Abstract

Replication of the IncL/M plasmid pMU604 is controlled by a small antisense RNA molecule (RNAI), which, by inhibiting the formation of an RNA pseudoknot, regulates translation of the replication initiator protein, RepA. Efficient translation of the repA mRNA was shown to require the translation and correct termination of the leader peptide, RepB, and the formation of the pseudoknot. Although the pseudoknot was essential for the expression of repA, its presence was shown to interfere with the translation of repB. The requirement for pseudoknot formation could in large part be obviated by improving the ribosome binding region of repA, either by replacing the GUG start codon by AUG or by increasing the spacing between the start codon and the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD). The spacing between the distal pseudoknot sequence and the repA SD was shown to be suboptimal for maximal expression of repA.

Plasmids which have a low copy number must regulate the frequency of initiation of their replication with great precision in order to be maintained in their host population for many generations. A number of such plasmids regulate their copy number via small antisense RNA molecules. The closely related plasmids pMU720 and ColIb-P9, belonging to the incompatibility groups IncB and IncI1, respectively, use antisense inhibition to regulate the synthesis of a rate-limiting protein essential for replication initiation (Rep) (1, 13, 27, 34, 40). Expression of the Rep protein has been shown to be dependent on formation of a long-range RNA tertiary structure (pseudoknot), which actively enhances rep translation. The pseudoknot interaction involves base pairing between two complementary sequences in the leader region of the rep mRNA. The proximal sequence lies in the upper loop domain of the secondary structure (SLI), which is complementary to and the target of the antisense RNA. The distal sequence adjoins the rep Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) and is normally sequestered in a stem-loop structure (SLIII) which also occludes the rep translation initiation region (TIR). Consequently, pseudoknot formation requires prior translation and correct termination of a leader peptide to disrupt SLIII and expose the distal sequence. The precise mechanism by which the pseudoknot activates rep expression is unknown, but it is thought that the pseudoknot aides recognition of an otherwise inefficient rep TIR and that translational enhancement may involve a direct pseudoknot-ribosome interaction (1, 3, 29, 41).

Binding of the antisense RNA to its complementary target region (SLI) in the rep mRNA regulates translation of Rep predominantly by directly sequestering bases involved in pseudoknot formation (4, 36). Although the proximity of the complex formed when the antisense RNA binds to its target region also sterically hinders the access of ribosomes to the TIR of the leader peptide, this has been shown to be relatively unimportant for efficient regulation of rep expression in pMU720 (42).

The minimal replicon of the IncL/M plasmid, pMU604, is 2.385 kb and contains the genetic information for stable replication and copy number control (5). Although pMU604 is only distantly related to the IncB and IncI1 plasmids, the mechanism by which it regulates its copy number closely resembles that described for pMU720 and ColIb-P9, in that it involves both translational coupling with a leader peptide (repB) and pseudoknot formation for efficient expression of the Rep protein (RepA). The replicons of pMU604 and pMU720 show significant differences in the positioning of sequences involved in the regulation and expression of repA. These differences include the spacing between the proximal and distal pseudoknot sequences, the distance between the distal pseudoknot and components of the repA TIR, and the arrangement of the repA initiation and repB termination codons (Fig. 1). The fact that the spacing of these “elements” with respect to each other has been conserved in all the I-complex plasmids and that altering these distances in pMU720 affects repA expression significantly indicates their importance in maintaining efficient rep expression and antisense regulation.

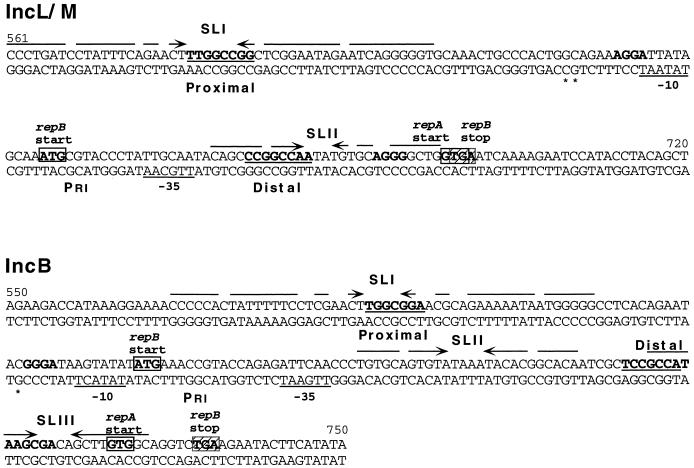

FIG. 1.

Sequence of the replication control regions of IncL/M and IncB. The promoter regions for RNAI (Pri) are labelled, and transcription start sites are indicated by asterisks. Arrows above the sequences represent stem-loop structures (SLI, SLII, and SLIII). The distal and proximal pseudoknot sequences are in boldface type and underlined. SD of the repA and repB genes are in boldface type, and translational start (open) and termination (hatched) codons are boxed.

In this paper, we identify the sequences needed for effective pseudoknot formation in the IncL/M plasmid and show that the stem-loop structure (SLI) involved in forming the pseudoknot is also the target for RNAI. We analyze the elements of the regulatory region of pMU604 that are different from those of pMU720 and show that (i) the repB termination codon can be moved some distance upstream or downstream of the wild-type position with little effect on repA expression; (ii) formation of the pseudoknot inhibits translation of the leader peptide; (iii) improving the repA TIR, by altering the start codon or the spacing between the start codon and SD, results in significant pseudoknot-independent expression of repA; and (iv) the spacing between the distal pseudoknot and repA SD is suboptimal for maximum repA translation in pMU604.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages.

The Escherichia coli K-12 strains used in this study are as follows. JM101 [Δ (lac-proAB) supE thi F′ (traD36 proA+B+ lacIq ZΔM15)] (21) was used for propagation of bacteriophage M13 derivatives. XL1 Blue MRF′ [Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] (Stratagene) was used to grow M13 derivatives which had been mutagenized by the procedure of Vandeyar et al. (38). JP7740 (W3110ΔlacU169 tsx recA56) was used for all β-galactosidase assays with translational and transcriptional lacZ fusions. JP8042 (ΔlacU169 tyrR366 tsx recA56) (44) was used for all β-galactosidase assays to determine the relative copy number of plasmid pMU4003 and its derivatives. Bacteriophage vectors used to clone fragments for sequencing and mutagenesis were M13mp19 (45) and M13tg131 (18).

