Abstract

The Escherichia coli transcriptional antiterminator protein BglG inhibits transcription termination of the bgl operon in response to the presence of β-glucosides in the growth medium. BglG is an RNA-binding protein that recognizes a specific sequence partially overlapping the two terminators within the bgl transcript. The activity of BglG is determined by its dimeric state which is modulated by reversible phosphorylation. Thus, only the nonphosphorylated dimer binds to the RNA target site and allows readthrough of transcription. Genetic systems which test dimerization and antitermination in vivo were used to map and delimit the region which mediates BglG dimerization. We show that the last 104 residues of BglG are required for dimerization. Any attempt to shorten this region from the ends or to introduce internal deletions abolished the dimerization capacity of this region. A putative leucine zipper motif is located at the N terminus of this region. The role of the canonical leucines in dimerization was demonstrated by their substitution. Our results also suggest that the carboxy-terminal 70 residues, which follow the leucine zipper, contain another dimerization domain which does not resemble any known dimerization motif. Each of these two regions is necessary but not sufficient for dimerization. The BglG phosphorylation site, His208, resides at the junction of the two putative dimerization domains. Possible mechanisms by which the phosphorylation of BglG controls its dimerization and thus its activity are discussed.

Expression of the bgl operon in Escherichia coli, induced by β-glucosides, is regulated by two of its gene products, BglG, a transcriptional regulator, and BglF, a membrane-bound β-glucoside sensor (40, 57), which constitute a novel sensory system (4). Transcription from the bgl promoter initiates constitutively, but in the absence of inducer, most transcripts terminate prematurely at one of two rho-independent terminators within the operon; in the presence of inducer, BglG allows transcription (“antiterminates” transcription) through these sites (41, 58). BglG antiterminates transcription by a novel mechanism which involves BglG binding to a specific sequence on the bgl transcript that partially overlaps with the terminators and has the potential to fold into an alternative secondary structure (30). BglF, the β-glucoside phosphotransferase, regulates BglG activity by phosphorylating and dephosphorylating it according to sugar availability (1, 2, 59). Interestingly, BglF uses the same active site to phosphorylate the sugar and the BglG protein (15). The phosphorylation site on BglG was mapped to His208 (5, 16). Reversible phosphorylation of BglG was shown to modulate the protein dimeric state (3). Thus, BglG exists as an inactive, phosphorylated monomer or as an active, nonphosphorylated dimer in the absence or presence of sugar, respectively.

BglG homologues were identified in various organisms (8, 18–20, 60, 75), e.g., SacY and SacT from Bacillus subtilis which antiterminate transcription of sacB and sacPA, respectively, according to sucrose availability (6, 17). Similar to BglG, SacY is reversibly phosphorylated in vivo, and its phosphorylation state depends on the availability of the inducing sugar and on a putative sucrose phosphotransferase, SacX (34). Phosphorylation of SacY was also studied in vitro (67). The RNA sequences recognized by SacY and SacT in the leader regions of sacB and sacPA, respectively, highly resemble the target site for BglG in the bgl transcript (7). The 50 N-terminal residues of SacY were found to be in charge of its binding to RNA, and the structure of this RNA-binding domain was studied by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray crystallography (42, 69). At high salt concentrations, this domain is present in solution as a dimer (42). The RNA-binding domain on BglG resides in a homologous domain at its N terminus (63).

As part of the global effort to elucidate the mechanism by which reversible phosphorylation of BglG, in response to an environmental stimulus, controls its dimeric state, we attempted to map its dimerization site relative to the phosphorylation site and characterize it. To identify and delimit the region required for BglG dimerization, we used the region coding for the DNA-binding domain of the CI repressor of bacteriophage λ as a reporter for dimerization (3, 32). A series of bglG DNA fragments were fused to this region. The ability of the resulting λCI′-BglG′ chimeras to dimerize was indicated by their ability to repress λ gene expression. The results demonstrate that the BglG dimerization domain is located within the carboxy-terminal 104 amino acids. This sequence starts with a putative leucine zipper dimerization motif (four leucines separated by heptads of amino acids), which is typical of DNA-binding eukaryotic transcription factors. The role of the canonical leucines in dimerization was demonstrated by replacing them with other residues. The leucine zipper is absolutely required for dimerization but is not sufficient. The remaining 70 carboxy-terminal residues are also necessary but not sufficient for dimerization. This region seems to contain another dimerization domain, since any attempt to shorten it from either end or to delete internal sequences resulted in the abolishment of dimerization. In parallel, we used a genetic system to determine which BglG sequences are required for transcription antitermination, an activity catalyzed by the dimeric form of the protein. The results of the two assays are in general agreement. The location of the BglG phosphorylation site at the heart of the dimerizing region, at what seems to be the junction of the two dimerization domains, suggests a mechanism by which phosphorylation can control dimerization according to β-glucoside availability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The following E. coli K-12 strains were used: AG1688 [MC1061 (F′128 lacIq lacZ::Tn5)] (32), a λ-sensitive bgl0 (cryptic operon) strain, was used to test for sensitivity to the cI− phage λKH54. JH372 [AG1688(λ202)] (32), which carries the λPR-lacZ chromosomal fusion, was used to measure in vivo binding to λOR1 (see below). MA152, a Δbgl strain which carries a bglG′-lacZ transcription fusion on its chromosome (λ bglR7 bglG′ lacZ+ lacY+) (40), was used to measure antitermination.

Plasmids.

The plasmids and the proteins they encode are listed in Table 1. pMN25 (bglR25 bglG+ bglF′) (40) carries the entire bglG gene. pAW25 (bglR25 bglG′) (52) carries a truncated bglG gene. pJH391 (λcI-zip::lacZ′) (33) codes for the λ repressor DNA-binding domain fused to the leucine zipper of GCN4 which contains an insertion of truncated β-galactosidase. pOAC100 expresses the DNA-binding domain (amino acids 1 through 131) of λ repressor (3). pOAC101 carries the entire bglG gene fused to λ repressor DNA-binding domain-coding sequence (3). The following plasmids were constructed as described below.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study and the proteins they encode

| Plasmid | Plasmid-encoded proteina | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pJH391 | λCI′-LZ(GCN4)::β-galactosidase | 33 |

| pMN25 | Wild-type BglG | 40 |

| pAW25 | BglG′ (aa 1–207) | 52 |

| pOAC11 | Wild type BglG | This work |

| pOAC100 | λCI′ | 3 |

| pOAC101 | λCI′-BglG | 3 |

| pOAC102 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 1–207) | This work |

| pAB1 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 123–278) | This work |

| pAB2 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 1–122) | This work |

| pAB3 | λCI′-BglG′ (Δaa 221–261) | This work |

| pAB104 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 175–278) | This work |

| pAB33 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 175–207) | This work |

| pAB70 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 209–278) | This work |

| pAB100 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 123–222) | This work |

| pAB85 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 123–207) | This work |

| pAB48 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 175–222) | This work |

| pAB104m1 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 175–278; Leu193→Ala) | This work |

| pAB104m2 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 175–278; Leu193→Ala; Leu200→Ala) | This work |

| pANS104m3 | λCI′-BglG′ (aa 175–278; Leu193→Arg; Leu200→Ala) | This work |

| pAB62 | BglG′ (aa 1–62) | This work |

| pAB104d | BglG′ (Δaa 63–174) | This work |

| pAB33d | BglG′ (Δaa 63–174 and Δaa 208–278) | This work |

| pAB70d | BglG′ (Δaa 63–208) | This work |

| pANS104m3d | BglG′ (Δaa 63–174; Leu193→Arg and Leu200→Ala) | This work |

λCI′, the λ repressor DNA-binding domain (amino acids 1 to 31); LZ(GCN4), the leucine zipper motif of the yeast GCN4 protein; BglG′, truncated BglG; aa, amino acids; Δaa, deletion of amino acids; arrow, an amino acid substitution.

pOAC11 was derived from pT7FH-G (1), which carries the entire bglG gene cloned downstream of the T7 promoter in pT713, by replacing the PpuMI site at the beginning of bglG with a SalI site by the use of a synthetic linker.

pOAC102 was constructed by replacing the SalI-BamHI fragment of pJH391, containing the zip::lacZ′ sequence, with the SalI-HindIII fragment from pOAC11, encoding a truncated BglG, after changing the HindIII site to a BamHI site by the use of a synthetic linker.

pAB2 and pAB1 were constructed by replacing the SalI-BamHI fragment from pJH391 with either the SalI-EcoRV or EcoRV-BamHI fragment of pOAC11, encoding the first 122 and the last 156 amino acids of BglG, respectively. The EcoRV site of the cloned fragments was converted to a BamHI site or SalI site, by the use of synthetic linkers, to construct pAB1 and pAB2, respectively.

pAB3 is a derivative of pOAC101 which contains a deletion of the sequence encoding amino acids 221 through 261 of BglG. It was constructed by overlap extension with PCR (28).

pAB104, pAB33, pAB70, pAB85, pAB100, and pAB48 code for different BglG fragments fused to the λ repressor DNA-binding domain. They were constructed by replacing the zip::lacZ′ sequence in pJH391 with the respective bglG sequences, which were amplified by PCR, using pOAC11 as a template.

