Abstract

Background

A previous study reported the effectiveness and patient satisfaction in the dental emergency unit (DEU) of the Pitie Salpetrière Hospital in Paris before coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The same methodology was used during the COVID-19 pandemic to compare pain, anxiety, and patient satisfaction during the two periods.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted in 2020 (NCT04354272) on adult patients. Data were collected on day zero (D0) on site and then by phone during the daytime on day one (D1), day three (D3), and day seven (D7). The primary objective was to assess the pain intensity at D1. Secondary objectives were to assess pain intensity at D3 and D7, anxiety intensity at D1, D3, and D7, and patient satisfaction. Patients were evaluated on a 0-10 numeric scale on D1, D3, and D7; mean scores were compared with non-parametric statistics (ANOVA, Dunn’s).

Results

A total of 445 patients were given the opportunity to participate in the study, and 370 patients consented. Seventy-one were lost during follow-up. Ultimately, 299 patients completed all the questionnaires and were included in the analysis. In the final sample (60% men, 40% women, aged 39 ± 14 years), 94% had health insurance. The mean pain scores were: D0, 6.1 ± 0.14; D1, 3.29 ± 0.16; D3, 2.08 ± 0.16; and D7, 1.07 ± 0.35. This indicates a significant decrease of 46%, 67%, and 82% at D1, D3, and D7, respectively, when compared to D0 (P < 0.0001). The mean anxiety scores were D0, 4.7 ± 0.19; D1, 2.6 ± 0.16; D3, 1.9 ± 0.61; and D7, 1.4 ± 0.15. This decrease was significant between D0 and D7 (ANOVA, P < 0.001). Perception of general health improved between D1 and D7. The overall satisfaction was 9.3 ± 0.06.

Conclusion

DEU enabled a significant reduction in pain and anxiety with high overall satisfaction during COVID-19, which was very similar to levels observed pre-COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Anxiety, COVID-19, Dental, Emergencies, Oral Health

INTRODUCTION

Patients visit dental emergency units (DEU) primarily because of pain resulting from dental and periodontal infections. These are among the most prevalent conditions globally, and associated anxiety often delays the visit and complicates pain management [1,2]. Therefore, reducing pain and anxiety is a key factor in improving patients’ individual quality of life and reducing the socioeconomic cost of adverse oral conditions [3]. A previous study (URGDENT) from our group in 2019 analyzed the effectiveness of DEU and demonstrated a significant reduction in pain and anxiety associated with high satisfaction [4].

A few months after after the completion of the URGDENT study, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic impacted healthcare systems, including dental emergency services [5,6,7,8,9]. Lockdowns and calls for community discipline were enforced worldwide to prevent the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for the disease. In France, all dental offices were closed on March 18th [10] due to the lack of protective equipment, except dental offices in hospitals such as the Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital. Soon after the closure, permanent emergency care was set up due to private and public stock of filtering facepiece level 2 (FFP2) masks. This allowed dental offices to participate in emergency care in rotation according to national sanitary instructions. In Paris, the introduction of the phone call platform Covident [11], advertised on hospital websites and by the National Council of Dental Surgeons, allowed an upstream sorting of patients wishing to consult. The complete reopening of private dental practices occurred on May 11th 2020.

Several studies have reported on the impact of COVID-19 on the organization of services [5,7,12], as well as on the consequences in terms of oral health, including pain [6,12,13,14]. However, few data are available related to dental emergencies.

Therefore, we wanted to collect the same data as in the URGDENT study—that is, pain, anxiety, and patient satisfaction—but in the context of the pandemic to assess its impact on the DEU and the oral health of patients.

METHODS

1. Study design

The main objective of this study was to assess the reduction in pain 24 h after the emergency visit on day zero (D0). The secondary objectives were to 1) assess the evolution of pain on day three (D3) and day seven (D7) after the emergency visit; 2) assess the evolution of anxiety on day one (D1), D3, and D7 after the emergency visit; and 3) assess the perception of nursing and non-nursing staff quality; and 4) the perception of the quality of care.

A prospective monocentric observational cohort study was carried out over nine weeks, from April 21st to June 29th, 2021, at the Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital DEU in Paris. The present study followed the URGDENT study methodology (NCT03819036) [4], with a few differences regarding care organization during the pandemic. This study was approved by the IRB (AP-HP: 2020-00990-39) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04354272). STROBE recommendations were followed for the study design and report writing. Good clinical trial practices were supervised by the Clinical Research Unit of Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital.

