Abstract

Alkene amino(hetero)arylation presents a highly efficient and straightforward strategy for direct installation of amino groups and heteroaryl rings across a double bond simultaneously. An extensive array of practical transformations has been developed via alkene difunctionalization approach to access a broad range of medicinally valuable (hetero)arylethylamine motifs. This review presents recent progress in 1,2-amino(hetero)arylation of alkenes organized in three different modes. First, intramolecular transformations employing C, N-tethered alkenes will be introduced. Next, two-component reactions will be discussed with different combination of precursors, N-tethered alkenes and external aryl precursor, C-tethered alkenes and external amine precursor, or C, N-tethered reagents, and alkenes. Last, three-component intermolecular amino(hetero)arylation reactions will be covered.

Keywords: alkenes, difunctionalization, amination, (hetero)arylation, (hetero)arylethylamine, catalysis

Graphical Abstract

This review presents recent progress in 1,2-amino(hetero)arylation of alkenes that have been achieved by transition metal catalysis, photocatalysis, or non-catalytic systems. These methods provide rapid access to a diverse range of (hetero)arylethylamine-containing skeletons and will find wide use in organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry.

1. Introduction

Alkene difunctionalization represents a powerful transformation that can introduce two distinct functional groups across carbon-carbon double bonds in one step.[1] This strategy allows for rapid increase in structural diversity and complexity using readily accessible alkenes as attractive precursors. Particularly highly demanded is the synthesis of nitrogen-containing molecules, one of the most widely present classes in pharmaceuticals and natural products. According to the reported top 200 pharmaceuticals by retail sale in 2020, more than half contain at least one C–N bond.[2] To meet this high demand, extensive efforts have been devoted to the development of alkene amination functionalization reactions, such as diamination, aminooxygenation, aminohalogenation, and aminocarbonation.[3]

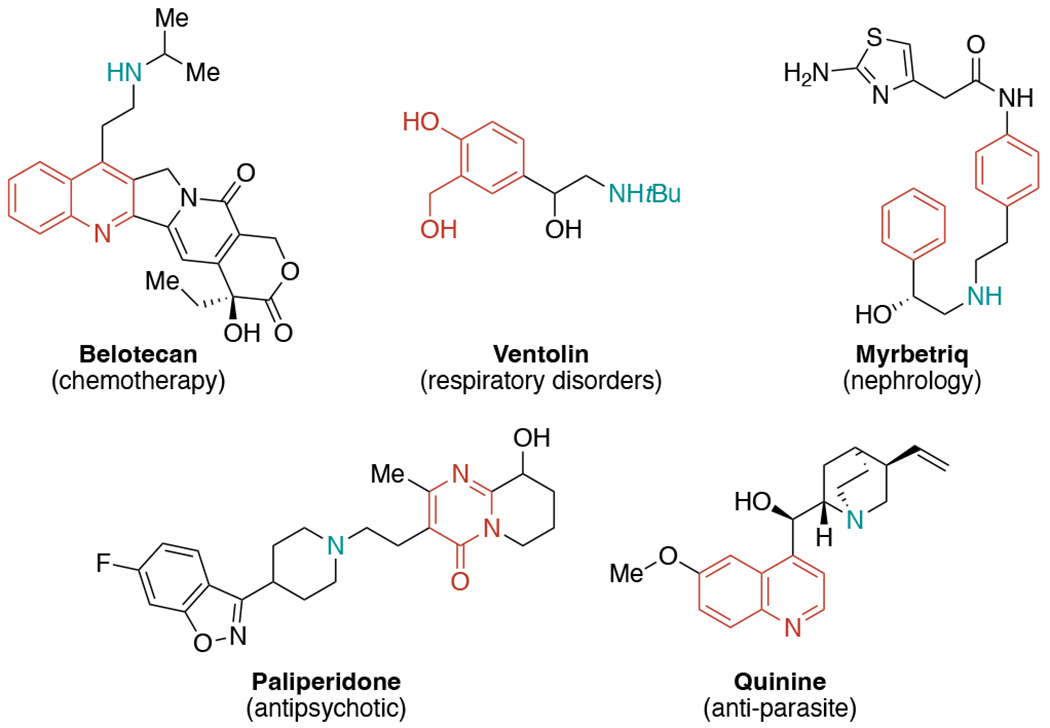

The (hetero)arylethylamine core, as a privileged and biologically relevant motif, is found widely in bioactive molecules and pharmaceuticals, including FDA-approved drugs (Figure 1).[4] Driven by medicinal significance of (hetero)arylethylamine unit, substantial progress in alkene amino(hetero)arylation has been witnessed during the last few decades, namely the development of a series of methods for the installation of both nitrogen and aryl groups onto alkenes. These encompass utilization of different amine and aryl sources with altered regioselectivity under various conditions engaging transition metals, photocatalysis, or non-catalytic systems to provide an array of amino(hetero)aryl skeletons.

Figure 1.

Pharmaceutical products containing (hetero)arylethylamine moieties.

This review will present recent advances of 1,2-amino(hetero)arylation of alkenes categorized by 1) intramolecular transformations employing C,N-tethered alkenes, 2) two-component reactions between N-tethered alkenes and external aryl precursors, C-tethered alkenes and external amine precursors, or C,N-tethered reagents and alkenes, and 3) three-component intermolecular reactions.

2. Amino(hetero)arylation of both C,N-tethered alkenes

2.1. Amino(hetero)arylation by radical aryl migration

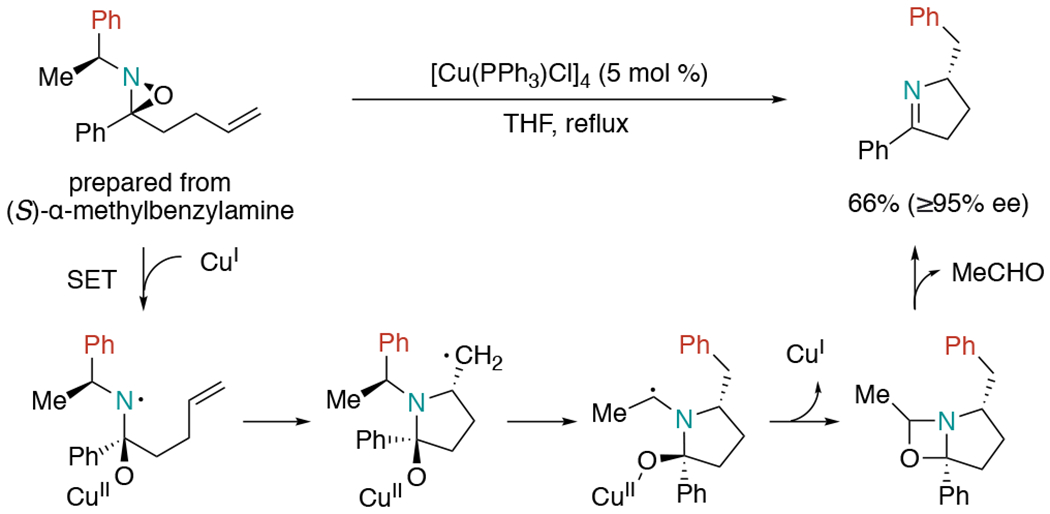

In 1992, the Aubé group reported a copper-catalyzed aminoarylation reaction of an oxaziridines-tethered alkene (Scheme 1).[5] Mechanistically, the authors proposed single-electron transfer (SET) to oxaziridine, which provided an amino radical and alkoxide pair. Following the radical aminocyclization, the resulting carbon radical would undergo a 1,4-aryl migration. Upon the loss of acetaldehyde, Cu(I) catalyst was regenerated along with the formation of pyrroline products. Note that this formal aminoarylation reaction proceeded with high diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 1.

Copper(I)-promoted aminoarylation of oxaziridine-tethered alkenes.

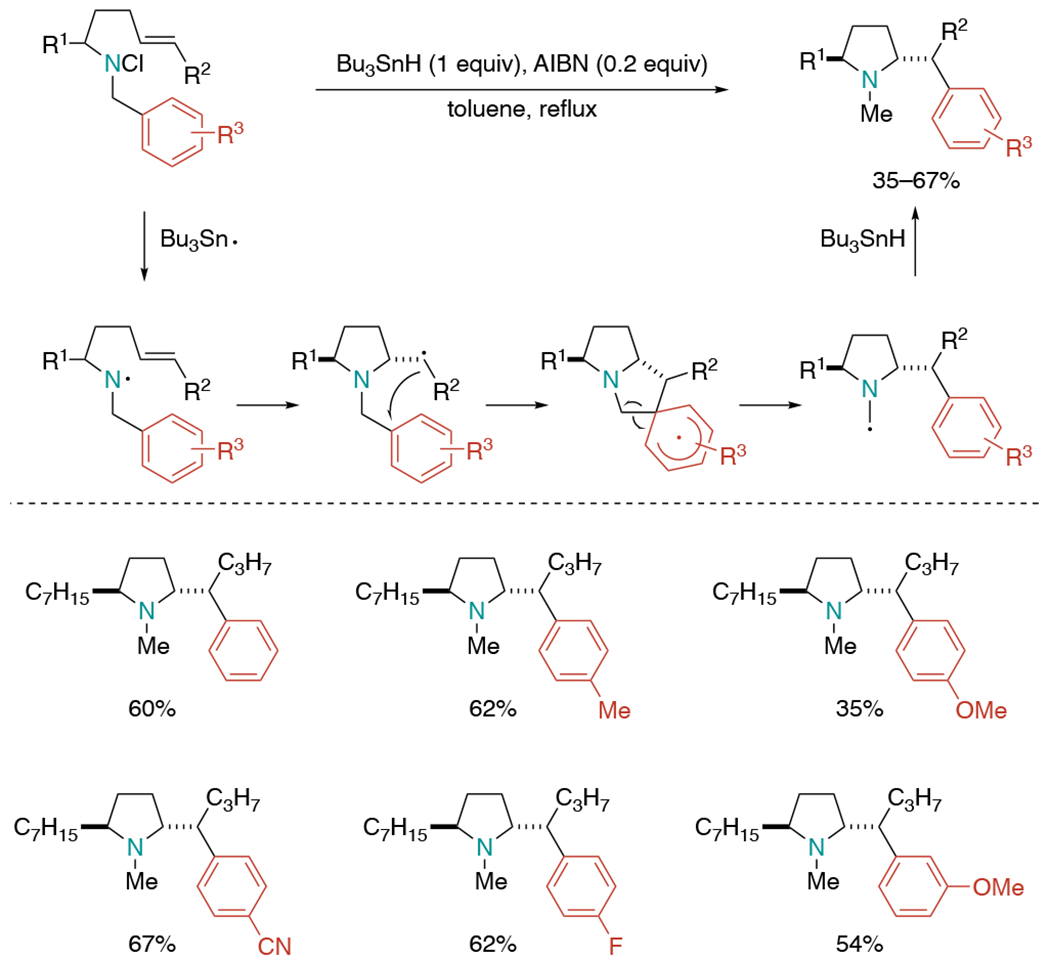

The Tokuda laboratory reported a related tandem radical reaction of N-benzyl chloramines (Scheme 2).[6] The aminyl radical were generated from N-benzyl-N-chloroalk-4-enylamines in the presence of Bu3SnH and AIBN and were proposed to undergo 5-exo cyclization followed by aryl migration to give pyrrolidines as a single stereoisomer. The substituted aryls with different electronic effects provided aryl migration products in 35–67% yields. The reaction of terminal alkenes showed less efficient migratory aptitude of aryl groups, demonstrating the critical role of the substituents at the terminal carbon of the double bond.

Scheme 2.

Stereoselective cyclization of N-benzylalk-4-enylaminyl radicals followed by 1,4-aryl migration.

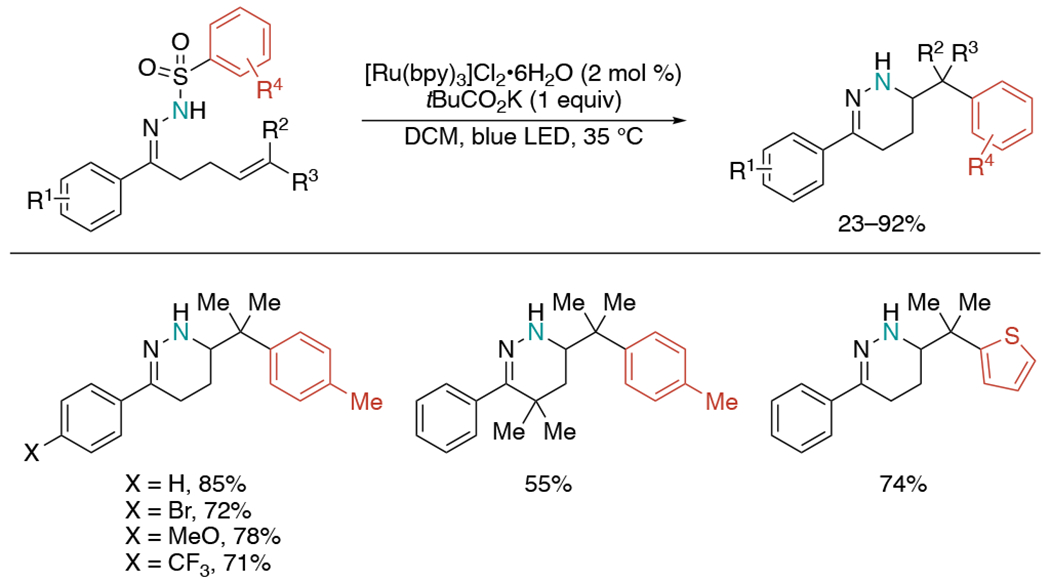

In 2021, the Liu group demonstrated a photoredox-neutral alkene aminoarylation for the synthesis of 1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyridazines (Scheme 3).[7] This reaction features a cascade of hydrazonyl radical cyclization and Smiles–Truce aryl transfer. The substrate scope of the reaction is quite broad with good functional group compatibility including thiophene as a viable migration agent to give the desired heteroarylethylamine product.

Scheme 3.

Visible light-mediated intramolecular aminoarylation of hydrazones with a pendant alkene.

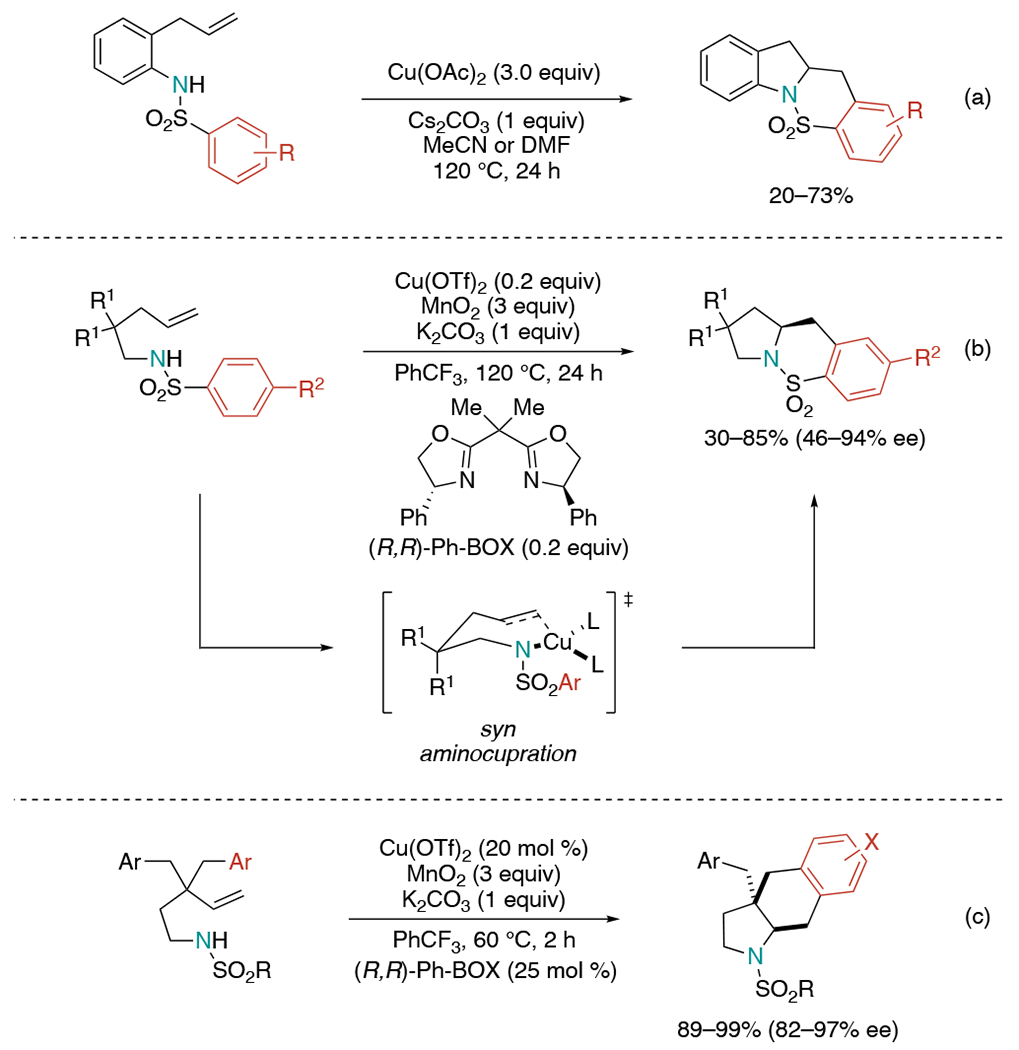

2.2. Annulative amino(hetero)arylation

In 2004, the Chemler group accomplished an oxidative cyclization of arylsulfonyl-o-allylanilines using excess Cu(OAc)2 as an oxidant (Scheme 4, a).[8] The yield and selectivity differed noticeably depending on the electronic nature of the aryl substituent. In general, electron-rich arylsulfonyl substrates gave good yields. The reaction with meta-substituted aryl sulfonamide led to mixture of regioisomers.

