomics reveals an ancient role for carbonic anhydrase in skeletogenesis. Science. 2007;316:1893–1895. doi: 10.1126/science.1141560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miyamoto H, et al. A carbonic anhydrase from the nacreous layer in oyster pearls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9657–9660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marie B, Le Roy N, Zanella-Cléon I, Becchi M, Marin F. Molecular evolution of mollusc shell proteins: Insights from proteomic analysis of the edible mussel mytilus. J. Mol. Evol. 2011;72:531–546. doi: 10.1007/s00239-011-9451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mann K, Wilt FH, Poustka AJ. Proteomic analysis of sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) spicule matrix. Proteome Sci. 2010;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mann K, Maček B. Proteomic analysis of the acid-soluble organic matrix of the chicken calcified eggshell layer. Proteomics. 2006;6:3801–3810. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang, X., Zoccola, D., Liew, Y. J., Tambutte, E. & Cui, G. The evolution of calcification in reef-building corals. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Taylor AR, Chrachri A, Wheeler G, Goddard H, Brownlee C. A voltage-gated H+ channel underlying pH homeostasis in calcifying Coccolithophores. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rangel-Yescas G, et al. Discovery and characterization of Hv 1-type proton channels in reef-building corals. Elife. 2021;10:1–24. doi: 10.7554/eLife.69248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kirsikka Sillanpää J, Sundh H, Sundell KS. Calcium transfer across the outer mantle epithelium in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018;285:1. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Muscatine L, Tambutte E, Allemand D. Morphology of coral desmocytes, cells that anchor the calicoblastic epithelium to the skeleton. Coral Reefs. 1997;16:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s003380050075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Galli G, Solidoro C. ATP supply may contribute to light-enhanced calcification in corals more than abiotic mechanisms. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Al-Horani FA, Al-Moghrabi SM, De Beer D. The mechanism of calcification and its relation to photosynthesis and respiration in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar. Biol. 2003;142:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00227-002-0981-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Winter, M. R., Morgulis, M., Gildor, T., Cohen, A. R. & de-Leon, S. B. T. Calcium-vesicles perform active diffusion in the sea urchin embryo during larval biomineralization. PLoS Comput. Biol.17, 1–28 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Thies, A., Quijada-Rodriguez, A. R., Zhouyao, H., Weihrauch, D. & Tresguerres, M. A novel nitrogen concentrating mechanism in the coral-algae symbiosome. bioRxiv 1–22 (2021).

- 102.Hediger, Matthias A., et al. The ABCs of membrane transporters in health and disease (SLC series): introduction. Mol. Aspects Med.34, 95–107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Hayward, D. C. et al. Differential gene expression at coral settlement and metamorphosis - A subtractive hybridization study. PLoS One6, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Markovich, Daniel, and H. M. The SLC13 gene family of sodium sulphate/carboxylate cotransporters. Pflügers Arch.447, 594–602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.Dirckx N, Moorer MC, Clemens TL, Riddle RC. The role of osteoblasts in energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15:651–665. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Granchi D, Baldini N, Ulivieri FM, Caudarella R. Role of citrate in pathophysiology and medical management of bone diseases. Nutrients. 2019;11:1–30. doi: 10.3390/nu11112576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hardies K, et al. Recessive mutations in SLC13A5 result in a loss of citrate transport and cause neonatal epilepsy, developmental delay and teeth hypoplasia. Brain. 2015;138:3238–3250. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Irizarry AR, et al. Defective enamel and bone development in sodium-dependent citrate transporter (NaCT) Slc13a5 deficient mice. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hu YY, Rawal A, Schmidt-Rohr K. Strongly bound citrate stabilizes the apatite nanocrystals in bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:22425–22429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009219107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Miyamoto, N., Yoshida, M., Koga, H. & Fujiwara, Y. Genetic mechanisms of bone digestion and nutrient absorption in the bone-eating worm Osedax japonicus inferred from transcriptome and gene expression analyses. BMC Evol. Biol. 1–13 (2017). 10.1186/s12862-016-0844-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Frankel S, Rogina B. Indy mutants: live long and prosper. Front. Genet. 2012;3:13. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Merezhinskaya N, Fishbein WN. Monocarboxylate transporters: Past, present, and future. Histol. Histopathol. 2009;24:243–264. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lehnert, E. M. et al. Extensive differences in gene expression between symbiotic and aposymbiotic cnidarians. G3 Genes Genomes Genet.4, 277–295 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Counillon, L., Bouret, Y., Marchiq, I. & Pouysségur, J. Na+/H+ antiporter (NHE1) and lactate/H+ symporters (MCTs) in pH homeostasis and cancer metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res.1863, 2465–2480 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Rosenthal, J. J., L. Roberson, and N. V. A possible role for vitamin C in coral calcification. Am. Geophys. Union AH11A-02 (2016).

