Abstract

A p-nitrophenol (PNP) degrading halotolerant, Gram-variable bacterial strain designated as DNPG3, was isolated from a water sample collected from the river Ganges in Hooghly, West Bengal (WB), India, by enrichment culture technique. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis (carried out at EzTaxon server and Ribosomal data base project site), the strain DNPG3 was identified as Brachybacterium sp., with B. zhongshanense strain JBT (97.08% identity) as it is nearest phylogenetic relative. The strain could tolerate up to 3 mM of PNP, while the optimal growth for the strain was recorded as 0.25 mM. The strain could carry out biodegradation of PNP with concomitant release of nitrite and p-benzoquinone (PBQ) was detected as a hydrolysis product. Under the catabolic condition, it could carry out 36% biodegradation of PNP within 144 h, while, under co-metabolic condition (with glucose), 100% biodegradation was achieved within 48 h at 30 °C. Calcium alginate bead-based cell immobilization studies (of the strain DNPG3) indicated complete biodegradation of PNP (under catabolic condition) within 26 h. This is the first report of PNP biodegradation by any representative strain of the genus Brachybacterium. The study definitely indicated that Brachybacterium sp. strain DNPG3 has biotechnological potential and the strain may be a suitable candidate for developing clean, green, eco-friendly, cost-effective bioremediation processes towards effective removal of PNP from the contaminated sites.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-022-03263-7.

Keywords: Biodegradation, Brachybacterium, Ca-alginate beads, Cell immobilization, p-nitrophenol, 16S rRNA gene

Introduction

PNP is one of the well-documented priority pollutants (USEPA 1980) which is extensively used in petrochemical, pharmaceutical, dye, explosives, pesticides, agrochemical, and leather industries (Spain 1995). In agro-ecosystems, it is also produced by hydrolysis of agrochemicals (mainly organophosphates) and its persistent presence has been documented from soil and water ecosystems (Kuang et al. 2020). Due to its water solubility and stability, it is considered as highly mobile and contaminates the drinking water sources (rivers, lakes, ponds, etc.), and causes water pollution (Samuel et al. 2014; Kuang et al. 2020). It is highly toxic and is known to have carcinogenic as well as mutagenic effects on living organisms like a human and several animal models (Vikram et al. 2013; Samuel et al. 2014). It is reported to have a deleterious effect on the environment (Samuel et al. 2014) and its maximum permissible limit is documented to be 10 ng/ml (Kulkarni and Chaudhari 2006a; 2006b).

River Ganges is one of the major rivers of India which not only provides fresh water for consumption but is also a source of livelihood for the human population living along its bank (Ghirardelli et al. 2021). Over the past few decades, several industries (petrochemical, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, paints, tannery, etc.) have come up along the Gangetic Plain (Roy and Shamim 2020). Major wastes from these industries are also disposed off in the river Ganges (Ghirardelli et al. 2021). Although no report regarding residue level of PNP in Ganges water was documented in literature, the same for several pesticides, phenolics, heavy metals, etc. was reported from time to time by various authors (Sarker et al. 2021; Paul 2017). Contamination of river water by PNP has been reported from El Harrach river near Algeria (Löser et al. 1998); river sediment in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Gemini et al. 2005); River Dene, Warwickshire, England (Kowalczyk et al. 2015); Huai river, Hai river; Yellow river of China (Kuang et al. 2020). Thus, it is surmised that PNP, being one of the most extensively used chemicals, might have also contaminated Ganges water, as well.

Recent reports from medical studies indicated the role of PNP in the dysfunction of the liver, kidney, and other important physiological life processes of animals (Kuang et al. 2020). The LD50 value for Danio rerio and Larimichthys crocea reference is reported to be 35 mg/L and 6.2 mg/L, respectively (USEPA 1980; Kuang et al. 2020).

Therefore, the presence of excess PNP in the environment is of huge public concern and the search for suitable clean-up techniques/approaches for its effective removal is essential. Although several physical, chemical, physicochemical, and electrochemical methods have been proposed, bioremediation approaches mainly involving bacteria are considered as the best (Jaiswal and Shukla 2020). The latter provides a green, clean, eco-friendly, cost-effective method. Moreover, bacteria and their catalytic enzymes are shown to be remarkably versatile, specific, highly stable, and active even in extremely harsh conditions (Abhilash and Singh 2009). Members of several bacterial genera are already reported to have PNP degradation properties. Some bacterial genera whose members are reported to be involved in PNP biodegradation include Moraxella (Spain and Gibson 1991), Sphingomonas (Alber et al. 2000), Nocardioides (Cho et al. 2000), Arthrobacter (Chauhan et al. 2000), Brevibacterium (Ningthoujam 2005), Serratia (Pakala et al. 2007), Ochrobactrum (Qiu et al. 2007), Achromobacter (Wan et al. 2007), Rhodococcus (Ghosh et al. 2010; Sengupta et al. 2019), Citricoccus (Nielsen et al. 2011), Bacillus (Arora 2012), Sphingobacterium (Samson et al. 2019). However, considering the mammoth diversity of bacteria on Earth, searching for novel bacterial strains having PNP degradation potential is a systematic way towards finding novel enzyme system/gene pool for better biotechnological interventions and understanding of molecular mechanisms of biodegradation of PNP. Immobilized microbial cells have been considered superior (over the free suspension of cells) for environmental clean-up processes due to the reusable nature of immobilized cells, high enzyme productivity, conservation of catalytic activity for longer durations of time, and better applicability (Fernández-López et al. 2017). This has already been documented for halophilic exochitinase enzyme production (Esawy et al. 2016), biodegradation of hydrocarbons (Dellagnezze et al. 2016), phenols (Ahmad et al. 2012; Mohanty and Jena 2017; Felshia et al. 2017), and methyl parathion (Fernández-López et al. 2017). Application of immobilized bacterial cells for catabolic biodegradation of PNP has scarcely been documented in the literature and the presence of any strains of bacteria belonging to the genus Brachybacterium has ever been reported. However, co-metabolic degradation of phenol and PNP has been reported by Loofa-immobilized cells of Ralstonia eutropha (Maleki et al. 2015).