The plasmids and bacteriophages used and constructed in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and phages used in this study

| Plasmid or phage | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pMU604 | Miniplasmid; Gal IncL/M | (9) |

| pACYC177 | p15A replicon; Ap, Kn | (8) |

| pMU2385 | galK′-lac′Z IncW low-copy-number transcriptional fusion vector; Tp, IncW | (29) |

| pMU2386 | lac′Z IncW low-copy-number translational vector derived from pMU525; Tp, IncW | (19) |

| pMU3265 | pACYC177 derivative containing nt 507–698 of pMU604; Kn, IncL/M | (5) |

| pMU3268 | pACYC177 derivative containing nt 330–634 of pMU604 | (5) |

| pMU3274 | repB-lacZ translational fusion containing nt 1–692 of pMU604; Tp, IncW, IncL/M | (5) |

| pMU3273 | Transcriptional fusion version of pMU3274 | (5) |

| pMU3276 | repA-lacZ translational fusion containing nt 1–769 of pMU604; Tp, IncW, IncL/M | (5) |

| pMU3275 | Transcriptional fusion version of pMU3276 | (5) |

| pMU4003 | Dual-origin plasmid derived from pMU4365 and pMU604 for use in copy number determinations | This study (42) |

| Phages | ||

| mpMU616 | M13tg131 derivative with nt 1–692 of pMU604 on a PstI-BamHI fragment | (5) |

| mpMU681 | M13tg131 with the 201-bp PstI fragment of pMU3265 containing nt 507–698 of pMU604 | (5) |

| mpMU699 | M13mp19 derivative with nt 1–769 of pMU604 on a HindIII-BamHI fragment | This study |

| mpMU745 | M13mp19 derivative with nt 1–769 of pMU604 on a HindIII-BamHI fragment carrying the PRNAI mutation | This study |

Abbreviations: Ap, ampicillin resistance; Tp, trimethoprim resistance; Kn, kanamycin resistance. Mutations introduced into rep-lacZ fusion plasmids, pMU4003, pACYC177, and M13 derivatives are described in Results.

Media and chemicals.

The minimal medium used was half-strength buffer 56 (23) supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose or other carbon sources as indicated, thiamine (10 μg/ml), and necessary growth factors. Chemicals and enzymes were purchased commercially and were not purified further. [α-35S]dATPαS (1,000 Ci/mmol; 8.4 Ci/ml) was obtained from NEN Research Products. Kanamycin was used at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml, ampicillin was used at 50 μg/ml, trimethoprim was used at 10 μg/ml in minimal medium and 40 μg/ml in nutrient medium, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactogyranoside (IPTG) was used at 1 mM, and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) was used at 25 μg/ml.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Plasmid and bacteriophage DNA was isolated and manipulated as described by Sambrook et al. (32). DNA sequencing was performed by the method of Sanger et al. (33), except that T7 DNA polymerase was used instead of the Klenow fragment and terminated chains were uniformly labelled with [α-35S]dATPαS. In vitro site-directed mutagenesis was performed on single-stranded M13 templates with the United States Biochemical Corp. kit and oligonucleotides purchased commercially from Bresatec Ltd. or Gibco BRL. The presence of mutations was screened for and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Construction of the lacZ fusion plasmids.

The construction of the translational (pMU3276 and pMU3274) and transcriptional (pMU3275 and pMU3273) plasmids has been described previously (5). Plasmids pMU3276 (repA-lacZ) and pMU3274 (repB-lacZ) are derivatives of pMU2386 (19) which carry nucleotides (nt) 1 to 769 and 1 to 692 of pMU604, respectively. Thus in the repA-lacZ and repB-lacZ translational vectors, codon 26 of repA and codon 16 of repB, respectively, are fused in frame with codon 8 of lacZ. β-Galactosidase expression in the translational fusions pMU3276 and pMU3274 is therefore dependent on transcription from the rep mRNA promoter(s) and translation from the fused gene (repA or repB). The transcriptional lacZ fusion vectors pMU3275 (repA-) and pMU3273 (repB-) were constructed by inserting nt 1 to 769 and nt 1 to 692 of pMU604, respectively, into pMU2385. In these fusions, β-galactosidase expression is dependent on transcription from the rep mRNA promoter(s) and translation initiation from galK. Mutant derivatives of the repA-lacZ and repB-lacZ fusions were constructed by replacing the original fragments with those containing the mutation to be tested.

pACYC177 derivatives.

The construction of pMU3265 and pMU3268 has been described previously (5). pMU3265 is a derivative of pACYC177 (lacking the bla promoter to prevent transcription into the insert) which carries nt 507 to 698 of pMU604 and therefore expresses RNAI (but not rep mRNA) from its own promoter and is used to deliver extra copies of RNAI. The pACYC177 derivative, pMU3268, carries nt 330 to 634 of pMU604 and expresses the leader region of repBA mRNA including SLI, which is the presumed target for RNAI, but does not express RNAI as it lacks the rnaI promoter. pMU3268 is used to titrate out RNAI molecules.

Construction of plasmids for use in copy number determinations.

The chimeric plasmid pMU4003 was derived from pMU4365 (42) and contains the IncL/M replicon from pMU604 (5) and the pMB1 replicon from pAM34 (11). The pMB1 replicon is modified such that the essential preprimer RNA is transcribed from the lacZ promoter operator. The vector also contains the lacIq gene, so that in the absence of a lacZ inducer (e.g., IPTG), replication from the pAM34 replicon is fully repressed (and thus reliant on the IncL/M replicon). Induction of the pAM34 replicon with IPTG allows the rescue of mutations which preclude replication from the IncL/M replicon. pMU4003 allows the determination of relative plasmid copy numbers by making use of the lacZ reporter gene, which is expressed constitutively from the tyrP promoter in a tyrR strain (JP8042). The plasmids used in copy number determinations were derived from pMU4003, by replacing nt 1 to 769 of the IncL/M replicon with the 769-bp HindIII-BamHI repA fragments containing the mutations to be tested.

Measurement of β-galactosidase activity.

Plasmids were assayed for lacZ expression in strains JP7740 or JP8042. The β-galactosidase activity of mid-log-phase cultures was assayed as described by Miller (22). Each sample was assayed in duplicate, and each assay was performed at least four times.

RNA secondary-structure predictions.

The program of Zuker et al. was used to predict RNA secondary structures (46).

RESULTS

Identifying bases important for pseudoknot formation.

It has been shown that pairing between two 8-base complementary sequences in the rep mRNA of pMU604 is important for repA expression (5). However, it has not been established how many of these complementary bases must pair for the pseudoknot to form and activate translation of repA mRNA. Therefore, site-directed mutagenesis was used to substitute individually each of the 16 bases to prevent base pairing at the affected position (Fig. 2). Since the expression of repA is totally dependent on pseudoknot formation (5), the effect of each substitution on the pseudoknot interaction was determined by assessing its effect on the expression of β-galactosidase from a repA-lacZ translational fusion. To evaluate the effects of these mutations on the regulation of repA, assays were performed in the presence of multicopy plasmids with no inserts (vector) or ones carrying either rnaI (producing saturating levels of RNAI, resulting in maximal inhibition) or the gene for the transcript which is complementary to RNAI (producing saturating levels of target RNA to remove RNAI produced by the fusion, resulting in derepression of repA).

