Summary:

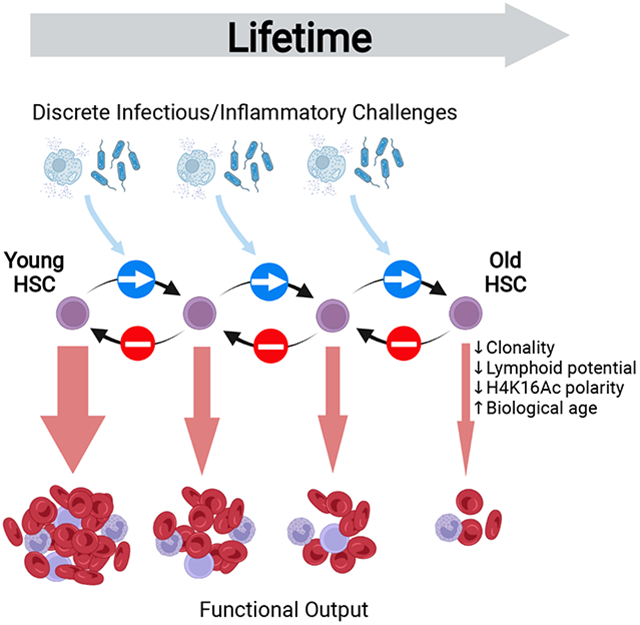

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mediate regeneration of the hematopoietic system following injury, such as following infection or inflammation. These challenges impair HSC function, but whether this functional impairment extends beyond the duration of inflammatory exposure is unknown. Unexpectedly, we observed an irreversible depletion of functional HSCs following challenge with inflammation or bacterial infection, with no evidence of any recovery up to one year afterwards. HSCs from challenged mice demonstrated multiple cellular and molecular features of accelerated aging, and developed clinically-relevant blood and bone marrow phenotypes not normally observed in aged laboratory mice, but commonly seen in elderly humans. In vivo HSC self-renewal divisions were absent or extremely rare during both challenge and recovery periods. The progressive, irreversible attrition of HSC function demonstrates that temporally discrete inflammatory events elicit a cumulative inhibitory effect on HSCs. This work positions early/mid-life inflammation as a mediator of lifelong defects in tissue maintenance and regeneration.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Inflammation and infection acutely suppress HSC function. However, the long-term ramifications of such challenges are unclear. This study demonstrates that murine HSCs fail to recover functional potency up to one-year post-inflammatory/infection challenge, meaning that such events can have accumulative effects over a lifetime; this promotes acquisition of the aged state.

Introduction:

In the context of injury, infection and autoimmune conditions, mature blood cells are classically defined as both a major source of inflammatory cytokines and as critical downstream effectors of the inflammatory response. However, it has become clear that immature hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells also react to inflammatory cues (Clapes et al., 2016; King and Goodell, 2011). Indeed, multiple different sterile and infection-associated inflammatory stimuli have been shown to provoke primitive hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to exit their long-term quiescent state and enter into active proliferation (Baldridge et al., 2010; Essers et al., 2009; Hormaechea-Agulla et al., 2021; Takizawa et al., 2011). Conceptually, it has been postulated that these so-called “dormant” HSCs act as a life-long emergency reserve of highly potent cells, that can be transiently stimulated to produce mature blood cells during instances of severe hematopoietic stress, following which they return to their dormant state (Essers et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2008). However, numerous studies have also documented that inflammation-associated stress hematopoiesis can result in functional impairment of HSCs, with observed effects including decreased repopulation potential following transplantation and myeloid-skewed differentiation (Esplin et al., 2011; Matatall et al., 2016; Pietras et al., 2016; Takizawa et al., 2017). Inflammation has also been shown to synergise with genetic mouse models of human hematologic diseases to promote the emergence of clinically relevant features that do not manifest under standard laboratory conditions (Hormaechea-Agulla et al., 2021; Soukup et al., 2021; Walter et al., 2015).

Since mammals frequently develop a state of chronic low-grade inflammation during old age, and this coincides with suppressed HSC functional potency, it has been speculated that a causal relationship exists between these two phenomena and that inflammaging may be a key factor driving the evolution of age-associated hematologic diseases resulting from dysfunctional HSCs, including clonal hematopoiesis, myeloid leukemias and anemia (Caiado et al., 2021; King et al., 2020; Trowbridge and Starczynowski, 2021). However, the majority of these studies have been performed using young mice, and it is not known whether instances of acute inflammatory challenge in early life can result in a sustained functional impairment of HSCs that would be necessary to impact upon the biological function of the hematopoietic system in old age. Such a mechanism would help inform us how a young hematopoietic system may acquire a phenotypically aged state with accumulated exposure to different instances of inflammatory exposure, as opposed to how hematopoiesis is suppressed by chronic inflammaging once the aged state is finally reached. In this study, we perform a painstaking time-course analysis of HSC function following discrete instances of sterile or infection-associated inflammation, in order to take the important step of defining whether loss of HSC function after inflammatory challenge is reversible, long-lived, or perhaps even permanent.

Results:

Separate instances of sterile inflammation have a cumulative, irreversible negative effect on HSC function.

The toll-like receptor 3 agonist polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pI:pC) is an ideal reagent to study kinetics of HSC regeneration in vivo, since it can be used to elicit a defined short pulse of inflammatory challenge similar to that observed during a viral infection, following which recovery can be measured. The sterile inflammation that it promotes results in a temporarily discrete hematologic response consisting of transient peripheral blood (PB) cytopenias and a parallel increase in proliferation of long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), all of which return to homeostatic levels within 4 days (Figure S1A) (Essers et al., 2009; Walter et al., 2015). To assess the effects of repeated inflammatory challenge, wild-type C57BL/6J mice were subjected to a dose escalation regimen in which blocks of pI:pC treatment, and the final analysis of hematologic parameters, were separated by four-week recovery periods to ensure that observed phenotypes were not artefacts related to transient alterations in proliferation rate or cell surface marker expression (Figure S1B). One to three blocks of pI:pC treatment, corresponding to 8 to 24 individual injections spread over the course of 8 to 24 weeks, failed to provoke any major sustained changes in PB and BM cellularity or composition (Figures S1C-F). Likewise, the frequency and absolute number of phenotypic and transcriptionally-defined LT-HSCs in the BM of treated mice was comparable to phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-treated controls (CON)(Figures S1G-K). However, an in vitro assessment of LT-HSC function revealed that the clonogenic potential of LT-HSCs isolated from mice treated with three blocks of pI:pC (Tx3x) was reduced compared to those from CON mice (Figures 1A-B). There was a marked decrease in the overall proliferative potential of individual LT-HSCs from Tx3x mice, which was most profoundly exhibited in more primitive clones producing multi-potent progeny (Figures 1C, S1L). Importantly, the proliferative potential of more differentiated stem and progenitor cells was unaltered (Figure S1M). Continuous cell fate tracking experiments using video microscopy demonstrated more rapid differentiation kinetics of Tx3x LT-HSCs compared to CON LT-HSCs, as well as an accelerated exit from quiescence into first cell cycle (Figures 1D-E). Taken together, these data suggest that, while more mature hematopoietic cells are fully restored within 4 weeks of repeated pI:pC challenge, the functional capacity of LT-HSCs still appears to be compromised.

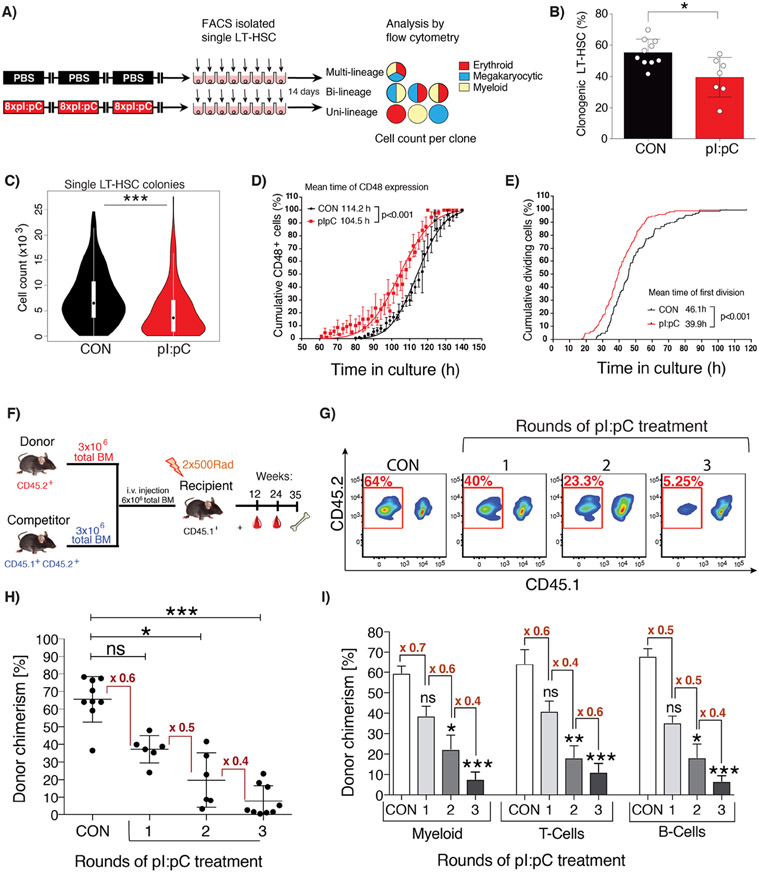

Figure 1. Repetitive exposure to inflammatory stress progressively compromises the functional potency of LT-HSCs.