The following plasmids were constructed by introducing base substitutions into the bglG sequence fused to the λ repressor DNA-binding domain-coding sequence in pAB104. In pAB104m1, Leu193 of BglG was mutated to an alanine. In pAB104m2, both Leu193 and Leu200 of BglG were mutated to alanines. In pANS104m3, Leu193 and Leu200 of BglG were mutated to an arginine and alanine, respectively. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by overlap extension with PCR by the method of Ho et al. (28). The mutations introduced new sites for restriction enzymes which were useful during the screening for the mutant plasmids. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequence determinations.

pAB62 was constructed by replacing the bglG gene in pMN25 with the sequence encoding the first 62 residues of BglG (sequence generated by PCR).

pAB104d, pAB33d, pAB70d, and pANS104m3d, used in the antitermination experiments, were constructed by combining the sequence coding for the first 62 residues of BglG (containing the BglG RNA-binding site) to the sequences encoding the last 104 residues of BglG, residues 175 to 207, the last 70 residues and last 104 residues containing the Leu193-to-Arg and Leu200-to-Ala mutations, respectively, by the overlap extension technique based on two-step amplification by PCR (28). In the first step, the fragments were amplified by using pMN25 as a template, except for the fragment encoding the mutated leucines which was amplified from pANS104m3. The fusions were used to replace the bglG gene in pMN25.

To ascertain the stability of proteins, the sequences encoding them were cloned downstream of the T7 promoter in pT713 or pT712 (Bethesda Research Laboratories) as follows. The EcoRI-BamHI fragments of pOAC101, pAB1, pAB2, pAB104, pAB33, pAB70, pAB48, pAB85, pAB100, pOAC102, and pANS104m3, which code for hybrids between the λ repressor DNA-binding domain and various portions of BglG, were ligated to pT713, which was cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI. Similarly, BamHI-EcoRI fragments of the plasmids listed in Table 3, which code for the first 62 residues of BglG fused to various portions of BglG, were ligated to pT712, which was cleaved with BamHI and EcoRI.

TABLE 3.

Ability of BglG derivatives to antiterminate transcription of a chromosomal bgl-lacZ fusiona

| Plasmid | Plasmid-encoded BglG derivativeb | β-Galactosidase activityc |

|---|---|---|

| pMN25 |  |

55 ± 5 |

| pAW25 | 19 ± 4 | |

| pAB62 | 3 ± 1 | |

| pAB104d | 68 ± 4 | |

| pAB33d | 2 ± 2 | |

| pAB70d | 3 ± 2 | |

| pANS104m3d | 3 ± 3 |

The experiment was performed with E. coli MA152 strain which has bgl deleted and carries a bgl-lacZ transcription fusion (40). Cells were grown in minimal medium containing 0.4% succinate.

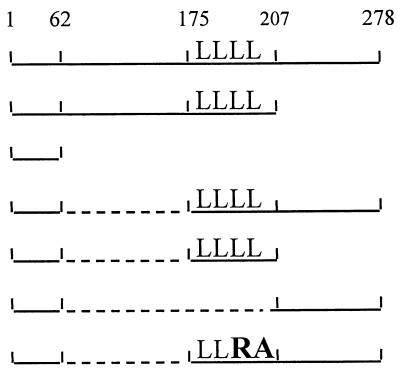

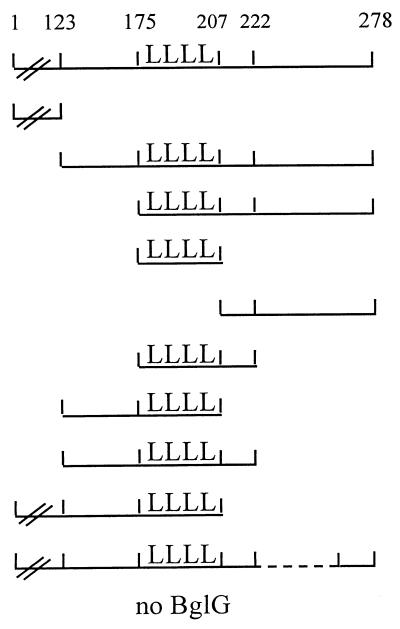

The numbers of amino acids of BglG are indicated. The broken lines indicate deleted regions in BglG. L, leucine; R, arginine; A, alanine.

The values (in Miller units) are the means ± standard deviations of four independent measurements.

The nucleotide sequences of all PCR-generated fragments were confirmed by DNA sequence determination. More details on plasmid construction, including the sequences of the primers used to generate the various deletions and mutations, are available from us on request.

Media.

Enriched (Luria-Bertani [LB]) and M63 salts minimal media were prepared essentially as described by Miller (46). All plasmids used in this study confer resistance to ampicillin, which was therefore included in the media at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml.

Molecular cloning.

All manipulations with recombinant DNA were performed by standard procedures (55). Restriction enzymes and other enzymes used in recombinant DNA experiments were purchased commercially and were used according to the specifications of the manufacturers.

Generation of nested sets of deletions in bglG with BAL 31 nuclease.

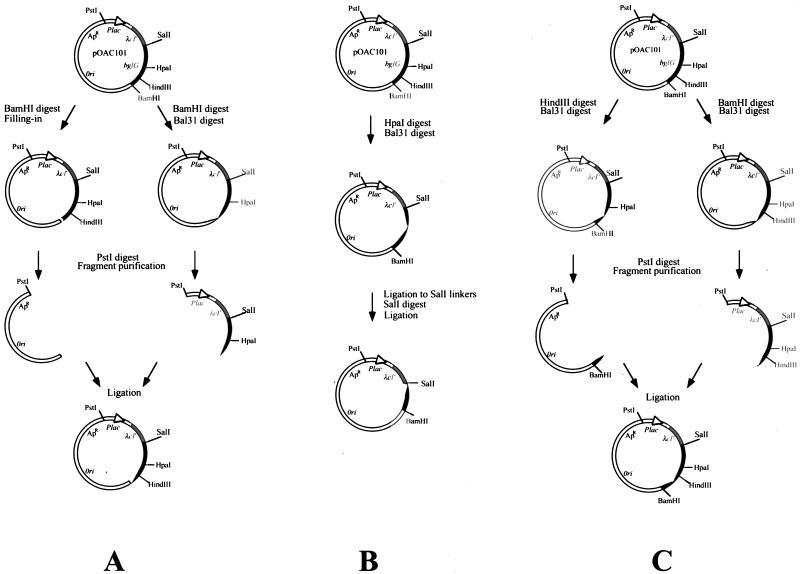

The construction of plasmid collections generated by the use of BAL 31 nuclease is illustrated in Fig. 1. In general, BAL 31 was incubated with pOAC101 that had been linearized by restriction enzymes at various locations within or near the bglG gene. Aliquots were removed every minute for 10 min. The BAL 31 reaction was stopped by adding 20 mM EGTA followed by BAL 31 inactivation at 65°C for 5 min. The DNA termini were filled in with T4 DNA polymerase and the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I (55).

FIG. 1.

Generation of nested sets of deletions in bglG. pOAC101, which codes for a fusion between the DNA-binding domain of λ repressor and the entire bglG gene, was linearized with the indicated restriction enzymes and digested with BAL 31 nuclease for various times as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Shortening bglG from its 3′ end. (B) Shortening the second half of bglG from its 5′ end, i.e., from the HpaI site, located in the middle of the bglG gene towards the 3′ end of the gene. (C) Shortening the sequence encoding the 70 C-terminal residues of BglG from both ends.

A population of bglG DNA segments progressively shortened from the 3′ end of the gene, fused to the λ repressor DNA-binding domain-coding sequence (Fig. 1A), was prepared by incubating pOAC101, linearized by BamHI (cleaves immediately after the bglG gene), with BAL 31. Samples removed after 2, 3, and 4 min were pooled together, as well as those removed after 5, 6, and 7 min and 8, 9, and 10 min. Deletion sizes, estimated by the use of restriction enzymes and gel electrophoresis, ranged from 0 to 100, 100 to 200, and 200 to 300 bp, respectively. The pooled DNA molecules were digested with PstI, and the fragments containing the shortened bglG gene were ligated to the large PstI-BamHI fragment of pOAC101, in which the BamHI site was filled in with Klenow fragment.

