Abstract

As a cell-based cancer vaccine, dendritic cells (DCs), derived from peripheral blood monocytes or bone marrow (BM) treated with GM-CSF (GMDCs), were initially thought to induce antitumor immunity by presenting tumor antigens directly to host T cells. Subsequent work revealed that GMDCs do not directly prime tumor specific T cells, but must transfer their antigens to host DCs. This reduces their advantage over strictly antigen-based strategies proposed as cancer vaccines. Type 1 conventional DCs (cDC1s) have been reported to be superior to GMDCs as a cancer vaccine, but whether they act by transferring antigens to host DCs is unknown. To test this, we compared anti-tumor responses induced by GMDCs and cDC1 in Irf8 +32−/− mice, which lack endogenous cDC1 and cannot reject immunogenic fibrosarcomas. Both GMDCs and cDC1 could cross-present cell-associated antigens to CD8+ T cells in vitro. However, injection of GMDCs into tumors in Irf8 +32−/− mice did not induce anti-tumor immunity, consistent with their reported dependence on host cDC1. In contrast, injection of cDC1s into tumors in Irf8 +32−/− mice resulted in their migration to tumor-draining lymph nodes, activation of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, and rejection of the tumors. Tumor rejection did not require the in vitro loading of cDC1 with antigens, indicating that acquisition of antigens in vivo is sufficient to induce anti-tumor responses. Finally, cDC1 vaccination showed abscopal effects, with rejection of untreated tumors growing concurrently on the opposite flank. These results suggest that cDC1 may be a useful future avenue to explore for anti-tumor therapy.

Keywords: dendritic cells, tumor immunology, cell-based vaccine, abscopal tumor rejection, antigen presentation

Introduction

Dendritic cell (DC) vaccines for cancer therapy have been developed using cells generated from culturing peripheral blood monocytes or bone marrow (BM) with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (1,2), referred to as either Mo-DCs or BM-DCs, or collectively as GMDCs (3,4). GMDCs derived from peripheral blood monocytes are able to strongly stimulate T cells in mixed lymphocyte reactions (1). Similar potency for T-cell activation was found in BM-derived GMDCs (5) and in cells derived from human CD34+ BM stem cells cultured with GM-CSF and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (6). Later, addition of interleukin 4 (IL4) to GM-CSF cultures was reported to enhance and maintain antigen presentation of human DCs (7).

Cancer vaccines based on monocyte-derived GMDCs were considered to function as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by directly presenting tumor-derived antigens to tumor-specific T cells in vivo (8). Initial clinical studies indicated that the monocyte-derived GMDC vaccine formulation Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) could activate T cells specific for prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) (2), suggesting possible value in treating prostatic cancer (9). However, only modest survival benefit was reported for Sipuleucel-T in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 512 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (10). A similar DC vaccine formulation, in which monocyte-derived GMDCs were pulsed with autologous tumor lysate for use in patients with relapsed osteosarcoma, showed anti-tumor responses in only 2 of 12 vaccinated patients and resulted in little evidence of clinical benefit (11). Monocyte-derived GMDC vaccines pulsed with peptides identified as neo-antigen candidates are able to induce specific CD8+ T-cell responses in melanoma patients (12). A subsequent clinical trial showed a slightly increased 5-year survival in patients with metastatic melanoma in response to monocyte-derived GMDC vaccination (13). A smaller trial suggests that progression-free survival correlates with magnitude of the immunologic response (14). A twelve-year follow-up study of monocyte-derived GMDC vaccines in melanoma patients showed a 19% survival similar to treatment with ipilimumab (15). A clinical trial of monocyte-derived GMDCs in bone and soft tissue sarcoma showed increases in serum interferon gamma (IFNγ) and interleukin 12 (IL12), but resulted in an improvement of the clinical outcome in only a small number of patients (16). In summary, to date, there has been only slight clinical benefits realized by use of monocyte-derived GMDC cancer vaccines (17).

One feature of GMDC vaccines that may reduce their effectiveness is their reliance on host DCs for T-cell activation (18–20). Initially, GMDCs were thought to directly stimulate host T cells through in vivo presentation of tumor antigens. However, CD4+ T-cell activation by GMDC vaccination was discovered to require expression of MHC class II molecules (MHC-II) by host conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) (18). In mice globally lacking MHC-II expression, CD4+ T-cell responses induced by GMDCs were restored by selective re-expression of MHC-II on DCs, but not on B cells. Likewise, in vivo activation of OT-I T cells was induced by GMDCs, produced from C57BL/6 (B6) cells pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide, when used as a vaccine in wild-type mice, but not in mice whose DCs expressed H-2Kbm1, which cannot activate OT-I (19). Another study also supports the interpretation that endogenous cDC1 are required for vaccination with antigen-loaded monocytes (20). OT-I T-cell activation induced by OVA-peptide bearing monocytes was seen in WT mice, but not in Batf3−/− mice that lack cDC1 development. All of these results indicate that GMDCs do not present antigens directly to host T cells, but act as a source of antigen that must be transferred and processed by host cDCs that are responsible for the direct antigen presentation to both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (21).

DCs include lineages besides those derived from GM-CSF treatment of monocytes or BM. cDCs found in vivo rely on Flt3-ligand for their development and include at least two major branches, called cDC1 and cDC2, which appear to perform different functions in vivo (22–24). In particular, cDC1 are capable of cross-presentation (25) and associate with induction of anti-tumor CD8+ T-cell responses (21,26). cDC1 are more efficient in acquiring antigens from tumors compared with other DC subsets (27), and vaccination using splenic cDC1 loaded with tumor antigens induce robust tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (28). cDC1 vaccines are superior to GMDC vaccines in limiting tumor growth and enhanced response to immune checkpoint blockade (29). However, one reported function of DCs is to carry antigens from sites of tumors to the draining lymph nodes (LNs), where they can distribute these antigens to resident DCs (30). If cDC1 vaccines function only to carry antigens to LNs, then they may provide no greater clinical benefit than that of GMDCs. For this reason, we sought to test whether cDC1 vaccines, unlike GMDC vaccines, can function independently of host DCs to present tumor antigens directly to host T cells.

Methods

Mice

Irf8 +32−/− and Batf3−/− mice have been described previously (26,31). OT-I (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J), OT-II (C57Bl/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J), and CD45.1+ (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and bred to generated CD45.1+ OT-I and CD45.1+ OT-II mice, respectively. Kb−/−Db−/−β2m−/− mice (MHCI-TKO) (32) were a gift from Herbert W. Virgin IV and Ted Hansen (Washington University in St. Louis). Mice were maintained on the C57BL/6 background. All in vivo experiments were performed in Washington University’s specific-pathogen free facility, and both sexes were used between the ages of 8 and 16 weeks. All animals were maintained on 12-hour light cycles and housed at 70 °F (~21 °C and 50% humidity). All experiments were performed in accordance with procedures approved by the AAALAC-accredited Animal Studies Committee of Washington University in St. Louis and were in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations. All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free animal facility following institutional guidelines and with protocols approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University in St. Louis, an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Isolation and culture of BM cells

Femurs, tibias, and pelvises of naïve C57BL/6 mice were crushed using a mortar and pestle in FACs buffer [10% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 mM EDTA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)] and filtered through a 70-μm strainer. Red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed using ACK lysis buffer [150 mM NH4Cl (Sigma Aldrich), 10 mM KHCO3 (Sigma Aldrich), 0.1 mM EDTA (Sigma Aldrich)]. After RBC lysis, cells were brought up in complete IMDM [Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Gibco)] supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Corning), 1% MEM non-essential amino acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and 200 μM glutamine (Gibco) and kept at 4°C until plated for culture. GMDCs were generated by plating bone marrow cells at a density of 5 × 105/ mL in complete IMDM supplemented with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF (Peprotech) and 20 ng/mL IL4 (Peprotech) for 4 days. The cells were then isolated and spun at 1500 RPM for 5 minutes, and the cells were plated again in complete IMDM supplemented with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF and 20 ng/mL IL4 for an additional 4 days. Loosely adherent cells were collected by gentle pipetting. Cells were then sorted as SiglecH−B220– CD11c+MHCII+ into complete IMDM and kept at 4°C until used for experiments. Flt3L-cDCs were generated by plating bone marrow cells at a density of 2–2.5 × 106/mL in complete IMDM supplemented with 5% Flt3L-Fc conditioned media for 8 days. Loosely adherent cells were isolated by gentle pipetting. Cells were then sorted as SiglecH−B220–CD11c+MHCII+XCR1+Sirpa– (CD172a–) for cDC1 and SiglecH−B220–CD11c+MHCII+XCR1–Sirpa+ (CD172a+) for cDC2 into complete IMDM kept at 4°C until used for experiments. Cells were sorted using a FACS Aria Fusion instrument (BD), as indicated in the flow cytometry section, and gated as indicated above.