(A) Schematic representation of in vitro single cell liquid culture assay using purified LT-HSCs. (B) The percentage of LT-HSC clones capable of forming colonies is shown for LT-HSC isolated from CON or Tx3X mice (plus mean±SD, n=7-10 mice). (C) Violin plots representing the total number of daughter cells generated by each LT-HSC. (D&E) In vitro time-lapse microscopy-based cell tracking, evaluating: (D) the cumulative percentage of cells expressing CD48 versus time in culture, fitted to a Gaussian distribution curve; (E) the cumulative incidence of LT-HSC having undergone first cell division per unit time in culture (mean±SD, n= 128 or 148 individual LT-HSCs for CON or pI:pC groups, respectively; n=3 independent biological repeats per group). (F-I) Competitive repopulation assays were performed as described in methods. PB was analyzed at 24 weeks post-transplantation. (F) Schematic representation of the standard competitive transplantation assay (G) Representative flow cytometry plots of total donor leukocyte chimerism in PB. PB cells derived from donor BM isolated from pI:pC-treated or CON donors are outlined in red. (H) Percentage total donor leukocyte chimerism in PB for the indicated groups. Each dot represents transplantation outcome of BM from an individual treated donor mouse (I) Percentage donor chimerism in defined compartments of PB. Myeloid=CD11b+, T-cells=CD4+/CD8+, B-cells=B220+ (plus mean±SD, n=8-9 mice per group). ns=P>0.05, *P<0.05, **P<0.01,***P<0.001.

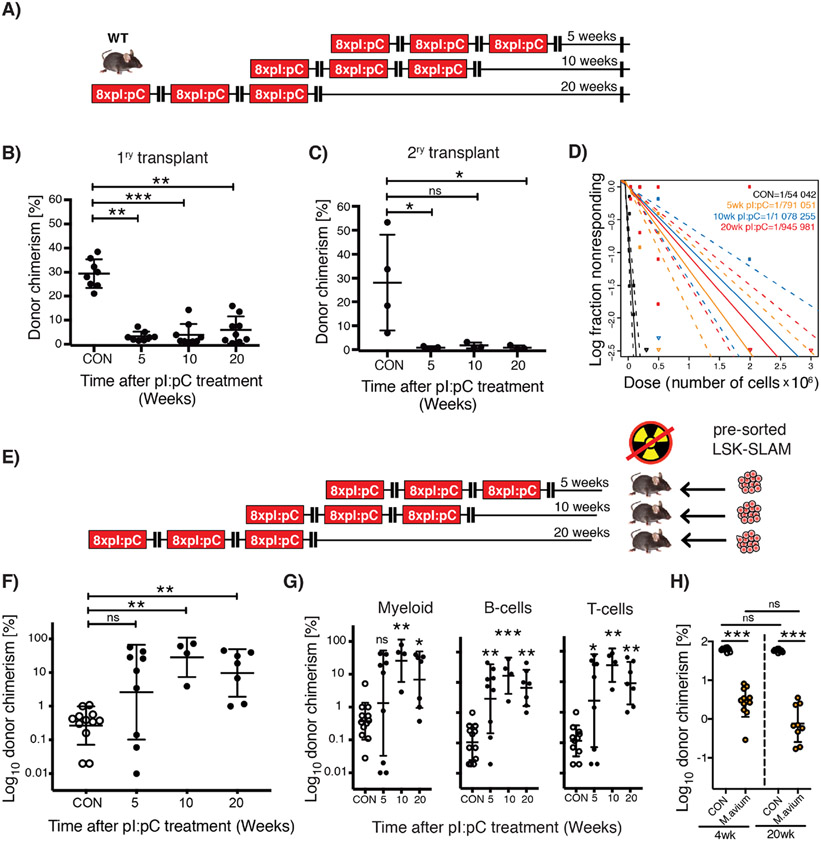

To better address the functional capacity of LT-HSCs from mice subject to repetitive induction of inflammation, competitive transplantation assays were performed using BM harvested from mice exposed to one, two or three blocks of pI:pC treatment (Figure 1F). These data demonstrated a progressive depletion of functional HSCs with increasing rounds of pI:pC challenge, correlating with an approximate two-fold reduction in the level of donor-derived hematopoiesis with each additional round of treatment (Figure 1G-I). Importantly, this cumulative depletion of functional HSCs following discrete blocks of pI:pC challenge suggests little to no regeneration of the HSC pool during the 4 week recovery periods between each block of challenge, nor in the intervening period prior to end point analysis. In order to explore this phenomenon more comprehensively, Tx3x mice were allowed to recover for 5, 10, or 20 weeks post-challenge, following which, primary and secondary transplantation assays were performed (Figures 2A, S2A-F). Surprisingly, competitive transplantation revealed that there was no significant regeneration of the reconstitution capacity of HSCs, even following an extensive recovery period corresponding to 20% of the lifespan of a laboratory mouse (Figures 2B-C). Limiting dilution transplantation assays recapitulated this important finding and demonstrated that there was no recovery in the absolute number of functional HSCs following pI:pC challenge, with Tx3x mice still demonstrating an approximate 20-fold reduction in functional HSCs up to 20 weeks post-treatment compared to CON mice (Figures 2D, S2G-H). To address whether these findings related to compromised function of native HSCs, as opposed to defects that only become manifest upon transplantation of HSCs from treated mice, reverse transplantation experiments were performed (Figure 2E). Thus, an excess of purified HSCs harvested from non-treated wild-type mice were transplanted into Tx3X recipient mice at 5, 10 or 20 weeks after treatment, in the absence of any myeloablative conditioning. In stark contrast with CON recipients, we observed sustained multi-lineage engraftment of normal HSCs into Tx3X recipients, which appeared even more robust when the transplantation was performed several months post-treatment (Figure 2F-G). This suggests that repeated inflammatory challenge resulted in a durable suppression of recipient HSCs, facilitating engraftment of donor HSCs for an unprecedented length of time after treatment. This data additionally demonstrates that the niche of Tx3X mice is qualitatively capable of functionally supporting multilineage hematopoiesis from transplanted HSCs, correlating with a lack of evidence for major permanent alterations in the composition of niche cells or spatial distribution of HSCs relative to niche landmarks following pI:pC treatment (Figures S3A-H). However, it doesn’t exclude the possibility that the niche plays a role in the original depletion of functional HSCs upon immune/inflammatory challenge (Hernandez-Malmierca et al., 2022; Meacham et al., 2022). In an attempt to demonstrate that the absence of regeneration of the HSC pool was a broadly applicable phenomenon, we utilized a previously described Mycobacterium avium infection model which drives LT-HSC proliferation in vivo via an interferon-γ-mediated mechanism (Matatall et al., 2016). Mice were subject to monthly challenge with M. avium, followed by antibiotic treatment to eliminate the active infection. As observed following pI:pC challenge, we saw absolutely no recovery in competitive repopulating activity of BMC from treated mice, regardless of whether mice were allowed to recover for 4- or 20-weeks prior to harvest (Figure 2H).

Figure 2. Lack of HSC functional recovery in vivo following inflammatory stress.

(A) Schematic representation of treatment schedule incorporating increasing duration of recovery post-challenge with pI:pC. (B&C) Serial competitive repopulation assay using BM harvested from mice at indicated time points post-treatment: (B) Percentage total donor leukocyte chimerism at 24 weeks post-transplantation in primary recipients; (C) Percentage total donor leukocyte chimerism at 24 weeks post-transplantation in secondary recipients. Each dot represents transplantation outcome of BM from an individual treated mouse or primary recipient mouse (plus mean±SD). (D) Limiting dilution transplantation assays to determine LT-HSC frequency in BM isolated from femora of individual mice. 95% confidence intervals are indicated with dashed lines (n=6-9 recipients per dilution, per donor, representing analysis of BM from 3-4 individual treated donor mice). (E) Schematic representation of reverse transplant experiment. Mice exposed to the indicated treatment regimen were injected i.v. with saturating doses of purified donor HSCs in the absence of any conditioning with irradiation. (F&G) Percentage donor contribution in PB at 24 weeks post-reverse transplantation to the following defined populations: (F) total leukocytes; (G) Myeloid (CD11b+/GR-1+), B-cells (B220+) and T-cells (CD4+/CD8+). Each dot indicates an individual treated recipient (plus mean ± SD). (H) Competitive repopulation assay using BM from mice infected three times with M. avium, treated with clarithromycin to resolve the infection, then harvested at either 4- or 20-weeks post-treatment. Percentage total donor leukocyte chimerism at 24 weeks post-transplantation is shown. Control (CON) group was also treated with clarithromycin for equivalent time period. Each circle indicates a transplantation outcome from an individual treated donor mouse. ns=P>0.05, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

We conclude from these experiments that the complete absence of HSC regeneration after inflammatory challenge supports a model where such challenges can have a cumulative effect on the functional decline of the HSC pool, even if they are separated by a time span of several months. Critically, sustained inflammatory stimulus is not required to maintain the long-term functional suppression of HSCs, distinguishing this observation from the phenomenon of chronic low-grade inflammation that is a feature of aging.

Sterile inflammation drives accelerated aging of LT-HSCs and promotes aged hematopoietic phenotypes observed in humans.