Scheme 4.

Copper-catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes via oxidative cyclization.

Later in 2007, Chemler developed a related protocol in an enantioselective manner (Scheme 4, b).[9] They revealed the stereochemistry-determining C–N bond-forming step occurred via syn-aminocupration of the alkene.[10] Based on this finding, they hypothesized that the involvement of copper salt in the stereochemistry determining step could allow a stereo-controlled synthesis of the product by using chiral ligands. Condition screening showed the highest conversion with MnO2 (3 equiv) as an appropriate oxidant for copper turnover and the highest asymmetric induction with (R,R)-Ph-BOX as a chiral ligand. Overall, desired products were obtained in 30–85% yields and 46–94% ee. In 2010, this method was extended to the synthesis of hexahydro-1H-benz[f]indole (Scheme 4c).[11] Various arylsulfonyl substrates afforded desired products with high enantioselectivity up to 97% ee without sultam regioisomers. When the aryl substrate contained a substituent at the meta position, a mixture of ortho and para benz[f]indole regioisomers was observed.

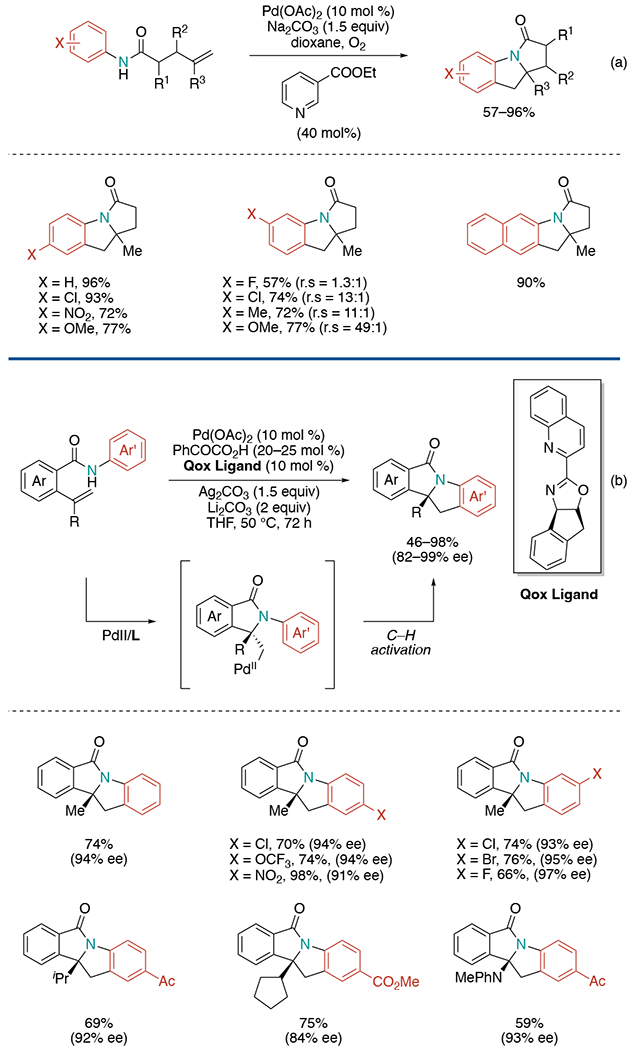

In 2011, the Yang laboratory demonstrated a Pd(II)-catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes (Scheme 5, a).[12] This oxidative functionalization of alkenes was achieved by using oxygen as the sole oxidant, different from previous methods requiring either stoichiometric external oxidants or preactivated reactants to complete catalytic turnover. They proposed a reaction pathway proceeding a Pd(0)/Pd(II) system instead of Pd(II)/Pd(IV). High reaction conversion was observed with a stoichiometric amount of Pd(OAc)2 under an argon atmosphere, supporting their proposal. Additionally, cyclization of a monosubstituted alkene led to the enamide via a midway β-hydride elimination, which ruled out the possibility of a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic manifold. On the meta-substituted anilide system, a mixture of regioisomers was formed.

Scheme 5.

Pd(II)-catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes.

In 2017, Liu and co-workers developed an asymmetric Pd-catalyzed intramolecular oxidative aminoarylation of alkenes (Scheme 5, b).[13] Inspired by previous literatures on C–H activation, they envisaged that if a chiral alkyl-Pd(II) intermediate generated in situ could undergo C–H activation, it would be possible to deliver optically pure polycyclic heterocycles. Through extensive condition screening, they found a chiral quinoline–oxazoline (Qox) ligand with Ag2CO3 as an oxidant could significantly increase yields. Furthermore, it was discovered that the addition of a catalytic amount of phenylglyoxylic acid is crucial to accelerate the key aminopalladation step and has a beneficial effect on enantioselectivity. The reaction exhibits a broad substrate scope of various substituted anilines and alkenes but was limited to terminal alkenes since internal alkenes gave aza-Wacker products.

3. Two-component amino(hetero)arylation

3.1. Amino(hetero)arylation of N-tethered alkenes

3.1.1. Alkene tethered amides/sulfonamides

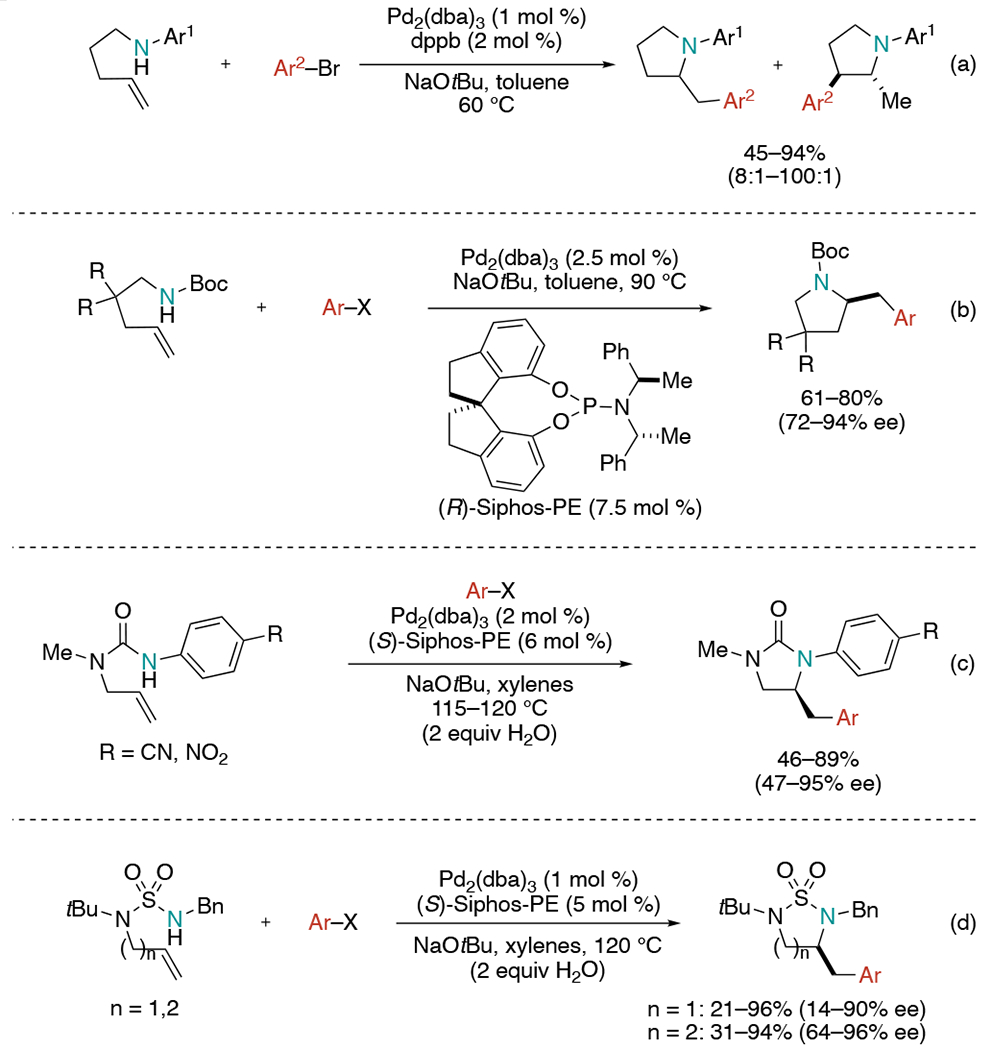

Pd-catalyzed aminoarylation of N-tethered alkenes has been extensively studied, particularly pioneered by the Wolfe group.[14] In 2004, Wolfe et al. demonstrated the first example of a catalytic chemoselective intramolecular insertion of alkenes into a palladium(aryl)(amido) complex (Scheme 6, a).[15] The reaction of γ-aminoalkene substrates with N-aryl substituents provided desired N-aryl 2-(β-naphthylmethyl) pyrrolidine with regioisomer up to >100:1 ratio. The coupling between N-aryl amines with a wide range of aryl bromide partners proceeded in 45–94% yields. Later, harsh NaOtBu was substituted with weaker bases (Cs2CO3 or K3PO4), allowing sensitive functional groups to be tolerated, including enolizable ketones, nitro groups, methyl esters, acetates, and aldehydes.[16]

Scheme 6.

Pd-catalyzed aminoarylation of alkenes by the Wolfe group.

In 2010, Wolfe extended this work, detailing the first enantioselective Pd-catalyzed aminoarylation of amine-tethered alkenes (Scheme 6, b).[17] The reaction between N-(boc)-pent-4-enylamine, aryl halide with Pd2(dba)3 as a precatalyst, and (R)-Siphos-PE as a chiral ligand in the presence of base delivered 61–80% of the products in 72–94% ee. Although Siphos-PE ligand has different steric and electronic properties than other phosphine ligands such as dpe-phos, dppf, and xantphos, which were used in the racemic pyrrolidine generation, the study of a deuterated alkene suggested that the Pd/Siphos-PE-catalyzed reactions also undergoes syn-aminopalladation pathway. The high enantioselectivities derived from this ligand may results from steric bulk and chiral elements on both the amine group and the diol portion. The enantioselective synthesis of (−)-tylophorine was successfully achieved by using this carboamination method.[18]

Another related work was described on the synthesis of enantiomerically enriched imidazolin-2-ones through asymmetric Pd-catalyzed alkene aminocarbonation reactions (Scheme 6, c).[19] While (R)-Siphos-PE only afforded modest enantioselectivity for this reaction, (S)-Siphos-PE was found to be an efficient chiral ligand giving high yields and good enantioselectivities. For better asymmetric induction, the para-substituent on the N-aryl moiety required increased electron-withdrawing ability (X = CN, NO2). In some cases, the addition of water resulted in significantly improved and reproducible enantioselectivities.

This Pd-mediated alkene aminocarbonation strategy was also expanded to address the synthesis of cyclic sulfamides (Scheme 6, d).[20] Coupling between aryl halide and N-(homo)allylsulfamides produces five- or six-membered cyclic sulfamides. Mechanistic studies done with deuterated substrates reveal the major stereoisomers result from syn-addition of nitrogens and aryl groups to the alkenes, supporting the syn-aminopalladation pathway. However, electron-poor aryl halides decreased both diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity likely due to competing anti-aminopalladation pathway.

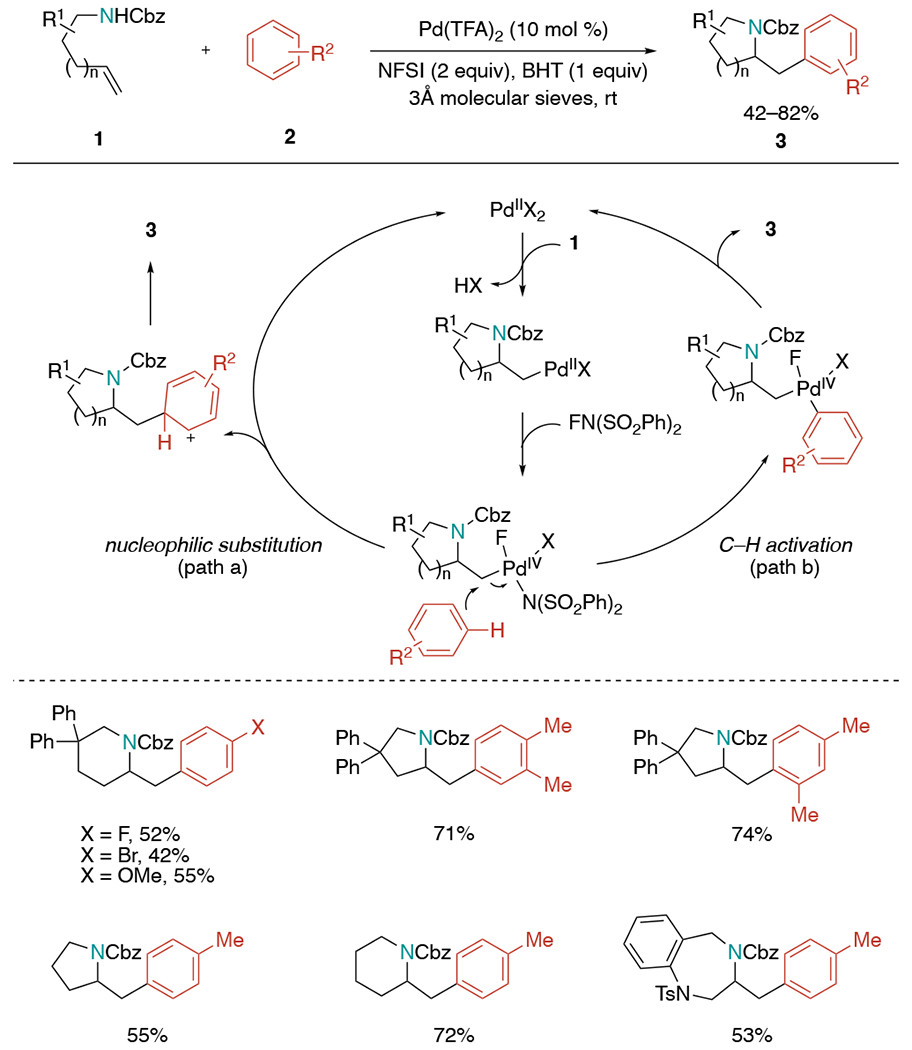

The Michael group developed a palladium-catalyzed oxidative aminoarylation of protected aminoalkenes through a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) pathway (Scheme 7).[21] The work was based on their findings in the previous diamination of aminoalkenes with N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide (NFSI) that changing the solvent from EtOAc to toluene gave a noticeable amount of aminocarbonation byproduct resulting from incorporation of toluene.[22] The transformation was initiated by anti-aminopalladation of the alkene, forming a Pd(II)–alkyl complex.[23] Subsequent oxidative addition of NFSI generates the key Pd(IV) complex, and this intermediate may undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution to form the aminoarylation product (path a). Alternatively, C–H activation of the aryl group followed by reductive elimination to the final product is also possible (path b). This method produced a variety of synthetically useful five-, six-, and seven-membered nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Additionally, no directing group was needed for arylation to occur in a high regioselective manner.

Scheme 7.

Pd(II)/Pd(IV)-catalyzed aminoarylation of alkenes utilizing NSFI.

In 2010, the Toste group disclosed a gold-catalyzed aminoarylation of alkenes and arylboronic acids (Scheme 8).[24] Ligand and halide effects were crucial for the efficiency of this protocol under mild reaction conditions. The reaction is initiated by oxidation of Au(I) to Au(III) with Selectfluor. Mechanistic studies suggested this oxidation step precedes the aminoauration step. Moreover, the C–C bond formation is suggested to occur through bimolecular reductive elimination rather than traditional reductive elimination following transmetalation of boronic acid. In this hypothesis, the B–F interaction has a vital role in the reductive elimination step, as it increases the nucleophilicity of the boronic acid and the electrophilicity of the alkyl–gold(III) complex. In the same year, the Zhang group published an analogous gold-catalyzed alkene oxy- and aminoarylation paper using Ph3PAuCl as a catalyst.[25]

Scheme 8.

Gold-catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation via bimolecular reductive elimination.

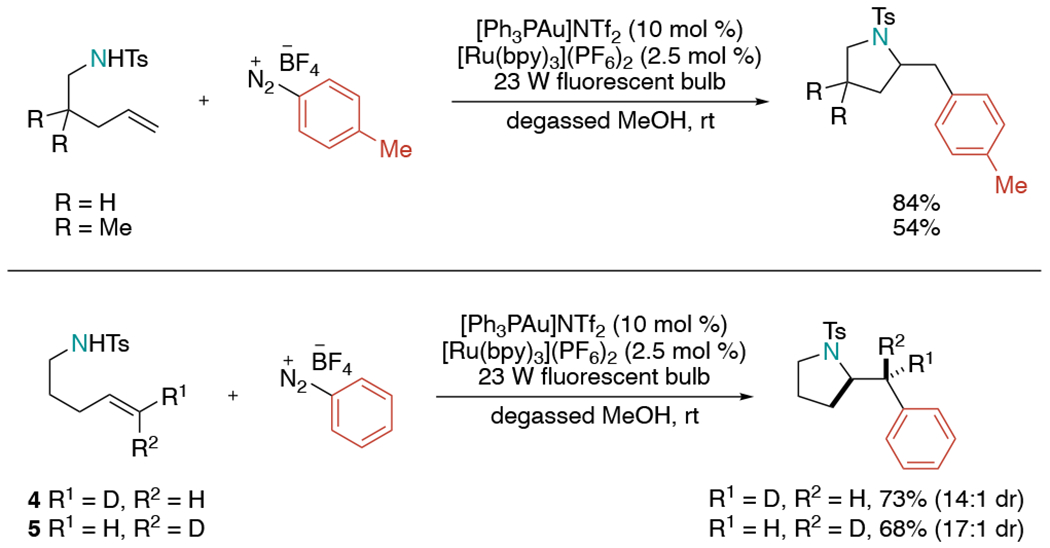

In 2013, a novel gold/photoredox dual-catalyzed platform was realized using nitrogen-tethered alkenes and aryldiazonium salts to achieve 1,2-oxy- and aminoarylation by Glorius and co-workers (Scheme 9).[26] They proposed aryl radicals would be generated via photocatalysis and would oxidize Au(I) to Au(II). When the visible light was turned off, the reaction stopped producing product, implying that the Au and photoredox catalyst operate in tandem throughout the course of the reaction. Reactions with E/Z deuterated alkenes 4 and 5 proceeded in a high diastereoselective fashion with overall trans-addition products. This result supports that the reaction mechanism involves trans-aminoauration initially followed by oxidative arylation with retention of stereochemistry. Although the study presented a wide substrate scope of oxyarylation, only a few aminoarylation examples were presented.