A set of bglG segments, segments of the second half of the bgIG gene, progressively shortened from the 5′ end and fused to the λ repressor DNA-binding domain-coding sequence (Fig. 1B) was prepared as follows: pOAC101, linearized by HpaI (cleaves in the middle of the bglG gene), was incubated with BAL 31, and aliquots were removed and pooled as described above. The BAL 31-digested plasmid collections were ligated to SalI linkers. SalI digestion removed the first half of bglG. Intermolecular ligation generated the desired sets of plasmids.

The HindIII-BamHI segment of the bglG gene (last 241 nucleotides of the bglG gene) was progressively shortened from both ends and fused to the λ repressor DNA-binding domain-coding sequence (Fig. 1C) as follows: pOAC101, linearized by BamHI, was treated with BAL 31, and aliquots were removed and pooled as described above. Deletion sizes ranged from 0 to 100, 100 to 150, and 150 to 200 bp in the three pools, respectively. The pooled DNA molecules were digested with PstI, and the fragments containing the shortened bglG segments were purified from the gel. In parallel, pOAC101 was linearized by HindIII and treated with BAL 31. Aliquots removed after 8, 9, and 10 min were pooled (between 100 and 200 bp were removed from most plasmid DNA molecules), the pooled DNA molecules were digested with PstI, and the fragments containing the shortened bglG segments were purified from the gel. Ligation between the different sets of purified fragments generated the desired sets of plasmids.

The ligated plasmids were introduced into the AG1688 strain by transformation. Transformants were screened by the colony nibbling assay to identify colonies resistant to infection with λ phage. Plasmid DNA was isolated from phage-immune colonies, and the length of the bglG segments was estimated by restriction analyses.

Phage immunity tests.

AG1688 cells, transformed with plasmids expressing fusion proteins between the λ repressor DNA-binding domain and various BglG portions, were tested for sensitivity to the cI− λKH54 phage by the following techniques. (i) The plaque assay measures the ability of the phage to form plaques on lawns of transformed bacteria. The number of plaques ranged from 0 for strain immune to the phage to approximately 100 for strains sensitive to the phage. (ii) The cross streak assay tests the ability of a strain to grow on plates when streaked through a phage lysate. (iii) In the colony nibbling assay, the phage is spread on the growth plates at a concentration which allows all transformants to form colonies, independent of their phage resistance. The phage-resistant colonies have smooth edges, whereas the phage-sensitive colonies have rough edges (51). (iv) The spot test tests the ability of the phage at concentrations ranging from 109 to 104 PFU/ml (10 μl per spot) to form plaques on lawns of bacteria.

β-Galactosidase assays.

For a quantitative assay of dimerization, the binding of the fusion proteins (between the λ repressor DNA-binding domain and various BglG portions) to λOR1 was measured. This was achieved by measuring β-galactosidase activity expressed from a PR-lacZ fusion present on the λ202 prophage found in strain JH372 (32). Because in this phage OR contains an OR2− mutation, the intact λ repressor does not show cooperative binding; its activity can be readily compared with the activity of the chimeric proteins derived from it.

For a quantitative assay of antitermination, strain MA152 (40), which has the bgl operon deleted and carries a chromosomal fusion of bgl promoter and terminator to the lacZ gene, was used. The ability of the plasmid-encoded BglG derivatives to enable lacZ expression was assayed.

Assays for β-galactosidase activity were performed by the method of Miller (46). Cells were grown in LB or in a minimal medium containing 0.4% glucose as the carbon source in the dimerization assay and in a minimal medium containing 0.4% succinate in the antitermination assay.

[35S]methionine labeling of proteins.

The different fusions cloned under T7 promoter control in pT713 or pT712 were introduced into the E. coli K-12 strain K38 containing pGP1-2, which encodes the T7 polymerase. Thermal induction and labeling with [35S]methionine were performed in the presence of rifampin (Sigma), as described previously (66). To study the stability of plasmid-encoded proteins, unlabeled methionine was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml to the growth medium (chase) following 2 min of pulse-labeling with [35S]methionine, and aliquots were removed at various times for autoradiographic analysis.

RESULTS

The dimerization domain of BglG resides in the last 104 residues.

In vivo dimerization of BglG was previously established based on its ability to replace the C-terminal dimerization domain of CI protein from bacteriophage λ (λ repressor) and enable repression of λ gene expression (3). The N-terminal DNA-binding domain of λ repressor alone (amino acids 1 to 131, designated λDBD hereafter) does not dimerize and, therefore, cannot bind strongly to the PL and PR operators on the λ genome and repress transcription. However, fusion of this domain to a heterologous dimerization domain allows it to act as an intact λ repressor (32). As a first step towards the localization of BglG dimerization domain, we attempted to determine whether it lies closer to the N or C terminus of the protein. We therefore constructed gene fusions between the sequence encoding λDBD and the sequence encoding either the 156 C-terminal or 122 N-terminal residues of BglG. Plasmids pAB1 and pAB2, respectively, carry these gene fusions (for plasmid construction, see Materials and Methods). The ability of these plasmid-encoded chimeric proteins to dimerize was indicated by their ability to protect their bacterial hosts against λ infection, confirmed by the plaque formation, cross streak, and colony nibbling assays (see Materials and Methods), and by their ability to repress expression of a λPR-lacZ chromosomal fusion. The complete BglG protein fused to λDBD, which dimerizes, and λDBD alone, which cannot dimerize, served as controls in these assays. All proteins were expressed at low concentrations from equivalent plasmid constructs. The results, presented in Table 2, clearly demonstrated that bacterial cells that expressed the 156 carboxy-terminal residues of BglG fused to λDBD were immune to infection by bacteriophage λ and exhibited 61% repression of λPR-lacZ expression compared to 70% repression conferred by the entire BglG fused to λDBD, whereas bacterial cells that expressed the 122 amino-terminal residues of BglG fused to λDBD were sensitive to infection by bacteriophage λ and could not repress λPR-lacZ expression (1% repression). The possibility that the difference in the dimerization ability of the two λDBD-BglG′ fusions is due to a difference in their stability in vivo was ruled out by pulse-chase experiments (for this purpose, the fusions were cloned after the T7-inducible promoter as described in Materials and Methods; data not shown). Thus, the BglG dimerization domain resides within the last 156 residues, since fusion of this portion of the protein to λDBD resulted in a stable, biologically active dimer.

TABLE 2.

Properties of plasmids expressing hybrid proteins containing the λ repressor DNA-binding domain

| Plasmid | BglG portion fused to λCI DNA-binding domaina | Phage sensitivityb | Repression of λPR-lacZ

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Galc | Repression (%)d | |||

| pOAC101 |  |

Immune | 546 | 70 ± 6 |

| pAB2 | Sensitive | 1,869 | 1 ± 1 | |

| pAB1 | Immune | 736 | 61 ± 4 | |

| pAB104 | Immune | 550 | 69 ± 5 | |

| pAB33 | Sensitive | 1,880 | 0 | |

| pAB70 | Sensitive | 1,869 | 1 ± 1 | |

| pAB48 | Sensitive | 1,878 | 1 ± 1 | |

| pAB85 | Sensitive | 1,871 | 1 ± 1 | |

| pAB100 | Sensitive | 1,882 | 0 | |

| pOAC102 | Sensitive | 1,850 | 2 ± 1 | |

| pAB3 | Sensitive | 2,082 | 0 | |

| pOAC100 | Sensitive | 1,888 | 0 | |

The —// symbol indicates area drawn not to scale. The broken line indicates the deleted region in BglG. Amino acid numbers of BglG are indicated. L, leucine.

Sensitivity to the cI− phage λKH54 was confirmed by the plaque formation, cross streak, and colony nibbling assays (see Materials and Methods).

For β-galactosidase (β-Gal) assays, cells were grown in minimal medium containing 0.4% glucose. The values (in Miller units) are the means of at least five independent measurements.

Repression of the chromosomal PR-lacZ fusion was calculated as follows: 1 − (β-galactosidase activity with repressor/β-galactosidase activity with no repressor). Values shown are means ± standard deviations.

