Abstract

Expression of the immune checkpoint programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) is increased in ovarian cancer (OC) and correlates with poor prognosis. Interferon-γ (IFNγ) induces PD-L1 expression in OC cells, resulting in their increased proliferation and tumor growth, but the mechanisms that regulate the PD-L1 expression in OC remain unclear. Here, we show that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is associated with increased levels of STAT1, Tyr-701 pSTAT1 and Ser-727 pSTAT1. Suppression of JAK1 and STAT1 significantly decreases the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells, and STAT1 overexpression increases the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression. In addition, IFNγ induces expression of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and IRF1 suppression attenuates the IFNγ-induced gene and protein levels of PD-L1. Chromatin immunoprecipitation results show that IFNγ induces PD-L1 promoter acetylation and recruitment of STAT1, Ser-727 pSTAT1 and IRF1 in OC cells. Together, these findings demonstrate that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is regulated by JAK1, STAT1, and IRF1 signaling, and suggest that targeting the JAK1/STAT1/IRF1 pathway may provide a leverage to regulate the PD-L1 levels in ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Interferon-γ, Ovarian cancer, PD-L1, STAT1, Transcriptional regulation

1. Introduction

High expression of the immune checkpoint programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1, CD274) in solid tumors, including ovarian cancer (OC), inhibits T cell-mediated antitumor responses, thus promoting tumor immune evasion, cancer progression, and metastasis [1–5]. In addition, PD-L1 has immune independent, cell intrinsic functions that include increased cancer cell proliferation, cell survival, mTOR signaling, DNA damage response, and development of cisplatin resistance [6–10]. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate the PD-L1 expression in cancer cells is required to modulate the PD-L1 levels and the associated cancer cell functions, but the mechanisms that regulate the PD-L1 expression in OC cells remain largely unknown.

The expression of PD-L1 in cancer cells, including OC, is upregulated by type II interferon, IFNγ [11,12]. IFNγ is produced mainly by activated T cells, but also by cancer cells in response to radiation therapy or immune checkpoint blockade used in cancer treatment [12]. IFNγ signals primarily via the Janus kinase (JAK)/Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway to induce expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) [13–15]. Binding of IFNγ to its receptors IFNγR1 and IFNγR2 triggers a signaling cascade, in which activated JAK phosphorylates STAT1 at Tyr701 residue. Phosphorylated STAT1 then dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific gamma activated sequences (GAS), resulting in transcription of ISGs [13–15]. In some cells, STAT1 is phosphorylated also at Ser727, which enhances its transcriptional activity [16,17]. In addition, IFNγ induces expression of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1), potentially enabling its interaction with STAT1 and binding of the STAT1-IRF1 complexes to the GAS elements [18,19].

We have recently shown that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is mediated by the proto-oncogene Bcl3 and by p65 NFκB, resulting in the increased proliferation and migration of OC cells [20,21]. In this study, we have investigated the role of JAK1/STAT1 signaling in the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC. Our results demonstrate that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on JAK1, STAT1, and IRF1 signaling. Furthermore, IFNγ increases acetylation of human PD-L1 promoter in OC cells, and promoter recruitment of STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, and IRF1. Together, these data indicate that the IFNγ/IRF1/JAK1/STAT1 pathway may serve as a therapeutic target to modulate the PD-L1 levels in ovarian cancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Human ovarian cancer SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured (5 × 105 cells/ml) in 6-well plates in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and antibiotics at 37 °C with 5% CO2. For treatment with IFNγ, human recombinant IFNγ (285-IF-100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was reconstituted in sterile water. Cell viability was measured by using Trypan Blue exclusion.

2.2. Transfections

Human JAK1 (sc-35,719), STAT1 (sc-44,123), IRF1 (sc-35,706), and non-silencing (sc-37,007) small interfering RNAs (siRNA) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Prior to transfection, cells were seeded into a 6-well plate and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C in antibiotic-free RPMI medium supplement with 10% FBS for 24 h to about 80% confluence. For each transfection, 80 pmol of either non-silencing control siRNA or respective siRNA were used. Cells were transfected 6 h in siRNA transfection medium with siRNA transfection reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After transfection, fresh medium with antibiotics was added, and the cells were grown for 24 h before treatment.

For STAT1 overexpression experiments, cells were transfected with STAT1 activation (sc-400,086-ACT) or control (sc-437,275) plasmids according to manufacturer’s instructions (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described [20].

2.3. Real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by using RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The iScript one-step RT-PCR kit with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used as a supermix and 20 ng/μ1 of RNA was used as template on a Bio-Rad MyIQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The primers used for quantification of human JAK1, STAT1, IRF1, PD-L1 and actin mRNA were purchased from Qiagen (Germantown, MD). The mRNA values are expressed as a percentage of control or untreated (UT) samples, which were arbitrarily set as 100%.

2.4. Western analysis

Denatured proteins were separated on 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond C; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Membranes were blocked with a 5% (w/v) nonfat dried milk solution containing 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBSTM), and incubated with PD-L1 (E1L3N; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), JAK1 (#66466–1-Ig; Proteintech), STAT1 (#9172; Cell Signaling), Tyr701-pSTAT1 (#7649; Cell Signaling), Ser727-pSTAT1 (#8826S; Cell Signaling), IRF1 (sc-74,530; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or actin (A5060–200 UL; Sigma) antibodies diluted in TBSTM. After washing, the membranes were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary anti-rabbit (Novus NB7185) or anti-mouse (Novus NB7570) antibodies (dilution 1:5000) and the labeled proteins were detected using the ECL detection system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). To confirm equivalent amounts of loaded proteins, the membranes were stripped and re-probed with control anti-actin antibody.