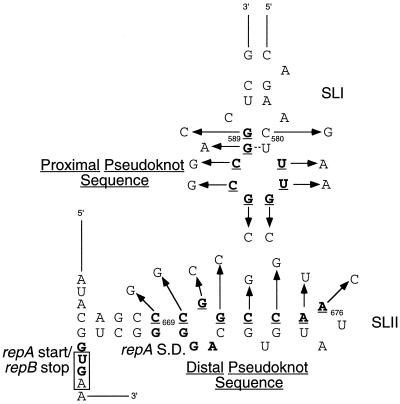

FIG. 2.

Putative stem-loop structures I and II (SLI and SLII) depicting substitutions made to the proximal and distal pseudoknot bases (boldface and underlined nucleotides). The repA SD and start codon are in boldface type, and the repB termination codon is boxed.

All the DNA fragments used to construct the translational fusions described in this paper were also introduced into the lacZ transcriptional fusion vector pMU2385 (29). None of the mutations had a significant effect on transcription (data not shown).

(i) Mutations in the distal sequence.

From Table 2 it can be seen that mutations in the first two bases of the distal pseudoknot sequence (C669G and C670G) had only a slight effect on repA expression. However, both substitutions resulted in significant RNAI-insensitive expression. This may be due to pseudoknot-independent initiation of translation, since the mutations are predicted to destabilize the stem-loop structure sequestering the repA TIR (SLII). Substitutions at positions 671 to 674 reduced β-galactosidase activity by more than 30-fold, showing that these bases are critical for pseudoknot formation. Altering nt A675 and A676 led to ∼2.5 and ∼4.6-fold reduction in β-galactosidase activity, respectively, indicating that these bases play a lesser role in the formation or stability of the pseudoknot.

TABLE 2.

Effect of mutations in the two 8-base complementary sequences on β-galactosidase expression from repA-lacZ fusions

| Mutation present in repA-lacZ fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | Target (pMU3268) | |

| None | 156 ± 36 | 0.1 | 1,110 ± 106 |

| C669G | 204 ± 23 | 16 ± 2 | 705 ± 75 |

| C670G | 172 ± 24 | 14 ± 3 | 687 ± 71 |

| G671C | 2 ± 0.4 | <0.1 | 41 ± 8 |

| G672C | 0.9 | 0.1 | 10 ± 1 |

| C673G | 4 ± 0.8 | 0.7 | 40 ± 2 |

| C674G | 5 ± 1 | 0.5 | 69 ± 6 |

| A675U | 62 ± 12 | 0.1 | 355 ± 37 |

| A676C | 34 ± 6 | 0.1 | 212 ± 19 |

| PRNAIb | 920 ± 88 | 0.3 | 950 ± 99 |

| U582Ab | 204 ± 11 | 0.8 | NAc |

| U583Ab | 107 ± 9 | 0.7 | NA |

| G584Cb | 23 ± 4 | 2 ± 0.5 | NA |

| G585Cb | 23 ± 5 | 14 ± 7 | NA |

| C586Gb | 43 ± 5 | 19 ± 3 | NA |

| C587Gb | 1,103 ± 89 | 374 ± 40 | NA |

| C587G + C670Gb | 159 ± 9 | 37 ± 15 | NA |

| G588Ab | 225 ± 25 | 13 ± 2 | NA |

| G589Cb | 360 ± 22 | 60 ± 3 | NA |

β-Galactosidase activities were measured by the method of Miller (22), and the values shown are the average of at least four independent determinations. Vector (pACYC177) or its derivatives were present in trans. RNAI (pMU3265) carries nt 507 to 698 of pMU604 and therefore expresses RNAI. Target (pMU3268) carries nt 330 to 634 of pMU604 and thus expresses the leader sequence of rep mRNA which is complementary to RNAI but does not express RNAI (5). These plasmids do not carry lacZ. The parental plasmid pMU2386 produced <1.0 U of β-galactosidase activity.

All the mutations were introduced into a repA-lacZ fusion carrying the PRNAI mutation.

NA, not applicable.

(ii) Mutations in the proximal sequence.

Since the proximal pseudoknot sequence is part of the presumed target of RNAI, introduction of base substitutions may affect the interaction between RNAI and SLI, thus altering the expression of repA. To avoid this complication, all substitutions in the proximal pseudoknot sequence were introduced into a repA-lacZ translational fusion in which the promoter for RNAI was inactivated by changing the first base of the −35 sequence (T662) to a nonconsensus G residue (PRNAI mutation; see Fig. 3 and 4). This mutation increased repA expression by ∼sixfold but did not affect regulation by RNAI (Table 2). Titration of RNAI by excess target in trans did not increase expression, indicating that RNAI synthesis had been abolished.

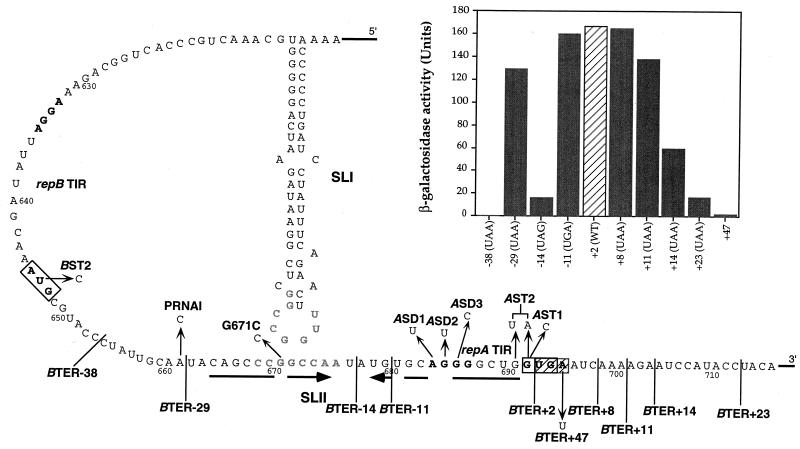

FIG. 3.

The leader region of the repA mRNA of pMU604 showing putative SLI and SLII structures, the latter indicated by arrows below the sequence. Individual mutations are indicated by arrows or labelled with solid bars coming off the sequence such that the first base of the repB stop codon is the first base on the right of the bar. SD are in boldface type, start codons are boxed, and the wild-type repB termination codon is hatched. Proximal and distal pseudoknot bases are in shaded print. The effect of moving the repB termination codon on repA expression is summarized in the graph in the top right-hand corner of the figure. Bases altered to introduce new repB stop codons and the position of termination relative to G692 of the repA start codon (+1) are shown on the bottom axis of the graph. WT, wild type.

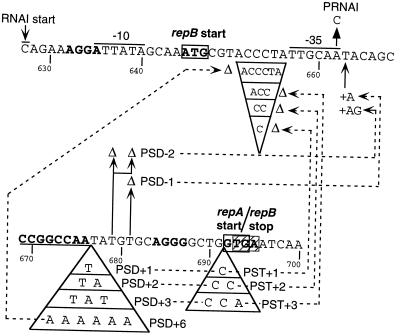

FIG. 4.

