Abstract

The gene encoding the scaffolding protein of the cellulosome from Clostridium cellulolyticum, whose partial sequence was published earlier (S. Pagès, A. Bélaïch, C. Tardif, C. Reverbel-Leroy, C. Gaudin, and J.-P. Bélaïch, J. Bacteriol. 178:2279–2286, 1996; C. Reverbel-Leroy, A. Bélaïch, A. Bernadac, C. Gaudin, J. P. Bélaïch, and C. Tardif, Microbiology 142:1013–1023, 1996), was completely sequenced. The corresponding protein, CipC, is composed of a cellulose binding domain at the N terminus followed by one hydrophilic domain (HD1), seven highly homologous cohesin domains (cohesin domains 1 to 7), a second hydrophilic domain, and a final cohesin domain (cohesin domain 8) which is only 57 to 60% identical to the seven other cohesin domains. In addition, a second gene located 8.89 kb downstream of cipC was found to encode a three-domain protein, called ORFXp, which includes a cohesin domain. By using antiserum raised against the latter, it was observed that ORFXp is associated with the membrane of C. cellulolyticum and is not detected in the cellulosome fraction. Western blot and BIAcore experiments indicate that cohesin domains 1 and 8 from CipC recognize the same dockerins and have similar affinity for CelA (Ka = 4.8 × 109 M−1) whereas the cohesin from ORFXp, although it is also able to bind all cellulosome components containing a dockerin, has a 19-fold lower Ka for CelA (2.6 × 108 M−1). Taken together, these data suggest that ORFXp may play a role in cellulosome assembly.

Clostridium cellulolyticum, a mesophilic anaerobic bacterium, secretes cellulolytic complexes called cellulosomes, which have a molecular mass of about 600 kDa (17, 31). These complexes are composed of at least 13 enzymes called cellulases, as well as a large scaffolding protein of about 160 kDa that is devoid of catalytic activity, called CipC (for “cellulosome-integrating protein”) (17). It has been previously shown that the assembly of the cellulosome is due to strong interactions between the cohesin domains of CipC and the dockerin domains of the catalytic subunits (35). This organization is similar to that of the cellulosome produced by C. thermocellum (1, 2, 7, 8, 24), for which it has also been demonstrated that the cohesin domains of the scaffolding protein (CipA) act as receptors for the dockerin domains of the enzymatic components (14, 30, 43, 49, 50, 51). Furthermore, the C terminus of CipA contains a slightly divergent dockerin domain (type II), which interacts with a second class of cohesin domains present in at least three cell surface proteins (SdbA, OlpB, and ORF2p) (15, 18, 26, 27, 29). It is believed that this second kind of cohesin-dockerin complex is involved in the attachment of cellulosome to the cell surface whereas the interaction between the type I cohesin and dockerin domains involves only the cellulosome assembly. Another cellulosome-producing clostridium, C. cellulovorans, has also been extensively studied, and although the scaffolding protein CbpA contains cohesin domains similar to those of C. thermocellum and C. cellulolyticum, the way in which the enzymatic components interact with CbpA remains unclear or at least would appear to involve a different mechanism, since dockerinless enzyme, EngD, was found to be part of the cellulosome (12, 13, 45–47). More recently, the cipA gene, encoding the cellulosome scaffolding protein CipA from C. josui (a bacterium related to C. cellulolyticum as demonstrated by comparison of 16S rDNA), was sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequence of CipA reveals that this scaffolding protein contains six cohesin domains and, as in CbpA from C. cellulovorans, does not contain a type II dockerin domain, as found in the scaffolding protein CipA from C. thermocellum.

The cellulolytic complex from C. papyrosolvens C7 was characterized biochemically some years ago (37). Seven cellulosomal fractions ranging from 500 to 600 kDa were separated by gel filtration chromatography and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The only subunit present in all the fractions was a 125,000 Mr glycoprotein with no detectable enzymic activity. The latter could be cellulosomal scaffolding protein, but unfortunately the sequence of the gene is not still available.

The partial sequence (5′ and 3′ extremities) of cipC has already been published (35, 40). In the present study, the complete sequence of cipC was determined and the amino acid sequence of the corresponding protein was analyzed and compared to those of CipA and CbpA. In addition to the cellulose binding domain (CBD) and two hydrophilic domains, CipC contains only eight cohesin domains. The first seven cohesin domains are highly homologous, while the last (cohesin 8), located at the C terminus, displays a much lower degree of homology to the other seven. Furthermore, the sequencing of a new gene, ORFX, encoding ORFXp, located in the C. cellulolyticum gene cluster, revealed that the protein encoded by this gene is composed of three domains, the last one being a cohesin domain, called cohesin X.

By using surface plasmon resonance (BIAcore) and Western blot procedures, the recognition patterns of cohesin domains 8 and X were determined and compared to that of cohesin domain 1. The subcellular localization of ORFXp was also determined. On the basis of these data, new hypotheses on the assembly of the C. cellulolyticum cellulosome and the role of ORFXp during this step are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) was used as the host for pET22b(+) (Novagen) derivative expression vectors (pETCip1, pETCip8, and pETCipX) (34). E. coli was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) when required. C. cellulolyticum ATCC 35319 was grown anaerobically at 32°C on basal medium supplemented with either cellobiose (2 g/liter) (Sigma) or MN 300 cellulose (5 g/liter) (Serva) as the carbon and energy source (20).

DNA manipulation.

Chromosomal DNA was obtained from C. cellulolyticum as described by Quiviger et al. (38). Large-scale and small-scale plasmid purifications were performed by the alkali lysis method (33) with the Qiagen kit. Digestion was performed as specified by the manufacturer.

DNA sequencing of cipC.

The 5′ and 3′ ends of cipC have already been sequenced (35, 40). The internal fragment of cipC (3,462 bp) was amplified by PCR with the two synthesized oligonucleotides ciph1 (5′ GTA-GGA-GGA-ACT-CTT-GCT-TA 3′) and ciph2 (5′ TCA-AAA-GAT-GCA-GTT-GAA-GGA-GT 3′). These two primers were designed to bind DNA regions encoding the two hydrophilic domains. The PCR fragment was cloned into pUC18, and the extremities of the insert were sequenced with the M13 forward and M13 reverse primers. This fragment was subsequently digested with HindIII, and the resulting fragments were cloned into pUC18 and sequenced.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins.