2. Setting

The sample consisted of adult patients (> 18 years old) who presented to the Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital DEU for emergency care. The DEU is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The patient either presented themselves directly to the hospital or came after calling the telephone platform, Covident [11], which sorted patients according to the assessed severity of the emergency. Care was provided by residents (postgraduate students), under the supervision of a senior, or by the seniors themselves (university hospital, hospital practitioner, or consultant). Upon arrival, patients took a ticket with their number and time of arrival. They were called for care according to the order of their arrival, except for priorities (trauma, cellulitis, hemorrhage, pregnant women, prisoners, or hospitalized or invalid patients). A clinical examination and diagnosis were performed, and therapeutic decisions were made, such as immediate care and/or prescription. The treatment provided was appropriate to the patient’s situation and the extent of the service provided, as judged by the seniors. For example, in the case of an acute apical abscess, the practitioner can either perform endodontic treatment or drainage per standard procedure or prescribe antibiotic and analgesic treatment with a timeous general practitioner referral. The Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital is an adult hospital where children are only occasionally admitted depending on the emergency. Hence, the study was conducted on adult patients.

3. Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis was defined according to international recommendations [15,16,17,18,19]: pulpal emergencies, including reversible pulpitis, irreversible pulpitis, acute apical periodontitis, acute apical abscess, periodontal abscess, pericoronitis, septum syndrome, ulcerative necrotic disease, alveolitis, cellulitis, temporomandibular disorder, oral mucosal pathology, and prosthodontics.

4. Participants

Participation in this study was proposed for consecutive patients presenting to the DEU. Those satisfying the eligibility criteria and willing to participate after receiving information were included after obtaining written consent. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 18 years, telephonic availability of patients during the week following the visit, and a good understanding of French. Participants with impaired communication were excluded from the study.

5. Time period of the study

Clinical data were collected by two investigators (DZ and P-A–J). After patients’ consent to participate and recording of their medical history at D0 in the DEU, patients completed the sociodemographic and medical questionnaire. They were clinically evaluated, diagnosed, and received relevant emergency care, prescriptions, or advice according to their medical condition. Before leaving, they completed the satisfaction questionnaire. At D1, D3, and D7, evaluation questionnaires were completed by an investigator via telephone interviews.

6. Data collection

Data were collected through questionnaires during emergency visits and telephone calls. Sociodemographic data included social insurance status, dental consultation habits, the reason for DEU consultation, and how the patient got to the DEU. Medical data included medical history and actual treatment, DEU diagnosis, prescribed therapeutics, and further treatment. Efficacy measures included self-assessed pain and anxiety at different time points. Satisfaction measures included perception of politeness of both medical and non-medical staff, availability of non-medical staff, quality of care setting, cleanliness, wait time, quality of medical information, and willingness to recommend the DEU to family or friends.

7. Evaluation criteria

The main evaluation criteria were the self-evaluated pain score assessed on a 0-10 (0 = absence of pain; 10 = maximum pain imaginable) numerical scale [20], collected at baseline (D0) and D1. The secondary evaluation criteria were: 1) self-assessed pain at D-1 (24h before D0), D3 and D7, measured with the numerical scale; 2) anxiety score on D0, D1, D3, and D7, measured on a 0-10 numerical scale [21]; 3) patient perception of reception quality on D0 (politeness, availability of non-medical staff, care setting, quality of premises, cleanliness, wait time), measured using a 0-10 numerical scale; and 4) the patient-assessed quality of care evaluation immediately after treatment (D0), on a 0-10 numerical scale.

8. Sample size

We aimed to assess the DEU activity twice a week over four weeks. An analysis of the number of patients attending the DEU at the beginning of the pandemic (March 16th-22nd) indicated 80 patients on average per day. The number of possible inclusions was fixed at 640.

9. Data analysis

The investigators were trained for telephonic interviews. Patients who did not answer the phone during the follow-up period were contacted the next day. The pain and anxiety scores were extrapolated by calculating the nearest point on the curve connecting the previous data and the newly collected data. If the patients did not answer again the following day, the data were considered missing. Data were anonymized throughout the study.

10. Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the sample was performed. Pain and anxiety scores were grouped into three classes: absent or mild from 0 to 4, moderate from 5 to 7, and severe from 8 to 10. Statistical analysis of the evolution of pain and anxiety scores between D0, D1, D3, and D7 was performed using GraphPad Prism Software 5 with ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post-test. Correlations between the treatment type and perceived pain, as well as between the treatment type and perceived anxiety, were determined using Pearson correlations (r). Contingency analyses were performed using the chi-squared test. The level of significance was set at 95%.