2.5. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP analysis was performed as described [22]. Briefly, proteins and DNA were cross-linked by formaldehyde, and cells were washed and sonicated. The lysates were centrifuged (15,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant extracts were diluted with ChIP dilution buffer and pre-cleared with Protein A/G Agarose (sc-2003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight at 4 °C, using STAT1 (#9172; Cell Signaling), Tyr701-pSTAT1 (#7649; Cell Signaling), Ser727-pSTAT1 (#8826S; Cell Signaling), IRF1 (sc-74,530; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), histone H3 (ab1791; Abeam), and Lys9 ac-histone H3 (#9649; Cell Signaling) antibodies. Following immunoprecipitation, the samples were incubated with Protein A/G Agarose (overnight, 4 °C), and the immune complexes were collected by centrifugation (150 g, 5 min, 4 °C), washed, and extracted with 1% SDS–0.1 M NaHCO3. After reversing the cross-linking, proteins were digested with proteinase K, and the samples were extracted with phenol/chloroform, followed by precipitation with ethanol. The pellets were resuspended in nuclease-free water and subjected to real time PCR. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR (25 μ1 reaction mixture) using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix and the Bio-Rad MyIQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Each immunoprecipitation was performed at least three times using different chromatin samples, and the occupancy was calculated by using negative control primers, which detect specific genomic ORF-free DNA sequence that does not contain any binding sites for any known transcription factors. The results were calculated as a fold difference in STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, IRF1, histone H3, and ac-histone H3 occupancy at the STAT1 and IRF1 binding sites compared to the control negative locus that does not bind any transcription factors. The PD-L1 primers used for real time PCR were as follows: PDL1-STAT1 forward, 5′-TGGGTCTGCTGCTGACTTTTTA-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGAGGGGTAAGAGCTTAAGGTTAC-3’; PD-L1-IRF1 forward, 5′-TTCCCGGTGAAAATCTCATT -3′ and reverse, 5′-GGTATCTAGTGTTGGTGTCC -3′.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The results represent at least three independent experiments. Numerical results are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by using an InStat software package (GraphPAD, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was evaluated by using one-way ANOVA Tukey-post Hoc-test, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

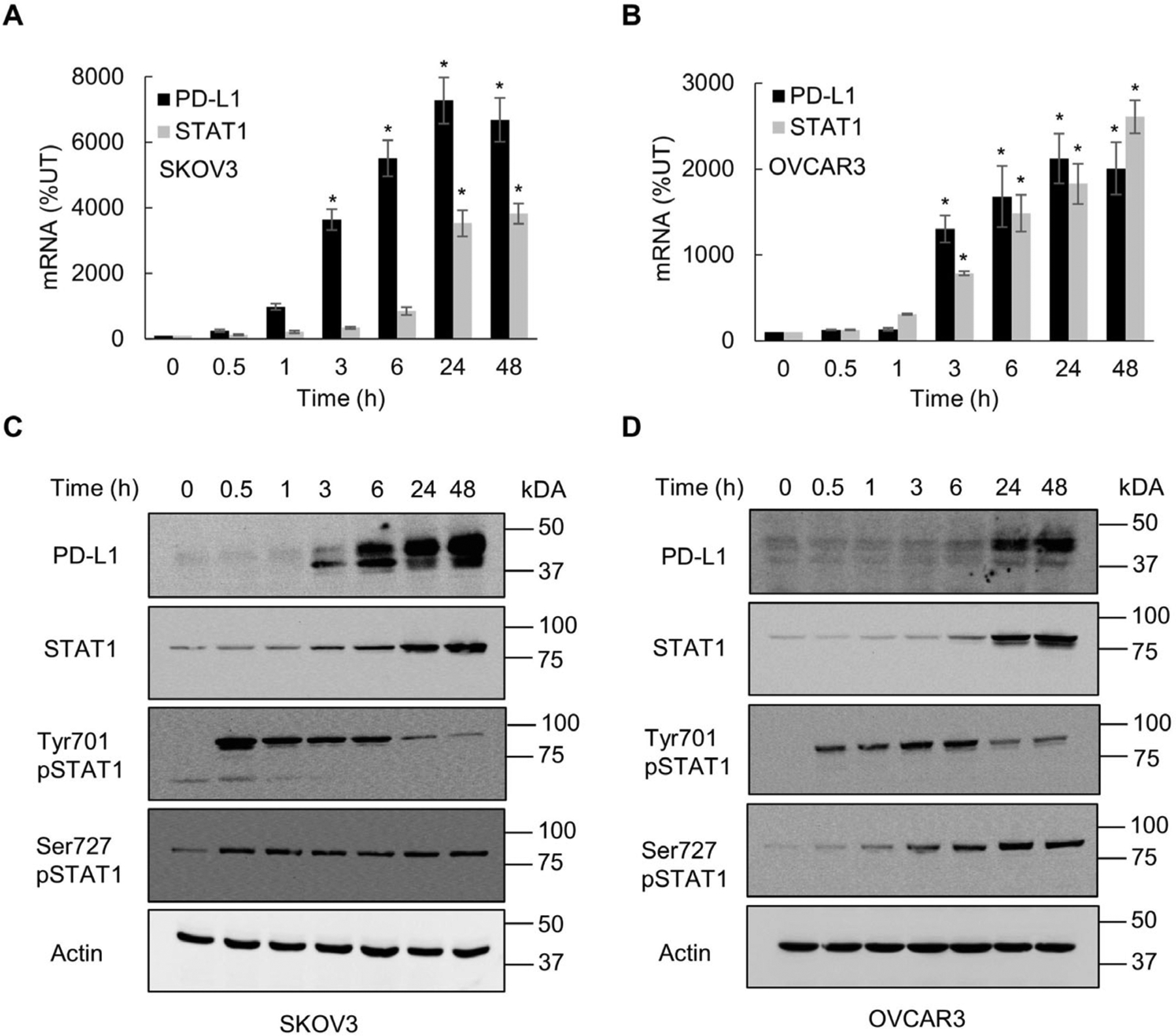

3.1. IFNγ induces STAT1 signaling in OC cells

IFNγ induces PD-L1 expression in human OC cells, resulting in their increased proliferation and migration [11,20,21,23,24]. Since IFNγ signals primarily via the JAK1/STAT1 pathway [13–15], we analyzed whether IFNγ induces STAT1 signaling in OC cells. As shown in Fig. 1A–D, IFNγ (50 ng/mL) greatly increased STAT1 and PD-L1 mRNA and protein levels in ovarian cancer SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. However, in the absence of IFNγ, unstimulated SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells expressed only low protein levels of PD-L1 and STAT1 (Fig. 1 C, D). Within 30 min after stimulation, IFNγ induced a robust but transient phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 in both OC cells (Fig. 1C, D). In addition, IFNγ induced STAT1 phosphorylation at Ser727; however, in contrast to Tyr701 phosphorylation, STAT1 phosphorylation at Ser727 gradually increased and was sustained 48 h after IFNγ stimulation (Fig. 1C, D).