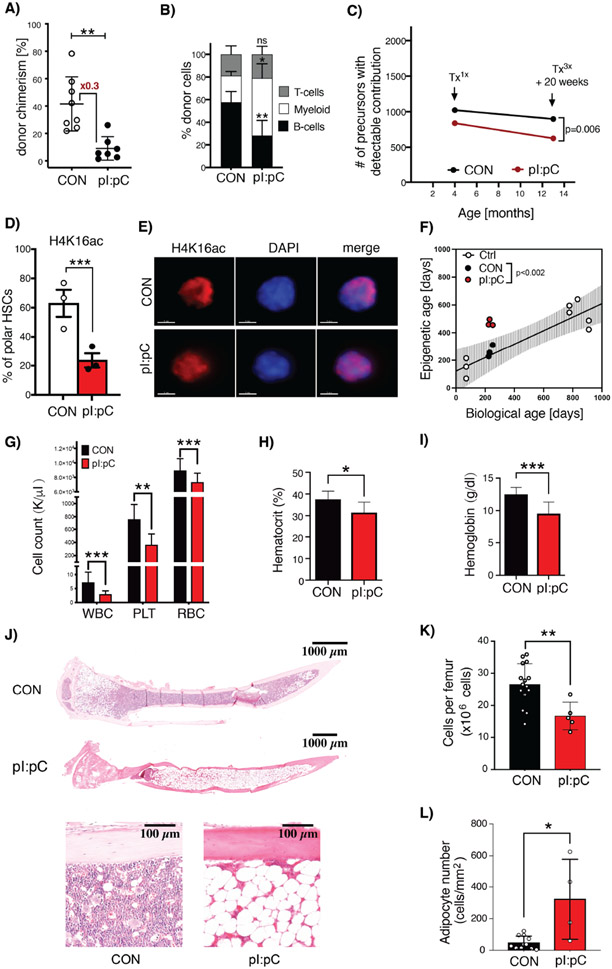

Tx3X mice were then followed for up to 12 months after challenge to evaluate any long-term effects upon hematopoiesis. Notably, after competitive transplantation, HSCs from Tx3X mice still demonstrated significantly compromised functional potency compared to those from age-matched CON mice despite the extensive one year recovery period, with a strong skewing towards myeloid biased reconstitution, which is a hallmark of murine hematopoietic aging (Figures 3A-B). Along these lines, using a genetic multicoloured trace reporter (Ganuza et al., 2019), we could also observe a reduction in LT-HSC clonal complexity in Tx3X but not CON mice, which has parallels to the phenomenon of age-related clonal hematopoiesis (ARCH) in humans (Figure 3C). In an effort to conclusively assess whether there was molecular evidence of accelerated aging of LT-HSC after sterile inflammation, we interrogated two epigenetic age-associated phenomena. Firstly, we observed a dramatic decrease in LT-HSC from Tx3X mice with a polar distribution of the H4K16ac mark, as previously demonstrated to exist in aged LT-HSCs (Mejia-Ramirez et al., 2020) (Figure 3D-E). Secondly, we performed an analysis of the DNA methylome clock in purified LT-HSCs, a methodology that can accurately predict biological age by evaluating progressive methylation programming events at specific CpG loci and which has recently been linked with the evolution of ARCH in humans (Horvath and Raj, 2018; Nachun et al., 2021). Importantly, we found that, while LT-HSCs from CON mice had a linear correlation between chronologic and biological age, those from Tx3X mice demonstrated a biological age corresponding to that of elderly mice (Figure 3F). Taken together, these data firmly place inflammation in young mice as a causal driver of the accelerated acquisition of multiple functional and molecular hallmarks of aging in LT-HSCs, as opposed to simply an effect of aging.

Figure 3. Inflammatory challenge promotes accelerated hematologic aging.

(A&B) PB flow cytometry analysis at 24 weeks post-competitive transplantation of BM cells harvested from CON or Tx3X mice at 12 months post-challenge. (A) Total donor leukocyte chimerism and (B) relative frequency of myeloid (CD11b+/Gr-1+), B- (B220+) and T-cells (CD4+/CD8+) are shown. Dots represent individual mice, mean±SD is indicated, n=7-8 mice per group. (C) The clonal complexity of LT-HSC in CON, Tx1x or Tx3X (20 weeks post-treatment) Conf-Flk-1Cre mice was calculated as previously described(Ganuza et al., 2019). n=6-10 mice per group. (D&E) Assessment of polarity of distribution of H4K16ac within the nucleus of LT-HSCs. (D) Percentage of LT-HSCs isolated from CON or Tx3X mice that had a polar distribution of H4K16ac staining. n=3 mice per group; 39 single cells for CON and 41 single cells for Tx3X mice. Each point indicates an individual mouse; data are mean±SD. (E) Representative single-cell IF images showing the distribution of H4K16ac (red) in the nuclei of LT-HSCs from Tx3X or CON mice. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue), scale bar=3μm. (F) Plot of chronological age versus biological age calculated via DNA methylome clock, for LT-HSCs isolated from: non-treated young and aged mice (white circles); Tx3X mice (red circles); and age-matched CON mice (black circles). Line represents linear regression on young and aged non-treated mice with 95% CI (shaded area). (G-L) Mice were challenged repeatedly with pI:pC or PBS in early/mid-life as illustrated in Figure S4A. At 24 months of age, the following hematologic parameters were assessed: (G) Leukocyte (WBC), platelet (PLT) and red blood cell (RBC) counts in PB; (H) PB hematocrit; (I) Hemoglobin; (J) Representative whole mount H&E sections of tibiae; (K) BM cellularity per femur; and (L) Microscopy-based enumeration of adipocyte density within medullary cavity of tibiae (n=5-15 mice per group in G-I). Circles represent individual treated aged mice (plus mean±SD). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

To ascertain whether the irreversible depletion of BM HSC reserves associated with accelerated aging eventually results in compromised hematopoiesis, eight week old mice were subjected to eight rounds of pI:pC treatment (Tx8X) and were then either analyzed at 18 months of age, or were analyzed once they reached 24 months of age (Figure S4A). As previously described for Tx3x mice, functional HSCs were depleted in the BM of Tx8X mice, as assessed by competitive transplantation, while the PB and BM parameters were not dramatically altered relative to CON mice, when analyzed 2 months after treatment (Figures S4B-F). However, at 24 months of age, Tx8X mice developed mild PB cytopenias and BM hypocellularity associated with increased BM adipocytes (Figures 3G-L), consistent with phenotypic parameters that are frequently observed in human aged non-malignant hematopoiesis, but which are not typically manifest in experimental mice housed under laboratory conditions (Biino et al., 2013; Guralnik et al., 2004; Hartsock et al., 1965; Tuljapurkar et al., 2011).

LT-HSCs fail to self-renew in vivo during and after short-term inflammatory challenge.

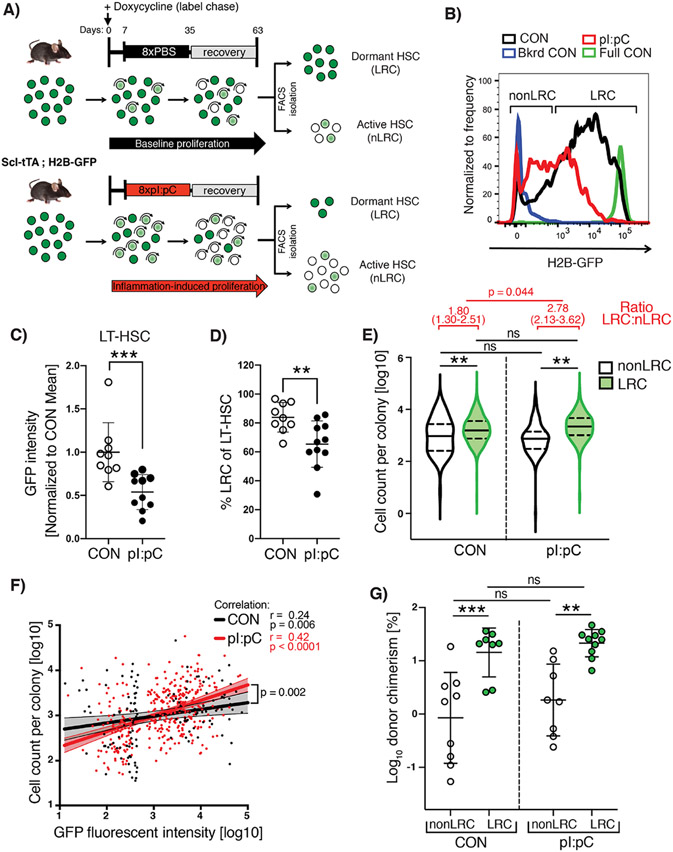

Stem cell exhaustion is a poorly defined, but frequently cited cause of tissue aging and dysfunction (Lopez-Otin et al., 2013). The concept of HSC exhaustion appears to contradict the broadly accepted view that HSCs possess extensive self-renewal capacity, and the co-existence of these two models appears to rely on the assumption that excessive HSC proliferation is necessary to eventually deplete them of their self-renewal activity. In an attempt to directly interrogate this assumption, we re-purposed a genetic label retention system in order to capture inflammation-induced HSC division events in vivo and determine the degree to which functional potency was preserved via self-renewal divisions. Thus, the previously described Scl-tTA;H2BGFP mouse model (Wilson et al., 2008) was subject to a single treatment block (Tx1x) of either pI:pC or PBS, during the doxycycline-induced chase period (Figure 4A). HSCs which respond to the stimulus dilute the H2B-GFP label with each round of cell division (non-label retaining cells; nLRCs), while label-retaining cells (LRCs) remain quiescent throughout the challenge period. Using flow cytometry we could show that a single round of pI:pC treatment increased the average proliferation rate of LT-HSCs in vivo, resulting in a reduced level of H2B-GFP labelling per cell and a reduced frequency of LRCs compared to PBS-treated controls (Figure 4B-D). However, some LRC still persisted during challenge, meaning that this single round of treatment was not so severe that it engaged the entire LT-HSC compartment in extensive proliferation (Figure 4D). To determine whether in vivo proliferation events represented self-renewal divisions, we prospectively isolated individual LRC and nLRC and assessed their functional potency using the previously described in vitro growth assay (Figure 1A). While nLRC demonstrated a reduction in proliferative potential that decreased in line with their proliferative history, as determined by index-sort analysis of H2B-GFP label dilution, LRC were able to maintain their functional potency in the face of systemic inflammatory challenge (Figure 4E-F). The preservation of LT-HSC functionality within the LRC fraction of TX1X mice was confirmed when sorted cells were subject to competitive repopulation assay (Figure 4G). These data demonstrate that loss of LT-HSC function is linked to increased proliferation history, as opposed to a generic systemic inhibitory effect of inflammation. Importantly, it also reveals that the overall decrease in potency of LT-HSCs within the BM is predominantly mediated by a decreased absolute number of LRCs within this compartment. Intriguingly, we could detect no profound sustained changes in gene expression across the majority of LT-HSCs (Figure S5A). However, we were able to identify a highly-penetrant alteration in DNA methylome programming corresponding to hypomethylation of promoters of interferon/inflammatory response genes, which formally demonstrates a lack of LT-HSC self-renewal at the epigenetic level (Figure S5B-D). Taken together, we conclude that LT-HSC self-renewal divisions appear to be absent during low to moderate inflammatory challenge and the ensuing recovery period, resulting in daughter HSCs possessing reduced functional potency compared to the parental HSCs. This lack of self-renewal would explain why separate instances of inflammation can have an irreversible and therefore cumulative effect on overall LT-HSC function throughout the lifetime of the mouse, although the exact nature of this functional decline is unclear and is likely to be multi-factorial.