Scheme 9.

Gold and photoredox dual-catalyzed aminoarylation of alkenes using aryldiazonium salts.

In 2020, the Bourissou group published a Au(I)/Au(III) catalyzed aminoarylation of alkenes in the presence of silver salts and hemilabile P,N-bidentate ligands (Scheme 10).[27] This work was the first gold-catalyzed reaction combining oxidative addition of aryl iodide and π-activation of alkenes. The (P,N) gold complex efficiently installed electron-rich aryl substrates onto alkenes, which had previously been challenging. The mechanism of this reaction was proposed to proceed via an outer-sphere pathway based on the formation of trans-addition products, but small amounts of the cis-addition products implied the migratory insertion pathway may also exist.

Scheme 10.

Gold-catalyzed aminoarylation involving oxidative addition and π-activation of alkenes.

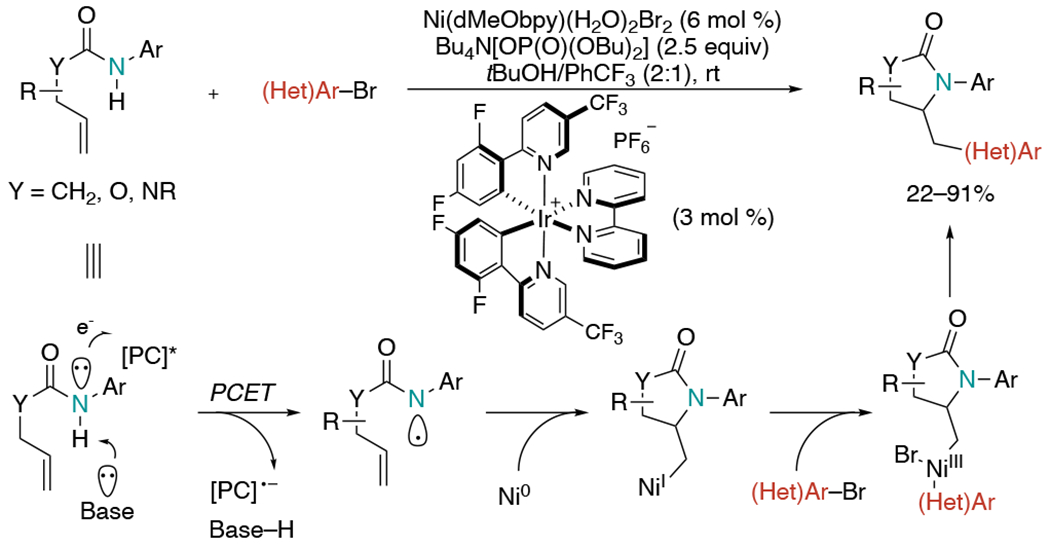

In 2019, the Molander group reported a Ni-catalyzed amidoarylation of alkenes via photoredox proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) (Scheme 11).[28] Reactions between non-functionalized amides and (hetero)aryl bromides provided an array of complex molecules containing a valuable pyrrolidinone core. The authors proposed a mechanism initiated by the formation of an amidyl radical via PCET which was assisted by hydrogen bonding with a superstoichiometric phosphate base in a concerted pathway. Subsequently, a rapid 5-exo-trig cyclization would generate an alkyl radical, which enters the nickel-catalytic cycle to form a Ni(I)-intermediate. This Ni(I) complex would undergo oxidative addition with aryl halide and the resultant Ni(III) complex would form the desired products through reductive elimination. This protocol showcases a broad scope of alkenyl amides, anilines, and (hetero)aryl halides. The reaction was also applicable to carbamates and ureas.

Scheme 11.

Photoredox PCET involved Ni-catalyzed amidoarylation of unactivated alkenes.

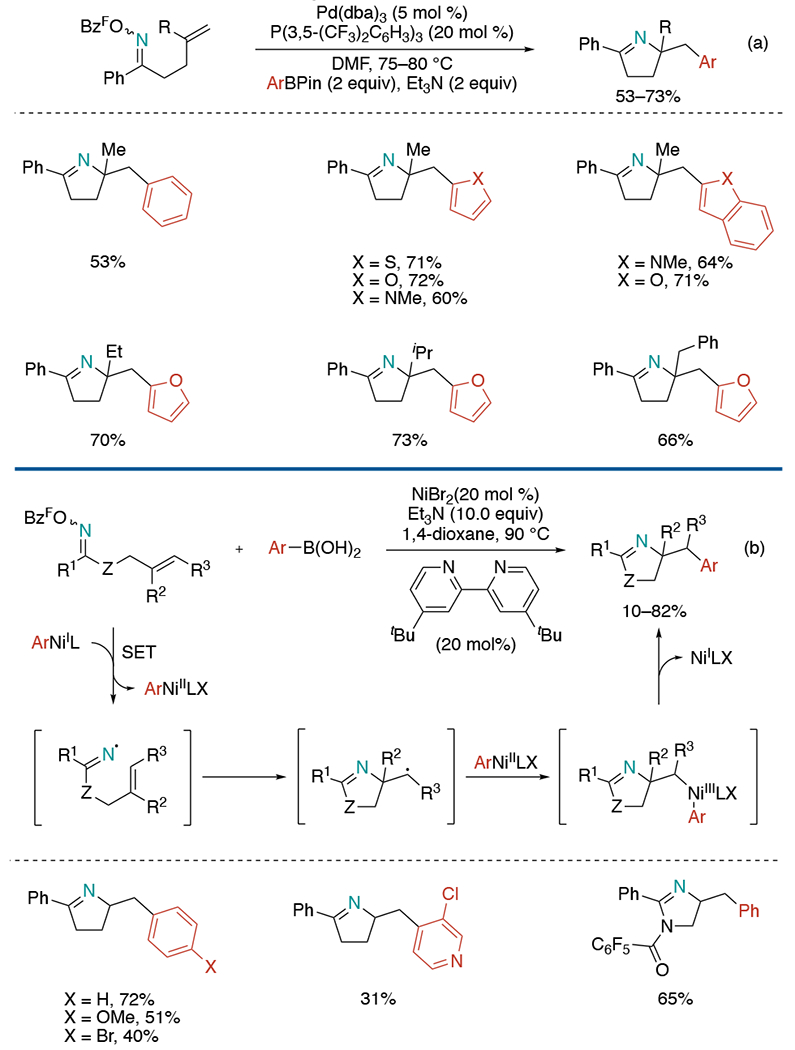

3.1.2. Umpolung strategy using electrophilic amines

In 2015, Bower and co-workers disclosed a Pd-catalyzed unified alkene aminocarbonation including aminoarylation through an umpolung approach (Scheme 12, a).[29] The reaction was initiated by oxidative addition of Pd(0) into the N–O bond of O-pentafluorobenzoyl oxime esters to generate imino-Pd(II) intermediates. Subsequent 5-exo cyclization formed alkyl-Pd(II) complex, and the transmetallation of pinacol arylboronate delivered aminoarylation products. The scope of the reaction is mostly limited to electron-rich arylboronates. The monosubstituted alkenes were not suitable substrates for this aminoarylation reaction since β-hydride elimination overtook the desired reaction pathway.

Scheme 12.

1,2-Aminoarylation of oxime ester-tethered alkenes with organoboron reagents.

Soon afterward, a complementary method using γ,δ-unsaturated oxime ester, and boronic acid as starting materials was released expanding the substrate scope beyond 1,1-disubstituted terminal alkenes (Scheme 12, b).[30] The Selander lab envisioned that nickel catalysis could effectively evade competing β-hydride elimination owing to its higher energy of the vacant d-orbital. Mechanistic studies indicated the involvement of iminyl and carbon-centered radicals. A wide range of arylboronic acids, heteroaromatic boronic acids, various oxime esters participated in the reaction. The protocol was extendable to the synthesis of imidazolines.

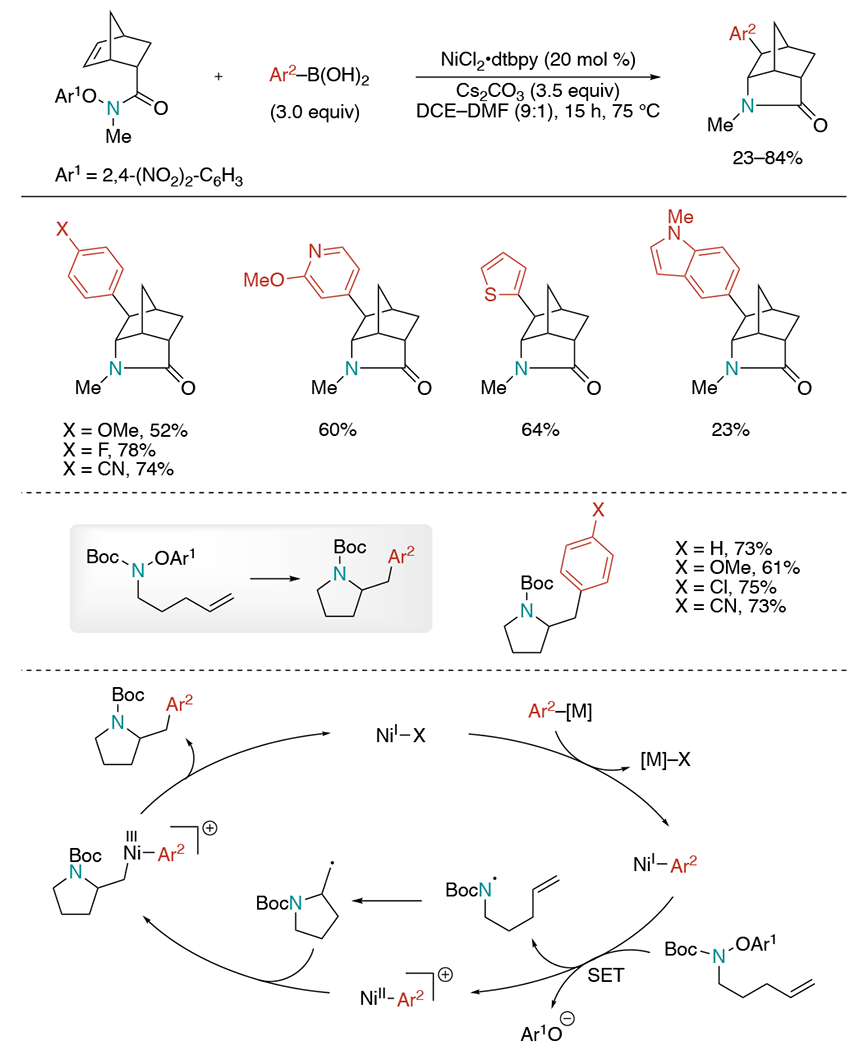

In 2019, Leonori and co-workers developed a Ni-catalyzed aminoarylation with electrophilic N-amidyl radical generated by ground-state SET with aryl-Ni(I) species (Scheme 13).[31] While they were developing direct N-arylation with nucleophilic aminyl radicals, electrophilic amidyl radicals were found to be not efficient coupling partners for aromatic groups. Later, their attempt to utilize amidyl radicals for multicomponent reaction with norbonene-derived oxyamides and aryl boronic acids led to cascade N-cyclization followed by arylation, producing lactam products. In this reaction, various electron-rich, electron-poor aryl, and heteroaryl rings were successfully installed onto alkenes. The protocol is also applicable towards the construction of simple 5-membered ring lactams and α-benzyl-pyrrolidines.

Scheme 13.

Ni-mediated cascade amidoarylation of oxyamide-tethered alkenes.

3.2. Amino(hetero)arylation of C-tethered alkenes

3.2.1. Azido(hetero)arylation

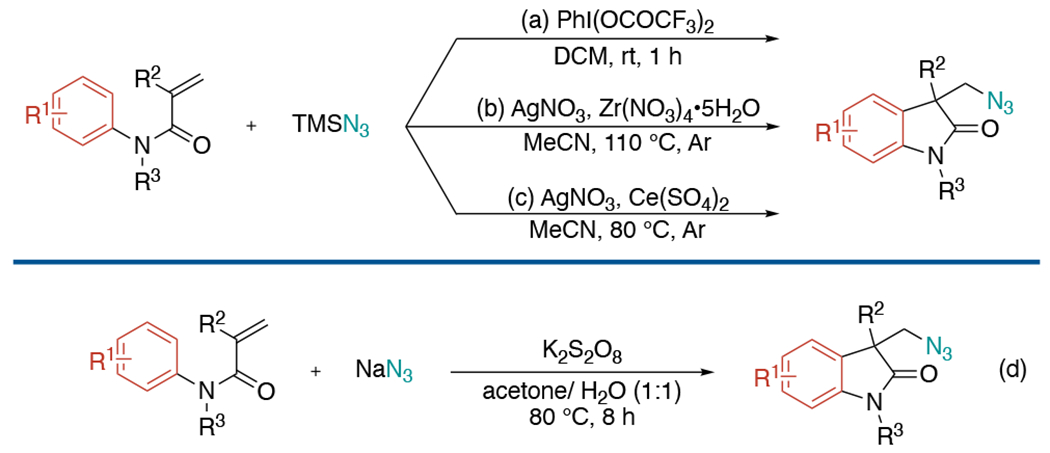

In 2013, three groups independently disclosed azidoarylation of alkenes utilizing N-arylacrylamides and TMSN3 to synthesize various azide 2-oxindoles. The Antonchick laboratory employed hypervalent iodine(III) reagents to produce azidyl radicals, which added to alkenes, followed by trapping with tethered aryl group under metal-free reaction conditions (Scheme 14, a).[32] Both the Yang and the Jiao groups developed silver-mediated azidoarylation of activated alkenes through cascade radical process and C–H functionalization (Scheme 14, b and c).[33]

Scheme 14.

Radical azidoarylation of N-arylacrylamide-tethered alkenes as a rapid access to oxindole synthesis.

Another analogous azidoarylation strategy was reported in the following year by Zhang’s lab (Scheme 14d).[34] In this work, NaN3 was used as the azide source and K2S2O8 as an oxidant in aqueous solution for C–N and C–C bond formation on alkenes.

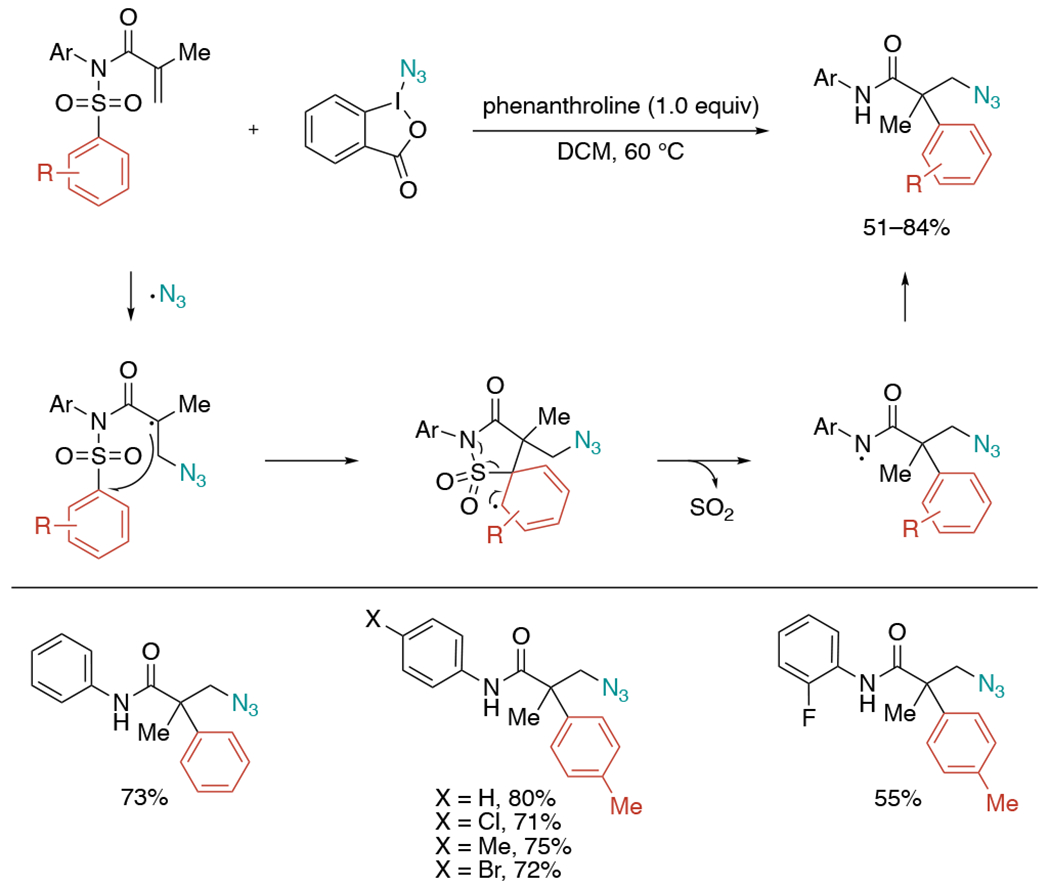

In 2014, Nevado et al. developed azidoarylation of activated alkenes through 1,4-aryl migration (Scheme 15).[35] Zhdankin reagent was used as a nitrogen radical initiator to trigger 5-ipso cyclization, desulfonylation, and 1,4-aryl migration to generate β-aryl-α-azido amides bearing a quaternary stereocenter. The reaction efficiently occurred by simply treating the starting materials with phenanthroline as a base. Generally, the presence of para substituents (X) on the aryl group resulted in the formation of desired products in good yields, but the presence of ortho substituents had a negative impact on the reactivity.