Fig. 1.

IFNγ induces STAT1 signaling in OC cells. Real time qRT-PCR of PD-L1 and STAT1 mRNA in SKOV3 (A) and OVCAR3 (B) cells incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. Western blotting of PD-L1, STAT1, Tyr701-pSTAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1 and control actin analyzed in whole cell extracts (WCE) of SKOV3 (C) and OVCAR3 (D) cells incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. The values represent the mean +/−SE (n = 3); an asterisk denotes a statistically significant (* p < 0.05) change compared to control untreated (UT) cells.

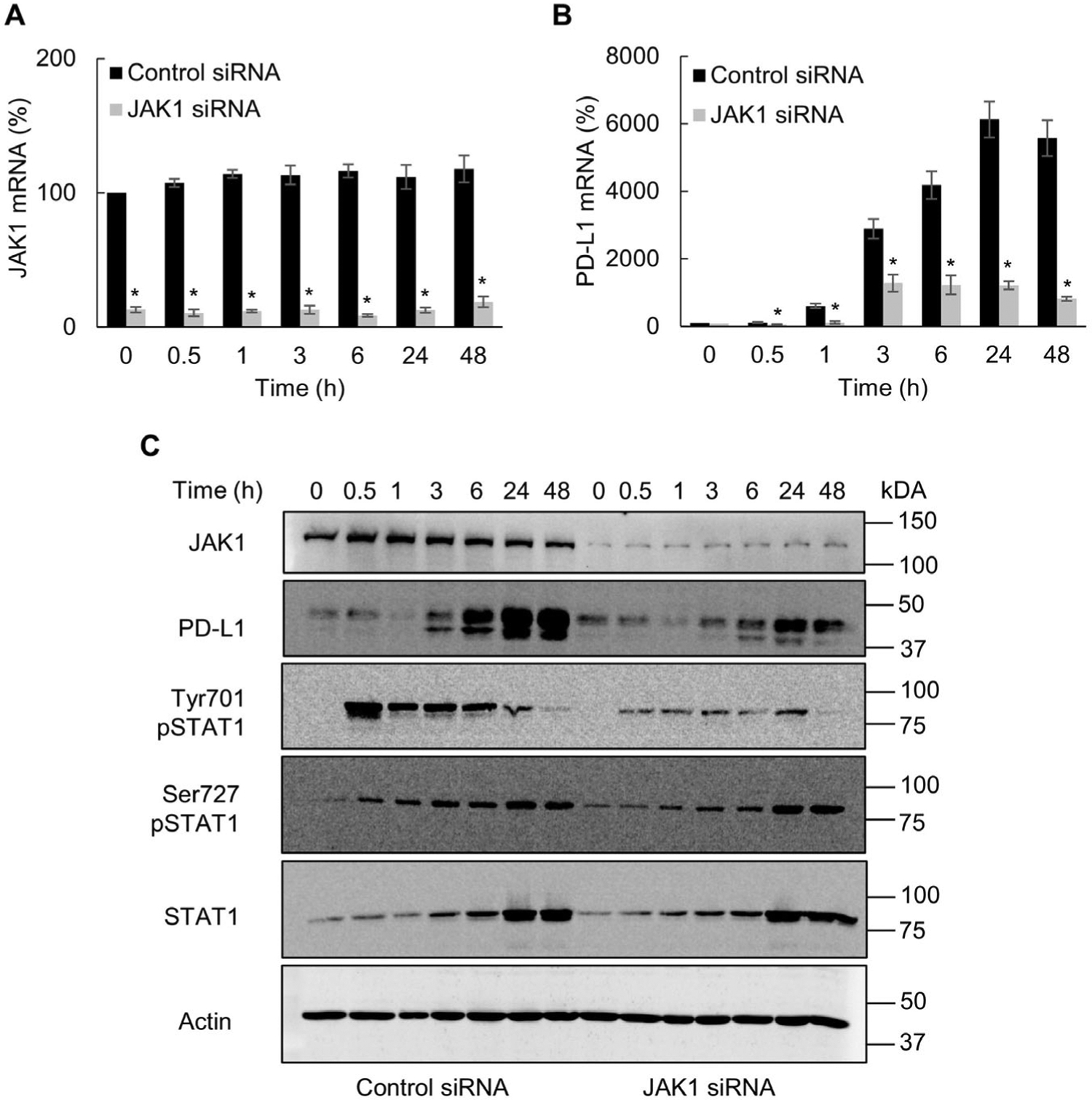

3.2. IFNγ induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on JAK1, which mediates Tyr701 STAT1 phosphorylation

Since Tyr701 phosphorylation of STAT1 is mediated by the JAK1 kinase [13–15], we analyzed whether the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on JAK1. As shown in Fig. 2, suppression of JAK1 by siRNA significantly decreased the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 mRNA and protein levels in OC cells, compared to cells transfected with control siRNA. Furthermore, JAK1 suppression greatly decreased the IFNγ-induced STAT1 phosphorylation at Tyr701, while it did not have a substantial impact on Ser727 phosphorylation or the total protein levels of STAT1 in IFNγ stimulated OC cells (Fig. 2C). These data show that JAK1 mediates the IFNγ-induced STAT1 Tyr701 phosphorylation and PD-L1 expression in OC cells.

Fig. 2.

IFNγ induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on JAK1. Gene expression of JAK1 (A) and PD-L1 (B) measured by RT-PCR in SKOV3 cells transfected with control and JAK1 siRNA and incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. (C) Western blotting of JAK1, PD-L1, Tyr701- pSTAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, STAT1, and control actin analyzed in WCE of SKOV3 cells transfected with control and JAK1 siRNA and incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. The values represent the mean +/−SE (n = 3); an asterisk denotes a statistically significant (* p < 0.05) change compared to cells transfected with control siRNA.

