Abstract

Since school and business closures due to the evolving COVID-19 outbreak, urban parks have been a popular destination, offering spaces for daily fitness activities and an escape from the home environment. There is a need for evidence for parks and recreation departments and agencies to base decisions when adapting policies in response to the rapid change in demand and preferences during the pandemic. The application of social media data analytic techniques permits a qualitative and quantitative big-data approach to gain unobtrusive and prompt insights on how parks are valued. This study investigates how public values associated with NYC parks has shifted between pre- COVID (i.e., from March 2019 to February 2020) and post- COVID (i.e., from March 2020 to February 2021) through a social media microblogging platform –Twitter. A topic modeling technique for short text identified common traits of the changes in Twitter topics regarding impressions and values associated with the parks over two years. While the NYC lockdown resulted in much fewer social activities in parks, some parks continued to be valued for physical activity and nature contact during the pandemic. Concerns about people not keeping physical distance arose in parks where frequent human interactions and crowding seemed to cause a higher probability of the coronavirus transmission. This study demonstrates social media data could be used to capture park values and be specific per park. Results could inform park management during disruptions when use is altered and the needs of the public may be changing.

Keywords: Urban greenspaces, Social media, Big data, Topic modeling, Pandemic, Public values, GSDMM topic modeling

1. Introduction

Parks and greenspaces are essential assets to communities, conveyed through the aesthetic, recreational, ecological, economic, environmental, health, psychological, social, and cultural values that the public attaches to parks and greenspaces (Ives et al., 2017, Ordóñez et al., 2017, Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska et al., 2017). What people perceive and value about parks not only reveals the features and ecosystem services considered as important, but also indicates the cultural importance of parks in the society (Buchel and Frantzeskaki, 2015, Dickinson and Hobbs, 2017, Ordóñez et al., 2017). Understanding public values associated with parks could help prioritize services based on the interests and needs of the public (Ives & Kendal, 2014), which is crucial to evidence-based decision-making for parks and recreation, especially given funding and workforce constraints (Fulton, 2012).

Values associated with parks could be subject to environmental characteristics and social conditions as they often emerge from unique experiences in certain places (Brown et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2020, Dickinson and Hobbs, 2017, Hull et al., 1994, Ives et al., 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic when social distancing and home quarantine were recommended, the health and psychological benefits of urban parks became more salient as people were in need of being outside of home for mental rejuvenation, companion seeking, and physical activity (Addas and Maghrabi, 2022, Fagerholm et al., 2021, Heo et al., 2021, Khalilnezhad et al., 2021, Noszczyk et al., 2022, Reid et al., 2022, Spano et al., 2021, Ugolini et al., 2020). Although urban parks appear to be crucial to physical and mental wellbeing, decrease in usage or desire to visit was found to result from concerns about viral transmission, especially in places that tend to be crowded and at times when COVID cases were surging (Addas and Maghrabi, 2022, Fagerholm et al., 2021, Larson et al., 2022, Lopez et al., 2020, Pan et al., 2022). Understanding shifts in attitudes, opinions, and values associated with parks during this time could inform practices that address perceived risks as well as preferences regarding park usage, thus building people’s trust in park use to safely meet the public’s needs.

Yet, assessing values associated with parks can be challenging due to the limitations in data collection using surveys (Czepkiewicz, Jankowski, & Zwoliński, 2018), qualitative methods (e.g., interviews and focus groups) (Ordóñez et al., 2017) and participatory mapping (Brown et al., 2018, Jones et al., 2020), such as geographic and time constraints and costly and labor-intensive processes. During the pandemic, parks and recreation departments continue to face tight budgets including reduction in staff and services given the sharp drop in government tax revenue (Cohen et al., 2016, Fulton, 2012, Trust for Public Land, 2021). Under social distancing conditions, in-person surveys and direct observations are nearly impossible and potentially dangerous to park users and evaluators. Decision makers would benefit from a more cost and labor-effective approach to evaluate the shifts of perceptions, values and attitudes associated with park experiences during and post- outbreak.

Social media data can potentially complement traditional data collection for assessing opinions and values associated with urban parks (Grzyb et al., 2021, Heikinheimo et al., 2020; Pickering, Rossi, Hernando, & Barros, 2018). With emerging computational, web, and mobile technology, daily experiences and opinions toward places are shared frequently and in a large volume on social media platforms. These digital footprints, with geolocations and time stamps, on social media are considered data sources for opinion mining through the explicit semantics of the content, as social media platforms are virtual environments facilitating communication and knowledge exchange (Ishikawa, 2019). The qualitative content shared on social media platforms not only presents what users think is important, but also is influenced by other social media users as users tend to seek alignment with the common values on social platforms to receive attention from the others (Calcagni, Amorim Maia, Connolly, & Langemeyer, 2019). As a result, the values shared by the users are co-constructed in the collective interaction process (Calcagni et al., 2019). With this, social media data has the potential to uncover the values the public collectively assigns to a subject or a place (Roberts, Sadler, & Chapman, 2017).

Previous studies demonstrated user generated content from social media posts can be used to investigate the qualitative aspect of park use behavior beyond visitation patterns (Zhang, Huang, Zhang, & Buhalis, 2020). The specificity of information that can be elicited from qualitative content of social media depends on what and how the content is analyzed. Multiple studies have used images posted on photo-sharing social media platforms (e.g., Flickr and Instagram) to investigate parks and landscape experiences (Callau, Albert, Rota, & Giné, 2019; P. Chang and Olafsson, 2022, Conti and Lexhagen, 2020), preferred features (Pickering, Walden-Schreiner, Barros, & Rossi, 2020), and perceived ecosystem services (Alieva et al., 2021, Fox et al., 2021, Gosal and Ziv, 2020, Rossi et al., 2020, Yoshimura and Hiura, 2017). Although the approach can reveal certain places and features that are valued by visitors, photo-sharing social media is limited in further information about specific subjective values (Schrammeijer, van Zanten, & Verburg, 2021). Another approach is to draw information from the descriptive content of posts on social media platforms (i.e., text). Preferred features, activities, or trending topics regarding parks and greenspaces can be extracted simply based on frequently mentioned keywords or hashtags extracted from social media text content (Kim et al., 2018, Nenko, Kurilova, & Podkorytova, 2022, Palomino et al., 2016, Sim and Miller, 2019). However, keyword frequency analysis may fail to capture details and readable information as it does not account for the context in which the words are used. Several studies extracted value-related categories from hashtags within Instagram, as the hashtags are often used to express topics (Dai et al., 2019, Grzyb et al., 2021). Yet, hashtags provide limited descriptive content for opinion elicitation, such as attitudes and values (Palomino et al., 2016, Pilař et al., 2021).

Studies have further examined the collection of words from “text messages” in social media content to elicit semantics as this text allows for sentiments, preference, perceptions, and values elicitation (Wilkins et al., 2021), such as park experience (Sim & Miller, 2019), information search (e.g., seeking information about parks), emotion expression (Kovacs-Györi et al., 2018, Lim et al., 2018, Palomino et al., 2016, Plunz et al., 2019, Roberts et al., 2018, Roberts et al., 2019, Schwartz et al., 2019), judgement, complaints, and suggestions (Jianrong and Zhenbin, 2022, Teles da Mota and Pickering, 2021), and cultural ecosystem services (Dai et al., 2019, Johnson et al., 2019, Wan et al., 2021). Social media text content could provide insight expressed on the platforms into public reactions to park management decisions through demands for, or feedback toward, certain features in parks (Barry, 2014, Pickering and Norman, 2020, Soydaş Çakır and Levent, 2021).

The real-time and geotagging features of social media data enable investigation of changes in perceptions and values associated with urban parks over time (e.g., seasons) (Pickering et al., 2020) and across different parks (Rossi et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2021) based on the semantics extracted from the content of text data. A few studies have investigated changes in recreational ecosystem services provided by parks before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using social media data based on keywords or hashtags extracted from social media posts. Through a content analysis of Instagram hashtags about urban parks in Poland, Grzyb et al. (2021) discovered more forms of recreation and an increasing trend in nature and wilderness appreciation in urban greenspaces during the pandemic, compared to 2019. Niță et al. (2021) investigated recreational and social values delivered by parks during the pandemic. They used activity-related keywords highlighted in Instagram posts in urban parks in Bucharest, Romania. Two studies revealed the mental health benefits of urban parks during the pandemic based on sentiments/emotions expressed in posts from a microblogging platform, Sina Weibo (a.k.a., Chinese Twitter) (Cheng et al., 2021, Zhu and Xu, 2021).

Our literature review suggests two key research gaps to pursue. First, little research has explored the feasibility of eliciting public values associated with parks from social media data at scale using an unsupervised topic modeling approach. Second, we have not found a study that made use of the near-real-time and sematic aspects of social media data to investigate how and why the perceived importance of urban parks may shift over time.