RESULTS

1. Flow chart

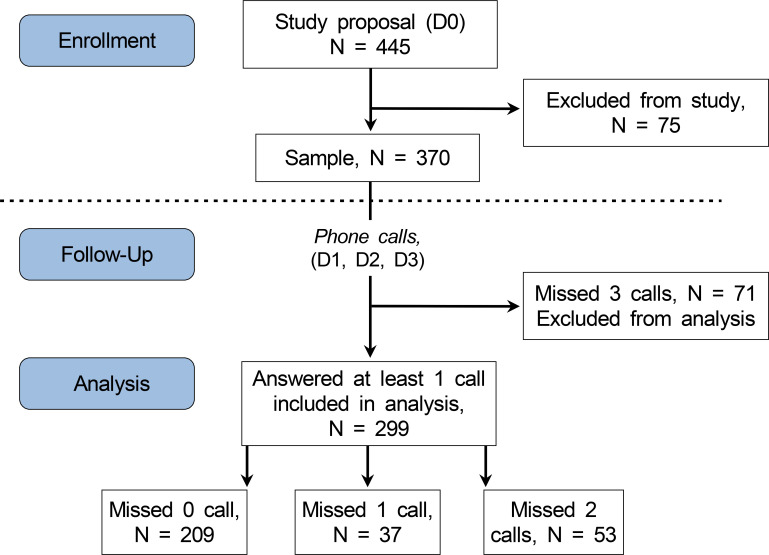

A total of 445 patients were contacted, of whom 75 were removed according to the exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The final sample included 370 patients. Of these, 209 patients answered all calls, 37 missed one call, 53 missed two calls, and 71 missed three calls. These 71 patients were considered lost during follow-up and were excluded from the analysis.

Fig. 1. Study flowchart.

2. Characteristics of the sample

1) Socio-demographics

The sample included 222 (60%) men and 148 (40%) women, with an average age of 39 ± 14 years. The patient distribution by age group was as follows: < 30, 30%; 30-39, 29%; 40-49, 18%; 50-59, 11%; 60-69, 8%; 70-79, 3%; and ≥ 80, 0%. Twenty-one patients (6%) had no health insurance, 94% had health insurance, including 77% social security (classic health insurance), 13% universal health coverage (minimum coverage), and 4% state medical aid. Overall, the number of medical conditions increased with age: patients with no medical conditions represented 73% of the sample (N = 270, mean age 36.76 ± 0.74); patients with one medical condition represented 13% (N = 48, mean age 40.15 ± 1.99) and patients with two medical conditions or more represented 14.05% (N = 52, mean age 51.75 ± 2.307). A total of 252 patients (69%) reported visiting a dentist less than one year ago. However, 31% had not visited the dentist for more than two years: 12%, 1 to 2 years; 11%, 2 to 5 years; and 8%, more than five years. Overall, dental check-up visits increased with the quality of health insurance. 48% of patients who had a dental check-up less than one year prior were without health insurance, 60% had state medical aid, 70% had social security, and 73% had universal health coverage. On the contrary, patients who only had their last dental check-up more over five years ago were 14% without social security, 7% with state medical aid, 6% with universal health coverage, and 8% with social security.

There was a statistically significant difference in pain scores between subjects with regular social security and patients with no or minimal health insurance (universal health coverage and state medical aid) for both pain < 24h (8.9 ± 0.17 vs. 7.9 ± 0.14; P < 0.001) and pain at D0 (6.7 ± 0.27 vs. 5.9 ± 0.16; P < 0.001).

A total of 131 patients (35%) came directly to the DEU, while 239 (65%) made an appointment with a dentist before visitation. The majority (N = 181, 76%) came to the DEU because their regular dental office was closed due to the pandemic. Forty (17%) were referred by their general practitioner, eight (3%) came because of persistent pain despite a visit to their general practitioner, and three (1%) visited the DEU because the appointment was too far.

2) Sample clinical characteristics

The primary reason for consultation was pain (N = 350, 91%), of which, 8% was associated with swelling. Other reasons were seeking advice (3%), trauma (2%), bleeding (1%), and swelling only (1%). The medical diagnoses sorted by frequency were acute alveolar abscess (N = 88, 23.7%), acute apical periodontitis (N = 73, 19.6%), and irreversible pulpitis (N = 50, 13.4%). Cellulitis (N = 34, 9.1%), trauma (N = 17, 4.6%), reversible pulpitis (N = 16, 4.3%), pericoronitis (N = 16, 4.3%), and periodontal abscess (N = 14, 4.6%). The remaining (14.5%) included pathologies of the oral mucosa, sinusitis, muscle pain, salivary pathologies, loss of crown, and patient orientation errors.