Partial nucleotide sequence of the replication control region of pMU604 showing mutations affecting the spacing between distal pseudoknot sequence (boldface and underlined) and TIR of repA. The mutations are labelled as those which (i) insert bases between distal sequence and repA SD (PSD+1 to PSD+6); (ii) delete bases between distal sequence and repA SD (PSD−1, PSD−2) and (iii) insert bases between the distal sequence and repA start codon (PST+1, PST+2, PST+3). Compensatory insertions or deletions in the repB coding region are linked to the appropriate mutations by stippled arrows. The promoter region for RNAI is overlined, and the transcriptional start site is indicated. SD are in boldface type, translational start codons are boxed, and the repB stop codon is hatched.

Substitution of bases at positions 582 and 583 resulted in a ∼4.5- and ∼8.6-fold reduction in repA expression, respectively. Substitutions at positions 584, 585, and 586 led to greater than 21-fold reduction in repA expression, confirming their crucial role in pseudoknot formation. Surprisingly, the C587G mutation, which on the basis of analyses presented in the preceding section was expected to severely affect pseudoknot formation, had little effect on repA expression. A possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that a G587 residue is able to “slip” and pair with C670 in the distal sequence. To test this hypothesis, we altered C670 to G, which would prevent any interaction with C587G. Introduction of this second mutation into the repA-lacZ fusion carrying the C587G substitution reduced β-galactosidase expression by ∼sevenfold, suggesting that the base at position 587 in the proximal sequence has the flexibility to interact with either a complementary nucleotide at position 671 or one at position 670. Substitutions at positions 588 and 589 reduced repA-lacZ expression by ∼4- and ∼2.6-fold, respectively. Both these mutations affect the hairpin-closing base pairs of SLI, with the G588A substitution increasing and the G589C mutation decreasing the stability of this hairpin. The reduced expression seen with these two mutations may therefore be a result of perturbations to the structure of SLI.

Substitution of nt 585 to 587 resulted in almost complete loss of sensitivity to RNAI, showing that SLI is indeed the target of RNAI and that bases 585 to 587 are critical to the interaction between these two RNA molecules (Table 2). Thus, the proximal pseudoknot bases involved in pairing with the distal sequence to form the pseudoknot are also involved in the interaction with RNAI. The inability of RNAI to efficiently regulate repA expression from mutants G588A and G589C may be due to alterations in stability or secondary structure of SLI, since both these features are important in the interaction between antisense RNAs and their targets (12, 15, 36, 37, 39).

Is the position of the repB stop codon optimal for pseudoknot-dependent translational coupling?

Translation of the repA gene in pMU604 is completely dependent on translation of an upstream leader peptide, repB (5). This dependency is thought to be due to the sequestration of the SD of repA within a stem-loop structure (SLII; Fig. 2), requiring translation of repB to make the TIR of repA accessible. The termination codon of repB overlaps the initiation codon of repA by 1 nt, an arrangement considered to be most efficient for coupled genes. To determine if the 1-nt overlap between the rep genes was optimal for coupling between repA and repB and to delineate the “window” for efficient coupling, we used site-directed mutagenesis to move the termination codon of repB either 5′ or 3′ of its normal location at position 693 (Fig. 3). The effect of these mutations on expression of repA and repB was determined with appropriate translational fusions.

As seen in Table 3, moving the stop codon 12 nt upstream of its normal position (to −11; BTER−11 mutation) had no significant effect on repA-lacZ expression. Although this mutation places the repB stop codon just 5 nt downstream of the distal pseudoknot sequence, repA-lacZ expression was still fully dependent on pseudoknot formation as shown by the introduction of the G671C substitution. Moving the repB stop codon 3 nt further (to −14) reduced β-galactosidase activity by ∼10-fold in the presence of wild-type levels of RNAI (vector), and ∼5-fold under fully derepressed conditions (target). Moving the repB stop codon a further 15 nt (to −29) so that it lies 5 nt upstream of the functionally defined distal pseudoknot sequence (5′-GGCCAA-3′) restored the regulated expression (vector) of repA-lacZ to almost wild-type levels. However, under fully derepressed conditions the β-galactosidase activity of this mutant was fourfold lower than that of the wild type. Similarly, when no RNAI was produced (i.e., in the PRNAI + BTER−29 mutant), expression was reduced 4.4-fold, confirming that termination at position −29 interferes with pseudoknot formation. Introduction of the pseudoknot-inactivating mutation, G671C, showed that expression of the BTER−29 fusion was dependent on pseudoknot formation. The expression of repA in the −29 mutant was not due to inefficient termination of repB translation at the new stop codon, since this mutation reduced β-galactosidase activity by more than 99% when introduced into a repB-lacZ fusion (refer to Materials and Methods for construction of repB-lacZ fusions [data not shown]). Introduction of the AST1 mutation, which changes the repA start codon from GUG to CUG (Fig. 3), completely abolished repA-lacZ expression, confirming that repA translation in the −29 mutant was initiating at position 692. Moving the repB stop codon 39 nt (to −38) upstream of its normal position abolished almost all expression from the repA-lacZ fusion.

TABLE 3.

Effect of altering the position of the repB stop codon on β-galactosidase expression from repA-lacZ fusions

| Mutation present in repA-lacZ fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | Target (pMU3268) | |

| BTER−38b | 0.3 | <0.1 | 2 ± 0.5 |

| BTER−29 | 129 ± 29 | <0.1 | 275 ± 21 |

| BTER−29 + G671C | 0.1 | <0.1 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| BTER−29 + AST1 | 2 ± 0.3 | <0.1 | 8 ± 0.9 |

| PRNAI | 925 ± 178 | 0.2 | 895 ± 127 |

| PRNAI + BTER−29 | 212 ± 39 | <0.1 | 205 ± 44 |

| BTER−14 | 16 ± 4 | 0.3 | 226 ± 22 |

| BTER−11 | 160 ± 31 | 3 ± 0.1 | 863 ± 93 |

| BTER−11 + G671C | 6 ± 1.5 | 1 ± 0.2 | 48 ± 4 |

| WT (+2)c | 167 ± 30 | 0.1 | 1,118 ± 289 |

| BTER+8 | 165 ± 45 | <0.1 | 863 ± 131 |

| BTER+11 | 138 ± 19 | <0.1 | 705 ± 13 |

| BTER+11 + G671C | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| BTER+14 | 60 ± 21 | <0.1 | 654 ± 94 |

| BTER+23 | 17 ± 2 | <0.1 | 157 ± 20 |

| BTER+47 | 2 ± 0.2 | <0.1 | 19 ± 0.6 |

See Table 2, footnote a.

The numerical suffix refers to the position of the first base of the repB stop codon with respect to the repA start codon (+1).

WT, wild type.