This study aims to investigate how public values associated with urban parks have shifted between pre- COVID (from March 2019 to February 2020) and post- COVID (from March 2020 to February 2021) through Twitter -- a social media microblogging platform where large volume of texts are generated by the users to express thoughts about daily life, especially in urban areas (Hecht & Stephens, 2014). Text content of collected tweets was systematically analyzed using natural language processing and topic modeling techniques to address the objectives: (1) identify value topics from the park-related tweets pre- COVID and post-COVID using topic modeling; (2) examine differences in perceived values pre- and post- COVID; (3) examine attitudes toward the topics through sentiment analysis. We propose to adopt this time and cost-efficient approach to uncover the changes in dimensions of the perceived values and attitudes about specific parks with the location-based and near-real-time nature of social media data. The results showcase if social media data can be a sufficient data source to gain a broader understanding of the changes in park use behavior to inform park-specific management strategies moving forward.

2. Methods

2.1. Research setting

In this study, New York City (NYC) was selected as study region as NYC was the U.S. epicenter of the pandemic between April and July 2020 (Elliott and Akpan, 2020, Thompson et al., 2020). The city accounted for roughly 6 % of global cases by the end of March 2020 (NYC NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2021, World Health Organization, 2021). To suppress significant spikes in COVID-19 cases across neighborhoods, officials took urgent steps, including issuing social distancing and a stay-at-home order on March 22, 2020. The order barred non-essential gatherings and limited outdoor recreational activities to no-contact (e.g., solitary exercise) (New York State, 2020). During the early days of school and business closures in response to the evolving COVID-19 outbreak, parks and trails became popular destinations, offering spaces for fitness activities and an escape from home environments (Heinrich, 2020, Horton, 2020, National Recreation and Park Association, 2020, Wilson, 2020). NYC parks continue to experience a burst of use as people seek to maintain their social distance, but not be quarantined in homes (Lopez et al., 2020). Meanwhile, the city has faced public pressure to alter its policies and public statements almost daily in response to surging demand and preferences on park use during the pandemic (e.g., limiting entry to certain parks to reduce crowds, facility closure/reopening, program service changes, and closing streets to create open spaces for pedestrians and cyclists) (Bromwich et al., 2020; NYC Parks, 2021).

As tweet volume tends to bias toward parks with relatively higher visitation, Twitter data is less useful to investigate parks with low visitation (e.g., small neighborhood parks) (Brindley et al., 2019, Kovacs-Györi et al., 2018). We selected four flagship parks in each NYC borough as study areas, including Central Park in Manhattan, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, Flushing Meadows in Queens, and Bronx Park in Bronx (see Table 1 ). Staten Island was excluded because of comparatively low tweet count. Among the 40 parks in Staten Island that had tweets geotagged within their boundaries during both the year before (i.e., March 2019- Feb 2020) and the year after the pandemic started (i.e., March 2020-Feb 2021), the number of tweets geotagged in the parks were all less than 100 tweets per year. On average, there was less than one tweet per park per day, which would provide insufficient information for the analysis. The park selection for this study ensured that sufficient numbers of tweets were obtained, while collecting data to represent differences in park characteristics across NYC regions (Tenkanen et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the selected parks.

| Central Park | Prospect Park | Flushing Meadows | Bronx Park | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park acres | 840 acres | 526 acres | 898 acres | 718 acres |

| Sport fields | Baseball, basketball, soccer, tennis, volleyball, handball | Baseball, tennis | Baseball, basketball, volleyball, handball, golf, football, soccer, tennis | Baseball, basketball, soccer, handball, football, bocce |

| Spectator sports | None | None | New York METs, US Open Tennis | None |

| Recreational facilities | Playgrounds, outdoor pools, ice skating rinks, fitness equipment | Playgrounds, ice skating rinks, fitness equipment | Playgrounds, ice skating rinks, fitness equipment, indoor pools, skate parks, | Playgrounds, ice skating rinks, fitness equipment, skate parks |

| Greenways/trails | Bicycling greenways | Bicycling greenways, hiking trails | Bicycling greenways, hiking trails | Bicycling greenways, hiking trails |

| Amenities | Bathrooms, dog off-leash area, eateries | Bathrooms, eateries, barbecuing areas |

Bathrooms, barbecuing areas, kayak launch site | Bathrooms, barbecuing areas, eateries, kayak launch site |

| Dog friendly areas | Dog off-leash area | Dog off-leash area | Dog off-leash area | Dog off-leash area, dog run |

| Cultural institutions | Museum, historic houses | Museum, historic houses | Museum, World's Fair sites | None |

| Nature preserves | Zoo, botanical garden, nature centers | Zoo, botanical garden, nature Centers | Zoo, botanical garden | Zoo, botanical garden |

Note. This table demonstrates the different characteristics of the four study parks in terms of the recreation facilities and amenities available.

2.2. Data collection

Twitter data were download through Brandwatch®, a social media analytic platform that tracks daily conversations online and provides access to the full Twitter data stream via the Twitter Firehose data feed that guarantees delivery of 100 % of tweets since 2010 from Twitter API (Brandwatch, 2018). For each park, we obtained a dataset that consisted of the tweets containing the park name and the tweets geotagged in the park posted during two timeframes: (1) March 2019 – February 2020 (to represent pre-COVID), (2) March 2020 – February 2021 (to represent post-COVID) (see Table 2 ). Only posts from NYC users (i.e., who identified themselves as living in NYC in their Twitter profiles) were considered as we focused on resident’s perceived values about parks on a daily basis, in contrast with tourists who perceived smaller scales of values due to limited familiarity with the locations (Y. Chen et al., 2020). Park bounding boxes were used to identify and collect geotagged tweets. Then, a map layer of each park boundary was used to identify tweets geotagged in the park. Each tweet retrieved from the platform included detailed information about the tweet and user profile, including the ID, time stamp, text content, author handle, estimated user account types (individual or organization), and geolocation. In this study, we considered original tweets generated by individual accounts to capture opinions related to our study urban parks shared by Twitter users.

Table 2.

Overview of the Twitter dataset downloaded for this study.

| Dataset | Query | Pre COVID – Tweet count (users) |

Post COVID - Tweet count (users) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Park, Manhattan | Park-related tweets | Keywords: “central park” OR “centralpark*” | 167,827 (56,502) | 194,849 (66,355) |

| Geotagged tweets in the park | The park boundary with a 50-foot buffer | 55,531 (20,023) | 35,429 (8,326) | |

| Prospect Park, Brooklyn | Park-related tweets | Keywords: “prospect park”, “prospectpark*”, @prospect_park | 25,389 (8,239) | 32,277 (11,829) |

| Geotagged tweets in the park | The park boundary with a 50-foot buffer | 2,865 (1,363) | 2,704 (1,037) | |

| Flushing Meadows- corona Park, Queen | Park-related tweets | Keywords: “Flushing Meadows Corona Park”, “FlushingMeadowsCorona*”, “Flushing Meadows Park”, “FlushingMeadowspark*”, “Flushing Meadows-Corona Park”, @AllianceforFMCP | 2,225 (1,319) | 2,312 (1,367) |

| Geotagged tweets in the park | The park boundary with a 50-foot buffer | 13,369 (5,655) | 2,872 (9 9 7) | |

| Bronx Park, Bronx | Park-related tweets | Keywords:”bronx park”, “bronxpark*” | 906 (4 0 7) | 944 (5 1 6) |

| Geotagged tweets in the park | The park boundary with a 50-foot buffer | 2,766 (9 6 6) | 1,133 (4 8 2) |

Note. This table provides an overview of the number of tweets collected across the four study parks pre- and post- the COVID pandemic.

2.3. Data preprocessing

Data pre-processing using Natural Language processing techniques through the Python programming language involved two steps. Step 1 removed invalid tweets for topic detection. Tweets meeting the following criteria were classified as invalid for this study: (1) retweets, (2) non-individual accounts, (3) authentic, notable, and active accounts verified by Twitter, such as government, companies, news, entertainment, sports, and influential individuals, (4) tweets having fewer than three words, (5) tweets from users who have posted more than two identical messages, (6) tweets from users with unusually large tweet volumes, (7) tweets that contained the park name but were not referring to the park (e.g., a tweet pertaining to the subway station named “Prospect Park Station”, but not talking about Prospect Park). Step 2 cleaned the tweet contents and transformed the data for analysis. Tweet contents that interfere with the topic detection efficacy (including hyperlinks, hashtags, username mentions, emojis, numbers, and punctuations) were removed. N-grams were implemented to Identify-two-word terms (bi-grams), such as “Prospect Park” and three-word terms (tri-grams), such as “Grand Army Plaza”, that frequently occur in text of the tweets. Tokenization (to transform text into lists of words) and lemmatization (to transform the words to the base or dictionary form) were used to transform the text contents to lists of the base forms of words. Words that were not meaningful (stop words), extremely short (less than 3 characters), long (more than 15 characters), and extremely infrequent (occurring less than 3 times in all documents) were removed (Lansley and Longley, 2016, Yin and Wang, 2014). Fig. 1 demonstrates the step 1 and Fig. 2 shows the step 2 in the data processing procedure.

Fig. 1.