Figure 4. Dormant HSCs are protected from inflammation-associated functional decline while proliferating cells fail to self-renew.

(A) Schematic representation of combined label retention and treatment schedule. Scl-tTA;H2B-GFP mice were treated with pI:pC or PBS (CON) as indicated. Label chase was induced by sustained administration of doxycycline starting 7 days before pI:pC/PBS treatment. Flow cytometry analysis/sorting was performed on BM at 8 weeks after initiation of pI:pC/PBS treatment. (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms of GFP fluorescence in LT-HSCs from PBS and pI:pC treated mice. Background fluorescence (Bkrd CON) and fully labeled (Full CON) controls are indicated (C) Mean fluorescent intensity of GFP in LT-HSCs and (D) the proportion of LRCs within the LT-HSC population in CON and pI:pC treated mice. Each dot represents a single mouse (plus mean±SD). (E) Violin plots showing the cell number of progeny generated per individual LRC or nonLRC following 14 days in-vitro culture (n=4-5 mice per group, n=280, 364, 293 or 260 analyzed clones for nonLRC CON, LRC CON, nonLRC pI:pC and LRC pI:pC, respectively). Solid lines represent median, dashed lines interquartile range. Analysis of ratio between LRC and nLRC groups is shown in red. (F) Correlation analysis between GFP intensity and cell number of progeny per individual LT-HSCs following 14 days in-vitro culture (n=3 mice per group, n=132 and n=363 analyzed LT-HSCs per CON and pI:pC group respectively). Dots represent individual LT-HSCs, lines are simple linear regression with 95% CI. (G) Percentage total donor PB leukocyte chimerism following competitive transplantation of LRC or nonLRC from CON or pI:pC-treated mice at 12 weeks post-transplantation. n=8-10 donor mice per condition. ns=P>0.05, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

Discussion:

In this study, we perform a painstaking time course analysis spanning periods of up to one year after cessation of inflammatory challenge, in order to unequivocally demonstrate that there is no subsequent regeneration of the HSC pool and that activation of HSCs out of dormancy is not a fully reversible process, as previously thought (Wilson et al., 2008). While our data does not exclude the possibility that HSCs can generate daughter cells that are also broadly defined as HSCs following inflammation, it does indicate that daughter HSCs rarely or never inherit the full functional potency of their direct predecessors under these conditions. This is in line with the overall conclusions of previous work using more severe stress agonists, including chemotherapy and transplantation following myeloablative conditioning, both of which promote extensive HSC proliferation (Beerman et al., 2013; Hinge et al., 2020). In contrast to previous studies, and of importance for our further understanding of the concept of HSC exhaustion, we demonstrate that a sustained or high magnitude pro-proliferative stimulus is not required for the functional attrition of HSC. Rather, our data indicates that under conditions of low grade inflammation, functional attrition can only be observed in the fraction of HSCs that mount a proliferative response to the stimulus, while dormant HSCs are protected from systemic inflammation. Clearly, over the course of an entire lifetime, an organism will be exposed to many rounds of inflammatory stress. In this context, our data supports a clonal succession/generational age model (Kay, 1965; Rosendaal et al., 1976) in which individual HSCs will be sequentially activated to proliferate with each exposure to inflammation, resulting in functional “exhaustion” for these clones. This may explain why the phenomenon of HSC exhaustion remains somewhat nebulous on a mechanistic level, since our data would indicate that this is something that occurs on an intermittent basis for a sub-set of HSCs, as opposed to an event that can be observed to happen in all HSCs at a defined moment in time.

Inflammation is currently under intense scrutiny as a possible key mediator of the evolution of age-associated hematologic pathologies related to dysfunctional HSC biology, including anemia, immune-suppression, ARCH and leukemogenesis (Hormaechea-Agulla et al., 2020; Trowbridge and Starczynowski, 2021). This line of investigation is largely driven by the fact that a state of chronic low-grade inflammation, known as inflammaging, exists in the elderly and is therefore a likely mediator of a number of age-associated phenotypes (Fulop et al., 2018). However, we provide extensive molecular and functional data to demonstrate that inflammatory exposure can provoke accelerated HSC aging in younger mice, strongly suggesting that inflammation in early life is of relevance to the much later development of an aged phenotype. This would be in line with our observation that mice exposed to inflammatory stimuli in early to middle age, eventually develop PB cytopenias, BM hypocellularity and accumulation of BM adipocytes, that together comprise typical features of aged human hematopoiesis, but which are not normally observed in experimental mice housed under laboratory conditions (Biino et al., 2013; Guralnik et al., 2004; Hartsock et al., 1965; Tuljapurkar et al., 2011).

Inflammatory signaling cascades are also a frequently proposed therapeutic target to prevent or revert age-associated pathologies. Our work demonstrates that inflammatory stimuli can provoke a long-lasting inhibitory effect on hematopoiesis that extends far beyond the duration of the original inflammatory event, via the progressive and irreversible attrition of the functional HSC pool. We would therefore argue that prophylactic anti-inflammatory interventions may effectively delay or prevent the evolution of age-associated pathologies, but that such treatments may hold limited capacity to rejuvenate an already aged hematopoietic system. Nonetheless, one critical question that remains to be answered is whether a therapeutic window exists to limit inflammation-associated damage to HSCs, while still permitting what one might assume is a critical emergency response in terms of regenerating mature blood cells after challenge.

Limitations of the Study.

Although we characterize a range of persistant cellular and molecular changes elicited upon HSCs by inflammatory challenge, we provide no precise molecular mechanism to explain the loss of function we observe. We hypothesize that any such mechanism is likely complex and multi-factorial, as is the case for several age-associated phenomena.

We demonstrate that irreversible loss of potency in HSCs is a common outcome following the two inflammatory treatment regimens described in the manuscript. However, the impact of any given inflammatory stimulus on HSC function will likely vary dependent on a number of factors, including the magnitude, duration and type of inflammatory response they provoke or, in the case of infectious agents, their mode of transmission and virulence.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Michael Milsom (michael.milsom@dkfz.de).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

Single-cell RNA-seq and tagmentation-based whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. Microscopy data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. All data analysis in this manuscript was performed using pre-existing code. Appropriate references have been included to direct the reader to the original description of such code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| c-kit (CD117) APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-1171; clone 2B8; RRID:AB_469429 |

| Sca1 APC-Cy7/FITC | BD Bioscience | Cat# 560654; clone D7; RRID:AB_1727552/ Cat# 11-5981-82; clone D7; RRID:AB_465333 |

| CD150 Pe-Cy5 | Biolegend | Cat# 115912; clone TC15-12F12.2; RRID:AB_493598 |

| CD48 PacBlue/PE | Biolegend | Cat# 103427; clone HM48-1; AB_10895922/ Cat# 12-0481; clone HM48-1; RRID:AB_465694 |

| CD34 FITC | eBioscience | Cat# 2159106; clone RAM34 |

| CD41 PE/PacBlue | Biolegend | Cat# 12-0411-82 clone eBioMWReg30(MWRe g30); RRID:AB_763485/ Cat# 48-0411-80; clone eBioMWReg3; RRID:AB_1582239 |

| Ki67 FITC | eBioscience | Cat# 556026; clone B56; RRID:AB_396302 |

| CD5 Pe-Cy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0051-81 clone 53-73 RRID:AB_657755 |

| CD8a Pe-Cy7/PE | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0081; clone 53-6.7; RRID:AB_469584/ Cat# 12-0081; clone 53-6.7; RRID:AB_465530 |

| CD11b Pe-Cy7/APC/APC-Cy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0112; clone M1/70; RRID:AB_469588/ Cat# 17-0112; clone M1/70; /Cat# 47-0112; clone M1/70; RRID:AB_1603193 |

| B220 Pe-Cy7/PE/APC-Cy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0452-82; clone Ra3-6B2; RRID:AB_469627/ Cat# 12-0452; clone Ra3-6B2; RRID:AB_465671/ Cat# 47-0452; clone Ra3-6B2; RRID:AB_1518810 |

| Gr1 Pe-Cy7/APC-Cy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-5931; clone RB6-8C5; RRID:AB_469663/ Cat# 47-5931; clone RB6-8C5; RRID:AB_1518804 |

| Ter119 Pe-Cy7/FITC | eBioscience | Cat#25-5921; clone TER119; RRID:AB_469661/ Cat# 11-5921; clone TER119; RRID:AB_465311 |

| Streptavidin Pe-Cy7/PE | eBioscience | Cat# 405206; clone S3E11/Cat# 12-4317-87; clone S3E11 |

| CD16/32 eFluor450 | eBioscience | Cat# 57-0161; clone 93 |

| CD127 PE | eBioscience | Cat# 12-1273-83; clone eBioSB/199 (SB/1999); RRID:AB_953564 |

| CD4 PE | eBioscience | Cat# 12-0041; clone GK1.5; RRID:AB_465506 |

| CD71 PE | eBioscience | Cat# 12-0711-83; clone R17217(R17 217.1.4); RRID:AB_465741 |

| CD42d APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-0421-82; clone 1C2; RRID:AB_1724071 |

| CD45.1 PacBlue | eBioscience (BD) | Cat# 110722; clone A20; RRID:AB_492866/ |

| CD45.2 FITC/AF700 | eBioscience | Cat# 11-0454; clone 104; RRID:AB_465061/ Cat# 560693; clone 104; RRID:AB_1727491 |