Tumor cell lines

The methylcholanthrene (MCA)-induced fibrosarcomas 1956 and 1969 were gifts from Robert Schreiber obtained 2012 (Washington University School of Medicine). They were generated in female C57Bl/6 mice, tested for mycoplasma, and banked at low passage as previously described (21). The immunogenic fibrosarcoma expressing membrane ovalbumin (mOVA) was generated from the MCA-induced progressor fibrosarcoma 1956 (1956 mOVA) as previously described (21) and used for all tumor experiments described herein. Tumor cells derived from frozen stocks were propagated for 1 week, with one intervening passage in vitro in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI 1640, Gibco) media supplemented with 10% FCS (HyClone), washed three times with PBS, and suspended at a density of 6.67 × 106 cells/mL in endotoxin-free PBS (Sigma-Aldrich).

Tumor models

Irf8 +32−/− or C57BL/6 wild-type micewere subcutaneously injected into the flanks with 106 1969 tumor cells, 106 1956 mOVA tumor cells or with 5 × 105 1956 mOVA tumor cells for the experiments in which mice with inoculated on both flanks. Tumor growth was measured every 3–4 days with a caliper, and tumor area was calculated by the multiplication of two perpendicular diameters. In accordance with our IACUC-approved protocol, maximal tumor diameter was 20 mm in one direction, and in no experiments was this limit exceeded. For intratumoral DC injections, 1 × 106 GMDC or Flt3L-cultured DCs were injected intratumorally or intravenously on days 1, 4, and 8 after tumor implantation and tumor growth was measured as described above. All tetramer analysis (as described below) was performed on day 15 post tumor inoculation.

For dual tumor inoculation, Irf8+32−/− mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 1956 mOVA tumor cells in both flanks. DC injections of 1 × 106 GMDCs or Flt3L-cultured DCs were injected intratumorally on days 1, 4, and 8 after tumor implantation, and tumor growth was measured as described above. All tetramer analysis (as described below) was performed on day 15 post tumor inoculation.

For memory tumor experiments, Irf8+32−/− mice were inoculated with 106 1956 mOVA tumor cells on one flank. DC injections of 1 × 106 Flt3L-cultured cDC1s (gated as described above) were injected intratumorally on days 1, 4, and 8 after tumor implantation and tumor growth was measured as described above. After primary 1956 mOVA challenge was cleared at day 16, mice were rested and rechallenged with 106 1956 mOVA tumor cells and followed for tumor growth as described above.

CD45.2+ Irf8+32−/− mice were injected subcutaneously in the flanks with 1 × 106 1956 mOVA cells. On day 4 after tumor implantation, 107 GMDCs or Flt3L-cDCs were intratumorally injected. 40 hours after DC tumor implantation, tumors and tumor-draining lymph nodes were harvested and digested in collagenase B (0.25 mg/mL) and DNaseI (30 U/mL) in complete IMDM for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Tumors and lymph nodes were then gently passed through a 19-gauge syringe until dispersed and filtered through a 70-um strainer. Cells were then stained with CD40, B220, CD11c, MHCII, XCR1, Sirpa (CD172a), CD45.1, and CD45.2 fluorescent antibodies for 30 minutes at 4°C for analysis, as indicated in the flow cytometry section.

CD8+ T-cell tetramer staining

Spleens were harvested 15 days (d) after tumor transplantation, mashed through a metal strainer, ACK lysed, and filtered through a 70-um strainer. SIINFEKL-H2-Kb biotinylated monomers were purchased from the immune-monitoring core lab at the Bursky Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Programs at Washington University in St. Louis. The peptide–MHC class I complexes refolded with an ultraviolet-cleavable conditional ligand were prepared as described with modifications as described previously (33–35). Ultraviolet-induced ligand exchange and combinatorial encoding of MHC class I multimers was performed as described (36). The peptide–MHC multimers were then incubated with APC (eBioscience), PE (Biolegend), BV605 (Biolegend), or BV710 (Biolegend) conjugated streptavidin (SA) at a concentration of 1:5 for 30 minutes at 4 °C protected from light in separate reactions. SA-labeled tetramers were then incubated with 25 µM D-biotin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 minutes at 4 °C protected from light to quench free fluorochrome-labeled SA. 3 × 106 splenocytes from tumor-bearing mice were incubated with FACS buffer supplemented with 10% of supernatant containing the Fc-blocking antibody produced from 2.4G2 cells for 5 minutes at 4 °C. Fluorochrome-conjugated tetramers were added to the splenocytes at a concentration of 3:50 and incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes. TCRβ, CD8α, CD4, B220 antibodies and the 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD, Biolegend) stain were added without washing and stained for another 30 minutes at 4 °C, as indicated in the flow cytometry section. Cells were gated as 7AAD−B220−TCRβ+CD8α+.

Tumor-specific in vivo T-cell priming assay

CD45.1+ OT-II TCR transgenic mouse lymph nodes and spleens were harvested and dispersed into single-cell suspensions by mechanical separation. All cells were combined and then stained with biotinylated Ter119, CD8β, I-A/I-E, and Ly6G antibodies in FACs buffer for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Cells were washed and incubated with MagniSort™ SAV negative selection beads (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were magnetically separated using an EasyEights EasySep Magnet (Stemcell Technologies) and sorted as B220–CD8–TCRβ+ CD4+ CD45.1+ Vα2+ (OT-II). Cells were sorted using a FACS Aria Fusion instrument (BD) as indicated in the flow cytometry section. After sorting, purified cells were labeled with 1 µM Cell Trace™ Violet proliferation dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two million labeled OT-II were transferred intravenously into C57BL/6 and Irf8 +32−/− mice bearing 1956 mOVA tumors on one flank on day 2 after tumor implantation. Tumor-draining lymph nodes were harvested on day 5 after tumor implantation (3 days after T-cell transfer) and assayed for dye dilution of CD45.1+ OT-II. Cells were stained for CD45.1, CD45.2, Vα2, 7AAD, CD4, CD44, and TCRβ in FACs Buffer. Cells were gated as CD4+TCRβ+CD45.1+Vα2+CD44+ cells and analyzed for proliferation dye dilution of CD45.1+ OT-II on a FACs CANTO II as indicated in the flow cytometry section.

In vitro T-cell proliferation assay

CD45.1+ OT-I TCR transgenic mouse lymph nodes and spleens were harvested and dispersed into single-cell suspensions by mechanical separation. All cells were combined and then stained with biotinylated Ter119, CD4, I-A/I-E and Ly6G antibodies in FACs buffer for 20 minutes at 4 °C, as indicated in the flow cytometry section. Cells were then incubated with MagniSort™ SAV negative selection beads (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were magnetically separated, as described for OT-II cells, and sorted as B220– CD8+ TCRβ+ CD4– CD45.1+ Vα2+ (OT-I). Cells were sorted using a FACS Aria Fusion instrument (BD), as indicated in the flow cytometry section. After sorting, purified cells were labeled with 1 µM Cell Trace Violet (Thermo Fisher Scientific) proliferation dye. In vitro-generated GMDCs or Flt3L-cDCs were sorted as described above, and 2.5 × 104 DCs and 2.5 × 104 labeled OT-I cells were plated into each well of a 96-well round bottom plate. Log2 dilutions of ovalbumin (OVA)-loaded splenocytes (cell-associated OVA) were plated with the DCs and T cells. Cell-associated OVA was produced by isolating MHCI TKO splenocytes and osmotically loading with 100 mg/mL soluble ovalbumin (Worthington Biochemical Corporation). Cells were x-ray irradiated at 1,350 rad and plated. After 3 days, cells were stained for TCRβ, CD8α, CD45.1, CD44 and Vα2. CD8+ TCRβ+CD45.1+ Vα2+CD44+ cells and analyzed for proliferation dye dilution of CD45.1+ OT-I, as described for OT-II.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Flow cytometry and cell sorting were completed on a FACS Canto II or FACS Aria Fusion instrument (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star). Staining was performed at 4 °C in the presence of 10% Fc block (derived from 2.4G2 cells) in magnetic-activated cell-sorting (MACS) buffer (PBS + 0.5% BSA + 2 mM EDTA). The following antibodies to the following markers were used from BD Biosciences: 7AAD, CD4 (RM4–5), CD8α (53–6.7), CD8β (53–5.8), CD11b (M1/70), B220 (RA3–6B2), CD64 (X54–5/7.1), CD19 (1D3), CD95 (Jo2), CD3 (145–2C11), CD45 (30-F11); from Tonbo Biosciences: MHCII (M5/114.15.2), CD44 (IM7), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), CD11c (N418); from Biolegend: SA-PE, SA-BV605, SA-711, XCR1 (ZET), Ter119 (Ter-119), Ly6G (1A8), TCRβ (H57–597), CD8α (53–6.7), CD4 (RMA4–5), CD44 (IM7), CD40 (1C10); from eBiosciences: SA-APC, TCRVα2 (B20.1), CD45.1 (A20), F4/80 (BM8); from Invitrogen: CD172a(P84), CD45 (30F11); from Millipore/Sigma: rabbit anti-ovalbumin (AB1225).