In the present manuscript, we report, for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, the biodegradation of PNP by an aquatic strain of Brachybacterium sp. isolated from a water sample collected from the river Ganges of West Bengal, India.

Materials and methods

All the chemicals used for microbiology (i.e., growth media, media supplements, growth supplements, general chemical, etc.,) were of AR grade and purchased from Himedia, India. All the solvents were of HPLC grade, purchased from Merck and Spectrochem, India. Molecular biology reagents were purchased from HiMedia, India. PNP and its degradation intermediates were from Sigma and were of highest purity grade.

Sample collection, bacterial enrichment, and isolation

Water samples were collected in sterile, Shot Duran bottles from river Ganges near Chinsura, Hooghly, WB, India (Lat-23˚52′59″ N, Long-88˚24′05″ E). Isolation of PNP degrading bacterial strain was carried out by enrichment culture on minimal medium (MM consisting of Na2HPO4-4.0 g; (NH4)2SO4-0.8 g; KH2PO4-2.0 g; MgSO4.7H2O-0.8 g; trace element solution-1 ml; trace element solution (10×): KI-0.05 g, Al (OH)3-0.10 g, LiCl-0.05 g, MgSO4.7H2O-0.08 g, BaCl2.2H2O-0.05 g, H3BO3-0.05 g, ZnSO4.7H2O-0.10 g, CoCl2.6H2O-0.01 g, SnCl2.2H2O-0.05 g, NiCl2.6H2O-0.01 g, (NH4)Mo7O4.4H2O-0.05 g, FeSO4-0.02 g, CaSO4-0.02 g, dH2O-100 ml; (0.1 ml trace element solution (10×) was added to 1L of minimal media before autoclaving) supplemented with 0.25 mM PNP or DNP (2, 4-dinitrophenol) as sole source of Carbon. Basal MM was solidified with 1.5% agar whenever needed (Prakash et al. 1996).

Identification of PNP degrading bacterial strain

Phenotypic characterization of the strain was carried out according to Smibert and Krieg (1994). For the identification of bacterium, a 16S rRNA gene-based molecular phylogenetic approach was used. Genomic DNA was isolated according to Pitcher et al. (1989). Two universal primers specific for bacterial 16S rRNA gene, namely 27f (5ʹ AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG 3ʹ) and 1492r (5ʹ TCA GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T 3ʹ) were used for amplification reaction from the genomic DNA of the bacterial isolates. Amplification reaction, PCR cycle parameters, and sequencing reactions (two; 27f and 1492r) were carried out according to Saha and Chakrabarti (2006); Ibrahim (2016). To determine phylogenetic affinity (near neighbors and Pairwise sequence identity) BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), EzTaxon server (Yoon et al. 2017; https://www.ezbiocloud.net/), and Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) release 11 (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/index.jsp) (Cole et al. 2014) were used. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA (Version, 11; Tamura et al. 2021).

Inoculum preparation for growth and PNP biodegradation studies

Fresh bacterial biomass (with viable count ~ 1 × 107 CFU/ml) was harvested from overnight grown (on Tryptic soy broth, TSB) culture of strain DNPG3, washed twice with minimal media, and used as inoculum for growth and biodegradation studies. Ability of the bacterial strain to grow on PNP was determined by its comparative account of growth on different medium, viz, MM + 0.3 mM PNP + 0.2% Glucose; MM + 0.25 mM DNP + 0.2% Glucose; MM + Glucose (0.5%), TSB and R2A at 30 °C (optimal growth temperature) in an orbital shaker BOD incubator (with 120 rpm). Growth was monitored spectrophotometrically using a Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) at 600 nm at every 6 h time interval. Growth was also monitored by the viable count method wherever necessary.

Determination of MIC of Brachybacterium sp strain DNPG3

Bacterial cells of the strain DNPG3 were harvested after growing on TSB broth, washed twice by Minimal media (MM) and suspended in 1 ml MM. Fixed number of cells 3.2 × 106 were inoculated for MIC (0.25 to 4 mM PNP with 0.25 mM of an interval). Cells were incubated for 48 h at 30˚C, 120 rpm. CFU counts were recorded on 0.25 mM PNP agar plate by a dilution plating method. MIC was determined as PNP concentration where the least CFU counts were detected. All the experimental sets were performed in triplicate and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for the CFU counts, as reported earlier.

PNP biodegradation study

To study PNP biodegradation by the strain DNPG3, freshly prepared culture inoculum (representing 1 × 107 cells/ml) was inoculated in MM broth supplemented with 0.25 mM PNP. A control set was also set exactly the same way without any inoculum. The PNP biodegradation by the strain DNPG3 with concomitant release of nitrite was monitored spectrophotometrically using a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) at every 6 h time interval. Monitoring of PNP biodegradation was carried out by estimating the residual concentration of PNP (with respect to incubation time) in the test versus control set by comparing against a standard curve as already reported by Sengupta et al. (2015). The result was expressed as a percentage of degradation with respect to time (Sengupta et al. 2015).