| Alexa Fluor 647-anti-CD144 FITC | Biolegend | Cat# 138005; clone BV13; RRID:AB_10568319 |

| Alexa Fluor 647-anti-CD31 BV 421 | Biolegend (BD) | Cat# 562939; clone MEC13.3; RRID:AB_2665476 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Mycobacterium avium | Matatall et al., 2016 | SmT 2151 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pI:pC) | InvivoGen | Tlrl-pic-5 |

| PBS | Sigma Aldrich | D8537-6X500ML |

| clarithromycin | Sigma | 81103-11-9 |

| ACK lysing buffer | Lonza | 10-548E |

| BD Cytofix/Cytoperm | BD Bioscience | 561651 |

| PermWash | (BD Bioscience) | BD 554723 |

| Hoechst33342 | Invitrogen | H3570 |

| Histopaque 1083 | Invitrogen | SD10831 A |

| Hematoxylin/Eosin | Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH/Sigma | 51275-1L/ HT110232 |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Sigma-Aldrich | ED2SS-1KG |

| Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) | Life Technologies | 21980065 |

| 7-AAD, | Invitrogen/ Life Technologies | A1310 |

| StemSpan SFEM) | StemCell | 09650 |

| Flt3-Ligand | PeproTech | 300-19-100 |

| TPO | PeproTech | 315-14 |

| IL-3 | PeproTech | 213-13-50 |

| IL-11 | PeproTech | 220-11-100 |

| Epo | Janssen | 06301240 |

| IL-7 | PeproTech | 217-17-10 |

| SCF | PeproTech | 250-03-100 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Biotin Binder Dynabeads | Life Technologies | 11415D |

| QIAamp DNA Micro Kit | Qiagen | 56304 |

| SMARTer Ultra Low RNA kit | Clontech | 634888 |

| ERCC RNA spike-ins | ThermoFisher Scientific | 4456740 |

| Illumina Nextera XT kit | Illumina | 4456740 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Whole genome bisulfite sequencing data for LT-HSC isolated from aged and pI:pC/CON treated mice | This manuscript | NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE200337 |

| Whole genome bisulfite sequencing data for LT-HSC isolated from young mice | This manuscript | NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE52709 |

| scRNA-seq data | This manuscript | NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)GSE200979 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6 | Harlan Laboratories, Charles River Laboratories, or Janvier Laboratories | |

| B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ | Harlan Laboratories, Charles River Laboratories, or Janvier Laboratories | |

| ROSA26+/ConfettiFlk-1+/Cre (Conf-Flk-1Cre) | Ganuza et al., 2019 | |

| Scl-tTA;H2BGFP | Wilson et al., 2008 | |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| web-based ELDA software | http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/ | |

| FlowJo software | Tree Star | |

| Slide Book software | Intelligent Imaging Innovations | |

| ZEN 2011 (blue edition) 1.0 | Zeiss | |

| Roddy Workflow | https://github.com/DKFZ-ODCF/AlignmentAndQCWorkflows | |

| ’BWA-MEM’ | https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 | |

| SAMtools flagstat | Li et al., 2009 | |

| ‘bistro’ methylation caller (version 0.2.0) | https://github.com/stephenkraemer/bistro | |

| Zeiss AxioVision 4.8 software | Zeiss | |

| Fiji (ImageJ) | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ | |

| STAR (Spliced Transcript Alignment to a Reference) | Dobin et al., 2013; | version 2.5 |

| Destiny R package | Angerer et al., 2016 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/destiny.html |

| GraphPad Prism software | GraphPad Software, Inc., SanDiego, CA | http.//www.graphpad.com |

| R software | https://www.r-project.org/ | |

| Other | ||

| Hemavet 950 FS veterinary blood cell counting machine | Drew Scientific | |

| LSRFortessa cytometer | Becton Dickinson | |

| LSRII | Becton Dickinson | |

| FacsAria I, II or III flow cytometer) | BD Bioscience | |

| ZEISS AXIO examiner D1 microscope | ZEISS | |

| confocal scanner unit, | Yokogawa | CSUX1CU |

| Axio Plan Zeiss Microscope | Zeiss | version 4.1.0 |

| Axio Cam ICc3 | Zeiss | |

| Tissue-TeK-VIP Sakura tissue processor | ||

| HistoStar embedding workstation | Thermo Scientific | |

| Microtome | Thermo Scientific | Microm HM 355S |

| HiSeq 2000 platform | Illumina | |

| CellObserver system | Zeiss | |

| Fluidigm C1 system | Fluidigm | |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

Wild-type mice (C57BL/6 or B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories, Charles River Laboratories, or Janvier Laboratories. Unless otherwise indicated, mice were 8 to 16 weeks old when experiments were initiated. H2B-GFP and ScltTA mice have been previously described (Bockamp et al., 2006; Tumbar et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2008). ROSA26+/ConfettiFlk-1+/Cre (Conf-Flk-1Cre) mice were used to estimate HSC clonality as previously described (Ganuza et al., 2019).

METHOD DETAILS

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved either by the local Animal Care and Use Committees of the Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe für Tierschutz und Arzneimittelüberwachung, the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, or the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in individually ventilated cages at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ, Heidelberg), St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, or Baylor College of Medicine. H2B-GFP and ScltTA mice on a C57BL/6 background were crossed in order to perform a label retaining cell (LRC) assay. For the LRC assays, doxycyline treatment was performed by supplementing the drinking water of experimental mice with 2 mg/ml doxycyline citrate (Sigma), sweetened with 20 mg/ml sucrose. Doxycycline-supplemented drinking water was sustained for the duration of the label chase period.

Treatment with pI:pC

To mimic a repetitive sterile inflammatory response in vivo, mice were serially injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 5 mg/kg high molecular weight polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pI:pC, InvivoGen), which had been reconstituted in sterile physiologic saline precisely as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Control mice were injected with the same volume of PBS (Sigma Aldrich). Scheduling of injections was as detailed in the main text.

Infection with Mycobacterium avium

Mice were infected once per month for 3 months with 2 x 106 colony-forming units (CFU) Mycobacterium avium (SmT 2151) by intravenous injection as previously described (Feng et al., 2008). Bacterial CFU were quantified by growth on Middlebrook agar or by qPCR (Park et al., 2000) . Chronically infected mice were treated with clarithromycin (Sigma, 81103-11-9) by oral gavage as described (Andrejak et al., 2015). The mice were administered 100mg/kg of antibiotic once daily, 5 days per week, for either 1 month or 4 months.

Bleeding and bone marrow isolation

Peripheral blood (PB) was collected by puncturing the craniofacial capillary bed of the mice and up to 100 μl of PB was collected into EDTA-coated tubes. PB counts were evaluated using a Hemavet 950 FS veterinary blood cell counting machine (Drew Scientific). For the purification of murine bone marrow (BM) cells, hind legs (femora, tibia and iliac crests) and vertebrae were dissected by removing adherent soft tissue and the spinal cord using a scalpel. Bones were either crushed or flushed, and the resulting cell suspension was filtered through 40 μm cell strainers (Greiner Bio-One) and re-suspended in ice cold 2 % (v/v) FCS/PBS (PAA Laboratories/Sigma Aldrich) following centrifugation. When BM cells were pooled from multiple mice, bones were gently crushed in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM, Life Technologies). Bones from individual mice were harvested by flushing the cells out of two femurs into 2 ml ice cold 2 % (v/v) FCS/PBS or PBS using a 1 ml syringe fitted with a 23 gauge needle.

Competitive repopulation transplantation assays

CD45.2 or CD45.1 C57BL/6 recipient mice were subject to total body irradiation (2 x 5 Gy TBI, Bestrahlungsgerät/Buchler GmbH, caesium source) 2 to 16 hours prior to BM transplantation. Recipients were co-injected intravenously (i.v.) with a mixture of 3 x 106 WT CD45.1/CD45.2 whole BM competitor cells and 3 x 106 WT CD45.1 or CD45.2 whole BM test donor cells (Fig. 1F). BM from each individual test mouse (pI:pC or PBS) were separately transplanted into individual recipient mice. However, in order to facilitate high reproducibly, the co-injected competitor BM cells came from a common pool of cells, isolated from at least two donors. The same pool of competitor BM was used for all transplanted mice within each experimental repeat. To evaluate the repopulation potential of the test BM populations, PB and BM of recipient mice were analyzed by flow cytometry at three, six and eight months post-transplantation. PB and BM were stained with monoclonal antibodies against CD45.1 and CD45.2, in order to discriminate between reconstitution from test donor cells; competitor donor cells; and endogenous recipient cells. PB and BM were additionally stained with antibodies directed against B220, CD4, CD8a, CD11b; CD5, Gr-1, Ter-119, c-Kit, Sca-1, CD150 and CD48, in order to evaluate donor reconstitution within defined mature and immature cell populations. An aliquot of the input cell mix was separately stained and evaluated by flow cytometry to validate the correct ratio of cells was injected into recipient mice. For competitive transplantation of LRCs, 400 purified LRCs were co-injected with 4x105 CD45.1/CD45.2 supporting cells. For competitive transplantation of BMCs from mice following M. avium challenge experiments, 2 x 106 whole BMCs were co-injected with 2 x 106 CD45.1 BM competitor cells and recipient mice were conditioned with 10.5 Gy split dose TBI.

