Abstract

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/myeloproliferative disorder most commonly seen in the elderly. We describe an adolescent with monosomy 7 CMML presenting as central diabetes insipidus (DI), who was treated with venetoclax and decitabine as a bridge to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Central DI is a rare manifestation of monosomy 7-associated MDS including CMML, itself a rare manifestation of GATA2 deficiency, particularly in children. Venetoclax/decitabine was effective for treatment of CMML as a bridge to HSCT.

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/myeloproliferative disorder most commonly seen in the elderly.1,2 We describe an adolescent with GATA2 associated monosomy 7 CMML presenting as central diabetes insipidus (DI), who was successfully treated with venetoclax and decitabine as a bridge to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

A 15-year-old adolescent male presented to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for initial evaluation of GATA2 deficiency on the Natural History of GATA2 Deficiency Study (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01905826) based on his mother and aunt’s known diagnoses of GATA2 deficiency. His mother was successfully transplanted for MDS from a partially matched sibling 15 years earlier. Previous sequencing of the patient’s aunt identified a germline heterozygous GATA2 mutation, c.1017+572C>T, consistent with GATA2 deficiency. The patient was otherwise previously healthy, but he did report a 6-month history of new-onset polydipsia (3–4 gallons of water per day) and polyuria (urinating hourly with at last five nighttime awakenings).

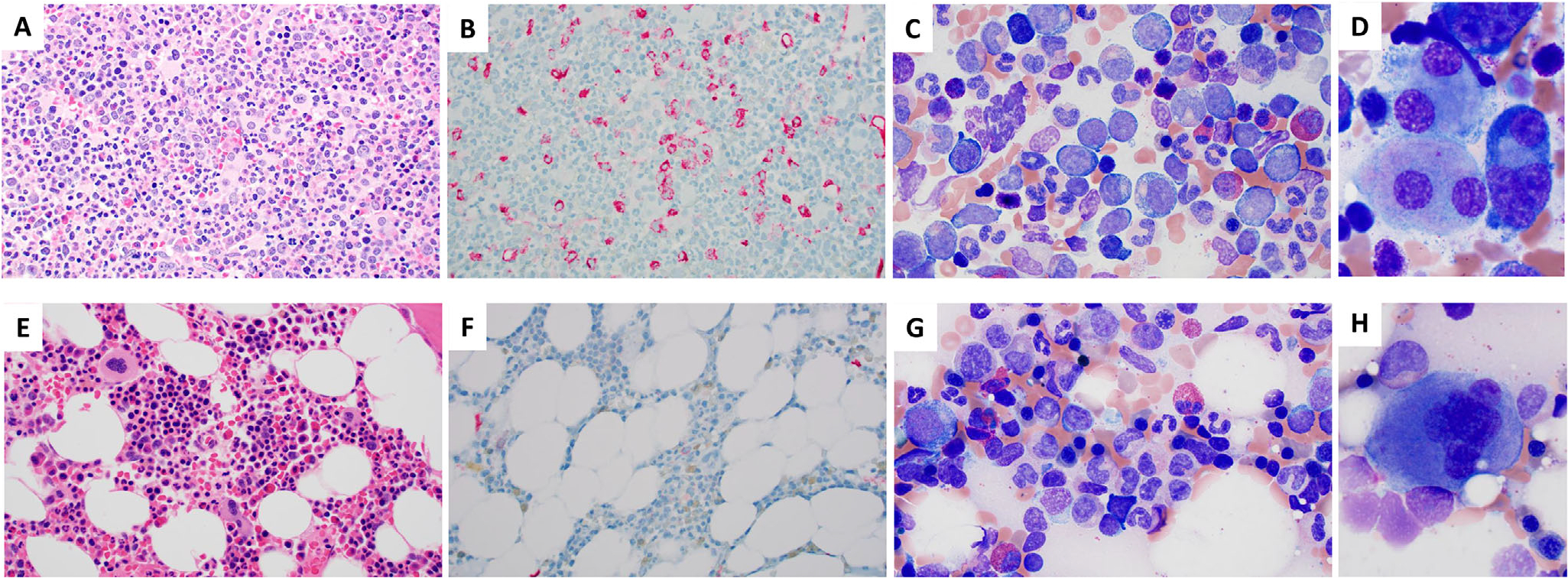

Routine labs revealed leukocytosis (WBC 15.61 K/μL), monocytosis with 10% circulating monocytes (1.6 K/μL) (Table S1). Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a markedly hypercellular bone marrow (90–100% cellularity), with increased dysplastic megakaryocytes, myeloid and erythroid dyspoiesis, and increased myeloblasts (6–8%) (Figure 1A–D) (Table S2). Flow cytometry confirmed abnormal myeloblasts that expressed CD117, CD13, CD33, HLA-DR, with downregulated CD38 and MPO, and negative TdT, CD79a, and cytoplasmic CD3. Cytogenetic analysis revealed monosomy 7 (45,XY,−7) in 20/20 metaphase, and molecular testing identified clonal ASXL1, SETBP1, and U2AF1 mutations.