Cohesin domain 1, present in the polypeptide miniCipC1 (CBD-HD1-C1) (35), was replaced by cohesin domain 8. The pCip12A plasmid (34) containing the DNA fragment encoding miniCipC1 and cloned into the p-Mos-Blue-T-vector was digested with SmaI and SalI, and the smaller fragment, encoding miniCipC1 (containing a NdeI site upstream of the coding sequence and a SalI site downstream a codon stop), was cloned into the pUC18 vector. The resulting plasmid, pUCC12, was digested with EcoRV and SalI to remove the part of the DNA fragment encoding cohesin domain 1. Two synthetic primers, cip 810 (5′ GGG-AAT-TCC-ATA-TGT-CGC-GAC-CAG-TTC-TGA-C 3′) and cip 811 (5′ ACG-CGT-CGA-CTT-AAT-TAA-GTT-TTG-CAC-TTC-C 3′), having partial homology to the 5′ and 3′ DNA regions, respectively, of the DNA fragment encoding cohesin domain 8 were synthesized. cip 810 created a NruI site upstream of the coding sequence, and cip 811 introduced a SalI site and a stop codon downstream of the coding sequence. The amplified fragment (encoding cohesin domain 8) was digested with NruI and SalI and cloned into pUCC12 digested with EcoRV and SalI. The resulting plasmid, pUCC9, was digested with NdeI and SalI, and the DNA fragment encoding a polypeptide called miniCipC8 (CBD-HD1-C8) was cloned into NdeI-SalI-linearized pET22b(+). The resulting plasmid, pETCip8, was verified by DNA sequencing (Genome Express Society) with a Perkin-Elmer 373 fluorescence sequencing apparatus (Applied Biosystems dye terminator method).

As described above, cohesin domain 1 present in the polypeptide miniCipC1 was replaced by the cohesin domain present in the protein ORFXp. Two synthetic primers, cip 298 (5′ GGG-TTT-AAA-ACT-CCG-GGC-GGA-GAG-G 3′) and cip 767 (5′ C-ACC-GTC-GAC-TTA-TTT-AAC-TGT-TAT-CTC-ACC 3′), having partial homology to the 5′ and 3′ DNA regions, respectively, of the DNA fragment encoding cohesin domain X were synthesized. cip 298 created a DraI site upstream of the coding sequence, whereas cip 767 created a SalI site and a stop codon downstream of the coding sequence. After amplification, the DNA fragment (encoding cohesin domain X) was digested with DraI and SalI and cloned into pUCC12 digested with EcoRV and SalI. The resulting plasmid, pUCCX, was digested with NdeI and SalI, and the DNA fragment encoding a polypeptide called miniCipX (CBD-HD1-CX) was cloned into pET22b(+). The resulting plasmid, pETCipX, was verified by sequencing as described above.

pETCip8 and pETCipX were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) strains containing inducible T7 polymerase under the control of the lac promoter. The transformed cells were grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin to an optical density at 600 nm of 2. The expression was triggered by the addition of 400 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and the cells were grown (at 37°C) for an additional 3 h.

To overproduce cohesin X, the DNA region encoding cohesin domain X was amplified by PCR from C. cellulolyticum chromosomic DNA. Forward primer 5′ G-GTG-GGT-CAT-ATG-GAT-AAA-ACT-CCG-GGC-GGA-GAG 3′ and reverse primer 5′-C-CAG-CTC-GAG-CTA-GTG-GTG-GTG-GTG-GTG-TTT-AAC-TGT-TAT-CTC-ACC-C 3′, which have partial homology to the 5′ and 3′ extremities, respectively, of the DNA region encoding cohesin X, were used for the amplification and introduction of NdeI (5′) and XhoI (3′) sites. The reverse primer was also designed to graft five histidines at the C terminus of cohesin X (the His codons are underlined). The amplified fragment was digested with NdeI and XhoI and cloned into plasmid pET22b(+) linearized with the same restriction endonucleases. The resulting plasmid, pETCX, was checked by sequencing as described above and used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3).

Purification of recombinant proteins.

miniCipC8 and miniCipCX were purified as described by Pagès et al. (35).

Cells harboring plasmid pETCX were grown in 1 liter of Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C to an optical density of 1.5 at 600 nm. IPTG at a final concentration of 0.5 mM was then added to the culture, which was continued for 3 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation (10 min at 5,000 × g), and resuspended in 40 ml of 0.1 M NaCl–30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The cells were broken by passing the suspension in a French press. DNase I (5 μg/ml) was added to the crude extract, and this solution was incubated at 4°C for 30 min. The solution was then loaded onto 5 ml of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen) equilibrated in the same buffer. The resin was washed with 30 mM imidazole–30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), and cohesin X was eluted with a linear gradient from 30 to 250 mM imidazole (two elutions with 200 ml each). Analysis by SDS-PAGE of the cohesin X-containing fractions indicated that no further purification was required. The fractions were pooled (30 ml) and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 5 liters of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). The sample was used as stock solution.

Antibody preparation.

Polyclonal antibodies against miniCipC1 and miniCipX were raised in rabbits by subcutaneous injection of the pure proteins. Antisera were stored at −20°C with 0.3% NaN3. Antisera raised against miniCipC1 and miniCipX were preadsorbed with E. coli BL21DE3[pET22b(+)] extract. The antiserum raised against miniCipX was further preabsorbed with pure recombinant protein called miniCipC0 (CBD-HD1) (34). The antiserum raised against miniCipC1 recognizes the polypeptides miniCipC1 (CBD-HD1-C1) and miniCipC0 (CBD-HD1), the CBD, and the native protein CipC from C. cellulolyticum. This antibody preparation was called Ab α CipC. The antiserum raised against miniCipX was preabsorbed with miniCipC0 to avoid cross-reactions with the CBD or the hydrophilic domain. This antibody preparation was called Ab α CX.

Fractionation of C. cellulolyticum cultures.

The fractionation method was derived from the procedure described by Lemaire et al. (29). The preliminary steps of the fractionation were different depending upon the growth substrate. For cellobiose, 1 liter of C. cellulolyticum culture, grown to an optical density at 450 nm of 1.2, was centrifuged. The culture supernatant was concentrated on a Millipore polysulfone membrane (10-kDa cutoff) to 10 ml. It was called the F0 fraction. Cells were washed with buffer A (50 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]), resuspended in 10 ml of the same buffer, and broken in a French press. This sample was called fraction F1. The F1 fraction was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min. Then the pellet, containing the intact cells, was discarded, and the supernatant was centrifuged for 30 min at 46,000 × g. The supernatant was called fraction F2. This fraction contains the cytoplasmic soluble proteins. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of buffer B (50 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS [pH 7.5]). This sample was called fraction F3. This fraction contains the membrane proteins and the proteins associated with the cell surface. Fraction F3 was heated at 100°C in a water bath for 15 min and centrifuged for 30 min at 46,000 × g. This treatment removed proteins that were noncovalently associated with the cell surface. The supernatant was called fraction F4. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of buffer B (fraction F5). After being heated at 100°C for 15 min, fraction F5 was centrifuged for 30 min at 46,000 × g. The supernatant was called fraction F6, and the pellet resuspended in 10 ml of buffer B was called fraction F7.

When C. cellulolyticum was grown on cellulose (4 days), the cells (from 1 liter of culture) were collected by filtration through a 3-μm-pore-size filter (glass microfiber filter GF/D; Whatman). The culture was filtered and washed on the filter twice with 50 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) to remove the cells from the cellulose. The eluted fraction containing the cells and the culture medium was centrifuged. The supernatant constituted fraction F0 as described above, and the pellet was called fraction F1. The same procedure was used to obtain fractions F2 through F7. The cellulosome (fraction Fc) was eluted from the cellulose with water as described by Gal et al. (17).

SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE was performed by the procedure developed by Laemmli (23) with precast 4 to 20% polyacrylamide (Novex) gels.

Detection of ORFXp in subcellular fractions of C. cellulolyticum.