- 117.Linster CL, Van Schaftingen E. Vitamin C: Biosynthesis, recycling and degradation in mammals. FEBS J. 2007;274:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bürzle M, et al. The sodium-dependent ascorbic acid transporter family SLC23. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013;34:436–454. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Helman Y, et al. Extracellular matrix production and calcium carbonate precipitation by coral cells in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:54–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710604105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Murad S, et al. Regulation of collagen synthesis by ascorbic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2879–2882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Franceschi, Renny T., Bhanumathi S. Iyer, and Y. C. Effects of ascorbic acid on collagen matrix formation and osteoblast differentiation in murine MC3T3‐E1 cells. J. Bone Miner. Res.9, 843–854 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 122.Tsuneto, Motokazu, et al. Ascorbic acid promotes osteoclastogenesis from embryonic stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.335, 1239–1246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 123.Goldberg WM. Evidence of a sclerotized collagen from the skeleton of a gorgonian coral. Comp. Biochem Physiol B. 1974 doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(74)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mummadisetti MP, Drake JL, Falkowski PG. The spatial network of skeletal proteins in a stony coral. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2021;18:1. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2020.0859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Drake JL, Mass T, Haramaty L, Zelzion E, Bhattacharya D. Proteomic analysis of skeletal organic matrix from the stony coral Stylophora pistillata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7958–7959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301419110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cleves PA, Shumaker A, Lee JM, Putnam HM, Bhattacharya D. Unknown to known: Advancing knowledge of coral gene function. Trends Genet. 2020;36:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Layden MJ, Rentzsch F, Röttinger E. The rise of the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis as a model system to investigate development and regeneration. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2016;5:408–428. doi: 10.1002/wdev.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Arrigoni, R., et al. A phylogeny reconstruction of the Dendrophylliidae (Cnidaria, Scleractinia) based on molecular and micromorphological criteria, and its ecological implications. Zool. Scr.43, 661–688 (2014).

- 129.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.B., B. sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/.

- 131.Grabherr, M. G. ., Brian J. Haas, Moran Yassour Joshua Z. Levin, Dawn A. Thompson, Ido Amit, Xian Adiconis, Lin Fan, Raktima Raychowdhury, Qiandong Zeng, Zehua Chen, Evan Mauceli, Nir Hacohen, Andreas Gnirke, Nicholas Rhind, Federica di Palma, Bruce W., N. & Friedman, and A. R. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol.29, 644–652 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 132.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Transdecoder. https://transdecoder.github.io/ (2016).

- 134.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Götz S., Garcia-Gomez JM., Terol J., Williams TD., Nagaraj SH., Nueda MJ., Robles M., Talon M., D. J. and C. A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res.36, 3420–3435 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 136.Conesa, A. & Götz, S. Blast2GO: A comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics2008, (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 137.M. Ashburner, C. A. Ball, J. A. Blake, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Con- sortium. Nat. Genet.25, 25–29 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 138.Jaime Huerta-Cepas, Damian Szklarczyk, Davide Heller, Ana Hernández-Plaza, Sofia K Forslund, Helen Cook, Daniel R Mende, Ivica Letunic, Thomas Rattei, Lars J Jensen, Christian von Mering, P. B. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res.47, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 139.Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the manuscript and/or the Additional Files. Additional data related to this manuscript may be requested from the authors. Genomic and transcriptomic data were obtained from the public available database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information or from the private database of the Centre Scientifique de Monaco.