FIGURE 1.

Clinical course illustrating hematopoietic changes. A-D, Bone marrow evaluation at diagnosis showing increased circulating monocytes and blasts, a markedly hypercellular marrow with atypical megakaryocytes on the core biopsy, and increased blasts on the aspirate smear with dysplastic megakaryocytes showing separated nuclear lobes. A, Core biopsy showing markedly hypercellular marrow with dysplastic megakaryocytes (H&E 500×). B, CD34 immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrating increased blasts (6–8%, 500×). C, Marrow aspirate with increased blasts and left shift (Wright-Giemsa [WG], 1000×). D, Dysplastic megakaryocytes with separated nuclear lobes (WG, 1000×, cropped). E-H, Posttransplant evaluations demonstrate eradication of underlying chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)/myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). E, Mildly hypocellular marrow with active trilineage hematopoiesis (H&E, 500×). F, CD34 IHC showing no increase in CD34+ blasts (500×). G, Aspirate with normal maturing hematopoiesis (WG 1000×). H, Normal megakaryocyte (WG, 1000×, cropped)

He was subsequently diagnosed with MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) consistent with CMML (proliferative subtype) with germline GATA2 mutation.3 The patient’s CMML could not be further subdivided into CMML-1 or CMML-2 as the peripheral blood blast and promonocyte count was too high for CMML-1 and the bone marrow blast count was not high enough for CMML-2. Overall the patient’s disease showed high-risk features.