2.4g2 cell line

2.4g2 cells were generated previously (Unkeless, JEM 1979). For 2.4g2 supernatant, 2.4g2 cells were incubated for 3 weeks at 37 °C in 2L complete IMDM. The cells were centrifuged at 1500 RPM, and the supernatant was isolated, filtered using a 20-µm filter (Corning), and titrated for blocking of Fc receptors. Flt3L-Fc was produced from J558 myeloma cells engineered to overexpress the extracellular portion of human Flt3L fused to human Fc using the pCD4-Hg1 vector (kindly provided by Dr. Marina Cella at Washington University in St. Louis). Cells were incubated in complete IMDM in 1L roller bottles until concentration was at ~2 × 106 cells/mL. The cells were spun at 1500 RPM, and the supernatant was isolated, filtered using a 20-µm filter (Corning), and used in bone marrow culture to generate DCs. The Flt3L-Fc cultured supernatant was compared and equivalent to 100 ng/mL Flt3L(Peprotech) for in vitro DC generation.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software version 8. Unless otherwise noted, one-way ANOVA was used to determine significant differences between samples, and all center values correspond to the mean. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Randomization was performed as comparisons were done across mice of the same genotypes receiving different treatments. No formal randomization was done across all other samples. Investigators were blinded to the treatments of the mice during sample preparation and data collection.

Data Availability

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Results

Irf8 32−/− mice lack endogenous cDC1 and fail to reject immunogenic tumors

We previously generated mice harboring deletions in the +32 kb enhancer of Irf8 that engages IRF8:BATF3 complexes to stabilize Irf8 transcription in the specified pre-cDC1 progenitor (31). Irf8 +32−/− mice lacked cDC1 in all peripheral lymphoid tissues (31), including the spleen (Fig. 1A). The Irf8 +32−/− enhancer deletion does not affect Batf3 expression (31), but provides a superior model of cDC1 deficiency compared with Batf3−/− mice, in which germline Batf3 deficiency can impact other immune lineages (37), and in which cDC1 development is restored in certain conditions by compensation from Batf and Batf2 (38). We previously described the immunogenic fibrosarcoma 1956 mOVA, which is rejected by wild-type B6 (WT) mice by mechanisms involving licensing of cDC1 by CD4+ T cells (21). Here, we confirmed that Irf8 +32−/− mice did not reject 1956 mOVA (Fig. 1B), indicating that rejection of this tumor relies on cDC1. Therefore, we used 1956 mOVA tumors and Irf8 +32−/− mice to test whether cell-based vaccines could directly present antigens to host T cells because any CD8+ T cell response induced by DC vaccines in Irf8 +32−/− mice must be generated by the vaccine itself, and not antigen transfer to host cDC1.

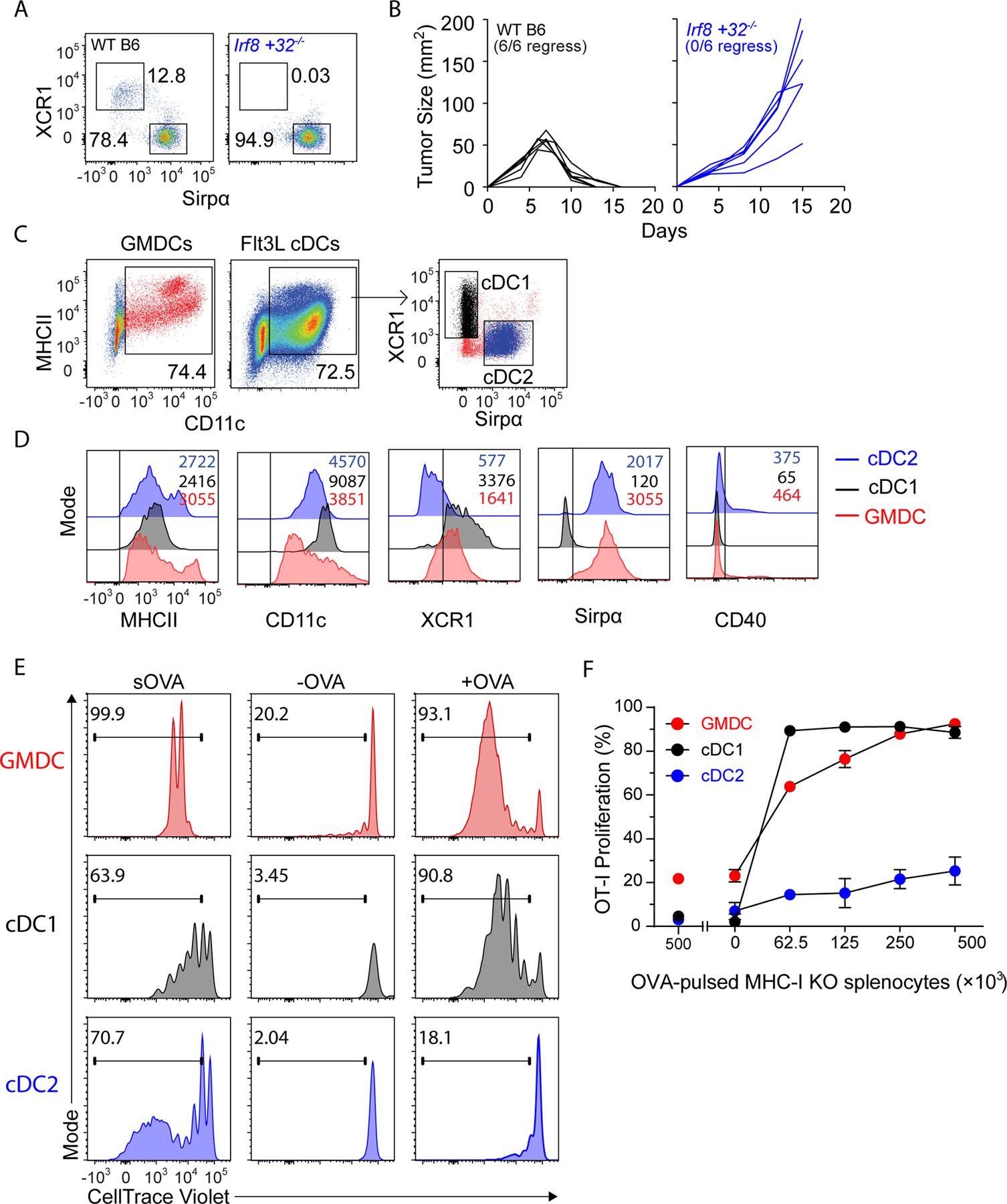

Figure 1. GMDCs and Flt3L-cDC1 cross-present cell-associated antigen in vitro.

(A) Representative flow plots of 3 WT B6 (left) and 3 Irf8 +32−/− (right) splenic DCs gated as B220−CD11c+MHCII+. (B) WT B6 (black, n=6) and Irf8+32−/− (blue, n=6) mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA cells and followed for tumor growth. (C) Gating strategy for GMDCs, cDC1, and cDC2. (D) Surface expression of in vitro GMDCs (red), Flt3L-cDC1 (black), and Flt3L-cDC2 (blue). (E) Proliferation of OVA-specific OT-I CD8+ T cells in response to GMDCs (red), Flt3L-cDC1 (black), or Flt3L-cDC2 (blue) and either soluble OVA (sOVA), control PBS-loaded MHCI TKO splenocytes (-OVA), or OVA-loaded MHCI TKO splenocytes (+OVA). Shown are representative histograms of cell trace violet (CTV) intensity on OT-I cells gated as CD45.1+TCRβ+Vα2+CD44+ after 3 days of culture. (F) Proliferation of OVA-specific OT-I CD8+ T cells in response to OVA-loaded splenocytes presented by GMDCs (red), Flt3L-cDC1 (black), or Flt3L-cDC2 (blue). Representative data from one of three independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent S.D.