PNP biodegradation study using immobilized bacterial cells in calcium alginate beads

Freshly growing cells (on TSB for overnight at conditions mentioned earlier) of strain DNPG3 were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 g for 5 min, washed twice with MM, resuspended in 20 ml of MM, mixed with 20 ml of 3% sodium alginate in the ratios 1:1 (v/v) thereby producing 40 ml of 1.5% sodium alginate (this was recorded to be optimal) containing bacteria (with a viable count of 2 × 1010 CFU /ml). The mixture was stirred well for 5 min and then filled into the 20 ml sterile syringe; dispended dropwise into the stirred solution of 0.2 M CaCl2. The calcium alginate beads generated in this way were harvested carefully and allowed to solidify at room temperature for 60 min (Zommere and Nikolajeva 2017). For PNP biodegradation experiment with immobilized cells, 25 beads (each having a viable count of 1 × 107 CFU/ml) were inoculated into MM supplemented with 0.25 mM PNP (optimum concentration). Control flasks were prepared exactly in the same without bacteria impregnated Ca-alginate beads. PNP depletion and nitrite release were monitored at 6 h of intervals, using a spectrophotometer as mentioned earlier. Analyses of hydrolysis intermediates, during biodegradation of PNP, were carried out by thin-layer chromatography following Sengupta et al. (2015).

Nitrite release test

Release of nitrite during the course of biodegradation of PNP was determined periodically after every 6 h of interval spectrophotometrically using the method of White et al. (1996) (also by Ghosh et al. 2010). For this, an equal volume of reagent A (0.1% w/v, N-ethylene diamine dihydrochloride in 30% v/v acetic acid) was added to culture supernatants. After 2 min, an equal volume of reagent B (0.1% w/v, sulfanilic acid in 30%, v/v acetic acid) was added and incubated for 30 min. The appearance of purple color indicated the release of nitrite ions which was quantified by measuring absorbance at 540 nm, against the standard curve of NaNO2.

Results and discussion

Isolation of PNP degrading bacterial strain

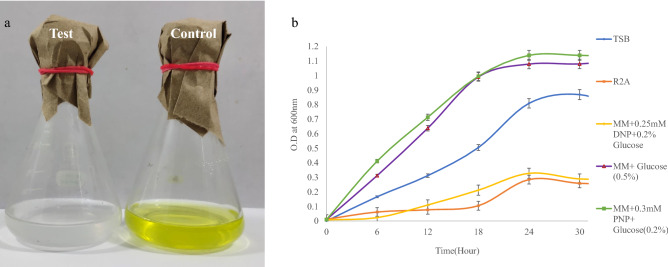

During the course of the study, initiated in 2018, several aquatic bacterial strains were isolated from River Ganges water samples by enrichment culture using PNP and DNP as the sole source of carbon. Overall aim was to isolate efficient strains engaged in biodegradation of PNP and DNP for bioremediation purposes. The strain DNPG3 was isolated by enrichment culture technique using DNP as the sole source of carbon, from a water sample collected from the river Ganges. Initial growth-based studies indicated that the strain DNPG3 could decolorize the yellow color of 0.3 mM PNP within 48 h of growth at 30 °C (Fig. 1a, b). The strain could tolerate up to 3 mM of PNP, while the optimal growth for the strain was recorded with 0.25 mM of PNP. Survey of literature suggested soil as main source for isolation of PNP degrading bacterium like—Ghosh et al. (2010) isolated Rhodococcus imtechensis RKJ300 from soil of Panjab; Arora (2012) isolated PNP degrading bacterium Arthrobacter sp. SPG from pesticide contaminated soils of Hyderabad, Sengupta et al. (2019) isolated R. rhodochrous BUPNP1 from landfill soil of Burdwan. But reports of PNP degrading aquatic bacterium isolated from river water were scanty, in literature. In one report, bacterium R. wratislaviensis was isolated from river sediment in Buenos Aires (Argentina) by Gemini et al. (2005). Data for tolerance limit of PNP among the aquatic bacteria are lacking in literature and most of the data are from soil bacteria.

Fig. 1.

a Growth of strain DNPG3 on MM supplemented with 0.25 mM PNP and 0.2% glucose, showing complete decolorization (and degradation) of PNP. Yellow color is the control set showing no decolorization (and no degradation). b Comparative growth curves of strain DNPG3 on different media