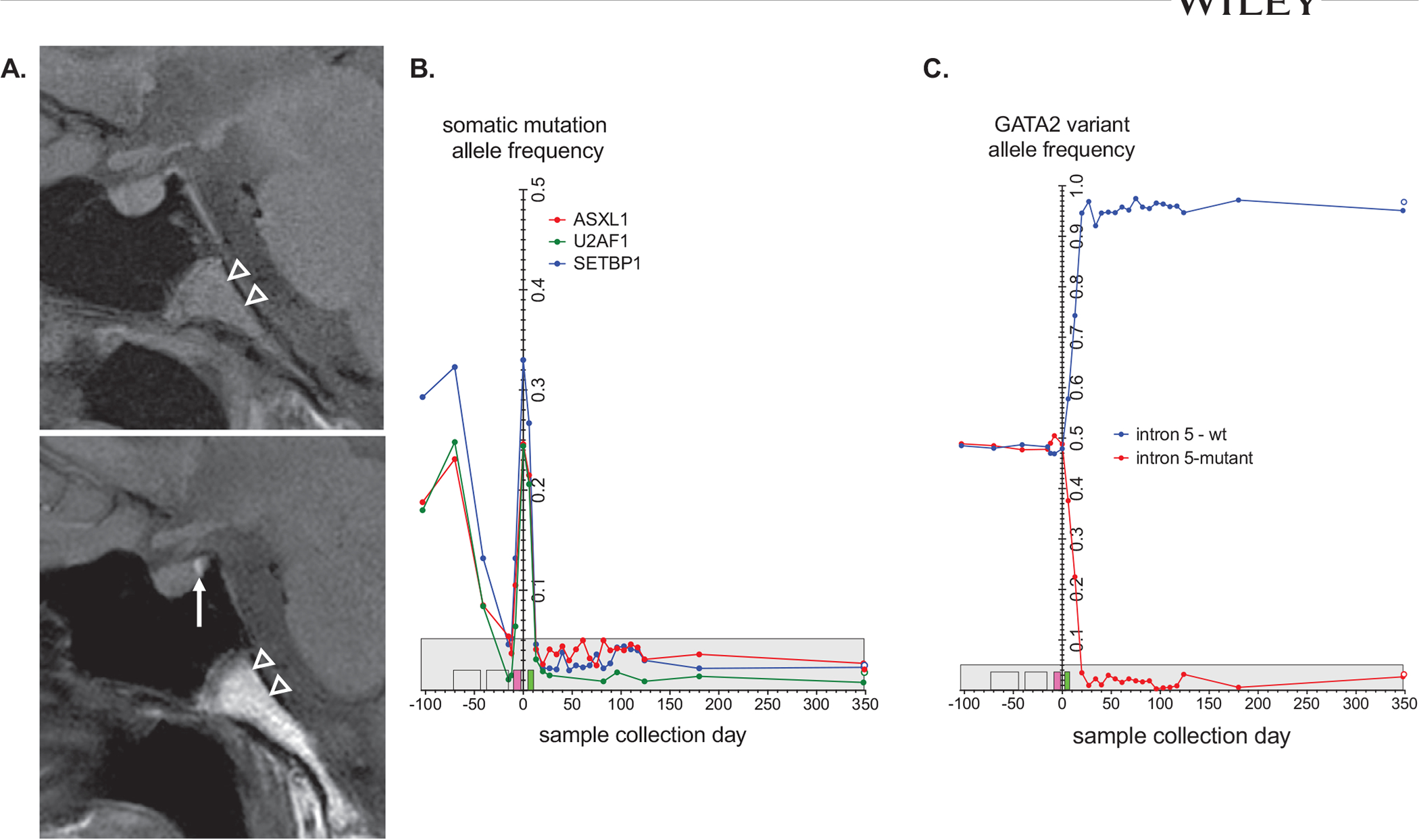

Concurrent evaluation of polydipsia and polyuria led to diagnosis of coexisting central DI (Table S3). Central nervous system evaluation identified 11% atypical myeloid cells consistent with CMML in the cerebrospinal fluid, as well as absence of a normal T1 posterior pituitary bright spot on initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is a characteristic finding in central DI and has been described previously in cases of malignancy-associated central DI (Figure 2A).4 His DI was effectively managed with desmopressin (DDAVP).

FIGURE 2.

Clinical course illustrating variant allele frequency (VAF) and central nervous system response to therapy. A, Initial pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing absence of the T1 posterior pituitary bright spot with reappearance of the signal (white arrow) on MRI (L). Follow-up MRI obtained 6 months after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Increased T1 signal in the visualized portion of the clivus (arrowheads) reflects fat marrow signal consistent with decreased bone marrow cellularity. B, VAF detected by direct DNA sequencing versus time of sample collection for ASXL1, SETBP1, and U2AF1 in peripheral and bone marrow samples. C, VAF for the normal (blue) and GATA2 intronic mutation (red) alleles in peripheral and bone marrow samples. VAFs are plotted against the sample collection day relative to bone marrow transplant (day 0). The days for decitabine-venetoclax treatments (yellow), busulfan conditioning (pink), and cytoxan treatment (green) are indicated by boxes on the x-axis. The maximum VAF background signal from control samples is indicated by the gray box. A 1-year post-BMT bone marrow sample is indicated by the open circles

Given his proliferative CMML with 6% circulating blasts and multiple high-risk features (germline GATA2 mutation, monosomy 7, and ASXL1 mutation), proceeding expeditiously to HSCT was imperative. Decitabine and venetoclax were initiated to stabilize and prevent progression to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) while donor options were evaluated. He received decitabine 20 mg/m2 (days 1–5) and daily venetoclax 400 mg following a dose-escalation over the first week for a 28-day cycle.5 He received two cycles of therapy with decreasing detection of ASXL1, SETBP1, and U2AF1 with each cycle (Figure 2B,C). A bone marrow biopsy following two cycles showed a reduction in his blasts to 3–4% with uniform persistence of monosomy 7. He tolerated the regimen well with no evidence for tumor lysis or transaminitis, but course was complicated by nausea responsive to antiemetics, grade 4 neutropenia, grade 2 anemia (CTCAE v 4), and mild thrombocytopenia.

Without an available matched sibling or unrelated donor, he proceeded to a myeloablative, haploidentical peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) transplant on an NIH trial for transplantation of GATA2 deficiency (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01861106).6 The patient’s maternal cousin was chosen as his haplo-donor (GATA2 negative). Due to high-risk disease, PBSC was chosen over marrow to provide an enhanced graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.7 By day +15 post-HSCT, his polyuria and polydipsia had fully resolved and DDAVP was permanently discontinued. MRI imaging showed reappearance of the T1 posterior pituitary bright spot (Figure 2A). Day +30 peripheral blood chimerism showed 100% donor CD3/myeloid with no immunophenotypic evidence of CMML, and concurrent bone marrow evaluation showed no evidence of MDS or CMML I (Figure 1E–H). His transplant was complicated by development of acute graft-versus-host disease with subsequent development of chronic graft-versus-host disease. He remains in remission with normal cytogenetics 1 year post-HSCT (Figure 1C,D). This case report is based on enrollment on two Institutional Review Board approved clinical trials and standard clinical care.

