Abstract

Background

The global pandemic has caused breast cancer (BC) patients who are receiving chemotherapy to face more challenges in taking care of themselves than usual. A novel nurse-led mHealth program (mChemotherapy) is designed to foster self-management for this population. The aim of the pilot study is to determine the feasibility, usability, and acceptability of an mChemotherapy program for breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. The objective also is to evaluate the preliminary effects of this program on adherence to app usage, self-efficacy, quality of life, symptom burden, and healthcare utilization among this group of patients.

Methods

This is a single-blinded randomized controlled pilot study that includes one intervention group (mChemotherapy group) and one control group (routine care group). Ninety-four breast cancer patients who commence chemotherapy in a university-affiliated hospital will be recruited. Based on the Individual and Family Self-management Theory, this 6-week mChemotherapy program, which includes a combination of self-regulation activities and nurse-led support, will be provided. Data collection will be conducted at baseline, week 3 (T1), and week 6 (T2). A general linear model will be utilized for identifying the between-group, within-group, and interaction effects. Qualitative content analysis will be adopted to analyze, extract, and categorize the interview transcripts.

Discussions

Breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy are a population that often experiences a heavy symptom burden. During the pandemic, they have had difficulties in self-managing the side effects of chemotherapy due to the lack of face-to-face professional support. An mChemotherapy program will be adopted through a self-regulation process and with the provision of nurse-led real-time professional support for these patients. If proven effective, BC patients who engage in this program will be more likely to take an active role in managing their symptoms, take responsibility for their own health, and subsequently improve their self-efficacy and adherence to the use of the app.

Keywords: adjuvant chemotherapy, breast cancer, health care, management, toxicity

Introduction

Globally, a total of 16.7 million patients were diagnosed with breast cancer (BC) from 1990 to 2017, with an estimated 2.3 million new BC cases in 2020.1,2 In China, there were an estimated 2.5 million BC patients by the end of 2021. 3 Chemotherapy has been widely recognized as a systemic treatment for invasive BC; however, it has numerous side effects.3,4 The majority of patients who undergo chemotherapy are treated in outpatient clinics and have to manage their symptoms themselves at home. 5 The Chinese Ministry of Health has been making great efforts to encourage hospitals to deliver a transitional care program for patients who have been discharged from hospital. 6 A previous transitional care program provided nursing home visits to support symptom management for this group of patients. 7 During the current COVID-19 pandemic, no face-to-face transitional care can be delivered, therefore, the patients are receiving no support during the interim period, leading to an increase in unplanned hospital admissions.

Promoting self-management of the side effects of chemotherapy may thus become a priority for these patients during the transitional period. With the outbreak of the pandemic, mobile health (mHealth) has become a major mode of delivery for many self-management programs. mHealth is described as the utilization of mobile apps to promote health-related behaviors and deliver timely and tailored healthcare for improving health-related outcomes. 8 Throughout the recent decades, mHealth self-management programs have been rapidly gaining popularity for delivering different kinds of transitional care, such as health education, consultations, alerts, referrals, treatment reminders, and the personal monitoring of cancer patients to facilitate the process of self-management for BC patients undergoing chemotherapy. 9 Previous mHealth-based studies tended to focus on different self-management goals for these patients, such as symptom management,10-12 physical activity, 13 psychological support, 14 and treatment compliance.11,12,15

No matter what kind of service they deliver and what kinds of goals they focus on, the common issue is that patients may not adhere to the app usage as intended. Adherence to mHealth applications is referred to“the degree to which the user followed the program as it was designed.” 16 Earlier mHealth self-management programs reported that adherence to the use of the app could decline during the course of chemotherapy. One study led by Handa found that adherence to the use of the app decreased after the first cycle of chemotherapy (week 3), and further decreased by 25.5% by the end of the intervention (week 12). 17 Many participants felt that it was not necessary to report their symptoms because they understood how and when each symptom might occur and that it would be resolved by the second cycle of chemotherapy. 17 One trial, which involved the development of a mobile app that provided a self-monitoring function to BC patients receiving chemotherapy, exhibited a sharp decrease (50%) in compliance rate one month after the commencement of the program. 18 Several studies have stated that cancer patients usually find it difficult to self-assess and self-manage their symptoms at home due to insufficient professional support.19,20 A study led by Zhu indicated that symptom burden might be a barrier to app usage among female BC outpatients receiving chemotherapy. 21 Although adherence has been identified as a crucial factor in self-management by cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, 20 evidence of how to improve adherence to the use of mHealth apps and how to promote self-management among this population remains sparse.