Characterization and identification of the PNP degrading bacterium

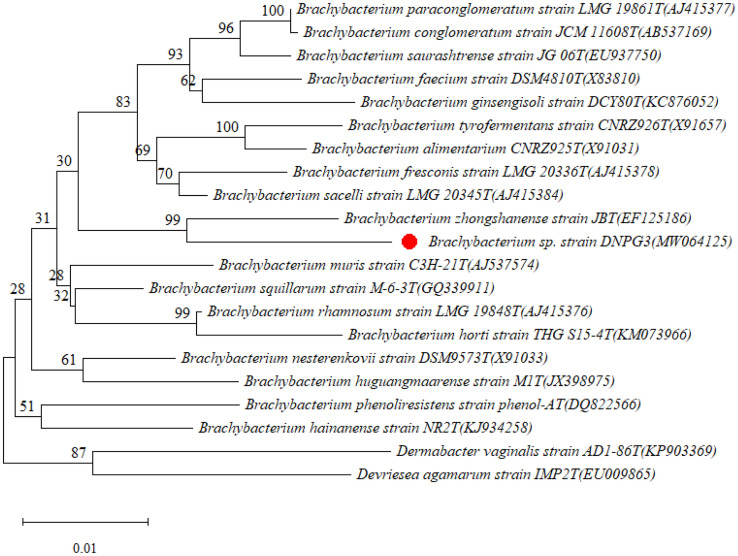

The aquatic bacterial strain designated DNPG3 was Gram variable, motile, having oxidative metabolism for glucose. Its comparative phenotypic characteristics (with close phylogenetic relatives) are summarized in Table 1. Initial, BLAST analysis (carried out at NCBI database www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) based on 16S rRNA gene sequence indicated, strain DNPG4 (another bacterium isolated from the same sample by our group) to be its closest relative (with 98.45% identity) followed by Brachybacterium sp. strain MBBJ (with 98.37%; isolated from the alimentary canal of Longicorn beetle) and an uncultured bacterial clone X3-26 (97.56%; from pile fermentation of Pu-erh tea by culture-independent approach (both unpublished reports gathered from NCBI database). While, among type strains, Brachybacterium zhongshanense strain JBT was determined to be the nearest relative of the strain DNPG3 with 97.08% of identity, followed by B. muris strain C3H-21T (96.65% of identity), B. squillarum strain M-6-3T(96.42% of identity) and B. horti strain THG S15-4T (96.38% of identity), respectively, at EzTaxon server, which is currently considered a useful server for predicting the phylogenetic affiliation of bacterial strains, since it carries out the comparison (of 16S rRNA genes) with type strains (Yoon et al. 2017). Similar conclusions were also recorded from analyses carried out using online tool (SeqMatch) available at RDP (Release 11). From the phylogenetic tree prepared with the type strain of closely related species within the genus Brachybacterium it was evident that the strain DNPG3 together with Brachybacterium zhongshanense formed a well-defined cluster and was placed in between the two clusters represented by B. paraconglomeratum—B. sacelli and B. muris–B. horti (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Differentiating characteristics of strain DNPG3 and its close phylogenetic relatives

| Phenotypic characters | Brachybacterium sp. strain DNPG3 | B. sp. strain DNPG4 | B. Zhongshanense strain JBT | B. muris strain C3H-21T | B. squillarum strain M-6-3T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rDNA % identity with DNPG3 |

98.44 | 97.08 | 96.65 | 96.42 | |

| Gram’s reaction | Variable | Variable | + | + | + |

| Oxidase activity | – | + | – | – | – |

| Growth with 5% NaCl | + | + | + | + | – |

| Motility | + | + | ND | – | – |

| Starch hydrolysis | + | + | – | + | – |

| Cellulose hydrolysis | – | – | + | – | – |

| H2S production | – | – | ND | – | ND |

| Optimum temperature | 30 ℃ | 30 ℃ | 30 ℃ | 30 ℃ | 20–25 ℃ |

| Catalase activity | + | + | + | + | – |

| MR test | + | + | ND | ND | ND |

| Citrate utilization | – | + | ND | ND | ND |

| Habitat | River Ganges water | River Ganges water | The sediment of Qijiang river, Zhongshan city, China | Liver of laboratory mouse | Salt-fermented seafood in Korea |

| Acid production from | |||||

| D-Glucose | + | + | + | – | – |

| D-Xylose | + | + | ND | – | ND |

| D-Mannose | + | + | + | + | – |

| L-arabinose | + | + | + | – | – |

| D-melibiose | + | + | + | – | – |

( +), positive, (−), negative, ND data not reported

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis showing the relative position of strain DNPG3 with various type strains of genus Brachybacterium. Number at nodes indicated bootstrap values of 1000 replications. The accession numbers are shown in brackets and the type strains are indicated with letters “T”. Bar 0.01 substitutions per site. The sequence of Dermabacter vaginalis strain AD1-86 T and Devriesea agamarum strain IMP2T were used as outgroup

Currently, the golden standard for prokaryotic species is dependent on the criteria of overall genome relatedness value (cut-off values being greater than and equal to 70%; Wayne et al. 1987). At this level, 16S rRNA gene sequence identity values have recently been deduced to be 98.65 by Kim et al. (2014), replacing the earlier long-time well-accepted threshold identity value of 97% (Stackebrandt and Goebel 1994). Since the strain DNPG3 showed a lower 16S rRNA gene sequence identity value (97.08% compared to the recent threshold value of 98.65%) with its closest type strain (JBT representing Brachybacterium Zhongshanense), the strain DNPG3 is possibly a novel species of Brachybacterium. However, in the absence of overall genome relatedness values, and detailed polyphasic taxonomic characterization, the strain was identified as Brachybacterium sp. pending the further taxonomic conclusion of its possible novel species status.

The strain DNPG3 was deposited at MTCC, IMTECH Chandigarh with MTCC13125 as its strain accession number, and its 16S rRNA gene sequence is available at GenBank (with accession number MW064125). Currently, the genus Brachybacterium is represented by 27 species (LPSN; https://www.bacterio.net/) (Parte et al. 2020). Members of this genus are mainly reported from cheeses (Schubert et al. 1996), liver of laboratory mouse (Buczolits et al. 2003), seawater (Kaur et al. 2016), and soil habitats (Singh et al. 2016). Till date, only one strain (namely Brachybacterium phenoliresistens) is reported to be involved in xenobiotics resistance (Chou et al. 2007) and there is no report of PNP biodegradation by any strain of Brachybacterium sp. to the best of our knowledge. It seems that the known members of the genus Brachybacterium are not usually equipped with xenobiotics degradation machinery; however, the discovery of the new strain DNPG3 and its genomics studies (which are under our future aim) might provide some hints or hunches about the genomic potential of the genus as such.