Limiting dilution transplantation assays

Total BM cells from pI:pC or PBS treated CD45.1 C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. at the indicated cell doses into cohorts of lethally irradiated CD45.2 recipient mice (2 x 5 Gy TBI), together with a fixed rescue dose of 2 x 105 CD45.1/CD45.2 BM cells. The BM of each test mouse was transplanted into 24 individual recipient mice. Recipients of BM from pI:pC-treated mice were injected with either 3 x 106 (6 recipients), 2 x 106 (60 recipients), 5 x 105 (60 recipients), 2 x 105 (60 recipients) or 5 x 104 BM cells (60 recipients), while recipients of PBS-treated BM received either 3 x 105 (18 recipients), 1 x 105 (25 recipients) or 3 x 104 BM cells (25 recipients). At least three different donor mice from each experimental group were individually assessed using this methodology. Engraftment was assessed by flow cytometry analysis of PB at six months post-transplantation. Mice that demonstrated ≥ 1% donor-derived contribution to both myeloid (Gr-1+ and/or CD11b+) and lymphoid (B220+ and/or CD4+ and/or CD8+) lineages in the PB were scored as positive (responding) for engraftment. To estimate the frequency of repopulating HSCs in the BM, a limiting dilution calculation was performed using the web-based ELDA software provided at http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/ (Hu and Smyth, 2009), using the number of responding mice at each cell dose as input data.

Reverse transplantation experiments into non-conditioned mice

Recipient CD45.1 mice were treated with three rounds of pi:pC or PBS, as illustrated in Fig. 2e. At 5, 10 or 20 weeks after treatment, mice were injected i.v. with saturating doses of (1.5 - 3 x 103) FACS-purified Lineage−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, CD150+ BM cells isolated from a CD45.2 donor. Importantly, the recipients were not subject to any additional myelosuppressive conditioning, such as total body irradiation or chemotherapy. The level of donor chimerism in defined cell populations of the PB and BM was assessed at six and eight months post-transplantation, respectively.

Flow Cytometry Analysis and Sorting

Fluorescent staining of PB and BM

PB and BM were stained with monoclonal antibodies directed against specific cell surface epitopes as detailed in Supplementary Information. All antibodies had previously been titrated and were used at a concentration where the mean fluorescent intensity plateaus. Cells were incubated with the antibody mix in 2 % v/v FCS/PBS for 30 min. at 4 °C, washed with 2 % FCS/PBS and then re-suspended in 2 % FCS/PBS containing 7-amino actinomycin (7-AAD, Invitrogen) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. For PB samples, an additional erythrocyte lysis step with 1 ml ACK lysing buffer (Lonza) for 10 min. at room temperature was carried out after the staining.

Flow cytometry analysis

After surface staining, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using either an LSRII or an LSRFortessa cytometer (Becton Dickinson) equipped with 350 nm, 405 nm, 488 nm, 561 nm and 641 nm excitation lasers. Prior to the analysis of cells, compensation was manually adjusted using OneComp eBeads (eBioscience) stained with single antibodies. Analysis of flow cytometric data was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). If not indicated otherwise, populations were gated according to the markers listed in Supplementary Information.

Cell cycle analysis

BM cells were stained with the LT-HSC antibody panel (Supplementary Information). After surface staining, cells were lysed using ACK lysing buffer, washed with PBS and fixed with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Bioscience) for 20 min. at 4 °C. Then, cells were washed twice with PermWash (BD Bioscience); re-suspended in 100 μl PermWash, containing mouse anti-human Ki-67 (Supplementary Information) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Shortly before flow cytometry analysis, the cells were incubated with Hoechst33342 in a 1/400 dilution for 10 min. at 4 °C.

Isolation of murine LSK/LT-HSC cells via FACS

To purify low-density mononuclear cells (LDMNCs) from BM cells, three rounds of density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque 1083 (Sigma-Aldrich) were performed at room temperature. An equal volume of BM cell suspension (2-10x107 cells/ml) was carefully layered on top of an equal volume of the Histopaque 1083 in a 15 ml falcon tube (Greiner; Sarstedt). After centrifugation at room temperature at 300 g for 20 min. with the brake switched off, the LDMNC fraction was collected without disturbing the pellet. The pellet was re-suspended and re-applied to Histopaque 1083 for the second round of density gradient centrifugation. In total, three rounds of centrifugation were performed. The fractions containing the LDMNCs were pooled and washed with ice-cold PBS. For lineage depletion, the LDMNC fraction was incubated with a panel of rat anti-mouse biotin-conjugated lineage markers (4.2 μg/ml CD5, 4.2 μg/ml CD8a, 2.4 μg/ml CD11b, 2.8 μg/ml B220, 2.4 μg/ml Gr-1, 2.6 μg/ml Ter-119) for 45 min. at 4 °C. After washing with ice-cold PBS, the labeled LDMNCs were incubated with Biotin Binder Dynabeads at a ratio of 4 beads per input cell (Life Technologies) and the lineage-positive cells were depleted using a magnetic particle concentrator according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dynal MPC-6, Invitrogen). To isolate the LSK/LT-HSC fraction by FACS, the resulting lineage-depleted cells were subsequently stained with a panel of antibodies (c-Kit, Sca-1, CD150, CD48, CD34), as indicated in Supplementary Information. In order to maximize the yield of LRC and nonLRC LT-HSCs from ScltTA;H2BGFP mice, density gradient centrifugation was omitted and lineage depletion was performed directly after BM isolation. LRC and nonLRC LT-HSC from ScltTA;H2B-GFP on doxycycline treatment were defined as follows. Maximum GFP intensity was determined by flow cytometry of BM isolated from a control ScltTA;H2B-GFP mouse not exposed to doxycycline treatment (Full CON). The non-specific background GFP signal (Bkrd CON) was defined in LT-HSCs from H2B-GFP mice. LT-HSCs showing GFP intensity above the Bkrd CON were defined as LRCs, where LT-HSC with an overlapping GFP intensity to the Bkrd CON were defined as nonLRC, as shown in Fig. 5b. Sorting experiments were performed using a BD FacsAria I, II or III flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) at the DKFZ Flow Cytometry Service Unit, using a 100 μm nozzle and a maximum sort rate of 3 thousand cells per second. Single cell sorts directly into 96 multi-well plates were performed using the single cell precision mode, where the drop trajectory was adjusted for a 96-well plate before each sort.

Microscopy analysis

Immunofluorescence Imaging of BM niche components

Whole mount staining of HSCs in sternum bone marrow was performed as previously described (Kunisaki et al., 2013). Briefly, Alexa Fluor 647-anti-CD144 (BV13) and Alexa Fluor 647-anti-CD31 (MEC13.3) (from Biolegend) were injected i.v. 10 minutes before euthanizing mice, in order to stain BM endothelial cells in vivo. Sternal bones were collected and transected with a surgical blade into 2-3 fragments. The fragments were bisected sagitally for the BM cavity to be exposed, and then fixed with 4 % PFA for 30 min. After rinsing with PBS, bone pieces were blocked/permeabilized in PBS containing 20 % (v/v) normal goat serum and 0.5 % (v/v) TritonX-100. Primary antibodies were incubated for approximately 36 hours at room temperature. After rinsing the tissue with PBS, the tissues were incubated with secondary antibodies for 2h. The primary antibodies used were biotin-anti-Lineage (TER119, RB6-8C5, RA3-6B2, M1/70, 145-2C11) (from BD Biosciences); biotin-anti-CD48 (HM48-1), biotin-anti-CD41 (MWReg30) (from eBioscience); and Alexa Fluor 647-anti-CD144 (BV13), PE-anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2) (from Biolegend). The secondary antibody used was Streptavidin eFluor 450 (eBioscience). Images were acquired using ZEISS AXIO examiner D1 microscope (ZEISS) with a confocal scanner unit, CSUX1CU (Yokogawa), and reconstructed in three dimensions with Slide Book software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used for comparisons of distribution patterns. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software.

LT-HSC epigenetic polarity

Purified LT-HSCs were stained with anti-H4K16ac and anti-tubulin antibodies, and subsequently scored for polarity as previously reported in (Sacma et al., 2019).

Histology, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Tibiae were fixed in 10 % formalin in PBS (v/v) for not longer than one week and decalcified for five days in 0.5 M EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) buffer (pH 7.2). Bones were dehydrated in the Tissue-TeK-VIP Sakura tissue processor overnight and subsequently paraffin embedded using the HistoStar embedding workstation (Thermo Scientific). Embedded bones were cut with a Microtome (Microm HM 355S, Thermo Scientific) and stained with Hematoxylin/Eosin (H&E). In brief, bone sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated: 3 times in xylol for 5 minutes, 2 times in 100 % ethanol, 2 times in 96 % ethanol, 1 time in 70 % ethanol and lastly transferred to VE water. Slides were then stained in Mayer’s haematoxylin for 5 minutes and then rinsed under running tap water for 5 minutes. Subsequently, they were dipped into acid EtOH (0,25 % (v/v) HCl in 70 % (v/v) EtOH) and washed until the sections were stained blue. They were counterstained with eosin for 1 minute, dipped into 95 % EtOH and 100 % EtOH and put into xylene for 15 minutes. The sections were then embedded in mounting media and dried overnight. Imaging was performed with a Zeiss Axioplan widefield microscope.

Adipocyte quantification in H&E sections

Adipocytes were counted from H&E stained tibia sections. The images were taken with an Axio Plan Zeiss Microscope equipped with Axio Cam ICc3 Zeiss (2.5x magnification) and processed with the ZEN program 2011. Adipocyte quantification was performed in Fiji (ImageJ), where individual bone marrow adipocytes, as defined by the following parameters: size (40-2000 pixel) and shape (circularity 0.4-1.00), were counted in a predefined surface area.

In vitro single cell growth assays

Single cell LT-HSC clonogenic assay

LT-HSCs were directly flow sorted as individual cells per well into retronectin pre-coated ultra-low attachment 96-well plates (Sigma-Aldrich) in serum-free medium (StemSpan SFEM) containing 1 % (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin, 1 % (v/v) L-glutamine, and recombinant murine cytokines that facilitate HSC growth and in-vitro differentiation into erythroid, myeloid and megakaryocytic lineages (10 ng/ml Flt3-Ligand, 50 ng/ml SCF, 10 ng/ml TPO, 5 ng/ml IL-3, 10 ng/ml IL-11, 0.3 IU/ml Epo, 20 ng/ml IL-7, all from PeproTech). During the clonogenic expansion, the single LT-HSCs were cultured under hypoxic conditions (5 % O2), 37 °C, 5 % CO2 for 12-14 days. The differentiation potential (myeloid, erythroid, megakaryocytic) and proliferative capacity (relative number of cells per colony) for each LT-HSC colony was enumerated by flow cytometry, essentially as previously described (Haas et al., 2015). Briefly, cells were directly stained with antibodies in the well and the entire content of the well was run through the flow cytometer. The percentage of cells contributing to the myeloid, erythroid or megakaryocytic lineages within each LT-HSC colony was determined by the expression of lineage specific markers (Gr-1/CD11b, Ter-119, CD71, CD41, CD42d).