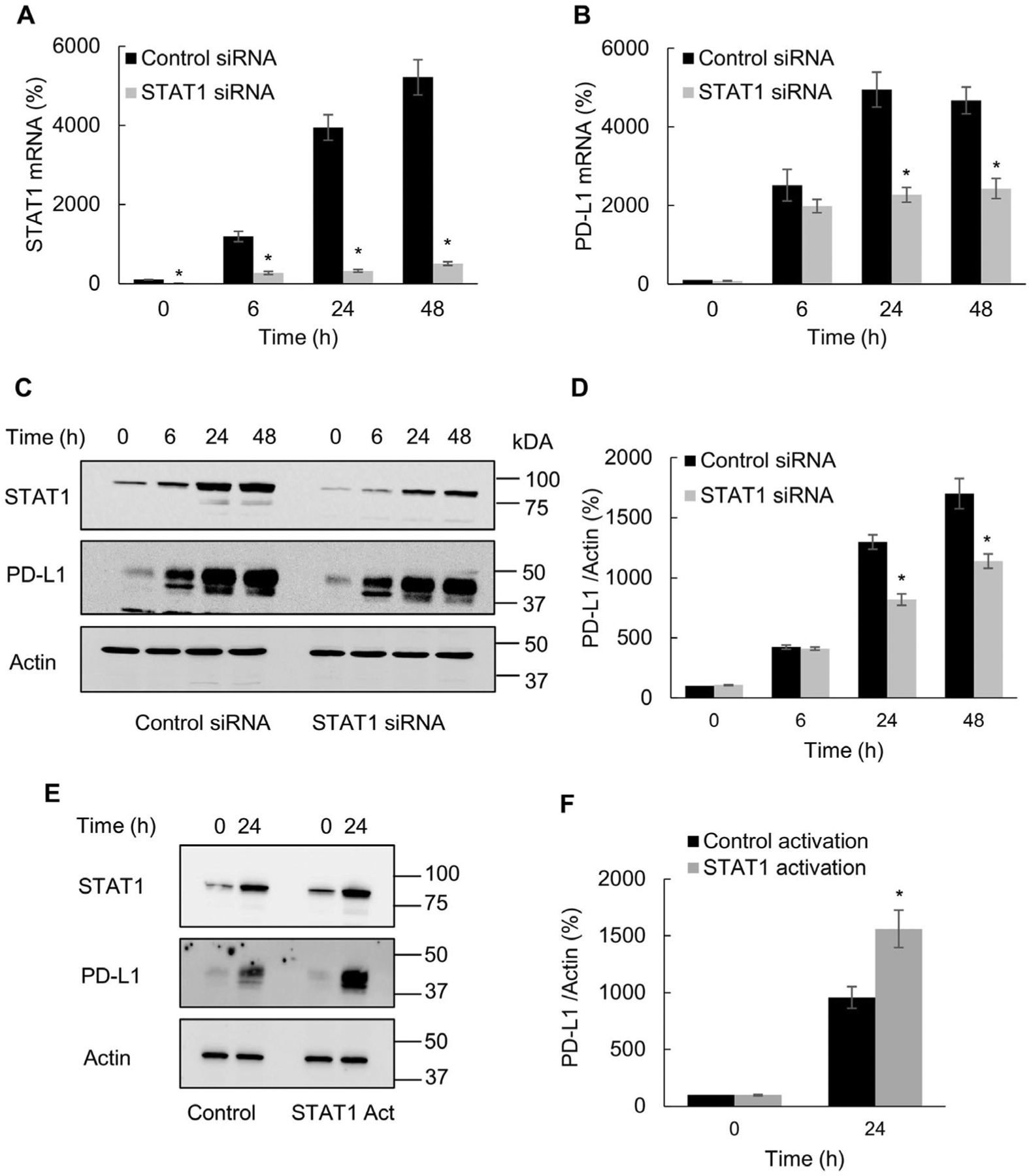

3.3. IFNγ induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on STAT1

STAT1 expression is increased in OC tumors and correlates with PD-L1 expression [25,26]. Since our data showed that IFNγ induces STAT1 expression and phosphorylation in OC cells (Fig. 1), we wanted to determine whether the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on STAT1. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, STAT1 suppression by siRNA significantly decreased the IFNγ induced PD-L1 gene expression 24 and 48 h after IFNγ stimulation. In addition, STAT1 suppression significantly reduced the PD-L1 protein levels in OC cells stimulated with IFNγ for 24 and 48 h (Fig. 3C, D), suggesting that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on STAT1. To validate these results, we also transfected cells with STAT1 activation plasmid. As shown in Fig. 3E and F, STAT1 activation significantly increased the PD-L1 protein levels in IFNγ-stimulated cells. Together, these results show that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on STAT1.

Fig. 3.

IFNγ induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on STAT1. Gene expression of STAT1 (A) and PD-L1 (B) measured by RT-PCR in SKOV3 cells transfected with control and STAT1 siRNA and incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. (C) Western blotting of STAT1, PD-L1 and actin analyzed in WCE of SKOV3 cells transfected with control and STAT1 siRNA and incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. (D) Densitometric evaluation of PD-L1 protein levels shown in panel C; PD-L1 densities were normalized to actin and expressed as % compared with control UT cells. (E) Western blotting and (F) densitometric evaluation of PD-L1 levels in SKOV3 cells transfected with control and STAT1 activation plasmids and incubated 24 h with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. The values represent the mean +/−SE (n = 3); an asterisk denotes a statistically significant (* p < 0.05) change compared to cells transfected with control siRNA or plasmid.