Conceptual Framework

The Individual and Family Self-management Theory (IFSMT) 22 will guide the development of the present program. This theory posits that people are more likely to participate in self-management behaviors if: “(1) they are equipped with self-regulation skills to perform self-management behaviors; (2) they receive social facilitation that positively supports them in engaging in an intended behavior; and (3) they have confidence in carrying out the recommended behavior”. 22 The present mHealth self-management program is intended to increase the self-regulation skills and activities of BC patients who are undergoing chemotherapy, provide them with professional support, and enhance their self-efficacy.

Earlier evidence indicated that cancer patients could improve adherence through self-regulation activities. 23 Self-regulation activities are the process utilized to change health-related behaviors. They include activities such as goal setting, self-monitoring, reflective thinking, decision making, planning and action, self-evaluation, and the management of responses associated with changes in health behavior. 22 Integrating the 6 components of self-regulation activities into a mobile application (mChemotherapy) is aimed at promoting self-monitoring behaviors and the self-management of symptoms. Professional support given by nurses is another factor that may facilitate adherence to the app by users. BC specialist nurses will support the self-management behaviors of BC patients by socially facilitating the process of self-regulation. During the self-regulation process, nurses will play a pivotal role in providing and negotiating most healthcare services, including symptom tracking, case management, remote health education, and medical referrals, while patients are empowered to engage in self-regulation activities. Patients with higher levels of self-efficacy might then become more engaged in changing their health behaviors with greater adherence to self-management, leading to better symptom control and quality of life (QoL).24,25 If patients recognize that they are able to increase their self-regulation activities and alleviate the severity of their symptoms, they will become more confident about doing so and continue to adhere to the self-management apps.

To date, little is known about whether the nurse-led mHealth self-management program could significantly improve adherence to app usage among BC patients receiving chemotherapy compared with a control group. This pilot study endeavors to foster the self-management of symptoms through the process of self-regulation and real-time professional support from nurses. If proven successful, these patients will become more prone to actively engage in managing their symptoms, taking responsibility for their own health, and subsequently improving their self-efficacy and adherence to the use of the app.

Objectives

The objectives of the pilot study are: (1) to examine the enrollment rate, eligibility rate, retention rate, and dropout rate in a nurse-led mHealth self-management program; (2) to determine the usability of a nurse-led mHealth self-management app; (3) to test the preliminary effectiveness of this program on adherence to the use of the app, self-efficacy, QoL, symptom distress, symptom frequency, and healthcare utilization; and (4) to identify the perceptions and acceptability of the program for BC patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Methods

Study Design and Study Setting

The study protocol has received ethical approval from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University in China. The present study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05192525). The pilot study follows the SPIRIT statement for the Standard Protocol of Clinical Trials.26,27 This is a single blinded randomized controlled, parallel-group pilot study. The trial will be conducted at a chemotherapy day clinic of the Breast Health Centre of Ruijin Hospital in Shanghai, China.

Eligibility Criteria

Patients will be eligible if they (i) are aged 18 or above, (ii) have been newly diagnosed with BC; (iii) have commenced chemotherapy and been prescribed at least 4 cycles of a chemotherapy regimen; (iv) own a mobile phone and a personal WeChat account; (v) have Wi-Fi at home; and (vi) are able to read and write Chinese. Patients will be excluded if they (i) are pregnant; (ii) have been diagnosed with terminal-stage BC (i.e., stage IV); (iii) have previously received chemotherapy; (iv) have been prescribed with targeted therapy or radiotherapy; (v) have documented mental disorders; and (vi) have already engaged in other mHealth studies.

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated with the effect size (.38) of primary endpoint self-efficacy reported in a prior similar mHealth app-based trial. 28 Assuming an alpha level of .05 and power of 80%, a sample of 220 is needed. Since the primary purpose of the pilot study is to examine the feasibility of the program, it is recommended to decrease the sample size of the full-scale study by 65%. 29 Previous mHealth app-based trials showed an attrition rate of 10%∼20%.30,31 Eventually, 94 (47 per arm) subjects were required for this pilot trial when the drop-out rate was set at 20%.

Recruitment

Ninety-four BC patients who are undergoing the first 2 cycles of chemotherapy will be invited to participate in the study. The recruiters include 2 research assistants who will be responsible for subject recruitment and data collection. There will be 5 steps in the recruitment process. (1) Training will be conducted for the recruiters to understand the recruitment process; (2) BC patients who are scheduled to receive chemotherapy will receive recruitment messages; (3) The recruiters will screen eligible participants following the inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) The eligible participants will be given a consent form to sign before enrolling in the study. The consent form will introduce the aims of the study, the intervention and treatment, security and privacy, and the benefits and potential risks of taking part in the study. (5) Eligible participants will sign the consent form; meanwhile, the recruiters will provide them with a telephone hotline number for them to call if they have questions to which they would like to have answers.