To delimit the site responsible for BglG dimerization, we constructed a series of gene fusions between various bglG segments (coding mainly for fragments of the 156-residue C-terminal portion of BglG) and the sequence encoding λDBD (schematically presented in Table 2). A fusion between the last 104 residues of BglG and λDBD, expressed from pAB104, protected its bacterial host against λ infection and efficiently repressed λPR-lacZ expression (69% repression compared to 70% repression conferred by the entire BglG fused to λDBD). The other fusions in this series (expressed from pAB33, pAB70, pAB48, pAB85, pAB100, pOAC102, and pAB3 [Table 2]), which lacked parts of the last 104-residue sequence, failed to confer immunity to λ infection and to repress λPR-lacZ expression, indicating that their BglG sequences could not mediate dimerization (more details about the rationale behind the construction of these fusions are given below).

To further investigate whether a BglG fragment shorter than the last 104 amino acids of the protein is capable of mediating dimerization, we took an alternative approach. Instead of testing the ability of specific and well-defined BglG fragments to mediate dimerization, as described above, we attempted to define the shortest BglG fragment which dimerizes by screening collections of BglG fragments, progressively decreasing in size, for their ability to enable λDBD dimerization. To this end, BAL 31, a processive nuclease, was used to prepare two populations of bglG DNA segments: (i) bglG shortened from its 3′ end; (ii) the second half of bglG (bglG from the HpaI site, which cleaves in the middle of the gene, till the 3′ end) shortened from the 5′ end (see Fig. 1A and B, respectively, and Materials and Methods). These segments were fused to the sequence encoding λDBD, and the ability of the resulting plasmids to protect their bacterial hosts against λ infection was tested by the colony nibbling assay. In this assay, the phage is spread on the growth plates at a concentration which allows all transformants to form colonies, independent of their phage resistance, but while the phage-resistant colonies have smooth edges, the phage-sensitive colonies have rough edges. Plasmids were extracted from all the smooth-edged colonies and tested for their ability to confer resistance to phage after retransformation by several phage immunity tests (see Materials and Methods). The length of the bglG segment carried by the plasmids that immunized their bacterial host against λ infection was estimated by restriction analyses. The first screen was performed three times, and the second screen was performed twice; for each type of screen, approximately 50 plasmids which confer phage resistance were analyzed. In no case was a DNA segment shorter than that specifying for the last 104 residues of BglG isolated by these screens. In the first type of screen, all the isolated plasmids contained the entire bglG gene. Thus, the 3′ end of the gene also seems to be the 3′ end of the sequence encoding the dimerization domain. In the second type of screen, the bglG fragments carried by the isolated plasmids ranged from approximately 310 bp (the sequence encoding the last 104 residues) to approximately 410 bp (the gene half which was subjected to BAL 31 digestion). Therefore, the 5′ end of the region encoding the last 104 residues of BglG also seems to be the 5′ end of the dimerization domain-encoding sequence. In all these assays, it was demonstrated that BAL 31 generates fragments which were as much as 200 or 300 bp (depending on the experiment, see Materials and Methods) shorter than those isolated in the screens. It is therefore obvious that all bglG segments shorter than the ones isolated by our screens do not encode dimerizable peptides.

The results thus far indicate that the BglG dimerization domain resides within the last 104 residues. Shortening this fragment from its carboxy or amino terminus results in the loss of the ability of this peptide to dimerize.

A leucine zipper motif is involved in mediating BglG dimerization.

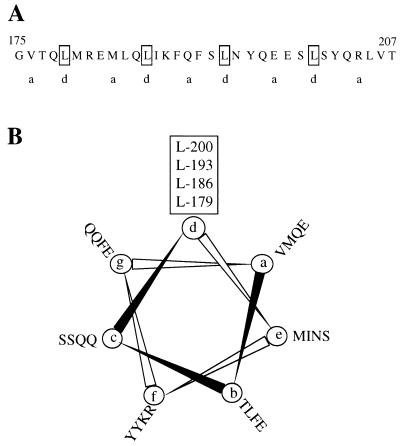

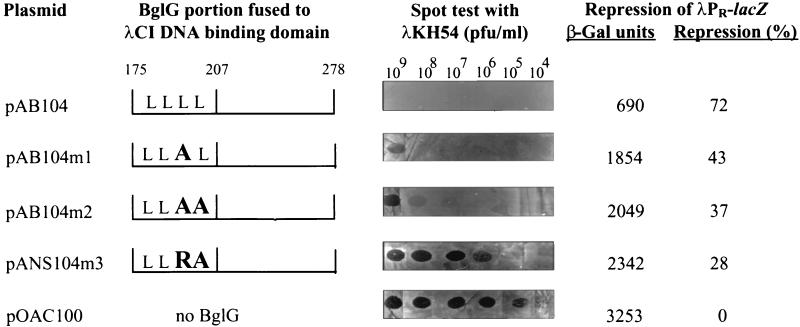

The last 104 residues of BglG start with a putative leucine zipper motif, i.e., four leucines repeated every seventh amino acid, in a sequence lacking α-helix-breaking residues (Fig. 2A). This sequence can fold into an α-helix (Fig. 2B), and two such sequences can form a coiled-coil. In order to test the importance of the canonical leucines, found in the d position of each heptad, in dimerization, we mutated one or two of these leucines by site-directed mutagenesis. One way to assess the ability of the 104-residue peptides with the leucine substitutions to dimerize was to test their ability, when fused to λDBD, to confer phage immunity upon their bacterial hosts. In addition to applying the plaque formation, cross streak, and colony nibbling assays, the phage immunity was semiquantitated by the spot test (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 3). In parallel, the ability of these chimeras to dimerize was assessed by testing their ability to repress λPR-lacZ expression. The results are presented in Fig. 3. Replacing the third canonical leucine (Leu193) by an alanine, a relatively mild change by a hydrophobic residue that allows the formation of an α-helix, resulted in a decrease in the ability of the peptide to dimerize. This was indicated by the following: (i) the sensitivity of the cells in which this chimera was expressed (from pAB104m1) to λ phage at a concentration of 109 PFU/ml (the fusion with the wild-type 104-residue peptide [containing all four canonical leucines] was resistant to this and higher phage concentrations) and (ii) a decrease in the ability to repress λPR-lacZ expression, i.e., 43% repression by the Leu193-to-Ala mutant versus 72% repression exhibited by the wild-type 104-residue peptide fused to λDBD. Replacement of two canonical leucines, the third and fourth (Leu193 and Leu200) by alanines, (fusion expressed from pAB104m2) had a bigger effect, i.e., sensitivity to 108 PFU of phage per ml and 37% repression. Replacement of the third canonical leucine (Leu193) by arginine, and of the fourth leucine (Leu200) by alanine (fusion expressed from pANS104m3) had the biggest effect in this series of experiments, i.e., sensitivity to 105 PFU of phage per ml (compared to sensitivity to 104 PFU of phage per ml given by λDBD alone) and 28% repression.

FIG. 2.

The putative leucine zipper in BglG. (A) Amino acid sequence of the leucine zipper motif found in BglG. The a and d positions of each heptad are shown. (B) Helical wheel representation of BglG leucine zipper. A total of 28 amino acids (residues Val176 to Gln203) are included in the analysis, and the view is from the amino terminus. Positions around the helical wheel are labeled a through g. The positions of the canonical leucines in BglG are indicated.

FIG. 3.

The canonical leucines in the leucine zipper motif of BglG are required for dimerization. The ability of BglG 104 C-terminal residues, wild-type and mutants with single or double leucine substitutions, to dimerize was deduced from their ability, when fused to λ repressor DNA-binding domain, to confer phage immunity and to repress λPR-lacZ expression. Phage immunity was assayed by the spot test at phage concentrations ranging from 109 to 104 PFU/ml on lawns of the bacteria transformed with the indicated plasmids. Repression of the chromosomal λPR-lacZ fusion was calculated from β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activities measured in cells grown in LB medium as described in Table 2, footnote d. The values (in Miller units) represent the averages of at least four independent measurements. The leucine substitutions are indicated by the large bold letters.

The other, more-qualitative tests for phage immunity also reflected the decreasing ability of these fusions to dimerize, starting from the Leu193-to-Ala mutant and ending with the Leu193-to-Arg Leu200-to-Ala double mutant. In the cross streak assay, pAB104m1 (Leu193-to-Ala mutant) conferred partial ability to grow through the phage compared to full immunity conferred by pAB104 (wild type), while the two double mutants behaved like λDBD alone and did not enable growth through the phage. Phage plaques were not formed on lawns of pAB104m1 and pAB104m2 transformants (replacement of one and two leucines by alanines, respectively), whereas 60 plaques were formed on a lawn of pANS104m3 transformants (Leu193-to-Arg Leu200-to-Ala double mutant) compared to the 0 and 200 plaques formed on lawns of cells expressing pAB104 (wild type) and λDBD alone, respectively, at the same phage concentration. Finally, in the colony nibbling assay, pAB104m1 behaved like pAB104 (wild type) and generated only smooth-edged colonies, while pAB104m2 and pANS104m3 generated 11 and 27% nibbled colonies, respectively. Fusions of λDBD to whole BglG derivatives with the same type of mutations, rather than only to the last 104 residues, gave essentially the same results, with slightly weaker effects on repression and phage immunity, but the hierarchy of mutation efficacy was conserved.