Immunodetection of ORFXp was performed by Western blotting as previously described by Gal et al. (17), using the Ab α CX sample.

Biotinylation of proteins and biotin-labelled detection.

Biotinylation of miniCipC8 and miniCipX was performed with biotinyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester as described by Bayer and Wilcheck (6) (biotin-labelling kit; Boehringer Mannheim) as specified by the manufacturer.

Study of the cohesin-dockerin interaction.

The interaction of the cellulosomal subunits with miniCipC1, miniCipC8, miniCipCX, and cohesin X was examined by using the biotin-labelled mini-scaffolding proteins as probes against the different polypeptides present in cellulosome fraction Fc.

The kinetic parameters of the interaction between the recombinant cellulase CelA and the recombinant polypeptides described above were determined by using the BIAcore procedure. The biotinylated miniCipC1, miniCipC8, miniCipCX, or recombinant cohesin X was coupled to a streptavidin-dextran layer on the surface of the sensor chip. Biotinylated recombinant proteins were injected for 120 s, resulting in approximately 750 resonance units of immobilized protein. The flow cell was equilibrated with 10 mM CaCl2–0.005% surfactant P20 (Pharmacia)–50 mM Tris-maleate buffer (pH 6.5) at a flow rate of 25 μl/min. The ligand (CelA) was diluted in the same buffer and allowed to interact with the sensor surface by a 300-s injection. In all cases, three different concentrations of CelA ranging from 2.5 to 25 nM were injected. The resulting sensorgrams were evaluated by using the biomolecular interaction analysis evaluation software (Pharmacia) to calculate the kinetic constants of the complex. Control experiments were performed by injections of CelA directly onto the streptavidin-dextran surface and by injection of a truncated form of the cellulase, missing the dockerin domain on cohesin X or miniCipC1.

Glycoprotein detection.

The glycosylated protein was detected as specified by the manufacturer: the glycoprotein detection system was from Amersham, and the transfer was performed on Ba83 nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The entire nucleotide sequence of cipC has been submitted to GenBank and has been assigned accession no. U40345. The nucleotide sequence of ORFX has been submitted to GenBank and has been assigned accession no. AF081458.

RESULTS

Primary-structure analysis of the scaffolding protein CipC.

The cipC coding sequence of 4,742 nt was determined. The internal DNA fragment of cipC contains several repeats with a high degree of similarity (about 98%). To check that this internal fragment obtained by PCR (Fig. 1A) has the appropriate size, Southern blot experiments were performed with an internal EcoRV-XmnI 2,741-nt probe obtained from this PCR fragment. The genomic DNA was digested with Asp718-HindIII, Asp718-EcoRV, Asp718-BamHI, and XmnI. In each case, the size of the fragments detected by the probe corresponded to the theoretical values calculated from the sequence (data not shown). The open reading frame (ORF) therefore encodes a polypeptide containing 1,547 amino acids (aa). As previously described by Pagès et al. (35), the ORF begins by encoding a peptide signal sequence. The N terminal sequence of the mature protein was previously determined by Gal et al. (17). The mature protein contains 1,519 aa with a calculated molecular mass of 155,726 Da, in agreement with the value of 160 kDa previously established by SDS-PAGE analysis of a cellulosomal fraction (17). A stretch of 700 bp upstream of the initiation codon was sequenced, and no ORF was found in this region, thus indicating that cipC is the first gene of a large cluster including celF, celC, celG, and celE (16).

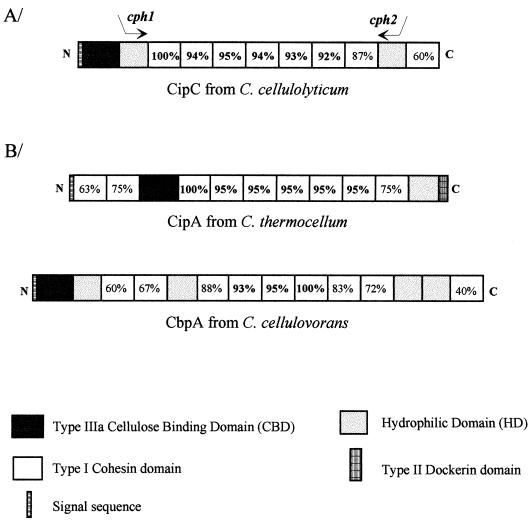

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of CipC from C. cellulolyticum, CipA from C. thermocellum, and CbpA from C. cellulovorans. (A) The positions of the two oligonucleotides used for the amplification of the internal fragment of cipC are indicated by arrows. (B) The signal sequences, CBDs, hydrophilic domains, and cohesin domains are shown. The percent identity between cohesin domains is indicated in each box. Cohesin domains 1, 3, and 6 were used as the reference in CipC, CipA, and CbpA, respectively.

Like the other two scaffolding proteins, CipA from C. thermocellum and CbpA from C. cellulovorans, CipC is a multidomain protein (18, 46). The molecular organization of the three scaffolding proteins is compared in Fig. 1B. CipC is composed of a signal sequence, a type III CBD (subfamily a), two hydrophilic domains, and eight cohesin domains separated by short linker sequences. Compared to CipA, the most striking feature of CipC and CbpA is the lack of type II dockerin domains. In C. thermocellum, this domain is involved in cell surface attachment of the cellulosome (26, 27).