PNP biodegradation studies by free and immobilized cells

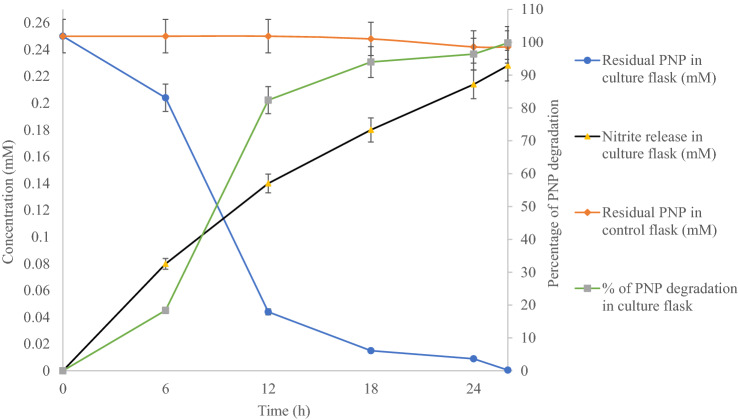

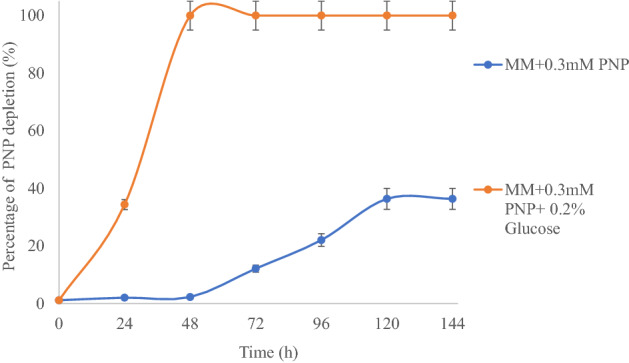

Initial broth-based growth studies indicated the capability of the strain to utilize PNP as the sole source of carbon. However, the growth was much better under co-metabolic conditions (i.e., in the presence of PNP and glucose added together). The strain could degrade up to 36% of 0.3 mM of PNP catabolically within 144 h while under co-metabolic conditions (with glucose) it could degrade 100% of the same within 48 h (Fig. 3) at 30 °C. Similar catabolic biodegradation (0.72 mM PNP within 56 h) for another aquatic bacterium R. wratislaviensis is available in literature (Gemini et al. 2005). Rest of the reports are for soil bacteria, to name few, for example, Leung et al. (1997) reported that Sphingomonas sp. UG30 was capable of mineralizing 22% of 140 µM PNP in the mineral salt-glucose medium, however, no mineralization of PNP was observed in the mineral salt-glutamate medium. Sphingobacterium sp. RB could degrade 70% of 5 mM PNP catabolically within 72 h (Samson et al. 2019).

Fig. 3.

Comparative account of biodegradation of PNP by the strain DNPG3 under catabolic (only PNP) and co-metabolic (PNP + Glucose) growth conditions

Under catabolic growth conditions, the strain DNPG3 showed negligible changes in the OD600 values, so its growth was monitored by the viable count method as well. Since the strain did not show higher growth, an attempt was made to study the PNP biodegradation by employing its immobilized cells. Biodegradation by immobilized microbial cells offers a better option for optimal utilization of microbial bio-resource in a sustainable manner (Fernández-López et al. 2017). Immobilized cells get protection from the harsh environment; microbial cells are released slowly into the medium, getting a chance to overcome stressful environments resulting in efficient biodegradation (Maleki et al. 2015; Dellagnezze et al. 2016). Immobilization also protects cells from competition and predation; it minimizes cell membrane damage (Dellagnezze et al. 2016).

For this, calcium alginate-based beads were impregnated with the strain DNPG3. The characteristic properties of the beads are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. As evident from Fig. 4, under immobilized conditions, the strain DNPG3 could carry out complete biodegradation of 0.25 mM of PNP (indicated by complete decolorization of the yellow color of PNP), catabolically within 26 h (Fig. 4) with concomitant release of nitrite.

Fig. 4.

Study of biodegradation of PNP with concomitant release of nitrite by Ca-alginate immobilized cells of the strain DNPG3

The control set (only Ca-alginate beads with no bacterial cells) showed no change in the residual amount of PNP, thereby indicating the role of immobilized cells in the biodegradation of PNP. To check the effect of Ca-alginate on the growth of bacteria, the growth response of the strain towards Ca-alginate was studied by the viable count method. It indicated that the strain could not utilize Ca-alginate for growth and its viable count decreased during incubation time (data not shown). Similar immobilization-based biodegradation studies were reported by Heitkamp et al. (1990), where diatomaceous earth was used for immobilization of mixed cultures of Pseudomonas (designated PNP1, PNP2, and PNP3) for removing PNP in aqueous state, while, recently, Kalaimurugan et al. (2021) reported immobilized (using gum arabic) Pseudomonas sp. YPS3 for efficient biodegradation of PNP at 37 °C.

The statistical parameters tested were correlation coefficient between time and percentage of PNP degradation by the strain DNPG3 (under immobilized condition). The correlation coefficient value was determined to be 0.8597. When the same values were tested for paired t test, the value of t test was p < 0.01. This indicated that the correlation value was strongly significant.