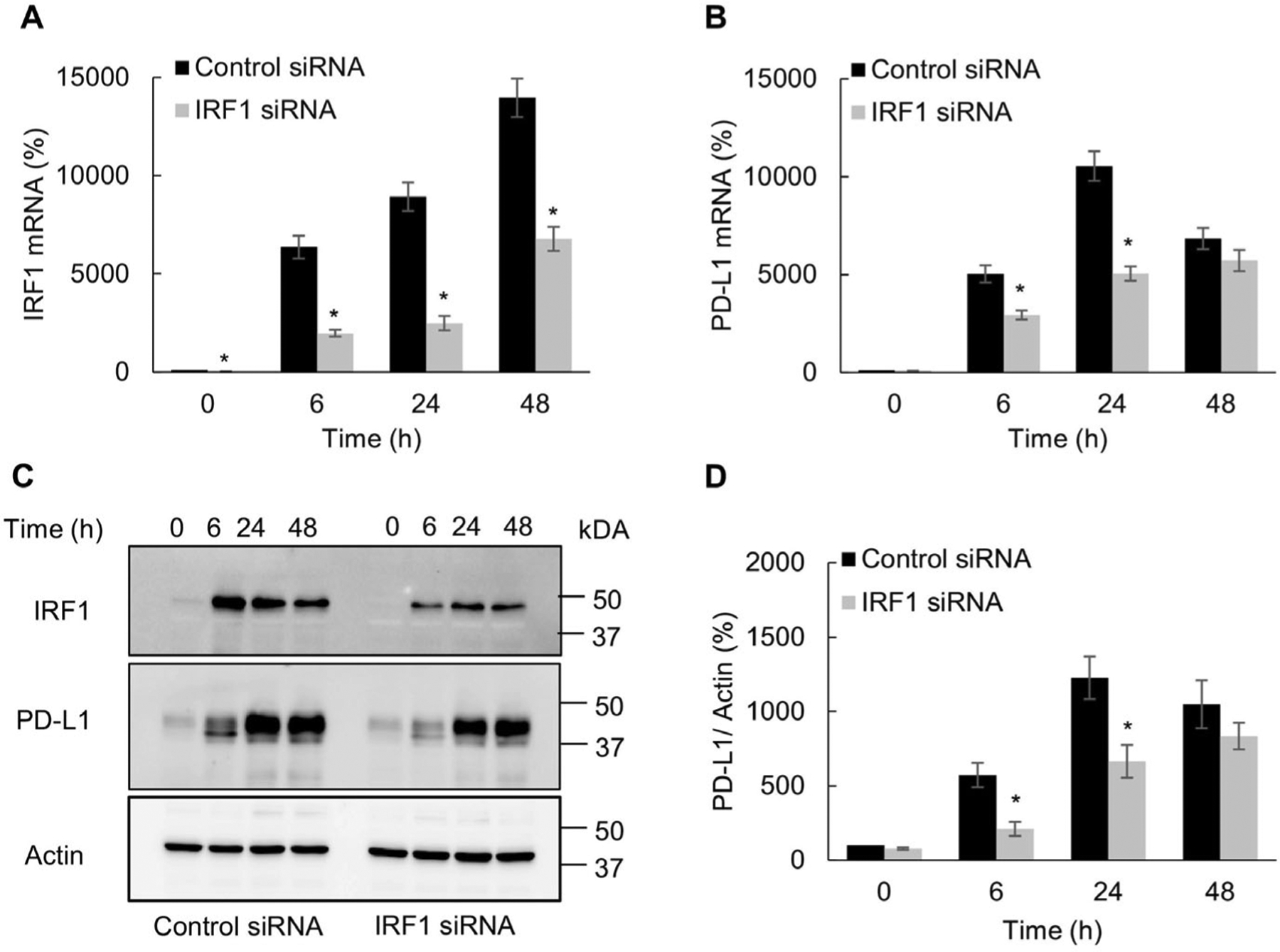

3.4. IFNγ induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on IRF1

Since the transcription factor IRF1 is involved in IFNγ signaling and regulation of immune genes [19,27], we analyzed whether the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells was dependent on IRF1. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, IRF1 suppression by siRNA significantly decreased the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 gene expression; however, in contrast to JAK1 (Fig. 2) and STAT1 (Fig. 3) suppression, the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 gene expression was decreased by IRF1 suppression only in 6- and 24-h stimulated cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, IRF1 suppression reduced the PD-L1 protein levels in cells stimulated with IFNγ for 6 and 24 h by about 50%, while the PD-L1 protein levels in cells stimulated with IFNγ for 48 h were not significantly affected (Fig. 4C, D). Together, these results indicate that during the early time points, the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on IRF1.

Fig. 4.

IFNγ induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on IRF1. Gene expression of IRF1 (A) and PD-L1 (B) measured by RT-PCR in SKOV3 cells transfected with control and IRF1 siRNA and incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. (C) Western blotting of IRF1, PD-L1 and actin analyzed in WCE of SKOV3 cells transfected with control and IRF1 siRNA and incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. (D) Densitometric evaluation of PD-L1 protein levels shown in panel C; PD-L1 densities were normalized to actin and expressed as % compared with control UT cells. The values represent the mean +/−SE (n = 3); an asterisk denotes a statistically significant (* p < 0.05) change compared to cells transfected with control siRNA.