3. Efficacy

1) Pain

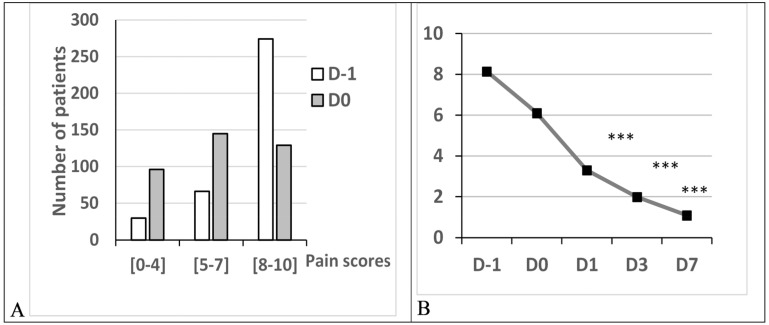

The distribution of pain scores on day minus one (D-1) and D0, and their evolution from D-1 to D7, are illustrated in Figure 2. Mild and moderate pain were more frequent on D0, whereas the opposite trend was observed for severe pain. Mean pain scores at D-1, D0, D1, D3, and D7 were 8.13 ± 0.11, 6.10 ± 0.14, 3.29 ± 0.16, 2.08 ± 0.16, 1.07 ± 0.35, respectively. This indicates 46%, 67%, and 82% suppression at D1, D3, and D7, respectively. This decrease was statistically significant at all endpoints (ANOVA, Dunn’s test; P < 0.001). A significant decrease was observed between D-1 and D0.

Fig. 2. Distribution and evolution of pain scores. (A) Distribution of pain scores of pain scores at D-1 and D0 according to the severity of pain. (B) Evolution of pain scores (Mean ± SEM) from D-1 to D7, indicating a significant decrease between baseline at D0 and endpoints at D1, D3, and D7 (ANOVA, Dunn’s P < 0.001). Pain scores were self-evaluated on a [0-10] numeric rating scale.

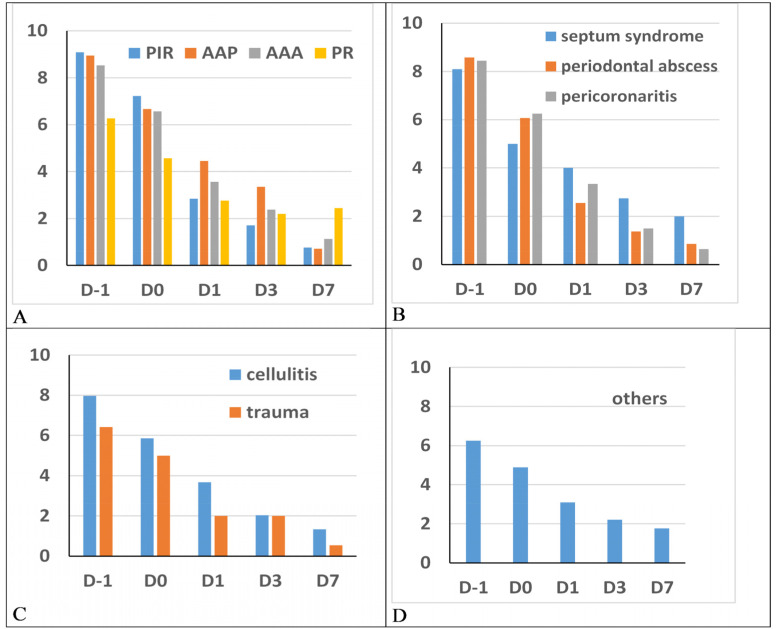

The pain scores and distribution according to the diagnoses are illustrated in Figure 3. Pain motivating the visit was mainly of pulpal origin (61%) and distributed as follows: acute apical abscess (N = 88, 23.7%), acute apical peridontitis (N = 73, 19.6%), irreversible pulpitis (N = 50, 13.4%), and reversible pulpitis (N = 16, 4.3%) vs. 49% for other diagnoses. Other dignoses included cellulitis (N = 34, 9.1%), periodontal abscess (N = 14, 3.8%), pericoronitis (N = 16, 4.3%), traumas (N = 17, 4.6%), and septum syndrome (N = 10, 2.7%). The scores for all categories decreased significantly between D0 and D1 (ANOVA, P < 0.001).

Fig. 3. Distribution of self-evaluated 0-10 pain scores (ordinates) from D-1 to D7 (abscissae) according to diagnosis. (A) Pulpal pain (AAA, AAP, PIR, PR). (B) Periodontal pain (septum syndrome, periodontal abscess, pericoronitis). (C) Cellulitis and traumas. (D) Other diagnoses including temporomandibular disorders, oral mucosal pathologies, prosthodontics, etc. AAA, acute apical abscess; AAP, acute apical periodontitis; PIR, irreversible pulpitis; PR, reversible pulpitis.