Randomization and Masking

Randomization will be carried out at a ratio of 1:1 by the computer software “the Randomizer”. The study will include one intervention group (group A) and one control group (group B). The odd numbers will be assigned to group A, and the even numbers to group B.

A nurse who will not be involved in the intervention will conduct the randomization procedure via the computer. The results of the group random assignments will be shown only to the intervention nurses in the mChemotherapy platform. The 2 research assistants responsible for subject recruitment and data collection will not be in charge of the group allocations and intervention. The nurses responsible for the control group, who will provide the routine care, will not be involved in the intervention or in carrying out the process of screening and making group allocations.

Interventions

mChemotherapy

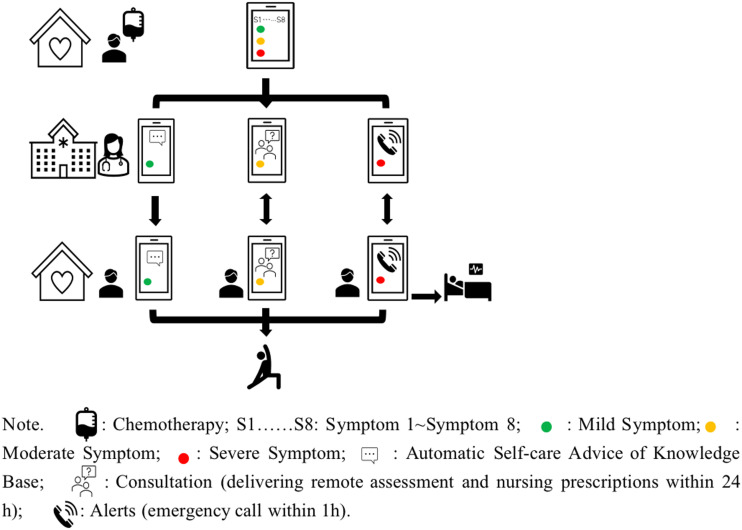

The nurse-led mHealth self-management program (mChemotherapy) is composed of one core intervention “mChemotherapy” (see Figure 1), one pre-chemotherapy consultation, and 2 planned follow-up visits. mChemotherapy will be specifically utilized to facilitate symptom self-management for BC patients who are undergoing chemotherapy. The interventions will be conducted following the self-regulation process (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Pilot drawings of mChemotherapy program.

Table 1.

Interventions Following the Self-Regulation Process.

| Self-regulation process | Interventions |

|---|---|

| 1 Goal setting | Setting goals (week 0, Pre-chemotherapy) |

| 2 Self-monitoring and reflective thinking | Self-monitoring weekly or when patients feel unwell (weeks 1∼3, weeks 4∼6) |

| 3 Decision making | Initiating consultations with nurses (weeks 1∼3, weeks 4∼6) |

| 4 Planning and action | Planning and performing actions following nursing prescriptions (weeks 1∼3, weeks 4∼6) |

| 5 Self-evaluation | Feedback on whether or not the nursing prescriptions were completed (week 3, week 6) |

| 6 Management of responses | Revising goals (week 3, week 6) |

Pre-Chemotherapy Consultation

Through the Official WeChat platform, the patients in both groups (the intervention and control groups) will be informed about the chemotherapy regimen and the self-management of chemotherapy-related symptoms during the pre-chemotherapy visit. In addition, a tailored goal-setting and self-management plan for intervention group will be made based on the pre-chemotherapy assessment conducted by a nurse.

Intervention Group

The intervention group will take part in an mChemotherapy program for 6 weeks. The mChemotherapy is built on the official WeChat platform of the Ruijin Hospital Breast Centre and includes 6 components: (1) self-monitoring, (2) consultation, (3) alerts, (4) reminders, (5) my prescriptions, and (6) knowledge base. Intervention group participants will be given an individual username and password to log into the mChemotherapy platform. The intervention nurses will deliver the intervention and contact patients through this platform. To ensure that the content of these protocols is appropriate to BC patients and nurses, the protocols have been discussed and reviewed by members of the research and service teams before the commencement of the study.

(1) Self-monitoring The self-monitoring module is utilized by BC patients to report symptoms weekly after they have received each cycle of chemotherapy or whenever they feel unwell. Participants can indicate the level of severity of their symptoms as either mild (level 1), moderate (level 2), or severe (level 3) from a list of eight symptoms, namely, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, fever/febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, constipation, oral mucositis, and insomnia.4,32-35 In addition, patients will be able to report their blood test results if they have undergone a blood routine examination in a clinic.

(2) Consultation The consultation module allows patients to ask nurses questions about their symptoms. For those with moderate (level 2) symptoms, the nurses will provide a reassessment questionnaire, tailored feedback to patients on their questions, as well as non-pharmacological self-management advice within 24 hours. If the BC patient is reassessed with severe symptoms, the nurses will be able to immediately provide him/her with a referral to an outpatient department.