The effect of the leucine substitutions was further highlighted when the ability of the fusions to confer immunity to phage λ was tested at temperatures other than 37°C. At 30°C, the effects were slightly less pronounced and pAB104m1 transformants behaved like pAB104 (wild-type) transformants, whereas at 42°C, the increased sensitivity of all three mutants was more pronounced. The hierarchy in the mutations effectiveness was conserved at all temperatures.

These results demonstrate the important role played by the conserved leucines of BglG leucine zipper motif in mediating dimerization. The observed dependence of dimerization on the number of canonical leucines replaced and on the nature of the substitutions is in agreement with previous results obtained with the yeast GCN4 protein (32, 68).

Two regions, each necessary but not sufficient, mediate BglG dimerization.

Despite the demonstrated role of the leucine zipper motif in BglG dimerization, shortening the 104-residue sequence from both ends abolished its ability to dimerize, as described above. In accordance, a fusion between the leucine zipper motif alone and λDBD, expressed from pAB33, did not protect its bacterial host against λ infection and did not repress λ gene expression (Table 2). A similar behavior was obtained with a fusion lacking the leucine zipper motif and containing only the last 70 residues of BglG (fusion expressed from pAB70) (Table 2). It is therefore obvious that the leucine zipper motif is absolutely required for dimerization but not sufficient. The requirement for the additional C-terminal 70 residues might reflect the existence of a second motif which is also necessary but not sufficient for dimerization, as often observed with eukaryotic DNA-binding proteins that contain a helix-loop-helix followed by a leucine zipper, both required for dimerization (reviewed in reference 9). Alternatively, this sequence might be required to enable the formation of a stable leucine zipper structure by extending the α-helix. This demand might stem from the presence of nonhydrophobic residues at some a positions of BglG putative leucine zipper motif (Fig. 2B). If the latter explanation were correct, we would expect the fraction of the 70-residue sequence which is adjacent to the leucine zipper motif to assist in the leucine zipper dimerization, and therefore be important for that matter, while the part which is far from the leucine zipper is expected to be dispensable for dimerization. The fact that a fusion containing the leucine zipper and the subsequent 15 residues (encoded by pAB48 [Table 2]), as well as fusions progressively shortened from the C terminus of BglG (using BAL 31, described above), was unable to dimerize is not in favor of this explanation. Furthermore, adding a sequence which precedes the leucine zipper or adding the entire BglG sequence which precedes it to the leucine zipper containing λDBD fusions (pAB85 and pOAC102, respectively) did not result in dimerization either (Table 2). The same holds for the addition of sequences flanking the leucine zipper from both sides (pAB100 [Table 2]). Thus, leaving sequences on either side of the leucine zipper or on both cannot assist in its dimerization. The idea that the additional 70 residues are required merely as an extension of the leucine zipper, which enables its stable folding, is therefore not very attractive.

The possibility that phage immunity and repression were not observed with some of the fusions due to their instability in the cell was investigated by expressing the fusions shown in Table 2 from the T7-inducible promoter (for plasmid construction, see Materials and Methods) and performing pulse-chase experiments, i.e., labeling the fusions with [35S]methionine and chasing them with unlabeled methionine for different time intervals (data not shown). Most of the fusions were shown to be very stable. Only two fusions, λDBD fused to the leucine zipper alone or to the leucine zipper followed by 15 succeeding residues (cloned from pAB33 and pAB48, respectively), showed stability which was somewhat lower than that of the others. However, similar fusions, which contain an additional sequence preceding the leucine zipper but lack the carboxy terminus of BglG (i.e., those cloned from pAB85 and pAB100, respectively), were very stable. Therefore, the inability of some of the fusions shown in Table 2 to confer phage immunity and to repress λ gene expression reflects their inability to dimerize rather than their instability and proves unequivocally that the leucine zipper cannot mediate dimerization on its own.

We continued in our efforts to elucidate the role of the last 70 residues of BglG in dimerization by challenging the tolerability of this region to more deletions from its center or ends. A deletion of 40 residues from the center of the 70-residue sequence (amino acids 221 to 261), generated a BglG derivative that cannot dimerize, as indicated by its inability to protect its bacterial host against λ infection and to repress λ gene expression when fused to λDBD (pAB3 [Table 2]). Therefore, sequences in the central part of the region studied are important for dimerization. The importance of sequences at the C terminus of this region, which is the C terminus of BglG, was demonstrated by using BAL 31 nuclease as described above. Are sequences at the beginning of the 70-residue region essential for dimerization? To answer this question and further substantiate the importance of the carboxy terminus for dimerization, BAL 31 nuclease was used to prepare two populations of bglG segments which were ligated to each other as shown in Fig. 1C. One population was progressively shortened from the HindIII site, which cleaves at the 5′ end of the 70-residue region-encoding sequence. The other is the population described above which was shortened from the 3′ end of bglG. The resulting ligation products ranged from those containing a doubling of the 70-residue region-encoding sequence to those with deletions of the entire sequence encoding the 70-residue region (Fig. 1). The colony nibbling assay was used to screen bacteria transformed with the resulting mixture, fused to λDBD, for fusions conferring phage resistance, hence dimerizable. The properties and the length of the bglG sequences contained by the isolated plasmids were analyzed as described above. This experiment was repeated three times, always yielding the same result: all fusions isolated by these screens contained either the full 70-residue region-encoding sequence, or longer BamHI-HindIII segments, but never shorter.

Based on all the results presented thus far, it can be concluded that the sequence per se of BglG C-terminal 70 residues is crucial for dimerization. This sequence cannot tolerate deletions from its center or from its ends. It is therefore unlikely that this sequence is required only for stabilizing the leucine zipper structure, because if this were the case, then the sequence would be expected to tolerate some changes or deletions without losing its dimerization ability completely. The alternative explanation, that a second dimerization motif resides in this region, seems to be the right one, especially in light of additional data (see Discussion).

Studying BglG dimerization by functional analyses.

Because dimerization is a prerequisite for antitermination (3), we used an antitermination assay as an alternative approach to the dimerization assay described above to define the region involved in mediating BglG dimerization. To this end, we made use of strain MA152 which has the bgl operon deleted and carries a chromosomal fusion of the bgl promoter and terminator to the lacZ gene (40). Expression of lacZ in this strain depends on the supply of a plasmid-encoded antiterminator.

RNA binding is also a prerequisite for antitermination. The RNA-binding domain of BglG resides in the N-terminal 51 residues (63). Although this region is sufficient for RNA binding in vitro, it cannot promote antitermination of the bgl-lacZ fusion transcription in MA152 (pAB62 [Table 3]). Fusing this region to the GCN4 leucine zipper dimerization domain restored the antitermination activity (63). Therefore, in order to test the ability of various portions of BglG to dimerize and thus promote antitermination, we fused them to the first 62 residues of the protein. The ability of the plasmid-encoded fusions to antiterminate transcription and enable lacZ expression in MA152 was tested by measuring the β-galactosidase levels produced by the cells expressing them, and the results are presented in Table 3. A fusion between the first 62 and last 104 residues of BglG (expressed from pAB104d) behaved similarly to wild-type BglG (expressed from pMN25) in its ability to antiterminate transcription (68 units of β-galactosidase with pAB104d compared to 55 units with wild-type BglG). However, a similar fusion (expressed from pANS104m3d), but with Leu193 and Leu200 mutated to Arg and Ala, respectively, lost the ability to antiterminate transcription (3 units of β-galactosidase), emphasizing the importance of the leucine zipper canonical leucines for antitermination. Fusions between the first 62 residues and either the leucine zipper (expressed from pAB33d) or the last 70 residues (expressed from pAB70d) of BglG could not antiterminate transcription, as evident from the low β-galactosidase measurements (2 and 3 units, respectively). Therefore, the intact segment of the last 104 residues of BglG can promote dimerization of the RNA-binding domain and lead to antitermination, similar to its ability to promote dimerization of λDBD, whereas the leucine zipper alone or the last 70 residues alone fail to promote both. The possibility that the difference in the antitermination activity of these fusions is due to a difference in their stability in vivo was ruled out by expressing the fusions listed in Table 3 from the T7-inducible promoter (for plasmid construction, see Materials and Methods) and performing pulse-chase experiments, which demonstrated that these fusions are stable (data not shown).