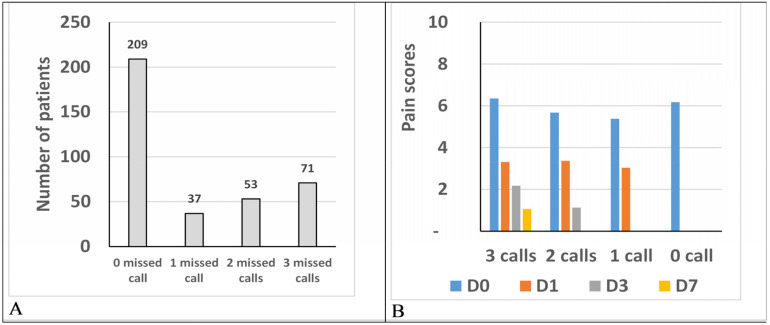

2) Patients not answering phone calls

Of the sample, 19.2% (N = 71) did not answer any calls and were considered non-responders. They were excluded from further analysis. The mean pain score at D0 was not significantly different between the non-responders (6.2 ± 0.28) and responders (6.08 ± 0.16) (M&W, P = 0.98). In the responding patients subgroup, 209 (56%) responded to the three phone calls, 37 (10%) to two, and 53 (14%) to one. These patients in the responded subgroup had D0 pain scores of 6.3 ± 0.18, 5.6 ± 0.53, and 5.4 ± 0.41, respectively. There was no significant difference in pain scores on D1 for patients responding to one, two, or three calls (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Pain status of phone call responders and non-responders. (A) Number of patients responding to phone calls. (B) Pain score according to the number of responded calls.

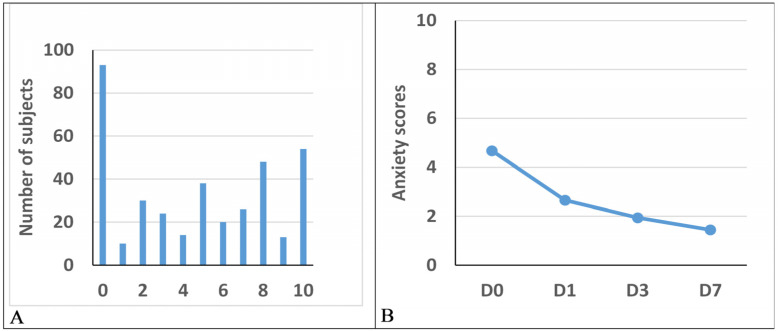

3) Anxiety

The overall anxiety level on D0 was low, with 73% of the scores in the 0 to 4 range, including 39% with no anxiety, or 19% of moderate scores in the 5 to 7 range Fig. 5). Severe anxiety—scores of 8 to 10—represented 8% of the participants. The mean anxiety scores decreased by 44.7%, 59.6%, and 70.2% between D0, D1, and D7, respectively (D0, 4.7 ± 0.19; D1, 2.6 ± 0.16; D3, 1.9 ± 0.61; D7, 1.4 ± 0.15). This decrease was significant between D0, D1, D3, and D7 (ANOVA, Dunn’s P < 0.001).

Fig. 5. Anxiety. (A) Distribution of anxiety scores at D0, self-evaluated on a 0-10 numeric rating scale. (B) volution of anxiety scores from D0 to D7. A significant decrease is observed between baseline at D3 and D7 (ANOVA, Dunn’s P < 0.001).

4) General Health

Overall, the perception of the patient’s general health improved with time. The average general health scores increased from 7.62 ± 0.11 at D0 to 7.93 ± 0.12 at D1 (P < 0.05) and from 8.36 ± 1.96 at D3 to 8.86 ± 0.11 at D7, which was significant for D3 (ANOVA, Dunns P < 0.001).

4. Treatments and further attention

A total of 205 patients (52%) received only a medical prescription, 131 (35%) received surgical treatment, 34 (9%) received endodontic treatment, and 31 (8%) received advice without treatment or prescription. In the sample, 8% of the patients (N = 70) consulted the DEU again on D3 or D7. The primary reasons for follow-up consultations were persistent pain (81%) or worsening of swelling (8%), while the remaining 11% came for extraction or control. Adherence to instructions given on D0 was reported by 97% of the patients on D1 and 96% on D7. Only 20% had made an appointment with a dentist for further care at D1, 32 at D3, and 46% at D7, either in private practice or at the Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital.

5. Sex, socioeconomic status, pain, and anxiety at D0

No correlation was found between pain and anxiety scores (r = -0.02; P = 0.54). Pain scores were not significantly different between men and women: 5.69 ± 0.28 vs. 6.03 ± 0.25. There was a statistically significant difference between pain scores according to health insurance status. Mean scores of 5.9 ± 0.16 vs. 6.76 ± 0.0.27 (P = 0.014, M&W test) were obtained for patients with social security and minimum health coverage (state medical aid, universal health coverage, no insurance), respectively. No evidence for differences between subcategories (state medical aid, universal health coverage, and no insurance) could be found. The mean pain scores for patients having consulted a dentist during the past year (6.0 ± 0.17) and patients having consulted a dentist 1-2, 2-5, and > 5 years prior (6.1 ± 0.4, 6.0 ± 0.51, and 6.6 ± 0.39, respectively) were not significantly different.