(3) Alerts The alert module includes 2 functions: emergency calls and referrals. A built-in alert parameter is set based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). If a patient reports severe symptoms, an alert will be immediately sent to nurses. An emergency call link will be sent to the patient so that the patient can immediately be connected to a nurse. Nurses are required to initiate the emergency call and arrange for a referral to an emergency department within one hour, if necessary.

(4) Reminder The reminder module is set for weekly self-monitoring. The 2 automatic reminder messages for weekly self-monitoring will be set at 7:00 AM and 7:00 PM.

(5) My prescriptions There are three levels of nursing prescriptions. For those with mild symptoms, nursing advice on self-management, such as about engaging in physical activity, will automatically be sent to patients. For those with moderate symptoms, non-pharmacological nursing advice such as about the use of cryotherapy for mucositis will be delivered to patients within 24 hours. For those with severe symptoms, nurses will make a referral to an emergency department within 1 hour. Patients can review the previous nursing prescriptions by clicking the module “My prescription”.

(6) Knowledge base In the knowledge base module, articles or videos on symptom self-management will be updated every two weeks for BC patients receiving chemotherapy. Patients can also search articles or videos in the knowledge base through keywords.

Follow-Up

Two scheduled visits will be provided to each member of the intervention group on week 3 and week 6 of the chemotherapy regimen. During each visit, the intervention nurses will review the comprehensive reports generated from the mChemotherapy platform and provide a tailored self-management scheme via nursing prescriptions.

Control group (Sham app)

Routine care will be provided during the pre-chemotherapy consultation and in the 2 follow-up visits to the patients in the control group. A routine care app has been developed for the control group, composed of three functions: “consultation, knowledge base, and reminders for treatment” (see Table 2). The control group of patients will receive 2 scheduled telephone calls from nurses. Patients will be given a phone number to consult the nurses when they have questions related to their symptoms or concerns related to the regimen. Patients in the control group will not be able to access the “mChemotherapy” program until they have completed the pilot study.

Table 2.

Comparison of Protocols Between the Two Groups

| Protocols | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-chemotherapy consultation | ✔ | ✔ |

| Self-monitoring | ✔ | × |

| Alerts | ✔ | × |

| Reminders | ✔ | ✔ |

| Consultation | ✔ | ✔ |

| My prescription | ✔ | × |

| Knowledge base | ✔ | ✔ |

| Follow-up | ✔ | ✔ |

| Frequency | Reminders: weekly; Knowledge base: update every two weeks | Reminder: once before each cycle of chemotherapy; Knowledge base: update once monthly |

| Delivery channel | Pre-chemotherapy consultation: Official WeChat platform; Consultation: app; Follow-up: app | Pre-chemotherapy consultation: Official WeChat platform; Consultation: telephone; Follow-up: telephone |

| Intervention content | Knowledge base: Self-management of chemotherapy-induced symptoms | Knowledge base: Knowledge about breast cancer and chemotherapy |

| Duration | 6 weeks | 6 weeks |

Intervention Fidelity

To ensure that each participant receives the same intervention dose, the length, number, and frequency of the follow-up visits will be guided based on a protocol. An e-manual of practice protocols will be used to guide the providers to deliver individualized information and care for both groups. An eight-hour training workshop will be conducted, held over 2 sessions in the format of lectures and small group discussions. Following this, the pilot study will be commenced to train the providers to deliver individualized care to BC patients. To assure that the intervention nurses understand the content, an online written test will be provided after the training. The nurses will need to receive a score of above 80% before they can provide care in this program.

Primary Endpoint and Secondary Endpoint

The primary endpoints of this study are feasibility outcomes, adherence to the usage of the app, the perceived usability of the app and self-efficacy.

Feasibility Outcomes

Feasibility outcomes include: (i) the time spent on participant recruitment; (ii) the eligibility rate of the screened patients; (iii) the recruitment rate; (iv) the retention rate; and (v) the dropout rate.

Adherence to Usage of the App

Data on an individual’s 6 weeks of usage, including log-in frequency and duration of usage, are tracked in the WeChat statistics module of the background thread. Log-in frequency is recorded as the number of times that a participant logged into the app for 6 weeks. The total duration of usage is recorded as the sum of all times in minutes between logging in and logging out.

Perceived Usability of the App

The acceptability and usability of the app will be evaluated using a self-reported questionnaire, the System Usability Scale (SUS), 36 after the completion of the study (week 6). The SUS is an instrument for determining the users’ perception of the usability of the mobile app from their response to 10 items. Scores range from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate better usability, with 68 indicating average usability. 36

Self-efficacy

Strategies Used by People to Promote Health (SUPPH) is a health promotion strategy questionnaire, which has been developed to evaluate the confidence of cancer patients in self-managing their disease. 37 The original scale has 29 items and uses a 5-point Likert scale, from 1, indicating no confidence, to 5, indicating extreme confidence. High scores indicate a high level of self-efficacy. The Chinese version of the SUPPH was adapted by Qian and Yuan, and the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale is .970, indicating high reliability. 38

The secondary endpoints of this study include quality of life, symptom burden, healthcare utilization, usability of the app, and patients’ experiences with the study.