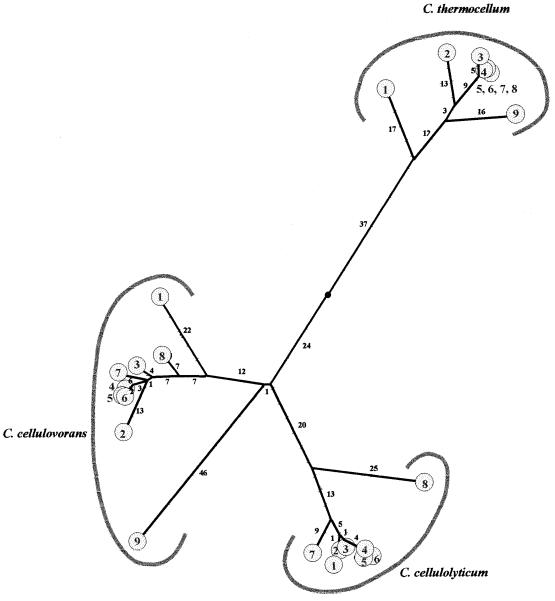

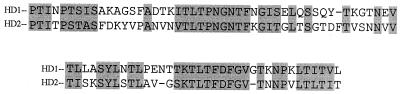

The internal degree of identity between cohesin domain 1 and the other cohesin domains of CipC was determined (Fig. 1B). This domain is 95 to 87% identical to cohesin domains 2 to 7. Cohesin domain 8, which possesses only 60% identity to cohesin 1, is the most divergent. A similar observation was made for CipA from C. thermocellum (44) and CbpA from C. cellulovorans (11), as illustrated in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). It would appear that in the scaffoldins known to date, there is a large group of highly homologous cohesins as well as at least one cohesin domain, always located at one extremity of the protein, with significant sequence differences compared to the internal cohesin domains. In this respect, CbpA from C. cellulovorans (11) is the most remarkable since, as shown in Fig. 2, cohesin domain 9 (located at the C terminus) is more divergent compared to the other cohesin domains. The phylogenetic tree, however, also indicates that these “divergent” cohesin domains resemble the other cohesin domains of the same scaffolding more closely than they resemble any cohesin domain of another scaffoldin. It is also clear from Fig. 2 that in terms of similarity, the cohesin domains of CipC are more homologous to those of CbpA than to those of CipA, even though sequencing of the gene encoding 16S rRNA (16S rDNA) indicates that C. cellulolyticum is more closely related to C. thermocellum than to C. cellulovorans (39). CipC contains two hydrophilic domains (HD1 and HD2). These two domains have only 56% similarity, but two short stretches of 18 and 21 aa are highly conserved (83 and 86%, respectively) (Fig. 3). The role of these two domains remains unknown. The hydrophilic domains found in CbpA have significant similarities to HD1 and HD2 (46). A lower degree of similarity between HD1 and HD2 and the hydrophilic domain of CipA was found (4, 19). Similar hydrophilic domains have been found in nonscaffolding proteins; two domains have been identified in Cel5 from Bacillus lautus and in CelZ from C. stercorarium, and one has been identified in CelY from the latter organism (10, 21).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of cohesin domains from CipC, CipA (C. thermocellum), and CbpA. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the program AllAll accessible on the Computational Biochemestry Research Group server from E.T.H. Zurich, Switzerland. The length of each branch is proportional to the evolutionary distance between the nodes. The small black circle indicates the weighted centroid of the tree. The distances are expressed in pam (percent average mutation). For each scaffolding protein, the cohesin are numbered.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of CipC hydrophilic domains HD1 and HD2. The conserved amino acids are in gray boxes.

Comparison of the interaction of cohesin domains 1 and 8 with cellulosomal subunits.

It has been demonstrated that cohesin domain 1 of CipC is a receptor domain for catalytic subunits, and the dissociation constant of the miniCipC1-CelA complex has been measured (35). In view of the high identity, one might suppose that cohesins 2 to 7 recognize the dockerin domains with an affinity similar to that of cohesin domain 1. Since the degree of identity between cohesin domains 1 and 8 drops to 60%, it was of interest to compare the recognition pattern and the kinetic parameters of the formation of the complex with CelA of these two cohesin domains.

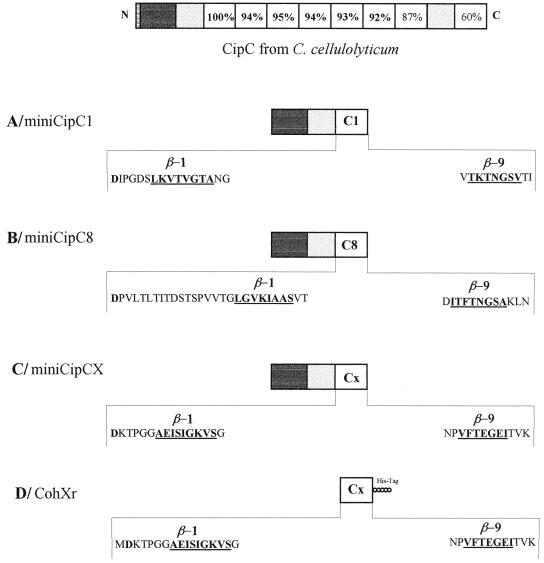

(i) Mini-scaffolding protein constructions.

To facilitate both the purification and the comparisons of the binding abilities of cohesin domains 1 and 8, the cohesin domain 1 in miniCipC1 was replaced by the cohesin domain 8 (Fig. 4A and B). The engineered polypeptide was called miniCipC8. This replacement was performed by taking into account the recent determination of the three-dimensional structures of cohesin domains 1 (44) and 7 (48) from CipA. These domains form a nine-stranded β sandwich with a “jelly-roll” topology. In view of the high sequence homologies among the cohesin domains of C. thermocellum, C. cellulolyticum, and C. cellulovorans, it is very likely that they have the same overall structure. The oligonucleotides designed for amplification of the DNA fragment encoding cohesin domain 8 were therefore chosen as function of the known structures. The recombinant cohesin domain 8 thus possesses the amino acids involved in the first β strand with respect to a correct folding of this domain (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 4.

Diagram of the recombinant proteins used. Dark gray boxes indicate CBD, light gray boxes indicate hydrophilic domains, and white boxes represent cohesin domains. Small circles represent the His tag. The underlined residues are the first and last residues of the cohesin domain identified on the basis of the available crystal structures and sequence comparisons.

(ii) Study of the interaction.

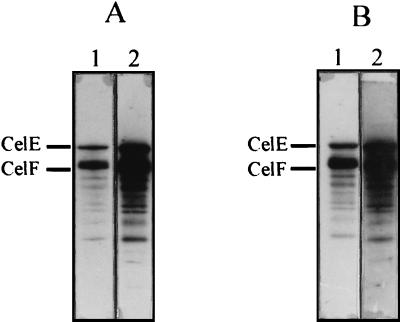

The biotinylated miniCipC1 and miniCipC8 were used as a probe for the different cellulosomal subunits, separated by SDS-PAGE. Formation of the complex was visualized with a streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate. The recognition pattern of cohesin domain 8 was compared to that of cohesin domain 1. As described previously (17), about 13 bands (94, 89.6, 80.6, 77.9, 72.6, 67.7, 58.9, 54.2, 53, 49, 44.5, 43, and 29.5 kDa) yielded a positive signal with miniCipC1 and no significant difference was observed when miniCipC8 was used as the probe (Fig. 5). Determination of the kinetic parameters (association rate constant, kon, and dissociation rate constant, koff) of the miniCipC1-CelA and miniCipC8-CelA interaction confirmed that CelA interacts with these two domains with the same, very high affinity (Table 1), in spite of the sequence differences between the two cohesin domains. These results suggest that, as proposed by Yaron et al. (51) for the cellulosome of C. thermocellum, incorporation of the cellulosomal subunits into the cellulosome in C. cellulolyticum also seems to be a nonselective process, i.e., that any cellulase could interact randomly along the scaffolding protein. A higher Ka value (Ka = 4.8 × 109 M−1) was found for the miniCipC1-CelA complex in the present study than was proposed elsewhere (1.4 × 108 M−1) (35). This is due to the presence of 10 mM CaCl2 in the running buffer. During the first experiments, no calcium was added, and since the running buffer was 50 mM KH2PO4–K2HPO4, the available calcium concentration was likely to be very low. This 34-fold improvement in Ka highlights the importance of calcium in the cohesin-dockerin interactions.

FIG. 5.

Recognition of SDS-PAGE-separated cellulosomal components by recombinant cohesin domains 1 and 8 of CipC. SDS-PAGE-separated samples were blotted onto nitrocellulose and probed with the biotinylated miniscaffolding protein desired. Blots were developed with streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate. Two different concentrations of cellulosomal preparation were used, 3 μg (lanes 1) and 6 μg (lanes 2). (A) SDS-PAGE-separated cellulosomal subunits probed with miniCipC1. (B) SDS-PAGE-separated cellulosomal subunits probed with miniCipC8. The presence of the two major cellulases of the C. cellulolyticum cellulosome, CelE and CelF, previously identified (17), are indicated.