Scheme 15.

Radical-mediated azidoarylation of activated alkenes through 1,4-arylation and desulfonylation.

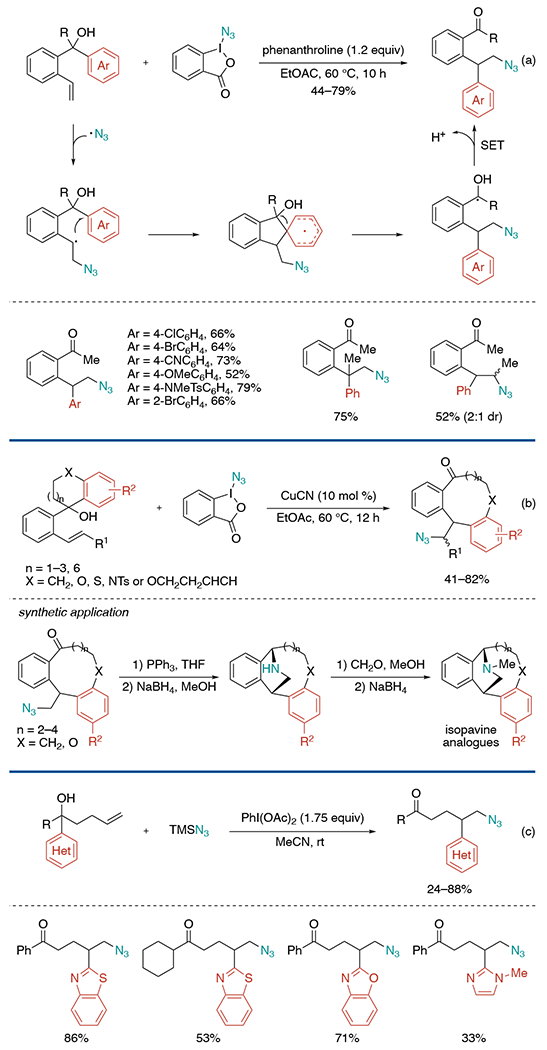

Another alkene azidoarylation work utilizing Zhdankin reagent was published by the Liu group in 2017 (Scheme 16, a).[36] The initial condition screening showed CuCN is an efficient catalyst to suppress undesired 1,2-oxyazidation byproduct and give 1,2-azidorarylation product in good yield. Later, they found that the reaction also proceeds well in the presence of 1,10-phenanthroline (1.2 equiv) without copper catalyst. The reaction is initiated by the addition of azide radicals, generated from azidoiodonane, to alkenes. The alkyl radical intermediate undergoes cyclization by reacting with the ipso-position of the aryl group, followed by 1,4-aryl migration to give the desired product. This migration protocol could be triggered by trifluoromethyl and phosphonyl radicals as well. Furthermore, the Liu group established radical aryl migration from alkenyl alcohols bearing cyclic benzyl alcohol groups to construct entropically and enthalpically unfavorable medium- and medium-bridged rings (Scheme 16, b).[37] An elegant application of this method was demonstrated in the synthesis of novel isopavine analogs.

Scheme 16.

Azido(hetero)arylation of alkenes through distal (hetero)aryl migration.

Soon after, Zhu and co-workers disclosed azidoheteroarylation of unactivated alkenes through distal heteroaryl group migration (Scheme 16, c).[38] The reaction is viable in metal-free condition, using TMSN3 and phenyl iodonium diacetate to generate azide radicals. Several different heteroarenes could be successfully installed onto alkenes, including (benzo)thiazole, benzoxazole, and N-methyl imidazole. However, migration of six-membered azaheteroaryls, such as pyridine, are inefficient in this protocol. While the 1,4-migration of heteroaryl groups proceed smoothly, 1,2-, 1,3- or 1,5-migration results in trace or none of the desired products.

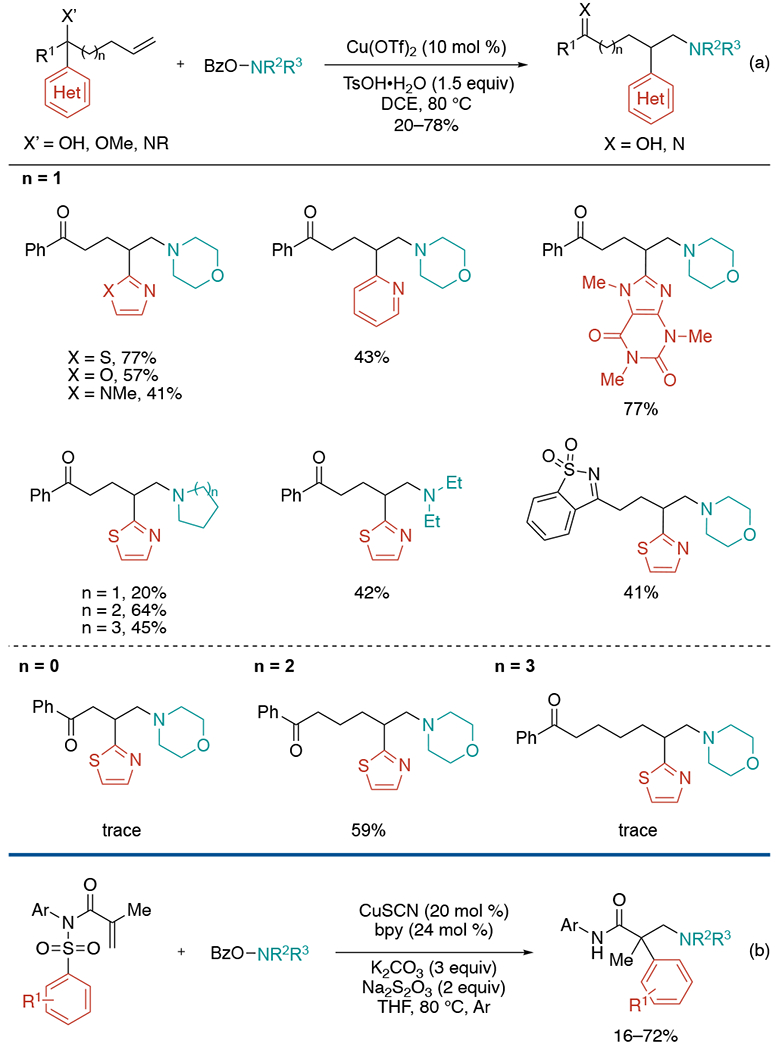

3.2.2. Amino(hetero)arylation installing electron-rich amines

In 2021, the Wang group employed a carbon functional migration strategy to develop copper-catalyzed aminoheteroarylation of alkenes for the synthesis of valuable heteroarylethylamine motifs (Scheme 17).[39] This method features a broad scope of alkenes, heteroarenes, and amines under mild reaction conditions. The reaction is triggered by the addition of N-centered radicals generated from O-benzoylhydroxylamines to alkenes, mediated by the copper catalyst. When morpholine-derived O-benzoylhydroxylamine is used as a model amine precursor, a wide range of heteroaryl groups including various azoles and six-membered N-containing heteroaryl groups provide the desired products. Even structurally complex functional groups, such as caffeine, undergo migration. This strategy is also applicable for installing diverse amines including acyclic and different sized cyclic amines. In addition to 1,4-migrations, the method could also be extended to 1,5-migration, while the reactions via 1,3-and 1,6-migration give the only LC/MS detectable amounts of the products, supporting the involvement of cyclized intermediate in the reaction pathways. Based on the mechanistic hypothesis, this group could expand the strategy to non-alcohol-containing alkenes, which had not been demonstrated in previous similar migration protocols. The Following year, the Liu laboratory also utilized O-benzoylhydroxylamines to enable a copper-catalyzed amino(hetero)arylation under basic condition (Scheme 17, b).[40] The reaction starts from the addition of the N-centered radical generated by O-benzoylhydroxylamines. Following steps proceed through a similar mechanism described in Scheme 15 from Nevado’s work.[35]

Scheme 17.

Copper-catalyzed aminoheteroarylation of alkenes using O-benzoylhydroxylamines.

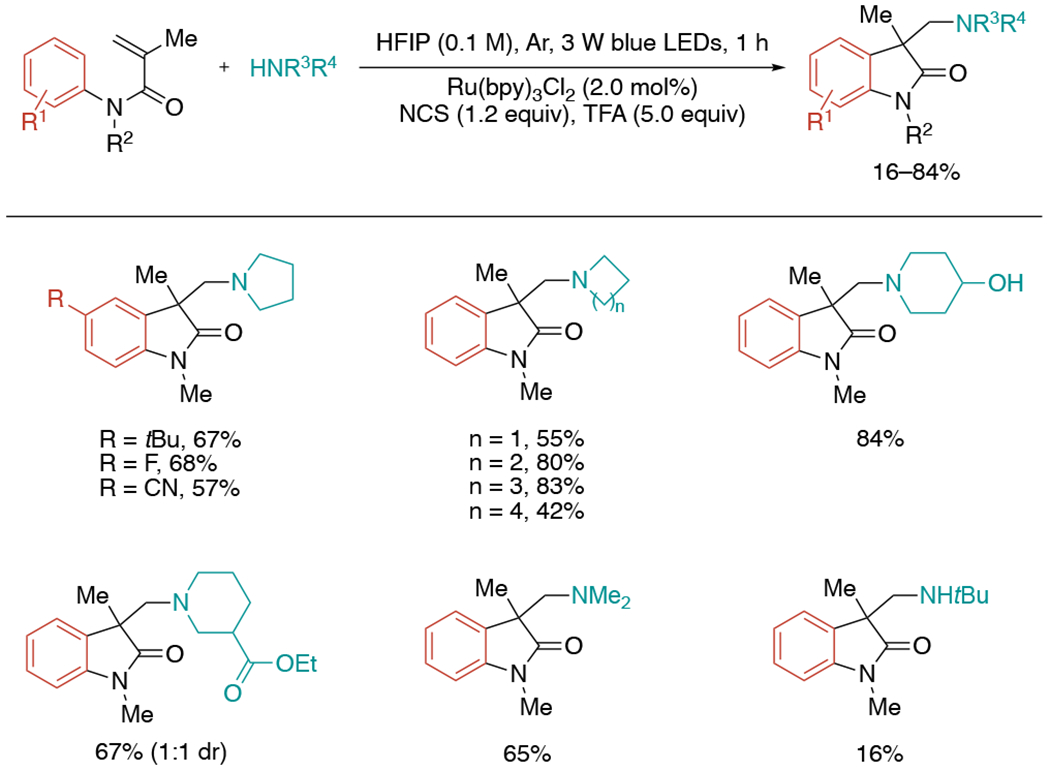

In 2020, Liu et al. published a related visible-light-induced amination of arylacrylamides with alkyl amines, which provided a direct entry to amine-containing oxindole derivatives (Scheme 18).[41] The in situ chlorination of amines by N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) generated N-chloramines, which would undergo reduction by visible light-excited Ru(bpy)3Cl2 to form aminium radicals to promote the radical amination/cyclization cascade. A range of amine scope including different-sized ring, acyclic and primary amines proved to be suitable for the reaction. The alkene scope in this work was limited to 1,1-disubstituted terminal alkenes.

Scheme 18.

Visible-light mediated aminoarylation with in situ generated N–chloroamines.

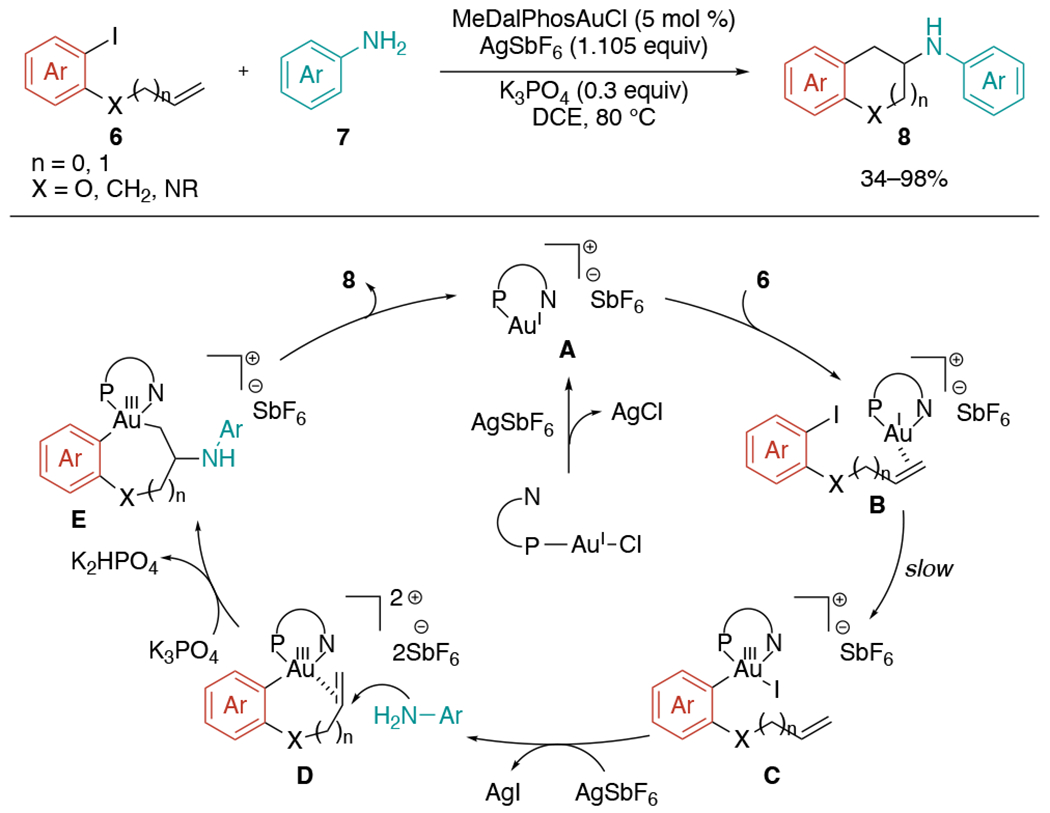

The first example of gold-catalyzed 1,2-aminoarylation of alkenes that utilizes external amine as a nucleophile was reported by the Patil laboratory in 2021 (Scheme 19).[42] This reaction does not require superstoichiometric amount of oxidants, which were necessary to facilitate innately challenging Au(I)/Au(III) redox cycle in previous gold-mediated alkene difunctionalization protocols. Instead, with hemilabile P,N-bidentate ligand (MeDalPhos) and AgSbF6, cationic Au(I) species A is generated and furnishes the Au(I)-π complex B upon addition of aryl halide, which undergoes the key oxidative addition leading to the formation of Au(III) species C. Then, AgSbF6 would abstract iodide to form the coordinatively unsaturated Au(III) species D capable of activating alkenes, followed by nucleophilic attack of aniline to generate E complex. Based on their deuterium labeling experiment, this nucleophile attack is likely to proceed through anti-addition. The subsequent inner sphere reductive elimination of intermediate E affords the desired products. The delicate control of the concentration of K3PO4 was crucial to suppress the competing reaction pathway generating direct C–N cross-coupled products.

Scheme 19.

Gold-catalyzed 1,2-aminoarylation of alkenes with external anilines.

3.2.3. Asymmetric aminoarylation

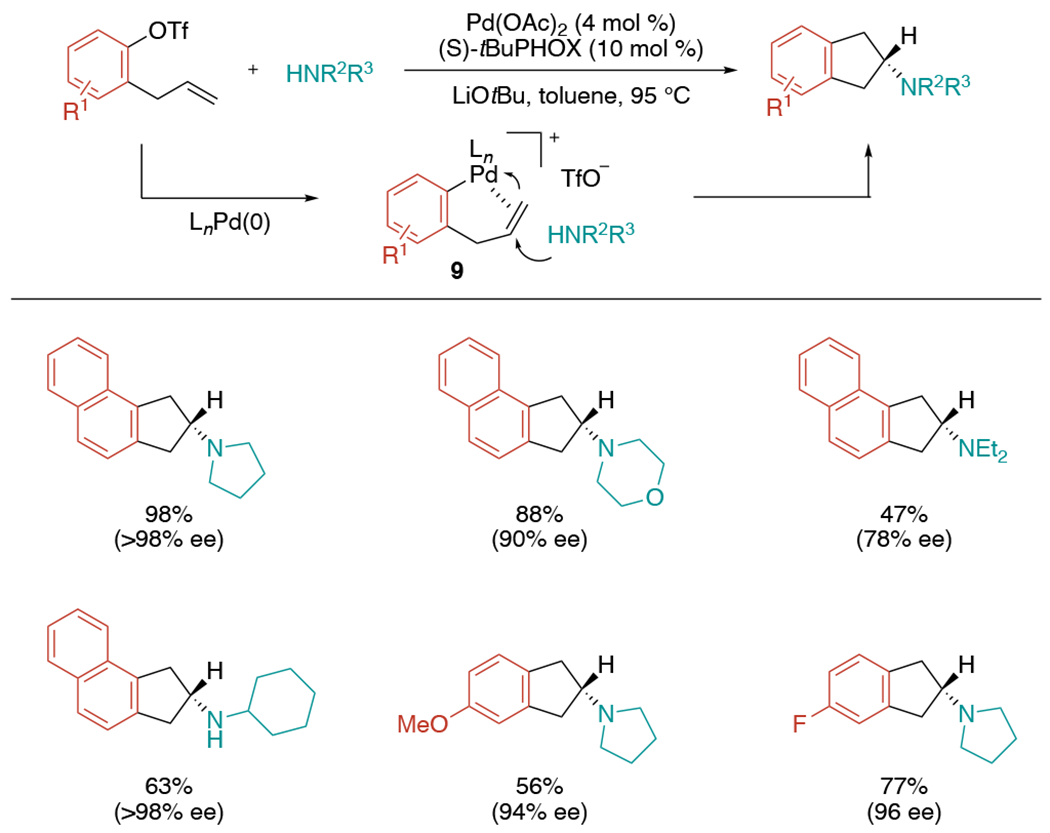

Enantioselective protocols of aminoarylation have been developed. In 2015, the Wolfe group presented the first example of Pd-catalyzed alkene aminoarylation in which a free amine is coupled with an alkene bearing a tethered electrophile to synthesize 2-aminoindanes (Scheme 20).[43] Until then, established Pd-mediated carboamination strategies required reversed coupling partners: the reaction between alkenes bearing pendant nucleophiles with aryl halide/pseudohalide species. They hypothesized that anti-aminopalladation pathway would be desirable for this reaction as the carbocycles are likely generated via endocyclization. During their previous studies on a synthesis of cyclic sulfamides via Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination,[44] they discovered that reaction conditions leading to a more electrophilic metal center could favor anti-aminopalladation.[45] They envisioned that oxidative addition of aryl triflates to Pd(0) followed by alkene coordination would generate 9, which then would undergo intermolecular anti-aminopalladation followed by reductive elimination to give the desired aminoarylation products. After confirming the feasibility of this reaction with aryl triflate and pyrrolidine, they further expanded the protocol to produce chiral aminoindane products using (S)-tert-butylPHOX as a ligand. Various asymmetric aminoindanes could be synthesized in good to excellent yields with high enantioselectivities up to >98% ee.