Data processing procedure. Note. This diagram shows the steps in data processing procedure, which consists of Step 1 (removed invalid tweets for topic detection) and Step 2 (cleaned the tweet contents and transformed the data for analysis).

Fig. 2.

Analysis procedure. Note. This graphic visualizes the steps in the analysis process. An example showcases how the value topics were inductively developed from the topics identified through topic modeling algorithm, followed by a thematic analysis to group the value topics into main themes.

After data preprocessing, in the Central Park dataset 71,792 tweets remained; in Prospect Park 13,267 tweets remained; in Flushing Meadows 5,608 tweets remained; and in Bronx Park 1,420 tweets remained (see Table 3 ). To address potential bias in the comparing pre- and post-COVID tweet counts, the 6 % increase in the overall number of NYC users was reflected in the percentage change in tweet count between pre-COVID and post-COVID with weighting, as suggested by Grzyb et al. (2021). The following equation describes the calculation.

| (1) |

Table 3.

Dataset sample size.

| Total | Pre-COVID tweet volume |

Post-COVID tweet volume |

Adjusted Post-COVID tweet volume1 | Adjusted % change2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Park | 71,792 | 31,763 | 40,029 | 37,628 | +18 % |

| Prospect Park | 13,267 | 4,443 | 8,824 | 8,295 | +87 % |

| Flushing Meadows | 5,608 | 4,280 | 1,328 | 1,249 | −71 % |

| Bronx Park | 1,420 | 822 | 598 | 563 | −32 % |

| Total | 91,927 | 41,148 | 50,779 | 47,733 | +16 % |

Note. This table demonstrates the sample size of the processed tweet dataset across the four study parks pre- and post- COVID and the weighted number of tweets generated post-COVID. It also shows the percentage change in the number of tweets between pre-COVID tweet volume and the adjusted post-COVID tweet volume.

The tweet volume is reduced by 6% to account for increase in the number of Twitter users between 2019 and 2020.

The values are calculated using Equation (1).

The year after the pandemic started there were more Twitter conversations posted by individual accounts about Central Park (+18 %) and Prospect Park (+93 %), than the prior year. In contrast, the tweet counts about Flushing Meadows (−71 %) and Bronx Park (−32 %) decreased after the pandemic began.

2.4. Data analysis

To automate the process of analyzing the text content of Twitter data, topic modeling was implemented. A topic modeling method for short text - Gibbs Sampling Dirichlet Multinomial Mixture algorithm (GSDMM) was used for mining topics from these tweets, since text content of tweets related to parks or geotagged in parks tends to be short. The average length of the tweets is around 5–6 words after data preprocessing (Yin & Wang, 2014). GSDMM works well for extremely short text that has sparse word co-occurrence as it simplifies the inference process by assuming one document is associated with one topic (Lossio-Ventura et al., 2021, Mohamed Ridhwan and Hargreaves, 2021). GSDMM hypothesizes each document could be based on a generative process, where the words or terms in the document are drawn from a probability distribution. A topic is represented by the probability distribution of the words/terms. Four parameters must be configured, including number of topics (K), α, β, and number of iterations. α stands for the probability that a document would be grouped in a cluster. β is the probability that the words in a document were similar to the words in other documents. The default values, α = 0.1, β = 0.1 suggested by Yin and Wang (2014) were used to identify topics from tweets in the park datasets. A fit procedure using different K values helped identify a suitable maximum number of topics in our dataset to best describe the data. With a maximum number of topics, the algorithm can automatically determine the clusters that maintain a good balance between completeness and homogeneity.

Finally, after the short text topic modeling method detected distinctive groups of tweets, manual annotation was used to relate each topic to a subject associated with parks. The topics identified by the algorithm were interpreted and assigned a theme using the “word intrusion” method (J. Chang, Gerrish, Wang, Boyd-Graber, & Blei, 2009). From the list of top 20 most relevant keywords associated with a topic generated by the algorithm, the keywords that made sense together were identified and used to form a theme while the keywords that were out of place or did not seem to be relevant to the meaning shared by the other keywords were excluded. A word cloud of the text content of associated tweets and sample tweets were used to confirm that the assigned theme represents the majority of the associated tweets. The groups that could not be semantically interpreted based on the keywords or that only consisted of fewer than 15 tweets were excluded.

Through a thematic analysis approach, we classified the topics (i.e., subthemes) into larger categories (i.e., main themes). The main theme categories were informed by a study that developed a structure of urban forest public values based on integrating data from various research where a list of public value clusters (e.g., economic, environmental regulations and life-support, health, natural/ecology, aesthetic, socio-cultural, and psychological values) and the descriptors were documented (Ordóñez et al., 2017). For example, the socio-cultural value cluster consists of multiple value descriptors, such as urban space, community, equity, cultural events, and recreation. For better interpretation, we classified topics identified in our model with the value descriptors in Ordóñez et al. (2017)’s model, instead of the main value domain. Table 4 shows a list of the value themes specifically related to the study parks, the definition, and associated examples were developed. The process was conducted by one researcher. However, the procedure was developed and confirmed by all authors. Two of the authors tested the procedure with one of the datasets to ensure validity, such as the process of interpreting topics and grouping themes.

Table 4.

Public values associated with the study parks, the definitions, and examples.

| Public value themes | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| General leisure activity | People spend time in parks to enjoy relaxation, food, and socialization through recreational activities. | Tweets referring to picnicking, enjoying food, walking dogs, spending time with family and friends were classified as the general leisure activity theme. |

| Physical activity | People participate in informal or organized physical activities in parks explicitly for exercise and fitness purposes. | Tweets referring to run/jogging, walk, workout, biking, ice skating. |

| Spectator sports | As facilities in parks are used for sports events, parks contribute to the spectator sports culture. | Tweets referring to spectator sports events, such as New York Mets, US Open Tennis. |

| Cultural events | Through hosting cultural events, parks provide opportunities for engagement with diverse culture. | Tweets referring to various cultural events, such as related to music, education, food, holidays, or diverse communities. |

| Cultural heritage | People value the historically important landscapes in parks. | Tweets related to historical landscape structure, buildings or exhibitions, such as monuments, museums. |

| Social norm | Parks play a key role in creating or shaping norms in the society. | Tweets referring to written and unwritten rules, beliefs, and attitudes that are considered acceptable in a particular social group or culture, such as racial/gender equity, social distancing practice during the COVID pandemic, anti-gun violence. |

| Urban space | Urban parks and nearby attractions and neighborhoods establish a sense of place that is associated with specific features of the environment. | Tweets referring to neighborhood charms and nearby attractions. |

| Transportation | The design and functionality of access to parks, such as bike lanes, trails and subway entrances, influences transportation in the urban setting, especially public transit. | Tweets referring to bike lanes, nearby subway stations, walkability, traffic nearby. |

| Park features | Parks are valued because of their functionalities, including facilities, amenities, and open spaces. | Tweets referring to maintenance of playground facilities, such as condition and trash issues. |

| Nature | People value various forms of connection to nature in park setting. | Tweets referring to nature appreciation, such as birding, fall scenery, and aesthetics related to nature elements. |

Note. This table shows a list of the value themes specifically related to the study parks, the definition, and associated examples developed for the analysis in this study.

To gain understanding of attitudes and feelings individuals expressed toward the topics, sentiment analysis was used to determine the emotional tone of the tweets associated with each topic. Sentiment analysis techniques use a text classifier to automatically assign text to a set of pre-defined categories based on its content, which then identifies whether the underlying sentiment is positive, negative or neutral (N. K. Singh, Tomar, & Sangaiah, 2020). In this study, a lexicon-based sentiment analysis tool - Valence Aware Dictionary and sentiment Reasoner (VADER), which aims for analysis of sentiments expressed on social media data, was used to assess sentiments of tweets in each topic (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014). VADER’s sentiment lexicon incorporates lexical features that are commonly used to express sentiments in microblogs, such as Western-style emoticon (Hutto, 2021). The polarity and intensity of sentiments are evaluated using the compound score, which normalizes the sum of the valence scores of each word in the lexicon to be between −1 to + 1. A compound score of −1 means the most extreme negative; whereas + 1 stands for most extreme positive. In this study, we used the default threshold values suggested in the literature to classify tweet sentiments with compound scores >= 0.05 as “positive” and one with compound score <= −0.05 as “negative”, with the remaining values are classified as “neutral”. (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014).

3. Results

From the pre- and post- COVID tweet datasets in each park, the GSDMM topic modeling technique identified topics and the associated keywords. The complete list of topics and related keywords for each period in park are provided in the Appendices. Each topic was related to a subject (i.e., subtheme) of specific characteristics about park use behavior and the park environments. Each sub-theme was then classified into a higher-level main theme associated with values of urban parks for semantical interpretation. The results for each park are summarized below. In general, the functionality of the parks revealed in the Twitter conversations are health benefits, socio-cultural benefits, and nature. Specifically, the values delivered by these parks can be understood through the following aspects: physical activity, general leisure activity, cultural events, cultural heritage, park features for recreational use, sports events, connecting to nature, transportation (e.g., bike lanes), urban space (e.g., urban parks and nearby attractions and neighborhoods establish a sense of place), and social norms (e.g., creating/shaping community culture). A sentiment analysis on the tweets associated with each theme was performed to demonstrate the attitudes toward each theme in each study park. Selected results of sentiment analysis were demonstrated to analyze the surge in tweet volume regarding some trending topics. The figures that illustrate results of sentiment analysis for each theme in each park are documented in the Appendices.