TABLE 1.

Recombinant cohesin domains and CelA associations and kinetic parametersa

| Domain | kon (M−1 · s−1) | koff (s−1) | Ka (M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| miniCipC1-CelA | 1.5 × 106 | 3.1 × 10−4 | 4.8 × 109 |

| miniCipC8-CelA | 1.6 × 106 | 4.2 × 10−4 | 3.8 × 109 |

| CohXr-CelA | 1.3 × 106 | 5.0 × 10−3 | 2.6 × 108 |

Kinetic constants were determined from sensorgrams as described in Materials and Methods. The apparent equilibrium dissociation constant, Ka, was determined from the ratio of the two kinetic constants (kon/koff).

A new cohesin-harboring protein.

In C. thermocellum, two genes encoding proteins involved in the cell surface attachment of the cellulosome form a cluster with the cipA gene (15). These genes encode a membrane-associated protein containing a cohesin domain II able to interact with the type II dockerin domain of CipA (15, 26, 27, 29). Analysis of the primary sequence of CipC indicates that no such domain is present in CipC. Nevertheless, in the large cluster of gene including cipC, celF, celG, and celE a new ORF, encoding a protein harboring a cohesin domain, was discovered. In addition, this new ORF is located between two cellulase genes (16), which strongly suggests an involvement at some stage of cellulose degradation and/or cellulosome assembly.

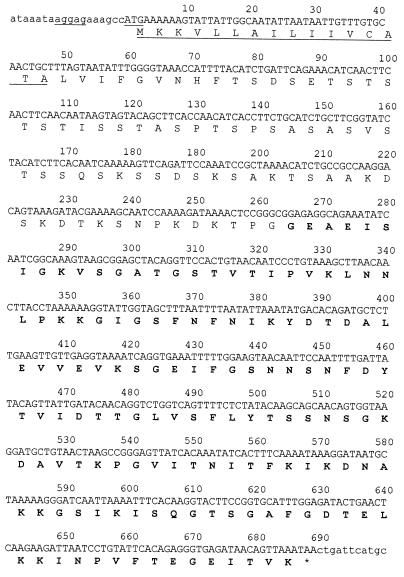

The initiation codon, ATG, of this new ORF is located 169 bp downstream of the celE stop codon and is preceded by a typical Shine-Dalgarno sequence. The entire sequence of 693 nucleotides codes for a protein made up of 229 aa with a calculated molecular mass of 23,855 Da. Based on its sequence analysis, this protein can be divided into three distinct domains. The first domain, of about 25 aa, located at the NH2 terminus of the protein, is likely to be a typical signal sequence of a gram-positive organism. It is followed by a P-T-S rich region of 58 aa, similar to the linker regions found in many cellulases and xylanases, and a putative cohesin domain at the C terminus of the protein (Fig. 6). The sequence of this last domain was compared with the sequences of two type I cohesins (cohesin domains 1 and 8 from CipC) and with a type II cohesin present in SdbA from C. thermocellum (27). This cohesin domain, called cohesin domain X, is 35 and 28% identical to cohesin domains 1 and 8 from CipC, respectively, and has only 15% identity to cohesin domain II from SdbA. The presence of this new ORF raises at least three basic questions. (i) Is the corresponding protein produced by the bacterium? (ii) Where is it located in the bacterium? (iii) Which kind of dockerin domain recognizes the cohesin domain of ORFXp?

FIG. 6.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acids sequences of the ORFX gene, encoding the predicted signal sequence (underlined), a putative linker domain, and a cohesin X domain (boldface type). The putative Shine-Dalgarno ribosome binding site is underlined upstream of the ATG codon.

To answer these questions, a new mini-scaffolding protein was constructed. Cohesin domain 1 of miniCipC1 was replaced by the cohesin-like domain present in ORFXp while preserving a theoretical correct folding of this domain (Fig. 2C). This new recombinant protein, called miniCipCX, was used to obtain antibodies (Ab α CX) and to prepare a biotinylated probe for binding experiments.

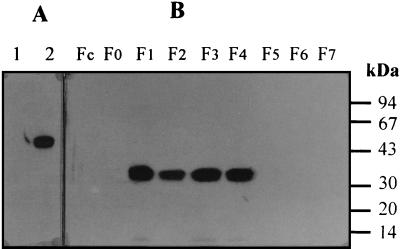

Subcellular localization of ORFXp.

The presence of CipX in various fractions from a cellulose-grown culture was detected by Western blotting with Ab α CX, which interacts specifically with cohesin domain X (Fig. 7A). The fractionation procedure used is described in Materials and Methods. The protein was not detected in fractions Fc and F0. ORFXp was detected in fractions F1 to F4 but was found mainly in fractions F1, F3, and F4, suggesting that it could be cell associated (Fig. 7B). The presence of the protein in the cytoplasmic fraction (F2) could be explained by a release of part of the protein from the membranes during the French press procedure. Indeed, it has been previously reported (29, 42, 43) that some of the cell-associated proteins discovered in C. thermocellum, i.e., OlpA, OlpB, ORF2p, and SdbA, are also present in the soluble fraction after cell sonication (26, 29, 42).

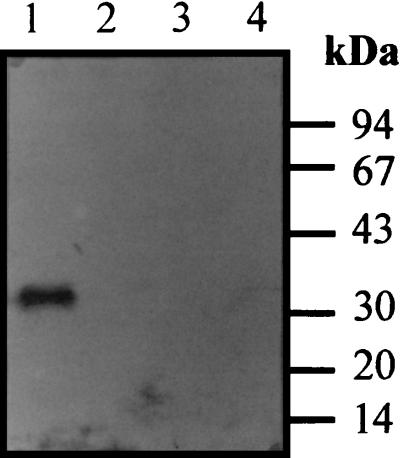

FIG. 7.

Subcellular localization of ORFXp. (A) Two recombinant proteins, miniCipC1 (lane 1) and miniCipCX (lane 2), were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose, and probed with antibody raised against cohesin domain X. The blots were developed with anti immunoglobulin G-peroxidase conjugate. Incubation (lane 2) with miniCipCX indicates that antibodies (Ab α CX) specifically recognize cohesin domain X in the miniCipCX construction. (B) The different fractions obtained from the C. cellulolyticum cellulose growth culture (Fc to F7) were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with antibody (Ab α CX) raised against cohesin domain X (see Materials and Methods for a discussion of fractionation of C. cellulolyticum cultures).

The estimated molecular mass of ORFXp (33 kDa) is higher than the calculated molecular mass (23,755 Da). This difference is probably because ORFXp is highly glycosylated (data not shown). A similar phenomenon was also observed for the cellulosome from C. thermocellum, in which 5 to 7% of the total mass can be attributed to carbohydrates (19). Most of them are formed by O-glycosylation of the Thr residues located in the linker regions of CipA. Since ORFXp contains a P-T-S-rich fragment made up of 58 aa, which accounts for 25% of the protein, it is probable that this domain can constitute the site of glycosylation, leading to an unexpected migration on SDS-PAGE. Despite numerous attempts using SDS-PAGE and transfers to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, it was not possible to obtain sufficient amounts of the protein to determine the N-terminal sequence.