Scheme 20.

Asymmetric Pd-catalyzed alkene aminoarylation reactions through intermolecular anti-aminopalladation.

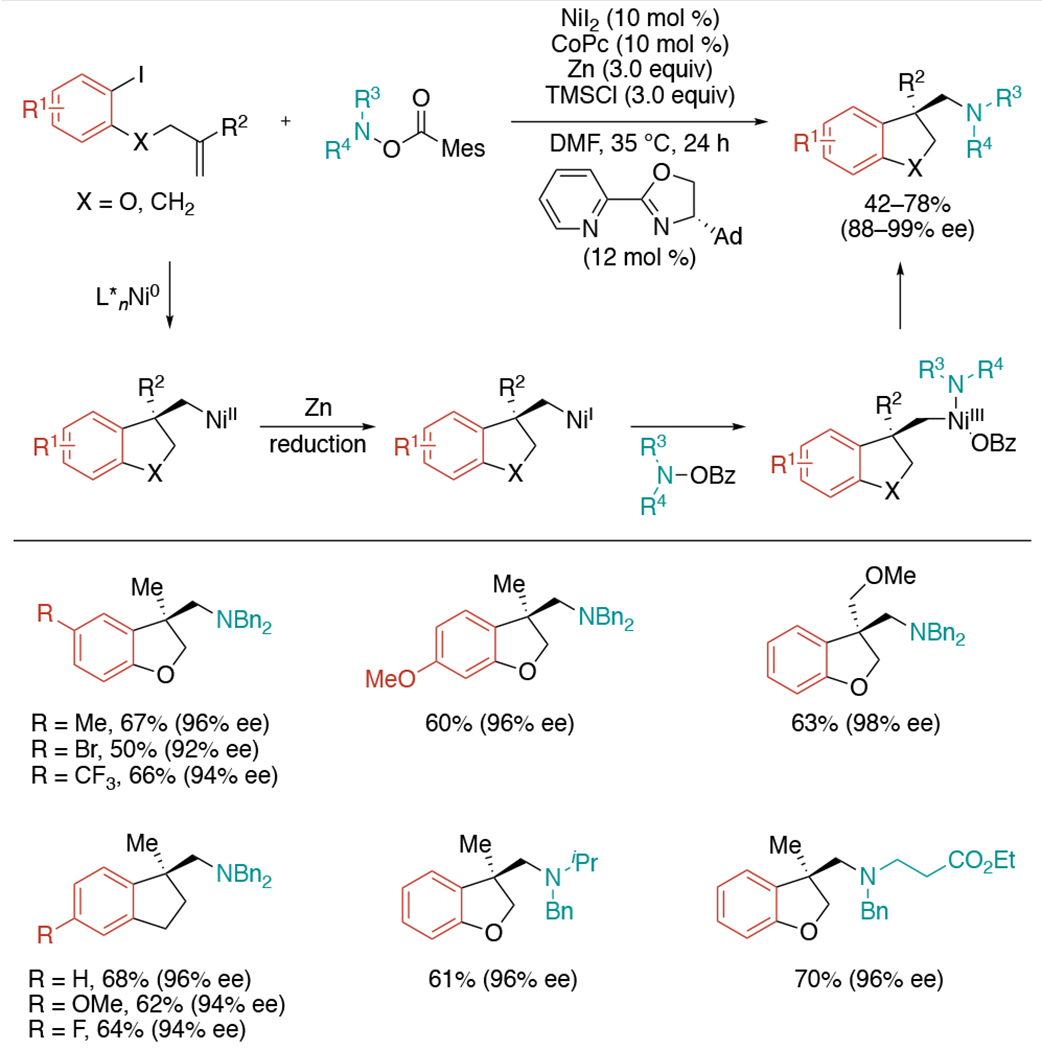

In 2020, Zhu and co-workers established a reductive 1,2-aminoarylation process under nickel/pyrox catalytic system, which allowed for the rapid and enantioselective construction of β-chiral amines using alkene-tethered aryl iodides and O-benzoylhydroxylamines as starting materials (Scheme 21).[46] The reaction begins with the oxidative addition of aryl iodide with Ni(0) to generate the arylnickel(II) complex, followed by subsequent asymmetric intramolecular cyclization with tethered 1,1-disubstituted alkenes using pyrox ligand. Stoichiometric amounts of Zn(0) efficiently reduce the alkylnickel(II) complex to the alkylnickel(I), which enables the desirable amination step. Lastly, the reductive elimination occurs to yield β-chiral amine products. It was found that the addition of cobalt(II) phthalocyanine (CoPc) as a co-catalyst and TMSCl as an additive can improve the reactivity.

Scheme 21.

Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive 1,2-aminoarylation.

3.3. Amino(hetero)arylation of C,N-tethered reagents

3.3.1. Non-cleavable C,N-tethered reagents

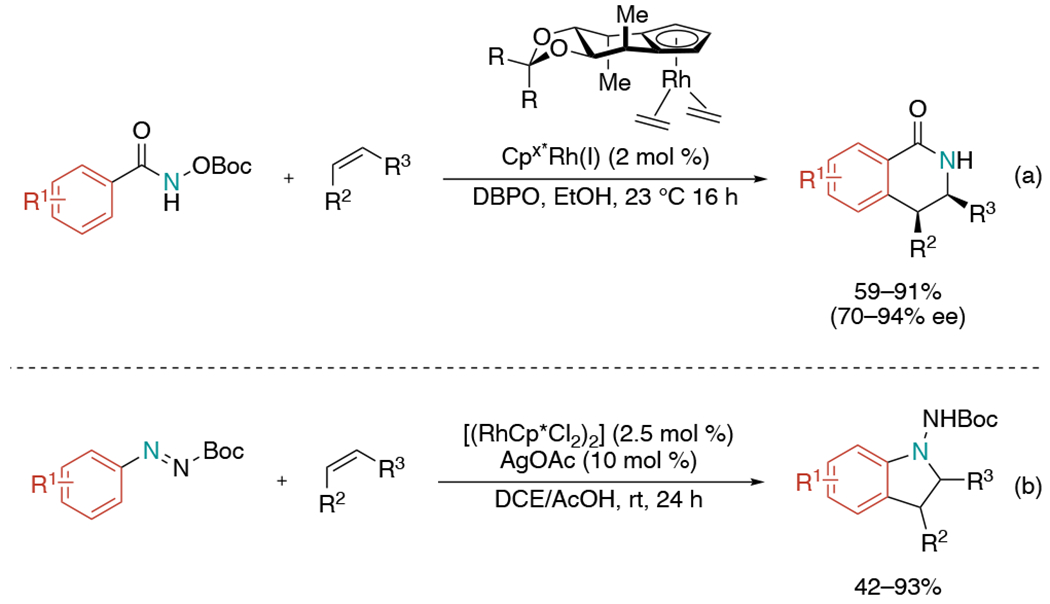

In 2012, the Cramer laboratory reported rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric C–H functionalization using chiral cyclopentadienyl (Cp) ligands (Scheme 22, a).[47] Although Cp ligands have attractive attributes such as stability and robustness, their application has been underdeveloped likely due to the inherent difficulty of designing Cp substituents. In this paper, they employed simple C2-symmetric Cp derivatives that finely control the spatial arrangement of the transiently coordinated reactants around the central metal atom. Active catalytic form of Rh(III) bis-benzoate complex is proposed to be generated by in situ oxidation of Cpx*Rh(I) with dibenzoylperoxide (DBPO).

Scheme 22.

Rhodium-catalyzed aminoarylation of alkenes with cyclopentadienyl ligands via C–H activation.

Another rhodium-catalyzed method was published enabling the synthesis of 1-aminoindoline by the Glorius group (Scheme 22, b).[48] This paper employed diazenecarboxylate as a directing group to trigger a cyclization where the nucleophilic attack of C(sp3)–Rh species, generated upon alkene insertion, to the N=N double bond. The reaction efficiently prevented competitive β-hydride elimination. Mechanistic studies implied the carboxyl substituent on the directing group could be the key in precluding this side pathway. The group also demonstrated that additional oxidants can directly synthesize 1-aminoindoles from the same starting materials.

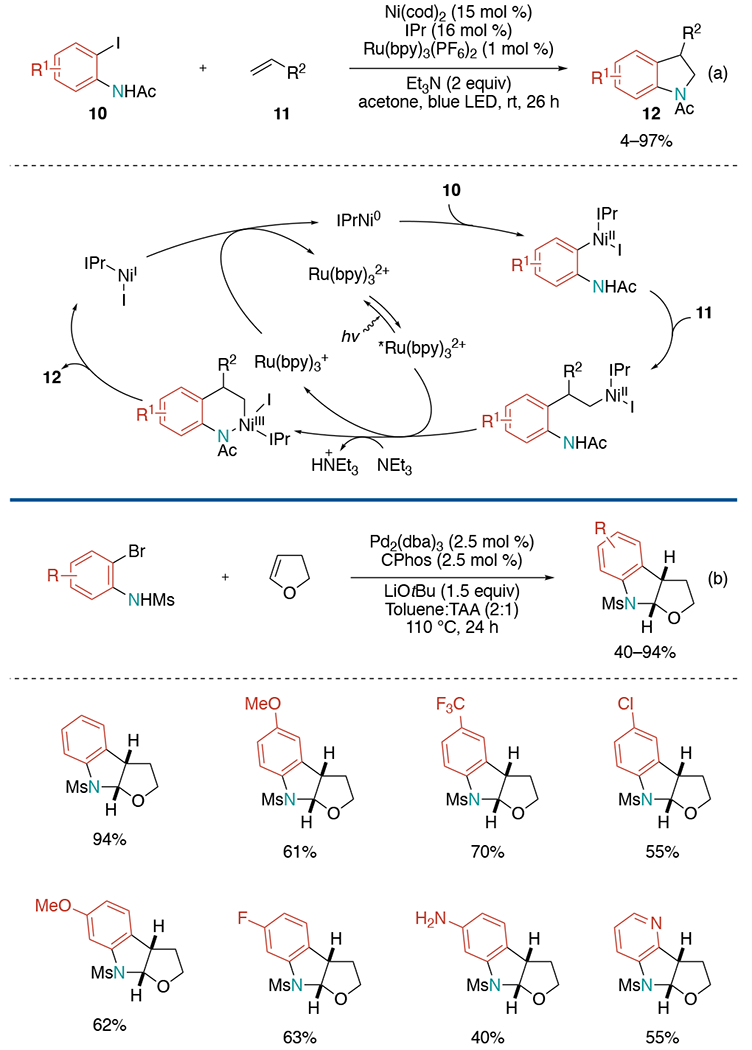

In 2015, the Jamison group disclosed a photoredox/multioxidation nickel catalyzed synthesis of indolines from iodoacetanilides and alkenes using N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand IPr (Scheme 23, a).[49] Based on their previous development of nickel-catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck reactions of aliphatic olefins,[50] they hypothesized appropriately positioned nitrogen functional group could intercept the Ni–alkyl migratory insertion intermediate and result in a direct C(sp3)–N reductive elimination. Such reductive eliminations are known to be accelerated by oxidation to Ni(III) in stoichiometric reactions.[51] Thus, they employed photoredox catalyst Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 for oxidation to Ni(III) to perform the difficult C–N bond-forming reductive elimination, producing a Ni(I) complex, which successively is reduced to Ni(0). In the mechanistic study, a stoichiometric amount of nickel and oxidant still provided desired C–N bond formation in good yield, which supported the necessity of oxidation to Ni(III) prior to product formation.

Scheme 23.

Indoline synthesis with alkenes and 2-halo-anilines.

A year later, the Mazet group has exploited a new methodology for the synthesis of furoindolines through syn-aminoarylation of dihydrofurans with excellent diastereoselectivity (Scheme 23, b).[52] Reaction condition screening exhibited the transformation with Pd2(dba)3 as a catalyst, Buchwald-type biarylphosphines as a ligand with LiOtBu in a mixture of toluene and t-amyl alcohol (TAA) successfully provides aminoarylation products in high yields and suppresses undesired dehydrobrominated mesylated aniline formation. A chiral MOP-type ligand was found to be capable of the enantioselective cross-coupling up to 73% ee.

3.3.2. Cleavable C,N-tethered reagents

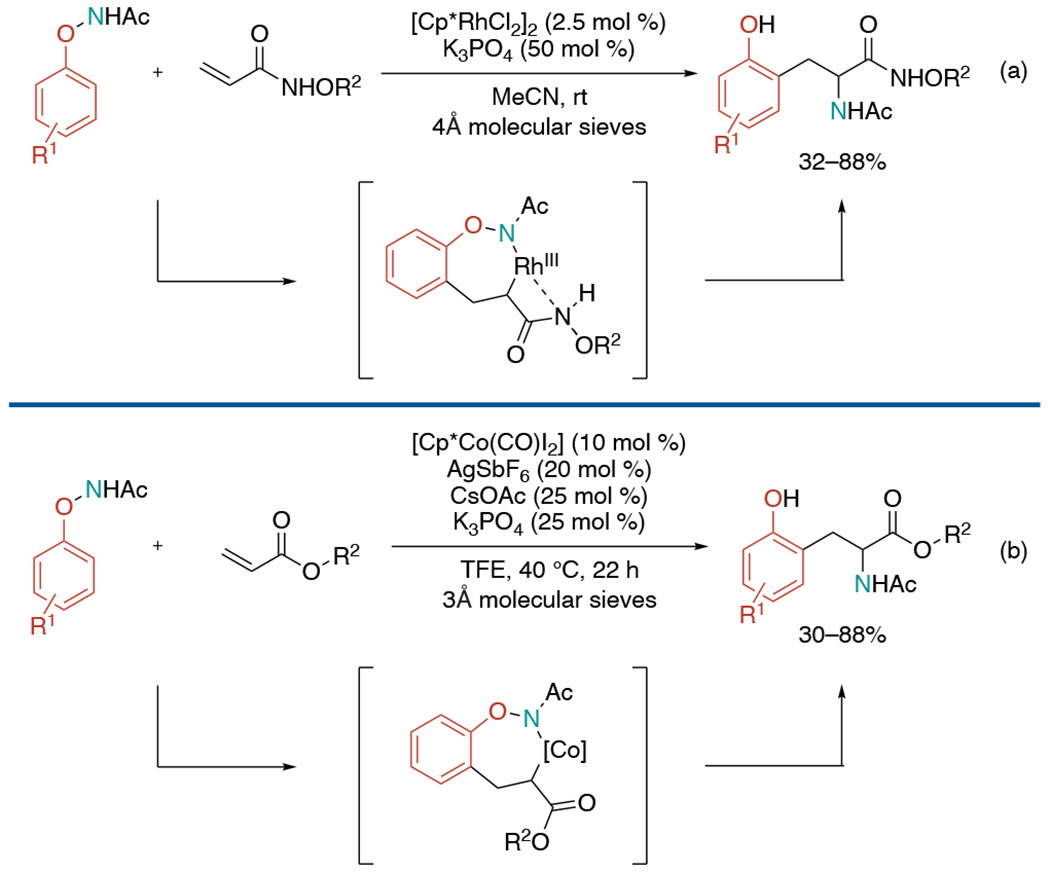

In 2016, two separate groups published non-annulative aminoarylation methods utilizing N-phenoxyacetamides as nitrogen and aryl precursors. Inspired by a Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H olefination of N-phenoxyacetamide work,[53] Liu and co-workers hypothesized that a coordinating group in the substrates may saturate the metal center and lead alkene aminoarylation (Scheme 24, a).[54] They discovered that N-alkoxyacrylamides as an alkene precursor can deliver the desired aminoarylation product under Rh catalysis. While testing different substituted acrylamides, N–H bond in acrylamides was found to be critical to enable this coupling reaction.

Scheme 24.

Non-annulative two-component carboamination of alkenes under redox-neutral system.

Meanwhile, the Glorius group revealed similar aminoarylation work using cobalt as a catalyst (Scheme 24, b).[55] They envisioned saturation of metal-center would not be required in the case of cobalt catalytic platform due to its lower propensity for β-H-elimination in comparison to rhodium. Based on this hypothesis, they could achieve the coupling between phenoxyacetamides and acrylates to synthesize unnatural amino acid derivatives, which proceeds in the absence of a bidentate directing group or a bidentate coupling partner.