Quality of Life

General quality of life has been used as a measurement to reflect the outcome of the treatment. 39 The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) is selected since it is a health-related QoL instrument specific to BC patients. It is divided into 5 subscales, namely, physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, and additional concerns. 40 Higher scores indicate a better QOL. Wan et al reported that the internal consistency of most domains in the simplified Chinese version of FACT-B ranged from .82 to .85. 41

Symptom Burden

The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form (MSAS-SF) is an instrument that can be used to measure the symptoms of distress of BC patients. 42 This questionnaire is composed of three dimensions: the Physical Symptom dimension (PHYS), the Psychological Symptom dimension (PSYCH), and a Global Distress Index (GDI). 42 It includes 28 items on distress and frequency in the physical symptom dimension and 4 items in the psychological symptom dimension during the past week. 42 Higher scores indicate more frequent distress, distress of greater severity, and higher levels of distress. The simplified Chinese version of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form (MSAS-SF-SC) has been found to be reliable, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subscales ranging from .782 to .874. 43

Healthcare Utilization

Chemotherapy-induced healthcare utilization for 6 weeks will be recorded in the pilot study for analysis. Three types of healthcare utilization will be collected: patient-initiated hotline calls, unplanned visits to the ambulatory clinic, and unscheduled visits to the emergency department. These records will be obtained from the statistics center of the study hospital.

Usability of the App

In the current study, the usability of mChemotherapy will be tested using the narrative review, which is a user-feedback form of evaluation. Two separate meetings will be held before commencing the intervention: one focusing on patient testers and the other focusing on provider testers. Each meeting will last for approximately 30-45 minutes and will be held by a researcher and software engineer who are familiar with usability testing. The protocol of talk- or think-aloud will be used in the testing. It is widely utilized to determine the usability of mHealth applications. 44

Patients’ Experiences With the Study

Open-ended questions were designed based on the conceptual framework (i.e., knowledge and beliefs, self-regulation skills and abilities, and social facilitation) to guide the semi-structured interviews. The interviews will be conducted in an interview room at the chemotherapy clinic to ensure privacy for the participants. A purposive sampling method will be adopted to recruit participants until data saturation is reached.

Sociodemographic Data

The sociodemographic data and clinical data of the subjects will be collected through a questionnaire for a baseline assessment. The demographic data include gender, age, marital status, education, economic status, and current employment. The clinical data will be retrieved from the electronic medical records of the hospital, and will include cancer stage, type of surgery, chemotherapy received (pre-/post-operatively), type of chemotherapy, and comorbidity.

Data Collection

Demographic data will be collected during the pre-chemotherapy consultation (week 0). The feasibility outcomes and SUS will be collected after the study is completed (week 6). SUPPH, FACT-B, and MSAS-SF will be collected at week 3 and at the end of the study at week 6 using self-reported questionnaires. The logged data of the participants in the intervention group are collected during their use of the mChemotherapy. The data collectors will be blinded to the group allocations and intervention.