Changing the repB stop codon to a sense codon (UGA→UGU), which results in translation of repB reading through to the next in-frame stop codon (nt 738; +47), abolished almost all the β-galactosidase expression from a repA-lacZ fusion (Table 3) and allowed new termination codons to be introduced downstream of the wild-type position at +2. Moving the termination codon of repB 6 nt (to +8) or 9 nt (to +11) downstream of the wild-type position had little effect on the expression of β-galactosidase from a repA-lacZ fusion, whereas moving it 12 and 21 nt (mutants +14 and +23, respectively) resulted in successive decreases in repA expression. Although expression of repA-lacZ in the +23 mutant was seriously impaired, it was still ∼10-fold higher than in the +47 mutant.

The data indicate that (i) the 1-nt overlap between the two rep genes is not important for efficient coupling; (ii) the position of the repB stop codon is not critical, provided that it is located at least 5 bases away from the distal pseudoknot sequence but close enough so that the terminating ribosome disrupts SLII and maintains the repA TIR in an accessible state; and (iii) transient disruption of SLII (when termination occurs at positions +47) is not sufficient to ensure coupling between repB and repA.

Does the pseudoknot affect repB expression?

Because the pseudoknot forms within the coding region of the repB mRNA and only 21 bases downstream of the start codon, it may present an obstruction to the ribosomes initiating and/or translating this mRNA. Therefore, to determine whether the pseudoknot has an effect on repB translation, the G671C substitution, which abolishes pseudoknot formation, was introduced into the wild-type and RNAI− (carrying the PRNAI mutation) repB-lacZ fusions. Introduction of the G671C mutation into the wild-type fusion resulted in a slight decrease in expression of β-galactosidase (Table 4). By contrast, introduction of this mutation into the RNAI− fusion resulted in a ∼3.5-fold increase in expression. The simplest interpretation of these data is that the pseudoknot interferes with the translation of repB but that this effect is compensated for when RNAI is present. This is presumably because the distal pseudoknot bases are competing with RNAI for binding to the proximal bases, thus increasing the expression of repB by relieving inhibition by RNAI. Therefore, in the presence of RNAI, the pseudoknot interaction is predicted to have both a positive and a negative effect on the expression of repB.

TABLE 4.

Effect of inactivating pseudoknot base pairing on expression from a repB-lacZ fusion

| Mutation present in repB-lacZ fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | Target (pMU3268) | |

| None | 471 ± 45 | 28 ± 3 | 1,178 ± 62 |

| G671C | 379 ± 36 | 26 ± 1 | 1,350 ± 38 |

| PRNAI | 632 ± 34 | 38 ± 3 | 706 ± 42 |

| PRNAI + G671C | 2,229 ± 486 | 36 ± 5 | 2,049 ± 109 |

See Table 2, footnote a.

Can a more efficient start codon make expression of repA less reliant on pseudoknot?

The GUG start codon and the 4-base spacing between this GUG and the SD in repA, both of which are predicted to be suboptimal for initiation of translation (31), may contribute to the dependence of repA expression on the pseudoknot. To determine whether this is the case, the GUG of repA was replaced by the more efficient start codon AUG, without affecting the position of repB termination (AST2 mutation, UGGUGA→UUAUGA [underlining represents start codon, and boldface indicates overlapping stop codon within the sequence]).

As seen in Table 5, the AST2 mutation increased the expression of repA ∼2.9-fold in the presence of vector, with a significant component of this expression being insensitive to regulation by RNAI. Moreover, ∼40% of repA-lacZ expression in the AST2 mutant did not require a pseudoknot, as shown by the introduction of the G671C substitution. Uncoupling the expression of repA from that of repB by introduction of a mutation which replaces the AUG start codon of repB by ACG (BST2) or one that prematurely terminates repB (BTER−38) showed that expression of repA in AST2 is largely dependent on repB. Nevertheless, there was a significant level of repB-independent expression of repA in the AST2 mutant, which was higher in the presence of the BST2 substitution than in the presence of the BTER−38 substitution. Given the short distance between the BTER−38 stop codon and the repA start codon, this difference might be caused by the ribosome terminating repB blocking access to the repA TIR. Introduction of the BTER−38 mutation onto a fragment containing both the AST2 and G671C substitutions abolished β-galactosidase activity under all conditions, showing that repA was not expressed when both repB translation and pseudoknot formation were blocked.

TABLE 5.

Effect of an AUG repA start codon on expression from repA-lacZ fusions

| Mutation present in repA-lacZ fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | Target (pMU3268) | |

| None | 120 ± 7 | 0.2 | 990 ± 101 |

| AST2 | 352 ± 50 | 44 ± 3 | 2,347 ± 192 |

| AST2 + G671C | 141 ± 34 | 25 ± 1 | 787 ± 52 |

| AST2 + BTER−38 | 33 ± 3 | 6 ± 0.6 | 89 ± 9 |

| AST2 + G671C + BTER−38 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.7 |

| BTER−38 | 0.3 | <0.1 | 2 ± 0.5 |

| BST2b | 4 ± 1 | <0.1 | 28 ± 4 |

| AST2 + BST2 | 87 ± 7 | 8 ± 0.7 | 299 ± 30 |

To determine the effects of these mutations on IncL/M plasmid replication, the substitutions were introduced into pMU4003. This chimeric plasmid contains a modified ColE1-like replicon which is fully repressible, so that in the absence of a lacZ inducer, all replication must initiate from the second replicon derived from the IncL/M plasmid. Neither the AST2 nor the AST2 + G671C mutations could be cloned into pMU4003, probably because the high levels of RNAI-insensitive repA expression result in runaway replication. The very low levels of repA expression in the AST2 + G671C + BTER−38 mutant resulted in an IncL/M replicon which was unable to replicate and had to be rescued by the induction of the ColE1-like replicon of pMU4003 (data not shown).

Is the spacing between the pseudoknot and repA TIR critical for activation of repA expression?

In the IncB plasmid the distal pseudoknot sequence adjoins the SD of repA, and even small insertions between these two sequences have profound effects on expression of repA (41). It was therefore noteworthy that in pMU604 the distal pseudoknot sequence lies 8 bases upstream of the putative SD of repA (AGGG at position 684 [Fig. 1]). On the other hand, the 16-base spacing between the distal pseudoknot sequence and the repA start codon in pMU604 resembles the 14-base spacing seen in the IncB plasmid, raising the possibility that this latter arrangement is important for activation of translation of repA mRNA in the two plasmids. To determine whether the distance of the pseudoknot to the SD or that to the start codon, or both, is important for repA expression in pMU604, the latter sequences were moved relative to the distal pseudoknot sequence (Fig. 4). In pMU604, the −35 region of rnaI lies within the 21-base sequence separating the start codon of repB from the distal pseudoknot sequence. Consequently, the compensatory mutations needed to maintain the reading frame of repB had to be introduced within or adjacent to the promoter of rnaI and so might be expected to affect the expression of rnaI. Therefore, these studies were performed on a repA-lacZ fusion carrying the PRNAI mutation.