ORFXp was not detected on cellobiose-grown cultures in all the fractions tested (F0 to F7). Production of ORFXp can be induced, however, by addition of 100 mg of cellulose per liter.

Identification of the partner of ORFXp.

To understand the role of ORFXp, the binding capacity of the cohesin domain present in ORFXp was studied. First, fraction Fc, subjected to SDS-PAGE, was probed with biotinylated miniCipX (Fig. 4C). No binding was detected, suggesting that cohesin domain X does not interact with type I dockerin domains. Similar results were obtained with fractions F0 to F7 under cellobiose and cellulose growth conditions (data not shown), suggesting that cohesin domain X is not able to bind any partner in C. cellulolyticum.

Although great care was taken during the construction of miniCipX to maintain the available three-dimensional cohesin structures (Fig. 4C), the fusion of cohesin X with the CBD and the hydrophilic domain may have induced an incorrect folding of the cohesin domain. Furthermore, this domain is preceded by a long linker domain in ORFXp whereas cohesin domains 8 and 1 are located downstream of an hydrophilic domain. Thus, in the chimeric protein miniCipCX, cohesin domain X has a different environment, which could explain the negative results obtained with miniCipCX. To verify this assumption, a new construction was undertaken. Cohesin domain X alone was overexpressed with a His tag. Recombinant cohesin domain X, called CohXr (Fig. 4D), was studied in terms of binding abilities. Surprisingly, the results showed that this cohesin domain is able to interact with all the cellulosomal subunits containing the dockerin domain (present in the Fc fraction) just like miniCipC1 or miniCipC8. These results clearly indicate that the cohesin X present in the chimeric protein miniCipCX was not functional.

By using the BIAcore, the binding parameters for CohXr with CelA were determined and a 19-fold-lower Ka was found (Ka = 2.6 × 108M−1 [Table 1]), compared to that for the miniCipC1-CelA complex. Interestingly the drop in Ka was almost exclusively due to the dissociation rate constant (koff), with the association rate constant (kon) being unchanged, indicating that the dissociation of the CohXr-dockerin complex is much faster.

DISCUSSION

The cipC gene from C. cellulolyticum has been entirely sequenced, and analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence reveals that CipC is composed of a type IIIa CBD, two hydrophilic domains, and eight cohesin domains. The properties of the CBD are the subject of a previous study (35), and the function of the two hydrophilic domains is currently unknown. Cohesin domains present in CipC (type I cohesin domains) are highly homologous and, in contrast to CipA from C. thermocellum, are separated by very short linker regions (4). In spite of sequence differences, the two most divergent cohesin domains (cohesin domains 1 and 8) have the same affinity for the dockerin domain from CelA. In addition, it was previously reported that the dockerin domains present in CelF and in CelA have the same high affinity for cohesin domain 1 (41). Taken together, these results suggest that the incorporation of the different cellulases into the cellulosome is not cohesin specific. CipC harbors eight cohesin domains, whereas 13 proteins containing a dockerin domain have been detected in the cellulosome fraction of C. cellulolyticum. This observation suggests that different cellulosomal particles, with different enzymatic compositions, are produced by C. cellulolyticum, as was observed for C. papyrosolvens C7. The fact that CelF and CelE are much more abundant than the other catalytic subunits could indicate that these two proteins are always integrated in the complexes and that the heterogeneity of the cellulosomes applies only to the other catalytic subunits. This also highlights the peculiar role of these two cellulases in the degradation of cellulose.

Another interesting feature is the absence, such as in CbpA and CipA from C. josui, of type II dockerin domains in CipC (44). This domain, in CipA from C. thermocellum, was found to be responsible for the attachment of the cellulosomes to the cell surface (26, 27). These cellulosomes form cell protuberances (25). In C. cellulovorans, however, protuberances similar to that of C. thermocellum were observed on the cell surface of the bacterium by Bayer and Lamed (3) using scanning electron microscopy. Recently, the presence of cellulolytic cell surface protuberances has been confirmed (9), suggesting that the mechanism of attachment of the cellulosomes in C. cellulovorans is different from that in C. thermocellum. Such experiments have not been carried out with C. cellulolyticum, and it is therefore not known if this bacterium possesses similar protuberances. If C. cellulolyticum possesses cellulolytic protuberances, like the majority of cellulosome-producing organisms, it can be assumed that the mechanism of attachment of the cellulosomes to the cell surface is similar to that of C. cellulovorans.

Cohesin domains 1 to 5 of CipC are highly homologous (88%) to the five first cohesin domains of CipA from C. josui. As in C. cellulolyticum, the last cohesin domain of CipA (cohesin domain 6) is more divergent than the five first (63%) and is highly homologous to cohesin domain 8 of CipC (89% homology) (22).

The role of ORFXp is not clear. ORFX is located in the cluster of cel genes, 8,980 bp downstream of cipC. In C. thermocellum, four genes encoding nonscaffolding cohesin domains were detected. In all cases, the corresponding proteins, SdbA, ORF2p, OlpB, and OlpA (26, 27, 29, 42), contain S-layer homology repeats which anchor these proteins to the cell surface. The first three proteins harbor a cohesin type II domain, which is the receptor of the dockerin type II domain of CipA and therefore allows the anchoring of the cellulosomes. The gene olpA, encoding a protein harboring a type I cohesin domain, is located 7,934 bp downstream of cipA at the end of a cluster including the genes encoding OlpB and ORF2p (15). OlpA contains also a long PTS domain (55 aa) located between the SLH and the cohesin domain (42). The Ka of the complex OlpA-dockerin domain of CelD was measured (43) and found to be 6.9 × 106 M−1. It has been suggested by Leibovitz (28) that OlpA could anchor the catalytic units on the bacterial surface of C. thermocellum at a temporary stage before the incorporation in the cellulosome. ORFXp does not harbor SLH domains. The very long PTS domain (58 aa) located at the NH2 terminus of the protein has not been observed in other proteins involved in cellulolysis; only a very small linker (8 aa) was found at the NH2 terminus of CelA from Rhodothermus marinus, downstream of the putative signal peptide of the protein. Unfortunately, it was not possible to obtain the N-terminal sequence of ORFXp, and so it was not possible to establish whether the putative signal sequence is cleaved. By analogy to other membrane-bound proteins, however, it is possible that the putative signal sequence is not cleaved. For example, such an organization was found in cytochrome c(y) of Rhodobacter capsulatus (34). This protein is composed of three domains: an uncleaved signal-like domain, which anchors the protein to the cytoplasmic membrane; a long linker domain (70 aa); and the cytochrome domain, which lies in the periplasmic space. One can imagine a similar membrane anchoring in ORFXp; however, only electronic microscopy with labelled antibodies can provide new insights into the exact localization of ORFXp and, in particular, cohesin domain X. One hypothesis concerning the role of ORFXp is that it acts as an intermediate in the docking of cellulases during cellulosome assembly, such as has been proposed for OlpA. This hypothesis is supported by the slight difference observed in koff between CohXr and cohesin domain 1 (miniCipC1) when interacting with CelA. The dissociation of the CohX-CelA complex seems to be faster than that of the Coh1-CelA complex, whereas the association constant kon remains almost unchanged. The binding parameters, however, may prove to be very different in vivo, especially considering that ORFXp is membrane bound. The experimental conditions used during the BIAcore experiments are probably very far from the binding conditions in the cell, and the data concerning ORFXp presented here should therefore be used with caution. At this stage, only a genetic approach could provide additional information on the actual role of this protein.