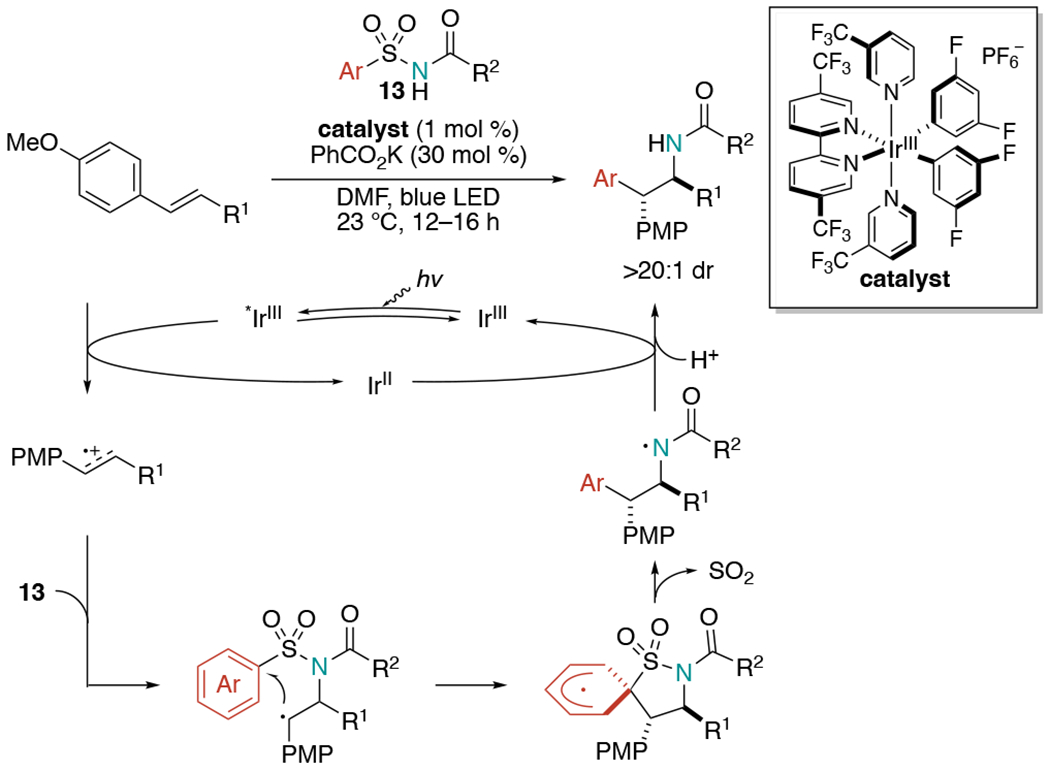

In 2018, Stephenson et al. released a paper detailing alkene aminoarylation via radical cation chemistry and Smiles-Truce aryl transfer with anti-Markovnikov regioselectivity and excellent diastereoselectivity (Scheme 25).[56] Arylsulfonylacetamides were used as bifunctional reagents, which were added across electron-rich alkenes to form both C–N and C–C bond formation in aminoarylation. This reaction is initiated by single-electron oxidation of the alkene with a photoexcited Ir(III) catalyst to form an alkene radical cation. Then, nucleophilic addition of an arylsulfonylacetamide proceeds to render a β-amino alkyl radical intermediate. This radical would undergo cyclization by adding onto the ipso-position of the aryl group. Lastly, an entropically favored desulfonylation can proceed with 1,5-aryl migration followed by construction of the aminoarylation product with the regeneration of Ir(III) catalyst. The substrate scope for this reaction was limited to para-methoxyphenyl (PMP)-substituted alkenes.

Scheme 25.

Visible-light mediated alkene aminoarylation using arylsulfonylacetamides as bifunctional reagents.

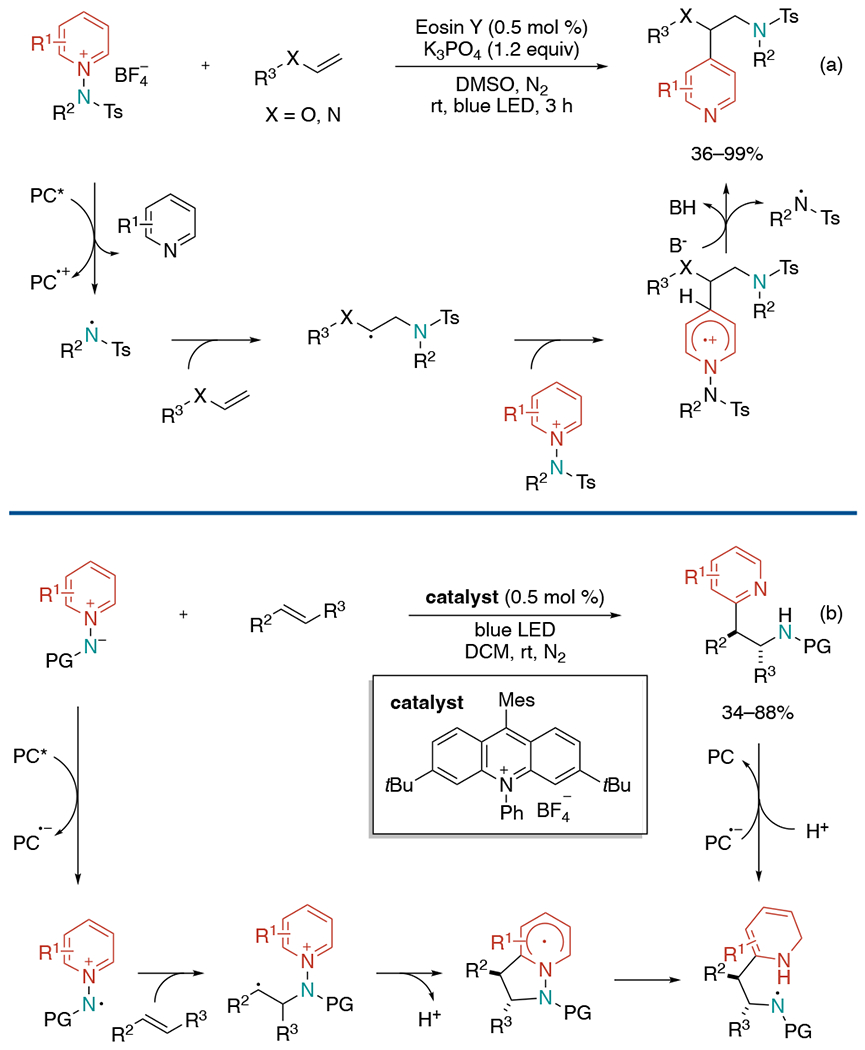

In 2019, the Hong laboratory reported work also utilizing dual-functional reagents to achieve aminopyridylation (Scheme 26, a).[57] N-aminopyridinium salts enabled simultaneous incorporation of both amine and pyridyl groups into alkenes with remarkable para-regioselectivity of pyridine. They explained the plausible mechanistic pathways supported by experimental and computational studies. The reaction is initiated by SET of N-aminopyridinium by Eosin Y followed by homolytic cleavage of the N–N bond to produce N-centered radical. This activated radical species adds onto alkene to form alkyl radical, which attacks a pyridinium species and gives unstable cationic radical intermediate. The final product is generated by deprotonation and N–N bond cleavage to release the aminyl radical, which enables a new catalytic cycle. The excellent regioselectivity was explained by electrostatic attraction between positively polarized nitrogens of the pyridinium substrate and partially negatively charged sulfonyl oxygens of β-amino radical, which directs radical trapping at the para -position of pyridinium substrates.

Scheme 26.

Visible-light induced regioselective aminopyridylation of alkenes using N-aminopyridinium reagents.

In 2020, the Hong group released an analogous protocol using N-aminopyridinium ylides to accomplish ortho-selective aminopyridylation (Scheme 26, b).[58] Inspired by 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of N-aminopyridinium ylides with alkynes, they envisioned the challenging ortho-selective aminopyridylation of alkenes could be achieved in a similar process. However, the reaction of N-aminopyridinium ylides with alkenes has proven to be problematic in classic two-electron chemistry. Their calculation on Gibb’s free energies also demonstrated the high-energy barrier of this cyclization with alkenes and the lack of a driving force in the thermodynamic process. Thus, they turned their attention to alternative approach leveraging open-shell radical cation species. It was found out that a metal-free photocatalyst could oxidize N-aminopyridinium ylides to generate N-centered radicals, which enables a stepwise 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. The reaction was applicable for both activated and unactivated alkenes. Internal olefins lead to the formation of single diastereomers with a syn-configuration via an energetically more favorable transition-state.

4. Three-component amino(hetero)arylation

4.1. Directing group assisted amino(hetero)arylation

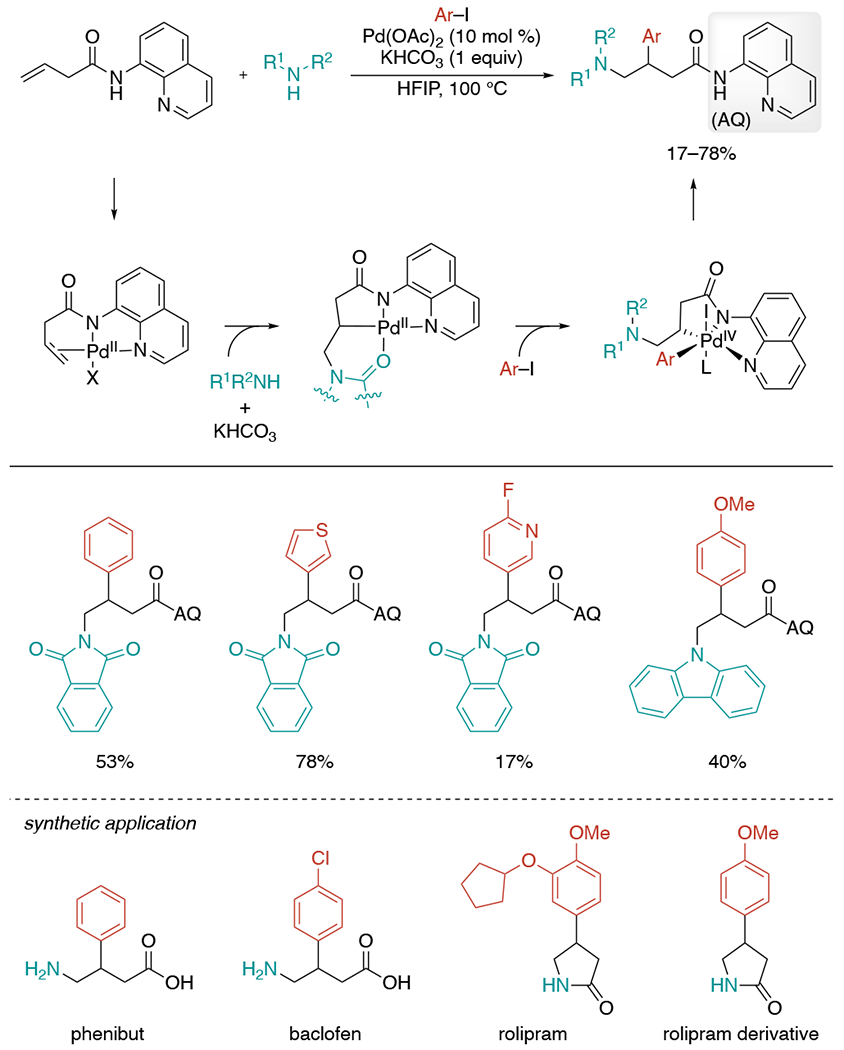

In 2017, the Engle’s lab employed a cleavable bidentate 8-aminoquinoline directing group to achieve the first Pd-catalyzed intermolecular carboamination of unactivated alkenes (Scheme 27).[59] Inspired by their previously established Pd-catalyzed alkene hydrofunctionalization[60] and dicarbonation[61], they envisaged that a chelation-stabilized aminopalladated Wacker-type intermediate could be intercepted with a carbon electrophile as a method for alkene aminocarbonation. The reaction begins with the coordination of Pd(OAc)2 and quinoline amide directing group, bringing the catalyst closer to the alkene. Nitrogen nucleophile attacks on the backside of the Pd(II)-bound alkene induced by π-Lewis acid activation to generate alkyl–Pd(II) intermediate. Owing to the stability and conformation rigidity rendered by the directing group, the intermediate does not undergo β-hydride elimination, and rather goes through oxidative addition with aryl iodide to form a Pd(IV) species. Subsequent reductive elimination results in stereoretentive C–C bond formation to form the final product. Pyridine-derived iodides reacted less efficiently under the standard conditions, requiring a substituent at 2-position to suppress the pyridine nitrogen coordination. The authors also nicely demonstrated synthetic use of this carboamination in the synthesis of γ-amino acid or γ-lactam scaffold-containing drug molecules and their derivatives.

Scheme 27.

Pd(II)/Pd(IV)-mediated intermolecular aminoarylation of unactivated alkenes via directed aminopalladation.

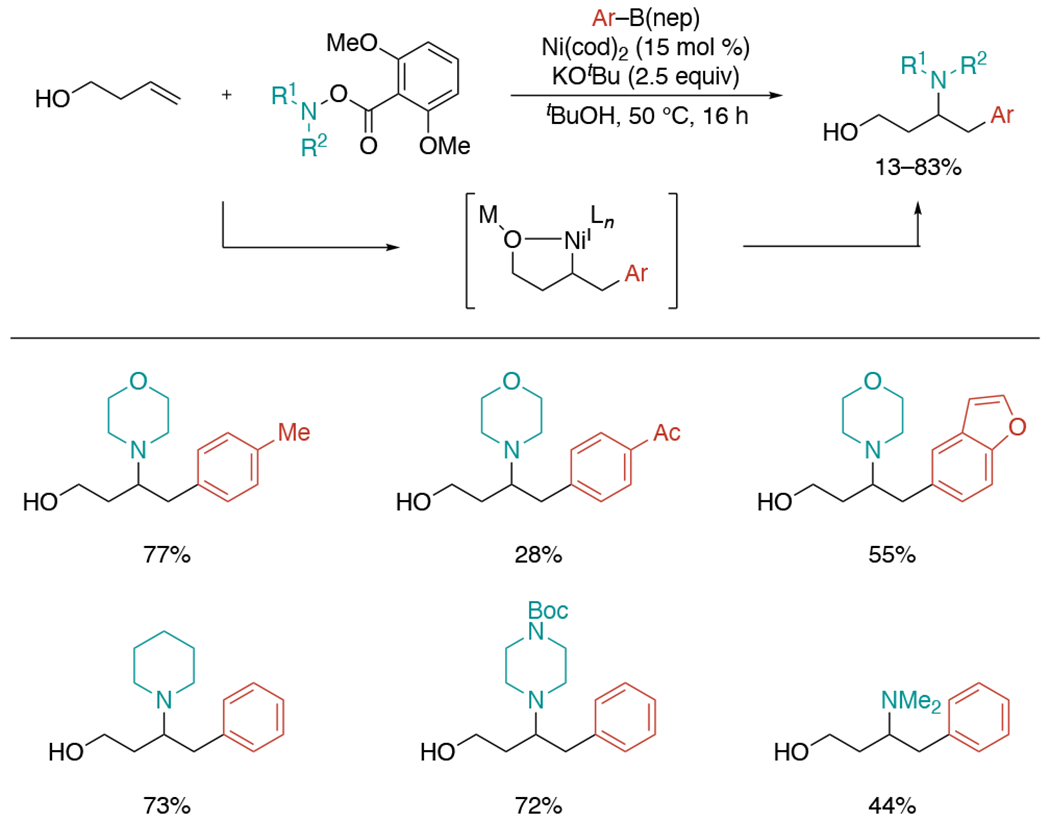

Several years later, the Engle group reported nickel-catalyzed three-component umpolung 1,2-aminoarylation of unactivated alkenes with arylboronic esters and O-(2,6-dimethoxybenzoyl)hydroxylamine (Scheme 28).[62] This protocol utilizes hydroxyl group as a directing group, which overcame the limitation of previous works requiring a directing auxiliary. While screening O-benzoyl hydroxylmorpholine with different steric and electronic substituents, O-(2,6-dimethoxybenzoyl)hydroxylamine was found to be most effective, giving the highest yield and suppressing undesired reaction pathways. Among plausible reaction mechanisms, experimental studies supported the reaction undergoes sequential transmetalation of the arylboron reagent, migratory insertion of the alkene, and oxidative addition of the N–O reagent.

Scheme 28.

Alcohol-directed, Ni-catalyzed three-component umpolung 1,2-aminoarylation of unactivated alcohols.