GMDCs and Flt3L-derived cDC1 can cross-present cell-associated antigens in vitro

Current strategies generate DC vaccines by culturing monocytes or BM with GM-CSF, with or without IL4, producing large numbers of CD11c+MHCII+ cells (GMDCs) (Fig. 1C). By contrast, culturing BM with FL3L generates CD11c+MHCII+ cells containing XCR1+Sirpα− cells (cDC1) and XCR1−Sirpα+ cells (cDC2, Fig. 1C). GMDCs, like cDC2, expressed Sirpα but expressed XCR1 at levels intermediate between cDC1 and cDC2, and none expressed CD40 in culture (Fig. 1D). GMDCs, cDC1, and cDC2 were all able to process and present soluble ovalbumin (sOVA) to OT-I CD8+ T cells. In contrast, GMDCs and cDC1, but not cDC2, were able to process and present cell-associated OVA to OT-I CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1E–F).

Intratumoral vaccination with cDC1, but not GMDCs, induces tumor rejection in Irf8 +32−/− mice

We previously reported that the fibrosarcoma 1956 mOVA is rejected by C57BL/6 mice, but not by Irf8 +32−/− mice (21). To test whether vaccines based on Flt3L-cDCs could directly prime host T cells in vivo, we generated cDC1, cDC2, and GMDCs in vitro and injected these cells subcutaneously into tumors growing in Irf8 +32−/− mice (Fig. 2A) and monitored tumor growth (Fig. 2B). Injection of GMDCs and cDC2 into tumors did not affect tumor growth compared to the PBS negative controls. By contrast, injection of cDC1 led to regression of tumors in 9 of 11 mice (Fig. 2B). As a control, we showed that B6 mice inoculated with 1956 mOVA and administered intratumoral GMDC injections also rejected tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1A), as expected.

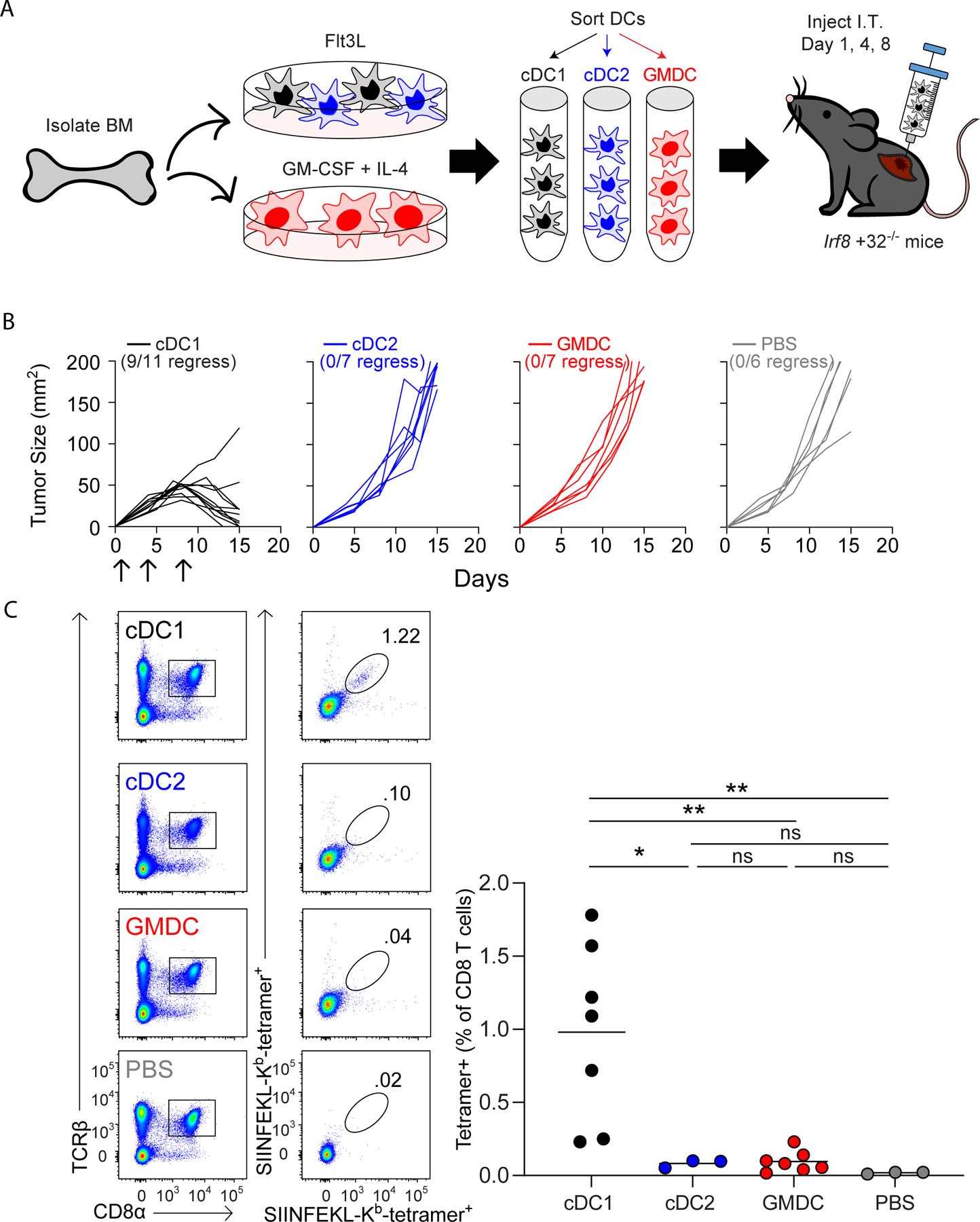

Figure 2. Vaccination with cDC1, but not GMDCs, induces anti-tumor immunity independently of host cDC1.

(A) Scheme of WT B6 bone marrow culture for DC injections on day 1, 4, and 8 after tumor inoculation. (B) Irf8+32−/− mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA cells, intratumorally injected with 106 Flt3L-cDC1 (black, n=11), 106 Flt3L-cCD2 (blue, n=7), 106 GMDC (red, n=7), or PBS (grey, n=6) as indicated in (A) and followed for tumor growth. (C) Irf8+32−/− mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA cells, and spleens were stained for the presence of SIINFEKL-Kb tetramer+CD8+ T cells on day 15 after tumor inoculation. Left, representative flow plots of percentages of tetramer+CD8+ T cells. Right, tetramer+CD8+ T cells as a percentage of all CD8+ T cells. Data represent pooled biologically independent samples from three independent experiments (n=7 for Flt3L-cDC1, n=3 for Flt3L-cDC2, n=7 for GMDCs, and n=3 for PBS). **P≤0.01, *P≤0.05, one-way ANOVA.

In many human cancers, neoantigens may be difficult to identify, particularly for immunodominant neo-epitopes (39). Therefore, to extend our results to a second a second tumor model system, we examined the ability of cDC1 vaccines to induce rejection of the 1969 fibrosarcoma, which does not exogenously express OVA. As above, cDC1, cDC2, and GMDCs were generated in vitro and injected subcutaneously into 1969 tumors growing in Irf8 +32−/− mice. Again, in this model, cDC1 vaccination induced tumor rejection of 1969 fibrosarcomas growing in Irf8 +32−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S1B). By contrast, GMDCs or cDC2 vaccination failed to induce tumor rejection, which was in agreement with results for the 1956 mOVA tumor model (Fig. 2B).

CD8+ T-cell responses to 1956 mOVA can be monitored using an H-2Kb-SIINFEKL MHC-I tetramer (21). Injection of GMDCs, cDC2, and PBS failed to generate an endogenous CD8+ T-cell response, whereas injection of cDC1 expanded tetramer+CD8+ T cells substantially (Fig. 2C). These findings agree with previous reports that monocyte-derived GMDC vaccines rely on host cDCs for induction of anti-tumor immunity (18–20). However, we now show for the first time that cDC1 vaccines are able to directly present tumor-derived antigens to host CD8+ T cells in vivo in the absence of all endogenous cDC1.