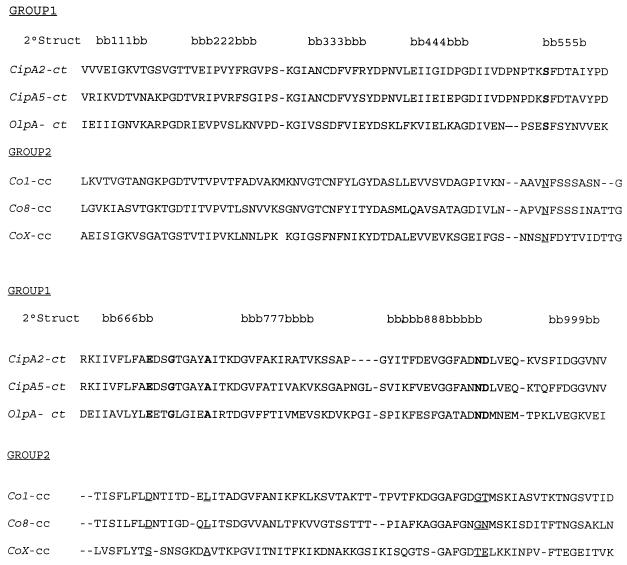

The fact that the macroscopic affinity constant Ka is only 19-fold lower for CohXr than for miniCipC1 while the two cohesin domains have only 35% identity provides a new insight into the residue potentially involved in the interaction with the dockerin domain. Based on the known three-dimensional structures of cohesin and sequence comparisons (Fig. 8), it is now possible to reduce the list of critical residues proposed by Bayer et al. (4) for the interaction with the dockerin. Among the six residues exposed at the surface of the domain, only one, Asn62, in cohesin domain 1, is strictly conserved in cohesin domains 1, 8, and X, and site-directed mutagenesis should confirm the importance of this residue in the specificity of the interaction with the dockerin domain.

FIG. 8.

Sequence alignment of CipA cohesin domains 2 and 5 (CipA2-ct and CipA5-ct) and OlpA cohesin domain from C. thermocellum (OlpA-ct) (data from reference 4), and cohesin domains 1, 8, and X from C. cellulolyticum (Co1-cc, Co8-cc, and CoX-cc). For C. thermocellum, residues in boldface type are strictly conserved among cohesins of the same bacterium and expected to be involved in the interaction with the dockerin domain (group 1). In C. cellulolyticum, the five amino acids expected to be involved in the interaction with dockerin domain are underlined (group 2). The position of the β strands, based on the structure of cohesin domain 2 of CipA, are numbered and indicated by “b.”

In C. thermocellum, the production of the cellulosome is constitutive; only the amount of cellulases and the composition of cellulosomes vary with the carbon source used (5). In C. cellulovorans, the presence of crystalline cellulose promotes cellulosome assembly but all the major cellulolytic components are present in the medium when the cells are grown on cellobiose (32). In C. cellulolyticum, the production of ORFXp is induced by the presence of cellulose (Fig. 9). These observations, together with the fact that ORFXp binds cellulases, support an important role for ORFXp in cellulosome assembly and/or cellulose degradation by the bacterium. Since ORFXp is located in the membrane, it could, for instance, represent a shuttle carrying the free cellulases to CipC, thus facilitating cellulosome assembly in the vicinity of the membrane.

FIG. 9.

Induction of ORFXp production by cellulose. A 500-μl volume of cellulose-grown culture (10 ml with 2 g of cellulose per liter) was used to encemence 10 ml of cellobiose medium (lane 1). This medium contains 0.1 g of residual cellulose per liter. A 500-μl volume of the first growth on cellobiose was used to encemence 10 ml of cellobiose medium (lane 2). This medium contains less than 0.005 g of residual cellulose per liter. Additional inocula were produced (lane 3 and 4) until the concentration of residual cellulose was so low that it could be neglected. In each case, cells were collected by centrifugation after 24 h. The pellet were resuspended in 100 μl of TBS buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM sodium chloride [pH 7.5]) containing 0.1% SDS and 100 mM mercaptoethanol. After being heated at 100°C for 15 min, the samples were centrifuged and 20 μl of the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blots were incubated with antiserum raised against cohesin domain X.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to A. Filloux for helpful discussions and to M. Johnson for correcting the English. We thank I. Svendsen (Carlsberg Laboratory, Copenhagen, Denmark) and the protein-sequencing service of the H. Rochat (Hôpital Nord-Marseille) for the ORFXp N-terminal microsequencing assay. We thank P. Sauve (Service de synthèse des oligonuclotides, CNRS, Marseilles, France) for providing the oligonucleotides used in this study. We are grateful to M. T. Guidici-Orticoni for help with the use of the BIAcore apparatus.