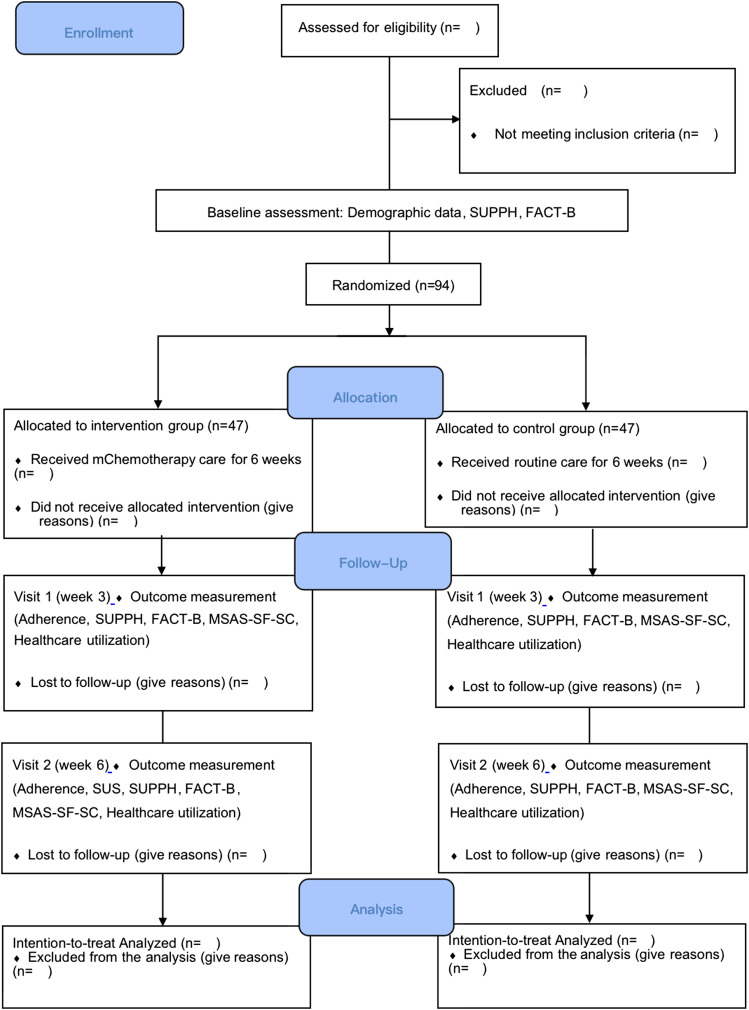

Data Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis approach will be used for the analyses of the pilot trial (see Figure 2). Data cleaning will first be performed before commencing the data analysis. Descriptive and inferential analyses will primarily be utilized in the pilot trial. The sociodemographic data and the clinical data at baseline of both groups will be compared using an independent samples t-test for continuous variables and a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Missing continuous variables will be imputed using a Markov chain Monte Carlo method, while missing dichotomous or categorical variables will be imputed using a fully conditional specification model. 45 A general linear model will be utilized for the between-group, within-group, and interaction effects among the three time-points. For healthcare utilization, descriptive statistics will be used to analyze the mChemotherapy logged data. A Mann-Whitney U test will be used to compare the total value of the frequency for each type of healthcare utilization between the 2 groups. Statistical analyses will be performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 with a significance level of P < .05 for a two-tailed test.

Figure 2.

CONSOR Flow Diagram for the Pilot Study.

All interviews will be performed in Mandarin Chinese and recorded by a note taker. A qualitative analysis software (NVivo 12.0) will be used to analyze the data from the imported transcripts. First, the interview records will be imported into the data analysis software. The interviews will be read by the researcher several times, to obtain an overall sense of the content as a whole. Second, the text of the transcripts will be sorted into several content themes based on the conceptual framework (i.e., knowledge and beliefs, self-regulation skills and abilities, and social facilitation) as well as on the perception of the feasibility of the pilot study. Third, in accordance with each content theme, the meaning units will be extracted and then condensed. Fourth, a code will be labeled and abstracted from the condensed meaning units. Last, various codes will be sorted into sub-categories after comparing differences and similarities. During the data analysis process, a research assistant will be invited as the independent researcher to conduct a reliability check and engage in an ongoing discussion with the doctoral student and one study participant.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee (HSESC) of the The Hong Kong Polytechnic University on 20 September 2021 (HSEARS20210816002). All patients who are deemed to be eligible after screening will be invited to take part in the pilot study. They will have the autonomy to decide whether or not they are willing to participate in the study. They will also have the freedom to drop out at any time or at any stage during the process, without giving a reason or incurring any penalties. The patients will be assured that their withdrawal or refusal to participate will not influence their receipt of routine care. They will be informed of the aims and significance of the pilot study, and will be provided with an explanation of the process and treatment, incentives, security and privacy, as well as the benefits and potential risks of engaging in the study. All users will be given a username and password specifically for the use of mChemotherapy. The outcomes of the pilot study will only be used for publication, with no personal information revealed. The names of all of the participants will be replaced with codes to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. The data that are collected will only be available to the research team. The digital data will be stored in locked and secure computers. No data will be saved on personally owned mobile devices or computers.

Discussion

BC patients undergoing chemotherapy are people who often endure multiple symptoms. Without regular support from healthcare professionals, these patients may experience a high symptom burden and a low QoL. The closure of clinics and the fear of infection during the COVID-19 pandemic could exacerbate the situation. It is thus imperative to develop a new method for fostering self-management behaviors among BC patients who are receiving chemotherapy.