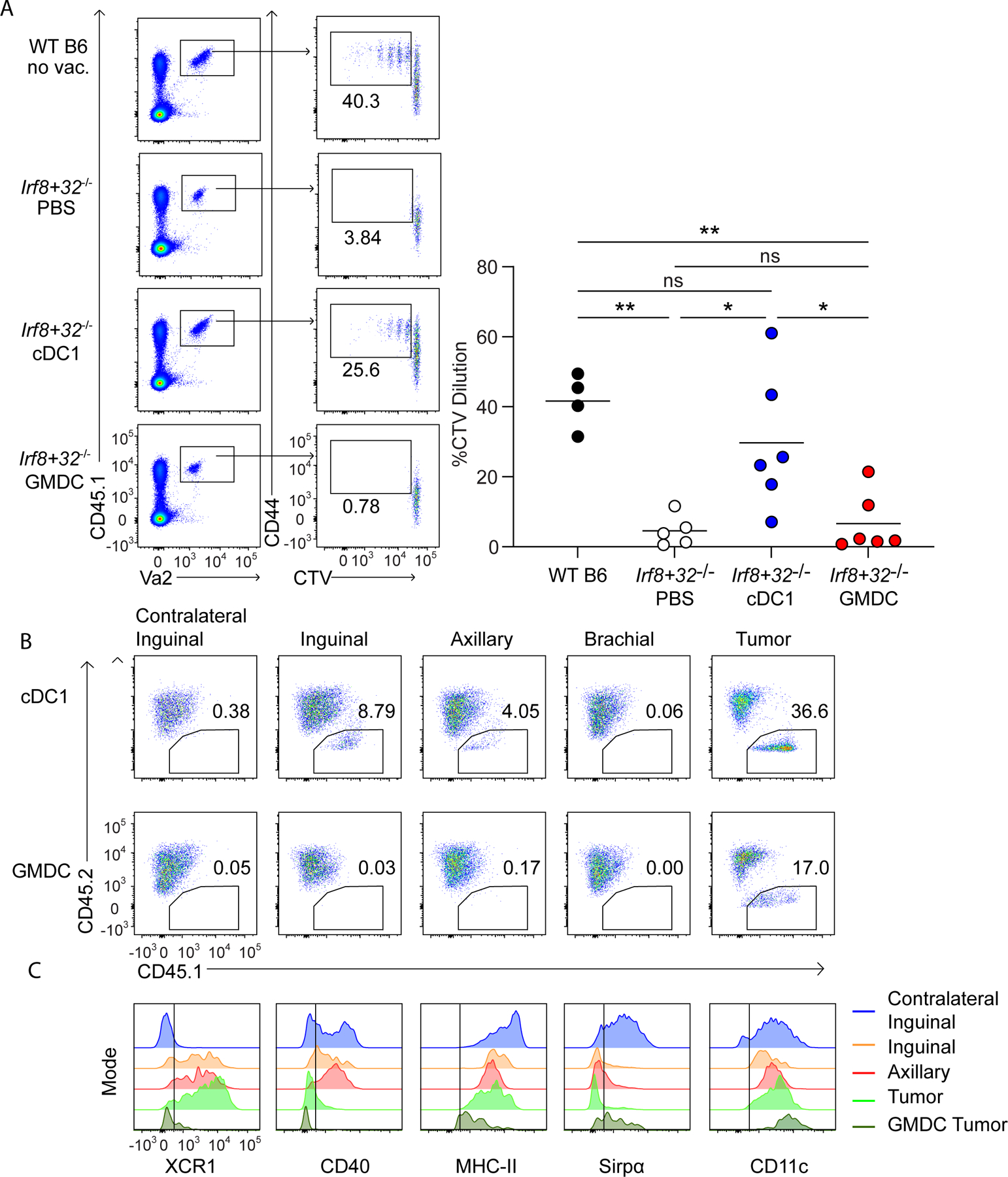

cDC1, but not GMDCs, activate tumor-specific CD4+ T cells and migrate to tumor-draining LNs

We next asked whether vaccination with cDC1 and GMDCs could activate anti-tumor CD4+ T cells. WT or Irf8 +32−/− mice were inoculated with 1956 mOVA tumor cells and vaccinated with cDC1s, cDC2s, GMDCs, or with PBS as a negative control. After 2 days, OT-II CD4+ T cells labeled with Cell Trace Violet (CTV) were administered intravenously and analyzed 3 days later (Fig. 3A). In WT B6 mice, significant OT-II proliferation occurred, even without vaccination, consistent with the spontaneous tumor rejection in these mice. In contrast, in Irf8 +32−/− mice receiving PBS virtually had no OT-II proliferation. This result is consistent with our previous report showing that cDC1 are required for early CD4+ T-cell activation by 1956 mOVA (21). However, robust OT-II proliferation was induced in tumor-bearing Irf8+32−/− mice with cDC1 vaccination, but not with GMDC vaccination. For CD8+ T-cell responses, we demonstrated that vaccination with Flt3L-cDC1 led to direct presentation of tumor-derived antigens to host T cells without transfer to host DCs (Fig. 2).

Figure 3. cDC1, but not GMDCs, migrate to lymph nodes to activate T cells.

(A) WT B6 and Irf8+32−/− mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA, and OT-II cells were transferred intravenously (i.v.) on day 2 after tumor inoculation. Left, representative flow plots of proliferating OT-II T cells three days after transfer. Right, percentages of proliferating OT-II cells transferred. Data are pooled biologically independent samples from two independent experiments (n=5 for PBS Irf8+32−/−, n=4 for WT B6, and n=6 for all other groups). **P≤0.01, *P≤0.05, one-way ANOVA. (B) CD45.2+ Irf8+32−/− mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA. On day 4 after tumor inoculation, 107 CD45.1+ Flt3L-cDC1 (top panels) or 107 CD45.1+ GMDC (bottom panels) were injected intratumorally. 40 hours after DC injection, the skin draining lymph nodes and tumors were isolated and stained for presence of injected DCs. (C) Surface expression of injected Flt3L-cDC1 in inguinal (orange), axillary (red), tumor (light green), and injected GMDCs isolated from the tumor (dark green). Contralateral lymph node DCs gated on endogenous cDC2 (blue) are shown as a comparison.

Because GMDC vaccination failed to activate OT-II T cells in draining LNs, we asked whether they could migrate from the injection site to local LNs (Fig. 3B). To test this, we generated Flt3L-cDC1 or GMDCs from CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice and vaccinated CD45.2+ Irf8 +32−/− mice previously inoculated with 1956 mOVA. After two days, we assessed migration of CD45.1 cells into LNs (Fig. 3B). As a positive control, we were able to identify CD45.2+ cells remaining at the tumor vaccination site after vaccination with cDC1 and GMDCs. After cDC1 vaccination, we identified CD45.1+ cDC1 in tumor-draining inguinal and axillary LNs, but not in the non-draining brachial LNs or contralateral inguinal LNs. In contrast, after GMDC vaccination, we could not identify CD45.1+ GMDCs in any LNs, suggesting reduced migratory capacity relative to cDC1. cDC1 remaining at the tumor site did not express CD40, whereas cDC1 that migrated to LNs expressed CD40 while retaining XCR1, MHCII, and CD11c expression (Fig. 3C).