Interestingly, a truncated BglG protein that terminates at the end of the leucine zipper, and thus lacks the last 70 residues but contains all the BglG sequence which precedes the leucine zipper and the leucine zipper (expressed from pAW25), has partial antitermination activity in vivo, approximately 35% of the entire protein activity (Table 3). This result implies that this truncated BglG protein can form dimers, albeit not very stable dimers. This protein, when fused to λDBD, did not enable binding to the λ operator (pOAC102 [Table 2]). Possible explanations for this apparent discrepancy are given below in the Discussion. In any case, the partial antitermination activity of this truncated BglG protein suggests again that an additional dimerization motif is indeed present in the carboxy-terminal portion, which is missing in the truncated protein.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate that dimerization of the transcriptional antiterminator BglG is mediated by the carboxy-terminal 104 amino acids. This entire region is required for dimer formation. It consists of a leucine zipper motif followed by a 70-residue region, both of which are necessary but not sufficient for dimerization. The inability to delete sequences from the ends or center of the C-terminal 70-residue region without abolishing dimerization suggests that it contains a second dimerization region. The presence of two consecutive dimerization motifs in eukaryotic DNA-binding proteins, a helix-loop-helix followed by a leucine zipper (bHLH-Zip), both required for dimerization, is quite abundant (for a review, see reference 9). Based on various types of analyses, it has been concluded that the HLH and the leucine zipper regions of bHLH-Zip proteins act together to stabilize dimer interactions and establish specificity (9, 10, 12).

In leucine zippers, the leucines which occur every seventh amino acid (at position d in every a-g heptad) form a hydrophobic spine on one face of the α-helix. Two such parallel helices interact to form a coiled-coil (21, 26, 49, 56). The reduction in BglG dimerization ability as a consequence of substitution of conserved leucines suggests that a leucine zipper is involved in mediating BglG dimerization. It has previously been shown that leucine zippers are relatively tolerant of such mutations, especially to single leucine substitutions by hydrophobic residues, including alanine, but even to more drastic single substitutions (32, 35, 47, 68, 72, 73, 74). Two leucine substitutions are less tolerated, yet some double mutants of the yeast GCN4 leucine zipper still exhibited intermediary dimerization ability and detectable dimerization-dependent activity (32, 68). The observed dependence of dimerization of the last 104 residues of BglG on the number of canonical leucines which are replaced and on the nature of the substitutions is in agreement with the results of these studies. The residual dimerization ability exhibited by the BglG double mutant, in which one of the canonical leucines was replaced by an alanine and another was replaced by an arginine, can also be attributed to the fact that the leucine zipper is followed by a second dimerization domain.

Most amino acids at a positions of the zipper of bZip proteins, in which the leucine zipper mediates dimerization on its own, are hydrophobic, and they seem to assist the conserved leucines at the d positions to form the dimer interface. In contrast, residues at the a positions of the zipper of bHLH-Zip proteins are often charged (9), suggesting that the zipper is less tight. The presence of the latter type of zipper in BglG supports the interpretation that the leucine zipper is not mediating BglG dimerization on its own but that it is one domain of a two-domain structure.

In comparison to the amount of information gathered on leucine zippers in eukaryotes, little is known about the occurrence of this motif in prokaryotes. Based on predicted amino acid sequence analyses, leucine zippers were suggested to occur in various prokaryotic proteins (e.g., 13, 24, 25, 27, 61, 62). However, in most cases the involvement of the putative motif in dimerization has not been demonstrated. The importance of the sequences containing the putative zippers for the biological activity of several bacterial proteins was demonstrated by substitution of the conserved leucines (e.g., 31, 44, 48, 70, 71) or by replacement of the putative zipper by a dimerizable sequence (37). The leucine zipper in the lactose repressor of E. coli was shown to be required for tetramer assembly from dimers (14). Recently, a direct demonstration for the involvement of the leucine zipper motif found in RepA, a replication initiator protein of the Pseudomonas plasmid pPS10, in modulating the equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric forms of the protein was reported (23). The leucine zipper of RepA resembles the leucine zipper motif of BglG, as it does not have hydrophobic residues in positions a of the zipper and it is not preceded by a basic region. Similar to BglG (see below), the leucine zipper and the nucleic acid-binding site of RepA are located at different ends of the protein.

Unlike leucine zippers in DNA-binding eukaryotic transcription regulators, which are preceded by a basic region that interacts with the DNA substrate (bZip or bHLH-Zip), the leucine zipper motif in BglG, an RNA-binding protein, is not preceded by a basic region. Rather, the RNA-binding site is removed from the dimerization site and is located at the N terminus of BglG (63). Putative leucine zippers were identified in several RNA-binding proteins and were suggested to mediate their dimerization, although in most cases this hypothesis awaits proof. Some of these leucine zippers are preceded by a basic region which, by analogy to the DNA-binding proteins, was suggested to bind to RNA, e.g., the leucine zipper found in the C protein of hnRNP complexes (45). However, the leucine zipper motif in the RNA-binding P40 protein, encoded by the human LINE-1 retrotransposon, which seems to promote P40 dimerization, is not preceded by a basic region (29). It therefore seems that in RNA-binding proteins, leucine zippers are not necessarily associated with a neighboring basic region.

The idea that a second dimerization domain resides in the last 70 residues of BglG is supported by the ability of the C-terminal 70 residues of SacY, a BglG homologue from B. subtilis, to dimerize (demonstrated by using the λ repressor DNA-binding domain as a reporter for dimerization [22a]). Based on the high degree of homology between the two proteins (75) and the ability of SacY to replace BglG in antiterminating the bgl system when expressed in E. coli (34), SacY and BglG are expected to fold similarly. The sequence of the 70-residue region of both proteins does not resemble any known dimerization motif. However, this region in both proteins has the potential for extensive α-helix formation with two interruptions by short loops (prediction of secondary structure by computer program PHDsec [53, 54]), suggesting that the interaction between two such regions involves hydrophobic interactions. Intensive study of this region in BglG and SacY is currently under way.

Two genetic systems were used to identify and characterize the BglG dimerization region. One assay tested the ability of BglG variants to mediate dimerization of λDBD and thus to promote repression of λ gene expression, whereas the other assay tested the ability of the BglG variants to antiterminate transcription, a property which depends on their ability to dimerize and thus to promote expression of a bgl-lacZ fusion. The results of the two assays are in general agreement. Only one protein, a truncated BglG which contains the leucine zipper but lacks the last 70 residues (encoded by pAW25) exhibited an inconsistent behavior in the two assays; it was capable of promoting partial antitermination of bgl transcription but incapable of promoting repression of λ gene expression when fused to λDBD. This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the difference between the two assays. It was previously claimed that transcriptional repression assays differ from activation assays, since the former require high binding site occupancy in vivo (68). The fact that the pAW25-encoded BglG derivative antiterminated transcription only partially (about 30% of wild-type activity) strongly suggests that it forms unstable dimers. This might very well result in insufficient occupancy of the λ operators and thus in lack of repression. Another difference between the two assays is that the antitermination assay involves binding of the protein to the BglG target site on the RNA. It was shown that protein domains can undergo a folding transition from a random coil to an α-helix on recognizing their cognate DNA (22). It is likely that the recognition of cognate RNA also increases the α-helix content and thus the fraction of the truncated BglG protein that folds into a leucine zipper over the fraction that is less structured at any given time. The partial antitermination activity of a truncated BglG which contains the leucine zipper but lacks the last 70 residues (expressed from pAW25 [Table 3]), taken together with the activity of a BglG variant which contains all 104 C-terminal residues but lacks most of the sequence preceding them (expressed from pAB104d [Table 3]), argues that the leucine repeats indeed contact each other in the dimers rather than interacting with other BglG sequences.

Regulation of dimerization in the BglG family of antiterminators.