Classification of the differentiation potential of single cell derived LT-HSC clones

LT-HSCs were classified into 7 subgroups depending on whether they had the potential to differentiate into a single cell type (unipotent cells: myeloid, erythroid or megakaryocytic), into two cell types (bipotent cells: myeloid-erythroid, myeloid-megakaryocytic, megakaryocytic-erythroid) or into all three (multipotent cells). Cells were ascribed to these groups as follows. In order to account for different base frequencies of the three descendent cell types all observed cell numbers were first normalized by the maximum number of the respective cell type over all observed cells. Next, proportions of the three normalized cell counts were calculated for each colony. In theory, each unipotent LT-HSC should produce 100 % of the specified descendent cells, bipotent LT-HSC should ideally produce close to 50 % each of the normalized numbers of descendants and multipotent cells should produce 33.3 % each. Thus, we plotted these theoretical subgroup means as well as the actual cells in a graph illustrating the descendent proportions. As the proportions add up to 100 %, a two-dimensional plot of any two of the proportions is sufficient for this analysis. Each of the actual cells was then classified into the subgroup it was closest to based on Euclidian distance. For all data sets, each of the cells could thus be classified into one subgroup and the proportion of the 7 subgroups could be determined. Differences in the distribution of these proportions where then tested for statistical significance using a Chi-Square test, using a significance level of alpha=5 %. All calculations were performed using R, Version 3.2.0.

DNA methylome clock analysis

Tagmentation-based whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (TWGBS)

Methylome analysis was performed on purified LT-HSCs isolated from individual untreated, PBS or pI:pC treated C57BL/6 mice. Genomic DNA (10-30 ng) from snap-frozen cell pellets was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen) and used as input to generate sequencing libraries by tagmentation-based whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (TWGBS) as described previously (Wang et al., 2013). To reduce PCR duplicates, two to four sequencing libraries were prepared per replicate. TWGBS libraries were subjected to 125 bp paired-end sequencing on a HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina). Sequencing was performed by the Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility at the German Cancer Research Center.

TWGBS sequence alignment and methylation calling

Read alignment was performed by the Omics IT and Data Management Core Facility (ODCF) at the German Cancer Research Center using an updated version of the pipeline published by Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2013), which was implemented as a Roddy Workflow (https://github.com/DKFZ-ODCF/AlignmentAndQCWorkflows) in the automated ’One Touch Pipeline’ (OTP) (Reisinger et al., 2017). Briefly, adaptor sequences of raw reads were trimmed using ’Trimmomatic’ (Bolger et al., 2014). Sequencing reads were then in silico bisulfite-converted (C>T for the first read in the pair, G>A for the second). The software package ’BWA-MEM’ (https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997) was used with default parameters to align the converted reads to the in silico bisulfite-converted reference mm10 genome extended with the PhiX and lambda phage sequences. After alignment, reads were converted back to their original state. PCR duplicate removal was performed per library using ‘Picard MarkDuplicates’ before merging reads from all libraries per replicate. The alignment quality was validated by computing the mapping rates using SAMtools flagstat (Li et al., 2009), insert size distributions, and genome coverage statistics. Methylation calling and M-bias trimming was performed using the ‘bistro’ methylation caller (version 0.2.0) (https://github.com/stephenkraemer/bistro). Automatic M-bias detection was done using the 'binomp' algorithm to remove both the gap repair nucleotides introduced by the tagmentation reaction (first 9 bp following sequencing primer 2) and additional read positions with M-bias. Reads with a mapping quality ≥25 and nucleotides with Phred-scaled quality score ≥25 were considered for further analysis. Bisulfite conversion rates were estimated using the autosomal CHH methylation levels. Whole genome bisulfite sequencing data for LT-HSC isolated from aged and pI:pC/CON treated mice can be downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, under the accession number GSE200337 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE200337). Whole genome bisulfite sequencing data for LT-HSC isolated from young mice can be downloaded from the GEO under accession number GSE52709 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE52709).

Calculation of biological age using DNA methylome clock

The biological age of LT-HSCs was calculated using the murine multi-tissue DNA methylation clock (435 CpGs) published by Meer and co-authors (Meer et al., 2018). Coordinates of clock CpG sites and their weights on calculating the methylation age were downloaded from (Meer et al., 2018). DNA methylation values of CpGs that were not covered in TWGBS data from an individual experimental repeat were imputed by the average DNA methylation value calculated from the other replicates per group.

Identification and analysis of differentially methylated regions

In Figure S5, Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were called by pairwise comparison between pIpC- and PBS-treated HSCs using dispersion shrinkage for sequencing data. Differential methylation at each CpG site was tested without smoothing. DMRs were defined by a minimal length of 50 bp and a minimal number of three consecutive CpGs with at least a methylation difference of 10% and a p-value of 0.05. DMRs were clustered using hierarchical clustering (Ward method) of the z-score normalized average DNA methylation levels. Partitioning was performed with the cutreeHybrid algorithm of the dynamicTreeCut package and the following parameters: deepSplit = 2, minClusterSize = 0.005 × number of DMRs, pamStage = False, and minGap = 0.5. The ‘Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool’ (GREAT, version 3.0.0) with default parameters was used to annotate DMRs to nearby genes and perform Gene Ontology and MSigDB pathway enrichment analysis based on a binomial test over genomic regions (e.g. DMRs). The mm10 mouse genome was used as background. Enriched gene sets with a binominal fold enrichment >2.0 were ranked according to their -log10(binominal p-value). The ‘Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment’ tool (HOMER) was used to find known transcription factor binding motifs in DMRs and perform motif enrichment analysis based on a hypergeometric test over genomic regions (e.g. DMRs). The mm10 mouse genome was used as background. Enriched transcription factor binding motifs were ranked according to their hypergeometric p-value.

Time-lapse imaging and single cell tracking

Time-lapse imaging and cell tracking were performed as previously described (Cabezas-Wallscheid et al., 2017; Haetscher et al., 2015; Rieger et al., 2009). LT-HSCs were FACS purified from pI:pC-treated or control mice and seeded in 24-well plates equipped with silicon culture inserts (IBIDI, Martinsried, Germany). Cells were pre-cultured in StemSpan SFEM medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 10 ng/ml Flt3-Ligand, 50 ng/ml SCF, 10 ng/ml TPO, 5 ng/ml IL-3, 10 ng/ml IL-11, 0.3 IU/ml Epo, 20 ng/ml IL-7 (PeproTech) recombinant murine cytokines and 0.1 ng/ml rat anti-mouse CD48-PE (clone HM48-1, eBioscience) for 17 h in a standard cell culture incubator at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 for CO2 saturation, before being gastight sealed with adhesive tape for live-cell microscopy. Time-lapse imaging was performed using a CellObserver system (Zeiss, Hallbergmoos, Germany) at 37 °C. Phase contrast images were acquired every 2-3 min over 7 days using a 10x phase contrast objective (Zeiss), and an AxioCamHRm camera (at 1388x1040 pixel resolution) with a self-written VBA module remote controlling Zeiss AxioVision 4.8 software. PE fluorescence (Filter set F46-004, AHF Analyzetechnik at 600ms) was detected every 2 hours. Cells were individually tracked for their fates (apoptosis, division, loss of stemness) using a self-written computer program (TTT) in concert with manual verification and analysis of results. The generation time of an individual cell was defined as the time span from cytokinesis of its mother cell division to its own division. Dead cells were identified by their shrunken, non-refracting and immobile appearance. Induction of differentiation was detected by the appearance of PE fluorescence (CD48 expression). The analysis did not rely on data generated by an unsupervised computer algorithm for automated tracking.

Single cell transcriptomic analysis

Single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNAseq)

LT-HSCs were purified by FACS, and single LT-HSC cells were subsequently captured on a small sized IFC using the Fluidigm C1 system. Briefly, cells were washed, re-suspended in PBS supplemented with C1 suspension buffer in a 4:1 ratio and 400 cells/μl were loaded onto the chip. After cell capture, each position on the chip was imaged and only single cells were included in the downstream library preparation and analysis. cDNA was then amplified with the SMARTer Ultra Low RNA kit (Clontech) including ERCC RNA spike-ins (ThermoFisher Scientific# 4456740). Bulk controls were also processed for each C1 run using 100 cells and the same reagent mixes as used for the C1. Amplified cDNA was checked with the TapeStation to assess both quality and yield. Sequencing libraries were produced with the Illumina Nextera XT kit according to the adopted Fluidigm protocol. All single cells from one C1 run (about 70 cells on average) were pooled and sequenced 1x50 bp reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine resulting in 2-3 million reads per cell.