The study of hydrolytic intermediates during PNP biodegradation indicated the presence of PBQ only. No other intermediates could be detected through thin layered chromatographic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the present study, since, only PBQ was detected as a hydrolysis product, the possible pathway for biodegradation of PNP through PBQ by the strain DNPG3 is proposed (Supplementary Fig. 4). Survey of the literature indicated the existence of two pathways for microbial biodegradation of PNP (Kitagawa et al. 2004; Vikram et al. 2013). The first pathway was through PBQ formation, (usually common among Gram negative bacteria) (Prakash et al. 1996; Arora 2012) and the second was through the formation of 4-nitrocatechol (4NC) as the first hydrolysis intermediate product (usually common among Gram positive bacteria) (Ghosh et al. 2010; Sengupta et al. 2019). In some bacteria (Burkholderia sp. strain SJ 98, Pseudomonas sp. 1–7) both these pathways have been reported to be operative and so, both 4NC and PBQ were detected as intermediates (Zhang et al. 2012; Vikram et al. 2013).

The present study establishes the biodegradation of PNP by a representative member of the genus Brachybacterium, previously unknown to the scientific community, to the best of our knowledge.

Conclusion

A Gram-variable bacterial strain designated as DNPG3 was isolated (by enrichmnt culture, using PNP as sole source of carbon), from a water sample collected from the river Ganges in Hooghly, WB, India. On the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequence based on molecular phylognetic analyses, the strain was identified as Brachybacterium sp. Biodegradation of PNP by the strain DNPG3 was better (100% within 48 h at 30 °C) under co-metabolic conditions (in the presence of 0.2% of glucose) compared to catabolic conditions (36% within 144 h at 30 °C). Increase in efficiency of biodegradation of PNP was achieved using immobilized cells with calcium alginate bead (100% degradation of PNP within 26 h at 30 °C). The biodegradation pathway proceeds through the formation of PBQ. This is the first report of PNP biodegradation by any strain belonging to the genus Brachybacterium. Results presented in the manuscript suggested that Brachybacterium sp. strain DNPG3 is a biotechnologically potential, promising strain and it may be used as a candidate for developing an eco-friendly clean-up process for biodegradation of PNP from contaminated aquatic habitats.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Supplementary Fig. 1 Study of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of strain DNPG3 towards various concentrations of PNP, tested in this study (PPT 134 KB)

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Fig. 2 Morphological details of Ca-alginate beads used for immobilization studies (PPT 186 KB)

Supplementary file3 Supplementary Fig. 3 Thin-layer chromatographic (TLC) plate showing hydrolysis intermediates during biodegradation of PNP by the strain DNPG3. From left- Lane 1-4: standards for PNP, 4NC, PBQ and Hydroquinone (HQ); Lane 5, 0 h test sample showing PNP and Lane 5, 144 h test sample showing the presence of PBQ (PPT 197 KB)

Supplementary file4 Supplementary Fig. 4 Proposed pathway of biodegradation of PNP by the strain DNPG3, isolated in this study (PPT 96 KB)

Supplementary file5 Supplementary Table 1 Characteristic features of bacterial whole-cell immobilized Ca-alginate beads used in this study. Abbreviations: CFU, Colony forming Units (DOC 28 KB)

Acknowledgements

The authors thankfully acknowledge the infrastructural support provided by the Department of Microbiology, The University of Burdwan, West Bengal, India. We are grateful to Dr. Tapan Chakrabarti, MCC, NCCS, Pune, and Retd. Prof A. K. Paul, Department of Botany, University of Calcutta, Kolkata for useful scientific discussions. Authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Himadri Lahiri, Retd. Professor of English & Culture studies, the University of Burdwan, for critical evaluation of the manuscript. AA also acknowledges the financial support (received during the initial phase of 1 year, from July 2018 to August 2019) from CSIR, Govt. of India (file no.—09/025(0263)/2019). This is BU Micro/PS communication No. 01/2021.

Author contributions

SAA: isolated the bacterial strain, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and reviewed drafts of the paper. PS: conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials, and reviewed drafts of the paper.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Both the authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest connected to the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The manuscript does not involve any work or studies with animal and or human participants performed by any of the authors.