3.1. Central Park

From Central Park-related tweets, 20 subthemes were identified for the pre-COVID subset, and 27 subthemes were identified for the post-COVID subset. These subthemes were grouped into nine identical main themes associated with urban parks for both the pre- and post-COVID datasets, including general leisure activities, social norms, culture, physical activity, events, transportation, urban space, nature, and park features (Table 5 ). Experiences or opinions about physical activity (+194 %), nature (+253 %), and park features (225 %) were on average two times more popular in the year after the pandemic started than the year before. However, there was a decrease in tweets related to general leisure activities (−51 %), culture (−69 %), events (−100 %), transportation (−23 %), and urban space (−34 %). Note that there were changes in content specifically in the park feature theme. The Twitter conversation related to park features shifted from general park facilities and amenities maintenance to remarks about news, including part of Central Park open space being converted to an emergency field hospital and the Trump Organization no longer managing the two Central Park skating rinks. Furthermore, a new theme, social norms, emerged during the first few months after the pandemic started. Tweets about social norms in the park were mainly associated with the social distancing intervention that kept people 6 feet apart and required mask-wearing to prevent spread.

Table 5.

Main themes emerged from the Central Park related tweets.

| Main theme | Central Park |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID subtheme | %1 | Post-COVID subtheme | %2 | ±% | |

| General leisure activities | Leisure time activities (e.g., walk, picnic, dog, read), Spending time with family and friends | 54.31 % | Leisure time activities (e.g., walk, picnic, dog, music) | 26.89 % | −50.50 % |

| Social norms | None | 0 | COVID - Social distancing, anti-racism coversations3,the racial history of Central Park - Seneca Village, anti-LGBT conversations4 | 25.58 % | - |

| Culture | Metropolitan Museum of Art, Strawberry Field, Seneca Village, Women's Rights Pioneers Monument, Bethesda Terrace Fountain | 14.31 % | Metropolitan Museum of Art, Women's Rights Pioneers, Strawberry Field, Architect features by Frederick Law Olmsted | 4.43 % | −69.06 % |

| Physical activity | Run, marathon, walk | 5.56 % | Run, marathon, walk, bike | 16.33 % | +193.93 % |

| Events | Summer Stage Concerts, Global Citizen Festival, Making Strides Against Breast Cancer Walk | 4.45 % | None | 0 | −100.00 % |

| Transportation | Traffic | 4.20 % | Traffic | 3.25 % | –22.73 % |

| Urban space | Neighborhoods, nearby attractions | 3.62 % | Neighborhoods, nearby attractions | 2.39 % | –33.96 % |

| Nature | Birdwatching, Reservoir, Extreme weather events | 3.59 % | Birdwatching, Central Park Reservoir, Extreme weather events, Natural landscape, Central Park Zoo | 12.65 % | +252.72 % |

| Park features | Dog on-leash rule, Management of Wollman Rink and Lasker Rink | 1.77% | Field Hospital for COVID patients, management of Wollman Rink and Lasker Rink, boathouse, restaurant, sports fields | 5.76% | +225.45 % |

Note. This table demonstrates percentage changes in the percentages of tweet volume pre- and post-COVID across the identical main themes associated with Central Park, including general leisure activities, social norms, culture, physical activity, events, transportation, urban space, nature, and park features.

This is the percentage of the tweet volume pre-COVID (see Table 3).

This is the percentage of the tweet volume post-COVID (see Table 3). The tweet volume is reduced by 6% to account for increase in the number of Twitter users between 2019 and 2020.

The anti-racism conversations were triggered by a contentious incident between a white woman and an African American man in Central Park.

Opinions about Samaritan’s Purse, the Central Park emergency field hospital operator, making volunteers affirm an anti-same-sex marriage statement.

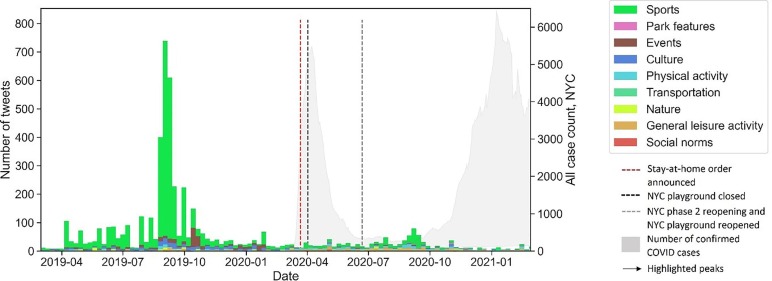

Fig. 3 displays weekly trends of the nine main themes from tweets about Central Park, March 2019 - February 2021. An increasing trend of Twitter conversations regarding Central Park occurred in March 2020 right after the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic and NYC issued a stay-at-home order. In general, the number of tweets about social norms, physical activity, and nature increased the few months after the pandemic started, which was then followed by a steady decline, except for the March and May 2020 peaks. The initial peak in the trend appears to align with the first surge of NYC confirmed cases. One peak occurred in March that seemed to associate with the increasing number of tweets about the park features theme, related to the emergency field hospital (Peak 1 in Fig. 3). While people held positive attitudes about Central Park providing physical space for the field hospital, negative sentiments expressed in the tweets reveal anxiety and concerns about the increasing number of patients and how the medical system was challenged by the outbreak (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Weekly trends of main themes for Central Park-related tweets. Note. This figure displays weekly trends of the nine main themes from tweets about Central Park from March 2019 to February 2021. Peak 1 in late March, Peak 2 in early April, and Peak 3 in May associated with the park features and social norms topics are highlighted.

During the pandemic, conversations about social norms in the park seemed to be tense due to complaints about people not practicing social distance or mask-wearing. On top of the mixed feeling about social distancing measures, there were two peaks in the social norm-related Tweets, due to two incidents. Unrelated to the Covid pandemic, the peak in early April could be explained with negative sentiment related to criticism of Samaritan's Purse asking volunteers to affirm an anti-same-sex marriage statement (Peak 2 in Fig. 3). An extreme peak from tweets in the social norm theme late in May 2020 was a highly publicized dispute between a white woman and a Black man and a video that went viral (Peak 3 in Fig. 3). These tweets mostly expressed negative attitudes as Twitter users criticized the woman’s racial discrimination toward the man (Fig. 4 ). The incident evoked Twitter posts about Central Park’s racial history, including the historic Seneca Village, a Black American enclave displaced by eminent domain during park construction.

Fig. 4.

Weekly trends of the sentiments for Central Park topics – park features and social norms. Note. This figure displays the weekly trends of the positive, negative, and neutral sentiments for the social norm and park feature topics associated with Central Park.

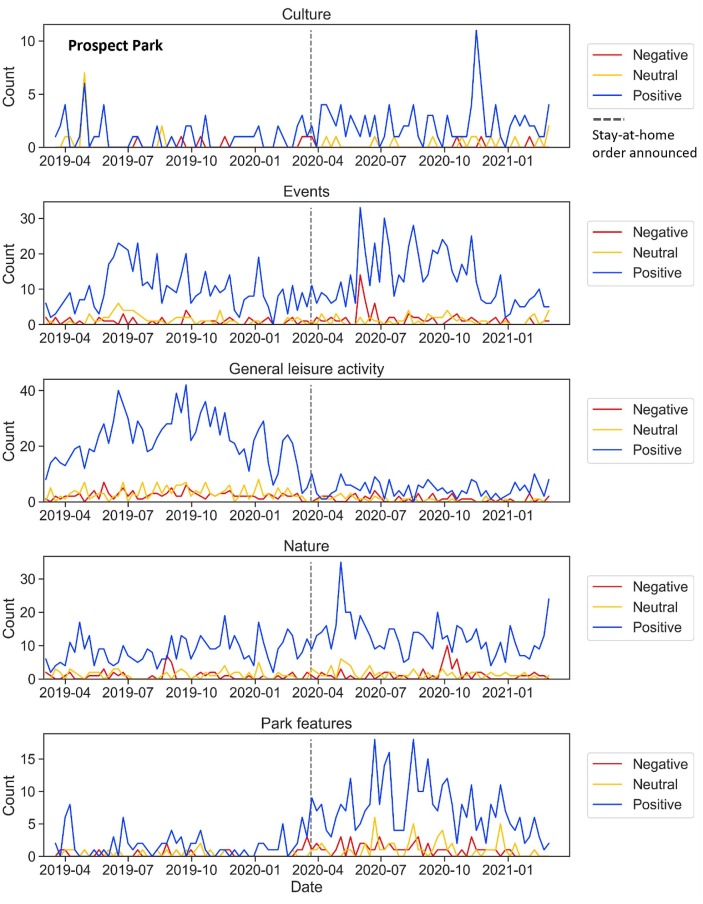

3.2. Prospect Park

The topic modeling identified 26 subthemes for pre-COVID and 20 post-COVID subthemes from the text content of the tweets related to Prospect Park. Like the Central Park results, these subthemes were grouped into nine main themes that described popular activities and common park experiences (Table 6 ). General leisure activity was the most popular topic in Prospect Park Twitter conversations the year before the pandemic. There was a significant increase in the number of tweets on physical activity (+62 %), park features (+134 %), and culture (+15 %) after the pandemic started, compared to the previous year. In contrast, the number of tweets about general leisure activities (−89 %) and events (−37 %) in the park, urban spaces (−66 %) and transportation (−92 %) around the park area decreased during the pandemic. Unexpectedly, the number of tweets that emphasize the value of nature has also declined (−29 %) in Prospect Park, mostly related to the decrease in conversations about Botanical Garden and the Zoo during the closure. Similar to Central Park, there is a new theme about social norms in Prospect Park during the virus outbreak, with a focus on whether and how people kept social distance from others in a park that was always crowded and the necessity of mask-wearing while participating in park activities.