To confirm that the AGGG at position 684 was the SD of repA, the effects on repA expression of changing this sequence away from consensus to UGGG (ASD1), AUGG (ASD2), or AGCG (ASD3) were determined (Fig. 3). All three mutants showed a reduction in expression of repA-lacZ, with ASD2 having the greatest and ASD3 having the smallest impact (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Effect of altering the putative repA SD on expression from repA-lacZ fusions

| Mutation present in repA-lacZ fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | Target (pMU3268) | |

| None | 152 ± 44 | 0.2 | 1,346 ± 127 |

| ASD1 | 63 ± 11 | <0.1 | 383 ± 30 |

| ASD2 | 24 ± 3 | <0.1 | 272 ± 15 |

| ASD3 | 112 ± 19 | 0.6 | 763 ± 61 |

See Table 2, footnote a.

(i) Effect of increasing the distance between the distal pseudoknot sequence and the start codon of repA.

Insertion of bases at position 691 increases the distance between the pseudoknot and the start codon without affecting the distance between the pseudoknot and the SD (Fig. 4). Examination of the effects of such insertions revealed that whereas addition of 1 base (PST+1) increased the expression of repA-lacZ by 1.4-fold, addition of 2 (PST+2) or 3 (PST+3) bases lowered the expression by 2.3- and 1.4-fold, respectively (Table 7). Given that all three mutants showed significant levels of RNAI-insensitive expression and that the insertions increased the spacing between the SD and the start codon and thus may have improved the TIR of repA, it was possible that the true extent of the effects of these mutations was being masked by an increase in pseudoknot-independent expression. Therefore, the effect on these mutants combined with the G671C substitution, which prevents formation of the pseudoknot, was examined. Pseudoknot-independent expression of repA-lacZ in the PST+1 mutant represented ∼8% of total expression, which was no different from in the wild type. However, in the PST+2 and PST+3 mutants, pseudoknot-independent expression represented 32 and 47%, respectively, of the total expression (Table 7), suggesting that the levels of pseudoknot-dependent expression in these two mutants were comparable. Expression of repA-lacZ in the PST+3 mutant was dependent on expression of repB, indicating that the pseudoknot-independent expression was not due to disruption of SLII. Furthermore, the pseudoknot-independent expression of repA in the PST+ mutants was largely regulated by RNAI, presumably via the regulation of repB expression.

TABLE 7.

Effect of increasing the spacing between the distal pseudoknot sequence and repA start codon on expression from repA-lacZ fusions carrying the PRNAI mutation

| Mutation present in repA-lacZ fusionb | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | |

| PRNAI | 908 ± 67 | 0.3 |

| PST+1 | 1,250 ± 145 | 7 ± 0.7 |

| PST+2 | 398 ± 32 | 11 ± 0.8 |

| PST+3 | 632 ± 69 | 13 ± 2 |

| PST+1 + G671C | 105 ± 5 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| PST+2 + G671C | 129 ± 18 | 6 ± 1 |

| PST+3 + G671C | 295 ± 34 | 9 ± 2 |

| PST+3 + BTER−38 | 8 ± 1 | 0.7 |

| PST+3 + G671C + BTER−38 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| PRNAI + G671C | 77 ± 10 | <0.1 |

| PRNAI + BTER−38 | 9 ± 1 | <0.1 |

| PRNAI + G671C + BTER−38 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

(ii) Effect of inserting bases between the pseudoknot and SD.

We examined the effect on repA expression of inserting bases between the distal pseudoknot and repA SD (PSD+1 through PSD+6 [Fig. 4]) at position 676. To maintain the repB reading frame, the equivalent number of bases were deleted between positions 651 to 656. Inserting 1, 2, 3, and 6 nt between the distal pseudoknot and repA SD caused successive decreases in the level of repA expression (Table 8) without loss of regulation. Introduction of the G671C substitution showed that repA expression in the PSD+ mutants was pseudoknot dependent (data not shown).

TABLE 8.

Effect of altering the number of bases between the distal pseudoknot sequence and repA SD on expression from repA-lacZ fusions

| Mutation present in repA-lacZ fusion | β-Galactosidase activity (U) with coresident plasmid present in transa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Vector (pACYC177) | RNAI (pMU3265) | |

| PRNAIb | 908 ± 67 | 0.3 |

| PRNAI + G671Cb | 77 ± 10 | <0.1 |

| PSD+1b | 538 ± 39 | 0.3 |

| PSD+2b | 474 ± 44 | 0.7 |

| PSD+3b | 160 ± 15 | 0.6 |

| PSD+6b | 27 ± 2 | 0.6 |

| PSD−1b | 2,102 ± 376 | 0.3 |

| PSD−2b | 2,956 ± 136 | 3 ± 0.4 |

| PSD−1 + G671Cb | 224 ± 70 | <0.1 |

| PSD−2 + G671Cb | 31 ± 8 | 0.6 |

| None | 98 ± 17 | 0.1 |

| PSD−1WT | 558 ± 55 | <0.1 |

(iii) Effect of deleting bases between the pseudoknot and SD.

The effect of deleting 1 base (PSD−1) or 2 bases (PSD−2) between the distal pseudoknot sequence and repA SD was examined by deleting nt 681 or nt 679 and 681, respectively. To maintain the repB reading frame, a single or double insertion was introduced at nt 663. Deleting 1 and then 2 nt caused successive increases in repA expression (Table 8), indicating that the wild-type spacing is suboptimal for maximal repA translation. Expression in these mutants was pseudoknot dependent and regulated by RNAI. To determine how an improvement in spacing between the distal pseudoknot and repA SD affected the copy number of the IncL/M plasmid, the PSD−1 mutation was introduced into the wild-type repA fragment (PSD−1WT) and then cloned into the repA-lacZ translational fusion and into the IncL/M replicon of pMU4003. The PSD−1WT mutation increased repA-lacZ expression 6-fold in the presence of vector (Table 8) and 12-fold under derepressed conditions (data not shown) and was fully regulated by RNAI. The pMU4003 derivative had a copy number threefold higher than the wild type (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Analysis of the contribution of individual bases in the proximal and distal pseudoknot sequence to the pseudoknot interaction revealed that 4 of the 8 bases in the distal sequence (nt 671 to 674) were essential and 2 others (nt 675 and 676) were important for the formation or function of the pseudoknot. The bases at positions 669 and 670 appear to play a minor role, possibly in stabilizing the tertiary structure. Analyses of the proximal sequence largely confirmed these conclusions, showing that nt 584 to 586 are critical and nt 582 and 583 are important for pseudoknot formation. Interestingly, mutant C587G, which can no longer pair with the G at position 671 in the distal pseudoknot sequence, appears instead to pair with C670 to produce wild-type levels of repA expression. Elimination of this alternative pairing by changing C670 to G reduced expression ∼7-fold. These data show that all 6 nt in the hairpin loop of SLI are involved in pseudoknot formation or function. The contribution of the loop-closing bases G588 and G589 to pseudoknot formation was less clear, because their substitution was predicted to affect the structure and thermodynamic stability of the upper stem-loop region of SLI. In the distantly related IncB plasmid pMU720, mutations altering the conformation of the SLI-equivalent structure impair pseudoknot-enhanced expression of repA (36, 43). Thus, in pMU604, pairing over 6 of the 8 complementary pseudoknot bases is necessary for effective pseudoknot formation. In pMU720 and ColIb-P9, only the central 5 of the 7 complementary bases are important for pseudoknot formation (2, 43). Moreover, only 4 of the 5 important proximal bases of pMU720 and ColIb-P9 are in the 4- to 6-base loop of the SLI-equivalent structure, whereas in pMU604, all 6 important bases are situated in the 6- to 8-base hairpin loop domain of SLI. This difference in the positioning of the proximal pseudoknot bases may result in differences in their presentation, thus affecting the process of pseudoknot formation.