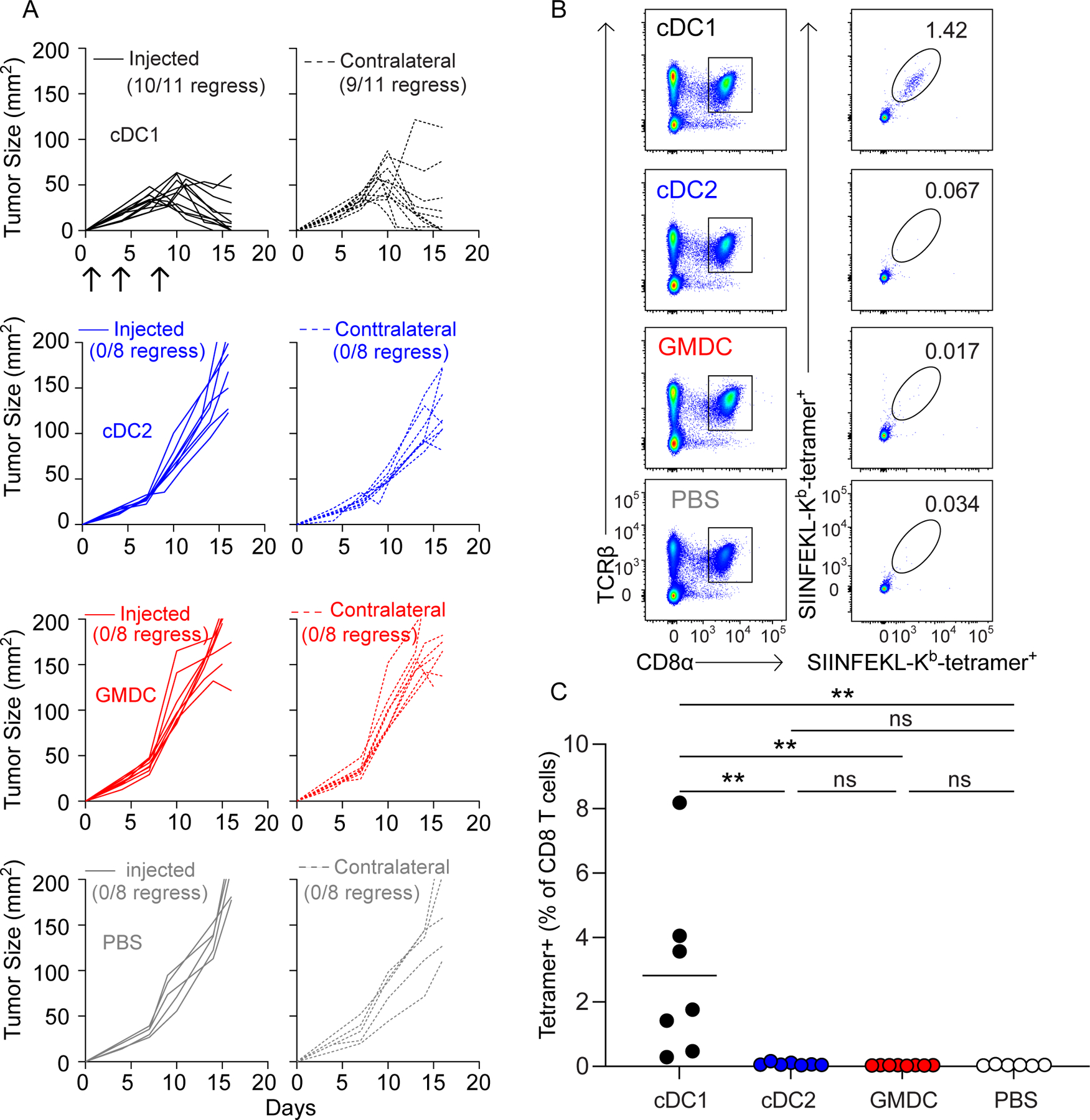

Intratumoral cDC1 vaccination induces abscopal tumor rejection

A study suggests that cDC1 may be required within the tumor microenvironment (TME) in order to recruit tumor-specific T cells (40). We, therefore, asked whether cDC1 were required within the TME in the setting of endogenous T-cell responses and if cDC1 vaccination induced abscopal rejection of unvaccinated tumors in Irf8+32−/− mice (Fig. 4A). 1956 mOVA was inoculated into both flanks of Irf8+32−/− mice on day 0, followed by intratumoral vaccination on only one side with GMDCs, Flt3L-cDC1, Flt3L-cDC2, or PBS on days 1, 4 and 8. As before, vaccination with cDC1, but not GMDCs or cDC2, caused rejection of vaccinated tumors. cDC1 vaccination on one side also caused rejection of tumors on the contralateral, unvaccinated flank. Again, vaccination with cDC1, but not GMDCs or cDC2s, expanded H-2Kb-SIINFEKL tetramer+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4B–C). cDC1 were not present in unvaccinated tumors of Irf8+32−/− mice, suggesting that induction of T-cell responses was sufficient for mediating effective anti-tumor immunity without a requirement for cDC1 in the TME.

Figure 4. Flt3L-cDC1 induce abscopal tumor rejection in Irf8+32−/− mice that lack endogenous cDC1.

(A) Irf8+32−/− mice were injected in both flanks with 5 × 105 1956 mOVA and one flank received intratumoral injections of PBS (grey, n=8) or 106 GMDCs (red, n=8), Flt3L-cDC1 (black, n=11), or Flt3L-cDC2 (blue, n=8)and the other flank received no DC injections Tumor growth curves of DC-injected tumors are solid lines (left), and tumor growth curves of uninjected tumors are dashed lines (right). (B-C) Irf8+32−/− mice were injected in both flanks with 5 × 105 1956 mOVA and one flank received intratumoral injections of 106 DCs as in (A). Splenocytes were stained for the presence of SIINFEKL-Kb tetramer+CD8+ T cells on day 15 after tumor inoculation. (B) Representative flow plots of percentages of tetramer+CD8+ T cells. (C) Tetramer+CD8+ T cells as a percentage of all CD8+ T cells. Data represent pooled biologically independent samples from three independent experiments (n=7 for Flt3L-cDC1, n=7 for Flt3L-cDC2, n=9 for GMDCs, and n=6 for PBS). **P≤0.01, *P≤0.05, one-way ANOVA.

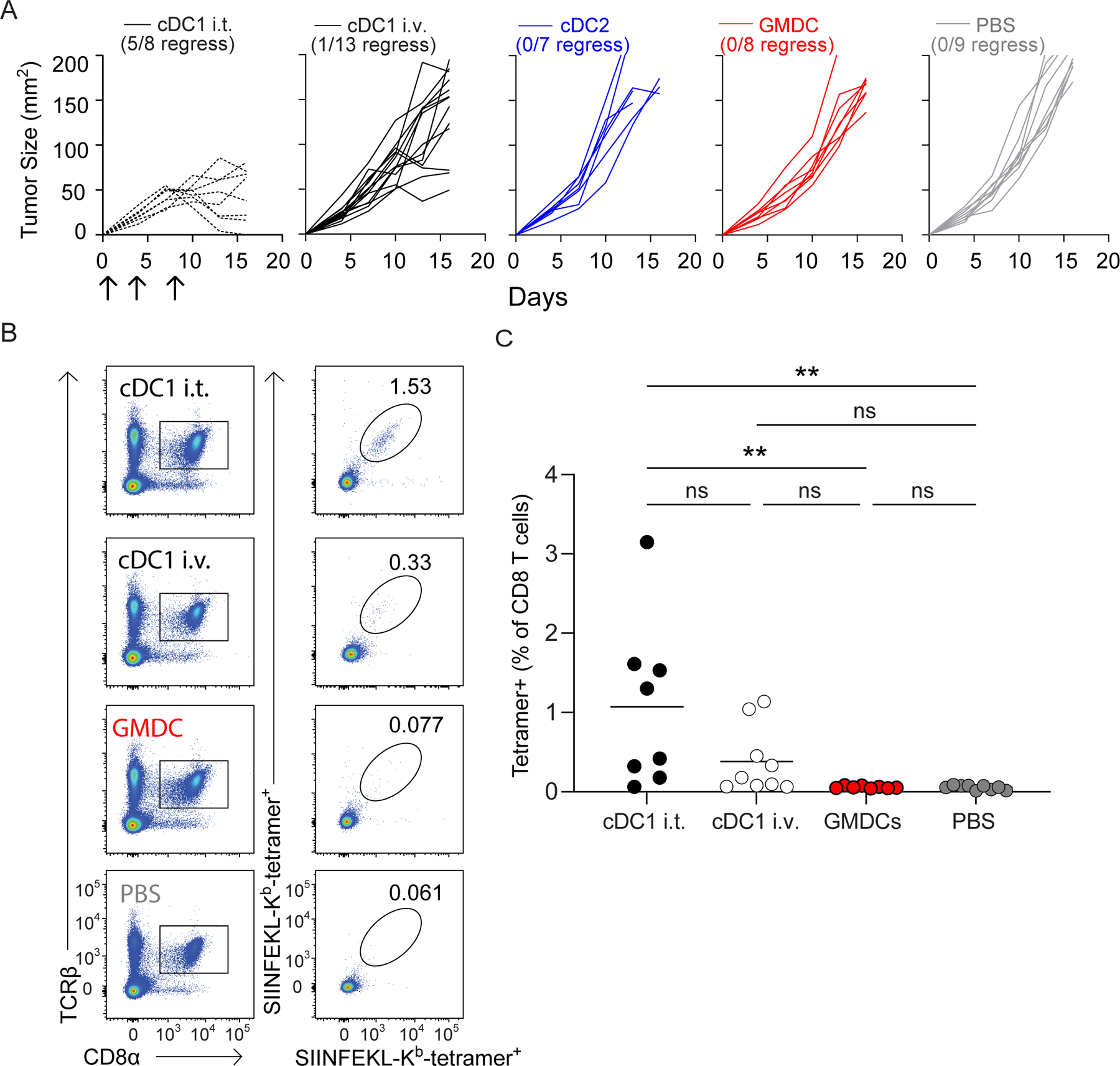

Because direct inoculation of cDC1 into tumors allowed sufficient antigen capture and transport to LNs to induce effective antitumor immunity, we asked whether intravenous vaccine infusion would be as effective. For this, we delivered GMDCs, Flt3L-cDC1s, and Flt3L-cDC2s intravenously into Irf8+32−/− mice harboring 1956 mOVA (Fig.5). However, none of these conditions were sufficient to induce responses that could eliminate tumors (Fig. 5A), and only a small increase in H-2Kb-SIINFEKL tetramer+CD8+ T cells was observed (Fig. 5B–C).