Table 6.

Main themes from Prospect Park-related tweets.

| Main theme | Prospect Park |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID subtheme | %1 | Post-COVID subtheme | %2 | ±% | |

| General leisure activities | Leisure time activities (e.g., walk, picnic, dog, read, tour, break from work/school)photography, spending time with family and friends | 34.19 % | Leisure time activities (e.g., walk, picnic, dog, read), Birthday celebrations | 3.62 % | −89.43 % |

| Social norms | 0 % | COVID – wearing masks and social distancing, NYC mayor breaking the stay-at-home rule by traveling 11 miles to visit Prospect Park, cheering for Joe Biden winning the election, gun violence near the park, | 41.6 % | - | |

| Culture | Monuments | 1.35 % | The Endale Arch restoration, architectural features | 1.55 % | +14.97 % |

| Physical activity | Run, walk, biking, ice skating | 16.25 % | Run, walk, bike | 26.25 % | +61.51 % |

| Events | Celebrate Brooklyn, concerts, University Open Air, Smorgasburg food festival, holiday events | 14.31 % | Concerts and live shows, Family-friendly Black Lives Matter protests, a March to honor black and indigenous activists, | 8.98 % | −37.30 % |

| Transportation | Subway, bus, bike lane, walkability, traffic | 12.58 % | Subway | 0.97 % | −92.25 % |

| Urban space | Neighborhoods (e.g., Prospect Park South, Forte Greene) nearby attractions (e.g., Nitehawk cinema, restaurants, Greenwood Cemetery) | 3.76 % | Neighborhoods (e.g., Park Slope, Coney Island) | 1.27 % | −66.23 % |

| Nature | Birdwatching, natural landscape, Botanic garden, Prospect Park Zoo, Animals and plants (e.g., raccoon, algae issue) | 12.58 % | Natural landscape, birdwatching, Prospect Park Zoo | 8.88 % | −29.38 % |

| Park features | Maintenance of playground facility, Prospect Park Alliance, trash issue Management of facilities, | 2.36 % | Prospect Park Alliance, Complaints about off-leashed dogs, maintenance (e.g., trash issues) | 5.54 % | +134.49 % |

Note. This table demonstrates percentage changes in the percentages of tweet volume pre- and post-COVID across the identical main themes associated with Prospect Park, including general leisure activities, social norms, culture, physical activity, events, transportation, urban space, nature, and park features.

This is the percentage of the tweet volume pre-COVID (see Table 3).

This is the percentage of the tweet volume post-COVID (see Table 3). The tweet volume is reduced by 6% to account for increase in the number of Twitter users between 2019 and 2020.

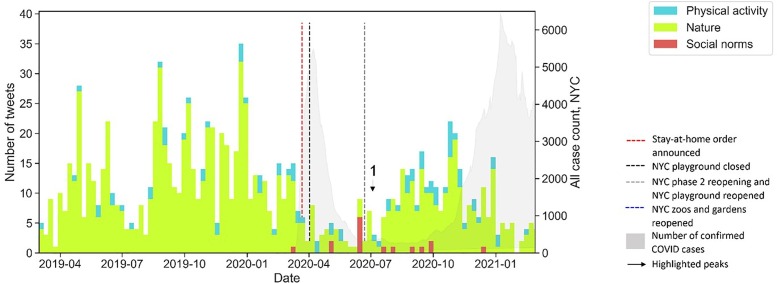

Fig. 5 shows that the change in the number of tweets about Prospect Park was associated with the first surge in confirmed cases in NYC and the announcement of the stay-at-home order. Although the number of tweets related to Prospect Park increased right after the pandemic started, it was followed by a steady decline in volume. The social norm theme mainly contributed to the increase of tweets the few months after the pandemic started. A weekly pattern of the tweet sentiments for the “social norms” theme between pre- and post- COVID (Fig. 5) demonstrates the tweet count peaked in March, May, and November. On March 22nd, the stay-at-home order aroused broad discussion about the crowds in Prospect Park and the outdoor market during the weekend (Peak 1). The Twitter conversation surge on May 4th was due to the NYC mayor’s non-essential travel to Prospect Park during the outbreak of coronavirus (Peak 2). The November 9th trending event on Twitter was the celebration of Biden winning U.S. presidency (Peak 3). Although positive sentiment dominated the conversations about social norms in Prospect Park, approximately 20 percent of the tweets expressed negative emotions, especially toward the topic of social distancing during the pandemic (Fig. 6 ). Twitter users were expressing their mixed feelings about social distancing while being in the park. For example, some showed their appreciation for the health benefit of outdoor open spaces during the difficult time. Yet, some worried about the safety of visiting parks amidst a burst of park use and while social distancing practices seemed to be questionable.

Fig. 5.

Weekly trends of main themes in tweets related to Prospect Park. Note. This figure displays weekly trends of the nine main themes from tweets about Prospect Park from March 2019 to February 2021. Peak 1 in March, Peak 2 in May, and Peak 3 in Nov related to the social norms topics are highlighted.

Fig. 6.

Weekly trends in sentiment for Prospect Park topics. Note. This figure displays the weekly trends of the positive, negative, and neutral sentiments for the social norm topic associated with Prospect Park.

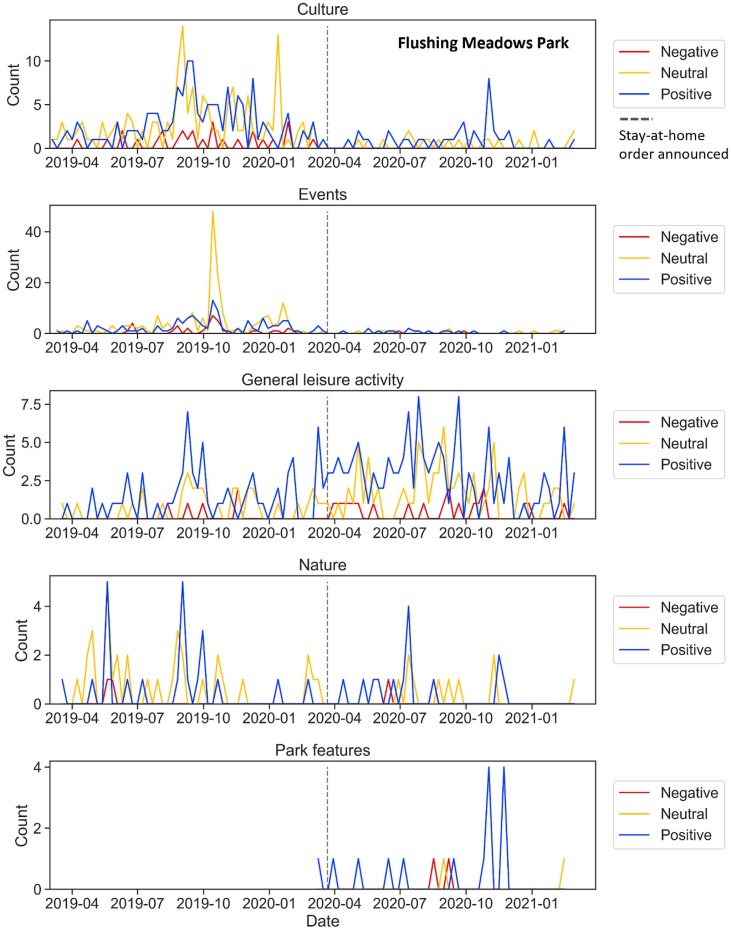

3.3. Flushing Meadows

From the Flushing Meadows tweets, 48 subthemes were identified for the pre-COVID subset and grouped into six main themes. For the post-COVID subset, 18 subthemes were identified and then grouped into nine main themes. As Flushing Meadows is famous for sports events (i.e., New York Mets and US Open Tennis) hosted in venues in the park, Twitter users’ posts were mainly about these sports events (see Table 7 and Fig. 7 ). During the year before the pandemic, tweets related to the sports events described viewing experiences for onsite sports games. During the pandemic year, spectators were not allowed to attend the games due to social distancing. Although there was a decrease in the number of the associated tweets (−56 %), some fans were still tweeting about how much they missed watching games onsite. Cultural events were also highlighted among the tweets related to Flushing Meadows. However, during the pandemic year, the number of Twitter conversations about the culture topic decreased (−35 %) as the indoor cultural heritage sites were closed to the public and events were canceled. During the pandemic year, the number of tweets about physical activity (+522 %) and general leisure activity (+695 %) increased at least sixfold. Despite very few conversations about nature, we observed an increase trend about nature appreciation (+47 %) in Flushing Meadows. There was also a new theme about social norms. The experiences and opinions were mainly related to COVID-19, such as keeping social distance, wearing a mask, and condolences over the death of a Hall of Fame pitcher from complications from dementia and COVID-19. The other newly emerging topics in the tweets are transportation and park features. For example, in the transportation theme people complained the park was becoming “a giant parking lot” and “highway ramp” and some advocated for a new greenway to increase access to the park and ensure pedestrian safety.