Substitution of nt 585 to 587 (5′-GCC-3′), three of the central bases of the proximal pseudoknot sequence, resulted in inefficient regulation of repA expression by RNAI, showing that these three bases are critical for both the intramolecular (pseudoknot) and intermolecular (with RNAI) interactions. Therefore, antisense inhibition in the IncL/M plasmids resembles that of the I-complex group of plasmids where binding of the antisense RNA to its target stem-loop structure sequesters the bases crucial for the pseudoknot interaction (1, 3, 29, 43).

The overlapping translation stop and start signals of repB and repA were shown to be unimportant for efficient coupling between the two genes, since the termination codon of repB could be moved as much as 12 nt upstream (−11) and 9 nt downstream (+11) of its normal position with little effect on repA expression (Table 3). Pseudoknot formation was shown to require termination of a ribosome at a position which is predicted to disrupt and prevent refolding of the stem-loop structure (SLII) sequestering the distal pseudoknot bases and repA TIR. However, a ribosome terminating very close to the distal pseudoknot bases may be expected to physically interfere with formation of the pseudoknot structure. Such an interaction could account for the reduced levels of repA-lacZ expression in the −14 and −29 mutants. Although data from ribosome protection and toeprinting analyses (7, 14, 16) predict that a ribosome terminating at position −11 would cover the distal pseudoknot bases, the pseudoknot was shown to form in mutant BTER−11, suggesting that the height of the ribosome-mRNA tract is great enough to accommodate not only stable and complex secondary structures but also tertiary structures (16, 30). It is not known how the ribosome which is translating repB melts the secondary structure (i.e., SLII) yet permits tertiary structures to form or why repA synthesis in pMU720 and ColIb-P9 is consistently higher when SLIII is melted by translation of repB compared to when SLIII is disrupted in the absence of repB expression (3, 41). Moreover, the pseudoknot forms upstream of the SD in a region which is required to be unstructured for efficient initiation of translation (16, 20). The introduction of stable secondary structures 2 to 6 nt upstream of the SD interferes with the binding of 30S complexes in vitro and translation initiation in vivo (20, 43). By contrast, the pseudoknot of the I-complex plasmids actively enhances the translation of rep (3, 41). On the other hand, pseudoknot formation reduces translation of the leader peptide. Since the proximal pseudoknot sequence is only 21 nt away from the repB SD, the “pseudoknotted” mRNA may hinder the access of ribosomes to the repB TIR. It is not known whether the ribosome translating repB requires the pseudoknot structure to reinitiate translation at the repA TIR or whether formation of the pseudoknot promotes de novo binding of 30S ribosomal subunits from the cellular pool. Since translating ribosomes are capable of disrupting stable secondary structures (17) a ribosome translating repB should be able to disrupt a preformed pseudoknot structure. If a single ribosome translates both repB and repA, the unfolding of SLII by the terminating ribosome would allow pseudoknot formation and reinitiation at the repA TIR. Reducing the probability of a second ribosome initiating the translation of RepB during this period would lower the frequency of disruption of the pseudoknot, allowing more time for reinitiation to occur. The fate of the pseudoknot after a single round of translation in vivo remains to be investigated, although data from binding experiments conducted in vitro suggested that the pseudoknot interaction in pMU720 may be reversible (35). If the pseudoknot acts to recruit ribosomes from the cellular pool, longer persistence of the pseudoknot, which would be more likely in the absence of further translation of repB, would allow multiple rounds of initiation to occur at the repA TIR. Since the Rep proteins of the I-complex plasmids are cis acting (24–26) and since it is likely that more than one molecule of Rep is required to initiate replication at the origin, it may be advantageous for multiple rounds of repA translation to occur once the mRNA escapes RNAI control. In both scenarios, persistence of the pseudoknot overcomes the need for repB translation. Experiments are in progress in an effort to test these models.

The precise mechanism by which the pseudoknot activates repA translation in the IncL/M and I-complex plasmids is unknown, but is postulated to involve a direct interaction between the ribosome and pseudoknot which may promote recognition of an inefficient repA TIR (1, 3, 29, 41). This notion is consistent with the finding that in IncL/M, changing the start codon to a more efficient one or creating a more optimal spacing between the SD and start codon increased the level of pseudoknot-independent expression markedly. However, over 90% of the repA expression in these mutants was reliant on translation of repB, showing that an improvement in the repA TIR results in direct or pseudoknot-independent coupling between repB-repA. Improving the repA TIR was concomitant with loss of sensitivity to inhibition by RNAI, illustrating the inefficiency of regulating repA expression indirectly via the leader peptide. The consequence of this loss of regulation appeared to be runaway replication, since these mutants could not be cloned into the IncL/M replicon of the chimeric plasmid, pMU4003. In pMU720, significant pseudoknot-independent expression was seen when the SD of repA was improved but not when the start codon was replaced by AUG (40, 41). Differences between the two SD sequences and their distances from the start codon, as well as the fact that in pMU720 the entire TIR is sequestered in SLIII, may account for the different requirements for the establishment of pseudoknot-independent repBA coupling in pMU604 and pMU720. Since regulating repA indirectly via the leader peptide is clearly inefficient, both pMU604 and pMU720 appear to have evolved similar mechanisms to prevent direct coupling between repB and repA, such that both the expression and regulation of repA rely on a pseudoknot structure. Although IncL/M and IncB plasmids use similar mechanisms for the expression and regulation of their Rep proteins, they are only distantly related, showing less than 50% sequence identity at the DNA level both overall and in the region involved in regulation of repA expression (data not shown).