References

- Abhilash PC, Singh N. Pesticide use and application: an Indian scenario. J Hazard Mater. 2009;165:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad SA, Shamaan NA, Arif NM, Koon GB, Shukor MYA, Syed MA. Enhanced phenol degradation by immobilized Acinetobacter sp. strain AQ5NOL 1. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28:347–352. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0826-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alber T, Cassidy MB, Zablotowicz RM, Trevors JT, Lee H. Degradation of p-nitrophenol and pentachlorophenol mixtures by Sphingomonas sp. UG30 in soil perfusion bioreactors. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;25:93–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Bio. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PK. Metabolism of para-nitrophenol in Arthrobacter sp SPG. E3 J Environ Sci Manag. 2012;3:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Buczolits S, Schumann P, Weidler G, Radax C, Busse HJ. Brachybacterium muris sp. nov., isolated from the liver of a laboratory mouse strain. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:1955–1960. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02728-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Chakraborti AK, Jain RK. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol and 4-nitrocatechol by Arthrobacter protophormiae. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2000;270:733–740. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YG, Rhee SK, Lee ST. Influence of phenol on biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by freely suspended and immobilized Nocardioides sp. NSP41. Biodegradation. 2000;11:21–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1026512922238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou JH, Lin KY, Lin MC, Sheu SY, Wei YH, Arun AB, Young CC, Chen WM. Brachybacterium phenoliresistens sp. nov., isolated from oil-contaminated coastal sand. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2674–2679. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y, Brown CT, Porras-Alfaro A, Kuske CR, Tiedje JM. Ribosomal database project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:633–642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellagnezze BM, Vasconcellos SP, Angelim AL, Melo VMM, Santisi S, Cappello S, Oliveira VM. Bioaugmentation strategy employing a microbial consortium immobilized in chitosan beads for oil degradation in mesocosm scale. Marin Pollut Bull. 2016;107:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esawy MA, Awad GE, Wahab WAA, Elnashar MM, El-Diwany A, Easa SM, El-Beih FM. Immobilization of halophilic Aspergillus awamori EM66 exochitinase on grafted k-carrageenan-alginate beads. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13205-015-0333-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felshia SC, Karthick NA, Thilagam R, Chandralekha A, Raghavarao KSMS, Gnanamani A. Efficacy of free and encapsulated Bacillus lichenformis strain SL10 on the degradation of phenol: a comparative study of degradation kinetics. J Environ Manag. 2017;197:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López MG, Popoca-Ursino C, Sánchez-Salinas E, Tinoco-Valencia R, Folch-Mallol JL, Dantán-González E, Laura Ortiz-Hernández M. Enhancing methyl parathion degradation by the immobilization of Burkholderia sp. isolated from agricultural soils. Microbiol Open. 2017;6:e00507. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemini VL, Gallego A, De Oliveira VM, Gomez CE, Manfio GP, Korol SE. Biodegradation and detoxification of p-nitrophenol by Rhodococcus wratislaviensis. Int Biodeter Biodegradation. 2005;55:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardelli A, Tarolli P, Rajasekaran MK, Mudbhatkal A, Macklin MG, Masin R. Organic contaminants in Ganga basin: from the green revolution to the emerging concerns of modern India. Iscience. 2021;24:102–122. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Khurana M, Chauhan A, Takeo M, Chakraborti AK, Jain RK. Degradation of 4-nitrophenol, 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol, and 2, 4-dinitrophenol by Rhodococcus imtechensis strain RKJ300. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:1069–1077. doi: 10.1021/es9034123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkamp MA, Camel V, Reuter TJ, Adams WJ. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol in an aqueous waste stream by immobilized bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2967–2973. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim HM. Biodegradation of used engine oil by novel strains of Ochrobactrium anthropi HM-1 and Citrobacter freundii HM-2 isolated from oil-contaminated soil. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0540-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S, Shukla P. Alternative strategies for microbial remediation of pollutants via synthetic biology. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:808. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaimurugan D, Sivasankar P, Durairaj K, Lakshmanamoorthy M, Alharbi SA, Al Yousef SA, Chinnathambi A, Venkatesan S. Novel strategy for biodegradation of 4-nitrophenol by the immobilized cells of Pseudomonas sp. YPS3 with Acacia gum. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G, Kumar N, Mual P, Kumar A, Kumar RM, Mayilraj S. Brachybacterium aquaticum sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from seawater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:4705–4710. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Oh HS, Park SC, Chun J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:346–351. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.059774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa W, Kimura N, Kamagata Y. A novel p-nitrophenol degradation gene cluster from a gram-positive bacterium, Rhodococcus opacus SAO101. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4894–4902. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.4894-4902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk A, Eyice Ö, Schäfer H, Price OR, Finnegan CJ, van Egmond RA, Shaw LJ, Barrett G, Bending GD. Characterization of para-nitrophenol-degrading bacterial communities in river water by using functional markers and stable isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:6890–6900. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01794-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Le Q, Hu J, Wang Y, Yu N, Cao X, Zhang M, Sun Y, Gu W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu H, Yan X. Effects of p-nitrophenol on enzyme activity, histology, and gene expression in Larimichthys crocea. Comp Biochem. 2020;228:108638. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2019.108638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M, Chaudhari A. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by P. putida. Biores Technol. 2006;97:982–988. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M, Chaudhari A. Efficient Pseudomonas putida for degradation of p-nitrophenol. Indian J Biotechnol. 2006;5:411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Leung KT, Tresse O, Errampalli D, Lee H, Trevors JT. Mineralization of p-nitrophenol by pentachlorophenol-degrading Sphingomonas spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;155:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12693.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Löser C, Oubelli MA, Hertel T. Growth kinetics of the 4-nitrophenol degrading strain Pseudomonas putida PNP1. Acta Biotechnol. 1998;18:29–41. doi: 10.1002/abio.370180105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maleki M, Motamedi M, Sedighi M, Zamir SM, Vahabzadeh F. Experimental study and kinetic modeling of cometabolic degradation of phenol and p-nitrophenol by loofa-immobilized Ralstonia eutropha. Biotechnol Biopro Engin. 2015;20:124–130. doi: 10.1007/s12257-014-0593-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty SS, Jena HM. Biodegradation of phenol by free and immobilized cells of a novel Pseudomonas sp. NBM11. Braz J Chem Engin. 2017;34:75–84. doi: 10.1590/0104-6632.20170341s20150388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MB, Kjeldsen KU, Ingvorsen K. Description of Citricoccus nitrophenolicus sp nov, a para-nitrophenol degrading actinobacterium isolated from a wastewater treatment plant and emended description of the genus Citricoccus Altenburger et al 2002. Anton Van Leeuwen. 2011;99:489–499. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ningthoujam D. Isolation and Identification of a Brevibacterium linens strain degrading p-nitrophenol. Afr J Biotechnol. 2005;4:256–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pakala SB, Gorla P, Pinjari AB, Krovidi RK, Baru R, Yanamandra M, Merrick M, Siddavattam D. Biodegradation of methyl parathion and p-nitrophenol: evidence for the presence of a p-nitrophenol 2-hydroxylase in a gram-negative Serratia sp. strain DS001. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;73:1452–1462. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parte AC, Carbasse JS, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M. List of Prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Inter J System Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:5607. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul D. Research on heavy metal pollution of river Ganga: a review. Annal Agrar Sci. 2017;15:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.aasci.2017.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher DG, Saunders NA, Owen RJ. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1989.tb00262.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash D, Chauhan A, Jain RK. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-Nitrophenol by Pseudomonas cepacia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:375–381. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Zhong Q, Li M, Bai W, Li B. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol by methyl parathion-degrading Ochrobactrum sp. B2. Int Biodeter Biodegradation. 2007;59:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Shamim F. Research on the impact of industrial pollution on river Ganga: a review. Int J Pre Ctrl Ind Pollut. 2020;6:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Saha P, Chakrabarti T. Emticicia oligotrophica gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family ‘Flexibacteraceae’, phylum Bacteroidetes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:991–995. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson R, Bodade R, Zinjarde S, Kutty R. A novel Sphingobacterium sp. RB, a rhizosphere isolate degrading para-nitrophenol with substrate specificity towards nitrotoluenes and nitroanilines. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2019 doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnz168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel MS, Sivaramakrishna A, Mehta A. Bioremediation of p-Nitrophenol by Pseudomonas putida 1274 strain. J Environ Heal Sci Engin. 2014;12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/2052-336X-12-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker S, Akbor MA, Nahar A, Hasan M, Islam ARMT, Siddique MAB. Level of pesticides contamination in the major river systems: a review on South Asian countries perspective. Heliyon. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Schubert K, Ludwig W, Springer N, Kroppenstedt RM, Accolas JP, Fiedler F. Two coryneform bacteria isolated from the surface of frenchgruyère and beaufort cheeses are new species of the genus Brachybacterium: Brachybacterium alimentarium sp. nov. and Brachybacterium tyrofermentans sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1996;46:81–87. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta K, Maiti TK, Saha P. Degradation of 4-nitrophenol in presence of heavy metals by a halotolerant Bacillus sp. strain BUPNP2, having plant growth promoting traits. Symbiosis. 2015;65:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s13199-015-0327-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta K, Swain MT, Livingstone PG, Whitworth DE, Saha P. Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics provide a holistic view of 4-nitrophenol degradation and concurrent fatty acid catabolism by Rhodococcus sp. strain BUPNP1. Front Microbiol. 2019;9:3209. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Du J, Yang JE, Yin CS, Kook M, Yi TH. Brachybacterium horti sp. nov., isolated from garden soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:189–195. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert RM, Krieg NR. Phenotypic Characterization Methods for General and Molecular Bacteriology. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 607–654. [Google Scholar]