This pilot study has some strengths. To the best of our knowledge, little is known about whether adherence to the use of an mHealth app can be increased through a process of self-regulation and social support. The current study will capture the phase of the first 2 cycles of chemotherapy to observe the behavioral strategies of patients with regard to how they respond to professional support and establish self-management routines. This algorithm-based mChemotherapy program can provide timely interactions and tailored management to BC patients. The entire process of self-regulation will be guided by nurses, who will be endeavoring to foster behavioral changes in self-management on the part of the patients. Patients can be supervised by nurses and helped to set goals and follow the self-management protocols. Patients can feel reassured when they engage in timely interactions with nurses. 7 If the program proves to be effective, patients who receive the real-time and tailored nurse-led support will be more likely to become responsible for managing their symptoms, contributing to an improvement in self-efficacy and adherence to app usage. Second, there are limited guidelines on nursing practices relating to the self-management of chemotherapy-induced symptoms for cancer patients. Our study has contributed by developing several nursing protocols for symptom self-management by cancer patients. Lastly, this pilot study will contribute evidence on the feasibility, usability, acceptability, and effectiveness of a nurse-led mHealth-based symptom program for supporting self-management by this group of patients. Such knowledge may be of help in conducting a full-scale mHealth self-management program for BC patients who are undergoing chemotherapy.

Although this is a well-structured study, some limitations are anticipated. First, there is a chance that the participants in the intervention and control groups might communicate while waiting in the clinics. Therefore, both groups will receive the intervention and follow-up in their own home settings. Second, several BC patients will go to the nearest hospital instead of to the study hospital where their referral has been scheduled, which may affect the data collection procedure and the sample size of the study. Accordingly, patients will be required to enter details of their use of hospital services in a logbook. Third, some participants may not adhere to self-monitoring behaviors due to forgetfulness and time pressures. 46 Tailored reminders will be used to improve their adherence to self-monitoring. 47 Patients who are working full time will receive reminders during their spare time.

In conclusion, it is important to adopt a novel nurse-led mHealth self-management program for supporting the self-management of BC patients receiving chemotherapy during the pandemic. The aim in this pilot study is to foster self-management in bringing about changes in behavior, and subsequently to improve self-efficacy and adherence to app usage for this group of patients. If effective, this model can be sustained in the current research setting and can also be introduced to other cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, especially those in unsupervised settings.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks Qingyun Zhan, Junxian Chen, and Shuai Li who were responsible for developing the app.

Appendix.

Abbreviations

- BC

Breast Cancer

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- FACT-B

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast

- GDI

Global Distress Index

- HSESC

Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee

- IFSMT

Individual and Family Self-management Theory

- mHealth

mobile health

- MSAS-SF

Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form

- PHYS

Physical Symptom dimension

- MSAS-SF-SC

Chinese version of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form

- PSYCH

Psychological Symptom dimension

- QoL

Quality of Life

- SUPPH

Strategies Used by People to Promote Health SUS, System Usability Scale

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Arkers Kwan Ching Wong, Prof. Frances Kam Yuet Wong, and Nuo Shi contributed to the conceptualization and development of the protocol. All the authors participated in the design of the app development. Nuo Shi wrote the original draft. Dr Arkers Kwan Ching Wong and Prof. Frances Kam Yuet Wong critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project was supported by thesis funding for the pursuit of the degree of Doctor of Health Science, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Ethics statement: The study protocol has received ethical approval from the The Hong Kong Polytechnic University in China (HSEARS20210816002).

Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT05192525.