Central DI as a presentation for myeloid malignancies is exceedingly rare.4 The pathophysiology linking myeloid leukemia to central DI is unknown, but disruption of the hypothalamo-neurohypophyseal system secondary to leukemic infiltration, autoimmune hypophysitis, leukostasis, thrombosis, fibrosis, and/or hemorrhage have been postulated.8–10 As in our case, monosomy 7-associated central DI has generally been reversible following complete remission and HSCT.

Although pediatric MDS is rare, germline GATA2 mutations represent the most common predisposing etiology, and are identified in 72% of adolescent patients presenting with MDS and monosomy 7.11 GATA2 is a zinc finger transcription factor essential for normal hematopoiesis that when disrupted leads to predisposition for development of dysplasia with subsequent MDS/myeloid leukemia transformation, likely secondary to hematopoietic stem cell loss, bone marrow stress, and clonal evolution.12–14 In addition to germline GATA2 deficiency, our patient also had a mutation in ASXL1, which occurs in 80% of patients with GATA2 deficiency who develop MDS, in particular CMML. His specific ASXL1 mutation, p.646Wfs*12, is the most common variant reported in GATA2 deficiency.15 ASXL1 mutation is also an independent, negative prognostic factor associated with rapid progression to AML and frequently co-occurs with SETBP1 and U2AF1, as seen in our patient.3,15,16

While the diagnosis of de novo CMML is rare in adolescents, CMML is not uncommon in GATA2 deficiency and may present much earlier than in sporadic CMML cases. In this case, based on the hematologic findings (Figure 1A–D), the differential diagnosis of CMML versus MDS/MPN was discussed. Given the underlying germline GATA2 mutation, which provided an explanation for a predilection to CMML, and manifestations which were consistent with other cases of CMML we have seen in our GATA2 patient cohort, this case illustrates the unique presentation of CMML in an adolescent. The diagnosis of MDS-EB (excess blasts) was not felt to be appropriate, given the myeloproliferative component of the patient’s disease.

Outcomes for adults with CMML with high-risk cytogenetics (eg, monosomy 7) are particularly poor due to risk of transformation to AML, resulting in a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 4%.1,3 Allogeneic SCT is the only established cure for both GATA2 deficiency6,17–19 and CMML.20 In younger patients with high-risk CMML, earlier consideration of HSCT is recommended.2,3,21 In contrast to adult populations in whom the 5-year OS from the time of transplant for high-risk CMML is 18%, GATA2-deficient pediatric patients who have undergone HSCT for monosomy 7 MDS, including CMML, have fared far better with a 5-year OS of 66%. This is likely secondary to younger age, decreased comorbidities, and lower rate of transplant-related complications.20,22

The benefit of pre-HSCT cytoreductive therapy for CMML remains controversial and a standard approach is not well established (Table S4).20,23 Cytoreduction may be of benefit when blast cells are greater than 10% and for patients with high-risk CMML.1 In our case, because of his high-risk features and unknown donor options at the time of CMML diagnosis, the decision was made to initiate therapy to prevent progression prior to HSCT. Although standard AML induction was considered, ultimately we chose a more well-tolerated regimen with evidence of activity and tolerance in pediatric AML.24,25 Based on preclinical synergy, hypomethylating agents combined with venetoclax, a small molecular inhibitor of the BCL-2 protein,26,27 has been shown to be well tolerated in AML.1,28–31 Our patient tolerated this regimen and achieved disease stabilization, effectively bridging him to HSCT. Furthermore, the variant allele frequency (VAF) for ASXL1, SETBP1, and U2AF1 also decreased with decitabine and venetoclax, suggesting that all malignant clones were similarly sensitive to these drugs (Figure 1I). Upon achieving 100% donor chimerism following his myeloablative PBSCT, his germline heterozygous GATA2 mutation was corrected to a fully normal allele on genotyping (Figure 1J).

In summary, we report on the rare presentation of monosomy 7 CMML in an adolescent with a germline GATA2 mutation who presented with central DI. Allogeneic HSCT for treatment of GATA2 and CMML led to resolution of central DI and restoration of normal hematopoiesis. Decitabine and venetoclax were effective and well tolerated as a bridge to HSCT, providing insights into the treatment approach for high-risk CMML.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs Elliot Stieglitz and Amy DeZern for their input on their approaches for the treatment of CMML. We would also like to thank the patient and his family for providing consent for publication of this report.