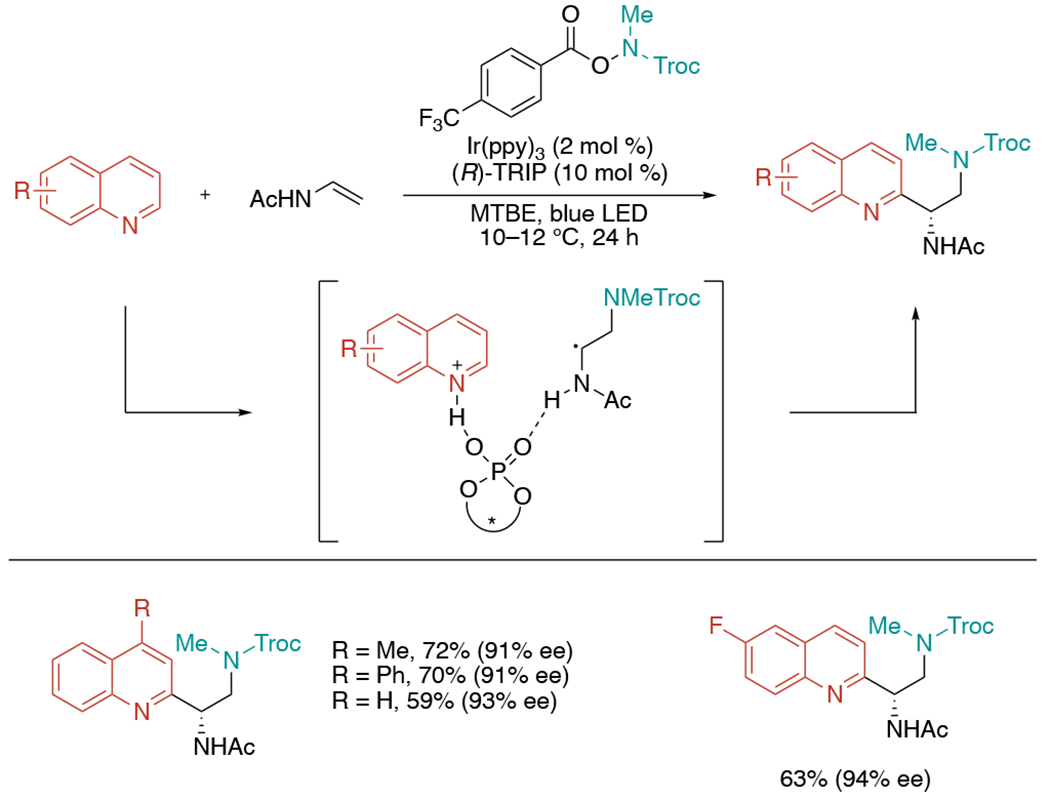

In 2019, the Studer group demonstrated photoredox- and Brønsted acid-catalyzed enantioselective three-component aminoheteroarylation of alkenes via Minisci reaction (Scheme 29).[63] This method is closely related to recent elegant developments on chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) mediated asymmetric organocatalysis.[64] The reaction proceeds smoothly with O-acyl hydroxylamines as an amine source with Ir(ppy)3 (2 mol %) and (R)-TRIP (10 mol %) as synergistic catalysts in MTBE under blue LED light. The substrate scope was limited to quinolines and Troc-protected amines.

Scheme 29.

Enantioselective three-component radical cascade reactions by dual photoredox and chiral Brønsted acid catalysis.

4.2. Styrene derivatives

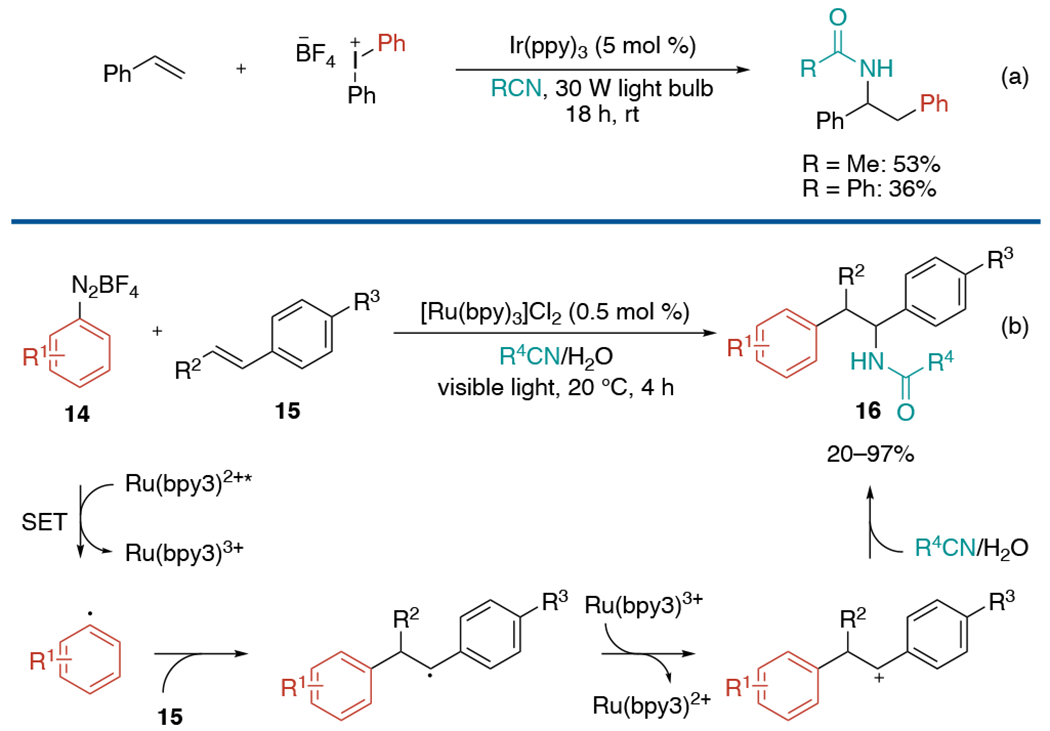

In 2013, the Greaney group demonstrated three-component coupling of styrenes with diphenyliodonium tetrafluoroborates and nitriles under a photoredox system (Scheme 30, a).[65] Soon afterward, König and co-workers adapted a photo Meerwein reaction to develop alternative three-component aminoarylation using diazonium salts and styrenes (Scheme 30, b).[66] In both reactions, aryl radicals generated by a single-electron transfer from the excited state photocatalyst add to alkenes, and the resulting alkyl radicals are oxidized to give carbenium intermediate. Subsequent nitrile attack in a Ritter-type reaction, followed by hydrolysis, affords the final product.

Scheme 30.

Photoredox-catalyzed intermolecular aminoarylation of alkenes via Ritter-type reaction.

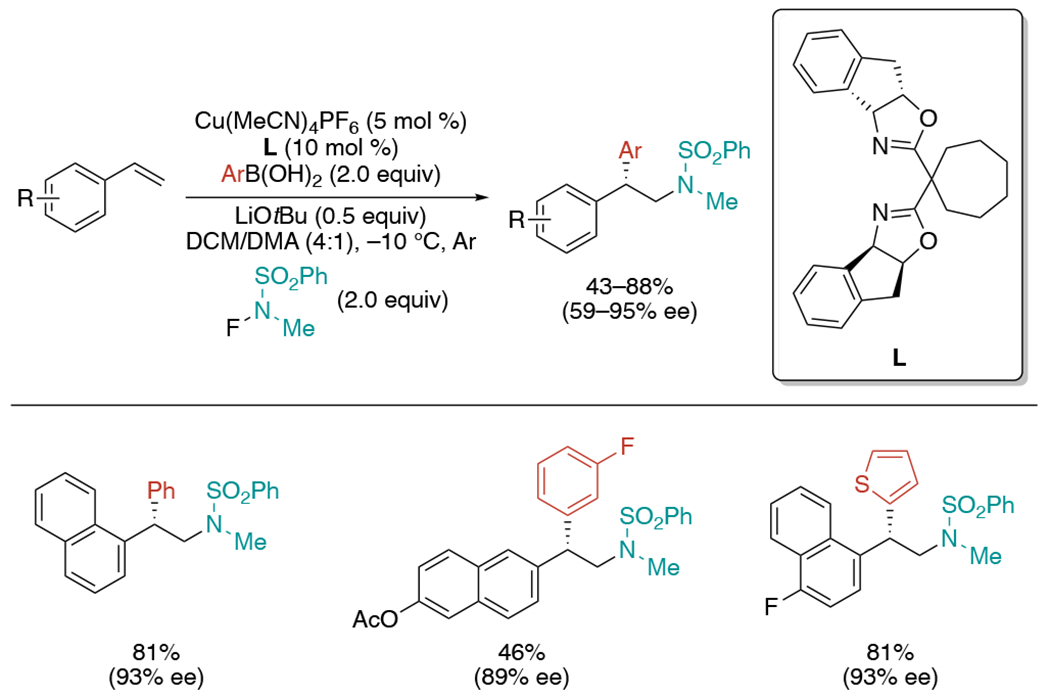

In 2017, the Liu group published the first example of copper-catalyzed asymmetric intermolecular aminoarylation reaction by using N-fluoro-N-alkylsulfonamide as an amine source (Scheme 31).[67] They envisioned that enantioselective aminoarylation of styrenes would be possible if β-amino benzylic radicals, produced by amino radical addition to styrenes, could be coupled with a L*Cu(II)–Ar specie. Toward this goal, they reacted NFSI and phenyl boronic acid under a copper catalytic system with chiral BOX ligand (L). Although promising yield and enantiometric excess were achieved in initial testing, further condition optimization did not improve the reactivity. The authors hypothesized it might be due to slow transmetalation of the arylboronic acid with Cu(II), which does not allow trapping of the excess amount benzylic radical generated by fast NFSI addition to styrenes. They found that less electrophilic amino radicals produced from N-fluoro-N-alkylsulfonamide can lead to both high yields and enantioselectivities. It was also crucial to use the solvent mixture of DCM and DMA as either solvent alone rendered only a trace amount of the product.

Scheme 31.

Cu-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular aminoarylation of styrenes using N-fluoro-N-alkylsulfonamide.

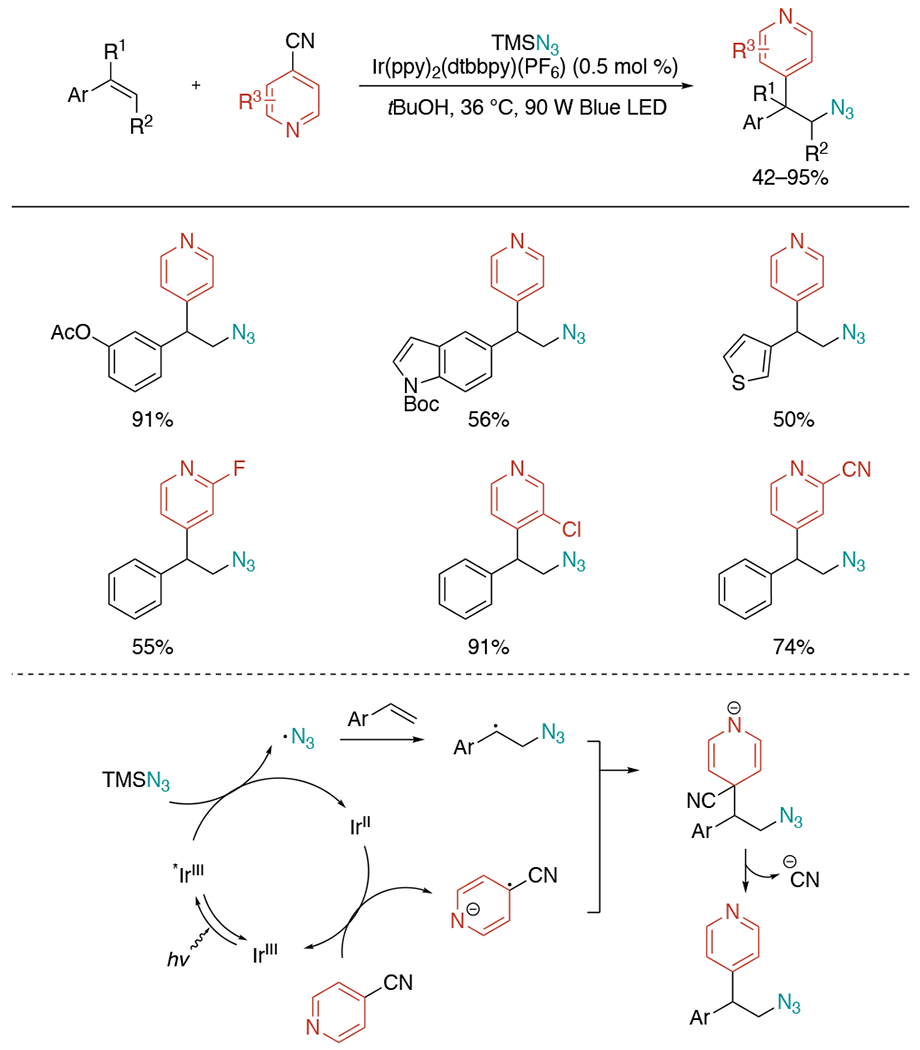

In 2019, a redox-neutral alkene azidoheteroarylation was published by the Chu lab (Scheme 32).[68] This strategy engages a visible light-induced photoredox catalytic system, which could complement previous methods requiring stoichiometric amounts of strong acid and oxidant. The reactions between cyanopyridines and styrenes can provide a wide range of β-azidopyridines in 42–95% yields.

Scheme 32.

Photoredox-catalyzed azidoheteroarylation of activated alkenes.

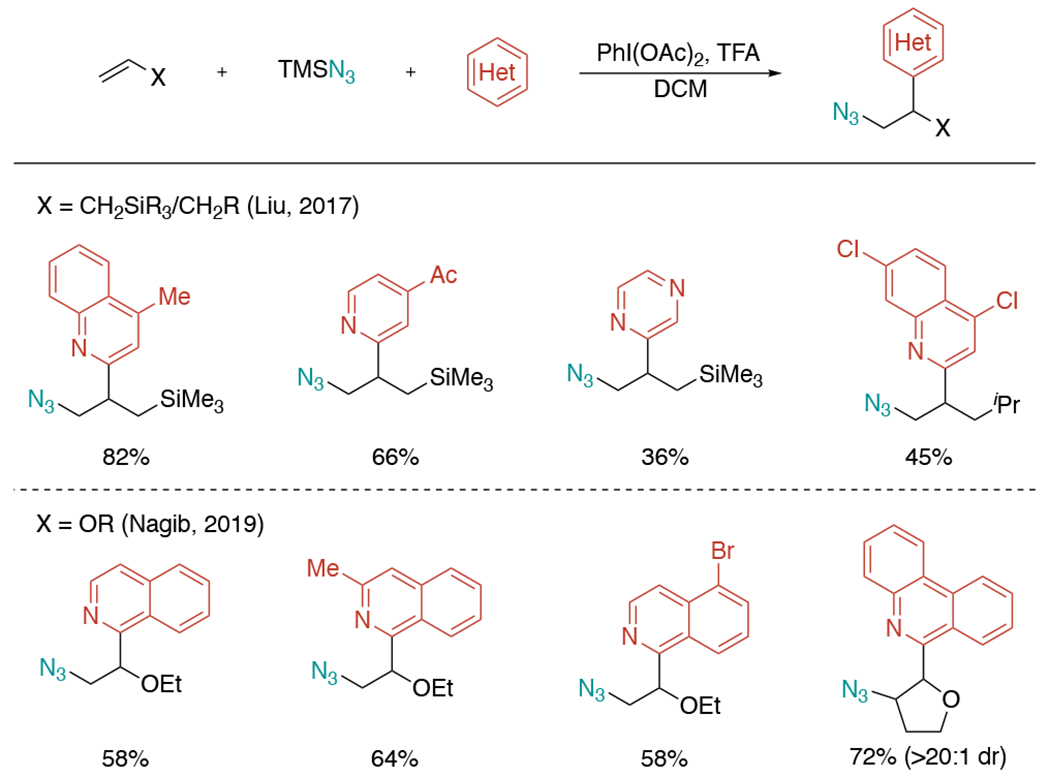

4.3. Non-styrene derivatives

In 2017, Liu et al. demonstrated a intermolecular azidoheteroarylation via metal-free cascade Minisci reaction (Scheme 33).[69] Azidyl radicals are successfully formed by one-electron oxidation of trimethylsilyl azide with hypervalent iodines. This electrophilic radical would add on to an electron-rich alkene and generate nucleophilic alkyl radical by radical polar reversal, which then could add to an electron-deficient heteroarene. Shortly thereafter, the Nagib’s lab demonstrated a unified strategy enabling the incorporation of diverse classes of electrophilic coupling counterparts including azidyl, phosphonyl, and trifluoromethyl radicals.[70]

Scheme 33.

Metal-free azidoheteroarylation of alkenes via Minisci reactions.

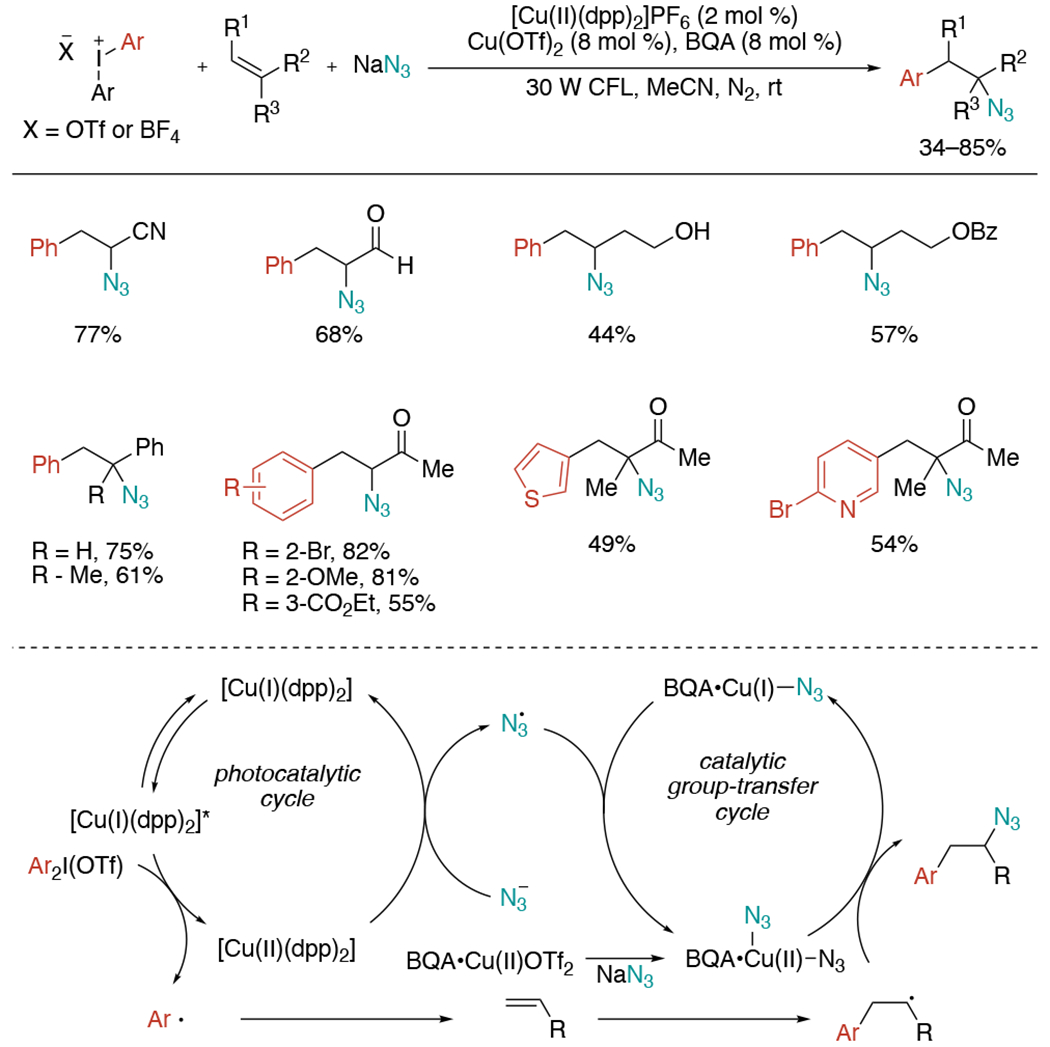

In 2021, Gaunt and co-workers reported a dual catalytic azidoarylation method that accomplished three-component coupling of alkenes, aryl electrophiles, and nitrogen nucleophiles (Scheme 34).[71] The process begins with SET of diaryliodonium triflate by quenching of the excited state of [Cu(I)dpp2]PF6 to generate the aryl radical, which then adds onto the alkene. Meanwhile, the second copper catalyst bonds with azide anion via ligand substitution and the resulting Cu(II) complex promotes the desired C–N bond formation. Sodium azide is not only used as a nitrogen source, but also a bridge in the redox-neutral dual catalysis system. While the reaction without N-t-butyl-2-quinolinecarboxaldimine (BQA) formed the azidoarylation product, BQA gave improved yield. The authors propose that BQA is likely to balance the strong σ-donor ability of the nitrogen atoms with reactivity-modulating steric properties. Accordingly, the BQA•Cu(II)(OTf)2 would capture the azide anion to provide BQA•Cu(II)(N3)2 and serve as the azido-transfer reagent. This aminoarylation protocol is broadly applicable to different classes of alkenes, including unactivated alkenes that have been very challenging for previous three-component strategies.