scRNAseq bioinformatic analysis

For each cell, reads were aligned to the murine genome (ERCC sequences concatenated to GRCm38.p4 version 84, softmasked) with STAR version 2.5. For each cell, between 70 and 90 % of the reads were uniquely mapped. Raw counts were quantified from position-sorted alignment files with HTSeq-count using mode 'union' and default quality thresholds of 10. Cells were excluded as low quality if more than 40 % of counts were in ERCCs, or if the counts in murine exons were more than 10 % mitochondrial or less than 0.5 Mio in total. In addition, cells for which less than 2,000 genes were expressed were excluded; resulting in a total of 564 cells passing quality control. Size-factor normalization (Love et al., 2014) was used to identify variable genes using a log-linear fit capturing the relationship between mean and squared coefficient of variation (CV) of the log-transformed, TPM data (Brennecke et al., 2013). Genes with a squared CV greater than the estimated squared baseline CV were then considered as variable beyond technical noise. This filter for highly variable genes resulted in 5176 genes. This set of variable genes was used as input for downstream analysis, including visualization and clustering. A projection analysis was performed to integrate our own data with a larger hematopoietic dataset covering a wider range of blood stem and progenitor cells (Nestorowa et al., 2016). To this end, the intersection of variable genes identified in (Nestorowa et al., 2016) and our data was established. A diffusion map representation of the 1656 cells from (Nestorowa et al., 2016) was then generated, based on the 1616 genes that were variable above technical noise both in our data and the data from (Nestorowa et al., 2016). Our cells were then projected into the diffusion map span based on the diverse set of stem and progenitor cells from (Nestorowa et al., 2016) using the destiny R package (Angerer et al., 2016). SC3 consensus clustering (Figure S5A) was performed as described in (Kiselev et al., 2017). scRNA-seq data can be downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, under the accession number GSE200979 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE200979).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean +/− standard deviation. Statistical analyses were carried out either in comparison to the control group, or between groups. For pairwise comparisons of single variables, two-sided Mann-Whitney tests were applied (Fig.1B, C; Fig.3A, B, D, G, H, I, K, L; Fig 4D). Comparisons of more than two groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks. If the ANOVA provided evidence that group means differed, Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were applied to determine which means amongst the set of means differed from the rest (Fig. 1H, I; Fig.2B, C, F, G; Fig.3D). For cell proliferation data relating to LRCs and nLRCs (Fig 4E), a linear mixed model with two fixed variables (divisional history and treatment) and one random variable (mouse ID) was used. Main result here is the interaction term between treatment and divisional history, indicating whether divisional history affects the treatment results. Variables that showed a skewed data distribution were Log10 transformed (Fig 2F, G, H; Fig. 4E, F, G). To determine whether there was a statistically significant difference in the estimated number of HSC clones following treatment with pI:pC (Fig. 3C), we performed a two-sided signed likelihood ratio test using the R package cvequality (version 0.2.0; Marwick and Krishnamoorthy, 2019). To evaluate the cumulative frequency distribution of CD48 expression on LT-HSCs, the data was fitted to Gaussian distribution curves by least squares regression. Best-fit values of the control and treatment datasets were compared to each other by extra sum-of-squares F test (Fig.1D). Log-rank Mantel-Cox test was used to test for statistically significant changes of first LT-HSC division between the control and treatment group (Fig.1E). Statistical significance is indicated by one (P < 0.05), two (P < 0.01) or three (P < 0.001) asterisks. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0b software (GraphPad Software, Inc., SanDiego, CA, http.//www.graphpad.com) and R software version 4.1.0 (R core development team).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HSCs fail to recover functional potency after inflammatory/infection challenge.

Discrete challenges have a cumulative effect, even if separated by weeks or months.

Inflammation in early life accelerates the cellular and molecular aging of HSCs.

Mice exposed to inflammation develop features of aged human hematopoiesis.

Acknowledgements:

We thank members of the Division of Experimental Hematology for supporting the experimental work described in this manuscript, and Steven Lane, Thordur Oskarsson, Martin Sprick and Leonard Zon for critical proofreading of this work. We also thank the Center for Preclinical Research DKFZ core facility; the Flow Cytometry DKFZ core facility; the Single Cell Open Lab DKFZ Core Facility; the Genomics and Proteomics DKFZ Core Facility; the Omics IT and Data Management DKFZ Core Facility; and Damir Krunic from the Light Microscopy DKFZ core facility. This work was supported by funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) SFB873 (MDM and MAGE), FOR2674 (MDM, DBL, BB, KR and JPM) and SFB834 (MAR and MF); the Deutsche Jose Carreras Leukamiestiftung (grant R15/09 to MDM and 10R/2017 to MAR); the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung (grant 10.16.1.023MN to MDM); the Helmholtz Zukunftsthema Aging and Metabolic Programming (AMPro) ZT-0026 (MDM and DBL); the DKFZ-MOST German-Israel Cooperative Research Program (MDM); the Cancer Transitional Research And Exchange Program (Cancer-TRAX) within the German-Israeli Helmholtz International Research School (SS); the National Institutes of Health RO1 DK056638 (PF), R01 DK112976 (PF), F31HL154661 (DL), R35HL155672 (KYK); the Wilhelm-Sander Foundation (grant 2018-116.1 to MAR); and the Dietmar Hopp Stiftung (MDM and MAGE). Graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com. This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Paul Frenette, a truly outstanding scientist, colleague and friend.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrejak C, Almeida DV, Tyagi S, Converse PJ, Ammerman NC, and Grosset JH (2015). Characterization of mouse models of Mycobacterium avium complex infection and evaluation of drug combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59, 2129–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerer P, Haghverdi L, Buttner M, Theis FJ, Marr C, and Buettner F (2016). destiny: diffusion maps for large-scale single-cell data in R. Bioinformatics 32, 1241–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, and Goodell MA (2010). Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-gamma in response to chronic infection. Nature 465, 793–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I, Bock C, Garrison BS, Smith ZD, Gu H, Meissner A, and Rossi DJ (2013). Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell 12, 413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biino G, Santimone I, Minelli C, Sorice R, Frongia B, Traglia M, Ulivi S, Di Castelnuovo A, Gogele M, Nutile T, et al. (2013). Age- and sex-related variations in platelet count in Italy: a proposal of reference ranges based on 40987 subjects' data. PLoS One 8, e54289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockamp E, Antunes C, Maringer M, Heck R, Presser K, Beilke S, Ohngemach S, Alt R, Cross M, Sprengel R, et al. (2006). Tetracycline-controlled transgenic targeting from the SCL locus directs conditional expression to erythrocytes, megakaryocytes, granulocytes, and c-kit-expressing lineage-negative hematopoietic cells. Blood 108, 1533–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, and Usadel B (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke P, Anders S, Kim JK, Kolodziejczyk AA, Zhang X, Proserpio V, Baying B, Benes V, Teichmann SA, Marioni JC, et al. (2013). Accounting for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq experiments. Nat Methods 10, 1093–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas-Wallscheid N, Buettner F, Sommerkamp P, Klimmeck D, Ladel L, Thalheimer FB, Pastor-Flores D, Roma LP, Renders S, Zeisberger P, et al. (2017). Vitamin A-Retinoic Acid Signaling Regulates Hematopoietic Stem Cell Dormancy. Cell 169, 807–823 e819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiado F, Pietras EM, and Manz MG (2021). Inflammation as a regulator of hematopoietic stem cell function in disease, aging, and clonal selection. J Exp Med 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapes T, Lefkopoulos S, and Trompouki E (2016). Stress and Non-Stress Roles of Inflammatory Signals during HSC Emergence and Maintenance. Front Immunol 7, 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esplin BL, Shimazu T, Welner RS, Garrett KP, Nie L, Zhang Q, Humphrey MB, Yang Q, Borghesi LA, and Kincade PW (2011). Chronic exposure to a TLR ligand injures hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol 186, 5367–5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, and Trumpp A (2009). IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature 458, 904–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng CG, Weksberg DC, Taylor GA, Sher A, and Goodell MA (2008). The p47 GTPase Lrg-47 (Irgm1) links host defense and hematopoietic stem cell proliferation. Cell Stem Cell 2, 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulop T, Witkowski JM, Olivieri F, and Larbi A (2018). The integration of inflammaging in age-related diseases. Semin Immunol 40, 17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganuza M, Hall T, Finkelstein D, Wang YD, Chabot A, Kang G, Bi W, Wu G, and McKinney-Freeman S (2019). The global clonal complexity of the murine blood system declines throughout life and after serial transplantation. Blood 133, 1927–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, and Woodman RC (2004). Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood 104, 2263–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S, Hansson J, Klimmeck D, Loeffler D, Velten L, Uckelmann H, Wurzer S, Prendergast AM, Schnell A, Hexel K, et al. (2015). Inflammation-Induced Emergency Megakaryopoiesis Driven by Hematopoietic Stem Cell-like Megakaryocyte Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 17, 422–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haetscher N, Feuermann Y, Wingert S, Rehage M, Thalheimer FB, Weiser C, Bohnenberger H, Jung K, Schroeder T, Serve H, et al. (2015). STAT5-regulated microRNA-193b controls haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell expansion by modulating cytokine receptor signalling. Nat Commun 6, 8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartsock RJ, Smith EB, and Petty CS (1965). Normal Variations with Aging of the Amount of Hematopoietic Tissue in Bone Marrow from the Anterior Iliac Crest. A Study Made from 177 Cases of Sudden Death Examined by Necropsy. Am J Clin Pathol 43, 326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Malmierca P, Vonficht D, Schnell A, Uckelmann HJ, Bollhagen A, Mahmoud MAA, Landua SL, van der Salm E, Trautmann CL, Raffel S, et al. (2022). Antigen presentation safeguards the integrity of the hematopoietic stem cell pool. Cell Stem Cell 29, 760–775 e710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinge A, He J, Bartram J, Javier J, Xu J, Fjellman E, Sesaki H, Li T, Yu J, Wunderlich M, et al. (2020). Asymmetrically Segregated Mitochondria Provide Cellular Memory of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Replicative History and Drive HSC Attrition. Cell Stem Cell 26, 420–430 e426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormaechea-Agulla D, Le DT, and King KY (2020). Common Sources of Inflammation and Their Impact on Hematopoietic Stem Cell Biology. Curr Stem Cell Rep, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormaechea-Agulla D, Matatall KA, Le DT, Kain B, Long X, Kus P, Jaksik R, Challen GA, Kimmel M, and King KY (2021). Chronic infection drives Dnmt3a-loss-of-function clonal hematopoiesis via IFNgamma signaling. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1428–1442 e1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, and Raj K (2018). DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet 19, 371–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]