- Spain JC. Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:523–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain JC, Gibson DT. Pathway for biodegradation of p-nitrophenol in a Moraxella sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:812–819. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.3.812-819.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E, Goebel BM. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1994;44:846–849. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US-Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA) Water quality criteria documents: availability. Environmental Protection Agency Fed. Reg. Washington, D.C. 1980;45:79–318. [Google Scholar]

- Vikram S, Pandey J, Kumar S, Raghava GPS. Genes involved in degradation of para-nitrophenol are differentially arranged in form of non-contiguous gene clusters in Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan N, Gu JD, Yan Y. Degradation of p-nitrophenol by Achromobacter xylosoxidans Ns isolated from wetland sediment. Int Biodeter Biodegradation. 2007;59:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne LG, Brenner DJ, Colwell RR, Grimont PAD, Kandler O, Krichevsky MI, Moore LH, Moore WEC, Murray RGE, Stackebrandt E, Starr MP, Truper HG. Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1987;37:463–464. doi: 10.1099/00207713-37-4-463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White GF, Snape JR, Nicklin S. Biodegradation of glycerol trinitrate and pentaerythritol tetranitrate by Agrobacterium radiobacter. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:637–642. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.637-642.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Ha SM, Kwon S, Lim J, Kim Y, Seo H, Chun J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1613. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Sun W, Xu L, Zheng X, Chu X, Tian J, Wu N, Fan Y. Identification of the para-nitrophenol catabolic pathway, and characterization of three enzymes involved in the hydroquinone pathway, in Pseudomonas sp. 1–7. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zommere Ž, Nikolajeva V. Immobilization of bacterial association in alginate beads for bioremediation of oil-contaminated lands. Envir Exp Bot. 2017;15:105–111. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Supplementary Fig. 1 Study of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of strain DNPG3 towards various concentrations of PNP, tested in this study (PPT 134 KB)

Supplementary file2 Supplementary Fig. 2 Morphological details of Ca-alginate beads used for immobilization studies (PPT 186 KB)

Supplementary file3 Supplementary Fig. 3 Thin-layer chromatographic (TLC) plate showing hydrolysis intermediates during biodegradation of PNP by the strain DNPG3. From left- Lane 1-4: standards for PNP, 4NC, PBQ and Hydroquinone (HQ); Lane 5, 0 h test sample showing PNP and Lane 5, 144 h test sample showing the presence of PBQ (PPT 197 KB)

Supplementary file4 Supplementary Fig. 4 Proposed pathway of biodegradation of PNP by the strain DNPG3, isolated in this study (PPT 96 KB)

Supplementary file5 Supplementary Table 1 Characteristic features of bacterial whole-cell immobilized Ca-alginate beads used in this study. Abbreviations: CFU, Colony forming Units (DOC 28 KB)