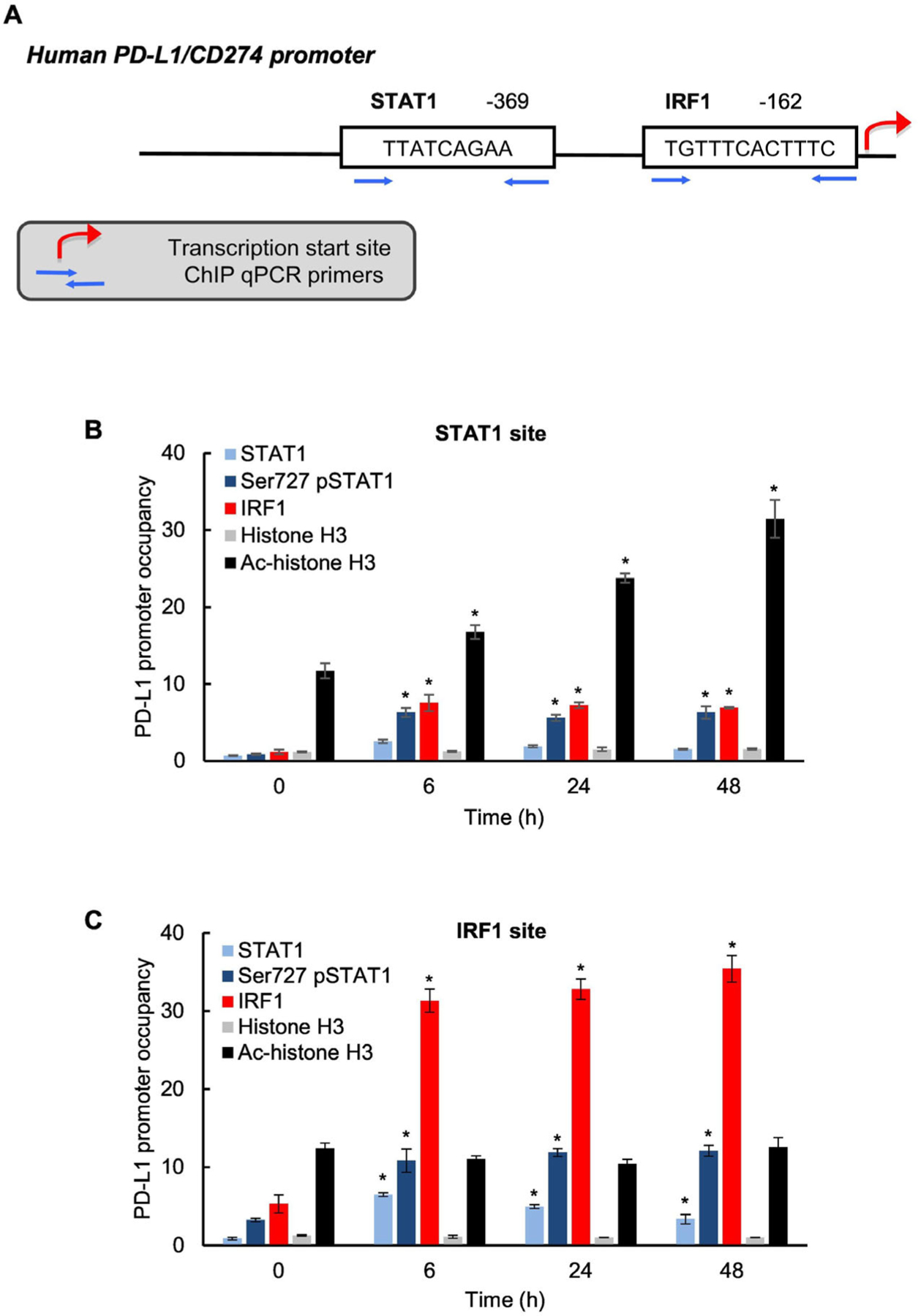

3.5. IFNγ induces PD-L1 promoter acetylation and occupancy by STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, and IRF1 in OC cells

Our data showed that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on the transcription factors STAT1 (Fig. 3) and IRF1 (Fig. 4). Thus, we tested whether IFNγ induces recruitment of STAT1 and IRF1 to endogenous PD-L1 promoter in OC cells. In addition, since Ser727 phosphorylation enhances STAT1 transcriptional activity [16,17], we analyzed whether IFNγ induces the PD-L1 promoter occupancy by Ser727-pSTAT1. The human PD-L1 promoter contains putative binding sites for STAT1 (TTATCAGAA) located at position −369 upstream from transcription start site (TSS) and IRF1 (TGTTTCACTTTC) located at position −162 upstream from the TSS (Fig. 5A). To analyze whether the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is associated with a promoter recruitment of STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, and IRF1, we measured the PD-L1 promoter occupancy by STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, IRF1, histone H3, and acetylated (ac) histone H3 in IFNγ stimulated SKOV3 cells by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). As shown in Fig. 5B, IFNγ stimulation significantly increased occupancy of the STAT1 binding site by Ser727-pSTAT1, IRF1, and achistone H3. In addition, IFNγ increased recruitment of total STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, and IRF1 to the IRF1 site in PD-L1 promoter (Fig. 5C). Together, these results indicate that IFNγ induces PD-L1 transcription in OC cells by increasing acetylation of the PD-L1 promoter, and recruitment of STAT1, Ser727 pSTAT1 and IRF1.

Fig. 5.

IFNγ induces PD-L1 promoter acetylation and occupancy by STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1 and IRF1 in OC cells. (A) Schematic illustration of STAT1 and IRF1 binding sites in human PD-L1 promoter. Occupancy of STAT1 (B) and IRF1 (C) binding sites in human PD-L1 promoter by STAT1, Ser727-pSTAT1, IRF1, histone H3 and ac-histone H3 analyzed by chromatin immunopredpitation (ChIP) in SKOV3 cells incubated with 50 ng/mL IFNγ. The data are presented as fold difference in occupancy of the particular protein at the particular locus compared with the negative control human IGX1A (SA Biosciences) locus, which does not contain any transcription factors binding sites. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3); an asterisk denotes a statistically significant (* p < 0.05) change compared with UT cells.

4. Discussion

Depending on the cellular and molecular context, IFNγ can have both anti-tumor and pro-tumorigenic effects in OC [11,20,24,28–30]. One of the main pro-tumorigenic functions of IFNγ consists of the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression. The IFNγ-induced PD-L1 represses functions of activated T cells in ovarian tumors, resulting in immune evasion and tumor progression [11]. In addition, PD-L1 has T cell independent, tumor intrinsic functions that include increased cell survival, mTOR signaling, and proliferation of OC cells [6–10]. Thus, understanding the mechanisms of how IFNγ induces the PD-L1 expression in OC cells is essential to regulate the cancer cell functions controlled by PD-L1. Our results show that IFNγ induces expression of STAT1 and its Tyr-701 and Ser-727 phosphorylation, resulting in PD-L1 expression in OC cells. In addition, IFNγ induces acetylation of the PD-L1 promoter in OC cells, and the recruitment of STAT1, Ser-727 pSTAT1 and IRF1. Together, these findings demonstrate that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is regulated by JAK1, STAT1, and IRF1 signaling.