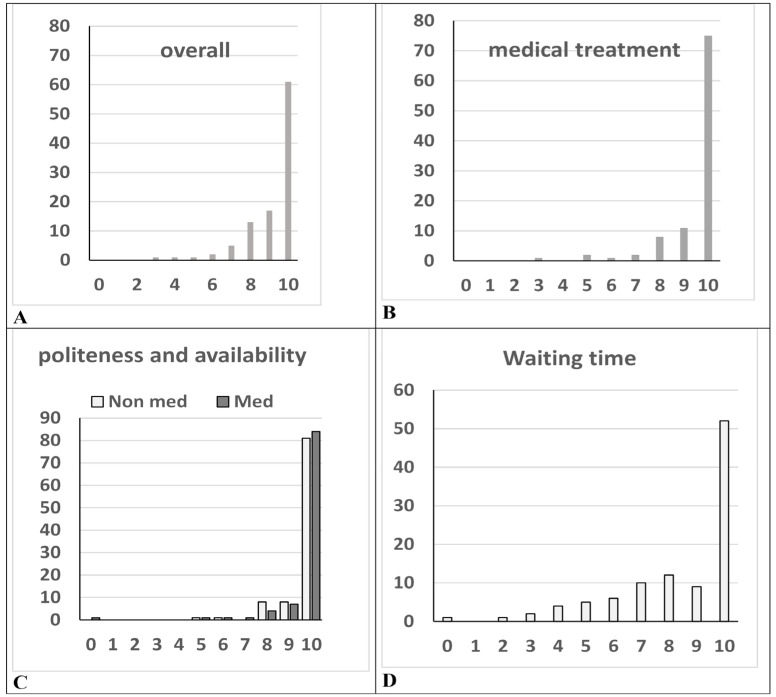

6. Satisfaction

The average overall satisfaction score after a visit to the DEU was 9.3 ± 0.06 (Fig. 6A). The perception of the quality of medical care was high (mean score 9.5 ± 0.06) (Fig. 6B). The mean score for politeness and availability of non-medical staff and medical staff was identical at 9.6 ± 0.05 with a slightly different distribution of scores (Fig. 6C). Almost all patients (96%) were satisfied with the provided treatment, and 95% were satisfied with the information received in the DEU, including postoperative instructions. The average time spent in the DEU, including time spent in the waiting room, consultation, and treatment, was 127 min ± 3.55, ranging from 10 to 430 min. The mean satisfaction score for wait time was 8.4 ± 0.11 (Fig. 6D). Wait time was the primary source of dissatisfaction for 12% of the patients of the sample who rated their satisfaction as inferior to 5. Overall satisfaction was confirmed by a high percentage of patients who would recommend the DEU to a friend/family member (95%) or would consult again (97%).

Fig. 6. Satisfaction evaluation (abscisses were self-evaluated at the end of the visit on a 0-10 numerical scale: ordinates are a % of the sample). (A) Distribution of overall satisfaction scores at D0. (B) Distribution of perception of medical treatment and information quality scores. (C) Distribution of politeness and availability of medical and non-medical staff scores. (D) Distribution of perception of wait time scores.

Non med, Non-medical; Med, Medical.

DISCUSSION

This study indicated a high prevalence of pain and anxiety in patients consulting in the DEU during the COVID-19 pandemic and a high DEU efficiency at reducing both indicators measured at three time points. Pain and anxiety decreased by an average of 82% and 70%, respectively, between D0 and D7. Furthermore, perceived satisfaction was excellent—99% of the sample scored their overall satisfaction above 5/10 with a mean score of 9.3/10.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample were very similar to those in the URGDENT study [4], which confirms that attending the DEU is not limited to populations with low socioeconomic status. In the present study, 33% of the patients had no or minimal health coverage compared with 31% in the URGDENT study. An increase in the attendance of insured patients could be expected due to limited access to dental offices, which was not necessarily the case. This further supports the idea that reasons for consulting at the hospital are not limited to insurance coverage.