Scheme 34.

Redox-neutral dual catalytic azidoarylation of alkenes.

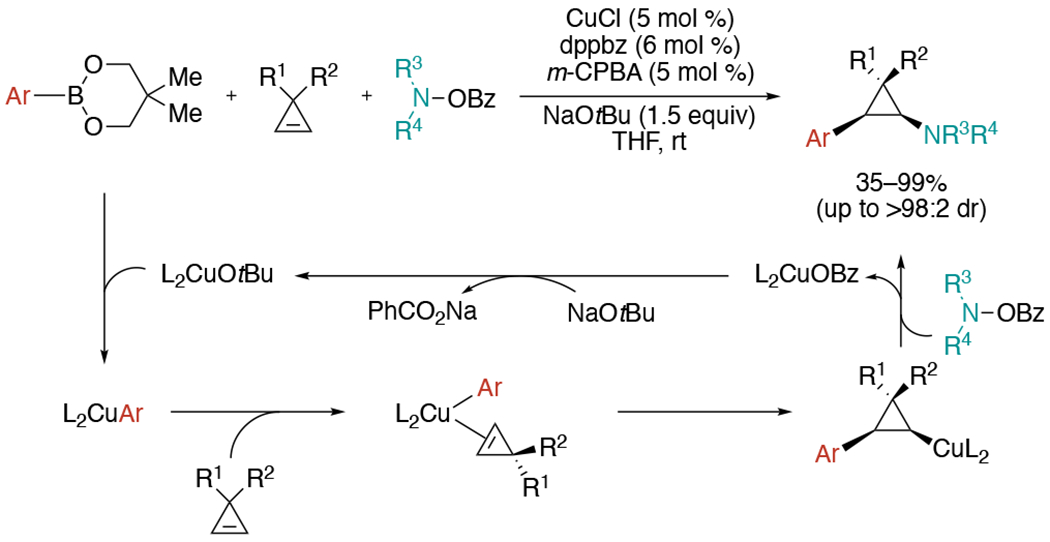

In 2019, Zhang and co-workers disclosed a multicomponent Cu-catalyzed carboamination of cyclopropenes using neopentyl boronic ester instead of strongly basic organometallics (Scheme 35).[72] Base-metal catalyzed protocols require moisture-sensitive organometallic reagents, such as Grignard, organozinc, or aluminum reagents, which proceed under Schlenk operations with restricted substrate scope. Furthermore, they induce net addition of a C–M (M = Mg, Zn, Al, etc) bond across cyclopropane to generate a cyclopropylmetal complex, likely via a fast back-transmetalation with the cyclopropylcopper intermediate. By employing milder organoboron reagents, the authors could prevent back-transmetalation and allow the trapping of an electrophilic aminating reagent with the cyclopropylcopper. This transformation was also achieved in an enantioselective version with chiral bisphosphine ligands, for the synthesis of enantioenriched 2-arylcyclopropylamines.

Scheme 35.

Cu-catalyzed aminoarylation of cyclopropenes with organoboron reagents and O-benzoylhydroxylamines.

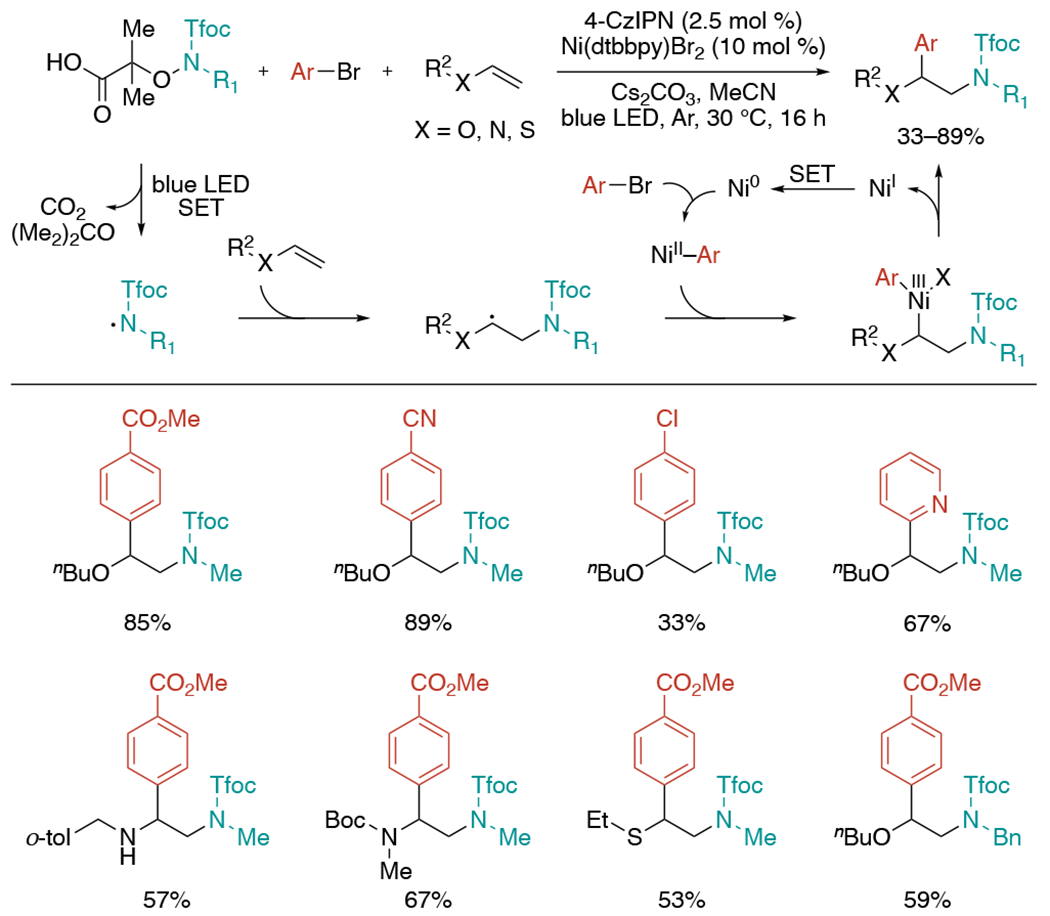

In 2021, the Studer group published a three-component 1,2-aminoarylation of electron-rich alkenes including vinyl ethers, enamides, ene-carbamates, and vinyl thioethers via photoredox and nickel catalysis (Scheme 36).[73] First, the N-centered radical generated from 2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy carbonyl protected α-amino oxy acids regioselectively adds onto the electron-rich alkene. The resulting alkyl radical intermediate would be trapped by Ni(II)–aryl species and form Ni(III) complex. Finally, reductive elimination afforded the desired aminoarylation product. Generally, aryl bromides containing electron-withdrawing groups and bromopyridines resulted in product formation in moderate to good yields, but aminoheteroarylation with electron-donating group substituted aryl bromides did not work well because of failure of the oxidative addition to Ni(0).

Scheme 36.

Photoredox and Ni-catalyzed three-component aminoarylation of electron-rich alkenes.

5. Conclusion

Significant advances in alkene 1,2-amino(hetero)arylation reactions have been achieved by transition metal catalysis, photocatalysis, or non-catalytic systems. This review presents three different strategies for recent progress in alkene amino(hetero)arylation: 1) intramolecular transformations employing C,N-tethered alkenes, 2) two-component reactions between N-tethered alkenes and external aryl precursors, C-tethered alkenes and external amine precursors, or C,N-tethered reagents and alkenes, and 3) three-component intermolecular reactions. Particularly, recent innovation in nitrogen-radical and electrophilic amination chemistry has contributed greatly to advancing amino(hetero)arylation area and novel transformation development. These novel transformations offer useful new tools for rapid entry to different (hetero)arylethylamine-containing skeletons. Although some nice applications of these methods have been documented, their synthetic application remains to be fully explored and to fulfill their potentials for wide use in organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry. Future efforts are desired to enable a modular and flexible incorporation of more diverse aryl/heteroaryl rings and amino-functional groups onto different types of alkenes, such as in a three-component manner. Furthermore, developing enantioselective protocols is highly desirable to achieve asymmetric difunctionalization on a wide range of substrate classes for high enantioselectivity.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from Duke University and the National Institutes of Health (GM118786).

Biographies

Yungeun Kwon received her B.S. degree in Chemistry from Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea in 2016. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at Duke University under supervision of Prof. Dr. Qiu Wang in the area of organic chemistry. Her research interest is the development of copper-catalyzed novel 1,2-aminocarbonation reactions of alkenes strategy.

Dr. Qiu Wang is currently Robert R. and Katherine B. Penn Associate Professor of Chemistry at Duke University. She received her Ph.D. from Emory University and completed her postdoctoral trainings at Harvard University and at the Broad Institute. The research of the Wang group focuses on development of new methods and imaging approaches for the synthesis and biological study of novel nitrogen-containing molecules.

References

- [1].Zeng X, Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 6864–6900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Njardarson Group. Top Pharmaceuticals Poster. njardarson.lab.arizona.edu/content/top-pharmaceuticals-poster (accessed 2020)

- [3].a) Wu Z, Hu M, Li J, Wu W, Jiang H, Org. Biomol. Chem 2021, 19, 3036–3054; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen X, Xiao F, He W-M, Org. Chem. Front 2021, 8, 5206–5228; [Google Scholar]; c) Kaur N, Wu F, Alom N-E, Ariyarathna JP, Saluga SJ, Li W, Org. Biomol. Chem 2019, 17, 1643–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Freeman S, Alder JF, Eur. J. Med. Chem 2002, 37, 527–539; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 2009, 20, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Aube J, Peng X, Wang Y, Takusagawa F, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 5466–5467. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Senboku H, Hasegawa H, Orito K, Tokuda M, Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 5699–5703. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tu J-L, Tang W, Liu F, Org. Chem. Front 2021, 8, 3712–3717. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sherman ES, Chemler SR, Tan TB, Gerlits O, Org. Lett 2004, 6, 1573–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zeng W, Chemler SR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 12948–12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sherman ES, Fuller PH, Kasi D, Chemler SR, J. Org. Chem 2007, 72, 3896–3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miao L, Haque I, Manzoni MR, Tham WS, Chemler SR, Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4739–4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yip K-T, Yang D, Org. Lett 2011, 13, 2134–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang W, Chen P, Liu G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 5336–5340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schultz DM, Wolfe JP, Synthesis 2012, 44, 351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ney JE, Wolfe JP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 3605–3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Bertrand MB, Leathen ML, Wolfe JP, Org. Lett 2007, 9, 457–460; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bertrand MB, Neukom JD, Wolfe JP, J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 8851–8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mai DN, Wolfe JP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12157–12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rossiter LM, Slater ML, Giessert RE, Sakwa SA, Herr RJ, J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 9554–9557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hopkins BA, Wolfe JP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 9886–9890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Garlets ZJ, Parenti KR, Wolfe JP, Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 5919–5922; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Garlets Z, Wolfe J, Synthesis 2018, 50, 4444–4452. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rosewall CF, Sibbald PA, Liskin DV, Michael FE, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 9488–9489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sibbald PA, Michael FE, Org. Lett 2009, 11, 1147–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sibbald PA, Rosewall CF, Swartz RD, Michael FE, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 15945–15951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brenzovich WE Jr., Benitez D, Lackner AD, Shunatona HP, Tkatchouk E, Goddard WA III, Toste FD, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 5519–5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang G, Cui L, Wang Y, Zhang L, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 1474–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sahoo B, Hopkinson MN, Glorius F, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 5505–5508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rigoulet M, Thillaye du Boullay O, Amgoune A, Bourissou D, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 16625–16630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zheng S, Gutiérrez-Bonet Á, Molander GA, Chem 2019, 5, 339–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Faulkner A, Scott JS, Bower JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 7224–7230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yang H-B, Pathipati SR, Selander N, ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 8441–8445. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Angelini L, Davies J, Simonetti M, Malet Sanz L, Sheikh NS, Leonori D, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 5003–5007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Matcha K, Narayan R, Antonchick AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 7985–7989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].a) Wei X-H, Li Y-M, Zhou A-X, Yang T-T, Yang S-D, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4158–4161; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yuan Y, Shen T, Wang K, Jiao N, Chem. Asian J 2013, 8, 2932–2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Qiu J, Zhang R, Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 4329–4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kong W, Merino E, Nevado C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 5078–5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li L, Gu Q-S, Wang N, Song P, Li Z-L, Li X-H, Wang F-L, Liu X-Y, Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 4038–4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li L, Li Z-L, Wang F-L, Guo Z, Cheng Y-F, Wang N, Dong X-W, Fang C, Liu J, Hou C, Tan B, Liu X-Y, Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang M, Wu Z, Zhang B, Zhu C, Org. Chem. Front 2018, 5, 1896–1899. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kwon Y, Zhang W, Wang Q, ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 8807–8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang J-L, Liu M-L, Zou J-Y, Sun W-H, Liu X-Y, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang Y-Z, Lin W-J, Zou J-Y, Yu W, Liu X-Y, Adv. Synth. Catal 2020, 362, 3116–3120. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tathe AG, Urvashi, Yadav AK, Chintawar CC, Patil NT, ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4576–4582. [Google Scholar]

- [43].White DR, Hutt JT, Wolfe JP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11246–11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fornwald RM, Fritz JA, Wolfe JP, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 8782–8790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].a) McDonald RI, Liu G, Stahl SS, Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 2981–3019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jensen KH, Sigman MS, Org. Biomol. Chem 2008, 6, 4083–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].He J, Xue Y, Han B, Zhang C, Wang Y, Zhu S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 2328–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ye B, Cramer N, Science 2012, 338, 504–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhao D, Vásquez-Céspedes S, Glorius F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 1657–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tasker SZ, Jamison TF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 9531–9534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].a) Tasker SZ, Gutierrez AC, Jamison TF, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 1858–1861; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Matsubara R, Gutierrez AC, Jamison TF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 19020–19023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Koo K, Hillhouse GL, Organometallics 1995, 14, 4421–4423. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bizet V, Borrajo-Calleja GM, Besnard C, Mazet C, ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7183–7187. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shen Y, Liu G, Zhou Z, Lu X, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 3366–3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hu Z, Tong X, Liu G, Org. Lett 2016, 18, 1702–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lerchen A, Knecht T, Daniliuc CG, Glorius F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 15166–15170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Monos TM, McAtee RC, Stephenson CRJ, Science 2018, 361, 1369–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Moon Y, Park B, Kim I, Kang G, Shin S, Kang D, Baik M-H, Hong S, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Moon Y, Lee W, Hong S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 12420–12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Liu Z, Wang Y, Wang Z, Zeng T, Liu P, Engle KM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11261–11270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gurak JA, Yang KS, Liu Z, Engle KM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5805–5808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Liu Z, Zeng T, Yang KS, Engle KM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 15122–15125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kang T, Kim N, Cheng PT, Zhang H, Foo K, Engle KM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 13962–13970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zheng D, Studer A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 15803–15807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].a) Proctor RSJ, Davis HJ, Phipps RJ, Science 2018, 360, 419–422; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lin J-S, Li T-T, Liu J-R, Jiao G-Y, Gu Q-S, Cheng J-T, Guo Y-L, Hong X, Liu X-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 1074–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Fumagalli G, Boyd S, Greaney MF, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4398–4401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Prasad Hari D, Hering T, König B, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wang D, Wu L, Wang F, Wan X, Chen P, Lin Z, Liu G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 6811–6814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chen J, Zhu S, Qin J, Chu L, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 2336–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Liu Z, Liu Z-Q, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 5649–5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lear JM, Buquoi JQ, Gu X, Pan K, Mustafa DN, Nagib DA, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 8820–8823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bunescu A, Abdelhamid Y, Gaunt MJ, Nature 2021, 598, 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Li Z, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Liu S, Zhao J, Zhang Q, Org. Lett 2019, 21, 5432–5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Jiang H, Yu X, Daniliuc CG, Studer A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 14399–14404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]