Several proteins which resemble BglG, both in predicted amino acid sequence and in function, were found in various organisms. Some of the BglG homologues, e.g., ArbG from Erwinia chrysanthemi, BglR from Lactococcus lactis, and LicT from B. subtilis, were reported to be involved in β-glucoside utilization (8, 20, 36, 38). Others are involved in regulating utilization of other sugars, e.g., SacY and SacT from B. subtilis, which antiterminate transcription of sucrose utilization genes (6, 7, 18, 75), and LevR, which controls the expression of the levanase operon in B. subtilis (19). Based on analyses done with computers, these proteins were suggested to contain two regions which show weak homology, designated P1 and P2 (50) or PRD-I and PRD-II (64). By analogy to BglG, its homologues were suggested to be negatively regulated by reversible phosphorylation depending on the availability of the relevant sugar in the growth medium, and in most cases sugar phosphotransferases of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system (PTS) family were suggested or demonstrated to be involved in this type of regulation. Direct in vivo evidence for such a regulatory mechanism was obtained for SacY (34). The target for negative regulation was mapped only in BglG and LevR, and in both cases it is a histidine residue located in PRD-II (16, 43). The histidine which is phosphorylated in BglG by BglF is conserved in all known BglG homologues. Several proteins of the BglG family from gram-positive bacteria were also found to be positively regulated by phosphorylation by the general PTS protein HPr, an event suggested to have implications in carbon catabolite repression (64).

Most of the BglG homologues contain hydrophobic amino acid residues, not necessarily leucines, in all four positions at which BglG contains the conserved leucines of the leucine zipper. Theoretically, these regions might be capable of folding similarly to BglG, forming short coiled-coils (39). Formation of short coiled-coils, other than leucine zippers, was demonstrated, for example in the E. coli Tar chemoreceptor (65). The role of these hydrophobic residues of SacY and ArbG in dimerization is currently under investigation. In addition, the regions which are homologous to the last 70 residues of BglG in all BglG homologues are predicted to have a high α-helix content (prediction of secondary structure by PHDsec [53, 54]), and as mentioned above, at least in the case of SacY, it certainly contains a dimerization domain. It may be that in some of the BglG homologues, an interaction mediated by the domain found in the last 70 residues contributes more or solely to dimerization.

The RNA-binding domain of BglG and SacY resides in their 51 and 50 N-terminal residues, respectively, and the structure of this domain in SacY was determined by NMR and X-ray crystallography (42, 63, 69). Surprisingly, this domain in SacY was reported to form dimers. However, the integrity of the dimers in solution is very sensitive to salt concentration: only at 300 mM NaCl and above, a fraction of the SacY peptide (amino acids 1 to 55) was detected as dimers by gel filtration and by NMR; at lower ionic strength, the dimers dissociated into monomers, and their refolding was hard to accomplish (42). Therefore, it seems that a weak dimerization domain is contained by this segment, but its stable dimerization at physiological conditions is not anticipated, because under such conditions the dissociation rate is faster than the association rate. Manival et al. (42) also reported that N-terminal fragments of BglG homologues exhibited antitermination activities in B. subtilis, which were similar to the activities of the respective full-length proteins. The performance of BglG in these experiments was relatively poor, and the activity of its N-terminal part was even lower, but the activity of SacY and its N-terminal fragment were higher. Assuming that BglG and SacY act similarly, these results seem to contradict the results reported here concerning the inability of significant portions of BglG which contain the N terminus (half of the protein or more) to dimerize in E. coli (Table 2), and the inability of the 62 N-terminal residues of BglG and longer BglG variants to catalyze antitermination in E. coli (Table 3). Even a BglG derivative which lacks only the C-terminal 70 residues (encoded by pAW25) antiterminates bgl transcription very poorly in E. coli. Despite the apparent contradiction between the results obtained in the different organisms, it might very well be that both BglG and SacY proteins contain a weak dimerization domain at their N termini. However, association between these weak dimerization domains is likely to depend on or be facilitated by the interaction between the C termini which brings two BglG or SacY molecules together. We therefore suggest the following model for BglG and SacY dimerization: two molecules are brought together by the successive dimerization domains located at their C termini; the molecules are then zipped up, bringing the two N termini together, thus creating the RNA-binding domain. Whether the RNA contacts both subunits of the dimer or only one is not known. In any event, if the N termini have to be brought into contact and be maintained as stable dimers to form an active antiterminator molecule, the zipping up mechanism provides an explanation to how this can occur.

The dimeric state of BglG is regulated by reversible phosphorylation (3). Phosphorylation and dimerization are mutually exclusive. Thus, phosphorylated BglG is an inactive monomer, whereas the nonphosphorylated protein is an active dimer. The location of the phosphorylated residue in BglG, His208 (16), in the heart of the dimerizing region, at what seems to be the junction of two successive dimerization domains, suggests several possible mechanisms. One possibility, which is easy to envision, is that phosphorylation physically interferes with the formation of dimers. Another possibility is that the phosphorylation site is buried in the heart of the dimer and thus dimeric BglG is not recognized by its kinase, whereas the monomer is. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive and can coexist. The localization of the phosphorylation and dimerization sites to the C terminus explains why truncated BglG and SacY derivatives, which bind to RNA, are not regulated by the sugar. The zipping up from the C- to the N-terminus model suggests an explanation to how the activity of the N-terminal domain can be regulated by a phosphorylation event that occurs at the C-terminal region of the protein.

The inability of the phosphorylated BglG monomer to bind to the asymmetric RNA target site (3) needs to be explained. Manival et al. (42) suggested that in the phosphorylated form of SacY, the N-terminal part is somehow masked and is therefore not available for contacting the RNA. If both dimer subunits have to contact the RNA in order to bring about antitermination, then masking of the N-terminal weak dimerization domain in the monomer may not be necessary. However, if one subunit contacts the RNA, then a masking mechanism can explain the inability of monomeric BglG to bind to the RNA (3). A stoichiometric mechanism by which the BglG kinase, BglF, traps BglG at the membrane concomitantly with phosphorylating it, thus masking some of its parts, is improbable because BglF was shown to phosphorylate BglG at a catalytic rather than stoichiometric manner (2). Likewise, SacX, which is a negative regulator of SacY, was demonstrated to work catalytically (34). Manival et al. (42) suggested a catalytic mechanism in which the N-terminal sequence is masked in the phosphorylated monomer via interaction with sequences downstream. Dephosphorylation is then assumed to trigger the transition from an intra- to intermolecular interaction. Future studies will hopefully address this and other questions which concern the fine details of the mechanism by which phosphorylation regulates dimerization and activity of antiterminators of the BglG family. Similar mechanisms are expected to operate in other cases in which phosphorylation regulates protein activity by dictating a conformational change.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grant 91-00125 from the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF) and by the Israel Science Foundation founded by the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities-Charles H. Revson Research Foundation. A.N.-S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Israel Ministry of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amster-Choder O, Houman F, Wright A. Protein phosphorylation regulates transcription of the β-glucoside utilization operon in E. coli. Cell. 1989;58:847–855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Regulation of activity of a transcriptional antiterminator in E. coli by phosphorylation. Science. 1990;249:540–542. doi: 10.1126/science.2200123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Modulation of dimerization of a transcriptional antiterminator protein by phosphorylation. Science. 1992;257:1395–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.1382312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Transcriptional regulation of the bgl operon of E. coli involves phosphotransferase system-mediated phosphorylation of a transcriptional antiterminator. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:83–90. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. BglG, the response regulator of the Escherichia coli bgl operon, is phosphorylated on a histidine residue. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5621–5624. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5621-5624.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnaud M, Debarbouille M, Rapoport G, Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J. In vitro reconstitution of transcriptional antitermination by the SacT and SacY proteins of Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1996;51:18966–18972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aymerich S, Steinmetz M. Specificity determinants and structural features in the RNA target of the bacterial antiterminator proteins of the BglG/SacY family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10410–10414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardowski J, Ehrlich S D, Chopin A. BglR protein, which belongs to the BglG family of transcriptional antiterminators, is involved in β-glucoside utilization in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5681–5685. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5681-5685.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxevanis A D, Vinson C R. Interactions of coiled coils in transcription factors: where is the specificity? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:278–285. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90035-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckmann H, Kadesch T. The leucine zipper of TFE3 dictates helix dimerization specificity. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1057–1066. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bresnick E H, Felsenfeld G. The leucine zipper is necessary for stabilizing a dimer of the helix-loop-helix transcription factor USF but not for maintenance of an elongated conformation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21110–21116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brissette J L, Weiner L, Ripmaster T, Model P. Characterization and sequence of the E. coli stress induced psp operon. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90379-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakerian A E, Tesmer V M, Manly S P, Brackett J R, Lynch M J, Hoh J T, Matthews K S. Evidence for leucine zipper motif in lactose repressor protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1371–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Q, Arents J C, Bader R, Postma P W, Amster-Choder O. BglF, the sensor of the E. coli bgl system, uses the same site to phosphorylate both a sugar and a regulatory protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:4617–4627. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, Engelberg-Kulka H, Amster-Choder O. The localization of the phosphorylation site of BglG, the response-regulator of the E. coli bgl sensory system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17263–17268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crutz A M, Steinmetz M, Aymerich S, Roselyne R, Le Coq D. Induction of levansucrase in B. subtilis: an antitermination mechanism negatively controlled by the phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1043–1050. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1043-1050.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debarbouille M, Arnaud M, Fouet A, Klier A, Rapoport G. The sacT gene regulating the sacPA operon in Bacillus subtilis shares a strong homology with transcriptional antiterminators. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3966–3973. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3966-3973.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debarbouille M, Martin-Verstraete I, Klier A, Rapoport G. The transcriptional regulator LevR of Bacillus subtilis has domains homologous to both ς54- and phosphotransferase system-dependent regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2212–2216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Hassouni M, Henrissat B, Chippaux M, Barras F. Nucleotide sequences of the arb genes, which control β-glucoside utilization in Erwinia chrysanthemi: comparison with the Escherichia coli bgl operon and evidence for a new β-glycohydrolase family including enzymes from eubacteria, archaebacteria, and humans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:765–777. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.765-777.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellenberger T E, Brandl C J, Struhl K, Harrison S C. The GCN4 basic region LZ binds DNA as a dimer of uninterrupted alpha-helices: crystal structure of the protein-DNA complex. Cell. 1992;71:1223–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferre-D’Amare A R, Pognonec P, Roeder R G, Burley S K. Structure and function of the b/HLH/Z domain of USF. EMBO J. 1994;13:180–189. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Fux, L., and O. Amster-Choder. Unpublished data.