Mean pain scores at consultation were not significantly different at D-1 and D0 between the COVID-19 pandemic (8.13 ± 0.11 and 6.10 ± 0.14, respectively) and pre-COVID-19 (7.68 ± 0.12 and 6.36 ± 0.12, respectively). An increase in pain scores during the COVID-19 pandemic could be expected due to difficulties finding a dentist or the financial burden of the pandemic [13], but this was not the case. It must be noted that pain scores were already high pre-COVID-19. The change in the organization (triage) of some patients before admission contributed to the selection of only patients with high pain levels. However, calling the hospital before arrival was not mandatory to access the DEU.

Pain decrease was also very similar to that observed pre-COVID-19: 3.29 ± 0.16, 2.08 ± 0.16, 1.07 ± 0.35 for during the pandemic at, D1 D3, D7 respectively; and 3.49 ± 0.13, 2.24 ± 0.13, 1.07 ± 0.13 for pre-COVID-19 at, D1 D3, D7 respectively. Despite the altered flow of patients and non-standard DEU organization, as reported in other studies [7], the ability to respond to dental emergencies was maintained at the same efficacy.

An unexpected result was the relatively low levels of anxiety. Anxiety levels were higher during pre-COVID-19 than during the pandemic (mean score at D0 = 4.7 ± 0.19, vs. 3.32 ± 0.15). Severe anxiety scores (scores of 8 to 10) were lower (8% of the sample) during COVID-19 than pre-COVID-19 (23%). This seems counterintuitive but could be related to changes in perception of the situation elicited by the COVID-19 pandemic. Dental emergencies may have been seen as less critical than a COVID-19 infection or other changes elicited by the pandemic, such as lockdown. Surprisingly, there was no difference between the COVID-19 and pre-COVID-19 general health perception (7.62 ± 0.11 vs. 7.56 ± 0.09). The occurrence of advanced vital emergencies (cellulitis) was 9.1% vs. 9.2%, suggesting that measures taken by health authorities and hospitals were effective in identifying vital emergencies.

Pain was the primary reason for consultation in 91% of the sample (associated with swelling in 8% or trauma in 2%). This was similar to the URGDENT study (except for swelling in 16%) and is in the higher percentile of emergency studies at 39%-88% [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The main differences with the URGDENT study were the other diagnostic categories—14% in pre-COVID-19 vs. 2% during COVID-19. This suggests that Covident was able to sort patients with real emergencies. Regardless, the DEU benefited these patients as pain and anxiety levels dropped to minimal levels at the same rates as pre-COVID-19, an important achievement for both oral and general health.

The average overall satisfaction score after visiting the DEU during COVID-19 was 9.3 ± 0.06 vs. 8.6 ± 0.06 pre-COVID-19, suggesting that people were more grateful to the hospital for providing care during the pandemic. Satisfaction rates assessed both medical and non-medical staff. Almost all patients (96%) were satisfied with the provided treatment, and 95% were satisfied with the information received, including postoperative instructions, in the DEU.

Limitations

Language may have been a potential source of selection bias. Patients who did not have a sufficient grasp of the French language to understand the protocol and questionnaires were excluded. These patients may have a lower socioeconomic status and health coverage than those included in the study. This study evaluated the DEU only during standard work and daytime hours. After-hours consultations were evaluated in an ancillary study (NCT04354272) [30].

Conclusion

The results of the present study are very similar to those obtained during the pre-COVID-19 period suggesting a good adaptation of the DEU, preserving the efficacy of oral health care during the pandemic. Provision of adequate responses to dental pain and anxiety is critical to general health and population satisfaction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank the URC of Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital for their invaluable help with the administrative aspects of the study, particularly Laura Wakselman. We also give a very warm thanks to all colleagues in the dental services department of the Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital who contributed to maintaining the continuity of care during the difficult period of COVID-19.

Footnotes

- Isabelle Rodriguez: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft.

- Daniel Zaluski: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration.