This research was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Université de Provence, the Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and the EEC (BIOTECH contract CT-97-2303).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer E, Lamed R. The cellulosome—a treasure-trove for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer E A, Kenig R, Lamed R. Adherence of Clostridium thermocellum to cellulose. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:818–827. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.818-827.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer E A, Lamed R. Ultrastructure of the cell surface cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum and its interaction with cellulose. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:828–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.3.828-836.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer E A, Morag E, Lamed R, Yaron S, Shoham Y. Cellulosome structure: four-pronged attack using biochemistry, molecular biology, crystallography and bioinformatics. In: Claeyssens M, Nerinckx W, Piens K, editors. Carbohydrates from Trichoderma reesei and other microorganisms. Structure, biochemistry, genetics and application. London, United Kingdom: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1997. pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer E A, Setter E, Lamed R. Organization and distribution of the cellulosome in Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:552–559. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.552-559.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayer E A, Wilchek M. Protein biotinylation. Methods Enzymol. 1990;184:138–160. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)84268-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Béguin P, Aubert J P. The biological degradation of cellulose. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;13:25–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Béguin P, Lemaire M. The cellulosome—an exocellular, multiprotein complex specialized in cellulose degradation. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;31:201–236. doi: 10.3109/10409239609106584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair B G, Anderson K L. Comparison of staining techniques for scanning electron microscopic detection of ultrastructural protuberances on cellulolytic bacteria. Biotech Histochem. 1998;73:107–113. doi: 10.3109/10520299809140514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronnenmeier K, Kunt K, Riedel K, Schwarz W H, Staudenbauer W L. Structure of the Clostridium stercorarium gene celY encoding the exo-1,4-β-glucanase Avicelase II. Microbiology. 1997;143:891–898. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doi R H, Goldstein M, Park J S, Lui C C, Matano Y, Takagi M, Hashida S, Foong F C F, Hamamoto T, Segel I, Shoseyov O. Structure and function of the subunits of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. In: Shimada K, Ohmiya K, Kobayashi Y, Hoshino S, Sakka K, Karita S, editors. Abstracts of the Mie Bioforum 93. Genetics, biochemistry and ecology of lignocellulose degradation. Tokyo, Japan: Uni Publishers; 1993. pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foong F, Hamamoto T, Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Nucleotide sequence and characteristics of endoglucanase gene engB from Clostridium cellulovorans. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1729–1736. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foong F C, Doi R H. Characterization and comparison of Clostridium cellulovorans endoglucanases-xylanases EngB and EngD hyperexpressed in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1403–1409. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1403-1409.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujino T, Béguin P, Aubert J P. Cloning of a Clostridium thermocellum DNA fragment encoding polypeptides that bind the catalytic components of the cellulosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;73:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90602-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujino T, Béguin P, Aubert J P. Organization of a Clostridium thermocellum gene cluster encoding the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipA and a protein possibly involved in attachment of the cellulosome to the cell surface. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1891–1899. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1891-1899.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gal L. Ph.D. thesis. Marseilles, France: University of Provence; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gal L, Pagès S, Gaudin C, Bélaïch A, Reverbel-Leroy C, Tardif C, Bélaïch J P. Characterization of the cellulolytic complex (Cellulosome) produced by Clostridium cellulolyticum. J Bacteriol. 1997;63:903–909. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.903-909.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerngross U T, Romaniec M P M, Kobayashi T, Huskisson N S, Demain A L. Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal SL-protein reveals an unusual degree of internal homology. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:325–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerwig G J, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F, Morag E, Lamed R, Bayer E A. The nature of the carbohydrate-peptide linkage region in glycoproteins from the cellulosomes of Clostridium thermocellum and Bacteroides cellulosolvens. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26956–26960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giallo J, Gaudin C, Bélaich J P. Metabolism and solubilization of cellulose by Clostridium cellulolyticum H10. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1216–1221. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.5.1216-1221.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jauris S, Rucknagel K P, Schwarz W H, Kratzsch P, Bronnenmeier K, Staudenbauer W L. Sequence analysis of the Clostridium stercorarium celZ gene encoding a thermoactive cellulase (Avicelase I): identification of catalytic and cellulose-binding domains. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;223:258–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00265062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kakiushi M, Isui A, Suzuky K, Fujino T, Kimura T, Karita S, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. Cloning and DNA sequencing of the genes encoding Clostridium josui scaffolding protein CipA and cellulase CelD and identification of their gene products as major components of the cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4303–4308. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4303-4308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamed R, Bayer E A. The cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1988;33:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamed R, Naimark J, Morgenstern E, Bayer E A. Specialized cell surface structures in cellulolytic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3792–3800. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3792-3800.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leibovitz E, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Béguin P. Characterization and subcellular localization of the Clostridium thermocellum scaffolding dockerin binding protein SdbA. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2519–2523. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2519-2523.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leibovitz E, Béguin P. A new type of cohesin domain that specifically binds the dockerin domain of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3077–3084. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3077-3084.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leibovitz E. Ph.D. thesis. Paris, France: University of Paris VII; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemaire M, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Fujino T, Béguin P. OlpB, a new outer layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum, and binding of its S-layer-like domain to components of the cell envelope. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2451–2459. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2451-2459.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lytle B, Myers C, Kruus K, Wu J H. Interactions of the CelS binding ligand with various receptor domains of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal scaffolding protein, CipA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1200–1203. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1200-1203.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madarro A, Pena J L, Lequerica J L, Vallés S, Gay R, Flors A. Partial purification and characterization of the cellulases from Clostridium cellulolyticum H10. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 1991;52:393–406. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manato Y, Park J S, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Cellulose promotes extracellular assembly of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosomes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6952–6956. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6952-6956.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myllykallio H, Jenney F E, Moomaw C R, Slaughter C A, Daldal F. Cytochrome cy of Rhodobacter capsulatus is attached to the cytoplasmic membrane by an uncleaved signal sequence-like anchor. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2623–2631. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2623-2631.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pagès S, Bélaïch A, Tardif C, Reverbel-Leroy C, Gaudin C, Bélaïch J-P. Interaction between the endoglucanase CelA and the scaffolding protein CipC of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2279–2286. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2279-2286.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagès S, Gal L, Bélaïch A, Gaudin C, Tardif C, Bélaïch J P. Role of scaffolding protein CipC of Clostridium cellulolyticum in cellulose degradation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2810-2816.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pohlschröder M, Leschine S B, Canale-Parola E. Multicomplex cellulase-xylanase system of Clostridium papyrosolvens C7. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:70–76. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.70-76.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quiviger B, Franche C, Lutfalla G, Rice D, Haselkorn R, Elmerich C. Cloning of nitrogen fixation (nif) gene cluster of Azospirillum brasilense. Biochimie. 1982;64:495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(82)80165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rainey F A, Stackebrandt E. 16S rDNA analysis reveals phylogenetic diversity among the polysaccharolytic clostridia. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;113:125–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reverbel-Leroy C, Bélaïch A, Bernadac A, Gaudin C, Bélaïch J P, Tardif C. Molecular study and overexpression of the Clostridium cellulolyticum celF cellulase gene in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1996;142:1013–1023. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reverbel-Leroy C, Pagès S, Bélaïch A, Bélaïch J P, Tardif C. The processive endocellulase CelF, a major component of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome—purification and characterization of the recombinant form. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:46–52. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.46-52.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salamitou S, Lemaire M, Fujino T, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Béguin P, Aubert J P. Subcellular localization of Clostridium thermocellum ORF3p, a protein carrying a receptor for the docking sequence borne by the catalytic components of the cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2828–2834. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2828-2834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salamitou S, Raynaud O, Lemaire M, Coughlan M, Béguin P, Aubert J P. Recognition specificity of the duplicated segments present in Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD and in the cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2822–2827. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2822-2827.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimon L J W, Bayer E A, Morag E, Lamed R, Yaron S, Shoham Y, Frolow F. A cohesin domain from Clostridium thermocellum—the crystal structure provides new insights into the cellulosome assembly. Structure. 1997;5:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Essential 170-kDa subunit for degradation of crystalline cellulose by Clostridium cellulovorans cellulase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2192–2195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shoseyov O, Takagi M, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Primary sequence analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3483–3487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takagi M, Hashida S, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. The hydrophobic repeated domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein (CbpA) has specific interactions with endoglucanases. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7119–7122. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7119-7122.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tavares G A, Béguin P, Alzari P M. The crystal structure of a type I cohesin domain at 1.7 Angstrom resolution. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:701–713. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokatlidis K, Dhurjati P, Béguin P. Properties conferred on Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelC by grafting the duplicated segment of endoglucanase CelD. Protein Eng. 1993;6:947–952. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tokatlidis K, Salamitou S, Béguin P, Dhurjati P, Aubert J P. Interaction of the duplicated segment carried by Clostridium thermocellum cellulases with cellulosome components. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81279-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yaron S, Morag E, Bayer E A, Lamed R, Shoham Y. Expression, purification and subunit-binding properties of cohesins 2 and 3 of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00074-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]