Human PD-L1 promoter has binding sites for the transcription factors Myc, hypoxia-inducible factors HIF1a/2a, AP-1, IRF1, STAT1, STAT3, and NFκB. We have recently shown that IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is mediated by the proto-oncogene Bcl3 and by p65 NFκB [20]. In addition, a recent study has found that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in ovarian carcinoma cells is mediated by c-Myc [31]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is regulated by STAT1 and IRF1 signaling. Our results show that while the maximum STAT1 protein expression is achieved 24–48 h after IFNγ stimulation (Figs. 2, 3), the maximum protein synthesis of IRF1 is achieved within 6 h after stimulation (Fig. 4). These data are consistent with the results demonstrating the dependence of PD-L1 expression on STAT1 and IRF1 (Figs. 3, 4): STAT1 suppression attenuates the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression 24 and 48 h after IFNγ stimulation (Fig. 3), while IRF1 suppression attenuates the PD-L1 expression induced 6 and 24 h after stimulation (Fig. 4). These results indicate that whereas IRF1 drives the early PD-L1 expression, STAT1 facilitates the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression at later time points in OC cells. Interestingly however, we have found that IFNγ induces PD-L1 promoter occupancy by both total STAT1/Ser727-pSTAT1 and IRF1 during the entire course of IFNγ stimulation (Fig. 5), even during time points when PD-L1 is not regulated by the particular transcription factor. These data suggest that IFNγ might induce a cooperative association between STAT1 and IRF1 in OC cells; even though IRF1 does not directly regulate the IFN-induced PD-L1 expression at later time points, it might be present in the transcriptional complex with STAT1 when STAT1 takes over the transcriptional regulation of PD-L1. In addition, it is possible that IRF1 has a different binding affinity for unphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of STAT1, which might have different biological functions. Indeed, a previous study has shown that unphosphorylated STAT1 binds to IRF1 to induce a gene-specific transcription [32].

Consistent with other studies that demonstrated that IFNγ activates JAK1 that phosphorylates STAT1 on Tyr701 [18,33], our results show that IFNγ quickly induces STAT1 Tyr701 phosphorylation in OC cells, and this is dependent on JAK1 (Figs. 1, 2). Importantly, our data demonstrate that the JAK1-mediated Tyr 701 phosphorylation of STAT1 in OC cells is required for the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression (Fig. 2). Since STAT1 activation induced by Tyr701 phosphorylation in OC cells has been associated with a development of cisplatin resistance [34], the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression might represent a link between the STAT1 Tyr701 phosphorylation and cisplatin resistance in OC cells. In contrast to JAK1 that phosphorylates STAT1 on Tyr701, several kinases have been associated with Ser727 STAT1 phosphorylation in different cells. These kinases include the cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (CDK8) [35,36] and casein kinase 2 (CK2) [37,38]. However, our data indicate that CDK8 and CK2 are not responsible for the IFN-induced Ser727 STAT1 phosphorylation and PD-L1 expression in OC cells, since CDK8 or CK2 inhibition did not have any impact on STAT1 phosphorylation or PD-L1 expression (data not shown).

The PD-L1 expression is increased in ovarian cancer and correlates with poor prognosis [5,24]. Recent studies have shown that expression of STAT1 is also increased in OC tissues, and correlates with IFNγ levels and with the PD-L1 expression [26,39]. Furthermore, the recent study of Tian et al. has demonstrated increased levels of Tyr701-pSTAT1 and Ser727-pSTAT1 in OC tissues [25]. Our findings show that IFNγ increases STAT1, Tyr701-pSTAT1 and Ser727-pSTAT1 levels in OC cells, resulting in the increased PD-L1 expression. In addition to STAT1, the induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is dependent on JAK1 and IRF1 signaling. Future studies should determine whether the JAK1/STAT1/IRF1 signaling regulates the PD-L1 expression in OC also in vivo, and whether suppression of the JAK1/STAT1/IRF1 pathway inhibits the PD-L1 biological functions.

In summary, our data demonstrate that the IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression in OC cells is regulated by JAK1, STAT1, and IRF1 signaling, indicating that targeting the JAK1/STAT1/IRF1 pathway may provide a leverage to regulate the PD-L1 levels and PD-L1-regulated OC cell functions in ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the NIH CA202775 grant (to IV).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sveta Padmanabhan: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Bijaya Gaire: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Yue Zou: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Mohammad M. Uddin: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Ivana Vancurova: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