Figure 5. Intravenous vaccination with cDC1 does not induce anti-tumor immunity.

(A) Irf8+32−/− mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA cells and followed for tumor growth. Tumor growth curves of 1956 mOVA in Irf8+32−/− mice intratumorally injected with 106 Flt3L-cDC1 (dashed black, n=8) or intravenously injected with 106 Flt3L-cDC1 (black, n=11), 106 Flt3L-cCD2 (blue, n=7), 106 GMDC (red, n=8), or PBS (grey, n=9). (B-C) Irf8+32−/− mice were injected with 106 1956 mOVA cells, and splenocytes were stained for the presence of SIINFEKL-Kb tetramer+CD8+ T cells on day 15 after tumor inoculation. (B) Representative flow plots of percentages of tetramer+CD8 T cells. (C) Tetramer+CD8+ T cells as a percentage of all CD8+ T cells. Data represent pooled biologically independent samples from three independent experiments (n = 8 for IT cDC1, n = 9 for IV cDC1, n = 8 for GMDC, and n = 9 for PBS). **P≤0.01, one-way ANOVA.

cDC1 are not required for memory T cell response against 1956 mOVA

Previously, DCs (41), and specifically cDC1 (42), were found to be required for optimal memory T-cell responses. However, whether tumor rejection requires optimized T-cell memory, or alternately can be achieved without cDC1-dependent restimulation is unknown. Therefore, we asked whether cDC1 were also required for anti-tumor memory responses. We inoculated Irf8+32−/− mice with 1956 mOVA and administered the cDC1 vaccine as above (Fig. 2). As before, tumors were eliminated in all mice, which were then rested. After 3 weeks, these mice were re-inoculated with 1956 mOVA on the contralateral flank and followed for tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. S1C). No residual cDC1 were present, and mice were not re-injected with the cDC1 vaccine. Nonetheless, the previously vaccinated Irf8+32−/− mice showed complete rejection of secondary 1956 mOVA tumors. As controls, unvaccinated WT B6 mice, but not unvaccinated Irf8+32−/− mice, also rejected 1956 mOVA tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1D). These results suggest that in the setting of 1956 mOVA fibrosarcomas, the effector memory population is sufficient to re-initiate direct tumor rejection independently of endogenous cDC1. These results do not indicate how long such anti-tumor immunity might last, but do suggest that some persistence of effector memory T-cell memory for at least 3 weeks.

Discussion

Studies have identified several important differences between DCs derived from in vitro GM-CSF stimulation and conventional DCs developing naturally in vivo or from Flt3L-treated BM cultures (3,4,43,44). Once considered homogeneous, work show that GM-CSF-derived DC systems actually produce heterogeneous populations, containing cells with features of both macrophages and DCs (3). The behavior of these cells differed from that of cDC1 in several ways. Although cDC1 require Irf8 and Batf3 for their development, GM-CSF-derived DCs require Irf4 and are independent of Batf3 (4). cDC1 rely on Rab43 to support cross-presentation, whereas GM-CSF-derived DCs do not (43). Likewise, Wdfy4 is required for cross-presentation of cell-associated antigens by cDC1, but not by GM-CSF-derived DCs (44). In summary, substantial differences exist in the biologic behavior of GM-CSF derived DCs and native or cultured cDC1.

DC vaccination using GM-CSF-derived cells was originally thought to be mediated by direct presentation to host T cells. However, accumulating evidence has shown that host cDCs are required to mediate the effect of GMDC vaccines (18–20). First, a requirement for MHC-II expression on host cDCs was recognized as being required for responses induced by GMDC vaccines (18), indicating an indirect action at least for CD4+ T-cell activation. Later, a similar requirement was found for CD8+ T cells in a model using OT-I T cells (19). A study using OVA-loaded monocytes as a vaccine showed that CD8+ T-cell activation induced by OVA-peptide bearing monocytes was impaired in Batf3−/− mice (20), which lack cDC1 development (26). A previous study used Batf3−/− mice as a platform to test a vaccine’s reliance on host cDC1 cells (20). However, cDC1 development in Batf3−/− mice can be restored under certain conditions due to compensation by Batf and Batf2, as we previously reported (38). This indicates that Batf3−/− mice are not an optimal system to determine a response’s reliance on endogenous cDC1 because a restored host cDC1, rather than vaccine, could be responsible for direct T-cell activation. We previously developed an alternative method to eradicate cDC1 development. Deletion of the Irf8 +32kb enhancer eliminates BATF3-mediated Irf8 autoactivation that normally occurs in the specified pre-cDC1 progenitor and is required for commitment to the cDC1 lineage (31). cDC1 are completely missing in Irf8 +32−/− mice and are not restored in any of the conditions that could restore cDC1 development in Batf3−/− mice (31). Thus, Irf8 +32−/− mice represent a robust platform to test the requirement for host cDC1 in the action of DC vaccines. Our results clearly demonstrated that the cDC1 used for vaccination could enter the tumor, capture antigens, and migrate to local LNs to directly prime CD8+ T cells. Using a system of Xcr1-Cre mediated gene targeting in vivo, we previously found that for cell-associated tumor antigens, cDC1 are not only responsible priming CD8+ T cells, but are also the predominant APC responsible for priming CD4 T cells (21). In agreement, here, we found that cDC1 used for vaccination could migrate to tumor-draining LNs and stimulate OVA-specific CD4+ T cells. By contrast, in this system, GMDCs did migrate efficiently to tumor-draining LNs.

In the system used here, injection of the cDC1 vaccine directly into growing tumors allowed sufficient antigen capture to drive effective antitumor immunity, which was capable of eliminating not only tumors at the cDC1 vaccine injection site, but also the unvaccinated tumors growing concurrently on the opposite flank. That this abscopal effect occurred in Irf8 +32−/− mice suggests that cDC1 vaccination generated effective antitumor immunity in draining LNs that is sufficient to achieve elimination without cDC1 being present at the tumor site.

A recent study suggests that cDC1 may be required in the TME to recruit tumor-specific T cells by producing chemokines such as CXCL10 (40). Mixed BM chimeras that either lack or possess endogenous cDC1 were treated with DTA to deplete cDCs, followed by adoptive transfer of in vitro-activated 2C T cells expressing cerulean fluorescent protein (CFP) In mice lacking cDC1, very few 2C T cells were found, whereas in chimeras with cDC1, 2C T cells were abundant in the TME (40). In contrast, in our study here, the abscopal rejection of opposite flank tumors occurred in the absence of cDC1 within the TME. Nonetheless, there are many differences between the systems used in the previous study (40) and ours, and it is plausible that the requirement for cDC1 in the TME may vary between different model systems. Intravenous vaccination with cDC1 did not induce sufficient anti-tumor immune responses for tumor rejection. This result may be due to a dilution of the numbers of cDC1 that reached the tumor, but also could point to an effect of tissue-imprinting on the cDC1’s ability to mount sufficient anti-tumor immunity. Resolving this issue will require additional studies.

In summary, this study showed that vaccines based on cDC1 and GMDCs differ substantially in their mechanism of action. GMDC vaccines were unable to migrate to LNs from tumors to LNs to directly prime host T cells, and so rely on antigen transfer to host DCs. In contrast, intratumoral cDC1 vaccines were able to capture tumor antigens, migrate to LNs, and directly prime host T cells. This difference supports the further interest in developing vaccines based on Flt3L-derived cDC1 as a possible therapeutic avenue for the future.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

Flt3L-derived cDC1 are demonstrated to be superior to GM-CSF-generated DCs as a cell-based vaccine. Flt3L-cDC1 acquire tumor antigen, migrate to tumor-draining lymph nodes, and directly prime anti-tumor T-cell responses. The data highlight the potential to be cancer therapeutic.