ORCID iD

References

- 1.Li N, Deng Y, Zhou L, et al. Global burden of breast cancer and attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2017: results from the global burden of disease study 2017. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0828-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, et al. Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):e279-e289. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Partridge AH, Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Side effects of chemotherapy and combined chemohormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2001;2001(30):135-142. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck SL, Eaton LH, Echeverria C, Mooney KH. SymptomCare@Home: Developing an integrated symptom monitoring and management system for outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Comput Inform Nurs. 2017;35(10):520-529. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health . National nursing career development plan (2016-2020). Chin Nurs Manag. 2017;17(1):1-5. doi: CNKI:SUN:GLHL.0.2017-01-007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai XB, Ching SSY, Wong FKY, et al. A nurse-led care program for breast cancer patients in a chemotherapy day center: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(1):20-34. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) . mHealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies: Based on the Findings of the Second Global Survey on eHealth (Global Observatory for eHealth Series, Volume 3). World Health Organization; 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241564250_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi N, Wong AK, Wong FK, Sha L. Mobile health application-based interventions for improving self-efficacy among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A systematic review. JMIR Preprints. 2021. (in press). doi: 10.2196/preprints.35986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fjell M, Langius-Eklöf A, Nilsson M, Wengström Y, Sundberg K. Reduced symptom burden with the support of an interactive app during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer - A randomized controlled trial. Breast. 2020;51:85-93. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graetz I, McKillop CN, Stepanski E, et al. Use of a web-based app to improve breast cancer symptom management and adherence for aromatase inhibitors: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(4):431-440. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0682-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HJ, Kim SM, Shin H, et al. A mobile game for patients with breast cancer for chemotherapy self-management and quality-of-life improvement: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10):e273. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egbring M, Far E, Roos M, et al. A mobile app to stabilize daily functional activity of breast cancer patients in collaboration with the physician: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(9):e238. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Ebert L, Liu X, Wei D, Chan SW. Mobile breast cancer e-support program for chinese women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy (Part 2): Multicenter randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(4):e104. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paladino AJ, Anderson JN, Krukowski RA, et al. THRIVE study protocol: A randomized controlled trial evaluating a web-based app and tailored messages to improve adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):977. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4588-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, et al. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e52. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handa S, Okuyama H, Yamamoto H, Nakamura S, Kato Y. Effectiveness of a smartphone application as a support tool for patients undergoing breast cancer chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20(3):201-208. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Min YH, Lee JW, Shin YW, et al. Daily collection of self-reporting sleep disturbance data via a smartphone app in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e135. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SH, Kim K, Mayer DK. Self-management intervention for adult cancer survivors after treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(6):719-728. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.719-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magalhães B, Fernandes C, Lima L, Martinez-Galiano JM, Santos C. Cancer patients' experiences on self-management of chemotherapy treatment-related symptoms: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;49:101837-101920. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu H, Chen X, Yang J, et al. Mobile breast cancer e-support program for Chinese women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy (Part 3): Secondary data analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(9):e18896. doi: 10.2196/18896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The individual and family self-management theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57(4):217-225. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ungar N, Sieverding M, Weidner G, Ulrich CM, Wiskemann J. A self-regulation-based intervention to increase physical activity in cancer patients. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21(2):163-175. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1081255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baydoun M, Barton DL, Arslanian-Engoren C. A cancer specific middle-range theory of symptom self-care management: A theory synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(12):2935-2946. doi: 10.1111/jan.13829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang SY, Chao TC, Tseng LM, et al. Symptom-management self-efficacy mediates the effects of symptom distress on the quality of life among taiwanese oncology outpatients with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(1):67-73. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: Defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200-207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y. Construction and Research of Cloud Platform of Targeted Drug Therapy Based on Self-Management Model for Breast Cancer Patients. Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2019. [Online]. Available: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201902&filename=1019063941.nh [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitehead AL, Julious SA, Cooper CL, Campbell MJ. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(3):1057-1073. doi: 10.1177/0962280215588241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kearney N, McCann L, Norrie J, et al. Evaluation of a mobile phone-based, advanced symptom management system (ASyMS) in the management of chemotherapy-related toxicity. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(4):437-444. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egbring M, Far E, Roos M, et al. A mobile app to stabilize daily functional activity of breast cancer patients in collaboration with the physician: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(9):e238. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zraik IM, Heß-Busch Y. Management of chemotherapy side effects and their long-term sequelae. Urologe. 2021;60(7):862-871. doi: 10.1007/s00120-021-01569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwak A, Jacobs J, Haggett D, Jimenez R, Peppercorn J. Evaluation and management of insomnia in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181(2):269-277. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adjogatse D, Thanopoulou E, Okines A, et al. Febrile neutropaenia and chemotherapy discontinuation in women aged 70 years or older receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Clin Oncol. 2014;26(11):692-696. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klastersky J, de Naurois J, Rolston K, et al. Management of febrile neutropaenia: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v111-v118. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brooke J. SUS: a “quick and dirty” usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland AL, eds. Usability Evaluation in Industry. London, UK: Taylor and Francis; 1996:189-194. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lev EL, Owen SV. A measure of self-care self-efficacy. Res Nurs Health. 1996;19(5):421-429. doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian HJ, Yuan CR. The validation of the Chinese version of strategies used by people to promote health. Chin J Nurs. 2011;46(1):87-89. doi: CNKI:SUN:ZHHL.0.2011-01-040. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveira IS, da Cunha Menezes Costa L, Fagundes FR, Cabral CM. Evaluation of cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaires: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1179-1195. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0840-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974-986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan C, Zhang D, Yang Z, et al. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the FACT-B for measuring quality of life for patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(3):413-418. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M, Kasimis BS, Thaler HT. The memorial symptom assessment scale short form (MSAS-SF). Cancer. 2000;89(5):1162-1171. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu L, Hu Y, Lu Z, et al. Validation of the simplified chinese version of the memorial symptom assessment scale-short form among cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(1):113-121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zapata BC, Fernández-Alemán JL, Idri A, Toval A. Empirical studies on usability of mHealth apps: a systematic literature review. J Med Syst. 2015;39(2):1. doi: 10.1007/s10916-014-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10156):1403-1412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crafoord MT, Fjell M, Sundberg K, Nilsson M, Langius-Eklöf A. Engagement in an interactive app for symptom self-management during treatment in patients with breast or prostate cancer: Mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e17058. doi: 10.2196/17058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Min YH, Lee JW, Shin YW, et al. Daily collection of self-reporting sleep disturbance data via a smartphone app in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e135. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]