Table 7.

Main themes emerged from the Flushing Meadows related tweets.

| Main theme | Flushing Meadows |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID subtheme | %1 | Post-COVID subtheme | %2 | ±% | |

| Sports | New York Mets, US Open Tennis | 78.18 % | New York Mets, US Open Tennis | 34.34 % | −56.08 % |

| General leisure activity | Family and friends | 2.36 % | Photography, Drive-in movie theatre Family and friends |

18.75 % | +694.55 % |

| Social norm | None | 0 | COVID – mask-wearing and social distancing, | 1.43 % | - |

| Culture | World’s Fair, New York Hall of Science, New York State Pavilion Queens Museum | 7.55 % | World’s Fair, Fountain of the Fairs Restoration | 4.89 % | −35.14 % |

| Physical activity | Jogging, biking | 2.31 % | Run, walk, bike, marathon, workout | 14.38 % | +521.79 % |

| Events | Rolling Loud (concert), Hello Panda Festival, International Night Market, Making Strides Against Breast Cancer walk | 8.55 % | 2020 Evening of Fine Food | 2.86 % | −66.54 % |

| Transportation | None | 0 | Traffic issue in the park | 1.81 % | – |

| Nature | Queens Zoo, Willow Lake | 1.38 % | Queens Zoo | 2.03 % | 47.49 % |

| Park features | None | 0 | A community meeting about how to improve the park | 1.43 % | – |

Note. This table demonstrates percentage changes in the percentages of tweet volume pre- and post-COVID across the identical main themes associated with Flushing Meadows Park, including sports, general leisure activities, social norms, culture, physical activity, events, transportation, nature, and park features.

This is the percentage of the tweet volume pre-COVID (see Table 3).

This is the percentage of the tweet volume post-COVID (see Table 3). The tweet volume is reduced by 6% to account for increase in the number of Twitter users between 2019 and 2020.

Fig. 7.

Weekly trends of main themes in tweets related to Flushing Meadows. Note. This figure displays weekly trends of the nine main themes from tweets about Flushing Meadows from March 2019 to February 2021.

3.4. Bronx Park

From Bronx Park-related tweets, 10 subthemes were identified for the pre-COVID subset and grouped into two main themes. For the post-COVID subset, 9 subthemes were identified and then grouped into three main themes. The topics emerging from Bronx Park tweets were different from the other three parks in both quantity and content. As Table 8 shows, the topics were mainly about activities related to nature, including visiting Bronx Zoo and Botanical Garden. Though not broadly discussed, physical activity, such as jogging and walking, was another theme. In general, while the number of tweets related to the nature theme has decreased 34 %, there was a 117 % increase in conversations about physical activity from pre-COVID to post-COVID. The social norm theme emerging during post-COVID was solely about a shooting incident in Bronx Park. Fig. 8 illustrates the weekly pattern of tweet counts for the themes, revealing the trend change pre- and post- COVID. Before the pandemic, there were more Twitter conversations about the zoo and the botanical garden with peaks when there were events (e.g., the Botanical Garden Holiday Train Show in and Bronx Zoo Holiday Lights). Right after the pandemic began, the tweet volume dropped because the garden and zoo were closed. An increasing trend in the nature theme arose after the zoo and garden were reopened in July 2020. While the tweet counts about daily physical activity grew gradually over the year, a sudden increase in Twitter conversations about social norms was due to the tragic 6/15/2020 shooting inside Bronx Park.

Table 8.

Main themes emerged from the Bronx Park related tweets.

| Main theme | Bronx Park |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID subtheme | %1 | Post-COVID subtheme | %2 | ±% | |

| Nature | Bronx Zoo, Botanical Garden | 79.2 % | Bronx Zoo, Botanical Garden | 52.34 % | −33.91 % |

| Physical activity | Jogging | 4.01 % | walk | 8.7 % | +116.60 % |

| Social norms | None | 0 | Gun violence in the park | 4.85 % | - |

Note. This table demonstrates percentage changes in the percentages of tweet volume pre- and post-COVID across the identical main themes associated with Bronx Park, including social norms, physical activity, and nature.

This is the percentage of the tweet volume pre-COVID (see Table 3).

This is the percentage of the tweet volume post-COVID (see Table 3). The tweet volume is reduced by 6% to account for increase in the number of Twitter users between 2019 and 2020.

Fig. 8.

Weekly trends of main themes in tweets related to Bronx Park. Note. This figure displays weekly trends of the three main themes from tweets about Bronx Park from March 2019 to February 2021. One peak in June related to a social norm topic is highlighted.

4. Discussion

This study examined public values regarding park experiences and impressions on Twitter related to four NYC parks during the year before the pandemic (03/2019–02/2020) and the first year after the pandemic was announced (03/2020–02/2021). Although previous studies have elicited values of urban parks through descriptive content of social media data, many used images, keywords, or hashtags from the context that limit capture of user sentiments (Dai et al., 2019, Johnson et al., 2019, Wan et al., 2021). We found only one study that discovered whether the “messages” from microblogging platforms, such as Twitter, can be a sufficient source for assessing public values related to parks (Johnson et al., 2019). Through natural language processing and unsupervised topic modeling techniques, the present study showcased what public values can be inferred from the opinionative content of tweets at scale. The real-time Twitter data related to the four parks were collected throughout the two-year period enabling the investigation of temporal patterns of topical tweet volume (i.e., yearly and weekly) and how these patterns vary across parks (see Fig. 9 ).

Fig. 9.

Changes in value topics associated with the 4 parks during the pandemic year, compared to the previous year. Note. This figure displays the changes in percentage of tweets associated with each value topic between the year before and the year after the COVID pandemic. The yellow tone color scheme stands for an increase, the blue tone color scheme refers to a decrease, and color white means the value topics are not detected from the tweets. “*” indicates it is a new theme.

This study evidenced a broad collection of public values associated with urban parks can be captured through topic mining Twitter data. The value themes identified confirm findings from multiple studies using social media data that investigated values of urban greenspace. Our study evidences Twitter posts highlight urban parks as a place for recreation, physical activity, socializing with friends and families, cultural diversity (e.g., events), valuing cultural heritage (e.g., historical landmarks), forming a sense of place (e.g., attachment to urban spaces), appreciating aesthetic landscapes (e.g., fall scenery), and nature (Dai et al., 2019, Johnson et al., 2019, Wan et al., 2021). Particularly, social media data provides rich information about salient events as they serve as public spaces for social activities (e.g., the Black Lives Matters protest in Prospect Park), encountering cultural differences (e.g., confrontation between a Black birdwatcher and a white jogger in Central Park), and shaping community culture (e.g., the social distancing norm across parks and anti-gun violence in Bronx Park) (Collins & Stadler, 2020; Sim & Miller, 2019). The differences in value themes identified across the four parks, each located in different boroughs in NYC, indicates social media data is effective at capturing the “park-specific” characteristic of public values, which implies not only the distinct functions these urban parks serve but also how park use is subject to neighborhood social and physical environments (Wang et al., 2021). For example, while Central Park and Prospect Park were seen as important destination parks with quality greenspaces and facilities offering a variety of recreational activity opportunities, Flushing Meadows was known for the sports events and cultural heritage from the World’s Fair in 1939 and 1964 and Bronx Park invoked the impression of nature in the Bronx Zoo and Botanical Garden.

Our findings demonstrate the time-sensitivity of social media posts about public spaces during challenging and unprecedented times. As expected, values associated with urban parks after March 2020 are reflecting the experiences and opinions regarding the global public crisis. The new theme regarding “the social distancing norm” (Collignon, 2021) emerging from Twitter conversations indicated how the pandemic has influenced park use, such as topics about wearing masks, social distancing, and the stay at home order (Grzyb et al., 2021, Niță et al., 2021). Interestingly, this change varied across study parks. A significant increase in Twitter messages about social distancing concentrated in Prospect Park and Central Park where crowds have continued being a concern for park use safety. This is consistent with one previous study investigating perception of urban green spaces in NYC that found concerns about crowded conditions in parks were higher in Brooklyn and Manhattan compared to Queens and Bronx (Lopez et al., 2020).