Acknowledgements:

This publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was supported by the NIH (R01AI150297, R01CA248919, and R21AI164142 to K.M.M., R01CA240983 TO R.D.S, and F30CA247262-01A1 to R.W.) S.T.F. and X.H. are Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellows supported by the Cancer Research Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: RDS is a co-founder, paid consultant and stockholder of Jounce Therapeutics and Asher Biotherapeutics and paid consultant and stockholder of A2 Biotherapeutics, Arch oncology, Codiak Biosciences, NGM Biotherapeutics, Sensei Biotherapeutics, and GlaxoSmithKline. KMM is a paid member of the scientific advisory board of Harbour BioMed.

References

- 1.Markowicz S and Engleman EG. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes differentiation and survival of human peripheral blood dendritic cells in vitro. J Clin.Invest 1990;85:955–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sims RB. Development of sipuleucel-T: autologous cellular immunotherapy for the treatment of metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer. Vaccine 2012;30:4394–4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helft J, Bottcher J, Chakravarty P, Zelenay S, Huotari J, Schraml BU et al. GM-CSF Mouse Bone Marrow Cultures Comprise a Heterogeneous Population of CD11c(+)MHCII(+) Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2015;42:1197–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briseno CG, Haldar M, Kretzer NM, Wu X, Theisen DJ, KC W et al. Distinct Transcriptional Programs Control Cross-Priming in Classical and Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. Cell Rep 2016;15:2462–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp.Med 1992;176:1693–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, and Banchereau J. GM-CSF and TNF-alpha cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature 1992;360:258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallusto F and Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp.Med 1994;179:1109–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burch PA, Breen JK, Buckner JC, Gastineau DA, Kaur JA, Laus RL et al. Priming tissue-specific cellular immunity in a phase I trial of autologous dendritic cells for prostate cancer. Clin.Cancer Res 2000;6:2175–2182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Small EJ, Fratesi P, Reese DM, Strang G, Laus R, Peshwa MV et al. Immunotherapy of hormone-refractory prostate cancer with antigen-loaded dendritic cells. J Clin.Oncol 2000;18:3894–3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N.Engl.J.Med 2010;363:411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himoudi N, Wallace R, Parsley KL, Gilmour K, Barrie AU, Howe K et al. Lack of T-cell responses following autologous tumour lysate pulsed dendritic cell vaccination, in patients with relapsed osteosarcoma. Clin.Transl.Oncol 2012;14:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carreno BM, Magrini V, Becker-Hapak M, Kaabinejadian S, Hundal J, Petti AA et al. Cancer immunotherapy. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science 2015;348:803–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bol KF, Aarntzen EH, Hout FE, Schreibelt G, Creemers JH, Lesterhuis WJ et al. Favorable overall survival in stage III melanoma patients after adjuvant dendritic cell vaccination. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1057673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreibelt G, Bol KF, Westdorp H, Wimmers F, Aarntzen EH, Duiveman-de Boer T et al. Effective Clinical Responses in Metastatic Melanoma Patients after Vaccination with Primary Myeloid Dendritic Cells. Clin.Cancer Res 2016;22:2155–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross S, Erdmann M, Haendle I, Voland S, Berger T, Schultz E et al. Twelve-year survival and immune correlates in dendritic cell-vaccinated melanoma patients. JCI.Insight 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miwa S, Nishida H, Tanzawa Y, Takeuchi A, Hayashi K, Yamamoto N et al. Phase 1/2 study of immunotherapy with dendritic cells pulsed with autologous tumor lysate in patients with refractory bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2017;123:1576–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena M and Bhardwaj N. Re-Emergence of Dendritic Cell Vaccines for Cancer Treatment. Trends Cancer 2018;4:119–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleindienst P and Brocker T. Endogenous dendritic cells are required for amplification of T cell responses induced by dendritic cell vaccines in vivo. J Immunol 2003;170:2817–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yewdall AW, Drutman SB, Jinwala F, Bahjat KS, and Bhardwaj N. CD8+ T cell priming by dendritic cell vaccines requires antigen transfer to endogenous antigen presenting cells. PLoS One 2010;5:e11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang MN, Nicholson LT, Batich KA, Swartz AM, Kopin D, Wellford S et al. Antigen-loaded monocyte administration induces potent therapeutic antitumor T cell responses. J Clin.Invest 2020;130:774–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferris ST, Durai V, Wu R, Theisen DJ, Ward JP, Bern MD et al. cDC1 prime and are licensed by CD4(+) T cells to induce anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2020;584:624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy TL, Grajales-Reyes GE, Wu X, Tussiwand R, Briseno CG, Iwata A et al. Transcriptional Control of Dendritic Cell Development. Annu.Rev Immunol 2016;34:93–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durai V and Murphy KM. Functions of Murine Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2016;45:719–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson DA III, Dutertre CA, Ginhoux F, and Murphy KM. Genetic models of human and mouse dendritic cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.den Haan JM, Lehar SM, and Bevan MJ. CD8(+) but not CD8(−) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp.Med 2000;192:1685–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science 2008;322:1097–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts EW, Broz ML, Binnewies M, Headley MB, Nelson AE, Wolf DM et al. Critical Role for CD103+/CD141+ Dendritic Cells Bearing CCR7 for Tumor Antigen Trafficking and Priming of T Cell Immunity in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wculek SK, Amores-Iniesta J, Conde-Garrosa R, Khouili SC, Melero I, and Sancho D. Effective cancer immunotherapy by natural mouse conventional type-1 dendritic cells bearing dead tumor antigen. J Immunother.Cancer 2019;7:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y, Slone N, Chrisikos TT, Kyrysyuk O, Babcock RL, Medik YB et al. Vaccine efficacy against primary and metastatic cancer with in vitro-generated CD103(+) conventional dendritic cells. J Immunother.Cancer 2020;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruhland MK, Roberts EW, Cai E, Mujal AM, Marchuk K, Beppler C et al. Visualizing Synaptic Transfer of Tumor Antigens among Dendritic Cells. Cancer Cell 2020;37:786–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durai V, Bagadia P, Granja JM, Satpathy AT, Kulkarni DH, Davidson JT et al. Cryptic activation of an Irf8 enhancer governs cDC1 fate specification. Nat Immunol 2019;20:1161–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lybarger L, Wang X, Harris MR, Virgin HW, and Hansen TH. Virus subversion of the MHC class I peptide-loading complex. Immunity 2003;18:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toebes M, Coccoris M, Bins A, Rodenko B, Gomez R, Nieuwkoop NJ et al. Design and use of conditional MHC class I ligands. Nat Med 2006;12:246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alspach E, Lussier DM, Miceli AP, Kizhvatov I, DuPage M, Luoma AM et al. MHC-II neoantigens shape tumour immunity and response to immunotherapy. Nature 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, Caron E, Ward JP, Noguchi T et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature 2014;515:577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen RS, Kvistborg P, Frosig TM, Pedersen NW, Lyngaa R, Bakker AH et al. Parallel detection of antigen-specific T cell responses by combinatorial encoding of MHC multimers. Nat Protoc 2012;7:891–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwata A, Durai V, Tussiwand R, Briseno CG, Wu X, Grajales-Reyes GE et al. Quality of TCR signaling determined by differential affinities of enhancers for the composite BATF-IRF4 transcription factor complex. Nat Immunol 2017;18:563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tussiwand R, Lee WL, Murphy TL, Mashayekhi M, Wumesh KC, Albring JC et al. Compensatory dendritic cell development mediated by BATF-IRF interactions. Nature 2012;490:502–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capietto AH, Jhunjhunwala S, and Delamarre L. Characterizing neoantigens for personalized cancer immunotherapy. Curr.Opin.Immunol 2017;46:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spranger S, Dai D, Horton B, and Gajewski TF. Tumor-Residing Batf3 Dendritic Cells Are Required for Effector T Cell Trafficking and Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Cancer Cell 2017;31:711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zammit DJ, Cauley LS, Pham QM, and Lefrancois L. Dendritic cells maximize the memory CD8 T cell response to infection. Immunity 2005;22:561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Low JS, Farsakoglu Y, Amezcua Vesely MC, Sefik E, Kelly JB, Harman CCD et al. Tissue-resident memory T cell reactivation by diverse antigen-presenting cells imparts distinct functional responses. J Exp.Med 2020;217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kretzer NM, Theisen DJ, Tussiwand R, Briseno CG, Grajales-Reyes GE, Wu X et al. RAB43 facilitates cross-presentation of cell-associated antigens by CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp.Med 2016;213:2871–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Theisen DJ, Davidson JT, Briseno CG, Gargaro M, Lauron EJ, Wang Q et al. WDFY4 is required for cross-presentation in response to viral and tumor antigens. Science 2018;362:694–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.