- 23.Garcia de Viedma D, Giraldo R, Rivas G, Fernandez-Tresguerres E, Diaz-Orejas R. A leucine zipper motif determines different functions in a DNA replication protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:925–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaur N K, Oppenheim J, Smith I. The Bacillus subtilis sin gene, a regulator of alternate developmental processes, codes for a DNA-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:678–686. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.678-686.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge Z, Chan N W, Palcic M M, Taylor D E. Cloning and heterologous expression of an alpha1,3-fucosyltransferase gene from the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21357–21363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glover J N, Harrison S C. Crystal structure of the heterodimeric bZIP transcription factor c-Fos-c-Jun bound to DNA. Nature. 1995;373:257–261. doi: 10.1038/373257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzman L M, Barondess J J, Beckwith J. FtsL, an essential cytoplasmic membrane protein involved in cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7716–7728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohjoh H, Singer M F. Cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes containing human LINE-1 protein and RNA. EMBO J. 1996;15:630–639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houman F, Diaz-Torres M R, Wright A. Transcriptional antitermination in the bgl operon of E. coli is modulated by a specific RNA binding protein. Cell. 1990;62:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90392-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh M, Gralla J D. Analysis of the N-terminal leucine heptad and hexad repeats of sigma 54. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:15–24. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu J C, O’Shea E K, Kim P S, Sauer R T. Sequence requirements for coiled-coils: analysis with λ repressor GCN4 leucine zipper fusions. Science. 1990;250:1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.2147779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J C, Newell N E, Tidor B, Sauer R T. Probing the roles of residues at the e and g positions of the GCN4 leucine zipper by combinatorial mutagenesis. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1072–1084. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Idelson M, Amster-Choder O. SacY, a transcriptional antiterminator from Bacillus subtilis, is regulated by phosphorylation in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:660–666. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.660-666.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouzarides T, Ziff E. The role of the leucine zipper in the Fos-Jun interaction. Nature. 1988;336:646–651. doi: 10.1038/336646a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruger S, Hecker M. Regulation of the putative bglPH operon for aryl-β-glucoside utilization in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5590–5597. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5590-5597.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau P C K, Wang Y, Patel A, Labbe D, Bergeron H, Brousseau R. A bacterial basic region leucine zipper histidine kinase regulating toluene degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1453–1458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Coq D, Lindner C, Kruger S, Steinmetz M, Stulke J. New β-glucoside (bgl) genes in Bacillus subtilis: the bglP gene product has both transport and regulatory functions similar to those of BglF, its Escherichia coli homolog. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1527–1535. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1527-1535.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahadevan S, Reynolds A E, Wright A. Positive and negative regulation of the bgl operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2570–2578. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2570-2578.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahadevan S, Wright A. A bacterial gene involved in transcription antitermination: regulation at a rho-independent terminator in the bgl operon of E. coli. Cell. 1987;50:485–494. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manival X, Yang Y, Strub M P, Kochoyan M, Steinmetz M, Aymerich S. From genetic to structural characterization of a new class of RNA-binding domain within the SacY/BglG family of antiterminator proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16:5019–5029. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin-Verstraete I, Charrier V, Stulke J, Galinier A, Erni B, Rapoport G, Deutscher J. Antagonistic effects of dual PTS-catalysed phosphorylation on the Bacillus subtilis transcriptional activator LevR. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:293–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maxon M E, Wigboldus J, Brot N, Weissbach H. Structure-function studies on Escherichia coli MetR protein, a putative prokaryotic leucine zipper protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7076–7079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McAfee J G, Shahied-Milam L, Soltaninassab S R, Lestourgeon W M. A major determinant of hnRNP C protein binding to RNA is a novel bZIP-like RNA binding domain. RNA. 1996;2:1139–1152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moitra J, Szolak L, Krylov D, Vinson C. Leucine is the most stabilizing aliphatic amino acid in the d position of a dimeric leucine zipper coiled coil. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12567–12573. doi: 10.1021/bi971424h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noonan B, Trust T J. The leucine zipper of Aeromonas salmonicida AbcA is required for the transcriptional activation of the P2 promoter of the surface-layer structural gene, vapA, in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Shea E K, Rutkowski R, Stafford W, Kim P S. Preferential heterodimer formation by isolated leucine zippers from Fos and Jun. Science. 1989;245:646–648. doi: 10.1126/science.2503872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reizer J, Saier M H., Jr Modular multidomain phosphoryl transfer proteins of bacteria. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Revel H R. Restriction of nonglucosylated T-even bacteriophage: properties of permissive mutants of Escherichia coli B and K12. Virology. 1967;31:688–701. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reynolds A E, Mahadevan S, Le Grice S F J, Wright A. Enhancement of bacterial gene expression by insertion elements or by mutation in a CAP-cAMP binding site. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein structure at better than 70% accuracy. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rost B, Sander C. Combining evolutionary information and neural networks to predict protein secondary structure. Proteins. 1994;19:55–72. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saudek U, Pastore A, Castiglione-Morelli M A, Frank R, Gansepohl H, Gibson T. The solution structure of a leucine-zipper motif peptide. Protein Eng. 1991;4:519–528. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schnetz K, Toloczyki C, Rak B. β-Glucoside (bgl) operon of Escherichia coli K-12: nucleotide sequence, genetic organization, and possible evolutionary relationship to regulatory components of two Bacillus subtilis genes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2579–2590. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2579-2590.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schnetz K, Rak B. Regulation of the bgl operon of E. coli by transcriptional antitermination. EMBO J. 1988;7:3271–3277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schnetz K, Rak B. β-Glucoside permease represses the bgl operon of E. coli by phosphorylation of the antiterminator protein and also interacts with glucose-specific enzyme II, the key element in catabolic control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5074–5078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schnetz K, Stulke J, Gertz S, Kruger S, Krieg M, Hecker M, Rak B. LicT, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator protein of the BglG family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1971–1979. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1971-1979.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selby C P, Sancar A. Molecular mechanism of transcription-repair coupling. Science. 1993;260:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.8465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimada H, Wada T, Handa H, Ohta H, Mizoguchi H, Nishimura K, Masuda T, Shioi Y, Takamiya K. A transcription factor with a leucine-zipper motif involved in light-dependent inhibition of expression of the puf operon in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:515–522. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh J, Bailey M, Diaz-Torres M, Wright A. Molecular Genetics of Bacteria and Phages Meeting. 1994. The interaction between the antiterminator protein BgIG and its RNA target; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stulke J, Arnaud M, Rapoport G, Martin-Verstraete I. PRD—a protein domain involved in PTS-dependent induction and carbon catabolite repression of catabolic operons in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:865–874. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Surette M G, Stock J B. Role of α-helical coiled-coil interactions in receptor dimerization, signaling, and adaptation during bacterial chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17966–17973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tabor S, Richardson J. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase-promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tortosa P, Aymerich S, Lindner C, Saier M H, Jr, Reizer J, Le Coq D. Multiple phosphorylation of SacY, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator negatively controlled by the phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17230–17237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]