Abbreviations:

- AML

acute myelogenous leukemia

- CMML

chronic myelomonocytic leukemia

- DDAVP

desmopressin

- DI

diabetes insipidus

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- MDS

myelodysplastic syndrome

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Cancer Institute, and NIH Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Solary E, Itzykson R. How I treat chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;130(2):126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patnaik MM, Wassie EA, Padron E, et al. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in younger patients: molecular and cytogenetic predictors of survival and treatment outcome. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;95(1):97–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladigan S, Mika T, Figge A, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with central diabetes insipidus. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2019;76:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiNardo CD, Pratz KW, Letai A, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of venetoclax with decitabine or azacitidine in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukaemia: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(2):216–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parta M, Shah NN, Baird K, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for GATA2 deficiency using a busulfan-based regimen. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(6):1250–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne M, Savani BN, Mohty M, Nagler A. Peripheral blood stem cell versus bone marrow transplantation: a perspective from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2016;44(7):567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surapolchai P, Ha SY, Chan GC, et al. Central diabetes insipidus: an unusual complication in a child with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and monosomy 7. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(2):e84–e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron M, Maloum K, Roos-Weil D. Central diabetes insipidus revealing neuromeningeal localization of chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2014;164(3):314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Chapelle A, Lahtinen R. Monosomy 7 predisposes to diabetes insipidus in leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Eur J Haematol. 1987;39(5):404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wlodarski MW, Hirabayashi S, Pastor V, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of GATA2-related myelodysplastic syndromes in children and adolescents. Blood. 2016;127(11):1387–1397. quiz 1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu AP, McReynolds LJ, Holland SM. GATA2 deficiency. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15(1):104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McReynolds LJ, Calvo KR, Holland SM. Germline GATA2 mutation and bone marrow failure. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32(4):713–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spinner MA, Sanchez LA, Hsu AP, et al. GATA2 deficiency: a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity. Blood. 2014;123(6):809–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West RR, Hsu AP, Holland SM, Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Hickstein DD. Acquired ASXL1 mutations are common in patients with inherited GATA2 mutations and correlate with myeloid transformation. Haematologica. 2014;99(2):276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valent P, Orazi A, Savona MR, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for classical chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), CMML variants and pre-CMML conditions. Haematologica. 2019;104(10):1935–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Gea-Banacloche J, Freeman AF, et al. Successful allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for GATA2 deficiency. Blood. 2011;118(13):3715–3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman AF. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in primary immunodeficiencies beyond severe combined immunodeficiency. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018;7(suppl_2):S79–S82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickstein D HSCT for GATA2 deficiency across the pond. Blood. 2018;131(12):1272–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu HD, Ahn KW, Hu ZH, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(5):767–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Symeonidis A, van Biezen A, de Wreede L, et al. Achievement of complete remission predicts outcome of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. A study of the Chronic Malignancies Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2015;171(2):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirabayashi S, Wlodarski MW, Kozyra E, Niemeyer CM. Heterogeneity of GATA2-related myeloid neoplasms. Int J Hematol. 2017;106(2):175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kongtim P, Popat U, Jimenez A, et al. Treatment with hypomethylating agents before allogeneic stem cell transplant improves progression-free survival for patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Place AE, Goldsmith K, Bourquin JP, et al. Accelerating drug development in pediatric cancer: a novel Phase I study design of venetoclax in relapsed/refractory malignancies. Future Oncol. 2018;14(21):2115–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karol SE, Alexander TB, Budhraja A, et al. Venetoclax in combination with cytarabine with or without idarubicin in children with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia: a phase 1, dose-escalation study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):551–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bogenberger JM, Delman D, Hansen N, et al. Ex vivo activity of BCL-2 family inhibitors ABT-199 and ABT-737 combined with 5-azacytidine in myeloid malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(1):226–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsao T, Shi Y, Kornblau S, et al. Concomitant inhibition of DNA methyltransferase and BCL-2 protein function synergistically induce mitochondrial apoptosis in acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(12):1861–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alfonso A, Montalban-Bravo G, Takahashi K, et al. Natural history of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia treated with hypomethylating agents. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(7):599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun T, Itzykson R, Renneville A, et al. Molecular predictors of response to decitabine in advanced chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a phase 2 trial. Blood. 2011;118(14):3824–3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(1):52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tantravahi SK, Szankasi P, Khorashad JS, et al. A phase II study of the efficacy, safety, and determinants of response to 5-azacitidine (Vidaza) in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(10):2441–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.