- Pierre Alain Jodelet: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

- Geraldine Lescaille: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

- Rafael Toledo: Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

- Yves Boucher: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING: This research was performed with recurrent funding allocated to LabNOF.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data are available on demand from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Carlsson SG. Prevalence of dental anxiety in an adult population in a major urban area in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nazir M, Almulhim KS, AlDaamah Z, Bubshait S, Sallout M, AlGhamdi S, et al. Dental fear and patient preference for emergency dental treatment among adults in COVID-19 quarantine centers in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:1707–1715. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S319193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oghli I, List T, Su N, Häggman-Henrikson B. The impact of oro-facial pain conditions on oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47:1052–1064. doi: 10.1111/joor.12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demeestere G, Alcabes M, Toledo R, Rodriguez I, Boucher Y. Effectiveness of and patient’s satisfaction of dental emergencies in Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital (Paris), focusing on pain and anxiety. Int J Dent. 2022;21:8457608. doi: 10.1155/2022/8457608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulthard P, Thomson P, Dave M, Coulthard FP, Seoudi N, Hill M. The COVID-19 pandemic and dentistry: the clinical, legal and economic consequences - part 2: consequences of withholding dental care. Br Dent J. 2020;229:801–805. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauquis J, Petit AE, Michaux V, Sagué V, Henrard S, Leprince JG. Dental emergencies management in covid-19 pandemic peak: a cohort study. J Dent Res. 2021;100:352–360. doi: 10.1177/0022034521990314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99:481–487. doi: 10.1177/0022034520914246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzato VL, Lotto M, Lourenço Neto N, Oliveira TM, Cruvinel T. Digital surveillance: the interests in toothache-related information after the outbreak of COVID-19. Oral Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1111/odi.14012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier S. The Big Interview (le grand entretien) ONCD La lettre. 2020:3–8. Available from https://www.ordre-chirurgiens-dentistes.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/LA_LETTRE_184_2020.pdfRE_184_2020.pdf (ordre-chirurgiens-dentistes.fr) [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Zein A. Management of oral emergencies in Ile de France during the COVID-19 health crisis: analysis of data from the APHP’s COVIDENT system (gestion des urgences bucco-dentaires en Ile de France pendant la crise sanitaire du COVID-19 : analyse des données du dispositif COVIDENT de l’APHP) Université de Paris; 2021. Thesis, Available from https://www.sudoc.fr/259862207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter E, von Bronk L, Hickel R, Huth KC. Impact of COVID-19 on dental care during a national lockdown: a retrospective observational study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7963. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuyama Y, Aida J, Takeuchi K, Koyama S, Tabuchi T. Dental pain and worsened socioeconomic conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Res. 2021;100:591–598. doi: 10.1177/00220345211005782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamsoddin E, DeTora LM, Tovani-Palone MR, Bierer BE. Dental care in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Med Sci (Basel) 2021;9:13. doi: 10.3390/medsci9010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dummer PM, Hicks R, Huws D. Clinical signs and symptoms in pulp disease. Int Endod J. 1980;13:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1980.tb00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glickman GN. AAE Consensus conference on diagnostic terminology: background and perspectives. J Endod. 2009;35:1619–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin LG, Law AS, Holland GR, Abbott PV, Roda RS. Identify and define all diagnostic terms for pulpal health and disease states. J Endod. 2009;35:1645–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mejàre IA, Axelsson S, Davidson T, Frisk F, Hakeberg M, Kvist T, et al. Diagnosis of the condition of the dental pulp: a systematic review. Int Endod J. 2012;45:597–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miranda-Rius J, Brunet-Llobet L, Lahor-Soler E. The periodontium as a potential cause of orofacial pain: a comprehensive review. Open Dent J. 2018;12:520–528. doi: 10.2174/1874210601812010520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flaherty SA. Pain measurement tools for clinical practice and research. AANA J. 1996;64:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Facco E, Stellini E, Bacci C, Manani G, Pavan C, Cavallin F, et al. Validation of visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A) in preanesthesia evaluation. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79:1389–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson GB, Blasberg B, Hill SJ. A prospective survey of hospital ambulatory dental emergencies. Part 1: Patient and emergency characteristics. Spec Care Dentist. 1993;13:61–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1993.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson R, Thomas DW, Phillips CJ. The effectiveness of out-of-hours dental services: I. Pain relief and oral health outcome. Br Dent J. 2005;198:91–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley JL, 3rd, Gilbert GH, Heft MW. Orofacial pain: patient satisfaction and delay of urgent care. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:140–149. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estrela C, Guedes OA, Silva JA, Leles CR, Estrela CR, Pécora JD. Diagnostic and clinical factors associated with pulpal and periapical pain. Braz Dent J. 2011;22:306–311. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402011000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stolbizer F, Roscher DF, Andrada MM, Faes L, Arias C, Siragusa C, et al. Self-medication in patients seeking care in a dental emergency service. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2018;31:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, Choi E, Park KM, Kwak EJ, Huh J, Park W. Characteristics of patients who visit the dental emergency room in a dental college hospital. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2019;19:21–27. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2019.19.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rauch A, Hahnel S, Schierz O. Pain, dental fear, and oral health-related quality of life-patients seeking care in an emergency dental service in Germany. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2019;20:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frichembruder K, Mello Dos Santos C, Neves Hugo F. Dental emergency: scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0222248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sitbon E, Amsallem E. Qualitative assessment of emergency care of the department of dentistry of the GHPS by patients during night and week-end shifts, outside the COVID period (Urgences odontologiques au GHPS : étude observationnelle sur le réssenti des patients nuit et week-ends en période COVID et non COVID) Université de Paris; 2021. Thesis, Available from https://www.sudoc.fr/259143804. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on demand from the corresponding author.