References

- [1].Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, et al. , Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation, J. Exp. Med 192 (7) (2000) 1027–1034, 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N, Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99 (19) (2002) 12293–12297, 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, et al. , Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion, Nat. Med 8 (8) (2002) 793–800, 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Keir ME, Liang SC, Guleria I, Latchman YE, Qipo A, Albacker LA, et al. , Tissue expression of PD-L1 mediates peripheral T cell tolerance, J. Exp. Med 203 (4) (2006) 883–895, 10.1084/jem.20051776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, Okazaki T, Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. , Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8 + T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sd. U. S. A 104 (9) (2007) 3360–3365, 10.1073/pnas.0611533104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clark CA, Gupta HB, Sareddy G, Pandeswara S, Lao S, Yuan B, et al. , Tumorintrinsic PD-L1 signals regulate cell growth, pathogenesis, and autophagy in ovarian cancer and melanoma, Cancer Res. 76 (23) (2016) 6964–6974, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kornepati A, Vadlamudi RK, Curiel TJ, Programmed death ligand 1 signals in cancer cells, Nat. Rev. Cancer 22 (3) (2022) 174–189, 10.1038/s41568-021-00431-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Konishi I, Immune checkpoint inhibition in ovarian cancer, Int. Immunol 28 (7) (2016) 339–348, 10.1093/intimm/dxw020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zuo Y, Zheng W, Liu J, Tang Q, Wang SS, Yang XS, MiR-34a-5p/PD-L1 axis regulates cisplatin chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells, Neoplasma 67 (1) (2020) 93–101, 10.4149/neo_2019_190202N106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sun C, Mezzadra R, Schumacher TN, Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint, Immunity 48 (3) (2018) 434–452, 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Abiko K, Matsumura N, Hamanishi J, Horikawa N, Murakami R Yamaguchi K, et al. , IFN-γ from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and promotes progression of ovarian cancer, Br. J. Cancer 112 (9) (2015) 1501–1509, 10.1038/bjc.2015.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Castro F, Cardoso AP, RM. Gonçalves, K. Serre, M.J. Oliveira, Interferon-gamma at the crossroads of tumor immune surveillance or evasion, Front. Immunol 9 (2018) 847, 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Levy DE, Darnell JE Jr, Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 3 (9) (2002) 651–662, 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA, Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions, J. Leukoc. Biol 75 (2) (2004) 163–189, 10.1189/j1b.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stark GR, Darnell JE Jr, The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty, Immunity 36 (4) (2012) 503–514, 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE Jr, Maximal activation of transcription by STAT1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation, Cell 82 (2) (1995) 241–250, 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Varinou L, Ramsauer K, Karaghiosoff M, Kolbe T, Pfeffer K, Müller M, Decker T, Phosphorylation of the STAT1 transactivation domain is required for full-fledged IFN-gamma-dependent innate immunity, Immunity 19 (6) (2003) 793–802, 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Garda-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, Saco J, Escuin-Ordinas H, et al. , Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression, Cell Rep. 19 (6) (2017) 1189–1201, 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].LB Ivashkiv, IFNγ: signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy, Nat. Rev. Immunol 18 (9) (2018) 545–558, 10.1038/s41577-018-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zou Y, Uddin MM, Padmanabhan S, Zhu Y, Bu P, Vancura A, Vancurova L, The proto-oncogene Bcl3 induces immune checkpoint PD-L1 expression, mediating proliferation of ovarian cancer cells, J. Biol. Chem 293 (40) (2018) 15483–15496, 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gaire B, MM Uddin, Zou Y, Vancurova I, Analysis of IFNγ-induced migration of ovarian cancer cells, Methods Mol. Biol 2108 (2020) 101–106, 10.1007/978-1-0716-0247-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zou Y, Padmanabhan S, Vancurova I, Analysis of PD-L1 transcriptional regulation in ovarian cancer cells by chromatin immunopredpitation, Methods Mol. Biol 2108 (2020) 229–239, 10.1007/978-l-0716-0247-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Padmanabhan S, Zou Y, Vancurova I, Flow cytometry analysis of surface PD-L1 expression induced by IFNγ and romidepsin in ovarian cancer cells, Methods Mol. Biol 2108 (2020) 221–228, 10.1007/978-l-0716-0247-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Abiko K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Yoshioka Y, Matsumura N, Baba T, et al. , PD-L1 on tumor cells is induced in asdtes and promotes peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer through CTL dysfunction, din. Cancer Res 19 (6) (2013) 1363–1374, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tian X, Guan W, Zhang L, Sun W, Zhou D, Lin Q, et al. , Physical interaction of STAT1 isoforms with TGF-β receptors leads to functional crosstalk between two signaling pathways in epithelial ovarian cancer, J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res 37 (1) (2018) 103, 10.1186/s13046-018-0773-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu F, Liu J, Zhang J, Shi J, Gui L, Xu G, Expression of STAT1 is positively correlated with PD-L1 in human ovarian cancer, Cancer Biol. Ther 21 (10) (2020) 963–971, 10.1080/15384047.2020.1824479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Murtas D, Maric D, De Giorgi V, Reinboth J, Worschech A, et al. , IRF-1 responsiveness to IFN-γ predicts different cancer immune phenotypes, Br. J. Cancer 109 (1) (2013) 76–82, 10.1038/bjc.2013.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Burke F, Smith PD, R Crompton M, Upton C, Balkwill FR, Cytotoxic response of ovarian cancer cell lines to IFN-gamma is associated with sustained induction of IRF-1 and p21 mRNA, Br. J. Cancer 80 (8) (1999) 1236–1244, 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wall L, Burke F, Barton C, Smyth J, Balkwill F, IFN-gamma induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells in vivo and in vitro, Clin. Cancer Res 9 (7) (2003) 2487–2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gao AH, Hu YR, Zhu WP, IFN-γ inhibits ovarian cancer progression via SOCS1/JAK/STAT signaling pathway, din. Transl. Oncol 24 (1) (2022) 57–65, 10.1007/s12094-021-02668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sheng Q, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Ding J, Song Y, Zhao W, Cisplatin-mediated down-regulation of miR-145 contributes to up-regulation of PD-L1 via the c-Myc transcription factor in cisplatin-resistant ovarian carcinoma cells, din. Exp. Immunol 200 (1) (2020) 45–52, 10.1111/cei.13406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chatterjee-Kishore M, Wright KL, Ting JP, R Stark G, How Stat1 mediates constitutive gene expression: a complex of unphosphorylated Stat1 and IRF1 supports transcription of the LMP2 gene, EMBO J. 19 (15) (2000) 4111–4122, 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Khodarev NN, Roizman B, Weichselbaum RR, Molecular pathways: interferon/STAT1 pathway: role in the tumor resistance to genotoxic stress and aggressive growth, Clin. Cancer Res. 18 (11) (2012) 3015–3021, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Stronach EA, Alfraidi A, Rama N, Datler C, Studd JB, Agarwal R, Guney TG, et al. , HDAC4-regulated STAT1 activation mediates platinum resistance in ovarian cancer, Cancer Res. 71 (13) (2011) 4412–4422, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bancerek J, Poss ZC, Steinparzer I, Sedlyarov V, Pfaffenwimmer T, Mikulic I, et al. , CDK8 kinase phosphorylates transcription factor STAT1 to selectively regulate the interferon response, Immunity 38 (2) (2013) 250–262, 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Putz EM, Gotthardt D, Hoermann G, Csiszar A, Wirth S, Berger A, Straka E, et al. , CDK8-mediated STAT1-S727 phosphorylation restrains NK cell cytotoxidty and tumor surveillance, Cell Rep. 4 (3) (2013) 437–444, 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Timofeeva OA, Plisov S, Evseev AA, Peng S, Jose-Kampfher M, Lovvorn HN, et al. , Serine-phosphorylated STAT1 is a prosurvival factor in Wilms’ tumor pathogenesis, Oncogene 25 (58) (2006) 7555–7564, 10.1038/sj.onc.1209742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zeng X, Baba T, Hamanishi J, Matsumura N, Kharma B, Mise Y, et al. , Phosphorylation of STAT1 serine 727 enhances platinum resistance in uterine serous carcinoma, Int. J. Cancer 145 (6) (2019) 1635–1647, 10.1002/ijc.32501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li Y, Wang J, Wang F, Gao C, Cao Y, Wang J, Identification of specific cell subpopulations and marker genes in ovarian cancer using single-cell RNA sequencing, Biomed. Res. Int 2021 (2021) 1005793, 10.1155/2021/1005793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]