In the meantime, there were increasing trends in the topics related to physical activity (walking, jogging, and biking) and nature (seasonal changes, zoo, and gardens), especially in Central Park and Flushing Meadows while the NYC lockdown resulted in event cancellations, limited travel, and far fewer programs and activities in parks and surrounding neighborhoods. Aligned with findings from recent studies using survey methods that examined perceived values of urban parks during the pandemic (Grima et al., 2020, Lopez et al., 2020, Venter et al., 2020), our results indicate urban parks may play an even more important role in serving recreational, health, and environmental benefits to the residents during the COVID pandemic when non-essential activities have to be cancelled (Kleinschroth & Kowarik, 2020). For instance, urban parks in NYC were considered more important for mental and physical health during the early COVID-19 pandemic months (Lopez et al., 2020). Exercise and connecting to nature were the main reasons for the users’ increasing visits to the urban and peri-urban natural areas in Burlington, Vermont (Grima et al., 2020). That said, the trend of increased conversations about nature did not hold true for all study parks. Tweets about nature in Prospect Park and Bronx Park appeared to be dominated by topics related to the botanic gardens and zoos. The significant decrease in these messages likely resulted from the closure of these locations during the pandemic. The result indicates that perceived functionality may change, and the direction could vary across parks due to their distinctive functionality and how it was affected by the pandemic shutdowns.

Another novelty of our analytic approach was investigating the tones of the tweets associated with each value theme based on the Twitter “messages.” This could not have been achieved simply by examining keywords or hashtags in social media posts (Grzyb et al., 2021, Niță et al., 2021). The application of sentiment analysis on Twitter messages associated with specific value topics provide a systematic way to further examine the nuances of the tweets for each theme. For example, when speaking of parks during the pandemic, topics related to social distancing can be related to various feelings. The positive attitudes expressed in tweets related to topics about the health benefits of activities in parks evidenced the importance of parks to quality of life during the lockdown. On the other hand, the negative attitudes are mostly about crowds in parks that violated social distance practices and confusion about how to keep social distancing when at parks. Although practicing precautionary actions could help prevent the spread of the virus, people were experiencing complexities in following the new social norm due to risk underestimation and perceived barriers to social distancing (K. Chen et al., 2020, Ciancio et al., 2020).

Despite the effectiveness of capturing values associated with parks from Twitter data, this approach is not without limitations given the nature of this “found“ data source (i.e., data that is not collected for specific research purposes). First, the results could be biased toward certain topics (e.g., cultural values) due to social media users’ tendency to focus on extraordinary events in their daily lives, eye-catching subjects, and that people are more likely to post on social media under the influence of extreme positive emotions (Schoenmüller et al., 2019, Sim and Miller, 2019, Yuan et al., 2019). The results from the analysis may underrepresent the values related to chronic environmental issues (e.g., air pollution, water quality, and protection of water basins), economy (e.g., land value and energy savings), and positive aspects of parks that are expected, normed, or inherited in park experiences (e.g., playgrounds). These latter positive aspects were highlighted as key public values about parks in the findings from a study through traditional methods (Ordóñez et al., 2017). Likewise, a study that compared tweet and interview data on cultural ecosystem services highlighted concerns about eliciting values using Twitter as less likely to capture spiritual values, inspiration, education, and knowledge systems (Johnson et al., 2019).

Second, causality between the impact of the COVID pandemic and the change in park-related topics cannot be inferred because the short text of tweets lacks contextual information (Roberts et al., 2019). We believe the values were influenced by COIVD because of the date of capture, but we did not specifically search for tweets that mentioned values and COVID in same 280 characters. Third, due to the 280-character limit, Twitter content is restricted in detail. For example, it is unlikely to elicit preference, ranking, or prioritization from Twitter data, such as the degree of satisfaction or significance (Johnson et al., 2019). Additionally, Twitter conversations could hardly represent opinions and experiences of the general population because the Twitter user sample tends to bias toward middle age (i.e., 35–65 years old), male, highly educated, and wealthier populations (Wojcik & Hughes, 2019). Thus, the findings might not describe park experiences of young children and older adults. That said, the main value of social media data is to complement existing data sources (e.g., surveys and interviews) to help gain a broader understanding of park experiences (both in terms of the number of people included and across time). The automated process we applied makes the value topic elicitation generalizable and applicable to study parks across geographic regions. The rapid and timely information from social media data could signal on-going issues or newly emerged activities in parks that would be challenging to obtain through traditional methods.

There are methodological considerations for future studies to efficiently apply this approach in understanding changes in values related to public spaces. First, to ensure sufficient volume of data for analysis, this approach is more suitable for parks having high visitation in which people tend to share their experiences on social media, such as flagship parks in highly dense urban areas (Donahue et al., 2018, Sim and Miller, 2019). For example, we found that out of 2,022 parks in NYC, only 44 larger parks were mentioned in more than 100 tweets pre-COVID (March 2019 – February 2020). There were very few Twitter messages about the other parks that tend to be small or have limited recreation resources. In parks having low visitation rates, very low or no tweets posted make the extrapolation of user behavior and preferences to smaller parks difficult. Second, as Twitter data are noisy (e.g., containing emojis, hashtags or hyperlinks) and inconsistent (e.g., different terms are used to describe one subject), well-developed data preprocessing techniques are a key to successful topic models (T. Singh & Kumari, 2016). Third, even though the unsupervised topic modeling algorithm automatically identified topics, the results require human annotators with expertise in park use to define what these topics entail. This process is critical because it allows the researcher to incorporate domain-specific knowledge to topic interpretation, which relates the data science-derived findings to the practice of park management and planning. Fourth, gaining insights on the details about each theme requires further manual annotation. As the topic modeling technique forms topics based on the relationships among words in tweets, we noticed the value topics identified in this study tend to be less fine-grained than topics extracted by human coding in previous studies. For example, one of the value themes, “general leisure activity,” consists of tweets related to socialization with friends/families in parks, walking dogs, and picnics because these words are more likely to coexist.

From the managerial perspective, our findings pinpoint an opportunity for practitioners’ use of public opinion data from social media to inform their actions in a cost-effective way. In times of public crisis, there is a strong need for evidence to support decision making that responds to the abrupt changes in perceptions and use of urban parks (Eykelbosh & Chow, 2022). When social distancing becomes the new norm, design and use of parks and greenspaces has to be reimagined to remain essential for health and wellbeing (Abusaada and Elshater, 2020, Herman and Drozda, 2021). The sensitivity of social media data about public spaces in terms of time, place, and content indicates the potential for evaluating urban parks for management purposes, especially for large flagship parks that are more likely to be mentioned on social media. For example, the increasing number of Tweets voicing the need for more greenspace for outdoor physical activity and relaxation would serve as evidence to support short term action to create more greenspaces, such as establishing an Open Streets or Play Street programs, allowing access to informal greenspaces, and integrating greenways into transportation corridors that links green open spaces for recreation means of transport (Kleinschroth & Kowarik, 2020). In addition, practitioners can benefit from using this approach for future intervention evaluations, such as evaluating NYC Open Streets -- a program that has expanded during COVID by opening streets to play, diners, and activity, and closed the streets to automotive traffic (Hipp, Bird, van Bakergem, & Yarnall, 2017).

As social media data has been broadly applied to real-time surveillance (e.g., disaster management, healthcare (Gupta & Katarya, 2020)), it is worth exploring whether this approach can be applied to inform park management in a timely manner. Our findings suggest Twitter data could potentially be a valid data source for practitioners to monitor public opinions about up-to-date park experiences, signal events or issues, and propose strategies that address the issues specific in large flagship parks in real-time. For example, the confusion expressed on Twitter about social distancing in Prospect Park right after the execution of the stay-at-home order indicates the need for proper timing for park managers’ immediate actions. This may include effective communication that persuades people to conduct social distancing, provide clear signs and guidelines to enable precautionary actions in parks, and have more staff to patrol in parks to maintain order and respond to immediate needs of users. Park management would benefit from a real-time model that monitors attitudes and perceptions of parks through social media data if COVID-19 or other transmittable disease threatens public health. However, more work would be needed as real-time surveillance requires a system to continue streaming social media data, extracting information from posts, and reporting in near real-time. The major challenge for managers could be that this type of analysis would require technology capacity to collect, process, and analyzes the data as well as report findings. Collaborations between researchers and practitioners would be necessary to facilitate the use of research evidence from social media analysis.

5. Conclusion

As Twitter is a popular social media platform for expressing thoughts and exchanging ideas and experiences, tweets reveal public perception of urban parks. Through a short text topic modeling technique, we identified a variety of topics that demonstrate public values related to four NYC parks during the year before and following the pandemic. While we found an increasing trend in the Twitter conversations specifically about physical activity, nature, and park features, and the new social norm theme – social distancing, the topics evolving the year before and after the pandemic show unique features specific to the characteristics of the four flagships NYC parks. The changes in opinions and values associated with urban parks pre- and post- COVID indicate the essential role parks have played during the COVID pandemic when usage has increased, and the needs of the public may be changing. This study demonstrates that specific values of each park can be captured through public opinions expressed on social media in a rapid, cost-effective way and at scale, which can complement existing data sources and help extend our understanding of park use (Ceron & Negri, 2016). For future research, this longitudinal approach could be particularly suitable for natural experiments or purposeful interventions that examine public values about the change in the design or management of open spaces.