Activation of repA translation by pseudoknot formation was shown to be sensitive to the distance separating the pseudoknot and the repA TIR. When the distal sequence and repA start codon were moved further apart, there were two opposing effects: (i) the efficiency of effective pseudoknot formation was reduced, but (ii) the level of pseudoknot-independent expression increased presumably due to more optimal spacing between the SD and start codon of repA (from wild-type spacing of 4 nt to 7 nt for PST+3). On the other hand, inserting bases between the distal pseudoknot sequence and repA SD, which simultaneously altered the spacing relative to the start codon, progressively decreased repA expression whereas deleting sequences increased repA expression. These data indicate that the spacing between the pseudoknot and repA SD is crucial for effective pseudoknot formation and that the spatial arrangement is suboptimal in IncL/M. Preliminary copy number determinations on the minimal replicon indicated that pMU604 has a copy number two- to threefold higher than that of pMU720 (6). Since the parent of pMU604, pMU407.1, is a large conjugative plasmid of ∼100 kb (10) and the more optimal spacing in IncL/M increased the plasmid copy number, suboptimal spacing may have evolved to ensure a lower copy number to reduce the metabolic burden on the host.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council. V. Athanasopoulos was a recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Research Award.

We thank I. Wilson for helpful discussions and for supplying plasmid constructs. We thank M. Pont, A. Cosgriff, and T. Betteridge for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asano K, Kato A, Moriwaki H, Hama C, Shiba K, Mizobuchi K. Positive and negative regulations of plasmid ColIb-P9 repZ gene expression at the translational level. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3774–3781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asano K, Mizobuchi K. An RNA pseudoknot as the molecular switch for translation of the repZ gene encoding the replication initiator of IncIα plasmid ColIb-P9. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11815–11825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asano K, Moriwaki H, Mizobuchi K. An induced mRNA secondary structure enhances repZ translation in plasmid ColIb-P9. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24549–24556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asano K, Niimi T, Yokoyama S, Mizobuchi K. Structural basis for binding of the plasmid ColIb-P9 antisense Inc RNA to its target RNA with the 5′-rUUGGCG-3′ motif in the loop sequence. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11826–11838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athanasopoulos V, Praszkier J, Pittard A J. The replication of an IncL/M plasmid is subject to antisense control. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4730–4741. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4730-4741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athanasopoulos, V., J. Praszkier, and A. J. Pittard. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 7.Beyer D, Skripkin E, Wadzack J, Nierhaus K H. How the ribosome moves along the mRNA during protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30713–30717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the p15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey R B, Bird P I, Nikoletti S M, Praszkier J, Pittard J. The use of mini-Gal plasmids for the rapid incompatibility grouping of conjugative R plasmids. Plasmid. 1984;11:234–242. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey R B, Pittard J. Endonuclease fingerprinting of plasmids mediating gentamicin resistance in an outbreak of hospital infections. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1980;58:331–338. doi: 10.1038/icb.1980.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil D, Bouché J-P. ColE1-type vectors with fully repressible replication. Gene. 1991;105:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Givskov M, Molin S. Copy mutants of plasmid R1: effects of base pair substitutions in the copA gene of the replication control system. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;194:286–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00383529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hama C, Takizawa T, Moriwaki H, Urasaki Y, Mizobuchi K. Organization of the replication control region of plasmid ColIb-P9. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1983–1991. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1983-1991.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartz D, McPheeters D S, Traut R, Gold L. Extension inhibition analysis of translation initiation complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)64058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hjalt T, Wagner E G H. The effect of loop size in antisense and target RNAs on the efficiency of antisense RNA control. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6723–6732. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hüttenhofer A, Noller H F. Footprinting mRNA-ribosome complexes with chemical probes. EMBO J. 1994;13:3892–3901. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacques N, Dreyfus M. Translation initiation in Escherichia coli: old and new questions. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1063–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieny M P, Lathe R, Lecocq J P. New versatile cloning and sequencing vectors based on bacteriophage M13. Gene. 1983;26:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawley B, Pittard A J. Regulation of aroL expression by TyrR protein and Trp repressor in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6921–6930. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6921-6930.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malmgren C, Engdahl H M, Romby P, Wagner E G H. An antisense/target RNA duplex or a strong intramolecular RNA structure 5′ of a translation initiation signal blocks ribosome binding: the case of plasmid R1. RNA. 1996;2:1022–1032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messing J. New M13 vectors for cloning. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:20–78. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monod J, Cohen-Bazire G, Cohen M. Sur la biosynthèse de la β-galactosidase (lactase) chez Escherichia coli. La specificité de l’induction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1951;7:585–599. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(51)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori A, Ito K, Mizobuchi K, Nakamura Y. A transcription terminator signal necessary for plasmid ColIb-P9 replication. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:291–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy, S., J. Praszkier, and A. J. Pittard. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 26.Nikoletti S, Bird P, Praszkier J, Pittard J. Analysis of the incompatibility determinants of I-complex plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1311–1318. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1311-1318.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Praszkier J, Bird P, Nikoletti S, Pittard A J. Role of countertranscript RNA in the copy number control system of an IncB miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5056–5064. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5056-5064.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Praszkier J, Wei T, Siemering K, Pittard J. Comparative analysis of the replication regions of the IncB, IncK, and IncZ plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2393–2397. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2393-2397.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Praszkier J, Wilson I W, Pittard A J. Mutations affecting translational coupling between the rep genes of an IncB miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2376–2383. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2376-2383.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ringquist S, MacDonald M, Gibson T, Gold L. Nature of the ribosomal mRNA track: analysis of ribosome-binding sites containing different sequences and secondary structures. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10254–10262. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ringquist S, Shinedling S, Barrick D, Green L, Binkley J, Stormo G D, Gold L. Translation initiation in Escherichia coli: sequences within the ribosome-binding site. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1219–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiba K, Mizobuchi K. Posttranscriptional control of plasmid ColIb-P9 repZ gene expression by a small RNA. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1992–1997. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1992-1997.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siemering K R. Ph.D. thesis. Parkville, Australia: The University of Melbourne; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siemering K R, Praszkier J, Pittard A J. Interaction between the antisense and target RNAs involved in the regulation of IncB plasmid replication. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2895–2906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2895-2906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamm J, Polisky B. Structural analysis of RNA molecules involved in plasmid copy number control. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:6381–6397. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.18.6381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandeyar M A, Weiner M P, Hutton C J, Batt C A. A simple and rapid method for the selection of oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutants. Gene. 1988;65:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner E G H, Nordström K. Structural analysis of an RNA molecule involved in replication control of plasmid R1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:2523–2538. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.6.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson I W. Ph.D. thesis. Parkville, Australia: The University of Melbourne; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson I W, Praszkier J, Pittard A J. Mutations affecting pseudoknot control of the replication of B group plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6476–6483. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6476-6483.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson I W, Praszkier J, Pittard A J. Molecular analysis of RNAI control of repB translation in IncB plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6497–6508. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6497-6508.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson I W, Siemering K R, Praszkier J, Pittard A J. Importance of structural differences between complementary RNA molecules to control of replication of an IncB plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:742–753. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.742-753.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J, Ganesan S, Sarsero J, Pittard A J. A genetic analysis of various functions of the TyrR protein of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1767–1776. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1767-1776.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zuker M, Jaeger J A, Turner D H. A comparison of optimal and suboptimal RNA secondary structures predicted by free energy minimization with structures determined by phylogenetic comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2707–2714. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.10.2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]