Code Availability.

All Python code written for this paper is available: https://github.com/jhhuangGeo/STTM-Tweets-UGs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This study is part of the project “Greenspace Characteristics and their Associations with Population Health” founded by USDA Forest Service. Grant/Agreement Number: 16-JV-11330144-065.

Appendix

Appendix A.

Topics emerging from the Central Park dataset - Pre-COVID.

| Themes | Topic # | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| General leisure activity | 237 | Love, walk, city, look, morning, friend, see, photo, people, place, enjoy |

| 299 | Life, thank, love, people, friend, walk, look, meet, talk, woman, feel | |

| 201 | Love, friend, photo, music, video, birthday, weekend, meet, family | |

| 83 | House, game, chess, skate, checker, holiday, ceremony, love, winter | |

| Culture | 157 | Art, metropolitan, meet, camp, fashion, love, exhibit, museum, exhibition, play it loud (an exhibition in Metropolitan Museum) |

| 40 | Walk, museum, place, city, visit, meet, tour, food, street, ride, pizza | |

| 74 | Strawberry Field, imagine, John Lennon, people, world, live, life, peace, dreamer, memorial, hope | |

| 286 | Woman, statue, monument, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, design, city, commission, history, sculpture, pioneer, Women’s Suffrage | |

| 269 | Seneca Village, history, community, land, build, monument, city, tour, black community, village, African American | |

| 144 | Fountain, Bethesda Terrace, angel, terrace, love, Bethesda Fountain, tile, ceiling, arcade, John Wick | |

| Physical activity | 103 | Run, mile, morning, marathon, race, finish, runner, training, finish line, half marathon |

| Transportation | 273 | Street, car, ride, horse, bike, cyclist, city, pedestrian, drive, bus, carriage, driver, traffic |

| Urban space | 101 | View, building, street, apartment, tower, build, look, floor, city, block, live, space |

| Events | 142 | Concert, ticket, summer, tonight, perform, rock, Global Citizen Festival, Summer Stage, Taylor swift |

| 254 | Walk, support, join, cancer, thank, team, help, donate, health, cause, family, breast cancer, awareness, society | |

| Nature | 241 | Bird, see, squirrel, duck, look, pond, Central Park Zoo, hawk, snow, warbler, ramble, spot, reservoir, pigeon |

| 298 | Reservoir, Onassis Reservoir, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, morning, spring, duck, hunt, sunrise, view | |

| 279 | Record, break, temperature, temp, hit, number, weather, tonight, wind, station, breaking, winter, thermometer | |

| Park features | 186 | Dog, coyote, sighting, plastic, rat, spot, leash, feed, squirrel, bench, need, prospect |

| 31 | Trump, remove, ice, ice rink, skate, skating rink, Trump Organization, Wollman Rink, business, ice skating, company, city, fix |

Appendix B.

Topics emerging from the Central Park dataset - Post-COVID.

| Themes | Topic # | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | 259 | walk, run, mile, ride |

| General leisure activity | 74 | Love, photo, walk, thank, look, life, feel, city, friend |

| 292 | Thank, see, watch, love, concert | |

| 271 | Picnic, drink, wine, eat, cake, chocolate, cup, food, recipe, pizza, cheese | |

| 125 | Happy Valentine’s Day | |

| Social norm | 287 | Dog, woman, police, Amy Cooper, man, black man, video, Central Park Karen, leash, racism |

| 49 | Mask, wear, social distancing, crowd | |

| 249 | Seneca Village, community, history, land | |

| 83 | Volunteer, hospital, field hospital, support, tent hospital, statement, faith, agenda, Franklin Graham, worker | |

| 142 | Franklin Templeton, racism, tolerate | |

| Nature | 187 | Bird, owl, snowy owl, squirrel, rat, duck, barred owl, hawk, tree, coyote |

| 240 | Bird, warbler, sparrow, reservoir, ramble, goose, lake, great blue heron, duck, pond, north woods | |

| 265 | Fall, tree, color, spring, autumn, leaf, flower, bloom, season, foliage, garden, winter | |

| 176 | Snow, inch, fall, record, storm, winter, temperature, snowfall, wind, weather, rain, snowstorm, forecast, blizzard | |

| 274 | Central Park Zoo, zoo, penguin, animal, lion, aquarium | |

| 272 | Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, reservoir, sunset, run, walk | |

| Park features | 109 | hospital, field hospital, tent, bed, Javits Center, patient, emergency, covid, Javitz Center, nursing home, comfort |

| 191 | trump, Central Park Carousel, Ice rink, ice skating rink, organization, contract, city, rink, course, golf, skating rink, Wollman Rink | |

| 174 | boathouse, restaurant | |

| 134 | Central Park Tennis, court, tennis center, center, tennis court, basketball | |

| Transportation | 203 | horse, ride, bike, carriage, street, run, car, Central Park Loop, cyclist, pedestrian, lane, path, drive |

| Culture | 155 | art, Metropolitan Museum, museum |

| 62 | statue, woman, Susan B. Anthony, monument, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, unveil, pioneer, Sojourner Truth, sculpture, honor, bronze, Christopher Columbus, Meredith Bergmann, history, suffragist | |

| 11 | John Lennon, imagine, Strawberry Field, peace | |

| 70 | Frederick Law Olmsted, landscape, Calvert Vaux, architect, statue, architecture, design | |

| 47 | celebrate, anniversary, pictorialist, century | |

| Urban space | 120 | street, view, upper east side, Central Park East, west, apartment, tower, upper west side, building, block, Empire State Building |

Appendix C.

Topics emerging from the Prospect Park dataset- Pre-COVID.

| Themes | Topic # | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| General leisure activity | 86 | walk, love, run, friend, thank, dog, people, fall, morning, know, look, life, see, yesterday, weekend, feel, work, summer, live, tree |

| 217 | thank, family, night, love, session, play, tonight, bring, boathouse, picnic, walk, photo, life, say, share, tree, yoga, party | |

| 267 | dog, owner, home, wear, run, hunt, lover, work, ice, cream, leash, cut, version, load, save, steal, pay, tax, morning, tell | |

| Physical activity | 358 | run, morning, race, mile, walk, start, game, week, tonight, marathon, think, break, loop, look, end, half marathon, snow, tomorrow, finish |

| 246 | lakeside, Lefrak Center, roller, skate, love, rink, photo, set, event, look, ice, summer, concert, party, photography, tonight, dreamland | |

| 239 | ride, horse, bike, jog, end, case, photo, style, buy, remember, location, say, hawk, limit, jingle, bell, town | |

| 291 | fitness, run, level, challenge, king, health, man, warrior, welcome, age, brother, exceed, wealth, making, think | |

| Nature | 273 | see, lake, spot, bird, think, morning, Varied Thrush, look, sparrow, walk, duck, winter, tree, know, watch, lot, warbler, life, enjoy, rain |

| 278 | warbler, singe, path, pool, place, Flycatcher, oak, drive, singing, quaker, cemetery, ball, cycle, fly, Throated, meadow, mourning | |

| 97 | zoo, animal, work, help, visit, fish, exhibit, goat, miss, meet, otter, stop, member, touch, bird, daughter, squirrel, wildlife, summer | |

| 318 | zoo, panda, baby, cub, fountain, debut, monkey, bailey, thank, era, blast, guy, display, loop, rain, moment, baboon, pair, song | |

| 128 | algae, dog, bloom, pond, turtle, kill, water, lake, think, grow, tackle, pet, hand, meadow, neighborhood, owner, discover, technology | |

| 262 | zoo, watch, buy, lion, sea, baboon, sleep, tonight, convert, fox, vigil, bear, food, soho, prayer, turtle, release | |

| Transportation | 199 | Bike lane, tree, car, drive, people, parking, think, street, path, stop, lot, lane, bike, see, use, ocean, entrance, block, ave, city |

| 16 | train, run, bus, minute, ave, bind, tell, station, wait, shuttle, Coney Island, leave, platform, B train, switch, stop, signal, problem, service | |

| Urban space | 120 | garden, tour, food, walk, area, Park Slope, neighborhood, sunset, rock, Coney Island, view, zoo, sun, museum, bridge |

| Park features | 314 | people, city, family, Prospect Park Alliance, group, community, dollar, board, fund, need, member, mayor, engage, organization |

| 15 | Splash pad, try, earth, spring, tomorrow, event, join, mother, sign, vale, product, bring, clothe, celebration, change, circle, love, beauty | |

| 46 | playground, harmony, fix, bathroom, potty, picnic house, sand, break, use, crew, wire, porta, deal, road, glass, water fountain | |